Abstract

Background

Despite recommendations to deprescribe chronic benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZRA) among older adults, the prevalence of their use in Belgian nursing homes (NHs) remains above 50%. The use of a behavioral science approach, starting with the evaluation of barriers and enablers for BZRA deprescribing, has the potential to decrease BZRA prescribing.

Objectives

To identify barriers and enablers for BZRA deprescribing perceived by the different stakeholders involved in nursing home care in Belgium.

Methods

In a purposive sample of 6 NHs, we conducted face-to-face interviews with general practitioners (GPs), and focus groups with other healthcare providers (HCPs), including nurses, pharmacists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and with NH residents and relatives. All interviews with HCPs were analyzed through deductive thematic analysis, using the theoretical domains framework (TDF) as the coding framework. Residents' and relatives' interviews were analyzed using an inductive thematic approach.

Results

We interviewed 13 GPs, 35 other HCPs, 22 nursing home residents, and 5 relatives. Overall, 9 TDF domains were identified as most relevant among HCPs interviewed: Skills, Beliefs about capabilities, Goals, Memory attention and decision processes, Environmental context and resources, Social influences, Knowledge, Social/professional role and identity, and Beliefs about consequences. Five additional themes emerged from residents' and relatives' interviews: knowledge on medications used, communication with NH staff and GPs, perceived efficacy and necessity of BZRA, influence of the environment, and reluctance towards BZRA deprescribing. Some domains and themes differ between stakeholders (e.g., knowledge), while others match between groups (e.g., environmental aspects).

Conclusion

BZRA deprescribing is influenced by knowledge and skills gaps, automatic BZRA refilling, competing priorities, social challenges, environmental factors and poor nursing home residents involvement. Targeting these barriers will be a key step for implementation of BZRA deprescribing.

Keywords: Nursing home, Benzodiazepines, Deprescribing, Qualitative study, Barriers and enablers

Highlights

-

•

A large panel of stakeholders gave insights on BZRA deprescribing barriers & enablers.

-

•

We identified 9 TDF domains as most relevant for healthcare providers' behavior.

-

•

5 themes emerged from focus groups with nursing home residents.

-

•

Some barriers and enablers match while others differ between stakeholder groups.

-

•

Targeting these barriers and enablers is a key step to deprescribing.

1. Introduction

Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists (BZRA, namely benzodiazepines and Z-drugs) are mainly used in the treatment of anxiety and insomnia.1 In most cases, BZRAs have only modest benefits2 but can trigger severe side effects in older adults including falls and fractures, delirium, cognitive impairment, and dependence.1,3, 4, 5 Consequently, the benefit-risk profile is unfavorable and international recommendations advise against the use of BZRAs in older adults.6,7 Yet BZRAs are widely used among Belgian nursing home residents (NHRs), with a reported prevalence of 52.4%.8

Deprescribing is the action of discontinuing or reducing the use of a medication that is no longer needed or which may put the patient at risk, under the supervision of Health Care Providers (HCPs), to manage polypharmacy and improve outcomes.9 Many interventions promoting BZRA deprescribing have already been studied (mainly in the outpatient settings) and achieve deprescribing rates ranging from 27 to 80%.10 However, it remains unclear how to best implement BZRA deprescribing in nursing homes (NHs).

Implementation science recommendations highlight the need and benefit to build theory-driven approaches, starting with the identification of barriers and enablers, when designing implementation strategies.11, 12, 13 Two recent systematic reviews analyzed barriers and enablers of BZRA deprescribing in older adults, and reported more barriers than enablers, including a lack of knowledge, expected patients' resistance and interprofessional conflicts.14,15 However, the majority of studies were undertaken in outpatient settings and their results may not be applicable to other contexts (for example nursing homes). In addition, these studies did not involve the full range of HCPs involved in prescribing BZRAs. In Belgian NHs, only nurses' perceptions were evaluated in previously conducted studies,8,16, 17, 18 and no study was based on psychological theories.

The objective of the present study was to use a behavioral science approach to identify barriers and enablers to BZRA deprescribing in Belgian NHs perceived by i) physicians, ii) HCPs directly involved in nursing home care and iii) NHRs and their close relatives, and to map them into the theoretical domains framework v2 (TDF), a comprehensive commonly used framework to assess barriers and enablers. Ultimately, we aim to inform the development of a future intervention towards BZRA deprescribing.

2. Methods

We reported this study following the COREQ consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research.19

2.1. Study design

We conducted a qualitative study involving focus groups and face-to-face interviews with all relevant stakeholders in NH settings. The core behavior of interest was the initiation of BZRA deprescribing by general practitioners (GPs), when appropriate and in collaboration with other stakeholders. We explored GPs' perspectives in face-to-face semi-structured interviews. In addition, focus groups were used to explore the perspectives and potential influences of other stakeholders (other HCPs, and NHRs or relatives) in relation to the GP. We chose to separate GPs from other HCPs because of the difference in the behavior of interest (deprescribing vs supporting deprescribing), and to avoid social desirability bias, induced by hierarchical relationships.

2.2. Setting

This study was conducted in Belgian NHs. We conducted interviews in a purposive sample of NHs, to identify a wide range of views. Included NHs differed regarding the following variables: location (country regions, rural or urban area), type of ownership, and previous/ongoing experience of medication optimization approaches. We contacted the senior manager of each chosen NH for a participation agreement. NHs were identified based on previous collaborations, references from other collaborators, or personal contacts with one of the research team members. In case of refusal to participate, another NH with similar characteristics was asked for participation. We intended to perform interviews in a minimum number of 5 NHs and to continue recruitment until data saturation.

In Belgium, each NH must appoint a coordinating physician (CP), who is in charge of the NH medical policy, and acts as a contact person for NH staff. However, each NHR can freely choose his/her GP, meaning that the number of GPs visiting any NH is unrestricted. These GPs have complete freedom regarding diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Medication delivery is performed by a single pharmacy (either a community or a hospital pharmacy) for all NHRs. Currently, medication review activities are not funded, and the role of the pharmacist is often limited to medication delivery.

2.3. Participants

In each participating NH, we conducted face-to-face interviews with 2 GPs, and 2 focus groups, one with other HCPs involved in NH care, and one with NHRs and relatives. First, we interviewed the CP and at least one other GP for whom we received contact information either from the CP or from the NH senior manager. Second, in the focus group with other HCPs, we aimed to have 5 to 8 participants including at least one pharmacist, one chief nurse, and one nurse. NH staff were free to invite any other HCPs who might be involved in deprescribing. Finally, we included 4 to 8 NHRs and close relatives of NHRs from each NH. To be eligible, NHRs had to have lived in the NH for at least 6 months, regularly used BZRA or have had BZRA prescriptions for at least 4 weeks in the past 12 months, be aged 65 and older, and be able to participate in a focus group discussion (as judged by the staff). Close relatives of NHRs, identified by NH staff, were defined as someone who regularly visited the NHR and with knowledge/interest in medicines management for the resident. NH staff recruited NHRs and close relatives. They provided an information letter from the research team and written consent for participation was requested. Participants had no prior contact or collaboration with interviewers.

2.4. Data collection

All interviews were conducted using semi-structured, pilot-tested, interview guides (Appendix 1). Interview guides were developed in collaboration with researchers specialized in health behavior change and implementation science (AMP, JMG). We used behavioral theories as they help to better understand the behavior change process inherent in implementation of evidence-based practices.20,21 GPs' and HCPs' interview guides were developed based on the TDF. The TDF maps 128 constructs from 33 behavior change theories into 12 domains (14 for TDF version 2) that are possible determinants of a behavior.22 It has often be used to evaluate barriers and enablers for behavior changes.23, 24, 25 To ensure a detailed investigation of the determinants of behavior, interview guides contained at least one question per TDF domain. The NHRs' and relatives' interview guide was based on the revised Patients' attitudes towards deprescribing questionnaire (rPATD).26 The rPATD is a validated questionnaire that explores older adults' and their carers' attitudes and willingness towards deprescribing. We chose not to use the TDF for NHRs and relatives as it has primarily been developed to investigate HCP's perspectives, and we believed that the rPATD approach would be easier to use with NHRs and relatives, and would better fit our purpose. When appropriate, additional open-ended questions were asked to further clarify the respondents' point-of-view.

Face-to-face interviews with GPS were conducted at the GP practice, at the NH, or by phone. Focus groups with HCPs, NHRs and close relatives were conducted at the NH by a moderator and a second researcher, in charge of field notes. Only participants and research team members were present in the room. French-speaking interviews and focus groups were conducted by PE and Dutch ones by AD. All interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and anonymized before data analysis. Transcripts were not returned to participants. However, to ensure correct comprehension of participants' ideas, frequent summaries were made and discussions with the research team were held during data collection and analysis.

2.5. Data analysis

All transcripts were entered into QSR Nvivo 11 for data analysis. Two researchers (PE and AD), who both are pharmacists and researchers trained in qualitative data analysis and TDF coding, independently coded data. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, when needed, help from a third coder (AMP - an expert in TDF), was requested.

For HCPs and GPs interviews, we conducted a deductive thematic analysis, using the TDF version 2 as coding framework.13 One researcher (PE) then generated belief statements, which represented the specific themes from responses within each domain, and identified the most relevant TDF domains based on the frequency of the belief statements, the presence of conflicting beliefs, and evidence of strong beliefs that may affect the target behavior.13 A second researcher (AD) reviewed domain selection and the generated statements for relevance and appropriateness. Finally, the most relevant TDF domains were mapped into integrative themes, to ease presentation of the results. The identification of these themes was performed through discussions with all research team members.

For NHRs and relatives' interviews, we conducted an inductive thematic analysis.27 The coding tree was developed by two researchers (PE and AD) working together on the first two focus groups and was then used for the other transcripts. The coding tree evolved until the end of the analysis, to ensure the inclusion of all meaningful answers.

2.6. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethical committee at CHU UCL Namur on the 19th of May 2020. (NUB: B0392020000019). All participants gave informed written consent before interviews.

3. Results

Interviews were conducted in 6 NHs between September 2020 and January 2022. Initially, interviews were planned in 5 NHs. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, one NH withdrew from the study before focus groups. GPs' interviews had already been conducted and were kept in the analysis. This NH was replaced with a 6th NH with similar characteristics. Two HCPs (both pharmacists) could not participate in the focus group discussions and were interviewed separately. In total, we interviewed 13 GPs and conducted 5 focus groups with other HCPs (35 HCPs: 18 nurses (including 5 chief-nurses), 4 pharmacists, 4 occupational therapists, 3 care aids, 3 physical therapists, 3 speech therapists), and 5 focus groups with 22 NHRs and 5 relatives. Participants' and NHs' characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean duration of interviews was 50 min (range 36–67) for GPs, 67 (54–84) for other HCPs, and 59 (44–75) for NHRs and relatives. Data saturation was reached after interviews in these 6 NHs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of nursing homes and participants included.

| Nursing home characteristics (N = 6) | |

| Location: | |

| Brussels | 1 |

| Flanders | 1 |

| Wallonia | 4 |

| Ownership type: | |

| Private, non for profit | 3 |

| Public | 3 |

| General practitioners' characteristics (N= 13) | |

| Female gender n(%) | 4 (30%) |

| Years of experience as a GP: | |

| Median | 27 |

| Range | 1.5–47 |

| Years of experience in NHs: | |

| Median | 27 |

| Range | 1.5–47 |

| Number of nursing homewhere the GP has patients to visit: | |

| Median | 4 |

| Range | 2–8 |

| GPs being coordinating physician of any NH n(%) | 7 (53.8%) |

| Other HCPs' characteristics (N = 35) | |

| Female gender n(%) | 31 (88.6%) |

| Occupation n(%): | |

| Nurses | 18 (51.4%) |

| Pharmacists | 4 (11.4%) |

| Occupational therapist | 4 (11.4%) |

| Physical therapist | 3 (8.6%) |

| Speech therapist | 3 (8.6%) |

| Care aid | 3 (8.6%) |

| Number of HCPs per NH in the focus group: | |

| Median | 7 |

| Range | 6–8 |

| NHRs and relatives characteristics (N= 27) | |

| Number of participants per NH: | |

| Median | 5 |

| Range | 4–7 |

| Female gender, NHRs n(%) (N = 22) | 16 (72.7%) |

| Female gender, relatives n(%) (N = 5) | 2 (40%) |

Legend: GP: General Practitioner; HCP: Health Care Provider; NH: Nursing Home; NHR: Nursing Home Resident.

3.1. Barriers and enablers from the perspective of physicians and other HCPs

Overall, all HCPs, including GPs, perceived BZRA deprescribing to be very challenging (Beliefs about capabilities) and identified many barriers. Enablers were also identified, mainly by participants with recent experience with deprescribing or medication review interventions.

Six TDF domains were identified as most relevant for both GPs and other HCPs: Skills, Beliefs about capabilities, Goals, Memory attention and decision processes, Environmental context and resources, and Social influences. Additionally, Knowledge, Social/professional role and identity and Beliefs about consequences were most relevant for other HCPs only. A summary of key themes identified in each of these 9 domains is presented in Table 2. Quotes are presented per TDF domain and stakeholders' group in Table 3 (including quotes for TDF domains identified as not relevant).

Table 2.

Summary of the most relevant TDF domains and key themes for BZRA deprescribing in Belgian nursing homes, per stakeholders' group.

| Relevant TDF domains | Key Themes | GPs | Other HCPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| TDF domains relevant for both GPs and other HCPs | |||

| Skills | Lack of practical training on how to deprescribe BZRAs | B | B |

| Lack of training on non-pharmacological alternatives | B | ||

| Good communication skills (with other health care providers and with NHRs) | E | E | |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Low self-efficacy | B | B |

| Difficulties to convince other stakeholders (including the resident) | B | ||

| Goals | BZRA deprescribing should be a long-term goal | E | E |

| Competing goals (including NHR well-being, acute conditions, keeping a smooth NH environment). | B | B | |

| Memory, Attention and Decision process | BZRA refilling happens automatically | B | B |

| BZRA prescribing is seen as an easy solution | B | ||

| Triggers for BZRA deprescribing: Other stakeholders' suggestions, balance issues, over sedation, confusion… | E | E | |

| Environmental context and resources | Collective living, with strict time schedule, noise and disturbances | B | B |

| Lack of time and NH staff (nurses, care aids…) | B | B | |

| Difficulties to implement non-pharmacological alternative (limited access, low practicability for NHRs or interest from them) | B | B | |

| High number of visiting GPs | B | ||

| Multidisciplinary work | E | E | |

| Need for a pharmacological alternative | B | ||

| Use of non-pharmacological alternatives, including phytotherapy, daytime activities | E | E | |

| Patient characteristic/ context: Long-term BZRA use (years) | B | ||

| Use of a brochure to raise NHRs' awareness | E | ||

| Automated medication delivery system reduces the opportunity to review medications | B | ||

| Social influence | Perceived NHRs' reluctance to deprescribe BZRA/ NHRs' pressure to have BZRA | B | B |

| Other HCPs' pressure on GPs to prescribe BZRA | B | ||

| HCPs triggering GPs to deprescribe | E | ||

| Relatives' influence | B/E | B/E | |

| TDF domains most relevant for HCPs except GPs | |||

| Knowledge | Lack of familiarity BZRA, BZRA side-effects and BZRA deprescribing | B | |

| Non-pharmacological alternatives unknown or not well known | B | ||

| Social/professional role and identity | Difficulties for GPs to accept remarks and advices from colleagues | B | |

| Feeling of depending on GPs' decision | B | ||

| Perceived role of nurses or other HCPs (e.g. physical therapist) to report NHRs' behavior/status to the GP or nurses | E | ||

| Beliefs about consequences | Increased workload at the NH level | B | |

| Easier management of NHRs on the long-term | E | ||

| Potential negative outcomes for NHRS (Withdrawal symptoms, insomnia, anxiety, anger, …) | B | ||

| Potential positive outcomes for NHRs (reduction of falls, cognitive and mobility improvement, …) | E | ||

Legend: B = Barrier, BZRA = Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, E = Enabler, GP = General practitioner, HCP = Health care provider, TDF = Theoretical domains framework.

Table 3.

Barriers and enablers to BZRA deprescribing for NH HCPs according to relevant TDF domains.

| Relevant TDF domains | Belief statements | Barrier (B) or Enabler (E)? |

Quotes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPs | Other HCPs | GPs | Other HCPs | ||

| TDF domains relevant for both GPs and other HCPs | |||||

| Skills | Lack of practical training on how to deprescribe BZRAs | B | B |

“We are told that they [BZRAs] are bad, that we must avoid them, but I have never attended a workshop on BZRA deprescribing. That would be interesting.” 1106 “But I think that what we need above all is to be guided by plans or detailed protocols that explain properly how to do it.” 1104 |

“[Have you been trained in BZRA deprescribing?] Me? Certainly not, 40 years ago. Those were things we didn't talk about. - We were trained in… techniques but none that related to deprescribing benzos.” 1412 and 1451 (nurse and occupational therapist) |

| Lack of training on non-pharmacological alternatives | B | “Perhaps if we were better informed [about non-pharmacological alternatives] ourselves, we could say ‘Hey Doctor, I heard that…’.” 1411 (nurse) | |||

| Good communication skills (with other health care providers and with NHRs) | E | E | “You have to discuss things with the patient, you have to make arguments in favour.” 1106 | “Communication in general is the only thing that helps a lot.” 1312 (nurse) | |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Low self-efficacy | B | B | “I am not very confident. I am not very confident because I know that it's a lot of work.” 1202 | “It's true that I don't feel very comfortable either, I should argue“1141 (physical therapist) |

| Difficulties to convince other stakeholders (including the resident) | B | “The most difficult part is starting the deprescription and the withdrawal, because sometimes you are faced with a patient who just refuses, who is categorical and says, ‘No, I've been taking this [BZRA] for 20 years, you cannot take it away from me, … I categorically refuse to have it taken away or reduced’. And that's what sometimes causes the most difficulty.” 1104 | “You will never be able to persuade those people that they need to give it up [the BZRA]. As long as they are convinced that it is doing them some good, we will never be able to deprescribe it. It's not possible.” 1211 (nurse) | ||

| Goals | BZRA deprescribing should be a long-term goal | E | E | “It is clear that it is very important to reduce these medicines so that they can get the best possible results and really take proper care of themselves there.” 1104 | “What I think would be helpful is if you really saw sleep medication and anxiety medication as something temporary, just when a resident needs it.” 1531 (pharmacist) |

| Competing goals (including NHR well-being, acute conditions, keeping a smooth NH environment). | B | B |

“If there is something else, more serious, well, it [BZRA deprescribing] will come later.” 1104 “It is important, but not important enough to completely destabilise the existing overall [NHR] balance.” 1205 |

“Because we need them to sleep. When you have 138 [NHRs] who aren't sleeping … the button, as I call it [the call bell], goes constantly when they aren't sleeping.” 1412 (night shift nurse) “As long as it has a positive effect on the person, I am for continuing it.” 1211 (nurse) |

|

| Memory, Attention and Decision process | BZRA refilling is part of an automatism of GPs | B | B | “No, on a normal visit, I ask him [the resident] how he is, I measure his blood pressure, and I renew his BZRA prescription.” 1202 | “We don't even think about it [deprescribing].” 1211 (nurse) |

| BZRA are seen as an easy solution | B | “Unfortunately, I think that doctors sometimes prescribe a BZRA out of convenience, because it is easy to say “Having a panic attack? Take a Temesta®, take one every day to be sure not to have one.” 1104 | |||

| Triggers for BZRA deprescribing: Other stakeholders' suggestions, balance issues, over sedation, confusion… | E | E | “Systematically, if they tell me that they are confused, that they have experienced falls, well, the side effects of medication come to mind, starting with BZRAs. It's automatic.” 1105 | “For example, we have residents who take that and we see that they are always very quiet, so we try to stop or reduce it.” 1515 (nurse) | |

| Environmental context and resources | Collective living, with strict time schedule, noise and disturbances | B | B | “The problem is that we are in a place that is not their normal environment. There are more people passing by, nurses, noises. They might also be less comfortable sleeping there than at home.” 1105 | “In shared accommodation, of course, it is complicated. There is a lot of noise, even at night, there are patients walking around, people shouting, bells sounding frequently. … It is difficult for residents to get quality sleep.” 1121 (head nurse) |

| Lack of time and NH staff | B | B |

“We don't have the time, and you need to sit with them, and explain things and review their treatments.” 1202 “I think there is a severe shortage of staff and patients suffer because of that shortage.” 1105 |

“For us, at night, it is even worse. Three [care staff] for 138 [NHRs].” 1412 (night shift nurse) | |

| Difficulties to implement non-pharmacological alternative (limited access, low practicability for NHRs or interest from them) | B | B | “For minor anxiety, I don't push too hard for a psychologist, because I know that, unfortunately, it is really difficult to access that kind of care.” 1104 | “We don't have the time [for non-pharmacological approaches]. It's not possible, it's not feasible.” 1411–1421 (nurses) “It's also generational. I think that if I spoke to today's residents about Snoezelen, essential oils, lights… I think they would be more reassured by a drug than by our new techniques.” 1252 (occupational therapist) |

|

| High number of visiting GPs | B | “Creating a NH policy is very difficult, for benzodiazepines, for the use of antibiotics, for anything. It is difficult to reach a consensus or unanimity or even to get a large majority of doctors to follow it.” 1203 | |||

| Multidisciplinary work | E | E | “Team decisions. Having the collaboration and support of the care staff. Because they are truly on the front line and they are the ones who can tell us how the residents feel.” 1203 | “We always consult with colleagues. Yes, colleagues first. Because it's multidisciplinary, the care staff, the cleaners – yes, they will be there too – and we go on from there. To the team head, then meetings, and then we go to the doctor.” 1513 (nurse) | |

| Need for an alternative/substitute | B | “At that point, we try to find alternatives, because patients do not want to go from taking something to taking nothing.” 1105 | |||

| Use of non-pharmacological alternatives, including phytotherapy, daytime activities | E | E | “I think that any activity during the day will make them [NHRs] think about something else, so it is beneficial.” 1202 | “Going on trips, going out, they expend energy so they get a good sleep. If, however, you don't change anything in their lives and you take away the sleeping pills, then…” 1112 (nurse) | |

| Patient characteristic/ context: Long-term BZRA use (years) | B | “Sometimes they arrive with them, they have used the medication for years and, when they arrive here, we continue it.” 1211 (nurse) | |||

| Use of a brochure to raise NHRs' awareness | E | “We have a brochure, an information brochure and we go around the residents. So we explain the disadvantages and consequences of using psychotropic drugs. And yes, some people have taken it on board because we have good results here with stopping sleep medication.” 1513 (nurse) | |||

| Automated medication delivery system reduces the opportunity to review medications | B | “When we prepare the drugs, well, we look at the drugs that we need to prepare. The others are in the automated dispensing system. We don't look at them as closely as when we prepare them.” 1421 (head nurse) | |||

| Social influence | Perceived NHRs' reluctance to deprescribe BZRA/ NHRs' pressure to have BZRA | B | B | “We often hit a wall with patients: ‘No, not that one’. We can stop anything we want, we can stop their anti-arrythmia medicine, we can stop their anti-cholesterol medicine, but not their Zolpidem or their Alprazolam.” 1202 | “People who are lucid sometimes cling to their medication. What time is my Temesta®? What time is my Zolpidem®? What time will it come at?” 1211 (nurse) |

| Other HCPs' pressure on GPs to prescribe BZRA | B | “There is sometimes intense pressure from the care staff to calm these patients.” 1105 | |||

| HCPs triggering GPs to deprescribe | E | “When the care staff speak up and say, ‘everything is going very well, do they really need this medicine?’, it makes the doctor's job easier to be aware of that.” 1101 | |||

| Residents relatives' influence | B/E | B/E | “There are people who will say to you, ‘don't you think that Dad or Mum is taking a bit too many kinds of medication?’ 1205 | “Ask the doctor to come by, my mother is not sleeping, perhaps he can prescribe something to help her sleep.” 1211 (nurse reporting on a conversation with a relative) | |

| TDF domains relevant for HCPs other than GPs only | |||||

| Knowledge | Lack of familiarity with BZRA, BZRA side-effects and BZRA deprescribing | B | “There are lots of drugs [names] there that I know …, and I am shocked to discover that they are in fact benzos. So, that just goes to show that it's really not my field at all.” 1141 (physiotherapist) | ||

| Non-pharmacological alternatives unknown or not well known | B | “You see, there may be things we could do to help some people that we don't know about.” 1451 (occupational therapist) | |||

| Lack of familiarity with deprescribing guidelines and tools | B | “We perhaps lack information on how to do it. How to do it so that it works properly. We know that we need to deprescribe them [BZRAs], but how, that's where it gets complicated.” 1103 | |||

| Social/professional role and identity | Difficulties for GPs to accept remarks and advices from colleagues | B | B | “Doctors are very touchy. Doctors, I'm generalising of course, are quite sensitive and not very open to criticism regarding their practice. Myself included.” 1101 | “They [GPs] should start listening to us, to everything we have to say, and agree to review their diagnoses. But for every ten doctors, there may be one who will do that.” 1131 (pharmacist) |

| Feeling of depending on GPs' decision | B | “We are dependent on the doctor's prescription.” 1121 (head nurse) | |||

| Perceived role of nurses or other HCPs (e.g. physical therapist) to report NHRs' behavior/status to the GP or nurses | E | “We observe and report back to the doctor. We will say he is quieter now… but, on the other hand, there are issues because he is sleeping a lot.” 1411 (nurse) | |||

| Beliefs about consequences | Increased workload at the NH level | B | B | “I think that could be difficult for the nursing home to manage, er… If there were withdrawal symptoms, recurring anxiety, or recurring insomnia… I think all that would be complicated.” 1103 | “Caring for someone who hasn't had a good night's sleep, you can take a beating! Anxiety sets in, agitation sets in. It's harder to treat the person during the day too. - It's not easy.” 1211 and 1212 nurses |

| Easier management of NHRs on the long-term | E | E | “If a patient has fewer falls, less care is required for that patient. If the patient is less confused, it may be easier for the nurses to care for them. Yes, it's positive.” 1105 | “It is not in our interest to give people that kind of medicine: anything that calms them down, anything that inhibits them. […] Because anything like that will also complicate our care.” 1411 (nurse) | |

| Potential negative outcomes for NHRS (Withdrawal symptoms, insomnia, anxiety, anger, …) | B | B | “Well, we will have angry and grumpy people and there will still be insomniacs and anxious people too…” 1202 | “You are obliged to give it to the person so that they can rest. Otherwise, they are tired during the day and at risk of falls and so on.” 1212 (nurse) | |

| Potential positive outcomes for NHRs (reduction of falls, cognitive and mobility improvement, …) | E | E | “The recovery of certain cognitive functions and a reduction in falls in particular.” 1102 | “If we have someone who falls frequently, it would be a good idea to reduce them [BZRAs].” 1321 (head nurse) | |

| Other TDF domains (beyond most relevant domains) | |||||

| Optimism | Varying views | B/E | B/E |

“Long-term, it [BZRA deprescribing] certainly appears to be beneficial.” 1101 “I don't believe that BZRAs destroy patients.” 1205 |

“No, it [BZRA deprescribing] would be a disaster.” 1211 (nurse) “That [BZRA deprescribing] would be nice. It would be great.” 1131 (pharmacist) |

| Reinforcement | Bad perception of policies and incentives | B | “Doctors are a bit… Well, they don't like constraints, sometimes they can react badly.” 1106 | ||

| Influence of past experiences | B/E |

“When you get a little bit of positive feedback, you tell yourself that things can go well and it encourages you to try to repeat the experience.” 1101 “I had a lot of bad experiences, well failures, so maybe I'm a bit more reluctant to try. Because I tell myself that it's a losing battle.” 1103 |

|||

| Intention | Intention to review medication and to prescribe the less possible | E | “The intention is always there, but I try with the patients.” 1105 | ||

| Emotion | Satisfaction | E | “It's always gratifying to say that we did things well.” 1102 | ||

| Behavioral regulation | Visual reminder | E | “I think that even just one poster in the medical office would help a lot. Even just a good visual reminder.” 1104 | ||

Legend: B = Barrier, BZRA = Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, E = Enabler, GP = General practitioner, HCP = Health care provider, NH = nursing home TDF = Theoretical domains framework.

The main barriers and enablers participants encountered are described in the following 5 integrative themes:

3.1.1. Knowledge and Skills gaps

We found various levels of knowledge regarding BZRAs, their side effects, and deprescribing. In particular, HCPs (other than GPs, nurses and pharmacists) admitted to lack of knowledge of BZRAs and their use. Knowledge of non-pharmacological alternatives also differed between HCPs and a lack of training for their implementation was highlighted (Knowledge). GPs reported not having received practical training on how to deprescribe and were not always familiar with available tools and withdrawal schedules (Skills). It appeared that younger GPs had more training regarding deprescribing than older GPs. The most cited necessary skills were communication (between HCPs and with NHRs and relatives) and management of withdrawal symptoms.

3.1.2. Automatic BZRA refilling

Most GPs and HCPs indicated that BZRA prescription and refilling happens automatically and that they do not routinely think about deprescribing (Memory attention and decision processes). Refilling was perceived as a quick and easy way to address insomnia or anxiety. Nevertheless, respondents identified multiple triggers for considering BZRA deprescribing: other stakeholders' suggestions, occurrence of adverse effects (e.g. over-sedation, balance issue, confusion, lack of appetite, agitation), becoming GP of a new patient, implementation of deprescribing or medication review interventions at the NH level, and NH entry. Nurses specifically reported that having an automated medication delivery system, in which nurses do no longer have to prepare medications before administration, reduced the probability of having them review medications (Environmental context and resources).

3.1.3. Competing priorities

Although GPs agreed that BZRA deprescribing was clinically relevant and should be a long-term goal for all NHRs, it was often considered not to be a top priority (Goals). Higher priorities included treating acute conditions, maintaining a balance in the NHR's well-being, and maintaining a smooth NH environment. In particular, BZRA deprescribing was not a top priority when NHRs did not experience BZRA side effects.

3.1.4. Social challenges and opportunities enhanced by perceived consequences

GPs reported finding it difficult to deprescribe (Beliefs about capabilities) due to feeling pushed to prescribe or refill BZRA, both by other HCPs and NHRs themselves (Social influences). They perceived that NHRs were reluctant to reduce or stop BZRAs out of fear to not be able to sleep. NH staff also played an important role, as GPs reported sometimes prescribing BZRA to please HCPs. This reluctance from some HCPs to deprescribe BZRA might be explained by the beliefs they had that it would lead to increased staff workload and adverse consequences for NHRs, such as frustration, anxiety, and anger (Beliefs about consequences). Still, some HCPs also perceived positive consequences such as improving NHRs' balance and awareness. HCPs who were willing to support BZRA deprescribing perceived that their role was to report on NHRs' behavior and status to the GP, yet they did not always feel listened to by GPs (Social/professional role and identity). GPs indeed admitted feeling irritated when receiving colleagues' suggestions, but recognized that other HCPs could act as triggers for BZRA deprescribing.

3.1.5. Environmental factors

Many barriers and enablers for BZRA deprescribing are related to environmental factors. This was highlighted by all stakeholders' groups and substantially influenced beliefs about capabilities. First, communal living imposes some difficulties such as noise, strict bedtime schedules and potential disturbance by other NHRs, that could lead to increased anxiety and sleep issues (Environmental context and resources). Second, the lack of staff was highlighted, directly leading to lack of time for all HCPs, and a lack of human contact for NHRs. The implementation of non-pharmacological alternatives to BZRA was described as difficult (Beliefs about capabilities), because of this lack of staff and time, and because of poor training on how to implement them (Environmental context and Resources, Skills). In particular, lack of access to psychological support was highlighted by GPs. The implementation of multidisciplinary care and medication reviews was seen as an important enabler for all HCPs. Still, time constraints were an important barrier to the implementation of such meetings.

3.2. Barriers and enablers from the perspective of NHRs and relatives

Five themes emerged from focus groups with residents and relatives: knowledge on medications used, communication with NH staff and GP, perceived efficacy and necessity of BZRA, influence of the environment and reluctance towards BZRA deprescribing. Overall, NHRs and relatives had similar views on these themes. Themes are described hereafter, and quotes are available in Table 4.

Table 4.

Quotes per themes and sub-themes identified in focus groups with nursing home residents and relatives.

| Theme | Sub-theme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge on medications taken | Poor knowledge of their overall medication (barrier) | “But I don't know what I'm taking” 2115 |

| Ability to recognize the shape and colour of their BZRA (barrier) |

“In the evening, I take a little yellow one.” 2312 “I know that one. It is a white pill” 2115 |

|

| No knowledge on BZRA and their potential side-effects (barrier) | “Thanks to that meeting [the focus group]. Because, otherwise, I would not even have realised that she was taking that kind of medicine. I have heard the name Temesta® since I was young. It's a medicine like Dafalgan® to me.” 2221 (NHR's daughter) | |

| Lack of time and opportunity to ask their questions regarding BZRA, or other medications (barrier) | “When you ask for something, they [the nursing staff] are already gone.” 2113 | |

| Communication with NH staff and GPs | Communication issues inside the NH (barrier) | “What I mean is that communication here, at every level, sucks …” 2212 |

| Lack of relationship and time spent with GP (barrier) | “I haven't seen my doctor since… When he comes, it takes two minutes, so I don't need to pay €40 for that. He writes the prescriptions; I don't need to see him.” 2413 | |

| Feeling that they must should just follow GPs' instructions (barrier) |

“Me, I just do what he says and that's that.” 2313 “We are never given an explanation. Only that you have to follow what the doctor says. And [take] whatever [medications] they bring you.” 2115 |

|

| Perceived efficacy and necessity of BZRA | Perception that BZRA are effective or not effective (barrier and enabler) | “I was given this sleeping pill, which is going very well by the way. […] It's perfect.” 2313 “I take it but, despite that, we are woken up by each other, so it's not of much use in the end.” 2412 |

| Perception that BZRA are necessary, enhanced by sleeping issues when BZRA are forgotten (barrier) | “But I can't do without them.” 2511 “I don't know if they do anything, but I think it would be even worse not to take them.” 2115 “Yes, I need them. I don't think they would be given to me otherwise.” 2315 “If by chance I forget it, I toss and turn in my bed. … That means that, usually, it works.” 2411 |

|

| High importance of sleep for NHRs (barrier) | “There is no other solution yet because, if you have not slept, you are nothing. You're a rag, as the expression goes.” 2515 | |

| Sleep-hindering and anxiety-enhancing environment | Unfavorable environment: noises, uncomfortable accommodations (barrier) |

“We can't sleep in peace here in the nursing home. There are people passing by, shouting at night… People who are lost.” 2115 “Because we have no air, we can't open the windows. It is 25–26 degrees [Celsius] in the rooms. We don't have access to the thermostatic valves, the mattress is plastic.” 2413 |

| Lack of human contact and activities (barrier) | “[The day] seems long, eh? Oh yes, it seems long.” Conversation between 2311 and 2312 | |

| Environmental stress (barrier) | “Sometimes I get stressed when I see things that I don't like in the home [NH]. Which upset me. I get very stressed then, because I would like to do something, I would like to help other people …, so I need Lysanxia® from time to time, ten drops during the day.” 2413 | |

| Reluctance towards deprescribing deprescribing | Agreement to stop if GP said so (enabler) | “If the doctor says I don't need to take it anymore, I won't take it anymore. I think he knows what I do and do not need to take.” 2315 |

| Expected difficulties: lack of sleep, need for an alternative and for support during deprescribing (barrier) |

“No matter who advised it [BZRA deprescribing], I wouldn't stop taking it [BZRA]. If I stop taking it, I won't sleep, so it's not worth it.” 2113 “I think I would say, ‘We can try, of course, but by giving her another drug that can also help her sleep.’” 2221 (NHRs' daughter) “But then I have to be 100% sure that the patient's observation is in direct proportion to the reduction of medication” 2521 (NHR's son) |

Legend: BZRA: Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, GP: general practitioner, NHR: nursing home resident.

3.2.1. Poor knowledge on medications used

Despite having overall poor knowledge about their medication, including BZRA and their side-effects, most NHRs were able to recognize their sleep medication based on the tablets' colour and shape. NHRs were interested in knowing more about their medication, and seemed to hold themselves responsible to collect the information they desire. Nevertheless, residents indicated to lack the opportunity to ask questions.

3.2.2. Lack of communication with NH staff and GP

NHRs were generally unhappy with communication inside the NH and their relationship with their GP. Some NHRs believed that they should follow GPs prescriptions, without further discussion.

3.2.3. Perceived efficacy and necessity of BZRA

NHRs were using BZRA for various reasons, sometimes for many years. Perceived BZRA effectiveness differed between residents, but most NHRs thought they were effective. Almost all NHRs believed that BZRA were a necessity and suggested they would not be able to sleep without them. The perception of BZRA efficacy and necessity was enhanced by the fact that they were prescribed by their GP, whom they trust largely, and by experiencing sleeping issues when they did not use the BZRA.

3.2.4. Sleep-hindering and anxiety-enhancing environment

NHRs reported that the NH environment did not favour sleep (e.g., noise issues, uncomfortable sleeping accommodations). NHRs also reported a lack of human contact and told they were bored, which could lead to overthinking and anxiety. Only a few residents were interested in the activities organized in the NH. Moreover, not all of them were aware of relaxation opportunities available in the NH. Finally, NHRs reported being impacted by the ambient stress in NHs, and nurses' stress.

3.2.5. Reluctance towards BZRA deprescribing

NHRs were generally reluctant to have BZRA deprescribed, even if suggested by the GP. Still, some NHRs would be interested in trying, sometimes only with an alternative. The two main difficulties anticipated were the lack of sleep and the lack of supervision of the deprescribing process.

4. Discussion

This qualitative study of barriers and enablers for BZRA deprescribing in Belgian NHs reveals that 6 TDF domains are highly relevant for all HCPs (Skills, Beliefs about capabilities, Goals, Memory attention and decision process, environmental context and resources, Social influences). Additionally, 3 domains were relevant for HCPs other than physicians (Knowledge, Beliefs about consequences, and Social/professional role and identity). NHRs and relatives expressed strong barriers related to a lack of knowledge and environmental context. They also reported a lack of communication with GPs and NH staff, variation in perceived efficacy and necessity of BZRA, and reluctance towards deprescribing.

4.1. Comparison with existing literature

Two recent systematic reviews reported barriers and enablers for BZRA deprescribing among older adults, with most studies included coming from the ambulatory setting, and fewer studies from the NH setting.14,15 One of these systematic reviews, also used the TDF,15 and found common relevant TDF domains: Beliefs about capabilities, Beliefs about consequences, Environmental context and resources, Goals, Social influences, and Memory attention and decision process. Intention was also highlighted as relevant. In our study, we found various levels of intention, but it did not seem to be a major behavioral factor. Additionally, our qualitative study reported Knowledge, Skills and Social/professional role and identity as most relevant. These domains were identified but not classified as most relevant in the systematic review. The difference might be due to the inclusion of a wider diversity of stakeholders in the present study. Still, the lack of knowledge and skills we report seems to be present worldwide.28, 29, 30 The other systematic review also had findings similar to our qualitative study, highlighting the lack of knowledge, the perceived efficacy of BZRA and the importance of multidisciplinary concertation.14

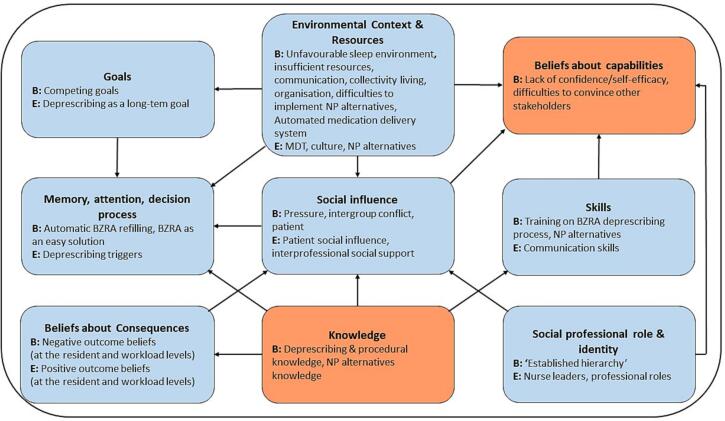

Heinrich et al. recently performed a ‘best-fit’ framework synthesis of the qualitative evidence of barriers and enablers for deprescribing in long-term care.28 We evaluated how their framework of 17 barriers and 16 enablers (that mapped to 11 of the 14 TDF domains), fits with our results in the specific context of BZRA deprescribing in Belgian NHs. Their framework remains overall applicable but we identified additional barriers (e.g. the automatic refilling, the competing goals and the difficulties to implement non-pharmacological approaches) that were absent from their framework. In Fig. 1, we present a conceptual model of the barriers and enablers reported by HCPs, based on the results from the present study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of healthcare providers perceived deprescribing barriers and enablers in the specific context of BZRA deprescribing in Belgian Nursing homes.

Legend: B: Barrier, E: Enabler, BZRA: benzodiazepine receptor agonists, LTCF: long-term care facilities, MDT: multidisciplinary team, NP: non-pharmacological.

Black arrows indicate potential influences between domains, based on the data collected and analyzed.

4.2. Moving from barriers and enablers to potential intervention components

Unsurprisingly, our data suggest that a complex intervention made of several components targeting important barriers is essential. Previous interventions such as the COME-ON and the RedUse interventions included components such as HCP training, multidisciplinary meetings and audit and feedback (for RedUse intervention). The authors reported a reduction on benzodiazepines use at both 6 and 12 months31,32 and increase rates of BZRA deprescribing.8 Our findings suggest a number of potential strategies to promote BZRA deprescribing.

First, providing education and training to HCPs will be essential to address some of the barriers. Indeed, we reported a lack of skills for all HCPs, and HCPs other than GPs also had knowledge gaps regarding BZRAs and their use. Training could also enhance HCPs' perceived beliefs about capabilities regarding deprescribing. HCPs' training should cover shared decision-making, BZRA side-effects, health consequences of deprescribing, the tapering process, and non-pharmacological alternatives. Specific tools such as a tapering schedule and deprescribing algorithm should also be presented to HCPs. While some parts of training should be tailored to the HCPs' profile (e.g tapering schedule for GPs, non-pharmacological alternatives for nurses), interdisciplinary training should also be explored as it may then facilitate multidisciplinary work.

Second, HCP level interventions should go beyond education and training so as to better impact the decision process. For example, action planning or goals setting could help to tackle the current situation of automatic refilling of BZRA and the issue of competing priorities. Such strategies could be organized at the NH level. As an example, defining a common vision and strategic approach towards BZRA deprescribing at the NH level might enhance HCPs' perceived capability and targets the identified barrier of competing goals. This should be done with all stakeholders' involvement, including NH management, and should guarantee a supportive organizational culture, which is of major impact.33,34 Providing audit and feedback on BZRA use and deprescribing might also ensure that BZRA deprescribing remains an institutional priority.

Third, clarifying and strengthening the role of each stakeholder and enhancing interdisciplinarity collaboration needs to be part of the defined approach and process. It is also in line with recommendations for interventions towards prescribing optimization in NHs,35,36 and with reported enablers of medication reviews.37 If time constraints do not allow multidisciplinary team meetings, other approaches can be considered, such as the use of a dedicated communication tool, which can improve communication between HCPs.38

Fourth, change in the physical NH environment, such as reduction of noises, soft lightnings, or comfortable sleeping accommodations, may also be necessary to target environmental barriers. However, evidence is still lacking on the feasibility and medication-related impact of such physical environment changes.

Fifth, engaging NHRs and their families in deprescribing also appears essential to address the many barriers identified on their side such as poor knowledge of BZRA and their side-effects, and the report of not feeling heard and poor communication. A previous Belgian study reported that NHRs' involvement was currently unstructured, and occurred mainly at NHRs' initiative. HCPs believed that NHRs' involvement would prevent potential disagreements and increase NHRs' autonomy, but could also decrease the quality and safety of medication use.34 A recent qualitative study analyzed barriers and enablers of older adults initiating deprescribing conversation.39 They mainly reported barriers and enablers similar to our results such as a low self-efficacy, lack of knowledge and communication, and poor resources access. Strategies to promote conversation initiatives included the use of information tools, telemedicine to increase discussion opportunities, and multidisciplinary team environments.39 Previous trials reported that patient brochures aimed at increasing knowledge and concerns about BZRA's long-term use and at raising patients' self-efficacy led to significant increases in deprescribing of BZRAs.40,41 No published data on the effectiveness of such brochures exist in the NH setting, but it is worth exploring. In person interactions are also required, and highlighting the risk of adverse effects is an important aspect, although conversations should ideally be individualised to what matters most to patients.42

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, we used the TDF, which is a validated psychological framework to evaluate barriers and enablers for health professional and health-related behavior. This enhances the validity of our findings and enables linking identified TDF domains to behavior change techniques (BCTs)43 in the purpose of developing an intervention. Second, we interviewed a large sample of respondents, representing all stakeholders' groups, and with various points of view. This is particularly important, as a previous systematic review reported the views of some healthcare providers', including pharmacists, had not been elicited.15 Importantly, data saturation was reached for all interview groups. Finally, the trustworthiness of our results was also strengthened by investigator and data source triangulation. We did not return transcripts to respondents to check on accuracy, but we ensured a correct interpretation of their perspectives through frequent reformulation during interviews.

This study also has limitations. Interviews were performed over a long period (approximately one year and a half) and during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have triggered anxiety and sleep issues in nursing homes. We raised this question in each focus group, and respondents reported no perceived change in BZRA use related to the pandemic, which is consistent with a published analysis from Spanish NHs,44 suggesting that the pandemic may have had limited to no impact on our findings. Additionally, we did not explore the interactions between GPs and other HCPs, as they were not mixed in focus groups. However, we felt that keeping them separate was needed to have all participants talking freely.

5. Conclusion

In this large qualitative study with participation of many stakeholders, we identified that BZRA deprescribing is influenced by knowledge and skills gaps, automatic BZRA refilling, competing priorities, social challenges, environmental factors and poor NHRs involvement.

The next step in the present theory-driven approach is now to select BCTs related to the TDF domains, using the theory and techniques tools.45 To ensure the acceptability and practicability of the intervention, various stakeholders will be involved. Finally, we will evaluate the designed intervention in a pilot cluster-randomized controlled trial.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Evrard Perrine: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. Amber Damiaens: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Andrea M. Patey: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jeremy M. Grimshaw: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Anne Spinewine: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2023.100258.

Contributor Information

Perrine Evrard, Email: perrine.evrard@uclouvain.be.

Amber Damiaens, Email: amber.damiaens@kuleuven.be.

Andrea M. Patey, Email: apatey@ohri.ca.

Jeremy M. Grimshaw, Email: jgrimshaw@ohri.ca.

Anne Spinewine, Email: anne.spinewine@uclouvain.bel.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Glass J., Lanctot K.L., Herrmann N., Sproule B.A., Busto U.E. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2005;331:1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lader M.H. Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(suppl 6):S399–S405. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(99)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly K., Bracchi R., Hewitt J., Routledge P.A., Carter B. Benzodiazepines, Z-drugs and the risk of hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam M.M., Iqbal U., Walther B., et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia in the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;47:181–191. doi: 10.1159/000454881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucchetta R.C., da Mata B.P.M., Mastroianni P.C. Association between development of dementia and use of benzodiazepines: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:1010–1020. doi: 10.1002/phar.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Mahony D., O’Sullivan D., Byrne S., O’Connor M.N., Ryan C., Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;(67):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evrard P., Henrard S., Foulon V., Spinewine A. Benzodiazepine use and Deprescribing in Belgian nursing homes: results from the COME-ON study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2768–2777. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeve E., Thompson W., Farrell B. Deprescribing: a narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;38:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeve E., Ong M., Wu A., Jansen J., Petrovic M., Gnjidic D. A systematic review of interventions to deprescribe benzodiazepines and other hypnotics among older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:927–935. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimshaw J.M., Patey A.M., Kirkham K.R., et al. De-implementing wisely: developing the evidence base to reduce low-value care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:409–417. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French S.D., Green S.E., O’Connor D.A., et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkins L., Francis J., Islam R., et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12:77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen A.F., Poulsen S.S., Oldenburg L.I.K., Vermehren C. The barriers and facilitators of different stakeholders when Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists in older patients-a systematic review. Metabolites. 2021:11. doi: 10.3390/metabo11040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evrard P., Pétein C., Beuscart J.-B., Spinewine A. Barriers and enablers for deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists in older adults: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2022;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthierens S., Grypdonck M., De Pauw L., Christiaens T. Perceptions of nurses in nursing homes on the usage of benzodiazepines. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:3098–3106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourgeois J., Elseviers M., Van Bortel L., Petrovic M., Vander Stichele R. Feasibility of discontinuing chronic benzodiazepine use in nursing home residents: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:1251–1260. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourgeois J., Elseviers M.M., Azermai M., Van Bortel L., Petrovic M., Vander Stichele R.R. Barriers to discontinuation of chronic benzodiazepine use in nursing home residents: perceptions of general practitioners and nurses. Eur Geriatr Med. 2014;5:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michie S., Johnston M., Abraham C., Lawton R., Parker D., Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidoff F., Dixon-Woods M., Leviton L., Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:228–238. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cane J., O’Connor D., Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bussieres A.E., Patey A.M., Francis J.J., et al. Identifying factors likely to influence compliance with diagnostic imaging guideline recommendations for spine disorders among chiropractors in North America: a focus group study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada J., Potestio M.L., Cave A.J., et al. Using the theoretical domains framework to identify barriers and enablers to pediatric asthma management in primary care settings. J Asthma. 2018;55:1223–1236. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1408820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh K.A., Sinnott C., Fleming A., et al. Exploring antipsychotic prescribing behaviors for nursing home residents with dementia: a qualitative study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:948–958.e912. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeve E., Low L.F., Shakib S., Hilmer S.N. Development and validation of the revised Patients’ attitudes towards Deprescribing (rPATD) questionnaire: versions for older adults and caregivers. Drugs Aging. 2016;33:913–928. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinrich C.H., Hurley E., McCarthy S., McHugh S., Donovan M.D. Barriers and enablers to deprescribing in long-term care facilities: a ‘best-fit’ framework synthesis of the qualitative evidence. Age Ageing. 2022;51 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun W., Tahsin F., Barakat-Haddad C., Turner J.P., Haughian C.R., Abbass-Dick J. Exploration of home care nurse’s experiences in deprescribing of medications: a qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefebvre-Durel C., Bailly I., Hunault J., et al. Benzodiazepine and Z drug cessation in elderly patients: a qualitative study on the perception of healthcare providers and the place of advanced practice nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;30(3):653–666. doi: 10.1111/inm.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westbury J., Jackson S., Gee P., Peterson G. An effective approach to decrease antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes: the RedUSe project. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:26–36. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westbury J., Tichelaar L., Peterson G., Gee P., Jackson S. A 12-month follow-up study of “RedUSe”: a trial aimed at reducing antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use in nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:1260–1269. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chenoweth L., Jessop T., Harrison F., Cations M., Cook J., Brodaty H. Critical contextual elements in facilitating and achieving success with a person-Centred care intervention to support antipsychotic Deprescribing for older people in long-term care. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:7148515. doi: 10.1155/2018/7148515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damiaens A., Van Hecke A., De Lepeleire J., Foulon V. Resident and informal caregiver involvement in medication-related decision-making and the medicines’ pathway in nursing homes: experiences and perceived opportunities of healthcare professionals. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22:81. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02773-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinewine A., Evrard P., Hughes C. Interventions to optimize medication use in nursing homes: a narrative review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:551–567. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00477-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawan M., Reeve E., Turner J., et al. A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health-care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:233–245. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1730812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wauters M., Elseviers M., Peeters L., De Meester D., Christiaens T., Petrovic M. Reducing psychotropic drug use in nursing homes in Belgium: an implementation study for the roll-out of a practice improvement initiative. Drugs Aging. 2019;36:769–780. doi: 10.1007/s40266-019-00686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahl L.J., Wright R., Xiao A., Keeven A., Carr D.B. Quality improvement in long term care: the psychotropic assessment tool (PAT) J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ailabouni N.J., Rebecca Weir K., Reeve E., Turner J.T., Wilson Norton J., Gray S.L. Barriers and enablers of older adults initiating a deprescribing conversation. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;105(3):615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tannenbaum C., Martin P., Tamblyn R., Benedetti A., Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:890–898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin P., Tamblyn R., Benedetti A., Ahmed S., Tannenbaum C. Effect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on inappropriate medication prescriptions in older adults: the D-PRESCRIBE randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;320:1889–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green A.R., Aschmann H., Boyd C.M., Schoenborn N. Assessment of patient-preferred language to achieve goal-aligned Deprescribing in older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michie S., Richardson M., Johnston M., et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferro Uriguen A., Laso Lucas E., Sannino Menicucci C., et al. Psychotropic drug prescription in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drugs Aging. 2022;39:467–475. doi: 10.1007/s40266-022-00948-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Theory and Techniques Tool 2021. https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org available from. Vol 08.12.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material