Abstract

Many therapeutically important enzymes are present in multiple cellular compartments, where they can carry out markedly different functions, thus there is a need for pharmacological strategies to selectively manipulate distinct pools of target enzymes. Insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) is a thiol-sensitive zinc-metallopeptidase that hydrolyzes diverse peptide substrates in both the cytosol and the extracellular space, but current genetic and pharmacological approaches are incapable of selectively inhibiting the protease in specific subcellular compartments. Here we describe the discovery, characterization and kinetics-based optimization of potent benzoisothiazolone-based inhibitors that, by virtue of a unique “quasi-irreversible” mode of inhibition, exclusively inhibit extracellular IDE. The mechanism of inhibition involves nucleophilic attack by a specific active-site thiol of the enzyme on the inhibitors, which bear an isothiazolone ring that undergoes irreversible ring opening with the formation of a disulfide bond. Notably, binding of the inhibitors is reversible under reducing conditions, thus restricting inhibition to IDE present in the extracellular space. The identified inhibitors are highly potent (IC50app = 63 nM), non-toxic at concentrations up to 100 μM and, were found to selectively target a specific cysteine residue within IDE. These novel inhibitors represent powerful new tools for clarifying the physiological and pathophysiological roles of this poorly understood protease, and their unusual mechanism of action should be applicable to other therapeutic targets.

Keywords: covalent inhibition, high-throughput screening, inhibitor design, irreversible inhibition, protease inhibition

INTRODUCTION

Insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) is an atypical zinc-metallopeptidase that hydrolyzes intermediate-sized peptide substrates in multiple subcellular compartments, including cytosol, mitochondria, and the extracellular space1. IDE is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis and potential treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease, by virtue of its well-established role in the degradation of two extracellular substrates: insulin and the amyloid ß-protein (Aß)2. However, IDE degrades many intracellular substrates, as well, which are implicated in diverse physiological processes3–5. Currently available genetic and pharmacological tools target all pools of IDE simultaneously, thus experimental probes that can selectively manipulate distinct pools of IDE will be required to disentangle the distinct roles of intracellular versus extracellular pools of IDE. Moreover, for therapeutic applications, such as inhibiting the breakdown of insulin for the treatment of diabetes6, strategies that avoid the inhibition of intracellular pools of IDE will help minimize undesirable side effects. There is, therefore, a need for experimental probes and pharmacophores that selectively target pools of IDE in different subcellular compartments, particularly the extracellular space.

IDE evolved independently from most conventional zinc-metalloproteinases7 and consequently possesses a number of distinguishing characteristics. For instance, IDE contains a zinc-binding motif (HxxEH) that is inverted with respect to the canonical zinc-metalloproteinase motif (HExxH)8. IDE can also be distinguished pharmacologically from most other zinc-metalloproteinases by its sensitivity to thiol-alkylating agents9–11, such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and iodoacetamide. The most common (non-mitochondrial) isoform of IDE contains 13 cysteine residues12, and inhibition by thiol-modifying agents such as NEM is known to occur principally via modification of two specific cysteines, C812 and C819, which reside within the C-terminal half of IDE’s unusual bipartite active site10, 11. However, NEM and other thiol-alkylating compounds are not suitable for inhibiting IDE in cell-based applications due to broad reactivity with biological nucleophiles, very low IDE potency (with apparent IC50 (IC50app) values >200 μM) and cellular toxicity at effective concentrations.

IDE’s unusual subcellular localization profile is a further distinguishing feature1. IDE is located principally in cytosol, and also has been described within various intracellular compartments, including endosomes, peroxisomes and mitochondria1. On the other hand, IDE is also secreted into the extracellular space via a non-conventional protein export mechanism13 reported to involve exosomes14. Membrane-associated forms of IDE present on the cell surface have also been described15. Because these separate pools of IDE degrade different sets of substrates implicated in divergent physiological processes, there is a great need for pharmacological tools that can selectively target intracellular versus extracellular pools of IDE.

Herein we describe the discovery, characterization and kinetics-based optimization of thiol-targeting IDE inhibitors in the benzoisothiazolone structural class. These compounds exhibit high potency (IC50app values as low as 63 nM), low cellular toxicity, IDE selectivity, and act by modifying only the C819 residue of IDE. Notably, by virtue of a unique “quasi-irreversible” mechanism of inhibition, which is operative only in the oxidizing environment of the extracellular space, these compounds exclusively target extracellular pools of IDE. These novel inhibitors—which are the first drug-like, non-peptidic IDE inhibitors yet described—represent powerful new tools for dissecting the divergent roles of distinct pools of this biomedically important protease.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

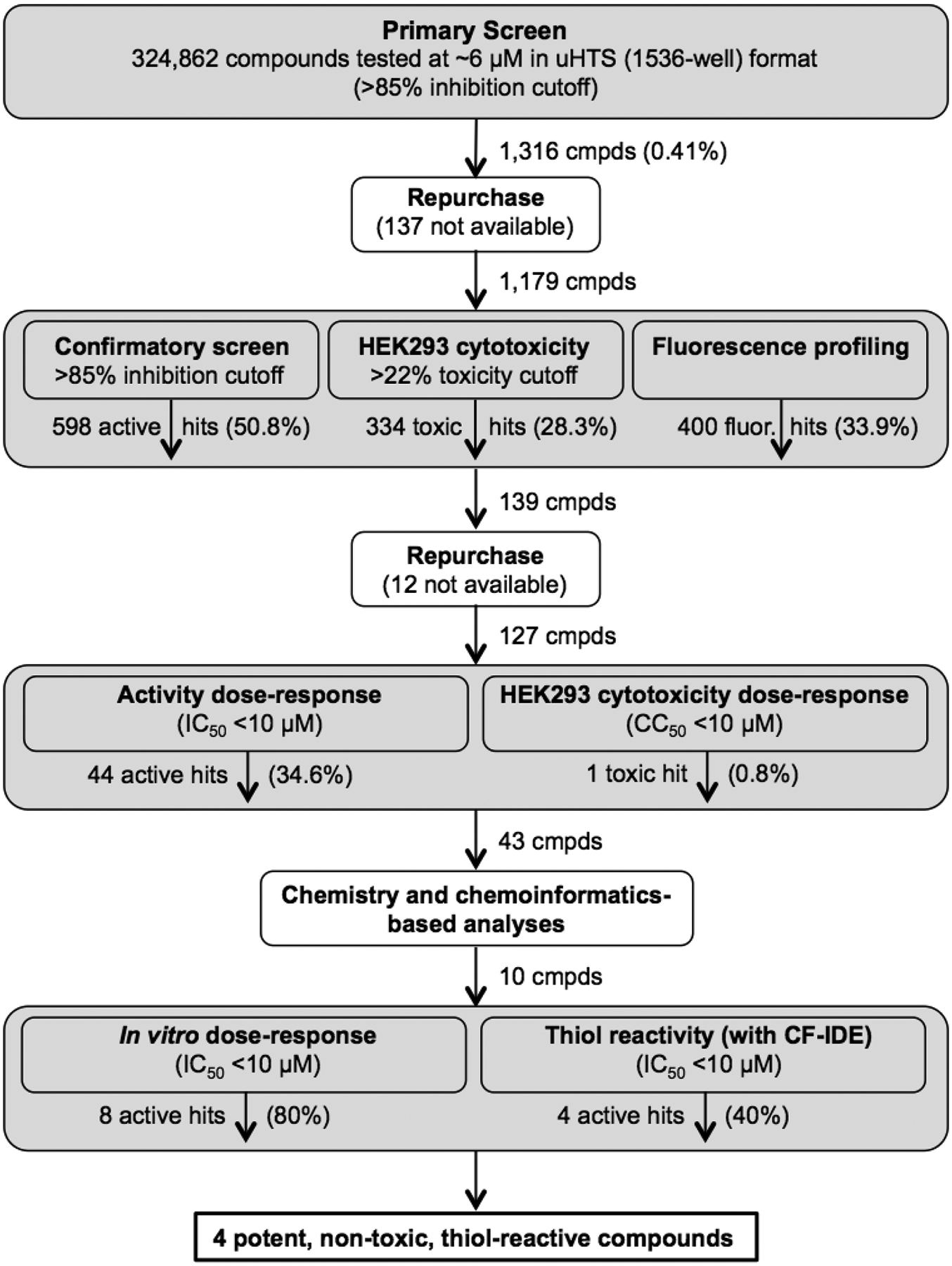

To identify novel IDE inhibitors, we conducted a large-scale, cell-based compound screening campaign (Figure 1; PubChem Assay Identifier (AID) 434984) on the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) library, at the time a collection of ~325,000 structurally diverse compounds, with most conforming to Lipinski’s Rule of Five (Ro5)16. The primary screen was conducted in 1536-well format using a well-established, fluorescence polarization-based assay that is a sensitive measure of extracellular IDE activity17, with nominal compound concentrations of 6 μM. HEK-293 cells, harvested mechanically rather than by trypsinization, were used as an endogenous source of IDE, which is secreted abundantly into the extracellular space1, 18. The performance of the assay in the primary screen was exceptionally good, with Z’ factor values19 routinely exceeding 0.8. Hit cytotoxicity was assessed separately using a luminescence-based HEK cell viability assay. From among the 324,862 compounds tested, 1,316 (0.41%) exhibited inhibition exceeding a predetermined cutoff of ~85% at 6 μM. Available actives were retested in the primary screen to confirm activity and in a number of secondary screens to identify fluorescence artifacts and toxic hits. Thus 127 hits were triaged in dose-response format for IDE activity in cells, for cytotoxicity, and for activity in a cell-based assay utilizing recombinant IDE. A total of 44 hits showed IC50app values <10 μM (Figure 1), which were subsequently tested using a well-established IDE activity assay20 based on a fluorogenic peptide substrate (FRET1) with recombinant wild-type IDE (WT-IDE) or a cysteine-free form of IDE (CF-IDE)11.

Figure 1.

Overview of compound screening campaign.

One family of compounds, the benzoisothiazolones, showed particular promise, with four compounds (compounds 1-4, Table 1) showing encouraging potency in the cell-based IDE assay (IC50app 1–4 μM) and also good potency in our cell-free IDE activity assay (IC50 200–1100 nM). A fifth compound in the class (compound 5) was inactive by hit cutoff criteria (Table 1). Two additional compounds, 6 and 7 were available by purchase, with compound 6 being inactive and compound 7 being active (Table 1).

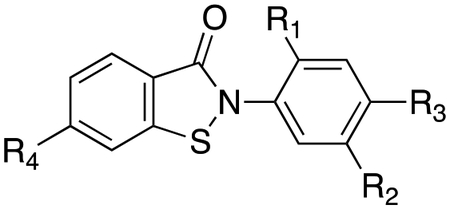

Table 1.

SAR of compounds identified by uHTS and purchased variants thereof.

| Cmpd | CID | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | IC50app (μM) cell-based | IC50app (μM) cell-free |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

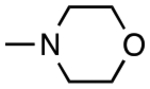

| 1 | 2325815 |

|

|

H | H | 1.4 | 0.23 |

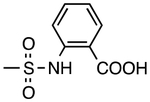

| 2 | 4089709 | H |

|

H | H | 2.1 | 0.54 |

| 3 | 2327953 | H |

|

CH3 | H | 4.0 | 1.03 |

| 4 | 2327938 |

|

|

H | H | 5.6 | 1.12 |

| 5 | 5040456 | H |

|

H | H | >10 | NTa |

| 6 | 2325816 | H | H | H | H | >10 | >10 |

| 7 | 22416235 | H | H | H | F | 3.9 | 1.8 |

NT=not tested

The wide range in potency of this series, apparent in both the cell-based assay (IC50app 1–10 μM) and the cell-free assay (IC50app 0.23–10 μM) (Table 1), indicated that their potency was not solely determined by the presence of the thiol-reactive isothiazolone moiety, but was instead dependent on making other productive contacts with IDE. For example, the most potent hit, PubChem CID 2325815 (compound 1 in Table 1) has a morpholine group present at the R1 position. Were the benzoisothiazolones merely acting as non-selective and chemically reactive cysteine traps, without significant cooperative binding to the enzyme, such an electron-donating and bulky ortho substituents would be expected to decrease, rather than increase, the ability of the ligand to interact with IDE. While some electronic effects are apparent (e.g., compare compounds 6 and 7), compound electrophilicity is not the sole factor driving their ability to inhibit IDE.

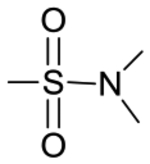

We next sought to elucidate the mechanism of action of compound 1 (CID 2325815), by testing it in a range of assays. To that end, compound 1 was synthesized de novo and purified to >99% purity by final preparative HPLC, to exclude the possible influence of trace impurities, which had given false-positive results in other compound series. Compound 1 exhibited good potency against WT-IDE (IC50app = 233 nM), while showing no activity against CF-IDE (Figure 2A), indicating that the inhibition indeed depended on the presence of thiols. Consistent with a covalent interaction, inhibition by compound 1 was found to be irreversible in dilution experiments (Figure 2B). We hypothesized that the mechanism of IDE inhibition involves electrophilic attack upon the sulfur atom within the isothiazolone ring by an active-site thiol, resulting in formation of a disulfide bond (Figure 2C). To confirm this, we conducted mass spectrometric analysis of compound 1 after prolonged incubation with a model thiol, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which yielded results consistent with the proposed mechanism (Figure 2D). Although the mechanism of inhibition involves the irreversible opening of the isothiazolone ring (Figure 2C), the resulting disulfide bond should itself be reversible by reducing agents. Consistent with this prediction, the inhibition of WT-IDE by compound 1 was found to be reversible by treatment with dithiothreitol (DTT; Figure 2E). Moreover, as expected for a thiol-reactive compound, no activity was detected in the presence of excess DTT, ß-mercaptoethanol or reduced glutathione (Supplementary Figure S1A). Similarly, even after prolonged incubation of intact cells with compound 1, intracellular pools of IDE were unaffected (Supplementary Figure S1B), suggesting the compound is inactivated by the reduced intracellular environment.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the mechanism of action of compound 1. A, Inhibition of IDE by compound 1 is cysteine-dependent. B, Compound 1 acts irreversibly. 1 nM IDE is effectively inhibited by “high” concentrations of the reversible inhibitor, Ii123 (30 nM), compound 1 (3 μM) or NEM (2 mM), but not by “low” (100-fold lower) concentrations. However, upon incubation of 100 nM IDE with “high” inhibitor concentrations, followed by 100-fold dilution of the IDE/inhibitor mixture, IDE is inhibited by irreversible compounds (compound 1 and NEM), but not by the reversible inhibitor, Ii1. C, Proposed reaction mechanism. Note that reaction with thiols results in breakage of the isothiazolone ring (irreversible) and the formation of a disulfide bond (reversible). D, Confirmation of proposed reaction mechanism by mass-spectrometry. Compound 1 was reacted for 3 d with equimolar N-acetylcysteine (NAC) then analyzed by ESI-MS, yielding a reactant and product of the expected masses. E, Inhibition of IDE by compound 1 is reversible by treatment with DTT (ßME, 0.5 mM), consistent with the proposed reaction mechanism depicted in C.

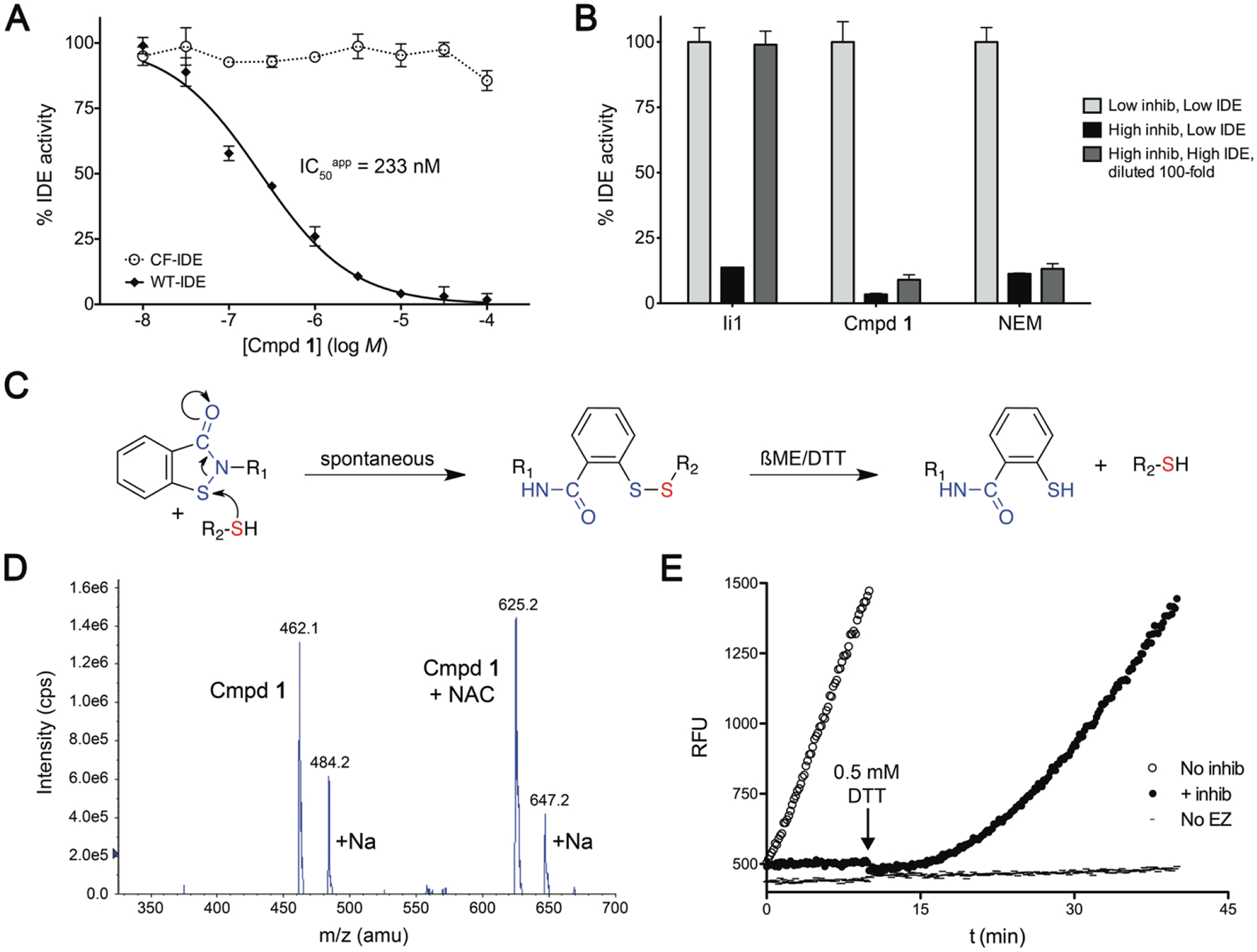

Among the 13 cysteine residues within the principal (non-mitochondrial) isoform of human IDE12, two in particular—C812 and C819—are primarily responsible for the thiol sensitivity of the protease10, 11, due to their position within the active site (Figure 3A). Consequently, mutant forms of IDE containing only a single cysteine (sC) either at position 812 (sC812) or at position 819 (sC819) are both completely inhibited by broad-spectrum thiol-alkylating compounds such as NEM11 (Figure 3B). In marked contrast, compound 1 strongly inhibited the single-cysteine mutant sC819, but had no significant effect on sC812 (Figure 3B). These results support a model wherein IDE inhibition by compound 1 arises not via non-specific modification of any cysteine but instead via preferential interaction with C819, again suggesting that compound 1 forms productive interactions with the enzyme that augment specific binding proximal to C819. Preferential interaction with C819 was also predicted by computational docking of compound 1 with the region of IDE containing both C812 and C819 (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Compound 1 interacts selectively with C819. A, Outer surface (left) and internal chamber (right) of IDE highlighting the relative position of C812 and C819 to the active-site Zn atom. B, Mutants of IDE containing only a single-cysteine at position 812 (sC819) or 819 (sC819) are both effectively inhibited by NEM, but only sC819 is effectively inhibited by compound 1. Note that both compounds inhibit wild-type (WT-IDE) but not cysteine-free IDE (CF-IDE). *p < 0.05.

The potency of irreversible inhibitors is determined by the combined contribution of two distinct kinetic parameters: KM, the dissociation constant for the reversible interaction of the inhibitor with the enzyme; and kinhib, the rate constant for the irreversible reaction—in this case, ring opening and formation of the disulfide bond (Figure 2C). These parameters can be calculated by analyzing the time-dependence of enzyme inhibition as a function of inhibitor concentration. As derived in detail elsewhere21, kinhib represents the theoretical maximum rate constant (i.e., at infinite inhibitor concentration), and KM represents the concentration of inhibitor at which kinhibobs is 50% of kinhib. For compound 1, KM and kinhib were determined to be 4.34 μM and 2.05 min−1, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

SAR of derivatives of compound 1 and kinetic properties thereof.

| Cmpd | R1 | KM (μM) | kinhib (min−1) | IC50app (μM) cell-free | IC50app (μM) cell-based |

ki (μM) CF-IDE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 4.34 | 2.05 | 0.21 | 1.4 | 8.18 |

| 8 | F | 4.47 | 13.4 | 0.063 | 0.11 | 8.37 |

| 9 | CF3 | 4.61 | 15.3 | 0.071 | 0.12 | 7.89 |

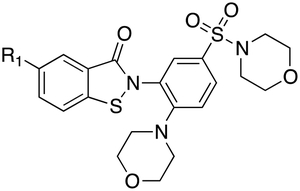

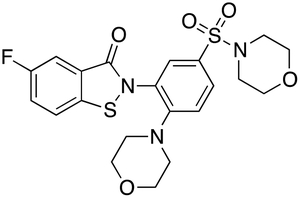

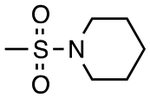

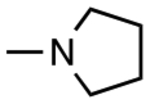

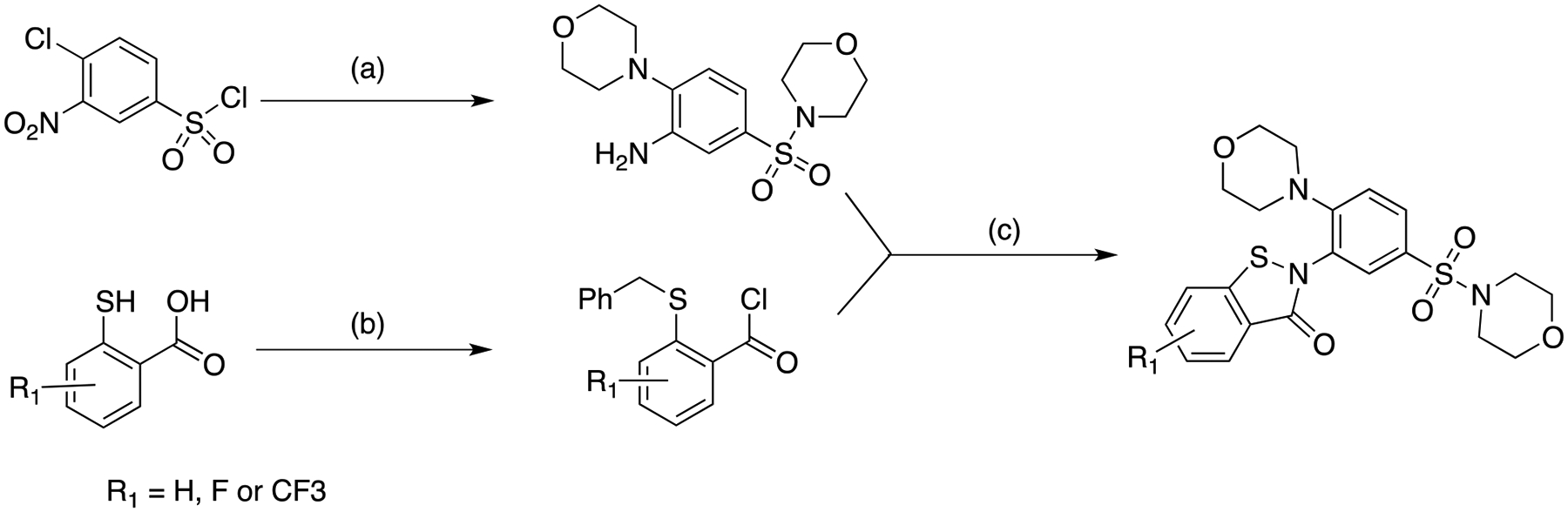

By comparison of the assay values for compounds 6 and 7 (Table 1), we hypothesized that the potency of compound 1 could be improved by introducing an electron withdrawing group to the phenyl ring of the benzoisothiazolone moiety. A fluorine group would be predicted to promote thiol reactivity, accelerating the irreversible step and so increasing kinhib. To test this empirically, we synthesized derivatives of compound 1 with an F or CF3 group present (compounds 8 and 9, respectively) (Table 2; Scheme 1). As hypothesized, the added groups gave significant (3- to 12-fold) improvements in potency relative to compound 1 (Table 2). Notably, these increases in potency were entirely attributable to increases in kinhib (Table 2). To establish this point by an alternative method, the ki values for compounds 1, 8 and 9 were determined using CF-IDE and were not found to differ significantly from one another (Table 2), albeit the latter values were all nominally higher than the KM values obtained for WT-IDE, presumably due to the substitution of serine at position 819 in CF-IDE, which is larger and less hydrophobic than the native cysteine residue.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route used for generation of compounds 1, 8 and 9.

(a) 1. Et3N, morpholine; 91%; 2. H2, Pd/C; 85%

(b) NaOH, PhCH2Br; 92% for compound 1, 88% for compound 8, 94% for compound 9; 2. (COCl)2, CH2Cl2;

(c) EtNiPr2, CH2Cl2; 2. Phl(OCOCF3)2, TFA, CH2Cl2, preparative HPLC purification; 51% for compound 1, 40% for compound 8, 43% for compound 9

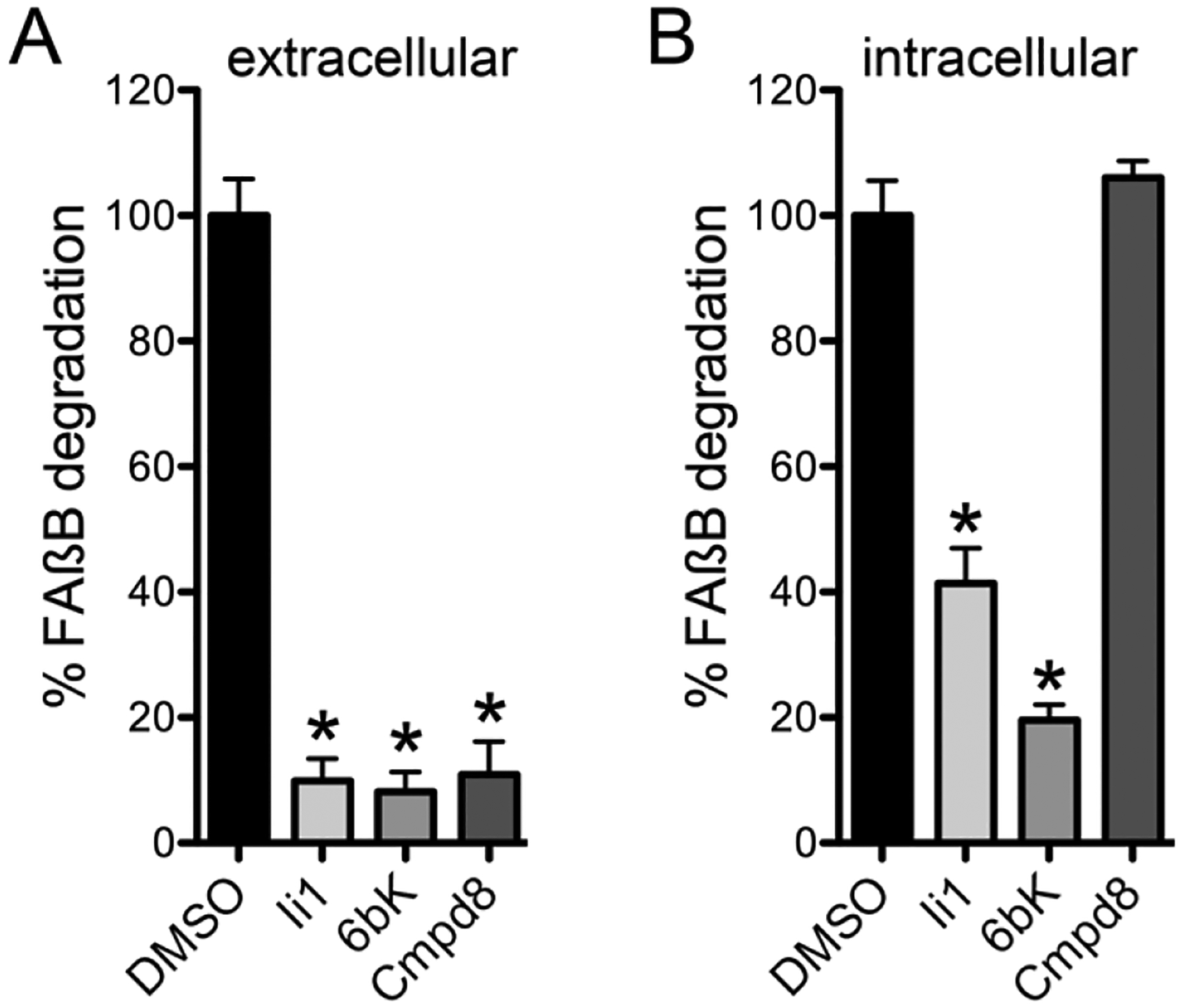

Compound 8, which exhibits lower IC50app, MW and LogP values than compound 9, was further profiled, with the properties presented in Table 3. In particular, compound 8 inhibited the degradation of insulin with a potency (IC50app = 82 ± 20.2 nM) similar to that obtained with FRET1 and Aß, showed no toxicity in cells up to 100 μM, and showed minimal reactivity with cysteines in a proteome-wide, activity-based protein-profiling assay22. To highlight a key functional property of compound 8—namely, its ability to selectively inhibit extracellular pools of IDE—the compound was compared to two other IDE inhibitors, Ii123 and 6bK6, in terms of their ability to inhibit extracellular and intracellular pools of IDE in BV-2 cells, a microglial cell line that expresses abundant IDE24 (see Methods). While extracellular IDE was inhibited strongly by all compounds tested (Figure 5A), intracellular pools of IDE were found to be inhibited by Ii1 and 6bK, but not by compound 8 (Figure 5B). Additionally, chemo-informatic analyses establish that compound 8 is fully compliant with multiple criteria for drug-likeness, including Lipinski’s Ro516, Jorgensen’s rule of 3 (Ro3)25, as well as the Ghose26 and Veber27 filters, criteria that are not satisfied by previously described IDE inhibitors (Supplementary Table S1). Compound 8, also designated ML345, has been accepted as a molecular probe by the NIH Molecular Probe Center Network28.

Table 3.

Biochemical, chemical, and pharmacological properties of compound 8.

| CID | 57390068 |

| Molecular formula | C21H22FN3O5S2 |

| IC50app in vitro, FRET1 (nM) | 63 ± 8.1 (n=5) |

| IC50app in vitro, insulin (nM) | 82 ± 20.2 (n=4) |

| IC50app in cells, FAßB (nM) | 110 ± 12 (n=4) |

| KM (μM) | 4.47 ± 1.06 (n=5) |

| kinhib (min−1) | 13.4 ± 2.7 (n=5) |

| MW | 479.5 |

| cLogP | 2.4 |

| cLogD 7.4 | 2.0 |

| H donors | 0 |

| H acceptors | 9 |

| tPSA (Å 2 ) | 113 |

| HAa count | 32 |

| LE b | 0.234 |

| BEI c | 15 |

| SEI d | 4.73 |

| Ro5 compliant? | yes |

| Chemical stability in PBS | >> 48 hr. |

| Solubility in assay buffer (μM) | 5.1 |

| Liver microsome stability, Human /Rat / Mouse (min) | >120 / 50 / 24 |

| HEK toxicity EC 50 | >100 μM |

HA=heavy atoms (non-hydrogen atoms).

LE=ligand efficiency (ΔG/HA), calculated using KM value (units of kcal mol−1 HA−1).

BEI=binding efficiency index (pIC50app/MW, kDa).

SEI=surface efficiency index (pKM/tPSA/100 Å2).

Figure 4.

Compound 8 selectively targets extracellular IDE. Effects of compound 8 versus Ii1 and 6bK on extracellular (A) and intracellular (B) pools of IDE evaluated in BV-2 cells (see Methods). IDE activity was detected using a fluoresceinated and biotinylated Aß peptide (FAßB) as described17. Note that, in contrast to Ii1 and 6bK, compound 8 does not affect intracellular pools of IDE. Data are mean ± SEM for 3 replications. *p < 0.05.

The benzoisothazalone-based IDE inhibitors described in this study—in addition to being the first small-molecule, nonpeptidic, truly drug-like inhibitors of IDE yet developed—are of special interest because of their unique, “quasi-irreversible” mechanism of action, which confers a number of unusual characteristics. While the benzoisothiazolones are cysteine-modifying agents, they differ markedly from NEM or other conventional thiol-alkylating agents in being significantly more potent (e.g., >1000-fold more potent than NEM) and non-toxic in long-term cell culture (e.g., CC50 >100 μM in HEK-293 cells treated for 48 h). These two features, in turn, appear to be attributable to a unique combination of properties. First, compound 8 exhibits strong affinity not just for IDE as a whole, but more specifically for a particular cysteine within the active site of IDE (C819). Because the selectivity of these compounds depends on the particular ensemble of substituents present, these groups may act both by facilitating binding to the region surrounding C819 in IDE and possibly also by sterically blocking interactions with off-target thiols. Second, the rate of the irreversible step in the reaction (kinhib) is relatively slow (~2 to 13 min−1). This property should serve to minimize the adventitious interaction with off-target thiols, limiting productive interactions to those involving a considerable residence time. Third, in contrast to the essentially irreversible S-C bond formed by thiol-alkylating agents, the S-S bond made by the compounds in this series is reversible. This feature likely also contributes to the lack of toxicity, by making any off-target interactions that do occur relatively transient. Notably, because these compounds are inactivated under the reducing conditions present in the cytosol, their activity is limited to the extracellular space, thus greatly reducing the number of potentially toxic off-target interactions. The latter property also distinguishes compound 8 from previously described inhibitors of IDE by enabling it to selectively target extracellular pools of IDE.

In conclusion, through a high-throughput compound screening campaign, medicinal chemistry optimization, and coordinated biochemical mechanistic- and kinetics-based studies, we have developed a potent and mechanistically distinctive IDE inhibitor that selectively targets extracellular pools of IDE, compound 8. This compound is the first small-molecule, nonpeptidic, drug-like inhibitor of IDE, is the first non-toxic, irreversible IDE inhibitor yet described, and shows selectivity not just for IDE, but also for a specific cysteine residue within the protease’s active site (C819). Importantly, by utilizing a quasi-irreversible mode of inhibition, compound 8 exclusively inhibits the extracellular pool of IDE. Compound 8 will therefore be highly useful for future studies investigating the relative contribution of intracellular versus extracellular pools of IDE to different physiological processes and pathological conditions.

Methods

Compound screening.

Detailed descriptions of the overall screening campaign (AID 434984), including the primary cell-based activity screen (AID 434962), confirmatory activity screens (AIDs 435028, 463220, 588712), cytotoxicity assays (AIDs 449730, 463221, 588709), cell-free activity assays (AIDs 588711 and 624067), counterscreens for fluorescence artifacts (AIDs 588718 and 624353), and confirmatory activity assays with a fluorogenic peptide substrate using WT-IDE (AIDs 624066 and 624340) or CF-IDE (AID 624338) are available from PubChem via the Internet at http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Insulin degradation was quantified using a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence-based assay (CisBio Bioassays) as described23. DTT-free solutions were used for all assays.

Tests for irreversible inhibition.

Activity assays were conducted using the FRET1 substrate essentially as described20 under 3 different conditions: 1) using 1 nM WT-IDE in the presence of “high” inhibitor concentrations (30 nM Ii1; 3 μM compound 1, 2 mM NEM); 2) using 1 nM WT-IDE in the presence of “low” inhibitor concentrations (100-fold lower, or 0.3 nM Ii1, 30 nM compound 1, 20 μM NEM); and using 100 nM WT-IDE first incubated with “high” inhibitor concentrations for 30 min, then diluted 100-fold (to 1 nM WT-IDE and “low” inhibitor concentrations) prior to execution of the activity assay. Irreversible inhibitors in the latter condition retain their inhibitory potential despite dilution to the “low” concentration.

Confirmation of reaction mechanism by mass spectrometry.

Compound 1 and NAC were combined in PBS at equimolar concentrations (50 mM) and incubated at 22 °C for 3 d. The masses of the constituents were subsequently analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry as described29.

Tests for efficacy in the presence of reducing agents and on intracellular pools of IDE.

IDE activity in the presence of DTT, ßME and GSH was assayed as described20, using the FRET1 substrate. Intracellular and extracellular IDE activity were quantified in HEK and BV-2 cell lines. For experiments with HEK cells, confluent cell monolayers were incubated for 36 h in the presence of compound 1 (10 μM) or vehicle (DMSO). The conditioned medium was collected for quantification of extracellular IDE activity. After washing the cells 3 times in PBS, intracellular pools of IDE were recovered by incubating intact cells for 30 min in a hypotonic solution (50 mM Tris-HCl) at 4 °C, collecting them by scraping, followed by mechanical disruption by extrusion 3 times through a 30G hypodermic needle and centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. For experiments with HEK cells, IDE activity in the latter supernatant and in the conditioned medium were quantified in the absence or presence of DTT (1 mM) as described17. Experiments with BV-2 cells were conducted essentially as above, except that cells were treated for 16 h with inhibitor concentrations of 30 μM. Cell extracts were diluted only modestly (1:200; v:v) so that even reversible inhibitors, if cell-penetrant, would be sufficiently concentrated to be active in the final assay. IDE activity in conditioned medium and cell extracts was quantified using the avidin-agarose precipitation version of a well-established Aß degradation assay described previously17.

Determination of kinetics of irreversible inhibition.

Activity assays were conducted using recombinant WT-IDE (2 nM) and FRET1 substrate (5 μM) in the presence of different concentrations of inhibitors. Reactions were monitored continuously at 3-s intervals immediately after addition of inhibitor as described20. Observed rate constants (kinhibobs) were obtained by fitting curves to the resulting data, which were subsequently plotted as a function of inhibitor concentration. Hyperbolic curves were fitted to the latter data to obtain kinhib and KM as described30, according to the following formula:

Curve fits and quantitative analyses were conducted using Prism 5.0 (Graphpad Software, Corp.).

Computational docking.

Docking was performed using Glide (v. 5.6) within the Schrödinger software suite (Schrödinger, LLC)31. The starting conformation of ligands was obtained by the method of Polak-Ribière conjugate gradient (PRCG) energy minimization with the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) 2005 force field32 for 5000 steps, or until the energy difference between subsequent structures was less than 0.001 kJ/mol-Ǻ (ref. 31). Our docking methodology has been described previously33–35, and the scoring function utilized as well as the rationale for its selection is described elsewhere36. Briefly, in order to generate the grids for docking, the ions, molecular refracting molecules, and 1,4-diethylene dioxide were removed from the IDE crystal structure (PDB Code 3E4A)23. Schrödinger’s SiteFinder module was used to determine grid placement for the region of C812 and C819. The binding site was generated via multiple overlapping grids with a default rectangular box. Then a larger composite grid was generated such that both C812 and C819 were contained within the grid. Using this grid, compound 1 was docked using the Glide algorithm within the Schrodinger suite as a virtual screening workflow (VSW). The docking proceeded from lower precision through SP docking and Glide extra precision (XP) (Glide, v. 5.6, Schrödinger, LLC)37, 38. The top 10,000 poses were ranked for best scoring pose and unfavorable scoring poses were discarded. Each conformer was allowed multiple orientations in the site. Site hydroxyls, such as in serines and threonines, were allowed to move with rotational freedom. The induced-fit docking method was utilized within Schrödinger suite to allow larger side-chain re-orientation, as needed. Hydrophobic patches were utilized within the VSW as an enhancement. Top favorable scores from dockings of compound 1 yielded 10 poses. XP descriptors were used to obtain atomic energy terms like hydrogen bond interaction, electrostatic interaction, hydrophobic enclosure and pi-pi stacking interaction that result during the docking run37, 38. Figures were generated using Maestro, the built-in graphical user interface of the Schrodinger software suite (v. 5.6) (Schrödinger, LLC).

Chemoinformatics analyses.

To evaluate the drug-likeness of compounds, physicochemical and other drug-related properties, including compliance with Lipinski’s Ro5 and Jorgensen’s Rule of 3 (Ro3), were calculated using QikProp25 (v. 4.0) within the Schrödinger software suite (Schrödinger, LLC). Adherence to the Ghose and Veber filters was calculated as described26, 27.

Synthesis of compounds.

All chemical reagents and solvents were acquired from commercial vendors. Reactions were monitored by LC/MS (Thermo/Finnegan LCQ Duo ion trap system with MS/MS capability). An Agilent 1200 analytical HPLC was used for quantitative purity assessment. Teledyne-Isco “combiflash” automated silica gel MPLC instruments were used for chromatographic purifications. A Brüker 400-MHz NMR instrument was used for NMR analysis. A Shimadzu preparative HPLC instrument was used for final compound purification. Analytical HPLC data used an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column, 4.6×150mm. The HPLC solvents used were acetonitrile and water with 0.1% formic acid added to each mobile phase as the pH modifier. HRMS data was collected on samples of the previously undescribed compounds 8 and 9 at the University of Illinois, using TOF and ESI mass spectrometry.

5-fluoro-2-(2-morpholin-4-yl-5-morpholin-4-ylsulfonylphenyl)-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one (8)

This compound was synthesized in a convergent manner, in six steps overall, with the longest linear sequence being 4 steps, as summarized in Scheme 1. The overall yield of the process (after preparative HLPC purification of the final product) is 26%. The 400-MHz 1H NMR spectrum is depicted in Supplementary Figure S3, and the analytical HPLC in Supplementary Figure S4.

Step 1.

A mixture of sulfonyl chloride A (2.36 g, 10 mmol) and triethylamine (5.06 g, 50.0 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was treated with dropwise with morpholine (2.61g, 30 mmol) at room temperature. After addition was complete the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 14 h, quenched with saturated NH4Cl, and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic extracts were washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (Hexanes: ethyl acetate = 1:1, Rf= 0.15) to afford 3.261 g (91%) of compound B as a yellow solid. Calc’d for C14H19N3O6S: 357.1; found [M+H]+: 358.0; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 3.03–3.06 (m, 4H), 3.21–3.23 (m, 4H), 3.76–3.79 (m, 4H), 3.87–3.89 (m, 4H), 7.18 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (dd, J=2.0, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (d, J=2.0 Hz, 1H).

Step 2.

To a solution of compound B (488 mg, 1.37 mmol) in THF (10 mL) and MeOH (10 mL) was added Pd/C (10%, 50 mg). The reaction mixture was then stirred under atmosphere of H2 for 5 h, filtered and concentrated to afford 378 mg (85%) of compound C as white solid. Calc’d for C14H21N3O4S: 327.1; found [M+H]+: 328.1.

Step 3.

A solution of Acid D (344 mg, 2.0 mmol) in MeOH (12 mL) was treated with NaOH (160 mg, 4.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. The solvent was removed to afford a solid which was dissolved in acetone (18 mL). Benzyl bromide (376 mg, 2.2 mmol) was added. The reaction was sonicated for 5 min and then stirred at 0 °C for 1 h. The precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration. The solid was dissolved in H2O and then treated with 1 N HCl. The precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration and dried in air, affording 462 mg (88%) of compound E as white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6) δ (ppm) 4.25 (s, 2H), 7.27–7.36 (m, 4H), 7.45–7.47 (m, 2H), 7.54–7.57 (m, 1H), 7.70–7.73 (m, 1H).

Steps 4 and 5.

A suspension of acid E (570 mg, 2.17 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (24 mL) was treated with (COCl)2 (441 mg, 3.48 mmol) and a drop of DMF at 0 °C under atmosphere of N2. The reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, and then room temperature for 3 h. The solvent was removed. The residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (24 mL). Compound C (781 mg, 2.39 mmol) was added and cooled to 0 °C. Diisopropylethylamine (841 mg, 6.51 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, quenched with H2O, extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by flash column (hexanes: ethyl acetate = 1:1, Rf = 0.20) to afford 1.04 g (84%) of compound F as a yellow solid. Calc’d for C28H30FN3O5S2: 571.1; found [M+H]+: 572.0;. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 2.93–2.95 (m, 4H), 3.13–3.15 (m, 4H), 3.78–3.83 (m, 8H), 4.05 (s, 2H), 7.07–7.09 (m, 3H), 7.19–7.20 (m, 3H), 7.30–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.58–7.60 (m, 2H), 8.92 (br s, 1H); 19F NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) −111.6.

Step 6.

A mixture of [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]benzene (PIFA, 1.02 g, 2.36 mmol) and TFA (0.415 g, 3.64 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (18 mL) was cooled to 0 °C under atmosphere of N2. A solution of compound 6 (1.04 g, 1.82 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (35 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, room temperature 30 min, and then refluxed for 40 h. The crude product was concentrated and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes : ethyl acetate = a gradient of 1:1 to 1:4) and then by preparative HPLC to afford 343 mg (40%) of compound 8 (ML345) as a white solid. Calc’d for M+H = C21H23FN3O5S2: 480.1; found [M+H]+: 479.9; HRMS calc’d for M+H = C21H23FN3O5S2: 480.1063; found [M+H]+: 480.1060; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) 2.98–3.01 (m, 8H), 3.67–3.71 (m, 8H), 7.11 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.48–7.52 (m, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J=2.4, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J=2.4, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J=2.0 Hz, 1H); 19F NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) −115.4. Purity was measured at >98% (LC/MS analysis, confirmed by analytical HLPC analysis; HPLC purity data is shown in Figure S3).

2-(2-morpholin-4-yl-5-morpholin-4-ylsulfonylphenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one (9)

Synthesis was carried out in the same manner as reported for compound 8 (Scheme 1). HRMS Calc’d for M = C22H22F3N3O5S2: 529.0953; found [M]+: 529.0952. Purity was measured at >98% (LC/MS analysis, confirmed by analytical HLPC analysis).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Becky Mercer, Katherine Emery and Jill Ferguson for assistance with the management of data and submission to PubChem, Hugh Rosen and William Roush for program support, Sebastian Newlove for purification of recombinant IDE, and Juan Pablo Maianti, Alan Saghatelian and David Liu for providing 6bK.

Funding Sources

Supported by grant DA024888 from the NIH and grant 7-11-CD-06 from the American Diabetes Association to M.A.L. and grant U54 MH084512 from the NIH to T.D.B., H.W., M.C., S.C.S., F.M., P.H.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CF-IDE

cysteine-free IDE

- IDE

insulin-degrading enzyme

- MLSMR

Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- Ro5

Lipinski’s Rule of Five

- WT-IDE

wild-type IDE

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Drug-like properties of compound 8 vis-à-vis other IDE inhibitors; activity of compound 1 in the presence of reducing agents, and effects of compound 1 on intracellular IDE activity; computational docking results for compound 1; 400-MHz 1H NMR spectrum; and analytical HLPC for compound 8. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- [1].Leal MC, and Morelli L (2013) Insulysin, In Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes (Rawlings ND, and Salvesen G, Eds.) 3rd ed., pp 1415–1420, Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hersh LB (2006) The insulysin (insulin degrading enzyme) enigma, Cell Mol Life Sci 63, 2432–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shii K, and Roth RA (1986) Inhibition of insulin degradation by hepatoma cells after microinjection of monoclonal antibodies to a specific cytosolic protease, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83, 4147–4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Edbauer D, Willem M, Lammich S, Steiner H, and Haass C (2002) Insulin-degrading enzyme rapidly removes the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD), J Biol Chem 277, 13389–13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].van Endert P (2011) Post-proteasomal and proteasome-independent generation of MHC class I ligands, Cell Mol Life Sci 68, 1553–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maianti JP, McFedries A, Foda ZH, Kleiner RE, Du XQ, Leissring MA, Tang WJ, Charron MJ, Seeliger MA, Saghatelian A, and Liu DR (2014) Anti-diabetic activity of insulin-degrading enzyme inhibitors mediated by multiple hormones, Nature 511, 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Makarova KS, and Grishin NV (1999) The Zn-peptidase superfamily: functional convergence after evolutionary divergence, J Mol Biol 292, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Becker AB, and Roth RA (1992) An unusual active site identified in a family of zinc metalloendopeptidases, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 3835–3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Williams FG, Johnson DE, and Bauer GE (1990) [125I]-insulin metabolism by the rat liver in vivo: evidence that a neutral thiol-protease mediates rapid intracellular insulin degradation, Metabolism 39, 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Malito E, Ralat LA, Manolopoulou M, Tsay JL, Wadlington NL, and Tang WJ (2008) Molecular bases for the recognition of short peptide substrates and cysteine-directed modifications of human insulin-degrading enzyme, Biochemistry 47, 12822–12834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Neant-Fery M, Garcia-Ordonez RD, Logan TP, Selkoe DJ, Li L, Reinstatler L, and Leissring MA (2008) Molecular basis for the thiol sensitivity of insulin-degrading enzyme, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 9582–9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Leissring MA, Farris W, Wu X, Christodoulou DC, Haigis MC, Guarente L, and Selkoe DJ (2004) Alternative translation initiation generates a novel isoform of insulin-degrading enzyme targeted to mitochondria, Biochem J 383, 439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhao J, Li L, and Leissring MA (2009) Insulin-degrading enzyme is exported via an unconventional protein secretion pathway, Mol Neurodegener 4, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bulloj A, Leal MC, Xu H, Castano EM, and Morelli L (2010) Insulin-degrading enzyme sorting in exosomes: a secretory pathway for a key brain amyloid-beta degrading protease, J Alzheimers Dis 19, 79–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Goldfine ID, Williams JA, Bailey AC, Wong KY, Iwamoto Y, Yokono K, Baba S, and Roth RA (1984) Degradation of insulin by isolated mouse pancreatic acini. Evidence for cell surface protease activity, Diabetes 33, 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, and Feeney PJ (2001) Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 46, 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Leissring MA, Lu A, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Stein RL, Farris W, and Selkoe DJ (2003) Kinetics of amyloid beta-protein degradation determined by novel fluorescence- and fluorescence polarization-based assays, J Biol Chem 278, 37314–37320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner MR, and Tang WJ (2006) Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism, Nature 443, 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang JH, Chung TD, and Oldenburg KR (1999) A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays, J Biomol Screen 4, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cabrol C, Huzarska MA, Dinolfo C, Rodriguez MC, Reinstatler L, Ni J, Yeh L-A, Cuny GD, Stein RL, Selkoe DJ, and Leissring MA (2009) Small-molecule activators of insulin-degrading enzyme discovered through high-throughput compound screening, PLoS ONE 4, e5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mallender WD, Szegletes T, and Rosenberry TL (1999) Organophosphorylation of acetylcholinesterase in the presence of peripheral site ligands. Distinct effects of propidium and fasciculin, J Biol Chem 274, 8491–8499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bachovchin DA, Zuhl AM, Speers AE, Wolfe MR, Weerapana E, Brown SJ, Rosen H, and Cravatt BF (2011) Discovery and optimization of sulfonyl acrylonitriles as selective, covalent inhibitors of protein phosphatase methylesterase-1, J Med Chem 54, 5229–5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Leissring MA, Malito E, Hedouin S, Reinstatler L, Sahara T, Abdul-Hay SO, Choudhry S, Maharvi GM, Fauq AH, Huzarska M, May PS, Choi S, Logan TP, Turk BE, Cantley LC, Manolopoulou M, Tang WJ, Stein RL, Cuny GD, and Selkoe DJ (2010) Designed inhibitors of insulin-degrading enzyme regulate the catabolism and activity of insulin, PLoS One 5, e10504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qiu WQ, Walsh DM, Ye Z, Vekrellis K, Zhang J, Podlisny MB, Rosner MR, Safavi A, Hersh LB, and Selkoe DJ (1998) Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates extracellular levels of amyloid beta-protein by degradation, J Biol Chem 273, 32730–32738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jorgensen WL, and Duffy EM (2002) Prediction of drug solubility from structure, Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54, 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ghose AK, Viswanadhan VN, and Wendoloski JJ (1999) A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases, Journal of combinatorial chemistry 1, 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, and Kopple KD (2002) Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates, J Med Chem 45, 2615–2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bannister TD, Wang H, Abdul-Hay SO, Masson A, Madoux F, Ferguson J, Mercer BA, Schurer S, Zuhl A, Cravatt BF, Leissring MA, and Hodder P (2010) ML345, A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of the Insulin-Degrading Enzyme (IDE), In Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program, Bethesda (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abdul-Hay SO, Sahara T, McBride M, Kang D, and Leissring MA (2012) Identification of BACE2 as an avid ß-amyloid-degrading protease, Mol Neurodegener 7, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rosenberry TL, Sonoda LK, Dekat SE, Cusack B, and Johnson JL (2008) Analysis of the reaction of carbachol with acetylcholinesterase using thioflavin T as a coupled fluorescence reporter, Biochemistry 47, 13056–13063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mohamadi F, Richard NGJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, and Still WC (1990) Macromodel—an integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics, J Comput Chem 11, 440–467. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jorgensen WL, and Tiradorives J (1988) The OPLS Potential Functions for Proteins - Energy Minimizations for Crystals of Cyclic-Peptides and Crambin, Journal of the American Chemical Society 110, 1657–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Caulfield TR, and Devkota B (2012) Motion of transfer RNA from the A/T state into the A-site using docking and simulations, Proteins. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Loving K, Salam NK, and Sherman W (2009) Energetic analysis of fragment docking and application to structure-based pharmacophore hypothesis generation, J Comput Aided Mol Des 23, 541–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vivoli M, Caulfield TR, Martinez-Mayorga K, Johnson AT, Jiao GS, and Lindberg I (2012) Inhibition of prohormone convertases PC1/3 and PC2 by 2,5-dideoxystreptamine derivatives, Mol Pharmacol 81, 440–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Friesner RA, Murphy RB, Repasky MP, Frye LL, Greenwood JR, Halgren TA, Sanschagrin PC, and Mainz DT (2006) Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes, J Med Chem 49, 6177–6196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Salam NK, Nuti R, and Sherman W (2009) Novel method for generating structure-based pharmacophores using energetic analysis, J Chem Inf Model 49, 2356–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Caulfield T, and Medina-Franco JL (2011) Molecular dynamics simulations of human DNA methyltransferase 3B with selective inhibitor nanaomycin A, J Struct Biol 176, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.