ABSTRACT

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, has evolved into multiple variants. Animal models are important to understand variant pathogenesis, particularly for variants with mutations that have significant phenotypic or epidemiological effects. Here, cohorts of naive or previously infected Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) were infected with variants to investigate viral pathogenesis and disease protection. Naive hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 variants had consistent clinical outcomes, tissue viral titers, and pathology, while hamsters that recovered from initial infection and were reinfected demonstrated less severe clinical disease and lung pathology than their naive counterparts. Males had more frequent clinical signs than females in most variant groups, but few sex variations in tissue viral titers and lung pathology were observed. These findings support the use of Syrian hamsters as a SARS-CoV-2 model and highlight the importance of considering sex differences when using this species.

KEYWORDS: breakthrough infection, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Syrian hamster, variant, animal models, coronavirus, laboratory animals

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants are genetic lineages of the virus with mutations that alter virus replication, disease, transmission, or evasion of adaptive immune responses (1). These were initially noted in early 2020, only a few months after the first reported COVID-19 cases (2). Multiple genetically distinct variant lineages have since emerged, and have been classified based on their genomic sequences via the Pango dynamic nomenclature system (3). An epidemiological classification system was also established to characterize variants with potentially deleterious human health consequences into three categories: variants under monitoring (VUM), variants of interest (VOI), and variants of concern (VOC), with VOC having the most potential for impacting public health and disease outcomes (2). The WHO further labels individual VOC and VOI using the Greek alphabet (2). Table 1 identifies the isolate, Pango lineage, and WHO Greek alphabet designation (as applicable) for variants used in this study.

TABLE 1.

List of variants utilized

| Variant full name | Collection date | Pango lineage | WHO name (as applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2/USA-WA1/2020 | 19 January 2020 | A.1 | |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP02153/2021 | 2 February 2021 | A.2.5 | |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP00076/2020 | 11 March 2020 | A.3 | |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP12112/2021 | 1 January 2021 | B.1.1.207 | |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP01542/2021 | 21 January 2021 | B.1.351 | Beta |

| SARS-CoV-2/ USA/CA-Stanford-02_S43/2021 | 13 January 2021 | B.1.427 | Epsilon |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP03867/2021 | 1 April 2021 | P.1.17 | Gamma |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP05660/2021 | 2 May 2021 | AY.106 | Delta |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP20874-PIDUYWZOWA/2021 | 27 November 2021 | BA.1.18 | Omicron |

| SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP06587-PIDGNNWCBG/2021 | 15 June 2021 | B.1.621 | Mu |

Animal models have been used to study SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis, transmission, vaccine candidates, and therapeutics (4). As with previous coronaviruses, Syrian hamsters stand out as an animal model (5). The virus replicates efficiently in their airways and nasal passages without progressing to severe disease in adult animals (6–8), modeling the outcome most seen in human patients. Syrian hamsters offer a valuable resource for understanding the growing complexities of COVID-19, such as the effect of multiple infections on morbidity and long-term sequalae (9–11), the protective immunity conferred from vaccines and previous infections (12–15), and the impact variant differences have on these outcomes (16–20). Here, differences in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 variants in naive or previously infected hamsters were investigated using clinical outcomes, lung histopathology, and respiratory tissue viral titers. We hypothesized that hamsters would display mild phenotypes following variant infection, similar to previous reports, and that reinfected hamsters would have reduced clinical signs and milder lung histopathology across variant groups.

RESULTS

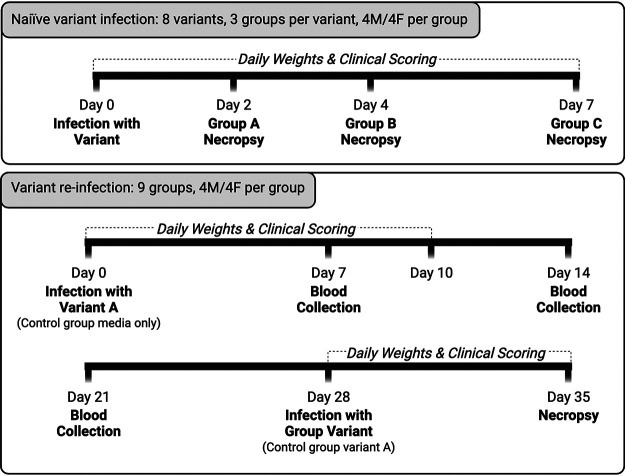

Naive and previously infected hamsters were infected with SARS-CoV-2 variants and underwent clinical monitoring, histopathologic lung scoring, and respiratory tissue viral titer analyses. Figure 1A shows the sample collection timeline for each of these experimental designs.

FIG 1.

Experimental timeline. (A) Timeline for the naive variant infection groups. Hamsters were inoculated with a variant and then clinically scored and weighed daily until euthanasia at 2, 4, or 7 dpi. (B) Variant reinfection groups’ timeline. Hamsters were inoculated with variant A and then received clinical scoring and weighed daily until 10 dpi. At 28 dpi, hamsters were reinfected with a variant, followed by an additional 7 days of weighing and clinical scoring before euthanasia at 35 dpi. Blood was collected at 7, 14, and 21 dpi.

Naive infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants.

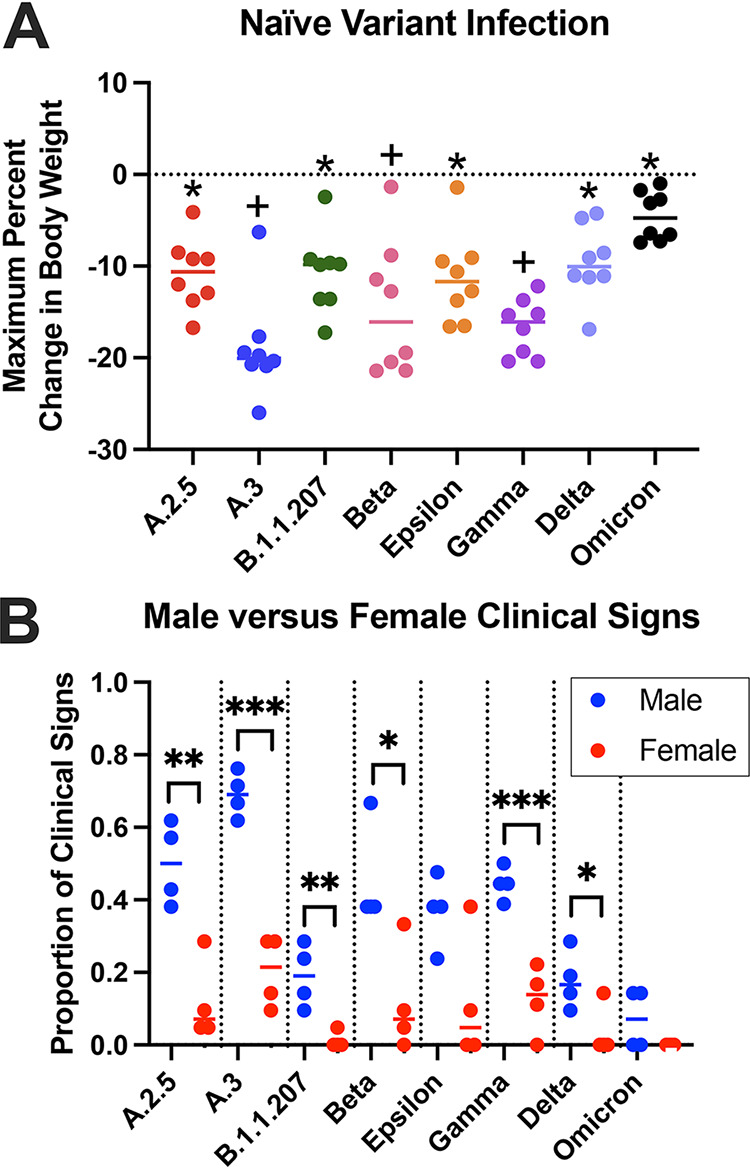

(i) Clinical outcomes. Clinical outcomes were monitored daily to evaluate differences between variants and sexes. Hamsters lost body weight (BW) over the first 6 days postinfection (dpi) and began regaining weight at 7 dpi, with some differences in mean BW appreciated. Groups infected with A.3 exhibited significantly more BW loss than groups infected with A.2.5, B.1.1.207, Epsilon, Delta, and Omicron, losing up to 26% BW by 6 dpi. Omicron-infected animals lost significantly less BW than the A.3-, Beta-, and Gamma-infected groups, with a maximal loss of only 6% BW (Fig. 2A). There was no significant sex-associated impact on BW.

FIG 2.

Clinical signs following naive infection. (A) Maximum percentage of body weight change over 7 dpi. Using a one-way ANOVA, few significant differences in body weight changes were observed between variant groups, apart from the Omicron group experiencing significantly less weight loss than several groups (denoted with +) and A.3 group experiencing significantly more weight loss than several other groups (denoted with *). (B) Although few sex differences were observed between variant groups for body weight change, significant differences were noted in the frequency of other clinical signs between all groups except Omicron and Epsilon (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Other clinical signs were recorded as present or absent after observation in the home cage before handling. Hamsters exhibited rough hair coat, orbital tightening, and hunched posture. Males displayed these more frequently than females in all groups, with six out of eight groups showing a significant sex difference (Fig. 2B). When observed over 7 dpi, males infected with Delta and Omicron had clinical signs less frequently than males infected with A.2.5, A.3, Beta, and Gamma. The Omicron-infected males also had less frequent clinical signs than Epsilon-infected males. Female hamsters exhibited no significant differences in clinical signs between variant groups.

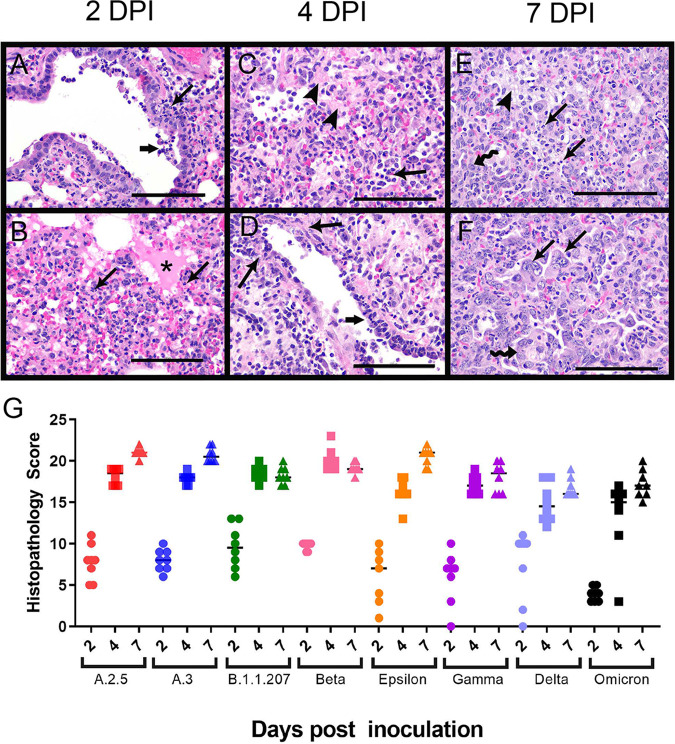

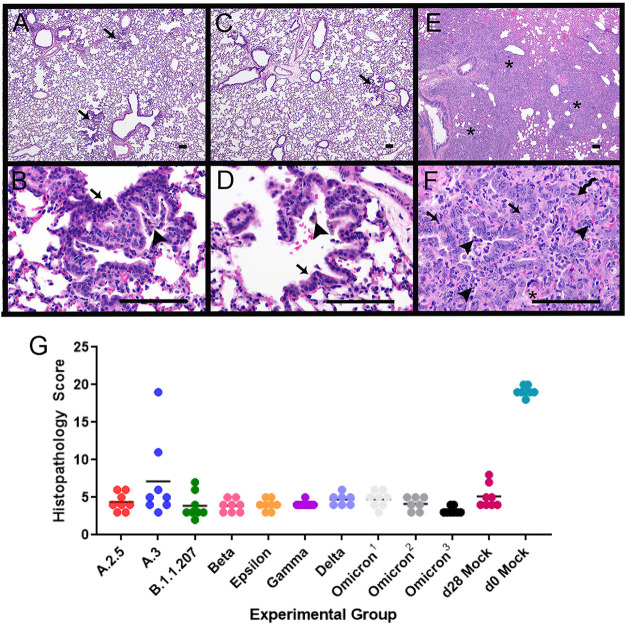

(ii) Histopathology. Histopathological changes were evaluated to monitor respiratory disease progression 2, 4, and 7 dpi. Changes within the lungs were largely consistent across variants, with the majority of lesion variability observed between different days postinfection. At 2 dpi, lung lesions consisted of small to moderate amounts of intraluminal bronchial and bronchiolar inflammatory and epithelial cellular debris, intra-alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, necrotic cellular debris, fibrinous exudate, and hypertrophied vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 3A and B). In most variant infections, there was mild suppurative bronchitis and bronchiolitis, except for A.2.5 and Epsilon, where these features were only present in one or two animals, respectively. Other variable changes across groups include bronchial epithelial hyperplasia, alveolar hemorrhage and edema, and perivascular lymphocytic aggregates. Epithelial syncytia were rare.

FIG 3.

Histopathology of the lungs following naive infection. Histopathologic changes of the lungs were consistent between variants at each time point. Representative images from each time point from different variants are shown. (A and B) Two days postinfection. (A) Suppurative bronchitis and bronchiolitis (long arrow) and bronchial epithelial cell necrosis along with inflammatory cell and necrotic cellular debris within the airways (short arrow) as observed in the Epsilon variant; (B) alveolar edema (*) and inflammatory cells (arrows), including large numbers of neutrophils and macrophages as observed in Gamma variant. (C and D) Four days postinfection. (C) Organizing fibrin in the alveoli (arrowhead) and numerous inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrow) as observed in the B.1.1.207 variant; (D) vasculitis/vascular endothelialitis characterized by loss of vessel wall integrity and eosinophilic proteinaceous material within the vessel wall (long arrows) and subendothelial mononuclear cells and neutrophils with endothelial cell swelling and necrosis (short arrow) as observed in the B.1.1.207 variant. (E and F) Seven days postinfection. (E) Organizing fibrin within the alveoli (arrowhead), degenerate inflammatory cells within alveoli (arrows), and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (squiggle arrow) as observed in the A.2.5 variant; (F) multinucleated sloughed epithelial cells (arrows), type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (squiggle arrow), and intra-alveolar inflammatory cells as observed in the A.3 variant. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (G) Histopathology scores of naive infection groups. Please see Fig. S2 for a complete list of P values from multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA. Each variant exhibited a similar trend with respect to scores at 2 dpi (circles), 4 dpi (squares), and 7 dpi (triangles). Across time points, Omicron-infected animals had lower histopathology scores than animals infected with A.3, B.1.1.207, and Beta variants at 2 dpi, all variants except Epsilon and Delta at 4 dpi, and all variants except B.1.1.207, Gamma, and Delta at 7 dpi. Animals infected with Delta had lower histopathology scores than those infected with B.1.1.207 and Beta variants at 4 dpi and all variants except B.1.1.207, Gamma, and Omicron at 7 dpi.

Percentage of weight change over 7 days following variant naive infection and variant reinfection. (A to H) Naive hamsters consistently lost weight after infection, while reinfected hamsters showed little to no initial weight loss followed by weight gain over 7 dpi. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 13.6 MB (13.9MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

At 4 dpi, alveolar and perivascular edema was still appreciable and similar in severity to the edema seen at 2 dpi. However, the perivascular lymphocytic aggregates, intra-alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, necrotic cellular debris, and organized fibrinous exudate were more severe at 4 dpi than at 2 dpi. Additional lesions at 4 dpi included atypical type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and vasculitis (Fig. 3C and D). Vasculitis, when observed, was usually present in medium-size arteries and veins and was characterized by loss of vessel wall integrity due to transmural effacement by inflammatory cells and necrosis, eosinophilic proteinaceous material within the vessel wall, or subendothelial mononuclear cells and neutrophils with endothelial cell swelling and necrosis. Similar lesions in human patients are described as endothelialitis (21), which has also been used in the literature on hamster models (22–25). Suppurative bronchitis and bronchiolitis were variably present across groups at 4 dpi. Most animals infected with A.2.5, A.3, Epsilon, Gamma, and Delta demonstrated this lesion. However, fewer animals infected with Omicron and Beta variants and no animals infected with B.1.1.207 had this lesion.

At 7 dpi, the most consistent and striking lesion appeared as areas of robust, atypical type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (Fig. 3E and F), which was seen in all animals and was usually present in at least 50% of tissue sections. Cells were up to 40 μm in diameter, cuboidal to polygonal, with round to oval nuclei up to 15 μm in diameter that contained finely stippled chromatin and 1 to 3 prominent nucleoli. These cells had variable amounts of cytoplasm and occasionally were bi- or trinucleate, with numerous mitotic figures. Within the alveolar spaces and expanding the alveolar septa were large numbers of macrophages, with fewer neutrophils and lymphocytes, as well as fibrinous eosinophilic exudate. There was also bronchial and bronchiolar luminal necrotic cellular debris bronchial epithelial hyperplasia, perivascular lymphocytic aggregates, and vascular endothelial hypertrophy.

Lung histopathology was also evaluated using a scoring system shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Most variants exhibited a similar histopathological trend, with scores increasing over time and no significant difference between sexes appreciated (Fig. 3G). An exception was animals infected with B.1.1.207 and Beta variants, which had higher scores at 4 dpi than 7 dpi. These animals also had the highest 4 dpi scores across all variant groups. The lower scores at 7 dpi were due to lower percentages of tissue affected, smaller clusters of perivascular lymphocytes, and fewer animals with multinucleated or atypical bronchial epithelial cells. Omicron-infected animals had statistically lower histopathology scores than those infected with A.3, B.1.1.207, and Beta at 2 dpi, all variants except Epsilon and Delta at 4 dpi, and all variants except B.1.1.207, Gamma, and Delta at 7 dpi. Delta-infected animals had lower histopathology scores than B.1.1.207- and Beta-infected animals at 4 dpi and all variants except B.1.1.207, Gamma, and Omicron at 7 dpi. Despite overall lower histopathology scores, Omicron-infected animals demonstrated similar lesions to those associated with other variants (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Histopathology of the lungs, Omicron variant. (A and B) Two days postinfection. (A) Suppurative bronchitis (arrowheads), with bronchial epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis; (B) intra-alveolar organized fibrin (arrows) and increased inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrowhead) within the alveolar septa and spaces. (C and D) Four days postinfection. (C) Vasculitis/vascular endothelialitis characterized by subendothelial aggregates of neutrophils and mononuclear cells (arrows), as well as perivascular accumulation of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (*); (D) organized fibrin (*) within the alveoli along with increased numbers of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrowheads). (E and F) Seven days postinfection. (E) Low magnification indicating the extent of the consolidation (*) of the alveoli; (F) higher magnification indicating type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrow), inflammatory cells, including neutrophils (arrowhead), macrophages, and fewer lymphocytes, and multinucleated epithelial cells (squiggle arrow). The scale bar represents 100 μm in all images. Download FIG S1, TIF file, 6.9 MB (7.1MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Histopathologic scoring system used blind by a board-certified veterinary pathologist to analyze hamster lung tissue. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.03 MB (35.2KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

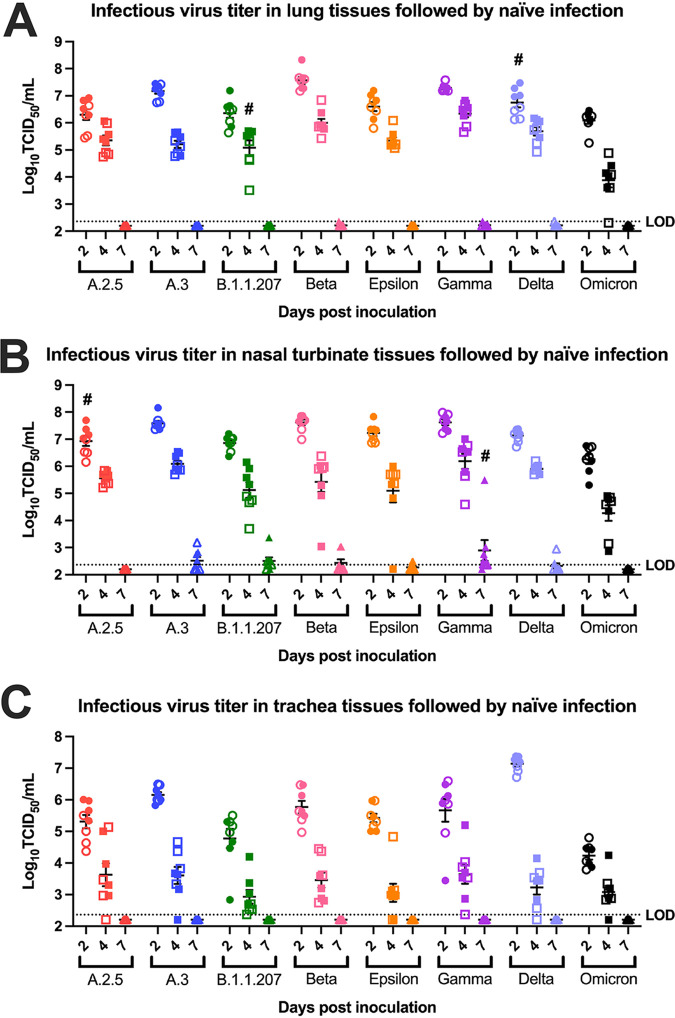

(iii) Viral titers. Lung, tracheal, and nasal turbinate titers were measured to evaluate viral tropism in respiratory tissues over time. Overall, the highest viral titers were observed at 2 dpi in all tissue types, with lungs and nasal turbinates having higher titers than the trachea (Fig. 4A to C). All variant groups displayed a quick decrease in infectious virus load at 4 dpi, while no infectious virus was detected in the lung or tracheal samples at 7 dpi (Fig. 4A to C).

FIG 4.

Viral titers in respiratory tissues following naive infection. (A) Mean infectious viral titers in lung tissues at 2 dpi (circles), 4 dpi (squares), and 7 dpi (triangles) after naive infection (n = 8). Significant differences in tissue viral titers were observed between some variants at 2 dpi and 4 dpi. Notably Beta and Gamma had higher titers and Omicron had lower titers at both 2 dpi and 4 dpi. No significant difference was observed at 7 dpi. Groups that displayed sex differences in viral titers are indicated by #, with males being higher than females. Hollow circles, squares, and triangles represent data points for female animals. (B) Mean infectious viral titers in nasal turbinate tissues at 2 dpi (circles), 4 dpi (squares), and 7 dpi (triangles) after naive infection (n = 8). Few significant differences in viral titers were observed between variants, apart from Omicron having lower titers at 2 dpi and 4 dpi. No significant difference was observed at 7 dpi. Groups that displayed sex differences in viral titers are indicated by #, with males being higher than females. Hollow circles, squares, and triangles represent data points for female animals. (C) Mean infectious viral titers in trachea tissues at 2 dpi (circles), 4 dpi (squares), and 7 dpi (triangles) after naive infection (n = 8). Delta had the highest titers in all variants tested, and Omicron had lower titers than all other variants at 2 dpi. No significant differences in tracheal titers were observed between variants at 4 dpi or 7 dpi or between sexes at all time points. Hollow circles, squares, and triangles represent data points for female animals. Viral titer was measured by TCID50 assay, with a limit of detection at 2.36 log10 TCID50s/mL. One-way ANOVA was done on all three tissue types with Turkey’s multiple-comparison tests (P < 0.05). Please see Table S4 for the complete list of P values for multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA.

Results of multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA of viral titer at 2, 4, and 7 dpi for naive infected animals’ lung, trachea, and nasal turbinates. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.05 MB (48.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Significant differences in mean viral titers were observed between variants for all three tissue types, with Omicron-infected animals displaying consistently lower tissue titers than other groups. In lung tissues, the most prominent difference was noted at 4 dpi, with the Omicron group having significantly lower lung titers than all other groups, while the Beta and Gamma groups had significantly higher titers than all groups except the Delta group (Fig. 4A). At 2 dpi, this trend was still appreciable and Omicron-infected animals had significantly lower titers than animals infected with other variants except A.2.5, B.1.1.207, and Epsilon, which were not significantly different (Fig. 4A; Table S4). Beta-infected animals had the highest overall lung titer and, along with Gamma-infected animals, had significantly higher titers than those infected with A.2.5, B.1.1.207, Epsilon, and Omicron. Delta-infected animals had comparable lung titers to those infected with A.2.5, A.3, B.1.1.207, Epsilon, and Gamma, while being significantly lower than Beta-infected animals and higher than Omicron-infected animals. Delta was the only variant with sex differences in lung titers at 2 dpi, with males having significantly higher mean titers than females (Fig. 4A). At 4 dpi, the only sex difference appreciated was B.1.1.207-infected males having significantly higher titers than females (Fig. 4A). Altogether, infectious viral titers in lung tissues were higher in Beta-infected animals and lower in Omicron-infected animals. These results correlate well with histopathology findings, supporting an early infection followed by a reparative phase for all reinfection groups (Fig. 3G).

In nasal turbinates at 2 dpi, Omicron-infected animals had significantly lower viral titers than those infected with A.3, Beta, and Gamma (Fig. 4B). Although the A.3, Beta, and Gamma groups trended toward having higher nasal turbinate titers at this time point, statistical tests suggested no significance. A.2.5-infected animals displayed sex differences in nasal turbinate titers at 2 dpi, with males having higher viral titer than females (Fig. 4B). At 4 dpi, Omicron-infected animals continued to have the significantly lowest nasal turbinate viral titer. Gamma-infected animals had the highest, with significantly higher titers than B.1.1.207-, Epsilon-, and Omicron-infected animals. At 7 dpi, low nasal turbinate titers were detectable for a few animals from multiple variant groups, with the exception of the Gamma group, which had detectable virus in 7 out of 8 hamsters’ nasal turbinates (Fig. 4B). Within the Gamma-infected animals at this time point, males demonstrated a significantly higher nasal turbinate titer than females.

At 2 dpi, Omicron-infected animals had the significantly lowest tracheal viral titer, while Delta-infected animals exhibited the highest (Fig. 4C). Tracheal tissue viral titers at 4 dpi had more variability between variants than other tissue types, but these differences were not statistically significant. There were no sex differences in tracheal titers at all time points.

Reinfection.

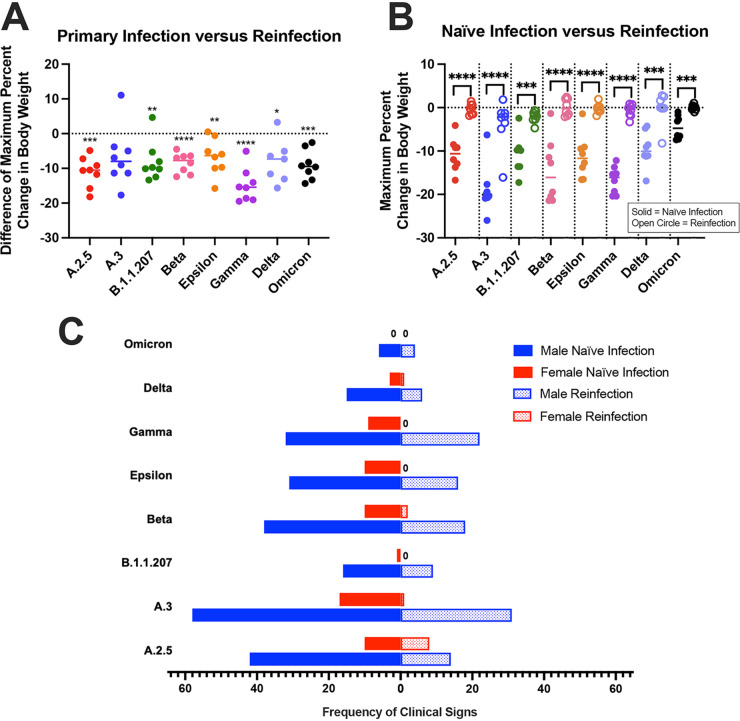

(i) Clinical outcomes. To investigate if previous SARS-CoV-2 infection ameliorates the frequency of clinical signs observed after reinfection, hamsters were inoculated with variant A and then a different variant 28 days later. After the first infection, hamsters lost up to 24% BW over the first 6 dpi and then began gaining weight around 7 dpi. They continued to gain BW until reinfection, after which their weights plateaued or slightly decreased immediately following inoculation, before increasing again, typically around 2 or 3 dpi. Figure S2A to H compare these trends in percentage of BW change after reinfection to that seen with naive infected animals for each variant. Figure 5A (see Table S2 for P-values) displays the difference in BW change for each hamster between its initial infection and reinfection, with significantly less weight loss seen after reinfection, except for animals infected with variant A.3 at 28 dpi, which showed no significant difference. The nonsignificance for the A.3-reinfected hamsters may be attributed to one hamster that exhibited a weight loss pattern similar to that of a naive infected animal. The mock-inoculated group lost significantly more BW following infection at 28 dpi than other groups. The mean percentage of BW change after reinfection was also significantly different from that of naive animals infected with the same variant, with naive animals losing more BW (Fig. 5B, see Table S2 for P-values). There were no sex differences in BW change in these groups following reinfection.

FIG 5.

Clinical signs following reinfection. (A and B) Maximum percentage of body weight change over 7 dpi. (A) The difference in each hamster’s weight change between primary infection with variant A and reinfection with another variant was compared using paired t test, with almost all animals showing significantly less weight loss after reinfection. (B) Compared using two-sample t tests, naive hamsters infected with a variant lost significantly more weight than their counterparts that were reinfected with a variant after previous infection with variant A. (C) The frequency of clinical signs (hunched posture, orbital tightening, and rough hair coat) is shown for naive male and female hamsters at 7 dpi as well as male and female hamsters at reinfection at 7 dpi. Clinical signs were observed less in reinfected male hamsters versus naive male hamsters except for Omicron- and Delta-infected animals. A.3- and Gamma-reinfected females had significantly less clinical signs than their naive counterparts (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

The presence and frequency of clinical signs were recorded over 7 dpi for both infections as described above. Male hamsters displayed more frequent clinical signs (rough hair coats, orbital tightening, and hunched posture) than females after both initial infections and reinfections (Fig. 5C). Significantly fewer clinical signs were observed after reinfection for males infected with A.2.5, B.1.1.207, Delta, and Omicron and females infected with Gamma. Almost all male groups displayed fewer clinical signs following reinfection than naive males infected with the same variant, except for those infected with B.1.1.207, Delta, and Omicron, which had a low frequency of clinical signs for both infections (Fig. 5C). Females previously infected with A.3 and Gamma also had significantly fewer clinical signs than their naïvely infected counterparts.

To evaluate if the initial variant influences reinfection outcomes, separate cohorts of animals were reinfected with Omicron 28 days after initial infection with Delta or Mu. These hamsters exhibited similar weight change trends to hamsters infected with variant A before Omicron reinfection (Fig. S3A and B). There were no significant differences in weight change between reinfected hamsters based on the variant they were initially infected with; however, all three groups of hamsters reinfected with Omicron had significantly less BW change than naive Omicron-infected hamsters. The frequency of clinical signs between reinfection groups was not significantly different.

Percentage of change in body weight after naive Omicron infection and Omicron reinfection. (A) Using a one-way ANOVA, the maximum percentages of change in body weight over 7 dpi were compared between naive hamsters infected with Omicron and hamsters reinfected with Omicron 28 days after initial infection with variant A, Mu, or Delta. There were no significant differences between reinfection groups, but all three reinfection groups had significantly less change in percentage of body weight than naive Omicron-infected hamsters (P < 0.05). (B) The percentage of change in body weight is shown over 7 dpi with Omicron. Naive hamsters infected with Omicron lost weight, while reinfected hamsters all gained weight on average regardless of their initial infection type. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 7.5 MB (7.5MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

(ii) Histopathology. Histopathology was performed on lung tissues at 7 dpi following reinfection (35 dpi initial infection) (Fig. 6). Animals had largely unaffected lungs 7 days after reinfection. In all variant groups, there were clusters of regular, cuboidal type II pneumocyte hyperplasia admixed with pigmented macrophages. Less consistent features across variants include alveolar hemorrhage and edema and perivascular lymphocytic aggregates.

FIG 6.

Histopathology of the lungs following reinfection. (A and B) Representative images from reinfection with the Delta variant. (A) Low magnification showing largely unremarkable lung with few foci of residual type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrows). (B) Higher magnification showing type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrow) and clusters of intra-alveolar clusters of pigmented macrophages (arrowhead). (C and D) Representative images from mock reinfection. (C) Low magnification showing largely unremarkable lung with foci of residual type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrow); (D) higher-magnification view of type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrow) and intra-alveolar pigmented macrophage (arrowhead). (E and F) Representative images from day 0 mock infection with variant reinfection. (E) Low-magnification view indicating widespread consolidation of the alveolar spaces (*); (F) higher magnification showing type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrows), intra-alveolar inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrowheads), organizing fibrin within alveoli (*), and multinucleated epithelial cells (squiggle arrow). All scale bars represent 100 μm. (G) Histopathology scores of reinfection groups. Animals were intranasally infected with the A variant at day 0, infected with an additional variant at 28 dpi, and euthanized at 35 dpi. “Omicron1” represents initial infection with Delta and reinfection with Omicron. “Omicron2” represents initial infection with Mu and reinfection with Omicron. “Omicron3” represents initial infection with A and reinfection with Omicron. “d28 mock” indicates the animals were infected with the A variant at day 0 and mock inoculated with medium only at 28 dpi. “d0 mock” indicates the animals were mock inoculated with medium only at day 0 and inoculated with the A variant at 28 dpi. Please see Table S3 for a complete list of P values from multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA. Secondary variant infection at 28 dpi produced similar histopathology scores. The d0 mock histopathology scores were statistically significantly higher (P < 0.0001 for multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA) than all other groups. Variant A.3 had 2 animals with high histopathology scores, but scores were otherwise similar to all other groups.

Results of multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA of maximum percentage of body weight change for naive infected animals at 7 dpi, unpaired t test of maximum percentage of body weight change, and clinical sign frequency for naive infected animals at 7 dpi versus reinfected animals at 7 dpi, and paired t test of maximum percentage of body weight change for initial infection 7 dpi versus variant reinfection 7 dpi. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.04 MB (39.2KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Results of multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA of histology scoring for naive infected animals at 2, 4, and 7 dpi and reinfected animals at 7 dpi. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.04 MB (41.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

In animals mock inoculated at day 28, there were clusters of type II pneumocyte hyperplasia with aggregates of pigmented macrophages, similar to hamsters that underwent two infections. In animals that were mock inoculated at day 0 and inoculated at day 28 with variant A, there was robust atypical type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, as described previously in the 7-dpi pathogenesis groups, along with abundant intra-alveolar and intraseptal macrophages. The day 0 mock-inoculated animals had statistically higher histopathology scores than all other groups. Animals infected with variant A.3 had statistically higher histopathology scores than the other groups, but this was largely attributed to one animal with widespread atypical type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and alveolar infiltrates as described for 7-dpi pathogenesis animals.

Tissue viral titer analyses were not performed for these groups as animals were euthanized at 7 days after reinfection, and low tissue viral loads at 7 dpi from this study and others have been reported (6, 26).

DISCUSSION

SARS-CoV-2 variants have emerged with mutations affecting viral angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) binding affinity, replication, transmission, antibody recognition, and clinical disease (1, 27). Validation of animal models that accurately demonstrate disease caused by these variants is important for studying variant pathogenesis and assessing efficacy of therapies and vaccines. Here, Syrian hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 variants displayed clinical outcomes, lung pathology, and tissue viral titers, as previously described (28–30), with some differences observed between variants and between sexes within variant groups.

BW loss was a reliable clinical indicator of SARS-CoV-2 infection in this study. It was observed across variants regardless of sex, with naive hamsters losing weight over the first 6 dpi before beginning to recover on 7 dpi. This is consistent with previous studies reporting around 10 to 14% BW loss (7, 25, 26, 28–32) and similar patterns of recovery (6, 30). While all groups followed this pattern, some variant groups exhibited significant BW differences. A.3-infected animals demonstrated the most significant BW loss, particularly in males. This was an unexpected outcome as A.3 is genetically similar to the originally circulating virus, with minimal mutations, and the groups that exhibited relatively less weight loss were infected with variants possessing multiple mutations known to affect viral fusogenicity and infectivity (1, 27, 33, 34). Previous studies with a similar lineage did not report this severity of BW loss despite similar lung pathology (6, 26). We postulate that these differences could be due to variations in inoculation procedures or viral preparation. Despite the increased severity of clinical disease, A.3-infected animals had similar lung histopathology scores and tissue viral titers to most other groups. While this variant is no longer dominantly circulating among humans, our findings are useful as they highlight potential differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection between hamsters and humans.

The groups with the least BW loss were infected with Omicron, which is consistent with previous reports of Omicron clinical presentations in hamsters and human patients (35–40). In one study comparing Delta and Omicron infection in Syrian hamsters, Omicron caused less BW loss and lower viral loads in throat swabs and nasal wash samples (41). Due to its dominance in the population, Omicron is a priority for therapeutic and preventative research, particularly as it continues to evolve into multiple sublineages. In this study, we evaluated the early sublineage BA.1, referred to as Omicron throughout this article.

The etiology of BW loss in infected hamsters is not entirely understood, but it likely recapitulates the condition in human patients. Weight loss and clinical cachexia (muscle wasting from chronic disease) in people can be attributed to factors like loss of appetite and taste, anosmia, fever and inflammation, and metabolic imbalances (42, 43). While we did not evaluate appetite, taste, or smell, anosmia in infected hamsters has been reported to occur at 2 to 5 dpi (44, 45), which correlated with the period of maximal weight change (6, 30, 44, 45). Meanwhile, there is limited description on SAR-CoV-2 effects on hamster core body temperatures, but one study reported no changes following infection with an early variant (46). We postulate that the weight loss in hamsters is associated with inappetence, which could be a result of anosmia as correlated with the histological damage within the olfactory epithelium (44, 47). Additional studies examining the relationship of weight loss with these factors may elucidate its etiology.

The other clinical signs observed across variant groups were consistent with previous studies (28, 30); however, respiratory signs like rapid breathing have also been reported (29). As with our study, the majority of the literature describes minimal (6) to no (28) respiratory signs (25, 30). Such clinical severity differences could be attributed to factors like viral inoculation dose, with higher doses resulting in increased morbidity (29).

The influence of sex on clinical sign frequency in our animals mirrors the increased COVID-19 morbidity documented in male human patients (48–52). Male hamsters displayed more frequent clinical signs than females, which is also consistent with previous reports of increased morbidity in male hamsters (26, 51, 53). Moreover, intervariant differences in clinical sign frequencies were observed in male hamsters, suggesting they may be more sensitive to phenotypic effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection than females, both in the context of the initial infection and after reinfection. Of note, despite differences in the overall clinical sign frequencies, there were no sex differences associated with BW change up to 7 dpi for all groups, which is consistent with previous reports (26, 29, 51); however, some studies of longer duration noted that male hamsters regained less weight than females from 8 to 28 dpi (26, 51). Sex differences emphasize the importance of accounting for sex in SARS-CoV-2 research.

Overall, histopathological features were similar among all variants and consistent with previous literature (6, 7, 22, 25, 32, 54–56). Inflammatory lesions present at 2 dpi supported acute damage, which then progressed in severity by 4 dpi. In some animals, evidence of repair, such as type II pneumocyte hyperplasia, was already present by 4 dpi, but there was no obvious correlation to sex or variant with these repairs. At 7 dpi, lesions were consistent with further progression into the reparative phase, as characterized by extensive type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. In most variants, lesions were more extensive at 7 dpi; however, there were more features present at 4 dpi. As a result, two variants (B.1.1.207 and Beta) had higher histopathology scores at 4 dpi than 7 dpi. The histopathologic progression is consistent with the weight trends observed, with an immediate response to infection and gradual recovery toward 7 dpi. In people, respiratory lesions are primarily characterized by imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) (57, 58). The sensitivity of CT for diagnosing infection in humans increases significantly when symptom duration is longer than 48 h, after which increased lung consolidation and ground glass opacities are observed (58). CT has been used to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 in hamsters, with similar findings to human patients (7), and offers a viable option for evaluating lung pathology over time in this model (26, 30).

Omicron-infected animals had lower overall histopathology scores than most variants despite similar lesions observed (Fig. S1), likely due to lower percentages of affected tissue, fewer perivascular lymphocytes, and fewer atypical or multinucleated bronchial epithelial cells. Our findings differed slightly from previous reports that used lower inoculation doses, where hamsters demonstrated milder pneumonia when infected with Omicron than when infected with the Delta variant (35, 38). These studies found that Omicron-infected animals had milder features of pneumonia, including multiple small foci of inflammatory cells in the alveoli and peribronchial areas observed only at 6 dpi, with no changes noted at 3 dpi (38), or decreased areas of type II pneumocyte hyperplasia at 5 and 7 dpi (35).

All variant groups displayed a quick decrease in infectious virus load in respiratory tissues from 2 dpi to 4 dpi, and by 7 dpi, there were low to no detectable infectious viral particles. This pattern is similar to previous reports for hamsters infected with a clade A variant (6, 26, 29). The viral titer levels at 7 dpi coincide with the peak BW loss at 6 dpi and then recovery observed in this study and others (6). However, higher inoculation doses could result to consistently higher viral titer loads at 2 and 4 dpi, as previously reported (29). In our study, the high titer levels in the nasal turbinates and lungs may be attributed to the nasal cavity inoculation and more effective viral replication at 37°C in the lower respiratory track, respectively.

There was a reduction in clinical phenotype and lung pathology upon SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Previously infected hamsters had significantly less BW loss than their naively infected counterparts, and the majority of groups had less frequent other clinical signs. Additionally, in 79/80 animals that were reinfected, lesions at 35 dpi (i.e., 7 days post-reinfection) were identical to those of the control group that received only one infection with variant A on day 0 and were mock inoculated at 28 dpi. These changes included residual type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and small foci of perivascular and intra-alveolar inflammatory cells, which were consistent with chronic, rather than acute, change. In contrast, animals mock inoculated at day 0 and inoculated at 28 dpi displayed changes more like those observed in 7-dpi animals. One animal in the reinfection cohort demonstrated findings similar to those found in animals euthanized at 7 dpi. Serology performed at 28 dpi on this hamster revealed no neutralizing antibodies (neutralizing antibody titer of <1:20 against the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine strain), indicating that there was likely a failure of primary inoculation. Protective antibody responses of variable durations are described in human cases, both from previous infection and vaccines (59–61). Overall, our findings indicate that some degree of protection against reinfection is generated during primary infection.

A.3- and Omicron-infected groups demonstrated clear phenotypic differences from other groups, supporting the recommendation that all variants should be characterized in the hamster model. Despite differences in reported transmissibility, viral replication, and clinical outcomes in humans and ex vivo studies (1, 2), the other variants analyzed were phenotypically similar. This suggests that although there are benefits as an animal model overall, the hamster model may not be specific enough to differentiate minor differences between certain variants. Despite this, preliminary studies on emerging variants using the model are still valuable for characterization before further investigation is conducted.

While we evaluated the effect of sex on different variants, there are other factors that can influence SARS-CoV-2 infection. Age has been shown to significantly affect disease outcomes in people (62–64) and in hamsters (22, 65). An additional limitation of our study is its duration; longer studies are needed to investigate effects of long COVID and the longevity of the protection from reinfection. Furthermore, evaluation of the hamster antibody response to different variants is important, as hamsters continue to be used for vaccine and monoclonal antibody (Mab) treatment research (66–68).

Emergence of new variants creates a continued need for SARS-CoV-2 research. Our study findings indicate that Syrian hamsters provide a reliable and consistent animal model for studying SARS-CoV-2 variant infections and reinfections, emphasizing its significance for characterizing disease and investigating effective treatments and vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus preparation.

Virus preparation was performed as previously described by Mulka et al. (6). Briefly,Vero-E6-TMPRSS2 cells (from the Japan Institute of Infectious Diseases) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. SARS-CoV-2 viruses from patient nasal swab samples collected at Johns Hopkins Hospital were used to infect Vero-E6-TMPRSS2 cells to generate virus stocks. Infection was done at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50). Infected-cell supernatant was collected when 75% of cells had observable cytopathic effect (CPE) around 96 h postinfection. The supernatant was centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min and then aliquoted into 500 μL and stored at −70°C. The infectious titer of virus stock was measured by TCID50 assay. Virus stocks were 10-fold serially diluted in DMEM supplemented with 2.5% FBS, 1 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Stock dilutions were transferred in sextuplicate into the 96-well plates confluent with Vero-E6-TMPRSS2 cells, incubated at 37°C for 6 days, and then fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with naphthol blue black solution for visualization. The infectious virus titers in TCID50 per milliliter were determined by the Reed and Muench method.

Animals.

Male and female Syrian hamsters (6 to 8 weeks old) (Envigo, Haslett, MI) were singly housed in negative-pressure individually ventilated cages (PNC) (Allentown, Inc., Allentown, NJ). Animals were provided with corncob bedding (Envigo, Madison, WI), nesting material (Enviro-dri; Shepherd Specialty Papers, Amherst, MA), standard rodent chow (2018SX; Teklad, Envigo, Madison, WI) and RO-DI water through an automated watering system (Edstrom, Avidity Science, Waterford, WI). All animal procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in an AAALAC-accredited facility.

(i) Inoculation, clinical evaluation, and euthanasia. Hamsters were sedated with ketamine-xylazine for inoculation with 105 TCID50 of a SARS-COV-2 variant (Table 1) in 100 μL DMEM (50 μL/naris) or mock inoculated with 100 μL DMEM. Animals were weighed and clinically evaluated blind by an observer for the presence or absence of clinical signs (J.P.). At euthanasia, hamsters were anesthetized using isoflurane for cardiac puncture and tissue harvest.

(ii) Naive SARS-COV-2 variant infection. Hamsters (4/sex/endpoint/variant) were inoculated with a SARS-COV-2 variant. Daily observations and weighing were performed until euthanasia at 2, 4, and 7 dpi (Fig. 1A).

(iii) Variant reinfection. For primary infection, hamsters (4/sex/variant) were inoculated with 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 130 USA-WA1/2020. Negative-control animals (4/sex) were mock inoculated. Twenty-eight days after induction of primary infection, experimental groups were inoculated with 105 TCID50 of a variant (Table 1) and the initially mock-infected animals were inoculated with 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2 130 USA-WA1/2020. Animals were reinfected at 28 dpi because by this time, all animals had returned to their expected weights, showed no detrimental effects of the initial infection, and had reached peak levels of serum SARS-CoV-2 antibodies based on our previous experiments (6, 26). Periodic clinical assessment was performed until euthanasia at 35 dpi (Fig. 1B).

(iv) Delta versus Mu effect on Omicron infection. Hamsters (4/sex/variant) were inoculated with 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP06587-PIDGNNWCBG/2021 or 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP05660/2021. At 28 dpi, hamsters were inoculated again with 105 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2/USA/MD-HP20874-PIDUYWZOWA/2021. Clinical assessment and euthanasia were performed following the time points for the reinfection study described above.

Histopathological analyses.

Histopathological analysis of lung tissues on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides was performed blind by a veterinary pathologist (K.M.) using a scoring system shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material (24, 69, 70). Briefly, the parameters evaluated for their presence or absence include necrosis of bronchiolar epithelial cells (BECs), cellular debris in bronchi and bronchioles, cellular debris in alveoli, intra-alveolar fibrin, alveolar hemorrhage, alveolar edema, perivascular or interstitial edema, vasculitis, plump vascular endothelial cells, necrosuppurative bronchitis, hyperplasia of BEC, hyperplasia of type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), multinucleated or atypical BECs, and multinucleated or atypical AECs. Factors evaluated on a scale from 0 to 4 included percentage of lung affected and perivascular lymphocytes. Intra-alveolar neutrophils and macrophages were evaluated on a scale from 0 to 3.

Tissue homogenization and viral titer analysis.

Animal tissue homogenization and infectious virus titration were done as previously described (6, 26). Briefly, tissue samples were transferred to Lysing Matrix D bead tubes on ice. DMEM supplemented with penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 mg/mL) was added to the tubes at a 10% (wt/vol) ratio. The samples were loaded in a FastPrep-24 benchtop bead beating system (MPBio) and homogenized for 40 s at 6.0 m/s, followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 10,000 × g at room temperature. Tubes were returned to ice, and supernatant was collected and stored at −70°C. The infectious virus titer in tissue homogenates was measure by TCID50 assay as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Paired t tests were used to evaluate differences in BW and clinical signs in reinfection groups. One-sample t tests were used to evaluate sex differences within groups and clinical outcome differences between naive and reinfection. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to evaluate differences between variant group BW, clinical signs, tissue titers, and histology scores. A significance of P < 0.05 was used for all tests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response (NIAID N272201400007C) and the Richard Eliasberg Family Foundation.

We also thank Jacqueline Brockhurst, Natalie Castell, Morgan Craney, Isabel Jimenez, Amanda Maxwell, Andrew Johansen, Lyle Nyberg, and Riley Richardson.

Contributor Information

Jessica Plunkard, Email: jessica.plunkard@gmail.com.

Jason Villano, Email: jvillano@jhmi.edu.

Victoria K. Baxter, Texas Biomedical Research Institute

Kellie Jurado, University of Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raman R, Patel KJ, Ranjan K. 2021. COVID-19: unmasking emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, vaccines and therapeutic strategies. Biomolecules 11:993. doi: 10.3390/biom11070993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boehm E, Kronig I, Neher RA, Eckerle I, Vetter P, Kaiser L, Geneva Centre for Emerging Viral Diseases . 2021. Novel SARS-CoV-2 variants: the pandemics within the pandemic. Clin Microbiol Infect 27:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Toole Á, Pybus OG, Abram ME, Kelly EJ, Rambaut A. 2022. Pango lineage designation and assignment using SARS-CoV-2 spike gene nucleotide sequences. BMC Genomics 23:121. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleary SJ, Pitchford SC, Amison RT, Carrington R, Robaina Cabrera CL, Magnen M, Looney MR, Gray E, Page CP. 2020. Animal models of mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 pathology. Br J Pharmacol 177:4851–4865. doi: 10.1111/bph.15143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muñoz-Fontela C, Dowling WE, Funnell SGP, Gsell P-S, Riveros-Balta AX, Albrecht RA, Andersen H, Baric RS, Carroll MW, Cavaleri M, Qin C, Crozier I, Dallmeier K, de Waal L, de Wit E, Delang L, Dohm E, Duprex WP, Falzarano D, Finch CL, Frieman MB, Graham BS, Gralinski LE, Guilfoyle K, Haagmans BL, Hamilton GA, Hartman AL, Herfst S, Kaptein SJF, Klimstra WB, Knezevic I, Krause PR, Kuhn JH, Le Grand R, Lewis MG, Liu W-C, Maisonnasse P, McElroy AK, Munster V, Oreshkova N, Rasmussen AL, Rocha-Pereira J, Rockx B, Rodríguez E, Rogers TF, Salguero FJ, Schotsaert M, Stittelaar KJ, Thibaut HJ, Tseng C-T, et al. 2020. Animal models for COVID-19. Nature 586:509–515. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2787-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulka KR, Beck SE, Solis CV, Johanson AL, Queen SE, McCarron ME, Richardson MR, Zhou R, Marinho P, Jedlicka A, Guerrero-Martin S, Shirk EN, Braxton AM, Brockhurst J, Creisher PS, Dhakal S, Brayton CF, Veenhuis RT, Metcalf Pate KA, Karakousis PC, Zahnow CA, Klein SL, Jain SK, Tarwater PM, Pekosz AS, Villano JS, Mankowski JL, Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Hamster Study Group . 2022. Progression and resolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in Golden Syrian hamsters. Am J Pathol 192:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai M, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Hatta M, Loeber S, Halfmann PJ, Nakajima N, Watanabe T, Ujie M, Takahashi K, Ito M, Yamada S, Fan S, Chiba S, Kuroda M, Guan L, Takada K, Armbrust T, Balogh A, Furusawa Y, Okuda M, Ueki H, Yasuhara A, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Lopes TJS, Kiso M, Yamayoshi S, Kinoshita N, Ohmagari N, Hattori S-I, Takeda M, Mitsuya H, Krammer F, Suzuki T, Kawaoka Y. 2020. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:16587–16595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009799117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelnabi R, Boudewijns R, Foo CS, Seldeslachts L, Sanchez-Felipe L, Zhang X, Delang L, Maes P, Kaptein SJF, Weynand B, Vande Velde G, Neyts J, Dallmeier K. 2021. Comparing infectivity and virulence of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants in Syrian hamsters. EBioMedicine 68:103403. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. 2022. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med 28:2398–2405. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02051-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. 2022. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 28:1461–1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. 2022. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and COVID-19 hospitalisation in individuals with natural and hybrid immunity: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet Infect Dis 22:781–790. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sette A, Crotty S. 2021. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 184:861–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilz S, Theiler-Schwetz V, Trummer C, Krause R, Ioannidis JPA. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 reinfections: overview of efficacy and duration of natural and hybrid immunity. Environ Res 209:112911. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carazo S, Skowronski DM, Brisson M, Barkati S, Sauvageau C, Brousseau N, Gilca R, Fafard J, Talbot D, Ouakki M, Gilca V, Carignan A, Deceuninck G, De Wals P, De Serres G. 2023. Protection against omicron (B.1.1.529) BA.2 reinfection conferred by primary omicron BA.1 or pre-omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection among health-care workers with and without mRNA vaccination: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis 23:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00578-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carazo S, Skowronski DM, Brisson M, Sauvageau C, Brousseau N, Gilca R, Ouakki M, Barkati S, Fafard J, Talbot D, Gilca V, Deceuninck G, Garenc C, Carignan A, De Wals P, De Serres G. 2022. Estimated protection of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection against reinfection with the Omicron variant among messenger RNA-vaccinated and nonvaccinated individuals in Quebec, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2236670. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.36670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintero AM, Eisner M, Sayegh R, Wright T, Ramilo O, Leber AL, Wang H, Mejias A. 2022. Differences in SARS-CoV-2 clinical manifestations and disease severity in children and adolescents by infecting variant. Emerg Infect Dis 28:2270–2280. doi: 10.3201/eid2811.220577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Z, Huang X, Zhang J, Fu S, Ding D, Tao Z. 2021. Differences in clinical characteristics between Delta variant and wild-type SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:792135. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.792135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie AI, Kadwani O, Saleh D, Baharlo B, Broomhead LR, Randell P, Waheed U, Templeton M, Brown E, Stümpfle R, Patel P, Brett SJ, Soni S. 2022. Clinical and survival differences during separate COVID-19 surges: investigating the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant in critical care patients. PLoS One 17:e0269244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirabara SM, Serdan TDA, Gorjao R, Masi LN, Pithon-Curi TC, Covas DT, Curi R, Durigon EL. 2021. SARS-COV-2 variants: differences and potential of immune evasion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:781429. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.781429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menni C, Valdes AM, Polidori L, Antonelli M, Penamakuri S, Nogal A, Louca P, May A, Figueiredo JC, Hu C, Molteni E, Canas L, Österdahl MF, Modat M, Sudre CH, Fox B, Hammers A, Wolf J, Capdevila J, Chan AT, David SP, Steves CJ, Ourselin S, Spector TD. 2022. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet 399:1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00327-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, Vanstapel A, Werlein C, Stark H, Tzankov A, Li WW, Li VW, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk D. 2020. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osterrieder N, Bertzbach LD, Dietert K, Abdelgawad A, Vladimirova D, Kunec D, Hoffmann D, Beer M, Gruber AD, Trimpert J. 2020. Age-dependent progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Syrian hamsters. Viruses 12:779. doi: 10.3390/v12070779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allnoch L, Beythien G, Leitzen E, Becker K, Kaup F-J, Stanelle-Bertram S, Schaumburg B, Mounogou KN, Beck S, Zickler M, Herder V, Gabriel G, Baumgärtner W. 2021. Vascular inflammation is associated with loss of aquaporin 1 expression on endothelial cells and increased fluid leakage in SARS-CoV-2 infected Golden Syrian hamsters. Viruses 13:639. doi: 10.3390/v13040639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruber AD, Osterrieder N, Bertzbach LD, Vladimirova D, Greuel S, Ihlow J, Horst D, Trimpert J, Dietert K. 2020. Standardization of reporting criteria for lung pathology in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters: what matters? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 63:856–859. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0280LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruber AD, Firsching TC, Trimpert J, Dietert K. 2022. Hamster models of COVID-19 pneumonia reviewed: how human can they be? Vet Pathol 59:528–545. doi: 10.1177/03009858211057197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhakal S, Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Zhou R, Creisher PS, Villano JS, Littlefield K, Ruelas CJ, Marinho P, Jedlicka AE, Ordonez AA, Bahr M, Majewska N, Betenbaugh MJ, Flavahan K, Mueller ARL, Looney MM, Quijada D, Mota F, Beck SE, Brockhurst J, Braxton AM, Castell N, Stover M, D’Alessio FR, Metcalf PK, Karakousis PC, Mankowski JL, Pekosz A, Jain SK, Klein SL, Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Hamster Study Group . 2021. Sex differences in lung imaging and SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in a COVID-19 Golden Syrian hamster model. mBio 12:e0097421. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00974-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aleem A, Akbar Samad AB, Slenker AK. 2022. Emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 and novel therapeutics against coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenke K, Meade-White K, Letko M, Clancy C, Hansen F, Liu Y, Okumura A, Tang-Huau T-L, Li R, Saturday G, Feldmann F, Scott D, Wang Z, Munster V, Jarvis MA, Feldmann H. 2020. Defining the Syrian hamster as a highly susceptible preclinical model for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:2673–2684. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1858177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan JF-W, Zhang AJ, Yuan S, Poon VK-M, Chan CC-S, Lee AC-Y, Chan W-M, Fan Z, Tsoi H-W, Wen L, Liang R, Cao J, Chen Y, Tang K, Luo C, Cai J-P, Kok K-H, Chu H, Chan K-H, Sridhar S, Chen Z, Chen H, To KK-W, Yuen K-Y. 2020. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a Golden Syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin Infect Dis 71:2428–2446. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braxton AM, Creisher PS, Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Mulka KR, Dhakal S, Ordonez AA, Beck SE, Jain SK, Villano JS. 2021. Hamsters as a model of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. Comp Med 71:398–410. doi: 10.30802/AALAS-CM-21-000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Zhang AJ, Poon VK-M, Chan CC-S, Lee AC-Y, Fan Z, Li C, Liang R, Cao J, Tang K, Luo C, Cheng VC-C, Cai J-P, Chu H, Chan K-H, To KK-W, Sridhar S, Yuen K-Y. 2020. Surgical mask partition reduces the risk of noncontact transmission in a Golden Syrian hamster model for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis 71:2139–2149. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sia SF, Yan L-M, Chin AWH, Fung K, Choy K-T, Wong AYL, Kaewpreedee P, Perera RAPM, Poon LLM, Nicholls JM, Peiris M, Yen H-L. 2020. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature 583:834–838. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leung K, Shum MH, Leung GM, Lam TT, Wu JT. 2021. Early transmissibility assessment of the N501Y mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2 in the United Kingdom, October to November 2020. Euro Surveill 26:2002106. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.26.1.2002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Zhang T, Fang Y, Liu J, Ye Q, Ding L. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 spike L452R mutation increases Omicron variant fusogenicity and infectivity as well as host glycolysis. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:76. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00941-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki R, Yamasoba D, Kimura I, Wang L, Kishimoto M, Ito J, Morioka Y, Nao N, Nasser H, Uriu K, Kosugi Y, Tsuda M, Orba Y, Sasaki M, Shimizu R, Kawabata R, Yoshimatsu K, Asakura H, Nagashima M, Sadamasu K, Yoshimura K, Sawa H, Ikeda T, Irie T, Matsuno K, Tanaka S, Fukuhara T, Sato K, Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium . 2022. Attenuated fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nature 603:700–705. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04462-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araf Y, Akter F, Tang Y-D, Fatemi R, Parvez MSA, Zheng C, Hossain MG. 2022. Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID-19 vaccines. J Med Virol 94:1825–1832. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ledford H. 2021. How severe are Omicron infections? Nature 600:577–578. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halfmann PJ, Iida S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Maemura T, Kiso M, Scheaffer SM, Darling TL, Joshi A, Loeber S, Singh G, Foster SL, Ying B, Case JB, Chong Z, Whitener B, Moliva J, Floyd K, Ujie M, Nakajima N, Ito M, Wright R, Uraki R, Warang P, Gagne M, Li R, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Liu Y, Larson D, Osorio JE, Hernandez-Ortiz JP, Henry AR, Ciuoderis K, Florek KR, Patel M, Odle A, Wong L-YR, Bateman AC, Wang Z, Edara V-V, Chong Z, Franks J, Jeevan T, Fabrizio T, DeBeauchamp J, Kercher L, Seiler P, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Sordillo EM, Chang LA, van Bakel H, Consortium Mount Sinai Pathogen Surveillance (PSP) study group, et al. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature 603:687–692. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04441-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y-N, Zhang Z-R, Zhang H-Q, Li N, Zhang Q-Y, Li X-D, Deng C-L, Deng F, Shen S, Zhu B, Zhang B. 2022. Different pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in wild-type laboratory mice and hamsters. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:62. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00930-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meo SA, Meo AS, Al-Jassir FF, Klonoff DC. 2021. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 new variant: global prevalence and biological and clinical characteristics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25:8012–8018. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohandas S, Yadav PD, Sapkal G, Shete AM, Deshpande G, Nyayanit DA, Patil D, Kadam M, Kumar A, Mote C, Jain R. 2022. Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (R346K) variant in Syrian hamsters and its cross-neutralization with different variants of concern. EBioMedicine 79:103997. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anker MS, Landmesser U, Haehling S, Butler J, Coats AJ, Anker SD. 2021. Weight loss, malnutrition, and cachexia in COVID-19: facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12:9–13. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Filippo L, De Lorenzo R, D'Amico M, Sofia V, Roveri L, Mele R, Saibene A, Rovere-Querini P, Conte C. 2021. COVID-19 is associated with clinically significant weight loss and risk of malnutrition, independent of hospitalisation: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 40:2420–2426. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reyna RA, Kishimoto-Urata M, Urata S, Makishima T, Paessler S, Maruyama J. 2022. Recovery of anosmia in hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2 is correlated with repair of the olfactory epithelium. Sci Rep 12:628. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Melo GD, Lazarini F, Levallois S, Hautefort C, Michel V, Larrous F, Verillaud B, Aparicio C, Wagner S, Gheusi G, Kergoat L, Kornobis E, Donati F, Cokelaer T, Hervochon R, Madec Y, Roze E, Salmon D, Bourhy H, Lecuit M, Lledo P-M. 2021. COVID-19-related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Sci Transl Med 13:eabf8396. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhai C, Wang M, Chung H-J, Hassan M, Lee S, Kim H-J, Hong S-T. 2021. Roborovski hamster (Phodopus roborovskii) strain SH101 as a systemic infection model of SARS-CoV-2. Virulence 12:2430–2442. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1972201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frere JJ, Serafini RA, Pryce KD, Zazhytska M, Oishi K, Golynker I, Panis M, Zimering J, Horiuchi S, Hoagland DA, Møller R, Ruiz A, Kodra A, Overdevest JB, Canoll PD, Borczuk AC, Chandar V, Bram Y, Schwartz R, Lomvardas S, Zachariou V, tenOever BR. 2022. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic perturbations after recovery. Sci Transl Med 14:eabq3059. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alwani M, Yassin A, Al-Zoubi RM, Aboumarzouk OM, Nettleship J, Kelly D, Al-Qudimat AR, Shabsigh R. 2021. Sex-based differences in severity and mortality in COVID-19. Rev Med Virol 31:e2223. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fortunato F, Martinelli D, Lo Caputo S, Santantonio T, Dattoli V, Lopalco PL, Prato R. 2021. Sex and gender differences in COVID-19: an Italian local register-based study. BMJ Open 11:e051506. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen J, Nørgaard SK, Lanzieri G, Vestergaard LS, Moelbak K. 2021. Sex-differences in COVID-19 associated excess mortality is not exceptional for the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 11:20815. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2023.2187081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffin BD, Warner BM, Chan M, Valcourt E, Tailor N, Banadyga L, Leung A, He S, Boese AS, Audet J, Cao W, Moffat E, Garnett L, Tierney K, Tran KN, Albietz A, Manguiat K, Soule G, Bello A, Vendramelli R, Lin J, Deschambault Y, Zhu W, Wood H, Mubareka S, Safronetz D, Strong JE, Embury-Hyatt C, Kobasa D. 2021. Host parameters and mode of infection influence outcome in SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters. iScience 24:103530. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michita RT, Mysorekar IU. 2021. Golden Syrian hamsters as a model for revisiting the role of biological sex differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection. mBio 12:e01848-21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01848-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan L, Zhu H, Zhou M, Ma J, Chen R, Chen Y, Chen L, Wu K, Cai M, Hong J, Li L, Liu C, Yu H, Zhang Y, Wang J, Zhang T, Ge S, Zhang J, Yuan Q, Chen Y, Tang Q, Chen H, Cheng T, Guan Y, Xia N. 2021. Gender associates with both susceptibility to infection and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in Syrian hamster. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6:136. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kreye J, Reincke SM, Kornau H-C, Sánchez-Sendin E, Corman VM, Liu H, Yuan M, Wu NC, Zhu X, Lee C-CD, Trimpert J, Höltje M, Dietert K, Stöffler L, von Wardenburg N, van Hoof S, Homeyer MA, Hoffmann J, Abdelgawad A, Gruber AD, Bertzbach LD, Vladimirova D, Li LY, Barthel PC, Skriner K, Hocke AC, Hippenstiel S, Witzenrath M, Suttorp N, Kurth F, Franke C, Endres M, Schmitz D, Jeworowski LM, Richter A, Schmidt ML, Schwarz T, Müller MA, Drosten C, Wendisch D, Sander LE, Osterrieder N, Wilson IA, Prüss H. 2020. A therapeutic non-self-reactive SARS-CoV-2 antibody protects from lung pathology in a COVID-19 hamster model. Cell 183:1058–1069.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers TF, Zhao F, Huang D, Beutler N, Burns A, He W-T, Limbo O, Smith C, Song G, Woehl J, Yang L, Abbott RK, Callaghan S, Garcia E, Hurtado J, Parren M, Peng L, Ramirez S, Ricketts J, Ricciardi MJ, Rawlings SA, Wu NC, Yuan M, Smith DM, Nemazee D, Teijaro JR, Voss JE, Wilson IA, Andrabi R, Briney B, Landais E, Sok D, Jardine JG, Burton DR. 2020. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science 369:956–963. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tostanoski LH, Wegmann F, Martinot AJ, Loos C, McMahan K, Mercado NB, Yu J, Chan CN, Bondoc S, Starke CE, Nekorchuk M, Busman-Sahay K, Piedra-Mora C, Wrijil LM, Ducat S, Custers J, Atyeo C, Fischinger S, Burke JS, Feldman J, Hauser BM, Caradonna TM, Bondzie EA, Dagotto G, Gebre MS, Jacob-Dolan C, Lin Z, Mahrokhian SH, Nampanya F, Nityanandam R, Pessaint L, Porto M, Ali V, Benetiene D, Tevi K, Andersen H, Lewis MG, Schmidt AG, Lauffenburger DA, Alter G, Estes JD, Schuitemaker H, Zahn R, Barouch DH. 2020. Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 severe clinical disease in hamsters. Nat Med 26:1694–1700. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Purohit D, Ahirwar AK, Sakarde A, Asia P, Gopal N. 2021. COVID-19 and lung pathologies. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 42:435–443. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2020-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schalekamp S, Bleeker-Rovers CP, Beenen LFM, Quarles van Ufford HME, Gietema HA, Stöger JL, Harris V, Reijers MHE, Rahamat-Langendoen J, Korevaar DA, Smits LP, Korteweg C, van Rees Vellinga TFD, Vermaat M, Stassen PM, Scheper H, Wijnakker R, Borm FJ, Dofferhoff ASM, Prokop M. 2021. Chest CT in the emergency department for diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia: Dutch experience. Radiology 298:E98–E106. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020203465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, Kirwan P, Saei A, Atti A, Wellington E, Khawam J, Munro K, Cole M, Tranquillini C, Taylor-Kerr A, Hettiarachchi N, Calbraith D, Sajedi N, Milligan I, Themistocleous Y, Corrigan D, Cromey L, Price L, Stewart S, de Lacy E, Norman C, Linley E, Otter AD, Semper A, Hewson J, D’Arcangelo S, Chand M, Brown CS, Brooks T, Islam J, Charlett A, Hopkins S, SIREN Study Group . 2022. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med 386:1207–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2118691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallais F, Gantner P, Bruel T, Velay A, Planas D, Wendling M-J, Bayer S, Solis M, Laugel E, Reix N, Schneider A, Glady L, Panaget B, Collongues N, Partisani M, Lessinger J-M, Fontanet A, Rey D, Hansmann Y, Kling-Pillitteri L, Schwartz O, De Sèze J, Meyer N, Gonzalez M, Schmidt-Mutter C, Fafi-Kremer S. 2021. Evolution of antibody responses up to 13 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of reinfection. EBioMedicine 71:103561. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murillo-Zamora E, Trujillo X, Huerta M, Ríos-Silva M, Guzmán-Esquivel J, Benites-Godínez V, Ochoa-Castro MR, Guzmán-Solórzano JA, Mendoza-Cano O. 2022. COVID-19 vaccines provide better protection against related pneumonia than previous symptomatic infection. Int J Infect Dis 120:142–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu K, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K. 2020. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect 80:e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Syan SK, Gohari MR, Levitt EE, Belisario K, Gillard J, DeJesus J, MacKillop J. 2021. COVID-19 vaccine perceptions and differences by sex, age, and education in 1,367 community adults in Ontario. Front Public Health 9:719665. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.719665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, Mao B, Liang S, Yang J-W, Lu H-W, Chai Y-H, Wang L, Zhang L, Li Q-H, Zhao L, He Y, Gu X-L, Ji X-B, Li L, Jie Z-J, Li Q, Li X-Y, Lu H-Z, Zhang W-H, Song Y-L, Qu J-M, Xu J-F, Shanghai Clinical Treatment Experts Group for COVID-19 . 2020. Association between age and clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19. Eur Respir J 55:2001112. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01112-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oishi K, Horiuchi S, Frere J, Schwartz RE, tenOever BR. 2022. A diminished immune response underlies age-related SARS-CoV-2 pathologies. Cell Rep 39:111002. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ye Z-W, Yuan S, Chan JF-W, Zhang AJ, Yu C-Y, Ong CP, Yang D, Chan CC-Y, Tang K, Cao J, Poon VK-M, Chan CC-S, Cai J-P, Chu H, Yuen K-Y, Jin D-Y. 2021. Beneficial effect of combinational methylprednisolone and remdesivir in hamster model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Microbes Infect 10:291–304. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1885998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J, Budylowski P, Samson R, Griffin BD, Babuadze G, Rathod B, Colwill K, Abioye JA, Schwartz JA, Law R, Yip L, Ahn SK, Chau S, Naghibosadat M, Arita Y, Hu Q, Yue FY, Banerjee A, Hardy WR, Mossman K, Mubareka S, Kozak RA, Pollanen MS, Martin Orozco N, Gingras A-C, Marcusson EG, Ostrowski MA. 2022. Preclinical evaluation of a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine PTX-COVID19-B. Sci Adv 8:eabj9815. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maruggi G, Mallett CP, Westerbeck JW, Chen T, Lofano G, Friedrich K, Qu L, Sun JT, McAuliffe J, Kanitkar A, Arrildt KT, Wang K-F, McBee I, McCoy D, Terry R, Rowles A, Abrahim MA, Ringenberg MA, Gains MJ, Spickler C, Xie X, Zou J, Shi P-Y, Dutt T, Henao-Tamayo M, Ragan I, Bowen RA, Johnson R, Nuti S, Luisi K, Ulmer JB, Steff A-M, Jalah R, Bertholet S, Stokes AH, Yu D. 2022. A self-amplifying mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate induces safe and robust protective immunity in preclinical models. Mol Ther 30:1897–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meyerholz DK, Beck AP. 2020. Histopathologic evaluation and scoring of viral lung infection. Methods Mol Biol 2099:205–220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0211-9_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meyerholz DK, Sieren JC, Beck AP, Flaherty HA. 2018. Approaches to evaluate lung inflammation in translational research. Vet Pathol 55:42–52. doi: 10.1177/0300985817726117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Percentage of weight change over 7 days following variant naive infection and variant reinfection. (A to H) Naive hamsters consistently lost weight after infection, while reinfected hamsters showed little to no initial weight loss followed by weight gain over 7 dpi. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 13.6 MB (13.9MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Histopathology of the lungs, Omicron variant. (A and B) Two days postinfection. (A) Suppurative bronchitis (arrowheads), with bronchial epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis; (B) intra-alveolar organized fibrin (arrows) and increased inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrowhead) within the alveolar septa and spaces. (C and D) Four days postinfection. (C) Vasculitis/vascular endothelialitis characterized by subendothelial aggregates of neutrophils and mononuclear cells (arrows), as well as perivascular accumulation of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (*); (D) organized fibrin (*) within the alveoli along with increased numbers of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (arrowheads). (E and F) Seven days postinfection. (E) Low magnification indicating the extent of the consolidation (*) of the alveoli; (F) higher magnification indicating type II pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrow), inflammatory cells, including neutrophils (arrowhead), macrophages, and fewer lymphocytes, and multinucleated epithelial cells (squiggle arrow). The scale bar represents 100 μm in all images. Download FIG S1, TIF file, 6.9 MB (7.1MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Histopathologic scoring system used blind by a board-certified veterinary pathologist to analyze hamster lung tissue. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.03 MB (35.2KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Results of multiple comparisons and one-way ANOVA of viral titer at 2, 4, and 7 dpi for naive infected animals’ lung, trachea, and nasal turbinates. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.05 MB (48.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2023 Plunkard et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.