Abstract

Physician burnout has been increasing in the United States, especially in primary care, and the use of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) is a prominent contributor. This review article summarizes findings from a PubMed literature search that shows the significant contributors to EHR-related burnout may be documentation and clerical burdens, complex usability, electronic messaging and inbox, cognitive load, and time demands. Documentation requirements have escalated and have inherently changed from paper-based records. Many clerical tasks have also shifted to become additional physician responsibilities. When considering factors of efficiency, effectiveness, and user satisfaction, EHRs overall have an inferior usability score when compared to other technologies. The volume and organization of data along with alerts and complex interfaces require a substantial cognitive load and result in cognitive fatigue. Patient interactions and work-life balances are negatively affected by the time requirements of EHR tasks during and after clinic hours. Patient portals and EHR messaging have created a separate source of patient care outside of face-to-face visits that is often unaccounted productivity and not reimbursable.

Keywords: electronic health record, electronic medical record, burnout

Introduction

Burnout

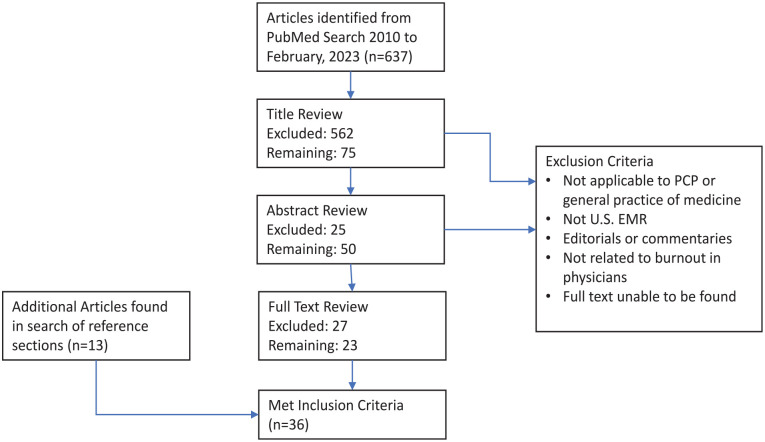

Physician burnout is prominent and manifests as a chronic stress response with components of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, or impaired feelings of accomplishment. 1 Figure 1 shows the prevalence of at least one symptom of burnout from a surveys of U.S. physicians in 4 periods from 2011 to 2021. 2 The consequences of this burnout to healthcare may be expressed as major medical errors, poor quality of care, safety incidents, reduced patient satisfaction, and primary-care workforce turnover.3-5 Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are a significant source of burnout along with varying combinations of time pressures, chaotic work environments, low control of pace, family responsibilities, COVID-19 pandemic stressors.1,2

Figure 1.

Prevalence of at least one symptom of burnout among U.S. physicians.

Source: From Shanafelt et al. 8

EHR and Burnout

Nearly 80% of hospitals 6 and 86% 7 of ambulatory clinics in the United States have implemented an EHR as of 2015 and 2017, respectively, and the adoption rates have likely increased significantly since then. As would be expected, the workflows and dynamics of providing healthcare have changed and will continue to adapt in the transition from paper-based records. A consequence of this evolution has been enhanced stress for providers. In fact, the prevalence of physician burnout has been increasing in all specialties in recent years with the highest levels reaching almost 50% in primary care in the United States. 8 The current state of the EHR is frequently pinpointed by physicians as the single most important stressor in patient care, 9 and nearly 75% with burnout symptoms identify the EHR as a source. 10

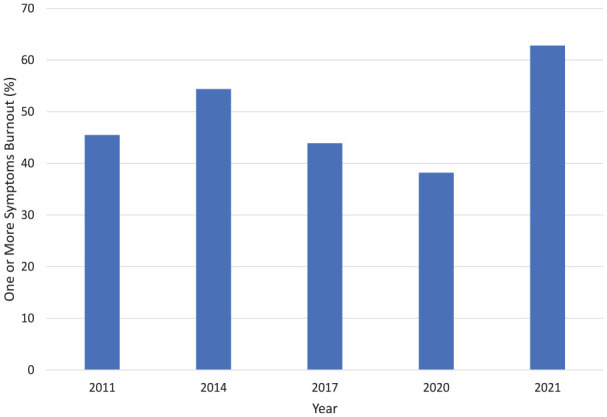

Billing and documentation have been the primary drivers of EHR design, not patient needs and health management.11,12 Physicians have acquired more administrative tasks, and, as a result, daily effort, workflow, and patient interactions have fundamentally changed. 12 In a 2018 national survey of 521 primary care providers (PCPs) by The Harris Poll on behalf of Stanford Medicine, half of PCPs believe that EHRs impair clinical effectiveness. 13 Nearly half (44%) also view the principle utility of EHRs as simply data storage, while only 3% see the primary value in disease management and prevention. 13 Ultimately, 59% of PCPs believe EHRs need a complete overhaul. 13 Figure 2 represents the prevalence of several EHR burnout characteristics from surveys. The goal of this literature review is to identify and characterize the specific aspects of EHR workflows that contribute to burnout.

Figure 2.

Physician views on EHR use.

(a) Gardner et al. 35

(b) The Harris Poll. 13

Methods

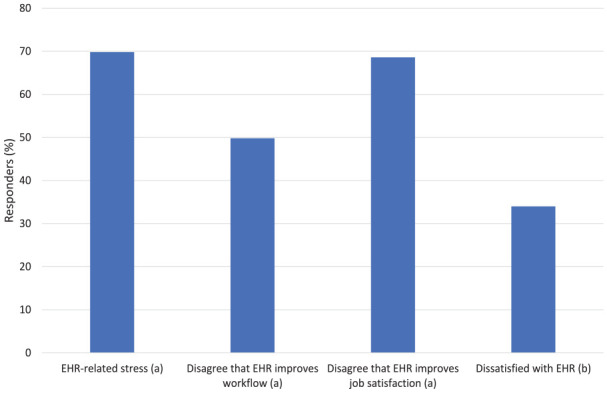

Figure 3 is a summary of the literature search of PubMed completed in June, 2022 and February, 2023 to include articles 2010 to present. The search strategy was for titles having keywords that included the following: ([“EHR” or “EHRs” or “EMR” or “EMRs” or “electronic health record” or “electronic medical record” or “electronic health record” or “electronic health records” or “health information technology”] AND [“stress” or “burnout” or “time” or “clerical” or “frustration” or “fatigue” or “cognitive” or “burden” or “workload”]). Articles were filtered to English language only. Sequential title, abstract, and full text reviews were completed with the following exclusion criteria: (1) not applicable to primary care or general practice of medicine, (2) not involving EHRs in the U.S., (3) not related to physician burnout, and (4) editorials or commentaries. Reference sections from selected articles were also reviewed for additional relevant literature. Table 1 summarizes key findings from the 36 articles that were eligible for inclusion in this review at the end of the search.

Figure 3.

Summary of literature search.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Findings From Included Articles.

| Source | Key findings | Potential contribution to burnout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Documentation | Usability | Cognitive load | Time demands | Electronic messaging | ||

| Berg, 2022 14 | Simplified logins reduce fatigue. | X | ||||

| Melnick et al, 2020 15 | EHR usability correlates with burnout. | X | ||||

| Murphy et al, 2019 16 | EHR usability is often suboptimal. | X | ||||

| Rodriguez Torres et al, 2017 17 | EHR documentation for ophthalmology residents affected by usability. | X | ||||

| Sinsky and Privitera, 2018 18 | Increased workload with EHR use. | X | ||||

| Street et al, 2014 19 | Less effective communication during patient visits from EHR activity. | X | ||||

| Coleman et al, 2015 20 | Survey of Wisconsin physicians showing perceived benefits and disadvantages of EMR use. | X | X | |||

| Eschenroeder et al, 2021 21 | Survey data showing correlation between after-hours EMR use and burnout. | X | ||||

| Kroth et al, 2018 22 | Qualitative analysis from focus groups documents perceived benefits and stressors of EMR use. | X | ||||

| Linzer et al, 2016 23 | Survey of GIM providers documents varying stress and burnout associated with EMR. | X | ||||

| Adler-Milstein et al, 2020 24 | Combined survey data and EHR log files showed that EHR message volume correlates with burnout. | X | X | |||

| Arndt et al, 2017 25 | Retrospective cohort study showing PCPs spend more than half of work day interacting with EHR. | X | X | |||

| Hilliard et al, 2020 26 | Data from clinician survey and EHR data showing high volumes of patient call messages are associated with clinician burnout. | X | ||||

| Johnson et al, 2021 27 | Review article of history of EMR use and burnout. | X | X | |||

| Lieu et al, 2019 28 | Interviews with PCPs show new stressors from volume of electronic messages and patient expectations. | X | ||||

| Murphy et al, 2016 29 | Data reviewed from EHR logs showed large volume of information being communicated to PCPs. | X | ||||

| Tran et al, 2019 30 | Cross-sectional study of EHR use and PCP self-reported burnout showed correlation of burnout with inbox demands. | X | ||||

| Akbar et al, 2021 31 | Inbox time mostly from patient messages. | X | ||||

| Downing et al, 2018 32 | EHR contributes to increased documentation. | X | ||||

| Colicchio et al, 2019 33 | Unintended consequences of EHR systems. | X | ||||

| Cusack et al, 2013 34 | AIMA policy statement to improve EHR documentation burdens. | X | ||||

| Gardner et al, 2019 35 | HIT stress is common and independently predictive of burnout symptoms. | X | X | |||

| Koopman et al, 2015 36 | More information in ambulatory clinic notes than necessary after EHR implementation. | X | ||||

| Kroth et al, 2019 37 | EHR design and use factors are associated with clinician stress and burnout. | X | ||||

| Sinsky et al, 2016 38 | EHR associated with increased clerical work beyond face-to-face clinic time. | X | ||||

| Marckini et al, 2019 39 | Clerical burden exacerbates physician burnout. | X | ||||

| Babbott et al, 2014 40 | Physician stress associated with moderate number of EMR functions. | X | ||||

| Feblowitz et al, 2011 41 | Cognitive skills needed by clinicians in practice of medicine. | X | ||||

| Holden, 2011 42 | Interview data found improvements and decrements in cognitive performance. | X | ||||

| Hysong et al, 2010 43 | PCPs from tertiary care VA had varying strategies to manage EMR alerts. | X | ||||

| Hysong et al, 2011 44 | Providers feel they receive large number of alerts many of which perceived to be unnecessary. | X | ||||

| Murphy et al, 2012 45 | PCPs receive large number of EHR alerts and spend significant time with processing. | X | ||||

| Patel et al, 2000 46 | Technology influences cognitive behavior. | X | ||||

| Pfaff et al, 2021 47 | EHR impairs ability of clinicians to see big picture. | X | ||||

| Gregory et al, 2017 48 | Alerts contribute to cognitive load. | X | ||||

| Harris Poll 13 | Doctors see value in EHRs, but want substantial improvements. | X | X | |||

Results

Contributors to EHR-related burnout may be organized into broad categories of time demands, documentation and clerical burdens, complex usability, cognitive load, and electronic messaging volume.

Documentation and Clerical Burden

The rising load of clerical tasks associated with EHRs and placed on clinicians is one of the more commonly identified reasons for burnout in medicine.39,49 Physicians have become responsible for entering not only diagnoses, orders, and visit notes but also additional administrative data of perceived low clinical value. 32 Nearly 69% of PCPs feel that most EHR clerical tasks completed by them do not require a trained physician. 13 In a survey of 282 clinicians from 3 institutions in California, Colorado, and New Mexico, of which 68% worked in primary care, the most prominent concern (86.9% of responders) about EHR use was the need for excessive data entry. 37 In fact, clinicians may need as much as 2 additional hours in electronic data entry for every hour of direct patient contact. 38 Physicians with insufficient time for documentation are 2.8 times more likely to report symptoms of burnout, 35 and in some cases clinic schedules are deliberately shortened and spots closed to allow sufficient time. 33

From purely clinical care standpoint, the primary reason for notes and documentation has been simply to describe what happened during a visit to provide details needed for the context of the next visit, continue a plan of care, and clarify factors that affect care of a patient. 36 Implementation of EHRs along with the evolving demands of additional stakeholders in the healthcare system have expanded documentation requirements to include billing criteria, quality measures, and compliance matters. 36 These external demands have lead to redundant and cumbersome data capture, 34 and the length of clinical notes alone have doubled since the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act 37 in 2009 provided financial incentives to adopt EHRs but with added needs to demonstrate meaningful use.

Complex Usability

The quality of a user’s experience with a technology in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and overall satisfaction can be quantified with the System Usability Scale (SUS) to a score of 0 to 100, with the industry average at a 68. 50 For example, the SUS score for Google search of 93, a usability grade of A, is in the top 0.01% of technologies, and the score for Microsoft Excel of 57, a usability grade of F, is in the bottom 22%. 15 Overall EHR usability from a survey of US physicians between 2017 and 2018 has a SUS score of 45.9, which is in the bottom 9%, a usability grade of F, and is categorized as “not acceptable” in comparison to other products. 15

In The Harris Poll, 90% of PCPs felt that EHRs need to be more intuitive and responsive, and 72% believed that enhancing user interfaces would best address EHR challenges in the immediate future. 13 Interfaces can often be complicated by elements that are distracting, duplicated or clinically irrelevant. 16

Navigation seems inefficient in EHRs 35 at least partially as a result of complex webs of windows, icons, menus, and pointers. 19 Workflows can be hindered by long pull-down lists that are unfiltered or unorganized by context and by deeply nested menus. 19 Seemingly straight-forward tasks may also be divided inappropriately into several small steps with multiple scrolls, points, and clicks. 19 Streams of numerous dialog boxes to enter documentation also leads to mouse-click fatigue. 17

Security issues can also contribute to diminished usability by requiring multiple long-ins per patient and by requiring progressively more-complex passwords with also progressively shorter expiration periods. 18 Surprisingly, total clinic time spent on security tasks may equal time spent on reviewing problem lists. 18 When physicians at Yale School of Medicine switched to a badge tap log-in system to eliminate repetitive typing of username and password, up to 140 times per day individually, up to 20 min per day were saved along with removing the annoyance. 14

Cognitive Load

EHR-associated information overload impedes locating and identifying key clinical information and imposes substantial cognitive demands on physicians.11,40 In addition to inefficiency and the contribution to physician burnout, there is a risk to patient care in missing or overlooking critical data. 41 Nearly 70% of physicians in a survey of 2 Midwestern hospitals reported difficulties in finding needed information in the EHR from overload. 42 Data to be reviewed for a single patient encounter are often difficult to separate from clinically unnecessary information in EHR displays 37 and often organized in fragmented data groups in varying locations and formats.41,46 In a cognitive task analysis of experienced clinicians, the EHR was not found to be helpful in maintaining awareness of the big picture in care of a patient. 47

EHR notes can be challenging to cognitively process from bulky structures and cluttering with nonessential or repetitive details. 36 The use of templates and structured data entries can contribute by creating poor syntax and narrative flow of text. 36 Copying and pasting parts of previous notes is common with EHRs and can also generate lengthy, bloated notes with redundant information and errors. 33 More than half the content of 100 randomly selected resident progress notes at an urban academic medical center in New York was duplicated from previous notes. 51

Alerts and reminders also bring about information overload and cognitive fatigue.33,48 In a study of primary care clinics at a large, tertiary care Veterans Affairs (VA) facility, physicians received an average of 56.4 alerts daily and spent 49 min daily to process these. 45 In a separate study of focus groups from 2 large VA centers, the 3 most cited barriers from alerts were the high volume, workload, and perception that some alerts were unnecessary. 44 Making clinical decisions based on these alerts can be a considerable cognitive demand because many factors must be processed at the same time, such as degree of urgency, critical status, chart review, and determination whether the alert is simply informational or requires action. 43

Time Demands

Physicians may be spending 49.2% of total time in an average clinic day on EHR and desk work and only 27% in direct face time with patients. 38 In the exam room alone, EHR activity may represent up to 37% of visit time. 38 More than half of physicians in a 2014 survey by the Wisconsin Medical Society reported that the EHR has worsened patient interactions. 20 Nearly 62% of PCPs in the 2018 Harris Poll felt they had insufficient time to adequately address patient questions or concerns as a result of EHR time demands, and 69% felt that EHRs take valuable time away from patients. 13

A prevalent concern of nearly two thirds (63%) of physicians about EHR use is the interference with work-life balance. 37 Half of physicians feel too much time is spent on EHR use at home,22,23 and the odds of burnout for those physicians expressing moderately high to excessive home EHR time are nearly twice that for those reporting minimal home EHR time. 35 In nationwide data from the Arch Collaborative of more than 200 separate health organizations, physicians with home EHR charting of 5 h or less weekly were 2.43 times more likely to have lower burnout scores than those charting 6 h or more. 21

Electronic Messaging and Inbox

With the adoption of EHRs, patients have an alternate form of access to providers through patient portals and secure messaging, and the volumes of these messages are steadily rising. 27 Patient portal messages alone in primary care at the University of Wisconsin increased 62% from 2013 to 2016. 25 Additional EHR inbox messages that also encompass patient care tasks outside of a traditional face-to-face visit include patient call notes, form requests, refill requests, and referral responses.26,29 In a study of PCPs from 5 medical facilities within Kaiser Permanente, most EHR inbox effort was spent on patient messages, and stress duration measured by physiological sensors was longest for those who completed inbox tasks mostly outside of clinic hours. 31

The number of inbox messages addressed is a significant predictor of burnout. 26 In a study of primary care practices in a large academic health system in San Francisco, providers with more than 307 messages per clinical FTE per week (the highest quartile in the study) were 6 times more likely to have exhaustion compared to those with less than 147 messages (the lowest quartile). 24 In another retrospective cohort study in the ambulatory clinics of the 2 largest healthcare systems in Rhode Island, clinicians with high message volumes were 4 times more likely to report symptoms of burnout than those with fewer volumes, and inbox volume was the most significant predictor of burnout over other workload measures including number of daily appointments, time spend reviewing charts, number of orders placed, note length, and number of result messages. 26 In that study, PCPs received 4 times more messages than specialists. 26

The EHR inbox competes with other activities of a clinical workday and may have become nearly the equivalent of a second set of patients to be treated beyond scheduled patients. 28 In a qualitative study from interviews with PCPs across facilities of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, commonly voiced stressors from inbox management beyond workload alone were patient expectations for rapid replies, unlimited nature of the inbox, and a sense of urgency from a full inbox. 28 Unlike effort spent in care of scheduled patients, the added burden of care given through electronic messaging is also typically unmeasured productivity and not reimbursable. 30

Conclusion

EHRs may offer several advantages over paper-based records such as coordinating care between several health care providers and clinics, providing a mechanism for safer and reliable prescribing, having legible documentation, improving communication with patients, and enhancing the security of patient data. 52 However, EHRs have also created new or exacerbated traditional stressors for physicians and have become a pronounced contributor to burnout. Substantial clerical and data-entry burdens are newer, additional responsibilities for healthcare providers and frequently seem redundant and cumbersome. Portions of these documentation requirements involve issues such as billing, quality metrics, and compliance that may appear beyond fundamental patient care.

Compared to other forms of technology, EHRs also tend have a relatively poor overall usability score. This may be a at least partially a result of overly complex interfaces and inefficient, nonintuitive workflows. Information overload, bulky notes, alerts, and reminders further add the cognitive burdens in patient care. EHR activities may also take valuable clinic time away from direct patient interactions and take time after clinic hours that interferes with a healthy work-life balance. EHR inboxes are an added source of patient care tasks beyond traditional face-to-face visits. The number of inbox messages to be addressed has been increasing in the past several years, correlates with burnout, and often represents unmeasured productivity.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: JB is sole author and editor of the manuscript.

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jeffrey Budd  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6816-6619

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6816-6619

References

- 1.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Physician burnout. February17, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/prevention/clinician/ahrq-works/burnout/index.html

- 2.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(3):491-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11): 1571-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Huang B, Hammer H, Kivlahan C, Grumbach K.Burnout and health care workforce turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):36-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler-Milstein J, Holmgren AJ, Kralovec P, Worzala C, Searcy T, Patel V.Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: the emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1142-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics. Percentage of office-based physicians using any electronic health record (EMR) system and physicians that have a certified EHR/EMR system, by state: National Electronic Health Records Survey. 2017. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nehrs/surveyproducts.htm [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha A, Iliff A, Chaoui A, Defossez S, Bombaugh M, Miller Y. A Crisis in Health Care: A Call to Action on Physician Burnout. Massachusetts Medical Society, Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard Global Health Institute. 2018. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.massmed.org/Publications/Research,-Studies,-and-Reports/Physician-Burnout-Report-2018/

- 10.Tajirian T, Stergiopoulos V, Strudwick G, et al. The influence of electronic health record use on physician burnout: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e19274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Malley AS, Grossman JM, Cohen GR, Kemper NM, Pham HH.Are electronic medical records helpful for care coordination? Experiences of physician practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):177-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelland KD, Baier RR, Gardner RL.“It’s like texting at the dinner table”: a qualitative analysis of the impact of electronic health records on patient-physician interaction in hospitals. J Innov Health Inform. 2017;24(2):894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Harris Poll. How doctors feel about electronic health records. 2018. Accessed June 17, 2022. http://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/ehr/documents/EHR-Poll-Presentation.pdf

- 14.Berg S.Simpler logins, voice recognition ease click fatigue at Yale. AMA Digital. 2018. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/simpler-logins-voice-recognition-ease-click-fatigue-yale

- 15.Melnick ER, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky CA, et al. The association between perceived electronic health record usability and professional burnout among US Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(3):476-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy DR, Giardina TD, Satterly T, Sittig DF, Singh H.An exploration of barriers, facilitators, and suggestions for improving electronic health record inbox-related usability: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez Torres Y, Huang J, Mihlstin M, Juzych MS, Kromrei H, Hwang FS.The effect of electronic health record software design on resident documentation and compliance with evidence-based medicine. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinsky CA, Privitera MR.Creating a “manageable cockpit” for clinicians: a shared responsibility. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):741-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Street RL, Liu L, Farber NJ, et al. Provider interaction with the electronic health record: the effects on patient-centered communication in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):315-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman M, Dexter D, Nankivil N.Factors affecting physician satisfaction and Wisconsin Medical Society strategies to drive change. WMJ. 2015;114(4):135-142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eschenroeder HC, Manzione LC, Adler-Milstein J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with organizational electronic health record support and after-hours charting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(5):960-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, et al. The electronic elephant in the room: physicians and the electronic health record. JAMIA Open. 2018;1(1):49-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in Academic General Internal Medicine: results from a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler-Milstein J, Zhao W, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Grumbach K.Electronic health records and burnout: time spent on the electronic health record after hours and message volume associated with exhaustion but not with cynicism among primary care clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020; 27(4):531-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR Event Log Data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilliard RW, Haskell J, Gardner RL.Are specific elements of electronic health record use associated with clinician burnout more than others? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(9): 1401-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson KB, Neuss MJ, Detmer DE.Electronic health records and clinician burnout: a story of three eras. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(5):967-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieu TA, Altschuler A, Weiner JZ, et al. Primary care physicians’ experiences with and strategies for managing electronic messages. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1918287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy DR, Meyer AN, Russo E, Sittig DF, Wei L, Singh H.The burden of inbox notifications in commercial electronic health records. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):559-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran B, Lenhart A, Ross R, Dorr DA.Burnout and EHR use among academic primary care physicians with varied clinical workloads. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2019;2019: 136-144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akbar F, Mark G, Prausnitz S, et al. Physician stress during electronic health record inbox work: in situ measurement with wearable sensors. JMIR Med Inform. 2021;9(4): e24014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA.Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: are we ignoring the real cause? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):50-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colicchio TK, Cimino JJ, Del Fiol G.Unintended consequences of nationwide electronic health record adoption: challenges and opportunities in the post-meaningful use era. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cusack CM, Hripcsak G, Bloomrosen M, et al. The future state of clinical data capture and documentation: a report from AMIA’s 2011 Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):134-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner RL, Cooper E, Haskell J, et al. Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(2):106-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koopman RJ, Steege LM, Moore JL, et al. Physician information needs and electronic health records (EHRs): time to reengineer the clinic note. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015; 28(3):316-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, et al. Association of electronic health record design and use factors with clinician stress and burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marckini DN, Samuel BP, Parker JL, Cook SC.Electronic health record associated stress: a survey study of adult congenital heart disease specialists. Congenit Heart Dis. 2019; 14(3):356-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100-e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feblowitz JC, Wright A, Singh H, Samal L, Sittig DF.Summarization of clinical information: a conceptual model. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(4):688-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holden RJ.Cognitive performance-altering effects of electronic medical records: an application of the human factors paradigm for patient safety. Cogn Technol Work. 2011;13(1):11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hysong SJ, Sawhney MK, Wilson L, et al. Provider management strategies of abnormal test result alerts: a cognitive task analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(1):71-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hysong SJ, Sawhney MK, Wilson L, et al. Understanding the management of electronic test result notifications in the outpatient setting. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2011;11:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy DR, Reis B, Sittig DF, Singh H.Notifications received by primary care practitioners in electronic health records: a taxonomy and time analysis. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):209.e1-209.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel VL, Kushniruk AW, Yang S, Yale JF.Impact of a computer-based patient record system on data collection, knowledge organization, and reasoning. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(6):569-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfaff MS, Eris O, Weir C, et al. Analysis of the cognitive demands of electronic health record use. J Biomed Inform. 2021;113:103633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gregory ME, Russo E, Singh H.Electronic health record alert-related workload as a predictor of burnout in primary care providers. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(3):686-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright AA, Katz IT.Beyond burnout - redesigning care to restore meaning and sanity for physicians. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):309-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.United States General Services Administration. What & why of usability. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.usability.gov/index.html

- 51.Wrenn JO, Stein DM, Bakken S, Stetson PD.Quantifying clinical narrative redundancy in an electronic health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(1):49-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HealthIT.gov, Frequently asked questions, advantages of electronic health records. 2022. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-are-advantages-electronic-health-records