Abstract

Background:

Vaping is a major health risk behavior which often occurs socially. Limited social activity during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to worsening social and emotional health. We investigated associations among youth vaping, and reports of worsening mental health, loneliness, and relationships with friends and romantic partners (ie, social health), as well as perceived attitudes toward COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Methods:

From October 2020 to May 2021, a clinical convenience sample of adolescents and young adults (AYA) reported on their past-year substance use, including vaping, their mental health, COVID-19 related exposures and impacts, and their attitudes toward non-pharmaceutical COVID-19 mitigation interventions, via a confidential electronic survey. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to estimate associations among vaping and social/emotional health.

Results:

Of 474 AYA (mean age = 19.3 (SD = 1.6) years; 68.6% female), 36.9% reported vaping in the prior 12 months. AYA who self-reported vaping were more likely than non-vaping AYA to report worsening: anxiety/worry (81.1%; P = .036), mood (78.9%; P = .028), eating (64.6%; P = .015), sleep (54.3%; P = .019), family discord (56.6%; P = .034), and substance use (54.9%; P < .001). Participants who vaped also reported easy access to nicotine (63.4%; P < .001) and cannabis products (74.9%; P < .001). No difference in perceived change in social wellbeing was seen between the groups. In adjusted models, vaping was associated with symptoms of depression (AOR = 1.86; 95% CI = 1.06-3.29), less social distancing (AOR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.11-2.98), lower perceived importance of proper mask wearing (AOR = 3.22; 95% CI = 1.50-6.93), and less regular use of masks (AOR = 2.98; 95% CI = 1.29-6.84).

Conclusions:

We found evidence that vaping was associated with symptoms of depression and lower compliance with non-pharmaceutical COVID-19 mitigation efforts among AYA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: vaping, cannabis, nicotine, adolescents, young adults, mental health, COVID-19

Introduction

While there has been a decline in the use of traditional cigarettes among adolescents and young adults (AYA) over the last decade, 1 e-cigarettes are among the more recently developed devices that re-popularized nicotine use among these age groups. Traditional e-cigarettes are electronic devices that heat nicotine-containing solutions to deliver aerosolized nicotine. E-cigarettes entered the market in the United States in 2007 and became popular with adolescents a few years later. The use of e-cigarettes or “vaping” increased nearly 1000-fold from 2011 to 2015 2 among high school students. In addition, e-cigarette usage among adolescents expanded from traditional e-cigarettes to a variety of other vaping products that also facilitate the ingestion of cannabis and other flavorings. 3 In 2019, the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, among students in the 12th, 10th, and 8th grades, daily or near daily use of nicotine vaping was reported by 11.7%, 6.9%, and 1.9% of students respectively, 4 while daily or near daily cannabis vaping was reported by 3.5%, 3.0%, and 0.8% of students respectively. 5

In 2020, e-cigarette, or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) in the United States was identified, and reported cases exceeded 2800, including 68 deaths. 6 Early research has shown links between EVALI and specific components of non-regulated e-liquid, in particular tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing vaping products and vitamin E acetate, although other components of the e-liquid used in vaping devices have not been ruled out as possible contributors to EVALI. 6 The implications of vaping use likely go far beyond lung injury, as early substance use may lead to the development of substance use disorders and dependence which could be chronic, debilitating, and in some cases fatal. 7 Further, early substance use may foster the development of secondary health effects, leading to the precipitation, or worsening, of mood, appetite, and sleep disorders in those who vape various substances through direct effects of use, or during periods of withdrawal from the substance.8-10 Previous work has identified significant associations between AYA vaping and mental health comorbidities, 11 with bi-directional associations being found with depression8,11,12 and limited evidence for an association with anxiety. 11 AYA have been shown to vape to buffer stress and depressive symptoms,13,14 and maintain social connections with peers who vape, 15 as vaping is often a social activity among young people 15 with almost 40% of 12th graders reporting that they vaped to have a good time with their peers. 16

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced numerous additional stressors into the daily lives of AYA, including school closures, restricted opportunities for in-person social interactions, and enforcement of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI; ie, mask wearing and social distancing) to mitigate COVID-19 exposure.17,18 Recent studies have reported worsening mental health including increased anxiety, depression, and feelings of loneliness among children and adolescents, 19 as well as an increase in suicides 20 during the pandemic, which hints at the difficulties that many adolescents faced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In terms of adolescent substance use, the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic appear to be mixed. Past year e-cigarette usage rates among high school students, which had risen from 2017 to 2019, leveled off but remained high. 21 Among AYA who used e-cigarettes in general prior to the pandemic, more than half changed their patterns of use with roughly one third quitting, and one third reducing use, but nearly 1 in 5 increased their nicotine use, nearly 1 in 12 increased their cannabis use, and the remainder switched to other products. 22 Among AYA who vaped cannabis prior to the pandemic, 6.8% reported increasing cannabis vaping since the pandemic, 37.0% reported quitting or reducing vaping in general, and 42.3% reported no change early in the pandemic. 23

Given the often social nature of vaping, AYA who engaged in vaping during the pandemic may have had the opportunity to benefit from maintaining social connections, 24 and thus may have lessened the negative social and emotional effect of isolation during the pandemic. Despite this however, we hypothesize that prior established positive associations among vaping, poor mental, and social health would hold for AYA who vaped during the pandemic. In this study, we sought to characterize the associations among vaping, emotional, and social wellbeing for AYA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, vaping requires the removal of masks to facilitate use of the vaping device, and vaping in groups increases opportunities to disregard social distancing measures put in place during the pandemic to reduce exposure to COVID-19. That said, we also explored whether AYA who vaped during the pandemic were more likely than those who did not vape to report attitudes and behaviors that disfavored use of NPI (ie, masking and social distancing). Low value for and low adherence to NPI among AYA who vape could reflect an underlying propensity for risk taking and low value for health. Similarly, vaping may signify an underlying tendency to deny and discount the importance of recommended health protecting behaviors (NPI) that might serve to limit exposure to COVID-19.

Methods

Participants

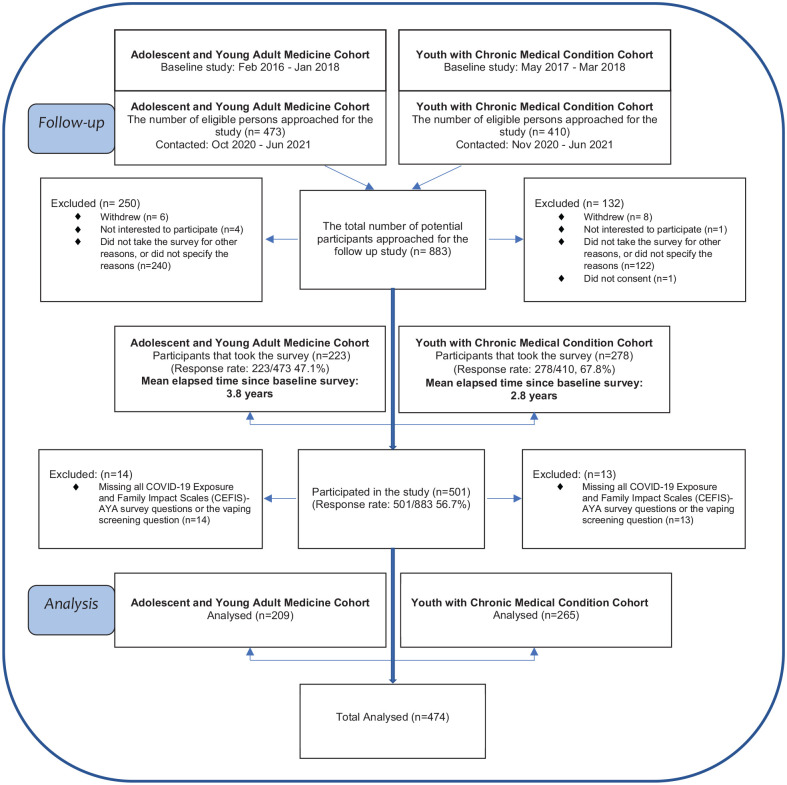

From October 2020 to June 2021, we sought to recruit N = 883 AYA, aged 16 to 23 years, who had participated in a longitudinal study 24 to 48 months prior, to complete a confidential follow-up survey (Figure 1). May 2021 marked the last successful enrollment and is utilized as the study end date. Results of the initial projects have been described previously.25-28 The initial group was comprised of AYA who received primary care at a general adolescent/young adult medicine clinic (N = 473) and AYA with a chronic medical condition who received subspecialty care in the rheumatology, endocrinology, or gastroenterology departments (N = 410) at a medical institution in the United States (Figure 1). Of those invited, N = 501 (56.7%) agreed to participate in the follow-up survey. Under the approval of the hospital’s Institutional Review Board, adolescents aged 16 to 17 years provided assent to participate in this cross-sectional survey study with a waiver of parental consent, and those aged 18 years or over provided informed consent. All participants received a $20 Amazon gift card.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for inclusion of study participants.

Survey Measures

The survey assessed 11 to 13 domains of interest, with the total number of questions varying depending on responses, with a maximum of 135 total items. In addition, participants were invited to complete the COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Adolescent and Young Adult Version (CEFIS-AYA) 29 measure, which consists of 44 questions, developed to assess adolescent and family exposures to COVID-19 related events, impacts on emotional and physical wellbeing, and overall pandemic distress.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants self-reported their age in years, sex, race, ethnicity, number of parents/guardians in the household, educational/occupational status, and highest level of education attained by a parent. Participants were also evaluated with the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) item screen for depression, 30 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) item screen for anxiety. 31

Substance Use Behaviors

The frequency of vaping during the past year was obtained using the following question and scaled response choice: “ In the past 12 months, how many times have you vaped anything? (Including “nicotine,” “cannabis” (marijuana), or “just flavoring”) —1. Never, 2. Once/Twice, 3. Monthly, 4. Weekly.” While cannabis is used here, “marijuana,” a more familiar term, was used in the survey.

The type of vaping was assessed among those who self-reported past-year use by asking: “In the past 12 months, which of the following have you vaped? Nicotine, Cannabis, Just Flavoring with response options —”Yes”/”No” for these 3 choices. Ease of access to substances was assessed asking, “How difficult is it for you to get: (1) Nicotine vaping products and (2) Cannabis, if you want some?” , with responses options “probably impossible/very difficult/fairly difficult/fairly easy/very easy/Not applicable (NA).” Positive responses of “fairly easy” and “very easy” were grouped against responses of “probably impossible,” “very difficult,” and “fairly difficult.” Responses of “NA/missing” were grouped separately. The survey also included Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) screening questions 32 assessing past-year alcohol, cannabis, or tobacco use.

COVID-19 Pandemic Related Exposures, Impacts, and Distress

Participants completed the COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Adolescent and Young Adult Version (CEFIS-AYA) 29 validated questionnaire that included exposure to a range of pandemic-related events (CEFIS Exposure Scale), perceived impacts of the pandemic on areas of social-emotional functioning (CEFIS Impact Scale), and a measure of overall pandemic-related distress (CEFIS Distress Scale). 29 The questionnaire opened with the introduction, “In answering these questions, please think about what has happened from March 2020 to the present, due to COVID-19,” and asks the participants to reflect on their COVID-19 related experiences. The CEFIS Exposure scale consists of 28 binary items (“Yes”/”No”) asking about the individual or family member’s COVID-19 related experiences, including 6 items with Not applicable (NA) options. The CEFIS Exposure Score is a total count of “Yes” responses, and the summed score could range from 0 to 28, where higher scores indicate greater exposure to COVID-19-related events. 30 Items marked “NA” or missing responses were assigned “0.”

Pandemic-related impacts on each of 15 items reflecting areas of social-emotional wellbeing were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (the pandemic made it: 1 = Made it a lot better; 2 = Made it a little better; 3 = Made it a little worse; and 4 = Made it a lot worse) and included a Not Applicable (NA) response. Among the pandemic-related impact items, the family relationship, and relationship with friends was assessed with the following 2 questions: “COVID-19 may have many impacts on you and your family life. In general, how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected each of the following: (1) how family/household members get along, and (2) your social well-being — relationships with friends?” A single distress item used a 1 to 10-point Likert scale. Higher scores denoted more negative impact/more distress. We assigned 0 to “NA” for the CEFIS Impact items and excluded those who missed the entire CEFIS Exposure questions, or more than 5 CEFIS Impact items or the CEFIS Distress item. For the analyses, the CEFIS AYA Exposure items were dichotomized as “Yes” versus “Other (“No/NA/missing”),” and CEFIS AYA impact items were dichotomized as “Made it a lot/little worse” versus “Other (“Made it a lot/little better/NA or missing”).”

Non-Pharmaceutical Preventive Health Measures

Participants’ attitudes toward social distancing and mask wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic were assessed with the following 2 questions: “Based on what you’ve heard and know about COVID-19, (1) how important is it to stay 6 ft. apart? and (2) how important is it to wear a mask covering your nose and month in the presence of people outside your home?” with response options of, “Not important/slightly important/moderately important/important/very important.” Responses of either “important” or “very important” were considered positive for sufficiently regarding the importance of these measures and were grouped together and compared against the remaining group of answer choices, composed of “Not important,” “slightly important,” and “moderately important” responses. The frequency of compliance with non-pharmaceutical interventions was assessed with the following 2 questions “When outside your home in public, how regularly do you: (1) stay 6 feet apart and (2) wear a mask covering your nose and mouth?” with responses options of “Never/rarely/sometimes/usually/always.” Responses of either “usually” or “always” were considered positive for compliance and were grouped together and compared against the remaining group of answer choices, composed of “never,” “rarely,” and “sometimes” responses.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). P-values were 2-sided, with a significance threshold of .05. We excluded 27 participants with missing survey data on past year vaping and COVID-19 impact items, leaving a total analyzable sample of n = 474 (Figure 1).

Sociodemographic and health characteristics, COVID-19 related exposures, impacts, and distress were compared between those who vaped and those who did not using Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, t-tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate. Characteristics that differed significantly between vaping and non-vaping groups in bivariate analyses were examined using multivariable logistic regression with vaping as the dependent variable, adjusting for age, sex, race, and ethnicity, parental household composition, cohort (general medicine vs specialty clinics), PHQ-2 score (depression screening), and GAD-2 score (anxiety screening). We adjusted for date of survey completion to address potential confounding effects on responses due to vaccine availability and disease prevalence. CEFIS Scores were centered around the mean in regression analyses, respectively. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated controlling for age, sex, household composition, cohort, period of the survey, PHQ-2 score (depression screening), and GAD-2 score (anxiety screening).

Results

Participants

Of 474 participants, the mean age was 19.3 years old (SD = 1.6; range = 16.0-23.0 years), 68.6% were female, 61.2% identified as white, and 81.6% reported being of non-Hispanic/non-Latino ethnicity. Most (71.5%) respondents were from 2-parent homes.

Vaping and Other Substance Use

More than one third (36.9%) of participants reported that they had vaped within the last 12 months and nearly two thirds of them reported having vaped cannabis (63.4%) and nicotine (62.3%), with fewer (14.9%) reporting they vaped “just flavoring” (Table 1). AYA who reported they vaped were more likely to report easy access to nicotine (63.4% vs 18.4%, P < .001) as well as cannabis (74.9% vs 26.4%, P < .001) products (Table 1). AYA reporting past 12-month vaping were more likely to screen positive for depression (24.0% vs 14.7%, P = .011), and less likely to be from 2-parent homes (64.0% vs 75.9%, P = .006; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample, Overall, and Grouped by Any Vaping in the 12 Months Prior to Survey Completion (n = 474).

| Characteristics | Overall | Vaping in the prior 12 months | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | No | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| 474 (100) | 175 (36.9) | 299 (63.1) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 19.3 (1.6) | 19.6 (1.5) | 19.1 (1.6) | <.001 |

| Median (range) | 19.0 (16.0-23.0) | 20.0 (16.0-23.0) | 19.0 (16.0-22.0) | .001 |

| Survey period | ||||

| 2020 Oct to 2021 Jan | 401 (84.6) | 147 (84.0) | 254 (84.9) | .78 |

| 2021 Feb to 2021 May | 073 (15.4) | 28 (16.0) | 45 (15.1) | |

| Clinic | ||||

| Adolescent general medicine | 207 (43.7) | 83 (47.4) | 124 (41.5) | .023 |

| Endocrinology | 116 (24.5) | 44 (25.1) | 72 (24.1) | |

| Rheumatology | 067 (14.1) | 29 (16.6) | 38 (12.7) | |

| Gastroenterology | 084 (17.7) | 19 (10.9) | 65 (21.7) | |

| Cohort | ||||

| AYAM | 209 (44.1) | 83 (47.4) | 126 (42.1) | .26 |

| YCMC | 265 (55.9) | 92 (52.6) | 173 (57.9) | |

| Biological sex | ||||

| Male | 149 (31.4) | 54 (30.9) | 95 (31.8) | .84 |

| Female | 325 (68.6) | 121 (69.1) | 204 (68.2) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 290 (61.2) | 101 (57.7) | 189 (63.2) | .13 |

| Black | 064 (13.5) | 27 (015.4) | 37 (012.4) | |

| Asian | 022 (04.6) | 5 (2.9) | 17 (5.7) | |

| Other/mixed | 088 (18.6) | 40 (22.9) | 48 (16.1) | |

| Prefer not to answer or missing | 010 (02.1) | 2 (1.1) | 8 (2.7) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 081 (17.1) | 35 (20.0) | 46 (15.4) | .3 |

| Non-Hispanics or non-Latino | 387 (81.6) | 139 (79.4) | 248 (82.9) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (1.7) | |

| Household composition | ||||

| Foster care/1 parent/none | 135 (28.5) | 63 (36.0) | 72 (24.1) | .006 |

| 2 parents | 339 (71.5) | 112 (64.0) | 227 (75.9) | |

| Parent education | ||||

| College or higher | 336 (70.9) | 121 (69.1) | 215 (71.9) | .52 |

| Less than college | 138 (29.1) | 54 (30.9) | 84 (28.1) | |

| Health screening | ||||

| Depression screening | ||||

| Negative (PHQ-2 score <3) | 388 (81.9) | 133 (76.0) | 255 (85.3) | .011 |

| Positive (PHQ-2 score ≥3) | 86 (18.1) | 42 (24.0) | 44 (14.7) | |

| PHQ-2 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Median (range) | 1.0 (0.0-6.0) | 2.0 (0.0-6.0) | 1.0 (0.0-6.0) | <.001 |

| Anxiety screening | ||||

| Negative (GAD-2 score <3) | 348 (73.4) | 123 (70.3) | 225 (75.3) | .24 |

| Positive (GAD-2 score ≥3) | 126 (26.6) | 52 (29.7) | 74 (24.7) | |

| GAD-2 score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.7) | .054 |

| Median (range) | 1.0 (0.0-6.0) | 2.0 (0.0-6.0) | 1.0 (0.0-6.0) | .026 |

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 393 (82.9) | 145 (82.9) | 248 (82.9) | .98 |

| Poor/fair | 81 (17.1) | 30 (17.1) | 51 (17.1) | |

| Substance use | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| Any alcohol use past 12 months | 280 (59.1) | 153 (87.4) | 127 (42.5) | <.001 |

| Any binge drink past 3 months | 115 (24.3) | 76 (43.7) | 39 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Cannabis | ||||

| Any cannabis use past 12 months | 189 (39.9) | 139 (79.4) | 50 (16.7) | <.001 |

| Any cannabis use past 3 months | 158 (33.3) | 118 (67.4) | 40 (13.4) | <.001 |

| Frequency of cannabis use in days—past 3 months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.4 (22.8) | 22.2 (31.2) | 1.8 (10.0) | <.001 |

| Median (range) | 0.0 (0.0-90.0) | 5.0 (0.0-90.0) | 0.0 (0.0-90.0) | <.001 |

| Tobacco | ||||

| Any tobacco use—past 12 months | 79 (16.7) | 68 (38.9) | 11 (3.7) | <.001 |

| Type of vaping | ||||

| Nicotine | 109 (23.0) | 109 (62.3) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Cannabis | 111 (23.4) | 111 (63.4) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Just flavor | 26 (5.5) | 26 (14.9) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| How difficult is it for you to get nicotine vaping products if you want some? | ||||

| Probably impossible/very/fairly difficult | 68 (14.3) | 23 (13.1) | 45 (15.1) | <.001 |

| Fairly/very easy | 166 (35.0) | 111 (63.4) | 55 (18.4) | |

| N/A | 240 (50.6) | 41 (23.4) | 199 (66.6) | |

| How difficult is it for you to get cannabis (marijuana) if you want some? | ||||

| Probably impossible/very/fairly difficult | 75 (15.8) | 22 (12.6) | 53 (17.7) | <.001 |

| Fairly/very easy | 210 (44.3) | 131 (74.9) | 079 (26.4) | |

| N/A | 189 (39.9) | 22 (12.6) | 167 (55.9) | |

| Non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) practices | ||||

| Based on what you’ve heard and know about COVID-19, how important is it to: stay 6 ft. apart? | ||||

| Very important/important | 414 (87.3) | 146 (83.4) | 268 (89.6) | .050 |

| Not/slightly/moderately important | 60 (12.7) | 29 (16.6) | 31 (10.4) | |

| Based on what you’ve heard and know about COVID-19, how important is it to: wear a mask covering your nose and mouth in the presence of people outside your home? | ||||

| Very important/important | 440 (92.8) | 153 (87.4) | 287 (96.0) | <.001 |

| not/slightly/moderately important | 34 (7.2) | 22 (12.6) | 12 (4.0) | |

| When outside your home in public, how regularly do you: Stay 6 ft. apart? | ||||

| Always/usually | 386 (81.4) | 133 (76.0) | 253 (84.6) | .020 |

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 88 (18.6) | 42 (24.0) | 46 (15.4) | |

| When outside your home in public, how regularly do you: Wear a mask covering your nose and mouth? | ||||

| Always/usually | 447 (94.3) | 158 (90.3) | 289 (96.7) | .004 |

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 27 (5.7) | 17 (9.7) | 10 (3.3) | |

| COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Scales (CEFIS) | ||||

| CEFIS distress a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (2.4) | 6.2 (2.3) | 5.8 (2.4) | .06 |

| CEFIS impact b | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.7) | .001 |

| CEFIS exposure c | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.8 (3.6) | 8.9 (3.7) | 8.7 (3.5) | .61 |

| CEFIS impact items | ||||

| How family/household members get along | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 236 (49.8) | 76 (43.4) | 160 (53.5) | .034 |

| A lot/a little worse | 238 (50.2) | 99 (56.6) | 139 (46.5) | |

| Physical wellbeing—eating | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 202 (42.6) | 62 (35.4) | 140 (46.8) | .015 |

| A lot/a little worse | 272 (57.4) | 113 (64.6) | 159 (53.2) | |

| Physical wellbeing—sleeping | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 250 (52.7) | 80 (45.7) | 170 (56.9) | .019 |

| A lot/a little worse | 224 (47.3) | 95 (54.3) | 129 (43.1) | |

| Physical wellbeing—substance use (smoking/vaping, drinking alcohol, cannabis (marijuana) use, etc.) | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 345 (72.8) | 79 (45.1) | 266 (89.0) | <.001 |

| A lot/a little worse | 129 (27.2) | 96 (54.9) | 33 (11.0) | |

| Emotional wellbeing—anxiety/ worry | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 115 (24.3) | 33 (18.9) | 82 (27.4) | .036 |

| A lot/a little worse | 359 (75.7) | 142 (81.1) | 217 (72.6) | |

| Emotional wellbeing—mood | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 128 (27.0) | 37 (21.1) | 91 (30.4) | .028 |

| A lot/a little worse | 346 (73.0) | 138 (78.9) | 208 (69.6) | |

| Emotional wellbeing—loneliness | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 128 (27.0) | 42 (24.0) | 86 (28.8) | .26 |

| A lot/a little worse | 346 (73.0) | 133 (76.0) | 213 (71.2) | |

| Social wellbeing—relationships with friends | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 150 (31.6) | 58 (33.1) | 92 (30.8) | .59 |

| A lot/a little worse | 324 (68.4) | 117 (66.9) | 207 (69.2) | |

| Social wellbeing—romantic relationships or dating | ||||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | 230 (48.5) | 77 (44.0) | 153 (51.2) | .13 |

| A lot/a little worse | 244 (51.5) | 98 (56.0) | 146 (48.8) | |

CEFIS: COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Scale.

Significant P-values are highlighted in Bold.

CEFIS overall distress is scaled as (1 = no distress and 10 = extreme distress).

CEFIS impact score (range: 0-4) is the mean of pandemic impacts on emotional, physical, and social wellbeing. Participants with 5 or more missing data were excluded “Not applicable (NA)” or “missing” was coded as 0.

CEFIS exposure score (range: 0-28) is the sum of COVID-19 related events. “Not applicable (NA)” or “missing” was coded as 0.

Compared to AYA reporting no past-year vaping, adolescents who vaped were more likely to report past-year use of tobacco (38.9% vs 3.7%, P < .001), cannabis (79.4% vs 16.7%, P < .001), and use of alcohol (87.4% vs 42.5%, P < .001; Table 1). They were also more likely to report binge drinking (43.7% vs 13.0%, P < .001), and greater median frequency of cannabis use (5 days (IQR = 0.30) vs 0 days (IQR = 0.0), P < .001) during the 3 months preceding the survey (Table 1). In the adjusted analyses, those who vaped were more likely to report past-year cannabis (AOR = 20.15, 95% CI: 12.01-33.81), alcohol (AOR = 10.90, 95% CI: 6.23-19.09) and tobacco use (AOR = 17.70, 95% CI: 8.69-36.05) and “Very/Fairly easy” access to nicotine vaping products (AOR = 3.93, 95% CI: 2.11-7.33) and cannabis (AOR = 4.06, 95% CI: 2.23-7.38; Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations Between Selected Measures of Health, Behaviors, CEFIS, and Vaping (n = 474).

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR a (95% Cl) | |

|---|---|---|

| Health | ||

| Depression screening | ||

| Negative (PHQ-2 score <3) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive (PHQ-2 score ≥3) | 1.83 (1.14-2.93) | 1.86 (1.06-3.29) |

| Depression screening b —PHQ-2 score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.28 (1.13-1.45) | 1.36 (1.14-1.61) |

| Anxiety screening | ||

| Negative (GAD-2 score <3) | Reference | Reference |

| Positive (GAD-2 score ≥3) | 1.28 (0.85-1.95) | 0.75 (0.45-1.26) |

| Anxiety screening c —GAD-2 score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.11 (0.99-1.23) | 0.92 (0.79-1.07) |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | Reference | Reference |

| Poor/fair | 1.01 (0.61-1.65) | 0.66 (0.38-1.14) |

| Substance use behavior | ||

| Alcohol | ||

| Any alcohol use—past 12 months | 9.42 (5.70-15.56) | 10.90 (6.22-19.09) |

| Cannabis | ||

| Any cannabis use—past 12 months | 19.23 (11.95-30.95) | 20.15 (12.01-33.81) |

| Tobacco | ||

| Any tobacco use—past 12 months | 16.64 (8.48-32.66) | 17.70 (8.69-36.04) |

| How difficult is it for you to get nicotine vaping products if you want some? | ||

| Probably impossible/very/fairly difficult | Reference | Reference |

| Fairly/very easy | 3.95 (2.17-7.18) | 3.93 (2.11-7.33) |

| NA | 0.40 (0.22-0.74) | 0.42 (0.22-0.77) |

| How difficult is it for you to get cannabis (marijuana) if you want some? | ||

| Probably impossible/very/fairly difficult | Reference | Reference |

| Very/fairly easy | 4.00 (2.26-7.07) | 4.06 (2.23-7.38) |

| NA | 0.32 (0.16-0.62) | 0.32 (0.16-0.64) |

| Non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) practices | ||

| Based on what you’ve heard and know about COVID-19 how important is it to: stay 6 ft. apart? | ||

| Very important/important | Reference | Reference |

| Not/slightly/moderately important | 1.72 (0.99-2.96) | 1.70 (0.96-3.02) |

| Based on what you’ve heard and know about COVID-19 how important is it to: wear a mask covering your nose and mouth in the presence of people outside your home? | ||

| Very important/important | Reference | Reference |

| Not/slightly/moderately important | 3.44 (1.66-7.14) | 3.22 (1.50-6.93) |

| When outside your home in public, how regularly do you: Stay 6 ft. apart? | ||

| Always/usually | Reference | Reference |

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 1.74 (1.09-2.77) | 1.82 (1.11-2.98) |

| When outside your home in public, how regularly do you: Wear a mask covering your nose and mouth? | ||

| Always/usually | Reference | Reference |

| Never/rarely/sometimes | 3.11 (1.39-6.95) | 2.98 (1.29-6.84) |

| COVID-19 exposure and family impact scales (CEFIS) | ||

| CEFIS distress d | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.19 (0.98-1.43) | 1.03 (0.82-1.29) |

| CEFIS impact d | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.24 (1.02-1.51) | 1.09 (0.87-1.35) |

| CEFIS exposure d | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.06 (0.88-1.28) | 0.98 (0.80-1.20) |

| CEFIS impact items | ||

| How family/household members get along | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.50 (1.03-2.18) | 1.26 (0.84-1.90) |

| Physical wellbeing—eating | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.60 (1.09-2.36) | 1.40 (0.93-2.12) |

| Physical wellbeing—sleeping | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.56 (1.08-2.28) | 1.16 (0.77-1.76) |

| Physical wellbeing—substance use (smoking/vaping, drinking alcohol, cannabis (marijuana use), etc.) | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 9.80 (6.13-15.65) | 9.48 (5.79-15.52) |

| Emotional wellbeing—anxiety/worry | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.63 (1.03-2.56) | 1.36 (0.82-2.26) |

| Emotional wellbeing—mood | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.63 (1.05-2.53) | 1.29 (0.79-2.12) |

| Emotional wellbeing—loneliness | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.28 (0.83-1.96) | 0.98 (0.61-1.58) |

| Social wellbeing—relationships with friends | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 0.90 (0.60-1.34) | 0.77 (0.50-1.18) |

| Social wellbeing—romantic relationships or dating | ||

| A lot/A little better/NA or missing | Reference | Reference |

| A lot/a little worse | 1.33 (0.92-1.94) | 1.15 (0.77-1.71) |

CEFIS: COVID-19 Exposure and Family Impact Scale; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Significant odds ratios are highlighted in Bold.

The adjusted models controlled for age, sex, household composition, cohort, period of the survey, PHQ score (depression screening), and GAD score (anxiety screening).

The adjusted models controlled for age, sex, household composition, cohort, period of the survey, and GAD score (anxiety screening).

The adjusted models controlled for age, sex, household composition, cohort, period of the survey, and PHQ score (depression screening).

CEFIS Scores were centered around the mean in regression analyses.

COVID-19 Exposures and Impacts

Participants who vaped were more likely to report negative impacts of the pandemic on their family relationships (56.6% vs 46.5%; P = .034), eating habits (64.6% vs 53.2%; P = .015), sleeping patterns (54.3% vs 43.1%; P = .019), and their use of substances (54.9% vs 11.0%; P < .001; Table 1). Those who vaped also reported more anxiety/worry (81.1% vs 72.6%; P = .036), and worsening mood (78.9% vs 69.6%; P = .028; Table 1). Vaping was also associated with screening positive for depression (24.0% vs 14.7%; P = .011). There was no difference in perceptions of the pandemic’s impact on feelings of loneliness, quality of relationships with friends, or quality of romantic relationships, between participants who vaped and those who did not. After adjustment, only the negative impact on the use of substances and depression were significantly associated with past-year vaping (Table 2).

Compared to non-vaping peers, participants who vaped were less likely to report viewing social distancing, by staying 6 ft. away from others, as important (83.4% vs 89.6%; P = .050), to regularly maintain a distance of 6 feet apart from others when in public (76.0% vs 84.6%; P = .020), to view wearing a mask in public as important (87.4% vs 96.0%; P ≤ .001), and to report regular mask wearing (90.3% vs 96.7%; P = .004; Table 1). All of these associations, with the exception of the perception of the importance of staying 6 ft. apart, remained significant in adjusted analyses (Table 2).

Discussion

We found that vaping among AYA was associated with larger perceived negative impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic on emotional wellbeing and greater levels of other substance use. We found no evidence that vaping was protective against experiencing loneliness or worsening social relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, we found that youth who vaped were less likely to adhere to non-pharmaceutical measures put in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 compared to their non-vaping AYA peers.

In our study, AYA that reported vaping also reported greater negative pandemic impacts on their eating habits, sleeping patterns, substance use, level of anxiety/worry, and mood, which is consistent with previous work. 33 The relationships between vaping and greater emotional toll from the pandemic is likely bi-directional.34,35 Previous research has found that stressed humans and animals are more likely to self-administer substances. 36 Nicotine, cannabis, and alcohol may be used by some in the hopes it will relieve stress, however substance use37,38 is associated with later development of depression and anxiety. 9

Recent studies have indicated that female gender was a risk factor for poor mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. 19 Our study sample, which was predominantly female, may have been at higher risk for experiencing emotional distress during the study period, and thus our study sample was “enhanced” for this risk factor, potentially increasing the likelihood of finding an effect. However, our results did not indicate a positive effect of vaping, but rather suggested that negative mental/emotional health was more likely among youth who vaped, a finding that is consistent with other reports. 19

The discreet nature of vaping facilitates use at school and other public spaces. 39 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, some youth reported witnessing the use of vaping devices in public areas of their schools, including in the hallways and in their classrooms. 39 However, vaping in public during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic requires the removal of masks to facilitate use of the vaping device. Although there was no statistically significant difference in views on the importance of staying 6 ft. apart between the participants who vaped and those who did not vape in the adjusted analysis done in our study, there was statistically significant findings that those who vaped were still less likely to report that they actually stayed 6 ft. apart when outside their homes, were less likely to view mask wearing as important, and less likely to report wearing their masks over their nose and mouth when outside of their homes. This could be due to vaping interfering with social distancing and mask wearing.

Prior studies suggest that youth engaging in risk-taking behaviors such as vaping may be more inclined to participate in other risk-taking behaviors. 40 It is thus not surprising that in our study we found that youth who vaped were more likely to report inconsistent use of masks when in public during the pandemic and were less likely to engage in COVID-19 social distancing. Further, previous studies have indicated that many youths share vaping devices. 41 With respect to COVID-19, the social aspect of vaping and the sharing of devices may increase risk of COVID-19 exposure and infection. Thus, addressing vaping among AYA may be an important COVID-19 mitigation strategy.

Additionally, despite the legal federal minimum age to purchase e-cigarette devices being 21 years of age as of 2019, 42 those who vaped nicotine in our study were more likely to report that if they wanted access to nicotine products it was relatively easy to gain access to it. This is an important observation in that the mean age of our study population, 19.3 years, fell below this minimum. This suggests that tighter enforcement of e-cigarette regulations may be needed to protect the health of AYA.

Overall, vaping has been associated with a variety of health problems among AYA and while vaping may be a social activity, we found no evidence that it was protective of social/emotional health during the pandemic. On the contrary, while cross-sectional analyses cannot determine causation, vaping appears to be an indicator of increased risk for other substance use, 43 mood, eating, and sleep disorders. Moreover, youth who vape may be more likely to forgo protective strategies such as social distancing and masking, even when they view those measures as being important. As such, health care providers involved in the care of AYA should screen for vaping and related co-occurring risk behaviors and health problems to take advantage of the opportunity to also identify and treat substance use and possible co-occurring disorders.

Findings from this study should be taken in the context of limitations. As with many survey studies, the sampling frame, survey response rate, including retention from a prior longitudinal study as in this case, limit generalizability. In this study, participants from multiple clinics at a single institution in the United States were surveyed, and the sample was composed of primarily white, non-Hispanic/non-Latino, female participants, from 2-parent homes, factors that limit generalizability. Further, we used structured and validated self-report items and note that participant’s ability to recall may affect reporting as it covered a 12-month period. Further, the measure of vaping assessed vaping in the past 12 months which, for some participants, may have included time prior to COVID-19. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study also does not allow for assessment of causation. A longitudinal study could shed light on long term outcomes.

Conclusion

Despite the possible social nature of vaping, and the mental health benefits of maintaining social connections, we found no evidence that vaping afforded protection from adverse mental/emotional health effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given known risks associated with vaping, we encourage comprehensive screening of AYA for vaping and co-occurring health disorders, and other risk-taking behaviors. Addressing vaping may also be an important part of COVID-19 mitigation among this patient population as in-person classes and many social activities have resumed. This is especially important during seasons, and in climates, where the conditions lend themselves to fostering the easy transmission of COVID-19. Given the reported ease of access to substances, tighter enforcement of regulations aimed at limiting access to vaping products may be needed to better protect the health of AYA.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of clinician champions who facilitated access to their patient populations for survey research, including Drs. Katharine Garvey, Fatma Dedeoglu, and Laurie Fishman. Help with manuscript preparation was provided by Justin Chimoff, BSc.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Alicia Oliver drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and provided input on the data analysis, and revised and reviewed all drafts of the manuscript. Dr. Joe Kossowsky carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Machiko Minegishi assisted with data analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Sharon Levy reviewed data analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Elissa Weitzman conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated, and supervised data collection, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Levy serves as an expert for the litigation against JUUL. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by grant CNF20140273 from the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation. Joe Kossowsky was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (K01DA057374)

Compliance, Ethical Standards, and Ethical Approval: Ethical Approval was obtained from the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Role of Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2020: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2021. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED611736 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walley SC, Wilson KM, Winickoff JP, Groner J. A public health crisis: electronic cigarettes, vape, and JUUL. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20182741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones K, Salzman GA. The vaping epidemic in adolescents. Mo Med. 2020;117(1-2):56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017-2019. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1490-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miech RA, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG. Trends in reported marijuana vaping among US adolescents, 2017-2019. JAMA. 2020;323(5):475-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. 2020. Accessed July 29, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- 7.McLellan AT. Substance misuse and substance use disorders: why do they matter in healthcare? Trans Am Clin Climatol. 2017;128:112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lechner WV, Janssen T, Kahler CW, Audrain-McGovern J, Leventhal AM. Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Prev Med. 2017;96:73-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman BJ, McRae-Clark AL. Treatment of cannabis use disorder: current science and future outlook. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(5):511-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiloha R. Biological basis of tobacco addiction: implications for smoking-cessation treatment. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(4):301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker TD, Arnold MK, Ro V, Martin L, Rice TR. Systematic review of electronic cigarette use (vaping) and mental health comorbidity among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(3):415-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorfinkel L, Hasin D, Miech R, Keyes KM. The link between depressive symptoms and vaping nicotine in US adolescents, 2017-2019. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(1-2):133-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha V, Kraguljac A. Focus: preventive medicine: assessing the social influences, self-esteem, and stress of high school students who vape. Yale J Biol Med. 2021;94(1-2):95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong G, Bold KW, Cavallo DA, Davis DR, Jackson A, Krishnan-Sarin S. Informing the development of adolescent e-cigarette cessation interventions: a qualitative study. Addict Behav. 2021;114:106720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groom AL, Vu T-HT, Landry RL, et al. The influence of friends on teen vaping: a mixed-methods approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):6784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future Survey: High School and Youth Trends 2019. 2019. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/drugfacts-mtf.pdf

- 17.Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020;584(7820):257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature. 2020;584(7820):262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theberath M, Bauer D, Chen W, et al. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents: a systematic review of survey studies. SAGE Open Med. 2022;10:20503121221086712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruns N, Willemsen L, Stang A, et al. Pediatric ICU admissions after adolescent suicide attempts during the pandemic. Pediatrics. 2022;150(2):e2021055973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miech R, Leventhal A, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Patrick ME, Barrington-Trimis J. Trends in use and perceptions of nicotine vaping among US youth from 2017 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):185-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaiha SM, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Underage youth and young adult e-cigarette use and access before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw. 2020;3(12):e2027572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen N, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. Self-reported changes in cannabis vaping among US adolescents and young adults early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamblin M, Murawski C, Whittle S, Fornito A. Social connectedness, mental health and the adolescent brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:57-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitzman ER, Wisk LE, Lunstead J, Brogna M, Levy S. Effects of a patient-centered intervention to reduce alcohol use among youth with chronic medical conditions. J Adolesc Health. 2022;71(4):S24-S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy S, Weitzman ER, Marin AC, Magane KM, Wisk LE, Shrier LA. Sensitivity and specificity of S2BI for identifying alcohol and cannabis use disorders among adolescents presenting for primary care. Subst Abus. 2021;42(3):388-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy S, Wisk LE, Chadi N, Lunstead J, Shrier LA, Weitzman ER. Validation of a single question for the assessment of past three-month alcohol consumption among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:109026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy S, Tennermann N, Marin AC, et al. Safety protocols for adolescent substance use research in clinical settings. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(5):999-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz LA, Lewis AM, Alderfer MA, et al. COVID-19 exposure and family impact scales for adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr Psychol. 2022;47(6):631-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson LP, Rockhill C, Russo JE, et al. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a brief screen for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1097-e1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy S, Weiss R, Sherritt L, et al. An electronic screen for triaging adolescent substance use by risk levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):822-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kossowsky J, Weitzman ER. Instrumental substance use among youth with rheumatic disease—a biopsychosocial model. Rheum Dis Clin. 2022;48(1-2):51-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pacek LR, Martins SS, Crum RM. The bidirectional relationships between alcohol, cannabis, co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders with major depressive disorder: results from a national sample. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(2-3):188-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castellani B, Wedgeworth R, Wootton E, Rugle L. A bi-directional theory of addiction: examining coping and the factors related to substance relapse. Addict Behav. 1997;22(1-2):139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158(4):343-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard NR, Gwadz MV, Ritchie A, et al. A multi-method exploratory study of stress, coping, and substance use among high school youth in private schools. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner EF, Myers MG, McIninch JL. Stress-coping and temptation-coping as predictors of adolescent substance use. Addict Behav. 1999;24(6):769-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dai H. Youth observation of e-cigarette use in or around school, 2019. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(2):241-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh TS, Tolliver R, Reidmohr A, Lynch M. Youth vaping and associated risk behaviors—a snapshot of Colorado. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):689-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pepper JK, Coats EM, Nonnemaker JM, Loomis BR. How do adolescents get their e-cigarettes and other electronic vaping devices? Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(3):420-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Academy of Pediatrics. Tobacco 21: An Easy Way to Save Young Lives. 2021. Accessed January 21, 2023. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/tobacco-control-and-prevention/policy-and-advocacy/tobacco-21/

- 43.Moustafa AF, Rodriguez D, Pianin SH, Testa SM, Audrain-McGovern JE. Dual use of nicotine and cannabis through vaping among adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(1-2):60-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]