Abstract

Background

Sunflower is an important ornamental plant, which can be used for fresh cut flowers and potted plants. Plant architecture regulation is an important agronomic operation in its cultivation and production. As an important aspect of plant architecture formation, shoot branching has become an important research direction of sunflower.

Results

TEOSINTE-BRANCHED1/CYCLOIDEA/PCF (TCP) transcription factors are essential in regulating various development process. However, the role of TCPs in sunflowers has not yet been studied. This study, 34 HaTCP genes were identified and classified into three subfamilies based on the conservative domain and phylogenetic analysis. Most of the HaTCPs in the same subfamily displayed similar gene and motif structures. Promoter sequence analysis has demonstrated the presence of multiple stress and hormone-related cis-elements in the HaTCP family. Expression patterns of HaTCPs revealed several HaTCP genes expressed highest in buds and could respond to decapitation. Subcellular localization analysis showed that HaTCP1 was located in the nucleus. Paclobutrazol (PAC) and 1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) administration significantly delayed the formation of axillary buds after decapitation, and this suppression was partially accomplished by enhancing the expression of HaTCP1. Furthermore, HaTCP1 overexpressed in Arabidopsis caused a significant decrease in branch number, indicating that HaTCP1 played a key role in negatively regulating sunflower branching.

Conclusions

This study not only provided the systematic analysis for the HaTCP members, including classification, conserved domain and gene structure, expansion pattern of different tissues or after decapitation. But also studied the expression, subcellular localization and function of HaTCP1. These findings could lay a critical foundation for further exploring the functions of HaTCPs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-023-04211-0.

Keyword: Sunflower, Shoot branching, TCP, Expression analysis, Functional analysis

Background

Plant architecture is one of the essential characteristics of ornamental plants. Shoot branching, as the primary component of plant architecture, includes the initiation of axillary meristems and the growth of axillary buds [1]. Axillary meristems are initiated at the axils of leaves to form buds [2], which can grow into lateral branches or become dormant. The dormant axillary buds can also be reactivated and grow into lateral branches. Generally, bud fate is affected by many regulation factors, such as genes, hormones, and environmental factors [2]. Among them, numerous genes have been revealed to control plant branch development, with TCP being a critical family.

TCP genes are widely involved in plant growth and development, including seed germination, floral asymmetry, gametophyte development, leaf senescence, circadian rhythms, and defense responses [3]. TCP protein was named after the initial member TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1 (TB1), CYCLOIDEA (CYC) and rice PROLIFERATING CELL FACT ORS1(PCF1) and PCF2 [4]. TCP proteins can be divided into two classes based on the differences within the TCP domain. Class I is also called the PCF subfamily in angiosperms, and class II is further subdivided into the CIN clade and CYC/TB1 clade [4].

BRC1, the most famous member of the TCP family, is mainly involved in branch development [3]. BRC1 is considered to be an integrator of several signalling networks, including hormonal, photochemical, and nutritional networks [5]. Auxin may unintentionally enhance bud BRC1 expression [6]. High cytokinin (CK) levels downregulate BRC1 expression, which activates axillary buds [7]. BRC1 expression was upregulated by strigolactone (SL), and shoot branching in the brc1 mutant was insensitive to SL [6, 8, 9], indicating BRC1 acted downstream of SL. Active PHYB suppressed the expression of the SbTB1 gene in sorghum, leading to high plant branching, and a low R/FR ratio favored AtBRC1 upregulation. A slight decrease in the photosynthetic leaf area is associated with stimulation of TB1 expression in sorghum seedlings and, consequently, a lower propensity of tiller buds to grow out [10]. All these findings indicate that BRC1 expression is very sensitive to light intensity and quality. Applying sucrose to rose axillary buds reduced the expression level of RhBRC1 [11]. Increasing the sucrose level in pea plants will significantly inhibit the expression of BRC1 [5]. In addition, TIE1 can inhibit the transcriptional activity of BRC1 from regulating shoot branching [12].

A crucial component of cut flowers is the sunflower. To ensure the quality of the top flower, it must remove buds repeatedly throughout cultivation, raising the cost of the final product. Therefore, producing new sunflowers with few or no branches is crucial. This study characterised the genes of the sunflower TCP family, and examined the evolutionary relationships, gene structures, conserved domains, cis-elements, gene expression patterns, subcellular localization, and function of HaTCP1. Our study lay the theoretical groundwork for further investigations into the roles of HaTCP genes in shoot branching.

Results

Identification and classification of TCP members in sunflower

Thirty-four sunflower TCP proteins were identified and named HaTCP1-HaTCP34. Protein sequence length, molecular weight (MW), and isoelectric point (IP) were all analyzed. The number of amino acids (aa) encoded by the TCP family genes was between 127 aa (HaTCP33) and 497 aa (HaTCP8), with an average of 322.9 aa. The MW of the TCP family proteins was between 14.21 (HaTCP33) and 53.42 KDa (HaTCP8). Subcellular localization predicted that TCP proteins were all localized in the nucleus (Table S1).

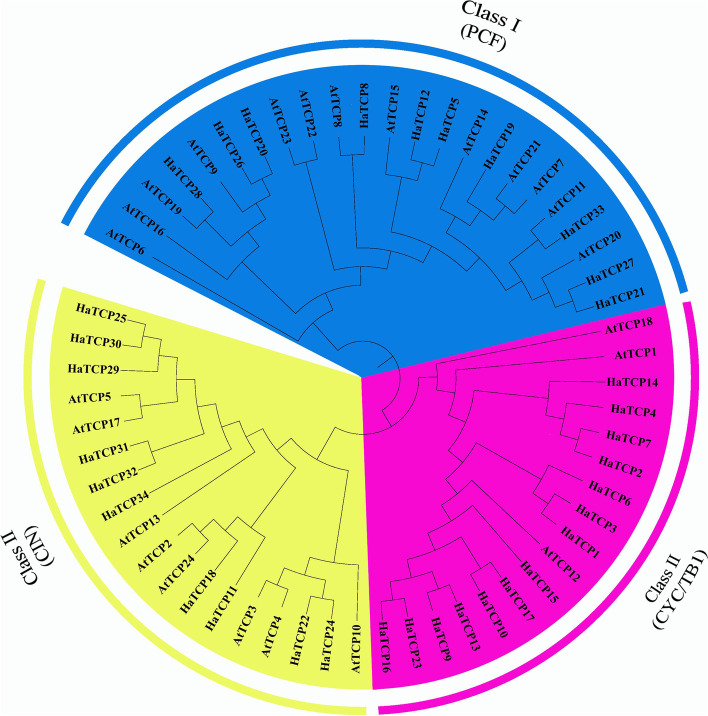

Phylogenetic analysis of the TCP members

TCP proteins of the Arabidopsis and sunflower were all arranged into a phylogenetic tree to examine the evolutionary relationships between the various members of the sunflower TCP family. The TCP proteins from 24 Arabidopsis and 34 sunflowers revealed clear evolutionary grouping. As shown in Fig. 1, the TCP family can be divided into two subfamilies: class I and II. And class II TCP members were further divided into CIN and CYC/TB1 subfamilies [13]. The three subfamilies contained 10, 10, and 14 HaTCP members, respectively. CYC/TB1 accounts for 41.2% of the total HaTCP proteins. In this subfamily, AtTCP1, AtTCP12, and AtTCP18 all play a role in shoot branching, indicating that these HaTCP genes may also be involved in regulating shoot branching.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary tree of TCPs

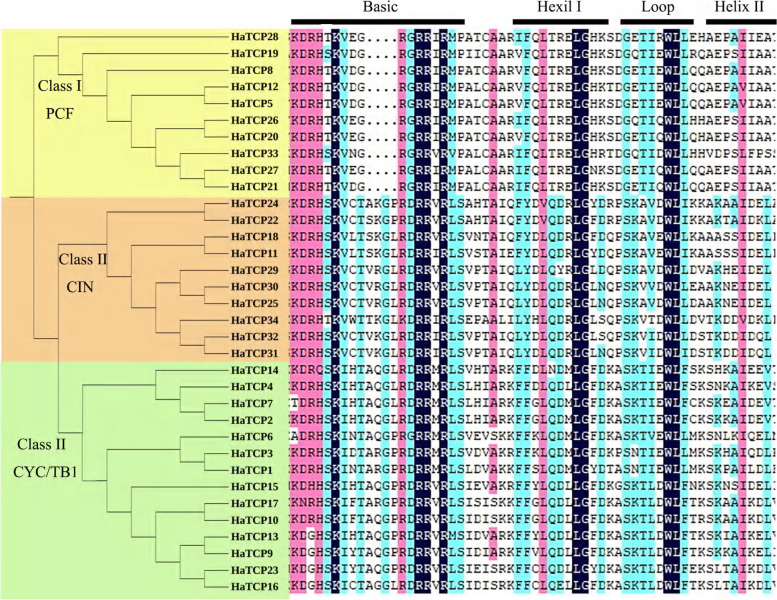

Gene structure and conserved motifs of TCP in sunflower

We investigated the gene structure of HaTCP genes, and we found that all the HaTCP genes have no introns. To analyse the conservation and diversity of the TCP domain regions in HaTCP proteins, a multiple sequence alignment was performed using DNAMAN software based on the amino acid sequences of each TCP domain (Fig. 2). Alignment results showed that sunflower TCP proteins contained a typical TCP conservative domain: a bHLH domain, including a basic region, a loop region, and two helical regions (Helix I and II). Compared with class II, class I had four amino acid deletions in the basic region, which is similar to the structure of TCP proteins in other species, indicating the conservatism of TCP members in the evolution of different species.

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of the conserved domains of TCP proteins in sunflower

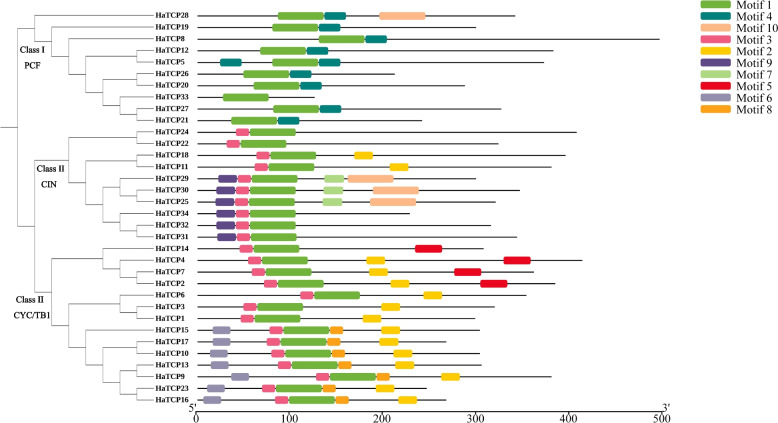

Next, we performed a conserved motif analysis of the HaTCP proteins using MEME software to observe their diversity of motif composition (Fig. 3). As seen in Fig. 3, a total of 10 conserved motifs were found. Motif 1 is a TCP conservative domain shared by all TCP proteins. Almost all the HaTCP proteins in the same branch of the evolutionary tree possess a similar motif composition. At the same time, significant differences can be seen in different branches, indicating that HaTCP members in the same branch could play similar roles. However, some motifs only exist in specific branches. For example, motif four and motif 3 only existed in class I or II, respectively, indicating that the genes possessing these motifs may perform particular functions.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the conserved motifs of HaTCP proteins

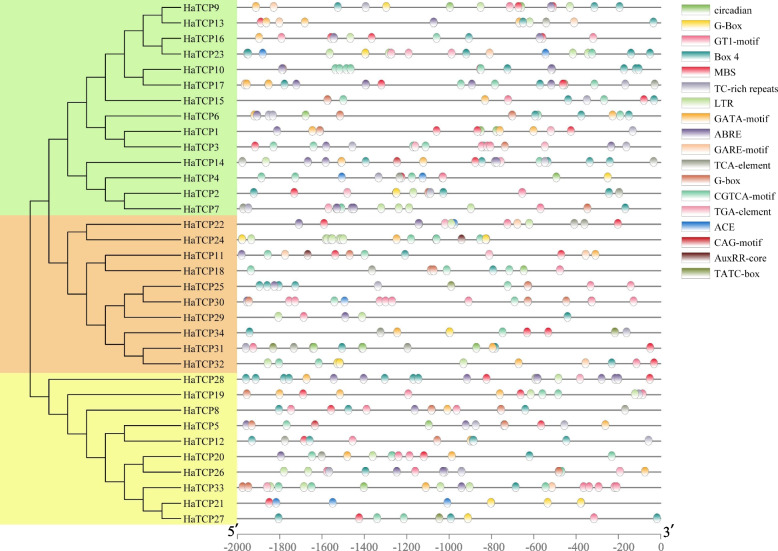

The Cis-elements in the promoters of TCP genes in sunflower

The 2000 bp promoter sequences of the HaTCP genes were extracted and submitted to the PlantCARE database to detect cis-acting elements. As depicted in Fig. 4, there were various hormone and stress response elements and many light response elements. Five hormone-related elements were auxin response elements (TGA-element, AuxRR-core), gibberellin (GA) response elements (GARE-motif, TATC-box), salicylic acid (SA) reaction element (TCA-element), jasmonic acid (JA) reaction element (CGTCA-motif), abscisic acid (ABA) reaction element (ABRE). Three elements involved in stress were defense and stress response element (TC-rich repeats), MYB binding sites (MBS) involved in drought induction, and cryogenic reaction element (LTR). The light-responsive element G-box were the most abundant elements in the promoter regions of 34 HaTCPs, with 33 promoters containing the element. GATA-motif was found in 21 promoters. Twenty-three HaTCP gene promoters had Box 4 and GT1-motif. CAG-motif, ACE, MREand AE-box were detected in 2, 5, 12, and 14 promoters of HaTCP genes, respectively. The above promoter analysis revealed that the expression of TCP family genes is widely involved inplant responses to environmental stress and hormones (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Cis-acting element analysis of promoters of HaTCPs

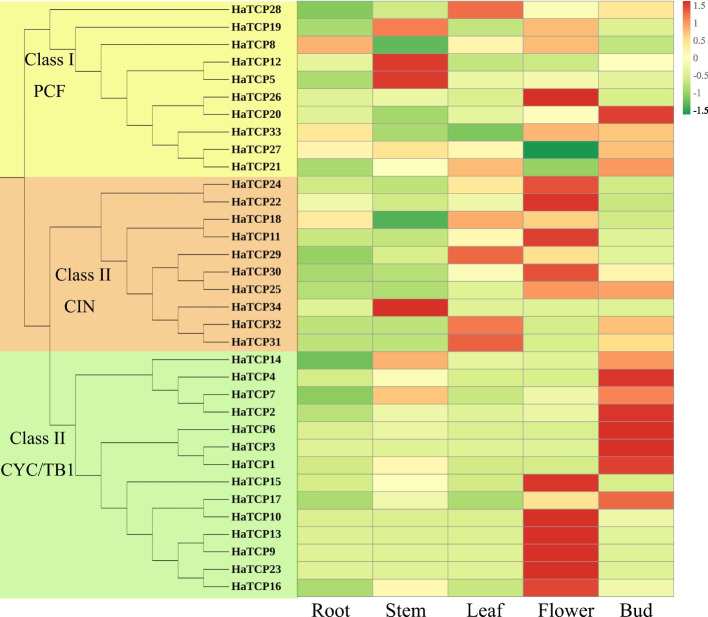

Expression analysis of different tissues of HaTCP genes

Based on transcriptome data from five tissues, including roots, stems, leaves, buds, and flowers, the expression profiles of HaTCPs were examined to investigate the potential roles of these genes in plant growth and development (Fig. 5). We detected the expression of 34 HaTCP genes, 11 HaTCP genes presented the highest expression level in flowers, indicating that they might play an essential role in sunflower flower development. HaTCP12, HaTCP5, and HaTCP34 expressed the highest in the stem. HaTCP20, HaTCP27, HaTCP21, HaTCP14, HaTCP4, HaTCP7, HaTCP2, HaTCP6, HaTCP3, HaTCP1 and HaTCP17 in buds were higher than that in any other tissue, revealing the potential functions of these genes in shoot branching.

Fig. 5.

Tissue expression analysis of HaTCP genes

Expression analysis of the HaTCP genes after decapitation

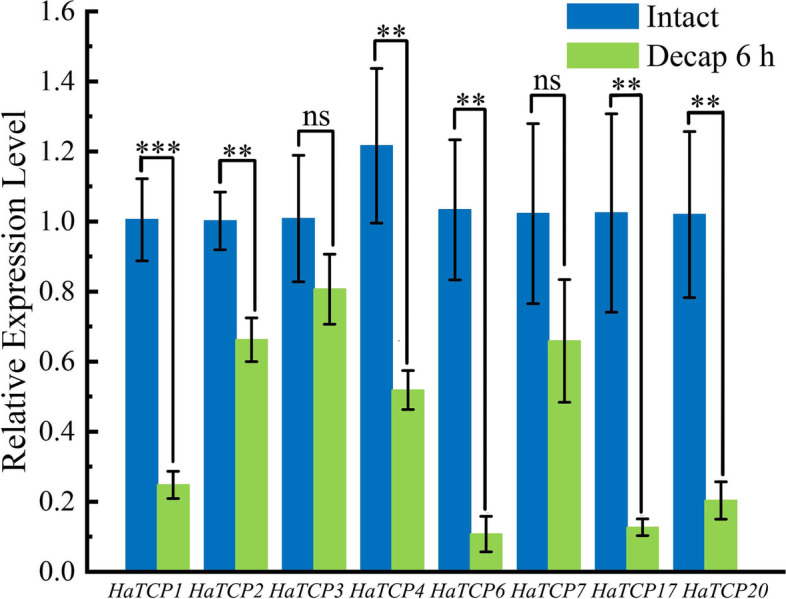

We selected the genes with the highest expression level in axillary buds and detected the expression level of these genes. According to the Müller’s study, we chose 6 h after decapitation as the treatment time [14]. Our results demonstrated that, other genes, excluding HaTCP3, were all significantly downregulated, with HaTCP1, HaTCP17, and HaTCP20 being downregulated to 0.24, 0.13, and 0.21 of the control, respectively (Fig. 6). These results suggest that these genes may play an important role in axillary bud germination after decapitation. Through similarity comparison, we found that HaTCP1 and AtBRC1 were closely related, indicating that HaTCP1 is a homologous gene of AtBRC1. Therefore, we selected HaTCP1 for further research.

Fig. 6.

Relative expression analysis of TCP genes in sunflower. The significant differences are indicated by * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns (not significant)

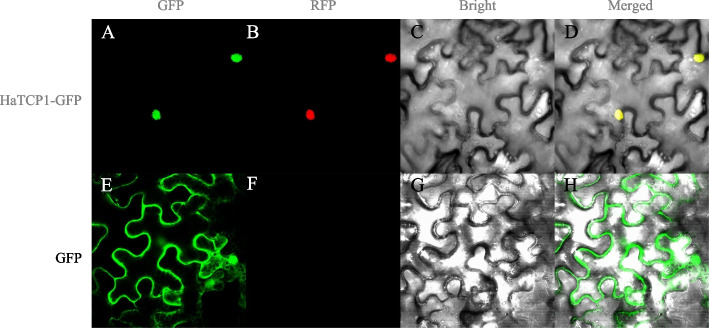

Subcellular localization analysis of HaTCP1

The constructed HaTCP1-GFP vector was transformed into tobacco leaves, and the GFP signal was visualized under a laser confocal microscope. Figure 7 showed that both the HaTCP1-GFP green fluorescence signal and the red fluorescence signal of the nuclear marker were distributed in the nucleus, indicating that HaTCP1 was localized in the nucleus.

Fig. 7.

Subcellular localization analysis of HaTCP1. A E Green fluorescence images of HaTCP1-GFP protein and GFP (control). B F Red fluorescence image of marker for nucleus localization. C G Bright-field images of HaTCP1-GFP protein and control. D H The merged images of HaTCP1-GFP protein

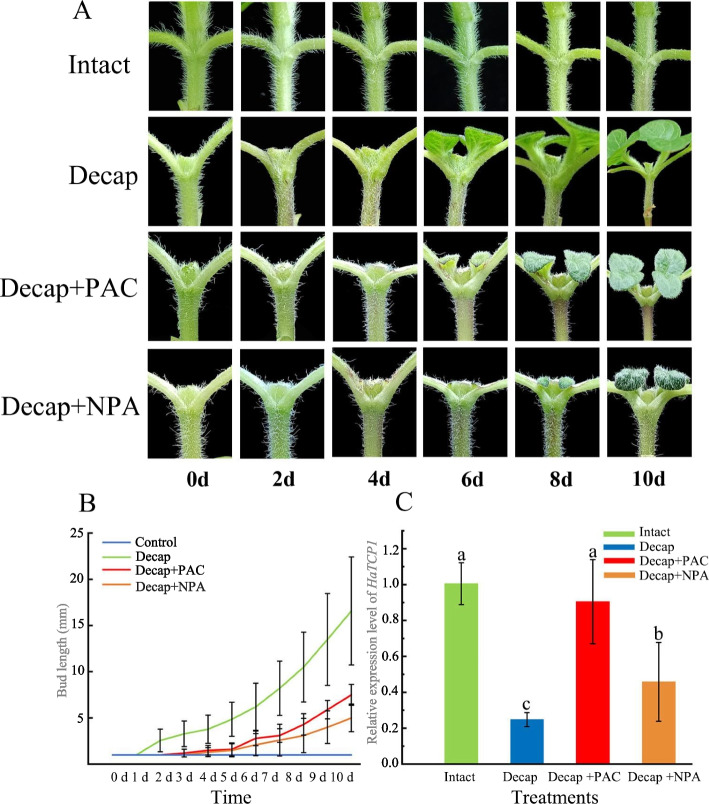

Expression analysis of HaTCP1 under different treatments

Solutions of gibberellin synthesis inhibitor (PAC) and auxin transport inhibitor (NPA) were given to the axillary buds of decapitated sunflower plants to study the effects of GA and auxin transport from the axillary bud to the stem on bud outgrowth (Fig. 8A). Then the relative expression of the HaTCP1 under different treatments was examined using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The results showed that the axillary bud germinated after decapitation and reached 19 mm on the 10th day, while NPA and PAC significantly inhibited the axillary bud germination (Fig. 8B). This indicates that inhibiting auxin transport and GA synthesis can effectively retard axillary bud growth but can not wholly inhibit axillary bud germination. The treated axillary buds were sampled 6 h after the treatment, and the HaTCP1 expression levels were detected by qRT-PCR. Application of PAC or NPA following decapitation both raised the level of HaTCP1 expression compared to decapitation, showing that both treatments' effects on the development of axillary buds were caused, at least in part, by controlling the expression of this gene (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Axillary bud development and HaTCP1 expression analysis induced by decapitation. A Axillary bud growth after 10 d of treatment. B Statistics of axillary bud length of sunflower after treatment for 10 d (n = 10). C The relative expression level of HaTCP1 after 6 h of treatment. The data are mean ± SE

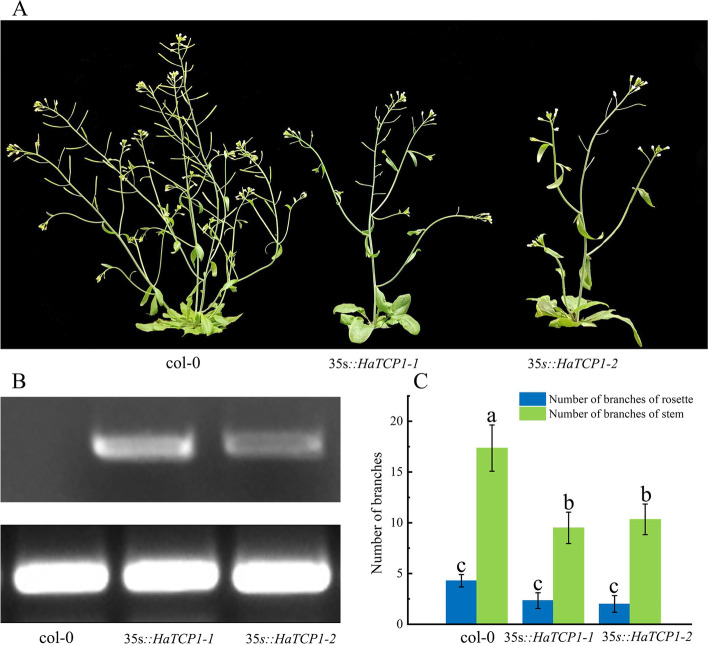

HaTCP1 inhibits shoot branching

To verify the HaTCP1 function, ten Arabidopsis-overexpression lines were generated. Two separate transgenic lines were selected for observation and statistical analysis further to analyze the levels of gene expression and shoot branching. Semi-quantitative PCR analysis confirmed high HaTCP1 gene expression in overexpression lines compared to Columbia-0 (Col-0) plants (Fig. 9B). We noticed that HaTCP1 overexpression resulted in fewer stem and rosette branches in 38-day-old seedlings compared to the Col-0 (Fig. 9A, C). In contrast to the Col-0, which had 4.3 rosette branches, the two transgenic lines had an average of 2 and 2.3 rosette branches each. Compared to the Col-0, which had 17.4 stem branches, transgenic overexpression lines had 9.5 and 10.3 stem branches, respectively. These results indicate that HaTCP1 negatively regulates shoot branching in sunflowers.

Fig. 9.

Analysis of the phenotype and gene expression in transgenic HaTCP1-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. A Transgenic and Col-0 Arabidopsis plants. B In-gel electrophoresis detection of HaTCP1 expression from the leaves of Arabidopsis Col-0 plants and HaTCP1-overexpressing transgenic plants. C Primary rosette or stem branches per plant were counted (n = 15)

Discussion

Plant-specific transcription factors TCPs play various roles in plant growth and development aspects. Although the TCP transcription factors have been identified in a wide range of plant species, such as Arabidopsis [15], rice [15], tomato [16], tobacco [17], and strawberry [18], little is known in sunflowers. In this study, we identified 34 putative HaTCP genes. Like other species, HaTCPs were divided into three subfamilies: PCF, CYC/TB1, and CIN [15].

Different types of TCP transcription factors have other functions. Studies showed that class II TCP members controlled stem branching [5, 19]. The CIN subclade TCP genes interfere with several cellular pathways controlling leaf development [20]. Class I (PCF) TCP factors primarily induce cell division and promote plant growth [4]. Therefore, these HaTCP members belonging to different subfamilies may have corresponding functions.

We analysed the distribution of motifs and found that HaTCP members from the same group or subgroup shared a similar motif composition. In class I and class II subgroups alone, for instance, motif 4 and motif 3 were found (Fig. 3). The hydrophobic amphiphilic helix (the first helix) may control protein–protein interaction through the HaTCP genes, allowing for the formation of homologous and heterologous dimers [21]. However, there are structural differences between classes I and II, such as the four amino acid deletions in the basic region of class I members. The consistency of the motif compositions and gene structures of HaTCP genes further supported the close evolutionary relationships.

Most of the TCPs have cis-regulatory elements related to light responses (AE-box, BOX4, GBOX, GT1-motif and GATA-motif). Furthermore, the different TCP members possessed other hormone-related characteristics, such as ABRE (ABA), AuxRR-core/TGA-element (auxin), CGTCA-motif (MeJA), GARE-motif/TATC-box (gibberellin), and TCA-element (SA). These results indicated that the HaTCP genes might influence response to plant hormones.

The TCP genes are involved in plant growth and development and could respond to multiple abiotic stresses. The analysis of promoter regions showed that some TCPs contained TC-rich repeats, LTR cis-regulatory elements, and MBS cis-regulatory elements, suggesting that the HaTCP genes might play a significant role in stress responses.

Gene expression patterns provide important information related to gene functions [22]. Among the genes expressed highest in leaves, HaTCP29, HaTCP31, and HaTCP32 are closely related to AtTCP5. However, AtTCP5 was proven to be involved in controlling leaf margin development [23], indicating that HaTCP29, HaTCP31, and HaTCP32 may play an essential role in regulating the development of sunflower leaves. HaTCP12 and HaTCP5 showed the highest expression in stems, and the two genes are closely related to AtTCP5. Previous studies have shown that TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length in Arabidopsis [24], indicating that HaTCP12 and HaTCP5 might be involved in regulating the development of sunflower stems.

Application of NPA inhibited the initiation of AMs in the maize inflorescence [25]. The mutation of PIN-FORMED1 (PIN1) resulted in a pin-like stem architecture [26]. AM formation is strongly compromised in the polar auxin transport mutant barren inflorescence2 (bif2) [27, 28]. These studies indicate that transport is required for axillary meristem formation.

Some studies also showed that NPA did not affect the initialbud outgrowth after decapitation but only affected the growth of axillary buds after germination [29]. Our study found that applying NPA after sunflower decapitation significantly delayed the germination of axillary buds but did not wholly prevent the germination of axillary buds.

The role of gibberellin in branching has remained obscure. GA is often viewed as a branching inhibitor because GA-biosynthesis and -perception mutants exhibit more branches [30]. At the same time, studies in Jatropha suggested that GA application promotes bud outgrowth [31]. According to our research findings, endogenous gibberellin was essential for the proper germination of axillary buds since its inhibition significantly slowed the germination of axillary buds. The detection of HaTCP1 expression level revealed that the application of NPA and PAC significantly promoted the up-regulation of HaTCP1 expression level, indicating that the inhibition of auxin transport and gibberellin synthesis was at least partially mediated by regulating the expression of HaTCP1, thereby inhibiting the growth of axillary buds.

Many TCPs, such as TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 (TB1) from maize, Arabidopsis BRC1 and BRC2, and rice PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR, were all involved in plant branching [3]. The ectopic overexpression of these genes significantly reduced lateral branching [32]. Similarly, HaTCP1 is located in the nucleus and features typical transcription factor characteristics, and its overexpression in Arabidopsis decreased the number of rosette branches and stem branches. The expression analysis of HaTCP1 under different treatments and the phenotype of Arabidopsis plants overexpressed HaTCP1 showed that HaTCP1 could negatively regulate sunflower branching.

Conclusion

In summary, 34 TCP genes were identified in sunflowers and were divided into three subfamilies. A comprehensive analysis of phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, and expression profiles was also performed. We observed similar exon–intron structures and protein motif distribution patterns for HaTCP genes. Expression analysis of sunflower TCP family genes in different tissues revealed that HaTCP genes showed strong tissue specificity. Decapitation causes a significant decrease in the expression level of HaTCP1, HaTCP17, and HaTCP20. In addition, NBA and PAC significantly inhibited the germination speed of axillary buds in sunflowers, which is related to the change in the HaTCP1 expression level. The overexpression of HaTCP1 significantly reduced the number of Arabidopsis stem branches and rosette branches. Our study lays a solid foundation for future sunflower TCP function exploration and provides a reference for TCP gene studies.

Methods

Plant materials

Seeds of Helianthus annuus cv ‘huoli’, Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) and transgenic plants, Nicotiana benthamiana, were sown in pots (5 × 5 cm) and placed in an artificial climate chamber. The light intensity is 5500 LX, the light cycle is 16/8 h (light/dark), and the temperature is 20 ± 2 ℃. All plant materials were grown in feld of plant growth chamber, College of Horticulture, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, Anhui.

Identification of TCP genes in sunflower

The whole genome sequence of sunflower was downloaded from the ensemble database (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-44/fasta/helianthus_annuus/). The sunflower TCP family genes were identified through the simple HMM search tool of Tbtools software. After deleting repetitive sequences and genes not containing the TCP domain, the TCP family members were finally determined. The physical and chemical properties of sunflower TCP proteins, including molecular weight (MW), protein sequence length and isoelectric point (IP), were assessed with the online software ExPASY (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/). To predict the subcellular localization of the identified HaTCP proteins, WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TCP proteins

The TCP protein sequences of sunflower and Arabidopsis were compared by MEGA 11 software. The neighbour-joining method constructed the phylogenetic tree with a boot-strap value based on 1000 replicates. Arabidopsis TCP protein sequences were obtained from the UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org/).

Analysis of motifs and gene structure

Te conserved motifs for each HaTCP member were analyzed using MEME Suite version 5.0.5 (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/). The gene structures of the HaTCPs were determined by the online Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) 2.0 software (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/).

Analysis of Cis-elements in promoters

The upstream 2000 bp sequence of HaTCP genes in the sunflower genome was extracted. The plant care online website (http://bioinformatics.psb. ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was used to predict plant cis-acting elements, and the predicted results were drawn out using the Basic Biosequence View tool of Tbtools.

Expression analysis of HaTCP genes in different tissues or under different treatments

The tissue-specific expression analysis was performed according to the method reported by Dong et al. [33]. For the decapitation, NPA and PAC experiment, thirty-day-old seedlings of H. annuus cv ‘huoli’ were divided into four groups. One group was used as intact, the second group was decapitated, and the third and fourth groups were treated with 10 ul NPA (1 M) or PAC (100 mM) solution after decapitation. Take photos of the treated axillary buds every other day and measure the length of the axillary buds. Take samples of axillary bud at 0 or 6 h after treatments. The expression level of HaTCP1 or other genes was detected by qRT-PCR, and eF1A [34]. was employed as the internal control (Table S2).

Subcellular localization

The coding regions of HaTCP1 were amplified with primers TCP1-F/TCP1-R. Vector construction, tobacco injection and fluorescence observation were carried out according to the method reported by Dong et al. [33].

Overexpression of HaTCP1 and phenotype analysis in arabidopsis

The 35S::HaTCP1 was transformed to Arabidopsis according to the method reported by Dong et al. [33]. The expression level of HaTCP1 was detected by qRT-PCR. The number of branches with a bud length ≥ 10 mm was scored, and the height of the main stems were measured for phenotype analysis.

Statistical analysis

All the data in this study was presented as mean value ± SD. Tukey’s tests were performed for statistical analyses.

Plants were sourced as follows

Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) was obtained from NASC (NASC ID: N1092) and grown continuously in the Laboratory of Associate professor Lili Dong. It was verifed by Associate professor Lili Dong from her seed stock registrar and confrmed by visual examination of plants that are grown for seed stocks.

Helianthus annuus cv‘huoli’ and Nicotiana benthamiana were obtained and verifed by Associate professor Lili Dong after cultivation at the laboratory in Anhui Agricultural University.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Table S1. Physicochemical properties of TCP members in Sunflower.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Primer sequences.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

L.D., X.D., and T.W. designed the research project and drafted the manuscript. Y.W., J.Z. and C.L. completed the experiments. All authors approved the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Anhui Province of China (grant number: 1808085MC85) and the Excellent Young Talents Support Plan of Anhui Province College and Universities (grant number: gxyq2019010).

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online. “The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, GSE221055 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE221055.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was not carried out on animal or endangered species. We declare that all the experimental plants were collected with permission from local authorities of agricultural department and the plant materials in the experiment were collected and studied in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yu Wu and Jianbin Zhang are co-first author.

References

- 1.Bennett T, Leyser O. Something on the side: axillary meristems and plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60(6):843–854. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2763-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teichmann T, Muhr M. Shaping plant architecture. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:233. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martín-Trillo M, Cubas P. TCP genes: a family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S. The Arabidopsis thaliana TCP transcription factors: a broadening horizon beyond development. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10(7):e1044192. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2015.1044192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M, Le Moigne MA, Bertheloot J, Crespel L, Perez-Garcia MD, Ogé L, Sakr S. BRANCHED1: a key hub of shoot branching. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:76. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilar-Martínez JA, Poza-Carrión C, Cubas P. Arabidopsis BRANCHED1 acts as an integrator of branching signals within axillary buds. Plant Cell. 2007;19:458–472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun N, de Saint Germain A, Pillot JP, et al. The pea TCP transcription factor PsBRC1 acts downstream of strigolactones to control shoot branching. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(1):225–238. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dun EA, de Saint GA, Rameau C, Beveridge CA. Antagonistic action of strigolactone and cytokinin in bud outgrowth control. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:487–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revel SM, Bart JJ, Luo Z, Oplaat C, Susan EL, Mark WW, et al. Environmental control of branching in petunia. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:735–751. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kebrom TH, Mullet JE. Photosynthetic leaf area modulates tiller bud outgrowth in sorghum. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38(8):1471–1478. doi: 10.1111/pce.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M, Pérez-Garcia MD, Davière JM, Barbier F, Ogé L, Gentilhomme J, Sakr S. Outgrowth of the axillary bud in rose is controlled by sugar metabolism and signalling. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(8):3044–3060. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Nicolas M, Zhang J, Yu H, Guo D, Yuan R, Qin G. The TIE1 transcriptional repressor controls shoot branching by directly repressing BRANCHED1 in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(3):e1007296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie YM, Han FX, Ma JJ, Chen X, Song YT, Niu SH, Wu HX. Genome-wide TCP transcription factors analysis provides insight into their new functions in seasonal and diurnal growth rhythm in Pinus tabuliformis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller D, Waldie T, Miyawaki K, To JP, Melnyk CW, Kieber JJ, Leyser O. Cytokinin is required for escape but not release from auxin mediated apical dominance. Plant J. 2015;82(5):874–886. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao X, Ma H, Wang J, Zhang D. Genome-wide comparative analysis and expression pattern of TCP gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. J Integr Plant Biol. 2007;49(6):885–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parapunova V, Busscher M, Busscher-Lange J, Lammers M, Karlova R, Bovy AG, de Maagd RA. Identification, cloning and characterization of the tomato TCP transcription factor family. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen L, Chen YQ, Ding AM, Chen H, Xia F, Wang WF, Sun YH. Genome-wide analysis of TCP family in tobacco. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(7728):10–4238. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15027728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei W, Hu Y, Cui MY, Han YT, Gao K, Feng JY. Identification and transcript analysis of the TCP transcription factors in the diploid woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca. Front Plant Sci. 1937;2016:7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niwa M, Daimon Y, Kurotani K, Higo A, Pruneda-Paz JL, Breton G, Mitsuda N, Kay SA, Ohme-Takagi M, Endo M, et al. BRANCHED1 interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS T to repress the floral transition of the axillary meristems in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:1228–1242. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.109090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosugi S, Ohashi Y. PCF1 and PCF2 specifically bind to cis elements in the rice proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1607–1619. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright WE, Dackorytko I, Farmer K. Monoclonal antimyogenin antibodies define epitopes outside the bHLH domain where binding interferes with protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions. Genesis. 2015;19:131–138. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)19:2<131::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pestana-Calsa MC, Pacheco CM, Castro RCD, Almeida RRD, Lira NPVD, Calsa JT. Cell wall, lignin and fatty acid-related transcriptome in soybean: Achieving gene expression patterns for bioenergy legume. Genet Mol Biol. 2012;35:322–330. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572012000200013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Zhou L, Yung WS, Su W, Huang M. Ectopic expression of Torenia fournieri TCP8 and TCP13 alters the leaf and petal phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Plant. 2021;173(3):856–866. doi: 10.1111/ppl.13479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kieffer M, Master V, Waites R, Davies B. TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011;68(1):147–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Kohlen W, Rossmann S, Vernoux T, Theres K. Auxin depletion from the leaf axil conditions competence for axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Cell. 2014;26(5):2068–2079. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada K, Ueda J, Komaki MK, Bell CJ, Shimura Y. Requirement of the auxin polar transport system in early stages of Arabidopsis floral bud formation. Plant Cell. 1991;3(7):677–684. doi: 10.2307/3869249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McSteen P, Hake S. barren inflorescence 2 regulates axillary meristem development in the maize inflorescence. 2001. pp. 2881–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McSteen P, Malcomber S, Skirpan A, Lunde C, Wu X, Kellogg E, Hake S. barren inflorescence 2 encodes a co-ortholog of the PINOID serine/threonine kinase and is required for organogenesis during inflorescence and vegetative development in maize. Plant Physiol. 2007;144(2):1000–1011. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.098558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chabikwa TG, Brewer PB, Beveridge CA. Initial bud outgrowth occurs independent of auxin flow from out of buds. Plant Physiol. 2019;179(1):55–65. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katyayini NU, Rinne PL, Tarkowská D, Strnad M, van der Schoot C. Dual role of gibberellin in perennial shoot branching: inhibition and activation. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:736. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni J, Gao C, Chen MS, Pan BZ, Ye K, Xu ZF. Gibberellin promotes shoot branching in the perennial woody plant Jatropha curcas. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56(8):1655–1666. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeda T, Suwa Y, Suzuki M, Kitano H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M, Ueguchi C. The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. Plant J. 2003;33(3):513–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong L, Ishak A, Yu J, Zhao R, Zhao L. Identification and functional analysis of three MAX2 orthologs in chrysanthemum. J Integr Plant Biol. 2013;55(5):434–442. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Wang Y, Zhou P. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during Chinese wolfberry fruit development. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;70:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2: Table S1. Physicochemical properties of TCP members in Sunflower.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Primer sequences.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online. “The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, GSE221055 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE221055.