Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies assessing the influence of vegetarian diets on breast cancer (BC) risk have produced inconsistent results. Few studies have assessed how the incremental decrease in animal foods and the quality of plant foods are linked with BC.

Objectives

Disentangle the influence of plant-based diet quality on BC risk between postmenopausal females.

Methods

Total of 65,574 participants from the E3N (Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale) cohort were followed from 1993–2014. Incident BC cases were confirmed through pathological reports and classified into subtypes. Cumulative average scores for healthful (hPDI) and unhealthful (uPDI) plant-based diet indices were developed using self-reported dietary intakes at baseline (1993) and follow-up (2005) and divided into quintiles. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate adjusted HR and 95% CI.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 21 y, 3968 incident postmenopausal BC cases were identified. There was a nonlinear association between adherence to hPDI and BC risk (Pnonlinear < 0.01). Compared to participants with low adherence to hPDI, those with high adherence had a lower BC risk [HRQ3 compared withQ1 (95% CI): 0.79 (0.71, 0.87) and HRQ4 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.78 (0.70, 0.86)]. In contrast, higher adherence to unhealthful was associated with a linear increase in BC risk [Pnonlinear = 0.18; HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.20 (1.08, 1.33); Ptrend < 0.01]. Associations were similar according to BC subtypes (Pheterogeneity > 0.05 for all).

Conclusions

Long-term adherence to healthful plant foods with some intake of unhealthy plant and animal foods may reduce BC risk with an optimal risk reduction in the moderate intake range. Adherence to an unhealthful plant-based diet may increase BC risk. These results emphasize the importance of the quality of plant foods for cancer prevention.

This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03285230).

Keywords: breast cancer, plant-based diet quality, dietary score, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, prospective study

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the leading global health challenges and, in 2020, accounted for an estimated 2.3 million new cases and 685,000 deaths worldwide [1]. In addition, it is one of the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years (15.1 million from 1990 – 2015) [2]. Cases are predicted to rise in the coming years, particularly postmenopausal BC and estrogen-positive (ER+) tumors [3, 4].

In addition to older age, several factors may contribute to BC risk. Armstrong et al. [5] estimated that the prevalence of genetic mutations accounting for hereditary BC ranged from 0.6%–36.9% internationally, leaving a sizable unexplained proportion potentially because of modifiable risk factors, including environmental exposures and reproductive and lifestyle factors [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. With the increase in life expectancy worldwide, there is a strong interest in identifying modifiable factors involved in the occurrence of BC. As such, research has focused on understanding lifestyle factors, particularly diet.

Plant-based diets have received extensive attention recently because of their benefits for individual health and environmental sustainability [11]. Vegetarian diets with a binary characterization in terms of exclusion or not of animal-based foods have long been explored in relation to BC risk, but the results are inconsistent [12]. Based on the incremental decrease in animal foods consumption and the notion that the nutritional quality is not consistent across all plant-based foods, Satija et al. [13] have recently proposed healthful and unhealthful plant-based dietary patterns. These indices have gained attention for their potential to prevent or manage chronic diseases [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. However, despite retrospective and prospective studies on the link between plant-based diet indices with BC, findings remain inconsistent [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]].

BC is a heterogeneous disease with several subtypes with unique disease progression and responses to treatment [26, 27]. ER+ and/or progesterone-positive (PR+) BCs have a substantial advantage from oncologic endocrine therapy in addition to chemotherapy, although the treatment of triple-negative BCs [estrogen-negative (ER-), progesterone-negative (PR-), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative] depends on chemotherapy alone [28, 29]. Even though a potential heterogeneity has been suggested in the associations between intakes of some nutrients [30], food groups [31], and dietary patterns [32, 33] and the risk of specific BC types according to, e.g., ER, PR status, and histology, to our knowledge, only 1 study investigated a potential heterogeneity in the association between a plant-based diet and BC by ER status [20].

Therefore, we aimed to clarify further the relationship between plant-based diet quality and BC risk overall and by subtypes of BC defined by ER and PR status and histology in participants from the Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (E3N) cohort study. Because the associations between BC risk and environmental factors have been found heterogeneous between pre and postmenopausal BC, the latter being the most frequent, we restricted our analyses to postmenopausal BC in this cohort of middle-aged and elderly participants.

Methods

E3N cohort

The E3N cohort was initiated in 1990 to investigate the risk factors of common cancers prospectively. Participants were 98,995 French females aged 40–65 y at inclusion, selected from the health insurance scheme covering workers in the National Education System and their families [34]. The study participants provided written informed consent, and the cohort study received ethical approval from the French National Commission for Computerized Data and Individual Freedom. Participants were enrolled in the cohort through a self-administered questionnaire followed by questionnaires every 2–3 y for sociodemographic factors, health conditions, reproductive factors, diet, and other lifestyle factors.

Study population

In the present study, follow-up began on the return date of the first dietary questionnaire for participants who were already menopausal at that time or the date of menopause if it occurred later. Participants contributed person-time until the date of diagnosis of any type of cancer except basal cell carcinoma, the date of the last completed questionnaire, or the date on which the last available follow-up questionnaire was mailed (November 17, 2014), whichever occurred first [35].

Between 74,522 participants who returned the dietary questionnaire sent in 1993, we first excluded those with undefined menopausal status (n = 14), those who had never menstruated (n = 6), prevalent cancer cases (n = 4709), those with incomplete or absent follow-up information (n = 623); we further excluded participants with extreme energy intake values, i.e., the 1st and 99th percentiles of the energy intake over energy requirement distribution in the population (n = 1364), those with missing BC receptor status data (n = 1309), and those who had not attained menopause at the end of follow-up (n = 923). Hence, our final study population included 65,574 postmenopausal participants (Supplemental Figure 1).

Dietary assessment and plant-based diet indices

Dietary data were collected at baseline (1993) and follow-up (2005) using a validated self-administered 208-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [36, 37]. Participants were asked about the frequency of consumption for 8 eating moments from breakfast to after-dinner snacks over the preceding year. According to the French meal patterns, portion sizes were assessed via photographs and qualitative questions on specific food and drink items. Nutrient and energy intakes were obtained using the Food Composition Database derived from the French Information Center on Food Quality [38].

The following indices were created using a procedure previously described [13]: healthful plant-based diet index (hPDI), which consisted of healthy plant foods, such as fruit, vegetables, nuts, and legumes, and the unhealthful PDI (uPDI), which consisted of primarily refined/processed foods as listed in Supplemental Table 1. First, we created 18 food groups (summing up the grams of consumed food items). Next, participants were categorized according to the quintile distribution (or a nonconsumer category plus quartiles between consumers) of their food intake for each food group. For each participant, values of 1–5 or reverse were assigned to each category based on the positive or negative association with the index; animal foods were reverse scored. The sum of the values for each food parameter led to the final hPDI and uPDI scores, which ranged from 18–90 (lowest to highest adherence).

These scores have been developed in the E3N cohort using only baseline dietary data [19]; however, in the present study, the scores from baseline (1993) and follow-up (2005) were averaged to capture better the long-term adherence and changes in diet over the long follow-up. In addition, baseline scores were used if participants were censored before the follow-up dietary questionnaire (2005). The baseline and cumulative average scores were used for the final analysis for 12,689 and 52,885 participants, respectively. The observed median values were 56 (range 27–79) for hPDI and 52.5 (range 27–78) for uPDI.

Incident BC ascertainment

All potential cases of BC were identified through baseline and follow-up questionnaires (3rd–11th) which inquired about cancer occurrence, contact details of participants’ physicians, and permission to contact them. A few BC cases were further identified from insurance files and death certificates. Tumor characteristics of hormonal receptor status ER and PR and histology (ductal, lobular, and other) were extracted using original clinical and pathology reports. The pathology reports were obtained for 95% of incident BC cases.

Covariates

The covariates were selected a priori based on literature evidence for their potential association with the exposure and/or the outcome. Education, physical activity (metabolic equivalents of task-hours per week [MET-h/wk]), and smoking status were self-reported at baseline. Breastfeeding and lifetime use of oral contraception and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) was assessed from the baseline and follow-up questionnaires. Age at menarche, history of benign breast disease, parity, and family history of BC was self-reported at baseline. Mammography performed in the previous follow-up cycle was captured from each follow-up questionnaire. BMI was assigned according to the value reported at baseline self-reported height and weight were used to calculate BMI, defined as the weight (kg) divided by squared height (m2). In the cohort, self-reported anthropometry is considered reliable from a validation study [39]. Lastly, alcohol consumption (g/d) and energy intake were calculated from the E3N FFQ.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics overall and according to hPDI and uPDI quintiles were described using means and SDs for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. HR and 95% CI of the BC risk was estimated using multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression with age as the time scale (entry time defined as the age at the baseline questionnaire or age at menopause, whichever was maximum). The proportional hazards assumption was tested graphically using Schoenfeld Residuals, and no major violations were observed [40].

All diet indices were analyzed in 3 ways. We first tested for nondeparture from a linear association and provided a graphical representation using restricted cubic splines [41]. The splines analyses were fitted with the fully adjusted model, and 5 knots were placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles. Second, when a linear association was confirmed, we assessed the HR of BC risk for a 1-SD increase in the diet index. Lastly, all diet indices were categorized into quintiles, and the first quintile group was considered the reference category to assess whether higher categories were associated with BC risk.

All models were stratified by 5-y birth cohorts, and 3 sets of multivariable Cox models were built by adding covariates: Model 1 was age-adjusted. Model 2 additionally included physical activity (continuous), educational level (undergraduate or less, graduate, and postgraduate or more), smoking status (current, former, and nonsmoker), family history of BC (yes, no), age at menarche (continuous), age at first childbirth (nulliparous, <30 y, ≥30 y), ever breastfeeding (yes, no), ever use of MHT (yes, no), ever use of the contraceptive pill (yes, no), past history of benign breast disease (yes, no), and mammography in the last follow-up cycle (yes, no). The final Model 3 also included potential diet and cancer association mediators, BMI (continuous), energy intake (excluding alcohol and continuous), and alcohol (continuous). The P value for linear trend was estimated in the models using the median score in each quintile. Subtypes of BC, characterized by hormone receptors and histology, were studied in separate Cox models. We used the Q statistic to test the homogeneity of the results between the receptor subtypes and histology [42].

In addition to the above-described primary analyses, we tested for effect modification of the overall associations by BMI (<20, 20–24.99, >25 kg/m2), use of MHT (yes, no), and physical activity (above or below median physical activity level, i.e., <37.97, ≥37.97 MET-h/wk) as suggested by previous studies [20, 43]. However, because of the small number of cases, the stratified analyses were not performed for the subtypes.

Missing observations were <5% for all variables except for ever breastfed and therefore were imputed to the median (for continuous variables) or mode (for categorical variables). For ever breastfed, a “missing” category was created to maintain the same number of participants in the analyses. All tests of statistical significance were 2-sided, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Sensitivity analyses

Several secondary analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the findings. First, missing values in the covariates were imputed with multiple imputations to overcome any systematic differences between the participants with complete and missing information. Second, the participants with BC diagnosed in the first 5 y of follow-up were excluded to overcome the influence of any reverse causation bias because of changes in diet after diagnosis of BC. Third, we analyzed the association of the overall PDI with the risk of BC. Fourth, we used the baseline and the time-dependent approaches to analyze dietary measurements across the follow-up. The cumulative average approach differs from the time-dependent approach in that the incident BC diagnosed between 2005 and 2014 was related to the average dietary intake reported on the 1993 and 2005 questionnaires instead of the dietary intake on the 2005 questionnaire only. Fifth, as we had too few cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (n =158) to conduct separate analyses, we performed additional analyses based only on invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) cases. Lastly, we excluded participants with energy limits <500 or >3500 kcal/d as proposed by Willett instead of the 1st and 99th percentiles energy distribution.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Three thousand nine hundred sixty-eight incident BC cases were diagnosed between 65,574 postmenopausal participants over approximately 21 y of follow-up. The average age of participants at baseline was 52.9 y (SD 6.7).

Participants in the highest quintile of cumulative average hPDI had lower BMI. They were more likely to have lower levels of energy and alcohol intake, to report lower use of the contraceptive pill, and to be former smokers than those in the lowest quintile. They were also more likely to report higher levels of physical activity, mammography history, benign breast disease, and ever use of MHT than participants in the lowest quintile (Table 1). The consumption in g/d of the food groups according to quintiles of cumulative average hPDI is presented in Supplemental Table 2. Participants in the highest quintile of cumulative average uPDI reported lower levels of energy and alcohol intakes and lower physical activity, were more likely to have lower BMI and lower proportion of excess weight, and were less likely to be current smokers, to report ever use of the contraceptive pill, to have a history of benign breast disease, and to have recent mammography than participants in the lowest quintile (Supplemental Table 3).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population overall and according to quintile of the healthful plant-based diet index, E3N (Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale) cohort (N = 65,574)1

| Characteristics | Quintile of the healthful plant-based diet index |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 65,574) | Q1 (N = 12,822) | Q2 (N = 12,832) | Q3 (N = 14,577) | Q4 (N = 13,008) | Q5 (N = 12,335) | |

| Age, y | 52.85 (6.65) | 51.90 (6.57) | 52.57 (6.64) | 52.97 (6.64) | 53.36 (6.68) | 53.46 (6.57) |

| Educational level, n (%) | ||||||

| Undergraduate or less | 7358 (11.22) | 1528 (11.91) | 1504 (11.72) | 1648 (11.31) | 1376 (10.58) | 1302 (10.56) |

| Graduate | 34,927 (53.26) | 6926 (54.02) | 6829 (53.22) | 7768 (53.28) | 7006 (53.86) | 6398 (51.86) |

| Postgraduate | 23,289 (35.52) | 4368 (34.07) | 4499 (35.06) | 5161 (35.41) | 4626 (35.56) | 4635 (37.58) |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 11.58 (13.90) | 13.17 (14.89) | 12.48 (14.42) | 11.57 (14.00) | 10.81 (13.15) | 9.80 (12.59) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 8826 (13.46) | 1769 (13.80) | 1755 (13.68) | 1923 (13.19) | 1733 (13.32) | 1646 (13.35) |

| Former | 21,348 (32.56) | 3846 (30.00) | 4019 (31.32) | 4786 (32.83) | 4377 (33.65) | 4320 (35.02) |

| Nonsmoker | 35,400 (53.98) | 7207 (56.20) | 7058 (55.00) | 7868 (53.98) | 6898 (53.03) | 6369 (51.63) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.92 (3.22) | 23.15 (3.48) | 23.00 (3.31) | 22.92 (3.14) | 22.89 (3.13) | 22.63 (3.00) |

| BMI categories, kg/m2, n (%) | ||||||

| <20 | 8826 (13.46) | 1769 (13.80) | 1755 (13.68) | 1923 (13.19) | 1733 (13.32) | 1646 (13.35) |

| 20–24.99 | 21,348 (32.56) | 3846 (30.00) | 4019 (31.32) | 4786 (32.83) | 4377 (33.65) | 4320 (35.02) |

| ≥25 | 35,400 (53.98) | 7207 (56.20) | 7058 (55.00) | 7868 (53.98) | 6898 (53.03) | 6369 (51.63) |

| Physical activity, MET-h/wk | 49.24 (49.52) | 47.66 (45.21) | 48.55 (48.88) | 48.90 (50.07) | 49.65 (49.00) | 51.57 (54.08) |

| Energy intake (excluding alcohol) kcal/d | 2129.36 (543.81) | 2441.27 (543.17) | 2226.76 (530.40) | 2097.45 (510.86) | 2001.04 (493.34) | 1876.83 (463.09) |

| Age at menarche, y | 12.78 (1.42) | 12.83 (1.42) | 12.80 (1.41) | 12.79 (1.42) | 12.76 (1.39) | 12.73 (1.42) |

| Age at menopause, y | 50.62 (3.82) | 50.62 (3.82) | 50.65 (3.81) | 50.65 (3.81) | 50.57 (3.82) | 50.58 (3.84) |

| Age at first birth, n (%) | ||||||

| <30 y | 51,384 (78.36) | 10,237 (79.84) | 10,182 (79.35) | 11,345 (77.82) | 10,099 (77.64) | 9521 (77.19) |

| ≥30 y | 6625 (10.10) | 1365 (10.65) | 1262 (9.83) | 1527 (10.48) | 1297 (9.97) | 1174 (9.51) |

| Nulliparous | 7565 (11.54) | 1220 (9.51) | 1388 (10.82) | 1705 (11.70) | 1612 (12.39) | 1640 (13.30) |

| Breastfeeding, n (%) | ||||||

| Ever | 37,772 (57.60) | 7482 (58.35) | 7386 (57.56) | 8350 (57.28) | 7390 (56.81) | 7164 (58.08) |

| Never | 24,380 (37.18) | 4682 (36.52) | 4785 (37.29) | 5475 (37.56) | 4916 (37.79) | 4522 (36.66) |

| Unknown | 3422 (5.22) | 658 (5.13) | 661 (5.15) | 752 (5.16) | 702 (5.40) | 649 (5.26) |

| Ever use of menopausal hormone therapy, n (%) | 19,761 (30.14) | 3404 (26.55) | 3812 (29.71) | 4417 (30.30) | 4203 (32.31) | 3925 (31.82) |

| Ever use of the contraceptive pill, n (%) | 39,816 (60.72) | 8263 (64.44) | 7927 (61.78) | 8818 (60.49) | 7674 (58.99) | 7134 (57.84) |

| Past history of benign breast disease, n (%) | 19,048 (29.05) | 3651 (28.47) | 3721 (29.00) | 4183 (28.70) | 3809 (29.28) | 3684 (29.87) |

| Family history of breast cancer, n (%) | 4841 (7.38) | 931 (7.26) | 929 (7.24) | 1135 (7.79) | 952 (7.32) | 894 (7.25) |

| Mammography in the last follow-up cycle, n (%) | 44,751 (68.25) | 8512 (66.39) | 8766 (68.31) | 9910 (67.98) | 9041 (69.50) | 8522 (69.09) |

| Healthful plant-based diet index (continuous) | 55.94 (6.07) | 47.35 (2.82) | 52.59 (1.02) | 56.01 (0.97) | 59.40 (1.01) | 64.64 (2.78) |

BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalents of task.

Continuous variables were described using means and SD, and categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages.

Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diet indices and BC risk overall

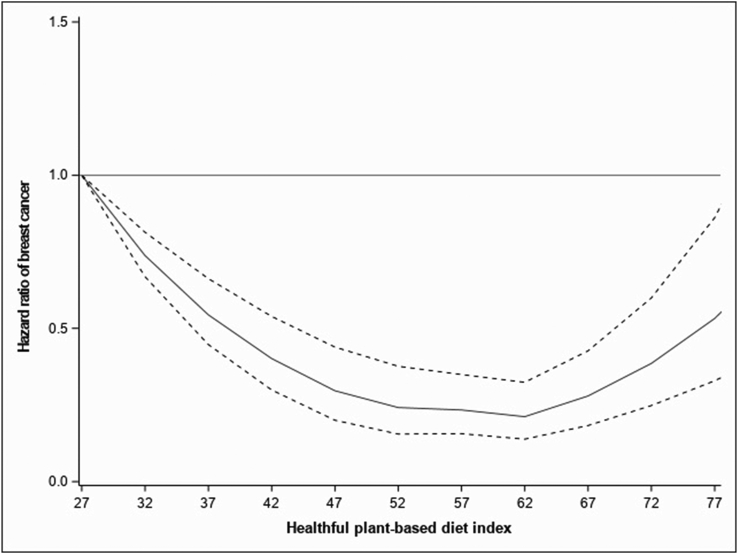

Table 2 and FIGURE 1, FIGURE 2, FIGURE 3 present the associations of cumulative average hPDI and uPDI with postmenopausal BC risk. After considering known BC risk factors, spline analysis showed a significant departure from linearity for the association between hPDI and BC risk (Pnonlinear < 0.01) (Figure 1). Participants with hPDI score intervals of approximately 52–62 had the lowest BC risk. Similarly, when the hPDI was modeled as a categorical variable, those in hPDI quintiles 3 and 4 had the lowest BC risk, 21% and 22%, respectively [fully adjusted model (Model 3), HRQ3 (95% CI): 0.79 (0.71, 0.87) and HRQ4 (95% CI): 0.78 (0.70, 0.86)] than those in the first quintile. Participants in the highest quintile 5 had a 14% lower risk of BC [HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.86 (0.77, 0.95)].

TABLE 2.

Association of the healthful and unhealthful plant-based diet indices with overall breast cancer risk, E3N (Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale) cohort (N = 65,574)

| Plant-based diet indices | Number noncases | Number cases | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |||

| Healthful plant-based diet index | |||||

| N = 61,606 | N = 3968 | ||||

| Pnonlinear | <0.01 | ||||

| Q1 | 11,960 | 862 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Q2 | 12,002 | 830 | 0.93 (0.85, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.03) |

| Q3 | 13,760 | 817 | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | 0.79 (0.71, 0.87) |

| Q4 | 12,290 | 718 | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | 0.76 (0.69, 0.84) | 0.78 (0.70, 0.86) |

| Q5 | 11,594 | 741 | 0.84 (0.76, 0.93) | 0.83 (0.75, 0.91) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.95) |

| Ptrend | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||

| Unhealthful plant-based diet index | |||||

| Pnonlinear | 0.18 | ||||

| 1-SD increase | N = 61,606 | N = 3968 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) |

| Q1 | 11,547 | 753 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Q2 | 12,955 | 813 | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.09) |

| Q3 | 11,575 | 711 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.04) | 0.95 (0.85, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.10) |

| Q4 | 13,414 | 837 | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.06) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.13) |

| Q5 | 12,115 | 854 | 1.10 (1.00, 1.22) | 1.11 (1.01, 1.23) | 1.20 (1.08, 1.33) |

| Ptrend | 0.12 | 0.06 | <0.01 | ||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Q, quintiles groups

Model 1: Adjusted for age (as the time scale), stratified by birth cohort.

Model 2: Model 1+ educational level, physical activity, smoking status, family history of breast cancer, breastfeeding, age at menarche, age at first full-term birth, past history of benign breast disease, ever use of the contraceptive pill, ever use of menopausal hormone therapy, and mammography in the last follow-up cycle.

Model 3: Model 2 + body mass index, energy intake, and alcohol.

FIGURE 1.

Associations of the healthful plant-based diet index with BC fitted with restricted cubic splines (N = 65,574; 5 knots placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles), Pnonlinear < 0.01. Risk estimates were adjusted for age (as the time scale), educational level, physical activity, smoking status, family history of BC, breastfeeding, age at menarche, age at first full-term birth, past history of benign breast disease, ever use of the contraceptive pill, ever use of menopausal hormone therapy, mammography in the last follow-up cycle, body mass index, energy intake, and alcohol (model stratified by birth cohort). The solid line represents the hazard ratio, and the dashed lines the lower and upper 95% confidence interval. BC, breast cancer.

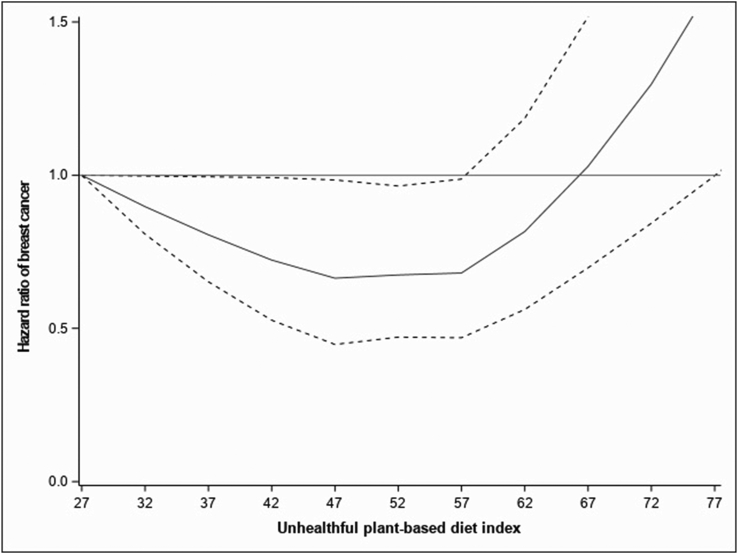

FIGURE 2.

Associations of the unhealthful plant-based diet index with BC fitted with restricted cubic splines (N = 65,574; 5 knots placed at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles), Pnonlinear = 0.18. Risk estimates were adjusted for age (as the time scale), educational level, physical activity, smoking status, family history of BC, breastfeeding, age at menarche, age at first full-term birth, past history of benign breast disease, ever use of the contraceptive pill, ever use of menopausal hormone therapy, mammography in the last follow-up cycle, body mass index, energy intake, and alcohol (model stratified by birth cohort). The solid line represents the hazard ratio, and the dashed lines the lower and upper 95% confidence interval. BC, breast cancer.

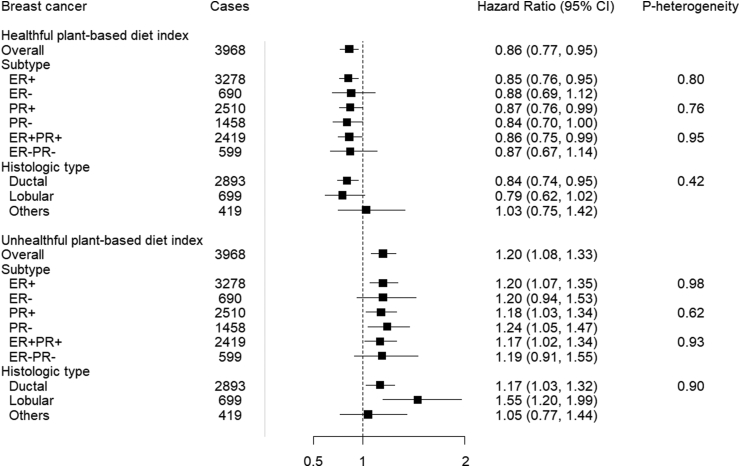

FIGURE 3.

The healthful and unhealthful plant-based diet indices and breast cancer risk, overall and subtypes, E3N (Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l'Education Nationale) cohort (N = 65,574). Hazard ratios (Model 3)1 for the highest (Q5) compared with the lowest (Q1) quintiles was presented in the figure. CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; HR, hazard ratio; PR, progesterone receptor. 1HR adjusted for age (as the time scale), educational level, physical activity, smoking status, family history of breast cancer, breastfeeding, age at menarche, age at first full-term birth, past history of benign breast disease, ever use of the contraceptive pill, ever use of menopausal hormone therapy, mammography in last follow-up cycle, body mass index, energy intake, and alcohol (model stratified by birth cohort).

In contrast, for cumulative average uPDI, the spline analysis was consistent with a linear relation (Pnonlinear = 0.18) (Figure 2). Modeled as a continuous variable, uPDI resulted in a 4% higher risk of BC [Model 3, HR1-SD increase (95% CI): 1.04 (1.01, 1.08)]. When quintile groups of uPDI were considered, a 20% higher risk for the highest compared with the lowest quintile was observed [Model 3, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.20 (1.08, 1.33); Ptrend < 0.01]. Since the HRs changed substantially from Model 2 to 3, we adjusted energy intake, alcohol, and BMI individually to assess which variables could be driving the associations. We observed the following changes: adjusting for BMI, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.14 (1.03, 1.26), for energy intake, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.17 (1.05, 0.30), and for alcohol, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.13 (1.03, 1.25). The greatest variation in HR occurred when adjusting for energy intake, suggesting that this variable could be an important confounder or mediator of the association between uPDI and BC risk.

Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diet indices according to hormone receptor and histologic subtypes

When investigating the association of cumulative average hPDI according to BC subtypes, we did not observe heterogeneity by either receptor status or histology (Pheterogeneity > 0.05 for all) (Supplemental Tables 4–7). For example, in the fully adjusted model, when we compared the risks associated with quintile 5 of hPDI for PR+ and PR-, we observed 13% and 16% lower risks, respectively [HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) and 0.84 (0.70, 1.00); Pheterogeneity = 0.76] (Figure 3). For ER+ BC, participants in the highest quintile of hPDI had a 15% lower BC risk [HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.85 (0.76, 0.95)] compared with participants in the lowest quintile. For ER- BC, there was a lower risk for the first 2 quintiles and a null association for quintile 5 [HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.88 (0.69, 1.12)] (Supplemental Table 4). The HRsQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) for ER+PR+ and ER-PR- BC was 0.86 (0.75, 0.99) and 0.87 (0.67, 1.14), respectively (Supplemental Table 6). Lastly, for ductal and lobular BC, the HRsQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) were 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) and 0.79 (0.62, 1.02), respectively (Supplemental Table 7).

In subgroup analyses for cumulative average uPDI, in the fully adjusted model, participants in the highest intake quintile had a 20% higher risk of ER+ BC, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.20 (1.07, 1.35); Ptrend < 0.01, albeit we did not observe heterogeneity by either receptor status or histology (Pheterogeneity > 0.05 for all) (Figure 3). Corresponding HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) for ER- BC was 1.20 (0.94, 1.53); Ptrend = 0.45 (Supplemental Table 4). In addition, there was an 18% and 24% higher risk of PR+ and PR- BC, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.18 (1.03, 1.34); Ptrend = 0.02 and 1.24 (1.05, 1.47); Ptrend = 0.02, respectively (Supplemental Table 5). Corresponding HRsQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) for ER+PR+ and ER-PR- BC were 1.17 (1.02, 1.34), Ptrend = 0.02 and 1.19 (0.91, 1.55), Ptrend = 0.57, respectively (Supplemental Table 6). Lastly, there were positive associations for both ductal and lobular BCs, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 1.17 (1.03, 1.32), Ptrend = 0.02, and 1.55 (1.20, 1.99), Ptrend < 0.01, respectively (Supplemental Table 7).

Stratified analyses

There were no interactions between cumulative average hPDI and uPDI and BMI, MHT use, or physical activity with respect to BC risk (Pinteraction > 0.05 for all) (Supplemental Tables 8–10 and Supplemental Figure 2).

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses using multiple imputations to handle missing covariates, a similar pattern of results was obtained than those of the primary analysis (results not tabulated). In addition, results were unchanged when excluding participants diagnosed in the first 5 y of follow-up, suggesting that reverse causation was unlikely to explain the findings (results not tabulated).

We found evidence for a nonlinear association between the cumulative average overall PDI and BC risk (Pnonlinear = 0.03). Considering quintiles of PDI in the fully adjusted model, there was a lower risk of BC from quintiles 2–4 [HRQ2 (95% CI): 0.83 (0.75, 0.92) – HRQ4 (95% CI): 0.84 (0.76, 0.93)] which attenuated in quintile 5 [HR (95% CI): 0.94 (0.85, 1.04)].

Furthermore, when using scores derived by FFQ at baseline in Model 3, there was a linear association between PDI (Pnonlinear = 0.51), hPDI (Pnonlinear = 0.86), and uPDI (Pnonlinear = 0.11), and BC risk. Considering a 1-SD increase in hPDI in Model 3, there was a 3% lower risk of BC [HR (95% CI): 0.97 (0.93, 1.00)]. Considering quintiles of baseline hPDI, there was an 11% lower risk of BC [HR (95% CI): 0.89 (0.81, 0.99); Ptrend < 0.01] in Model 1, while full adjustment attenuated the association, HR (95% CI): 0.92 (0.83, 1.02); Ptrend = 0.06. Conversely, for baseline uPDI, there was a 4% increase in risk for a 1-SD increase [HR (95% CI): 1.04 (1.01, 1.08)]. As quintiles of uPDI, in Model 3, there was a 13% higher risk [HR (95% CI): 1.13 (1.02, 1.26); Ptrend = 0.02]. We found no association between baseline overall PDI and BC risk (results not tabulated).

When considering the time-dependent indexes in the fully adjusted model, for each 1-SD increase, the HRs (95% CI) for overall BC risk were as follows: PDI, 0.977 (0.969, 0.985); hPDI, 0.991 (0.983, 0.999); and uPDI, 0.997 (0.988, 1.005). For the quintiles group analysis, the HR (95% CI) for overall BC risk were as follows: PDI, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.94 (0.91, 0.96); hPDI, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.97 (0.94, 1.00); and uPDI, HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI): 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) (results not tabulated).

The HRs CI for IDC was not materially different from our primary analysis; for cumulative average hPDI and uPDI, in the fully adjusted model, the HRQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) were 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) and 0.18 (1.04, 1.34); Ptrend < 0.01, respectively (results not tabulated).

Lastly, when we used energy limits proposed by Willett, the results did not change materially, and the direction of the association remained. For cumulative average hPDI and uPDI in the fully adjusted model, the HRsQ5 compared with Q1 (95% CI) were 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) and 1.16 (1.05, 1.28); Ptrend = 0.02, respectively.

Discussion

The French E3N prospective cohort study observed a nonlinear association between adherence to hPDI and BC risk, with the lowest risk for moderate adherence. In contrast, higher adherence to uPDI was positively associated with BC risk. In addition, we found no heterogeneity between adherence to these plant-based diet indices and BC risk across tumor subtypes. These results suggest that hPDI could have a preventive influence and uPDI a promotive influence on all types of BC, thus acting independently of hormonal mechanisms and reflecting the importance of plant-based diet quality in BC prevention in postmenopausal females.

Our findings of a differential pattern of association between a plant-based diet and postmenopausal BC risk by the quality of plant foods were observed in previous studies. In a cohort study of more than 150,000 participants from the Nurses’ Health Studies, an inverse association was observed with hPDI. However, they did no evidence of any increased risk of overall BC with uPDI [20]. Moreover, in a case-control study on 350 cases and 700 controls from Iran, there were lower odds of BC in postmenopausal participants with the greatest adherence to hPDI, whereas the greatest adherence to uPDI was associated with higher odds [21], although in another case-control study on 412 cases and 456 controls, hPDI was associated with lower odds, no association was observed with uPDI [23]. Furthermore, in a Mediterranean cohort study of 10,812 participants, neither the healthful nor the unhealthful provegetarian patterns were associated with postmenopausal BC risk [25].

Although a nonlinear association between high-quality plant foods such as fruit and vegetables and BC risk has not been reported so far, a nonlinear association between dietary folate intake and BC risk in the EPIC cohort was suggested [44]. However, such an association has already been reported for colorectal cancer. For example, a meta-analysis of 19 prospective studies conducted by Aune et al. [45] reported a nonlinear association between fruit and vegetable intake and colorectal cancer risk, with the greatest risk reduction in the lower intake range. Furthermore, a meta-analysis by Schwingshackl et al. [46] reported nonlinear associations between vegetables, fruit, and nuts with all-cause mortality.

We found no heterogeneity across BC subtypes in our study. The risk of BC by receptor and histological subtypes has not been extensively studied. As regards the association between dietary patterns and ductal and lobular carcinoma, studies support the findings of an inverse risk between the Mediterranean diet and risk of IDC and invasive lobular carcinoma BC and a positive association between the Western diet and IDC and invasive lobular carcinoma BC [47]; however, literature is scarce for associations between BC histological types and plant-based diets. The Nurses’ Health Studies reported heterogeneity by ER receptor status, with the strongest association between hPDI and ER- tumors [20].

The discrepancies in findings of these studies could partly be attributed to varying sample sizes, differences in the development of scores using 18- [20, 25] or 16- food group constructs [21], dietary measurement errors, the duration of follow-up (which varies between 115,802 and over 4,841,083 person-years of follow-up for prospective studies), as well as the nonreporting in some studies of the potential deviation from the linearity of association.

Several potential biological mechanisms support a protective role of hPDI toward BC risk. The healthful plant-predominant dietary pattern is characterized by high fiber, fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes, and low red and processed meat. Hence, abundant antioxidants, vitamins, and fiber could have anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activities [[48], [49], [50]]. Furthermore, there is experimental evidence that polyphenols in fruit and vegetables inhibit the proliferation of ductal carcinoma in situ BC [51]. High fiber also reduces the total body pool of estrogen, thus helping reduce BC risk [52]. Similarly, phytoestrogens which are plant-derived estrogen-like compounds, have anticarcinogenic effects of their own and via lowering the amount of circulating estrogen; meta-analyses have reported that dietary lignans, a class of phytoestrogen found in vegetables, fruit, and whole grains, green tea, and oilseeds, were associated with lower BC risk in postmenopausal participants [53, 54]. In France, a high dietary intake of plant lignans and enterolignans was associated with lower ER+ and PR+ postmenopausal BC risk [55]. On the other hand, less healthful plant-based foods are poor in fiber and micronutrients and laden with carbohydrates with tumor-promoting potential via effects on circulating insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 [56, 57]. Trans-fatty acids in industrially processed salty foods, sweets, and other packaged foods influence systemic inflammation, visceral adiposity, body weight, and insulin resistance, increasing BC risk [[58], [59], [60]]. Furthermore, polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites reduce estrogen binding to serum-binding proteins increasing circulating levels and activating breast cell growth [61]. More evidence on the effects of bioactive metabolites of various compounds could shed light on these findings.

This study has some important strengths. First, the prospective nature of the study design precluded recall and selection biases with high retention over a long follow-up period. Second, the large sample size provided statistical power to detect associations. Third, the large number of incident cases allowed us to analyze by receptor and histological subtypes. Fourth, validated FFQs were used to collect dietary intake data before BC diagnosis. We used the cumulative average diet scores, thus accounting for possible changes in dietary habits during the follow-up period and better reflecting long-term dietary adherence. Fifth, excluding participants with BC diagnosed in the first 5 y of follow-up did not change our results, suggesting that reverse causation was unlikely to explain our findings. Lastly, when we applied the Willett energy exclusion criteria, although it reduced the study population and the study power, the results were somewhat stronger and in favor of a true association.

However, this study was met with some limitations. First, although we adjusted for the most known confounding factors of BC, there could still be some bias from unmeasured confounders because of the study’s observational nature. Second, self-reported dietary intake was used as exposure information. Although the FFQ has been validated, some degree of nondifferential exposure misclassification is likely, which is usually considered to bias the results toward the null in a prospective setting such as ours, although a recent paper suggests that there are possibilities of opposite bias [62]. Lastly, our highly educated participants might be more health-conscious. They may not be a representative sample of the general French population, limiting our results’ external validity. However, considering the dietary variations in the general population, there is a higher possibility of finding stronger associations between these indices and the risk of BC.

In conclusion, the results showed a nonlinear risk reduction between hPDI and BC, with the lowest BC risk for moderate adherence and a linear risk increase between uPDI and BC between postmenopausal females. These findings have implications for all subtypes of BC and support the notion of the importance of the quality of plant-based foods when consuming plant-predominant diets with a balance of animal foods. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings and better understand the underlying mechanisms involved in these associations. Lastly, more studies are required to determine the associations in relation to premenopausal BC, as there are different mechanisms for hormone-related BC in pre and postmenopausal females. Because premenopausal BCs are less frequent than postmenopausal BCs, a collaborative study of several cohorts would be an ideal setting.

Funding

This research was conducted using data from Inserm's E3N cohort with the support of the MGEN, Institut Gustave Roussy and the “Ligue contre le Cancer” for the constitution and maintenance of the E3N cohort. This work has also benefited from State aid managed by the National Research Agency under the program "Investissement d’avenir" under the reference ANR-10-COHO-0006 as well as a subsidy from the "Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur de la recherche et de l’innovation" for public service charges under the reference n°2103 586016.Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policies, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/ World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out using data from the INSERM (French National Institutes for Health and Medical Research) E3N cohort, which was established and maintained with the support of the Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (MGEN), Gustave Roussy, and the French League against Cancer (LNCC). E3N-E4N is also supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the Investment for the Future Program (PIA) (ANR-10-COHO-0006) and by the French Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation (subsidy for public service charges n°2103 586016). We thank all participants for their continued participation. We are also grateful to all members of the E3N study group.

Author contribution

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows: SS, MCBR, and NL conceived and designed the study. MCBR and NL contributed equally as the last authors. SS performed the statistical analysis and drafted the original manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data discussed in the manuscript, revised it, and approved its final version to be published. NL is the guarantor of this work and, as such, has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. SS is supported by a doctoral funding from l'Ecole Doctorale de Santé Publique, Ministère de l'enseignement supérieur, de la recherche et de l’innovation. NL is supported by a research fellowship from the Fondation de France.

Conflicts of interest

All other authors reports no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2022.11.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lei S., Zheng R., Zhang S., Wang S., Chen R., Sun K., et al. Global patterns of breast cancer incidence and mortality: A population-based cancer registry data analysis from 2000 to 2020. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2021;41(11):1183–1194. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzmaurice C., Allen C., Barber R.M., Barregard L., Bhutta Z.A., Brenner H., et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heer E., Harper A., Escandor N., Sung H., McCormack V., Fidler-Benaoudia M.M. Global burden and trends in premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(8):e1027–e1037. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30215-1. e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg P.S., Barker K.A., Anderson W.F. Estrogen receptor status and the future burden of invasive and in situ breast cancers in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(9) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong N., Ryder S., Forbes C., Ross J., Quek R.G. A systematic review of the international prevalence of BRCA mutation in breast cancer. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:543–561. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S206949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Momenimovahed Z., Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer. 2019;11:151–164. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S176070. Dove Med Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernier M.O., Plu-Bureau G., Bossard N., Ayzac L., Thalabard J.C. Breastfeeding and risk of breast cancer: a metaanalysis of published studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(4):374–386. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormack V.A., Boffetta P. Today’s lifestyles, tomorrow’s cancers: trends in lifestyle risk factors for cancer in low- and middle-income countries. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(11):2349–2357. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormack V.A., dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotepui M. Diet and risk of breast cancer. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2016;20(1):13–19. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.40560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fresán U., Sabaté J. Vegetarian diets: planetary health and its alignment with human health. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(Suppl_4):S380–S388. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godos J., Bella F., Sciacca S., Galvano F., Grosso G. Vegetarianism and breast, colorectal and prostate cancer risk: an overview and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(3):349–359. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Rimm E.B., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Borgi L., et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of Type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLOS Med. 2016;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Manson J.E., Willett W., et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(4):411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouvari M., Tsiampalis T., Chrysohoou C., Georgousopoulou E., Skoumas J., Mantzoros C.S., et al. Quality of plant-based diets in relation to 10-year cardiovascular disease risk: the Attica cohort study. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61(5):2639–2649. doi: 10.1007/s00394-022-02831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song S., Lee K., Park S., Shin N., Kim H., Kim J. Association between unhealthful plant-based diets and possible risk of dyslipidemia. Nutrients. 2021;13(12) doi: 10.3390/nu13124334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z., Qian F., Liu G., Li M., Voortman T., Tobias D.K., et al. Prepregnancy plant-based diets and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study of 14,926 women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(6):1997–2005. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J., Kim H., Giovannucci E.L. Quality of plant-based diets and risk of hypertension: a Korean genome and examination study. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(7):3841–3851. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laouali N., Shah S., MacDonald C.J., Mahamat-Saleh Y., El Fatouhi D., Mancini F., et al. BMI in the associations of plant-based diets with Type 2 diabetes and hypertension risks in women: the E3N prospective cohort study. J Nutr. 2021;151(9):2731–2740. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romanos-Nanclares A., Willett W.C., Rosner B.A., Collins L.C., Hu F.B., Toledo E., et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and risk of breast cancer in U.S. Women: results from the nurses’ health studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(10):1921–1931. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rigi S., Mousavi S.M., Benisi-Kohansal S., Azadbakht L., Esmaillzadeh A. The association between plant-based dietary patterns and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3391–3392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82659-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane-Diallo A., Srour B., Sellem L., Deschasaux M., Latino-Martel P., Hercberg S., et al. Association between a pro plant-based dietary score and cancer risk in the prospective NutriNet-sante cohort. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(9):2168–2176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasanfar B., Toorang F., Booyani Z., Vassalami F., Mohebbi E., Azadbakht L., et al. Adherence to plant-based dietary pattern and risk of breast cancer among Iranian women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(11):1578–1587. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-00869-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payandeh N., Shahinfar H., Amini M.R., Jafari A., Safabakhsh M., Imani H., et al. The lack of association between plant-based dietary pattern and breast cancer: a hospital-based case-control study. Clin Nutr Res. 2021;10(2):115–126. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2021.10.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romanos-Nanclares A., Toledo E., Sánchez-Bayona R., Sánchez-Quesada C., Martínez-González M.Á., Gea A. Healthful and unhealthful provegetarian food patterns and the incidence of breast cancer: results from a Mediterranean cohort. Nutrition. 2020;79-80 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2020.110884. –85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polyak K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):3786–3788. doi: 10.1172/JCI60534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamimi R.M., Baer H.J., Marotti J., Galan M., Galaburda L., Fu Y., et al. Comparison of molecular phenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(4):R67–R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ignatiadis M., Sotiriou C. Luminal breast cancer: from biology to treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(9):494–506. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffiths C.L., Olin J.L. Triple negative breast cancer: a brief review of its characteristics and treatment options. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(3):319–323. doi: 10.1177/0897190012442062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fung T.T., Hu F.B., Hankinson S.E., Willett W.C., Holmes M.D. Low-carbohydrate diets, dietary approaches to stop hypertension-style diets, and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(6):652–660. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y., Huang R., Wang M., Bernstein L., Bethea T.N., Chen C., et al. Dairy foods, calcium, and risk of breast cancer overall and for subtypes defined by estrogen receptor status: a pooled analysis of 21 cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(2):450–461. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J.H., Peng C., Rhee J.J., Farvid M.S., Willett W.C., Hu F.B., et al. Prospective study of a diabetes risk reduction diet and the risk of breast cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(6):1492–1503. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayati Z., Montazeri V., Shivappa N., Hebert J.R., Pirouzpanah S. The association between the inflammatory potential of diet and the risk of histopathological and molecular subtypes of breast cancer in northwestern Iran: results from the Breast Cancer Risk and Lifestyle study. Cancer. 2022;128(12):2298–2312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clavel-Chapelon F., E3N Study Group Cohort profile: the French E3N cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):801–809. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cottet V., Touvier M., Fournier A., Touillaud M.S., Lafay L., Clavel-Chapelon F., et al. Postmenopausal breast cancer risk and dietary patterns in the E3N-EPIC prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(10):1257–1267. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas F., Niravong M., Villeminot S., Kaaks R., Clavel-Chapelon F. Estimation of food portion size using photographs: validity, strengths, weaknesses and recommendations. J Hum Nutr Diet. 1995;8(1):65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.1995.tb00296.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Liere M. Relative validity and reproducibility of a French dietary history questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(suppl 1):128S–136. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.S128. 90001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jean-Claude F., JI R., CT M.F. FRA); Paris: 1995. Répertoire général des aliments: table de composition = Composition tables. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tehard B., van Liere M.J., Com Nougué C., Clavel-Chapelon F. Anthropometric measurements and body silhouette of women: validity and perception. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(12):1779–1784. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69(1):239–241. doi: 10.1093/biomet/69.1.239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrell F.E. Springer; 2013. Regression Modeling Strategies: with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison P.D. 2nd ed. SAS Institute Inc; 2010. Survival Analysis Using SAS®: A Practical Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velie E.M., Schairer C., Flood A., He J.P., Khattree R., Schatzkin A. Empirically derived dietary patterns and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in a large prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(6):1308–1319. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Puyvelde H., Papadimitriou N., Clasen J., Muller D., Biessy C., Ferrari P., et al. Dietary methyl-group donor intake and breast cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) Nutrients. 2021;13(6) doi: 10.3390/nu13061843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aune D., Lau R., Chan D.S., Vieira R., Greenwood D.C., Kampman E., et al. Nonlinear reduction in risk for colorectal cancer by fruit and vegetable intake based on meta-analysis of prospective studies. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):106–118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwingshackl L., Schwedhelm C., Hoffmann G., Lampousi A.M., Knuppel S., Iqbal K., et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(6):1462–1473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.153148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dianatinasab M., Rezaian M., HaghighatNezad E., Bagheri-Hosseinabadi Z., Amanat S., Rezaeian S., et al. Dietary patterns and risk of invasive ductal and lobular breast carcinomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;20(4):e516–e528. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samtiya M., Aluko R.E., Dhewa T., Moreno-Rojas J.M. Potential health benefits of plant food-derived bioactive components: an overview. Foods. 2021;10(4) doi: 10.3390/foods10040839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandey K.B., Rizvi S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2(5):270–278. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu R.H. Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(3) doi: 10.3945/an.112.003517. 384S–92S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nemec M.J., Kim H., Marciante A.B., Barnes R.C., Hendrick E.D., Bisson W.H., et al. Polyphenolics from mango (Mangifera indica L.) suppress breast cancer ductal carcinoma in situ proliferation through activation of AMPK pathway and suppression of mTOR in athymic nude mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;41:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore M.A., Park C.B., Tsuda H. Soluble and insoluble fiber influences on cancer development. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998;27(3):229–242. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buck K., Zaineddin A.K., Vrieling A., Linseisen J., Chang-Claude J. Meta-analyses of lignans and enterolignans in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(1):141–153. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Velentzis L.S., Cantwell M.M., Cardwell C., Keshtgar M.R., Leathem A.J., Woodside J.V. Lignans and breast cancer risk in pre- and post-menopausal women: meta-analyses of observational studies. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(9):1492–1498. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Touillaud M.S., Thiébaut A.C., Fournier A., Niravong M., Boutron-Ruault M.C., Clavel-Chapelon F. Dietary lignan intake and postmenopausal breast cancer risk by estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(6):475–486. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rose D.P., Vona-Davis L. The cellular and molecular mechanisms by which insulin influences breast cancer risk and progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19(6):R225–R241. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowers L.W., Rossi E.L., O’Flanagan C.H., deGraffenried L.A., Hursting S.D. The role of the insulin/IGF system in cancer: lessons learned from clinical trials and the energy balance-cancer link. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:77–78. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chajes V., Thiebaut A.C., Rotival M., Gauthier E., Maillard V., Boutron-Ruault M.C., et al. Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1312–1320. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Micha R., Mozaffarian D. Trans fatty acids: effects on metabolic syndrome, heart disease and diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(6):335–344. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matta M., Huybrechts I., Biessy C., Casagrande C., Yammine S., Fournier A., et al. Dietary intake of trans fatty acids and breast cancer risk in 9 European countries. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):81–82. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01952-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rose D.P. Effects of dietary fatty acids on breast and prostate cancers: evidence from in vitro experiments and animal studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(6):1513S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.6.1513S. suppl. 22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yland J.J., Wesselink A.K., Lash T.L., Fox M.P. Misconceptions about the direction of bias from nondifferential misclassification. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(8):1485–1495. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.