ABSTRACT

Coccidioides immitis, a pathogenic environmental fungus that causes Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) primarily in the American Southwest and parts of Central and South America, has emerged over the past 12 years in the Columbia River Basin region, near the confluence with the Yakima River, in southcentral Washington state, USA. An initial autochthonous Washington human case was found in 2010, stemming from a wound derived from soil contamination during an all-terrain vehicle crash. Subsequent analysis identified multiple positive soil samples from the park where the crash occurred (near the Columbia River in Kennewick, WA), and from another riverside location several kilometers upstream from the park location. Intensified disease surveillance identified several more cases of coccidioidomycosis in the region that lacked any relevant travel history to known endemic locales. Genomic analysis of both patient and soil isolates from the Washington cases determined that all samples from the region are phylogenetically closely related. Given the genomic and the epidemiological link between case and environment, C. immitis was declared to be a newly endemic fungus in the region, spawning many questions as to the scope of its presence, the causes of its recent emergence, and what it predicts about the changing landscape of this disease. Here, we review this discovery through a paleo-epidemiological lens in the context of what is known about C. immitis biology and pathogenesis and propose a novel hypothesis for the cause of the emergence in southcentral Washington. We also try to place it in the context of our evolving understanding of this regionally specific pathogenic fungus.

KEYWORDS: Coccidioides, genomics, paleo-epidemiology

COCCIDIOIDES BACKGROUND

Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii are the two known genetically and geographically distinct species of the dimorphic Coccidioides fungus, primarily found in the deserts of the American Southwest (1). Coccidioides has been considered a soil saprophyte that can articulate athroconidial spores that, once released into the air following soil disturbance, can infect a large diversity of mammals, including rodents, canids, and primates (both human and nonhuman) (2).

More recently, the Coccidioides parasite theory has been gaining traction, with genomic and biologic evidence suggesting that this fungus has evolved to feed on animal proteins (from carcasses) while in the saprophytic phase (3, 4). Comparative genomic analysis has demonstrated that Coccidioides has lost genes for plant protein breakdown and has acquired animal proteinases, including those to break down keratin (5). Additionally, Coccidioides has been associated with rodent and other mammal burrows under several studies leading to the small mammal endozoan hypothesis (3, 4); wherein Coccidioides infects small mammals and is maintained in an inactive spherule state in lung granulomas, which subsequently transform into spore-producing hyphae when the rodent or small mammal dies (from either disseminated disease or some other cause) (3). Lowered temperatures after death of the mammalian host allow the fungus to revert to the hyphal phase, and to grow and expand in the carcass. This endozoan hypothesis still posits a soil-based existence and is primarily limited to soils near burrows, middens, and buried infected carcasses, which have high organic material loads to support continued hyphal growth.

Coccidioides is only found in the Western Hemisphere, with the major region of endemicity in the desert Southwest of North America and locally hot arid regions in Central and South America (2). C. immitis is largely found in central California (CA) and occurs sporadically in southern CA and northwestern Mexico. C. posadasii is more hemispherically distributed: it is predominantly found in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona and northern Mexico, but is also endemic in southern Utah, New Mexico, Texas, northeastern Mexico, Guatemala, and several countries in South America (including Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela) (2).

THE WASHINGTON STATE COCCIDIOIDES EMERGENCE: THE PROBLEM

Coccidioides is an environmental fungus that is primarily localized to the North American desert Southwest and has not previously been documented in soils outside its hot and arid endemic zones. In 2010, an autochthonous case was reported in southcentral Washington (SC-WA); this apparent expansion in range has been suggested to be connected to global and regional climatic changes that would allow for increased environmental distribution and survival in a warming landscape. Whether a link to climate change is correct or not, it does not answer the “origin” question: from where, when, and how did the region become an endemic source of Coccidioides?

HYPOTHESIS

We hypothesize that recently identified SC-WA Coccidioides cases are derived from local soil that had been contaminated by burial of an early/ancient diseased human or canine that was originally infected in the San Joaquin Valley region of CA and migrated or returned north to the Columbia River basin region, likely thousands of years ago.

AN INTERDISCIPLINARY ASSESSMENT

Rather than assessing from a single perspective (e.g., climate change), it is critical to instead examine the hypothesis from an interdisciplinary view to identify the possible weaknesses that can and should be explored. As our hypothesis describes the possibility of a single emergence-driving event thousands of years ago, it is not readily empirically testable and, therefore, should be assessed based on the confluence of biological, geographic, climatic, and archaeological lines of evidence, including, our understanding of the epidemiology of the pathogen and its disease, the ancient natural history of hosts, the paleo-climatic and geologic history of the locale, and the use of genomic data to infer the evolutionary history of this unique population of Coccidioides.

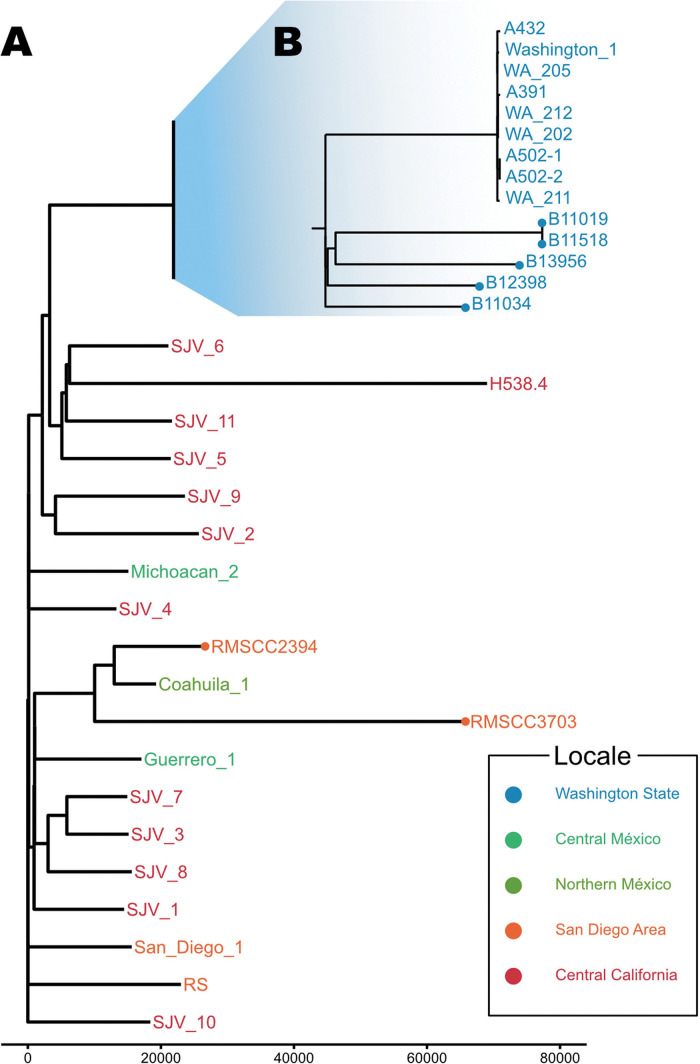

Genomic evidence. The 12 published genomes from the SC-WA Coccidioides case and soil isolates make up a distinct phylogenetic clade of C. immitis (6). This SC-WA clade of Coccidioides is highly clonal compared to the larger population structure of C. immitis (6–9) (Fig. 1). Only one mating type has been found among the WA genomes (8) (a likely reason for the limited population diversity observed), which can also be an indicator of limited or single introduction of a common ancestor in the region. This clade does, however, contain hundreds of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), suggesting sustained local replication, evolution, and diversification. Using the coarse 10−9 substitutions/year estimate previously published for Coccidioides and an ~29 Mb genome (8), the published 234 to 324 SNP mutation distance between individual genomes in the SC-WA region (6) could be grossly estimated to represent about 7 to 10K years of evolution. Although not suspected here, if we assume the much faster mutation rate of 10−8 substitutions/year rate, as has been seen in recombining fungal populations, the calculation yields a most recent common ancestor at 700 to 1,000 years ago. Additional, more refined, molecular clock estimations (e.g., employing Bayesian evolutionary inference tools) will add better confidence to age of this population. In either situation, however, these calculations establish a Pre-Columbian time frame for introduction to the region.

FIG 1.

Maximum parsimony whole genome phylogenies of (A) Coccidioides immitis and (B) C. immitis strains from South Central WA. SNP distances are represented on numbered line. Adapted from Oltean et al. 2019 (6) and Monroy-Nieto et al. 2023 (9).

As a whole, C. immitis is an old species, likely separating from C. posadasii at least five million years ago (mya) (5), and further diversifying approximately one mya in what is now the San Joaquin Valley (SJV) in central CA (8), a large former inlet of the Pacific Ocean that currently houses one of the most productive agricultural lands in the world. The SJV is the major endemic source of C. immitis and provides the disease’s colloquial namesake “Valley fever.” The SC-WA genomic clade fits within a larger SJV-CA population of Coccidioides, suggesting a possible originating locale (6) (Fig. 1). While population studies of C. immitis are still limited, it is surmised that the SJV-CA population is the oldest and most diverse phylogeographic group of C. immitis, consisting of a number of local subpopulations and other endemic locales that have distinctly diverged local phylogeographic clades (e.g., southwest CA and Baja Mexico) (8). The population structure, therefore, signals both temporal and geographic origins of the SC-WA clade.

Alternate interpretations of direction and timing of spread. As the hypothesis proposes not only a mechanism (infected host burial) but also proposes directionality (CA to WA) and timing (several thousand years ago), it is important to consider the possibility of the contra-hypotheses: (i) not CA to WA, and (ii) not ancient. We briefly consider those now.

(i) Directionality. We identify three possibilities of dispersal direction of C. immitis associated with WA: (i) SJV-CA to SC-WA, (ii) SC-WA to SJV-CA, and (iii) a third locale dispersing to both SJV-CA and SC-WA. The primary evidence for Possibility 1 is the phylogenomic data that establishes the SC-WA population as a single clone that is distal, rather than basal, in the C. immitis phylogeny, which would negate possibility 2 (WA to CA) but not possibility 3 (third locale). Possibility 3 is not completely discordant with the phylogenomic data, as a separate originating source could have fed both the CA and WA locales independently. However, the SJV-CA populations are clearly more diverse and older than any other known C. immitis populations, and possibility 3 would require an even older and likely more diverse C. immitis population that is either undiscovered or is now extinct. Given the proliferation of genome sequencing on strains that have been recovered in most locales where coccidioidomycosis has been found, it is unlikely that there is a surviving diverse progenitor C. immitis population; however, the possibility for an extinct founding population that sourced both SJV-CA and SC-WA independently cannot be ruled out on genetic evidence alone. In that case, such a progenitor would have to: (i) have become extinct following dispersal to SC-WA, and (ii) would have had to disperse to SJV-CA and SC-WA at dramatically different time points and to nowhere else that has been detected to date (otherwise such a tertiary dispersed population would show as a basal in the C. immitis phylogeny).

(ii) Timing. As with directionality, there are also three possibilities for the timing of dispersal: (i) the SC-WA population is younger than the SJV-CA population, (ii) the SC-WA is older than the SJV-CA population, and (iii) the SC-WA and SJV-CA are the same age. We argue for the likelihood of possibility 1, given that genomic analysis of SC-WA indicates that the limited diversity results from a shorter evolutionary history. Possibilities 2 and 3 could only be possible if the SC-WA population has been in a suspended state of evolution, which could occur if isolates inhabited frozen environments. This concept is not without precedent: We have previously proposed that following the speciation event that separated C. immitis from C. posadasii, the former may have been held in glacial refugia in the Sierra Nevada glaciers prior to drainage of the central basin of California ~700 kya, which could account for millions of years of timing separation between observed initial diversification events in each species (8). This hypothetical mechanism has not been proven and requires further analysis; however, at this point, the most parsimonious answer is that the SC-WA population is evolutionarily newer than the SJV-CA population.

Given the several possibilities for the origin of the SC-WA isolates with regard to directionality and timing, we now further explore biogeographic, host/vector, and soil-contamination lines of evidence to identify the most likely originating scenarios.

Biogeographic evidence. Currently, the only known endemic soils for C. immitis in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) region are the soils that have been found in the Tri-Counties region of SC-WA over the past decade. The first two human cases were linked to contaminated soils found along the Columbia River at the site of an accident at an ATV park, and to positive soil sites upstream near the Yakima River confluence (aka “the Delta”) with the Columbia River (7, 10). Multiple other cases with known exposure to the region have been since identified, and all genomes sequenced from local cases and soil isolates belong to a single SC-WA clade (6). Numerous other PNW coccidioidomycosis cases in WA and neighboring OR have been identified during this time period, but none have been linked to local contaminated soils, and most had travel history to known regions of endemicity during their likely exposure period (6, 9). One possible exception is a case in Spokane, WA (~210 km northeast of the endemic locale), which reported travel exposure to the SC-WA region >8 years prior to onset of disease (11).

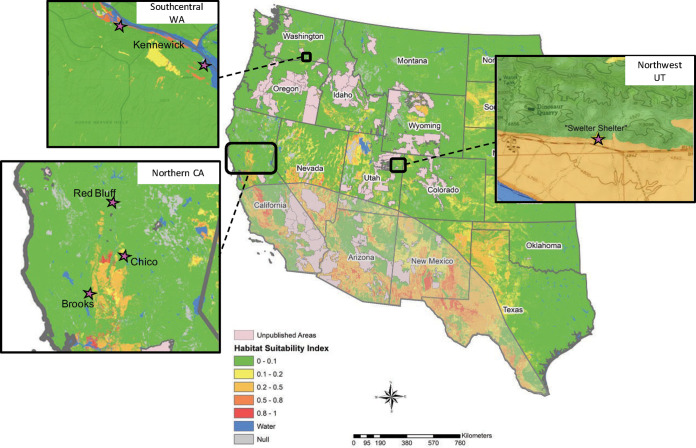

Endemic Coccidioides locales are typically limited to dryer, thermic soils in the Western Hemisphere, and notably include the SJV and the Sonoran Desert, where most human cases occur. Other endemic locales in the Southwestern US, Mexico, Central America, and South America are also all associated with arid locations with thermic soils (12). The SC-WA Tri-Cities region is a warmer, drier environment than much of the surrounding region and therefore appears to be a suitable habitat niche for the fungus (13, 14). A recent high-resolution habitat niche modeling study based on multiple soil and climate parameters (15) determined that the SC-WA locale was highly suitable for Coccidioides. This included nearby areas immediately adjacent to the Yakima River, which feeds into the Columbia River (Fig. 2), as well as limited locales in nearby northcentral Oregon (OR); although there is no current evidence of Coccidioides existing naturally in OR soils. The same study found that most of the surrounding area in WA and OR is considered unsuitable habitat (15).

FIG 2.

Coccidioides spp. soil habitat suitability in United States, including outbreak locations outside the classic endemic zone. Stars represent locales of archeological outbreak sites in California (CA) and Utah (UT), and locales of positive soils in southcentral Washington (WA). Lightly shaded area represents classic endemic zone. Adapted from Dobos et al. 2021 (15).

Animal infection evidence. As the connection to mammals is a critical part of the Coccidioides life cycle and, as proposed here and elsewhere, to the distribution of Coccidioides into previously nonregions of endemicity (8, 16), one should consider the likelihood of the emergence in SC-WA being tied to an infected human or animal being buried or deposited in the soils. Local mammalian wildlife and positive soil samples have been identified at nearly all established endemic locales, which provides evidence of natural circulation (17).

Coccidioides is typically found in soil near small mammal burrows, and its parasitic life cycle has long been tied to mammal infection (3, 4, 18, 19). Genomic studies have provided significant evidence of the critical nature of animal infection for Coccidioides metabolism and survival, especially with genomic identification of decreases in plant proteinases and increases in animal proteinases (5). Previous studies have also established that Coccidioides presence in the soil tends to remain very focal, with nearby soil (<10 m away) often remaining uninfected (20); this finding would not be seen if distribution was either random or more ubiquitous in regions of endemicity, as would occur with a pure soil saprophyte. A previous study demonstrated that uncontaminated soil in the area of endemicity of C. immitis, which had failed to produce cultures of the fungus for 3 years prior to the experiment, became Coccidioides-positive 5 months after the burial of experimentally infected mice; this soil remained positive for each of the subsequent 6 years (21). Consequently, there is continued and growing support for the hypothesis that contaminated soils originate from an infected animal corpse (4) which, if the soil and niche conditions are suitable, results in long-term or permanent colonization of nearby soils (22). Both animal burrows and surrounding soils have been found positive in the SC-WA locale, although more study is needed to understand the extent of the burrow-surrounding soil relationship in the region (22).

Evidence for single-introduction event. It is reasonable that distinct phylogeographic populations result from discrete microbial dispersal events (e.g., specific one-time migration of, and subsequent site contamination by, infected animals; or significant landscape-changing events such as natural disasters) versus ongoing mechanisms of continually repeated events (e.g., seasonal animal migrations; or wind dispersal); otherwise, phylogenetic populations would lack geographical distinction (8). Based on its discrete phylogeographic population structure, Coccidioides likely dispersed to new endemic zones in Central and South America by the movement of infected mammals that subsequently died and decayed in the soil. In this regard, the timing of the dispersal from southwestern North America to South America coincided with the later Great American Biotic Interchange movements between continents more than 700 thousand years ago (kya) (8, 16), well before human presence in the hemisphere. Similarly, the clonal C. immitis population in SC-WA is likely to represent a single introduction event since multiple introductions from a presumable SJV-CA source locale would have resulted in a polyphyletic distribution with a common ancestor shared between isolates originating elsewhere. A similar effect could have been responsible for the recently investigated clonal Venezuelan C. posadasii population (23), which may also have been the result of an introduction of a single C. posadasii infected animal to the locally restricted region of endemicity.

Evidence for soil contamination through human and companion animal burial. Beyond infected wildlife and before the modern era of burial practices that would prevent soil contamination from infecting fungi, humans and their canine companions also likely made for suitable vectors to translocate fungus to new regions. Coccidioides has been found in multiple archeological sites where human and animal (canine) bodies have been buried; a famous nonendemic Coccidioides hot spot (i.e., highly localized soil presence and documented human cases) is the Swelter Shelter archeological dig site at Dinosaur National Monument in northern UT (12) (Fig. 2). The immediate region has been identified as a moderately suitable habitat niche (15), and although this locale in northern UT is well outside the standard endemic zone, it is frequently included in region of endemicity maps due to documented outbreaks occurring at the Swelter Shelter site. Archeologist outbreaks in both 1964 and 2001 (24–26) were directly linked to exposure to a single highly contaminated Swelter Shelter midden that was subsequently shown to be Coccidioides PCR-positive (27). These outbreaks had extremely high attack rates (>90% of susceptible individuals were infected) (26) owing to the highly localized and intense nature of exposure to the contaminated site. This conclusion is further supported by a lack of positive case finding or serologic evidence of exposure in longtime workers at Dinosaur National Monument who did not have direct exposure to the Swelter Shelter site (26).

Previous studies have identified bone lesions consistent with Coccidioides in human skeletal remains from pre-Columbian burial sites in highly endemic Arizona regions (28, 29). However, given the lack of any known human grave at Swelter Shelter, it is possible that the Swelter Shelter Coccidioides contamination is from the burial of pre-Columbian companion canines, which could have been infected with Coccidioides elsewhere and subsequently died and buried in the midden, where the fungus was able to survive and thrive within the protected site. Buried animal skeletal remains at Swelter Shelter were found in the deepest, oldest layer in the midden, dating back to nearly nine thousand years ago (24).

Similar coccidioidomycosis outbreaks have been described at other archeological sites in the Western US, including multiple locales outside classic Coccidioides areas of endemicity (Fig. 2). A 1968 coccidioidomycosis outbreak occurred in archeologists at a dig site in Brooks, CA (40 miles north of San Francisco), well outside the classic endemic zone (30). Additionally, a large 1970 outbreak involved 61 archeological students at a dig site with human remains and middens near Chico, CA (100 miles north of Sacramento) (31). In 1973, an outbreak of 17 archeology students occurred at a site of ancient Yana people in Red Bluff, CA (20 miles north of Chico, CA) (32) (Fig. 2). Each of these instances had high attack rates (59%, 44%, and 48%, respectively), providing more evidence that archeological sites in the American West are at high risk for being heavily contaminated Coccidioides locales, even if outside the region of endemicity. Perhaps less significantly, a fossilized ancient Bison antiquus jaw bone, recovered in Nebraska and dating to ~8,500 years ago, was thought to contain lesions that were indicative of possible Coccidioides spherules (33). Subsequent ancient DNA analyses of bone material collected from the lesion did not detect coccidioidal DNA but did successfully amplify bison DNA (D.M. Engelthaler et al., unpublished data), leaving a hypothetical ancient Coccidioides presence in Nebraska as still unsupported.

A human or canine burial site connection to the southcentral WA locale? The region of the SC-WA Coccidioides population centers around Kennewick, WA (Fig. 2)—the location of the discovery of “Kennewick Man,” or “The Ancient One”—from approximately 9,000 years ago (34–36). This coincidence is interesting because he was either purposely buried at the site or covered by flood sediment soon after death, making him the earliest known interment in the region. This is not to suggest that The Ancient One was tied to the local Coccidioides population in the region; rather, we mention Kennewick Man because he demonstrates the occurrence of ancient burials in the area, which supports the notion of local soil contamination via burial. In fact, human bodies were historically buried throughout the southern Columbia Basin, with some of the earliest recovered from cave and rockshelter sites in deposits almost as old as Kennewick Man (37). Earlier interments (5,000 to 9,000 years ago) have been identified at Marmes Rockshelter, ~100km northeast of Kennewick, while a grave was identified at Cedar Cave, on the Columbia River above Kennewick, dating to approximately 2,500 years ago. Open air interments were common on the Columbia River dating from at least 3,000 years ago (37), including islands at the nearby mouth of the Yakima (37) and those at the Wahluke Site, located further upstream of the Yakima River (38). Interestingly, one human skeleton, uncovered in the 1987 Hanford site (along the Columbia River), dating to 1800 years before present, had bone lesions that were originally thought to be associated with Brucella, but are also consistent with a possible Coccidioides myelitis (39).

Dog burial was practiced by people living a short distance downstream from the SC-WA area of endemicity as early as 2,500 years ago (40). In addition, small canids, probably dogs, were a common food element along the Columbia River and are incorporated into archaeological middens dating between about 9,000 to 5,000 years ago (41, 42). It is clear that humans and other animals have been buried in the region and that such burials can result in soil contamination, possibly with pathogenic organisms not endemic to the region.

Ancient and modern climate change. The climate conditions in western North America were significantly different >4,000 years ago than they are today. The region north of the Columbia Basin was glaciated episodically during the Pleistocene Epoch, which had its most recent glacial maximum >19 kya. Subsequent warming (interrupted briefly by glacial readvance known as the Younger Dryas) resulted in the elimination of large glaciers in the region by less than 12 kya. Although offset by colder winters, rapid warming continued, raising regional summer temperatures to levels more than 1.2°C above the modern average by ~9,500 to 9,000 years ago (43). The period between 9,500 and 6,400 years ago was the most arid for the Columbia Basin, with hotter summers (reaching ~1.8°C% above the modern summer average temperature of 27.3°C) paired with warmer winters. Vegetation patterns also indicate lower regional precipitation (~14cm) in the arid Kennewick area during this time point (modern Kennewick area annual precipitation is ~19.5 cm). These conditions may have promoted initial Coccidioides survival and growth in the immediate area of where an infected body may have been buried (36). In fact, the increase in warming and aridity is likely to have had the effect of expanding the suitable habitat of Coccidioides in the Columbia Basin beyond its current known range, which occurred during a time when people were interring their dead in primary graves. Climate became gradually moister and cooler after 6,400 years ago, with readvances of montane glaciers occurring episodically after 5,000 years ago. This cooling increased between 4500 and 4000 years ago and included two widespread episodes of markedly cooler, moister conditions. The first, known as the Neoglacial, lasted from ~4,000 to 2,800 years ago, while the last, known as the Little Ice Age, persisted from 400 years ago until the late 19th century. While ancient climate change may have provided the conditions for Coccidioides to initially survive and thrive in the soils in the region ahead of the significant cooling of the “mini-ice ages,” warming since this glacial period may have provided an impetus for continued soil growth, Coccidioides cycling in small mammal populations, and subsequent local transmission.

Translocation to the Pacific Northwest. This then begs the question of how likely was it that a local resident (human or canid), thousands of years before regular long-distance travel, could have been infected with Coccidioides in central California and traveled hundreds of kilometers north to eventually die, be buried, and contaminate soils with a nonendemic fungus. We obviously do not have records of such travels, but we can look to seashells for a clue. We know Olivella shell beads from the nearby Fort Rock Basin of central Oregon, dating to the middle and late Holocene (<9,000 years ago), came from the lower Pacific coasts (44) and that trade in that comodity existed at the same time in eastern WA (45). Olivella beads were found associated with most of the early human burials at the nearby Marmes Rockshelter, including two from a stratum dating >7,500 years (46). Further, it is well documented that there were encounters and trade between peoples from central CA valley and coastal CA for most of the last 10K years (47); ancient trade routes throughout North America allow for transcontinental travel of material passing through the hands of traders that individually travel shorter distances. Beyond trade routes, the Columbia River salmon runs were a great annual draw for outside populations, which led to ephemeral seasonal migration to the region (48); and climatic conditions for massive salmon runs have persisted for the last 4,000 years (49). Additionally, it is possible that other long-distance travel for resettlements, nomadic lifestyles, or ritual quests occurred that are not otherwise documented in historical record over the millennia.

We know that domesticated canids (Canis familiaris)—which are highly susceptible to Coccidioides infections—are frequently found in ancient burial sites and middens in the region, which stands to reason, given the close historical relationship between humans and dogs, as pets, protection and providers of fur and food (50). Dogs were also valuable trade items (50) and would have certainly been made to travel long distances as they were passed between traders. Wild canids (wolves and coyotes) were also present, and they too travel long distances; current knowledge suggests far-reaching wolf (Canis lupus) territorial hunting grounds (up to tens of thousands of square kilometers) (51) and natal dispersal of over 3000 km (52), with coyotes (Canis latrans) having much smaller territories (140 km2) and dispersal distances (160 km) (53). However, such wild canids are rarely found in burial sites or middens (50), and carcasses of dead wild animals would likely have been scavenged rather than causing significant contamination below the topsoil.

There is also the possibility of other infected mammals having been translocated or migrated from central CA to the Columbia River basin; however, most mammals are not known to be as susceptible to long-term or systemic infections as humans and canines. Although a number of mammal species have been identified as having been infected with Coccidioides (54), aside from wild felids and rodents (which do not have large territories or long-distance dispersal), none are known to have existed in the ancient Columbia River basin. An interesting finding of Coccidioides-positive bats in Brazil (55) and positive bat guano in caves in southern AZ (56) has led to another untested long-distance dispersal hypothesis via bat migration, which could then occur over thousands of kilometers.

In summary, the evidence as presented above is consistent with the hypothesis of ancient Coccidoides dispersal from CA to SC-WA: (i) endemic Coccidioides from SC-WA is genetically distinct from that found in the southern Central Valley of CA, with divergence times as early as 7000 to 10,000 years ago and as late as 700 to 1000 years ago; (ii) human burial was practiced since at least 9000 years ago and dog deposition in middens goes back nearly as long (dog interment was practiced between ~2500 and 1000 years ago); (iii) continental trade routes, in the form of marine shells from the coast of southern CA to SC-WA, is known from as early as the middle Holocene; and (iv) climatic conditions during the mid-Holocene, especially in the period between 9000 and 6000 years ago, were even warmer and drier than at present, providing suitable habitat for Coccidioides.

Climate and other possible hypotheses for translocation of Coccidioides. While postindustrial climate change has been recently invoked as a mechanism for the expansion of Coccidioides into previously nonregions of endemicity (13, 57), as a hypothesis it lacks an introduction event. In this regard, Coccidioides is clearly not instantaneously appearing in regions where the climate has become warmer and/or drier. Most habitat niche modeling primarily focuses on climatic variables and vegetation cover (58, 59), and therefore changes in such variables (e.g., warming climate and floral displacement) lead to predictions of changing endemic zones (13). However, if climate and its effects on soil alter local conditions, it is possible that either an earlier or subsequent soil introduction event—such as a buried infected carcass—may allow for the “emergence” of a new highly focal endemic locale.

Soil biochemical and microbial properties may be equally important. Biochemical properties of Coccidioides-positive soils versus -negative soils have been studied (4, 20, 22), and although differences have been found (e.g., elevated concentrations of boron, calcium, magnesium, sodium, and silicon in soil leachates were documented in WA-positive versus -negative soils) (22), it is thought that Coccidioides may likely survive in most native soils found in the regions of endemicity with local rodent populations (58, 60). It has also been demonstrated that at least some soils in the American Southeast are not suitable for Coccidioides maintenance and growth (22). It is not clear that climate patterns can change the biochemical properties of the soil that would make once inhospitable soil conducive to coccidioidal growth. The lack of a permissive environment may actually be due to the combination of climate, biochemical properties, and the presence of microbial agonists (22, 61); for example, for other soil fungi such as Cryptococcus neoformans and Paracoccidioides spp., soil residence is directly affected by the presence of amoebae (62, 63). While the interaction between Coccidioides spp. and amoebae has not yet been studied, it is possible that microbial factors are also important for its success in contaminating certain locales. Therefore, future modeling of specific microbial habitat niche may need to employ multiple factors, including soil composition, moisture, temperature, and both vegetative and microbiota composition.

A recent such model pinpoints the areas where Coccidioides is known to be endemic—including the specific SC-WA locales where Coccidioides has been detected in the soil—as having moderate to high habitat suitability (15). This has also been found in areas near the northern CA outbreak sites but identifies the Swelter Shelter site in UT as having only moderate habitat suitability (Fig. 2). This is likely because the positive midden sediments at Swelter Shelter are protected and were probably highly contaminated with an infected carcass. The model proposed by Dobos et al. (15) also pinpoints small suitable locales in Nebraska, Idaho, Wyoming, and South Dakota, where locally acquired coccidioidomycosis or positive soils have not yet been identified. It may be that the limiting factor is not soil conditions or climate, but, rather, whether an infected animal, human or otherwise, died in a region that either has highly or at least moderately suitable soil and is also protected from unsuitable climate conditions (e.g., archeological sites or middens) in the American West. As such, any archeological excavation projects conducted in these regions, particularly if the sites suspected to include human or canine remains, should maintain the same coccidioidal prevention precautions as are currently used in known regions of endemicity (26).

An alternate dispersal hypothesis is that Coccidioides is translocated by wind storms and other natural disasters (64). This is typified by the infamous case of distant coccidioidomycosis cases associated with a windstorm natural disaster event: the 1977 “Tempest of Tehachapi” (65). This massive windstorm carried >10 cm of topsoil westward over vast distances and clearly resulted in airborne transport of Coccidioides spores from SJV-CA, resulting in coccidioidomycosis cases as far away as San Francisco and Sacramento (hundreds of kilometers) (65). Additionally, the 1994 Northridge, CA, earthquake caused a significant outbreak over a large distance due to large amounts of soil and spores being aerosolized (66); however, neither of these disaster events is known to have resulted in newly regions of endemicity. That is, airborne coccidioidal fungal spores can travel great distances and end up causing cases in nonregions of endemicity; however, spores that settle onto the top layers of soil are unlikely to result in new local endemic foci. This is probably best evidenced by the fact that we can see distinct Coccidioides population structures between endemic locales that are connected by winds (e.g., Phoenix and Tucson, AZ), whereas windblown translocation would result in indistinguishable heterogeneous populations (8). Interestingly, while dust storms would seem to be an obvious source of Coccidioides exposure (67), air monitoring during a documented massive dust storm (aka “haboob”) in the highly endemic metropolitan Phoenix region did not result in an increase in detectable airborne fungal spores (68), and epidemiological association studies have not identified a clear link between documented dust storms and increased human cases of coccidioidomycosis (69). None of these arguments discount the likely and obvious connection of local epidemiology to climate, which has been explored and modeled for at least 2 decades (14, 59, 70–72). It is generally understood that temperature and rainfall patterns combine to provide suitable soil conditions for fungal mycelial growth, which leads to spores becoming airborne following soil disturbances (aka “grow and blow”) (71). However, this environmentally driven coccidioidomycosis epidemiology does not have a mechanism for habitat dispersal beyond this natural cycling resulting in the infection of a susceptible mammal that can travel long distances and die (and perhaps be buried) elsewhere, with the resulting carcass heavily seeding the soil with a novel microbe.

Context with modern climate change. Currently, nearly all discussions of environmental pathogen dispersal and expanding zones of endemicity seem to be centered on contemporary global warming trends. While climate change may in fact be playing an important role in creating both subtle and overt changes to different ecological zones and microhabitats, we must account for how, when, where, and why microbes, such as fungi, disperse from one region to another. Climate change may then help provide ripe conditions for growth of recent or ancient deposition of environmental microbes. Additionally, if such a microbe is associated with ancient peoples in a region, this may represent a risk factor for future archeological exploration in said region. Climate change, therefore, may not always be a driver of pathogen expansion; however, it may reveal past such events in a deadly fashion.

CONCLUSIONS

Reconstructing events in the distant past is important to understand the epidemiology of infectious diseases today; however, all such explorations are limited by the fragmentary information and the many possibilities that follow. To explain the Coccidioides presence in SC-WA, we have attempted to reconstruct the events leading to the introduction of this fungus to that site by piecing together genomic, anthropological, and climatic evidence with what is known about the biology and pathogenesis of coccidiomycosis from observational and experimental studies. Using Occam’s razor’s dictum that the simplest explanation is more likely to be correct, we propose that the SC-WA soil was contaminated via the travel, death and burial of an ancient human or domesticated animal from the central CA region of endemicity to SC-WA. Recent large-scale analyses of clinical cases have established the occurrence of human coccidiomycosis well outside known regions of endemicity (9, 73) and, while nearly all such occurrences are likely travel-related, it is possible that other locales contaminated with Coccidioides will be identified. Should those sites be found, the application of the same type of analysis as described here may further shed light on the mechanism by which Coccidioides can spread from its ancestral southwestern sites to colonize other regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Juan Monroy-Nieto, Sara Wilbur, Tanner Porter, and Katherine Walter for their careful review and edits. We acknowledge the enormity of research done in the fields of mycology, epidemiology, archeology, anthropology, paleontology, geology, mammalogy, climate sciences, and others that have led to the gathering of rich data that provided direction and context for the exploration of the hypothesis presented here. The authors further acknowledge the early indigenous populations of the Americas, who certainly suffered from this and other endemic mycoses long before the arrival of Europeans in the hemisphere.

Contributor Information

David M. Engelthaler, Email: DEngelthaler@tgen.org.

J. Andrew Alspaugh, Duke University Hospital

REFERENCES

- 1.Whiston E, Taylor JW. 2016. Comparative phylogenomics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic species. G3—Genes Genom Genet 6:235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams SL, Chiller T. 2022. Update on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of coccidioidomycosis. JoF 8:666. doi: 10.3390/jof8070666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor JW, Barker BM. 2019. The endozoan, small-mammal reservoir hypothesis and the life cycle of Coccidioides species. Med Mycol 57:S16–S20. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollath DR, Teixeira MM, Funke A, Miller KJ, Barker BM. 2020. Investigating the role of animal burrows on the ecology and distribution of Coccidioides spp. in Arizona soils. Mycopathologia 185:145–159. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Rounsley SD, Gardner MJ, Wortman JR, Jordar VS, Maiti R, Kodira CD, Neafsey DE, Zeng Q, Hung C-Y, McMahan C, Muszewska A, Grynberg M, Mandel MA, Kellner EM, Barker BM, Galgiani JN, Orbach MJ, Kirkland TN, Cole GT, Henn MR, Birren BW, Taylor JW. 2009. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res 19:1722–1731. doi: 10.1101/gr.087551.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oltean HN, Etienne KA, Roe CC, Gade L, McCotter OZ, Engelthaler DM, Litvintseva AP. 2019. Utility of whole-genome sequencing to ascertain locally acquired cases of coccidioidomycosis, Washington, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 25:501–506. doi: 10.3201/eid2503.181155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litvintseva AP, Marsden-Haug N, Hurst S, Hill H, Gade L, Driebe EM, Ralston C, Roe C, Barker BM, Goldoft M, Keim P, Wohrle R, Thompson GR, Engelthaler DM, Brandt ME, Chiller T. 2015. Valley fever: finding new places for an old disease: coccidioides immitis found in Washington State soil associated with recent human infection. Clin Infect Dis 60:e1–e3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelthaler DM, Roe CC, Hepp CM, Teixeira M, Driebe EM, Schupp JM, Gade L, Waddell V, Komatsu K, Arathoon E, Logemann H, Thompson GR, III, Chiller T, Barker B, Keim P, Litvintseva AP. 2016. Local population structure and patterns of western hemisphere dispersal for Coccidioides spp., the fungal cause of Valley fever. mBio 7:e00550–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00550-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monroy-Nieto J, Gade L, Benedict K, Etienne KA, Litvintseva AP, Bowers JR, Engelthaler DM, Chow NA. 2023. Genomic epidemiology linking nonendemic coccidioidomycosis to travel. Emerg Infect Dis 29:110–117. doi: 10.3201/eid2901.220771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsden-Haug N, Hill H, Litvintseva AP, Engelthaler DM, Driebe EM, Roe CC, Ralston C, Hurst S, Goldoft M, Gade L. 2014. Coccidioides immitis identified in soil outside of its known range—Washington, 2013. MMWR—Morb Mortal W 63:450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oltean HN, Springer M, Bowers JR, Barnes R, Reid G, Valentine M, Engelthaler DM, Toda M, McCotter OZ. 2020. Suspected locally acquired coccidioidomycosis in human, Spokane, Washington, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 26:606–609. doi: 10.3201/eid2603.191536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCotter OZ, Benedict K, Engelthaler DM, Komatsu K, Lucas KD, Mohle-Boetani JC, Oltean H, Vugia D, Chiller TM, Sondermeyer Cooksey GL, Nguyen A, Roe CC, Wheeler C, Sunenshine R. 2019. Update on the epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis in the United States. Med Mycol 57:S30–S40. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorris ME, Treseder KK, Zender CS, Randerson JT. 2019. Expansion of coccidioidomycosis endemic regions in the United States in response to climate change. GeoHealth 3:308–327. doi: 10.1029/2019GH000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver E, Kolivras KN, Thomas RQ, Thomas VA, Abbas KM. 2020. Environmental factors affecting ecological niche of Coccidioides species and spatial dynamics of Valley fever in the United States. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 32:100317. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2019.100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobos RR, Benedict K, Jackson BR, McCotter OZ. 2021. Using soil survey data to model potential Coccidioides soil habitat and inform Valley fever epidemiology. PLoS One 16:e0247263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher FS, Bultman MW, Johnson SM, Pappagianis D, Zaborsky E. 2007. Coccidioides niches and habitat parameters in the southwestern United States: a matter of scale. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1111:47–72. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ocampo-Chavira P, Eaton-Gonzalez R, Riquelme M. 2020. Of mice and fungi: Coccidioides spp. distribution models. JoF 6:320. doi: 10.3390/jof6040320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emmons CW. 1942. Isolation of Coccidioides from soil and rodents. Public Health Rep (1896–1970) 57:109–111. doi: 10.2307/4583988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egeberg RO, Elconin AE, Egeberg MC. 1964. Effect of salinity and temperature on Coccidioides immitis and three antagonistic soil saprophytes. J Bacteriol 88:473–476. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.2.473-476.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacy GH, Swatek FE. 1974. Soil ecology of Coccidioides immitis at Amerindian middens in California. Appl Microbiol 27:379–388. doi: 10.1128/am.27.2.379-388.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddy KT. 1965. Observations on Coccidioides immitis found growing naturally in soil. Ariz Med 22:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chow NA, Kangiser D, Gade L, McCotter OZ, Hurst S, Salamone A, Wohrle R, Clifford W, Kim S, Salah Z, Oltean HN, Plumlee GS, Litvintseva AP. 2021. Factors influencing distribution of Coccidioides immitis in soil, Washington State, 2016. mSphere 6:e0059821. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00598-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira MM, Alvarado P, Roe CC, Thompson GR, Patané JSL, Sahl JW, Keim P, Galgiani JN, Litvintseva AP, Matute DR, Barker BM. 2019. Population structure and genetic diversity among isolates of Coccidioides posadasii in Venezuela and surrounding regions. mBio 10:e01976–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01976-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breternitz DA. 1970. Archaelogical excavations in Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado-Utah, 1964–1965. University of Colorado Press, Boulder, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Coccidioidomycosis in workers at an archeologic site—Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, June–July 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 50:1005–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen LR, Marshall SL, Barton C, Hajjeh RA, Lindsley MD, Warnock DW, Panackal AA, Shaffer JB, Haddad MB, Fisher FS, Dennis DT, Morgan J. 2004. Coccidioidomycosis among workers at an archeological site, northeastern Utah. Emerg Infect Dis 10:637–642. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson SM, Carlson EL, Fisher FS, Pappagianis D. 2014. Demonstration of Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii DNA in soil samples collected from Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. Sabouraudia 52:610–617. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison WR, Merbs CF, Leathers CR. 1991. Evidence of coccidioidomycosis in the skeleton of an ancient Arizona Indian. J Infect Dis 164:436–437. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temple DH. 2006. A possible case of coccidioidomycosis from the Los Muertos site, Tempe, Arizona. Int J Osteoarchaeol 16:316–327. doi: 10.1002/oa.827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loofbourow JC, Pappagianis D, Cooper TY. 1969. Endemic coccidioidomycosis in Northern California. An outbreak in the Capay Valley of Yolo County. Calif Med 111:5–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner SB, Pappagianis D, Heindl I, Mickel A. 1972. An epidemic of coccidioidomycosis among archeology students in northern California. N Engl J Med 286:507–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197203092861003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werner SB, Pappagianis D. 1973. Coccidioidomycosis in Northern California. An outbreak among archeology students near Red Bluff. Calif Med 119:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrow W. 2006. Holocene coccidioidomycosis: valley fever in early Holocene bison (Bison antiquus). Mycologia 98:669–677. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakeley LD, Murphy WL, Dunbar J, Warne AG, Briuer FL, Nickens PR. 1998. Geologic, geoarchaeologic, and historical investigation of the discovery site of ancient remains in Columbia Park, Kennewick, Washington, vol Technical Report GL-98–13. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chatters JC. 2000. The recovery and first analysis of an early Holocene human skeleton from Kennewick, Washington. Am Antiq 65:291–316. doi: 10.2307/2694060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owsley D, Williams A, Stafford T. 2014. Taphonomic indicators of burial context, p 323–381. In Owsley D, Jantz R (ed), Kennewick Man: the scientific investigation of an ancient American skeleton. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sprague R. 1967. Aboriginal burial practices in the plateau region of North America. PhD dissertation. University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krieger HW. 1927. Archaeological investigations in the Columbia River Valley, p 187–200, Explorations and field-work of the Smithsonian Institution in 1926, vol 78. Smithsonian, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatters JC, Pasternak CR. 1992. A possible case of prehistoric brucellosis from northwestern America. Am J Phys Anthropol Supplement 21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dumond DE, Minor R. 1983. Archaeology of the John Day Reservoir: the Wildcat Canyon Site 35-GM-9, Athropological Papers No 30. University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chatters JC. 1986. The Wells Reservoir Archaeological Project, Volume 1: summary of findings. Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chatters JC. 2003. Archaeological investigations at Okanogan phase sites 45D0373 and 45OK420, Okanogan and Douglas Counties, Washington. Applied Paleoscience, Bothell, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chatters JC Jr. 1998. Environment, p 26–48. In Walker D (ed), Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 12, Plateau. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith GM, Cherkinsky A, Hadden C, Ollivier AP. 2016. The age and origin of Olivella beads from Oregon's LSP-1 rockshelter: the oldest marine shell beads in the northern Great Basin. Am Antiquity 81:550–561. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galm J. 1994. Prehistoric trade and exchange in the interior plateau of northwest North America, p 275–305. In Baugh T, Erickson J (ed), Prehistoric exchange systems in North America. Plenum, New York City, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rice D. 1968. Preliminary report: Marmes rockshelter archaeological site, southern plateau. Washington State University, Pullman, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennyhoff JA, Hughes RE. 1987. Shell bead and ornament exchange networks between California and the western Great Basin. Anthr Papers 64:268–270. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern T Jr. 1998. Columbia River trade network, p 941–943. In Walker D(ed), Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 12, Plateau. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatters JC, Butler VL, Scott MJ, Anderson DM, Neitzel DA. 1992. A paleoscience approach to estimating the effects of climatic warming on salmonid fisheries of the Columbia River Basin, abstr Pacific Science Organization International Symposium, Pacific Northwest Lab, Richland, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKechnie I, Moss ML, Crockford SJ. 2020. Domestic dogs and wild canids on the northwest coast of North America: animal husbandry in a region without agriculture? J Anthropol Archaeol 60:101209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walton LR, Cluff HD, Paquet PC, Ramsay MA. 2001. Movement patterns of barren-ground wolves in the central Canadian Arctic. J Mamm 82:867–876. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirilyuk A, Kirilyuk VE, Ke R. 2020. Long-distance dispersal of wolves in the Dauria ecoregion. Mamm Res 65:639–646. doi: 10.1007/s13364-020-00515-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tesky JL. 1995. Canis latrans. US Department of Agriculture FS, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Fort Collins, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 54.del Rocío Reyes-Montes M, Pérez-Huitrón MA, Ocaña-Monroy JL, Frías-De-León MG, Martínez-Herrera E, Arenas R, Duarte-Escalante E. 2016. The habitat of Coccidioides spp. and the role of animals as reservoirs and disseminators in nature. BMC Infect Dis 16:550. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1902-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cordeiro RA, Silva KRC, Brilhante RSN, Moura FBP, Duarte NFH, Marques FJF, Cordeiro RA, Filho REM, Araújo RWB, Banderia TJPG, Rocha MFGR, Sidrim JJC. 2012. Coccidioides posadasii infection in bats, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 18:668–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krutzsch PH, Watson RH. 1978. Isolation of coccidioides immitis from bat guano and preliminary findings on laboratory infectivity of bats with Coccidioides immitis. Life Sci 22:679–684. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorris ME, Neumann JE, Kinney PL, Sheahan M, Sarofim MC. 2021. Economic valuation of coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) projections in the United States in response to climate change. Weather Clim Soc 13:107–123. doi: 10.1175/WCAS-D-20-0036.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baptista-Rosas RC, Hinojosa A, Riquelme M. 2007. Ecological niche modeling of Coccidioides spp. in western North American deserts. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1111:35–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorris ME, Cat LA, Zender CS, Treseder KK, Randerson JT. 2018. Coccidioidomycosis dynamics in relation to climate in the southwestern United States. GeoHealth 2:6–24. doi: 10.1002/2017GH000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lauer A, Etyemezian V, Nikolich G, Kloock C, Arzate AF, Sadiq Batcha F, Kaur M, Garcia E, Mander J, Kayes Passaglia A. 2020. Valley fever: environmental risk factors and exposure pathways deduced from field measurements in California. IJERPH 17:5285. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lauer A, Baal JD, Mendes SD, Casimiro KN, Passaglia AK, Valenzuela AH, Guibert G. 2019. Valley fever on the rise—searching for microbial antagonists to the fungal pathogen Coccidioides immitis. Microorganisms 7:31. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bunting LA, Neilson JB, Bulmer GS. 1979. Cryptococcus neoformans: gastronomic delight of a soil ameba. Sabouraudia 17:225–232. doi: 10.1080/00362177985380341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albuquerque P, Nicola AM, Magnabosco DAG, Derengowski LS, Crisóstomo LS, Xavier LCG, Frazão SO, Guilhelmelli F, Oliveira MA, Dias JN, Hurtado FA, Teixeira MM, Guimarães AJ, Paes HC, Bagagli E, Felipe MSS, Casadevall A, Silva-Pereira I. 2019. A hidden battle in the dirt: soil amoebae interactions with Paracoccidioides spp. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13:e0007742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith DFQ, Casadevall A. 2022. Disaster microbiology—a new field of study. mBio 13:e01680–22. doi: 10.1128/mbio.01680-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pappagianis D, Einstein H. 1978. Tempest from Tehachapi takes toll or Coccidioides conveyed aloft and afar. West J Med 129:527–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneider E, Hajjeh RA, Spiegel RA, Jibson RW, Harp EL, Marshall GA, Gunn RA, McNeil MM, Pinner RW, Baron RC, Burger RC, Hutwagner LC, Crump C, Kaufman L, Reef SE, Feldman GM, Pappagianis D, Werner SB. 1997. A coccidioidomycosis outbreak following the Northridge, Calif, earthquake. JAMA 277:904–908. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540350054033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tong DQ, Gorris ME, Gill TE, Ardon-Dryer K, Wang J, Ren L. 2022. Dust storms, Valley fever, and public awareness. Geohealth 6 e2022GH000642. doi: 10.1029/2022GH000642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gade L, McCotter OZ, Bowers JR, Waddell V, Brady S, Carvajal JA, Sunenshine R, Komatsu KK, Engelthaler DM, Chiller T, Litvintseva AP. 2020. The detection of Coccidioides from ambient air in Phoenix, Arizona: evidence of uneven distribution and seasonality. Med Mycol 58:552–559. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Comrie AC. 2021. No consistent link between dust storms and Valley fever (Coccidioidomycosis). Geohealth 5:e2021GH000504. doi: 10.1029/2021GH000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kolivras KN, Comrie AC. 2003. Modeling Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) incidence on the basis of climate conditions. Int J Biometeorol 47:87–101. doi: 10.1007/s00484-002-0155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Comrie AC. 2005. Climate factors influencing coccidioidomycosis seasonality and outbreaks. Environ Health Persp 113:688–692. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Comrie AC, Glueck MF. 2007. Assessment of climate-coccidioidomycosis model: model sensitivity for assessing climatologic effects on the risk of acquiring coccidioidomycosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1111:83–95. doi: 10.1196/annals.1406.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mazi PB, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, Coler-Reilly A, Rauseo AM, Pullen M, Zuniga-Moya JC, Powderly WG, Spec A. 2022. The geographic distribution of dimorphic mycoses in the United States for the modern era. Clin Infect Dis::ciac882. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]