Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) survivors often report cognitive impairment, which may be influenced by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The purpose of this study was to test whether particular SNPs were associated with changes in cognitive function in BC survivors and whether these polymorphisms moderated cognitive improvement resulting from the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Breast Cancer (MBSR[BC]) program. BC survivors recruited from Moffitt Cancer Center and the University of South Florida’s Breast Health Program, who had completed adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy treatment, were randomized to either the 6-week MBSR(BC) program (n = 37) or usual care (UC; n = 35) group. Measures of cognitive function and demographic and clinical history data were attained at baseline and at 6 and 12 weeks. A total of 10 SNPs from eight genes known to be related to cognitive function were analyzed using blood samples. Results showed that SNPs in four genes (ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 [ANKK1], apolipoprotein E [APOE], methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase [MTHFR], and solute carrier family 6 member 4 [SLC6A4]) were associated with cognitive impairment. Further, rs1800497 in ANKK1 was significantly associated with improvements in cognitive impairment in response to MBSR(BC). These results may help to identify individuals who would be better served by MBSR(BC) or other interventions.

Keywords: genetics, genetic polymorphism, cognitive function, breast cancer, mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR(BC)

Cognitive impairment is a common symptom reported by 65% of breast cancer (BC) patients during chemotherapy treatment and 61% after treatment completion (Wefel, Saleeba, Buzdar, & Meyers, 2010). Studies suggest that BC survivors treated with radiation therapy may demonstrate rates of cognitive impairment similar to those of chemotherapy patients (Donovan et al., 2005; Schagen, Muller, Boogerd, Mellenbergh, & van Dam, 2006). A smaller number (12–35%) of these patients may also have demonstrated cognitive impairment prior to chemotherapy or radiation (Schagen et al., 2006; Wefel et al., 2004). Cognitive impairment after chemotherapy can affect memory and ability to concentrate and can lead to feelings of mental slowness (Von Ah, Habermann, Carpenter, & Schneider, 2013) and difficulties in reading and driving (Myers, 2012), all of which may affect the quality of life and ability to work (Boykoff, Moieni, & Subramanian, 2009). With an estimated projection of 18.1 million cancer survivors in the United States by 2020, the potential effects of cognitive impairment from the disease or its treatment may be a very significant problem (Mariotto, Yabroff, Shao, Feuer, & Brown, 2011).

A critical component of care for cancer patients is determining which patients are at risk for cognitive decline. The emerging practice of personalized medicine utilizes research demonstrating that genetic characteristics can provide insight into individual risk factors. In the case of cancer, evidence from recent studies suggests that particular single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with cognition among survivors (Ahles, 2004; Ahles & Saykin, 2007; Ahles et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2008). Furthermore, particular genes may influence the risk for cognitive impairment among cancer survivors treated with chemotherapy (Ahles & Saykin, 2007; Ahles et al., 2003). Ahles et al. (2003) and Small et al. (2011) investigated the roles of SNPs in apolipoprotein E (APOE) and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT), respectively, in cognitive function among cancer survivors. Both groups of researchers found a significant association between variant alleles and cognitive dysfunction among BC survivors. Based on this research, Ahles et al. suggested that the e4 allele of APOE may be a genetic marker for increased vulnerability to chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment, while Small et al. suggested that survivors who possess the COMT Val allele and are treated with chemotherapy are susceptible to negative cognitive effects. While these and other studies have demonstrated that genetic characteristics have the potential to provide insight into individual risk factors, there remains limited evidence about the use of genetic information in making treatment decisions, another goal of personalized medicine (Andrykowski, Burris, Walsh, Small, & Jacobsen, 2010; Guttmacher & Collins, 2002).

Although cognitive impairment is a major problem for BC survivors, there remains a lack of effective pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions to enhance cognitive functioning in this population. Methodological limitations of reported studies and side effects of the available agents have limited the effective use of pharmacotherapy to improve cognitive impairment in BC survivors (Joly, Rigal, Noal, & Giffard, 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Pinto & de Azambuja, 2011). Two nonpharmacological interventions that have shown some promise in improving cognition include yoga (Culos-Reed, Carlson, Daroux, & Hately-Aldous, 2006; Vadiraja et al., 2009) and memory and attention adaptation training (MAAT), a brief cognitive–behavioral therapy program (Ferguson et al., 2007, 2012). Study results among BC patients participating in a yoga program revealed significant improvement in cognitive function (Culos-Reed et al., 2006; Vadiraja et al., 2009). Among 29 BC patients who received the MAAT intervention in a nonrandomized trial, researchers observed improvements in subjective cognitive functioning and neuropsychological test results (Ferguson et al., 2007, 2012).

Mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer survivors (MBSR[BC]) is another promising nonpharmacological approach to targeting cognitive impairment. The program is based on the recognition that cognitive impairment is a functional problem that may be related to the mind–body interactions of stress, rumination, focused attention, distraction, and activation of the neural systems that regulate attention (Lutz, Brefczynski-Lewis, Johnstone, & Davidson, 2008). MBSR(BC) has the potential to influence cognitive impairment through the use of formal and informal mindfulness meditation practices and the process of self-regulation of attention (Biegler, Chaoul, & Cohen, 2009; Gawler & Bedson, 2010). In a review of 23 studies using mindfulness meditation practices primarily among healthy volunteers, the authors found that the practice was associated with significant improvements in working memory, sustained attention, and decreased rumination (Chambers, Lo, & Allen, 2008). To our knowledge, however, no previous study has examined the benefits of MBSR for cognitive improvement among BC survivors after treatment.

The purpose of the present study was twofold (1) to test whether there are SNPs associated with changes in cognitive function in BC survivors and (2) to explore whether there are SNPs that moderate improvements in cognitive impairment in BC survivors from MBSR(BC). Our long-term goal is to use the information gained in this exploratory study to guide the choice of candidate genes for future large validation studies of genes and cognitive impairment in BC survivors.

Material and Method

Participants

We recruited a subsample of BCsurvivors (N = 72) from within a larger R01 MBSR(BC) trial from the Moffitt Cancer Center and the University of South Florida Carol and Frank Morsani Center for Advanced Healthcare, both located in Tampa, FL. Inclusion criteria for the parent study as well as this genetic substudy were (1) women aged 21 years or older with (2) a diagnosis of Stage 0–III BC and (3) proficiency in English at the eighth-grade level who had (4) surgical treatment (lumpectomy and/or mastectomy) and (5) had completed adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy within 2 weeks to 2 years prior to study enrollment. Exclusion criteria included a previous diagnosis of BC, Stage IV cancer, and/or a severe psychiatric disorder.

Procedures

Study design and randomization.

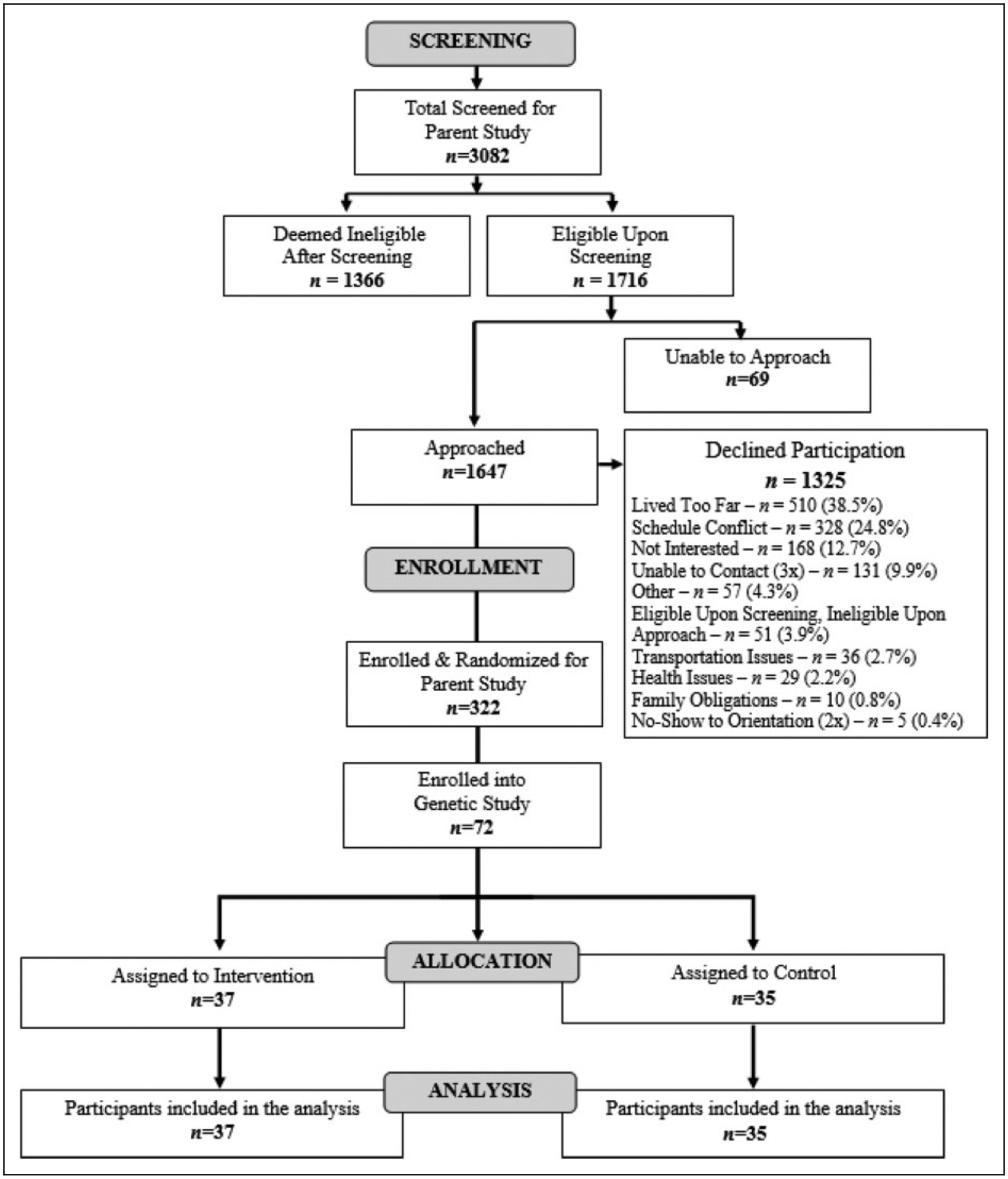

A two-armed randomized controlled design was used among the subsample of 72 BC survivors (Figure 1). Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the 6-week MBSR(BC) program or the usual care (UC). BC survivors assigned to UC were offered the opportunity to receive the MBSR(BC) program within 6 months of study enrollment. Participants were randomized by type of surgery (lumpectomy vs. mastectomy), BC treatment (chemotherapy with or without radiation vs. radiation alone), and clinical stage of BC (Stages 0–I vs. II–III). Informed consents were obtained prior to study enrollment. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) for the University of South Florida and Scientific Review Committee for Moffitt Cancer Center approved the study protocol (IRB#107408).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of participant recruitment, screening, and enrollment from parent R01 trial to study subset.

Recruitment and data collection procedures.

Clinic nurses identified eligible BC survivors, whom the study recruiter subsequently approached. Women who expressed an interest in the MBSR(BC) program were invited to attend an orientation session. At this session, study personnel collected baseline data from patients who consented to participate, which included a blood sample, demographic and clinical history, and assessment of cognitive impairment using the Everyday Cognition (ECog) questionnaire. This questionnaire was added later in the parent trial, thus, ECog data were only available for the subsample of women who participated in the present study. Demographic and clinical history data were updated after the 6-week intervention period and at 12 weeks of follow-up. Cognitive impairment was assessed again at 6 and 12 weeks with the ECog questionnaire.

MBSR(BC) intervention.

The MBSR(BC) intervention was modeled after the MBSR program of Jon Kabat-Zinn and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Stress Reduction and Relaxation Clinic (Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth, & Burney, 1985; Kabat-Zinn et al., 1992). The MBSR(BC) program was adapted to assist BC survivors in taking an active role in stress reduction and symptom management through the self-regulatory process of meditation. The intervention consisted of (1) educational material related to meditation, the mind–body connection, and a healthy lifestyle for survivors; (2) practice of meditation in group meetings and homework assignments; and (3) group processes related to barriers to the practice of meditation, application of mindfulness in daily situations, and supportive group interaction (Speca, Carlson, Goodey, & Angen, 2000). Participants received 6 weekly 2-hr sessions conducted by a trained psychologist in four techniques: (1) sitting meditation (an awareness of bodily sensations, thoughts, and emotions while focusing on attention to breathing); (2) body scan (observing any sensations in the body from head to toe while focusing attention to breathing); (3) gentle hatha yoga (various postures and stretching thought to increase awareness and balance); and (4) walking meditation (increased awareness during walking; Kabat-Zinn et al., 1992). We requested that BC survivors formally meditate (mindfulness practice including yoga and body scan exercises) for a minimum of 15–45 min/day and allocate 15–45 min for informal practice. We provided participants with CDs for guided meditations, and they used a daily diary to record meditative practices.

UC.

The UC regimen consisted of standard posttreatment clinic visits. We asked participants randomized to UC to refrain from practicing meditation, yoga, or MBSR for the duration of the study period.

Measures

Demographics and clinical history.

We collected demographic data on age; ethnicity; highest level of education completed; and marital, income, and employment status at baseline. Participants had the opportunity to update these data at 6 and 12 weeks. In addition, we collected clinical medical history including data related to cancer diagnosis and treatment at baseline, 6, and 12 weeks to determine if there were any new problems of clinical significance.

Cognition.

The ECog multidimensional instrument is a 40-item self-report questionnaire that measures impairment and change in everyday, real-world functioning relevant to seven neuropsychological domains, namely, everyday memory, everyday language, everyday semantic knowledge, everyday visuoperceptual skills, everyday planning, everyday organization, and everyday divided attention (Farias et al., 2008). Respondents are asked to compare their present level of everyday functioning to that of 10 years earlier on a 4-point scale (1 = better or no change compared to 10 years earlier, 4 = consistently much worse). There are scores for each of the 7 subscales as well as a total global score for the instrument. Overall, internal consistency reliability is .82 (Farias et al., 2008). Data suggest that self-reported cognitive problems may be more sensitive to treatment-related changes in BC survivors than neuropsychological testing (Ganz et al., 2013).

Gene and SNP selection.

Using PubMed, we searched for candidate genes and SNPs to represent polymorphisms of the dopamine and serotonin pathways that have been associated with cognitive function. We then narrowed the search to include only genes associated with cognitive function. We considered several types of gene products such as receptors, transporters, and metabolic enzymes. Selected genes examined in these pathways include dopamine receptor 2 (DRD2), COMT, ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (ANKK1), APOE, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), serotonin receptor 2A (5HT2A), solute carrier family 6 member 4 (SLC6A4), and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR).

Once we established candidate genes, we selected SNPs based on their associations with cognitive function in previous research or known biological impacts on gene transcription or protein activity (Chen et al., 2004; Fisher et al., 2015; Gong et al., 2011; Hirvonen et al., 2004; Martin, Cleak, Willis-Owen, Flint, & Shifman, 2007; Ni et al., 2006; Polesskaya & Sokolov, 2002; Ponce et al., 2009; Prada et al., 2014; Swagell et al., 2012; Ueland, Hustad, Schneede, Refsum, & Vollset, 2001; Wagner, Schuhmacher, Schwab, Zobel, & Maier, 2008). Based on these inclusion criteria, we selected 10 SNPs in eight genes: rs1800497 in ANKK1; rs429358 in APOE; rs6265 in BDNF; rs4680 in COMT; rs6277 in DRD2; rs6313, rs6314, and rs4941573 in HTR2A; rs1801133 in MTHFR; and rs16965628 in SLC6A4.

Genotyping.

We drew 5 ml of blood for genotyping. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the Qiagen DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with modifications. We then used a TaqMan allele discrimination polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for genotyping, as described in previous studies (Jim et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2012).

Statistical Methods

We used a two-step approach to determine whether an SNP moderated the effects of the MBSR(BC) program on cognitive outcomes. First, to identify which of the 10 candidate SNPs were significantly associated with cognitive impairment outcomes, we used Spearman correlations. Next, we tested the influence of MBSR(BC), genotype, and their interactions on each of the seven ECog subscales and total score in a general linear model using a 2 (MBSR(BC) condition) × 2 (presence vs. absence of the variant allele) factorial analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Because the amount of time since the end of cancer treatment (i.e., chemotherapy and/or radiation) may be related to study outcomes, we included time since treatment as a covariate in each ANCOVA. A statistically significant interaction between MBSR(BC) and an SNP would indicate that the relationship between MBSR(BC) and cognitive impairment varied as a function of that SNP. We used nonparametric approaches in the first two steps because of nonnormality in the ECog data. To reduce bias resulting from the nonnormal data in the factorial ANOVAs, we log-transformed ECog data. Due to the ethnic diversity of the study population, we examined minor-allele frequency and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium separately for Caucasians, African Americans, or combined, based on self-identified ethnicity. We tested Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using chi-square analyses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The demographic and treatment characteristics for the participants in the case and control groups are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 58 years, with 77% identifying themselves as Caucasian, 11% as African American, and 12% as Hispanic. The majority of participants had Stage II disease (n = 28), with 65% treated with radiation, 43% treated with chemotherapy, and 33% treated with both chemotherapy and radiation. There were no significant differences in age, clinical stage, type of cancer treatment, or time since treatment between the MBSR(BC) (n = 37) and UC (n = 35) groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants.

| Characteristic | UC, n = 35 | MBSR(BC), n = 37 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M ± SD | 57 ± 8.74 | 59 ± 10.90 | .42 |

| Race, n (%) | .27 | ||

| White/non-Hispanic | 28 (80) | 28 (76) | |

| White/Hispanic | 3 (9) | 3 (8) | |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 2 (6) | 6 (16) | |

| Black/Hispanic | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 2 (6) | 0 | |

| Disease stage, n (%) | .80 | ||

| 0 | 3 (9) | 6 (16) | |

| I | 14 (40) | 14 (38) | |

| II | 11 (31) | 11 (30) | |

| III | 7 (20) | 6 (16) | |

| Surgery type, n (%) | .34 | ||

| Lumpectomy | 15 (43) | 20 (54) | |

| Mastectomy | 20 (57) | 17 (46) | |

| Adjuvant treatment, n (%) | .23 | ||

| Chemo | 6 (17) | 1 (3) | |

| Radiation | 10 (29) | 13 (35) | |

| Chemo and radiation | 11 (31) | 13 (35) | |

| No chemo or radiation | 8 (23) | 10 (27) | |

| Time since cancer treatment (days), M ± SD | 200 ± 149 | 218 ± 193 | .67 |

Note. MBSR(BC) = mindfulness-based stress reduction program for breast cancer survivor group; UC = usual care group.

Baseline Cognitive Function

At baseline, the MBSR(BC) and UC groups did not differ significantly on seven of eight ECog scales. For the Divided Attention subscale, however, MBSR(BC) participants had a slightly higher mean baseline score compared to the UC group (1.68 vs. 1.40, respectively, p < .05). To minimize the influence of variability in baseline scores on all scales, we used difference scores between baseline and 12 weeks to make comparisons between the groups.

Associations Between Genotype and Cognitive Outcomes

Before beginning analysis of the associations of the SNPs with cognitive outcomes, we first examined whether there were racial differences in allele or genotype frequency. The genotype distributions of all SNPs were consistent with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (Table 2). As expected, we observed racial differences in allele frequencies in most SNPs. Among Caucasians, both minor allele frequency and genotype distribution of each SNP were similar to those listed in the public database available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, 2014).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Candidate SNPs.

| Gene Symbol | SNP ID | Chr/Orientation | Allele (P/W) | Change | MAF | Poly/HT/WT | HWE | Function | ECog Subscale Associated With SNP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 37) | Controls (n = 35) | |||||||||

| ANKK1 | rs1800497 | 11/Rev | A/G | Glu713Lys | 0.22 | 02/17/17 | 01/08/26 | 0.98 | Structural change in binding site (Ponce et al., 2009) | Planning |

| APOE | rs429358 | 2/Rev | G/A | Cys156Arg | 0.15 | 01/11/25 | 00/09/26 | 0.89 | Associated with cognitive function (Prada et al., 2014) | Visuospatial |

| BDNF | rs6265 | 11/For | A/G | Val66Met | 0.16 | 01/10/25 | 02/06/25 | 0.77 | Affects brain serotonin levels (Fisher et al., 2015) | – |

| COMT | rs4680 | 22/For | A/G | Val158Met | 0.45 | 07/20/10 | 05/21/09 | 0.67 | Affects BDNF activity fourfold (Chen et al., 2004) | – |

| DRD2 | rs6277 | 11/Rev | G/A | Pro319Pro | 0.48 | 08/17/11 | 08/20/07 | 0.96 | Associated with a lower striatal DRD2-binding potential than the T-allele (Hirvonen et al., 2004) and alcohol dependence (Swagell et al., 2012) | – |

| HTR2A | rs6313 | 13/Rev | A/G | Intron | 0.43 | 08/11/13 | 08/11/12 | 0.27 | Associated with the increased expression of HTR2A (Polesskaya & Sokolov, 2002). | – |

| HTR2A | rs6314 | 13/Rev | A/G | His452Asn | 0.06 | 00/05/32 | 00/04/31 | 0.86 | Associated with slower calcium mobilization, which causes a blunted response to serotonin stimulation (Wagner, Schuhmacher, Schwab, Zobel, & Maier, 2008). | – |

| HTR2A | rs4941573 | 13/For | G/A | Intron | 0.43 | 09/12/13 | 06/11/12 | 0.89 | Associated with personality traits, a higher extraversion score (Ni et al., 2006) and visuospatial working memory (Gong et al., 2011) | – |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | 1/Rev | A/G | Ala222Asp | 0.34 | 01/16/20 | 08/15/12 | 0.97 | Change in enzyme activity (Ueland, Hustad, Schneede, Refsum, & Vollset, 2001) | Visuospatial, Planning, Satisfaction |

| SLC6A4 | rs16965628 | 17/For | C/G | Intron | 0.08 | 03/05/28 | 00/01/34 | 0.19 | Associated with increased transcription (Martin, Cleak, Willis-Owen, Flint, & Shifman, 2007) | Memory, Organization, Global Cognition |

Note. Allele (P/W) = polymorphic/wild; Chr = chromosome; ECog = Everyday Cognition questionnaire; For = forward; HWE = Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; MAF = minor allelic frequency; Poly/HT/WT = homozygous polymorphic/heterozygous/wild; Rev = reverse; SNPs = single-nucleotide polymorphisms; DRD2 = dopamine receptor 2; ANKK1 = ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1; BDNF = brain-derived neurotrophic factor; 5HT2A = serotonin receptor 2A; SLC6A4 = solute carrier family 6 member 4, MTHFR = methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; APOE = apolipoprotein E; COMT = catechol-o-methyltransferase. A hyphen in the last column indicates that there was no association between that SNP and an ECog subscale score.

We implemented Spearman correlations to determine whether the SNPs were associated with change in cognitive function from baseline to 12 weeks among all participants (N = 72) and found four SNPs with a significant association (p < .05; see Table 3): (1) BC survivors with at least one polymorphic allele (AG or GG) of rs1800497 in ANKK1 experienced greater improvement in two ECog outcomes (Planning and Global Cognition) compared to BC survivors with wild type (GG); (2) BC survivors with wild type (AA) of rs429358 in APOE showed greater improvement in Visuospatial Cognition compared to carriers (AG or GG); (3) BC survivors with wild type (GG) of rs1801133 in MTHFR experienced greater improvement in three ECog outcomes (Visuospatial, Planning, and Satisfaction) compared to carriers (AG or AA); and (4BC survivors with the wild type (GG) of rs16965628 in SLC6A4 had greater improvement in three ECog outcomes (Memory, Organization, and Global Cognition) compared to those with at least one polymorphic allele (GC or CC). To rule out the possibility that genotype was confounded with type of cancer treatment (leading to spurious relationships), we used chi-square tests to determine whether proportions of participants receiving chemotherapy, radiation, or both were different by genotype for each of these four genes and observed no differences.

Table 3.

Spearman Correlations Between SNPs and ECog Scores.

| Gene Symbol | Memory | Language | Visuospatial | Planning | Organization | Divided Attention | Global Cognition | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKK1 | .10 | .15 | .09 | .26* | .19 | .13 | .25* | .02 |

| APOE | −.16 | −.16 | −.35** | −.01 | −.12 | −.14 | −.14 | −.22 |

| BDNF | −.03 | .02 | .19 | .16 | .08 | .02 | .14 | −.01 |

| COMT | .08 | .02 | −.01 | .03 | .08 | .02 | .02 | .06 |

| DRD2 | .12 | .02 | .03 | .01 | .13 | −.05 | .08 | .13 |

| HTR2A | .11 | .03 | .06 | .03 | .22 | .06 | .13 | −.01 |

| HTR2A | −.19 | −.21 | −.01 | −.11 | −.16 | −.15 | −.17 | .03 |

| HTR2A | .02 | .07 | .01 | .09 | −.13 | .08 | .01 | .10 |

| MTHFR | −.11 | −.23 | −.42** | −.25* | −.19 | −.22 | −.23 | −.26* |

| SLC6A4 | .40** | .22 | .23 | .17 | .44** | .14 | .42** | −.04 |

Note. DRD2 = dopamine receptor 2; ANKK1 = ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1; BDNF = brain-derived neurotrophic factor; 5HT2A = serotonin receptor 2A; SLC6A4 = solute carrier family 6 member 4, MTHFR = methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; APOE = apolipoprotein E; COMT = catechol-o-methyltransferase; ECog = everyday cognition; SNPs = single-nucleotide polymorphisms. These correlations represent the entire sample (N = 72). Positive correlations indicate that polymorphic allele carriers were more likely to improve between baseline and Week 12 of the study. Negative correlations indicate that wild-type carriers were more likely to improve.

p < .05.

p < .01.

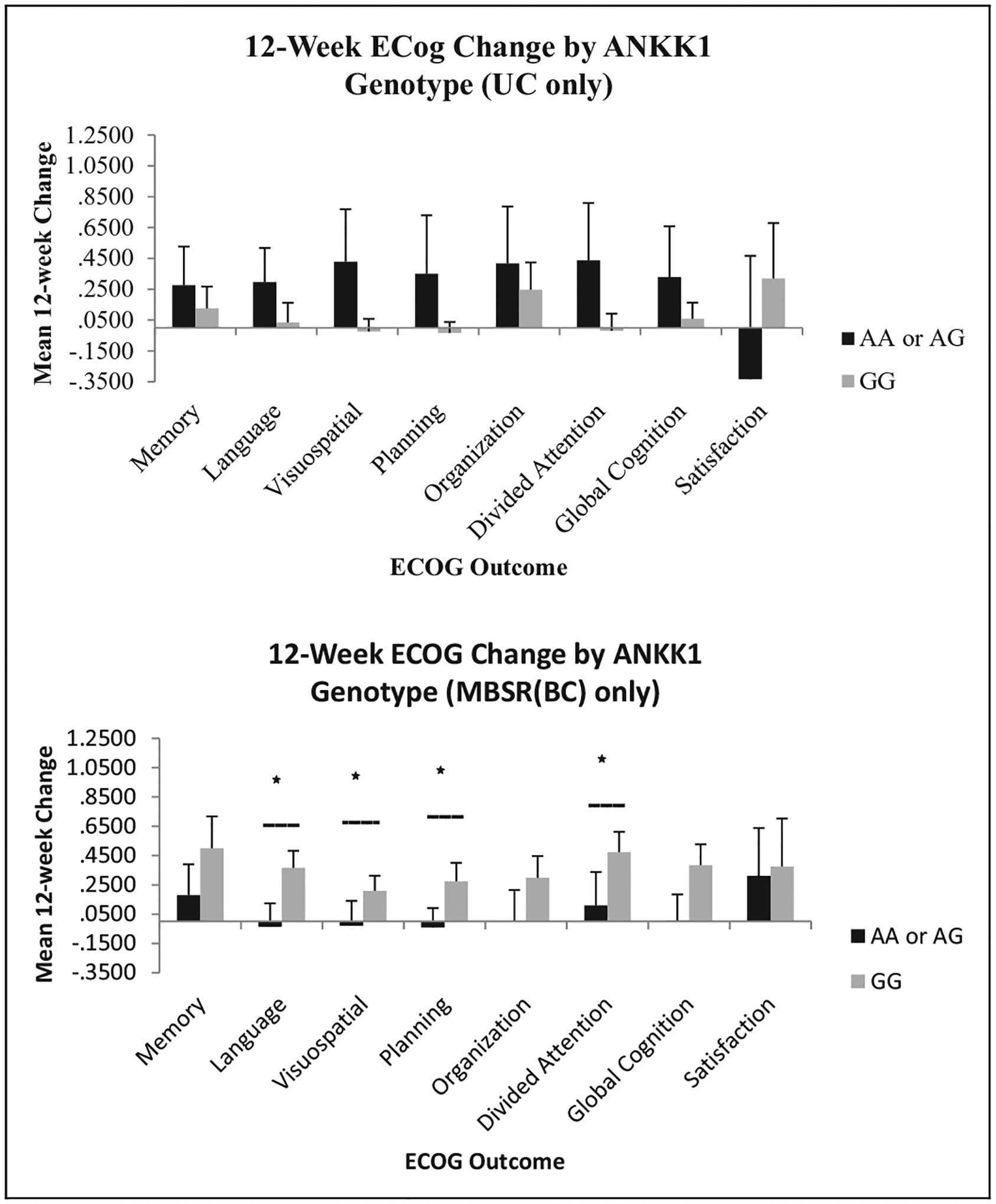

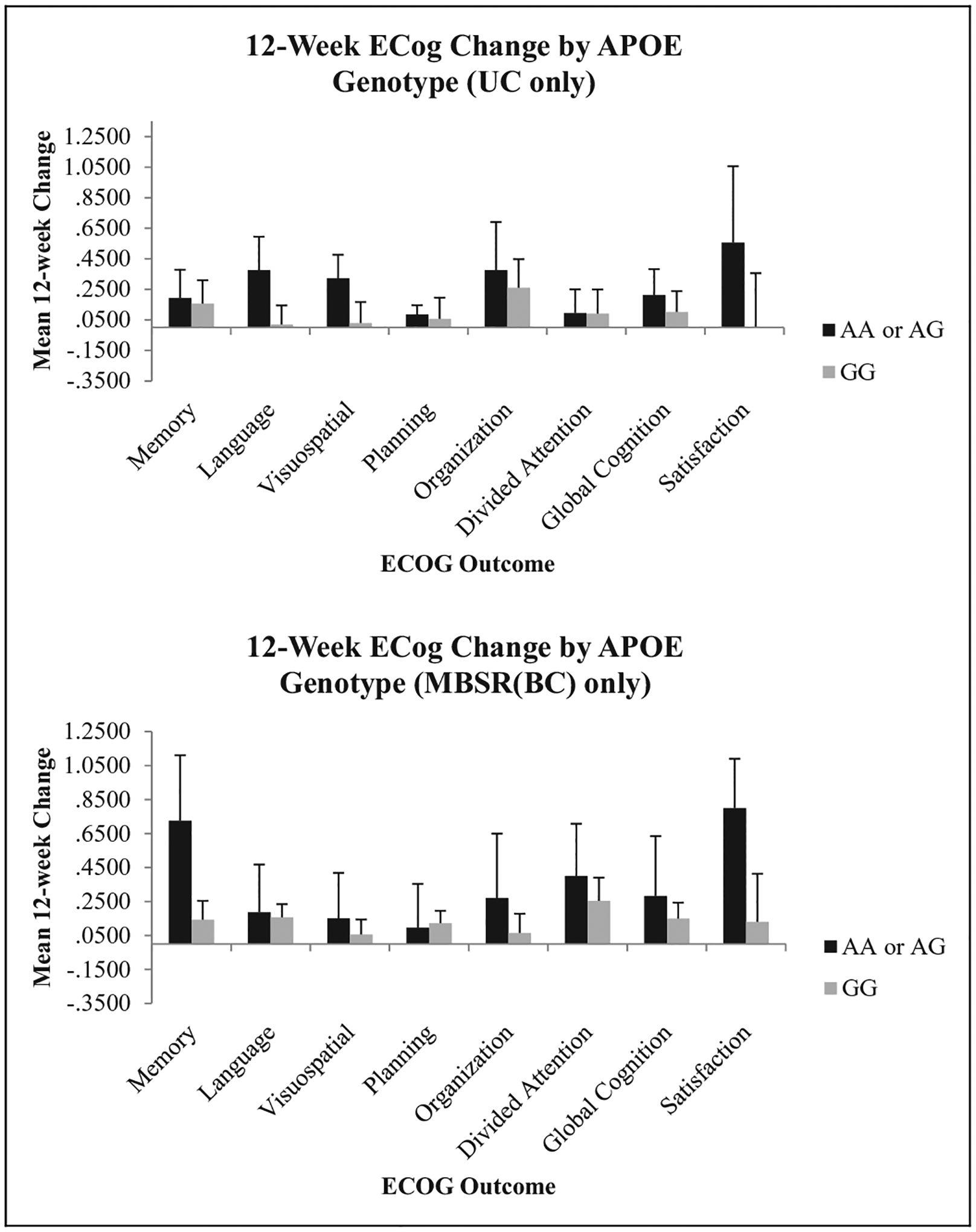

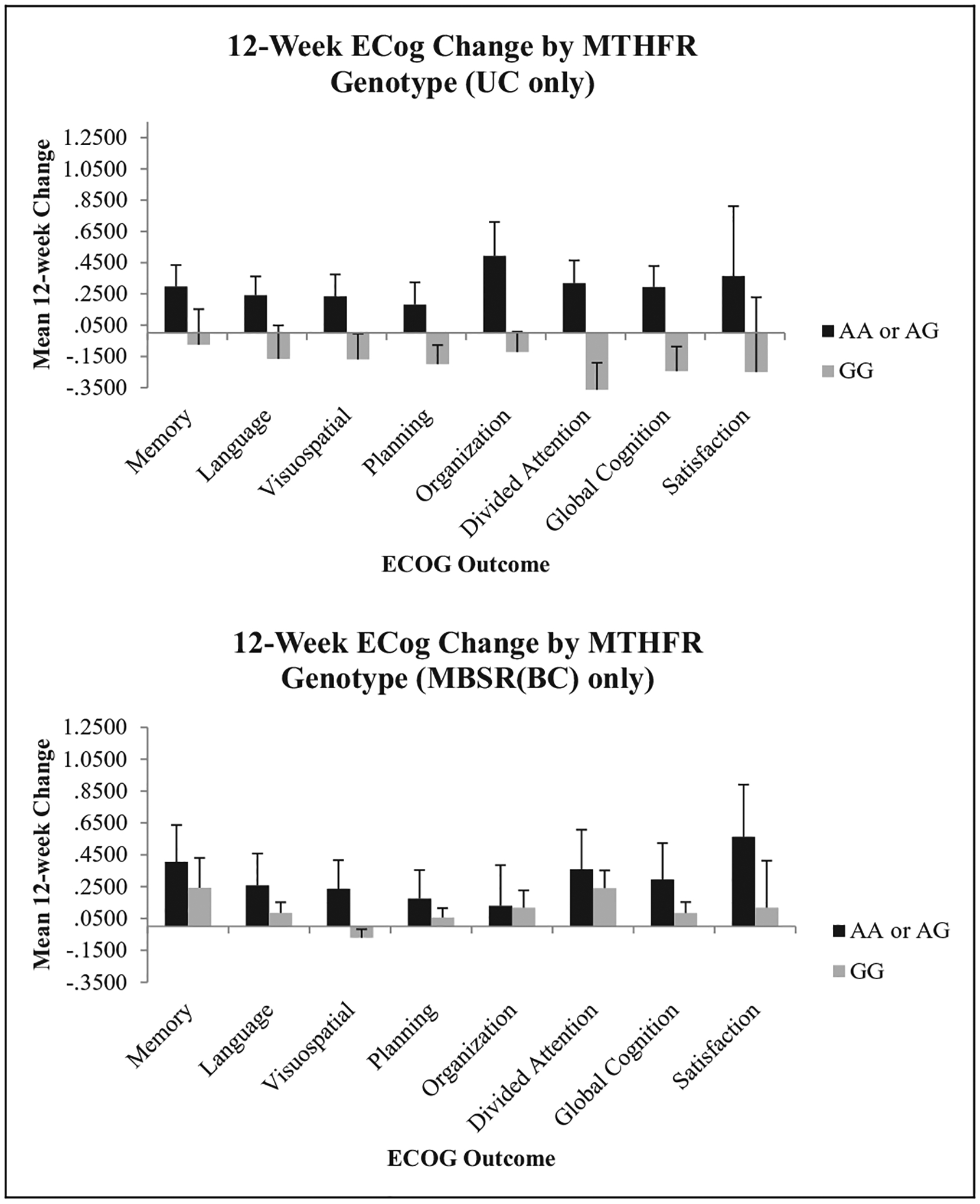

MBSR(BC) by Genotype Interactions

We performed ANOVAs to investigate whether the four SNPs that were significantly associated with changes in cognitive symptoms from baseline to 12 weeks moderated any relationships between the MBSR(BC) intervention and the cognitive changes. The four identified gene variants were included in a series of 2 (condition) × 2 (wild type vs. heterozygous or polymorphic homozygous) factorial ANOVAs. The SNP rs1800497 in ANKK1 emerged as a significant moderator of the effect of MBSR(BC) on cognitive outcomes. With this SNP, four of the eight ECog outcomes demonstrated a significant interaction between MBSR(BC) and genotype, namely, Language, F(1, 60) = 4.41, p = .04; Visuospatial, F(1, 60) = 4.83, p = .03; Planning, F(1, 60) = 5.38, p = .02; and Divided Attention, F(1, 60) = 4.48, p = .04. We further observed a trend for an effect with Global Cognition, F(1,60) = 3.29, p = .08. All outcomes were in the same direction, with women having the wild type (GG) getting more benefit from MBSR(BC) than carriers (AA or AG) of rs1800497. Changes in ECog scores as a function of ANKK1, APOE, MTHFR, and SLC6A4 genotypes are presented in Figures 2–5 and separated by experimental condition (MBSR[BC] vs. UC). Although other single ECog scales demonstrated significant interactions between MBSR(BC) and other tested genes, only ANKK1 demonstrated multiple statistically significant effects. It is important to note, however, that SLC6A4 demonstrated numerous within-MBSR(BC) effects, but the interaction between genotype and experimental condition was impossible to test because of the rarity of the non-wild-type genotype. In the UC condition, there was only one participant who was heterozygous. The remaining participants were homozygous wild type.

Figure 2.

Change in Everyday Cognition (ECog) scores by ANKK1 genotype. ANCOVA was used to compare Condition × Genotype interactions using time since treatment as a covariate. MBSR(BC) = mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer survivor group; UC = usual care group; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; ANKK1 = ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1. *Statistically significant interaction between genotype and MBSR(BC) condition, p < .05.

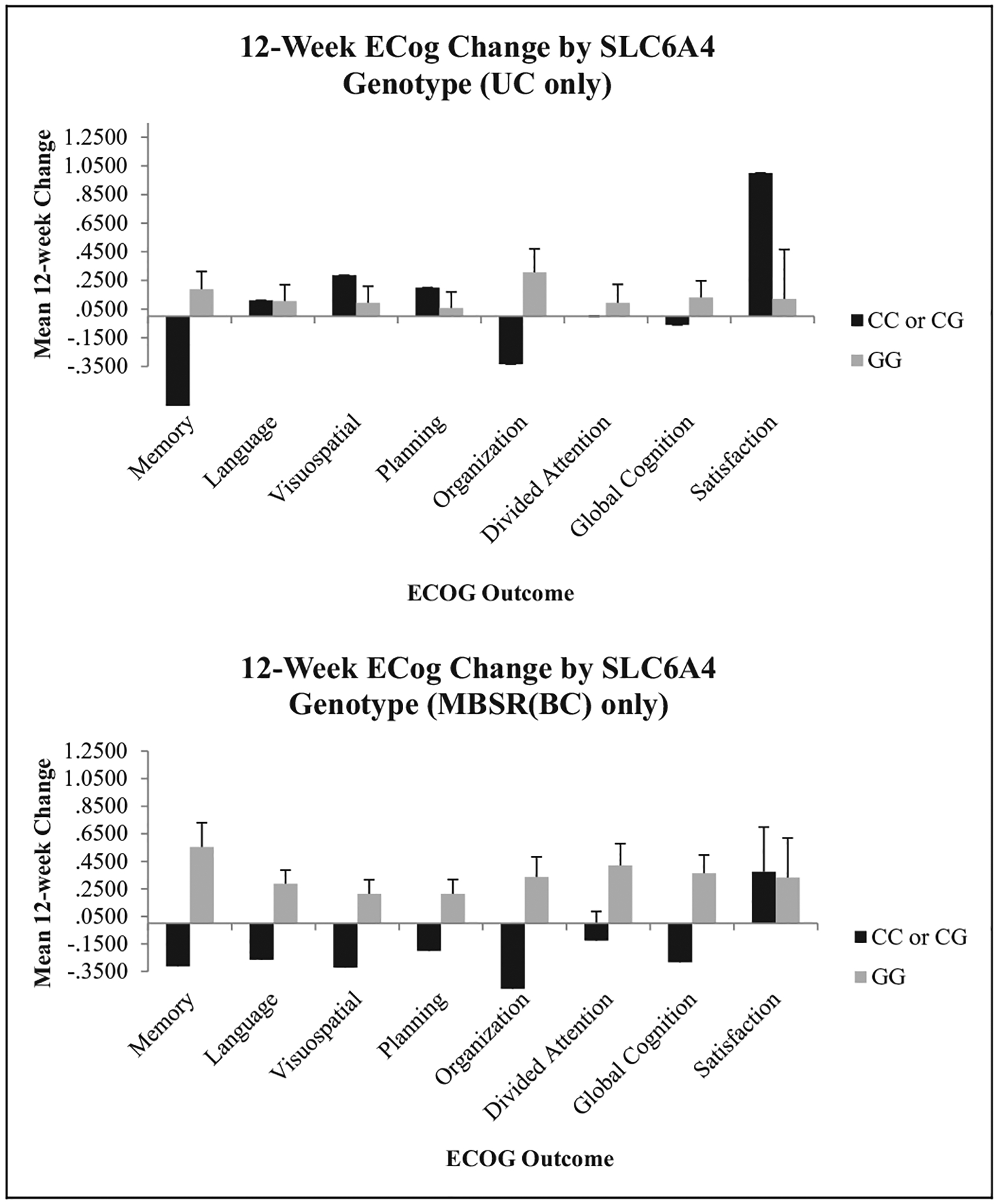

Figure 5.

Change in Everyday Cognition (ECog) scores by SLC6A4 genotype. ANCOVA was used to compare Condition × Genotype interactions using time since treatment as a covariate. No statistically significant interactions were observed for this gene. MBSR(BC) = mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer survivor group; UC = usual care group; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; SLC6A4 = solute carrier family 6 member 4.

To determine whether different genotype distributions by ethnicity or race affected outcomes, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using only White, non-Hispanic participants (the only group large enough in which to complete such an analysis). Results from this analysis did not differ appreciably from the results for the entire sample.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to test whether SNPs were associated with changes in cognitive functioning in BC survivors and whether these identified SNPs moderated the relationship between the MBSR(BC) intervention and self-reported changes in cognitive function. Although the exact mechanisms for chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment are largely unknown, genetic factors play a role (Ahles & Saykin, 2007; Malhotra et al., 2002; Pang & Lu, 2004; Pezawas et al., 2004).

The present study had two important and relevant key findings. First, among the 10 SNPs from the eight genes involved in dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways that we evaluated, we observed that SNPs in four genes were associated with cognitive impairment (ANKK1, APOE, MTHFR, and SLC6A4). BC survivors with carrier (GA or AA) of rs1800497 in ANKK1 experienced greater improvement in Planning and Global Cognition than BC survivors with wild type (GG). rs1800497, a nonsynonymous SNP formerly known as the A1 allele of DRD2 TaqIa because of its proximity and overlapping functionality (Neville, Johnstone, & Walton, 2004), causes an amino acid change from Glu to Lys at codon 713 (Ponce et al., 2009). The biological functions of this SNP are reduced D2 dopamine receptor binding and glucose metabolism in the brain (Ponce et al., 2009). Phenotypes induced by rs1800497 are related to various cognitive functions, and our finding of an association between this SNP and changes in cognitive function is supported by previous studies (Berryhill, Wiener, Stephens, Lohoff, & Coslett, 2013; Noble, 2000; Savitz et al., 2013; Spellicy et al., 2014). Researchers have reported rs1800497 as a risk factor for alcohol dependence and heroin abuse (Blum et al., 1990; Hou & Li, 2009). Several studies have indicated that rs1800497 is consistently associated with addiction to cocaine, nicotine, and gambling (Noble, 2000; Spellicy et al., 2014) and with depression (Savitz et al., 2013). Berryhill, Wiener, Stephens, Lohoff, and Coslett (2013) reported that visual working memory reaction times were slower and more variable among SNP carriers (AA or AG) when compared to individuals with wild type (GG).

Our results also showed that BC survivors with wild type (AA) of rs429358 in APOE had greater improvement in Visuospatial Cognition than BC survivors carrying GA or GG genotypes. APOE is highly expressed in the brain and neurons, although its exact biological roles have not been completely established (Elliott, Kim, Jans, & Garner, 2007). The gene plays a major role in pathways involved in cognitive function, lipid and cholesterol transport, neuron repair and maintenance, and anti-inflammatory activities (Lahiri, Sambamurti, & Bennett, 2004; Li et al., 2014). The APOE-ε2/3/4 alleles, determined by rs7412 and rs429358, are arguably the most investigated SNPs for susceptibility to brain diseases and cognitive impairment (Morley & Montgomery, 2001; Schiepers et al., 2012). Ahles et al. (2003) found the e4 allele of APOE to be a genetic marker for increased vulnerability to chemotherapy-induced side effects as well as to a decline in cognitive function related to visual memory and spatial ability. Xin, Ding, and Chen (2010) reported in a meta-analysis that studies have shown rs429358 to be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and to be associated, more generally, with cognitive function. Our results in the present study suggest that rs429358 may be inversely related to improvement in cognitive impairment in response to the MBSR(BC) intervention.

Our participants with wild type (GG) of rs1801133 in MTHFR experienced greater improvement in three ECog outcomes (Visuospatial, Planning, and Satisfaction) than carriers (AG and AA). A nonsynonymous SNP, rs1801133 in MTHFR, has been associated with cognitive function (Elkins et al., 2007) and has been shown to affect enzyme activity (Ueland et al., 2001). Additionally, MTHFR is involved in folate metabolism, which affects dopamine levels (Fava & Mischoulon, 2009). Researchers have reported inconsistent results regarding an association between rs1801133 and risk for depression (Wang et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2013).

We also found that the wild type (GG) of rs16965628 in SLC6A4 was significantly associated with greater improvement in three ECog outcomes than carriers (GC or CC), namely, Memory, Organization, and Global Cognition. A large number of studies have examined associations between SLC6A4 polymorphisms and susceptibility to depression, anxiety disorders, and cognitive impairment (Lipsky, Hu, & Goldman, 2009; Munafo, Clark, & Flint, 2005). Martin, Cleak, Willis-Owen, Flint, and Shifman (2007) tested the potential impact of transcription on 55 SNPs distributed in a 100-kb window surrounding SLC6A4. They found the most significant SNP to be rs16965628, which affects expression of SLC6A4.

Our second key finding is that rs1800497 in ANKK1 was a significant moderator of improvement in cognitive impairment in response to the MBSR(BC) intervention. In addition, ECOG improvement for MBSR(BC) patients who were AG or GG carriers exceeded 0.50 SD on three of eight scales. This effect size is considered the benchmark for clinical effectiveness. These results provide the first evidence that improvement in cognitive impairment from an MBSR(BC) intervention among BC survivors may be affected by the participants’ specific genotype. Such findings increase the potential for a targeted pharmacogenomics approach to the prevention and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, our findings could be used to develop a genetic screening protocol to determine which BC patients might benefit more from participation in an MBSR(BC) intervention designed to improve psychological and physical symptoms and quality of life among survivors.

Our results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our sample was small and included women who did not exclusively receive chemotherapy, which may be of great importance regarding cognitive impairment. However, our findings on significant associations between SNPs in candidate genes and treatment-related cognitive impairment among BC were consistent with those reported by Ahles et al. (2003) and Small et al. (2011). Our sample size did not permit examination of potential moderators such as genotype distribution, race, and cancer treatment regimens or for correction for multiple comparisons (10 genes × 8 ECog scores). This study was exploratory in nature with the goal of identifying genes to be studied among future larger samples.

The second limitation is the diversity of the study population, particularly since the impact of SNPs may vary among different populations. For example, the APOE ε4 allele has been identified as a significant risk allele of Alzheimer’s disease in Caucasians. However, a similar association between APOE genotype and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans was not observed (Tang et al., 1998).

Finally, we did not perform an assessment of cognitive functioning prior to a BC diagnosis and/or treatment and thus could not determine whether there had been cognitive deficits prior to treatment. In the same vein, we did not include a healthy (non-cancer) control group. As a result, we cannot make inferences about the relationship between these genes and cognitive impairment in the general population. Future research may help clarify the role of a participant’s genetic profile in enhancing the efficacy of the MBSR(BC) intervention and reduce the chance of false positive findings.

This study provides preliminary evidence that variants in four genes (ANKK1, APOE, MTHFR and SLC6A4) are associated with improvement in cognitive functioning in BC survivors after treatment. In addition, our findings provide evidence that an SNP from ANKK1 involved with dopaminergic pathways modulates improvement in cognitive function in response to an MBSR(BC) intervention. Future research should continue to define both who is at risk for cognitive decline and whether the genetic profiles of BC survivors affect the impact of specific interventions such as MBSR(BC) and other behavioral therapies. These data may then be used to develop personalized treatment programs tailored to the genetic characteristics of each patient, particularly for those who are at risk for cognitive decline, and integrated into survivorship care plans for cancer survivors, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor (Committee on Cancer Survivorship, 2005).

Figure 3.

Change in Everyday Cognition (ECog) scores by APOE genotype. ANCOVA was used to compare Condition × Genotype interactions using time since treatment as a covariate. No statistically significant interactions were observed for this gene. MBSR(BC) = mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer survivor group; UC = usual care group; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; APOE = apolipoprotein E.

Figure 4.

Change in Everyday Cognition (ECog) scores by MTHFR genotype. ANCOVA was used to compare Condition × Genotype interactions using time since treatment as a covariate. No statistically significant interactions were observed for this gene. MBSR(BC) = mindfulness-based stress reduction for breast cancer survivor group; UC = usual care group; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; MTHFR = methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported in part by a grant from the University of South Florida’s Established Researcher Award and in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA131080-01A2).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahles TA (2004). Do systemic cancer treatments affect cognitive function? Lancet Oncology, 5, 270–271. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01463-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, & Saykin AJ (2007). Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nature Reviews Cancer, 7, 192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, Li Y, Furstenberg CT, Hanscom BS, … Kaufman PA (2010). Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: Impact of age and cognitive reserve. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4434–4440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Noll WW, Furstenberg CT, Guerin S, Cole B, & Mott LA (2003). The relationship of APOE genotype to neuropsychological performance in long-term cancer survivors treated with standard dose chemotherapy. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 612–619. doi: 10.1002/pon.742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA, Burris JL, Walsh E, Small BJ, & Jacobsen PB (2010). Attitudes toward information about genetic risk for cognitive impairment after cancer chemotherapy: Breast cancer survivors compared with healthy controls. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 3442–3447. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill ME, Wiener M, Stephens JA, Lohoff FW, & Coslett HB (2013). COMT and ANKK1-Taq-Ia genetic polymorphisms influence visual working memory. PLoS One, 8, e55862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegler KA, Chaoul MA, & Cohen L (2009). Cancer, cognitive impairment, and meditation. Acta Oncologica, 48, 18–26. doi: 10.1080/02841860802415535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K, Noble EP, Sheridan PJ, Montgomery A, Ritchie T, Jagadeeswaran P, … Cohn JB (1990). Allelic association of human dopamine-D2 receptor gene in alcoholism. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263, 2055–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.15.2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykoff N, Moieni M, & Subramanian SK (2009). Confronting chemobrain: An in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 3, 223–232. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0098-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Lo BCY, & Allen NB (2008). The impact of intensive mindfulness training on attentional control, cognitive style, and affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 303–322. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9119-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, Ma QD, Matsumoto M, Melhem S, … Weinberger DR (2004). Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): Effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. American Journal of Human Genetics, 75, 807–821. doi: 10.1086/425589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board. (2005). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2005/From-Cancer-Patient-to-Cancer-Survivor-Lost-in-Transition.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, & Hately-Aldous S (2006). A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: Physical and psychological benefits. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 891–897. doi: 10.1002/pon.1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan KA, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Schmitt FA, Munster P, & Jacobsen PB (2005). Cognitive functioning after adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer, 104, 2499–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins JS, Johnston SC, Ziv E, Kado D, Cauley JA, & Yaffe K (2007). Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677 T polymorphism and cognitive function in older women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166, 672–678. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DA, Kim WS, Jans DA, & Garner B (2007). Apoptosis induces neuronal apolipoprotein-E synthesis and localization in apoptotic bodies. Neuroscience Letters, 416, 206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Cahn-Weiner D, Jagust W, Baynes K, & Decarli C (2008). The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): Scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology, 22, 531–544. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, & Mischoulon D (2009). Folate in depression: Efficacy, safety, differences in formulations, and clinical issues. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 12–17. doi: 10.4088/JCP.8157su1c.03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson RJ, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, Furstenberg CT, Cole BF, & Mott LA (2007). Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psycho-Oncology, 16, 772–777. doi: 10.1002/pon.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson RJ, McDonald BC, Rocque MA, Furstenberg CT, Horrigan S, Ahles TA, & Saykin AJ (2012). Development of CBT for chemotherapy-related cognitive change: Results of a wait-list control trial. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 176–186. doi: 10.1002/Pon.1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PM, Holst KK, Adamsen D, Klein AB, Frokjaer VG, Jensen PS, … Knudsen GM (2015). BDNF Val66met and 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms predict a human in vivo marker for brain serotonin levels. Human Brain Mapping, 36, 313–323. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Castellon SA, Oppenheim A, Bower JE, Silverman DH, … Belin TR (2013). Cognitive complaints after breast cancer treatments: Examining the relationship with neuropsychological test performance. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 105, 791–801. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawler I, & Bedson P (2010). Meditation: An in-depth guide. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Gong P, Li J, Wang J, Lei X, Chen D, Zhang K, … Zhang F (2011). Variations in 5-HT2A influence spatial cognitive abilities and working memory. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 38, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher AE, & Collins FS (2002). Genomic medicine—a primer. New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 1512–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen M, Laakso A, Nagren K, Rinne JO, Pohjalainen T, & Hietala J (2004). C957 T polymorphism of the dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) gene affects striatal DRD2 availability in vivo. Molecular Psychiatry, 9, 1060–1061. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou QF, & Li SB (2009). Potential association of DRD2 and DAT1 genetic variation with heroin dependence. Neuroscience Letters, 464, 127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jim HS, Park JY, Permuth-Wey J, Rincon MA, Phillips KM, Small BJ, & Jacobsen PB (2012). Genetic predictors of fatigue in prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy: Preliminary findings. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 26, 1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly F, Rigal O, Noal S, & Giffard B (2011). Cognitive dysfunction and cancer: Which consequences in terms of disease management? Psycho-Oncology, 20, 1251–1258. doi: 10.1002/pon.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full-catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, & Burney R (1985). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8, 163–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, Peterson LG, Fletcher KE, Pbert L, … Santorelli SF (1992). Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri DK, Sambamurti K, & Bennett DA (2004). Apolipoprotein gene and its interaction with the environmentally driven risk factors: Molecular, genetic and epidemiological studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 25, 651–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang F, Wang Y, Qin W, Xing Q, Qian X, … Gao J (2014). Association between epsilon2/3/4, promoter polymorphism (-491A/T, -427T/C, and -219T/G) at the apolipoprotein E gene, and mental retardation in children from an iodine deficiency area, China. Biomedical Research International, 2014, 236–702. doi: 10.1155/2014/236702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Chen YA, Tsai YY, Qu X, Tseng TS, & Park JY (2012). TRM: A powerful two-stage machine learning approach for identifying SNP-SNP interactions. Annals of Human Genetics, 76, 53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00692.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky RH, Hu XZ, & Goldman D (2009). Additional functional variation at the SLC6A4 gene. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 150B, 153. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz A, Brefczynski-Lewis J, Johnstone T, & Davidson R (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLOS One, 3,e1897. doi: 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0001897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Kestler LJ, Mazzanti C, Bates JA, Goldberg T, & Goldman D (2002). A functional polymorphism in the COMT gene and performance on a test of prefrontal cognition. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 652–654. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, & Brown ML (2011). Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 103, 117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Cleak J, Willis-Owen SA, Flint J, & Shifman S (2007). Mapping regulatory variants for the serotonin transporter gene based on allelic expression imbalance. Molecular Psychiatry, 12, 421–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley KI, & Montgomery GW (2001). The genetics of cognitive processes: Candidate genes in humans and animals. Behavior Genetics, 31, 511–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Clark T, & Flint J (2005). Does measurement instrument moderate the association between the serotonin transporter gene and anxiety-related personality traits? A meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 10, 415–419. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JS (2012). Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment: The breast cancer experience. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, E31–E40. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E31-E40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2014). Database of single nucleotide polymorphisms (dbSNP). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/

- Neville MJ, Johnstone EC, & Walton RT (2004). Identification and characterization of ANKK1: A novel kinase gene closely linked to DRD2 on chromosome band 11q23.1. Human Mutation, 23, 540–545. doi: 10.1002/humu.20039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X, Bismil R, Chan K, Sicard T, Bulgin N, McMain S, & Kennedy JL (2006). Serotonin 2A receptor gene is associated with personality traits, but not to disorder, in patients with borderline personality disorder. Neuroscience Letters, 408, 214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EP (2000). The DRD2 gene in psychiatric and neurological disorders and its phenotypes. Pharmacogenomics, 1, 309–333. doi: 10.1517/14622416.1.3.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang PT, & Lu B (2004). Regulation of late-phase LTP and long-term memory in normal and aging hippocampus: Role of secreted proteins tPA and BDNF. Ageing Research Reviews, 3, 407–430. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezawas L, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Callicott JH, Kola-chana BS, Straub RE, … Weinberger DR (2004). The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and variation in human cortical morphology. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 10099–10102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto AC, & de Azambuja E (2011). Improving quality of life after breast cancer: Dealing with symptoms. Maturitas, 70, 343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polesskaya OO, & Sokolov BP (2002). Differential expression of the “C” and “T” alleles of the 5-HT2A receptor gene in the temporal cortex of normal individuals and schizophrenics. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 67, 812–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce G, Perez-Gonzalez R, Aragues M, Palomo T, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Jimenez-Arriero MA, & Hoenicka J (2009). The ANKK1 kinase gene and psychiatric disorders. Neurotoxicity Research, 16, 50–59. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada D, Colicino E, Power MC, Cox DG, Weisskopf MG, Hou L, … Baccarelli AA (2014). Influence of multiple APOE genetic variants on cognitive function in a cohort of older men—results from the normative aging study. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 223. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0223-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Hodgkinson CA, Martin-Soelch C, Shen PH, Szczepanik J, Nugent AC, … Drevets WC (2013). DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A polymorphism (rs1800497) has opposing effects on D2/3 receptor binding in healthy controls and patients with major depressive disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 16, 2095–2101. doi: 10.1017/S146114571300045X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Mellenbergh GJ, & van Dam FSAM (2006). Change in cognitive function after chemotherapy: A prospective longitudinal study in breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 98, 1742–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiepers OJ, Harris SE, Gow AJ, Pattie A, Brett CE, Starr JM, & Deary IJ (2012). APOE E4 status predicts age-related cognitive decline in the ninth decade: Longitudinal follow-up of the Lothian birth cohort 1921. Molecular Psychiatry, 17, 315–324. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Rawson KS, Walsh E, Jim HS, Hughes TF, Iser L, … Jacobsen PB (2011). Catechol-o-methyltransferase genotype modulates cancer treatment-related cognitive deficits in breast cancer survivors. Cancer, 117, 1369–1376. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, & Angen M (2000). A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Journal of Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellicy CJ, Harding MJ, Hamon SC, Mahoney JJ 3rd, Reyes JA, Kosten TR, … Nielsen DA (2014). A variant in ANKK1 modulates acute subjective effects of cocaine: A preliminary study. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 13, 559–564. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Collins B, Mackenzie J, Tomiak E, Verma S, & Bielajew C (2008). The cognitive effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in early stage breast cancer: A prospective study. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 122–130. doi: 10.1002/pon.1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swagell CD, Lawford BR, Hughes IP, Voisey J, Feeney GF, van Daal A, … Young RM (2012). DRD2 C957 T and TaqIA genotyping reveals gender effects and unique low-risk and high-risk genotypes in alcohol dependence. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 47, 397–403. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, … Mayeux R (1998). The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. Journal of the American Medical Association, 279, 751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueland PM, Hustad S, Schneede J, Refsum H, & Vollset SE (2001). Biological and clinical implications of the MTHFR C677 T polymorphism. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 22, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Rekha M, Vanitha N, … Kumar V (2009). Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 8, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/1534735409331456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Ah D, Habermann B, Carpenter JS, & Schneider BL (2013). Impact of perceived cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Schuhmacher A, Schwab S, Zobel A, & Maier W (2008). The His452Tyr variant of the gene encoding the 5-HT2A receptor is specifically associated with consolidation of episodic memory in humans. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 11, 1163–1167. doi: 10.1017/S146114570800905X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang Z, Wu Y, Yuan Y, Hou Z, & Hou G (2014). Association analysis of the catechol-O-methyltransferase/methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genes and cognition in late-onset depression. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 68, 344–352. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, Buzdar AU, Cruickshank S, & Meyers CA (2004). ‘Chemobrain’ in breast cancer?: A prologue. Cancer, 101, 466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefel JS, Saleeba AK, Buzdar AU, & Meyers CA (2010). Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer, 116, 3348–3356. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YL, Ding XX, Sun YH, Yang HY, Chen J, Zhao X, … Wu ZQ (2013). Association between MTHFR C677 T polymorphism and depression: An updated meta-analysis of 26 studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 46, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin XY, Ding JQ, & Chen SD (2010). Apolipoprotein E promoter polymorphisms and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from meta-analysis. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 19, 1283–1294. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]