Introduction

Indications for tooth autotransplantation include impacted or ectopic teeth associated with developmental dental–craniofacial anomalies, premature and traumatic tooth loss, and replacement of teeth with a bad prognosis [1].

This report describes the successful clinical management of an immature impacted mandibular premolar associated with a unicystic ameloblastoma. Seven-year follow-up findings revealed lesion healing with no recurrence and successful autotransplantation.

Materials and Methods

In May 2014, a 12-year-old patient presented to the dental clinic for an orthodontic consultation. The clinical examination revealed a retained primary mandibular second molar and an absent permanent second premolar. A CBCT was requested for a more thorough analysis and revealed that the impacted tooth was immature, in a buccoversion direction, and associated with a large radiolucent lesion around 1 cm in its largest diameter.

The patient had an IANB anesthesia using 4% articaine hydrochloride with 1:200,000 adrenaline (Artinibsa, Inibsa, Barcelona, Spain). An envelope flap was elevated to expose the impacted tooth. A Warwick James straight elevator (Nova, Berkshire, UK) carefully luxated the impacted tooth to avoid its rotation or potential damage to Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath. Once extracted, the tooth was immediately placed in sterile physiological saline, while the osteotomy site was prepared for transplantation. The lesion was enucleated using a sharp bone curette (Nova, Berkshire, UK) and sent for biopsy. A slightly oversized osteotomy of the recipient alveolar socket was prepared using consecutive implant drills (Implant direct, California, USA). The tooth was passively placed in the prepared socket and fixed to the adjoining teeth with a flexible fishing wire splint to allow for physiological movement (Fig. 1). The flap was closed using 4–0 vicryl stitches (Assut, Lausanne, Switzerland). The patient was instructed to take Amoxicillin/Clavulanate 625 mg (GSK, Brentford, UK) every 8 h for seven days and Ibuprofen 400 mg (Abbott, Illinois, USA) in case of pain. The lesion was sent to a pathology laboratory for histopathological examination and was identified as an intraluminal unicystic ameloblastoma. After two weeks, the stitches and splint were removed. The patient was scheduled for clinical and radiographic follow-up examinations every month for six months, and then, yearly until now seven years after the procedure, clinical and radiographic findings revealed lesion healing with no recurrence. The transplanted premolar is periodontally stable, responding positively to thermal and electric pulp tests. Radiographically, there is evidence of apical closure, and continued root development with a favorable crown–root ratio (Fig. 2A–B).

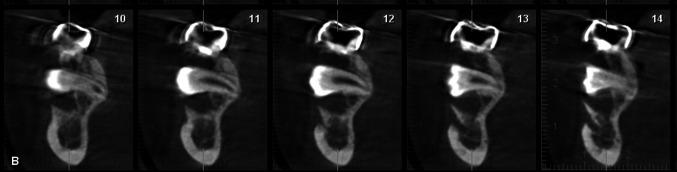

Fig. 1.

Coronal sections showing the impacted lower second premolar area surrounded by 1 cm radiolucency

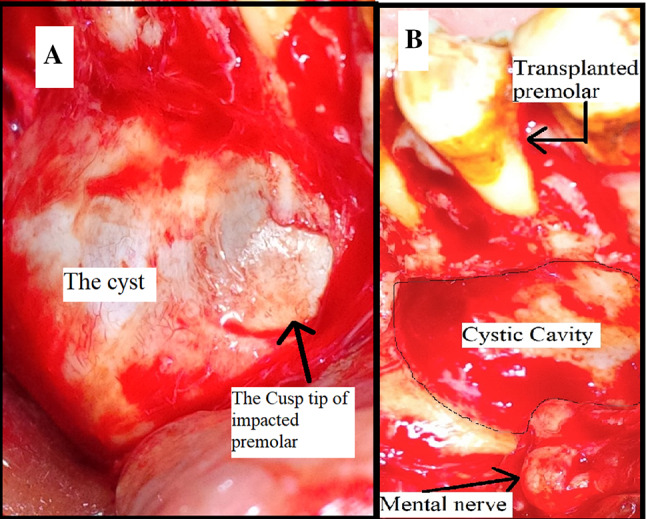

Fig. 2.

A Intraoral intraoperative image showing the cystic lining of the ameloblastoma and cusp tip of impacted premolar. B Intraoral intraoperative image showing the cystic cavity, mental nerve, and the teeth placed in their final location

Discussion

Unicystic ameloblastoma often affects the posterior mandible in young populations. It is characterized by a relatively benign biological behavior and responds well to conservative management [2].

Dental autotransplantation presents a series of advantages, such as maintaining a vital periodontium, allowing continuous growth, preserving the alveolar bone volume, preserving periodontal (PDL) proprioception, and conserving the interdental papilla [3].

The successful outcome of this case report can be attributed to several prognostic factors, the most important of which is the stage of root development of the transplanted tooth. Jakobsen et al. [4] reported that optimal outcomes for autotransplantation are achieved when two-thirds or three-quarters of the root have been formed (Fig. 3).

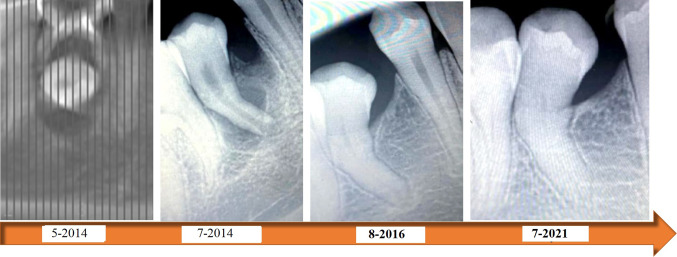

Fig. 3.

A series of periapical radiographs showing the closure of the apex post autotransplantation through the 7 years of follow-up

A vital PDL allows the formation of bone essential for healing and avoids the sequelae of ankylosis or root resorption [5]. This was achieved in this case by the atraumatic extraction for the impacted tooth.

Other related factors include the size of the recipient alveolus, alveolar bone volume and quality, the extra-alveolar time and storage of the transplant, and its stabilization [6]. For this case report, the transplant had adequate bony support from the lingual, mesial, and distal aspects, and there was no need for additional stabilization by placing a buccal graft.

Regarding the extra-alveolar time, it was about 8 min, during which the tooth was kept in a suitable storage media to preserve the vitality of Hertwig’s epithelial sheath and SCAP.

Stabilization of the transplant is of utmost importance during the healing phase. However, there is controversy about the material to be used and the duration of splinting. Long-term firm fixation may have adverse effects on healing, whereas non-rigid fixation for 7–10 days stimulates the activation of the alveolar ligament cells and bone healing [7]. In our case, the fixation was removed after two weeks when no vertical mobility was observed.

Few cases reports in the literature [8–10] described the successful autotransplantation of impacted teeth associated with pathologic lesions that were mostly dentigerous cysts with shorter follow-up periods.

Conclusion

Autotransplantation should be strongly considered a favorable therapeutic option for immature impacted teeth associated with pathologic lesions.

Acknowledgements

The authors whose names are listed immediately below certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements) or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge, or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Author contribution

All authors who have contributed to the research outcome have approved the version of a research publication to be published.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amgad Hassan Soliman, Email: amgad.hassan@fue.edu.eg.

Hesham Sharara, Email: Heshamsharara@asfd.asu.edu.eg.

Yasser Nabil El Hadidi, Email: yasserelhadidi@asfd.asu.edu.eg.

Shehabeldin Mohamed Saber, Email: Shehabeldin.saber@bue.edu.eg.

References

- 1.Chung WC, Tu YK, Lin YH, Lu HK. Outcomes of autotransplanted teeth with complete root formation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(4):412–423. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura N, Higuchi Y, Mitsuyasu T, Sandra F, Ohishi M. Comparison of long-term results between different approaches to ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2002;93(1):13–20. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.119517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong D, Itskovich Y, Dance G. Autotransplantation: a viable treatment option for adolescent patients with significantly compromised teeth. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(4):396–407. doi: 10.1111/adj.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakobsen C, Stokbro K, Kier-Swiatecka E, Ingerslev J, Thorn JJ. Autotransplantation of premolars: does surgeon experience matter? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(12):1604–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukiboshi M, Yamauchi N, Tsukiboshi Y. Long-term outcomes of autotransplantation of teeth: a case series. J Endod. 2019;45(12):S72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.PecciLloret MP, Martínez EP, Rodríguez Lozano FJ, PecciLloret MR, Guerrero Gironés J, Riccitiello F, Spagnuolo G. Influencing factors in autotransplantation of teeth with open apex: a review of the literature. Appl Sci. 2021;11(9):4037. doi: 10.3390/app11094037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagne S, Thilander B. Transalveolar transplantation of maxillary canines. A follow-up study. Eur J Orthod. 1990;12(2):140–147. doi: 10.1093/ejo/12.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajanikanth BR, Prasad K, Vineeth K. Autotransplantation of teeth associated with dentigerous cyst: a case report. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):816–820. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0699-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee BK. Poster 169: long-term follow-up study of autotransplanted teeth involved in dentigerous cysts in growing patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(9):43–e96. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim JH, Huh JK, Park KH, Shin SJ. Autotransplantation of an impacted premolar using collagen sponge after cyst enucleation. J Endod. 2015;41(3):417–419. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]