Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine some of the reasons why people are skeptical about the COVID-19 vaccination despite assurances from the authorities. In terms of methodological consideration, the study is situated within the qualitative research paradigm. The study adopted interviews and documentary analysis as the main source of data. The themes were generated from the data using the Voyant software, and the empirical discussion based on thematic analysis approach. The study reveals that trust in the COVID-19 vaccines, institutions, and cultural and religious beliefs determines people’s vaccination decisions in a significant manner. The study further highlighted that the quick production and administration of the various COVID-19 vaccines and history of previous epidemics/pandemic’s vaccination programs (such as the side effects of the vaccines) could have made people hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccination. Furthermore, trust in governments, pharmaceutical companies, and healthcare institutions informs people whether to participate in the COVID-19 pandemic vaccination project. Last but not the least, religious and cultural beliefs have sown seeds of skepticism in people and, ultimately, their COVID-19 vaccination decisions.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Vaccination, Skepticism, Herd immunity

Introduction

The outbreaks of pandemics/epidemics have had grave and serious consequences on countries and the global economy throughout history. The “Spanish Flu” of 1918–1920, HIV pandemic, smallpox outbreak in former Yugoslavia in 1972, SARS, Swine Flu/H1N1/09 pandemic, Ebola outbreak 2014–2016, Zika virus 2014–2016, and now COVID-19 pandemic are worth mentioning (Huremović, 2019).

In fact, these pandemics/epidemics did not only alter human civilization, but threatened the economic, political, health, and other architecture of the world economies. Often, their impacts spanned over generations and even centuries. Indeed, these pandemics/epidemics, apart from sending shock waves to the scientific communities and the public, redefined some of the basic ideologies of modern medicine on positive notes. For instance, the evolution and development of epidemiology, prevention, immunization, and antimicrobial treatments to save life and properties are concrete examples (Huremović, 2019).

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be overemphasized. It overburdened the existing health facilities which led to the creation of emergency hospitals and a lack of adequate medical personnel, coordination, and equipment—including vaccines. The extreme discourses about the efficacy of the vaccines authorized by the authorities therefore need attention (Lindholt et al., 2020). Besides, economic, education, tourism, agriculture, transport, and logistic sectors have also not been left out of the direct or indirect impacts of the pandemic (Song & Yixiao, 2020).

This study focuses on the COVID-19 vaccination skepticism. In fact, the scientific community has advocated for 60–70% vaccination for herd immunity to be achieved (Aschwanden, 2021). However, the political leadership leading the official discourses are divided (Jiang et al., 2020). Again, some of the vaccine-manufacturing companies are working on individual vaccines with little or no collaboration. Also, some media outlets fed the world with different information about the pandemic and vaccination (Loomba et al., 2021). In view of these, people develop mixed feelings for the vaccination campaign. We are, therefore, seeking to explore why some people are hesitant and/or skeptical to the COVID-19 vaccination.

Indeed, different authors have discussed vaccine hesitancy and/or skepticism (DW, 2021; Jaspal & Nerlich, 2022; Scheitle & Corcoran, 2021; Stecklow & Maskaskill, 2021; Tavernise, 2021). First and foremost, Jaspal and Nerlich (2022) examine people who questioned the existence of the virus. DW (2021) reports how political distrust leads to vaccine skepticism. Besides, Stecklow and Maskaskill (2021) analyze how the COVID-19 vaccine could cause infertility among women. Moreover, Scheitle and Corcoran (2021) compared the COVID-19 vaccine skepticism with other forms of vaccine skepticism. Finally, Tavernise (2021) evaluates how religious and secular reasons lead to vaccine skepticism.

This study is relevant because it will explore and contribute towards the understanding of reasons why some people are reluctant to taking the approved COVID-19 vaccines. We do this by soliciting primary data from three (3) different countries/context—Denmark, Ghana, and USA—and eight (8) different nationalities and gender to examine why some people have refused the COVID-19 immunization. To this end, we seek to explore this question: Why are some people sceptical about the COVID-19 vaccination despite assurances by the authorities?

We have structured the paper as follows: The introductory section throws light on the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination hesitancy. This is followed by a literature review and theoretical underpinnings of relevance to the problem formulation. The research methodology section was next. Finally, the last section was findings, discussion, conclusion, policy recommendations and implications, limitation as well as direction for future research.

Literature Review

The study seeks to explore why some people are COVID-19 vaccine skeptics. Vaccination is considered as one of the main panaceas to re-establish pre-coronavirus setting (International Rescue Committee, 2021). The World Health Organization in collaboration with the scientific community and governments has made strenuous efforts to develop vaccines. Consequently, vaccines such as Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Moderna were developed (World Health Organization, 2020).

Vaccine skepticism is beliefs about the dangers of vaccines. It also implies misjudgments of risk probabilities of vaccinations (LaCour & Davis, 2020). On the other hand, vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in tolerating or rejecting vaccination notwithstanding readiness and availability of vaccination (MacDonald, 2015). Therefore, people tend to accept vaccines when there are no (or less) risks, doubts, and misinformation surrounding the vaccine. Contrarily, vaccines are refused when negative beliefs such as high-risk probabilities, miseducation, and misjudgments on vaccines abound. In essence, skepticism predicts vaccine hesitancy.

Apparently, political and cultural beliefs, lack of access to vaccines, a refusal to see the pandemic as a real threat, lack of trust in the vaccines, and belief in some of the conspiracy theories are among the reasons some people are vaccine skeptics (Petersen et al., 2021). Using a sample size of 9889 participants, Lindholt et al. (2020) examined the levels and predictors of willingness to use the approved COVID-19 vaccines from eight Western countries. They discovered a huge variation of 79% in Denmark to 38% in Hungary in the vaccination willingness.

Furthermore, the International Labor Organization (ILO) projected that global hour worked in 2021 to be 4.3% less, compared to the period before the pandemic. However, this was a studied modification of the ILO’s June prediction of 3.5%. In the third quarter of 2021, high-income countries recorded a total work hour of 3.6%, low-income countries recorded 5.7% while lower-middle-income countries had 7.3% lower than the fourth quarter of 2019 (ILO, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic-related disruptions have necessitated the labor market recovery process to drastically lag the output recovery in majority of countries in the world (IMF, 2021).

However, with the global vaccination rollout, study shows that for every 14 persons fully vaccinated against the COVID-19 in the second quarter of 2021, one full-time equivalent job has been added to the global labor market recorded 4.8% (ILO, 2021).

Despite the success attained thus far in the labor hours recovery, the uneven roll-out of vaccinations suggests larger positive effects in high-income countries, low impacts in lower-middle-income countries, and almost zero effects in low-income countries. It is approximated that if the global south countries had access to vaccines without discrimination, working-hour recovery might correlate with richer economies soon (ILO, 2021).

Theoretical Underpinnings

We examined the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccination skepticism through the lenses of trust theory and post structuralism. The official discourses and regime of truths about the COVID-19 vaccination, and how they were conveyed to the societies by elites, invite post structuralist perspective. Again, the public acceptance of the vaccines largely depends on trust on governments, institutions, and the vaccines.

Trust could be understood as the “relationship that exists between individuals, as well as between individuals and a system, in which one party accepts a vulnerable position, assuming the best interests and competence of the other, in exchange for a reduction in decision complexity” (Larson et al., 2018: 1). Indeed, the activities of political leadership, the assessments of government institutions, and performance are the commonly identified potential antecedents to trust (Keele, 2007). Often, the populace monitors the performance of leadership. They modify their trust as and when the need arises (Citrin, 1974). In fact, good governance increases trust. It also indicates evidence of ability. Contrarily, poor government performance will reduce trust, showing evidence of leadership incompetence (Keele, 2007).

Furthermore, health inquiries make efforts to establish the safety, veracity, effectiveness, and importance of vaccination. Vaccine skepticisms—and sometimes vaccine rejection—are great drawbacks during global immunization campaigns (MacDonald, 2015). Vaccine hesitancy is affected by complacency, convenience, and confidence (MacDonald, 2015). Therefore, bolstering social trust and confidence correlates positively to superior trust generally (Twyman et al., 2008). Indeed, social trust and confidence connect with increased vaccine tolerance, and acceptance (Larson et al., 2018).

In essence, vaccine tolerance encompasses trust in the vaccine, belief in the healthcare practitioners, health system, and trust in government (Larson et al., 2015). Furthermore, trust in the source of information and the information itself (Chuang et al., 2015) and trust in those—government and media health experts—who disseminate the information are very relevant in terms of vaccine acceptance and/or tolerance level (Trevena et al., 2013).

Post structuralism holds the view that truth and knowledge are subjective and that entities are produced rather than discovered (Morrow, 2018; Peters & Burbules, 2004). Indeed, the power of framing is crucial in determining and shaping what comes to be accepted as the true knowledge or otherwise. As such, true knowledge is produced and re-produced by the prominent actors or “elites” who then impose it upon the society (Williams, 2014).

Accordingly, language is crucial in the creation and perpetuation of a dominant discourse. By acts of language and concepts, events are arranged in hierarchical pairs, termed binary oppositions (good versus evil or developed versus undeveloped). The purpose is to create meaning within the discursive construct. A classic example could be how President George W. Bush described Iran, Iraq, and North Korea after the events of 11 September 2001 as an “axis of evil”—making the three countries—“them”—positioned as international pariahs in contrast to the innocent—“us”—of the USA and its allies (Morrow, 2018; Peters & Burbules, 2004). As argued by poststructuralist including Michel Foucault, the regime of truth is made manifestly possible through the elites’ discourse and the power of language. This goes to enhance the ruling discourse that operates unquestioned within society, as the truth or fact (Williams, 2014).

However, the weakness of post structuralism is that the official discourse though powerful has never been comprehensively followed by the entire society and never all the time proven to be the truth. Yet, much room has not been provided for alternative discourse that could equally affect the course of events to emerge (Leonardo, 2003; Morrow, 2018).

Research Design and Methods

The paper examines the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccination skepticism. We adopted a qualitative exploratory research design. This research design is usually undertaken to examine the nature of a problem to acquire a better understanding of “what is happening; to seek new insights; to ask questions and to assess phenomena in a new light” (Robson, 2002: 59).

It helps to provide answers to questions framed in the form of what, how, and why (Saunders et al., 2009). It is logical to reiterate that the overarching research question in our introductory section seeks to find out “why” some people are skeptical about the COVID-19 vaccination.

Additionally, we used both qualitative and quantitative research approaches. Qualitative research is an investigative study that is focused on unearthing the reasons and opinions of individuals on a subject matter of enquiry (Bryan, 2016). Quantitative research makes references to numerical and statistical data (Creswell, 2009).

Access to Study Participants, Sample Size, and Techniques

To gain access to the study participants, an introductory letter detailing the purpose of our study was served to each respondent before interview was granted. Target population is the exact units where samples are selected for a study (Creswell, 2009). Our target population was mainly residents of Denmark, who are skeptical about the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. We monitored and gauged the participants’ vaccine skepticism through physical and virtual spaces. For the study participants from Denmark and Ghana, we selected them through our physical and social media engagements. For those from USA, we monitored those who expressed skepticism on the COVID-19 vaccine through their social media handles.

In total, we solicited firsthand data from 14 study participants, 8 of them being resident in Denmark. We also interviewed 6 other study participants outside Denmark—3 in the USA and 3 in Ghana to complement the ones in Denmark. Strategically and knowing that the topic at hand is a global issue, the eight interviews in Denmark, the six—from Ghana and USA precisely—and the carefully selected secondary data complemented and enriched the findings of the study. We have chosen to interview people from various nationalities to extract diverse opinions on the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccination campaigns, and vaccine skepticism. Reasons why some people in Europe, Africa, and North America choose not to vaccinate might not be the same, due to differences in trust levels for pharmaceutical companies, healthcare systems, governments, history of vaccination, religious and cultural beliefs, myths, and other practices. However, the views of the selected participants might not be representative of their countries of origin or residence. We, therefore, adopted relevant secondary data to address the possible representational weakness.

In terms of gender representation, 5 females were purposively selected, while the remaining 9 were males. Distinction is made on gender grounds because preconceived mindsets on sexual reproductive health issues relative to vaccinations and their side effects are perceived differently based on the biological sex of people. Hence, decoupling the study participants on gender enables us to uncover a shared understanding of their viewpoints.

Purposive sampling is utilized in this study. It is a sampling technique used when the researcher selects the research participants based on their own judgment. Here, researchers engage interviewees who can give relevant information on the subject matter (Bryman, 2016). Therefore, all the 14 study participants were purposively selected. In terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria, we included only those who were passionate, and interested in our topic—COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing vaccine skepticism. Additionally, those selected were equally willing and ready to give us relevant information concerning the subject matter. Participants with low interest levels, not passionate about the topic and not willing to give us relevant information, were excluded from the interview process. Below is the background information of the interviewees. To ensure anonymity, we assigned the following codes to the participants (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Profile of the study participants

| Codes | Sex | Residence | Age | Nationality | Education | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR | Male | Denmark | 50 | Dane/Ghanaian | Dental nurse | Dental assistant |

| TB | Male | Denmark | 36 | Dane | MA-Organization and Leadership | intern |

| HH | Male | Denmark | 38 | Dane | MA-Marketing and Consumption | Danish army |

| LS | Female | Denmark | 25 | Dane | MSc-Development and International Relation | Social worker |

| GJ | Male | Denmark | 30 | Uganda | MSc-Business Administration and Philosophy | Unemployed |

| SF | Male | Denmark | 38 | Rwanda | MSc-Building Energy Design | Concrete technician |

| ND | Female | Denmark | 36 | Burundian | Radiography | Radiologist |

| DD | Male | Denmark | 37 | Cameroonian | MSc-International Business | Entrepreneur |

| SS | Male | Ghana | 50 | Ghanaian | BSc-Banking and Finance | Financial analyst |

| AS | Male | Ghana | 30 | Ghanaian | BA-Political Science and Sociology | Account analyst |

| RM | Female | Ghana | 35 | Ghanaian | MSc-Marketing | Sales consultant |

| AT | Male | USA | 34 | Nigerian | MSc-Data Science | Data analyst |

| AK | Female | USA | 27 | Gambia | MA-Global Political Economy and Finance | Social worker |

| WL | Male | USA | 45 | Ghanaian | MSc-Program and Project Management | Municipal coordinating director |

Source: Field Survey, 2021

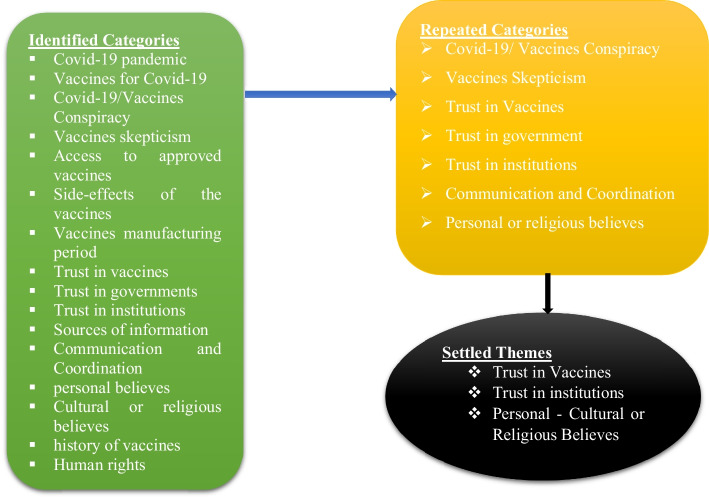

Fig. 2.

Theme development using the Voyant analytic software

Interviewing Techniques and Interviews

A semi-structured interview guide was the primary data collection used due to its prospect for flexibility, explanatory answers, flexibility, in-depth exploration of participants’ viewpoints, and iterative nature (Bryman, 2012). Questions asked were basically about the COVID-19 and vaccination skepticism. Examples of questions we asked include the following: In what ways do trust or distrust in vaccines influence your vaccination decision? Can you explain to us why and how trust or distrust in the healthcare institutions/pharmacies/vaccine-manufacturing companies impacted on your vaccination drive? Tell us how your cultural, religious, and personal beliefs make you decide to or not to vaccinate.

Due to the social distancing protocols, all interviews were conducted in English via zoom meetings. The interviews lasted between 30 min and 1 h. Interviews were recorded transcribed verbatim to avoid data misrepresentations. In terms of data quality and validity, we sent parts of the transcribed interview data to all the participants to confirm their views (Bryman, 2016). Again, an external researcher was asked to appraise our data and our findings (Bryman, 2012). Subsequently, we integrated the recommendations of the study participants and external researcher into this paper to increase the validity of our data and research findings.

Data Analytic Approach

Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data based on the formulated problem. Thematic analysis is a method of interrogating data to retrieve significant understanding of the study participants’ standpoints on matters of importance (Bryman, 2016). It is therefore a treasured method for scrutinizing the content of responses from data collected from the semi-structured interviews (Creswell, 2009). It permits us to categorize and explore the participants’ responses and decode them to establish collective viewpoints and patterns among study participants (Creswell, 200).

Towards identifying the themes for analysis, we deployed the Voyant data analytic software. Social science researchers (such as Eddine, 2018; Hendrigan, 2019 and several other) have used the Voyant tool in their research for various purposes. For instance, Hendrigan (2019) used it to reveal word pattern in the research output of applied science faculty. Also, Eddine (2018) deployed the Voyant tool to analyze the text and find the most common words in the text and their relationships. For our study, we used the Voyant tool to note commonly used words and phrases in the dataset. We also read through the data and identified certain categories, repeated categories, and finally settled on three main themes to guide the analysis: trust in vaccines, trust in institutions, and personal/religious beliefs.

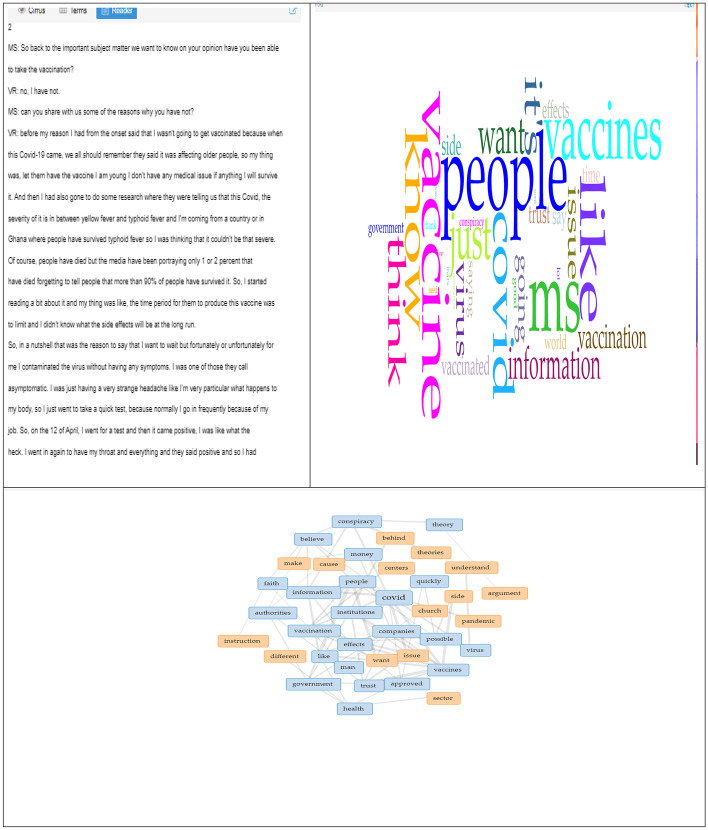

The below figure portrayed concurrent words extracted from the dataset using the Vouyant analytic software (Fig. 1). The bigger the word, the more frequent it was mentioned by the study participants during interviews. For example, the word “people” were mentioned the most (275 times), followed by vaccine (235 times); COVID-19 had 163 notes (Fig. 1). Afterwards, we extracted certain categories, repeated categories, and finally settled on the main themes for the analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Commonly used words using the Vouyant software

For ethical consideration purposes, since the COVID-19 and its accompanying vaccination campaign are current geo-political issues, skepticism towards the latter makes our study participants quite inaccessible due to the fear of possible stigma they might face if their identity is disclosed. In this respect, confidentiality, freedom to participate, and anonymity were assured. We reported their perspectives with trustworthiness as shown in our data quality assurance.

Analysis and Discussions

The all-embracing purpose of this research is to examine why some eligible people are hesitant to the COVID-19 vaccination despite assurances by the authorities.

Summary of Findings

With the reviewed literature and interview data, we came across several reasons for vaccine hesitancy towards the COVID-19 virus. These include trust and side effects of the approved vaccines, trust in governments, trust in institutions, personal or religious beliefs, access to vaccines, and past experiences about vaccines to mention but a few (Lopez, 2021; Mach, et al., 2021). For the purpose of this study, we have narrowed the scope to three main themes—trust in vaccines, trust in istitutions, and personal, cultural, or religious beliefs—to guide the analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of major findings

| Occurrences particular to the study participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | Topical Experiences from the dataset | GP | DP | AP | Experienced by ONE, SOME or ALL participants |

| Trust in vaccines |

* The speedy process of developing the vaccines and the emergency authorization of the vaccine make some people vaccine skeptics *The perceived safety and trust of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine *The vaccine could potentially change the host DNA *General side effects of the vaccines are worrying |

+ − − + |

+ + + + |

+ + − + |

Some Some One Some |

| Trust in institutions |

*Low trust in government *Miscommunication between government and health authorities *Government’s handling of previous pandemics is problematic *Pharmaceutical companies profiting from pandemics *The mistrust in the government and the institutions who are making the vaccines does not want to take responsibility for themselves |

+ + − − + |

− + − − + |

+ + + + + |

Some All One Some Some |

| Cultural or religious beliefs |

*The vaccines are intended to reduce the fertility rate of black people *Immunization is incongruous with “God’s will” *Religious people more likely to side with their religious belief system over science whenever disputes such as vaccine skepticism arise *God is the ultimate protector of humans |

+ + + + |

− − − − |

+ + + + |

Some Some Some Some |

+ = experienced by participants, − = not experienced by participants

GP Ghana participants, DP Denmark participants, AP American participants

Trust in Vaccines

Vaccination is often recognized as an effective measure to either eliminate or reduce to the barest minimum the burden of infectious diseases by health authorities and the medical community. Effective vaccination can lead to herd immunity, thereby preventing many infections or, at worst, possible casualties, that is, high number of deaths to be recorded from the targeted population. That said, the success equally depends on the willingness or otherwise of individuals to get vaccinated (Neumann-Böhme, et al., 2020).

Not farfetched, a sample size of 7664 participants from six European Nations shows the rate of vaccination willingness against the COVID-19 provided a vaccine could be available to have ranged from 80% in Denmark and the UK and 62% in France. Also, 10% hesitancy noted in Germany and France while 28% remained on the fence (Ibid). Another study with 9889 participants placed the vaccination rate of willingness to be ranging from 79% in Denmark to 38% in Hungary (Lindholt et al., 2020). Besides, 7% (2.1 million Canadian adult population) was shown to be unwilling to get the COVID-19 vaccines (Duenas & Mangen, 2021). Moreover, a study of 2345 adult Ghanaians in sub-Sahara Africa about the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy indicated that almost 51% of the urban adults over 15 years are likely to take the COVID-19 vaccine provided it is made generally available. About 21% unlikely to take the vaccine, and 28% recorded to be undecided (Acheampong, et al., 2021).

Furthermore, a study by Acheampong et al. (2021) and Neumann-Böhme et al. (2020) revealed 28% of the study participants being undecided when it comes to taking vaccine against the COVID-19 pandemic. Imperatively, some degrees of hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccines are shown across board. Trusts in vaccines appear to be one of the crucial factors behind the hesitancy thus calling for its proper interrogation. This will be done taking into consideration vaccine protocols, side effects of the vaccine, and history of vaccinations.

Vaccine Protocols

The safety protocols regarding vaccine production and deployments could lead to trust or mistrust about the said vaccine. If the public has reasonably positive evidence, relative to the production and distribution of a vaccine, it enhances the confidence and trust of the vaccine. On the contrary, lack of enough evidence, on whether the manufacturing and distribution of a vaccine followed due process, can reduce public confidence and trust in the vaccine (Petersen et al., 2021).

We can argue that the speedy process of developing the vaccines and the emergency authorization for their usage are major concerns for some people/or vaccine skeptics and a drawback for their trust and willingness to taking the vaccines. For instance, it has been revealed that almost one-third of unvaccinated Americans are more likely to get vaccinated if the vaccines got full approval (Lopez, 2021). As a complement and based on our primary data, we can add:

“Because the procedure laid out for vaccines to be used in humans have not been followed and the guidelines set up by the same companies that are promoting vaccines for the COVID-19 have not been duly followed, the protocols were not fully respected, the samples collected were not duly labelled” (DD, 2021)

“The emergency approach is what is making me to pull some brakes you know normally a vaccine has to be tested and retested for about 5 years for it to come out to the public… my thing is it was produced too early for me to be a guinea pig” (VR, 2021)

“In the beginning when the first vaccine came, I think it was the one that government refused AstraZeneca, I think 2 or 5 people died of that one, so that one has made me think that I cannot trust this vaccine. I think it was made too fast” (SF, 2021)

The perceived safety and trust of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine is low especially among those already hesitant to vaccine (Sønderskov et al., 2021). Indeed, whichever angle one looks at trust about the vaccines for the COVID-19 pandemic, the protocols regarding production and early results cannot be swept under the carpet. Inferring from the three quotes from the primary data, an overarching concern is the speedy or emergency process of coming out with the vaccines. Though the COVID-19 is widely accepted as a pandemic, the emergency authorization of the vaccine could appear logical. However, some individuals are also skeptical moving from the comfort zones to accepting new things, especially vaccine that could potentially change their immune system or DNA.

Accordingly, DD (2021), a male immigrant from Cameroon living in Denmark, held the view that the vaccine protocols for the COVID-19 have not been duly followed or respected and the samples collected were not duly labelled hence his distrust and hesitance to taking the vaccine. Also, VR (2021), a female Dane but originally from Ghana, considered the process to be too quick for her to be used as a guinea pig. Besides, ND (2021), a female refugee from Burundi living in Denmark, held a view like that of VR (2021) that the vaccine-manufacturing process is too fast to be used for experiment. At last, SF (2021), a male refugee from Rwanda living in Denmark, considered the reports about few fatalities regarding the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and the fact that the vaccines generally were made too early under emergency authorization, to be the basis of his distrust and unwillingness to take any at the time of the interview.

Essentially, one-third of the unvaccinated Americans who would only be more likely to get vaccinated upon full authorization of the vaccines by food and drugs authority in the country and those with the perceived low safety and trust of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in Denmark (Lopez, 2021; Sønderskov et al., 2021) goes to complement and strengthen the concerns of our interview participants. With the same task, participant HH (2021), a male Dane, and AT (2021), a male immigrant from Nigeria living in the USA, narrated:

“No, I do not trust them, there is a whole issue about them being developed fast, that is one thing… like there is a disclaimer saying we do not take responsibility for what may happens, And I think if they would not take responsibility, why should we take it” (HH, 2021)

“Let me give an instance, some people have taken two shots first and second jab, they said they need booster and now the immunity is reducing again after taking all those vaccines. So, what is the point of taking them in the first place… So, it is like, there is a declining curve of the efficacy of the vaccine for this COVID-19” (AT, 2021)

With the COVID-19 vaccination willingness study across eight European countries, Denmark recorded the highest with 79%, UK 65%, Italy 54%, Germany 54%, Sweden 50%, USA 48%, France 41%, and Hungary 38%. Nevertheless, in six of the eight countries studied, more than 10% revealed to be totally against the idea to get the vaccine (Lindholt et al., 2020). Several reasons including the vaccine protocols are accountable for this revelation.

Furthermore, there is the disclaimer that shields the vaccine companies from taking responsibilities for what might have happened to individuals after they received the vaccine. Indeed, some of the people who have had the vaccines still have been infected with the virus. This is a big barrier towards the vaccination drive for the COVID-19 pandemic and the global herd immunity. This situation is applicable to both the 10% indicated above and the interviewees, who are hesitant to take a step away from their initial positions. Understandably, trust is the cornerstone for vaccine acceptance or denial (Acheampong, et al., 2021). Apparently, some people have issues regarding who takes the responsibility in case something goes wrong upon taking the vaccines. Thus, after taking the vaccine, one is still prone to being infected with the virus. However, until the society can be assured that after this shot there will not be another one in the name of a booster, mistrust and hesitancy would abound.

Inferring from theory, it has been articulated that the official discourse or regime of truth (vaccination as a strong weapon to defeat the COVID-19 pandemic) has a strong tendency to carrying the society along because of the power behind it in terms of experts (scientist and vaccine companies), the governments, and media outlets. Yet, dissent (vaccine hesitancy) cannot also be glossed over because the society did not always follow the dominant discourse (Morrow, 2018). Also, the communicative discourse (vaccination against the COVID-19 pandemic is the only way to save life and livelihood) could either enhance the vaccine skeptics to accept the need to get vaccinated or lead to mistrust and hesitancy towards vaccination (Mehta, 2011).

In a pandemic, uncertainty cannot be completely avoided and the possibility for different countries to look within and act differently is also high. But be that as it may, the daily, weekly, or monthly discourse about vaccination against the COVID-19 pandemic can attract wide acceptance or resistance depending on how the official discourse resonates with society. To support this, it could be argued that information from diverse channels have significantly promoted vaccine hesitancy among Ghanaians (Acheampong, et al., 2021).

Side Effects of Vaccines

Furthermore, one issue that cannot be ignored considering hesitancy towards vaccines is the side effects of the vaccines. People often mistrust and hesitate to take a vaccine based on known or unknown side effects of the vaccine in question. The cases of vaccine for the COVID-19 pandemic are not far from the norm, and we want to present to readers the perceived side effects of the vaccines, and whether there are barriers to people’s willingness to take the vaccines. Inferring from the primary data, ND (2021), a female refugee from Burundi living in Denmark, and GJ (2021), a male refugee from Uganda living in Denmark, stated:

“I have heard about people at least two who have died of it, there is a priest in Australia… one who died in Belgium because of the same issue… from a reliable source in Norway, of two women they had reached their menopause but after they got the injection they have started bleeding uncontrollably” (ND, 2021).

“It was a hundred people 6 people had side effects especially from UK and in Denmark, 2 - 3 people recorded… I'm hearing ladies that have had this saying that their menstrual cycle is just gone bisect” (GJ, 2021).

To support the above from empirical data, a study in Ghana involving 1605 Health Care Workers to find out the possibility for them to partake in a COVID-19 vaccine trial and accepting the vaccine if made available revealed 70% acceptance rate, but only 48% for the trial. All in all, a high hesitancy was found among the female and those with less education in the sample. The reasons thus ranged from fear, safety concerns, and lack of trust among others (Alhassan et al., 2021). Also, trust in the vaccines can emanate from concerns of the immediate and future side effects such as few days of aches, fever, and fatigue or, in unusual cases, about potentially blood clots (Lopez, 2021).

As an exploratory study, we argue that the perceived or real side effect cases of the available COVID-19 vaccines do have a stalling impact on the study participants’ edge to take the vaccine against the pandemic. In fact, both study participants, ND (2021), a female refugee from Burundi living in Denmark, and LS (2021), a female Dane, and therefore, although yet to be proven scientifically, side effects of the vaccines on women’s menstrual cycle would invariably heighten their distrust and hesitancy to vaccinate against the COVID-19 pandemic. To cure the mistrust and skepticism towards the vaccines owing to the side effects, more trust building mechanism needs to be employed—coordination and collaboration—among stakeholders who are in the vaccine’s productions and deployment, and positive scientific communication to the socio-demographic groups about possible side effects of the vaccines will be important.

Indeed, we are reminded that society build trust or mistrust based on how they view the performance of those tasked with the leadership (vaccine companies, governments, and healthcare systems) (Keele, 2007; Trevena, et al., 2013). In confirmation, those established to be hesitant towards taking the COVID-19 vaccines are also having trust issues towards the vaccines and leaders driving the vaccination agenda. Besides, how the side effects of the vaccines are constructed discursively—the diagnostic and prognostic discourses—and communicated to the public as normative discourse equally have a huge impact on vaccine acceptance or rejection (Schmidt, 2006, 2008). And how society—especially those hesitant towards the vaccines—view the official discourse (vaccination as the main panacea to the opening of the world economy and the efficacy of the vaccines surpassed the side effects) as the unquestionable truth (Peters & Burbules, 2004; Williams, 2014) will ultimately determine the acceptance or hesitancy of the vaccines.

Therefore, more room and work need to be done to build trust between and among stakeholders. In the same vein, the rules and regulations about the vaccines and the COVID-19 pandemic in general require proper design and coordination. In fact, the disharmonized approach by the different stakeholders leads to confusion and distrust, especially among those already hesitant to vaccines. Importantly, the discursive discourses for the vaccination campaign demand re-strategy and focus with the objective of targeting different socio-demographic groups differently.

History of Vaccinations

Another significant factor breeding trust or mistrust and hence acceptance or refusal of vaccines is knowledge regarding the consequence of previous rollout vaccines. Vaccines and vaccination are noted to be part of human and society development for quite a reasonable period (Belluz, 2019; Jacobson, 2015). However, past vaccines intended to enhance health care delivery have created unintended challenges leading to irreparable damages and deaths in worst but rare cases, thereby entrenching vaccine hesitancy or total rejection by some people in the society (Ibid). Extending this to primary data, the following was narrated by a study participant.

“You know there has been so many vaccines in the past… it happened way back some time in Kano in Nigeria and those kids, some died, and some were permanently paralyzed and so many bad things happened to them. So that is just an example I am giving you” (AT, 2021)

In this regard, empirical study revealed a total boycott of polio vaccine in Nigeria between 2003 and 2004, which led to a fivefold increase in the polio cases in the country between 2002 and 2006. Several reasons including what has been alluded by the immediate above study participant (Afolabi & Ilesanmi, 2021) were noted as reasons for the total boycott.

We could as well argue that the dominant discourse (trust in the vaccine against the COVID-19 pandemic) could only triumph depending on how the elites persuade the society in the official discourse. This will largely hinge on the level of trust society will keep towards the narrative about the side effects of the vaccines, and the whole campaign about the vaccination (Larson, et al., 2018). For instance, has the public accepted the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat to the health, socio-cultural, and national security as the regime of truth or officially constructed discourse. In addition, has the society accepted the communication that vaccination in the best solution to saving the health care systems, life, and livelihood. Moreover, was the constructed discourse about past vaccine fallouts strong enough to convince those hesitant to accept the new narrative or official discourse. In sum, the official discourse is quite crucial for trust building and acceptance or denial of the vaccine’s rollout.

Trust in Institutions

Trust in governments, trust in COVID-19 vaccine developers, and trust in healthcare systems are the three sub-headings to facilitate reading and comprehension under this theme: trust in institutions.

Trust in Governments

The level of trust and confidence in government, in the ongoing COVID-19 vaccine skepticism, cannot be overemphasized. For example, a worldwide survey on possible tolerance of a COVID-19 vaccine from June 2020 discovered that citizens of Asian countries such as China and South Korea, with strong trust in central governments, appeared to be much responsive of the COVID-19 jab (Lazarus, et al., 2020). Contrarily, in many other countries, such as the USA, political tussles engulf the discourses of the COVID-19 vaccination agenda, and since levels of trust in the government are at a historic low (Pewresearch, 2021), willingness to get vaccinated might equally be low too.

A brief travel through our interviews is illustrative of the importance of trust as indicated by interviewee LS (2021), a female Dane posited:

“…We do hear the press briefing from the government…. And they are saying that the vaccine is the only solution. I hear that they said all the hospitals are filling up and all we cannot even keep up. But then I hear from doctors and nurses say, well that's not true... and then the government putting another narrative on it and saying it is because of the virus and that does not make them trustworthy” (LS, 2021)

Clearly, trust in government communiqué is an important indicator for citizens’ vaccination decisions. In Denmark, the government argued that vaccination is the surest way to restore normalcy in the country. In doing so, attempts to heighten the impacts of the virus in Denmark in terms of hospitalization were made by government and its allied agencies through press briefings. However, certain responses from medical teams do not share that opinion, as alleged by the study participant LS. This makes the interviewee doubtful whether the government can be trusted.

As argued in our theoretical chapter, faith in the source of information and the information itself (Chuang et al., 2015) and trust in government, media health, experts who publicize the information are very relevant factors in people’s vaccination drive (Trevena, et al., 2013). Again, actors construct and communicate ideas within given institutional contexts (Schmidt, 2008). That is the main reason why government’s position differ from the health authority in terms of over-hospitalization, supposedly caused by the COVID-19 virus.

In furtherance to how belief in government had influenced the citizens’ COVID-19 vaccination drive, we inferred from online cross-sectional survey conducted in the cities of Sydney, Melbourne, London, New York City, and Phoenix with a sample size of 402, 298, 291, 1204, and 500, respectively. In total, 4898 people opened the survey, while 78% of the eligible participants completed the survey (Trent, Seale, Chughtai, Salmon, & MacIntyre, 2021).

In terms of trust in their respective governments relative to the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants rated confidence in governments at 68% in Sydney, 66% in Melbourne, 45% in London, 37% in NYC, and 33% in Phoenix. To explain how these confidence levels in the five cities affected their willingness to vaccinate against the COVID-19 virus, the result revealed that 291 (72%), 231 (78%), 205 (70%), 849 (71%), 378 (76%) attributed to Sydney, Melbourne, London, NYC, and Phoenix, respectively (Trent, Seale, Chughtai, Salmon, & MacIntyre, 2021).

Furthermore, we argued that trust in government amidst the COVID-19 pandemic was higher in Sydney (68%) and Melbourne (66%), while low in the trident of London (45%), NYC (33%), and Phoenix (33%). Indeed, higher trust levels in Sydney and Melbourne also commensurate with higher willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccination among the study participants at 72% and 78%, respectively. Inasmuch as the various governments’ confidence levels in the cities of London, NYC, and Phoenix relative the COVID-19 pandemic was low; the vaccination willingness by the participants was however high (Ibid).

Suffice to add, high trust in government has resulted in increased drive to vaccinate in Sydney and Melbourne unlike in London, NYC, and Phoenix. Therefore, the above-analyzed data could not conclusively answer our assumption but addresses our research question. Factors such as trust in the vaccines, trust in the medical experts, and real threat of the virus among others could explain why the study participants in London, NYC, and Phoenix are willing to get vaccinated even though they have low confidence in their respective governments.

Trust in COVID-19 Vaccine Developers

Moreover, trust in the COVID-19 vaccine developers—pharmaceutical industries—is a determining factor with regards to vaccination drive and/or vaccination skepticism. Also, historical scandals, racketeering, published assertions of misconduct and greed involving pharmaceutical companies, the unwillingness by pharmaceutical companies to waiver the COVID-19 vaccines property right, and the rise of what is popularly termed vaccine billionaires have sown seeds of doubts and discontent among people (Akhtar, 2021).

More so, Johnson and Johnson in 2013 settled a federal investigation relating to the promotion fraud of several drugs. Again, 46 US states sued Pfizer, plus 26 other drug-producing companies last year, over allegations of drugs’ profiteering. In 2009, Pfizer—the pioneer of FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccine—settled the second largest healthcare fraud case in the history of the USA. This was after they are being sued for misleading advertising of an anti-inflammatory drug. Additionally, in the mid-2010s, measles reemerged in USA despite assurance by CDC that it was defeated in 2000 (Ibid). All of these create and spread doubts relative to the COVID-19 vaccines produced the pharmaceutical companies.

As indicated earlier on, big pharmaceutical companies are lobbying to prevent the waiver of the intellectual property rights for the COVID-19 vaccines they developed. The waiver could have allowed smaller pharmaceutical companies—especially those from the global south and other countries with low investment in Research and Development—to start vaccine production to increase output (Akhtar, 2021).

Additionally, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are getting combined profits of $65,000 every minute. It has been claimed that these two companies could make $34 billion profit before tax in the year 2021. This will translate into over a thousand dollars a second, $65,000 a minute or $93.5 million a day. Indeed, the alleged cartels these companies hold have created five new billionaires because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This amounted to a combined net wealth of $35.1 billion (ReliefWeb, 2021).

Another community-based survey in India responded by persons who had not received the COVID-19 vaccine emphasized that the vaccines make lot of money for the pharmaceutical companies. In fact, majority of the participants believed so: 120 (21.3%), 160 (28.4%), 98 (17.4%), 95 (16.8%), and 91 (16.1%) on a measuring scale of strongly agree, agree, neither agrees nor disagrees, and strongly disagree, respectively (Danabal et al., 2021). This widely held view of profiteering nature of the vaccine manufacturers goes a mile to make people mistrust them and obviously become vaccine skeptics. The combined implications of these result to deep-rooted trust issues for the pharmaceutical companies, which ultimately makes people vaccine intolerant.

To firm up the assertions seen in secondary literature, a quick glance at our transcribed interviews offers the following revelations as well. Study participant HH, a male Dane, again posits:

“…The mistrust in the government and the institutions who are making the vaccines does not want to take responsibility for themselves. If I take it, right now there is a disclaimer saying that, if I get cancer on the road or whatever because of that, it was my choice to get the vaccine and I am responsible for the problem they made” (HH, 2021)

In terms of the profiteering aspect of the vaccine production and marketing, study participant AT, a male immigrant from Nigeria living in the USA, articulates:

“…It is more like capitalistic system, so like I feel there is a lot of vested interest, in terms of monetary interest from the vaccine itself, so like they are monetizing it too much. So, like most of the pharmaceutical companies, they are trying to make money from the pandemic…” (AT, 2021)

The above suppositions from interviewees HH and AT only add to the existing lack of trust in the motives of the vaccine-manufacturing companies, due to their alleged profit drive, reluctance to waiver property right, and unwillingness to take responsibility of future damage. Accordingly, study participant HH argued that the pharmaceutical companies being shielded from taking responsibilities and possibly be sued for health damages (for cancer and other chronic health condition in the future) only heightened his mistrust in them and the vaccines as well. With the COVID-19 manufacturing companies currently lobbying with President Joe Bidden to maintain their property right, Akhtar (2021) supports AT’s claims that the pharmaceutical companies have vested economic interest in the pandemic, rather than saving lives.

We could contend that the citizens monitor the performance of leadership (in terms handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and general governance), changing their confidence in the government as and when the need arises (Citrin, 1974), with the efficacy and history of previous vaccination campaigns, motives of vaccine companies being key antecedence. Again, faith in the pharmaceutical companies that produce and supply the vaccines, reliability and expertise of health services and specialists, and finally the enthusiasms of authorities who make key decisions on the vaccine efficacy, as well as previous history, together go a long way to influence people’s vaccination choices (MacDonald, 2015) as expressed by study participants HH and AT.

To bring empirical data to bare, a survey carried out to respond to distrust in pharmaceutical companies amidst the COVID-19 vaccination plan shows 27% of the responses distrust the vaccine-manufacturing companies, out of 627 respondents from Sydney, Melbourne, London, New York City, and Phoenix. Indeed, the distrust rate was 2%, 5%, 8%, 2%, and 9%, respectively. However, with these low trust levels, willingness was still over 70% in all the cities (Trent, Seale, Chughtai, Salmon, & MacIntyre, 2021). Reasons such as trust in the healthcare system and the reality of the virus could account for the high vaccination rate.

Trust in the Healthcare Systems

Additionally, results from a recent polling in the USA revealed much of the public have lost trust in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other major government institutions. Therefore, proposals to get people vaccinated are received with huge skepticism (Lopez, 2021). Relative to the issue of distrust in the healthcare system, certain lived historical experiences and/or perspectives are rather very much entrenched, thereby influencing people’s COVID-19 vaccination decisions. For instance, black Americans allegedly harbor lower levels of trust in the USA’s healthcare system due to reported systematic and outright maltreatments, such as being medically experimented on without their prior willing consent, their continuous unpalatable experiences when they go to doctors and hospitals which could culminate into them distrusting the COVID-19 vaccines itself (Lopez, 2021).

It is important to add that the above analyzed content resonates with our primary data interviews. For example, study participant AS, a male Ghanaian resident in Ghana, says:

“I only heard some rumor...some people on social media and other channels saying that...the vaccines are attempts to reduce the high fertility rate in Africa” (AS, 2021).

The above supposition relates with Lopez (2021) polling which says that some African-Americans see the vaccination as a ploy to use them for experiments. Theoretically, it could be argued that trust and faith in the healthcare system and healthcare specialists involved in delivering and dispensing vaccination to people and public health researchers responsible for approving and endorsing the vaccine’s efficacy and effectiveness (Larson et al., 2015) impact people’s vaccination drive.

Notwithstanding, a survey conducted in the USA (Lazer et al., 2020) from 16 to 24 April 2020 with a sampled size of 22,921 conversely revealed that the most trustworthy and dependable groups expected to do what is right on COVID-19 were doctors, hospitals, scientists, researchers, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with the pharmaceutical companies having very low trust level. In terms of the statistical data, 47% trusted the CDC a lot, 72% trusted the hospitals and doctors a lot, 58% have faith in the scientists and researchers, and only 28% trusted the pharmaceutical companies a lot.

To relate the issues of trust in the healthcare system and desire to receive the COVID-19 jab in the USA, as of 15 December 2021, 72% of the populace has at least one dose of COVID-19 jab, 61% of the citizens are fully vaccinated, and 16.7% have had the COVID-19 booster jab already (NYTIMES, 2021). Even though the people do not trust the pharmaceutical companies, as indicated in the previous sub-theme, the huge trust in the USA healthcare system—doctors, hospitals, and health experts—could be the reason why the vaccination’s success rate is quite commendable.

In Denmark for instance, where there is so much faith and confidence in the healthcare system, willingness to vaccinate has been very impressive: 79% in Denmark as compared to 38% in Hungary in using a sample size of 9889 (Lindholt et al., 2020). The combined effects of the faith in the healthcare system and willingness to vaccinate result in 77.3% of the population having been fully vaccinated with 80.4% having at least a single dose of the vaccine.

Cultural or Religious Beliefs

Vaccine refusals based on religious grounds have a distanced history. For instance, Edward Jenner encountered serious criticism from members of the clergy when he created the first vaccination in 1796. The clergy contended that immunization is incongruous with “God’s will.” With this premise, religious concerns about vaccines’ skepticism have since grown and widely accepted in many parts of the world (Belluz, 2019). Moreover, several adherents of religious groups have in some circumstances come up with religious rationalizations for vaccine refusal. In certain instances, religious leaders used their authority to turn people off immunization since some of them have also been targeted with vaccine propaganda (Ibid).

In recent memory, a survey of 140,000 respondents’ ages 15 and older in more than 140 nations shows some impacts of religious beliefs toward vaccine hesitancy. Even in developed and modern continent like North America, religious people were more likely to side with their religious belief system over science whenever disputes such as vaccine skepticism arise. Indeed, this specific finding was propelled predominantly by the USA, where measles has been multiplying among religious neighborhoods in states that have approved religious vaccine exclusions (Gallup, 2019).

Turning to our transcribed interviews, to supplement the secondary data brings forth the following religious reasons for being COVID-19 vaccine skeptical by participant AT from a Nigeria born man resident in USA:

“…I am a man of faith… I believe God is the ultimate protector of humans, that's my belief… I am a Christian, so and under my Pentecostal faith, we don't really believe in that vaccine. So, I might think that is the greatest motivation” (AT, 2021)

The above perspectives reveal that religious beliefs could create seeds of vaccine skepticism among their ardent ideologues. For participant AT, his association with the Pentecostal Christianity faith makes him vaccine hesitant. He believes that God is the ultimate caretaker of all affairs in this life, and everything in the world. With this, he needs no vaccine to protect himself, and to booster his immune system against the COVID-19 pandemic. Essentially, we could conveniently put him in the category of vaccine skeptics’ hardliners—very difficult to convince to accept vaccines due mainly to their entrenched religious beliefs.

As indicated by Belluz (2019), Gallup (2019), and study participant AT, faith in God greatly influence people’s vaccination decisions. Faith, trust, and confidence and its associated discourses resonate perfectly with trust theory. In fact, bolstering trust and confidence correlates positively to greater trust in whatever people do or pay allegiance to (Twyman et al., 2008). Besides, social trust and confidence relates with increased vaccine tolerance, and acceptance rate (Larson, et al., 2018). Contrarily, some religious fanatics find immunization horrendously abominable, but have so much trust and confidence in the protection from God—divine protection these religious hardliners called it. They are very much convinced that vaccination is incompatible to “God’s will.” This negative relationship between trust and vaccination—informed by deep-rooted religious beliefs—increases the incidence of vaccine rejection among those adherences.

Another study shows that 10% of Americans are of the view that getting a COVID-19 vaccine conflicts with their religious beliefs and practices. Also, 51% of US citizens are in favor of admitting a religious exemption if the person asking for the exemption has certification from a spiritual and/or faith leader saying that the vaccine goes against their religious beliefs and practices. However, in terms of mandatory vaccination, 58% of US citizens say that people should be allowed to have religious exemptions from the COVID-19 vaccine. It was alleged in the same study that: “So many people in diverse religious communities believe that our bodies were created by god, and we need to cherish and protect those, and that we have an obligation to the common good.” (NPR, 2021).

To be able to convince and rope in the antivaccine groups, informed and hardened by religious belief systems, wider stakeholder cooperation and endorsement should be encouraged, and to make them powerful in persuading, normative discourses need be fulfilled by bringing in line existing problems and what needs to be done to remedy them that resonate with the people (Schmidt, 2006). A participant in NPR (2021) survey argues: “When pastors encourage vaccination and mosques hold vaccine clinics, more people get vaccinated. Faith-based groups remain ready to play our role, but we need partners.” This standpoint resonates with communicative and coordinative discourses.

Furthermore, participant JK (2021), a female immigrant from Gambia living in the USA, and AS (2021), a male Ghanaian, expressed the following views regarding personal, religious, or cultural beliefs:

“I would rather have covid than have the vaccine… I wouldn't take another vaccine; I don’t think it’s the solution… I think that we should be free to choose, I think that it is human rights to be able to choose what you do with your body” (JK, 2021).

“You know I am still young and will like to get more children if it is possible, so I think I will not forgive myself if something happens to me because I took the vaccine” (AS, 2021).

Inferring from the statements, one can easily deduce a strong personal belief held by the study participants. With all the news and evidence of the COVID-19 pandemic on diverse sources to the public, it speaks volumes in terms of personal conviction for one to prefer being infected with the virus than going in for the vaccines. The hidden meaning is that the participant and persons with similar viewpoints would be hard nuts to crack when it comes to convincing them to take the approved vaccines.

Upon further interrogation, the study participant insisted that the best way to handle virus pandemic like the COVID-19 is to encourage the society to live a healthy life by adhering to good eating habits and lifestyle. What equally stands out is the emphatic assertion that the vaccination campaign should not be separated from the fundamental rights of individual especially regarding what should be deem necessary to be injected into a person’s body. Once a person merged his or her personal beliefs with law, issues immediately become complicated. Additionally, study participant DD (2021) indicated that no one should be mandated to take the vaccines until all the vaccines proven scientifically not to have any adverse effects on humans. Besides, AS (2021) tie his personal believes to being young and wanting to have an additional child to the daughter; hence, not being certain about what the vaccines might add or subtract from his system, he pontificated believing personally not to be ready to take the vaccines regardless of any assurance.

Furthermore, a Ghanaian private legal practitioner has triggered the right to information act—Act 2019 (Act 989) of the 1992 constitution of the republic of Ghana—on the COVID-19 vaccines in the country. Accordingly, the action was necessitated following a new directive by the Ghana Health Service and Ghana Airport Company that effective December 14, 2021, all travelers into or out of Ghana including citizens must show proof of full COVID-19 vaccination or be prepared to undergo the vaccination upon arrival. He stressed that the directive would make him lose the constitutional guaranteed freedom of movement, which embodies the right to travel into or out of the country, even without fully vaccinated against the COVID-19 vaccines (Ghanaweb, 2021). In essence, he wants the state institutions to marry their directive with the constitutional provisions especially relative to Sects. 21, 22, and 25 of Public Health Act (Act 851 of 2012) that exempts mandatory vaccination for people with natural immunity or where the vaccination will pose health risk to them.

We could make a point that where personal beliefs, whether informed by culture or religion, are contrary to authorities’ directives in this context, directive to take the COVID-19 vaccines, distrust, opposition, and denial or refusal to follow the official discourse are strong—the best way to get out of the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic is for almost everyone to get vaccinated by and large, when the dominant discourse is not seen to be persuasive but rather coercive, and when the followers could not be convinced beyond reasonable doubt that the official directives or discourse taking their freedom or edging them to take the vaccines is a national security threat, and the only plausible alternative to save them and the economy, then opposition from some of the citizenry will be inevitable (Leonardo, 2003; Morrow, 2018).

Triangulation of Perspectives

We discovered that participants from the global South largely distrust their governments and healthcare institutions. The distrust translates into their decision not to get vaccinated against the deadly COVID-19 virus. Again, they—plus other people of color resident in the USA—have so much cultural and religious beliefs either disallowing vaccination or making them vaccine skeptics. However, refusal to vaccinate among some participants from Ghana is mainly due to lack of access to the vaccines aside cultural and religious beliefs as well as distrusts in government and healthcare institutions. Compared to the global North, Denmark precisely, decision not to vaccinate among some people was principally down to distrust in the vaccines—owing to the swift production period and the conspiracy theories surrounding its efficacies—and not distrust government like we found out from participants from the global South and some from the USA. In the USA, however, skepticism was due to distrust in vaccines (due to history of failed vaccination programs), low trust in healthcare institutions as well as government handling of the pandemic. Some participants believed that there exists vested economic interest in the whole vaccine plan with the pharmaceutical companies profiteering from states. In terms of gender divide, the females believed that they have more to lose taking the vaccine than their male counterparts. Their suggested losses include changes to their menstrual cycles and inability to get or keep pregnancy. Besides, the former vice president of Pfizer Inc. and co-founder of biotech claims that the COVID-19 vaccine could cause infertility among women. Some males were also concerned they might not be fertile if vaccinated.

Conclusion

Indeed, from our primary data, the immigrant status is not the main determinant of the study participants’ trust in government and institutions. In the case of Denmark, study participants’ hesitancy/skepticism towards the approved COVID-19 vaccines is driven predominantly by trust in the vaccines—vaccine protocols, side effects of the vaccine, and history of vaccinations—and not the government and institutions. In terms of trust in governments and institutions, primary data from LS (2021), a female Dane, HH (2021), a male Dane, and AT (2021), a male Nigerian in the USA, could not be conclusive on grounds of immigrant status of the study participants. But rather, respectively, on miscommunication of the institutions to the public, who takes responsibility of possible vaccination fallout, and vested monetary interest of vaccines companies.

The study concludes that a combination of several factors—such as mistrust in the COVID-19 vaccines, distrust in institutions (especially governments and pharmaceutical companies), and deep-rooted cultural and religious beliefs—make people usually skeptical about the vaccination drive. In terms of our all-embracing research question, our primary and secondary data show that distrust in the vaccine protocols, vaccine side effects, and history of vaccinations contribute to vaccine skepticism among some people. Further, mistrust in pharmaceutical companies due to their vested economic interest and historical antecedence of fraud cases; declining trust in government over miscommunication; and mistrust in healthcare authorities influence some to be vaccine skeptics. Finally, entrenched religious and cultural beliefs facilitate some people’s vaccine hesitancy decisions. These conclusions thus answer our research question and problem statement.

Policy Recommendations and Implications

In view of the above issues, we propose the following policy recommendations to realize the 60 to 70% global vaccination agenda.

-

I.

A conscious policy framework should be developed and implemented to waiver the intellectual rights of the vaccine-manufacturing company. This could be achieved through a broader stakeholder consultation involving national governments, vaccine production companies, and WHO. With this policy initiative, vaccine production and utilization would be high towards attaining the global 60 to 70% herd immunity.

-

II.

WHO and international non-governmental organizations should provide more COVID-19 vaccine aids to the global south; this is the feasible path to reach herd immunity globally. This is because the pandemic is a global scourge, and if everyone in the global North is vaccinated but those in the global south are not, the expected herd immunity attainment would be a mirage.

-

III.

The authorities should do more scientific education on the virus to dispel the thriving conspiracy theories on social media. This could be realized by liaising with owners of the various social media platforms—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube—to sanction individuals and institutions who share misinformation about the virus.

-

IV.

Religious leaders should be engaged in dispelling doubts and misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine. This is because they have a foothold of most of their members. If these religious leaders encourage their followers to get vaccinated, the 60 to 70% herd immunity could be attained.

Suggestion for Future Research

Future research should investigate why there is a high success rate in US vaccination despite huge distrust in the pharmaceutical companies, without recourse to our assumptions.

Author Contribution

The first author wrote the introduction and literature review chapter. The second author penned the theoretical and methodological chapter. Both first and second authors scripted the discussion chapter together. Author three reviewed and proofread the entire manuscript. Therefore, all authors contributed equally.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Informed consent was solicited from all the interviewees. The purpose of the study was explained to them before interview was granted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abdul Latif Anas, Email: anasabdullatif@yahoo.com, Email: aanas20@student.aau.dk.

Mashudu Salifu, Email: mash45@hotmail.co.uk, Email: mashudus@ikl.aau.dk.

Hanan Lassen Zakaria, Email: hananlassenzakaria@gmail.com.

References

- Acheampong T, Akorsikumah EA, Osae-Kwapong J, Khalid M, Appiah A, Amuasi JH. Examining Vaccine Hesitancy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of the Knowledge and Attitudes among Adults to Receive COVID-19 Vaccines in Ghana. Vaccines. 2021;9(8):814. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9080814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi AA, Ilesanmi OS. Dealing with vaccine hesitancy in Africa: The prospective COVID-19 vaccine context. Pan African Medical Journal. 2021 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.3.27401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, A. (2021). Some Americans were primed for vaccine skepticism after decades of mistrust in Big Pharma. Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.businessinsider.com/big-pharma-mistrust-contributed-to-vaccine-hesitancy-2021-8?r=US&IR=T

- Alhassan RK, Owusu-Agyei S, Ansah EK, Gyapong M. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among health care workers in Ghana: A case for targeted vaccine deployment campaigns in the global south. Human Resources for Health. 2021;19:136. doi: 10.1186/s12960-021-00657-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschwanden, C. (2021). Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature, 591(7851), 520–522. 10.1038/d41586-021-00728-2. PMID: 33737753. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Belluz, J. (2019). Religion and vaccine refusal are linked. We have to talk about it Retrieved December 17, 2021, from https://www.vox.com/2019/6/19/18681930/religion-vaccine-refusal

- Bryman A. Social Research Methods. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 5. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y-C, Huang YL, Tseng KC, Yen CH, Yang LH. Social Capital and Health-Protective BehaviorIntentions in an Influenza Pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrin J. Comment: The Political Relevance of Trust in Government. American Political Science Review. 1974;68(3):973–988. doi: 10.2307/1959141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Researxh Design, Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Danabal KG, Magesh SS, Saravanan S, Gopichandran V. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India – a community based survey. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21:994. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07037-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duenas, N., & Mangen, C. (2021). Why ensuring trust is important in reducing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Retrieved December 13, 2021, from https://theconversation.com/amp/why-ensuring-trust-is-important-in-reducing-covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-168167

- DW. (2021). COVID-19 Special: Vaccine skepticism drives death toll in Bulgaria. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.dw.com/en/covid-19-special-vaccine-skepticism-drives-death-toll-in-bulgaria/av-59470491

- Eddine NA. The Idealization and Self-Identification of Black Characters in the Bluest Eyes by Toni Morrison: Using Voyant Text Analysis Tools. Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics. 2018;49:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. (2019). How does the world feel about science and health? Wellcome Global Monitor. Retrived December 12, 2021, from https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wellcome-global-monitor-2018.pdf

- Ghanaweb. (2021). Sammy Gyamfi triggers RTI Act on COVID-19 vaccines in Ghana. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://mobile.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Sammy-Gyamfi-triggers-RTI-Act-on-COVID-19-vaccines-in-Ghana-1427119

- Hendrigan, H. (2019). Mixing Digital Humanities and Applied Science Librarianship: Using Voyant Tools to Reveal Word Patterns in Faculty Research. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship. 10.29173/istl3

- Huremović, D. (2019). Brief History of Pandemics (Pandemics Throughout History). In: Huremović, D. (eds) Psychiatry of Pandemics. Springer, Cham. New York City : Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-15346-5

- International Labor Organization. (2021). ILO: Employment impact of the pandemic worse than expected. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_824098/lang--en/index.htm

- International Monetary Fund . World Economic Outlook Recovery During a Pandemic Health Concerns, Supply Disruptions, and Price Pressures. International Monetary Fund, Publication Services; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Rescue Committee. (2021). The only way to stop COVID-19? Vaccines for all. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.rescue.org/article/only-way-stop-covid-19-vaccines-all

- Jacobson RM. Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90(11):1562–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspal R, Nerlich B. Social representations of COVID-19 skeptics: Denigration, demonization, and disenfranchisement. Politics, Groups, and Identities. 2022 doi: 10.1080/21565503.2022.2041443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J., Chen, E., Yan, S., Lerman, K., & Ferrara, E. (2020). Political polarization drives online conversations about COVID-19 in the United States. National Library of Medicine, 2(3): 200–211. 10.1002/hbe2.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keele, L. (2007). Social Capital and the Dynamics of Trust in Government. American Journal of Political Science, 51(2), 241–254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4620063

- LaCour M, Davis T. Vaccine skepticism reflects basic cognitive differences in mortality-related event frequency estimation. Vaccine. 2020;38(21):3790–3799. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H. J., Clarkea, R. M., Jarretta, C., Eckersbergerd, E., Levinea, Z., Schulza, W. S., & Paterson, P. (2018). Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(7): 1599–1609. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Larson HJ, Schulz WS, Tucker JD, Smith DM. Measuring Vaccine Confidence: Introducing a Global Vaccine Confidence Index. Plos Currents. 2015;25(7):1–31. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.ce0f6177bc97332602a8e3fe7d7f7cc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, J. V., Ratzan, S. C., Palayew, A., Gostin, L. O., Larson, H. J., Rabin, K., & El-Mohandes, A. (2020). A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nature Medicine, 27, 225–228. 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lazer, D., Baum, M. A., Ognyanova, K., & Volpe, J. D. (2020). The State Of The Nation: A 50-State Covid-19 Survey, USA, April 2020. Northeastern University, Harvard University, Rutgers University. https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000171-cda6-d7a8-ad7b-ffefc6230000

- Lindholt, M. F., Jørgensen, F., Bor, A., & Petersen, M. B. (2020). Willingness to Use an Approved COVID-19 Vaccine: CrossNational Evidence on Levels and Individual-Level Predictors. Aarhus University, School of Business and Social Sciences. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/6/e048172

- Loomba S, Figueiredo A, d., Piatek, S. J., Graaf, K. d., & Larson, H. J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour. 2021;5:337–348. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, G. (2021). The 6 reasons Americans aren’t getting vaccinated. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https://www.vox.com/2021/6/2/22463223/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-reasons-why

- Leonardo, Z. (2003). Discourse and critique: Outlines of a post-structural theory of ideology. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 203–214. 10.1080/0268093022000043038

- MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.0364161-4164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mach, K. J., Reyes, R. S., Pentz, B., Taylor, J., Costa, C. A., Cruz, S. G., & Klenk, N. (2021). News media coverage of COVID-19 public health and policy information. Humanities And Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–11;2021–12. 10.1057/s41599-021-00900-z

- Mehta, J. (2011). ‘The varied roles of ideas in politics: from “whether” to “how’’ in D. Be ´land and R.H. Cox (eds). Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research, 28–63.

- Morrow, A. M. (2018). Introducing Poststructuralism in International Relations Theory. Retrieved November 27, 2021, from https://www.e-ir.info/2018/02/13/introducing-poststructuralism-in-international-relations-theory/