Abstract

目的

对鼻骨骨折患者进行相关的临床流行病学概括和分析。

方法

回顾性总结2 881例鼻骨骨折住院患者的临床资料,并对其性别、年龄、骨折类型、致伤原因等情况进行综合分析。采用Fred分型方法对鼻骨骨折进行分型,采用SPSS 25.0软件完成统计分析。

结果

鼻骨骨折男女比例为2.44:1,总体男性患者多于女性。19~29岁组鼻骨骨折患者最多(35.54%)。交通事故伤发生率最高(33.84%),其次是暴力打击伤(24.12%)。统计分析表明,鼻骨合并上颌骨额突骨折患者多于单纯性鼻骨骨折患者,Ⅱ型鼻骨骨折患者明显多于其他骨折类型患者。对单纯性鼻骨骨折进行Logistic回归分析发现,男性发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较低。且随着患者年龄的增长,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的风险降低。相对于车祸伤而言,病因为暴力伤、运动伤、撞伤时,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较高。

结论

鼻骨骨折住院患者在个体特征、创伤原因、部位等方面具有一定的分布规律,应深入展开相关防治性的策略研究。

Keywords: 鼻骨骨折, 流行病学, 回顾性研究

Abstract

Objective

This thesis studies on epidemiological characteristics of patients with nasal bone fractures.

Method

This thesis retrospectively studies on 2 881 patients with nasal bone fractures. The characteristics, causes, and fracture types are collected and reviewed retrospectively. The type of nasal bone fracture is classified according to Fred's classification, and SPSS 25.0 software is used in statistical analysis.

Result

The sex ratio of nasal bone fracture between males and females is 2.44 : 1, male cases are obviously more than female cases. The group aged 19-29 years occupies the largest proportion, accounted for 35.54%. Traffic accident was the leading cause of the nasal bone fracture, accounting for 33.84%. The second cause was violent assault, 24.12% totally. The number of patients suffering nasal bone fractures combined with maxilla frontal process fractures is higher than that of simple nasal bone fractures. Type Ⅱ fracture is significantly more common in patients with other types nasal bone fractures. Logistic regression analysis for simple nasal bone fracture showed that the relative risk of simple nasal bone fracture is lower in men than in women, and the risk of simple nasal fractures decreased with age increasing. Compared with traffic accident, the relative risk of simple nasal bone fracture is higher in violence injury, sports injury and collision injury.

Conclusion

The distribution of the nasal fractures of the inpatients has certain characteristics in terms of individual characteristics, injury cause and fracture types, which is worthy of further strategic study on prevention and treatment of the nasal fractures.

Keywords: nasal bone fracture, epidemiology, retrospective study

鼻骨是鼻面部骨软骨支架的重要构成部分,突出于面部的中央,其结构菲薄,在外力的作用下极易发生骨折〔1-4〕。当鼻骨发生骨折,患者面部外观受损的同时,鼻的通气功能也受到影响,甚至许多毗邻的重要器官例如眼、脑、神经等也可能受累。鼻骨骨折的发生受多种因素的影响,包括各种致伤病因〔4〕、外力的作用大小和部位〔5-6〕、甚至患者的性别和年龄等〔7-8〕。目前其流行病学调查已日益受到重视〔2, 8-9〕,而国内对其进行的相关研究并不多见。故本研究回顾性分析我院近几年收治的鼻骨骨折患者的临床资料,总结并阐明其流行病学特点,为鼻骨骨折的防治提供参考,同时有助于制定更加完善的诊疗方案。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 资料收集

收集上海交通大学医学院附属第九人民医院耳鼻咽喉头颈外科2013-06-2018-07收治的全部鼻骨骨折相关住院患者的病历资料,查找到有详细病案记载的鼻骨骨折相关患者2 881例。通过数据库采集其一般情况、致伤原因、骨折部位、骨折分型等相关临床资料。本研究已通过伦理委员会审查,项目编号:2016-81-T38。

1.2. 分型方法

考虑到Fred分型具有临床实用性且易于评估,故本研究采用Fred分型〔10〕方法对鼻骨骨折进行重新分型,将鼻骨骨折患者分为Ⅰ型、Ⅱ型、Ⅲ型(Ⅲa、Ⅲb、Ⅲc)、Ⅳ型,分别统计各骨折分型人数及性别比例等信息(图 1)。

图 1.

鼻骨骨折分型

1a:Ⅰ型,单纯线性骨折(单侧或双侧),未导致鼻中线偏曲或移位的单侧或双侧鼻骨骨折;1b:Ⅱ型,单纯错位性骨折(单侧或双侧),导致轻微的鼻中线偏曲或者错位,或者伴有继发性鼻中隔骨折或移位;Ⅲ型:严重的鼻骨及鼻中隔骨折;1c:Ⅲa,单侧骨折;1d:Ⅲb,双侧骨折;1e:Ⅲc,粉碎性骨折(伴有严重的鼻中线偏曲或移位的单侧或双侧鼻骨骨折,并且继发严重的鼻中隔骨折或脱位,粉碎的鼻骨或中隔可能会妨碍骨折复位);1f:Ⅳ型,鼻骨及鼻中隔复合型骨折,伴有严重的撕裂伤、软组织撕脱伤、开放性复合型损伤或严重的鞍鼻。

1.3. 统计学处理

采用SPSS 25.0软件完成统计分析。定量指标以x±s表示,定性指标以构成比表示。对构成比进行χ2检验,无序分类变量采用χ2检验或χ2分割进行分析。对于单纯性鼻骨骨折进行多因素Logistic回归分析。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 一般情况

2.1.1. 性别及年龄分布

2 881例鼻骨骨折患者中,男2 043例,女838例,男女性别比为2.44:1;年龄2~81岁,平均(29.79± 12.81)岁。根据年龄将患者分为≤12岁组,13~18岁组,19~29岁组,30~39岁组,40~49岁组,50~59岁组,≥60岁组。对各年龄组采用χ2检验,差异有统计学意义(χ2=32.955,P < 0.01)。其中,19~29岁组鼻骨骨折人数最多;各年龄组男性患者人数均多于女性,男女比例分别为2.03:1、4.63:1、2.47:1、2.08:1、1.97:1、3.47:1、3.50:1。见表 1。

表 1.

年龄分组

| 组别 | 性别 | 合计 | 构成比/% | |

| 男 | 女 | |||

| ≤12岁组 | 152 | 75 | 227 | 7.88 |

| 13~18岁组 | 241 | 52 | 293 | 10.17 |

| 19~29岁组 | 729 | 295 | 1024 | 35.54 |

| 30~39岁组 | 493 | 237 | 730 | 25.34 |

| 40~49岁组 | 254 | 129 | 383 | 13.29 |

| 50~59岁组 | 132 | 38 | 170 | 5.90 |

| ≥60岁组 | 42 | 12 | 54 | 1.87 |

| 合计 | 2 043 | 838 | 2 881 | 100.00 |

2.1.2. 季节分布

各个季节鼻骨骨折患者人数分布均匀,其中春季(3、4、5月)708例,占24.57 %;夏季(6、7、8月)721例,占25.03 %;秋季(9、10、11月)739例,占25.65 %;冬季(12、1、2月)713例,占24.75 %。对各季度鼻骨骨折患者构成比进行χ2检验,差异无统计学意义(χ2=0.671,P>0.05)。

2.2. 病因分析

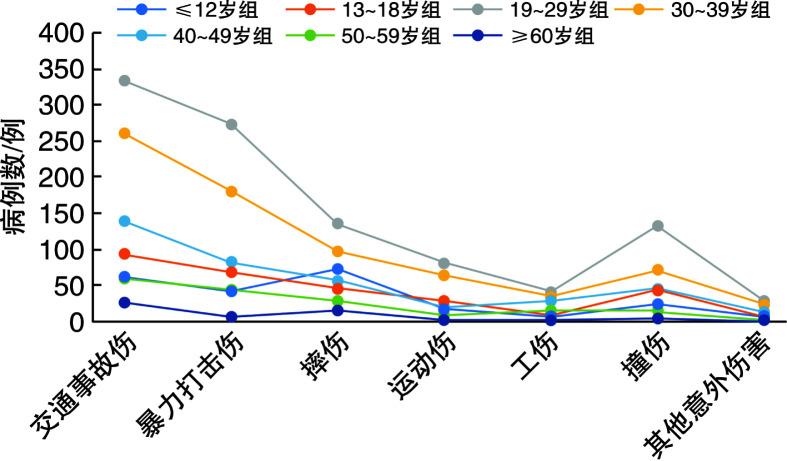

鼻骨骨折的发生原因以交通事故伤最多,共975例(33.84%);其后依次是暴力打击伤695例(24.12%),摔伤448例(15.55%),运动伤219例(7.60%),工伤133例(4.62%),撞伤332例(11.52%),其他意外伤害79例(2.74%)。统计分析显示,不同致伤原因的分布差异有统计学意义(χ2=1 532.496,P < 0.01);不同年龄组所对应鼻骨骨折患者分布亦有所不同(χ2=108.620,P < 0.05)。在各年龄组中,19~29岁组患者人数最多(图 2)。

图 2.

不同年龄组对应病因分布

2.3. 骨折情况

2.3.1. 骨折分型

根据患者受伤后的影像学资料并应用Fred分型方法进行分型,2 881例骨折患者中,Ⅱ型2 396例(83.17%);Ⅲ型418例(14.51%),其中Ⅲa型88例(3.05%)、Ⅲb型259例(8.99%)、Ⅲc型71例(2.46%);Ⅳ型67例(2.33%)。采用χ2分割对构成比进行两两比较,Ⅱ型骨折所占比例远远高于其他骨折分型(P < 0.01);其余各组间分型比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

2.3.2. 鼻骨骨折及其合并周围骨折情况

相对于单纯性鼻骨骨折而言,鼻骨合并上颌骨额突骨折更为多见,共1 445例(50.16%);单纯性鼻骨骨折1 027例(35.65%);鼻眶筛复合体骨折341例(11.84%);鼻骨合并颌面部其他类型骨折68例(2.36%)。

2 881例鼻骨骨折患者中,单侧骨折759例(26.35%),其中左侧406例,右侧353例;双侧骨折2 122例(73.65%)。对鼻骨骨折侧别与合并周围骨折情况之间进行χ2检验,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01),其中,单侧骨折多见于单纯性鼻骨骨折,双侧骨折多见于鼻骨合并上颌骨额突骨折(表 2)。

表 2.

鼻骨骨折及合并周围骨折情况 例(%)

| 侧别 | 单纯性鼻骨骨折 | 合并上颌骨额突骨折 | 鼻眶筛骨折 | 合并颌面部其他骨折 | 合计 |

| 左侧 | 186(6.46) | 172(5.97) | 42(1.46) | 6(0.21) | 406(14.09) |

| 右侧 | 178(6.18) | 153(5.31) | 17(0.59) | 5(0.17) | 353(12.25) |

| 双侧 | 663(23.01) | 1120(38.88) | 282(9.79) | 57(1.98) | 2122(73.65) |

| 合计 | 1027(35.65) | 1445(50.16) | 341(11.84) | 68(2.36) | 2881(100.00) |

2.3.3. 单纯性鼻骨骨折多因素风险分析

对单纯性鼻骨骨折进行Logistic多因素回归分析(表 3),结果发现,性别与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生具有相关性,男性发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较低(OR=0.807,P < 0.05)。年龄亦与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生相关,随着年龄的增长,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的风险降低(OR=0.978,P < 0.01)。部分病因类型亦与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生相关,病因为暴力伤、运动伤、撞伤时,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较高(OR=1.244、P < 0.05,OR=1.410、P < 0.05,OR=1.453、P < 0.05),其余病因与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生无关(P>0.05),以上结果在调整P值前后均未发生改变。

表 3.

单纯性鼻骨骨折多因素风险分析

| 因素 | 单纯性鼻骨骨折 | 调整前P值 | OR值 | 95%CI | 调整后P值 | |

| 是(n=1 027) | 否(n=1 854) | |||||

| 性别 | ||||||

| 男 | 701(68.26) | 1342(72.38) | 0.020 | 0.807 | 0.681~0.955 | 0.013 |

| 女 | 326(31.74) | 512(27.62) | — | — | — | — |

| 年龄/岁 | 27.54±11.83 | 31.03±13.65 | < 0.001 | 0.978 | 0.972~0.985 | < 0.001 |

| 病因 | ||||||

| 车祸伤 | 320(31.2) | 655(35.3) | — | 1.000 | — | — |

| 暴力伤 | 264(25.7) | 431(23.2) | 0.029 | 1.244 | 1.103~1.527 | 0.037 |

| 摔伤 | 148(14.4) | 300(16.2) | 0.936 | 0.949 | 0.746~1.208 | 0.671 |

| 运动伤 | 92(9.0) | 127(6.9) | 0.010 | 1.410 | 1.042~1.909 | 0.026 |

| 工伤 | 33(3.2) | 100(5.4) | 0.064 | 0.715 | 0.470~1.087 | 0.117 |

| 撞伤 | 142(13.8) | 190(10.2) | 0.001 | 1.453 | 1.123~1.881 | 0.005 |

| 其他 | 28(2.7) | 51(2.8) | 0.634 | 1.078 | 0.664~1.749 | 0.762 |

3. 讨论

鼻骨骨折的流行病学调查从患病人群的角度出发研究其发生、分布,并通过对多种危险因素的分析,探讨其相关流行病学特点,从而有助于预防鼻骨骨折和评估鼻骨骨折的发生和预后。有研究指出,鼻骨骨折是颌面部骨折中最常见的骨折类型〔2, 11-12〕。较高的发生率预示着进行相关流行病学调查研究的重要性。目前我国对于鼻骨骨折的研究多侧重于诊断及治疗,相关流行病学研究甚少,其流行病学数据亦有待完善。

本研究表明,男女性别比为2.44:1,与相关研究基本一致〔2, 4, 13-14〕。男性较女性活动频繁,发生鼻骨骨折的概率明显高于女性。19~29岁组为好发年龄段,主要由于此组人群年富力强,频繁暴露于各种危险因素中,因而是鼻骨骨折的好发群体。

研究流行病学的一个重要内容就是分析疾病的原因,以便制定预防策略。在一些发达国家,暴力是构成鼻骨骨折的主要原因之一〔15-16〕,而在中国及一些发展中国家包括部分发达国家,仍然以交通事故伤为主〔17-18〕,这可能与不同国家、地区的经济和文化状况有关。此次调查分析发现,交通事故伤患者最多,其次是暴力打击伤,因此加强交通法规教育、提高公民素养等,是预防鼻骨骨折的有效措施。

在所有鼻骨骨折相关患者中,鼻骨骨折合并上颌骨额突骨折患者多于单纯性鼻骨骨折。这种现象可以解释,考虑到鼻颌缝为鼻骨外缘全长与上颌骨额突内侧缘之间的骨缝连接,而骨缝区为骨质薄弱区,在外力的作用下则极易发生分离、错位,因此鼻骨合并上颌骨额突骨折患者多于单纯性鼻骨骨折患者。此外,由于鼻骨突出于面部中央,外力作用下极易造成鼻骨水平方向上的离断,其骨折线大部分和鼻骨的纵轴垂直,因而考虑此为双侧鼻骨骨折患者远多于单侧鼻骨骨折的原因。

Hwang等〔13〕根据骨折的侧别、形态和骨质移位情况以及是否伴发鼻中隔骨折等将鼻骨骨折分为6型。Han等〔19〕在鼻骨骨折CT轴位图像的基础上自鼻尖至鼻基底部将其分为上、中、下3个水平,以此为基础并根据骨折层次、形态、方向及并发骨折等情况继而分出若干亚型。Murray等〔20〕在对50例尸头相关解剖的基础上将鼻骨骨折分为7型。因上述分型临床实用性欠佳或无法对应临床上实际发生的鼻骨骨折,因此本研究采用Fred分型〔10〕。统计分析发现,Ⅱ型鼻骨骨折患者数目居于首位,这对于鼻骨骨折的临床诊疗有一定的指导意义。

本研究表明,性别与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生具有相关性,男性发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较低,女性更容易发生单纯性鼻骨骨折。而男性患者更容易发生鼻骨合并上颌骨额突骨折、鼻眶筛复合体骨折及其他类型骨折,考虑男性相对女性更频繁暴露于各种危险因素中,骨折程度相对严重。年龄亦与单纯性鼻骨骨折的发生具有相关性。年龄越大,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度越低,更容易合并上颌骨等其他骨折。因为随着年龄的增长,上颌窦腔发育成熟,更为前凸,发生骨折的概率增大〔21〕。相对病因为车祸伤而言,暴力打击伤、运动伤、撞伤时,发生单纯性鼻骨骨折的相对危险度较高。这是由于发生交通事故时,患者更容易受到突发性的猛烈撞击,极易发生颌面骨的多发骨折,且骨折程度相对严重。有研究表明,口腔颌面部多发性的骨折主要原因为交通事故伤,暴力打击伤导致的口腔颌面部骨折往往多为单处骨折〔22〕。

本研究也存在一定的局限性。首先,材料的收集对象主要来自于我院鼻骨骨折的住院患者,并未将门诊患者纳入统计范围;其次,年份跨度相对较大,可能在一定程度上产生统计学误差。

综上所述,鼻骨骨折住院患者在个体特征、创伤原因、损伤部位、程度等方面具有一定的分布规律。对其相关的流行病学研究应予以足够的重视,以便进一步总结和分析,为鼻骨骨折的相关预防和诊疗提供科学的依据。

Funding Statement

促进市级医院临床技能与临床创新能力三年行动计划(No:16CR3051A)

References

- 1.James JG, Izam AS, Nabil S, et al. Closed and Open Reduction of Nasal Fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31(1):e22–e26. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu H, Jeon M, Kim Y, et al. Epidemiology of violence in pediatric and adolescent nasal fracture compared with adult nasal fracture: An 8 years study. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20(4):228–232. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das TA, AslamAS, Mangalath U, et al. Evaluation of Treatment outcome Following Closed Reduction of Nasal bone fractures. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19(10):1174–1180. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim KS, Lee HG, Shin JH, et al. Trend analysis of nasal bone fracture. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2018;19(4):270–274. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold MA, Yanik SC, Suryadevara AC. Septal fractures predict poor outcomes after closed nasal reduction: Retrospective review and survey. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(8):1784–1790. doi: 10.1002/lary.27781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JJ, Hong SD, Dhong HJ, et al. Risk factors for intraoperative saddle nose deformity in septoplasty patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(7):1981–1986. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basheeth N, Donnelly M, David S, et al. Acute nasal fracture management: A prospective study and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(12):2677–2684. doi: 10.1002/lary.25358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byun IH, Lee WJ, Roh TS, et al. Demographic Factors of Nasal Bone Fractures and Social Reflection. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31(1):169–171. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Jeon M, Kim Y, et al. Epidemiology of violence in pediatric and adolescent nasal fracture compared with adult nasal fracture: An 8-year study. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20(4):228–232. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2019.00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fred GF, Michael PO, Todd WP, et al. Management of nasal trauma to the nasal bones and septum[M]//Fred JS, Chris DS, Guy SK, eds. Rhinology and Facial Plastic Surgery. Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2009: 793-799.

- 11.Kuhr E, Werner JA, Dietz A, et al. Analysis of the emergency patients of a university ENT hospital. Laryngorhinootologie. 2019;98(9):625–630. doi: 10.1055/a-0916-8916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li K, Moubayed SP, Spataro E, et al. Risk Factors for Corrective Septorhinoplasty Associated With Initial Treatment of Isolated Nasal Fracture. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(6):460–467. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang K, You SH, Kim SG, et al. Analysis of nasal bone fractures: a six-year study of 503 patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17(2):261–264. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200603000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham TT, Lester E, Grigorian A, et al. National Analysis of Risk Factors for Nasal Fractures and Associated Injuries in Trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019;12(3):221–227. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KH, Qiu M. Characteristics of Alcohol-Related Facial Fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(4):786.e1–786.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emodi O, Wolff A, Srouji H, et al. Trend and Demographic Characteristics of Maxillofacial Fractures in Level I Trauma Center. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(2):471–475. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang BH, Kang HS, Han JJ, et al. A retrospective clinical investigation for the effectiveness of closed reduction on nasal bone fracture. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;41(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s40902-019-0236-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menon S, Sham ME, Kumar V, et al. Maxillofacial Fracture Patterns in Road Traffic Accidents. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2019;9(2):345–348. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_136_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han DS, Han YS, Park JH, et al. A new approach to the treatment of nasal bone fracture: radiologic classification of nasal bone fractures and its clinical application. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(11):2841–2847. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray JA, Maran AG, Busuttil A, et al. A pathological classification of nasal fractures. Injury. 1986;17(5):338–344. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(86)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boffano P, Roccia F, Zavattero E, et al. European Maxillofacial Trauma(EURMAT)in children: a multicenter and prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(5):499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham TT, Lester E, Grigorian A, et al. National Analysis of Risk Factors for Nasal Fractures and Associated Injuries in Trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2019;12(3):221–227. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1677724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]