Abstract

Background:

Olfactory identification (OI) impairment appears early in the course of Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), prior to detectable cognitive impairment. However, the neuroanatomical correlates of impaired OI in cognitively normal older adults (CN) and persons with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) are not fully understood.

Objective:

We examined the neuroanatomic correlates of OI impairment in older adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS).

Methods:

Our sample included 1,600 older adults without dementia who completed clinical assessment and structural brain imaging from 2011 to 2013. We characterized OI impairment using the 12-item Sniffin’ Sticks odor identification test (score ≤6). We used voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and region of interest (ROI) analyses to examine the neuroanatomic correlates of impaired OI in CN and MCI, after adjusting for potential confounders. Analyses were also separately stratified by race and sex.

Results:

In CN, OI impairment was associated with smaller amygdala gray matter (GM) volume (p<0.05). In MCI, OI impairment was associated with smaller GM volumes of the olfactory cortex, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and insula (p’s<0.05). Differential associations were observed by sex in MCI; OI impairment was associated with lower insular GM volumes among men but not among women (p-interaction=0.04). There were no meaningful interactions by race.

Conclusion:

The brain regions associated with OI impairment in individuals without dementia are specifically those regions known to be the primary targets of AD pathogenic processes. These findings highlight the potential utility of olfactory assessment in the identification and stratification of older adults at risk for AD.

Keywords: smell, olfaction, hyposmia, chemosensory, Alzheimer’s disease

BACKGROUND

The causes of olfactory impairment in older adults are multifactorial and range from viral illness and traumatic injury to sinonasal disease [1]. Olfactory deficits are also observed early in the course of several neurodegenerative conditions. In Parkinson’s disease (PD), hyposmia is a pre-clinical risk marker that can predate the onset of motor signs by up to ten years [2]. Multiple longitudinal antemortem studies have also established that olfactory deficits are observed in cognitively intact individuals who ultimately transition to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) at follow-up [3–5]. Olfactory information is projected sequentially from the olfactory bulbs and olfactory cortex to the amygdala and entorhinal cortex (ERC), and from the ERC to the hippocampus through the perforant pathway [6]. The neuroanatomic overlap between the olfactory system and key brain regions of interest in AD have contributed to the growing appreciation of olfaction as a promising sensory pathway for understanding neurodegenerative disease risk.

To date, the neuroanatomical correlates of olfactory identification (OI) impairment in cognitively normal (CN) older adults and MCI are not fully understood. The olfactory system becomes increasingly compromised during aging leading to reduced clearance of bacteria and other agents, fewer olfactory receptor neurons, regression of the olfactory vasculature and decreased regeneration capacity following injury [1]. Age-related olfactory loss is hypothesized to result from structural and functional changes in the nose, peripheral changes in the olfactory epithelium and olfactory bulbs, and/or abnormalities in the brain regions that subserve smell perception [1]. In middle-age, OI impairment is associated with atrophy in primary and secondary olfactory areas encompassing the orbitofrontal, piriform, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices, with longer duration of OI impairment associated with greater atrophy [7, 8]. In CN older adults, olfactory performance has been linked with amygdala and entorhinal gray matter volumes [9, 10]. One of the largest studies of olfaction and structural MRI to date found an association between impaired OI and abnormally low cortical thickness in regions affected in early AD, including the entorhinal, inferior/middle temporal, and fusiform cortices [11]. In MCI and early AD, olfactory loss was correlated with reduced olfactory cortex and left hippocampal volumes [12, 13], although not uniformly so [14].

Though prior investigations have examined the neuroanatomic associations of OI impairment, most studies were undertaken in predominantly White cohorts or small samples with absent or incomplete examinations of cognitive status. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study is a well-characterized sample of Black and White older adults with OI testing, structural neuroimaging, and expert-adjudicated cognitive status allowing for examination in earlier stages of disease risk. We used voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and region of interest (ROI) analyses to examine the neuroanatomic correlates of impaired OI in the absence of dementia. In CN individuals, we hypothesized that the amygdala, orbitofrontal and olfactory cortex would be associated with impaired OI. In individuals with MCI, we hypothesized that OI impairment would be associated with smaller medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions, including the amygdala, ERC and hippocampus.

METHODS

Study Population and Design

The ARIC Study is a population-based prospective investigation of 15,792 adults, aged 45 to 65 years at baseline (1987–1989). Participants were recruited from populations of four US communities in Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; and selected suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota. The ARIC Study has Institutional Review Board approval at all participating institutions. All participants gave written informed consent at each study visit. Further details of the protocol and sampling procedure are described elsewhere [15]. As part of the ARIC Neurocognitive Study (NCS) examination (ARIC visit 5; 2011 to 2013), a sample of participants from the fifth cohort examination without MRI contraindications completed a brain MRI scan (N=1,978). Selection criteria included: 1) participants with low cognitive test scores or declines on longitudinally administered tests and 2) an age-stratified random sample of participants without evidence of cognitive impairment, or 3) prior participation in a 2004 to 2006 ARIC Brain MRI Ancillary Study [16–18]. Additional details about the ARIC-NCS were described previously [19]. Of the 1,978 participants with visit 5 brain MRI scans, participants without olfactory data were excluded (N=87). Of note, Black participants were recruited primarily at two field centers (Forsyth County and Jackson). A small number of Black participants from Minneapolis and Washington County were excluded, as were a small number of Asian and Indigenous American participants (N=15). Participants with adjudicated dementia (N=99), as defined previously[16], with MRI data of insufficient quality for analysis (N=4), or missing covariate data (N=173), were also excluded. Our final analytic sample was 1,600 older adults. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of study inclusion/exclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subject inclusion/exclusion

CN=Cognitively Normal, MCI=mild cognitive impairment; *Due to the limited sample, Asian and Indigenous American (non-Black/non-White) participants and Black participants from Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington County, Maryland were excluded from the current analysis.

Cognitive Status

Cognitive status was determined by an expert adjudication panel using methods described in Supplementary Materials and previously [16]. Briefly, CN was defined as those participants with all ARIC-NCS cognitive domain z-scores > −1.5, and an absence of decline <10th percentile on one test or <20th percentile on two tests in the serial ARIC cognitive battery. A Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR[20]) sum of boxes score ≤0.5 and a Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ[21]) ≤5 was also required. MCI was defined as at least one domain z-score < −1.5, a CDR sum of boxes >0.5 and ≤3, an FAQ ≤5, and decline <10th percentile on one test or <20th percentile on two tests in the serial ARIC cognitive battery. In the analytic sample, 35% met criteria for MCI (N=564) and 65% were cognitively normal (N=1,036).

Olfactory Assessment

Odor identification was assessed at ARIC visit 5 using the 12-item Sniffin’ Sticks [22]. Participants were asked to smell and identify 12 common odorants using a multiple-choice format. Correctly identified odorants were assigned one point, with a total possible score of 12. A score of ≤6 was used to define OI impairment [22].

MRI Analysis

Brain MRI scans were performed using 3-Tesla scanners (Maryland: Siemens Verio; North Carolina: Siemens Skyra; Minnesota: Siemens Trio; Mississippi: Siemens Skyra). Each participant’s T1-weighted MRI was segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) probability map images using SPM12 unified segmentation[23] with the Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT; https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) tissue priors[24] and population-optimized segmentation settings [25]. For VBM analyses, the GM images were spatially normalized to the MCALT space, modulated and smoothed with an 8-mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel. The smoothed, modulated normalized GM images were then used in the SPM12 general linear model framework to estimate models of associations between the OI/MCI groups and GM volume on a voxel-wise basis with results displayed in VBM maps. For the ROI level analyses, an atlas consisting of 122 ROI labels, derived from the automated anatomic labeling atlas[26] was propagated from the MCALT space to each participant’s MRI native space using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) software [27]. The participant space atlas labels were used to parcellate each participant’s GM images into ROI. The GM volume for each ROI were computed by summing up the GM probabilities within each ROI and multiplying by the voxel volume. To obtain estimated total intracranial volume (eTIV), the GM, WM and CSF probabilities were summed and thresholded. Hole filling and morphological operations were performed to remove any spurious disconnected regions.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive sample characteristics were compared between CN participants with and without OI impairment and MCI participants with and without OI impairment. T-tests were used for group comparisons of continuous variables and chi-square tests were used for comparisons of categorical variables.

For VBM analyses, the SPM12 general linear model framework was used to estimate models of associations between the olfaction/MCI groups and GM volume on a voxel-wise basis with results displayed in VBM maps. Specifically, VBM was used to compare 1) CN with and without OI impairment and 2) MCI with and without OI impairment. Associations were adjusted for age, sex, and race. In sensitivity analyses, associations were adjusted for age, sex, race, and education. For all VBM analyses, correction for multiple comparisons were performed using a false discovery rate of p<0.05.

For ROI analyses, adjusted linear regression models were conducted to examine the association of olfactory impairment with a priori hypothesized ROIs, based on regions previously reported to be associated with OI impairment. These include the primary (olfactory and ERC, amygdala) and secondary olfactory areas (insula, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, hippocampus, and thalamus). The strength of the association (regression coefficients) was expressed as percent difference in ROI volume relative to the average size of the ROI volume in the reference group. In model 1, associations were adjusted for eTIV (mm3; continuous) and age (years; continuous). Prior work has demonstrated that several demographic and clinical factors can influence smell performance. As such, in our main adjusted model 2, eTIV (mm3; continuous), age (years; continuous), sex (men, women), race (white, Black), field center (Minneapolis, MN, Washington County, MD, Forsyth County, NC, Jackson, MS), education (<high school, high school, GED or equivalent, college, graduate, or professional school), body mass index (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (ever, never), hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, self-reported physician diagnosis of hypertension, or use of antihypertensive medications), diabetes (defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, or use of diabetes medications), prior head injury (self-reported or hospitalization with an International Disease Classification [ICD] code for head injury [28]), depression (defined as 11-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) score ≥9 [29]), and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4 genotype (0 ε4 alleles, 1 or 2 ε4 alleles) were included as covariates. We additionally added adjustment for performance on the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) in a supplemental Model 3 to further account for differences in cognitive status within the CN and MCI subgroups. In additional supplemental analyses, we evaluated the associations of continuous Sniffin’ Sticks score (expressed per 1-unit decrease in score) with ROI volumes. Given prior findings documenting olfactory differences by sex and race [30, 31], models were also stratified by race and sex to evaluate for interactions in the association of impaired OI with ROI volumes. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding individuals with PD and/or multiple sclerosis (N=14). Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses in all remaining ROIs.

Data Availability

All ARIC data can be accessed through the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) sponsored Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center at biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/aric-non. Additional information regarding ARIC can be found at sites.cscc.unc.edu/aric.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Study population characteristics are shown by olfactory and cognitive status in Table 1. Based on our criterion for OI impairment (score ≤6), approximately 10% of CN participants (N=101) and 18% of participants with MCI (N=103) were classified as anosmic. Participants had a mean age of 76 years; 60% of the participants were women and 28% were Black. Compared to CN participants with impaired OI, CN participants without OI impairment were of similar age and sex; were less likely to be Black (p<0.001); and more likely to have a high school education (p=0.002). Smoking status was similar between groups, as was the proportion of participants with hypertension, diabetes, and prior head injury (all p>0.05).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in the overall sample and by olfaction/cognitive status subgroups

| Overall (N=1,600) |

CN without OI impairment (N=935) |

CN with OI impairment (N=101) |

p-value | MCI without OI impairment (N=461) |

MCI with OI impairment (N=103) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor identification score, mean (SD) | 9.2 (2.3) | 10.0 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.2) | <0.001 | 9.6 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 27.4 (2.4) | 27.9 (2.0) | 26.6 (2.6) | <0.001 | 26.9 (2.4) | 25.4 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 76.2 (5.3) | 75.8 (5.3) | 76.9 (5.1) | 0.051 | 76.3 (5.2) | 77.8 (5.3) | 0.006 |

| Female, n (%) | 963 (60.2) | 597 (63.9) | 55 (54.5) | 0.063 | 263 (57.0) | 48 (46.6) | 0.054 |

| Black, n (%) | 440 (27.5) | 268 (28.7) | 55 (54.5) | <0.001 | 83 (18.0) | 34 (33.0) | <0.001 |

| Field center, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Forsyth County, North Carolina* | 400 (25.0) | 223 (23.9) | 19 (18.8) | 138 (29.9) | 20 (19.4) | ||

| Jackson, Mississippi | 411 (25.7) | 248 (26.5) | 52 (51.5) | 78 (16.9) | 33 (32.0) | ||

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 363 (22.7) | 207 (22.1) | 10 (9.9) | 128 (27.8) | 18 (17.5) | ||

| Washington County, Maryland | 426 (26.6) | 257 (27.5) | 20 (19.8) | 117 (24.5) | 32 (31.1) | ||

| Education, n (%) | 0.002 | 0.220 | |||||

| < High school | 200 (12.5) | 105 (11.2) | 23 (22.8) | 54 (11.7) | 18 (17.5) | ||

| High school, GED, or equivalent | 664 (41.5) | 375 (40.1) | 29 (28.7) | 212 (46.0) | 48 (46.6) | ||

| College, graduate, or professional school | 736 (46.0) | 455 (48.7) | 49 (48.5) | 195 (42.3) | 37 (35.9) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.4 (5.7) | 28.5 (5.4) | 28.3 (7.7) | 0.740 | 28.6 (5.8) | 27.8 (5.1) | 0.250 |

| Ever Smoking, n (%) | 911 (56.9) | 531 (56.8) | 58 (57.4) | 0.900 | 257 (55.7) | 65 (63.1) | 0.170 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1,193 (74.6) | 692 (74.0) | 76 (75.2) | 0.790 | 347 (75.3) | 78 (75.7) | 0.920 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 539 (33.7) | 296 (31.7) | 31 (30.7) | 0.840 | 172 (37.3) | 40 (38.8) | 0.770 |

| Prior head injury, n (%) | 424 (26.5) | 233 (24.9) | 26 (25.7) | 0.860 | 132 (28.6) | 33 (32.0) | 0.490 |

| Depression, n (%) | 102 (6.4) | 53 (5.7) | 3 (3.0) | 0.250 | 36 (7.8) | 10 (9.7) | 0.520 |

| APOE ε4 genotype, n (%) | 0.740 | 0.710 | |||||

| 0 ε4 alleles | 1,146 (71.6) | 689 (73.7) | 76 (75.2) | 313 (67.9) | 68 (66.0) | ||

| 1 or 2 ε4 alleles | 454 (28.4) | 246 (26.3) | 25 (24.8) | 148 (32.1) | 35 (34.0) |

Note: OI=Olfactory identification, CN=Cognitively Normal, MCI=Mild cognitive impairment, MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; P-values from t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Compared to MCI participants with impaired OI, MCI participants without OI impairment were younger (76 versus 78 years, p=0.006); of similar sex (57% versus 47% women, p=0.05); less likely to be Black (18% versus 33%, p<0.001); with similar levels of educational attainment (p=0.22). Smoking was comparable between MCI subgroups, as were the proportions with hypertension, diabetes, depression, and prior head injury (all p>0.05).

VBM Maps

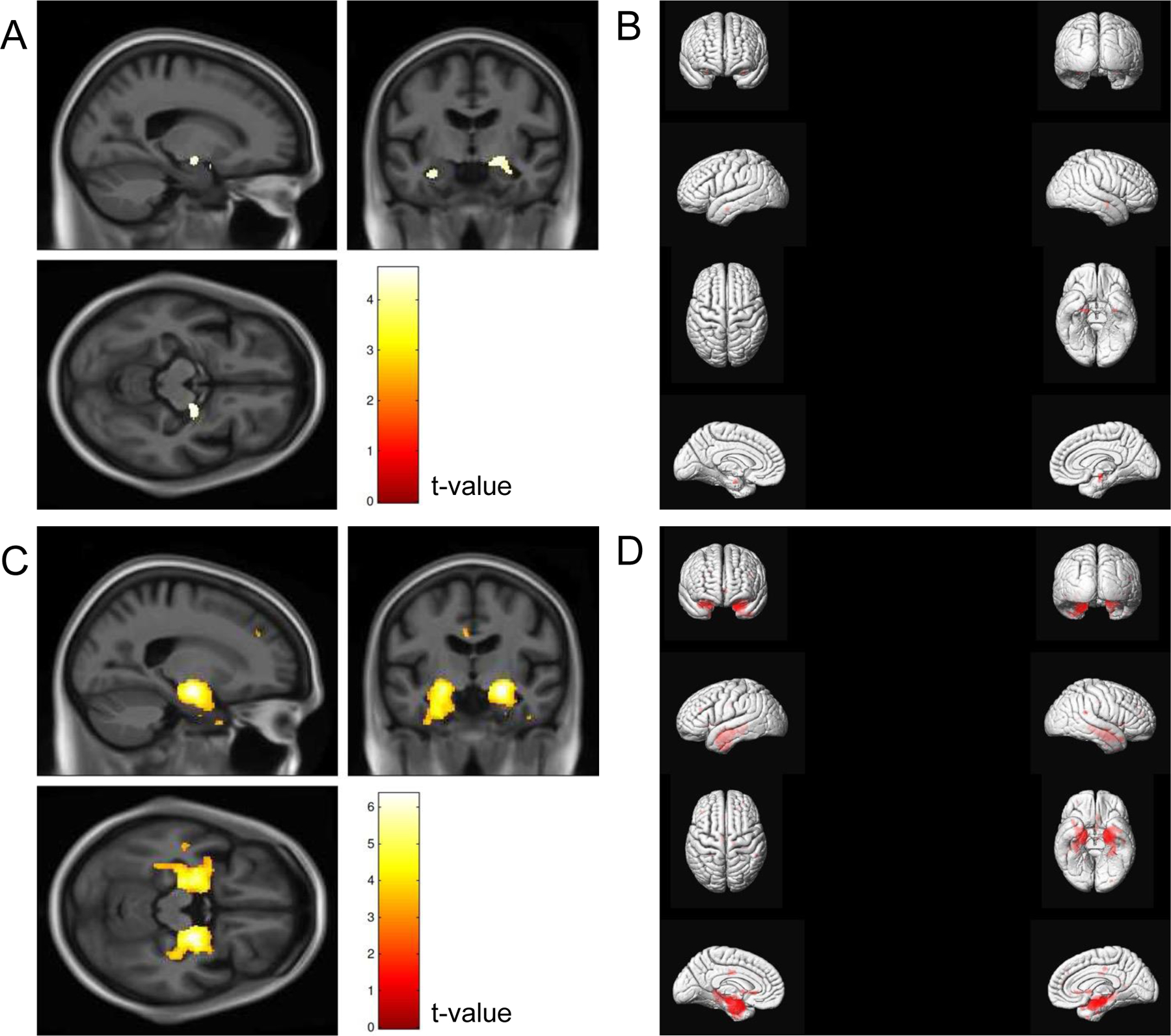

VBM group differences of GM between CN older adults with and without OI impairment are shown in panels A/B of Figure 2. In age, sex, and race-adjusted analyses, the VBM maps showed differences in a small portion of the left MTL (coordinates: 20 −9 12, t-value: 4.62, cluster size: 138 voxels). After further adjustment for education, there were no differences among CN older adults with and without OI impairment (all FDR corrected p-values >0.05). VBM group difference of GM between MCI with and without OI impairment are shown in panels C/D of Figure 2. The VBM maps showed differences in a larger area of the bilateral MTL, including the ERC and hippocampus (left MTL, coordinates: 21 −10 −15, t-value: 6.35, cluster size: 2,687 voxels; right MTL, coordinates: −21 10 14, t-value: 5.37, cluster size: 3,617 voxels). After further adjustment for education, associations were slightly attenuated but remained significant (left MTL, coordinates: 21 −10 −15, t-value: 6.25, cluster size: 2,512 voxels and right MTL, coordinates: −21 10 14, t-value: 5.30, cluster size: 3,479 voxels; Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Voxel-based morphometry maps comparing cognitively normal older adults with and without olfactory identification impairment (A and B; n = 1,036) and persons with MCI with and without olfactory identification impairment (C and D; n = 564)

Models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex (men, women), and race (White, Black). Correction was applied for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate with p <0.05. Odor identification impairment was defined as a score of ≤6 on the Sniffin’ Sticks Odor Identification Test. For panels B and D, the right and left hemispheres of the brain are depicted on the corresponding side of the figure.

ROI Analyses

Table 2 shows the adjusted associations of olfactory and cognitive status with a priori hypothesized ROI GM volumes. In the model adjusted for eTIV and age, OI in CN was associated with several brain regions (see Table 2). In the main adjusted model (Model 2), OI in CN was associated with smaller GM volumes only in the amygdala (−2.75%, 95% CI −4.42% to −1.09%) when compared to CN without OI. This association was robust to further adjustment for MMSE (Model 3). Associations of continuous Sniffin’ Sticks score with ROI volumes were similar to our main categorical analysis among CN (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Associations (regression ß-coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals) of cognition/olfaction groups with a priori hypothesized regions of interest (ROI) gray matter volumes expressed as percent differences in ROI volume relative to the average size of the ROI volume of the reference group.

| CN without OI impairment (N=935) |

CN with OI impairment (N=101) |

MCI without OI impairment (N=461) |

MCI with OI impairment (N=103) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entorhinal cortex | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −2.71 (−5.18, −0.26) | 0 (Reference) | −7.11 (−9.84, −4.37) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −1.31 (−3.65, 1.03) | 0 (Reference) | −5.97 (−8.57, −3.37) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −1.16 (−3.50, 1.19) | 0 (Reference) | −5.74 (−8.35, −3.12) |

| Hippocampus | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −2.76 (−4.52, −0.99) | 0 (Reference) | −5.76 (−7.66, −3.86) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −1.73 (−3.48, 0.01) | 0 (Reference) | −5.04 (−6.93, −3.15) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −1.54 (−3.30, 0.21) | 0 (Reference) | −4.79 (−6.69, −2.89) |

| Amygdala | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −2.51 (−4.17, −0.85) | 0 (Reference) | −5.29 (−7.19, −3.38) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −2.75 (−4.42, −1.09) | 0 (Reference) | −5.49 (−7.38, −3.61) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −2.55 (−4.22, −0.88) | 0 (Reference) | −5.31 (−7.21, −3.42) |

| Insula | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −2.06 (−3.96, −0.15) | 0 (Reference) | −2.33 (−4.34, −0.32) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −0.90 (−2.80, 0.99) | 0 (Reference) | −2.10 (−4.14, −0.06) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −0.65 (−2.55, 1.25) | 0 (Reference) | −1.83 (−3.89, 0.21) |

| Orbitofrontal | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −2.66 (−4.82, −0.51) | 0 (Reference) | −1.69 (−3.84, 0.46) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −1.24 (−3.36, 0.88) | 0 (Reference) | −1.13 (−3.32, 1.07) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −1.07 (−3.20, 1.06) | 0 (Reference) | −0.95 (−3.16, 1.26) |

| Anterior cingulate | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −3.16 (−6.45, 0.13) | 0 (Reference) | −1.47 (−4.75, 1.82) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −0.93 (−4.22, 2.36) | 0 (Reference) | −0.17 (−3.52, 3.19) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −0.77 (−4.07, 2.53) | 0 (Reference) | −0.27 (−3.65, 3.12) |

| Thalamus | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | −1.33 (−3.70, 1.03) | 0 (Reference) | 0.04 (−2.44, 2.52) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | −1.59 (−3.97, 0.79) | 0 (Reference) | 0.22 (−2.33, 2.77) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | −1.42 (−3.81, 0.97) | 0 (Reference) | 0.56 (−2.01, 3.12) |

| Olfactory cortex | ||||

| Model 1 | 0 (Reference) | 0.46 (−1.90, 2.83) | 0 (Reference) | −2.39 (4.92, 0.13) |

| Model 2 | 0 (Reference) | 0.41 (−2.00, 2.82) | 0 (Reference) | −2.76 (−5.33, −0.19) |

| Model 3 | 0 (Reference) | 0.38 (−2.05, 2.80) | 0 (Reference) | −2.51 (−5.10, 0.08) |

Note: OI=Olfactory identification, CN=Cognitively Normal, MCI=Mild cognitive impairment. Bolded estimates indicate p<0.05.

Model 1 adjusted for estimated total intracranial volume and age.

Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 + sex, race, field center, education, body mass index, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, prior head injury, depression, and APOE ε4 genotype.

Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 + Mini Mental State Exam score.

In sex-stratified analyses of CN participants, impaired OI was associated with hippocampal GM volume in CN women (−3.26%, 95% CI −5.71% to −0.80%) but potentially less so in men (0.53%, 95% CI −1.93% to 2.98%; p-interaction=0.052). There were no supported interactions by race in CN participants (p-interactions>0.1). Supplemental Table 2 and 4 show models stratified by sex and race in CN. Exclusion of CN participants with PD and/or multiple sclerosis (N=2) did not alter these findings (Supplemental Table 4).

We next examined the relationships with OI in MCI. In the main adjusted model (Model 2), OI impairment was associated with smaller GM volumes in the olfactory cortex (−2.76%, 95% CI −5.33% to −0.19%), entorhinal cortex (ERC; −5.97%, 95% CI −8.57% to −3.37%), hippocampus (−5.04%, 95% CI −6.93% to −3.15%), amygdala (−5.49%, 95% CI −7.38% to −3.61%), and insula (−2.10%, 95% CI −4.14% to −0.06%) when compared to MCI without OI. With further adjustment for MMSE (Model 3), associations with smaller insula and olfactory cortex volumes were no longer significant (see Table 2). Associations of continuous Sniffin’ Sticks score with ROI volumes were similar to our main categorical analysis among participants with MCI (Supplemental Table 1).

In sex-stratified analyses in MCI, impaired OI and insula GM volume were associated in men (−4.72%, 95% CI −7.38% to −2.06%) but less so in women (0.51%, 95% CI −2.68% to 3.70%; p-interaction=0.037). In race-stratified analyses in MCI, associations of impaired OI with smaller anterior cingulate GM volume were stronger (p-interaction=0.04) among White participants compared to associations among Black participants, but neither race-stratified association was significant. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 show sex- and race-stratified models in MCI. In sensitivity analyses, exclusion of MCI participants with PD and/or multiple sclerosis (N=12) slightly altered the findings; the association between impaired OI and insula GM volume was no longer statistically significant (Supplemental Table 4).

Exploratory associations between OI impairment with ROI GM volumes not hypothesized a priori were not statistically significant (Supplemental Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the neuroanatomic correlates of OI impairment in CN older adults and in persons with MCI using one of the largest samples of objective olfactory performance and structural MRI to date. The major study findings are that the primary brain regions associated with OI impairment in older adults without dementia are specifically those regions known to be targets of neurodegenerative pathogenic processes. Our findings in CN older adults indicate that OI impairment has fewer GM associations, limited primarily to the amygdala, when compared to the associations observed in MCI. In MCI, OI impairment was associated with broader medial temporal lobe (MTL) atrophy. Specifically, impaired OI in MCI was associated with smaller volumes in the olfactory cortex, amygdala, ERC and hippocampus. These associations were observed after accounting for the influence of several potentially confounding variables, including sociodemographic and physical health factors, and ApoE genotype.

In CN older adults, OI impairment may reflect the cumulative effects of exposure to air-borne environmental agents, including air pollution, cigarette smoke, viruses, and bacteria, which can first affect peripheral olfactory structures, including the nasal epithelium and olfactory bulbs, before abnormalities are observable in subcortical and cortical brains regions involved in central olfactory processing. However, smell loss also represents a pre-clinical risk marker in Parkinson’s disease, Lewy Body dementia (LBD), and Alzheimer’s dementia, with deficits observed prior to the development of overt cognitive impairment [2, 32]. Indeed, multiple studies have demonstrated that diminished baseline olfactory performance in cognitively intact older adults is associated with increased risk of MCI or dementia at follow-up [3–5]. In the current study, the primary neuroanatomic correlate of OI impairment in CN was the amygdala, a primary recipient zone of olfactory information from the peripheral olfactory system. Of note, the amygdala and hippocampus receive olfactory information independent of the thalamus as the olfactory bulbs are theorized to function as a central relay for olfactory input [33]. Prior work by den Heijer et al.[34] found that smaller baseline amygdala and hippocampal volumes in healthy older adults predicted subsequent development of dementia at 6-year follow-up. Furthermore, structural neuroimaging studies in CN older adults indicate an association between olfactory loss and reduced amygdala, perirhinal and entorhinal gray matter volumes [9, 10]. In the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging of 829 healthy older adults, impaired olfaction was associated with abnormal cortical thickness in AD-related regions, including the entorhinal and medial temporal cortices [11]. Expanding on this work, Lu et al.[35] examined resting-state functional connectivity in CN, early MCI, late MCI, and AD cohorts. Functional connectivity between the primary olfactory network and hippocampus was progressively more disrupted across these disease groups, with disruption significantly associated with the severity of cognitive impairment. Taken together, olfactory measures may serve as psychophysical probes of abnormal amygdala and hippocampal functioning in CN older adults, reflecting their role in olfactory processing and brain regions that are affected in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and LBD [36].

In MCI, OI impairment was associated with reduced olfactory cortex, amygdala, ERC, hippocampus, and insula volumes. Our findings correspond with prior work demonstrating olfactory abnormalities in MCI and AD, including loss of myelinated axons in the olfactory tracts, olfactory bulb and olfactory cortex atrophy, and reduced functional activation in primary olfactory regions during olfactory stimulation [13, 37–40]. Olfactory impairment in MCI and AD has also been linked with reduced amygdala, ERC and hippocampal volumes [9, 12, 13, 41–44]. Prestia and colleagues[45] examined longitudinal patterns of neurodegeneration using VBM and ROI analyses in CN and MCI. Individuals who ultimately converted to AD showed greater atrophy in the primary olfactory cortex and hippocampus compared to participants whose cognitive status remained stable. A subsequent study evaluated olfaction and neuroanatomic changes across a two-year period in MCI and found that a decrement in OI correlated with decline in hippocampal volumes [46]. These findings coincide with studies demonstrated a coupling of olfactory and memory trajectories in older adults when assessed longitudinally [47, 48], which has been attributed to the shared reliance of memory and olfaction on MTL brain regions. Indeed, a prior ARIC study found that memory impairment in MCI was associated with reduced MTL volumes [49]. Within our MCI group, individuals with OI impairment had lower MMSE scores compared to those without deficits in OI. Associations between OI impairment and MTL regions persisted after inclusion of MMSE as a covariate, which suggests that global cognitive status does not explain these findings. Collectively, these results, along with the aforementioned work by Lu et al. [35], further support the link between olfactory loss and degradation in MTL circuitry observed in prodromal AD.

Though it is widely believed that smell loss in older adults is a result of AD pathology in the olfactory–hippocampal circuitry, findings on OI and tau/amyloid burden have been mixed in ante-mortem human studies. Amyloid accumulation using 11C-PiB PET was associated with increased odds of OI impairment in two cognitively normal cohorts [11, 41]. A study of 565 older adults examined across a 15-year follow-up period to autopsy found that increased AD pathology was associated with higher within-person coupling of olfaction and memory decline [48]. Studies have also demonstrated that olfactory deficits did not vary as a function of amyloid burden alone [9, 42]; however, at least one of these investigations included long intervals (up to >5 years) between the time between PET scan and olfactory assessment. Studies examining the relationship between olfaction and tau burden are more limited but have noted an association between olfactory loss and increased temporoparietal tau in CN older adults [42]. Interestingly, more recent work has indicated that poor olfaction may be associated with increasing tau burden in individuals who are amyloid-positive. Klein et al.[50] found that impaired olfaction was correlated with tau burden in hippocampal and medial temporal cortex, but only in an amyloid-positive subgroup. Similarly, Lafaille et al. [51] examined the relationship between olfactory performance and CSF biomarkers in 274 CN adults with a family history of AD. The authors found no association between OI dysfunction and CSF Aβ1–42; however, poor odor identification was correlated with an increased CSF biomarker signature of AD, as reflected by a higher ratio of CSF t-tau and P181-tau to Aβ1–42. These finding cohere with a recent longitudinal study of olfactory performance and amyloid/tau PET imaging [52]. In this sample of CN older adults, accelerated olfactory decline was associated with a longitudinal increase in entorhinal tau burden and OFC amyloid burden, particularly in those individuals who were amyloid-positive. These findings highlight the potential utility of OI dysfunction as an early marker of AD risk.

The current study represents one of the largest studies examining the neuroanatomical correlates of OI impairment in a community cohort of Black and White older adults. The strengths include the large comprehensively phenotyped sample and expert adjudication of cognitive status, which allowed us to consider and adjust for multiple potential demographic, medical and cognitive confounders that can influence OI. The use of a voxel-by-voxel whole brain approach and a regional landmark-based approach to examine GM volume associations represents another strength of this work. Cortical thickness measures, which have shown relevance to AD symptom onset[53], have shown greater independence from genetic factors than volume-based measures [54]. However, Soldan et al. demonstrated the clinical utility of volume-based brain measurements in pre-clinical AD assessed across an 18-year follow-up period [55]. Rates of atrophy in bilateral entorhinal cortex and amygdala volumes were independently correlated with time to symptom onset. Future studies comparing the associations between these measurements and OI in the pre-clinical period of AD will be useful.

Limitations of this work include the single-domain olfactory assessment and an inability to examine the influence of medication use on our study findings. Prior reviews have noted multiple medications that can modulate human olfaction [56]; however, most of the drugs reported are based on anecdotal case reports in which olfactory functioning was assessed through self-report. To date, few studies have systematically examined medication-induced changes on formal psychophysical olfactory tests with case-control design. In addition, certain medications are associated with improved sense of smell, while others have been associated with a reduction in smell. Therefore, an overall examination of medication use on impaired OI remains a limitation of the current work.

The smaller samples for sex- and race-stratified analyses also limits the inferences drawn from these findings. Although our findings did not differ substantially by race, prior work in a national sample of older adults found greater smell loss in Black participants compared to White participants, even after accounting for demographic factors, cognitive functioning, and physical/mental health status [31]. It is possible that survival bias and the exclusion of participants with dementia may have influenced our results, as Black participants had higher rates of death than white participants prior to the fifth ARIC examination along with higher rates of dementia. Our sex-stratified analyses indicated that the neuroanatomical correlates of OI may differ based on sex. Women tend to outperform men on olfactory tasks and this advantage has been attributed to endocrine, social and cognitive differences observed between men and women [30]. Sex differences in olfactory-associated brain regions and APOE ɛ4 allele status have also been described. Burke et al.[57] examined longitudinal changes in hippocampal volume and white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in men and women who progressed to AD. Interestingly, hippocampal atrophy predicted conversion to dementia in women but not men, whereas WMH predicted progression in men but not women. Similarly, Shen et al.[58] found that sex and APOE ɛ4 allele status influenced longitudinal changes in hippocampal atrophy; women without dementia who were ɛ4 carriers had greater longitudinal hippocampal changes than men. At least one study found that verbal memory scores in cognitively normal women did not differ as a function of amyloid-positivity, whereas hippocampal volume was reduced in amyloid-positive women [59]. These findings underscore the need for future studies examining potential sex differences, longitudinal changes in structural brain regions and olfaction in aging and MCI.

With only two synapses between sensory environment and cortical targets, olfactory probes provide direct environmental access to the neural substrates implicated in AD. The current study represents one of the largest studies examining the neuroanatomical correlates of odor identification in Black and White older adults. Our results indicate that the primary brain regions associated with olfactory loss in older adults are targets of neurodegenerative disease. Thus, as supported by prior research, olfactory measures may serve as low-cost noninvasive risk markers that may enhance predictive algorithms for AD risk and could have utility in the identification and stratification of older adults at risk for cognitive decline. Future studies are needed to examine the predictive and classification utility, as well as the specificity of these findings across neurodegenerative conditions, including AD, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal dementia.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract nos. (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I, HHSN268201700005I). Neurocognitive data is collected by U01 2U01HL096812, 2U01HL096814, 2U01HL096899, 2U01HL096902, 2U01HL096917 from the NIH (NHLBI, NINDS, NIA and NIDCD), and with previous brain MRI examinations funded by R01-HL70825 from the NHLBI. Dr. Kamath has received support from KL2TR001077, R01AG064093 and R01NS108452. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

VK, HC, PP, THM, BGW, MG, DSK, RFG, CRJ, ARS, and ALCS receive research support from the NIH. BGW additionally receives research support from the Memory Impairment and Neurodegenerative Dementia (MIND) Center. DSK serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for a tau therapeutic for Biogen, but receives no personal compensation. He is a site investigator in the Biogen aducanumab trials. He is an investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the University of Southern California. He served as a consultant for Samus Therapeutics, Third Rock, Roche and Alzeca Biosciences but receives no personal compensation. RG is former Associate Editor for the journal Neurology and was provided florbetapir isotope (18F-AV-45) for investigator-initiated research by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly. CRJ serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche, has served as a speaker for Eisai, and consulted for Biogen, but he receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. He receives research support from the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Clinic. ALCS receives research support from the Department of Defense. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- [1].Doty RL, Kamath V (2014) The influences of age on olfaction: A review. Front Psychol 5, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen H, Shrestha S, Huang X, Jain S, Guo X, Tranah GJ, Garcia ME, Satterfield S, Phillips C, Harris TB, Health ABCS (2017) Olfaction and incident Parkinson disease in US white and black older adults. Neurology 89, 1441–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Devanand DP, Lee S, Manly J, Andrews H, Schupf N, Doty RL, Stern Y, Zahodne LB, Louis ED, Mayeux R (2015) Olfactory deficits predict cognitive decline and Alzheimer dementia in an urban community. Neurology 84, 182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schubert CR, Carmichael LL, Murphy C, Klein BEK, Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ (2008) Olfaction and the 5-year incidence of cognitive impairment in an epidemiological study of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 56, 1517–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yaffe K, Freimer D, Chen H, Asao K, Rosso A, Rubin S, Tranah G, Cummings S, Simonsick E (2017) Olfaction and risk of dementia in a biracial cohort of older adults. Neurology 88, 456–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Martinez-Marcos A (2009) On the organization of olfactory and vomeronasal cortices. Prog Neurobiol 87, 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bitter T, Gudziol H, Burmeister HP, Mentzel HJ, Guntinas-Lichius O, Gaser C (2010) Anosmia leads to a loss of gray matter in cortical brain areas. Chem Senses 35, 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Peng P, Gu H, Xiao W, Si LF, Wang JF, Wang SK, Zhai RY, Wei YX (2013) A voxel-based morphometry study of anosmic patients. Br J Radiol 86, 20130207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dhilla Albers A, Asafu-Adjei J, Delaney MK, Kelly KE, Gomez-Isla T, Blacker D, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Hyman BT, Betensky RA, Hastings L, Albers MW (2016) Episodic memory of odors stratifies Alzheimer biomarkers in normal elderly. Ann Neurol 80, 846–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Segura B, Baggio HC, Solana E, Palacios EM, Vendrell P, Bargallo N, Junque C (2013) Neuroanatomical correlates of olfactory loss in normal aged subjects. Behav Brain Res 246, 148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vassilaki M, Christianson TJ, Mielke MM, Geda YE, Kremers WK, Machulda MM, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Lowe VJ, Jack CR Jr., Roberts RO (2017) Neuroimaging biomarkers and impaired olfaction in cognitively normal individuals. Ann Neurol 81, 871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Murphy C, Jernigan TL, Fennema-Notestine C (2003) Left hippocampal volume loss in Alzheimer’s disease is reflected in performance on odor identification: A structural MRI study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 9, 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vasavada MM, Wang J, Eslinger PJ, Gill DJ, Sun X, Karunanayaka P, Yang QX (2015) Olfactory cortex degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 45, 947–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marigliano V, Gualdi G, Servello A, Marigliano B, Volpe LD, Fioretti A, Pagliarella M, Valenti M, Masedu F, Di Biasi C, Ettorre E, Fusetti M (2014) Olfactory deficit and hippocampal volume loss for rarly diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: A pilot study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 28, 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].The ARIC Investigators (1989) The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol 129, 687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, Wruck LM, Windham BG, Coker L, Schneider AL, Hengrui S, Alonso A, Coresh J, Albert MS, Mosley TH Jr. (2016) Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Prevalence: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). Alzheimers Dement 2, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Knopman DS, Penman AD, Catellier DJ, Coker LH, Shibata DK, Sharrett AR, Mosley TH Jr. (2011) Vascular risk factors and longitudinal changes on brain MRI: the ARIC study. Neurology 76, 1879–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mosley TH Jr., Knopman DS, Catellier DJ, Bryan N, Hutchinson RG, Grothues CA, Folsom AR, Cooper LS, Burke GL, Liao D, Szklo M (2005) Cerebral MRI findings and cognitive functioning: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Neurology 64, 2056–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Knopman DS, Griswold ME, Lirette ST, Gottesman RF, Kantarci K, Sharrett AR, Jack CR Jr., Graff-Radford J, Schneider AL, Windham BG, Coker LH, Albert MS, Mosley TH Jr., Investigators AN (2015) Vascular imaging abnormalities and cognition: mediation by cortical volume in nondemented individuals: atherosclerosis risk in communities-neurocognitive study. Stroke 46, 433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Morris JC (1997) Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 9, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr., Chance JM, Filos S (1982) Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 37, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G (1997) ‘Sniffin’ sticks’: Olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22, 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ashburner J, Friston KJ (2005) Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26, 839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schwartz CG, Gunter JL, Ward CP, Vermuri P, Senjem ML, Wiste HJ, Peterson RC, Knopman D, Jack CR (2017) The Mayo Clinic Adult Life Span Template: Better quantification across the life span Alzheimer’s and Dementia 13, 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Schwartz CG, Gunter JL, Chadwick P, Ward PV, Kantarci K, Senjem ML, Peterson RC, Knopman D, Jack CR (2018) Methods to improve SPM12 tissue segmentations of older adult brains. Alzheimers Dement, 1240. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M (2002) Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15, 273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC (2008) Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal 12, 26–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schneider ALC, Selvin E, Latour L, Turtzo LC, Coresh J, Mosley T, Ling G, Gottesman RF (2021) Head injury and 25-year risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 17, 1432–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sonsin-Diaz N, Gottesman RF, Fracica E, Walston J, Windham BG, Knopman DS, Walker KA (2020) Chronic Systemic Inflammation Is Associated With Symptoms of Late-Life Depression: The ARIC Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28, 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sorokowski P, Karwowski M, Misiak M, Marczak MK, Dziekan M, Hummel T, Sorokowska A (2019) Sex Differences in Human Olfaction: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol 10, 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pinto JM, Schumm LP, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, McClintock MK (2014) Racial disparities in olfactory loss among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69, 323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yoon JH, Kim M, Moon SY, Yong SW, Hong JM (2015) Olfactory function and neuropsychological profile to differentiate dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A 5-year follow-up study. J Neurol Sci 355, 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Keller A (2011) Attention and olfactory consciousness. Front Psychol 2, 380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].den Heijer T, Geerlings MI, Hoebeek FE, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM (2006) Use of hippocampal and amygdalar volumes on magnetic resonance imaging to predict dementia in cognitively intact elderly people. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63, 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lu J, Testa N, Jordan R, Elyan R, Kanekar S, Wang J, Eslinger P, Yang QX, Zhang B, Karunanayaka PR (2019) Functional connectivity between the resting-state olfactory network and the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Miller MI, Younes L, Ratnanather JT, Brown T, Trinh H, Lee DS, Tward D, Mahon PB, Mori S, Albert M, Team BR (2015) Amygdalar atrophy in symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease based on diffeomorphometry: the BIOCARD cohort. Neurobiol Aging 36, 3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thomann PA, Dos Santos V, Seidl U, Toro P, Essig M, Schroder J (2009) MRI-derived atrophy of the olfactory bulb and tract in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 17, 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Armstrong RA, Syed AB, Smith CU (2008) Density and cross-sectional areas of axons in the olfactory tract in control subjects and Alzheimer’s disease: an image analysis study. Neurol Sci 29, 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang H, Ji D, Yin J, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Ni H, Liu Y (2019) Olfactory fMRI activation pattern across different concentrations changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci 13, 786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Steffener J, Motter JN, Tabert MH, Devanand DP (2021) Odorant-induced brain activation as a function of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease: A preliminary study. Behav Brain Res 402, 113078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Growdon ME, Schultz AP, Dagley AS, Amariglio RE, Hedden T, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Albers MW, Marshall GA (2015) Odor identification and Alzheimer disease biomarkers in clinically normal elderly. Neurology 84, 2153–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Risacher SL, Tallman EF, West JD, Yoder KK, Hutchins GD, Fletcher JW, Gao S, Kareken DA, Farlow MR, Apostolova LG, Saykin AJ (2017) Olfactory identification in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment: Association with tau but not amyloid positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 9, 57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hagemeier J, Woodward MR, Rafique UA, Amrutkar CV, Bergsland N, Dwyer MG, Benedict R, Zivadinov R, Szigeti K (2016) Odor identification deficit in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease is associated with hippocampal and deep gray matter atrophy. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 255, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lian TH, Zhu WL, Li SW, Liu YO, Guo P, Zuo LJ, Hu Y, Yu SY, Li LX, Jin Z, Yu QJ, Wang RD, Zhang W (2019) Clinical, structural, and neuropathological features of olfactory dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 70, 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Prestia A, Drago V, Rasser PE, Bonetti M, Thompson PM, Frisoni GB (2010) Cortical changes in incipient Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 22, 1339–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lojkowska W, Sawicka B, Gugala M, Sienkiewicz-Jarosz H, Bochynska A, Scinska A, Korkosz A, Lojek E, Ryglewicz D (2011) Follow-up study of olfactory deficits, cognitive functions, and volume loss of medial temporal lobe structures in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res 8, 689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Dintica CS, Haaksma ML, Olofsson JK, Bennett DA, Xu W (2021) Joint trajectories of episodic memory and odor identification in older adults: patterns and predictors. Aging 13, 17080–17096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Knight JE, Bennett DA, Piccinin AM (2020) Variability and coupling of olfactory identification and episodic memory in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75, 577–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schneider ALC, Senjem ML, Wu A, Gross A, Knopman DS, Gunter JL, Schwarz CG, Mosley TH, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, Jack CR Jr. (2019) Neural correlates of domain-specific cognitive decline: The ARIC-NCS Study. Neurology 92, e1051–e1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Klein J, Yan X, Johnson A, Tomljanovic Z, Zou J, Polly K, Honig LS, Brickman AM, Stern Y, Devanand DP, Lee S, Kreisl WC (2021) Olfactory impairment is related to tau pathology and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 80, 1051–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lafaille-Magnan ME, Poirier J, Etienne P, Tremblay-Mercier J, Frenette J, Rosa-Neto P, Breitner JCS, Group P-AR (2017) Odor identification as a biomarker of preclinical AD in older adults at risk. Neurology 89, 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tian Q, Bilgel M, Moghekar AR, Ferrucci L, Resnick SM (2022) Olfaction, Cognitive Impairment, and PET Biomarkers in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Alzheimers Dis 86, 1275–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pettigrew C, Soldan A, Zhu Y, Wang MC, Moghekar A, Brown T, Miller M, Albert M, Team BR (2016) Cortical thickness in relation to clinical symptom onset in preclinical AD. Neuroimage Clin 12, 116–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Blangero J, Almasy L, Zilles K, Fox PT, Duggirala R, Glahn DC (2010) Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage 53, 1135–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Lu Y, Wang MC, Selnes O, Albert M, Brown T, Ratnanather JT, Younes L, Miller MI, Team BR (2015) Relationship of medial temporal lobe atrophy, APOE genotype, and cognitive reserve in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp 36, 2826–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lotsch J, Knothe C, Lippmann C, Ultsch A, Hummel T, Walter C (2015) Olfactory drug effects approached from human-derived data. Drug Discov Today 20, 1398–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Burke SL, Hu T, Fava NM, Li T, Rodriguez MJ, Schuldiner KL, Burgess A, Laird A (2019) Sex differences in the development of mild cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer’s disease as predicted by hippocampal volume or white matter hyperintensities. J Women Aging 31, 140–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shen S, Zhou W, Chen X, Zhang J (2019) Sex differences in the association of APOE epsilon4 genotype with longitudinal hippocampal atrophy in cognitively normal older people. Eur J Neurol 26, 1362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Caldwell JZK, Cummings JL, Banks SJ, Palmqvist S, Hansson O (2019) Cognitively normal women with Alzheimer’s disease proteinopathy show relative preservation of memory but not of hippocampal volume. Alzheimers Res Ther 11, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All ARIC data can be accessed through the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) sponsored Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center at biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/aric-non. Additional information regarding ARIC can be found at sites.cscc.unc.edu/aric.