Abstract

Introduction

This systematic literature review (SLR) assessed incidence/prevalence of cryptoglandular fistulas (CCF) and outcomes associated with local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCFs.

Methods

Two trained reviewers searched PubMed and Embase for observational studies evaluating the incidence/prevalence of cryptoglandular fistula and clinical outcomes of treatments for CCF after local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF.

Results

In total 148 studies met a priori eligibility criteria for all cryptoglandular fistulas and all intervention types. Of those, two assessed incidence/prevalence of cryptoglandular fistulas. Eighteen reported clinical outcomes of surgeries of interest in CCF and were published in the past 5 years. Prevalence was reported as 1.35/10,000 non-Crohn’s patients, and 52.6% of non-IBD patients were found to progress from anorectal abscess to fistula over 12 months. Primary healing rates ranged from 57.1% to 100%; recurrence occurred in a range of 4.9–60.7% and failure in 2.8–18.0% of patients. Limited published evidence suggests postoperative fecal incontinence and long-term postoperative pain were rare. Several of the studies were limited by single-center design with small sample sizes and short follow-up durations.

Discussion

This SLR summarizes outcomes from specific surgical procedures for the treatment of CCF. Healing rates vary according to procedure and clinical factors. Differences in study design, outcome definition, and length of follow-up prevent direct comparison. Overall, published studies offer a wide range of findings with respect to recurrence. Postsurgical incontinence and long-term postoperative pain were rare in the included studies, but more research is needed to confirm rates of these conditions following CCF treatments.

Conclusion

Published studies on the epidemiology of CCF are rare and limited. Outcomes of local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures show differing success and failure rates, and more research is needed to compare outcomes across various procedures. (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42020177732).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-023-02452-x.

Keywords: Anal fistula, Complex cryptoglandular fistula, Healing, Incontinence, Pain, Recurrence

Key Summary Points

| There is a great need for more epidemiology work to determine the true burden of CCF in the global population. |

| Primary healing rates associated with local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF were 57.1–100%. |

| Recurrence rates associated with local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF were 4.9–60.7%. |

| Failure of local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF occurred in 2.8–18.0% of patients. |

| There are substantial knowledge gaps and a great need for future research to help improve our understanding of how best to support and treat patients with CCF. |

Introduction

Anal fistulas are abnormal passages connecting the anal canal to the skin near the anus [1]. Approximately 90% of anal fistulas are idiopathic [2]. Parks’ cryptoglandular theory on the pathogenesis of anal fistulas hypothesizes that infected anal glands and surrounding anal abscesses eventually progress to fistulas [3]. About 40–70% of patients with an anal abscess have a concomitant anal fistula; and even months or years after abscess drainage, 30% of patients will be diagnosed with an anal fistula [1].

Cryptoglandular fistulas (CF) are generally classified by the anatomic location of the primary tract relative to the anal sphincter muscles: intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric fistulas [2, 4]. CF with significant involvement of the external sphincter or multiple tracts are classified as “complex” [5]. Patients with complex CF (CCF) often experience compromised quality of life due to painful defecation, constant discharge, reduced social functioning, and/or recurrence [6]. Eradicating the anal fistula(s) and preventing recurrence while maintaining fecal continence are the goals of managing anal fistulas [1]. The surgical management of anal fistulas is a trade-off between the extent of operative sphincter division and postoperative functional loss. For example, higher rates of fecal incontinence (FI) and longer healing times are often associated with effective, but sphincter-dividing, options such as fistulotomy and fistulectomy [1, 5]. Conversely, less invasive sphincter-sparing interventions, such as loose seton and fibrin glue, have varying success rates and patients often face multiple operations [4].

This systematic literature review (SLR) aimed to: (1) identify the global incidence/prevalence of CF; and (2) evaluate and summarize evidence published within the past 5 years on treatment outcomes of local surgical (fistulotomy, lay open fistulotomy, fistulectomy, modified Parks’ technique, and advancement flap) and intersphincteric ligation procedures (ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract [LIFT], BioLIFT (LIFT with a bioprosthetic graft), and transanal opening of intersphincteric space [TROPIS]) for CCF.

Materials and Methods

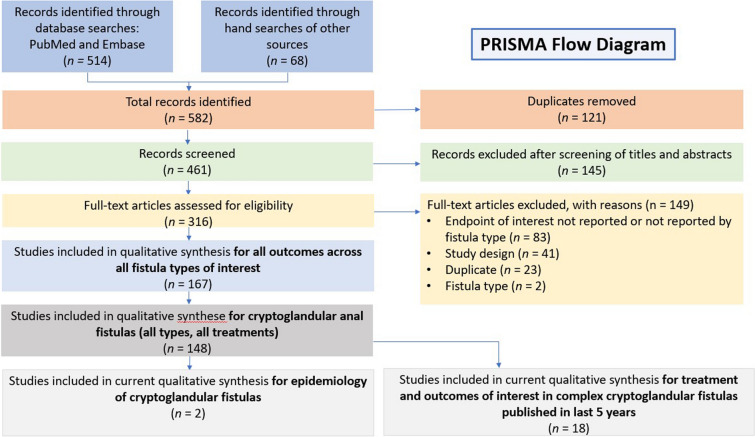

The SLR was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [7]. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42020177732). This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Search Strategy and Eligibility

Eligibility was based on study Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Time, and Study design (PICOTS) (Supplementary Material Table S1). The electronic search was conducted on March 25, 2020 in PubMed and Embase (Supplementary Material Tables S2 and S3) using human studies published in English up to 10 years prior to the search date. An additional manual search of key publications and references was conducted to identify any studies missed by the electronic search. Only studies reporting incidence/prevalence of CF or outcomes for CCF for local surgical or intersphincteric ligation procedures of interest were included in this manuscript.

Titles and abstracts of identified studies were independently screened by two reviewers to determine whether they met the PICOTS criteria. If so, the full-text articles were independently assessed by each reviewer to determine eligibility for data abstraction. Discrepancies in either phase were resolved by consensus. If consensus could not be achieved, a third senior reviewer made the determination. Out-of-scope studies and those for which the full text was unavailable, and the abstract did not include sufficient information were excluded with a documented rationale. Data from eligible studies were independently abstracted by two reviewers using a standardized data abstraction form. Both reviewers jointly examined abstraction spreadsheets to synthesize the data into one master spreadsheet. Data were extracted for multiple variables, including study type, design, population, outcomes, and limitations.

Studies included in this report met the following criteria: (1) reported on CF; (2) used an observational study design; (3) measured incidence/prevalence (for any CF) or clinical outcomes of interest (healing/failure/recurrence rates, pain, FI) (for CCF only); and (4) were original research (Supplementary Material Table S1). Case series were designated as cohort studies if they met all of the following pre-specified criteria: more than 10 patients per fistula type, patients sampled on the basis of exposure (not outcome), outcome assessed over a pre-specified follow-up period or mean/median follow-up reported, and information available to calculate the absolute/relative risk. In addition, sampling had to be labeled as “consecutive” or text had to indicate that all eligible patients were included to avoid selection bias. CCF also had to be reported separately from other types of fistulas.

Study populations were classified as surgery-naïve and/or surgery-experienced. Patients receiving drainage and incision or prior seton were classified as surgery naïve as these procedures are often performed as preparatory procedures for the current surgery.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias in each article using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for observational studies [8]. Any disagreements were settled by consensus, with a third reviewer making the determination if consensus could not be reached.

Results

Literature Search

The electronic search returned 514 articles; an additional 68 were identified from a manual search of other sources; 121 duplicates were deleted. Of the 461 records screened on the basis of titles and abstracts, we included 316 in the full-text assessment. Of those, 149 were excluded on the basis of inclusion/exclusion criteria. CF were assessed in 148 studies (PRISMA flow diagram, Fig. 1). Of these, two studies reported the incidence/prevalence of CF [9, 10]. Owing to the large volume of studies identified (n = 43) that reported outcomes of local surgical treatments and intersphincteric ligation procedures, the current synthesis is limited to those published on CCF between January 1, 2015 and March 25, 2020 (n = 18). Details of the studies are included in Table 1. Results from combined surgical procedures (e.g., mucosal anal flap [MAF] combined with injection of platelet-rich plasma) were out-of-scope; however, fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty (FIPS) was included because the two techniques are essentially two steps of a single procedure. Criteria for what comprised a complex fistula were determined by each respective study author and are included in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies of local surgical procedures (n = 10) and intersphincteric ligation (n = 8) included in the SLR

| Author, year | Country, location | Key inclusion criteria | Key exclusion criteria | Patients’ surgical experience | Sample size for CCF | Intervention for complex CCF | Follow-up (range) | Risk of bias (ROBINS-I) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local surgical procedures | ||||||||

| Boenicke 2017 | Dept of General and Visceral Surgery at the Helios Univ Hosp, Wuppertal, Germany | Patients who had cryptoglandular transsphincteric (larger than 1/3 of the external sphincter involved) or suprasphincteric fistula, with previous fistulectomy with seton drainage, and were treated with advancement flap in the study institution between January 2012 and January 2015 |

1. IBD 2. High RVF |

Surgery experienced | 61 | Extrasphincteric fistula tract excised from the external opening to the intersphincteric space, followed by seton placement for 6–8 weeks, and finally advancement flap procedure (n = 66; 61 attended follow-up) | Mean 25 (12–50) months | Moderate |

| Ding 2015 | Dept of Colorectal Surgery, Colorectal Disease Center of People’s Liberation Army and Dept of Medicine Second Artillery General Hosp Beijing, China |

Consecutive consenting patients with anal fistula accessed in hospital (February 2011 to September 2013): 1. Primary cryptogenic anal fistula 2. ≥ 18 years old 3. Completion at 1-year follow-up |

1. IBD 2. RVF 3. Diabetes 4. Previous pelvic radiotherapy 5. Fecal incontinence (Wexner Incontinence Score > 7) |

Surgery experienced or naïve | 79 | Cutting seton with fistulectomy (n = 41), advancement flap (n = 38) | 1 year | Moderate |

| El-Said 2019 | The Colorectal Surgery Unit of Mansoura Univ Hosp, Mansoura, Egypt |

Primary or recurrent CAF (January 2016 to January 2018) CAF included HTF, suprasphincteric, extrasphincteric, horseshoe fistulas, and anterior fistula in female patients |

1. Intersphincteric anal fistula or low transsphincteric anal fistula involving < 30% of the external anal sphincter 2. Coexisting anal condition such as hemorrhoids and anal fissure were excluded 3. Secondary anal fistula caused by IBD, malignancy, STDs, or radiation |

Surgery experienced or naïve | 32 | Modified Parks’ technique (n = 32) | Median 12 (6–24) months | Moderate |

| Emile 2018 | Colorectal Surgery Unit of Mansoura Univ Hosp, Mansoura, Egypt | Primary cryptoglandular anal fistula admitted to colorectal surgery unit between January 2009 and January 2017 | Secondary fistula-in-ano due to traumatic conditions, IBDs, malignancy, radiation therapy, STDs, tuberculosis, or other specific etiologies | Surgery experienced or naïve | 266 had high anal fistula | Anal advancement flap (n = 9) | Median 22 (5–42) months | Moderate |

| Farag 2019 | Colorectal Unit, Cairo Univ Hosp, Cairo, Egypt |

Consecutive patients diagnosed with high CAF: high transsphincteric perianal fistulae (defined as involving > 50% of the external anal sphincter) and suprasphincteric perianal fistulae (defined as fistulae extended completely above the external anal sphincter), presenting to the study institution from March 2016 and August 2017 Age between 18 and 60 years |

1. Simple anal fistula 2. Preoperative incontinence 3. Comorbidity and chronic illness affecting healing process 4.Acute anal sepsis 5. Impaired fecal continence before operation |

Not reported | 173 | One-stage fistulectomy and reconstruction (n = 175) | 1 year | Moderate |

| Lee 2015 | The National Univ Hosp, Singapore | Underwent advancement flap procedure for high anal fistula (defined as fistula with involvement of proximal 2/3 of the internal and external sphincter muscle) of cryptoglandular origin at the study institution from June 2003 to April 2012 |

1. Concurrent RVF 2. Fistulas from Crohn’s disease 3. Fistulas from HIV 4. Incontinence or difficulty controlling solid or liquid motion or flatus prior to surgery |

Surgery experienced or naïve | 61 |

Advancement flap (n = 61), including: Endorectal advancement flap (n = 48) Anocutaneous advancement flap (n = 13) |

Median 6.5 (1–59) months | Moderate for other outcomes; serious for FI outcome |

| Litta 2019 | Proctology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy |

1. Underwent FIPS (for either primary or recurrent, simple or CAF in the study institution between June 2006 and May 2017 2. Complex anal fistulas including: (a) high transsphincteric tract, crossing > 30% of the external anal sphincter; (b) low transsphincteric tract, only when considered at risk for postoperative fecal incontinence (anterior fistula in women, recurrent fistula, or history of fecal incontinence); and (c) suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric tracts 3. Follow-up of at least 1 year |

1. Extra- and suprasphincteric anal fistula 2. IBD 3. Traumatic-, cancer-, or radiotherapy-related anal fistula |

Not reported | 103 | FIPS (n = 103) | Mean 55.9 (12–143) months; standard deviation 30.9 months | Serious |

| Podetta 2019 | Not reported |

Group A: consecutive patients treated in the study institution by MAF for CAFa of cryptoglandular origin from January 2005 to December 2016. Group B: patients in group A presented with recurrent disease, diagnosed as CAF and operated with a second MAF Group C: patients in group B presented with a second recurrence, underwent a 3rd MAF |

1. IBD 2. RVF 3. History of perineal radiation therapy or malignancy-associated anal fistula 4. simple anal fistula in groups B and C |

Surgery experienced or naïve |

Group A: 121 Group B: 32 Group C: 6 |

MAF (n = 121) | Median 74 (8–148) months | Moderate |

| Schiano di Visconte 2018 | S. Maria dei Battuti Hosp, Conegliano, Treviso, Italy |

1. Treated with RAF or Permacol™ paste injection between September 1, 2013 and January 31, 2016 2. Primary and recurrent complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas 3. Transsphincteric fistula (tract crossing > 30% of the external anal sphincter) 4. Suprasphincteric fistula 5. Extrasphincteric fistula 6. Horseshoe fistula |

1. CD 2. Intersphincteric or low transsphincteric fistulas (involving < 30% of the sphincter complex) 3. AVF or RVF 4. Rectourethral fistulas 5. Fecal incontinence (Continence Grading Scale > 9) 6. Prior rectal anastomosis 7. Prior pelvic radiotherapy |

Surgery experienced or naïve | 52 |

Rectal advancement flap (n = 31) Permacol™ paste (n = 21) |

Median 24 months (range not reported) | Moderate |

| Visscher 2016 | A tertiary center and a private center specialized in proctology (both unnamed), authors’ affiliation is the Netherlands | Prior 3D-EAUS for cryptoglandular anal fistula between 2002 and 2012 | Non-cryptoglandular fistulas (i.e., diagnosis of IBD, hidradenitis suppurativa, tuberculosis, HIV, actinomycosis, or anal carcinoma) | Surgery experienced or naïve | 47 had high fistula |

Fistulectomy only (n = 28), fistulectomy combined with MAF (n = 19) |

Median 26 (2–118) months (includes all fistulas) | Moderate |

| Intersphincteric ligation | ||||||||

| Deimel 2016 | Not reported but authors’ affiliation is Germany | Patients with HTF who were treated with modified LIFT between October 2012 and February 2016 | CD | Surgery experienced or naïve |

n = 42 n = 40 had follow-up information |

Modified LIFT surgery (n = 42) | Mean 14.2 months | Moderate |

| El Rhaoussi 2019 | Gastroenterology and Proctology Dept, Casablanca, Morocco | Patients operated on for cryptoglandular non-specific CAF by LIFT technique at the study institution between April 2016 and October 2018 | Not reported | Surgery experienced or naïve | n = 28 | LIFT (n = 28) |

Median for healing outcome 12 weeks Mean for relapse outcome 18 months Duration not reported for incontinence outcome |

Moderate |

| Garg 2017 | Unnamed referral institute, Author’s affiliation is India |

All the consecutive patients operated in the study institution between January 2015 and July 2016 1. High cryptoglandular fistula-in-ano (involving > 1/3 of the sphincter complex as assessed on MRI scan and intraoperative examination under anesthesia) 2. Horseshoe fistula 3. Supralevator fistula |

1. Low fistula (involving < 1/3 of the sphincter complex) 2. Fistula-in-ano with CD |

Not reported | N = 61 (9 patients were excluded from analysis) | Transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) procedure (n = 61) | Median 9 (6–21) months | Moderate |

| Lau 2020 | Royal Prince Alfred Hosp, Sydney, Australia |

1. Patients who had LIFT and BioLIFT as their sentinel definitive repair of complex fistula-in-ano during the 10-year study period (January 2009 to June 2018) 2. Patients who had previously failed fibrin glue or fibrin plug, as the anatomy, and tissue planes within the anal sphincter complexes were not disrupted by previous surgery |

Non-cryptoglandular fistulas | Surgery experienced or naïve | n = 116 |

The intervention was LIFT and/or BioLIFT procedure LIFT as the primary procedure (n = 105). LIFT was primarily performed on patients with transsphincteric fistulas with associated low resting anal sphincteric pressures. 7 out of these 105 later received BioLIFT as the subsequent intervention BioLIFT as the primary procedure (n = 11). 1 out of these 11 patients received LIFT as the subsequent intervention |

Median 36.4 (7.1–234.3) weeks | Moderate |

| Schulze 2015 | The Townsville Hosp., Townsville Day Surgery Hosp., Mater Hosp Pimlico, Australia |

1. Consecutive patients treated with LIFT for complex anorectal fistula of cryptoglandular origin between May 2008 and June 2013 2. Patients with recurrent disease 3. Patients with failed anorectal advancement flap 4. Patients previously treated for the same condition by other surgeons |

1. Simple fistulas 2. Fistulas due to non-cryptoglandular etiology such as CD, radiation, or chronic infections such as tuberculosis and chronic diarrhea |

Surgery experienced or naïve | N = 75 patients |

LIFT (n = 75) including standard LIFT (n = 72) and 2 LIFT procedures performed simultaneously for multiple tracts (n = 3) |

Mean 14.6 months (standard error of the mean 1.7 months) | Moderate |

| Sun 2019 | Unnamed Institute, authors’ affiliation is China | All patients with HTFsb who underwent LIFT procedures between September 2012 and December 2017 were included |

1. Intersphincteric, low transsphincteric, suprasphincteric fistulas or HTFs with an intersphincteric extension 2. IBD 3. Tuberculosis 4. Immunological diseases 5. Patients lost to follow-up |

Surgery experienced or naïve | N = 70 patients (71 LIFT procedures) |

LIFT without prior loose setons (n = 70) Total number of LIFT procedures n = 71 |

Median 16.5 (4.5–68) months | Moderate |

| Wen 2018 | Suzhou Affiliated Hosp. of Nanjing Univ of Chinese Med |

1. > 18 years old 2. Complex cryptoglandular anal fistula with newly diagnosed fistula-in-ano 3. No significant abnormalities of external and internal sphincter in anorectal pressure measurement 4. Patient wants to be submitted to LIFT surgery and has signed the informed consent before the operation 5. Treated with modified LIFT in study institution between January 2013 and December 2016 |

1. Patient refused LIFT surgery and chose other surgical treatment 2. “No Crohn’s disease” 3. Another inflammatory bowel disease or malignancy |

Surgery naïve | N = 62 | Modified LIFT (n = 62) | Median 24.5 (12–51) months | Moderate |

| Ye 2015 | Dept of Colorectal Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang Univ, Hangzhou, China; Dept of General Surgery of the People’s Hospital of Deqing County; Huzhou, China |

Consecutive patients who underwent the modified ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (mLIFT) procedure in the study institution from June 2012 to March 2013 Patients who were deemed candidates for the mLIFT procedure were those who had an HTF, i.e., endoanal ultrasonic or MRI showed the tract crossing the external sphincter by 30% or more, and fistulotomy would place them at a high risk of incontinence |

1. Low transsphincteric fistulas 2. Suprasphincteric fistulas 3. Extrasphincteric fistulas 4. Patients with a rectovaginal fistula 5. Fistulae due to CD, tuberculosis, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

Not reported | n = 43 patients (4 patients were lost to follow-up) |

mLIFT (n = 39) Delayed mLIFT procedure (n = 4) |

Median 15 (12–24) months | Moderate |

3D-EAUS 3D endoanal ultrasound, AVF anovaginal fistula, CAF complex anal fistula, CCF complex cryptoglandular fistula, CD Crohn’s disease, HTF high transsphincteric fistula, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, FIPS fistulectomy and primary sphincteroplasty, LIFT ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract, MAF mucosal advancement flap, RAF rectal advancement flap, RVF rectovaginal fistula, STD sexually transmitted disease

aAnal fistulas are anatomically defined according to Parks’ classification. All high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and intersphincteric crossing > 30% of the external sphincter or horseshoe-shaped anal fistulas were classified as complex

bFistulas were classified according to Parks’ classification. An HTF was defined as the tract traversing above the subcutaneous external anal sphincter

Risk of Bias Assessment

Of the 18 included outcomes studies, 17 were cohort studies or case series that met the review definition for cohort studies. Of these, seven studies were prospective [11–17] and 10 were retrospective [18–27]. One study was a retrospective cross-sectional study [28]. Two papers [20, 21] were judged as having a serious risk of bias and 16 as having a moderate risk of bias (Table 1).

Epidemiology of CF

Two studies from the UK estimated incidence or prevalence of CF; a population-based study using The Health Improvement Network (THIN) UK primary care database estimated the prevalence of CF in patients without Crohn’s disease at 1.35/10,000 patients in 2017 in the UK, down from 1.83/10,000 patients in 2014. The standardized prevalence of CF in the EU in 2017 was 1.39 (1.26–1.52) per 10,000. The authors suggest that the declining fistula prevalence could be an artifact of a decline in active patients in the database [9]. Another study examined the incidence of anal fistula among patients with a hospital admission for anal abscess in the Hospital Episode Statistics database, an administrative data set with almost complete capture of all hospital episodes in England since its inception in 1987. The authors reported that 52.6% (95% CI 51.6% to 53.0%) of patients without inflammatory bowel disease progressed from anorectal abscess to fistula over 12 months [10]. No studies were identified estimating the incidence or prevalence of CCF specifically.

Clinical Outcomes of Selected Surgical Procedures for CCF

The studies identified in this review described clinical outcomes of healing, recurrence, FI, and pain following local surgical procedures and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF. Local surgical procedures included MAF (n = 6), fistulectomy (n = 3), FIPS, (n = 1), and modified Parks’ technique (n = 1). No studies were identified performing lay open fistulotomy. Intersphincteric ligation procedures included LIFT or BioLIFT (n = 7) and TROPIS (n = 1). Outcomes are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Selected outcomes of local surgical procedures for complex cryptoglandular fistulas

| Author, year | Exposure groups (patients with CCF only) | Key outcome definitions | Healing/success | Recurrence/failure | Fecal incontinence | Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anal flap (n = 6) | ||||||

| Boenicke 2017 | Advancement flap, n = 61 |

Primary healing: complete wound healing in combination with the absence of any symptoms like pain, bleeding, or secretion and inconspicuous transanal ultrasound findings at 6-month follow-up Fistula recurrence: a fistula or an abscess occurring after initial healing Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence Pain scale not defined |

3 months: primary healing 80.3%a (49/61) 6 months: primary healing 86.9%a (53/61) |

Recurrence 4.9%a (3/61) Overall therapy failure (including 8 patients with persistent wound secretion at 6 months, and 3 recurrent fistulas occurring at 9, 13, and 15 months) 18% (11/61) after a mean follow-up period of 25 months |

Wexner Scale of Incontinence In all patients: 1. Preoperatively (mean ± SD) 0.37 ± 0.91 points 2. At 6-month follow-up 0.46 ± 0.97 points. (p = 0.34) In the success group (n = 50): 1. Preoperatively (mean ± SD) 0.34 ± 0.90 points 2. At 6-month follow-up 0.38 ± 0.83 points. (p = 0.59) In the failure group (n = 11): 1. Preoperatively (mean ± SD) 0.4 ± 0.92 points 2. At 6-month follow-up 1.0 ± 1.44 points. (p = 0.14) There were no significant differences compared to the success group (p = 0.07) |

No scale reported 8.1% (5/61) patients suffered from postoperative stronger pain that was self-limiting and responsive to analgesics |

| Ding 2015 | Advancement flap, n = 38 |

Recurrence of fistula at 1 year (recurrence was not defined) Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence |

Not reported | Recurrence at 1-year follow-up 13.2%a (5/38) | Not reported by surgery type | Not reported |

| Emile 2018 | Anal advancement flap, n = 9 | Recurrence: clinical occurrence of the fistula after recovery of the surgical wound, occurring within 1 year after the procedure | Not reported |

Recurrence 44.4% (4/9) Disruption of flap: Total 55.5% (5/9) |

Not reported by surgery type | Not reported |

| Lee 2015 |

Advancement flap, n = 61, including: Endorectal advancement flap, n = 48 Anocutaneous advancement flap, n = 13 |

Healing/success is not defined Recurrence: persistent or new discharge, or any additional perianal fistula at the site of primary repair Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence |

Successful flaps in all patients: 86.9% (53/61); among these 53 patients, 92.5% (49/53) had uneventful healing and 7.5% (4/53) had delayed healing 50.0%a (4/8) of the 8 failed patients underwent subsequent surgery; among them, 1 had a successful LIFT |

Failed flaps/failure rate (also called “recurrence”) in all patients 13.1% (8/61) |

Among the 53 patients who had a successful outcome, 3 died from unrelated causes. In the remaining 50 patients, only 54.0%a (27/50) were contacted via telephone interview to assess their continence status using the Wexner Score of 0, 77.8% (21/27) Score 1–5, 14.8% (4/27); they only complained of mild disturbances to their life and the predominant symptom was infrequent suboptimal flatus control Score 11–13, 7.4% (2/27); both complained of inability to control even solid stools and frequent symptoms that affect their lifestyle |

Not reported |

| Podetta 2019 |

Group A MAF, n = 121 Group B MAFs, n = 32 Group C MAFs, n = 6 |

Success rate and recurrence not defined Functional status (incontinence) was evaluated by Miller score system |

1. Median time between the 1st and 2nd MAF 8 months (range 3–24 months) 2. Success rate after the 2nd MAF 78.1% (numbers for calculation not reported) 3. Median time between the 2nd and 3rd MAF 9.3 months (SD 5.8), with 83% of patients recurring in less than 1 year 4. Success rate after the 3rd MAF 100% (numbers for calculation not reported) |

1. Among complex anal fistula patients who underwent 1st mucosal advancement flap: Any recurrence 33.9%a (41/121), including 26.4%a (32/121) recurrences as complex anal fistulas (this is group B) 7.4%a (9/121) recurrence as simple anal fistula 2. Among complex anal fistula patients who underwent 2nd mucosal advancement flap (group B): Any recurrence 21.9%a (7/32), including 18.8%a (6/32) recurrences as complex anal fistulas (this is group C) 3.1%a (1/32) recurrence as simple anal fistula 3. 53.1% (17/32) patients in group B had the first recurrence during the first postoperative year 4. 83.3% (5/6) patients in group C had the first recurrence during the first postoperative year |

Functional status (incontinence) was evaluated by Miller score system proposed by Miller et al. in 1988. Self-reported fecal incontinence Group A (not reported) Group B At 3 months follow-up: 1 patient mentioned some gas incontinence scored at 2 1 patient presented a rare liquid stools leakage scored at 4 After MAF for recurrent anal fistula: Postoperative control showed unchanged degree of incontinence for both cases Group C After the 1st MAF: 1 patient suffered from rare gas incontinence scored at 1 After the 2nd and 3rd MAF: Incontinence score did not change in that patient |

Not reported |

| Schiano di Visconte 2018 | RAF group, n = 31 |

Healing: the complete reepithelization of the external opening, closure of the internal opening, and clinical absence of any drainage through the external or internal opening at 6 months postoperatively Recurrence: redischarge after complete healing at any point during observation Continence disorders (CGS ≤ 4) were defined in as the inadvertent escape of flatus or partial soiling of undergarments with liquid stool Fecal incontinence was defined as CGS ≥ 5 NRS used for pain, where 1 indicated no pain, and 10 indicated the worst pain imaginable |

1-year postoperative overall success rate 65% (20/31) 2-year disease-free survival/healing rate 65% (20/31) Outcomes among the patients with operative failures who underwent subsequent surgeries: After RAF failure, fistula closure was achieved in 80.0%a (4/5) patients who underwent subsequent surgeries Outcome after recurrences In RAF group, 50.0%a (3/6) of the 6 recurrent patients developed recurrence again after redo surgery and underwent a new operation (Note: surgery not identified). 100%a (3/3) were successful |

Recurrence rates at a median follow-up of 24 months 35% (11/31) Operative failure 16% (5/31); 3 of the 5 failures had flap disruption during the 1st week During the follow-up period, after excluding patients with operative failures, recurrence rate is 19% (6/31); 5 of the 6 recurrences occurred during the first 3 months postoperatively |

CGS Preoperatively CGS 1.6 ± 1.6, 1 (0–6)b Continence disorders 3% (1/31) Fecal incontinence 0% (0/31) 3 months postoperatively CGS 3.2 ± 2.7, 3 (0–8)b Continence disorders 16% (5/31) Fecal incontinence 16% (5/31) p value CGS 0.000 Continence 0.004 |

NRS where 1 indicated no pain, and 10 indicated the worst pain imaginable Preop 1.4 ± 0.6, 1 (1–3)b 3-month postop 1.2 ± 0.5, 1 (1–3)b Pain (NRS) p value 0.248 |

| Fistulectomy (n = 3) | ||||||

| Ding 2015 | Fistulectomy, n = 41 | Recurrence of fistula at 1 year (recurrence was not defined) | Not reported | Recurrence at 1-year follow-up 22.0%a (9/41) | Not reported by surgery | Not reported |

| Farag 2019 | One-stage fistulectomy and reconstruction, n = 173 |

Wound healing was not defined Recurrence of fistula was assessed after 1 year by clinical examination and MRI |

Delayed healing (more than 8 weeks) 1.7%a (3/173) Healing rate in the total population 100%a; except for the 3 patients with delayed healing, the rest of the patients had average time of wound healing around 3–4 weeks Note: The authors did not report 100% explicitly |

Recurrence rate after 1 year 8.1%a (14/173) | Not reported for patients with complex cryptoglandular fistula | Not reported |

| Visscher 2016 | Fistulectomy only, n = 28 | Recurrence: a persisting fistula requiring further surgery, or a new fistula seen during follow-up after apparent initial healing | Not reported |

Recurrence rate 61% Recurrence rate by follow-up time: 12 months 42% 24 months 56% 36 months 59% Note: Authors provided percentages only (no n’s or denominators) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty FIPS (n = 1) | ||||||

| Litta 2019 | FIPS, n = 103 |

Healing: the absence of drainage or abscess formation, fistula closure, and complete wound healing Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence, soiling, pad use Pain scale not defined |

Healing rate after a mean follow-up of 55.9 ± 30.9 (range 12–143) months 93.2% (96/103) | Not reported for complex CF |

Wexner Postoperative continence impairment 18.4% (19/103) |

No patients developed postoperative intractable pain |

| Modified Parks’ technique (n = 1) | ||||||

| El-Said 2019 | n = 32 |

Healing: measured at 6 months postoperatively Recurrence: clinical occurrence of the fistula after recovery of the surgical wound, occurring within 1 year after the original procedure of anal fistula Persistence: nonhealing and persistence of surgical wound for at least 3 months after surgery Wexner to assess fecal incontinence Pain assessed using Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2 |

Initial healing 93.8%a Subsequent healing 100%a Average time to complete healing 6.72 ± 1 (range 5–9) week Among the 2 patients with recurrent fistulas who were subsequently treated with draining seton, 100% (2/2) achieved complete healing after 3 months postoperatively with no recurrence on further follow-up |

Recurrence 6.3% (2/32) patients who had horseshoe fistula with supralevator extension Persistence 0% |

Wexner Fecal incontinence was evaluated before and after the surgery; specific time period not specified Preoperative median Wexner score 0 (range 0–17); Postoperative median Wexner score 0 (range 0–17) 3.1%a (1/32) patient had postoperative new-onset minor FI (Wexner score = 3) 6.3% (2/32) patients were preoperative incontinent: Post-hemorrhoidectomy fecal incontinence with Wexner score of 17, n = 1 Post-fistulectomy fecal incontinence with Wexner score of 12, n = 1 The 2 patients who had FI prior to surgery maintained their continence state after the surgery |

Bodily pain at 6 months after surgery was assessed by Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2: Before surgery 37.5 ± 9.3 After surgery 65.1 ± 7.2 |

CCF complex cryptoglandular fistula, CGS Continence Grading Scale, FI fecal incontinence, FIPS fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty, LIFT ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract, MAF mucosal anal flap, NRS Numeric Rating Scale, RAF rectal advancement flap

aCalculated value

bMean ± standard deviation, median (range)

Table 3.

Selected outcomes of intersphincteric ligation procedures for complex cryptoglandular fistulas

| Author, year | Exposure groups (patients with CCF only) | Key outcome definitions | Healing/success | Recurrence/failure | Fecal incontinence | Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIFT and BioLIFT (n = 7) | ||||||

| Deimel 2016 | 42; n = 40 had follow-up information; all had high transsphincteric fistula and had modified LIFT | Recurrence was not defined | Not reported |

Note: 95.2%a (40/42) patients had follow-up information, so the denominator changed from 42 to 40 Recurrence rate after mean follow-up time of 14.2 months 7.5% (3/40) All 3 recurrences occurred in female patients (recurrence rate 21%b vs 0%, P = 0.037) |

Not reported | Not reported |

| El Rhaoussi 2019 | LIFT, n = 28 |

Healing: absence of purulent discharge or proctalgia 3 months after surgery Relapse not defined Wexner to assess fecal incontinence |

Healing rate after a median follow-up of 12 weeks 57.1% (16/28) |

Of the 16 patients who healed, relapse rate after an average follow-up of 18 months 0% Of the other 12 patients, 42.9% (12/28) relapsed within 12 weeks |

No cases of anal incontinence were noted with a Cleveland score of 0 before and after the LIFT | Not reported |

| Lau 2020 |

Total n = 116 91%a (105/116) received LIFT as the primary procedure. LIFT was primarily performed on patients with transsphincteric fistulas with associated low resting anal sphincteric pressures. 7 out of these 105 later received BioLIFT as the subsequent intervention 9%a (11/116) received BioLIFT as the primary procedure. 1 out of these 11 patients received LIFT as the subsequent intervention |

Primary healing rate at 6 months: determined clinically by closure of external opening and the absence of clinical symptoms and radiologically by the discontinuity of fistula tract on endoanal ultrasound Secondary healing rates: conversion to intersphincteric fistula and subsequent fistulotomy Failure: fistulas that failed to heal (ongoing presence of external opening or persistence of fistula tract on endoanal ultrasound) or require other definitive procedures other than fistulotomy Incontinence scale not reported |

The p values between LIFT and BioLIFT are also reported: Total primary healing rate 60.3% (70/116) Primary healing rate in LIFT group 62.9% (66/105) Primary healing rate in BioLIFT group 36.4% (4/11); p value = 0.087 Total secondary healing rate 80.1% (93/116) in Table 2; BUT they reported 80.1% (n = 103) in the results Secondary healing rate in LIFT group 80.0% (84/105) Secondary healing rate in BioLIFT group 81.9% (9/11); p value = 0.886 In the 21 patients who had persistent transsphincteric fistula, 33.3%a (7/21) were treated successfully with a BioLIFT procedure |

Median time to primary failure in all 9.28 (range 1–160) weeks Median time to primary failure in LIFT 10.2 (range 1–55) weeks Median time to primary failure in BioLIFT 17.1 (range 9–160) weeks; p value = 0.121 Persistence failure in all 12.9% (15/116) Persistence failure in LIFT group 13.3% (14/105) Persistence failure in BioLIFT group 9.1% (1/11); no p value reported |

Postoperative self-reported Incontinence rate 0% |

Not reported |

| Schulze 2015 | n = 75 |

Success: healing of the external opening and intersphincteric incision with resolution of symptoms Recurrences classified as: Type 1, a residual sinus tract from the external opening Type 2, a downstaged tract from transsphincteric to intersphincteric fistula Type 3, a complete failure with the recurrent fistula tract extending from internal to external opening Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence Pain assessment not described |

No recurrence: Overall 88%a (66/75) Standard LIFT 91.7%a (66/72) 2 LIFT procedures performed simultaneously for multiple tracts 0%a (0/3) |

Overall recurrence rate 12% (9/75) Mean time to recurrence 9.2 months (SEM 2.7 months) Recurrence by intervention: Standard LIFT 8.3%a (6/72) 2 LIFT procedures performed simultaneously for multiple tracts: 100%a (3/3) p < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test |

Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence score (CCF-FI) Preoperative continence score (Wexner) mean 0.55, SEM 0.3 Postoperative continence score (Wexner) mean 0.60, SEM 0.3 No significant difference in preoperative and postoperative continence scores [mean 0.55 (range 0–11) vs mean 0.60 (range 0–11), p = 0.317] 1.3% (1/75) reported increased incontinence following LIFT with a change in continence score from 6 to 8 |

No scale or method of assessment mentioned Perianal pain 3% (2/75) |

| Sun 2019 | n = 70 |

Healing: cicatrization of the intersphincteric wound and the original external opening without discharge at 3 months Failure: persistence of any unhealed wound at 3 months Recurrence: purulent discharge was observed from any previously healed wound Relapse: a new fistula away from the healed one by LIFT Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence Fecal incontinence quality of life (FIQL) used for QoL |

Note: Total patients n = 70, total fistulas/total number of LIFT procedures n = 71 1. Healing rate after initial LIFT, after 12 months 81.7% (58/71) fistulas, without need for further intervention 2. Healing rate by maturity In mature fistulas 83.7% (41/49) In immature fistulas 77.3% (17/22) 3. Primary healing rate in patients who were followed more than 12 months (54 patients with 55 fistulas) 80% (44/55) 4. “The wound healed uneventfully” in 67.1%a (47/70) patients 5. Among the 12 fistulas that recurred as intersphincteric fistulas: 83.3%a (10/12) were successfully healed with fistulotomy 16.7% a (2/12) were asymptomatic and had no treatment 6. 1 failed high transsphincteric fistula (HTF) was healed with the loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation 7. 1 new low transsphincteric fistula relapsed 19 months after LIFT and was healed with fistulotomy |

Failure rate after initial LIFT 2.8%a (2/71) fistulas Recurrence 15.7%a (11/70) with a median to recurrence time of 5 (range 4–22) months 1 recurrence occurred after 12 months Recurrent fistulas were all downstaged to intersphincteric fistulas Relapse rate 1.4%a (1/70) |

Wexner score (range) Preoperatively 0 (0–2) Postoperatively 0 (0–1) p value 0.414 Incontinence of flatus (% of patients) Improvement after LIFT 5.7%a (4/70) New cases after LIFT plus fistulotomy 2.9%a (2/70) Note: Authors do not indicate whether these are mean or median scores |

Not reported |

| Wen 2018 | n = 62 had modified LIFT |

Success: complete healing of the surgical intersphincteric wound and the external opening without any sign of recurrence Failure: a clinical diagnosis of fistula recurrence at any time in the postoperative follow-up defined by clinical interview, physical examination Wexner used to assess fecal incontinence after the operation and in the end of the follow-up |

Success after first LIFT procedure 83.9% (52/62) Success after LIFT and second procedure 100%a (62/62) Fistulotomy 100%a (8/8; all male) Cutting seton 100%a (2/2; both female) Success for horseshoe fistula 62.5% (5a /8) |

Failure after LIFT 16.1% (10/62); median time interval to recurrence was 3 months (1–12) All recurrent fistulas became intersphincteric fistulas |

Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence (CCF-FI) mean score 0 Autonomous control of anal sphincter 100%a (62/62) Note: Not reported if this is pre- or postoperatively |

Not reported |

| Ye 2015 | Modified LIFT, n = 43 (4 patients were lost to follow-up and excluded from analysis; n = 39) |

Healing: complete wound healing in combination with the absence of symptoms Recurrence was not defined Wexner and Fecal Incontinence Severity Index were used to assess fecal incontinence before and at 6 months after the procedure |

Note: 4 patients were lost to follow-up and therefore excluded from analyses. The denominator decreased from 43 to 39 1. Closure rate, at the end of follow-up 87.2% (34/39) 2. Median time to healing 13 days (range 9–21 days) 3. Primary healing rate 71.8% (28/39) 4. Secondary healing rate 15.4% (6/39); they all had breakdown of the tissue seal with raw area and healed by dressing change 5. Healing rate among those 5 patients who received subsequent fistulotomy 100% (5/5) 6. Overall healing rate 100% (39/39) |

Recurrence rate 12.8%a (5/39); all 5 patients presented with an intersphincteric recurrence |

Median (range) Wexner incontinence scale Preoperatively 0 (0–20) Postoperatively 0 (0–20) Other patient-reported fecal incontinence: Fecal incontinence severity index: Preoperative 0 Postoperative 0 |

Not reported |

| Transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) | ||||||

| Garg 2017 | n = 61 (9 participants were excluded from analysis; n = 52) |

Healing: all the tracts are healed completely with no pus discharge from any of the tracts or the anus Failure: pus discharge from even a single tract Vaizey incontinence score used to assess fecal incontinence |

Healing rate after 1 surgery 84.6% (44/52) Overall healing rate 90.4% (47/52) after 2 surgeries (3 out of 4 patients who had a reoperation healed completely) |

15.4% (8c/52) did not heal after 1 surgery |

Vaizey Incontinence Score Preoperative incontinence scores 0.19 ± 0.4 Postsurgery after 3 months 0.32 ± 0.6 |

Not reported |

CCF complex cryptoglandular fistula, LIFT ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract, SEM standard error of the mean

aCalculated value

bNumbers for calculation not reported

cMiscalculated as 9 in the paper

Fistula Healing (Surgical Success)

Fourteen of 18 studies (seven local surgical and seven intersphincteric ligation studies) reported on fistula healing, or “success” of the intervention. Definitions of these outcomes varied (see Tables 2 and 3); however, many authors defined healing as closure of the opening, healing of the wound, and absence of purulent discharge. Primary healing rates, or the healing rate after the initial intervention of interest without follow-up intervention, in the three studies of MAF reporting this outcome ranged from 65.0% at 1 year in a mix of 31 surgery-experienced and surgery-naïve patients to 86.9% after 6 months in 61 surgery-experienced patients [11, 20, 23]. In another study of 121 patients with a median duration of 74 months (range 8–148 months), patients underwent up to two additional MAFs, until a 100% healing rate was reached [22].

One study reported that 100% of 173 patients healed after fistulectomy, and most patients (168/173) healed within 3–4 weeks. Healing rates were reported for FIPS in one study [21], where 93.2% of 103 patients healed after a mean follow-up of 55.9 months. The authors of these two studies did not report whether the patients were surgically naïve or experienced. One study that assessed healing after modified Parks’ technique reported initial healing in 93.8% of 32 surgery-naïve or surgery-experienced patients with subsequent healing at 100% after a median of 12 months (range 4–24 months) [13].

For LIFT/BioLIFT procedures, primary healing occurred in a range of 57.1% after a median of 12 weeks in a mix of 28 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients to 88% after a mean of 14.6 months (standard error 1.7 months) in a mix of 75 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients [15, 19, 24–26]. Healing after initial TROPIS surgery was reached in 84.6% of 61 patients after a median of 9 months (range 6–21 months) in one available study. Including patients who underwent a second TROPIS procedure, the overall healing rate increased to 90.4% [16]. The authors did not report whether these patients were surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve.

Fistula Recurrence/Failure (Surgical Failure)

Seventeen papers reported on fistula recurrence or treatment failure and demonstrated a wide range of findings. The authors defined these outcomes in various ways (see Tables 2 and 3); some authors equated intervention “failure” with “recurrence,” and some reported results separately for these outcomes. Many authors defined recurrence as the clinical occurrence of the fistula, an abscess, or purulent discharge after recovery of the surgical wound within various time periods. In studies of the MAF procedure, recurrence occurred in 4.9–44.4% of patients [11, 12, 18, 20, 22, 23]. Boenicke et al. reported recurrence in three surgery-experienced patients (3/61, 4.9%), one each taking place at 9, 13, and 15 months [11]. Emile et al. reported recurrence in a mix of four surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients (4/9, 44.4%) within 1 year of their procedure [18]. Three studies [11, 18, 23] also reported separate failure or disruption of flap rates that ranged from 16% (5/31; three of which occurred within the first week) to 55.5% (5/9 within 1 year of the procedure) of patients [18].

Recurrence rates after fistulectomy ranged from 8.1% (at 1-year follow-up among 175 patients whose surgery experience was not reported) to 60.7% (after a median follow-up period of 26 months [range 2–118 months] among 28 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients) [12, 14, 28]. One study of the modified Parks’ technique reported recurrence after a median of 12 months (range 4–24 months) follow-up in 6.3% of 32 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients who had horseshoe fistula with supralevator extension [13]. The single study of FIPS did not report recurrence rates for patients with CCF [21].

Among studies reporting intersphincteric ligation procedures, recurrence occurred in a range of 7.5% (3 of 40 surgery-experienced and surgery-naïve patients after a mean of 14.2 months follow-up) [17] to 42.9% (12 of 29 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients relapsed within 12 weeks) [15] of patients receiving LIFT/BioLIFT [15, 17, 24, 25, 27]. Treatment failure was experienced in 2.8% (2 of 71 surgery-experienced or surgery-naïve patients after 12 months) [25] to 16.1% (10 of 62 surgery-naïve patients after a median of 24.5 months; range 12–51 months) [26] of patients [19, 25, 26]. The single study of TROPIS did not report recurrence or failure rates [16].

Fecal Incontinence

Tables 2 and 3 indicate the scales and definitions of FI used in each paper. Two of the four studies reporting on FI following MAF procedures did so using the Wexner score, which ranges from 0 (perfect functionality) to 20 (complete incontinence) [29]. Boenicke et al. reported Wexner scores of 0.46 ± 0.97 points at patients’ 6-month follow-up [11]. Lee et al. reported a Wexner score of 0 in 77.8% of patients, 14.8% had a score of 1–5, and 7.4% had a score of 11–13 [20]. Podetta et al. reported FI using the Miller scoring system with range 0–18, with higher numbers representing more frequent incontinence-related symptoms [22, 30]. Of 32 patients who received a second mucosal flap, two patients reported incontinence symptoms. Of patients who received two additional MAF procedures, one patient reported rare gas incontinence after the first MAF and no change in incontinence scores with the subsequent procedures.

One study reported Wexner-identified incontinence in 18.4% of patients with CCF following the FIPS procedure [21]. In El-Said et al., postoperative new-onset minor FI (according to the Wexner score) was reported in 3% of patients following modified Parks’ technique. None of the studies of fistulectomy reported FI by surgery type and for patients with CCF [13].

Seven of eight studies of intersphincteric ligation procedures reported on the outcome of FI. In studies of LIFT and BioLIFT, five studies used Wexner scoring and three used patient-reported scales, including the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQL) and the Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI). FI was reported in 0% of patients in two studies [15, 26] using Wexner scoring, and in one study using a self-reported scale [19] (scale name not reported). Ye et al. reported no incontinence in patients postoperatively by Wexner score and FISI [27]. Schulze et al. reported increased incontinence in 1.3% of patients following LIFT [24]. Sun et al. reported improvement in Wexner scores for flatus incontinence after LIFT in 5.7% of patients, and significant improvements in lifestyle, coping, and depression domains of the FIQL [25].

In the one study that reported on TROPIS [16], the authors used the Vaizey incontinence score with a range of 0 (perfect continence) to 24 (complete incontinence) and reported mean scores of less than 1 with no significant change in scores pre- and postoperatively.

Pain

Few studies reported pain as a clinical outcome. The majority used a mix of clinician-reported and patient-reported scales and measured postoperative pain versus perianal pain specifically. One of the two studies of MAF procedures reported that 8.1% (5/61) of patients had experienced postoperative pain that was self-limiting and responsive to analgesics 30 days post-procedure [11]. The scale used in this study was not reported. The second study of MAF used the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) (1 = no pain; 10 = worst pain imaginable). The mean score did not increase significantly postoperatively (mean score preoperatively 1.4 ± 0.6 vs 3 months postoperatively 1.2 ± 0.5) [23]. One study [21] reported on pain following FIPS and noted that no patients developed postoperative intractable pain after a mean of 55.9 months (range 12–143 months). Using the Short Form-36 Health Survey, version 2, where each item is scored on a range of 0–100 and higher scores indicate more favorable health states, El-Said et al. reported a preoperative mean pain score of 37.5 ± 9.3 and 6-month postoperative mean score of 65.1 ± 7.2 following modified Parks’ technique [13].

Only one study reported on perianal pain associated with intersphincteric ligation procedures. Perianal pain was experienced in 3% of patients following LIFT [24].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first SLR reporting the incidence/prevalence of CF and outcomes associated with local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF. CCF are more difficult to treat than simple CF, resulting in higher failure rates and functional disability [31]. Treatments that heal CCF and reduce recurrence could provide hope for patients experiencing the substantial physical and social impacts of this condition [6]. Limited real-world evidence exists on CCF, and there is a need to critically evaluate and assess existing epidemiological data. We therefore summarized outcomes of fistula healing, recurrence/failure, FI, and pain following specific CCF interventions.

The important finding from this SLR is that in studies of local surgical or intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF, primary healing rates were 57.1–100.0%, indicating a moderate degree of initial success in these patients. Another critical finding was that recurrence and treatment failure were reported in 4.9–60.7% and 2.8–18.0% of patients, respectively. The imprecision of these estimates suggest a need for standardization in the reporting of outcomes to better assess the risks and benefits of individual treatment approaches. The limited number of publications that report on postoperative FI and postoperative pain suggests these outcomes are rare after the procedures highlighted in this study. Many of these studies were indicative of no long-term incontinence and no long-term postoperative pain.

Notable strengths of the current review include compliance with established guidelines for SLRs inclusion of a pre-specified protocol and search criteria. Selection, data extraction, and adjudication of risk of bias were done by two independent reviewers. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO to promote transparency and allow for future replication or updates and was conducted by two independent reviewers.

A major limitation of the current review is that it does not include studies published after March 25, 2020 to the present. New studies have been published in the past 3 years (e.g., for TROPIS, select newer publications include Li et al. 2022 [32], Huang et al. 2021 [33], Garg et al. 2021 [34], and Jayne et al. 2021 [35]) and it is unknown how this additional body of literature would impact any conclusions in the current manuscript. Future updated reviews in this area should be explored. Other limitations include at least a moderate risk of bias in all the included studies. Several studies were limited by single-center design with small sample sizes and short follow-up durations. Although this review was designed to capture a wide range of literature, it was limited to English-language studies from the past 5 years and hence might not be representative of the full body of published literature. Additionally, identified publications reported various study designs, follow-up durations, and definitions of key outcomes, making comparisons between studies infeasible.

Conclusion

Despite limitations, this SLR provides a unique critical summary of available data and highlights evidence gaps that can be addressed with further research. Specifically, there is a need for global observational studies on the incidence/prevalence of CF and CCF. Furthermore, the available literature lacks consistent approaches for assessing outcomes which could be used to facilitate comparison of treatment approaches. This SLR provides a comprehensive and critical summary of published epidemiology of CF and healing, recurrence/failure, incontinence, and pain outcomes from local surgical and intersphincteric ligation procedures for CCF. Success rates vary by surgery type, and differences in treatment indication, population, duration, or other aspects of study design prevent direct comparison. However, reported overall healing rates indicate the potential for relief from the substantial burden of CCF with low-to-modest rates of recurrence and rare reports of long-term postoperative incontinence or long-term postoperative pain.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee were funded in full by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Sydney Thai, Sapna Rao, Courtney Schlusser, and Kamika Reynolds conducted the abstraction and quality assessment and provided valuable consultation for the writing of this manuscript. Oxford PharmaGenesis provided editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Authors’ Contributions

Kristy Iglay, Dimitri Bennett, Michael D Kappelman, Chitra Karki, and Suzanne F Cook contributed to the study conception, and all authors contributed to the study design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kristy Iglay, Xinruo Zhang, and Molly Aldridge, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Portions of this work were presented in poster form at the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization 2021 virtual congress in July 2021.

Disclosures

Kristy Iglay, Molly Aldridge, Suzanne F Cook and Xinruo Zhang consulted on this project through CERobs Consulting, LLC, which received funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International Co. to perform the systematic literature review. Michael D Kappelman has consulted for Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals, is a shareholder in Johnson & Johnson and has received research support from Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celtrion, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dimitri Bennett and Chitra Karki are employees of Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited and receive stock/stock options. Suzanne F Cook was a consultant to CERobs Consulting, LLC previously and is now an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited and receives stock.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data availability

All data generated in this study is provided in the results and/or in the supplementary material file.

Contributor Information

Kristy Iglay, Email: kristy.iglay@laylen.com.

Dimitri Bennett, Email: Dimitri.Bennett@Takeda.com.

References

- 1.Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of anorectal abscess, fistula-in-ano, and rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:1117–1133. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson JA, Banerjea A, Scholefield JH. Management of anal fistula. BMJ. 2012;345:e6705. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks AG. Pathogenesis and treatment of fistuila-in-ano. Br Med J. 1961;1:463–469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5224.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abcarian H. Anorectal infection: abscess-fistula. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:14–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteford MH. Perianal abscess/fistula disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20:102–109. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-977488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen HA, Buchanan GN, Schizas A, Cohen R, Williams AB. Quality of life with anal fistula. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:334–338. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hokkanen SR, Boxall N, Khalid JM, Bennett D, Patel H. Prevalence of anal fistula in the United Kingdom. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:1795–1804. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahnan K, Askari A, Adegbola SO, et al. Natural history of anorectal sepsis. Br J Surg. 2017;104:1857–1865. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boenicke L, Karsten E, Zirngibl H, Ambe P. Advancement flap for treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistula: prediction of therapy success or failure using anamnestic and clinical parameters. World J Surg. 2017;41:2395–2400. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding JH, Bi LX, Zhao K, et al. Impact of three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound on the outcome of anal fistula surgery: a prospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:1104–1112. doi: 10.1111/codi.13108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Said M, Emile S, Shalaby M, et al. Outcome of modified Park's technique for treatment of complex anal fistula. J Surg Res. 2019;235:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farag AFA, Elbarmelgi MY, Mostafa M, Mashhour AN. One stage fistulectomy for high anal fistula with reconstruction of anal sphincter without fecal diversion. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:792–796. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Rhaoussi ZF, Hind H, Mohamed JT, et al. Evaluation of the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract in the management of complex anal fistulas. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:S378–S378. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg P. Transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) - A new procedure to treat high complex anal fistula. Int J Surg. 2017;40:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deimel S, Daichin D, Iesalnieks I. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) to treat high transsphincteric fistula: results of modified technique. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(Suppl 1):114. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emile SH, Elgendy H, Sakr A, et al. Gender-based analysis of the characteristics and outcomes of surgery for anal fistula: analysis of more than 560 cases. J Coloproctol. 2018;38:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jcol.2018.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau YC, Brown KGM, Cheong J, Byrne C, Lee PJ. LIFT and BioLIFT: a 10-year single-centre experience of treating complex fistula-in-ano with ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract procedure with or without bio-prosthetic reinforcement (BioLIFT) J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:671–676. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CL, Lu J, Lim TZ, et al. Long-term outcome following advancement flaps for high anal fistulas in an Asian population: a single institution's experience. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litta F, Parello A, De Simone V, et al. Fistulotomy and primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula: long-term data on continence and patient satisfaction. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:993–1001. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-02093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podetta M, Scarpa CR, Zufferey G, et al. Mucosal advancement flap for recurrent complex anal fistula: a repeatable procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:197–200. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiano di Visconte M, Bellio G. Comparison of porcine collagen paste injection and rectal advancement flap for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas: a 2-year follow-up study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Schulze B, Ho YH. Management of complex anorectal fistulas with seton drainage plus partial fistulotomy and subsequent ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun XL, Wen K, Chen YH, Xu ZZ, Wang XP. Long-term outcomes and quality of life following ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for high transsphincteric fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:30–37. doi: 10.1111/codi.14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen K, Gu YF, Sun XL, et al. Long-term outcomes of ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract for complex fistula-in-ano: modified operative procedure experience. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2018;31:e1404. doi: 10.1590/0102-672020180001e1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye F, Tang C, Wang D, Zheng S. Early experience with the modificated approach of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for high transsphincteric fistula. World J Surg. 2015;39:1059–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visscher AP, Schuur D, Slooff RA, et al. Predictive factors for recurrence of cryptoglandular fistulae characterized by preoperative three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:503–509. doi: 10.1111/codi.13211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forte ML, Andrade KE, Butler M. Treatments for fecal incontinence. Comparative effectiveness review, No. 165. Table E, Common fecal incontinence outcome measures. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356093/table/appe.t1/. Accessed 22 June 2021.

- 31.Bubbers EJ, Cologne KG. Management of complex anal fistulas. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:43–49. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YB, Chen JH, Wang MD, et al. Transanal opening of intersphincteric space for fistula-in-ano. Am Surg. 2022;88(6):1131–1136. doi: 10.1177/0003134821989048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang B, Wang X, Zhou D, et al. Treating highly complex anal fistula with a new method of combined intraoperative endoanal ultrasonography (IOEAUS) and transanal opening of intersphincteric space (TROPIS) Videosurgery Miniinv. 2021;16(1):697–703. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2021.104368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garg P, Kaur B, Menon GR. Transanal opening of the intersphincteric space: a novel sphincter-sparing procedure to treat 325 high complex anal fistulas with long-term follow-up. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(5):1213–1224. doi: 10.1111/codi.15555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jayne DG, Scholefield J, Tolan D, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of the surgisis anal fistula plug versus surgeon's preference for transsphincteric fistula-in-ano: the FIAT trial. Ann Surg. 2021;273(3):433–441. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study is provided in the results and/or in the supplementary material file.