Abstract

The population of incarcerated adults in the United States is aging rapidly. Incarcerated adults experience accelerated aging, the process in which exposure to incarceration speeds up biological aging. The current article highlights unique structural factors and care practices that incarcerated older adults face in correctional and community health systems. These factors and practices are often in direct opposition to age-friendly care. Opportunities exist to expand research, modify existing policies, and change current care practices. Given their expertise in health system processes, gerontological nurses in correctional and community health care systems can play a pivotal role in improving the care of this growing and vulnerable population.

Approximately 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States on any given day, and this population is aging rapidly (Sawyer & Wagner, 2022). Between 1999 and 2016, the number of adults aged ≥55 years increased by 280%, compared to an increase of only 3% in those aged <55 years (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018). Incarcerated individuals are frequently impacted by health, social, and economic factors prior to incarceration that influence the aging process; the stressors of incarceration itself are also detrimental to one’s health. As awareness of these health impacts on aging expand, increasing attention is being paid to the theory of accelerated aging—the concept that individuals who are exposed to incarceration exhibit premature biological aging. One study found that every year of exposure to incarceration is associated with a 2-year reduction in life expectancy (Patterson, 2013). As a result, researchers and policymakers, including the Office of the Inspector General (OIG; 2016) at the U.S. Department of Justice, identify age ≥50 years as the threshold for research and reports on the aging prison population. As of December 2021, >275,000 people in state and federal prisons met this cutoff (Carson, 2022).

Although significantly understudied, the impact of incarceration on the health of incarcerated older adults is receiving more attention as the challenges and costs of caring for this population are realized. When evaluating the medical costs of older individuals incarcerated in federal prisons in 2009, the OIG (2016) found that the five federal institutions with the highest percentage of incarcerated older adults spent >$10,000 per person, whereas the five federal prisons with the smallest percentage of older prisoners spent <$2,000 per person. These increased costs came from many sources, including higher staffing needs, more medications, more hospitalizations, and more catastrophic medical care episodes. Health care expenditure data from state prisons are difficult to find, but available data from multiple states echo the federal system findings that care costs for older prisoners are far greater than their younger counterparts. In North Carolina, for example, health care for those aged ≥50 years cost the state correctional system more than four times what was spent on younger individuals (Chiu, 2010). As this population of incarcerated older adults continues to grow, the correctional system will spend an increasing percentage of its health care budget on services provided in community settings. In 2016, the state of Virginia spent approximately twice as much on off-site health care for those aged ≥55 years compared to those aged <55 years; although they represented only 12.2% of Virginia’s prison population, this older cohort accounted for 40% of the Department of Corrections hospital costs (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018).

Nurses in correctional facilities are the primary point of contact for incarcerated older adults accessing health services and play a critical role in managing their care. Nurses in other settings also interface with incarcerated older adults, particularly as they enter hospital environments. Unfortunately, little formal education on the policies that shape care delivery for incarcerated older adults and age-related care needs of this population is available. As the aging prison population continues to require more services in non-correctional settings, gerontological nurses in the community will play an increasing role in their care. Gerontological nurses should be aware of the unique conditions, risks, and needs of this marginalized group. Thus, the current article (1) summarizes age-related health challenges faced by incarcerated older adults; (2) details relevant policies and norms that gerontological nurses should be familiar with that shape the care of this population in correctional and community settings; and (3) identifies potential areas for gerontological nurse involvement in improving the clinical care of and research regarding the health outcomes of incarcerated older adults. As the primary points of contact for these patients in correctional and non-correctional care settings, the involvement of nursing—and gerontological nursing in particular—is essential to improving the care of this underserved population. With their unique knowledge of the clinical care of older adults and day-to-day operations of the health care system, gerontological nurses can contribute to system changes that could lead to improved patient outcomes, decreased costs, and reduction of health inequities for incarcerated older adults.

GERIATRIC SYNDROMES IN INCARCERATED OLDER ADULTS

According to the theory of accelerated aging, people who are exposed to incarceration face a higher rate of health decline due to a combination of environmental factors and predisposing characteristics (Maschi et al., 2012). Whether accelerated aging is a direct result of exposure to confinement or represents the cumulative effect of the many other factors that contribute to poor health associated with an increased risk of incarceration (e.g., lower socioeconomic status, increased history of trauma and early life stressors, higher rates of substance use disorders), accelerated aging leads to higher rates and earlier presentations of geriatric conditions, along with a significant reduction in life expectancy (Figure 1) (Berg et al., 2021; Patterson, 2013). In an age-adjusted analysis, incarcerated individuals were found to have the same rate of geriatric morbidity at age 59 years as community-dwelling individuals at age 75 years, including functional, mobility, and hearing impairment, as well as higher medical comorbidity, urinary incontinence, and falls (Greene et al., 2018). This distinction persists when accounting for socioeconomic differences.

Figure 1.

Highly prevalent health conditions among incarcerated older adults.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, and mental health conditions are also over-represented in incarcerated individuals and at younger ages than would normally be expected. A study on cognition using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment reported that 78% of incarcerated participants with an average age of 59 years tested positive for MCI (Ahalt et al., 2018); according to the Alzheimer’s Association, between 12% and 18% of community-dwelling adults aged ≥60 years have MCI (Loeb et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2009). Dementia prevalence is more difficult to assess, although the absolute number of incarcerated individuals with dementia is predicted to triple between 2010 and 2050, from approximately 125,000 to >380,000 (Maschi et al., 2012). Incarcerated adults aged ≥50 years also have more than twice the rate of mental health conditions compared to the non-incarcerated population, with the highest disparity in the most severe diagnoses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Di Lorito et al., 2018). Geriatric nurses who care for incarcerated older adults (i.e., aged ≥50 years) should be aware that these individuals are more likely to experience every medical condition compared with their non-incarcerated counterparts, including cognitive diseases that may impact their ability to participate in their own health care.

CORRECTIONAL HEALTH CARE: POLICIES AND NORMS

In addition to understanding the unique risk profile of incarcerated older adults, knowledge of the environment in which they live and receive care within correctional settings may have implications for care provided by community-based gerontological nurses in non-correctional health care settings. In the sections below, we describe the physical environment and the processes older adults face while incarcerated.

The Built Environment

The current design of most correctional facilities does not accommodate aging or age-related physical or cognitive changes. The use of bunk beds is one example; lack of accessible bathrooms is another. Incarcerated individuals often have to walk significant distances and use stairs to reach dining or other necessary facilities, and wheelchair ramps or elevators are not always available. In addition to these environmental factors, there are specific so-called prison activities of daily living (PADLs) that may be uniquely challenging for older adults. PADLs include standing in line for medications and/or food and dropping to the floor for alarms. The inability to complete PADLs has been associated with depression and increased severity of suicidal ideation in those aged ≥50 years, particularly among men (Barry et al., 2017).

According to a 2016 report from the OIG, a nationwide review of accessibility in its correctional facilities has not been completed since 1996. Some individual states have started making efforts to create age-friendly environments. In 2006, New York opened a first-in-the-nation medical unit dedicated to the care of incarcerated individuals with dementia. Wisconsin recently opened a 65-bed Assisted Needs Facility that provides rehabilitation and health care for incarcerated older adults. Yet the needs far outweigh current available resources. In Virginia, the Deerfield Correctional Center houses approximately 900 individuals aged ≥50 years, although the population in need of the services provided there is more than five times the number of beds available.

Copays

According to the 1976 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Estelle v. Gamble, individuals under law enforcement custody in the United States, whether in state, federal, or local jurisdictions, have the right to health care under the Eighth Amendment. Specifically, Estelle orders access to care, requires that correctional systems make it possible for an incarcerated person to receive care that has been ordered by a health care professional, and ensures that health care decisions are made by health care professionals and on the basis of medical factors only.

The reality of how this mandated health care is delivered, however, varies significantly across states and correctional facilities. In 40 states and in the federal prison system, copays are required for many health care services. Although these copays are often only a few dollars and thus may seem minimal, the average pay for individuals incarcerated in the United States is between $0.13 and $1.30 per hour, and some states do not pay incarcerated individuals anything for their labor (American Civil Liberties Union, 2022). Although it varies from state to state, the average prison copay would equal more than $200 in a non-correctional setting (Sawyer, 2017). As discussed above, incarcerated older adults have high medical needs that require more health care yet paradoxically may also make them less able to perform low to no-pay prison jobs, thus reducing their ability to earn necessary copays. The legal protections afforded under Estelle mean that correctional facilities may not deny patients needed health care, yet copays nonetheless create a barrier that may deter patients from seeking help (Beleckis, 2022).

Accessing and Recognizing the Need for Care

In most correctional facilities, health care is driven by correctional nurses. Requests for care from incarcerated individuals are reviewed and triaged by correctional nurses who are often over-stretched and understaffed, causing delays in care (Beleckis, 2022). Because most health care requests require the individual to describe their symptoms or concerns, older individuals, particularly those with cognitive impairments, may have difficulty with the request process. They may provide incomplete or inaccurate information, making it difficult for correctional nurses to appropriately triage their needs. In addition, few correctional nurses receive targeted education and/or certification in gerontological nursing and are thus not specifically trained to recognize early geriatric syndromes, conditions related to aging, or signs of cognitive impairment or dementia (Kitt-Lewis & Loeb, 2022). Similarly, most non-medical correctional staff have not been trained to recognize age-related conditions, including behavioral changes related to cognitive decline. Because it is these non-medical staff with whom incarcerated individuals most often interact, this represents a major missed opportunity for early detection and implementation of behavioral mitigation strategies.

COMMUNITY HEALTH CARE: POLICIES AND NORMS

Most incarcerated individuals receive primary care through health services units within correctional institutions, but when more advanced care is necessary, they are transferred to community clinics and hospitals. Although there is heterogeneity in the rules that govern community care for incarcerated individuals across states and settings, as well as a significant lack of research regarding this care, there are nevertheless a number of de facto norms that are worth highlighting in relation to the care of older adults. We discuss these norms as they play out in the inpatient setting as they are more likely to have an impact during these longer encounters, but many of these norms also exist in the care provided in clinics and the same recommendations therefore apply in those settings.

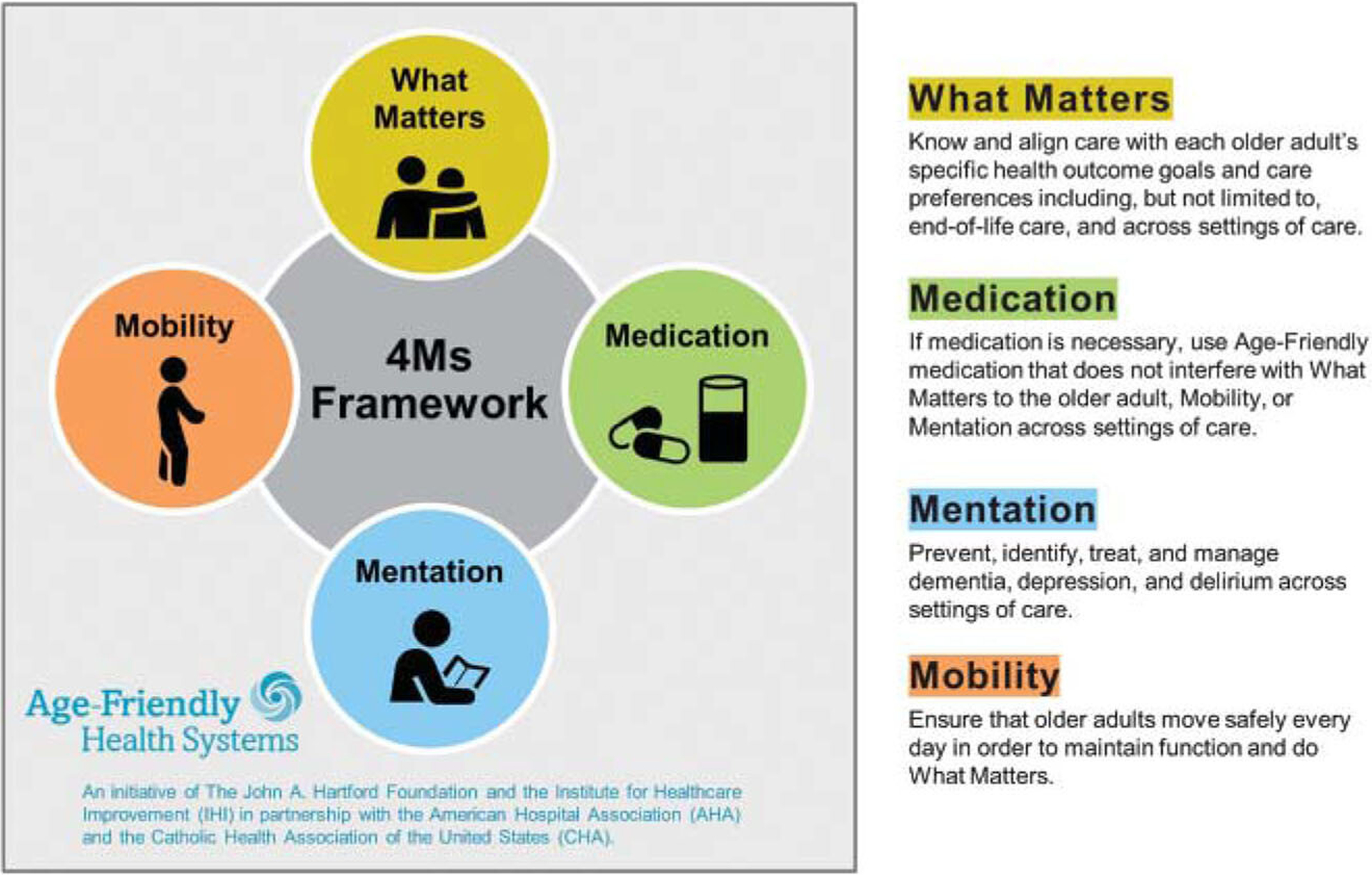

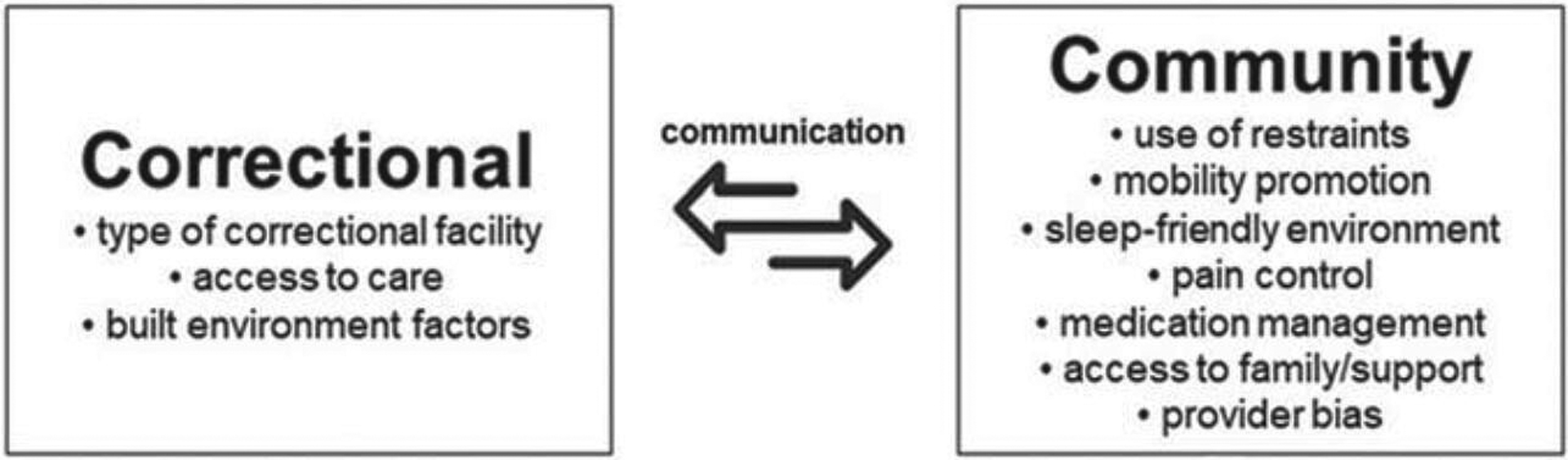

Many of the current care practices that incarcerated individuals experience in the community are exactly the opposite of what is generally considered “age-friendly care.” According to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and the John A. Hartford Foundation, age-friendly care includes four evidence-based elements: (1) knowledge of a patient’s care preferences and alignment of the plan of care with those preferences; (2) appropriate and limited use of medications; (3) active efforts to prevent, identify, treat, and manage dementia, depression, and delirium; and (4) encouragement of mobility and frequent ambulation (IHI, 2022) (Figure 2). Available evidence suggests that, although health care providers may be aware that incarcerated individuals have the same privacy and health care decision-making rights as non-incarcerated individuals, providers do not always act in accordance with these rights (Brooks et al., 2021; Rorvig & Williams, 2021). Communication challenges between community and correctional providers are often more substantial than between community providers, making goal alignment and accurate medication management more difficult (Morris et al., 2022; Scarlet & Dreesen, 2019). The ability to manage dementia, delirium, and other mental health conditions in the hospital relies significantly on interactions between patients and their health care providers; unfortunately, approximately 40% of inpatient nurses surveyed stated they spend less time interacting with hospitalized incarcerated patients compared to non-incarcerated patients (Brooks et al., 2021). The ubiquitous use of law enforcement restraints in incarcerated patients in community settings, even in those who are critically ill, limits patient opportunities for ambulation (Bansal & Haber, 2021). In addition to these practices, a number of other incarceration-specific care practices are likely to impact the health of incarcerated older patients, including provider bias, inadequate pain control, and failure to create a sleep-friendly environment (Figure 3). Although there are limited data on the prevalence and impact of these incarceration-specific factors, there are opportunities for gerontological nurses in community settings to improve the care of incarcerated older patients through the creation of more age-friendly environments.

Figure 2.

The 4Ms of an age-friendly health care system.

From The John A. Hartford Foundation and Institute for Healthcare Improvement; available in the public domain, permission to reprint is not required.

Figure 3.

Factors impacting the care of incarcerated older adults in correctional and community settings.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE RESEARCH, POLICY, AND CARE

Perhaps the greatest barrier to advancing the care of the aging incarcerated population is lack of research on which to base changes and measure improvements. The reasons for this dearth of work are many, but there are three actionable factors that should be highlighted: lack of (a) an agreed upon target population, (b) data, and (c) funding. States, federal organizations, and the research community need to coalesce around a single definition of who counts as an incarcerated older person; the definition may not be perfect, but it will allow for consistent and comparable outcome measurements. Lack of data is a broader issue and includes costs, medical conditions, and health outcomes. For example, there are a number of estimates regarding the higher health care costs for older compared to younger incarcerated individuals, but exact costs and for which conditions—chronic, acute, medical, surgical—are as yet unstudied (Ahalt et al., 2013). Similarly, more funding is needed to support research into this often overlooked and ostracized population. An analysis of all grants awarded by the National Institutes of Health between 2008 and 2012 found that of 250,000 successful applications, only 180 (<0.1%) focused on criminal justice health (Ahalt et al., 2015). Within those 180 projects, the majority focused on substance use disorder and/or HIV, with another 11% focused on mental health, and another 8% on juvenile health; only two projects (1.1%) focused on aging (Ahalt et al., 2015).

ADVANCING GERONTOLOGICAL NURSING FOR INCARCERATED OLDER ADULTS

The population of incarcerated older individuals in the United States is growing rapidly. As this demographic shift occurs, this population will require more health care, in and out of correctional facilities. Within correctional facilities, gerontological nurses can encourage increased education of medical and non-medical personnel regarding the identification and management of age-related physical and cognitive decline and can advocate for age-friendly changes to PADLs. Gerontological nurses in correctional and community settings can work to improve the lines of communication across this gap. Within the community, gerontological nurses can promote age-friendly changes to incarceration-specific care processes, including educating providers on incarcerated patients’ rights. As the incarcerated population continues to age, gerontological nurses, with their expertise in the care of older adults and extensive knowledge of health care systems, will be essential to providing high-quality and equitable care to this marginalized group.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Miller BL, Rosen HJ, Barnes DE, & Williams BA (2018). Cognition and incarceration: Cognitive impairment and its associated outcomes in older adults in jail. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(11), 2065–2071. 10.1111/jgs.15521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahalt C, Trestman RL, Rich JD, Greifinger RB, & Williams BA (2013). Paying the price: The pressing need for quality, cost, and outcomes data to improve correctional health care for older prisoners. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(11), 2013–2019. 10.1111/jgs.12510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahalt C, Wang EA, & Williams B (2015). State of research funding from the National Institutes of Health for criminal justice health research. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 240–241. 10.7326/L15-5116-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Civil Liberties Union. (2022). Captive labor: Exploitation of incarcerated workers. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/2022-06-15-captivelabor-researchreport.pdf

- Bansal AD, & Haber LA (2021). On a ventilator in shackles. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(12), 3878–3879. 10.1007/s11606-021-07097-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry LC, Wakefield DB, Trestman RL, & Conwell Y (2017). Disability in prison activities of daily living and likelihood of depression and suicidal ideation in older prisoners. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(10), 1141–1149. 10.1002/gps.4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beleckis J (2022). Perpetuating poverty: Formerly incarcerated people warn of ‘agonizing’ choices around Wisconsin’s prison copays. https://www.wpr.org/perpetuating-poverty-formerly-incarcerated-people-warn-agonizing-choices-around-wisconsins-prison

- Berg MT, Rogers EM, Lei MK, & Simons RL (2021). Losing years doing time: Incarceration exposure and accelerated biological aging among African American adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(4), 460–476. 10.1177/00221465211052568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks KC, Makam AN, & Haber LA (2021). Caring for hospitalized incarcerated patients: Physician and nurse experience. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37, 485–487. 10.1007/s11606-020-06510-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson EA (2022). Prisoners in 2021: Statistical tables. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/p21st.pdf

- Chiu T (2010). It’s about time: Aging prisoners, increasing costs, and geriatric release. The Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/publications/its-about-time-aging-prisoners-increasing-costs-and-geriatric-release [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorito C, Völlm B, & Dening T (2018). Ageing patients in forensic psychiatric settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(12), 1548–1555. 10.1002/gps.4981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estelle v. Gamble, 429 97 (Supreme Court of the United States 1976).

- Greene M, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Metzger L, & Williams B (2018). Older adults in jail: High rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health & Justice, 6(1), 3. 10.1186/s40352-018-0062-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2022). What is an age-friendly health system? https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

- Kitt-Lewis E, & Loeb SJ (2022). Emerging need for dementia care in prisons: Opportunities for gerontological nurses. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 48(2), 3–5. 10.3928/00989134-20220111-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, & Lawrence F (2008). Comparing incarcerated and community-dwelling older men’s health. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 30(2), 234–249. 10.1177/0193945907302981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Kwak J, Ko E, & Morrissey MB (2012). Forget me not: Dementia in prison. The Gerontologist, 52(4), 441–451. 10.1093/geront/gnr131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NP, Smith WR, & Zisman-Ilani Y (2022). Mental health in the era of mass incarceration. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 73(1), 1. 10.1176/appi.ps.73104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Inspector General. (2016). The impact of an aging inmate population on the Federal Bureau of Prisons. https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2015/e1505.pdf

- Patterson EJ (2013). The dose-response of time served in prison on mortality: New York State, 1989–2003. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), 523–528. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2018). State prisons and the delivery of hospital care. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2018/07/19/state-prisons-and-the-delivery-of-hospital-care

- Rorvig L, & Williams B (2021). Providing ethical and humane care to hospitalized, incarcerated patients with COVID-19. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 38(6), 731–733. 10.1177/1049909121994313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer W (2017). The steep cost of medical copays in prison puts health at risk. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2017/04/19/copays/ [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer W, & Wagner P (2022). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2022. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2022.html [Google Scholar]

- Scarlet S, & Dreesen EB (2019). Delivering hospital-based medical care to incarcerated patients in North Carolina state prisons: A call for communication and collaboration. North Carolina Medical Journal, 80(6), 348–351. 10.18043/ncm.80.6.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BA, Lindquist K, Hill T, Baillargeon J, Mellow J, Greifinger R, & Walter LC (2009). Caregiving behind bars: Correctional officer reports of disability in geriatric prisoners. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(7), 1286–1292. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]