Key Points

Question

Does dapagliflozin reduce the risk of total episodes of worsening heart failure (HF; defined as hospitalization for HF or urgent HF visit requiring intravenous HF therapies) and cardiovascular death in patients with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure?

Findings

In this prespecified analysis of the DELIVER trial including 6263 patients, dapagliflozin reduced the risk of total HF events and cardiovascular death by 23%, and this was consistent across a range of subgroups, including across the spectrum of ejection fraction.

Meaning

In this study, dapagliflozin demonstrated no reduction in efficacy in reducing second or subsequent HF events.

This prespecified analysis of the DELIVER trial evaluates the effect of dapagliflozin on total (ie, first and recurrent) heart failure (HF) events and cardiovascular death among patients with HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction.

Abstract

Importance

In the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial, dapagliflozin reduced the risk of time to first worsening heart failure (HF) event or cardiovascular death in patients with HF with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (EF).

Objective

To evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin on total (ie, first and recurrent) HF events and cardiovascular death in this population.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this prespecified analysis of the DELIVER trial, the proportional rates approach of Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (LWYY) and a joint frailty model were used to examine the effect of dapagliflozin on total HF events and cardiovascular death. Several subgroups were examined to test for heterogeneity in the effect of dapagliflozin, including left ventricular EF. Participants were enrolled from August 2018 to December 2020, and data were analyzed from August to October 2022.

Interventions

Dapagliflozin, 10 mg, once daily or matching placebo.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The outcome was total episodes of worsening HF (hospitalization for HF or urgent HF visit requiring intravenous HF therapies) and cardiovascular death.

Results

Of 6263 included patients, 2747 (43.9%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 71.7 (9.6) years. There were 1057 HF events and cardiovascular deaths in the placebo group compared with 815 in the dapagliflozin group. Patients with more HF events had features of more severe HF, such as higher N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide level, worse kidney function, more prior HF hospitalizations, and longer duration of HF, although EF was similar to those with no HF events. In the LWYY model, the rate ratio for total HF events and cardiovascular death for dapagliflozin compared with placebo was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.67-0.89; P < .001) compared with a hazard ratio of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73-0.92; P < .001) in a traditional time to first event analysis. In the joint frailty model, the rate ratio was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.65-0.81; P < .001) for total HF events and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.72-1.05; P = .14) for cardiovascular death. The results were similar for total HF hospitalizations (without urgent HF visits) and cardiovascular death and in all subgroups, including those defined by EF.

Conclusions and Relevance

In the DELIVER trial, dapagliflozin reduced the rate of total HF events (first and subsequent HF hospitalizations and urgent HF visits) and cardiovascular death regardless of patient characteristics, including EF.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03619213

Introduction

Patients with heart failure (HF) are frequently hospitalized for decompensation of HF. While the risk of death declines as ejection fraction (EF) increases, the risk of hospitalization for HF remains relatively static across the spectrum of EF.1 Therefore, repeated hospitalizations account for a greater proportion of the burden of disease in patients with HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF) or HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) compared with HF with reduced EF (HFrEF). These repeated hospitalizations are the major driver of the burden of HF on patients and health care systems. In HFmrEF and HFpEF, as with HFrEF, these repeated hospitalizations are also associated with a higher subsequent risk of death.2 The gradient of risk is linear; as the number of repeated hospitalizations increases, the subsequent risk of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality also increases.3

Recognizing the importance of repeated hospitalizations in patients with HF, analysis of repeated or total hospitalizations for HF was the primary outcome in a trial of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF.4 More recently, there has also been a recognition that urgent visits for treatment for HF are associated with worse outcomes, and these events have been incorporated into time to first event composites along with HF hospitalizations.5,6,7 Trials of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin were designed with a primary outcome of time to first worsening HF event (first hospitalization for HF or urgent HF visit) or cardiovascular death, in recognition of the prognostic impact of both of these nonfatal events.8,9 However, to our knowledge, the trials of SGLT2 inhibitors in HF still only examine the total number of hospitalizations for HF as a secondary outcome7,10,11,12 and not the effect of treatment on the total burden of this condition reflected by the full spectrum of HF events from urgent visits through to cardiovascular death. In this prespecified analysis, we describe in detail the efficacy of dapagliflozin on total HF events, ie, first and subsequent HF hospitalizations or urgent visits for HF and cardiovascular deaths, in the population with HFmrEF or HFpEF enrolled in the Dapagliflozin Evaluation to Improve the Lives of Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure (DELIVER) trial.10

Methods

In the DELIVER trial, patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF, defined as HF with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II to IV and an EF greater than 40%, were randomized to the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin, 10 mg, once daily or matching placebo in a double-blind, event-driven randomized clinical trial. The design, baseline characteristics, and primary results have been published previously.8,10,13 The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1, and the statistical analysis plan can be found in Supplement 2. The ethics committees of all participating sites approved the protocol, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Study Patients

Patients were enrolled if they had HF with a left ventricular EF (LVEF) greater than 40%, 40 years or older, HF of NYHA class II to IV, had an elevated N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level of 300 pg/mL or greater (greater than 600 pg/mL if atrial fibrillation was present on electrocardiography at enrollment), and who were receiving usual therapy. Patients who were hospitalized or were within 30 days of hospitalization for HF and patients ambulant in the community were eligible for enrollment. In addition, patients with a previous measure of LVEF of 40% or less were eligible for enrollment. The main exclusions to enrollment were a history of type 1 diabetes, symptomatic hypotension or systolic blood pressure less than 95 mm Hg, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 25 mL/min/1.73 m2. The complete list of exclusion criteria has been published.8 Patients were assigned a race subgroup on the case report form based on their self-identification. The prespecified groups were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, or other race, in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration guidance.

HF Events

The primary outcome of the DELIVER trial was the composite of worsening HF (HF hospitalization or urgent visit for HF requiring intravenous therapy) or cardiovascular death, whichever occurred first. In the present analyses, we explored the predefined secondary end point of total (first and repeated) worsening episodes of HF and cardiovascular deaths. Hospitalizations or urgent visits occurring on the day of death were not counted in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized baseline characteristics with means and SDs, medians and IQRs, or counts and percentages. Total HF events were examined using 2 methods that were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan, with the analyses stratified by baseline diabetes status.

The first prespecified method used was the semiparametric proportional-rates model described by Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (LWYY).14 This is an extension of the proportional hazards model. The LWYY model uses a robust SE estimator to account for the interdependence of events within an individual. We specified in the statistical analysis plan that the 2 components in the composite end point (total number of HF events and cardiovascular deaths) would be analyzed separately to quantify the respective treatment effects and check the consistency between the composite and the components. Subgroup estimates, using the subgroups predefined for the primary efficacy analysis of the trial, were also calculated using the LWYY method and the interaction term tested. EF was examined using prespecified categories and as a continuous variable. EF was modeled as a restricted cubic spline with 3 knots based on the best-fitting spline according to the Akaike information criterion. The knots were placed at EF of 45%, 54%, and 70%.

The second statistical method for the analysis of total HF events prespecified in the statistical analysis plan was the joint frailty model.15 This method accounts for the association between HF events and subsequent mortality and the competing risk of mortality on HF events. The advantage of the joint frailty model is that it allows a distinct treatment effect to be estimated for each of the individual outcomes (HF events and cardiovascular death) while taking account of the association between the 2 through a common frailty term. The frailty is a random term specific to a participant that accounts for some patients being at higher risk (having large frailty) than others (who have smaller frailty). Rate ratios for the effect of dapagliflozin on HF events and cardiovascular death are provided separately for the joint model. Total hospitalizations were plotted using nonparametric estimates of the marginal mean of the cumulative number of HF hospitalization rates over time, allowing for cardiovascular death as the terminal event following the approach of Ghosh and Lin.16 Finally, in a post hoc exploratory analysis, we used a model-free area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (AUC) approach to describe the efficacy of the randomized therapy.17 This AUC-based approach does not rely on any of the assumptions of the model-based methods, such as the LWYY or joint frailty models described above. In this method, the Ghosh-Lin cumulative event curves were constructed using HF events and cardiovascular death as events of interest and noncardiovascular death as competing risk.16 The integrated AUC for each treatment arm was used to measure the cumulative morbidity and mortality experienced by each randomized group. The absolute difference and relative ratio of the resulting AUCs were then estimated.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Our exploratory analyses of AUC were conducted using R version 4.2.1 (The R Foundation). P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant, and all P values were 2-tailed. Continuous variables were compared across groups using analysis of variance and categorical variables using χ2 tests.

Results

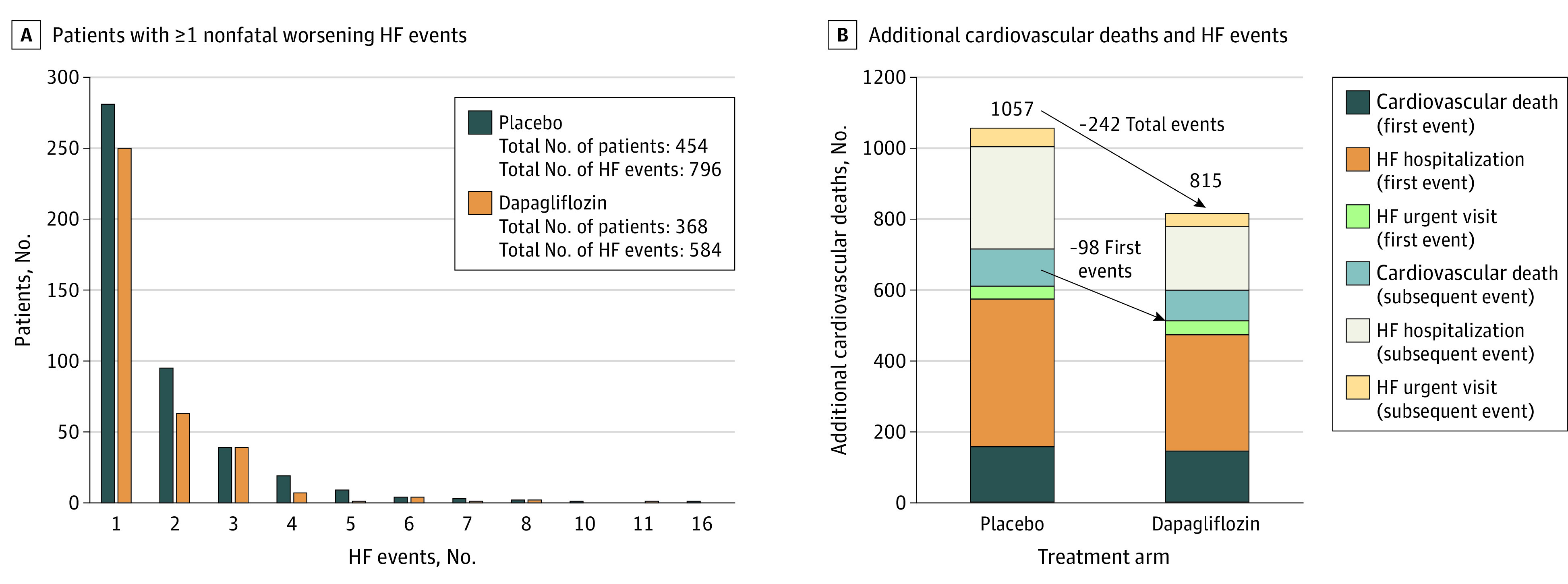

Of 6263 included patients, 2747 (43.9%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 71.7 (9.6) years. Among 6263 patients randomized in the DELIVER trial, during a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.3 (1.7-2.8) years, a total of 1380 nonfatal worsening HF events (urgent visits or hospital admissions) occurred in 822 patients (Figure 1). Most patients had 1 or 2 worsening events during follow-up (median [IQR] number of worsening HF events in both groups was 1 [1-2]), with a maximum of 16 events. The additional nonfatal HF events and cardiovascular deaths occurring after a first HF event are shown in Figure 1. There were an additional 447 events in the placebo groupsand an additional 303 events in the dapagliflozin group. There were 212 fewer total worsening HF events (199 fewer total HF hospitalizations and 13 fewer urgent visits for HF) and 30 fewer total cardiovascular deaths in the dapagliflozin group compared with the placebo group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total Number of Heart Failure (HF) Events and Cardiovascular Deaths.

A, Patients with 1 or more worsening HF event (defined as urgent visits or hospital admissions for HF). B, Additional cardiovascular deaths and HF events added to first events in the dapagliflozin and placebo groups.

Baseline Characteristics

Of the patients who had a nonfatal worsening HF event, the patients with 1 or more total events were older and more likely to be men (Table). They were also more likely to be from Asia and North America but less likely to be from Latin America. Participants with 2 or more HF events had higher heart rates, body mass index, and NT-proBNP and hemoglobin A1c levels. They also had worse kidney function, with higher creatinine levels and lower eGFR, and a larger proportion had an eGFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. With regards to HF characteristics, patients with multiple HF events were more likely to be in a higher NYHA class, had slightly longer duration of HF, greater prevalence of prior hospitalization for HF, or had been randomized in the hospital or within 30 days of hospitalization. They also had worse Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire total symptom, clinical summary, and overall summary scores. EF was similar in the patients with and without multiple HF events, and the proportion with a previous measurement of EF less than 40% was not different. Patients with multiple HF events also had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, with higher rates of atrial fibrillation, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patients with multiple HF events were more likely to be treated with diuretics and less likely to be receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers but more likely to be receiving an oral anticoagulant or have an implanted cardiac device.

Table. Baseline Characteristics by Number of Heart Failure (HF) Events.

| Characteristic | HF events, No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 5441) | 1 (n = 531) | ≥2 (n = 291) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71.6 (9.5) | 71.5 (9.6) | 72.9 (10.1) | .06 |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 2416 (44.4) | 216 (40.7) | 115 (39.5) | .08 |

| Men | 3025 (55.6) | 315 (59.3) | 176 (60.5) | |

| Racea | ||||

| Asian | 1105 (20.3) | 102 (19.2) | 67 (23.0) | <.001 |

| Black or African American | 130 (2.4) | 15 (2.8) | 14 (4.8) | |

| White | 3829 (70.4) | 402 (75.7) | 208 (71.5) | |

| Other race | 377 (6.9) | 12 (2.3) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Europe and Saudi Arabia | 2595 (47.7) | 266 (50.1) | 144 (49.5) | <.001 |

| Asia | 1064 (19.6) | 98 (18.5) | 64 (22.0) | |

| Latin America | 1099 (20.2) | 66 (12.4) | 16 (5.5) | |

| North America | 683 (12.6) | 101 (19.0) | 67 (23.0) | |

| Physiological measures | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 128.2 (15.2) | 127.8 (15.8) | 128.8 (17.3) | .66 |

| Heart rate, mean (SD), beats per minute | 71.2 (11.7) | 73.1 (11.8) | 73.3 (12.2) | <.001 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)b | 29.7 (6.0) | 30.3 (6.5) | 31.2 (6.4) | <.001 |

| NT-proBNP, median (IQR), pg/mL | 961 (602-1644) | 1433 (800-2695) | 1500 (839-2618) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD), % | 6.6 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.6) | <.001 |

| Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL | 101.0 (30.2) | 109.4 (34.2) | 116.5 (35.5) | <.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.7 (19.0) | 57.9 (20.0) | 53.6 (18.9) | <.001 |

| <60 | 2586 (47.5) | 296 (55.7) | 188 (64.6) | <.001 |

| ≥60 | 2854 (52.5) | 235 (44.3) | 103 (35.4) | |

| HF-related characteristics | ||||

| Prior LVEF measurement ≤40% | 990 (18.2) | 107 (20.2) | 54 (18.6) | .54 |

| Randomized during or within 30 d of a HF hospitalization | 497 (9.1) | 96 (18.1) | 61 (21.0) | <.001 |

| Duration of HF | ||||

| 0-3 mo | 497 (9.1) | 51 (9.6) | 20 (6.9) | .02 |

| >3-6 mo | 536 (9.9) | 40 (7.5) | 16 (5.5) | |

| >6-12 mo | 747 (13.7) | 58 (10.9) | 37 (12.7) | |

| >1-2 y | 859 (15.8) | 80 (15.1) | 56 (19.2) | |

| >2-5 y | 1363 (25.1) | 132 (24.9) | 74 (25.4) | |

| >5 y | 1434 (26.4) | 170 (32.0) | 88 (30.2) | |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 54.2 (8.8) | 53.9 (8.7) | 53.5 (8.4) | .26 |

| LVE, % | ||||

| ≤49 | 1822 (33.5) | 189 (35.6) | 105 (36.1) | .65 |

| 50-59 | 1965 (36.1) | 184 (34.7) | 107 (36.8) | |

| ≥60 | 1654 (30.4) | 158 (29.8) | 79 (27.1) | |

| NYHA class | ||||

| I, II | 4169 (76.6) | 355 (66.8) | 190 (65.3) | <.001 |

| III, IV | 1272 (23.4) | 176 (33.2) | 101 (34.7) | |

| KCCQ, median (IQR) | ||||

| Total symptom score | 72.9 (56.3-88.5) | 67.7 (50.0-83.3) | 66.7 (46.9-83.3) | <.001 |

| Clinical summary score | 71.1 (55.6-85.4) | 65.3 (47.9-80.0) | 65.3 (47.2-79.9) | <.001 |

| Overall summary score | 69.2 (53.8-83.3) | 63.8 (47.1-77.9) | 62.5 (45.0-80.0) | <.001 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Hospitalization for HF | 2071 (38.1) | 289 (54.4) | 179 (61.5) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 3023 (55.6) | 339 (63.8) | 190 (65.3) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 497 (9.1) | 60 (11.3) | 40 (13.7) | .01 |

| Angina | 1302 (23.9) | 126 (23.7) | 69 (23.7) | .99 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1416 (26.0) | 142 (26.7) | 81 (27.8) | .75 |

| Hypertension | 4813 (88.5) | 476 (89.6) | 264 (90.7) | .38 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2370 (43.6) | 276 (52.0) | 160 (55.0) | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 554 (10.2) | 96 (18.1) | 42 (14.4) | <.001 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Loop diuretic | 4086 (75.1) | 466 (87.8) | 259 (89.3) | <.001 |

| Other diuretic (excluding loop and MRA) | 1212 (22.3) | 77 (14.5) | 54 (18.6) | <.001 |

| ACEI/ARB | 3976 (73.1) | 380 (71.6) | 187 (64.5) | .005 |

| ARNI | 250 (4.6) | 29 (5.5) | 22 (7.6) | .05 |

| β-Blocker | 4521 (83.1) | 421 (79.3) | 235 (81.0) | .06 |

| MRA | 2321 (42.7) | 232 (43.7) | 114 (39.3) | .46 |

| Digoxin | 252 (4.6) | 28 (5.3) | 16 (5.5) | .65 |

| Antiplatelet | 2310 (42.5) | 194 (36.5) | 126 (43.4) | .03 |

| Anticoagulant | 2881 (53.0) | 325 (61.2) | 176 (60.7) | <.001 |

| Pacemaker | 554 (10.2) | 57 (10.7) | 51 (17.5) | <.001 |

| CRT-P/CRT-D | 84 (1.5) | 6 (1.1) | 10 (3.4) | .03 |

| ICD/CRT-D | 136 (2.5) | 21 (4.0) | 11 (3.8) | .07 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronisation therapy–defibrillator; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronisation therapy–pacemaker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide level; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

SI conversion factor: To convert creatinine to µmol/L, multiply by 88.4.

Patients were assigned a race subgroup on the case report form based on their self-identification. The prespecified groups were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, or other race, in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration guidance.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Effect of Dapagliflozin on Total HF Events and Cardiovascular Deaths

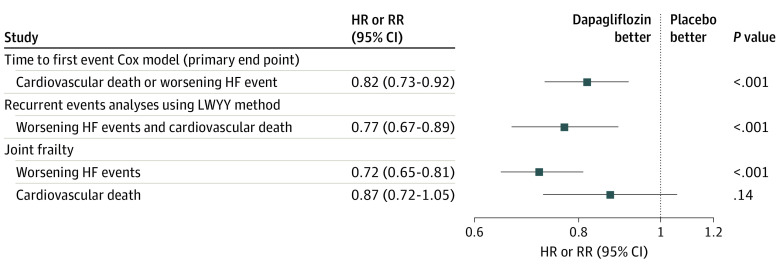

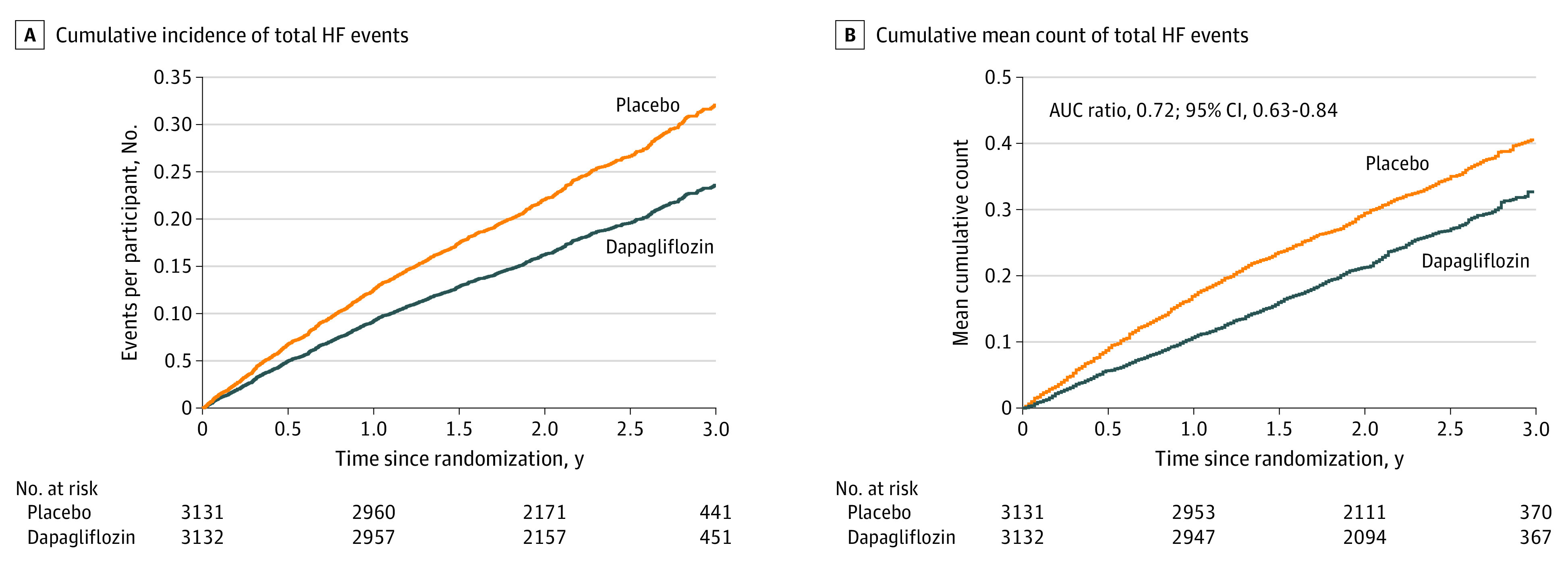

The rate of total (first and repeated) HF events and cardiovascular death was 15.3 per 100 patient-years in the placebo group and 11.8 per 100 patient-years in the dapagliflozin group, a reduction of 3.5 events per 100 patient-years of follow-up. The cumulative rate of total HF events with cardiovascular death as a competing risk was lower in the dapagliflozin group compared with the placebo group when plotted according to the method of Ghosh and Lin (Figure 2).16 The rate ratio from the LWYY model for total HF events and cardiovascular death was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.67-0.89; P < .001) compared with a hazard ratio of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.73-0.92; P < .001) for the traditional time to first event composite of worsening HF event or cardiovascular death (Figure 3). When the constituents of the total worsening HF events and cardiovascular deaths composite were examined, there was a reduction in total HF events, with a rate ratio of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.62-0.87; P < .001) but not in cardiovascular death (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.74-1.05; P = .17). In the joint frailty model, the rate ratio was 0.72 (95% CI, 0.65-0.81; P < .001) for HF events and 0.87 (95% CI, 0.72-1.05; P = .14) for cardiovascular death (Figure 3). As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the effect of dapagliflozin on total HF events and all deaths using the LWYY method, which found a similar result (rate ratio, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72-0.92), as well as using the joint frailty model, which was also similar (total HF events: rate ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81; all-cause death: rate ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence and Mean Count of Total Heart Failure (HF) Events.

A, Cumulative incidence of total HF events with cardiovascular death as a competing risk, plotted using the method of Ghosh and Lin.16 B, Cumulative mean count of total HF events and cardiovascular deaths with noncardiovascular deaths as a competing risk. AUC indicates area under the receiver operator characteristic curve.

Figure 3. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on First Heart Failure (HF) Events or Cardiovascular Death.

HR indicates hazard ratio; LWYY, Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying14; RR, rate ratio.

In a post hoc analysis, compared with patients with no HF event (HF hospitalization or urgent HF visit), the hazard of subsequent death was 1.67 (95% CI, 0.90-3.12) in those whose first event was an urgent HF visit and 5.70 (95% CI, 4.95-6.56) in those whose first event was an HF hospitalization. Compared with patients who had an HF hospitalization as their first event, the risk of death in patients where the first event was an urgent visit for HF was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.16-0.57). Therefore, the risk of death in a patient whose first event was an urgent HF visit was higher than patients who experienced no events but lower than that of patients whose first event was an HF hospitalization.

To allow comparison with prior trials of SGLT2 inhibitors in HF, we also examined the outcome of total HF hospitalizations, ie, without urgent visits for HF. There were 508 HF hospitalizations in total in the dapagliflozin group and 707 in the placebo group. When a composite of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular deaths was examined using the LWYY approach (rate ratio, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.66-0.88; P < .001) and in a joint frailty model (rate ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80; P < .001), the findings were similar to the analysis of total HF events.

The 2 analytic procedures are valid when their model assumptions are met. For example, the LWYY assumes that the 2 curves in Figure 2A would be proportional over the entire study period. To relax those model constrains, we conducted a robust, model assumption–free analysis for the multiple outcomes. Specifically, we used the mean cumulative count AUC in Figure 2B as a summary measure as a total disease burden, which is the total event-free time lost to HF and cardiovascular-death. The larger the AUC, the worse the treatment. In this exploratory post hoc analysis, with 36 months of follow-up, the AUC was 5.7 months for the dapagliflozin group and 7.8 months in the placebo group (P < .001) (Figure 2). This corresponds to an absolute increase of 2.2 months (95% CI, 1.2-3.2) and a rate ratio of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.63-0.84) for dapagliflozin compared with placebo, a 28% reduction in the cumulative burden of HF events and cardiovascular death over time, favoring dapagliflozin. These results support those by the prespecified procedures.

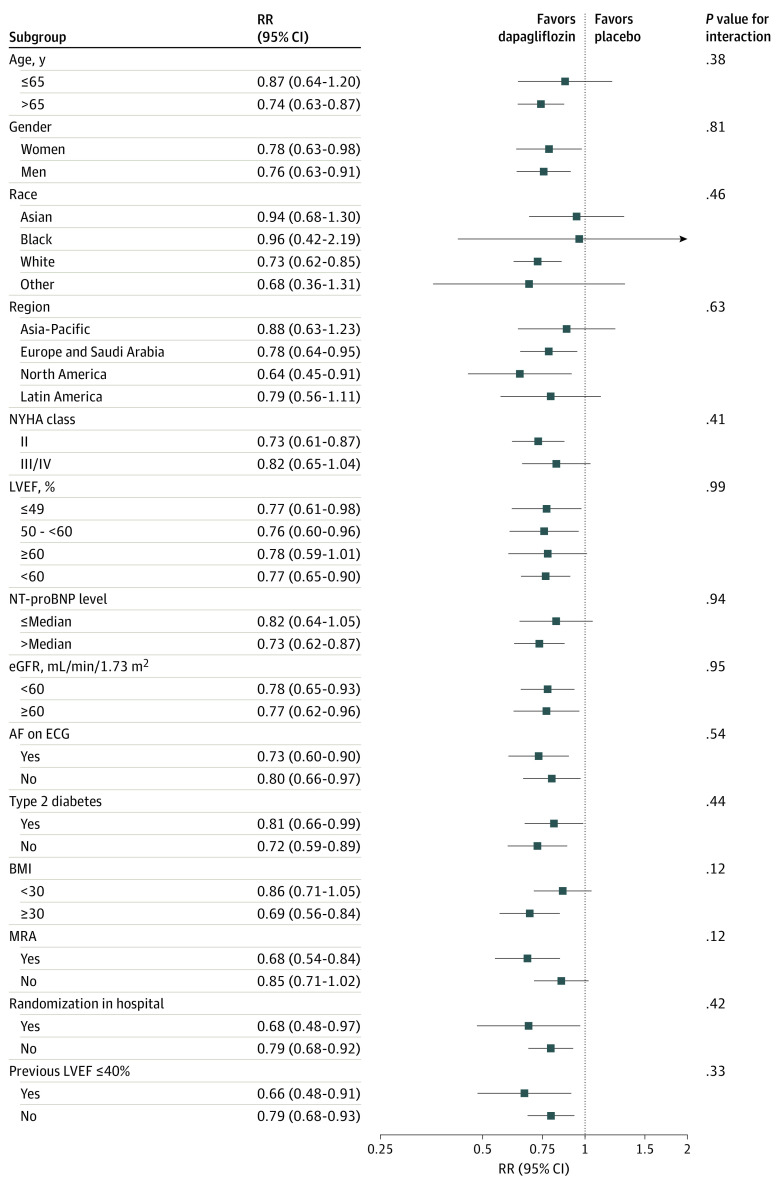

Efficacy of Dapagliflozin on Total HF Events by Subgroups

The effect of dapagliflozin on total HF events and cardiovascular deaths did not differ across any of the predefined subgroups (Figure 4). There was no evidence of treatment heterogeneity in those with and without an improved EF or according to whether they were randomized within 30 days of hospitalization. In particular, there was no evidence of treatment heterogeneity by LVEF at baseline. When the interaction was modeled with EF as a continuous variable, using a restricted cubic spline, the rate ratio remained less than 1, in favor of dapagliflozin, across the entire EF spectrum when analyzed using the LWYY model (eFigure in Supplement 3).

Figure 4. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Total Heart Failure Events and Cardiovascular Deaths in the Prespecified Subgroups.

Analyses were conducted using the Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying method.14 AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ECG, electrocardiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide level; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RR, rate ratio.

Discussion

In patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF, dapagliflozin reduced the risk of total HF events, ie, repeated in addition to first events. This benefit was observed in all the prespecified DELIVER subgroups and across the spectrum of EF. The characteristics associated with multiple HF events in this population with HFmrEF or HFpEF were similar to those in patients with HFrEF experiencing multiple hospitalizations.18

The reduction in burden of total HF events with dapagliflozin was evident regardless of the method used to analyze the total events and whether we examined total HF events including urgent HF visits or HF hospitalizations without urgent visits. The point estimates were more favorable to that obtained in the time to first event analysis, which was the primary outcome of the DELIVER trial,10 ie, dapagliflozin demonstrated no reduction in efficacy in reducing second or subsequent events. The estimates were also consistent with other trials of SLGT2 inhibitors in patients with HFmrEF HFpEF. In the Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved) trial,12 the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin reduced the rate of total HF hospitalizations by 27% (rate ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61-0.88; P < .001) using the joint frailty approach (compared with 0.71 [95% CI, 0.63-0.80; P < .001] using the same outcome and model in the DELIVER trial).10 In a separate analysis of the DELIVER trial, we also examined if this reduction in total HF events was also observed for all-cause hospitalizations and found that there was a similar but smaller relative risk reduction of 11%.19 The observation that the benefits of dapagliflozin were consistent across the range of EF is important, as an earlier pooled analysis of total HF hospitalizations in the EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved trials reported that the effect of empagliflozin on total HF hospitalizations appeared to diminish at higher EFs.20 We did not see any evidence of an attenuation of the benefit of dapagliflozin on total HF events at higher EFs in this analysis or for total HF hospitalizations in our pooled analysis.21 We also found that the elevated risk for subsequent death in a patient whose first event was an urgent HF visit, compared with a patient who did not have any worsening HF event, was elevated, in keeping with reports from HFrEF trials.5,22 Furthermore, we found that although urgent HF visits were associated with a higher risk of death, the excess risk was not as high as in patients in whom the first event experienced during follow-up was an HF hospitalization, in keeping with the findings of a similar analysis in the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB Global Outcomes in HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (PARAGON-HF) trial.6

As most prior trials enrolling patients with an EF greater than 40% have been neutral, there are few data with which to compare the relative efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in reducing total HF events. A post hoc analysis of the Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity–Preserved (CHARM-Preserved) trial, which enrolled patients with an EF greater than 40%, suggested that candesartan reduced total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death using a negative binomial model.23 In that analysis, candesartan reduced total HF hospitalizations by 25%, ie, the rate ratio for total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.62-0.91; P = .003). This post hoc analysis appeared to provide enough power to detect a treatment effect that was not evident in a time to first event analysis. In theory, total events should require a smaller sample size to demonstrate a treatment effect, as not only are subsequent nonfatal HF events counted but cardiovascular deaths that occur after these events are also counted (whereas both are ignored after a first HF event in a traditional time to first event analysis). In our trial, these repeated events contributed a further 193 deaths and 557 HF events that would otherwise have been ignored. Consequently, power calculations in the setting of total events are more complex, and factors such as heterogeneity of patient risk have to be incorporated, which is not currently part of routine sample size estimation strategies.24 However, use of total HF events as a primary outcome may result in a smaller sample size than is needed for a time to first event primary end point (or provide more power for secondary total events end points in trials powered for a time to first event primary outcome).

One attraction of recurrent or total events analysis is that they describe the full burden of disease and are potentially more meaningful to patients, representing the full disease experience. Therefore, describing reductions in total events may be helpful to explain treatment effects to patients. Explaining treatment efficacy is difficult in a clinical setting, and it is well known that relative risks are poorly understood by patients and by some clinicians. Other methods of expressing treatment benefits, such as the number needed to treat, are equally, if not more difficult, in the setting of total events.25 We reported that the AUC ratio for dapagliflozin vs placebo was 0.72, not dissimilar to the estimates from the conventional model-based approaches that we had prespecified. Although the relative risk reduction can be described as a ratio, perhaps more usefully the absolute risk reduction of 2.2 months over a 3-year period is easily explained to clinicians and patients, ie, a gain of 2.2 months of event-free survival. This absolute risk reduction with the accompanying time scale is a directly interpretably into clinically relevant terms for the patient. Simulation studies of power calculations using this approach suggest that sample sizes based on time to first events may be 20% larger than samples based on an AUC.17 The results that we observed using the AUC method (which is an extension of the restricted mean survival time used in multiple disease areas26,27,28,29) were consistent with the more traditional model-based approaches to analyzing total events. The technique may be useful in situations where model assumptions are not met, as the approach does not require a statistical model to be constructed and could be used in addition to other metrics, such as days alive and out of hospital.30

Limitations

This study has limitations. As with any clinical trial, follow-up was limited. Therefore, we do not know what the full lifetime burden of HF events or deaths was in each treatment group and how this may affect the treatment benefit in the longer term. Patients were selected according to specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, and our findings may not apply to all patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF in the broader population. Hospitalization rates vary widely by country and health care system, and patients were enrolled in 20 countries; however, there was no heterogeneity of treatment effect according to geographic region in the subgroup analysis.

Conclusions

In summary, among patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF, dapagliflozin reduced the risk of total (first and recurrent) HF events or cardiovascular deaths compared with placebo. HF events are common and preventable, and the efficacy of dapagliflozin in reducing the number of these events is consistent across a broad range of subgroups and across the spectrum of EF.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Total HF Events and Cardiovascular Deaths, Showing the Interaction With Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Modelled as a Restricted Cubic Spline From the Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (LWYY) Model

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, L Claggett B, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in heart failure. Circulation. 2020;141(5):352-361. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, et al. ; Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) Investigators . Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1482-1487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindmark K, Boman K, Stålhammar J, et al. Recurrent heart failure hospitalizations increase the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure in Sweden: a real-world study. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(3):2144-2153. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. ; PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1609-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okumura N, Jhund PS, Gong J, et al. ; PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees* . Importance of clinical worsening of heart failure treated in the outpatient setting: evidence from the Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure Trial (PARADIGM-HF). Circulation. 2016;133(23):2254-2262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaduganathan M, Cunningham JW, Claggett BL, et al. Worsening heart failure episodes outside a hospital setting in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the PARAGON-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9(5):374-382. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. ; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995-2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon SD, de Boer RA, DeMets D, et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved and mildly reduced ejection fraction: rationale and design of the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(7):1217-1225. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMurray JJV, DeMets DL, Inzucchi SE, et al. ; DAPA-HF Committees and Investigators . A trial to evaluate the effect of the sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (DAPA-HF). Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(5):665-675. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, et al. ; DELIVER Trial Committees and Investigators . Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(12):1089-1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. ; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators . Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1413-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. ; EMPEROR-Preserved Trial Investigators . Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1451-1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with HF with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: DELIVER trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10(3):184-197. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2000;62(4):711-730. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers JK, Yaroshinsky A, Pocock SJ, Stokar D, Pogoda J. Analysis of recurrent events with an associated informative dropout time: application of the joint frailty model. Stat Med. 2016;35(13):2195-2205. doi: 10.1002/sim.6853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh D, Lin DY. Nonparametric analysis of recurrent events and death. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):554-562. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claggett BL, McCaw ZR, Tian L, et al. Quantifying treatment effects in trials with multiple event-time outcomes. NEJM Evid. Published online June 30, 2022. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jhund PS, Ponikowski P, Docherty KF, et al. Dapagliflozin and recurrent heart failure hospitalizations in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of DAPA-HF. Circulation. 2021;143(20):1962-1972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.053659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund P, et al. Dapagliflozin and all-cause hospitalizations in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(10):1004-1006. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler J, Packer M, Filippatos G, et al. Effect of empagliflozin in patients with heart failure across the spectrum of left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(5):416-426. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jhund PS, Kondo T, Butt JH, et al. Dapagliflozin across the range of ejection fraction in patients with heart failure: a patient-level, pooled meta-analysis of DAPA-HF and DELIVER. Nat Med. 2022;28(9):1956-1964. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01971-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Anand I, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on outpatient worsening of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a prespecified analysis of DAPA-HF. Circulation. 2020;142(17):1623-1632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers JK, Pocock SJ, McMurray JJV, et al. Analysing recurrent hospitalizations in heart failure: a review of statistical methodology, with application to CHARM-Preserved. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16(1):33-40. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claggett B, Pocock S, Wei LJ, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Comparison of time-to-first event and recurrent-event methods in randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 2018;138(6):570-577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook RJ. Number needed to treat for recurrent events. J Biom Biostat. 2013;4(3). doi: 10.4172/2155-6180.1000167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A’Hern RP. Restricted mean survival time: an obligatory end point for time-to-event analysis in cancer trials? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(28):3474-3476. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DH, Li X, Bian S, Wei LJ, Sun R. Utility of restricted mean survival time for analyzing time to nursing home placement among patients with dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034745. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCaw ZR, Tian L, Vassy JL, et al. How to quantify and interpret treatment effects in comparative clinical studies of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(8):632-637. doi: 10.7326/M20-4044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCaw ZR, Tian L, Wei J, et al. Choosing clinically interpretable summary measures and robust analytic procedures for quantifying the treatment difference in comparative clinical studies. Stat Med. 2021;40(28):6235-6242. doi: 10.1002/sim.8971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y, Lawrence J, Stockbridge N. Days alive out of hospital in heart failure: insights from the PARADIGM-HF and CHARM trials. Am Heart J. 2021;241:108-119. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure. Effect of Dapagliflozin vs Placebo on Total HF Events and Cardiovascular Deaths, Showing the Interaction With Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Modelled as a Restricted Cubic Spline From the Lin, Wei, Yang, and Ying (LWYY) Model

Data Sharing Statement