Abstract

BACKGROUND

For the prognosis of patients with early gastric cancer (EGC), lymph node metastasis (LNM) plays a crucial role. A thorough and precise evaluation of the patient for LNM is now required.

AIM

To determine the factors influencing LNM and to construct a prediction model of LNM for EGC patients.

METHODS

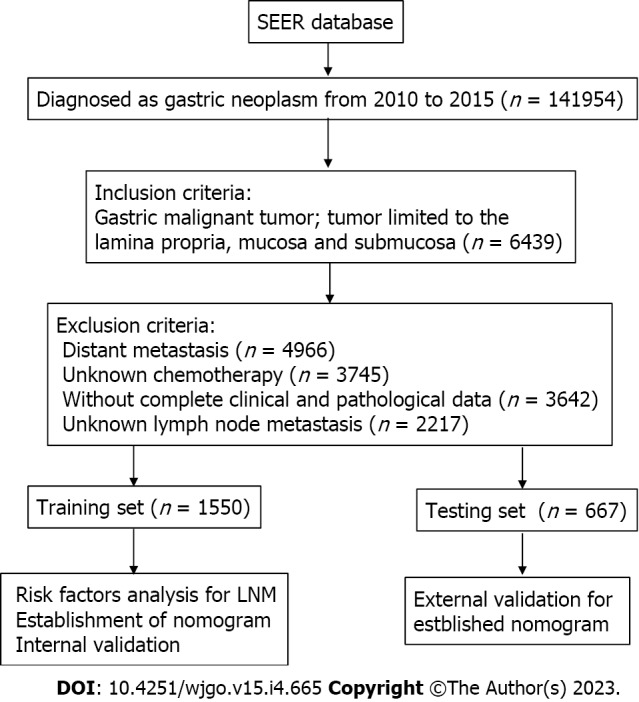

Clinical information and pathology data of 2217 EGC patients downloaded from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database were collected and analyzed. Based on a 7:3 ratio, 1550 people were categorized into training sets and 667 people were assigned to testing sets, randomly. Based on the factors influencing LNM determined by the training sets, the nomogram was drawn and verified.

RESULTS

Based on multivariate analysis, age at diagnosis, histology type, grade, T-stage, and size were risk factors of LNM for EGC. Besides, nomogram was drawn to predict the risk of LNM for EGC patients. Among the categorical variables, the effect of grade (well, moderate, and poor) was the most significant prognosis factor. For training sets and testing sets, respectively, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of nomograms were 0.751 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.721-0.782] and 0.786 (95%CI: 0.742-0.830). In addition, the calibration curves showed that the prediction model of LNM had good consistency.

CONCLUSION

Age at diagnosis, histology type, grade, T-stage, and tumor size were independent variables for LNM in EGC. Based on the above risk factors, prediction model may offer some guiding implications for the choice of subsequent therapeutic approaches for EGC.

Keywords: SEER, Early gastric cancer, Lymph node metastasis, Risk factors, Nomogram

Core Tip: A model was constructed to evaluate the impact of various indicators in an integrated manner to serve as a base for predicting lymph node metastasis (LNM) in early gastric cancer (EGC) patients. Age at diagnosis, histology type, grade, T-stage, and tumor size were independent hazard elements for LNM in EGC.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC), as the third most common cancer-related cause of death worldwide[1], for which risk indicators include Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, gender, eating habits, smoking and family history[2]. Screening may be done for GC using markers of atrophy in the stomach (a precursor lesion of GC), such as serum pepsinogens[3] or serum ghrelin[4]; or serum antibodies to Hp, the main risk factor for GC[5]; or examining the stomach mucosa using endoscopy[6].

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is classified as a GC limited to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of the presence of territorial lymph node metastasis (LNM)[7]. Compared to advanced GC, EGC has a better opportunity to be surgically removed successfully, which resulting in a better survival status. Endoscopic resection (ER), which is suitable for low LNM rate of EGC, is the first-choice therapy for EGC. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) are two main operations of ER[8]. Operable advanced GC could be radically resected by surgery including D2 Lymphadenectomy[9].

Although the incidence of GC has decreased in the past 3 decades in developed countries[10], the general prognosis for GC was still poor. For example, the five-year survival rate for GC is about 20 percent[11]. LNM had good predictive value for prognosis[12]. Therefore, in patients with EGC, the presence or absence of LNM is a crucial factor to be evaluated comprehensively.

Corresponding clinicopathological information of a large sample size of EGC patients was obtained from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database[13], including clinicopathological parameters and information of patients. Factors that may be associated with the prognosis of patients with EGC were enrolled into our research to explore their influence. There are very few researches, to our knowledge, exploring the factors influencing LNM in EGC patients. Therefore, we plotted a predictive model that allows a comprehensive assessment of the effects of various indicators and provides a platform for prediction of LNM of patients with EGC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and patient selection

Clinicopathological information were obtained from the SEER database. The standards used for exclusion are listed below: (1) Patients who have undergone pre-operative neoadjuvant therapy; (2) patients with residual GC; (3) patients without complete clinical and pathological data; (4) retrieved unknown lymph nodes; and (5) patients without confirmed as EGC via biopsy.

Finally, a total of 2217 patients participated in this study and were analyzed in the next step. According to the ratio of seven to three, all patients were separately assigned to training and testing sets (1550:667).

Clinicopathological parameters

The relationship between individual clinicopathological features and LNM was evaluated to identify independent influencing variables for LNM in EGC. The clinicopathological features were examined as follow: Race, age when EGC is confirmed, gender, tumor location, histological type, degree of differentiation, TNM stage, T-stage, tumor size, LNM, survival months, status, first malignant primary indicator, sequence number, insurance recode, marital status. First malignant primary indicator, which means whether it is the first primary tumor, was divided into two subgroups: No and yes.

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables were represented as mean ± SD and examined using t-test. Categorical variables were represented as frequency and proportion and analyzed by Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. In the logistic regression, variables that were significantly different in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Factors of influence of training sets were determined and results were displayed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Furthermore, the LNM prediction model was plotted. In addition, 850 patients in the testing set, as the external validation sets, were included in the follow-up validation analysis. The power of identification of the prediction model is calculated using the consistency index, which corresponds to the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) in the logistic regression.

SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp.) and R software (version 4.0.5) were used to analyze the data. Two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significantly different.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

Two thousand two hundred and seventeen suitable patients were included in the present research (Figure 1). Of the included EGC patients, 1214 (54.8%) were male and 1003 (45.2%) were female. 1247 (56.2%) were white, 355 (16.0%) were black, and 615 (27.7%) were put in the “other” race subgroup. Moreover, T stage, 356 (16.1%) were T1/T1NOS, 801 (36.1%) were T1a, 1060 (47.8%) were T1b. Of the EGC patients, 337 (15.2%) were diagnosed with LNM totally, 1880 (84.8%) were not. The LNM rates of EGC patients were 15.6% (242/1550) in the training sets and 14.2% (95/667) in the testing sets, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The flowchart of data collection and grouping for patients with early gastric cancer. LNM: Lymph node metastasis; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Table 1.

Characteristic of 2217 patients with early gastric cancer from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

|

Variables

|

Level

|

LNM (-)

|

LNM (+)

|

P

value

|

|

n

= 1880

|

n

= 337

|

|||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 70.87 (12.82) | 68.74 (12.59) | 0.0051 | |

| Race (%) | White | 1065 (56.6) | 182 (54.0) | 0.554 |

| Black | 295 (15.7) | 60 (17.8) | ||

| Other | 520 (27.7) | 95 (28.2) | ||

| Gender (%) | Male | 1025 (54.5) | 189 (56.1) | 0.638 |

| Female | 855 (45.5) | 148 (43.9) | ||

| Location (%) | Body of stomach | 314 (16.7) | 51 (15.1) | 0.116 |

| Gastric antrum | 710 (37.8) | 133 (39.5) | ||

| Fundus of stomach | 97 (5.2) | 13 (3.9) | ||

| Greater curvature of stomach NOS | 127 (6.8) | 25 (7.4) | ||

| Lesser curvature of stomach NOS | 264 (14.0) | 47 (13.9) | ||

| Stomach, NOS | 64 (3.4) | 14 (4.2) | ||

| Pylorus | 186 (9.9) | 21 (6.2) | ||

| Overlapping lesion of stomach | 118 (6.3) | 33 (9.8) | ||

| Histologytype (%) | Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 80 (4.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.0021 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 336 (17.9) | 57 (16.9) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1349 (71.8) | 250 (74.2) | ||

| Others/unknown | 115 (6.1) | 29 (8.6) | ||

| Grade (%) | Well | 377 (20.1) | 12 (3.6) | < 0.0011 |

| Moderate | 638 (33.9) | 115 (34.1) | ||

| Poor | 865 (46.0) | 210 (62.3) | ||

| Stage (%) | I | 80 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.0011 |

| IA | 1793 (95.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| IB | 7 (0.4) | 225 (66.8) | ||

| IIA | 0 (0.0) | 80 (23.7) | ||

| IIB | 0 (0.0) | 32 (9.5) | ||

| T-stage (%) | T1/T1NOS | 317 (16.9) | 39 (11.6) | < 0.0011 |

| T1a | 745 (39.6) | 56 (16.6) | ||

| T1b | 818 (43.5) | 242 (71.8) | ||

| Tumorsize (%) | 0-1 cm | 449 (23.9) | 15 (4.5) | < 0.0011 |

| < 2 cm | 496 (26.4) | 71 (21.1) | ||

| < 3 cm | 338 (18.0) | 75 (22.3) | ||

| < 4 cm | 228 (12.1) | 64 (19.0) | ||

| < 5 cm | 132 (7.0) | 42 (12.5) | ||

| > 5 cm and more | 237 (12.6) | 70 (20.8) | ||

| Primary (%) | No | 387 (20.6) | 54 (16.0) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 1493 (79.4) | 283 (84.0) | ||

| Order (%) | One primary only | 1323 (70.4) | 259 (76.9) | 0.0461 |

| 1st of 2 or more primaries | 146 (7.8) | 21 (6.2) | ||

| 2nd of 2 or more primaries | 310 (16.5) | 47 (13.9) | ||

| 3rd of 3 or more primaries | 74 (3.9) | 6 (1.8) | ||

| 4th of 4 or more primaries | 20 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) | ||

| 5th of 5 or more primaries | 6 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 6th of 6 or more primaries | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 7th of 7 or more primaries | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Maritalstatus (%) | Married (including common law) | 1057 (56.2) | 188 (55.8) | 0.386 |

| Divorced | 127 (6.8) | 26 (7.7) | ||

| Separated | 20 (1.1) | 5 (1.5) | ||

| Single (never married) | 243 (12.9) | 49 (14.5) | ||

| Widowed | 353 (18.8) | 55 (16.3) | ||

| Unmarried or Domestic Partner | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Unknown | 78 (4.1) | 12 (3.6) | ||

| Insurance (%) | Insured | 1129 (60.1) | 201 (59.6) | 0.575 |

| Insured/nospecifics | 338 (18.0) | 53 (15.7) | ||

| Any medicaid | 344 (18.3) | 69 (20.5) | ||

| Uninsured | 39 (2.1) | 10 (3.0) | ||

| Insurance status unknown | 30 (1.6) | 4 (1.2) |

It means statistically significant.

LMN: Lymph node metastasis; EGC: Early gastric cancer.

Prognostic variables of patients with EGC

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that some factors, such as age when EGC is confirmed, histology type, grade, TNM stage, T-stage, size, primary, were influenced variables of LNM of EGC (Table 2). Those variables treated as significant prognostic factors for LNM were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Age at diagnosis [odd ratio (OR): 0.003, P = 0.012], histology type (OR: 1.382, P = 0.019), grade (OR: 1.825, P < 0.001), T-stage (OR: 1.985, P < 0.001), and size (OR: 1.319, P < 0.001) were independent influenced variables for LNM (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for lymph node metastasis of patients with early gastric cancer

|

Variables

|

Level

|

Training sets

|

P

value

|

Testing sets

|

P

value

|

||

|

LNM (-)

|

LNM (+)

|

LNM (-)

|

LNM (+)

|

||||

|

n

= 1308

|

n

= 242

|

n

= 572

|

n

= 95

|

||||

| Age at diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 71.07 (12.82) | 68.64 (12.82) | 0.0071 | 70.42 (12.80) | 69.02 (12.03) | 0.319 | |

| Race (%) | White | 733 (56.0) | 122 (50.4) | 0.237 | 332 (58.0) | 60 (63.2) | 0.584 |

| Black | 202 (15.4) | 45 (18.6) | 93 (16.3) | 15 (15.8) | |||

| Other | 373 (28.5) | 75 (31.0) | 147 (25.7) | 20 (21.1) | |||

| Gender (%) | Male | 710 (54.3) | 136 (56.2) | 0.631 | 315 (55.1) | 53 (55.8) | 0.985 |

| Female | 598 (45.7) | 106 (43.8) | 257 (44.9) | 42 (44.2) | |||

| Location (%) | Body of stomach | 215 (16.4) | 38 (15.7) | 0.239 | 99 (17.3) | 13 (13.7) | 0.444 |

| Gastric antrum | 479 (36.6) | 90 (37.2) | 231 (40.4) | 43 (45.3) | |||

| Fundus of stomach | 67 (5.1) | 12 (5.0) | 30 (5.2) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Greater curvature of stomach | 86 (6.6) | 19 (7.9) | 41 (7.2) | 6 (6.3) | |||

| Lesser curvature of stomach | 192 (14.7) | 35 (14.5) | 72 (12.6) | 12 (12.6) | |||

| Stomach, NOS | 51 (3.9) | 10 (4.1) | 13 (2.3) | 4 (4.2) | |||

| Pylorus | 131 (10.0) | 13 (5.4) | 55 (9.6) | 8 (8.4) | |||

| Overlapping lesion of stomach | 87 (6.7) | 25 (10.3) | 31 (5.4) | 8 (8.4) | |||

| Histology type (%) | Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 53 (4.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0.0031 | 27 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.088 |

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 238 (18.2) | 43 (17.8) | 98 (17.1) | 14 (14.7) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 940 (71.9) | 173 (71.5) | 409 (71.5) | 77 (81.1) | |||

| Others/unknown | 77 (5.9) | 25 (10.3) | 38 (6.6) | 4 (4.2) | |||

| Grade (%) | Well | 252 (19.3) | 7 (2.9) | < 0.0011 | 125 (21.9) | 5 (5.3) | < 0.0011 |

| Moderate | 448 (34.3) | 85 (35.1) | 190 (33.2) | 30 (31.6) | |||

| Poor | 608 (46.5) | 150 (62.0) | 257 (44.9) | 60 (63.2) | |||

| Stage (%) | I | 53 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.0011 | 27 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.0011 |

| IA | 1250 (95.6) | 0 (0.0) | 543 (94.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| IB | 5 (0.4) | 166 (68.6) | 2 (0.3) | 59 (62.1) | |||

| IIA | 0 (0.0) | 54 (22.3) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (27.4) | |||

| IIB | 0 (0.0) | 22 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (10.5) | |||

| T-stage (%) | T1/T1NOS | 216 (16.5) | 30 (12.4) | < 0.0011 | 101 (17.7) | 9 (9.5) | < 0.0011 |

| T1a | 514 (39.3) | 37 (15.3) | 231 (40.4) | 19 (20.0) | |||

| T1b | 578 (44.2) | 175 (72.3) | 240 (42.0) | 67 (70.5) | |||

| Tumor size (%) | 0-1 cm | 313 (23.9) | 12 (5.0) | < 0.0011 | 136 (23.8) | 3 (3.2) | < 0.0011 |

| < 2 cm | 331 (25.3) | 51 (21.1) | 165 (28.8) | 20 (21.1) | |||

| < 3 cm | 241 (18.4) | 59 (24.4) | 97 (17.0) | 16 (16.8) | |||

| < 4 cm | 158 (12.1) | 45 (18.6) | 70 (12.2) | 19 (20.0) | |||

| < 5 cm | 89 (6.8) | 28 (11.6) | 43 (7.5) | 14 (14.7) | |||

| > 5 cm and more | 176 (13.5) | 47 (19.4) | 61 (10.7) | 23 (24.2) | |||

| Primary (%) | No | 268 (20.5) | 34 (14.0) | 0.0251 | 119 (20.8) | 20 (21.1) | 0.956 |

| Yes | 1040 (79.5) | 208 (86.0) | 453 (79.2) | 75 (78.9) | |||

| Order (%) | One primary only | 918 (70.2) | 190 (78.5) | 0.146 | 405 (70.8) | 69 (72.6) | 0.332 |

| 1st of 2 or more primaries | 104 (8.0) | 16 (6.6) | 42 (7.3) | 5 (5.3) | |||

| 2nd of 2 or more primaries | 215 (16.4) | 31 (12.8) | 95 (16.6) | 16 (16.8) | |||

| 3rd of 3 or more primaries | 51 (3.9) | 3 (1.2) | 23 (4.0) | 3 (3.2) | |||

| 4th of 4 or more primaries | 14 (1.1) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| 5th of 5 or more primaries | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 6th of 6 or more primaries | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 7th of 7 or more primaries | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Marital status (%) | Married | 743 (56.8) | 131 (54.1) | 0.444 | 314 (54.9) | 57 (60.0) | 0.431 |

| Divorced | 80 (6.1) | 15 (6.2) | 47 (8.2) | 11 (11.6) | |||

| Separated | 13 (1.0) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | |||

| Single | 165 (12.6) | 36 (14.9) | 78 (13.6) | 13 (13.7) | |||

| Widowed | 251 (19.2) | 46 (19.0) | 102 (17.8) | 9 (9.5) | |||

| Unmarried or Domestic Partner | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Unknown | 54 (4.1) | 8 (3.3) | 24 (4.2) | 4 (4.2) | |||

| Insurance (%) | Insured | 784 (59.9) | 149 (61.6) | 0.515 | 345 (60.3) | 52 (54.7) | 0.771 |

| Insured/no specifics | 234 (17.9) | 34 (14.0) | 104 (18.2) | 19 (20.0) | |||

| Any medicaid | 243 (18.6) | 48 (19.8) | 101 (17.7) | 21 (22.1) | |||

| Uninsured | 28 (2.1) | 8 (3.3) | 11 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) | |||

| Insurance status unknown | 19 (1.5) | 3 (1.2) | 11 (1.9) | 1 (1.1) | |||

It means statistically significant.

LMN: Lymph node metastasis; EGC: Early gastric cancer.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis for lymph node metastasis in training set with early gastric cancer

|

Variables

|

P

value

|

OR

|

95%CI

|

| Age | 0.012 | 0.986 | 0.975-0.997 |

| Histology type | 0.019 | 1.382 | 1.057-1.813 |

| Grade | 0.000 | 1.825 | 1.452-2.315 |

| T-stage | 0.000 | 1.985 | 1.596-2.494 |

| Size | 0.000 | 1.319 | 1.208-1.442 |

| Primary | 0.152 | 1.344 | 0.907-2.040 |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio.

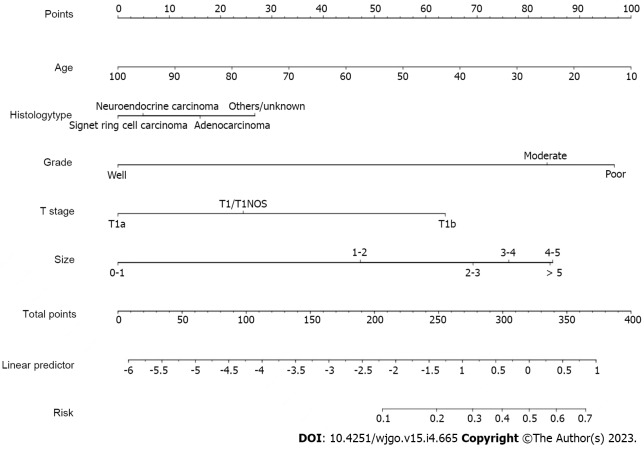

Construction of the prediction model for EGC patients

A nomogram prediction model was constructed (Figure 2). In the model, the points of each variable ranged from 0 to 100. Each indicator has its corresponding score row, in which each patient has a score that is derived from the corresponding first row. The total point is the sum of the points of all variable. And then, the total score for each patient corresponds to the probability of the bottom which is the probability of occurrence of LNM.

Figure 2.

Nomogram prediction model for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer patients.

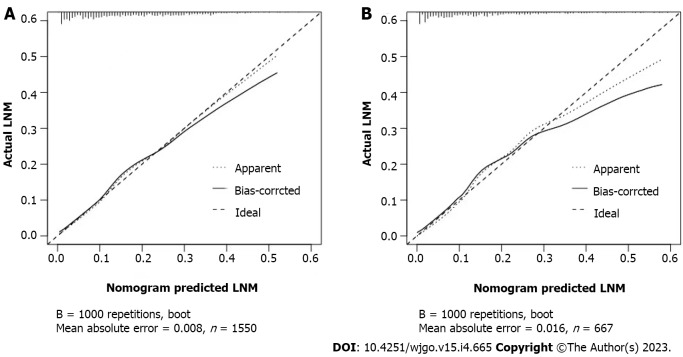

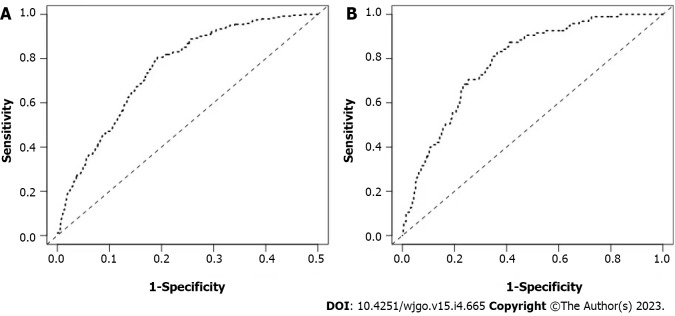

Evaluation of the nomogram

The calibration curves of the training and testing sets used to compare the forecasted situation with the actual situation, both showed satisfactory consistency (Figure 3). The AUC of internal validation was 0.751 (95%CI: 0.721-0.782) and of external validation was 0.786 (95%CI: 0.742-0.830), respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Calibration curve of the nomogram prediction model for early gastric cancer patients. A: Internal validations for the nomogram prediction model for the training set of early gastric cancer (EGC) patients; B: External validations for the nomogram prediction model for the testing set of EGC patients. LNM: Lymph node metastasis.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the nomogram prediction model for early gastric cancer patients. A: Internal validations for the nomogram prediction model for the training set of early gastric cancer (EGC) patients; B: External validations for the nomogram prediction model for the testing set of EGC patients.

DISCUSSION

GC has a significant impact worldwide[14]. GC, occurs in the epithelium of the gastric mucosa, tendency to undergo hematogenous or LNM even in the early stages[15]. As the understanding of GC becomes more comprehensive and deeper, the rate of occurrence and mortality is decreasing year by year[16]. The average of age at diagnosis of GC patients was lower and lower in recent year[1].

Based on Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2018[17], EGC can be treated by EMR or ESD, with acceptable results in the west[18]. EMR is primarily indicated for mucosal cancers without ulcer and with a mucosal diameter of ≤ 2 cm to be excised, which was the first endoscopic treatment for EGC. Compared to EMR, ESD is not limited by tumor size or ulceration, which is facilitate curative tumor resection[19]. The operation is judged to be a radical resection if all of the followings are met: en bloc resection, intestinal-differentiated-type, pathological-T1a, tumor size ≤ 2 cm, negative surgical cut edge (both lateral and vertical), and absence of lymphovascular invasion[20].

LNM has a clear correlation with poor prognosis in patients with EGC[21]. The presence or absence of LNM determines the choice of treatment. Precisely predicting the presence or absence of LNM in EGC patients helps to select the best treatment modality, which is of great importance in the clinical treatment process. Therefore, construction of the prediction model for EGC patients may help find those who were be prone to LNM and prolong survival time after surgery[22].

The process of nomogram development was clarified in previous study[22]. In our study, age when EGC is confirmed (OR: 0.003, P = 0.012), histology type (OR: 1.382, P = 0.019), grade (OR: 1.825, P < 0.001), T-stage (OR: 1.985, P < 0.001), and tumor size (OR: 1.319, P < 0.001) were independent influenced variables for LNM. Those variables were used to construct the predict model. Our clinical prediction models are more believable and more convincing because they are internally validated and externally validated.

Among the categorical data, the degree of differentiation is the most important influencing factor, which was consistent with previous findings[23]. Xiang et al[24] indicated that miR-145-5p was capable to induce the differentiation of GC and affect the LNM of GC.

Early-stage cancers less than 4 cm have a very low LNM rate and can be evaluated for local excision[25]. Other study showed that tumor with large diameter and deep invasion were independent risk factors for LNM[26]. Sekiguchi et al[27] reported that tumor with large diameter, depth, and histological type were confirmed to be the independent influencing element of LNM.

Besides, age at diagnosis, tumor size, T-stage, and histology type were also the independent influenced variables for LNM. Gurzu et al[28] found that in younger patients with GC, the expression of VEGF is more active, which increases the probability of tumor invasion and LMN in GC. Bao et al[29] argued that increased expression of MDM4 could correlate with LNM and lead to poorer survival status of GC especially in younger patients. Park et al[30] study revealed that the tissue of GC is more invasive in younger patients than in older patients. The LNM rates in young EGC patients were higher than in other patients probably related to the higher malignant potential of their tumors[31].

This is the fact that tumor infiltrating into the submucosa of the stomach is related to the increased significantly incidence of LNM[32,33], which our study came to the similar findings. Radical surgical resection and lymph node dissection are suitable for deeply infiltrated GC[34].

However, our research has some limitations. First of all, only patients with EGC who underwent surgery were included in this study for retrospective analysis Secondly, “others/unknown” expanded applicability of the predicted model which could be influenced the precision of the model. Thirdly, the molecular pathologic characteristics, family history, and H. pylori infection are not enrolled in analysis.

CONCLUSION

Age at diagnosis, histology type, grade, T-stage, and tumor size were independent risk variables for LNM in EGC. Based on these, the predictive model was built for predicting possibilities of LNM in EGC patients. Both internal and external validation proved the credibility and persuasiveness which demonstrated by the receiver operating characteristic and the calibration curve.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Lymph node metastasis (LNM) has a major influence on the postoperative survival status of patients with early gastric cancer.

Research motivation

Our aim was to improve early gastric cancer (EGC) patients’ prognosis.

Research objectives

To improve EGC patients’ prognosis.

Research methods

Clinical information and pathology data of 2217 EGC patients were collected and analyzed. Based on a 7:3 ratio, 1550 people were grouped to training sets and 667 people were assigned to testing sets, randomly. The predictive model was built based on the training set for predicting possibilities of LNM in EGC patients. Both internal and external validation proved the credibility and persuasiveness which demonstrated by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and the calibration curve.

Research results

Age at diagnosis, histology type, grade, T-stage, and size were risk factors of LNM for EGC. Besides, nomogram was drawn to predict the risk of LNM for EGC patients. Among the categorical variables, the effect of grade (well, moderate, and poor) was the most significant prognosis factor. For training sets and testing sets, respectively, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve of nomograms were 0.751 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.721-0.782] and 0.786 (95%CI: 0.742-0.830). In addition, the calibration curves showed that the prediction model of LNM had good consistency.

Research conclusion

Based on these independent risk variables, the predictive model was built for predicting possibilities of LNM in EGC patients. Both internal and external validation proved the credibility and persuasiveness which demonstrated by the ROC and the calibration curve.

Research perspectives

We analyzed the independent influenced variables for LNM in EGC patients. Based on the independent risk factors, the prediction model was plotted. After internal validation and external validation, the ROC and the calibration curve were built, which validated the credible and persuasive of the nomogram.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Institutional review board statement was not acquired since data were obtained from the SEER database that covering approximately 28% of the cases in the United States.

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 12, 2022

First decision: January 3, 2023

Article in press: March 21, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li DH, China; Senchukova M, Russia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

Contributor Information

Xiao-Cong Jiang, Department of Radiotherapy Oncology, Huizhou Municipal Central Hospital, Huizhou 516001, Guangdong Province, China.

Xiao-Bing Yao, Emergency Surgery, Shanghai Seventh People’s Hospital, Shanghai 200137, China.

Heng-Bo Xia, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Ye-Zhou Su, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Pan-Quan Luo, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Jian-Ran Sun, Department of Endocrinology, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Science and Medicine, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

En-Dong Song, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Zhi-Jian Wei, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

A-Man Xu, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Li-Xiang Zhang, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China; Department of Gastroenterology, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei 230031, Anhui Province, China.

Yu-Hong Lan, Department of Radiotherapy Oncology, Huizhou Municipal Central Hospital, Huizhou 516001, Guangdong Province, China. lll931682207@qq.com.

Data sharing statement

The data can be obtained from the correspondence. The collection of patient information did not require informed consent nor institutional review because such information was publicly available.

References

- 1.Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:700–713. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ren JS, Kamangar F, Qiao YL, Taylor PR, Liang H, Dawsey SM, Liu B, Fan JH, Abnet CC. Serum pepsinogens and risk of gastric and oesophageal cancers in the General Population Nutrition Intervention Trial cohort. Gut. 2009;58:636–642. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy G, Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Stanczyk FZ, Weinstein SJ, Taylor PR, Virtamo J, Abnet CC, Albanes D, Freedman ND. The relationship between serum ghrelin and the risk of gastric and esophagogastric junctional adenocarcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1123–1129. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamangar F, Sheikhattari P, Mohebtash M. Helicobacter pylori and its effects on human health and disease. Arch Iran Med. 2011;14:192–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricci C, Holton J, Vaira D. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: invasive and non-invasive tests. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma - 2nd English Edition - Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P, Bialek A, Conio M, Haringsma J, Langner C, Meisner S, Messmann H, Morino M, Neuhaus H, Piessevaux H, Rugge M, Saunders BP, Robaszkiewicz M, Seewald S, Kashin S, Dumonceau JM, Hassan C, Deprez PH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829–854. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degiuli M, De Manzoni G, Di Leo A, D'Ugo D, Galasso E, Marrelli D, Petrioli R, Polom K, Roviello F, Santullo F, Morino M. Gastric cancer: Current status of lymph node dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2875–2893. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i10.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catalano V, Labianca R, Beretta GD, Gatta G, de Braud F, Van Cutsem E. Gastric cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;54:209–241. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wanebo HJ, Kennedy BJ, Chmiel J, Steele G Jr, Winchester D, Osteen R. Cancer of the stomach. A patient care study by the American College of Surgeons. Ann Surg. 1993;218:583–592. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199321850-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong D, Fang MJ, Tang L, Shan XH, Gao JB, Giganti F, Wang RP, Chen X, Wang XX, Palumbo D, Fu J, Li WC, Li J, Zhong LZ, De Cobelli F, Ji JF, Liu ZY, Tian J. Deep learning radiomic nomogram can predict the number of lymph node metastasis in locally advanced gastric cancer: an international multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doll KM, Rademaker A, Sosa JA. Practical Guide to Surgical Data Sets: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:588–589. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venerito M, Link A, Rokkas T, Malfertheiner P. Gastric cancer - clinical and epidemiological aspects. Helicobacter. 2016;21 Suppl 1:39–44. doi: 10.1111/hel.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Burden of Gastric Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition) Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catalano F, Trecca A, Rodella L, Lombardo F, Tomezzoli A, Battista S, Silano M, Gaj F, de Manzoni G. The modern treatment of early gastric cancer: our experience in an Italian cohort. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1581–1586. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Facciorusso A, Antonino M, Di Maso M, Muscatiello N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:555–563. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i11.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marrelli D, Polom K, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Baiocchi GL, Roviello F. Multimodal treatment of gastric cancer in the west: Where are we going? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7954–7969. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao BW, Chen YM, Jiang SS, Chen YB, Zhou ZW, Li YF. Lymph Node Metastasis, a Unique Independent Prognostic Factor in Early Gastric Cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iasonos A, Schrag D, Raj GV, Panageas KS. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1364–1370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng F, Liu J, Wang F, Zheng G, Wang Q, Liu S, Xu G, Guo M, Lian X, Zhang H. Prognostic value of differentiation status in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:865. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiang R, Rong Y, Ge Y, Song W, Ren J, Fu T. Cell differentiation trajectory predicts patient potential immunotherapy response and prognosis in gastric cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:5928–5945. doi: 10.18632/aging.202515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pokala SK, Zhang C, Chen Z, Gamboa AM, Cristofaro SL, Keilin SA, Cai Q, Willingham FF. Lymph node metastasis in early gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States of America. Endoscopy. 2018;50:479–486. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maehara Y, Orita H, Okuyama T, Moriguchi S, Tsujitani S, Korenaga D, Sugimachi K. Predictors of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1992;79:245–247. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekiguchi M, Oda I, Taniguchi H, Suzuki H, Morita S, Fukagawa T, Sekine S, Kushima R, Katai H. Risk stratification and predictive risk-scoring model for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:961–970. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurzu S, Kadar Z, Sugimura H, Bara T, Bara T Jr, Halmaciu I, Jung I. Gastric cancer in young vs old Romanian patients: immunoprofile with emphasis on maspin and mena protein reactivity. APMIS. 2015;123:223–233. doi: 10.1111/apm.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bao J, Nanding A, Song H, Xu R, Qu G, Xue Y. The overexpression of MDM4: an effective and novel predictor of gastric adenocarcinoma lymph node metastasis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67212–67222. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JC, Lee YC, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee SK, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3,362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:395–401. doi: 10.1002/jso.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang ZK, Lin JX, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Huang CM, Zheng CH. Higher Risk of Lymph Node Metastasis in Young Patients with Early Gastric Cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10:4389–4396. doi: 10.7150/jca.30260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barreto SG, Windsor JA. Redefining early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:24–37. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4184-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimada S, Yagi Y, Honmyo U, Shiomori K, Yoshida N, Ogawa M. Involvement of three or more lymph nodes predicts poor prognosis in submucosal gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:54–59. doi: 10.1007/pl00011724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishikawa S, Togashi A, Inoue M, Honda S, Nozawa F, Toyama E, Miyanari N, Tabira Y, Baba H. Indications for EMR/ESD in cases of early gastric cancer: relationship between histological type, depth of wall invasion, and lymph node metastasis. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:35–38. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained from the correspondence. The collection of patient information did not require informed consent nor institutional review because such information was publicly available.