Abstract

Within the field of applied behavior analysis, there is a recognized need for increased training for practitioners on cultural responsiveness, as well as to improve behavior analysts’ demonstration of compassion and empathy towards the families with whom they work. The present study used behavioral skills training via telehealth to teach three skillsets—functional assessment interviewing, empathic and compassionate care, and cultural responsiveness. Participants were seven graduate students who had no previous coursework in behavioral assessment and whose caseload mainly included clients who did not share the participant’s cultural, ethnic, or religious backgrounds. The results showed that behavioral skills training was effective in improving performance across all three skillsets. In addition, high levels of responding maintained following the completion of the training for the majority of the participants. Several levels of social validity measures support the utility and impact of this training. The findings have implications for training practitioners on these vital skills.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Behavioral skills training, Cultural responsiveness, Functional assessment interviewing, Empathic and compassionate care

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by 2030, over 50% of Americans are anticipated to be a from racial and ethnics groups aside from those identifying as non-Hispanic white only, and almost 20% of the United States’s population is expected to have been born outside of the country (Colby & Ortman, 2015). As the demographics change, so will the population of the students and clients that behavior analysts serve in the United States. As a result, addressing how this may affect behavior analytic services is growing in importance. According to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board ([BACB], 2022), as of January 28, 2022, 70.05% of BCBAs and BCBA-Ds who reported their race and ethnicity identify as white and 86.42% identify as female. Although data regarding the demographics of clients receiving services from BCBAs and BCBA-Ds is not currently available from the BACB, it is likely that they are similar to those seen in education service contexts.

Moreno and Gaytán (2013) warned about the potential effects of the disparities between the demographics of educators and the students they teach. What can result is a “diversity rift” that can lead to the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of the students not being “incorporated into the planning and delivery of instruction and the implementation of behavioral supports” (Moreno & Gaytán, 2013, p. 89). In particular, Moreno and Gaytán (2013) highlighted potential resulting barriers for Latino students in two specific areas—the ways in which school disciplinary practices are implemented differently across students of various races and ethnicities and the overrepresentation of the students in referrals for special education services and within the category of emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD). Moreno et al. (2014) further stated that research has shown that African American and Latino students, in particular, “experience significantly poorer discipline and academic outcomes in the U.S. public school system than their white peers” (p. 346). One of the ways in which Moreno and Gaytán (2013) recommended addressing these biases included using functional behavioral assessments (FBAs) as a preventive measure to increase the likelihood that the students will receive appropriate behavioral interventions and supports, while also matching the unique cultural needs of the children served.

Cultural Responsiveness

Culture has been defined by Sugai et al. (2012) as the reflection of “a collection of common verbal and overt behaviors that are learned and maintained by a set of similar social and environmental contingences (i.e., learning history), and are occasioned (or not) by actions and objects (i.e., stimuli) that define a given setting or context” (p. 200). This can encompass different beliefs, norms, and customs, as well as verbal and nonverbal behavior. Sugai et al. stated that although cultural variables are hard to define and measure, they must be considered within specifically within the context of behavioral supports. Friman et al. (1998) made a similar argument regarding the behavior analytic study of emotions such as anxiety, stating that “imprecision of a term . . . is not a sufficient justification for such avoidance when the phenomenon to which it refers is so vast and so central to the psychology of human beings” (p. 153).

Gay (2002) described providing culturally responsive teaching as “using [students’] cultural orientations, background experiences, and ethnic identities as conduits to facilitate their teaching and learning” (p. 614). In recent years, there has been an increased call to action for behavior analysts to increase the incorporation of cultural responsiveness within practice (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Conners et al., 2019; Hughes Fong & Tanaka, 2013). Existing literature has suggested improving educational and professional development opportunities, dedicating time and resources to improving practices, forming relationships with individuals from other backgrounds, learning about one’s own culture through self-assessment and self-reflection, increasing the opportunities for obtain mentorship particularly for minorities, increasing and supporting minority faculty, and evaluating progress towards goals (Hughes Fong et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2019; Wright, 2019). Despite the agreed upon need for improvement in this area as a field, there is currently limited guidance for behavior analysts on how to achieve this goal. Available resources are largely conceptual in nature, with a few exceptions of experimental applications (e.g., Buzhardt et al., 2016; Neely et al., 2020).

Additional challenges have included limited and, at times, incongruent guidance from Ethics Code (BACB, 2020), previously referred to as the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2019; Beirne & Sadavoy, 2019; Brodhead, 2019; Rosenberg & Schwartz, 2019; Witts et al., 2020), a lack of specific coursework or continuing education to specifically address this area (BACB, 2012a), the lack of inclusion of these areas within the Task Lists (BACB, 2012b; BACB, 2017), the lack of training and educational opportunities within graduate school and fieldwork supervision (Conners et al., 2019), and a mismatch between behavior analysts’ self-assessment of their delivery of culturally competent care and feedback received from parents whose children received ABA services (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2019).

Empathic and Compassionate Care

Several human service fields have emphasized the importance of compassionate care. Coulehan et al. (2001) emphasized the importance of empathy to the clinician–patient relationship within the context of medical practice. The authors discussed various aspects of clinical empathy including: the demonstration of active listening, nodding and using minimal expression; framing or sign posting (e.g., “Let’s see if I have this right. . . . Sounds like what you’re telling me is. . . . Sounds like. . . .”) (p. 222); reflecting the content that includes summarizing information provided by the patient; responding to the patient’s feelings and emotions; and requesting/accepting feedback and correction from the patient.

LeBlanc et al. (2020) found that the majority of BCaBAs, BCBAs, and BCBA-Ds indicated a lack of university training and training during practicum or supervision on compassion, empathy, and developing therapeutic relationships with families. In addition, behavior analysts tended to agree that they sometimes feel unprepared to manage the emotional responses of others. Moreover, Taylor et al. (2019) found that although behavior analysts seem to reliably demonstrate some of the skills needed for a strong therapeutic relationship, there is room for improvement according to families of children receiving ABA services. For example, 27.37% of parents did not agree that their behavior analyst was “compassionate and nonjudgmental” nor that they “acknowledge[d] [their] feelings when discussing difficult or challenging circumstances” (p. 657). The authors identified core components that should be addressed, which include “active listening, collaborating with caregivers, understanding a family’s culture, being kind, asking open-ended questions, avoiding technical jargon, and caring for the entire family” (p. 660), similar to the skills identified by Coulehan et al. (2001).

Functional Assessment

Functional assessments are a critical area in which behavior analysts should embed culturally responsive practices, as the functional assessment of behavior is critical to the treatment process (e.g., Carr & Durand, 1985). Several notable studies have been conducted on training functional assessment interviewing skills (e.g., Iwata et al., 1982; Miltenberger & Fuqua, 1985; Miltenberger & Veltum, 1988). These studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of training clinical interviewing skills utilizing various training components (e.g., modeling, rehearsal, and feedback). These elements of training form the foundations of what is now referred to as behavioral skills training (BST; Parsons et al., 2012; Parsons et al., 2013). Although these studies provided insight on how to effectively train functional assessment interviewing skills, they did not include several key components of the interview process, particularly related to interviewing families from a variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, as well as conveying empathy and compassion.

Salend and Taylor (2002) provided guidelines on conducting a culturally sensitive FBA process, including the importance of gathering information from various sources regarding the student (e.g. areas of strength and needs, preferences, and health), as well as the behavior of interest and considerations for the family’s culture and language background. Furthermore, the authors provided recommendations for obtaining assessment data (e.g., obtaining information regarding potential antecedents and consequences, what the student may be attempting to communicate when they are engaging in the target behavior, what reinforcement they might be accessing following the behavior, any relevant setting events or medical contributions, and whether the student’s behavior serves a purpose within their culture).

Hughes Fong and Tanaka (2013) highlighted the lack of concrete standards within the field of behavior analysis for ensuring culturally competent service delivery, including aspects of the assessment process. The authors provided recommendations for the assessment and treatment processes such as: taking the language of the assessment into consideration (including whether an interpreter is needed), not using technical jargon and communicating in an easily understandable manner, using appropriate forms of eye contact, nonverbal communication, and other related factors, all which may vary from culture to culture; considering and understanding the cultural identity of the client and their family including cultural norms and how that relates to recommending goals and treatment approaches; using available resources, when relevant, including ones outside of our field.

Moreno and Gaytán (2013) recommend considering the languages in which the family feels comfortable completing an interview, as well as having an educator who is fluent in the same language as the family’s primary language, if possible. In addition, the ethnic background and specific culture of the family should be considered. For example, if a family’s primary language is Spanish and they are from Ecuador, the questions should be provided in Spanish and they should be reflective of the Ecuadorian culture. The authors also provided a sample Parent Functional Interview form with open-ended prompts that ask about the family’s perspective regarding behaviors of interest, parenting roles and styles, and other cultural contingencies of interest. Such questions may promote collaboration between the family and the educators, remove judgement, and allow for the family to offer their own perspective and suggestions.

Behavioral Skills Training

Behavioral skills training (BST) is an evidence-based approach to training which is commonly used within the field of ABA to teach a wide variety of skills (Parsons et al., 2012). Although some variability exists in the literature, Parsons et al. listed six steps that are typically included within BST: providing instructions including a rationale and an operational definition of the skill; providing a clear written description; demonstrating or modeling the skill; requiring the trainee to practice or roleplay the skill; providing performance feedback during the rehearsal; and repeating the practice and feedback until the skill is mastered. Additional components may include providing specific example and nonexamples, providing the trainee with a written summary of the target steps, data collection, and on-the-job training (Parsons et al., 2012; Parsons et al., 2013).

Analyses have been conducted in order to identify the most effective components of BST. According to Ward-Horner and Sturmey (2012), feedback and modeling may be the most effective. This is consistent with the findings of Miltenberger and Veltum (1988) who found instructions alone to be overall ineffective in teaching interviewing skills and saw substantial improvement once modeling and feedback were added. Canon and Gould (2022) utilized verbal instructions and role-play along with clicker training to effectively increase relationship-building skills for two ABA practitioners, further indicating that components of BST may be effective in improving compassionate care skills. For the purpose of the present study, each of the main components outlined by Parsons et al. (2012) will be included in the training. Additional components will be included to test for the maintenance and generalization of the taught skills.

Present Study

There is agreement among behavior analysts regarding the importance of increasing the cultural responsiveness, compassion, and empathy skills of behavior analytic practitioners. In addition, Taylor et al. (2019) recently found that parents of children receiving ABA services have reported some dissatisfaction regarding the care they have received from their behavior analyst. This improvement is needed in all areas of clinical care, including within the context of assessing challenging behaviors and interviewing caregivers. Despite the identified need, little experimental research and training opportunities are currently available. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a training package to teach culturally responsive and compassion-based functional assessment interview strategies to behavior analysts-in-training. The target skills selected were directly based on the existing literature on empathic and compassionate care and cultural responsiveness (Coulehan et al., 2001; Hughes Fong & Tanaka, 2013; Moreno & Gaytán, 2013; Salend & Taylor, 2002; Taylor et al., 2019). These skills were taught with BST via telehealth (Nickelson, 1998; Tomlinson et al., 2018).

Method

Setting

The study was conducted on Zoom, an online videoconferencing service. Each session occurred within a virtual meeting with video and audio turned on. Only the experimenter and the participant were present during each session (with the exception of the generalization phase). Both individuals were physically located in a quiet location such as an office. Communication also occurred virtually through email or announcements on Canvas, a learning management system that was utilized regularly by the participants as part of their graduate school learning platform.

Participants

Participants were graduate students completing VCS coursework towards a master’s in ABA (n = 6) or a post-master’s certificate in ABA (n = 1) at a college in the northeast United States. They were enrolled in at least one ABA course at the onset of the study. Students were recruited through an online Canvas announcement with a description of the study, as well as information about the opportunity for extra credit points towards coursework upon study completion. Students were excluded if they were currently enrolled in or had previously taken a behavioral assessment course. Students were also excluded if their schedule was not compatible with the experimenter during the proposed time frame of the study.

Students who had availability to participate in the study were sent a questionnaire on Qualtrics, an online survey platform. The survey obtained information regarding demographics, as well as previous training and experience with behavioral assessment, interviewing, and providing services to individuals from various cultural, racial, ethnic, religious, and/or spiritual backgrounds. Eight out of 19 respondents were then selected as participants based on their self-reports that more than half of their “clients come from racial, ethnic, religious, and/or spiritual backgrounds that are different than [their] own.” The experimenter anticipated that that skills taught would be the most relevant to this group. The remaining students were exposed to a modified version of the content in a later required course within the program. At the onset of the study, one participant was withdrawn from the study due to scheduling issues. Seven participants eventually completed the study. The summary of participant demographics is located in Table 1, whereas their professional experience is summarized in Table 2. In addition, according to self-report data, the participants varied widely in their experience and training across functional assessment procedures, interviewing skills, and working with individuals from different backgrounds; however, none of the participants had significant training or coursework in these areas.

Table 1.

Summary of responses regarding demographics

| Question | Responses (Number of Participants out of 7 total) |

|---|---|

| Sex and gender (open-ended) |

Female (5) Male (2) |

| Age |

20–24 (2) 25–29 (2) 30–34 (1) 45–49 (1) 50–54 (1) |

| Races and ethnicities (open-ended) |

White (3) African American (1) Asian/Chinese (1) White/Hispanic (1) White/Hispanic and Native American (1) |

| Languages Spoken | English only (5), English and Swahili (1), English and Cantonese (1) |

| Miscellaneous | All resided within United States; at least one born outside of the United States |

Table 2.

Summary of responses regarding professional experience

| Question | Responses (Number of Participants out of 7 total); Ranges and Means |

|---|---|

| Certification |

Registered behavior technician (RBT™) (5) Non-certified (2) |

| Years worked in ABA | Ranged from 0.75 to 4.1 years (M = 2.1) |

| Years worked with individuals with ASD or other developmental disabilities | Ranged from 0.75 to 9 years (M = 2.9) |

| Years worked in related fields | 0.0 to 9 years (M = 2.6) |

| Additional information | One participant was parent of child who had been receiving ABA services for approximately 9 years |

Materials

A laptop with Microsoft PowerPoint was utilized for presentations across all phases of the study, with the exception of the generalization probes. Meetings and video/audio recording were conducted through Zoom. Datasheets were created for measurement of target skills, interobserver agreement, procedural integrity, and expert evaluations. Additional forms included various consent forms and two social validity questionnaires—one filled out by the participants following the completion of the study and the other by the parents who participated in the generalization phase.

The experimenter also created a form to obtain information regarding ten hypothetical clients who would be used in examples throughout the study during the roleplay interviews. Several individuals from within the field of ABA who were from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds and races filled out the form, in addition to the experimenter filling out two of the forms herself. These individuals developed the hypothetical information loosely based on their own cultural and ethnic backgrounds. The individuals who created the hypothetical clients provided the following descriptions of them: Black Hispanic/Catholic from Dominican Republic; Filipino and white/Catholic; Filipino/Catholic; Greek/Greek Orthodox; Russian/Jewish; Arab/Muslim from United Arab Emirates; white Brazilian/Evangelical; Egyptian Ecuadorian Coptic Orthodox/Catholic; Mexican/Jewish and Catholic; and Puerto Rican.

The information obtained regarding the hypothetical clients included answers to possible questions regarding information such as (but not limited to) the interviewee’s preferred language, their primary concern of their child, any diagnoses or medical conditions, the role that their culture plays in their child’s life, the roles of other people in their child’s life, and various questions that are important for the functional assessment of behavior such as the onset of the behavior and common antecedents and consequences. Basic information including the hypothetical client’s name, sex, and gender, and reasons for seeking help were shared in a written and oral format with the participant prior to each interview; however, any additional information such as common parental reactions to the behaviors of concern was only stated if the study participant asked for this information during the interview.

Experimental Design

A multiple-baseline design (Baer et al., 1968) across skillsets was utilized to examine the effects of BST on the use of various skills during roleplay interviews. The three sets included skills across the following areas: functional assessment interviewing, cultural responsiveness, and empathic and compassionate care. The order of the skill sets taught was decided individually for each participant based on their data (e.g., depending on the most stable rates of responding across the three skills sets; Kazdin, 2011). Maintenance probes were conducted posttraining for six out of the seven participants. For one those participants, a booster BST session was conducted after one of the maintenance probes due to a substantial decrease in responding for one skillset during maintenance. This resulted in an unintended reversal design for one of the skillsets. Lastly, for two participants, a generalization probe was also conducted following the completion of the study. One participant did not meet criteria for a maintenance probe. For generalization, only two families were available for mock interviews; therefore, only two study participants completed this phase.

Measurement

The primary measure was the percentage of skills correctly demonstrated across each given skillset during roleplay interviews. The skills that were chosen for each skill set were based on skills identified within the existing literature as being important for each of these areas; skills that would be difficult to address within a videoconferencing format (e.g., eye contact) were excluded. A summary of the skills in each skillset is described in Table 3. Operational definitions, as well as examples and nonexamples, appear in Appendix 1. Scoring for each individual skillset is described in subsequent paragraphs.

Table 3.

Summary of skills per skillset

| Assessment | Cultural Considerations | Empathy, and Compassion |

|---|---|---|

|

- Conducting record review - Inquiring about communication skills - Identifying preferences/potential reinforcers - Identifying caregiver concerns/priorities - Asking regarding onset of target behavior - Asking regarding measurable dimensions of target behavior - Obtaining description of antecedents, behavior, and consequences (ABC) - Inquiring about previous or current treatments - Asking interviewee regarding opinions on cause - Refraining from suggesting specific treatments |

- Identifying preferred language - Arranging for an interpreter (if needed) - Conducting analysis of cultural identity - Refraining from using technical jargon - Refraining from using idioms and expressions - Refraining from using offensive words or statements - Asking clarifying questions - Refraining from making assumptions regarding values - Identifying roles of family members and others |

- Nodding and using minimal expression - Refraining from interrupting - Using empathic statements - Summarizing information provided by interviewee - Requesting feedback and correction - Responding to feedback from interviewee |

Functional Assessment Interviewing

Sixteen target skills were taught which are listed in Table 3. Each skill was scored as a plus (+) if it was demonstrated correctly during the roleplay interview and a minus (–) if it was demonstrated incorrectly or not demonstrated at all during the interview. The number of correct responses were then divided by the number of correct and incorrect responses and multiplied by 100 to obtain the percentage of correct responding.

Empathic and Compassionate Care

Six skills were identified and taught (see Table 3). The data collection in this skillset was slightly different from the previous skillset due to the nature of the behaviors targeted. For example, if the behavior only needed to be demonstrated at least once during a 1-min interval (e.g., nodding and using minimal expressions), partial interval recording was used where a plus (+) indicated that the behavior occurred during the interval and a minus (–) indicated that it did not. If the skill needed to be demonstrated during the entire interval (e.g., refraining from interrupting while the other person is speaking), whole interval recording was used, and a plus (+) indicated that the behavior occurred throughout the interval, whereas a minus (–) indicated that it did not. The score for these skills was calculated by dividing the number of intervals with correct responding out of the total number of 1-min intervals. If the interview ended with an interval shorter than 1 min in duration, that interval was excluded from the scoring. Several other skills (e.g., delivering empathic statements, summarizing information provided by the interviewee, and asking for feedback/correction) were required to be demonstrated at least once during the interview. These were marked as a plus (+) if the participant demonstrated the skill at least one during the entire call. A minus (–) was recorded if the skill was never demonstrated during the call. Scoring for the final skill (reacting when the interviewer is corrected by the interviewee) was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses out of the total number of opportunities (instances in which the interviewer was corrected). The number of points across all six skills were added and then divided by the total number of points available.

Cultural Responsiveness

Nine target skills were taught (see Table 3). Scoring was completed as described above for assessment skills.

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was conducted using a trial-by-trial IOA method for 33% of interviews across baseline, training, and maintenance. Total number of agreements were divided by the sum of agreements and disagreements and then multiplied by 100 to obtain the IOA score. For each session, IOA was conducted for agreement across all 31 steps for each interview, as well as across each skill area. The mean and range of scores were also calculated across all sessions and each skill area. This allowed for additional analysis regarding which skill areas had the overall lowest and highest IOA results, as well as the greatest range in agreement, as well as giving information regarding which areas may require additional refinement of definitions. IOA was conducted by two PhD-level students who were trained individually by the experimenter prior to scoring videos. Both observers were required to demonstrate at least 80% IOA using trial-by-trial IOA scoring with the experimenter upon to the completion of training.

Overall trial-by-trial IOA was 86.9%, ranging from 71% to 99.6% across the 19 videos. Average agreement for functional assessment interviewing was the highest out of the three skillsets at 89.8%, ranging from 75% to 100%. On average, agreement for empathic and compassionate care, as well as cultural responsiveness, was slightly lower, as well as more variable. IOA for empathic and compassionate care was 84.3% on average, ranging from 45.8% to 100% agreement. For cultural responsiveness, the IOA was 83.6%, ranging from 55.6% to 100% agreement. Further analysis of the disagreements was completed when the IOA was lower than 80%. Skills that were most typically disagreed on included: refraining from using words, phrases, statements that may be offensive; refraining from using terminology/phrases that may be confusing or culturally irrelevant such as idioms/expressions that are specific to the interviewer’s culture; refraining from making assumptions about the acceptability and/or importance of targeting the given behavior (unless the behavior poses a clear risk/injury to self or others and ethically must be addressed); empathy and compassion skills. This information was used to inform which skills may need to be further clarified defined.

Procedural Integrity

Procedural integrity (PI) data were taken for 33% of interviews across baseline, training, and maintenance phases. PI data were taken by two additional PhD-level students who were trained together prior to scoring videos. Both observers were required to demonstrate at least 80% IOA using trial-by-trial IOA scoring with the experimenter upon to the completion of training. Data were typically taken with either a plus (+) for a correct response and a minus (–) for an incorrect response. For elements that were scored on minute-by-minute performance, data were recorded in 1-min-long intervals based on whether the criteria were met during each interval (e.g., refraining from prompting the participant during a given interval). PI data were calculated by dividing the total number of training steps completed correctly by the sum of the steps completed correctly and incorrectly and then multiplying the result by 100.

The procedural integrity across baseline, training, and maintenance videos, as well as the roleplay interview videos, averaged at 98.6%, ranging from 85.7% to 100% per video. PI for roleplay interview videos only was 99.1% (range: 85.7%–100%). PI for the baseline, training, and maintenance videos was 97.6% (range: 92.8%–100%). Across all the videos assessed, 895 out of 915 trainer steps were completed correctly resulting in high levels of procedural integrity throughout all phases of the study.

Procedures

Baseline

Prior to the start of the study, each participant signed a consent form. The experimenter arranged a time to meet 1:1 with each participant via Zoom. The first Zoom meeting consisted of building rapport, introductions, answering any questions or concerns regarding the consent form, discussing logistics, and asking if the participant had any questions or concerns regarding the technology required for the study. Once the general information was reviewed and any participant questions were answered, the baseline phase began.

The experimenter explained that the participant would be in the role of the clinician who is interviewing a caregiver for the first time regarding their reasons for seeking help and their concerns regarding their child’s challenging behavior. General information about the hypothetical student was presented on the screen through the screensharing option on Zoom. This information included the following: name, age, sex/gender, diagnosis, setting/place of service, and reason for seeking help (e.g., “behaviors hard to manage”). In addition, there was a written prompt that said, “Prior to attending the interview, are there any steps you would take?,” which was also orally asked to the participant prior to beginning the roleplay interview. During each roleplay interview for each participant, a different hypothetical case was used. The order of the hypothetical cases was randomized using Random.org.

Once the roleplay interview began, feedback and prompting were not provided regarding target responses during the interview. Only questions regarding logistics were answered (e.g., if something within the directions became unclear once the interview started). Three baseline sessions occurred during the first Zoom meeting with each participant. At the end of the interview, the participant was asked if they had any general questions. If the participants asked for feedback about their performance, they were told that feedback would be provided during the training portion of the study. Interviews were video recorded through Zoom to allow for data collection of the primary measures, interobserver agreement, procedural integrity, and for evaluations of social validity. The principal investigator recorded data on the primary measures after each meeting from the video recording. Prior to continuing to the training phase, each video was scored. Based on an analysis of the baseline data, the experimenter selected the first target skillset.

Behavioral Skills Training

BST was utilized throughout the intervention phase. First, a separate PowerPoint training was created for each skillset. For each target skill, the experimenter delivered oral and written instructions regarding the skill in terms of its definition, description, examples, and nonexamples. Next, the experimenter provided in vivo modeling of the skill, unless the skill was already modeled as part of the example that was provided. The experimenter modeled both vocal verbal behavior (e.g., “one way you can ask about communication skills is. . . .” and then demonstrated the example listed above) and nonvocal verbal behavior such as nodding your head throughout the interview to demonstrate active listening. Following modeling, the participant rehearsed the target skill as though they were a behavior analyst, and the experimenter took the role of a parent or caregiver. For example, the experimenter might have said, “Now, you can play the role of the behavior analyst, and I will be Peter’s mom. Show me how you would ask me about what typically seems to occur prior to when Peter begins to hit his head with his fist.” The experimenter then delivered performance feedback regarding what the participant did correctly and incorrectly during the rehearsal. If an error occurred during the roleplay, the participant was given feedback and then immediately asked to perform the skill again. This sequence continued until the participant correctly performed the given target skill once without any prompting or correction.

Once all of the skills in the skillset were successfully demonstrated correctly, the experimenter and the participant reviewed a summarized list of the target skills in the skillset. The experimenter answered questions and provided clarification regarding the target skills, if applicable. Once the participant confirmed that they had no more questions, a full roleplay interview was conducted in the same manner as the interviews that occurred during baseline; however, only one interview occurred rather than three. The duration of each training was recorded in order to calculate the total training time for each participant.

Following the initial BST training for each given skillset, a review of the skillset was conducted at the start of the next session. In other words, if the initial BST training was conducted for empathic and compassionate care during Session 4, the experimenter briefly reviewed the skills for that skillset at the start of Session 5 prior to introducing a new skillset. During the review, the experimenter delivered feedback on which steps were demonstrated correctly and incorrectly during the roleplay interview at the end of the previous session. For the skills that were correctly demonstrated, the experimenter delivered praise. For the skills that were incorrectly demonstrated or were not demonstrated at all during the previous roleplay interview, the experimenter delivered corrective feedback and then followed each of the steps for BST for that specific skill until correct responding was demonstrated.

The timing of the introduction of BST for each skillset was determined individually based on a variety of factors. First, the experimenter visually analyzed the baseline data for each participant to determine which skillset had the most stable data during baseline, unless the baseline data for that given skillset were showing an increasing trend. In those cases, the experimenter then looked for the next most stable baseline data. Once each participant was taught the first skillset (demonstrated at least 80% correct responding), the experimenter determined which skillset to teach next and when. The same individualized approach was followed for the introduction of training for the third skillset, as well as for the maintenance probes. If an increasing trend persisted during baseline for the third skillset, additional baseline sessions were conducted until responding stabilized.

Maintenance

Maintenance was conducted once mastery was attained within a given skillset and was subject to the participants’ availability. During maintenance, no prompting or feedback was given, and the summary of skills was not reviewed prior to the roleplay interview. During a given session, maintenance was at times conducted for only one or two skillsets rather than for all three skillsets at once, based on the visual analysis of the data.

Generalization Probe

The purpose of the generalization probe was to test if the skills learned during the training generalized to a novel situation—an interview with a parent rather than a mock interview with the experimenter. Prior to the generalization probe, the experimenter met with the parents individually via Zoom to discuss the study, its purpose, and review the informed consent form. Then, the interview was scheduled based on the parents’ and the participants’ availability. The participants also signed an additional form stating that information from the interview would be kept confidential and not shared with anyone other than the experimenter.

Participants were given instructions to interview a parent to gain information about their child, including obtaining information surrounding challenging behavior and/or areas of concern. Unlike during the study, the experimenter did not ask the participant if there were any steps they would like to take prior to the interview with the parent. This deviation from the roleplay context was intentional in order to create more realistic conditions and decrease prompting that would likely not occur in the natural context.

The interview was conducted via Zoom. The overall format closely matched the roleplay interviews that were conducted throughout the study with the experimenter. One notable exception was that one parent had their web camera turned off throughout the duration of the interview with Participant Mike. Otherwise, at the start of both of the interviews, the experimenter introduced the participant and the parent(s) to each other. The experimenter stated that the participant was going to practice the interviewing and assessment skills that they had worked on during the study within the context of being a clinician who is meeting a family for the very first time. The parents were reminded that if there were any questions they did not want to answer during the interview, they could decline at any time. In addition, the experimenter once again stated that video recording of the interview would occur so that the experimenter could collect the data, and that the recording would be destroyed as soon as data completion was completed. The experimenter then stated that she would leave the room so that they could conduct the interview without the experimenter present. Both parties were told that they would later be contacted for feedback regarding how the interview went. Final questions were then addressed.

No feedback or prompting was delivered by the experimenter during the interview, as the experimenter was not present. Interobserver agreement and procedural integrity data were not collected for additional protection of the privacy of the parents and their children.

Social Validity

Social validity was assessed using three different methods: participant survey, expert evaluation, and parent survey.

Participant Survey. Participants were given a brief survey via Qualtrics at the end of the study regarding their perceptions about aspects of the study such as the importance of the skills taught, the effectiveness of the training, and the likelihood of the participant recommending the training to others. A Likert scale was utilized on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). In addition, each question had a corresponding text box in which the participant could choose to provide additional comments/feedback. At the end of the survey, several open-ended questions were asked regarding the most and least helpful aspects of the training, as well as what can be changed in future replications of the study to improve the experience for the participants. No identifying information was collected, as the survey was completely anonymous.

Expert Evaluation. Two additional PhD-level students without prior knowledge of the specific details of the study served as expert evaluators. Both evaluators were BCBAs with prior experience working with families, clients, and practitioners from various cultural backgrounds both within the United States and across four additional countries. Each evaluator was also experienced in interviewing and the functional assessment of challenging behavior. One evaluator had been in the field for 14 years and had been certified as a BCBA for 12 years, whereas the other evaluator had been in the field for 9 years and had been certified for 6 years.

The expert evaluators scored 36.8% of roleplay interviews. The interviews were systematically chosen to ensure that a wide variety of levels of performance were viewed (e.g., videos with low, moderate, and high levels of correct responding). The expert evaluators did not have access to information regarding the phase of the study during which each interview was recorded. In addition, information was withheld regarding how the experimenter scored each of the videos and what the specific dependent measures of the study were. The order each evaluator was to score the videos was randomized using Random.org. While watching each video, the evaluators scored statements regarding a variety of skills such as demonstrating empathic and compassionate care and the cultural responsiveness of the interviewer. Utilizing a Likert scale, they rated each statement between a 1 (strongly disagree) and a 4 (strongly agree) based on the degree to which they agreed with each statement. Following the completion of the evaluations, the data were analyzed by first converting the evaluator’s data into a percentage (score given/total score possible). Then, the difference between the experimenter data and the evaluator data was calculated.

The expert evaluators both met with the experimenter for training prior to scoring the videos. Several additional important areas were identified by the evaluators such as the degree to which the interviewer worked to build rapport with the interviewee. As a result, four additional statements were added to the evaluation. While the evaluators and the experimenter discussed how they would rate both of the videos, IOA data were not taken, and there were no set criteria for mastery of the training as it were the case for secondary observers for PI and IOA.

Parent Survey. Following the generalization interview, a brief social validity survey was sent to the parents asking various questions regarding their experience throughout the interview.

Results

Baseline, Training, Maintenance, and Generalization Probe

Overall, the participants had the lowest baseline levels during roleplay interviews with functional assessment interviewing, closely followed by cultural responsiveness. The highest overall baseline levels were demonstrated in empathic and compassionate care. The greatest improvement across all three skillsets from baseline to training was seen in functional assessment interviewing, followed by cultural responsiveness, and then empathic and compassionate care. On average, skills were maintained at high levels during maintenance probes. Generalization probes were conducted for two participants, Karen and Mike. For both participants, overall high levels of responding generalized and maintained following an average of 33.75 days after the completion of their final trainings for each skillset.

Cultural Responsiveness

During baseline, data across participants were at overall moderate levels (M = 47.56). During training, overall high levels were demonstrated across all participants (M = 89.15). Following the completion of training, overall high levels were maintained (M = 87.5) across five participants. Participants tended to have most stable baseline data for this skillset compared to the other skillsets. Once introduced, BST was immediately effective in increasing correct responding to at least 80% for six out of seven participants. Responding maintained during the maintenance probe for four out of five participants and during the generalization probe for two out of two participants.

Functional Assessment Interviewing

Baseline data across participants were at overall lower levels (M = 38.02) compared to the other skillsets. During training, overall high levels were demonstrated across all participants (M = 87.26). One participant had low levels of responding following the first training for assessment skills; however, her performance substantially improved following the second training. Following training, overall high levels were maintained (M = 92.71) across six participants. Participants had overall stable rates of responding during baseline for this skillset except for one participant. BST was immediately effective in increasing correct responding to at least 80% for five out of seven participants. Responding maintained during the maintenance probe for six out of six participants and during the generalization probe for two out of two participants.

Empathic and Compassionate Care

Baseline data across participants were at overall higher levels relative to the other skillsets with a mean of 63.63%. During training, overall high levels were demonstrated across all participants (M = 90.84). Following the completion of training, overall high levels were maintained (M = 95.34) across four participants. In general, either overall higher levels of variability were seen during baseline relative to the other skillsets or overall increasing trend/higher levels of responding were demonstrated. Responding during training was above 80% correct for five out of seven participants and maintained during the maintenance probe for four out of four participants. During generalization, Karen’s responding maintained at high levels, whereas Mike’s responding decreased to slightly below 80%.

Training Time

The mean participation time in the study per participant averaged at 262.7 min or 4.4 hr (range: 219–363 min or 3.65–6.05 hr).

Order of BST Introduction

For Athena, Karen, and Mike, the three skillsets were taught during back-to-back sessions. Valentina had one extra session of BST for the first two skillsets and one extra session of baseline for Skillset 3, as her data showed an increasing trend in baseline and the experimenter chose to wait until the data stabilized. For Beatriz, there was a delay in teaching Skillset 3 by one session because her performance on Skillset 1 drastically dropped following training on Skillset 2. For Bernardus, there was a delay in teaching empathic and compassionate care (Skillset 3) by one session to ensure that his baseline data for that skillset stabilized and did not continue on an increasing trend. For Calliope, the introduction of BST for Skillset 2 was delayed, because after she received BST for Skillset 1, her performance on the roleplay interview remained similar to baseline levels.

Individual Participants

Participant 1

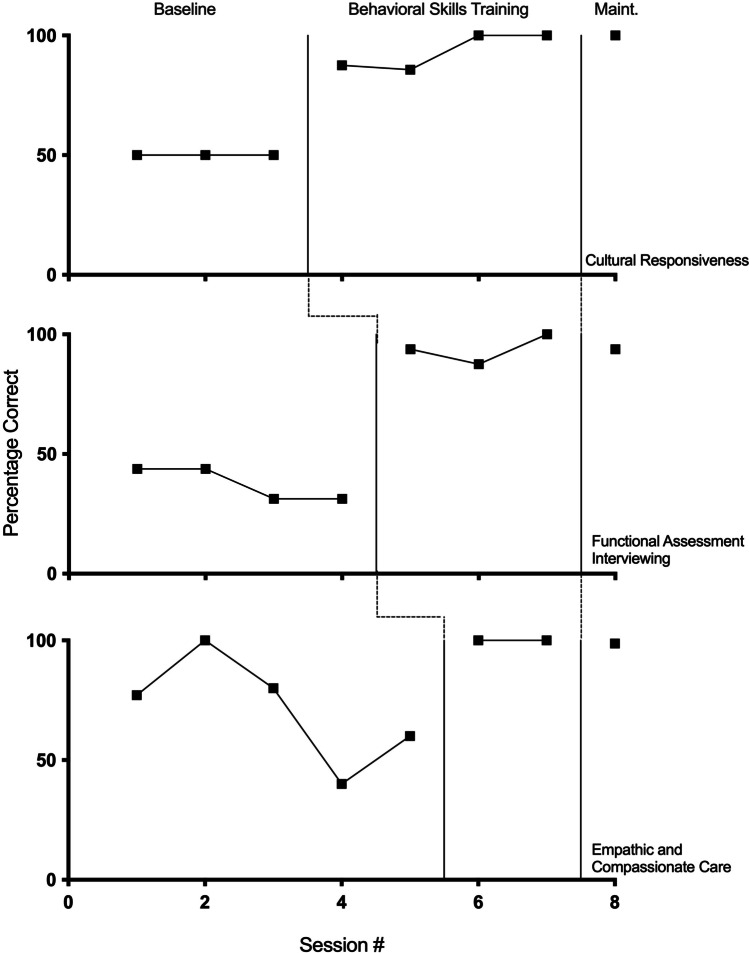

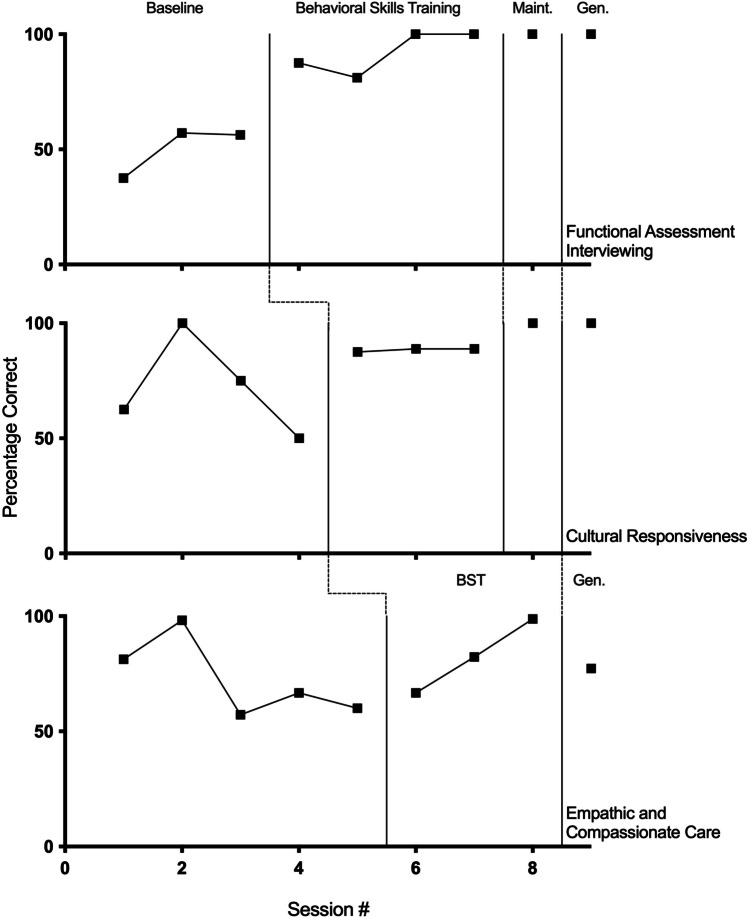

Athena’s data are shown in Fig. 1. For cultural responsiveness, the baseline data show moderate levels of responding at 50% with no variability. During treatment, high levels of correct responding were immediately demonstrated with only slight variability in the data, ranging from 85.7% to 100% (M = 93.3), with responding remaining at high levels during the maintenance probe. The baseline for functional assessment interviewing showed moderate to low levels of responding, ranging from 31.25 to 43.75% (M = 37.5), with an overall decreasing trend. During treatment, immediate high levels of responding and low levels of variability were demonstrated, ranging from 87.5% to 100% (M = 93.75). A high level of responding was maintained for this skillset. Baseline data for empathic and compassionate care showed overall high, variable levels of responding during the first three baseline sessions, ranging from 77.14% to 100% (M = 85.71). This was immediately followed by a decrease in baseline levels of responding, ranging from 40% to 60% (M = 50) once BST was introduced for the first two skillsets. When training began, high, stable levels of correct responding were demonstrated at 100% and high levels maintained during the maintenance probe.

Fig. 1.

Athena’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, and maintenance phases across cultural, assessment, and empathy and compassion skills

Participant 2

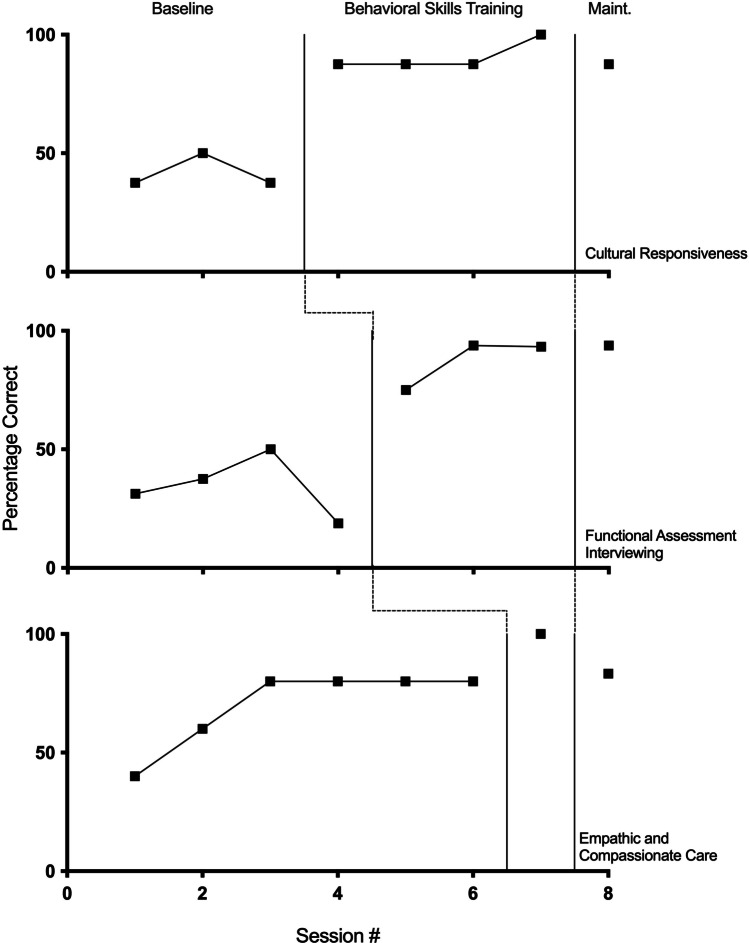

Valentina’s data are shown in Fig. 2. For cultural responsiveness, overall moderate levels of responding and low levels of variability were seen during baseline, ranging from 37.25% to 50% (M = 41.67). Baseline was followed by immediate high levels of responding, ranging from 87.5% to 100% (M = 90.63) and an increasing trend during the training phase. A high level of responding (87.5%) maintained during the maintenance phase. For functional assessment interviewing, overall low to moderate levels of responding were observed during baseline, ranging from 18.75% to 50% (M = 34.38), with an initial increasing trend, followed by a decrease in the level once BST was introduced for the first skillset. Following the introduction of intervention, high levels of responding were demonstrated, ranging from 75% to 93.75% (M = 87.36), and an increasing trend occurred. Responding remained at high levels during maintenance at 93.75%. Lastly, Valentina’s empathic and compassionate care showed an overall increasing trend across the first three baseline sessions, followed by four consecutive sessions at 80%. Overall, her baseline levels ranged from 40% to 80% (M = 70). Once progress was shown towards the first two skillsets, BST was introduced for empathic and compassionate care for one session during which 100% responding occurred. Although she was performing at high levels before intervention was introduced, her performance did increase to higher levels with training. Responding during the maintenance probe slightly decreased; however, it remained slightly higher than baseline levels at 83.33%.

Fig. 2.

Valentina’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, and maintenance phases across cultural, assessment, and empathy and compassion skills

Participant 3

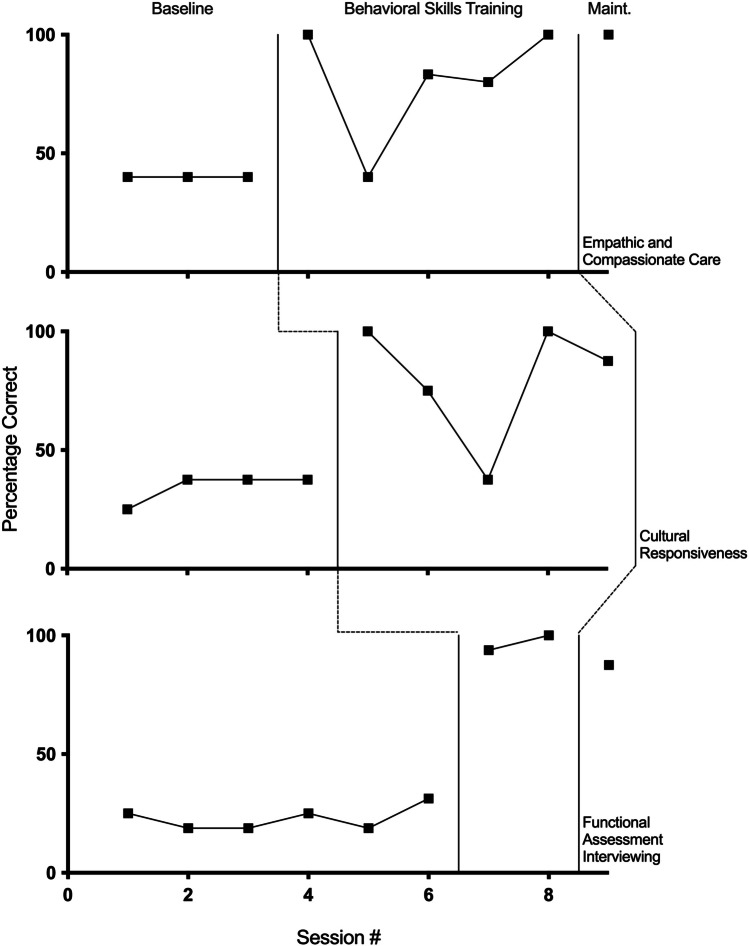

Beatriz’s data are depicted in Fig. 3. Baseline data for empathic and compassionate care show a moderate level of responding at 40%, with no variability or trend. During BST, high levels of responding were demonstrated with the exception of Session 5 (the first day of BST for the second skillset). Responding during the training phase ranged from 40% to 100% (M = 80.66). A high level of responding was maintained during the maintenance probe at 100%. Baseline data for cultural responsiveness show overall low to moderate levels of responding and low variability, ranging from 25% to 37.5% (M = 34.38). Overall high levels of responding were demonstrated during BST with the exception of Session 7 (the first training day for the third skillset). Responding during the training phase ranged from 37.5% to 100% (M = 80). No maintenance data were taken for this skill. Overall low baseline levels with low variability were seen for functional assessment interviewing, ranging from 18.75% to 31.25% (M = 22.92). High levels of responding were demonstrated during training, ranging from 93.75% to 100% (M = 96.88). A high level of responding was maintained following training at 87.5%.

Fig. 3.

Beatriz’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, and maintenance phases across empathy and compassion, cultural, and assessment skills

Participant 4

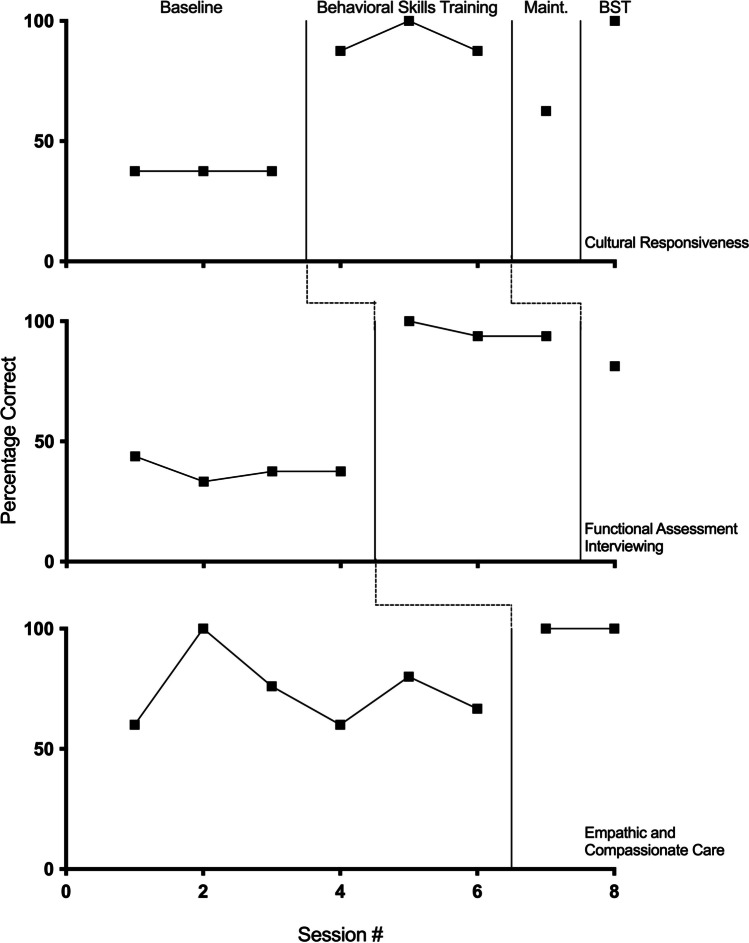

Bernardus’s data are shown in Fig. 4. Baseline levels of responding for cultural responsiveness remained at a moderate and stable level at 37.5% across three sessions. Following the introduction of BST, high levels of correct responding and low variability were shown, ranging from 87.5% to 100% (M = 91.67). Responding during maintenance decreased to 62.5%. During Session 8, BST was once again conducted, and responding returned to high levels at 100%. For functional assessment interviewing, moderate levels of responding with low levels of variability were seen during baseline, ranging from 33.33% to 43.75% (M = 38.02). Following the introduction of BST, high levels of responding with slight variability occurred, ranging from 93.75% to 100% (M = 95.83). Responding during maintenance remained above 80%. For empathic and compassionate care, overall moderate to high levels of baseline responding and variability were seen, ranging from 60% to 100% (M = 73.78). Following the introduction of BST, high, stable responding at 100% was demonstrated. No maintenance probe was conducted for this final skillset.

Fig. 4.

Bernardus’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, and maintenance phases across cultural, assessment, and empathy and compassion skills

Participant 5

Karen’s data are depicted in Fig. 5. Baseline data for cultural responsiveness showed moderate levels of responding at 50%. During training, high levels of responding were demonstrated, ranging from 87.5% to 100% (M = 95.83), with responding remaining at high levels during the maintenance probe. Karen’s generalization probe occurred 27 days following the end of her participation in the study. Responding during generalization decreased slightly to 77.8% correct; however, the two skills that were scored as an error during generalization included two skills that may have been nonapplicable given the context. For example, the participant used several idioms and expressions during the interview; however, both parents were fluent in English and, following the interview, stated that Karen used understandable language during the interview. This indicated that the target response was not applicable and did not negatively affect the interview. For functional assessment interviewing, overall moderate baseline levels of responding and low levels of variability were shown, ranging from 46.7% to 66.7% (M = 59.6). BST data showed high levels of responding and low levels of variability, ranging from 81.25% to 100% (M = 91.67). 100% responding maintained during the maintenance probe. Responding during generalization decreased slightly to 86.7% correct. Baseline data for empathic and compassionate care showed high levels of responding and a slight overall increasing trend, ranging from 76% to 83.3% (M = 79.9%). Karen’s training data ranged from 99.4% to 100% (M = 99.7). During maintenance and generalization, high levels of responding maintained.

Fig. 5.

Karen’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, maintenance, and generalization phases across cultural, assessment, and empathy and compassion skills

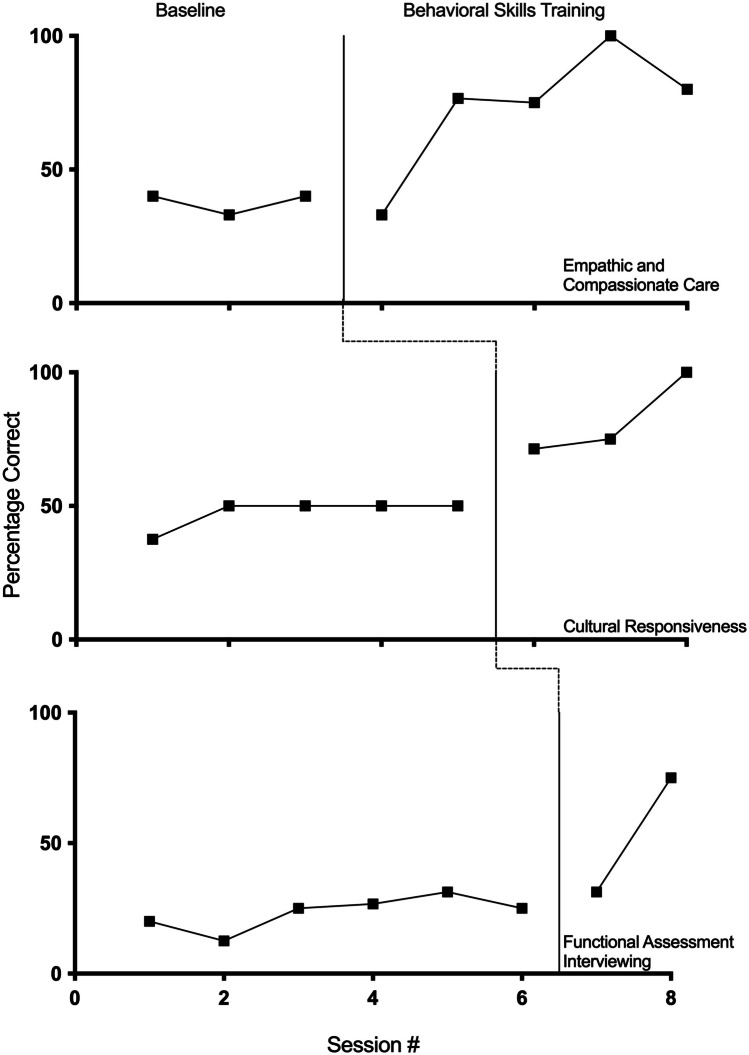

Participant 6

Figure 6 depicts Mike’s data. For functional assessment interviewing, overall moderate levels of responding were shown during baseline, ranging from 37.5% to 57.1% (M = 50.28). Once the BST phase began, there was an immediate increase in correct responding to high levels with little variability, ranging from 81.25% to 100% (M = 92.19). During both maintenance and generalization probes, Mike demonstrated 100% responding. For cultural responsiveness, overall moderate to high baseline levels were seen, ranging from 50% to 100% (M = 71.88). This was followed by high, stable levels of responding during BST, ranging from 87.5% to 88.9% (M = 88.43). Once again, 100% responding was seen during both maintenance and generalization. The baseline data for empathic and compassionate care showed overall moderate to high levels of responding, with variability seen in the first three sessions that stabilized prior to the introduction of BST. Mike’s baseline data ranged from 57.2% to 98.2% (M = 72.67). During training, moderate to high levels of responding with an increasing trend and no variability were shown, ranging from 66.7% to 98.8% (M = 82.6). No maintenance probe was conducted for this skillset; however, Mike’s performance decrease from 98.8% following his last training session to 77.3% during the generalization probe.

Fig. 6.

Mike’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, maintenance, and generalization phases across assessment, culture, and empathy and compassion skills

Participant 7

Calliope’s data are shown in Fig. 7. For empathic and compassionate care, moderate levels of responding with slight variability were seen during baseline, ranging from 33% to 44% (M = 37.67). During training, the data show an overall increasing trend with high levels of responding (with the exception of the first training session during which notes on the training were not taken) and low to moderate levels of variability. During the first training session, Calliope scored 33%, slightly lower than the average during baseline. For the remaining four training sessions, once note-taking began, Calliope’s performance ranged from 75% to 100% (M = 82.9). For cultural responsiveness, moderate baseline levels of responding and low variability were seen, ranging from 37.5% to 50% (M = 47.5). The training data showed an increasing trend with moderate to high levels of responding, ranging from 71.4% to 100% (M = 82.13). For functional assessment interviewing, overall low levels of responding and variability were demonstrated during baseline, ranging from 12.5% to 31.25% (M = 23.41). Only two training sessions occurred for this skillset, with 31.25% responding seen during the first session, followed by 75% during the second session. No maintenance data were taken across any skillset.

Fig. 7.

Calliope’s percentage of correct responding across baseline, training, and maintenance phases across empathy and compassion, cultural, and assessment skills

Social Validity—Participant Survey

The participants selected high ratings across all statements on the social validity survey. Each statement was rated as either 3 (agree) or 4 (strongly agree) for a mean score of 3.97 across 15 statements (see Table 4). Overall, the participants strongly agreed regarding the importance of the skill areas for ABA practitioners, as well as the effectiveness of different aspects of the training. In addition, the participants overall strongly agreed that they would recommend the training both to ABA professionals and other human service professions (e.g., speech-language pathologists, teachers). The most helpful aspects of the study were reported as the examples provided, the opportunity for repeated practice, the review of previously learned skills prior to moving on to the next skillset, the behavioral assessment section, and the roleplay component. One participant stated that the entire experience was beneficial as they had not received adequate training/tools from their employer regarding interviews and behavioral assessment. The participants also provided several recommendations regarding changes for future versions of the training. When asked if there were any additional comments or feedback, the overall responses indicated that the training was beneficial, enjoyable, helpful, concise, informative, generalizable, and provided positive feedback regarding the experimenter.

Table 4.

Participant responses to the social validity questionnaire—likert scale

| Statement Rated on Likert Scale | Mean (range) |

|---|---|

| Learning how to effectively conduct interviews with individuals from various cultural backgrounds is an important skill for practitioners of ABA to develop. | 4.0 |

| The training I received during the study improved my abilities to interview individuals from various cultural backgrounds | 4.0 |

| What I learned during the study specifically about cultural awareness skills is/will be applicable to my job | 4.0 |

| I found the examples of individuals from different cultures to be helpful and effective throughout the training | 4.0 |

| Learning how to effectively assess challenging behavior is an important skill for practitioners of ABA to develop. | 4.0 |

| The training I received during the study improved my skills of assessing challenging behavior | 4.0 |

| What I learned during the study specifically about assessing challenging behavior is/will be applicable to my job | 4.0 |

| I found the examples regarding assessing challenging behavior to be helpful and effective throughout the training | 3.86 (3–4) |

| Learning how to effectively interview others is an important skill for practitioners of ABA to develop. | 4.0 |

| The training I received during the study improved my abilities to interview others | 4.0 |

| What I learned during the study specifically about general interviewing skills is/will be applicable to my job | 4.0 |

| I found the examples regarding general interviewing skills to be helpful and effective throughout the training | 3.86 (3–4) |

| I would recommend this training to other graduate students within the field of ABA | 4.0 |

| I would recommend this training to other ABA practitioners (e.g., BTs who are not graduate students, BCBAs) | 3.86 (3–4) |

| I would recommend this training to other human service professionals (e.g., SLPs, teachers) | 4.0 |

| Total | 3.97 (3–4) |

Note. For each statement, participants chose from the options of 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree), and 4 (strongly agree)

Social Validity—Expert Evaluation

On average, the expert evaluator scores (based on a subjective Likert-scale rating) closely matched the objective data collected by the experimenter. This layer of analysis provided confirmation that the objective data collected matched overall subjective impressions of performance across the targeted skills, lending creditability to the data collection systems used within the study. The average difference between the data from the experimenter and the expert evaluator was 8.36 percentage points, ranging from 0.43 to 23.65. Thirteen videos had a difference in scores within 10 percentage points, six had a difference within 10–19 percentage points, and the remaining two videos had differences in scores of 20.20 and 23.65 percentage points respectively.

Social Validity—Parent Survey

Following the interview with Karen, the parents rated her performance using a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The parents gave Karen’s performance high scores across each of the 12 statements, including stating that they strongly agreed that Karen demonstrated the following skills throughout the interview: remaining engaged and actively listening to what they said throughout the interview; showing genuine empathy and compassion; asking for feedback; appearing professional, confident, and showing expertise; valuing their answers and opinions; asking enough questions to get to know their child better; using language that was understandable; not making any wrong and inappropriate assumptions about them or their child; not saying anything offensive or insensitive; considering the role of family and other important people in their child’s life; and respecting their culture and values. In addition, the parents strongly agreed that they would feel comfortable if, hypothetically speaking, Karen were a part of their child’s clinical team based on their interactions with her during the interview. The parent whom Mike interviewed did not complete the survey after the interview.

Discussion

The results of the study indicated that behavioral skills training was effective in increasing responding across all seven participants for functional assessment interviewing, empathic and compassionate care, and cultural responsiveness. In line with previous findings, many of the participants in the present study reported a lack of experience and training focused on these areas prior to the present study. Although baseline levels varied across participants, most of the participants demonstrated low or moderate baseline levels across all three skillsets. The overall lowest levels of correct responding were demonstrated across functional assessment interviewing, followed closely by cultural responsiveness. Although the highest baseline levels were seen for empathic and compassionate care, the average data indicated a need for improvement across the majority of the participants (only two participants demonstrated consistently stable, high levels of responding during baseline for this skillset). Overall improvement was not seen in baseline data prior to the introduction of BST, with a few exceptions (e.g., see Valentina’s graph).

Once BST was introduced, increased levels of responding were demonstrated on average across skillsets across all participants, including those participants whose baseline levels were already high for a given skillset during baseline. This is an important finding, as ABA literature often discusses the lack of training opportunities for these skills for practitioners, despite there being an established need for improvement in these areas (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Conners et al., 2019; LeBlanc et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2019). Furthermore, maintenance data suggest that the skills persisted after training. The social validity of the training and skills taught was high across participant opinion, expert evaluation, and parent opinion, further demonstrating the meaningfulness and authenticity of the training and results.

The present study extends the existing BST literature by successfully utilizing the training methodology to teach cultural responsiveness, functional assessment interviewing, and empathic and compassionate care. BST was immediately effective in teaching the skills within each skillset with only a few exceptions. In the few situations in which BST did not immediately and reliability improve the target skills within a specific skillset, adding additional booster BST sessions was subsequently effective (see graphs for Beatriz, Mike, and Calliope). It is important to note that because some participants already demonstrated moderate to high levels of responding within baseline for empathic and compassionate care skills, further research is needed to more carefully assess the effectiveness of BST for these specific skills.

The skills within each skillset were easily learned by all participants. Participation in the study was also efficient, taking less than 4.5 hr, on average (range: 3.65–6.05 hr), including time outside of the specific training period such as reviewing the study, conducting baseline, and building rapport with the participants. The participants described the training as being highly effective and the target skills as being highly important and applicable to their jobs. They also stated that they were likely to recommend the training to others, both to other practitioners within the field of ABA and non-ABA professionals in related fields.

There were several limitations to the present study that should be addressed. First, the study was conducted during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Several of the participants had major life events occur towards the middle and end of the study including job changes, loss of childcare, and potential contact with COVID-19 positive individuals. In addition, although assessing the skills using roleplay interviews was effective, practical, and feasible, the participants had limited practice with interviewing people other than the experimenter, including limited opportunities with actual parents outside of the hypothetical context. It is hypothesized that if the participant interviewed several different people during the training phase, rather than the experimenter each time, performance would have likely been affected. Future research should incorporate roleplay opportunities with more than one person during the study. It is important to note that it would be ideal if these additional interview partners are from various ethnic, racial, and cultural backgrounds.

Furthermore, the study was completely fully on Zoom via videoconferencing. It is unclear if the demonstration of these specific skills would generalize to an in-person interview. Given the state of the world and the increased use of telehealth, both formats are important and to be analyzed accordingly. Future research should consider practicing the target skills in-person, if possible, or, at minimum, completing a generalization probe within an in-person format. An additional factor to consider is how the telehealth format and context of the role play interviews affected the selection of the target skills. For example, some additional recommendations found in the literature for functional assessment interviewing, empathic and compassionate care, and cultural responsiveness were found to either be difficult to assess via telehealth or were not applicable to video interviews, such as body positioning relative to the interviewee. Additional skills identified included body language, maintaining appropriate levels of eye contact with the interviewee, asking whether the interviewee would feel more comfortable answering questions in an oral or written format, and considering some other specific cultural norms and values (Coulehan et al., 2001; Hughes Fong et al., 2016). Despite these limitations, each of these recommendations were briefly discussed with each participant in terms of how they would be relevant within the context of an in-person interview. Some additional consideration may be given to other aspects of interviewing and social interactions such as rapport building.

The definitions of the target skills provided another challenge within the study. For example, the definitions did not account for quality or the sincerity of empathic statements. Therefore, the participant may have been marked as correct for delivering an empathic statement, but their delivery or tone may have been received as ingenuine which may be problematic and damaging to rapport within the context of a real interview. Other target skills were difficult to objectively define in a complete manner such as what constitutes an English idiom or expression or which terms would be considered technical jargon (e.g., for the purposes of this study, “reinforcers” were identified as technical language, but some other individuals expressed that they considered this common language). Future research must continue to look for ways to make definitions more objective and clearer, as well as to identify the number of exemplars needed for effective training in specific skills.

In addition, it was challenging to determine how often the participants should be demonstrating some of the skills such as offering empathy, summarizing information provided by the interviewee, and requesting feedback and corrections from the interviewee. For the purposes of the study, they were required to demonstrate each of those skills only once. Some participants only demonstrated each skill one time to meet criterion, whereas some others demonstrated the skills frequently throughout the interviews. This is an area for increased definition and exploration that will require additional social validity and preference assessments; however, the degree to which the expert evaluator scores aligned with the experimenter data lends credibility to the way that skills were defined and measured. Future research could continue to assess which targets to teach for these skill areas, as well as how to best measure and define them (e.g., Bonvicini et al., 2009).

Additional factors regarding the expert evaluators could be considered. The individual learning histories of the expert evaluators may have affected their perceptions of empathy and cultural responsiveness, and this may have subsequently affected their ratings. It would be ideal if the evaluators not only have expertise in the functional assessment of behavior and empathic and compassionate case, but would also share cultural backgrounds with the hypothetical family being interviewed.

Some of the participants found synthesizing all the skills together to be difficult. For example, some participants stated that they were unsure of when to ask questions regarding the culture within the interview. They also sometimes reported difficulty keeping track of which questions they already asked the interviewee, as well as ensuring that they demonstrated each of the 31 identified skills. Taking notes on the target skills during the training appeared to help participants; however, it was not a required portion of the study. The utility of notetaking could be systematically assessed.

Future replications of the procedures could be conducted across other participants, including behavior therapists who are not graduate students, BCBAs, and non-ABA practitioners working with similar populations in related fields. It is important to note, however, that the participants included within this study varied in age, gender, geographic location within the United States, country of origin, race, ethnicity, languages fluently spoken, and years and type of previous experience. It would, however, be beneficial to replicate the study with students and practitioners residing outside of the United States, particularly in terms of the social validity and relevance of the skills taught.

Once the findings of the present study are replicated, it is suggested that a version of the training be adapted for the classroom format to increase instructional efficiency. Although participation in the study was efficient for each individual participant, the implementation of baseline, training, and maintenance across the seven participants totaled 30.65 hr for the experimenter and occurred across 21 days. This total duration does not include scoring each video, nor training additional members of the research team. Future research may explore adapting the training into a group BST format (e.g., similar to Parsons et al., 2013), while assessing if the efficacy maintains at high levels without the individualized one-to-one approach.

Future research can also expand on the assessment of the generalization and maintenance of the target skills. Generalization probes were conducted for only two participants, as they were an optional component of the study and only two families were available to participate as interviewees. The present study assessed maintenance by conducting roleplay interviews in the absence of BST or the summary of skills occurring prior to the interview during that given session; however, maintenance may have occurred within a short timeframe following the last BST session for a given skillset (e.g., the next day or a few days afterwards). It is important to reiterate, however, that both participants who completed the generalization probes conducted the interviews after an average of 34 days following their final trainings. Both participants showed overall high levels of responding across the skillsets even after more than 4 weeks’ time. Nevertheless, future research should test for maintenance within a more uniform time frame that has more time in between the last training session and the maintenance probe (e.g., 1 week, 1 month) across all participants.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated an effective, efficient, and socially valid method of teaching a variety of skills that are essential for ABA practitioners to develop. Future research can expand on these findings and continue to explore methods for teaching skills that are often understudied within our field. As the field moves to enact change in culturally responsive and compassionate care, it is important to explore effective methods to teach and train these skills. In addition, it is vital to evaluate the quality of the responses and the generalization of these skills to real-world interactions. It is hoped that this study represents a commitment to study these areas, to define these skills, to train practitioners in implementation of these skills, and to evaluate whether such training results in socially valid outcomes.

Appendix 1

List of target skills, descriptions, examples, and nonexamples as provided during the trainings, as well as the measurement for each skill. Unless otherwise noted, the data were measured using percentage of correct responding. Please note: several assessment skills were taught simultaneously during the training and appear in the table accordingly.

| Functional Assessment Interviewing | |

|---|---|

| Skill (list, description, examples, nonexamples) | Measurement |

|

1/2. Before the interview: [1] Conduct a record review and [2] obtain information regarding any diagnoses and medical conditions/concerns - Description – Obtain any reports or records available such as IEP plans, previous evaluations, relevant medical reports. Verify the information during the interview, as well. - Example – Prior to the interview, the behavior analyst asks, “Is there anything such as school or medical reports and records that you would feel comfortable giving me a copy of prior to our interview so that I can learn some additional information ahead of time?” - Nonexample – The interviewer does not ask the caregiver for any medical or diagnostic information. |

Skill 1 (+) stated they would conduct a record review prior to the interview (–) did not ask or asked after the interview started Skill 2 (+) inquired about both diagnostic and medical information (–) did not inquire about both |

|