Abstract

Introduction

Over the past few years, stem cells have represented a promising treatment in neurological disorders due to the well-defined characteristics of their capability to proliferate and differentiate into any cell type, both in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, previous studies have shown that calcium signaling modulates the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells. The present study investigated the effect of carbachol (CCh), a cholinergic agonist activating acetylcholine receptors, with and without calcium, on the neural differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hADSCs) in neural media, including forskolin and 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine and retinoic acid.

Methods

For this purpose, first, the MTT assay and acridine orange staining were studied to obtain the optimal concentration of CCh. Next, the differentiation tests, such as cellular calcium assay as well as evaluation of qualitative and quantitative expression of neuronal index markers through immunofluorescence staining and gene expression analysis, respectively, were performed on days 7 and 14 of the differentiation period.

Results

According to the results, CCh at 1 μM concentration had no cytotoxicity on hADSCs and also induced cell proliferation. Furthermore, CCh with and without calcium increased the expression of neural-specific genes (NSE, MAP2, β–III–tubulin, and MAPK3) and proteins (γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin) as well as the amount of calcium in differentiated hADSCs at 7 and 14 days after induction.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings suggest that CCh acts as an influential therapeutic factor in the field of neural regenerative medicine and research.

Keywords: Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells, Calcium, Carbachol, Neural differentiation, Tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, neurodegenerative diseases have led to severe challenges which impact the life quality of patients and societies. Specific neurons, including motor and dopaminergic neurons, progressively degrade in neurodegenerative disorders, leading to a particular pattern of nervous system dysfunction and eventual death [1]. Stem cell technology provides a treatment source in neural regeneration and assists functional restoration by the differentiation of various kinds of stem cells into neurons and glial cells [2]. Due to their multipotent and self-renewal properties, stem cell transplantation has shown to be a promising therapeutic strategy [1]. Different populations of stem cells have been isolated from various body parts that possess the ability to self-renewal and have multilineage differentiation in vitro.

Several types of stem cells have been studied for their compatibility in neural regenerative medicine, including adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs). The simplicity of accessibility to adipose tissue with minimally invasive surgeries, the easy isolation methods, and the high proliferation capacity of stem cells achieved through patients of all ages outline ADSCs as promising sources over the other types of stem cells [3]. The ADSCs present the remarkable ability to differentiate towards neuron-like cells in vitro by activating specific molecular pathways [4]. It was reported that ADSCs isolated from rats or humans could be converted into neuron-like cells expressing neural markers after exposure to combinations of various growth factors or chemicals [5]. Over the years, several methods were suggested for the differentiation of ADSCs into cells with neuronal morphology, but determining the most reliable and efficient protocol is the first stage in regenerative medicine studies.

A growing number of reports have shown that various factors have the potential to differentiate various kinds of stem cells into functional neuronal cells. Forskolin and IBMX were demonstrated to stimulate adenylate cyclase activity and increase cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [6].

Additionally, increased intracellular cAMP has been reported to induce the differentiation of various stem cells into early progenitors of neural cells [7,8]. Furthermore, numerous evidences have shown that retinoic acid activates the signals related to cellular differentiation as well as pattern formation in vertebrate embryogenesis, such as the nervous system development [9].

Acetylcholine (ACh) is synthesized and released by cholinergic neurons. This neurotransmitter acts as one of the essential effectors of the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system through two receptors: the nicotinic and muscarinic ACh receptors (nAChRs and mAChRs) [10,11]. ACh is reported to be produced in the early steps of motor neuron development; therefore, this neurotransmitter plays an essential role in directing the early events of neuron interaction [12]. Carbachol (CCh), as a stable muscarinic agonist, is artificially synthesized and acts through increasing intracellular calcium, a response pathway activated by natural in vivo stimuli [13]. Despite ACh, important features of CCh are stability to hydrolysis and low toxicity [14]. Furthermore, cellular calcium signals regulate almost stages of neural development, such as neural induction, proliferation, and differentiation [15].

There is a wide range of neuronal genes related to the neuronal lineage being studied, such as neuron-specific enolase (NSE), microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), β–III–tubulin, and MAPK3 [16].

For the first time, the current study was performed to examine the CCh effects as an inducer for neural differentiation of human ADSCs (hADSCs). Moreover, the calcium effects along with CCh also were measured in this type of stem cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

The hADSCs were purchased from the cell bank of the Stem Cells Research Center (Tehran, Iran). Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all from Gibco Grand Island, NY, U.S.A) were used to culture hADSCs. Cells were kept in an incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.2. Human ADSCs viability in the presence of carbachol

The cytotoxicity effects of CCh on hADSCs viability and proliferation were assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma–Aldrich) assay. Briefly, 104 cells were cultured in a 96-well plate and followed by exposing different concentrations of CCh. On the 1st, 3rd, and 5th days of treatment, 100 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT solution (10 μl MTT and 90 μl DMEM) was poured into wells followed by a 4-h incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Then MTT was removed and wells were treated with 100 μl DMSO (Merck, Germany) to dissolve formazan crystals. The cell viability of hADSCs was measured through absorbance at 570 nm in a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA).

Additionally, to investigate the cell viability of hADSCs qualitatively, acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB, Sigma) staining was performed. At 1, 3, and 5 days after treatment, hADSCs were followed by an incubation at 37 °C with AO/EB (1 μl staining solution contains 100 g/mL AO and 100 g/mL EB) for 30 min. Finally, cells stained with AO/EB were investigated under a fluorescence microscope (Leica Inc., Foster City, CA).

2.3. In vitro neural induction of human ADSCs

For neural differentiation, the hADSCs were incubated in DMEM, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and various concentrations of FBS (10, 5 and 2% during 1–4, 5–10 and 11–14 days of differentiation, respectively) along with neural induction media, including 2/5 mM IBMX, 2/5 mM forskolin, 2/5 μM RA and divided to four groups, control or tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS), CCh (1 μM), CCh in the presence of 2.5 μM calcium (CCh-Ca) [17], and calcium groups for 14 days. The neural differentiation of hADSCs was then evaluated through molecular and immunocytochemical analyses on days 7 and 14 of induction.

2.4. Calcium content assay

The amount of calcium in hADSCs under neural induction was assessed using a calcium assay kit (Parsazmun, Tehran, Iran). To extract calcium from wells, 0.6 mol/L hydrochloric acid (Merck) was used and shaken for 4 h at 4 °C. After adding the reagent of the kit to the wells, optical density was assessed at 570 nm. Calcium deposition was evaluated from a standard concentration curve of serial dilutions versus corresponding OD.

2.5. Evaluation of protein expression by immunocytochemical technique

On the 7th and 14th days after induction, cells on wells containing TCPS, CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, USA) for 20 min. Human ADSCs were then permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X100 in PBS for 10 min 5% goat serum/PBS-tween-20 was used to incubate fixed cells for 30 min at 37 °C. Human ADSCs were then reacted overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies, including γ-enolase (1:100 Santa Cruz Biotechnology), MAP2 (1:300 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, INC), and β–III–tubulin (1:50 Chemicon) diluted in PBS/0.2% (v/v) bovine serum albumin. After incubation, the cells were rinsed three times with PBS tween-20 (0.1%). The hADSCs were incubated with the secondary antibody, phycoerythrin PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:100 Sigma), for 1 h at room temperature. DAPI (Sigma) was used to color the nuclei and images were prepared with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan). The quantitative assessment of the immunocytochemical intensity of γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin was done using image analysis software (ImageJ).

2.6. Real-time RT-PCR

On the 7th and 14th days of neural induction, MAPK3, β–III–tubulin, NSE, and MAP2 were used to quantify the difference among mRNA levels of key neural genes. Total RNA was extracted from cultured hADSCs using Trizol reagent (Gibco) and cDNA was synthesized using Revert Aid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (GeneAll, Seoul, Korea). Real-time PCR was carried out through Maxima TM SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (GeneAll) followed by melting curve analysis to confirm PCR specificity. Each reaction was repeated three times and an average threshold cycle was applied for analysis by Rotor-gene Q software (Corbett, Australia). The PCR primers picked out are listed in Table 1. Target genes were normalized against HPRT1 and calibrated to TCPS.

Table 1.

Primers used in RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR analysis.

| Gene | Forward(F) Reverse(R) |

Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| NSE | F: GGAGAACAGTGAAGCCTTGG R: GGTCAAATGGGTCCTCAATG |

238 |

| MAP-2 | F: AGTTCCAGCAGCGTGATG R: CATTCTCTCTTCAGCCTTCTC |

95 |

| β–III–tubulin | F: GATCGGAGCCAAGTTCTG R: GTCCATCGTCCCAGGTTC |

178 |

| MAPK3 | F: ATGTCATCGGCATCCGAGAC R: GGATCTGGTAGAGGAAGTAGCA |

198 |

| HPRT1 | F:CCTGGCGTCGTGATTAGTG R: TCAGTCCTGTCCATAATTAGTCC |

125 |

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results were assessed by Prism v.7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and expressed as mean plus or minus standard error of the mean. Multiple groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Cell viability of human ADSCs

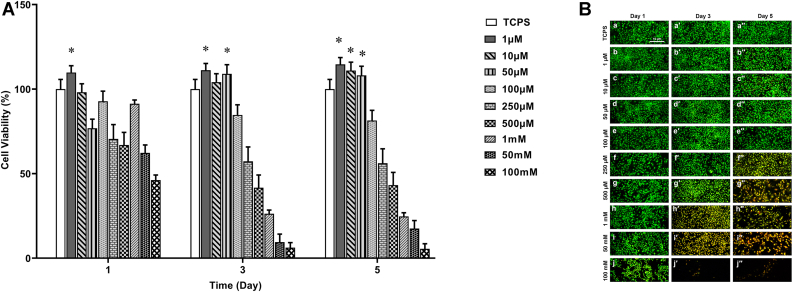

Fig. 1A shows the MTT assay for different concentrations of CCh after 1, 3, and 5 days of treatment. The study of cell growth in all samples for all days shows non-cytotoxicity for CCh at concentrations of 1, 10, and 50 μM on days 3 and 5 of treatment. On the 3rd day, concentrations of 1 and 50 μM showed a significant increase in the number of hADSCs after exposure. At 5 days after treatment, 1 and 10 μM concentrations not only showed non-cytotoxicity but also increased cell proliferation in treated hADSCs. However, CCh at the concentration of 1 μM presented better results than others (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

hADSCs viability assay in the presence of various concentrations of CCh by (A) MTT test (∗p < 0.05) and (B) AO/EB staining at 1, 3, and 5 days after treatment (Scale bar: 10 μm).

The data of the MTT assay were substantiated using AO/EB staining, a specific dye for cell death. Green and red colors in cells indicated live and dead cells, respectively. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 1B, the data suggested that a lower concentration of CCh not only had no cytotoxicity effect on hADSCs but also enhanced cell proliferation. However, the cell viability reduced with increasing CCh concentration and CCh at concentrations higher than 100 μM concentration revealed cell death on the 3rd and 5th days after treatment. According to the results from cell viability, 1 μM CCh was chosen as the optimal concentration for further analyses in the present study.

3.2. Calcium content assay

Calcium deposition was evaluated in differentiated hADSCs after 7 and 14 days of neural induction. As can be seen in Fig. 2, increased calcium deposition was observed in hADSCs of CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium groups compared to TCPS. However, the CCh-Ca groups showed the highest amount of calcium compared to TCPS and the other groups.

Fig. 2.

Calcium content of hADSCs on TCPS, CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium at the 7th and 14th days during neural differentiation (∗p ≤ 0.05).

3.3. Immunofluorescence staining for γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin

According to immunocytochemical assays at days 7 and 14, the presence of CCh in the neural induction media gave rise to the expression level of neural proteins, including γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin. As evidences seen in Fig. 3A–F, the CCh-Ca group revealed to have the highest protein expression compared to TCPS and the other groups, which indicated an increase in the number of differentiated hADSCs towards neuron-like cells. Furthermore, on the 14th day of differentiation, the expression of mentioned proteins increased in comparison with those on the 7th day of differentiation (Fig. 3D–F). The intensity of γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin was measured by ImageJ (Fig. 3G–I).

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence staining of differentiated hADSCs on TCPS, CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium groups on (A–C) 7th day and (D–E) 14th day after induction. Human ADSCs were studied for the expression of γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin (a, d, g, and j), DAPI staining (b, e, h, and k), as well as merging DAPI and markers (c, f, i, and l) (Scale bar: 10 μm). (G–I) The quantification graph of γ-enolase, MAP2, and β–III–tubulin using ImageJ (∗p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01).

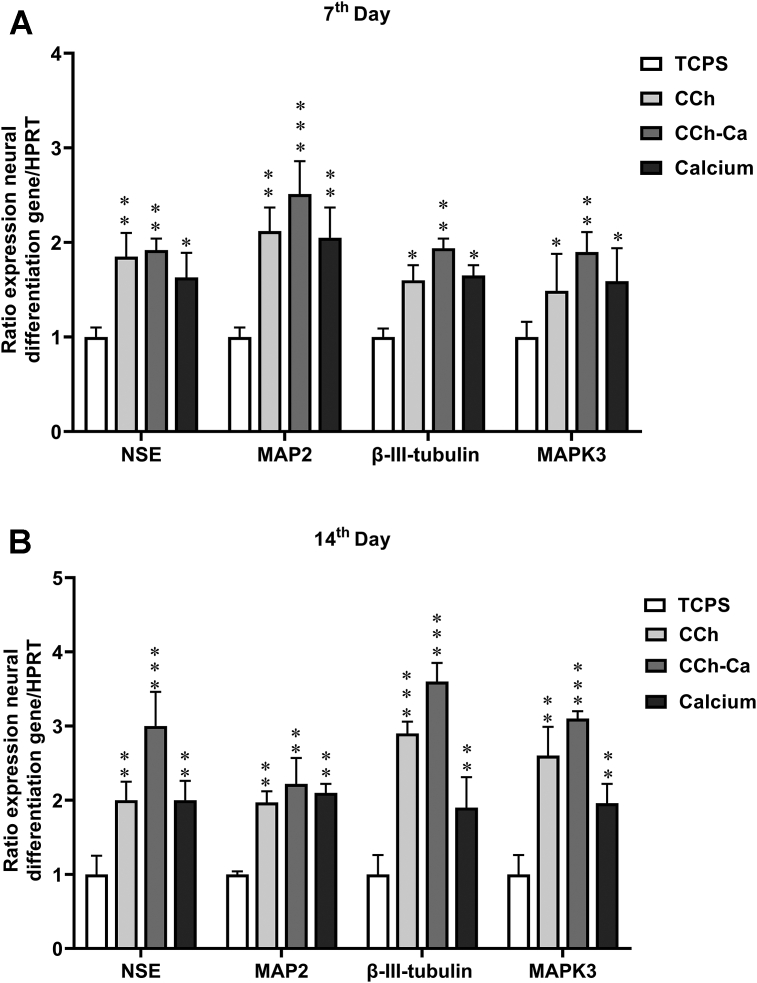

3.4. Gene expression analysis

Fig. 4 shows the relative expression of specific neural-related genes, including MAPK3, β–III–tubulin, NSE, and MAP2 expressed by differentiated hADSCs after 7 and 14 days of culture under neural induction on TCPS, CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium groups. Generally, genes illustrated increasing trends of expression, which was dependent on the physicochemical properties of CCh over time. According to Fig. 4A the expression of neural genes was significantly up-regulated in the CCh-Ca group at day 7 of differentiation. Additionally, the expression level of MAP2 was observed to be higher than the other neural genes, including MAPK3, β–III–tubulin, and NSE. On the 14th day of induction, the expression of MAPK3, β–III–tubulin, NSE, and MAP2 significantly increased in differentiated hADSCs in the presence of CCh-Ca comparable to TCPS, CCh, and calcium groups (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, in comparison with other genes, a higher expression of β–III–tubulin was detected on differentiated hADSCs exposed to CCh-Ca group in the late stage of induction at day 14. The relative expression of key neural genes showed that CCh had a positive effect on the neural differentiation of hADSCs at the end of induction period.

Fig. 4.

Relative expression of MAPK3, β–III–tubulin, MAP2, and NSE in differentiated hADSCs on TCPS, CCh, CCh-Ca, and calcium on (A) 7 and (B) 14 days after differentiation. HPRT1 was used as a control for RNA sample quality. Results are presented as mean ± SD. Significant levels are ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, and ∗∗∗P ≤ 0.001.

4. Discussion

Recently, stem cell technology has shown great application promise in various fields, including disease modeling, human developmental biology, and drug discovery screening, as well as regenerative and transplant medicine [18]. Adult stem cells, like mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the postnatal organism, are multipotent, have a the capacity to differentiate toward various types of cell lines, and exhibit an ability to assemble into proper structures for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and disorders [[19], [20], [21]]. The human MSCs can be isolated from different types of tissues, such as the umbilical cord, bone marrow, and adipose tissue [22,23]. Despite the remarkable properties of human MSCs, some reports have shown that hADSCs with a high yield obtained safer and easier compared to human MSCs harvested from cord blood and bone marrow [24]. ADSCs are also reported to have a longer life span, higher proliferative capacity, and shorter doubling periods comparable to bone marrow-derived MSCs [25]. The ability of hADSCs to increase the cell proliferation rate as well as differentiation into neuron-like cells has made them an exciting source for neural tissue engineering. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to provide an efficient protocol for neural induction of hADSCs in vitro.

Herein, we present evidence that the application of CCh in a medium containing forskolin, IBMX, and RA, as a primary neural medium, potentiates the responses of neural differentiation in differentiated hADSCs during the induction period. Numerous research works have revealed that forskolin and IBMX induce a significant change in cell morphology of various types of stem cells towards neuron-like structures by elevating intracellular cAMP [26,27]. The neural cAMP level not only has a positive effect on the regeneration of the central nervous system but also induces adult stem cells, such as MSCs, to differentiate into neural lineages cell and facilitate neuronal repair [28]. The cAMP signaling pathway activates protein kinase A (PKA), which involves the regulation of cell functions as well as differentiation [29]. However, cAMP alone is unable to differentiate the MSCs into neural lineage cells terminally. RA has been widely reported to induce various types of stem cells into neural lineages with high efficiency [30,31]. RA activates RA receptor (RAR) heterodimers, known as an essential factor in neuronal differentiation in vitro and modifies chromatin to modulate gene transcription related to the cell cycle and the switch between proliferation and differentiation [31]. In the current study, forskolin, IBMX as elevating-cAMP agents along with RA consist of our primary neural medium.

Moreover, in the current study, for the first time, CCh was investigated as a neural inducer in the differentiation of human ADSCs. The viability assay of cells in the presence of CCh showed that 1 μM and 10 μM concentrations not only had nontoxicity but also induced cell proliferation of hADSCs at the 5th day of treatment. Wang et al. used CCh at 10 μM concentration regulated the burst firing of dopaminergic neurons [32]. Furthermore, after incubation of hADSCs in neural differentiation medium and CCh for 7 and 14 days, cells expressed markers characteristic for neurons, such as NSE, MAP2, β–III–tubulin, and MAPK3 genes.

CCh has been reported to have the ability to elevate cAMP in cultured rat superior cervical ganglion neurons, while the rise in cAMP depended on calcium influx [33]. Additionally, Johansen et al. reported that the application of 10 μM CCh to the differentiation media enhanced the fraction of cells with calcium transients [34]. Furthermore, some studies have shown that a calcium rise upon stimulation happens by all neuronal activators, such as cAMP [26]. Calcium signaling plays a key role in many aspects of neurogenesis, from neural induction to the proliferation and differentiation of neural cells, through neurotransmitter specification, the appearance of ion channels that make neuronal excitability [15,35]. In differentiation, transcription factors are induced to promote the expression of receptors and ion channels associated with the neuronal phenotype [36]. In this process, increases in intracellular calcium lead to the expression of receptors, ion channels, and neurotransmitters forming neuronal phenotypes [15]. Herein, we found that 1 μM CCh treatment in the presence of calcium stimulated differentiation of hADSCs cultured in a medium with forskolin, IBMX, and RA after 7 and 14 days of neural induction. Moreover, the CCh-Ca group revealed a significant increase in neuronal markers analyzed through real-time PCR and immunocytochemistry as well as calcium deposition evaluated via calcium content test.

Studies have shown that CCh as an agonist of acetylcholine receptors, especially muscarinic receptors, had an effect on cholinergic receptors [37]. ACh is a neurotransmitter that binds to nAChRs and mAChRs and regulates signal transmission [38]. nAChRs are made of subunits assembled around a central ion channel, mediating the influx of Calcium [39]. Furthermore, mAChRs have been reported to have five subtypes from M1 to M5 and M1, M3, and M5 resulting in intracellular Calcium influx, whereas the M2 and M4 receptors negatively involve in adenylate cyclase [40]. Additionally, mAChR involves in many essential physiological functions, including cognitive processes [41]. M1 receptors are the richest receptor and M2 to M5 receptors are moderately found within the CNS [42]. CCh activates the mAChR, particularly the M1 receptor in the plasma membrane of neural stem cells [34,40]. Additionally, the M1 muscarinic receptor activates inositol trisphosphate (IP3) synthesis and receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum, which causes increased cytosolic Calcium because of IP3-sensitive channels [34,43]. As evidences obtained via calcium test, while calcium deposition was upregulated in all groups compared to TCPS and CCh-Ca group remarkably gave rise to calcium content after days 7 and 14 of the process. Uwada et al. used CCh as a muscarinic agonist to study the response of the stem cells to ACh receptors. They observed CCh activated M1 receptors coupled to signaling pathways in neuronal tissues, which impacted neuronal cell differentiation [40]. Furthermore, the current results showed that CCh increased the expression of genes, including NSE, MAP2, β–III–tubulin, and MAPK3 in the nucleus. Since the expression level of these genes represented neuronal differentiation, the presence of CCh in the medium influenced remarkably differentiation of hADSCs toward neuronal cell lineages. Importantly, differentiated hADSCs were shown to significantly express neural markers in the CCh-Ca group comparable to other groups during the differentiation process. MAPK pathway involves in neural differentiation; however, MAPK signaling is generally associated with growth and morphogen-dependent differentiation. Therefore, presumably, neural inducers signal via MAPK kinase to affect transcription factors involved in the neural signaling pathway [44]. Furthermore, NSE occurs late in neural differentiation, making it an essential sign of neural maturity [45], and β–III–tubulin is also a marker of proliferative and terminally differentiated neurons [46]. According to obtained data in this study, CCh as neurogenic factors present in the neural medium increased the hADSCs differentiation rate. Moreover, the expression of neural markers was the highest after 14 days of culture in the differentiation medium compared to 7 days. In addition, immunofluorescence staining illustrated that differentiated hADSCs on CCh-Ca had higher protein expression than TCPS. These data are in agreement with results obtained via real-time PCR acquired from the differentiated hADSCs.

5. Conclusion

Human ADSCs directed partially to neuron-like lineages might provide a new avenue for generating innovative therapeutics for a wide range of central nervous system illnesses, including neurologic ailments affecting the brain and spinal cord injuries. According to obtained data, CCh was demonstrated as a positive agent for neuronal differentiation and promoted neuron-like differentiated cells. The findings also revealed that calcium, along with CCh, significantly upregulated the expression level of markers associated with neuronal lineages as well as calcium content. Our findings suggest that CCh acts as an influential therapeutic factor in the field of regenerative medicine and research; however, further studies are necessary to evaluate its effectiveness in vivo and in vitro.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Cells were purchased from The Stem Cell Technology Research Centre, Tehran, Iran.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah Hospital and Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences for their technical support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

References

- 1.De Gioia R., Biella F., Citterio G., Rizzo F., Abati E., Nizzardo M., et al. Neural stem cell transplantation for neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21093103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng H., Huang Y., Yue H., Fan Y. Electrical stimulation promotes stem cell neural differentiation in tissue engineering. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6697574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frese L., Dijkman P.E., Hoerstrup S.P. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells in regenerative medicine. Transfus Med Hemotherapy. 2016;43:268–274. doi: 10.1159/000448180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D., Wang Y., Tian W., Pan J. Advances of tooth-derived stem cells in neural diseases treatments and nerve tissue regeneration. Cell Prolif. 2019;52 doi: 10.1111/cpr.12572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mammadov B., Karakas N., Isik S. Comparison of long-term retinoic acid-based neural induction methods of bone marrow human mesenchymal stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2011;47:484–491. doi: 10.1007/s11626-011-9425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagh V.D., Patil P.N., Surana S.J., Wagh K.V. Forskolin: upcoming antiglaucoma molecule. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58:199–202. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.101396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng W., Obrocka M., Fischer I., Prockop D.J. In vitro differentiation of human marrow stromal cells into early progenitors of neural cells by conditions that increase intracellular cyclic AMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:148–152. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scintu F., Reali C., Pillai R., Badiali M., Sanna M.A., Argiolu F., et al. Differentiation of human bone marrow stem cells into cells with a neural phenotype: diverse effects of two specific treatments. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y., Bai C., Wang K., Sun B., Guan W., Zheng D. All-trans retinoic acid promotes nerve cell differentiation of yolk sac-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;174:682–692. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colangelo C., Shichkova P., Keller D., Markram H., Ramaswamy S. Cellular, synaptic and network effects of acetylcholine in the neocortex. Front Neural Circuits. 2019;13:24. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2019.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoli M., Pucci S., Vilella A., Gotti C. Neuronal and extraneuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:338–349. doi: 10.2174/1570159x15666170912110450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bignami F., Bevilacqua P., Biagioni S., De Jaco A., Casamenti F., Felsani A., et al. Cellular acetylcholine content and neuronal differentiation. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1374–1381. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafsson J.K., Lindén S.K., Alwan A.H., Scholte B.J., Hansson G.C., Sjövall H. Carbachol-induced colonic mucus formation requires transport via NKCC1, K⁺ channels and CFTR. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467:1403–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1595-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y.Z., Liu X.H., Rong F., Hu S., Sheng Z.Y. Carbachol inhibits TNF-α-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction through alpha 7 nicotinic receptors. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1389–1394. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toth A.B., Shum A.K., Prakriya M. Regulation of neurogenesis by calcium signaling. Cell Calcium. 2016;59:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tirpáková M., Vašíček J., Svoradová A., Baláži A., Tomka M., Bauer M., et al. Phenotypical characterization and neurogenic differentiation of rabbit adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Genes. 2021;12 doi: 10.3390/genes12030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goudarzi F., Mohammadalipour A., Khodadadi I., Karimi S., Mostoli R., Bahabadi M., et al. The role of calcium in differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells to adipocytes. Mol Biotechnol. 2018;60:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s12033-018-0071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolios G., Moodley Y. Introduction to stem cells and regenerative medicine. Respiration. 2013;85:3–10. doi: 10.1159/000345615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alizadeh R., Bagher Z., Kamrava S.K., Falah M., Hamidabadi H.G., Boroujeni M.E., et al. Differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) to dopaminergic neurons: a comparison between Wharton's Jelly and olfactory mucosa as sources of MSCs. J Chem Neuroanat. 2019;96:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soraya Z., Ghollasi M., Halabian R., Eftekhari E., Tabasi A., Salimi A. Donepezil hydrochloride as a novel inducer for osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on PLLA scaffolds in vitro. Biotechnol J. 2021 doi: 10.1002/biot.202100112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gojo S., Gojo N., Takeda Y., Mori T., Abe H., Kyo S., et al. In vivo cardiovasculogenesis by direct injection of isolated adult mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Airuddin S.S., Halim A.S., Wan Sulaiman W.A., Kadir R., Nasir N.A.M. Adipose-derived stem cell: "treat or trick". Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9111624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohyama J., Abe H., Shimazaki T., Koizumi A., Nakashima K., Gojo S., et al. Brain from bone: efficient "meta-differentiation" of marrow stroma-derived mature osteoblasts to neurons with Noggin or a demethylating agent. Differentiation. 2001;68:235–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Locke M., Windsor J., Dunbar P.R. Human adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, characterization and applications in surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:235–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.04852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hass R., Otte A. Mesenchymal stem cells as all-round supporters in a normal and neoplastic microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-811x-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L., Seitz L.C., Abramczyk A.M., Liu L., Chan C. cAMP initiates early phase neuron-like morphology changes and late phase neural differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:863–876. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salimi A., Nadri S., Ghollasi M., Khajeh K., Soleimani M. Comparison of different protocols for neural differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:1713–1721. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai D., Qiu J., Cao Z., McAtee M., Bregman B.S., Filbin M.T. Neuronal cyclic AMP controls the developmental loss in ability of axons to regenerate. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4731–4739. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.21-13-04731.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang T.T., Tio M., Lee W., Beerheide W., Udolph G. Neural differentiation of mesenchymal-like stem cells from cord blood is mediated by PKA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanafiah A., Geng Z., Wang Q., Gao Z. Differentiation and characterization of neural progenitors and neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. J Vis Exp. 2020 doi: 10.3791/61446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janesick A., Wu S.C., Blumberg B. Retinoic acid signaling and neuronal differentiation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1559–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S.S., Wei C.L., Liu Z.Q., Ren W. The influence of L-glutamate and carbachol on burst firing of dopaminergic neurons in ventral tegmental area. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2011;63:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suidan H.S., Murrell R.D., Tolkovsky A.M. Carbachol and bradykinin elevate cyclic AMP and rapidly deplete ATP in cultured rat sympathetic neurons. Cell Regul. 1991;2:13–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johansen T., Krabbe C., Schmidt S.I., Serrano A.M., Meyer M. Comparative analysis of spontaneous and stimulus-evoked calcium transients in proliferating and differentiating human midbrain-derived stem cells. Stem Cell Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/9605432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tozuka Y., Fukuda S., Namba T., Seki T., Hisatsune T. GABAergic excitation promotes neuronal differentiation in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuron. 2005;47:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spitzer N.C. Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature. 2006;444:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature05300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saar D., Dadon M., Leibovich M., Sharabani H., Grossman Y., Heldman E. Opposing effects on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the piriform cortex of odor-trained rats. Learn Mem. 2007;14:224–228. doi: 10.1101/lm.452307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi T., Ohnishi H., Sugiura Y., Honda K., Suematsu M., Kawasaki T., et al. Non-neuronal acetylcholine as an endogenous regulator of proliferation and differentiation of Lgr5-positive stem cells in mice. FEBS J. 2014;281:4672–4690. doi: 10.1111/febs.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maouche K., Polette M., Jolly T., Medjber K., Cloëz-Tayarani I., Changeux J.-P., et al. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor regulates airway epithelium differentiation by controlling basal cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1868–1882. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uwada J., Anisuzzaman A.S.M., Nishimune A., Yoshiki H., Muramatsu I. Intracellular distribution of functional M1-muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 2011;118:958–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton S.E., Nathanson N.M. The M1 receptor is required for muscarinic activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase in murine cerebral cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15850–15853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volpicelli L.A., Levey A.I. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berridge M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson R., Casali C., Chan C. Forskolin and IBMX induce neural transdifferentiation of MSCs through downregulation of the NRSF. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2969. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39544-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eftekhari E., Ghollasi M., Halabian R., Soltanyzadeh M., Enderami S.E. Nisin and non-essential amino acids: new perspective in differentiation of neural progenitors from human-induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Hum Cell. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13577-021-00537-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chacon J., Rogers C.D. Early expression of Tubulin Beta-III in avian cranial neural crest cells. Gene Expr Patterns. 2019;34:119067. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2019.119067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]