ABSTRACT

The establishment of the Orsay virus-Caenorhabditis elegans infection model has enabled the identification of host factors essential for virus infection. Argonautes are RNA interacting proteins evolutionary conserved in the three domains of life that are key components of small RNA pathways. C. elegans encodes 27 argonautes or argonaute-like proteins. Here, we determined that mutation of the argonaute-like gene 1, alg-1, results in a greater than 10,000-fold reduction in Orsay viral RNA levels, which could be rescued by ectopic expression of alg-1. Mutation in ain-1, a known interactor of ALG-1 and component of the RNA-induced silencing complex, also resulted in a significant reduction in Orsay virus levels. Viral RNA replication from an endogenous transgene replicon system was impaired by the lack of ALG-1, suggesting that ALG-1 plays a role during the replication stage of the virus life cycle. Orsay virus RNA levels were unaffected by mutations in the ALG-1 RNase H-like motif that ablate the slicer activity of ALG-1. These findings demonstrate a novel function of ALG-1 in promoting Orsay virus replication in C. elegans.

IMPORTANCE All viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that recruit the cellular machinery of the host they infect to support their own proliferation. We used Caenorhabditis elegans and its only known infecting virus, Orsay virus, to identify host proteins relevant for virus infection. We determined that ALG-1, a protein previously known to be important in influencing worm life span and the expression levels of thousands of genes, is required for Orsay virus infection of C. elegans. This is a new function attributed to ALG-1 that was not recognized before. In humans, it has been shown that AGO2, a close relative protein to ALG-1, is essential for hepatitis C virus replication. This demonstrates that through evolution from worms to humans, some proteins have maintained similar functions, and consequently, this suggests that studying virus infection in a simple worm model has the potential to provide novel insights into strategies used by viruses to proliferate.

KEYWORDS: Aargonaute, Caenorhabditis elegans, Orsay virus, RISC, alg-1, alg-2

INTRODUCTION

Identifying host factors that are essential for the viral life cycle is critical to our understanding of virus infection and has the potential to yield new therapeutic targets. The metazoan model C. elegans is known to be naturally infected by Orsay virus (1), a positive-sense, nonenveloped RNA virus. Studies of Orsay virus infection have allowed us to better understand virus-host interaction mechanisms (2, 3). We previously established an unbiased forward genetic screen that relies upon a virus inducible transcriptional green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter to identify genes critical for Orsay virus infection (4). Using this strategy, we have previously identified sid-3, viro-2, drl-1, and hipr-1 genes as host factors essential at an early stage of the Orsay virus life cycle (2–5). Importantly, the proviral functions of some of these genes are evolutionarily conserved across species from nematodes to mammals (2).

Argonautes and argonaute-like proteins are evolutionary conserved RNA binding proteins found across the three domains of life. The protein structure of argonautes consist of a N-terminal, PAZ, MID, and PIWI sequence domains, whose ability to bind RNA rely mostly on their PAZ and PIWI domains (6). They are critical components of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) where they mediate control of host gene expression by facilitating the interaction between small RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), or PIWI-associated RNAs (piRNAs), and an RNA target, usually an mRNA (7). Argonautes are also important in antiviral defense against RNA viruses (8–10). In RNA interference (RNAi), the RISC mediates gene expression inhibition by degradation of target mRNAs (11). In the first step of RNAi, Dicer processes double-stranded RNA into small interfering RNAs which in turn promote the degradation of homologous single-stranded mRNAs; argonautes are critical for this process which is dependent on an RNase H-like motif, commonly referred to as the “slicer” motif, localized in the PIWI domain (12, 13). Argonautes play important roles in multiple steps of miRNA-mediated RNA silencing, including binding of the small RNA, recognition, pairing of the target RNA to the small RNA and, in argonautes having slicer activity, cleavage of the target RNA (13).

The C. elegans genome encodes 27 argonautes and argonaute-like genes (14). The argonaute-like gene 1, alg-1, is a key component of the RISC complex that plays an important role in miRNA maturation, life span, and stress response (15). The alg-1 gene encodes two (a and b) isoforms of 1,002 and 1,023 amino acids, respectively (16). ALG-1 is expressed in most somatic cells, including pharyngeal, body muscle, and intestine cells, and it is involved in life span extension (15). Transcriptomic analysis has determined that alg-1 regulates thousands of genes (15, 17) with differential tissue specific patterns in intestine, neuron, and muscle (18, 19). ALG-1 interacts with other proteins found in the RISC, including DCR-1, ALG-1 interacting protein 1 (AIN-1), ALG-1 interacting protein 2 (AIN-2), PYR-1, and ERI-1 (20–22). The interaction between ALG-1 with AIN-1 and AIN-2 is mediated by GW repeats located in a region named the argonaute binding domain (20). A paralogous gene, alg-2, encodes a protein that shares 88% amino acid identity to ALG-1 as measured by BLASTp (23). Enzymatically, ALG-1 possesses slicer activity via an RNase H-like motif with a highly conserved DDH triad that can cleave RNAs (13). ALG-2 is partially redundant with ALG-1, but it is found in distinct complexes (23) and has opposite impact on longevity (15, 24). In one model, ALG-2 loads pre-miRNAs for Dicer cleavage while ALG-1 is necessary for the subsequent step of loading the mature miRNA to the target mRNA (23).

C. elegans ALG-1 homologs exist in other invertebrates and mammals. In humans, there are four ALG-1 orthologs: AGO1, AGO2, AGO3, and AGO4; similarly, Drosophila melanogaster has two orthologs, Ago-1 and Ago-2 (13). Both proviral and antiviral functions of argonautes have been described in multiple host species. Prior studies of Orsay virus in C. elegans defined the antiviral function of the argonaute proteins rde-1 (1), sago-2 (25), and a multiple AGO (MAGO) mutant lacking six argonautes: ppw-1, sago-1, sago-2, F58G1.1, C06A1.4, and M03D4.6 (14, 25). No argonautes in C. elegans that are proviral have been identified to date. In humans, antiviral roles of AGO2 and AGO4 against influenza virus have been reported (8, 9). In contrast, human hepatitis C virus (HCV) relies upon a proviral AGO2-miR-122 complex to stabilize HCV RNA; cells with reduced expression of AGO2 displayed low virus titers (26, 27). The interaction between AGO2:miR-122 has been crystalized and solved at high resolution revealing a stem-loop structure required for HCV protection mediated by AGO2 (28). In D. melanogaster, Argonaute 2 (Ago-2) is essential for antiviral defense as ago-2-defective flies are hypersensitive to infection by Drosophila C virus, and to Cricket Paralysis virus (10). Furthermore, both Dengue virus and West Nile virus genomes encode miRNA-like sequences in the RNA segment 5′ and 3′ UTRs (29, 30). In mosquitoes infected with dengue virus, the virus derived small RNAs autoregulate virus replication in a manner that is dependent on host Ago-2 (29). There are also many argonautes in plants, most of which have described antiviral functions (31); proviral functions of AGO1 and AGO10 in Nicotiana benthamiana in the context of potyvirus (32) and bamboo mosaic virus (33) infection have been reported.

Here, we found C. elegans alg-1 to be a critical proviral host factor essential for Orsay virus infection. ALG-1 is known to bind AIN-1 in the RISC complex, and Orsay virus levels were reduced similarly in ain-1 mutants to alg-1 mutants demonstrating that AIN-1 is also essential for Orsay virus infection. We further demonstrated that alg-1 is necessary at the replication stage of the Orsay virus life cycle. ALG-1 proviral activity was found to be independent of its slicer RNase H-like motif. Together, these results establish a proviral function of a C. elegans argonaute, demonstrating that such functions are evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to humans.

RESULTS

Forward genetic screen for mutants displaying low Orsay virus replication phenotypes.

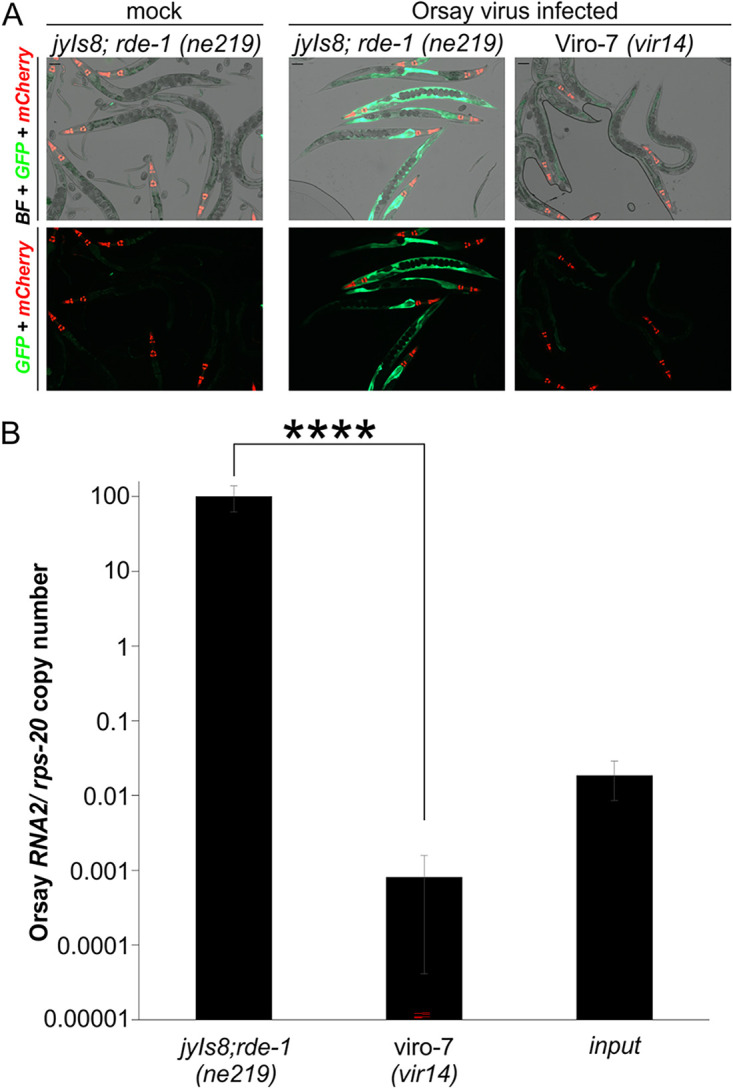

We previously established an unbiased forward genetic screen to identify genes critical for Orsay virus infection that relies upon the jyIs8; rde-1 (ne219) reporter strain, WUM31, expressing GFP under the control of the virus inducible gene promoter pals-5 (4). To discover new host factors that Orsay virus relies upon for infection, an ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) chemical mutagenesis screen was performed on ~2,000 haploid genomes in the jyIs8;rde-1(ne219) worms as previously described (3). One Viro (virus-induced reporter off) mutant strain, Viro-7, was found to display a defect in GFP expression upon Orsay virus challenge at 3 days postinfection (dpi) (Fig. 1A). Orsay RNA replication measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) at 3 dpi revealed a reduction of greater than 10,000-fold in Orsay RNA2 levels compared with the unmutagenized parental strain (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Identification of a mutant strain that fails to induce GFP expression and has low Orsay viral RNA levels. (A) GFP reporter expression of the Viro-7 mutant infected with Orsay virus at 3 dpi. Pmyo-2::mCherry is a transgenic marker (scale bar, 100 μm). BF, bright field. (B) Orsay virus RNA2 levels quantified by real-time qRT-PCR at 3 dpi. The averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Mann-Whitney-test. ****, P < 0.0001.

Identification of alg-1 as a gene critical for Orsay virus infection.

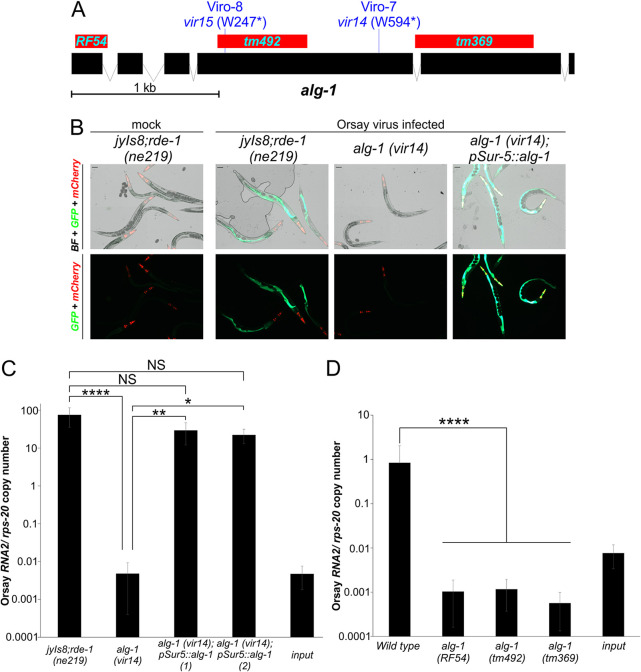

To map the phenotype-causing mutation present in Viro-7, we used F2 bulk segregant analysis as previously described for C. elegans (4, 34) (Materials and Methods). The linked region on chromosome X contained one gene, alg-1, with a premature stop codon (W594*) that was the strongest candidate gene (Fig. 2A). To determine whether the premature stop in alg-1 in the Viro-7 mutant was responsible for the observed phenotypes, we generated a transgenic animal expressing wild-type alg-1 from a fosmid encompassing the alg-1 locus, as well as one with a plasmid driving alg-1 expression by the ubiquitous sur-5 gene promoter. Viro-7 transgenic animals carrying as extrachromosomal arrays either the fosmid (Fig. S1A and 1B) or the pSur-5::alg-1 plasmid (Fig. 2B and C) rescued levels of both GFP expression and Orsay RNA2 levels comparable to the unmutagenized strain. For rescue experiments where the alg-1 gene alone was used, the region cloned encoded the ALG-1 isoform A, as it is known to be sufficient to rescue most of the previously described alg-1 mutant phenotypes such as reduced worm size and brood size (19).These results demonstrated that alg-1 is the gene responsible for the Viro-7 phenotype; this mutant will be referred to hereafter as the alg-1(vir14) mutant strain.

FIG 2.

The alg-1 gene is responsible for the observed defective Orsay virus infection phenotypes in Viro-7. (A) Location and nature of alg-1 alleles in Viro-7, Viro-8, and three mutant strains obtained from CGC. (B) GFP phenotypes following Orsay virus infection of transgenic animals expressing a plasmid containing the alg-1 gene. (C) Orsay virus RNA2 levels quantified by real-time qRT-PCR at 3 dpi in a transgenic animal expressing a plasmid containing the alg-1 gene. Two independent extrachromosomal arrays were tested. Averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Kruskall-Wallis test with a statistical difference identified between two post hoc comparisons analyzed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. (D) Three independent mutant alleles affected on alg-1, RF54, tm369, tm492, were tested for Orsay infection levels at 3 dpi. Averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Mann-Whitney-test, ****, P < 0.0001.

As additional validation, we performed an independent EMS screen utilizing a C. elegans strain (WUM29) that initiates Orsay virus replication from integrated Orsay RNA1 and RNA2 transgenes (4) following heat shock. Because the Orsay virus life cycle is initiated from integrated transgenes, this system bypasses virus entry to directly find genes related to Orsay virus replication. From this screen, we isolated a mutant, Viro-8, that displayed consistently low GFP signal and Orsay virus RNA levels upon heat shock (Fig. S2A) as well as following exogenous Orsay virus infection (Fig. S2B and C). Whole-genome sequencing of Viro-8 identified an alg-1 W247* nonsense mutation (Fig. 2A). Ectopic expression of the pSur-5::alg-1 plasmid in Viro-8 rescued the GFP and Orsay virus RNA2 level defects, providing further unambiguous evidence that mutation of alg-1 was responsible for the mutant phenotype. Hereafter, this mutant is referred to as alg-1 (vir15).

Furthermore, we tested three independent deletion mutant alleles of alg-1, RF54, tm492, and tm369 (15, 19, 35–37) (Fig. 2D) that are available from the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center. After challenge with Orsay virus, all three mutants displayed consistently low levels of Orsay replication compared to wild-type, confirming the critical role alg-1 plays in Orsay virus infection (Fig. 2D). In total, we evaluated five independent alleles of alg-1, and all of them demonstrated a consistent low Orsay virus level phenotype. Western blot confirmed that alg-1 (vir-14), alg-1 (RF54), alg-1 (tm369), and alg-1 (tm492) had undetectable levels of ALG-1 (Fig. S3).

Mutants of ain-1 displayed reduced Orsay virus levels in C. elegans.

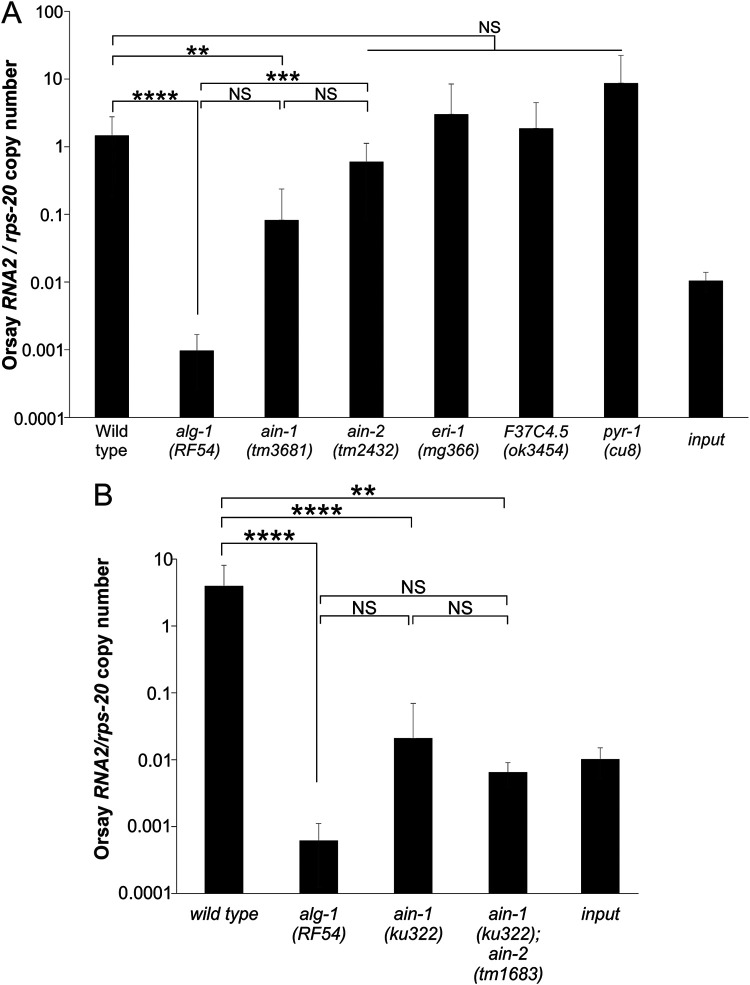

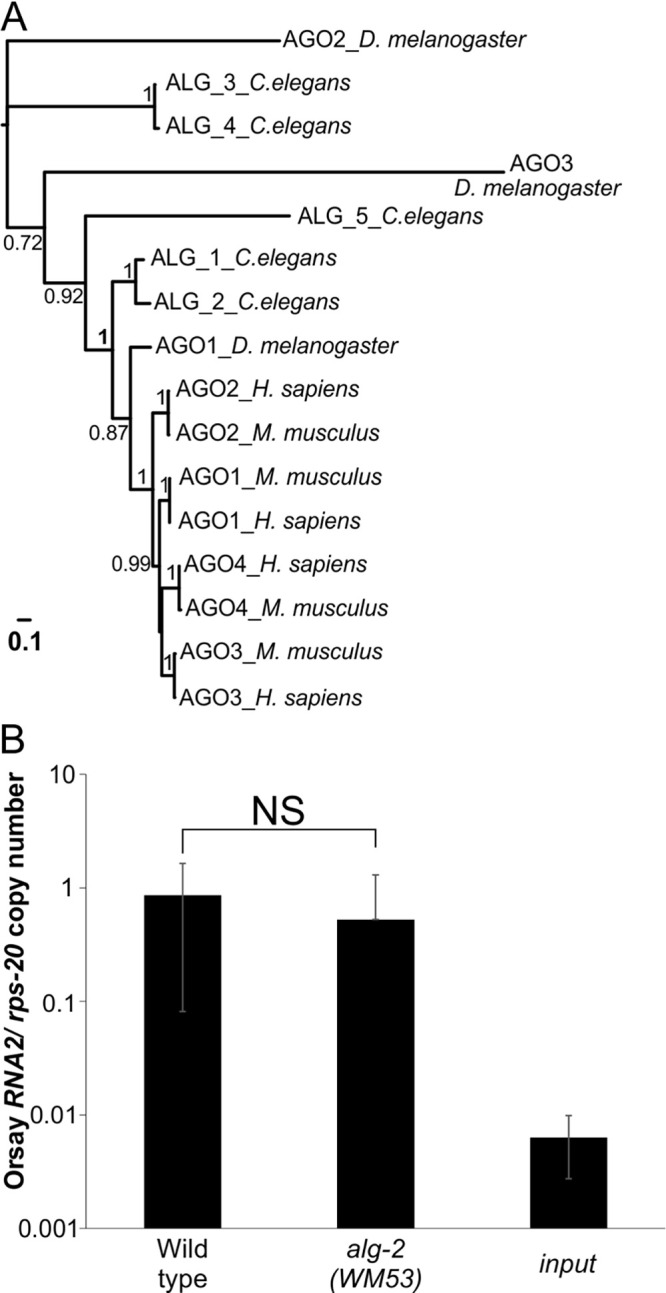

ALG-1 has some redundant functions with and shares 88% amino acid identity to ALG-2, its closest paralog (Fig. 3A, S4) (23). Deletion of alg-2 (Fig. 3B) had no impact on Orsay virus RNA levels, demonstrating that the proviral function is a specific property of ALG-1. ALG-1 physically interacts with multiple proteins, including AIN-1 (21), AIN-2 (20, 21), ERI-1 (22), F37C4.5 (22), and PYR-1 (22). We tested gene deletion mutants in these five genes (Fig. 4A); only the ain-1 (tm3681) deletion mutant displayed a statistically significant reduction in Orsay RNA2 levels compared to the wild-type. We further analyzed a second mutant allele in ain-1 (ku322) as well as an ain-1 (ku322); ain-2 (tm1863) double mutant (38). The ain-1 (ku322) mutant had viral RNA levels that were statistically undistinguishable from alg-1 (RF54) (Fig. 4B). The Orsay virus RNA levels in ain-1; ain-2 double mutant infected animals were not statistically different from the single mutant ain-1 (ku322) or alg-1 (RF54) (Fig. 4B). Thus, the alg-1 phenotype is recapitulated by ain-1(ku322) alone. ALG-1 levels were not altered by mutation of ain-1 or ain-2 (Fig. S3). AIN-1 interacts with ALG-1 as part of the miRNA binding RISC (38), suggesting that the miRNA binding RISC is important for Orsay virus infection.

FIG 3.

The closely related C. elegans alg-1 gene paralog, alg-2 gene, has wild-type levels of Orsay virus infection. (A) Maximum-likelihood based phylogenetic analysis of ALG-1 homologs. Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like P-values for bipartitions are indicated. The scale bar indicates the expected numbers of amino acid substitutions per site under the LG model. (B) Orsay virus RNA2 levels quantified by real-time qRT-PCR at 3 dpi, in the alg-2 mutant allele (WM53) and compared to the wild-type. The averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Mann-Whitney-test. NS, not significant.

FIG 4.

AIN-1 is important for Orsay virus infection of C. elegans. (A) Five mutants were tested for Orsay infection levels at 3 dpi. The averages and standard deviation for three replicates are representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. (B) The ain-1 (ku322) and ain-1 (ku322); ain-2 (tm1863) double mutants were tested for Orsay infection levels at 3 dpi. Statistically significant differences were determined by Kruskall-Wallis test with a statistical difference identified between three post hoc comparisons analyzed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

The alg-1 gene is essential for virus replication.

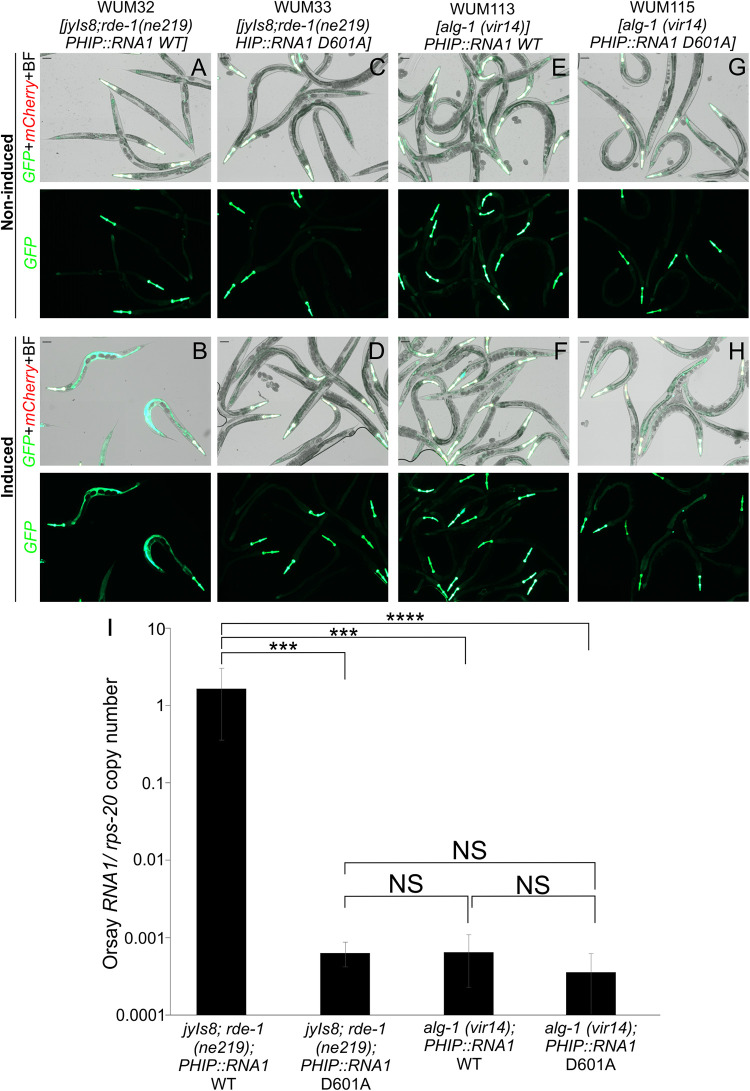

Orsay virus replication is sufficient to activate the pals-5 promoter (4); as such, the mutants that fail to induce GFP after Orsay virus challenge must be defective in one or more early steps of the Orsay virus life cycle up to and including virus replication. We determined whether ALG-1 was affecting a prereplication or a replication stage step of the Orsay virus life cycle by making use of a previously described endogenous inducible viral RNA transgene replicon system (4). In this setting, virus replication is initiated from a plasmid encoding the Orsay virus RNA1 segment (which is competent to replicate). Virus entry is bypassed and impacts of ALG-1 on the replication process can be assessed. A plasmid with the RNA1 segment encoding a D601A Orsay polymerase mutation that is unable to replicate is used as a control for baseline DNA templated RNA1 transcription levels.

We generated an alg-1(vir14) strain expressing the RNA1 wild-type transgene (WUM113) and another strain expressing the RNA1 D601A Orsay polymerase mutant (WUM115) and compared them to the corresponding strains that were wild-type for alg-1 (strains j8;rde-1; RNA1 wild-type [WUM32] and j8;rde-1; RNA1 D601A mutant [WUM33]) (Fig. 5A to 5H). The alg-1 (vir14) strain expressing the RNA1 wild-type transgene (e.g., WUM113) did not activate the GFP signal (Fig. 5F), and its RNA1 level was ~2,000-fold lower than in the WUM32 line and were not significantly different than the strains carrying the D601 mutant polymerase (e.g., WUM115) (Fig. 5I). This result demonstrated that Orsay virus replication initiated from an endogenous transgene is dependent on alg-1. Consistent with this observation, the independent isolation of alg-1 (vir15) from the EMS screen using the endogenous Orsay virus transgenic line, which completely bypasses viral entry, demonstrated that alg-1 is essential for the viral replication step of the Orsay life cycle (Fig. S2). However, this finding does not rule out ALG-1 also having additional relevant functions in pre- or post-replication steps of the virus life cycle.

FIG 5.

The alg-1 gene impacts Orsay virus replication from the RNA1 transgene. (A to H) GFP expression of strains 1 day after either no heat induction or after 2 h heat shock at 33°C. (I) Orsay virus RNA1 levels quantified by qPCR at 1d post heat shock at 33°C. Two independent extrachromosomal arrays were tested for alg-1 (vir14); RNA1 wild-type as well as for alg-1 (vir14); RNA1 D601A. The averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Kruskall-Wallis test with a statistical difference identified between three post hoc comparisons analyzed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

ALG-1 function on Orsay replication is independent of its slicing activity.

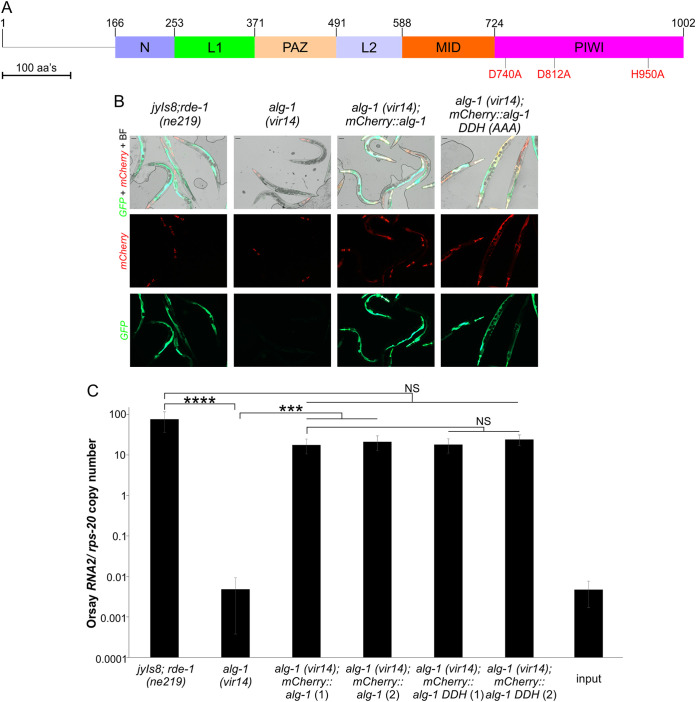

In humans, AGO2 antiviral activity relies on its RNase H-like motif, as mutations in the first residue of the DDH motif (D597A) increase mouse embryonic fibroblasts susceptibility to influenza infection (9). In Drosophila, the Ago2 slicer activity also has been shown to be important for vesicular stomatitis virus infection (39). Biochemically, C. elegans ALG-1 can cleave 32-nt target RNAs into shorter (10 to 15 nt) fragments in vitro in a process dependent on its RNase H-like motif; this is referred to as its slicing activity (40). To determine the contribution of the slicing activity of ALG-1 on Orsay replication, we ectopically expressed from pSur-5 plasmids N-terminal mCherry-tagged WT ALG-1 or an ALG-1 DDH (D740A/D812A/H950A) mutant in which the ALG-1 D740 residue is homologous to the human AGO2 D597 residue (13). Transgenic strains expressing the WT or the DDH mutant both rescued GFP expression and Orsay RNA to equivalent levels (Fig. 6A to C). Thus, the slicing activity of ALG-1 is not needed to promote Orsay virus replication.

FIG 6.

Protein domain organization of C. elegans ALG-1. (A) Schematic depicting ALG-1 protein domains with the three point mutations constituting the RNase H-like (DDH) motif are indicated in red. (B) Mutations were introduced into the Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 expression construct for visual confirmation of protein expression. GFP reporter expression of two independent extrachromosomal arrays for the wild-type Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 construct as well as for clones carrying the DDH mutation were analyzed. Worms were collected and imaged (scale bar, 50 μm). BF, bright field. (C) Orsay virus RNA2 levels quantified by real-time qRT-PCR at 3 dpi and the averages and standard deviation for three replicates representative of at least three independent biological experiments are shown. Statistically significant differences were determined by Kruskall-Wallis test with a statistical difference identified between three post hoc comparisons analyzed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test. ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The established Orsay virus-C. elegans model has facilitated identification of novel proviral and antiviral factors (3–5, 41–43). We previously described a forward genetic screening strategy to identify proviral host factors that identified sid-3 and viro-2 (4), drl-1 (5), and hipr-1 (3). Here, we identified alg-1 as another gene that similarly failed to activate GFP following Orsay infection and resulted in a >4-log reduction in Orsay RNA2 levels relative to the parental strain jyIs8; rde-1 (ne219). In contrast to the previously identified host factors which all appear to act at the stage of viral entry, alg-1 impacts the viral replication stage of the Orsay life cycle.

ALG-1 and ALG-2 are closely related paralogs that share 88% amino acid identity. These two genes exhibit a degree of redundancy as evidenced by the viability of each single mutant while mutation of both genes is lethal (23). ALG-1 and ALG-2 appear to have the same miRNA binding profile, but they occur in distinct protein complexes of different masses (23). They also clearly have distinct functions based on the observation that different sets of genes cause synthetic lethality in an RNAi screen (15, 23). Here, we demonstrate that while alg-1 is essential for Orsay virus replication, alg-2 is completely dispensable for Orsay virus infection, providing additional evidence that ALG-1 has unique functionality not shared with ALG-2.

ALG-1 is known to bind numerous proteins, including AIN-1 and AIN-2 in the context of the miRISC. AIN-1, through its contact with ALG-1, interacts with a wider range of miRNAs than AIN-2, and ain-1 mutants have a more severe defect than ain-2 mutants. Distinct miRISC complexes contain either AIN-1 or AIN-2, but not both (21), and AIN-1 binds to proteins such as PABPC, PAN3, NOT1, and NOT2 that AIN-2 does not (20). From testing of deletion mutants, multiple mutant ain-1 alleles (tm3681 and ku322) had Orsay virus load phenotypes suggesting that the proviral function of ALG-1 is dependent upon AIN-1. The miRISC containing ALG-1 and AIN-1 is responsible for loading miRNAs onto target mRNAs, leading to the established effector functions of either translational inhibition or mRNA degradation (20, 21). There are multiple mechanisms by which C. elegans ALG-1 acting with AIN-1 could affect Orsay virus replication. One hypothesis is that ALG-1 and AIN-1 are needed to load one or more miRNAs that reduce expression of a host protein that negatively impacts Orsay virus replication. Another possibility is that Orsay virus itself might encode a viral miRNA that requires processing by ALG-1 (and AIN-1) as has been observed in Dengue virus in mosquitoes and Ago-2 (29). While not following the classic miRNA paradigm of reducing target RNA expression, in another model, ALG-1 and AIN-1 could bind to a host miRNA that interacts directly with the Orsay genomic RNA to stabilize the genome. This would be analogous to the function of human AGO2 in binding miR-122 and HCV RNA, a process that is critical for HCV replication (28). It could be also possible that ALG-1 act similarly to AGO10 in N. benthamiana which competes for binding to and sequesters virus derived siRNAs (33). Additional experiments to discriminate between these models or other possible mechanisms are needed.

While we have explicitly defined a role for alg-1 in Orsay virus replication, this does not rule out the possibility that alg-1 could also impact other stages of the Orsay virus life cycle. Based on transcriptional profiling, mutation of alg-1 downregulates two known proviral genes that act at early, prereplication stages of the Orsay life cycle, drl-1 and hipr-1, by ~50% and 25%, respectively (3, 5, 15). Reducing levels of these genes would be expected to impair the ability of Orsay virus to infect C. elegans. Because alg-1 modulates levels of thousands of genes (15), it could also affect additional, yet unknown genes essential for nonreplication stages of the virus life cycle.

To begin exploring enzymatic features of ALG-1 that may be required for its proviral function, we tested the impact of ablating its known slicer activity. The rational for this is based on studies in humans and Drosophila that have demonstrated the importance of the slicing activity (9, 39). Our studies demonstrated that the biochemically observed slicing activity that is dependent on the DDH triad (40) is not important in vivo for the ability of ALG-1 to promote Orsay virus replication. This finding is consistent with the observation that expression of a catalytically inactive DDH mutant of alg-1 rescues the developmental defects of alg-1 mutants (40). This implies that the mechanism by which C. elegans ALG-1 acts may be distinct from that of its human and Drosophila orthologs.

Overall, these findings demonstrate a critical proviral role for alg-1 in Orsay virus infection of C. elegans. While alg-1 has previously been linked to numerous phenotypes in C. elegans, our findings establish a novel link between the miRISC components, ALG-1 and AIN-1, and Orsay virus infection. This phenotype parallels proviral properties of its human ortholog, AGO2, which is required for HCV infection, demonstrating that proviral functions in the argonaute gene family are evolutionarily conserved from nematodes to humans. Further studies are still necessary to define the precise mechanism by which ALG-1 promotes Orsay virus infection in C. elegans which in turn may shed further light on argonaute functions in mammalian biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans culture and maintenance.

We obtained C. elegans strains rde-1(ne219) (WM27), alg-1 (RF54), alg-2 (WM53), ain-1 (tm3681), ain-1 (ku322), ain-2 (tm2432), eri-1 (mg366), F37C4.5 (ok3454), and pyr-1 (cu8) from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC). The ain-1 (ku322); ain-2 (tm1863) double mutant (21) was kindly shared by Dr. Han lab. The alg-1 (tm369) and alg-1 (tm492) mutant alleles were provided by the Mitani lab (National Bioresource Project). Animals were routinely fed with Escherichia coli OP50 grown on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates in a 20°C incubator and chunked every 3 to 4 days to a new NGM plate seeded with E. coli OP50. A full list of strains is included in the Table S1.

Orsay virus preparation, infection, and RNA extraction.

Orsay virus was prepared as previously described (2). Large-scale liquid cultures of Orsay infected worms were lysed, filtered through a 0.22-μm filter, and 100 μL aliquots stored at −80°C. For Orsay virus infection experiments involving animals without extrachromosomal arrays, animals were bleached and then synchronized. In six-well plates with 20 μL E. coli OP50, 500 arrested larval stage 1 (L1) larvae were seeded. L1 larvae were allowed to recover for 20 h at 20°C prior to infection. Orsay virus filtrate was used at a 1:10 dilution with M9 buffer. For each well, 20 μL of virus filtrate was added and the infection was incubated at 20°C. Orsay infected animals (3 dpi) were collected by centrifugation in 1.5 mL microtubes, 300 μL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was added, and the worm mix was frozen in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction was performed. For all Orsay virus infection assays, a control to estimate the residual amount of input virus was included. This consisted of E. coli OP50 NGM plates plated with 20 μL 1:10 Orsay virus dilution in the absence of any animals and parallel wells of animals only without any virus. After 3 days, the OP50-Orsay virus plate content was collected using M9 solution and then mixed with the noninfected worms. The solution was centrifuged, and 300 μL TRIzol reagent added to harvest RNA. At least three biological replicates (i.e., experiments performed on different days) were performed for each experiment and each biological experiment was run in triplicate. Total RNA from infected animals was extracted using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep (Zymo Research) purification according to the manufacturer’s protocol and eluted into 30 μL of RNase/DNase-free water.

Orsay virus quantification by real-time qRT-PCR.

RNA extracted from infected animals was subjected to one-step qRT-PCR to quantify Orsay virus replication as previously described (2). The extracted RNA was diluted 1:100, and 5 μL was used in a TaqMan Fast Virus 1-Step qRT-PCR with primers GW303 and GW304 and probe Orsay_RNA2 (Table S2) that target the Orsay RNA2 segment. Primers GW314 and GW315 and probe Orsay_RNA1 that target the Orsay virus RNA1 segment were used to quantify Orsay virus RNA1 abundance. To account for variation in the number of animals per well, Orsay virus RNA levels were normalized to an internal control host gene, rps-20, which encodes a small ribosomal subunit S20 protein required for translation in C. elegans, using primers KC291 and KC292 and probe rps-20_e3-4. Absolute Orsay virus RNA2 and RNA1 and C. elegans rps-20 copy number was determined by interpolation of a standard curve generated using serial dilutions of in vitro transcripts of Orsay virus RNA2 and RNA1 and C. elegans rps-20, respectively. All raw data generated from Orsay virus infections are included in Table S3.

Forward genetic screen for mutants that fail to activate GFP expression following exogenous Orsay virus infection.

The jyIs8;rde-1 (ne219) reporter strain was maintained on 10-cm plates seeded with 1 mL E. coli OP50. Animals were grown to a stage with a high proportion of L4 larvae and were then collected by rinsing the plates with water. Animals were then treated with 50 mM EMS for 4h at 20°C with constant rotation, washed with M9 buffer, and recovered on 10-cm plates for 6 h. Ten L4 P0 animals were transferred to 10 new NGM plates and allowed to lay about 10 F1 eggs each before being removed. F1 animals were washed away from plates after laying about 20 eggs for each animal. Hatched F2 animals were challenged with 800 μL of the standard virus filtrate dilution for infection and screened for Viro (for virus-induced GFP reporter off) mutants. Candidate animals were propagated and subjected to two additional rounds of virus challenge to confirm the Viro phenotype.

Forward genetic screen for mutants that fail to activate GFP expression following induction of transgenic Orsay virus.

The virIs1; jyIs8; rde-1 reporter strain was staged and treated with EMS as described above. F2 worms at the L4 stage were subjected to heat shock to initiate Orsay virus replication from the endogenous transgenes and incubated for 2 h at 33°C followed by an incubation for 48h at 23°C. Animals were validated for Viro phenotypes as above.

Genetic mapping through F2 bulk segregant and CloudMap analysis.

The alg-1 (vir14) mutant animals were crossed with the rde-1(ne219) (WM27) strain, and F1 progenies were chosen and transferred to six-well plates. After 3 days, the F2 progenies were challenged with Orsay virus. A total of 187 F2 Viro animals were picked off from the infected F1 plates and individually transferred to six-well plates. F2 plates were moved to a new plate after 1 day of laying eggs to generate two replicate F3 wells per F2 worm. The first set of F3 worm plates were challenged again with Orsay virus, and both virus induced GFP fluorescence and Orsay virus RNA levels were assayed at 3 dpi to identify animals that fail to express GFP and that had low Orsay RNA levels. The corresponding wells from the replicate set of F3 worms were all pooled, and genomic DNA from a single pooled sample was extracted using a Qiagen genomic DNA preparation kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA libraries were prepared using a Nextera library preparation kit (New England Biolabs) and then sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq standard. The raw sequence data were analyzed using the pipeline CloudMap for C. elegans gene mapping (34).

Detection of ALG-1 protein in C. elegans mutants by Western blot.

From a 10-cm NGM plate of animals grown to near starvation, animals were harvested by centrifugation. The C. elegans pellet was homogenized by using silicon beads (1.0 mm diameter zirconia) in a tissue homogenizer (TissueLyser II, Qiagen) for two rounds of 30 hz for 1 min with a cooling step of 2 min on ice. Protein was quantified by the BCA protein assay. Western blot analysis of ALG-1 was performed by loading 15 μg of each worm extract. Each sample was mixed with 6 × SDS sample buffer and then boiled for 5 min. Proteins were resolved on a 4% to 20% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The PVDF membrane was then blocked with 5% skim milk in PBST (PBS with 0.3% Tween 20) for 1 h shaking at room temperature. The membrane was blotted with anti-ALG-1 polyclonal antibody (PA1-031) at a dilution of 1:5,000 for 1 h at room temperature. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used at a dilution of 1:10,000. Protein bands were developed by using a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

alg-1-containing plasmids for ectopic expression and rescue of the alg-1 mutant strains.

For rescue of alg-1 (vir14), a fosmid (WRM0640cB03) containing the alg-1 gene was injected into the mutant strain at a concentration of 50 ng/μL, along with 5 ng/μL of Pmyo-2::YFP as a transgenic marker and 200 ng/μL of DNA ladder (New England Biolabs [NEB], N3200S) to help establish the array (44). To construct the alg-1 expression plasmid (Psur-5::alg-1), the entire alg-1 gene was amplified from N2 genomic DNA using primers JZ30 and JZ31 (Table S2). The PCR product was digested by NotI and BmtI and subsequently ligated into the plasmid containing the sur-5 promoter as previously described (2). The Psur-5::alg-1 plasmid was injected into alg-1 (vir14) animals at a concentration of 50 ng/μL, along with 5 ng/μL of Pmyo-2::YFP as a transgenic marker and 50 ng/μL of DNA ladder (NEB, N3200S). At least two transgenic lines expressing the Psur-5::alg-1 were generated and assayed under Orsay virus infection as indicated below.

To construct the N-terminal tagged mCherry::alg-1 expression plasmid (Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1), the mCherry gene lacking its stop codon was amplified from a previously published C-terminally tagged Psur-5::hipr-1::mCherry L438A clone (3) using primers CC19 and CC20 (Table S2). The PCR product was digested by SacII and NotI and then ligated into a plasmid containing the sur-5 promoter and the mCherry gene with an 18-bp linker, amino acid sequence RPPNDP, at the 3′ end of the mCherry gene. The Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 plasmid was injected into alg-1 (vir14) animals at a concentration of 50 ng/μL, along with 5 ng/μL of Pmyo-2::YFP as a transgenic marker and 50 ng/μL of DNA ladder (NEB, N3200S). At least two transgenic lines expressing the Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 were generated and assayed under Orsay virus infection as follows: five worms stably expressing the transgenic array of each line or strain were seeded into three wells of a six-well plate. After 24 h of egg laying, 1:10 Orsay virus dilution was added to the plates as described above. At 72 h postinfection young to1-day-old adult Orsay-infected animals (animals reaching adulthood within 24 h after L4 stage) carrying the myo-2::YFP maker in the head were imaged for GFP fluorescence and the Orsay infected mixed populations of transgenic/non transgenic animals were collected for RNA extraction and assayed for virus replication by qRT-PCR. For the jyIs8; rde-1 (ne219) and alg-1 (vir14) controls young to 1-day-old adult animals were randomly collected for GFP imaging, and populations collected for RNA extraction. For rescue of the alg-1 (vir15) mutant, the Psur-5::alg-1 plasmid containing the alg-1 gene was injected into the mutant strain at a concentration of 50 ng/μL, along with 5 ng/μL of Pmyo-3::mCherry as a transgenic marker and 50 ng/μL of DNA ladder (NEB, N3200S) to help establish the array. Estimated frequencies of transgene segregation among the different ALG-1-expressing transgenic lines ranged from 25% to 30%. Transgene carrying alg-1 animals in general appeared to restore growth rate and size to that of WT animals.

Phylogenetic analysis of ALG-1 homologs.

Multiple closely related C. elegans ALG-1 homologs from metazoan animal models (Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, and Mus musculus) identified by using BLASTp were collected and aligned by using MUSCLE (45, and the resulting alignment used for phylogenetic analysis. To improve phylogeny estimation, we used 100 random seed trees in addition to a BioNJ tree to start 101 searches. Tree searching under the maximum-likelihood criterion was performed with PhyML v3.0 (46). The bipartition support was evaluated by the Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like approximate LRT test (47) while the selected model of amino acid substitution was LG (48). Data sequence for the multiple alignment used for phylogenetic analysis is found in Fig. S4.

Generation of alg-1 (vir14) lines expressing Orsay RNA1 wild-type and RNA1 D601A mutant segments.

We crossed the C. elegans RNA1 wild-type (WUM32) and D601A (WUM33) mutant lines into the alg-1 (vir14) genetic background. For genotyping of alg-1 (vir14)-derived RNA1 lines, we took advantage of the gain of a hyp188I restriction site in the alg-1 (vir14) mutant DNA sequence compared to the wild-type that could be assayed by using primers CC89 and CC90.

For the heat shock experiment, five young adult worms stably expressing the transgenic RNA1 array were allowed to lay eggs for 3 days at 20°C, then the progenies were heat-shocked at 33°C for 2 h, then moved back to growth at 20°C for 1 day. At 24 h after heat shock, animals were assayed for GFP fluorescence and collected for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR to measure the RNA1 segment using primers GW314 and GW315 as well as the Orsay_RNA1 probe as indicated.

Site-directed mutagenesis on relevant functional ALG-1 domains and ectopic expression in the alg-1 (vir14) strain.

The Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 plasmid was used for site-directed mutagenesis. Primers for site directed mutations were generated by Agilent QuikChange Primer Design. Site-directed mutagenesis primers CC53 to CC74 were used to introduce the desired amino acid substitutions into the Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 plasmid as follows: To mutate the DDH motif (40), primers CC57, CC58 (D740A); CC63, CC64 (D812A), and CC71, CC72 (H950A). Primers can be found in Table S2.

The Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 plasmid mutants were injected into alg-1 (vir14) animals at a concentration of 50 ng/μL, along with 5 ng/μL of Pmyo-2::YFP as a transgenic marker and 50 ng/μL of DNA ladder (NEB, N3200S). At least two transgenic lines expressing each of the Psur-5::mCherry::alg-1 mutant variant plasmids were generated and assayed under Orsay virus infection as previously indicated.

Fluorescence microscopy.

C. elegans young to 1-day-old adult animals were anesthetized with 40 mM tetramisole and placed onto a 1% dry agarose pad with a coverslip on top. Sample images were acquired with a Zeiss Axio Imager D1 inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) equipped with an X-Cite120 mini LED light source (Excelitis Technologies, Waltham, MA), GFP (ex 450 to 490 nm, em 500 to 550 nm) and Cy3 (ex 537 to 563, em 570 to 640 nm) filter sets for capturing brightfield, GFP and mCherry fluorescent markers, respectively. An EC Plan-Neofluar (NA 0.3) 10× objective (Zeiss), an Axiocam 503 color camera (Zeiss), and ZEN 2 (blue version) software were also used for image acquisition and analysis. For all images, the exposure times were 20 ms for brightfield, 300 ms for GFP, and 150 ms for mCherry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Nonet for sharing the WRM0640cB03 fosmid. We also want to thank Min Han for sharing the ain-1 and ain-1;ain-2 double mutant strains. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440) and the National Bioresource Project (Mitani lab). This project was supported in part by NIH AI134967 (to D.W.) and American Heart Association Grant 18TPA34230015. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

David Wang, Email: davewang@wustl.edu.

Rebecca Ellis Dutch, University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Felix MA, Ashe A, Piffaretti J, Wu G, Nuez I, Belicard T, Jiang Y, Zhao G, Franz CJ, Goldstein LD, Sanroman M, Miska EA, Wang D. 2011. Natural and experimental infection of Caenorhabditis nematodes by novel viruses related to nodaviruses. PLoS Biol 9:e1000586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang H, Leung C, Tahan S, Wang D. 2019. Entry by multiple picornaviruses is dependent on a pathway that includes TNK2, WASL, and NCK1. Elife 8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.50276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang H, Sandoval Del Prado LE, Leung C, Wang D. 2020. Huntingtin-interacting protein family members have a conserved pro-viral function from Caenorhabditis elegans to humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:22462–22472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006914117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang H, Chen K, Sandoval LE, Leung C, Wang D. 2017. An evolutionarily conserved pathway essential for Orsay virus infection of Caenorhabditis elegans. mBio 8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00940-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandoval LE, Jiang H, Wang D. 2019. The dietary restriction-like gene drl-1, which encodes a putative serine/threonine kinase, is essential for Orsay Virus infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Virol 93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01400-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutvagner G, Simard MJ. 2008. Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schirle NT, MacRae IJ. 2012. The crystal structure of human Argonaute2. Science 336:1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1221551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adiliaghdam F, Basavappa M, Saunders TL, Harjanto D, Prior JT, Cronkite DA, Papavasiliou N, Jeffrey KL. 2020. A requirement for Argonaute 4 in mammalian antiviral defense. Cell Rep 30:1690–1701 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Basavappa M, Lu J, Dong S, Cronkite DA, Prior JT, Reinecker HC, Hertzog P, Han Y, Li WX, Cheloufi S, Karginov FV, Ding SW, Jeffrey KL. 2016. Induction and suppression of antiviral RNA interference by influenza A virus in mammalian cells. Nat Microbiol 2:16250. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rij RP, Saleh MC, Berry B, Foo C, Houk A, Antoniewski C, Andino R. 2006. The RNA silencing endonuclease Argonaute 2 mediates specific antiviral immunity in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev 20:2985–2995. doi: 10.1101/gad.1482006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratt AJ, MacRae IJ. 2009. The RNA-induced silencing complex: a versatile gene-silencing machine. J Biol Chem 284:17897–17901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900012200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner FA, Okihara KL, Hoogstrate SW, Sijen T, Ketting RF. 2009. RDE-1 slicer activity is required only for passenger-strand cleavage during RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L. 2007. Slicer and the argonautes. Nat Chem Biol 3:36–43. doi: 10.1038/nchembio848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yigit E, Batista PJ, Bei Y, Pang KM, Chen CC, Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L, Mitani S, Simard MJ, Mello CC. 2006. Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell 127:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aalto AP, Nicastro IA, Broughton JP, Chipman LB, Schreiner WP, Chen JS, Pasquinelli AE. 2018. Opposing roles of microRNA Argonautes during Caenorhabditis elegans aging. PLoS Genet 14:e1007379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zinovyeva AY, Bouasker S, Simard MJ, Hammell CM, Ambros V. 2014. Mutations in conserved residues of the C. elegans microRNA Argonaute ALG-1 identify separable functions in ALG-1 miRISC loading and target repression. PLoS Genet 10:e1004286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown KC, Svendsen JM, Tucci RM, Montgomery BE, Montgomery TA. 2017. ALG-5 is a miRNA-associated Argonaute required for proper developmental timing in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Nucleic Acids Res 45:9093–9107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brosnan CA, Palmer AJ, Zuryn S. 2021. Cell-type-specific profiling of loaded miRNAs from Caenorhabditis elegans reveals spatial and temporal flexibility in Argonaute loading. Nat Commun 12:2194. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22503-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotagama K, Schorr AL, Steber HS, Mangone M. 2019. ALG-1 influences accurate mRNA splicing patterns in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine and body muscle tissues by modulating splicing factor activities. Genetics 212:931–951. doi: 10.1534/genetics.119.302223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzuoglu-Ozturk D, Huntzinger E, Schmidt S, Izaurralde E. 2012. The Caenorhabditis elegans GW182 protein AIN-1 interacts with PAB-1 and subunits of the PAN2-PAN3 and CCR4-NOT deadenylase complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 40:5651–5665. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Ding L, Cheung TH, Dong MQ, Chen J, Sewell AK, Liu X, Yates JR, 3rd, Han M. 2007. Systematic identification of C. elegans miRISC proteins, miRNAs, and mRNA targets by their interactions with GW182 proteins AIN-1 and AIN-2. Mol Cell 28:598–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan SP, Slack FJ. 2009. Ribosomal protein RPS-14 modulates let-7 microRNA function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 334:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF. 2006. The Caenorhabditis elegans Argonautes ALG-1 and ALG-2: almost identical yet different. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 71:189–194. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasquez-Rifo A, Jannot G, Armisen J, Labouesse M, Bukhari SI, Rondeau EL, Miska EA, Simard MJ. 2012. Developmental characterization of the microRNA-specific C. elegans Argonautes alg-1 and alg-2. PLoS One 7:e33750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashe A, Belicard T, Le Pen J, Sarkies P, Frezal L, Lehrbach NJ, Felix MA, Miska EA. 2013. A deletion polymorphism in the Caenorhabditis elegans RIG-I homolog disables viral RNA dicing and antiviral immunity. Elife 2:e00994. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimakami T, Yamane D, Jangra RK, Kempf BJ, Spaniel C, Barton DJ, Lemon SM. 2012. Stabilization of hepatitis C virus RNA by an Ago2-miR-122 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:941–946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112263109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Randall G, Panis M, Cooper JD, Tellinghuisen TL, Sukhodolets KE, Pfeffer S, Landthaler M, Landgraf P, Kan S, Lindenbach BD, Chien M, Weir DB, Russo JJ, Ju J, Brownstein MJ, Sheridan R, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, Rice CM. 2007. Cellular cofactors affecting hepatitis C virus infection and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:12884–12889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704894104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebert LFR, Law M, MacRae IJ. 2021. A structured RNA motif locks Argonaute2:miR-122 onto the 5' end of the HCV genome. Nat Commun 12:6836. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussain M, Asgari S. 2014. MicroRNA-like viral small RNA from Dengue virus 2 autoregulates its replication in mosquito cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:2746–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320123111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hussain M, Torres S, Schnettler E, Funk A, Grundhoff A, Pijlman GP, Khromykh AA, Asgari S. 2012. West Nile virus encodes a microRNA-like small RNA in the 3' untranslated region which up-regulates GATA4 mRNA and facilitates virus replication in mosquito cells. Nucleic Acids Res 40:2210–2223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carbonell A, Carrington JC. 2015. Antiviral roles of plant ARGONAUTES. Curr Opin Plant Biol 27:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollari M, De S, Wang A, Makinen K. 2020. The potyviral silencing suppressor HCPro recruits and employs host ARGONAUTE1 in pro-viral functions. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008965. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YW, Hu CC, Tsai CH, Lin NS, Hsu YH. 2019. Nicotiana benthamiana Argonaute10 plays a pro-viral role in Bamboo mosaic virus infection. New Phytol 224:804–817. doi: 10.1111/nph.16048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minevich G, Park DS, Blankenberg D, Poole RJ, Hobert O. 2012. CloudMap: a cloud-based pipeline for analysis of mutant genome sequences. Genetics 192:1249–1269. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.144204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bukhari SI, Vasquez-Rifo A, Gagne D, Paquet ER, Zetka M, Robert C, Masson JY, Simard MJ. 2012. The microRNA pathway controls germ cell proliferation and differentiation in C. elegans. Cell Res 22:1034–1045. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagliuso DC, Bodas DM, Pasquinelli AE. 2021. Recovery from heat shock requires the microRNA pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 17:e1009734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brenner JL, Jasiewicz KL, Fahley AF, Kemp BJ, Abbott AL. 2010. Loss of individual microRNAs causes mutant phenotypes in sensitized genetic backgrounds in C. elegans. Curr Biol 20:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding L, Spencer A, Morita K, Han M. 2005. The developmental timing regulator AIN-1 interacts with miRISCs and may target the argonaute protein ALG-1 to cytoplasmic P bodies in C. elegans. Mol Cell 19:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marques JT, Wang JP, Wang X, de Oliveira KP, Gao C, Aguiar ER, Jafari N, Carthew RW. 2013. Functional specialization of the small interfering RNA pathway in response to virus infection. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003579. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouasker S, Simard MJ. 2012. The slicing activity of miRNA-specific Argonautes is essential for the miRNA pathway in C. elegans. Nucleic Acids Res 40:10452–10462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakowski MA, Desjardins CA, Smelkinson MG, Dunbar TL, Lopez-Moyado IF, Rifkin SA, Cuomo CA, Troemel ER. 2014. Ubiquitin-mediated response to microsporidia and virus infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanguy M, Veron L, Stempor P, Ahringer J, Sarkies P, Miska EA. 2017. An alternative STAT signaling pathway acts in viral immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. mBio 8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00924-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Pen J, Jiang H, Di Domenico T, Kneuss E, Kosałka J, Leung C, Morgan M, Much C, Rudolph KLM, Enright AJ, O'Carroll D, Wang D, Miska EA. 2018. Terminal uridylyltransferases target RNA viruses as part of the innate immune system. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25:778–786. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stinchcomb DT, Shaw JE, Carr SH, Hirsh D. 1985. Extrachromosomal DNA transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cell Biol 5:3484–3496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3484-3496.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anisimova M, Gascuel O. 2006. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: a fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst Biol 55:539–552. doi: 10.1080/10635150600755453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Le SQ, Gascuel O. 2008. An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol Biol Evol 25:1307–1320. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S4 and Tables S1 to S3. Download jvi.00065-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.2 MB (1.2MB, pdf)