Abstract

Background:

Recent US data on unsafe sexual behaviors among viremic HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) are limited.

Method:

Using data abstracted from medical records of the participants in the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS) and a supplemental behavioral survey, we assessed the frequency of high-risk sexual practices among HIV-infected MSM in care and examined the factors associated with risky sexual practices. We also compared the frequency of unprotected anal sex (UAS) with HIV-negative or unknown serostatus partners among viremic (HIV viral load ≥400 copies per milliliter) vs virologically suppressed (HIV viral load <400 copies per milliliter) MSM.

Results:

Among 902 HIV-infected MSM surveyed, 704 (78%) reported having sex in the past 6 months, of whom 54% reported UAS (37% insertive, 42% receptive) and 40% UAS with a male partner who was HIV-negative or of unknown serostatus (24% insertive, 31% receptive). In multivariable regression with an outcome of engaging in any UAS with a male partner who was HIV-negative or of unknown serostatus, MSM aged <50 years, who reported injection drug use risk, had ≥2 sex partners, and who disclosed their HIV status to some but not to all of their sex partners were more likely to report this practice. Among MSM who reported any UAS, 15% were viremic; frequency of the UAS did not differ between viremic and virologically suppressed MSM.

Conclusions:

The high frequency of UAS with HIV-negative or unknown-status partners among HIV-infected MSM in care suggests the need for targeted prevention strategies for this population.

Keywords: HIV, risk behavior, unprotected sex, viremia, TACASI

INTRODUCTION

Well into the third decade of the HIV epidemic in the United States, >1 million Americans are estimated to be living with HIV infection,1,2 and approximately 50,000 new persons become infected each year.3 Men who have sex with men (MSM) and persons of black and Hispanic race/ethnicity continue to account for most new HIV infections in the United States.3 HIV-infected persons who are unaware of their HIV status and engage in unprotected sex with HIV-negative or unknown-status partners contribute to nearly half of all new HIV infections.4 Unprotected sexual risk behaviors not only put uninfected partners at the risk of developing HIV infection but also place HIV-infected individuals at the risk of acquiring other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs; eg, syphilis, gonorrhea, and herpes)5,6 and possibly superinfection with another strain of HIV.7–9

Risk for onward transmission is higher for viremic persons.10,11 Viremia, or elevated virus levels, can be a marker of poor antiviral medication adherence, and persons who are nonadherent may also be more likely to engage in unprotected sex,12 an association that may be explained by shared underlying psychological, socioeconomic, or structural risk factors.13 Thus, if viremia were associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behavior, viremic patients could be at an increased risk of onward HIV transmission on 2 counts: higher viral dose per exposure and more exposure opportunities to transmit.

The reported rates of unprotected sex among HIV-infected adults and adolescents vary widely by HIV risk group, by demography and geography, types of partners and practices, and by calendar period of observation.13–20 Reported rates of unprotected penetrative sex between HIV-infected MSM and partners of unknown or negative HIV status during the preceding 3–6 months have ranged from 13% to 43%,21,22 and in aggregated findings from 30 studies,20 the prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse with any male partner was 43%. Using data from the HIV Outpatient Study (HOPS), we sought to describe the rates of high-risk sexual practices among HIV-infected MSM in care, to identify factors associated with unprotected sex, and to assess whether rates of risky sexual behavior were higher among viremic men versus virologically suppressed men.

METHODS

The HIV Outpatient Study

The HOPS is an ongoing prospective observational cohort study of HIV-infected adults who have received care at 1 of 8 participating HIV clinics (university-based, public, and private) in 6 US cities (Chicago, IL; Denver, CO; Stonybrook, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Tampa, FL; and Washington, DC) since 1993. The HOPS is an open cohort: patients may enter the study at any point after a diagnosis of HIV infection regardless of treatment history and may leave the study at any point for a variety of reasons (eg, patient request, death, or loss to follow-up).23 Since its inception, the HOPS protocol has been reviewed and approved annually by the institutional review boards at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA), Cerner Corporation (Vienna, VA), and each of the local sites. Patient data, including sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses, antiretroviral (ARV) and other treatments, and laboratory values [including CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts (CD4 count) and HIV RNA viral loads (HIV VL)] were abstracted from medical charts and entered into an electronic database by trained medical record abstractors with backgrounds in nursing or other healthcare-related fields.

In 2007, a supplemental annual survey was introduced that collected information on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and risk behaviors using a brief telephone audio computer-assisted self-interview (TACASI). HOPS patients were assigned a unique 4-digit number and asked to complete the survey by dialing a toll-free telephone number from a private location in the clinic or from home. Patients’ responses on the TACASI were kept confidential, and individual responses were not available to their HIV care providers. Data collected by TACASI included sociodemographic information; use of tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drugs; adherence to their ARV medication regimen; types and frequency of sexual activity; condom use; and disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners. Examples of TACASI items include the following: In the last 6 months, have you used marijuana, also known as pot, hash, or cannabis?; Have you had sex in the past 6 months?; In the last 6 months, have you had another person’s penis in your anus without using a condom?

Study Population

Our analysis was limited to a cross-sectional convenience sample of HOPS patients surveyed via TACASI from March 2007 through July 2010. All analyses were conducted using the HOPS dataset updated as of September 30, 2010. TACASI is offered to all HOPS patients annually, if a patient completed multiple TACASIs, we analyzed the results of the first interview.

Variables

We analyzed behavioral and clinical factors associated with engaging in any type of unprotected anal sex (UAS) with a partner who was known to be HIV-negative or whose HIV status was unknown. The patients were queried about their sexual activity during the 6 months preceding the TACASI. We considered standard sexual risk factor variables,13,24,25 including alcohol and drug use, number of sexual partners, and HIV status disclosure, all of which were ascertained by TACASI. Data on current ARV use, CD4 count, and HIV VL were obtained through medical chart abstraction.

Statistical Analyses

We used logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) for the association of independent variables with any unprotected anal sex (either insertive or receptive) with partners of an unknown or HIV-negative serostatus. Statistical associations with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Factors that were significant in univariate analysis were included in a full multivariable logistic regression model; only factors that had significant associations were retained in the final model. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

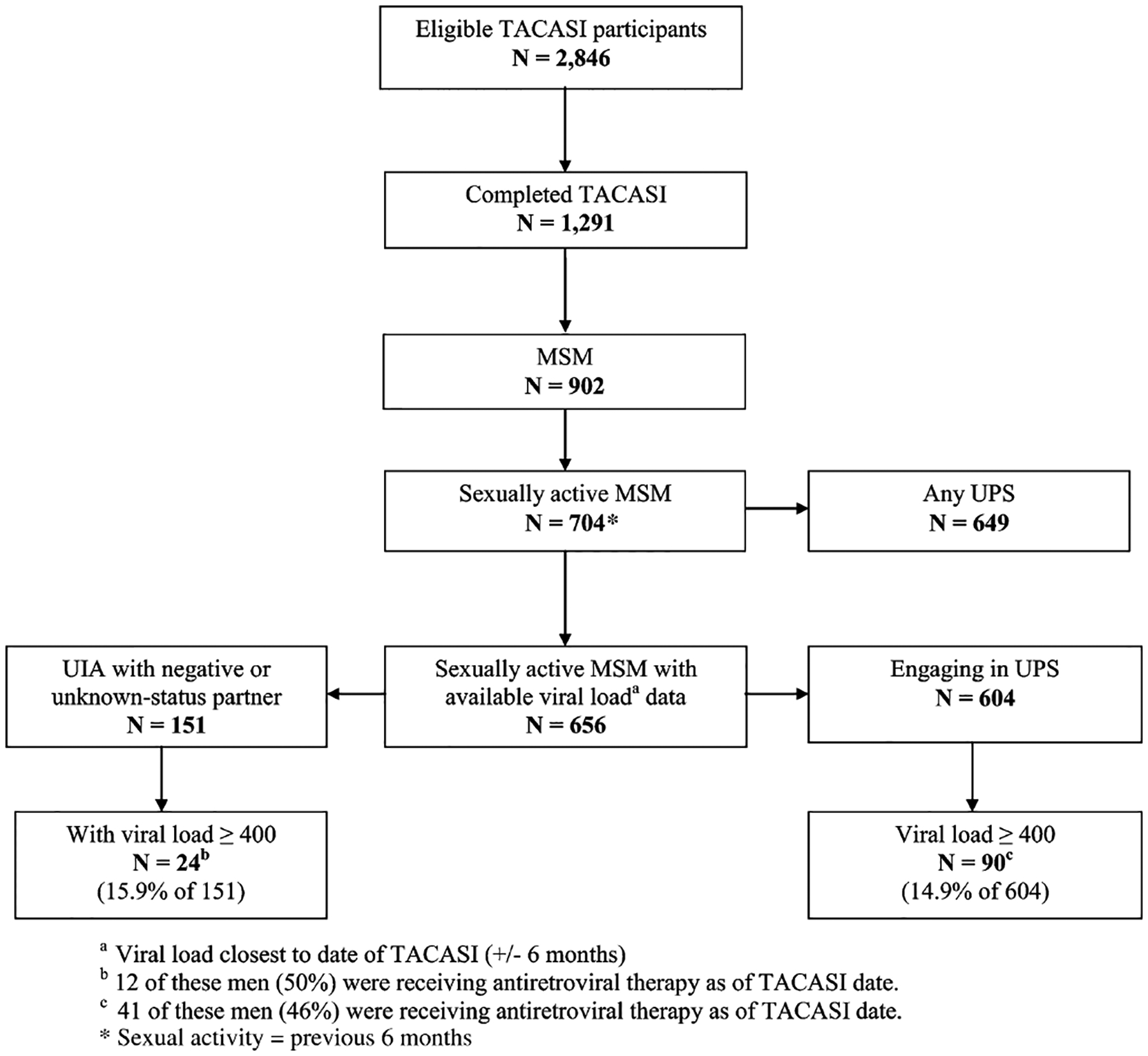

Among 2846 HOPS study patients eligible for the TACASI, 1291 (45%) completed the survey between March 2007 and July 2010 (Fig. 1). The median age of patients completing a TACASI was 46.9 years vs 45.1 years for those who did not complete the survey (P < 0.0001). TACASI completers were more likely to be non-Hispanic white: 66% compared with 30% for non-Hispanic black patients. College-educated patients (compared with less educated) and MSM (compared with all other HIV transmission risk groups) were more likely to complete the TACASI (P < 0.001 and P = 0.003, respectively). Men were no more likely than women were to complete the TACASI (P = 0.34).

FIGURE 1.

Stratification of eligible TACASI participants in the current analysis HOPS, United States, 2007–2010. MSM, men who have sex with men; TACASI, telephone audio computer assisted self-interview; UIA, unprotected insertive anal sex; UPS, unprotected oral, anal, and vaginal sex.

Median observation time in the HOPS for TACASI participants was 7.5 years. Survey respondents (N = 1291) had a median CD4 count of 513 cells per cubic millimeter and 94% were prescribed highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) as of the TACASI date. MSM comprised 70% of all TACASI completers (Fig. 1) and 75% (704/934) of completers who were sexually active (Table 1). The remaining results focus on the MSM survey respondents, and particularly the subset of MSM respondents who were sexually active in the past 6 months.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Sexually Active Patients Completing the First TACASI Survey, HOPS, United States, 2007–2010*

| Characteristics | All Patients (n = 934) | MSM (n = 704) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| ≤29 | 45 (4.8) | 31 (4.4) |

| 30–39 | 184 (19.7) | 133 (18.9) |

| 40–49 | 414 (44.3) | 302 (42.9) |

| ≥50 | 291 (31.2) | 238 (33.8) |

| Median age (IQR) | 45.5 (40.1, 51.9) | 45.8 (40.5, 52.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 644 (69.0) | 550 (78.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 184 (19.7) | 85 (12.1) |

| Hispanic | 84 (9.0) | 53 (7.5) |

| Other/unknown | 22 (2.4) | 16 (2.3) |

| IDU risk,† n (%) | 24 (2.6) | 18 (2.6) |

| Usual sex partners, n (%) | ||

| Men | 810 (86.9) | 672 (95.6) |

| Women | 84 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Both (men and women) | 38 (4.1) | 31 (4.4) |

| Not reported | 2 (—) | 1 (—) |

| Number of sex partners,† n (%) | ||

| 1 | 430 (46.0) | 240 (34.1) |

| 2 | 129 (13.8) | 110 (15.6) |

| ≥3 | 355 (38.0) | 336 (47.7) |

| Not reported | 20 (2.1) | 18 (2.6) |

| Recreational drug use,† n (%) | 547 (58.8) | 459 (65.5) |

| Alcohol use,‡ n (%) | 690 (74.6) | 564 (80.8) |

| Healthcare payer, n (%) | ||

| Private | 632 (67.7) | 560 (79.6) |

| Public/none | 302 (32.3) | 144 (20.5) |

| ARV exposure, n (%) | ||

| Any HAART | 882 (95.5) | 660 (94.7) |

| ARV not HAART | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) |

| Naive | 38 (4.1) | 33 (4.7) |

| Missing | 10 (—) | 7 (—) |

| CD4+ cell count, cells per cubic millimeter,§ n (%) | ||

| <200 | 71 (8.0) | 37 (5.6) |

| 200–349 | 148 (16.8) | 106 (15.9) |

| 350–499 | 178 (20.2) | 133 (20.0) |

| 500+ | 486 (55.0) | 390 (58.6) |

| Missing | 51 (—) | 38 (—) |

| Median (IQR) | 529 (351, 731) | 551 (378, 731) |

| Log10 plasma HIV RNA viral load§ (n = 656) | ||

| <3 | 753 (86.9) | 573 (81.4) |

| ≥3 | 114 (13.2) | 83 (11.8) |

| Median log10 viral load (IQR) | 1.7 (1.7, 1.8) | 1.7 (1.7, 1.7) |

| Missed any ARV dose in the past 3 d, n (%) | 154 (16.5) | 94 (13.5) |

| Disclosed HIV status, n (%) | ||

| No, to no partners | 87 (9.4) | 65 (9.2) |

| Yes, to some partners | 307 (33.1) | 238 (34.0) |

| Yes, to all partners | 533 (57.5) | 396 (56.7) |

| Data missing | 7 (—) | 5 (—) |

| HIV transmission risk group, n (%) | ||

| MSM | 704 (75.4) | |

| Heterosexual male | 62 (6.6) | |

| Woman | 128 (13.7) | |

| IDU | 40 (4.3) | |

| Mean survey duration in minutes (range) | 6.6 (4.0, 55.0) | 6.7 (4.0, 55.0) |

All variables measured as of TACASI date unless otherwise specified.

During the 6 months preceding TACASI.

During the 30 days preceding TACASI.

Closest to the date of TACASI (±6 mos).

IQR, interquartile ratio.

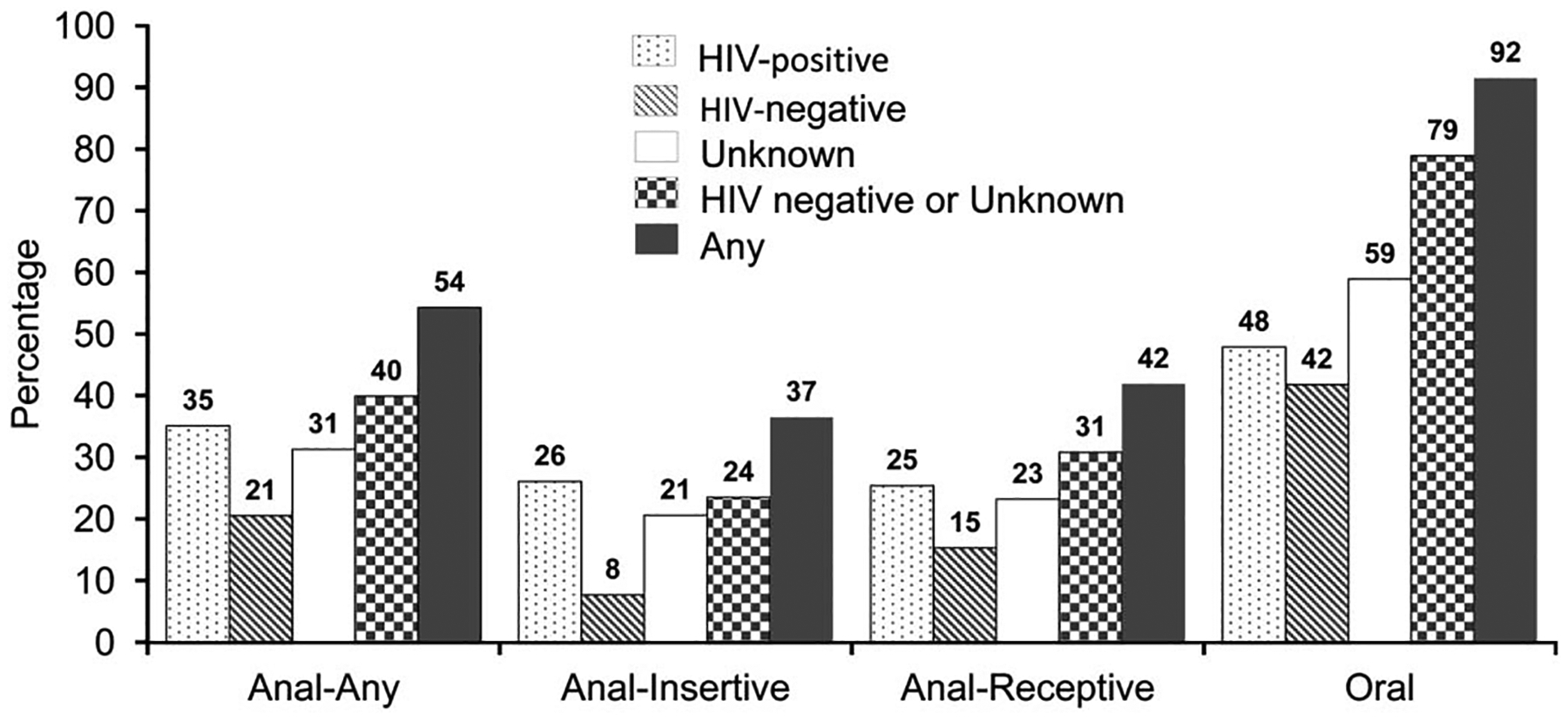

The 902 MSM surveyed by TACASI had a median age of 47 years, median CD4 count of 527 cells per cubic millimeter, 95% were prescribed HAART, and 78% (n = 704) reported having sex in the past 6 months. The characteristics of 704 sexually active MSM are detailed in Table 1. Among these 704 MSM, 649 (92%) reported engaging in any unprotected sex in the past 6 months: 54% reported any unprotected anal sex (37% as insertive partner, 42% as receptive partner), 92% reported any unprotected insertive or receptive oral sex, and 1% unprotected insertive vaginal sex (Fig. 2). Substantial fractions of these MSM engaged in unprotected anal sex with male partners who were HIV-negative (21%) or of unknown serostatus (31%): 24% practiced any unprotected anal sex as the insertive partner and 31% any anal sex as the receptive partner (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of unprotected sex in the past 6 months among sexually active HIV-positive MSM TACASI participants by partner serostatus, HOPS, United States, 2007–2010 (N = 704).

In multivariable analyses of sexually active MSM, engaging in any unprotected anal sex with an HIV-negative or unknown-status male partner within the past 6 months was associated with age <50 years [≤29 years adjusted OR (aOR) = 2.1, P = 0.07; 30–39 years aOR = 2.1, P = 0.002; 40–49 years aOR = 1.6, P = 0.018 compared with ≥50 years], injection drug use (IDU) risk (aOR = 4.7, P = 0.020), having >1 sexual partner (2 partners aOR = 2.4, P ≤ 0.001; ≥3 partners aOR = 5.5, P ≤ 0.001) and disclosing HIV status to only some but not all sexual partners (no partners aOR = 0.8, P = 0.34; some partners aOR = 1.6, P = 0.008; Table 2). Viral load level, ARV adherence, race/ethnicity, alcohol and IDU, CD4 count, HIV VL, and ARV experience were not associated with engaging in unprotected anal sex with HIV-negative or unknown-status male partners.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of Having Reported Engaging in Unprotected Insertive or Receptive Anal Sex With an HIV-Negative or Unknown-Status Male Partner in the Past 6 Months for HIV-Infected TACASI Participants Who Were MSM, HOPS, United States, 2007–2010 (N = 704)

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics* | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

| Age group, yrs | ||||||

| ≤29 | 2.4 | 1.1, 5.1 | 0.023 | 2.1 | 0.9, 4.8 | 0.07 |

| 30–39 | 2.3 | 1.5, 3.6 | <0.001 | 2.1 | 1.3, 3.5 | 0.002 |

| 40–49 | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.3 | 0.011 | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.4 | 0.018 |

| ≥50 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | 0.6, 1.6 | 0.92 | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | Referent | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.0 | 0.5, 2.0 | 0.97 | |||

| Other/unknown | 1.9 | 0.7, 5.7 | 0.23 | |||

| IDU risk† | ||||||

| Yes | 8.5 | 2.4, 29.3 | <0.001 | 4.7 | 1.3, 17.0 | 0.020 |

| No | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Number of sex partners† | ||||||

| 1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| 2 | 2.7 | 1.6, 4.5 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 1.4, 4.1 | 0.001 |

| ≥3 | 6.6 | 4.4, 9.9 | <0.001 | 5.5 | 3.7, 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Not reported | 3.1 | 1.1, 8.4 | 0.028 | 2.3 | 0.8, 6.6 | 0.11 |

| Recreational drug use† | ||||||

| Yes | 3.2 | 2.3, 4.5 | <0.001 | |||

| No | Referent | |||||

| Alcohol use‡ | ||||||

| Yes | 1.0 | 0.7, 1.5 | 0.97 | |||

| No | Referent | |||||

| ARV exposure | ||||||

| ARV-naive | 1.6 | 0.8, 3.3 | 0.17 | |||

| Any ARV exposure | Referent | |||||

| CD4+ cell count (cells per millimeter cube)§ | ||||||

| <200 | 0.8 | 0.4, 1.6 | 0.52 | |||

| ≥200 | Referent | |||||

| Log10 viral load (copies per milliliter)§ | ||||||

| <3 | Referent | |||||

| 3 to <4 | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.5 | 0.41 | |||

| 4 to <5 | 1.4 | 0.7, 2.7 | 0.36 | |||

| ≥5 | 1.0 | 0.3, 3.0 | 0.94 | |||

| Missed any ARV dose in the past 3 d | ||||||

| Yes | 1.2 | 0.8, 1.9 | 0.32 | |||

| No | Referent | |||||

| Disclosed serostatus | ||||||

| No, to no partners | 1.6 | 0.8, 3.3 | 0.17 | 0.8 | 0.4, 1.3 | 0.34 |

| Yes, to some partners | 2.3 | 1.6, 3.2 | <0.001 | 1.6 | 1.1, 2.4 | 0.008 |

| Yes, to all partners | Referent | |||||

All variables measured as of TACASI date unless otherwise specified.

During the 6 months preceding TACASI.

During the 30 days preceding TACASI.

Closest to the date of TACASI (±6 months).

CI, confidence interval.

In the analyses for a subset of 604 MSM who engaged in unprotected sex and also had proximally measured HIV VL available, 90 (14.9%) had a plasma HIV VL ≥400 copies per milliliter; only 41 of these men (46%) were receiving ARV therapy at the time of their TACASI. Sexually active MSM with viral loads <400 copies per milliliter did not differ from MSM with viral loads ≥400 copies per milliliter with respect to the frequency of unprotected sex behaviors, except for unprotected insertive oral sex with HIV-negative partners, which was less common among men with viral loads ≥400 copies per milliliter (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Percentage of Sexually Active MSM Engaging in Unprotected Sex in the Past 6 Months by Plasma HIV RNA Viral Load*, HOPS, United States, 2007–2010 (N = 604)

| Type of Unprotected Sex | VL < 400 Copies Per Milliliter N = 514 n (%)† | VL ≥ 400 Copies Per Milliliter N = 90 n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unprotected insertive anal sex with at least 1 partner who was | |||

| HIV-positive | 142 (27.6) | 27 (30.0) | 0.644 |

| HIV-negative | 45 (8.8) | 5 (5.6) | 0.310 |

| Unknown status | 110 (21.4) | 22 (24.4) | 0.519 |

| HIV-negative or unknown status | 127 (24.7) | 24 (26.7) | 0.692 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex with at least 1 partner who was | |||

| HIV-positive | 141 (27.4) | 27 (30.0) | 0.616 |

| HIV-negative | 85 (16.5) | 14 (15.6) | 0.817 |

| Unknown status | 131 (25.5) | 22 (24.4) | 0.833 |

| HIV-negative or unknown status | 173 (33.7) | 28 (31.1) | 0.636 |

| Unprotected insertive oral sex with at least 1 partner who was | |||

| HIV-positive | 269 (52.3) | 46 (51.1) | 0.830 |

| HIV-negative | 238 (46.3) | 30 (33.3) | 0.022 |

| Unknown status | 324 (63.0) | 59 (65.6) | 0.647 |

| HIV-negative or unknown status | 439 (85.4) | 74 (82.2) | 0.436 |

Measured in copies per milliliter closest to the date of TACASI (±6 months); the table includes the data for the subset of MSM (n = 604) with HIV viral load data available.

The number and percent of MSM patients engaging in a given practice out of the total in each column.

VL, plasma HIV RNA viral load.

DISCUSSION

Previously reported rates of unprotected anal sex among HIV-infected MSM in the United States have varied widely according to the methods and time frame used to capture the events.13,21,26,27 In the HOPS, the majority of HIV-infected MSM responding to an anonymous survey administered during 2007–2010 engaged in unprotected anal or oral sex placing them them and their partners at risk for HIV and STD infection. Indeed, in our cohort, 54% of MSM reported any unprotected anal sex in the past 6 months (35% with a male partner who was HIV-positive, 21% with a male partner who was HIV-negative, and 31% with a male partner of unknown serostatus). Our estimates are somewhat higher than those derived from a previous large meta-analysis among HIV-infected MSM in the United States, where overall 43% of MSM reported unprotected anal sex (in the prior 1–12 month timeframe): 30% with an HIV-positive, 16% with a male partner of unknown serostatus, and 13% with a male partner who was HIV-negative.20

Based on our analyses of a subset of MSM participants for whom risk behavior and viral load data were available, our findings also highlight the HIV transmission potential posed by the 15% of MSM who had unprotected sex and whose most proximal HIV VL was ≥400 copies per milliliter. Reassuringly, we observed no difference in the percentages engaging in high-risk anal sex by HIV VL (<400 vs ≥400 copies per milliliter). More than half of the MSM who practiced unsafe sex and had HIV VL ≥400 copies per milliliter were currently not receiving ARVs (Fig. 1, footnotes b and c), and these men would be potential candidates for initiating or resuming treatment for prevention of HIV transmission to sexual partners under the current US Department of Health and Human Services HIV treatment guidelines.10,27

Our findings are consistent with those from an earlier US meta-analysis that found that HIV-infected persons with undetectable viral loads were not more likely to engage in unprotected sex than HIV-infected persons with detectable viral loads.26 We identified several factors associated with unprotected insertive or receptive anal sex with HIV-negative or unknown-status male partners. HIV-infected MSM under the age of 50 years were more likely to engage in unprotected anal sex with an HIV-negative or unknown-status male partner than MSM who were aged 50 years and older. This difference may reflect a greater likelihood for older individuals to be in stable, monogamous partnerships (57% of MSM age ≥50 years were not sexually active or had a single sexual partner in the past 6 months compared with 47% of MSM age <50 years), a cohort-calendar effect (ie, survivors of the early phase of HIV epidemic in the United States may be more cautious than younger counterparts), or other factors that we did not measure. The trend toward increasingly less unprotected sex among HIV-infected MSM and other HIV-infected older persons has also been reported elsewhere.28,29

Injection drug users were also more likely to report unsafe sexual behaviors than were noninjection drug users. Injection drug users may have been more likely than nonusers to encounter situations (eg, impaired judgment from drug use, transactional sex) where they are unable to negotiate or assert safer sexual practices. Additionally, HIV-infected MSM with >1 sexual partner in the preceding 6 months and those who disclosed their HIV status to only some and not all of their sexual partners were more likely to engage in unprotected anal sex with an HIV-negative or unknown-status male partner. Although we do not have additional information to explain these results, it is plausible they reflect behaviors of MSM who meet multiple partners via the Internet or in sex venues where conversations regarding HIV serostatus may or may not take place.30–33

Our analysis had a number of limitations. The behavioral survey was collected from a convenience sample of volunteer respondents, which could have introduced 2 forms of bias. First, we may have underestimated or overestimated the percentage of HOPS patients (including MSM) who engaged in risky sexual behavior, as the persons who completed TACASI differed from those who did not complete the survey by a number of demographic characteristics (please see the Results section). Second, although ACASIs are considered to be among the most reliable methods for capturing complete and accurate data on sensitive behaviors, including unprotected sexual intercourse,34–37 underreporting bias of socially undesirable risk behaviors may have occurred, even though we tried to preclude this bias by assuring participants that their responses will not be shared with their treating clinicians. We do not have information about patients’ previous sexual partners beyond the total number and therefore are neither able to make distinctions between primary partners or casual partners, nor ascertain if these sexual partners were consecutive or concurrent. Additionally, among survey respondents with multiple partners, we do not know if these persons were encountered anonymously or if they were known individuals within the patients’ sexual networks. Due to the composition of the HOPS cohort, which tends to be primarily non-Hispanic white MSM, our findings may be less generalizable to the larger population of HIV-infected persons in the United States, particularly, those persons who are not engaged in routine care and who are persons of color. Finally, because we have so few ARV-naive study participants, we were not able to adequately ascertain if sexual risk behavior was associated with ARV experience.

Despite these limitations, a notable strength of our analysis was the capacity to link and jointly analyze risk behavior data and clinical data. We suggest that an area of fruitful investigation in studies where behavioral and clinical data are linked would be to assess the extent to which patients’ awareness of their HIV VL affects sexual behavior or survey responses about sexual behavior.

In summary, among HIV-infected MSM in care, we observed that over half engaged in unprotected anal sex in the preceding 6 months, especially MSM aged <50 years and MSM with multiple sexual partners; however, patients with elevated HIV VL were no more likely to potentially expose sexual partners to HIV than patients with HIV VL <400 copies per milliliter. Targeted interventions in the routine care of HIV-infected individuals can be effective in reducing the risk of secondary HIV transmission.38–40 Our findings support the current recommendations25,38,41 for HIV care providers to offer to their HIV-infected patients risk behavior screening, referrals to more intensive counseling as warranted, and ARV therapy for the prevention of sexual HIV transmission.27

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (contract nos. 200-2001-00133, 200-2006-18797, and 200-2011-41872).

APPENDIX 1. HIV OUTPATIENT STUDY INVESTIGATORS

The HOPS Investigators include the following persons and sites: John T. Brooks, Kate Buchacz, Marcus D. Durham, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHSTP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA; Kathleen C. Wood, Rose K. Baker, James T. Richardson, Darlene Hankerson, Rachel Debes, Carl Armon, Bonnie Dean, and Sam Bozzette, Cerner Corporation, Vienna, VA; Frank J. Palella, Joan S. Chmiel, Carolyn Studney, Onyinye Enyia, and Tiffany Murphy, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; Kenneth A. Lichtenstein and Cheryl Stewart, National Jewish Medical and Research Center Denver, CO; John Hammer, Kenneth S. Greenberg, Barbara Widick, and Joslyn D. Axinn, Rose Medical Center, Denver, CO; Bienvenido G. Yangco and Kalliope Halkias, Infectious Disease Research Institute, Tampa, FL; Doug Ward, Troy Thomas, and Rob Grant, Dupont Circle Physicians Group, Washington, DC; Jack Fuhrer, Linda Ording-Bauer, Rita Kelly, and Jane Esteves, State University of New York (SUNY), Stonybrook, NY; Ellen M. Tedaldi, Ramona A. Christian, Faye Ruley, Dania Beadle and Princess Graham, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA; Richard M. Novak and Andrea Wendrow and Renata Smith, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; Benjamin Young, Barbara Widick, Joslyn Axinn, APEX Family Medicine, Denver, CO.

Footnotes

The HOPS Investigators are given in Appendix 1.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. HIV and AIDS in the United States. 2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm. Accessed August 23, 2010.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57: 1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prejean J, Song RG, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLos One. 2011;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. AIDS. 2012;26:893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin FY, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, et al. High rates of sexually transmitted infections in HIV positive homosexual men: data from two community based cohorts. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:397–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus U, Schmidt AJ, Hamouda O. HIV serosorting among HIV-positive men who have sex with men is associated with increased self-reported incidence of bacterial sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2011; 8:184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell MS, Gottlieb GS, Hawes SE, et al. HIV-1 superinfection in the antiretroviral therapy era: are seroconcordant sexual partners at risk? PLoS One. 2009;4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell RLR, Urbanski MM, Burda S, et al. High frequency of HIV-1 dual infections among HIV-positive individuals in Cameroon, West Central Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redd AD, Mullis CE, Serwadda D, et al. The rates of HIV superinfection and primary HIV incidence in a general population in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph HA, Flores SA, Parsons JT, et al. Beliefs about transmission risk and vulnerability, treatment adherence, and sexual risk behavior among a sample of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2010;22:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen SY, Gibson S, Katz MH, et al. Continuing increases in sexual risk behavior and sexually transmitted diseases among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, CA, 1999–2001. Am J Public Health. 2002;92: 1387–1388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reilly T, Woodruff SI, Smith L, et al. Unsafe sex among HIV positive individuals: cross-sectional and prospective predictors. J Community Health. 2010;35:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatesh KK, Srikrishnan AK, Safren SA, et al. Sexual risk behaviors among HIV-infected South Indian couples in the HAART era: implications for reproductive health and HIV care delivery. AIDS Care. 2011;23:722–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Hirschel B, et al. Frequency and determinants of unprotected sex among HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crepaz N, Marks G, Liau A, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-diagnosed MSM in the United States: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1617–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox J, Beauchemin J, Allard R. HIV status of sexual partners is more important than antiretroviral treatment related perceptions for risk taking by HIV positive MSM in Montreal, Canada. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:518–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the internet. AIDS Care. 2003;15:367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moorman AC, Holmberg SD, Marlowe SI, et al. Changing conditions and treatments in a dynamic cohort of ambulatory HIV patients: the HIV outpatient study (HOPS). Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackers ML, Greenberg AE, Lin CY, et al. High and persistent HIV seroincidence in men who have sex with men across 47 US cities. PLos One. 2012;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.HRSA. Preventing HIV Transmission/Prevention with Positives. Guide for HIV/AIDS Clinical Care. 2011. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliverhivaidscare/clinicalguide11/. Accessed September 25, 2012.

- 26.Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior—a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292:224–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. Available at: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Messinger S, et al. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf K, Young J, Rickenbach M, et al. Prevalence of unsafe sexual behavior among HIV-infected individuals: the Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grov C HIV risk and substance use in men who have sex with men surveyed in bathhouses, bars/clubs, and on Craigslist.org: venue of recruitment matters. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland S, et al. “It’s a quick way to get what you Want”: a formative exploration of HIV risk among urban Massachusetts men who have sex with men who attend sex parties. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:659–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thiede H, Jenkins RA, Carey JW, et al. Determinants of recent HIV infection among Seattle-area men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:S157–S164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golub SA, Tomassilli JC, Parsons JT. Partner serostatus and disclosure stigma: implications for physical and mental health outcomes among HIV-positive adults. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1233–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarroel MA, Turner CF, Rogers SM, et al. T-ACASI reduces bias in STD measurements: the National STD and Behavior Measurement Experiment. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gribble JN, Miller HG, Cooley PC, et al. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35:869–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner CF, Al-Tayyib A, Rogers SM, et al. Improving epidemiological surveys of sexual behaviour conducted by telephone. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1118–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schackman BR, Dastur Z, Rubin DS, et al. Feasibility of using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) screening in routine HIV care. AIDS Care. 2009;21:992–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aral S, Dooley SW, Kamb ML, et al. Recommendations for incorporating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:104–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher JD, Smith LR, Lenz EM. Secondary prevention of HIV in the United States: past, current, and future perspectives. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:S106–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stall R Efforts to prevent HIV infection that target people living with HIV/AIDS: what works? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:S308–S312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease C, Prevention, Health R, Services A, National Institutes of H, America HIVMAotIDSo. Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]