Abstract

The endothelin ETB receptor is a promiscuous G-protein coupled receptor that is activated by vasoactive peptide endothelins. ETB signaling induces reactive astrocytes in the brain and vasorelaxation in vascular smooth muscle. Consequently, ETB agonists are expected to be drugs for neuroprotection and improved anti-tumor drug delivery. Here, we report the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the endothelin-1-ETB-Gi complex at 2.8 Å resolution, with complex assembly stabilized by a newly established method. Comparisons with the inactive ETB receptor structures revealed how endothelin-1 activates the ETB receptor. The NPxxY motif, essential for G-protein activation, is not conserved in ETB, resulting in a unique structural change upon G-protein activation. Compared with other GPCR-G-protein complexes, ETB binds Gi in the shallowest position, further expanding the diversity of G-protein binding modes. This structural information will facilitate the elucidation of G-protein activation and the rational design of ETB agonists.

Research organism: Human

Introduction

Endothelins are 21-amino-acid vasoconstricting peptides produced primarily in the endothelium Yanagisawa et al., 1988 and play a key role in vascular homeostasis. Among the three endothelin isopeptides (ET-1–3), ET-1 was first discovered as a potent vasoconstrictor Maguire and Davenport, 2014; Davenport et al., 2016. ET-1 transmits signals through two receptor subtypes, the ETA and ETB receptors, which belong to the class A G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Arai et al., 1990; Sakurai et al., 1990. The endothelin receptors exert regulatory control over cellular processes important for growth, survival, invasion, and angiogenesis Haryono et al., 2022; Barton and Yanagisawa, 2019. In the vascular system, the ETA receptor serves as the primary mediator of vasoconstriction, and its irreversible binding to ET-1 leads to prolonged vasoconstriction. By contrast, the ETB receptor primarily induces vasorelaxation via the nitric oxide-mediated pathway, and it acts as a clearance receptor that removes circulating ET-1 via the lysosomal pathway Bremnes et al., 2000. The ETB receptor is known to be a promiscuous GPCR, capable of activating multiple types of G-proteins Inoue et al., 2019; Doi et al., 1999. In vascular smooth muscle, it induces nitric oxide-mediated vasorelaxation via Gq signaling. Furthermore, the astrocytic ETB receptor-mediated Gi signal reduces intercellular communication through gap junctions Tencé et al., 2012, and the Rho signal in astrocytes leads to cytoskeletal reorganization and cell-adhesion-dependent proliferation Koyama and Baba, 1996, promoting the induction of reactive astrocytes and neuroprotection Koyama, 2021.

Drug development targeting the endothelin receptors has primarily focused on antagonists owing to the vasodilation effect Haryono et al., 2022; Barton and Yanagisawa, 2019. Bosentan, the first non-peptide antagonist for ETA and ETB, is currently in clinical use for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Moreover, ETA-selective antagonists are used as therapeutic agents with fewer side effects. Notably, endothelin-1 acts primarily through the ETA receptor and is implicated in the neoplastic growth of multiple tumor types. Thus, endothelin receptor antagonists such as atrasentan and zibotentan have demonstrated potential anticancer activity in preclinical studies Rosanò et al., 2013. The development of ETB agonists is also underway, as they provide therapeutic benefits such as vasodilation and neuroprotection Davenport et al., 2016; Koyama, 2021. IRL1620, a truncated analog of ET-1, is the smallest ETB-selective agonist that has been shown to selectively and transiently increase tumor blood flow Gulati et al., 2012, making it a potential adjuvant cancer therapy for enhancing the delivery of anti-tumor drugs and acute ischemic stroke Ranjan and Gulati, 2022. However, IRL1620 is a linear peptide with exposed N- and C-termini and thus has problems in terms of pharmacokinetics and drug delivery. Currently, small-molecule ETB-selective agonists have not been developed, hindering drug development targeting the ETB receptor.

To date, eight crystal structures of the human ETB receptor have been reported, elucidating the structure-activity relationships of the peptide agonists and small-molecule clinical antagonists Shihoya et al., 2016; Nagiri et al., 2019; Izume et al., 2020; Shihoya et al., 2018; Shihoya et al., 2017. Nevertheless, the detailed activation mechanism has remained elusive due to the crystallization constructs containing T4 lysozyme in the intracellular loop (ICL) 3 and thermostabilizing mutations Okuta et al., 2016; Nakai et al., 2022 that stabilize the inactive state. Moreover, the conserved N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motif (superscripts indicate Ballesteros–Weinstein numbers Ballesteros and Weinstein, 1995) essential for G-protein activation Venkatakrishnan et al., 2013 is altered to N7.49P7.50xxL7.53Y7.54 in the wild-type ETB receptor. Thus, little is known about ETB-mediated G-protein activation. Here, we report the 2.8 Å-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the human ETB-Gi signaling complex bound to ET-1, revealing the unique mechanisms of receptor activation and G-protein coupling.

Results

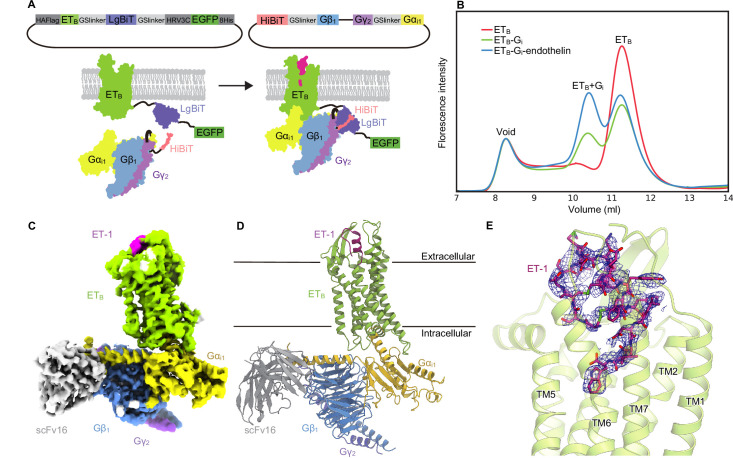

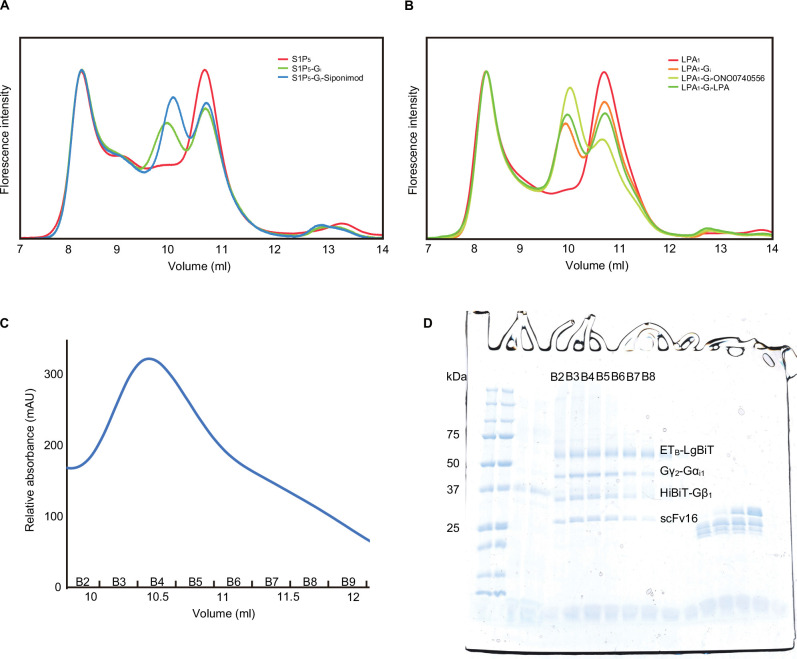

Development of fusion-G system for structural determination

For the cryo-EM analysis, we initially used the thermostabilized receptor ETB-Y5, which contains five thermostabilizing mutations Okuta et al., 2016. However, the purified ETB-Y5 could not form a stable complex with the Gi trimer because the mutations were known to stabilize the inactive conformation. Thus, we chose to use the wild-type ETB for the structural study. To purify the stable GPCR-G-protein complex, we developed a ‘Fusion-G system’ (Figure 1A) by combining two complex stabilization techniques. One of these techniques was the NanoBiT tethering strategy Duan et al., 2020; Dixon et al., 2016, where the large part of NanoBiT (LgBiT) was fused to the C-terminus of the receptor, and a modified 13-amino acid peptide of NanoBiT (HiBiT) was fused to the C-terminus of Gβ via the GS linker. HiBit has a potent affinity for LgBiT (Kd = 700 pM) and thus provides an additional linkage to stabilize the interface between H8 of the receptor and the Gβ subunit of the G-protein. This strategy has been successfully used to solve several GPCR/G-protein complex structures Duan et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2021. The other technique was a 3-in-1 vector for G-protein expression, in which the Gα subunit was fused to the C-terminus of the Gγ subunit (Kim et al., 2020; Nureki et al., 2022; Figure 1A). The resulting pFastBac-Dual vector could produce a virus that expressed the G-protein trimer. Moreover, the protease-cleavable green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was connected to the C-terminus of the receptor-LgBiT fusion, allowing analysis of complex formation by fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography (FSEC) Hattori et al., 2012. Using this system, we confirmed the complex formation of LPA1 and S1P5 with Gi (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A, B), whose structures in complex with the Gi trimer had previously been reported Akasaka et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022a.

Figure 1. Overall structure of the ET-1-ETB-Gi signaling complex.

(A) Schematic representations of the fusion-G system. (B) Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography (FSEC) analysis of complex formation by the ETB receptor. The fluorescence intensities are adjusted to equalize those corresponding to the void volumes. (C) Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) map with variously colored densities. (D) Structure of the complex determined after refinement in the cryo-EM map, shown as a ribbon representation. (E) Density focused on ET-1.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Fusion-G system.

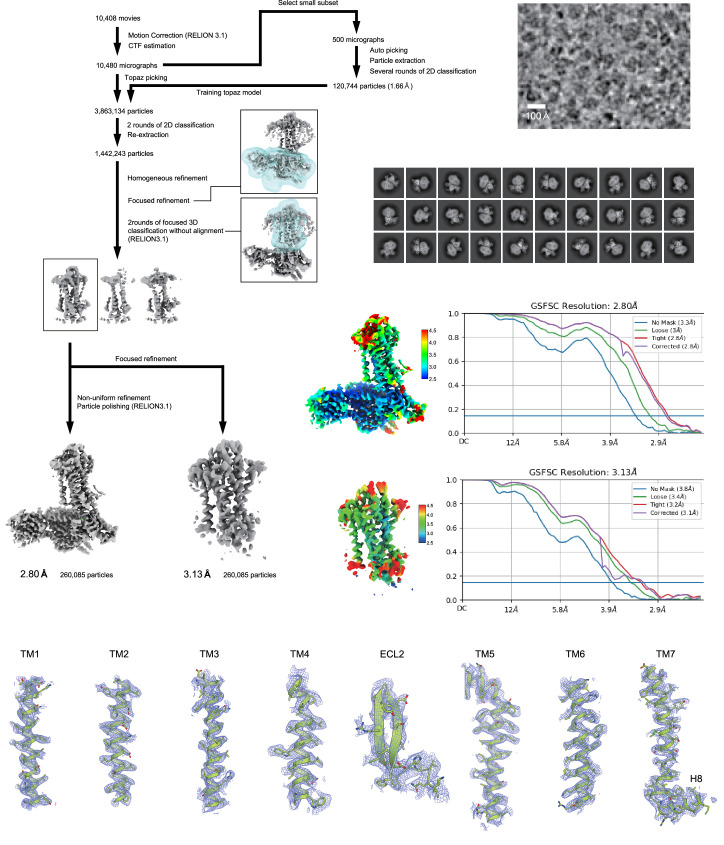

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) workflow, maps, and model quality.

We cloned the full-length human ETB receptor into the LgBiT vector. Using the fusion-G-system, we confirmed the formation of the ETB-Gi complex (Figure 1B). The co-expressed cells from a 300 ml culture were solubilized and purified by Flag affinity chromatography. After incubation with scFv16, the complex was purified by size exclusion chromatography (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C, D). The structure of the purified complex was determined by single-particle cryo-EM analysis with an overall resolution of 2.8 Å (Figure 1C and D, Figure 1—figure supplement 2, Table 1). No density corresponding to NanoBiT was observed in the 2D class averages and reconstructed 3D density map, as in the previous structural studies using the NanoBiT tethering strategy Duan et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022b. We refined with a mask on the receptor and obtained the receptor structure with a nominal resolution of 3.1 Å (Figure 1—figure supplement 2, Table 1). The agonist ET-1 is well resolved (Figure 1E).

Table 1. Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics.

| Data collection | ETB-Gi (overall) | ETB-Gi (receptor focused) |

|---|---|---|

| Microscope | Titan Krios (Thermo Fisher Scientific) | |

| Voltage (keV) | 300 | |

| Electron exposure (e-/Å2) | 49.965 | |

| Detector | Gatan K3 summit camera (Gatan) | |

| Magnification | ×105,000 | |

| Defocus range (μm) | –0.8–1.6 | |

| Pixel size (Å/pix) | 0.83 | |

| Number of movies | 10,408 | |

| Symmetry | C1 | |

| Picked particles | 3,863,134 | |

| Final particles | 260,085 | |

| Map resolution (Å) | 2.80 | 3.13 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | |

| Model refinement | ||

| Atoms | 9,367 | 2,523 |

| R.m.s. deviations for ideal | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.56 | 0.52 |

| Validation | ||

| Clashscore | 11.68 | 7.7 |

| Rotamers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 96.55 | 98.04 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.19 | 1.96 |

| Outlier (%) | 0.26 | 0.00 |

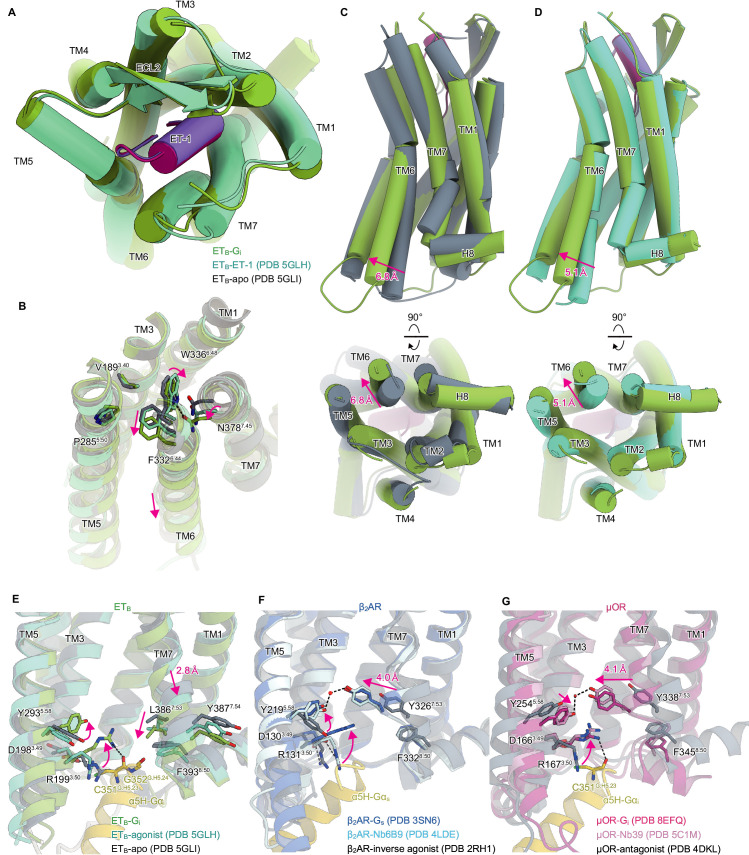

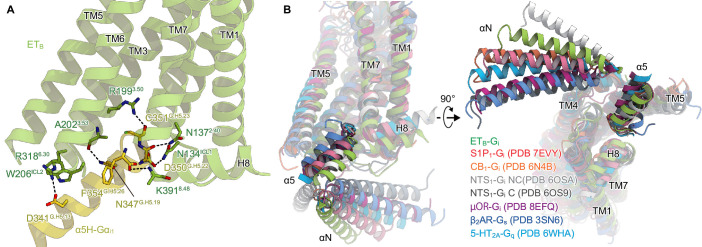

Receptor conformational changes upon Gi activation

The extracellular half of the receptor superimposes well on the ET-1-bound crystal structure, and ET-1 interacts closely with the receptor in a similar manner (Figure 2A). Previous crystallographic analyses have suggested that the ET-1 binding leads to the downward movement of N3787.45 and W3366.48 in the C6.47W6.48xP6.50 motif at the bottom of the ligand binding pocket, which ultimately results in the downward rotation of F3326.44 in the P5.50I3.40F6.44 motif, and leading to the intracellular opening Shihoya et al., 2016; Nagiri et al., 2019; Izume et al., 2020; Shihoya et al., 2018; Shihoya et al., 2017. The downward movement of the residues is larger in the ETB-Gi complex than in the ET-1-bound crystal structure (Figure 2B), which consequently results in the outward displacement of the intracellular portion of the transmembrane helix (TM) 6 by 6.8 Å as compared to the apo state (Figure 2C), and by 5.1 Å as compared to the ET-1-bound crystal structure (Figure 2D). The degree of TM6 opening observed is less than those of other Gi-coupled receptors (e.g. μOR: 10 Å, CB1: 11.6 Å, and S1P1: 9 Å) Yuan et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022; Hua et al., 2020.

Figure 2. Structural changes upon G-protein activation.

(A) Superimposition of the ET-1-bound receptor in the crystal and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures. (B) Superimposition of the ETB structures, focused on the receptor core. (C, D) Superimpositions of the Gi-complexed ETB structure with the ET-1-bound crystal structure (C) and apo structure (D). (E-G) D3.49R3.50Y3.51 and N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motifs in ETB (E), β2AR (F), and μOR (G). Black dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

In most class A GPCRs, the highly conserved D3.49R3.50Y3.51 and N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motifs on the intracellular side play an essential role in G-protein coupling Venkatakrishnan et al., 2013. The D3.49R3.50Y3.51 motif is conserved in the ETB receptor. Upon receptor activation, the ionic lock between D1983.49 and R1993.50 is broken, and R1993.50 becomes oriented towards the intracellular cavity (Figure 2E), similar to other GPCRs Zhuang et al., 2022; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Ring et al., 2013; Cherezov et al., 2007; Manglik et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2015 (Figure 2F and G). In contrast, the N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motif is altered to N7.49P7.50xxL7.53Y7.54, where Y7.53 is replaced by L3867.53. In most class A GPCRs, receptor activation disrupts the stacking interaction between Y7.53 and F8.50 Carpenter and Tate, 2017. Y7.53 moves inwardly and forms a water-mediated hydrogen bond with the highly conserved Y5.58 (Figure 2F and G; Ring et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2015; Deupi et al., 2012). The mutations of the tyrosines significantly reduce G-protein activation Goncalves et al., 2010; Flock et al., 2015, indicating that the interaction between Y5.58-and Y7.53 stabilizes the active conformation of the receptor. Along with the motion, the intracellular portion of TM7 is displaced by approximately 4 Å. As L3867.53 is a hydrophobic residue, it cannot form a polar interaction, and hence in the ETB-Gi complex, TM7 is not displaced inwardly (Figure 2C). Nonetheless, the stacking interaction with F3938.50 is disrupted similarly. Moreover, the intracellular portion of TM7 is displaced downward by 2.8 Å. As expected, Y7.54 is directed towards the membrane plane, and its rotamer does not change upon receptor activation (Figure 2E). The substitution of Y7.53 with L3867.53 affects the movement of TM7 upon receptor activation, thereby distinguishing it from other GPCRs.

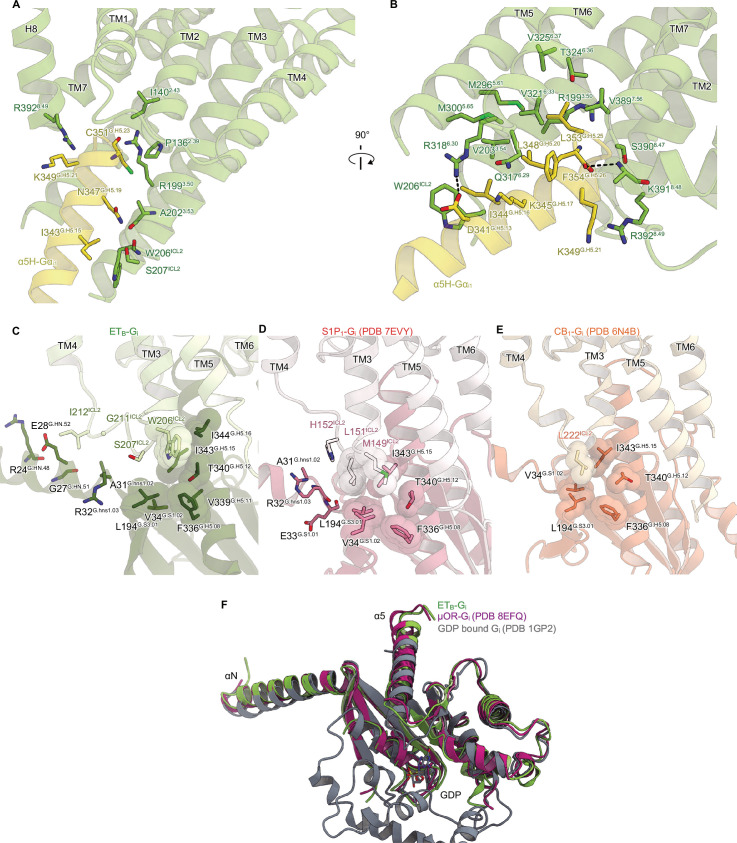

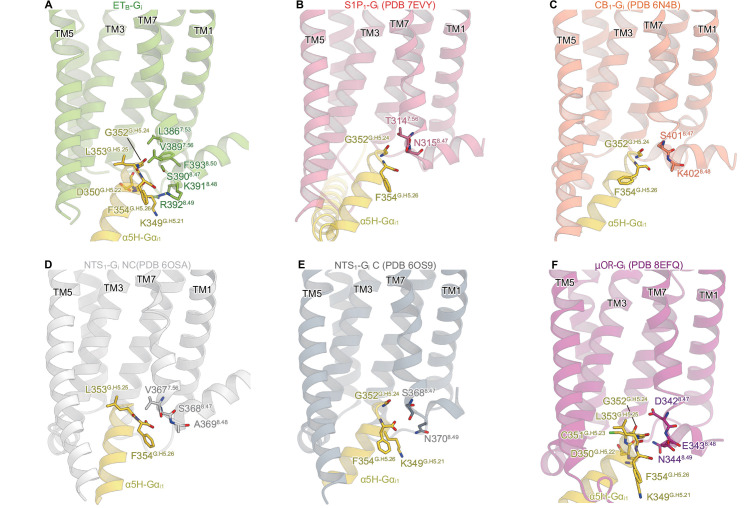

Shallow Gi coupling

These conformational changes create an intracellular cavity for G-protein recognition (Figure 3A, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). The cavity closely interacts with the C-terminal α5-helix of Gαi, the primary determinant for G-protein coupling. In particular, R1993.50 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of C351G.H5.23 (superscript indicates the common Gα numbering [CGN] system Flock et al., 2015), which is commonly observed in other GPCR-Gi complexes Yuan et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022; Hua et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2019. Additionally, the C-terminal carboxylate of α5-helix forms electrostatic interactions with the backbone nitrogen atom of K3918.48. There are several other hydrogen-bonding interactions between the α5-helix and the receptor (Figure 3A). On ICL2, W206ICL2 fits into a hydrophobic pocket formed by L194G.S3.01, F336G.H5.08, T340G.H5.12, I343G.H5.15, and I344G.H5.16 in the Gαi subunit. Moreover, ICL2 forms extensive van der Waals interactions with the αN (Figure 3—figure supplement 1), which are not observed in other GPCR-Gi complexes (Figure 3—figure supplement 1; Yuan et al., 2021; Hua et al., 2020).

Figure 3. Comparison of the Gi binding modes.

(A) Hydrogen-bonding interactions between ETB and the α5-helix, indicated by black dashed lines. (B) Comparison of the Gα positions in the GPCR-G-protein complexes. The structures are superimposed on the receptor structure of the NTS1-C state.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Detailed ETB-Gi interface.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Comparison of the interactions between the α5-helix and TM7-H8.

Upon receptor activation, the intracellular portion of TM7 moves downwards, resulting in the unique Gi coupling mode. Along with this motion, L3867.53 directly forms a hydrophobic contact with G352G.H5.24. Moreover, TM7 and H8 extensively interact with the α5-helix (Figure 3—figure supplement 2), which is not observed in other GPCR-Gi complexes (Figure 3—figure supplement 2; Yuan et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022; Hua et al., 2020; Kato et al., 2019). These structural features enable the α5-helix of ETB-Gi to be located in the shallowest position relative to the receptor among the Gs, Gi, and Gq-coupled GPCR structures (Kim et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022; Hua et al., 2020; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Kato et al., 2019; Figure 3B). Nevertheless, the Gαi structure adopts a nucleic acid-free state, similar to the μOR-Gi complex (Figure 3—figure supplement 1; Zhuang et al., 2022; Wall et al., 1995). The interacting surface area between the receptor and Gαi subunit is 1,196 Å2, which is comparable to those in other GPCR-Gi complexes (µOR : 1,260 Å2. NTS1 : 1,197 Å2. and S1P1: 1,376 Å2. Yuan et al., 2021; Zhuang et al., 2022; Kato et al., 2019). As described above, ICL2 and TM7 extensively interact with the αN and α5 helix of the Gαi subunit, respectively. These interactions are uniquely observed in the ETB-Gi complex and can compensate for the shallow binding of Gi.

Discussion

In this study, we established the Fusion-G system, which facilitates the efficient expression and purification of the GPCR-G-protein complex. Additionally, the ability to monitor the fluorescence of GFP fused in the C-terminus of the receptor makes it easier to optimize the expression and purification conditions. The tethering strategy only increases the proportion of the complex by constantly placing the G-protein around the receptor rather than tightly anchoring the complex, suggesting that the fusion-G-system has minimal effect on the complex structure. It should be noted that the potential artifacts resulting from the tethering strategy cannot be entirely ruled out. The hybrid approach we have developed, combining NanoBiT tethering and FSEC methodology, is an effective option for comprehensive structural analysis of various other membrane protein complexes.

The ETB-Gi structure determined by this strategy filled in the last piece of the puzzle, and our understanding of the mechanism of receptor activation has been significantly deepened. The ligand binding pocket is essentially similar in both the crystal structure of the receptor alone and in the Gi protein complex (Figure 2A). However, the W3366.48 rotamer, which comprises the bottom of the ligand-binding pocket, differs (Figure 2B), thereby leading to the activation of the intracellular side of the receptor (Figure 2C and D). Thus, it may be crucial to choose and evaluate compounds based on the bottom of the ligand pocket in the current ETB-Gi structure (Figure 2B) to develop small molecule ETB agonists for neuroprotection and cancer therapy.

Previous structural analyses have demonstrated that docking the α5-helix to the receptor cavity leads to destabilization of the nucleic acid binding site located at the root of the α5-helix (Figure 3—figure supplement 1; Zhuang et al., 2022; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Su et al., 2020), thus promoting the GDP/GTP exchange reaction. While the binding of Gαs remains mostly indistinguishable in all complexes, the binding of Gαi varies, displaying different Gα rotations in relation to the receptor Okamoto et al., 2021. Nevertheless, the depth of the docking towards the receptor remains constant (Figure 3B). Since the N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motif is not conserved in ETB, TM7 undergoes the downward movement upon the Gi binding, resulting in the shallow position of the α5-helix. Thus, the restrictions of the residues in the α5-helix may be less strict, accounting for the G-protein promiscuity of ETB. Since the other promiscuous GPCRs (e.g. NTS1) preserve the N7.49P7.50xxY7.53 motif, the proposed mechanism for G-protein promiscuity may be unique to ETB. Such information is essential for understanding the mechanism of G-protein activation by GPCRs.

Materials and methods

Key resources table.

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| peptide, recombinant protein | ET-1 | PEPTIDE INSTITUTE, INC. | Cat #, 4198 v |

Ligand for ETB |

| Other | Sf-900 II SFM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat #, 10902088 |

Expression medium for sf9 cells |

| chemical compound, drug | n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside | Calbiochem | CAS number: 69227-93-6 |

Detergents used in purification of ETB-Gi complex |

| chemical compound, drug | Cholesteryl hemisuccinate | Merck Millipore | CAS number: 1510-21-0 |

For purifying ETB-Gi complex |

| peptide, recombinant protein | Apyrase | New England Biolabs | Cat #, M0398 |

Enzyme used for ETB-Gi complex formation |

| Other | Anti-DYKDDDDK G1 Affinity resin | Gen Script | Cat #, L00432 |

Affinity resin for DYKDDDDK tags |

| chemical compound, drug | Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol | Anatrace | CAS number: 1257852-96-2 |

Detergents used in purification of ETB-Gi complex |

| Software, algorithm | EPU | Thermo Fisher Scientific | For Cryo-EM data collection | |

| Software, algorithm | RELION-3.1 | Zivanov et al., 2018 | RRID:SCR_016274 | For Cryo-EM data processing |

| Software, algorithm | cryoSPARC v3.3 | STRUCTURA BIOTECHNOLOGY | RRID:SCR_016501 | For cryo-EM data processing |

| Software, algorithm | Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | RRID:SCR_014222 | For structure model building |

| Software, algorithm | Phenix 1.19–4092 | Afonine et al., 2018 | RRID:SCR_014224 | For structure refinement |

| other | Quantifoil holey carbon grid | Quantifoil | R1.2/1.3, Au, 300 mesh | For cryo-EM specimen preparation |

Constructs

The full-length human ETB gene was subcloned into the pFastBac vector with an HA-signal peptide sequence on its N-terminus and the LgBiT fused to its C-terminus followed by a 3 C protease site and EGFP-His8 tag. A 15 amino sequence of GGSGGGGSGGSSSGG was inserted into both the N-terminal and C-terminal sides of LgBiT. The Flag epitope tag (DYKDDDDK) was introduced between G57 and L66. The native signal peptide was replaced with the haemagglutinin signal peptide. Rat Gβ1 and bovine Gγ2 were subcloned into the pFastBac Dual vector, as described previously Kobayashi et al., 2020. In detail, rat Gβ1 was cloned with a C-terminal HiBiT connected with a 15 amino sequence of GGSGGGGSGGSSSGG. Moreover, human Gαi1 was subcloned into the C-terminus of the bovine Gγ2 with a nine amino sequence GSAGSAGSA linker. The resulting pFastBac dual vector can express the Gi trimer.

Complex formation and FSEC analysis

Bacmid preparation and virus production was performed according to the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus system manual (Gibco, Invitrogen). Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells at a density of 3 × 106 cells/ml were co-infected with baculoviruses encoding receptor and Gi trimer at the ratio of 1:1. For the expression of the receptor alone, the baculovirus encoding receptor was only used. Cells were harvested 48 hr after infection. 1 ml cell pellets were solubilized in 200 μl buffer, containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) (Calbiochem), 0.2% cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) (Merck) and rotated for 1 hr at 4 °C.

For the complex formation with the agonist, cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 10% Glycerol, and homogenized by douncing ~20 times. Apyrase was added to the lysis at a final concentration of 25 mU/ml. Each agonist was added at a final concentration of 10 µM. The homogenate was incubated at room temperature for 1 hr with flipping. Then, DDM and CHS were added to a final concentration of 1% and 0.2%, respectively for 1 hr at 4 °C.

The supernatants were separated from the insoluble material by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 20 min. A fraction of the resulting supernatant (10 μl) was loaded onto a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 column in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.03% DDM, and run at the flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The eluent was detected by a fluorometer with the excitation wavelength (480 nm) and emission wavelength settings (512 nm).

ET-1–ETB–Gi complex formation and purification

For expression, 300 ml of the Sf9 cells at a density of 3 × 106 cells/ml were co-infected with baculovirus encoding the ETB-LgBiT-EGFP and Gi trimer at the ratio of 1:1. Cells were harvested 48 hr after infection. Cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 10% Glycerol, and homogenized by douncing ~30 times. Apyrase was added to the lysis at a final concentration of 25 mU/ml. ET-1 was added at a final concentration of 2 µM. The lysate was incubated at room temperature for 1 hr with flipping. Then, the membrane fraction was collected by ultracentrifugation at 180,000 g for 1 hr. The cell membrane was solubilized in buffer, containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% DDM, 0.2% CHS, 10% glycerol, and 2 μM ET-1 for 1 hr at 4 °C. The supernatant was separated from the insoluble material by ultracentrifugation at 180,000 g for 30 min and then incubated with the Anti-DYKDDDDK G1 resin (Genscript) for 1 hr. The resin was washed with 20 column volumes of wash buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.1% Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) (Anatrace), and 0.01% CHS. The complex was eluted by the wash buffer containing 0.15 mg ml–1 Flag peptide. The eluate was treated with 0.5 mg of HRV-3C protease (homemade) and dialyzed against buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 300 mM NaCl). Then, cleavaged GFP-His8 and HRV-3C protease were removed with Ni+-NTA resin. The flow-through was incubated with the scFv16, prepared as described previously Okamoto et al., 2021. The complex was concentrated and loaded onto a Superdex 200 increase 10/300 column in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% LMNG, 0.001% CHS, and 1 μM agonist. Peak fractions were concentrated to 8 mg/ml.

Cryo-EM grid preparation and data acquisition

The purified complex was applied onto a freshly glow-discharged Quantifoil holey carbon grid (R1.2/1.3, Au, 300 mesh) and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane by using a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI). Cryo-EM data collection was performed on a 300 kV Titan Krios G3i microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a BioQuantum K3 imaging filter (Gatan) and a K3 direct electron detector (Gatan). In total, 10,408 movies were acquired with a calibrated pixel size of 0.83 Å pix−1 and with a defocus range of −0.8 to −1.6 μm, using the EPU software (Thermo Fisher’s single-particle data collection software). Each movie was acquired for 2.3 s and split into 48 frames, resulting in an accumulated exposure of about 49.965 e− Å−2.

All acquired movies in super-resolution mode were binned by 2x and were dose-fractionated and subjected to beam-induced motion correction implemented in RELION 3.1 Zivanov et al., 2018. The contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were estimated using patch CTF estimation in cryoSPARC v3.3 Punjani et al., 2017. Particles were initially picked from a small fraction with the Blob picker and subjected to several rounds of two-dimensional (2D) classification in cryoSPARC. Selected particles were used for training of topaz model Bepler et al., 2019. For the full dataset, 3,863,134 particles were picked and extracted with a pixel size of 3.32 Å, followed by 2D classification to remove carbon edges and ice contaminations. A total of 1,442,243 particles were re-extracted with the pixel size of 1.16 Å and curated by three-dimensional (3D) classification without alignment in RELION. Finally, the 260,085 particles in the best class were reconstructed using non-uniform refinement, resulting in a 2.80 Å overall resolution reconstruction, with the gold standard Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC = 0.143) criteria in cryoSPARC. Moreover, the 3D model was refined with a mask on the receptor. As a result, the local resolution of the receptor portion improved with a nominal resolution of 3.13 Å. The local resolution was estimated by cryoSPARC. The processing strategy is described in Figure 1—figure supplement 2.

Model building and refinement

The quality of the density map was sufficient to build an atomic model. Previously reported high-resolution crystal structure of the ET-3 bound ETB receptor (PDB 6IGK) and cryo-EM MT1-Gi structure (PDB 7DB6) were used as the initial models for the model building of receptor and Gi portions, respectively Shihoya et al., 2018; Okamoto et al., 2021. Initially, the models were fitted into the density map by jiggle fit using COOT Emsley et al., 2010. Then, atomic models were readjusted into the density map using COOT and refined using phenix.real_space_refine (v1.19) with the secondary structure restraints using phenix.secondary_structure_restraints Adams et al., 2010; Afonine et al., 2018.

Acknowledgements

We thank K Ogomori and C Harada for their technical assistance. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants 21H05037 (ON), 22K19371 and 22H02751 (WS); ONO Medical Research Foundation (WS); The Kao Foundation for Arts and Sciences (WS); The Takeda Science Foundation (WS); The Uehara Memorial Foundation (WS); the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED, under grant numbers JP22ama121012 and JP22ama121002 (support number 3272).

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Wataru Shihoya, Email: wtrshh9@gmail.com.

Osamu Nureki, Email: nureki@bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

David Drew, Stockholm University, Sweden.

Kenton J Swartz, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, United States.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 21H05037 to Osamu Nureki.

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 22K19371 to Wataru Shihoya.

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science 22H02751 to Wataru Shihoya.

Ono Medical Research Foundation to Wataru Shihoya.

Kao Foundation for Arts and Sciences to Wataru Shihoya.

Takeda Science Foundation to Wataru Shihoya.

Uehara Memorial Foundation to Wataru Shihoya.

Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research JP22ama121012 (support number 3272) to Wataru Shihoya.

Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research JP22ama121002 (support number 3272) to Wataru Shihoya.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

No competing interests declared.

is a co-founder and scientific advisor for Curreio.

Author contributions

Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Data curation, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing.

Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Project administration.

Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Additional files

Data availability

Cryo-EM Density maps and structure coordinates have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with accession codes EMD-35814 and PDB 8IY5 for the ETB-Gi complex, and EMD-35815 and PDB 8IY6 for the ETB-Gi complex (Receptor focused).

The following datasets were generated:

Sano FK, Akasaka H, Shihoya W, Nureki O. 2023. ETB-Gi complex bound to Endotheline-1, focused on receptor. Electron Microscopy Data Bank. EMD-35815

Sano FK, Akasaka H, Shihoya W, Nureki O. 2023. ETB-Gi complex bound to endothelin-1. Electron Microscopy Data Bank. EMD-35814

Sano FK, Akasaka H, Shihoya W, Nureki O. 2023. ETB-Gi complex bound to Endotheline-1, focused on receptor. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 8IY6

Sano FK, Akasaka H, Shihoya W, Nureki O. 2023. ETB-Gi complex bound to endothelin-1. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 8IY5

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Poon BK, Read RJ, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Adams PD. Real-Space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Structural Biology. 2018;74:531–544. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akasaka H, Tanaka T, Sano FK, Matsuzaki Y, Shihoya W, Nureki O. Structure of the active Gi-coupled human lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 complexed with a potent agonist. Nature Communications. 2022;13:5417. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods in Neurosciences. 1995;25:366–428. doi: 10.1016/S1043-9471(05)80049-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton M, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin: 30 years from discovery to therapy. Hypertension. 2019;74:1232–1265. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bepler T, Morin A, Rapp M, Brasch J, Shapiro L, Noble AJ, Berger B. Positive-unlabeled convolutional neural networks for particle Picking in cryo-electron micrographs. Nature Methods. 2019;16:1153–1160. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes T, Paasche JD, Mehlum A, Sandberg C, Bremnes B, Attramadal H. Regulation and intracellular trafficking pathways of the endothelin receptors. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:17596–17604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B, Tate CG. Active state structures of G protein-coupled receptors highlight the similarities and differences in the G protein and arrestin coupling interfaces. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2017;45:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SGF, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi H-J, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Stevens RC. High-Resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport AP, Hyndman KA, Dhaun N, Southan C, Kohan DE, Pollock JS, Pollock DM, Webb DJ, Maguire JJ. Endothelin. Pharmacological Reviews. 2016;68:357–418. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deupi X, Edwards P, Singhal A, Nickle B, Oprian D, Schertler G, Standfuss J. Stabilized G protein binding site in the structure of constitutively active metarhodopsin-II. PNAS. 2012;109:119–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114089108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AS, Schwinn MK, Hall MP, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Lubben TH, Butler BL, Binkowski BF, Machleidt T, Kirkland TA, Wood MG, Eggers CT, Encell LP, Wood KV. Nanoluc complementation reporter optimized for accurate measurement of protein interactions in cells. ACS Chemical Biology. 2016;11:400–408. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi T, Sugimoto H, Arimoto I, Hiroaki Y, Fujiyoshi Y. Interactions of endothelin receptor subtypes A and B with Gi, go, and Gq in reconstituted phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3090–3099. doi: 10.1021/bi981919m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J, Shen D-D, Zhou XE, Bi P, Liu Q-F, Tan Y-X, Zhuang Y-W, Zhang H-B, Xu P-Y, Huang S-J, Ma S-S, He X-H, Melcher K, Zhang Y, Xu HE, Jiang Y. Cryo-Em structure of an activated VIP1 receptor-G protein complex revealed by a nanobit tethering strategy. Nature Communications. 2020;11:4121. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of coot. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flock T, Ravarani CNJ, Sun D, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Kayikci M, Tate CG, Veprintsev DB, Babu MM. Universal allosteric mechanism for Gα activation by GPCRs. Nature. 2015;524:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves JA, South K, Ahuja S, Zaitseva E, Opefi CA, Eilers M, Vogel R, Reeves PJ, Smith SO. Highly conserved tyrosine stabilizes the active state of rhodopsin. PNAS. 2010;107:19861–19866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009405107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati A, Sunila ES, Kuttan G. IRL-1620, an endothelin-B receptor agonist, enhanced radiation induced reduction in tumor volume in dalton’s lymphoma ascites tumor model. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2012;62:14–17. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haryono A, Ramadhiani R, Ryanto GRT, Emoto N. Endothelin and the cardiovascular system: the long journey and where we are going. Biology. 2022;11:759. doi: 10.3390/biology11050759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M, Hibbs RE, Gouaux E. A fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography-based thermostability assay for membrane protein precrystallization screening. Structure. 2012;20:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua T, Li X, Wu L, Iliopoulos-Tsoutsouvas C, Wang Y, Wu M, Shen L, Brust CA, Nikas SP, Song F, Song X, Yuan S, Sun Q, Wu Y, Jiang S, Grim TW, Benchama O, Stahl EL, Zvonok N, Zhao S, Bohn LM, Makriyannis A, Liu Z-J. Activation and signaling mechanism revealed by cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex structures. Cell. 2020;180:655–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, Kato HE, Livingston KE, Thorsen TS, Kling RC, Granier S, Gmeiner P, Husbands SM, Traynor JR, Weis WI, Steyaert J, Dror RO, Kobilka BK. Structural insights into µ-opioid receptor activation. Nature. 2015;524:315–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Raimondi F, Kadji FMN, Singh G, Kishi T, Uwamizu A, Ono Y, Shinjo Y, Ishida S, Arang N, Kawakami K, Gutkind JS, Aoki J, Russell RB. Illuminating G-protein-coupling selectivity of GPCRs. Cell. 2019;177:1933–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izume T, Miyauchi H, Shihoya W, Nureki O. Crystal structure of human endothelin ETB receptor in complex with sarafotoxin S6b. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2020;528:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato HE, Zhang Y, Hu H, Suomivuori C-M, Kadji FMN, Aoki J, Krishna Kumar K, Fonseca R, Hilger D, Huang W, Latorraca NR, Inoue A, Dror RO, Kobilka BK, Skiniotis G. Conformational transitions of a neurotensin receptor 1–gi1 complex. Nature. 2019;572:80–85. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Che T, Panova O, DiBerto JF, Lyu J, Krumm BE, Wacker D, Robertson MJ, Seven AB, Nichols DE, Shoichet BK, Skiniotis G, Roth BL. Structure of a hallucinogen-activated Gq-coupled 5-HT2A serotonin receptor. Cell. 2020;182:1574–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Shihoya W, Nishizawa T, Kadji FMN, Aoki J, Inoue A, Nureki O. Cryo-Em structure of the human PAC1 receptor coupled to an engineered heterotrimeric G protein. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2020;27:274–280. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y, Baba A. Endothelin-Induced cytoskeletal actin re-organization in cultured astrocytes: inhibition by C3 ADP-ribosyltransferase. Glia. 1996;16:342–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199604)16:4<342::AID-GLIA6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y. Endothelin ETB receptor-mediated astrocytic activation: pathological roles in brain disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22:4333. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Paknejad N, Zhu L, Kihara Y, Ray M, Chun J, Liu W, Hite RK, Huang X-Y. Differential activation mechanisms of lipid GPCRs by lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate. Nature Communications. 2022;13:731. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire JJ, Davenport AP. Endothelin at 25-new agonists, antagonists, inhibitors and emerging research frontiers: IUPHAR review 12. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2014;171:5555–5572. doi: 10.1111/bph.12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, Pardo L, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Granier S. Crystal structure of the µ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagiri C, Shihoya W, Inoue A, Kadji FMN, Aoki J, Nureki O. Crystal structure of human endothelin ETB receptor in complex with peptide inverse agonist IRL2500. Communications Biology. 2019;2:236. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0482-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H, Isshiki K, Hattori M, Maehira H, Yamaguchi T, Masuda K, Shimizu Y, Watanabe T, Hohsaka T, Shihoya W, Nureki O, Kato Y, Watanabe H, Matsuura T. Cell-Free synthesis of human endothelin receptors and its application to ribosome display. Analytical Chemistry. 2022;94:3831–3839. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nureki I, Kobayashi K, Tanaka T, Demura K, Inoue A, Shihoya W, Nureki O. Cryo-Em structures of the β3 adrenergic receptor bound to solabegron and isoproterenol. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2022;611:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto HH, Miyauchi H, Inoue A, Raimondi F, Tsujimoto H, Kusakizako T, Shihoya W, Yamashita K, Suno R, Nomura N, Kobayashi T, Iwata S, Nishizawa T, Nureki O. Cryo-Em structure of the human MT1–gi signaling complex. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2021;28:694–701. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuta A, Tani K, Nishimura S, Fujiyoshi Y, Doi T. Thermostabilization of the human endothelin type B receptor. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2016;428:2265–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. CryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nature Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan AK, Gulati A. Sovateltide mediated endothelin B receptors agonism and curbing neurological disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022;23:3146. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SGF, DeVree BT, Zou Y, Kruse AC, Chung KY, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Chae PS, Pardon E, Calinski D, Mathiesen JM, Shah STA, Lyons JA, Caffrey M, Gellman SH, Steyaert J, Skiniotis G, Weis WI, Sunahara RK, Kobilka BK. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring AM, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Enos MD, Weis WI, Garcia KC, Kobilka BK. Adrenaline-activated structure of β2-adrenoceptor stabilized by an engineered nanobody. Nature. 2013;502:575–579. doi: 10.1038/nature12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosanò L, Spinella F, Bagnato A. Endothelin 1 in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2013;13:637–651. doi: 10.1038/nrc3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihoya W, Nishizawa T, Okuta A, Tani K, Dohmae N, Fujiyoshi Y, Nureki O, Doi T. Activation mechanism of endothelin ETB receptor by endothelin-1. Nature. 2016;537:363–368. doi: 10.1038/nature19319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihoya W, Nishizawa T, Yamashita K, Inoue A, Hirata K, Kadji FMN, Okuta A, Tani K, Aoki J, Fujiyoshi Y, Doi T, Nureki O. X-Ray structures of endothelin ETB receptor bound to clinical antagonist bosentan and its analog. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2017;24:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihoya W, Izume T, Inoue A, Yamashita K, Kadji FMN, Hirata K, Aoki J, Nishizawa T, Nureki O. Crystal structures of human ETB receptor provide mechanistic insight into receptor activation and partial activation. Nature Communications. 2018;9:4711. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Paknejad N, Dey R, Huang J, Lee M-Y, Williams D, Jordan KD, Eng ET, Ernst OP, Meyerson JR, Hite RK, Walz T, Liu W, Huang X-Y. Structural basis of the activation of heterotrimeric Gs-protein by isoproterenol-bound β1-adrenergic receptor. Molecular Cell. 2020;80:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tencé M, Ezan P, Amigou E, Giaume C. Increased interaction of connexin43 with zonula occludens-1 during inhibition of gap junctions by G protein-coupled receptor agonists. Cellular Signalling. 2012;24:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatakrishnan AJ, Deupi X, Lebon G, Tate CG, Schertler GF, Babu MM. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013;494:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MA, Coleman DE, Lee E, Iñiguez-Lluhi JA, Posner BA, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. The structure of the G protein heterotrimer Gi alpha 1 beta 1 gamma 2. Cell. 1995;83:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Guo S, Zhuang Y, Yun Y, Xu P, He X, Guo J, Yin W, Xu HE, Xie X, Jiang Y. Molecular recognition of an acyl-peptide hormone and activation of ghrelin receptor. Nature Communications. 2021;12:5064. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia R, Wang N, Xu Z, Lu Y, Song J, Zhang A, Guo C, He Y. Cryo-em structure of the human histamine H1 receptor/gq complex. Nature Communications. 2021;12:e2. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Ikuta T, Kawakami K, Kise R, Qian Y, Xia R, Sun M-X, Zhang A, Guo C, Cai X-H, Huang Z, Inoue A, He Y. Structural basis of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 activation and biased agonism. Nature Chemical Biology. 2022a;18:281–288. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Wu L, Liu S, Liu X, Cao X, Zhou C, Zhang J, Fu Y, Guo Y, Wu Y, Tan Q, Wang L, Liu J, Jiang L, Fan Z, Pei Y, Yu J, Cheng J, Zhao S, Hao X, Liu Z-J, Hua T. Structural basis for strychnine activation of human bitter taste receptor TAS2R46. Science. 2022b;377:1298–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.abo1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Jia G, Wu C, Wang W, Cheng L, Li Q, Li Z, Luo K, Yang S, Yan W, Su Z, Shao Z. Structures of signaling complexes of lipid receptors S1PR1 and S1PR5 reveal mechanisms of activation and drug recognition. Cell Research. 2021;31:1263–1274. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00566-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y, Wang Y, He B, He X, Zhou XE, Guo S, Rao Q, Yang J, Liu J, Zhou Q, Wang X, Liu M, Liu W, Jiang X, Yang D, Jiang H, Shen J, Melcher K, Chen H, Jiang Y, Cheng X, Wang M-W, Xie X, Xu HE. Molecular recognition of morphine and fentanyl by the human μ-opioid receptor. Cell. 2022;185:4361–4375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivanov J, Nakane T, Forsberg BO, Kimanius D, Hagen WJ, Lindahl E, Scheres SH. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife. 2018;7:e42166. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]