ABSTRACT

Noroviruses are the leading cause of outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis. These viruses usually interact with histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs), which are considered essential cofactors for norovirus infection. This study structurally characterizes nanobodies developed against the clinically important GII.4 and GII.17 noroviruses with a focus on the identification of novel nanobodies that efficiently block the HBGA binding site. Using X-ray crystallography, we have characterized nine different nanobodies that bound to the top, side, or bottom of the P domain. The eight nanobodies that bound to the top or side of the P domain were mainly genotype specific, while one nanobody that bound to the bottom cross-reacted against several genotypes and showed HBGA blocking potential. The four nanobodies that bound to the top of the P domain also inhibited HBGA binding, and structural analysis revealed that these nanobodies interacted with several GII.4 and GII.17 P domain residues that commonly engaged HBGAs. Moreover, these nanobody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) extended completely into the cofactor pockets and would likely impede HBGA engagement. The atomic level information for these nanobodies and their corresponding binding sites provide a valuable template for the discovery of additional “designer” nanobodies. These next-generation nanobodies would be designed to target other important genotypes and variants, while maintaining cofactor interference. Finally, our results clearly demonstrate for the first time that nanobodies directly targeting the HBGA binding site can function as potent norovirus inhibitors.

IMPORTANCE Human noroviruses are highly contagious and a major problem in closed institutions, such as schools, hospitals, and cruise ships. Reducing norovirus infections is challenging on multiple levels and includes the frequent emergence of antigenic variants, which complicates designing effective, broadly reactive capsid therapeutics. We successfully developed and characterized four norovirus nanobodies that bound at the HBGA pockets. Compared with previously developed norovirus nanobodies that inhibited HBGA through disrupted particle stability, these four novel nanobodies directly inhibited HBGA engagement and interacted with HBGA binding residues. Importantly, these new nanobodies specifically target two genotypes that have caused the majority of outbreaks worldwide and consequently would have an enormous benefit if they could be further developed as norovirus therapeutics. To date, we have structurally characterized 16 different GII nanobody complexes, a number of which block HBGA binding. These structural data could be used to design multivalent nanobody constructs with improved inhibition properties.

KEYWORDS: nanobody, antiviral, norovirus, structural biology

INTRODUCTION

Human norovirus was discovered over half a century ago (1), and yet, there are still no available vaccines, antivirals, or treatments. Noroviruses are highly contagious, infecting all age groups, and infection can result in a sudden onset of diarrhea, severe vomiting, nausea, and fever. Noroviruses infect ~685 million people each year worldwide, killing more than 220,000 (2). Noroviruses cause major economic losses (e.g., outbreaks in hospital wards and cruise ships) estimated at $60US billion per year globally (2).

Human noroviruses have a single-stranded, positive sense RNA genome of ~7.7 kb. The norovirus genome contains three open reading frames (ORFs), where ORF1 encodes the nonstructural proteins and includes the protease and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), ORF2 encodes the capsid protein (VP1), and ORF3 encodes a small protein (VP2). Human noroviruses are divided into at least 10 genogroups (GI to GX), with GI and GII causing most human infections, while GIV, GVIII, and GIX are less prevalent in humans (3). These genogroups are further subdivided into genotypes and variants. The GII genotype 4 (GII.4) noroviruses have caused the vast majority of outbreaks in the past decade worldwide and evolve ~5% every other year, although several other genotypes (e.g., GII.3 and GII.17) emerged recently as clinically relevant noroviruses causing large outbreaks around the world (4). This significant genotype and antigenic diversity cause enormous challenges for both universal vaccine and therapeutic discovery.

Expression of the capsid VP1 gene in insect and mammalian cells leads to the self-assembly of norovirus virus-like particles (VLPs) that are morphologically and antigenically similar to native virions and are composed of 90 copies of VP1 (5). These VLPs have been instrumental in the development of antibody reagents and vaccine candidates and for studying host tropism. The VP1 is divided into two domains, namely, shell (S) and protruding (P), where the S domain surrounds the viral RNA and the P domain, which can be further subdivided into P1 and P2 subdomains, contains the determinants for cofactor binding and antibody recognition (5). The capsid P domain engages histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs; two sites per P domain dimer), which are recognized cofactors and are essential for most norovirus infections (6). Based on the ABH- and Lewis-HBGA types, at least nine different HBGA types were found to interact with human noroviruses, although HBGA types and binding sites can vary among genogroups and genotypes (7–9). In addition to HBGAs, bile acid was found to be vital or to enhance human norovirus replication in cell culture for certain norovirus genotypes and is considered another important cofactor (10–12). Moreover, we reported recently the bile acid binding site for GII.1, GII.10, and GII.19 and showed that bile acid binding to the capsid is critical for HBGA engagement for GII.1 noroviruses (13, 14). The precise bile acid binding sites for other norovirus genotypes remain unknown.

Presently, several companies are evaluating norovirus VLPs in vaccine trials, which are reviewed in reference 15. The most advanced VLP candidates are in phase IIb and incorporate a bivalent formulation of GI.1/GII.4c VLPs. This vaccine candidate was able to elicit antibodies that are cross-reactive against noroviruses from different genogroups; however, the efficacy of the vaccine was only modest (16). Currently, as the complete human norovirus receptor repertoire remains unknown, antiviral development is focused largely on the capsid protein, specifically targeting the HBGA binding pocket to inhibit attachment and entry (17). A number of studies have identified norovirus-specific antibodies that interfere with HBGA binding and treatment, and several of these antibodies are linked with a decreased risk of infection, which is reviewed in reference 18. One recent study examined serum from vaccinated patients and characterized one neutralizing antibody that also blocked the HBGA binding pocket (19). Other groups have screened drug libraries and natural compounds for capsid inhibitors (17, 20–24). We have identified various HBGA blocking inhibitors, including human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), citrate, and natural extracts (25–29).

These promising results suggest that therapeutics obstructing the HBGA binding site have the potential to act as antivirals and have led us to develop norovirus nanobody-based inhibitors. Nanobodies are ~15-kDa single-domain antibodies with three complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that benefit from strong-antigen binding affinities, can bind to cryptic sites on virus particles, and have low immunogenicity (30). Importantly, therapeutic nanobodies show promising results as antiviral agents for influenza virus, human respiratory syncytial virus, and SARS-CoV-2 (31–33). Previously, we characterized several GII.10 nanobodies that blocked norovirus VLPs from binding to HBGAs (34). We found that the nanobody binding epitopes were positioned at a critical cryptic and vulnerable region located between the S and P domains and showed that nanobody engagement disrupted VLP stability and resulted in VLP disassembly and aggregation (34, 35).

The current study sought to identify nanobodies that efficiently prevent GII.4 and GII.17 VLPs from binding to HBGAs and to determine the nanobody binding sites using X-ray crystallography. We discovered a number of nanobodies that have HBGA-blocking capacities and showed that four nanobodies completely blocked the GII.4 and GII.17 HBGA binding sites. These new findings are critical for understanding neutralizing mechanisms with nanobodies that directly inhibit the HBGA cofactor binding site and have the exciting potential to be further developed into norovirus therapeutics.

RESULTS

In this study, we analyzed nine new norovirus-specific nanobodies that were produced in alpaca against norovirus VLPs representing two clinically important GII genotypes, namely, GII.4 Sydney-2012 (NB-30, NB-53, NB-56, NB-76, and NB-82) and GII.17 Kawasaki308 (NB-2, NB-7, NB-34, and NB-45). These nine nanobodies were chosen based on the amino acid variation in the CDRs with an overall sequence identity ranging between 62 and 82%. In order to compare these nine nanobodies with previously reported norovirus nanobodies and monoclonal antibodies, the binding interactions, HBGA blocking capacities, and X-ray crystal structures were analyzed using established methods (34–37).

Nanobody binding specificities.

The GII.4 and GII.17 nanobody binding specificities were analyzed initially using a direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the corresponding immunization VLP antigens as described previously for GI.1 and GII.10 nanobodies (34, 37). All five GII.4 nanobodies bound to the GII.4 Sydney-2012 VLPs (Fig. 1A). NB-56 showed the strongest binding and at the lowest concentration (0.05 μg/mL) with a maximum signal (optical density at 490 nm [OD490], 3.5). NB-82 also exhibited strong binding over the dilution range with an OD490 of 2.0 at the lowest nanobody concentration. Likewise, NB-30 and NB-53 showed strong binding with an OD490 of 0.8 and 1.0, respectively, at the lowest nanobody concentration. NB-76 reached the cutoff at a concentration of 0.38 μg/mL. All four GII.17 nanobodies bound to the GII.17 Kawasaki308 VLPs (Fig. 1B). The strongest binders were NB-34 and NB-45, with an OD490 of 0.8 and 0.6, respectively, at the lowest nanobody concentration. NB-7 and NB-2 reached the cutoff at a concentration of 1.56 and 0.78 μg/mL, respectively.

FIG 1.

ELISA was performed to determine nanobody binding to VLPs. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the standard deviation is shown. The cutoff value was set at an OD490 of 0.15 (dashed line). (A) GII.4 nanobodies binding to GII.4 Sydney-2012 VLPs, where NB-56 strongly bound to GII.4 VLPs at all dilutions, followed by NB-82, NB-53, NB-30, and NB-76. (B) GII.17 nanobodies binding to GII.17 Kawasaki308 VLPs, where NB-45 strongly bound to GII.17 VLPs at all dilutions, followed by NB-34, NB-2, and NB-7.

Nanobody cross-reactivity.

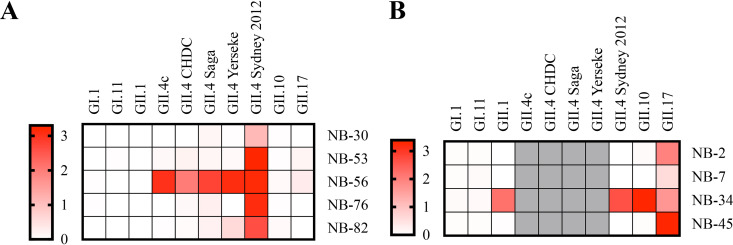

Nanobody cross-reactivities were analyzed with a panel of VLPs from GI and GII (i.e., GI.1, GI.11, GII.1, GII.4, GII.10, and GII.17) and five different GII.4 variants (89.61 to 98.7% amino acid identity) as described previously (38). NB-30, NB-76, and NB-82 were mainly GII.4 Sydney-2012 specific, whereas NB-56 was able to bind strongly to all GII.4 variants (Fig. 2A). NB-53 and NB-56 showed weak cross-reactivity with GII.17 VLPs. Three GII.17 nanobodies (NB-2, NB-7, and NB-45) were genotype specific, whereas NB-34 cross-reacted strongly with GII.1, GII.4, GII.10, and GII.17 VLPs (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Nanobody cross-reactivities were analyzed using a panel of GI and GII noroviruses in direct ELISA. The results are colored on the heatmap schematic, where the OD492 of 3.0 represents strong binding (red) and an OD492 of 0 represents no binding (white). (A) The GII.4 nanobodies were mainly GII.4 specific. NB-56 bound to five different GII.4 variants (i.e., GII.4c, CHDC, Saga, Yerseke, and Sydney-2012), whereas NB-30, NB-53, NB-76, and NB-82 all detected GII.4 Sydney-2012 VLPs and weakly detected several GII.4 variants. (B) NB-34 detected GII.1, GII.4, and GII.10 VLPs, whereas NB-7, NB-2, and NB-45 detected only GII.17 VLPs. Of note, for GII.17 nanobodies, only GII.4 Sydney-2012 VLPs were examined.

HBGA blocking properties of nanobodies.

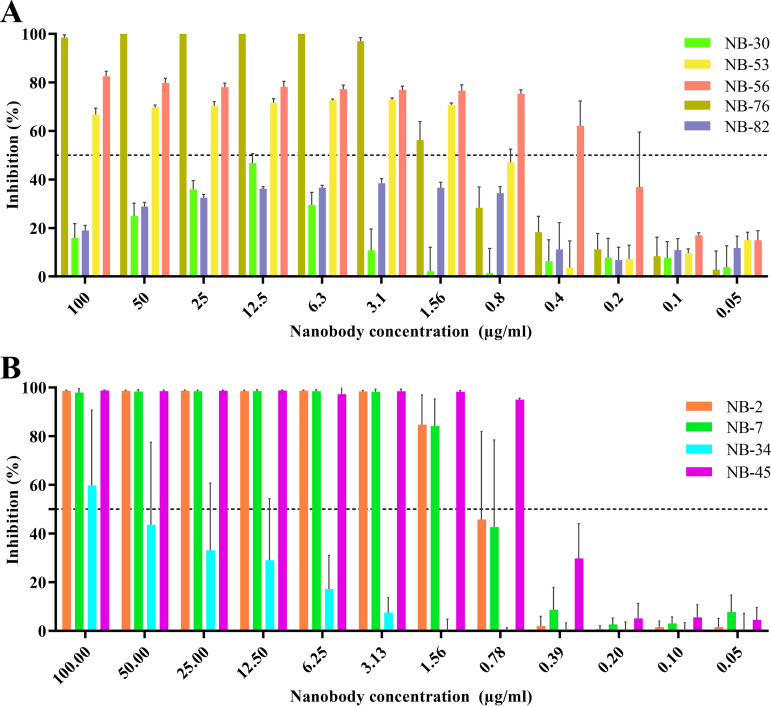

In order to determine the HBGA blocking potential of the nanobodies, a well-established surrogate HBGA neutralization assay was performed using GII.4 and GII.17 VLPs (19, 34, 37, 39, 40). For GII.4 nanobodies, we found that NB-56 had the strongest HBGA blocking capacity with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.26 μg/mL, followed by NB-53 (IC50, 0.76 μg/mL) and NB-76 (IC50, 1.42 μg/mL) (Fig. 3A). The IC50 for NB-30 and NB-82 could not be calculated since the HBGA inhibition was below 50% for all dilutions. For GII.17 nanobodies, NB-45 showed the strongest blocking capacity with an IC50 of 0.46 μg/mL, followed by NB-2 (IC50, 0.85 μg/mL), NB-7 (IC50, 0.88 μg/mL), and NB-34 (IC50, 15.33 μg/mL) (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Nanobody inhibition of VLP attachment to porcine gastric mucin (PGM). VLPs were preincubated with serially diluted nanobodies and added to PGM-coated plates to analyze the ability for the nanobodies to block VLP binding to HBGAs. (A) For the GII.4 nanobodies, NB-53 (IC50, 0.76 μg/mL), NB-56 (IC50, 0.26 μg/mL), and NB-76 (IC50, 1.417 μg/mL) showed a dose-dependent inhibition, whereas NB-30 and NB-82 IC50 values were not calculated since the inhibition was below 50% for all dilutions. (B) For the GII.17 nanobodies, NB-45 showed the lowest IC50 value (0.46 μg/mL), followed by NB-2 (IC50, 0.84 μg/mL), NB-7 (IC50, 0.88 μg/mL), and NB-34 (IC50 = 15.33 μg/mL).

Thermodynamic properties.

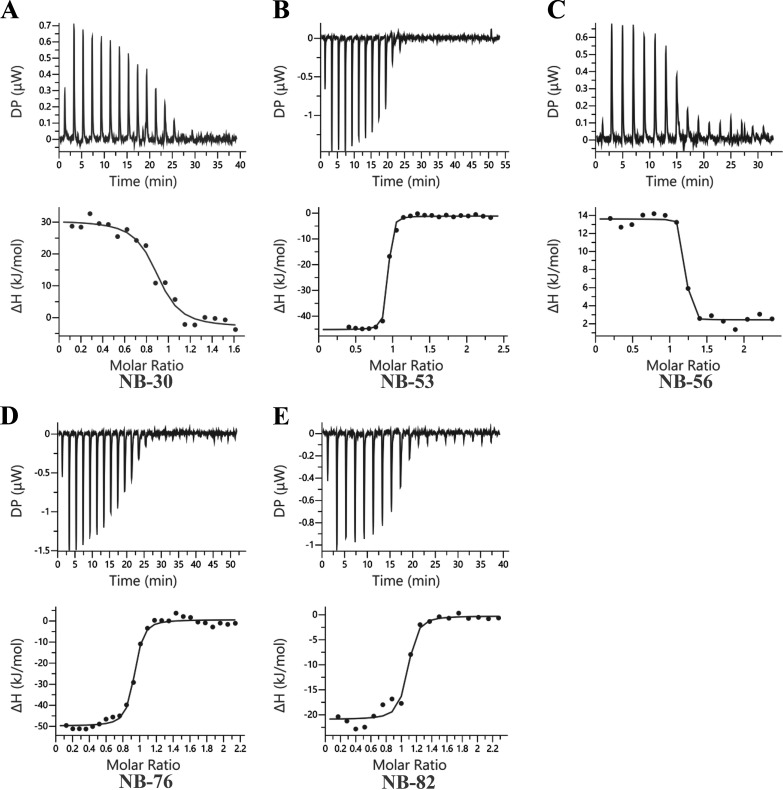

The thermodynamic properties of nanobodies binding to GII.4 Sydney-2012 and GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domains were analyzed using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Titrations were performed at 25°C by injecting consecutive aliquots of 100 μM nanobodies into 15 μM P domain (Fig. 4 and 5). The stoichiometry indicated the binding of one nanobody molecule per P domain monomer. Most of the nanobodies (NB-53, NB-76, NB-82, NB-2, NB-7, NB-34, and NB-45) exhibited exothermic binding, while NB-30 and NB-56 were characterized by a positive enthalpy change associated with an endothermic type of reaction. The binding constants, namely, dissociation constant (Kd), heat change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), and change in free energy (−TΔG), are summarized in Table 1. All the nanobodies bound tightly to the P domain, with the Kd ranging between 3.8 nM and 180 nM.

FIG 4.

Thermodynamic properties of GII.4 nanobody binding to GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain. The binding constants are dissociation constant (Kd; M), heat change (ΔH; cal/mole), entropy change (ΔS; cal/mole/deg), and change in free energy (ΔG, cal/mol). Titrations were performed at 25°C by injecting consecutive (2 to 3 μL) aliquots of nanobodies (100 μM) into the GII.4 P domain (10 to 20 μM) in 120-s intervals. Examples of the titration (top panel) of Nanobodies to norovirus P domain are shown for NB-30 (A), NB-53 (B), NB-56 (C), NB-76 (D), and NB-82 (E). The binding isotherm was calculated using a single binding site model (bottom panel).

FIG 5.

Thermodynamic properties of GII.17 nanobody binding to GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain. Titrations were performed at 25°C by injecting consecutive (2 to 3 μL) aliquots of nanobodies (100 μM) into the GII.17 P domain (10 to 20 μM) in 120-s intervals. Examples of the titration (top panel) of nanobodies to norovirus P domain are shown for NB-2 (A), NB-7 (B), NB-34 (C), and NB-45 (D). The binding isotherm was calculated using a single binding site model (bottom panel).

TABLE 1.

Summary of ITC measurements

| P domain nanobody | Kd (nM) | ΔH (kJ/mol) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | −TΔS (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII.4-NB-30 | 180 ± 50 | 33.5 ± 0.7 | −38.6 ± 0.7 | −72.2 ± 0.3 |

| GII.4-NB-53 | 16 ± 7 | −44.1 ± 1 | −50 ± 5 | −0.7 ± 2 |

| GII.4-NB-56 | 3.8 ± 4 | 10.5 ± 2 | −50.1 ± 5 | −60.6 ± 3 |

| GII.4-NB-76 | 56.7 ± 7 | −50.7 ± 0.4 | −41.4 ± 0.3 | 9.3 ± 0.6 |

| GII.4-NB-82 | 30.1 ± 24 | −16.3 ± 6 | −43.9 ± 2 | −27.7 ± 7 |

| GII.17-NB-2 | 7.5 ± 1 | −72.1 ± 4 | −46.4 ± 5 | 25.7 ± 4 |

| GII.17-NB-7 | 40.9 ± 6 | −85.0 ± 3 | −42.3 ± 0.3 | 42.8 ± 3 |

| GII.17-NB-34 | 4.8 ± 4 | −69.4 ± 4 | −48.1 ± 2 | 21.2 ± 3 |

| GII.17-NB-45 | 101 ± 82 | −22.7 ± 3 | −41.1 ± 3 | −18.4 ± 6 |

X-ray crystal structures of norovirus P domain and nanobody complexes.

The structures of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain in complex with NB-30, NB-53, NB-56, NB-76, and NB-82 and of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain in complex with NB-2, NB-7, and NB-45 were solved using X-ray crystallography (Table 2 and 3). In addition, the GII.10 P domain in complex with NB-34 was solved using X-ray crystallography to investigate NB-34 cross-reactivity at the atomic level (Table 3). The overall structure of the P domains in the complexes was comparable to the unbound P domains with minimal loop movements upon nanobody engagement. All nanobodies had typical immunoglobulin folds, and the nanobody CDRs interacted primarily with the P domains. The nine nanobodies bound to the P domains at three distinct regions: termed side (NB-30, NB-53, NB-56, and NB-82), bottom (NB-34), and top of P domain (NB-2, NB-7, NB-45, and NB-76).

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for GII.4 nanobodies

| Parameter | Dataa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | GII.4-NB-30 | GII.4-NB-53 | GII.4-NB-56 | GII.4-NB-76 | GII.4-NB-82 |

| PDB ID | 8EN1 | 8EN4 | 8EN5 | 8EN6 | 8EMY |

| Data collection | |||||

| Space group | I 1 2 1 | I 2 2 2 | P1211 | P21212 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 117.77, 62.44, 121.40 | 108.41, 137.29, 140.18 | 61.24, 235.38, 70.57 | 74.41, 119.71, 127.82 | 121.02, 142.46, 207.97 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 101.24, 90.00 | 90, 90 90 | 90.00, 104.30, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 57.75–2.40 (2.49–2.40) | 54.10–2.30 (2.38–2.30) | 235.38–1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 87.37–1.53 (1.56–1.53) | 117.53–1.70 (1.73–1.70) |

| Rmergeb | 0.153 (0.481) | 0.063 (0.386) | 0.045 (0.345) | 0.073 (0.661) | 0.035 (0.373) |

| I/σI | 5.5 (2.10) | 11.8 (3.1) | 11.7 (2.5) | 9.3 (1.5) | 19.1 (2.9) |

| CC1/2 | 0.977 (0.748) | 0.998 (0.931) | 0.997 (0.832) | 0.996 (0.639) | 0.991 (0.712) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.7) | 99.7 (98.3) | 98.7 (96.9) | 99.8 (98.4) | 96.9 (77.0) |

| Redundancy | 5.0 (4.6) | 5.1 (5.0) | 3.4 (3.5) | 4.4 (4.0) | 4.3 (3.7) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 46.2–2.4 (2.486–2.4) | 42.91–2.3 (2.382–2.3) | 58.85–1.6 (1.657–1.6) | 64.31–1.6 (1.657–1.6) | 61.39–1.7 (1.761–1.7) |

| No. of unique reflections | 34,068 (3,401) | 46,644 (4,616) | 249,862 (24,766) | 150,252 (14,929) | 379,642 (31,716) |

| Rwork/Rfreec | 0.2066/0.2635 (0.2788/0.3437) | 0.2145/0.2479 (0.3339/0.3830) | 0.1859/0.2194 (0.2676/0.3054) | 0.1730/0.1944 (0.2237/0.2559) | 0.1772/0.1999 (0.2366/0.2716) |

| No. of atoms | 7,163 | 6,661 | 15,038 | 7,608 | 22,388 |

| Protein | 6,890 | 6,536 | 13,565 | 6,666 | 19,931 |

| Water | 273 | 113 | 1,317 | 872 | 2,317 |

| Ligand | 0 | 12 | 192 | 100 | 242 |

| Avg B factors (Å2) | 28.33 | 50.19 | 28.84 | 17.64 | 26.3 |

| Protein | 28.37 | 50.36 | 28.25 | 16.57 | 25.33 |

| Water | 27.28 | 41.01 | 34.23 | 25.19 | 34.16 |

| Ligand | 0 | 45.24 | 34.67 | 25.72 | 34.56 |

| RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| RMSDd bond angle (°) | 0.61 | 0.53 | 1.21 | 1.25 | 0.79 |

| Ramachandran plot statisticse | |||||

| No. of residues | 877 | 841 | 1,736 | 855 | 2,563 |

| Most favored region | 96.78 | 97.84 | 97.33 | 98.58 | 97.64 |

| Allowed region | 3.11 | 2.04 | 2.44 | 1.42 | 2.36 |

| Outliers | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 |

| Clashscore | 4.02 | 3.81 | 4.96 | 3.55 | 2.57 |

Numbers in parenthesis represent highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = where is the mean of observations of reflection h.

Rfactor and Rfree = for 95% of recorded data (Rfactor) or 5% data (Rfree).

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Determined using MolProbity (10.1002/pro.3330).

TABLE 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics for GII.17 nanobodies

| Parameter | Dataa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | GII.17-NB-2 | GII.17-NB-7 | GII.10-NB-34 | GII.17-NB-45 |

| PDB ID | 8EMZ | 8EN0 | 8EN2 | 8EN3 |

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | C121 | I222 | P1211 | P1211 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 92.96, 90.54, 59.40 | 74.82, 85.46, 223.85 | 66.78, 80.53, 84.21 | 79.50, 71.31, 82.62 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.000, 116.289, 90.000 | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.000, 90.025, 90.000 | 90.000, 113.320, 90.000 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 61.322–1.401 (1.49–1.40) | 111.926–2.989 (3.17–2.99) | 80.528–1.850 (1.96–1.85) | 49.082–2.100 (2.23–2.10) |

| Rmergeb | 0.037 (0.94) | 0.286 (1.859) | 0.074 (1.107) | 0.329 (1.046) |

| I/σI | 24.39 (2.19) | 9.10 (1.31) | 16.48 (1.73) | 5.21 (1.54) |

| CC1/2 | 100 (77.1) | 99.4 (56.6) | 99.9 (70.7) | 97.8 (62.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.5 (97.7) | 95.5 (97.9) | 99.1 (98.5) | 99.8 (99.7) |

| Redundancy | 7.05 (6.97) | 13.4 (13.3) | 7.10 (7.01) | 6.87 (6.37) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 34.96–1.401 (1.451–1.401) | 56.29–2.99 (3.097–2.99) | 43.88–1.85 (1.917–1.85) | 44.53–2.1 (2.175-2.1) |

| No. of unique reflections | 85,354 (8,437) | 14,271 (1,418) | 75,469 (7,441) | 49,637 (4,896) |

| Rwork/Rfreec | 0.1953/0.2196 (0.2944/0.3261) | 0.2489/0.3053 (0.3648/0.3164) | 0.2084/0.2344 (0.3323/0.3744) | 0.2126/0.2625 (0.2492/0.3098) |

| No. of atoms | 3,750 | 3,318 | 7,056 | 7,166 |

| Protein | 3,400 | 3,297 | 6,758 | 6,739 |

| Water | 286 | 21 | 294 | 419 |

| Ligand | 136 | 0 | 10 | 8 |

| Avg B factors (Å2) | 28.16 | 67.56 | 38.4 | 21.06 |

| Protein | 27.58 | 67.57 | 38.62 | 21.01 |

| Water | 32.99 | 65.15 | 33.68 | 21.65 |

| Ligand | 37.14 | 0 | 20 | 29.38 |

| RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.008 |

| RMSDd bond angle (°) | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.89 |

| Ramachandran plot statisticse | ||||

| No. of residues | 433 | 425 | 876 | 861 |

| Most favored region | 96.97 | 95.25 | 96.88 | 96.13 |

| Allowed region | 3.03 | 4.04 | 2.78 | 3.87 |

| Outliers | 0 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 0 |

| Clashscore | 7.22 | 7.9 | 3.83 | 4.33 |

Numbers in parenthesis represent highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = where is the mean of observations of reflection h.

Rfactor and Rfree = for 95% of recorded data (Rfactor) or 5% data (Rfree).

RMSD, root mean square deviation.

Determined using MolProbity (10.1002/pro.3330).

Nanobodies binding to the side of the P domain.

The GII.4 P1 subdomain comprises residues 224 to 274 and 418 to 530, whereas the P2 subdomain is between residues 275 and 417 (8). We found that NB-30 bound to the side of the GII.4 P domain dimer (Fig. 6A). A network of direct hydrogen bonds was formed between NB-30 and both P domain monomers (Fig. 6B). Nine GII.4 P domain residues (chain A: GLY-288, TRP-308, ASP-310, ARG-339, and ASN-380; chain B: GLU-235, LYS-248, VAL-508, and ASN-512) formed 11 hydrogen bonds with NB-30. In this location, NB-30 interacted with both GII.4 P1 and P2 subdomain residues.

FIG 6.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-30 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 P domain NB-30 complex was determined to 1.70-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P dimer and two NB-30 molecules in space group I121. The GII.4 P domain monomers were colored accordingly (chain A, black; chain B, gray; and NB-30, green). (A) NB-30 bound to the side of the P1 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with both P domain chains A and B with an interface area of ~1,182 Å2. (B) A closeup view of the GII.4 P domain and NB-30 interacting residues (note, only main or side chains that are forming hydrogen bonds are shown for simplicity). The GII.4 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. Electrostatic interactions were found between A chain: ASP-310GII.4 and ARG-110NB-30; ARG-339GII.4 and GLU-115NB-30; and B chain: LYS-248GII.4 and ASP-101NB-30; ASP-481GII.4 and ARG-54NB-30. Based on previous norovirus nanobodies (34, 35), the CDRs for NB-30 were located approximately at CDR1 (26 to 33), CDR2 (51 to 58), and CDR3 (99 to 117).

We also discovered that NB-53 also bound to the side of the GII.4 P domain (Fig. 7A). Seven GII.4 P domain residues located on both P domain monomers formed 15 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-53 (subdomain P1 chain A: ARG-484 and VAL-508; subdomain P2 chain B: ASN-307, TRP-308, ASN-309, ASP-310, and ASN-380) (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, NB-53 and NB-30 binding sites are in a similar location on the side of the P domain. Moreover, several P domain residues interacting with NB-30 and NB-53 were shared (i.e., TRP-308, ASP-310, ASN-380, and VAL-508).

FIG 7.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-53 complex. The GII.4 P domain NB-53 complex was determined to 2.30-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P dimer and two NB-53 molecules in space group I222. (A) NB-53 (yellow) bound to the side of the P1 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~859 Å2. (B) A closeup view of the GII.4 P domain and NB-53 interacting residues. The GII.4 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. Electrostatic interactions were found between A chain: ARG-484GII.4 and ASP-27NB-53; and B chain: ASP-310GII.4 and HIS-59NB-53; ASP-310GII.4 and LYS-64NB-53. The CDRs for NB-53 were approximately located at CDR1 (25 to 32), CDR2 (52 to 55), and CDR3 (98 to 104).

Comparable to the NB-30 and NB-53 binding footprint, we found that NB-56 bound on the side of the GII.4 P domain and interacted with both P domain monomers (Fig. 8A). Eleven P domain residues on P1 and P2 subdomains (chain A: LYS-248, GLN-504, ASP-506, VAL-508, and ILE-509; chain B: ASP-289, ASN-302, ASN-309, ASP-310, ASN-378, and ASN-380) formed 20 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-56 (Fig. 8B). Several GII.4 P domain residues interacting with NB-56 and NB-53 (ASN-380 and VAL-508) and NB-30 (LYS-248, ASP-310, ASN-380, and VAL-508) were shared.

FIG 8.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-56 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 P domain NB-56 complex was determined to 1.60-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated two P dimers and four NB-56 molecules in space group P1211. (A) The NB-56 (salmon) bound to the side of the P1 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~1,215 Å2. (B) A closeup view of GII.4 P domain and NB-56 interacting residues. The GII.4 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. An electrostatic interaction was found between chain B ASP-289GII.4 and ARG-108NB-56. The CDRs for NB-56 were approximately located at CDR1 (26 to 32), CDR2 (52 to 55), and CDR3 (98 to 118).

Interestingly, NB-30, NB-53, and NB-56 and the previously determined Nano-32 bound to the side of the P domain at a similar location (Fig. 9), and three nanobodies (NB-53, NB-56, and Nano-32) showed HBGA blocking potential (Fig. 3) (34). Moreover, a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (termed A1431) isolated from a patient immunized with the GII.4c VLP vaccine also bound to the side of the P domain at a region nearby this common nanobody binding site (Fig. 9) (19).

FIG 9.

Binding site of NB-30, NB-53, and NB-56. Superposition of GII.4 P domain NB-30, GII.4 P domain NB-53, GII.4 P domain NB-56, GII.10 P domain Nano-32 (5O03), GII.10 P domain A-trisaccharide (3PA1), and GII.4 P domain A1431 (6N8D) onto the GII.10 P domain (3ONU). NB-30 (green), NB-53 (yellow), NB-56 (salmon), Nano-32 (dark salmon), monoclonal antibody A1431 (light blue), and A-trisaccharide (blue) are shown on the GII.10 P domain dimer (gray/black surface). Only one nanobody and monoclonal antibody are shown for clarity.

We discovered that NB-82 bound on the side of the GII.4 P domain and interacted with only one P domain monomer (Fig. 10A). Unlike NB-30, NB-53, and NB-56, which were positioned down toward the P domain, NB-82 was positioned across the P domain. Moreover, the NB-82 binding footprint was distinct from other GI.1 and GII.10 nanobodies (34, 35, 37). Ten P domain residues located mainly on the P2 subdomain formed 13 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-82 (chain A: ASN-302, THR-314, GLU-315, LEU-362, ARG-364, SER-409, THR-413, HIS-414, HIS-417, and LEU-418) (Fig. 10B).

FIG 10.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-82 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 P domain NB-82 complex was determined to 1.70 Å-resolution. Molecular replacement indicated three P dimers and six NB-82 molecules in space group P212121. (A) The NB-82 (navy) bound to the side region of the P domain and involved a monomeric interaction with an interface area of ~832 Å2. (B) A closeup view of GII.4 P domain and NB-82 interacting residues showing hydrogen bonds from both side and main chains. An electrostatic interaction was found between chain A, HIS-417GII.4 and ASP-104NB-82. The CDRs for NB-82 were located approximately at CDR1 (25 to 34), CDR2 (51 to 58), and CDR3 (100 to 103).

Nanobody binding to the bottom of the P domain.

The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.10 P domain with NB-34 was determined to explain nanobody cross-reactivity binding interactions at the atomic level. The GII.10 P1 subdomain is located between residues 222 and 277 and residues 427 and 549, while the P2 subdomain is between residues 278 and 426 (9). NB-34 bound to the bottom of the GII.10 P domain (Fig. 11A). Twelve P domain residues located mostly in the P1 subdomain formed 16 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-34 (chain A: ASP-269, GLU-271, LEU-272, GLY-274, THR-276, ASP-320, TYR-470, and SER-473; chain B: GLU-236, PRO-488, GLU-489, and ARG-492) (Fig. 11B).

FIG 11.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.10 P domain NB-34 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the complex was determined to 1.85-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated two P domains and two NB-34 molecules in space group P1211. (A) The NB-34 (cyan) bound to the side of the domain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~1,017 Å2. (B) A closeup view of GII.10 P domain and NB-34 interacting residues. The GII.10 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. An electrostatic interaction was found between chain A, ASP-269GII.10 and ARG-103NB-34, as well as between GLU-271GII.10 and ARG-103NB-34. The CDRs for NB-34 were approximately located at CDR1 (26 to 33), CDR2 (51 to 58), and CDR3 (99 to 107).

The ELISA showed that NB-34 cross-reacted against GII.1, GII.4, GII.10, and GII.17 VLPs (Fig. 2). The NB-34 binding site was almost identical to a broadly reactive diagnostic nanobody, termed Nano-26, and nearby a binding site of broadly reactive monoclonal antibody (A1227) which was isolated from a patient immunized with the GII.4c VLP vaccine (Fig. 12A) (19, 34, 41). Superposition of GII.1, GII.4, and GII.17 apo X-ray crystal structures onto the GII.10 Vietnam026 P domain NB-34 complex revealed that the residues that formed direct hydrogen bonds with NB-34 were comparatively conserved among these four genotypes despite numerous amino acid insertions and deletions among these genotypes (Fig. 12B). Indeed, seven P domain residues that interacted with Nano-26 also formed direct hydrogen bonds with NB-34 (i.e., ASP-269, GLU-271, LEU-272, GLY-274, THR-276, TYR-470, and PRO-488).

FIG 12.

Structural basis of NB-34 cross-reactivity. (A) Superposition of the GII.10 P domain Nano-26 complex (5O04, Nano-32 light magenta) and GII.4 P domain A1227 (6N81, monoclonal antibody A1227 purple) onto GII.10 Vietnam026 P domain NB-34 complex showing a highly similar binding region on the side of the P domain. (B) Superposition of GII.1 (4ROX, P domain forest), GII.4 (4OOS, P domain green), and GII.17 (5F4O, P domain tv green) P domain apo structures onto the GII.10 Vietnam026 P domain NB-34 complex (P domain gray). The P domain residues for GII.1, GII.4, and GII.17 at the identical location as GII.10 NB-34 binding residues are shown (GII.10 Vietnam026 VP1 numbering); NB-34 was removed for better viewing. NB-34 and Nano-26 bind a common set of seven P domain residues at this location, while amino acid substitutions among these genotypes were observed at only a four residues (underlined), i.e., ASP-320GII.10 (GLU-316GII.4), GLU-271GII.10 (VAL-271GII.4), SER-473GII.10 (ALA-465GII.4), and GLU-489GII.10 (ASP-476GII.1, ASP-481GII.4, and ASP-481GII.17); note that the residue numbering among these genotypes varies.

Nanobodies binding to the top of the P domain.

We found that NB-76 bound to the top of the GII.4 P2 subdomain (Fig. 13A). Eleven P domain residues from both P domain monomers formed 14 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-76 (chain A: LYS-329, SER-355, ALA-356, ASP-357, GLU-368, ASP-391, THR-394, ASN-398, GLN-401, and GLY-443; chain B: THR-344) (Fig. 13B). Superposition of the previously determined GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain A-trisaccharide complex onto the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-76 complex revealed that part of NB-76 CDR2 (LYS-43 and GLN-44) covered the fucose moiety from the A-trisaccharide and was close to the second moiety of the HBGA molecule (Fig. 14). The five GII.4 P domain residues that commonly bind HBGAs include ASP-374, ARG-345, THR-344, GLY-443, and TYR-444. Two of these common HBGA binding residues also bound NB-76 (THR-344 and GLY-443) (Fig. 15A). Structural alignment of CHDC-1974 and Saga-2006 P domains onto the Sydney-2012 P domain (apo and NB-76 complex) confirmed the amino acid substitutions on the P domains at the NB-76 binding residues (Fig. 15A). This structural analysis also revealed a slight loop movement (between residues 391 and 398) upon NB-76 engagement (Fig. 15B).

FIG 13.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-76 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.4 P domain NB-76 complex was determined to 1.60-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P dimer and two NB-76 molecules in space group P212121. (A) The NB-76 (gold) bound to the top of the P2 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~945 Å2. (B) A closeup view of the GII.4 P domain and NB-76 interacting residues. The GII.4 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. Electrostatic interactions were found between chain A: ASP-357GII.4 and GLN-1NB-76 and between ASP-391GII.4 and ARG-45NB-76. The CDRs for NB-76 were located approximately at CDR1 (25 to 33), CDR2 (39 to 46), and CDR3 (98 to 113).

FIG 14.

Close-up of NB-76 blocking the GII.4 HBGA binding pocket. Superposition of the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain A-trisaccharide complex (4WZT) onto the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain NB-76 complex. The GII.4 Sydney-2012 P domain surface representation (black and gray) and A-trisaccharide (blue sticks) are shown.

FIG 15.

Sequence and structural alignment of GII.4 variants. (A) Sequence alignment of GII.4 variants showing NB-76 binding epitopes (gold) and A-trisaccharide binding residues (blue). Two HBGA binding epitopes engaged NB-76 (gold/blue shade). (B) Superposition of apo CHDC-1974 P domain (5IYN; green), apo Saga-2006 P domain (4OOX; orange), and apo Sydney-2012 P domain (4OOS; red) onto Sydney-2012 P-NB76 complex (gray). NB-76 was omitted for clarity, and residue numbering was Sydney-2012, while amino acid conservation and substitutions can be seen in A. The loop containing residues 391 to 398 was slightly shifted upon NB-76 binding.

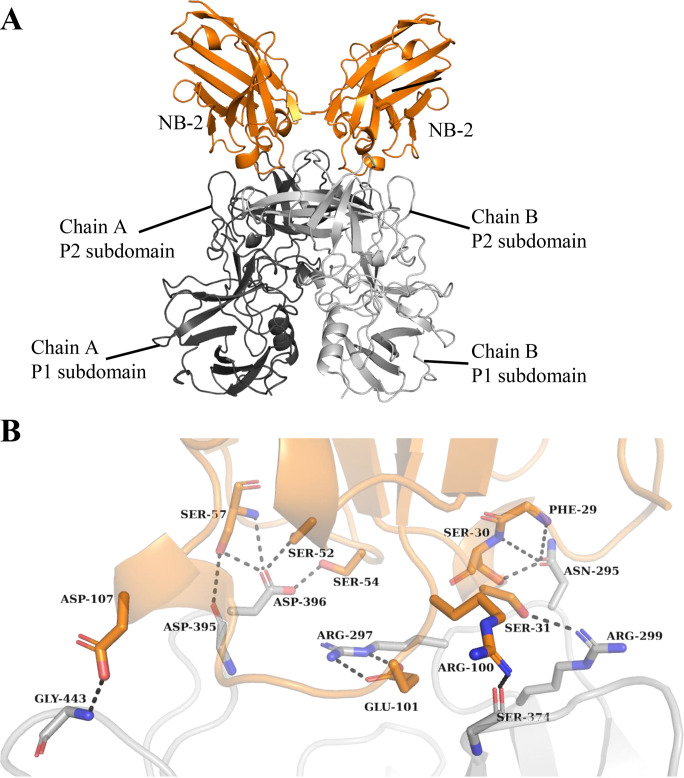

The GII.17 P1 subdomain contains residues 225 and 275 and residues 419 and 540, whereas the P2 subdomain is between residues 276 and 418 (42). We found that NB-2 bound on the top of the GII.17 P2 subdomain and interacted with one of the P domain monomers (Fig. 16A). Seven P domain residues (chain A: ASN-295, ARG-297, ARG-299, SER-374, ASP-395, ASP-396, and GLY-443) formed 13 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-2 (Fig. 16B). Superposition of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain A-trisaccharide complex onto the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-2 complex showed that part of NB-2 CDR3 (PRO-106, ASP-107, and SER-108) covered the second moiety of the HBGA molecule (Fig. 17). In addition, the GII.17 P domain interface loop residues (GLY-443) interacted with NB-2, and this GII.17 P domain residue (TYR-443) that commonly held HBGAs formed a direct hydrogen bond with NB-2 (ASP-107) (Fig. 17).

FIG 16.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-2 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.17 P domain NB-2 complex was determined to 1.40-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P domain and one NB-2 molecule in space group C121. (A) NB-2 (orange) bound to the top of the P2 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~756 Å2. (B) A closeup view of the GII.17 P domain and NB-2 interacting residues. The GII.17 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. An electrostatic interaction was found between chain A ARG-297GII.17 and GLU-101NB-2. The CDRs for NB-2 were located approximately at CDR1 (24 to 33), CDR2 (51 to 58), and CDR3 (99 to 116).

FIG 17.

Close-up of NB-2 blocking the GII.17 HBGA binding pocket. Superposition of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain A-trisaccharide complex (5LKC) onto the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-2 complex. The GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain surface representation (black and gray) and A-trisaccharide (blue sticks) are shown. The GII.17 P domain residues that typically bind HBGAs include THR-348, ARG-349, ASP-378, GLY-443, and TYR-444.

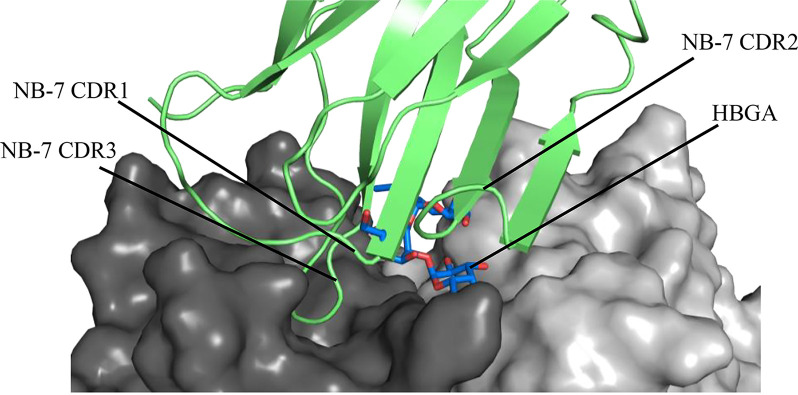

We discovered that NB-7 also bound on the top of the GII.17 P2 subdomain (Fig. 18A) and interacted with one P domain monomer. Six P domain residues formed eight direct hydrogen bonds with NB-7 (chain A: ARG-372, ASN-392, ASP-393, ASP-395, SER-441, and TYR-444) (Fig. 18B). We found that several NB-7 residues (TYR-32 and ARG-33 on CDR2) covered the second moiety of the HBGA molecule, while the TYR-99 side chain (CDR3) overlapped the third moiety of the HBGA molecule (Fig. 19). In addition, the GII.17 P domain interface loop residues (SER-441 and TYR-444) interacted with NB-7 and one GII.17 P domain residue (TYR-444) that commonly held HBGAs formed a direct hydrogen bond with NB-7 (residue GLU-46).

FIG 18.

X-ray crystal structure of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-7 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.17 P domain NB-7 complex was determined to 2.99-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P domain and one NB-7 molecule in space group I222 (only one NB-7 molecule was shown on the P domain dimer for clarity). (A) The NB-7 (lime green) bound to the top of the P2 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~508 Å2. (B) A closeup view of the GII.17 P domain and NB-7 interacting residues. The GII.17 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. The CDRs for NB-7 were located approximately at CDR1 (24 to 32), CDR2 (52 to 56), and CDR3 (99 to 107).

FIG 19.

Close-up of NB-7 blocking the GII.17 HBGA binding site. Superposition of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain A-trisaccharide complex (5LKC) onto the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-7 complex. The GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain surface representations (black and gray) are shown.

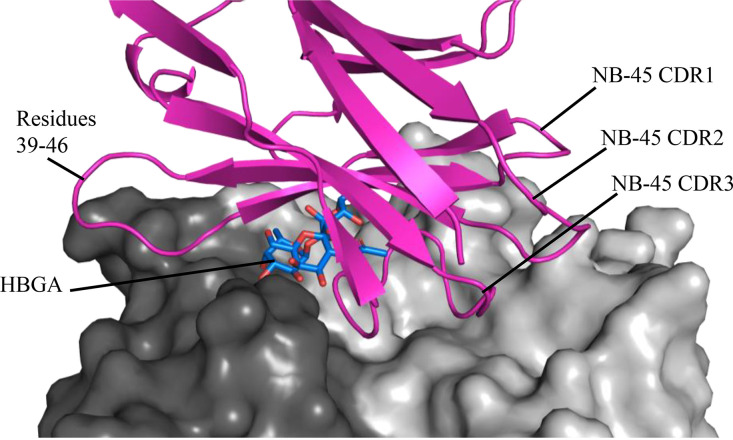

We also found that NB-45 bound on the top of the GII.17 P2 subdomain and interacted with both P domain monomers (Fig. 20A). Thirteen GII.17 P domain residues formed 20 direct hydrogen bonds with NB-45 (chain A: GLN-352, TRP-354, ARG-372, ASN-392, ASP-393, ASP-394, ASP-396, SER-441, GLY-442, and TYR-444; chain B: ASN-295, GLN-296, and GLN-361) (Fig. 20B). Superposition of the GII.17 P domain A-trisaccharide complex onto the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-45 complex revealed that NB-45 CDR2 and CDR3 surrounded the HBGA molecule and likely blocked access to the HBGA site on the P domain (Fig. 21). In addition, GII.17 P domain interface loop residues (SER-441, GLY-442, and TYR-444) interacted with NB-45, and one GII.17 P domain residue (TYR-444) that commonly held HBGAs formed a direct hydrogen bond with NB-45 (residue GLU-46). Furthermore, two NB-45 residues (VAL-48 and ALA-49) clashed with the second moiety of HBGA, and the side chain of one NB-45 residue (SER-108) was in proximity (~1.7 Å) to the fucose moiety of HBGA.

FIG 20.

X-ray crystal structure of GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-45 complex. The X-ray crystal structure of the GII.17 domain NB-45 complex was determined to 2.10-Å resolution. Molecular replacement indicated one P dimer and two NB-45 molecules in space group P1211. (A) The NB-45 (hot pink) bound to the top of the P2 subdomain and involved a dimeric interaction with an interface area of ~1,147 Å2. (B) A closeup view of GII.17 P domain and NB-45 interacting residues. The GII.17 P domain hydrogen bond interactions involved both side and main chain interactions. An electrostatic interaction was observed between chain A, namely, ASP-396GII.17 and HIS-60NB-45. The CDRs for NB-45 were located approximately at CDR1 (27 to 33), CDR2 (53 to 56), and CDR3 (99 to 112).

FIG 21.

Close-up of NB-45 blocking the GII.17 HBGA site. Superposition of the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain A-trisaccharide complex (5LKC) onto the GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain NB-45 complex. The GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domain surface representation (black and gray) and A-trisaccharide (blue sticks) are shown. An additional extended loop on NB-45 (residues 39 to 46) permitted this nanobody to completely overlap the HBGA pocket.

DISCUSSION

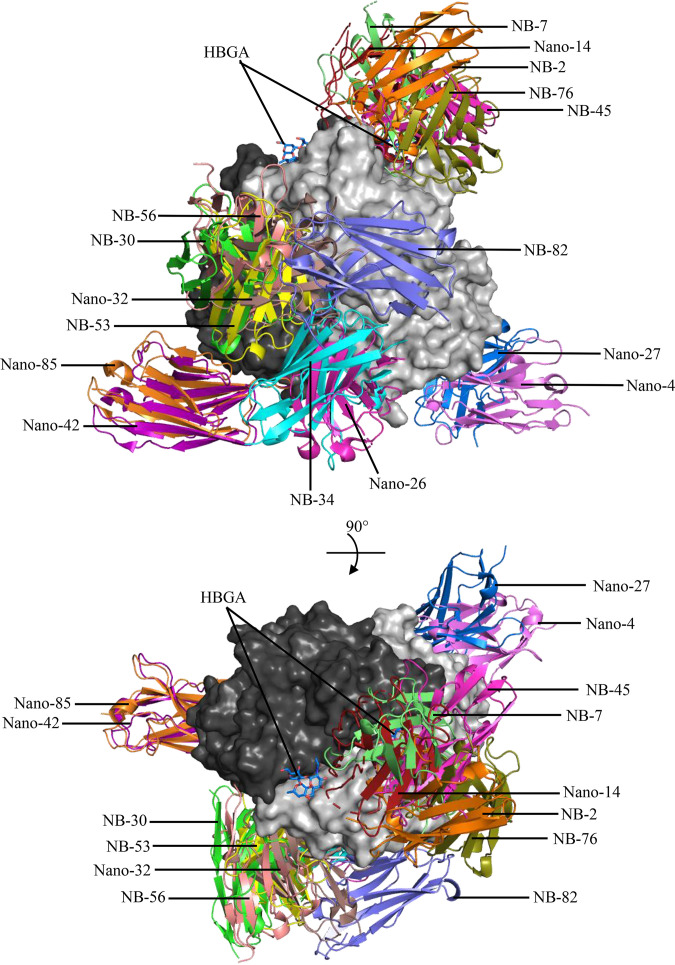

In this study, we have successfully developed a new panel of nanobodies against two major outbreak norovirus genotypes (i.e., GII.4 and GII.17) with the intention of discovering nanobodies that block access to the HBGA binding sites. Both genotypes have been analyzed extensively for HBGA binding interactions, inhibition studies, and capsid evolution (8, 13, 35, 42–57) as well clinical trials using GII.4 VLPs as candidate vaccines, which is reviewed in reference 15. We also have compared the new nanobody structures with previously generated nanobodies developed against the rarely detected GII.10 norovirus (34, 35), which has been characterized extensively in complex with HBGAs, HMOs, and citrate (9, 25–28). We have now characterized the X-ray crystallographic structures for 16 different GII P domain nanobody complexes (Fig. 22).

FIG 22.

Summary of GII norovirus nanobodies. A total of 16 different GII nanobodies were superimposed onto the GII.4 Sydney-2012 P dimer (3PA1; gray) to show nanobody binding sites. Note that only one nanobody per dimer is shown, which includes genotype specific and broadly reactive GII nanobodies (34, 35), as follows: Nano-4 GII.17 P domain (5O02), Nano-14 GII.10 P domain (5OMM), Nano-26 Nano-85 GII.10 P domain (5O04), Nano-27 GII.10 P domain (5OMN), Nano-32 GII.10 P domain (5O03), Nano-42 GII.10 P domain (5O05), and the nine newly characterized nanobodies in this study.

Five nanobodies (Nano-26, Nano-85, NB-34, NB-53, and NB-56) that bound to the bottom or side of the P domain indirectly prevented norovirus VLPs from binding to HBGAs (34). For Nano-85 and Nano-26 (developed against GII.10 VLPs), we showed the nanobody binding epitopes were positioned at a cryptic and vulnerable region located between the S and P domains (34, 35). We found Nano-85 and Nano-26 engagement disrupted VLP stability and resulted in VLP disassembly and aggregation as observed by electron microscopy (34, 35). Similarly, one recent study isolated a human norovirus IgA (antibody noro-320) from a norovirus-infected patient and showed that IgA engagement also led to virion aggregation observed by electron microscopy and neutralization in cell culture (58). Another monoclonal antibody (termed A1431) bound to the side of the P domain (Fig. 9) and was neutralizing in cell culture (19), presumably A1431, sterically blocked norovirus from attaching to large multivalent HBGAs found in porcine gastric mucin (PGM) (19).

Interestingly, NB-34 closely mimicked the Nano-26 binding site, and both nanobodies were broadly reactive and interacted with mainly conserved P domain binding residues. However, the precise HBGA blocking mechanism of these nanobodies that bind to the side of the P domain (i.e., NB-34, NB-53, and NB-56) remains unclear, as VLP disassembly and aggregation after treatment with these nanobodies were not observed (data not shown). On the other hand, the ubiquity of these side binding nanobodies and several monoclonal antibodies suggests that substantial flexibility in virus particles is functionally important for antibody- and nanobody-mediated recognition and/or neutralization (19, 34, 58). Indeed, we also identified a broadly reactive norovirus diagnostic IgG monoclonal antibody (termed 5B18) that bound at a highly conserved and occluded epitope at the bottom of the P domain (59). For these nanobodies and antibodies to interact with the virion, the P domains need to be rather flexible on the S domain. This information suggests that for some antibody- or nanobody-recognition events, the engagement might also result in virus neutralization by interfering with capsid stability that indirectly affects the HBGA binding site and/or sterically blocks HBGA engagement, as was discovered recently with human norovirus nanobodies and monoclonal antibodies (19, 34, 35). Taken together, the side and bottom of the norovirus P domain appear to contain neutralizing epitopes that can also be targeted with antibodies and nanobodies, but the precise structural mechanism of neutralization, such as particle disassembly, aggregation, or steric obstruction of HBGA engagement remains unclear.

Four nanobodies (NB-76, NB-2, NB-7, and NB-45) that bound to the top of the P domain, completely obscured the GII.4 or GII.17 HBGA binding pockets and blocked VLPs from binding to HBGAs. Compared with nanobodies and antibodies that bind to the side of the P domain and indirectly interfere with the HBGA pocket, these four nanobodies interacted with several P domain residues that commonly bind HBGAs and likely sterically obstructed HBGA engagement. Several other inhibitors that impeded the HBGA binding pocket and interacted with P domain residues that bound HBGAs include HMOs and citrate (25–28, 60). These natural compounds closely mimicked the HBGA structures and might function as weak binding antivirals with millimolar affinities (25–28, 60). We also identified a monoclonal antibody (termed 10E9) developed against GII.10 VLPs that partially blocked the HBGA pocket and interacted with several HBGA binding residues (ARG-345 and TYR-444) (43). We also found that this monoclonal antibody inhibited Sydney-2012 VLPs from binding to HBGAs in the surrogate HBGA neutralization assay and GII.4 norovirus replication in cell culture (43).

The discovery of these four nanobodies that bind precisely at the HBGA binding pocket has now opened the door for the further development of cofactor-directed norovirus therapeutics. Using the structural information of other norovirus P domains and docking these nanobodies on nonbinders could highlight CDR residues that could be modified to improve the cross-reactivity against different genotypes and variants, while retaining HBGA blocking capacities. The next stage of this nanobody antiviral development could include testing neutralization capacities using the norovirus cell culture system. Fortunately, the correlation between the HBGA blocking potential using the surrogate HBGA neutralization assay and the norovirus cell culture has been supported in numerous studies, of which several included a structural analysis of inhibitors (12, 19, 43, 58, 61). In summary, we have now identified four new nanobodies that directly impede the HBGA binding pockets for two major norovirus genotypes. Further development of these cofactor-directed norovirus nanobodies as antivirals is now a reality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Norovirus P domain production.

Norovirus GII.4 Sydney-2012 (GenBank accession no. JX459908), GII.10 Vietnam 026 (AF504671), and GII.17 Kawasaki308 (LC037415) P domain were produced as described previously (9). In brief, the P domain gene was cloned into the pMal-c2X vector, followed by transformation into E. coli BL21 (DE) cells. Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C until cells reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 and then were induced with 0.7 mM isopropyl thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) for 18 h at 22°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The fusion P domain-MBP protein was purified using an Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) column, and the MBP tag was cleaved from the P domain using the HRV3C protease at 4°C. After another round of Ni-NTA chromatography, the cleaved P domain was dialyzed in gel filtration buffer (GFB; 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6] and 300 mM NaCl), purified by size exclusion chromatography, concentrated to ~4 mg/mL, and stored at 4°C.

Norovirus VLP production.

The capsid genes of norovirus GI.1 (AY502016.1), GI.11 (AB058547), GII.1 (U07611), GII.4c (62), GII.4 CHDC-1974 (ACT76142), GII.4 Saga-2006 (AB447457), GII.4 Yerseke-2006a (EU876887), GII.4 Sydney-2012, GII.10 Vietnam 026, and GII.17 Kawasaki308 were cloned into a baculovirus expression system as described previously (63). Briefly, the VLPs secreted into the cell medium were separated from Hi5 insect cells by low-speed centrifugation, concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 30,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h (Beckman Ti45), and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The VLPs were purified by CsCl equilibrium gradient ultracentrifugation at 45,000 rpm at 15°C for 18 h (Beckman SW-55), and fractions containing VLPs were pelleted by ultracentrifugation and resuspended in PBS to remove residual CsCl. Fractions were confirmed using electron microscopy (EM), and homogenous particles were pooled and concentrated to 2 to 10 mg/mL in PBS (pH 7.4). The VLP samples were applied to EM grids, washed once in distilled water, stained with 0.75% uranyl acetate, and examined using EM (Zeiss EM 910).

Nanobody production.

The Nanobody libraries were generated at the VIB Nanobody Service Facility with the approval of the ethics commission of Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, Belgium. Briefly, alpacas were injected subcutaneously with GII.4 Sydney-2012 or GII.17 Kawasaki308 VLPs. A nanobody library was constructed and screened for the presence of antigen specific Nanobodies. Nine Nanobodies were selected based on sequence variation in the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs). These nine nanobodies (GII.4: NB-30, NB-53, NB-56, NB-76, and NB-82; and GII.17: NB-2, NB-7, NB-34, and NB-45) were subcloned into a pHEN6C expression vector and expressed in E. coli WK6 cells overnight at 28°C. Expression was induced with 0.7 mM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.9. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the nanobodies were extracted from the periplasm. After removing cell debris by centrifugation, the supernatant containing the nanobodies was collected. The His-tagged nanobodies were first purified using Ni-NTA chromatography, and then, after dialysis into GFB, size exclusion chromatography was performed. Nanobodies were concentrated to 2 to 3 mg/mL and stored in GFB at 4°C.

Nanobody reactivities using ELISA.

The nanobody reactivities against norovirus VLPs were determined using a direct ELISA as described previously (34). Microtiter plates (Maxisorp, Denmark) were coated with 100 μL (2 μg/mL) of GII.4 or GII.17 VLPs in PBS (pH 7.4). Wells were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then blocked with 300 μL of PBS containing 5% skim milk (PBS-SM) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). After wells were washed, 100 μL of serially diluted nanobodies in PBS (from ~10 μM) was added to each well. The wells were washed and then 100 μL of a 1:3,000 dilution of secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-His IgG (Sigma) was added to wells for 1 h at 37°C. After the wash step, 100 μL of substrate o-phenylenediamine and H2O2 was added to wells and left in the dark for 30 min at RT. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 50 μL of 3 N HCl, and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm (OD490). The final OD490 = samplemean minus PBSmean (~0.05). A cutoff limit was set at OD490 of >0.15, which was ~3 times the value of the negative control (PBS). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Nanobody HBGA inhibition.

A surrogate HBGA neutralization assay using porcine gastric mucin (PGM) was performed as described previously (19, 26, 43). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 10 μg/mL of PGM (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C. Coated plates were washed and blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS for 1 h at RT. The nine Nanobodies were serially diluted from a starting concentration of 100 μg/mL and added to GII.4 and GII.17 VLPs with a final concentration of 1 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL, respectively. After a 30-min incubation at RT, the VLP-NB mixture was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The GII.4 VLPs were detected with a polyclonal rabbit anti-GII.4 antibody (34) and followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody, while GII.17 VLPs were detected using biotinylated Nanobody-28 (NB-28) and HRP-conjugated streptavidin. Plates were then developed with o-phenylenediamine and H2O2 in the dark at RT. After 30 min, the reaction was stopped with 6% (vol/vol) HCl, and absorption was measured at OD490. The binding of untreated VLPs was set as a reference value corresponding to 100% binding. The percentage of inhibition was calculated as [1 − (treated VLP mean OD490/mean reference OD490)] × 100. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for inhibition was determined using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0). All experiments were performed in triplicates and the mean and standard deviation calculated.

Nanobody isothermal calorimetry measurements.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were done using an ITC-200 instrument (Malvern). Samples were prepared in PBS and filtered prior to the experiments. Titrations were performed at 25°C by injecting consecutive (2 to 3 μL) aliquots of nanobodies (100 μM) into GII.4 Sydney-2012 or GII.17 Kawasaki308 P domains (10 to 20 μM) in 120-s intervals. Injections were performed until saturation was achieved. To correct for heats of dilution from titrants, control experiments were performed by titrating nanobodies into PBS. The heat associated with the control titration was subtracted from raw binding data prior to fitting. The data were fitted using a single set binding model (Origin 7.0 software). Nanobody binding sites on the P domains were assumed to be identical. All ITC experiments were performed in triplicate with the average and standard deviation calculated.

Purification and crystallization of norovirus P domain and nanobody complexes.

The P domain (GII.4 Sydney-2012, GII.10, or GII.17 Kawasaki308) and nanobody were mixed in a 1:1.4 molar ratio and incubated at 25°C for ~90 min. The complex was purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex-200 column and concentrated to 2.8 to 10 mg/mL. Complex crystals were grown using hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at 18°C for ~6 to 10 days. Crystallization was achieved for each of the following complexes using the indicated conditions: GII.4-NB-30 (0.2 M calcium chloride and 20% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol 3350 [PEG3350]), GII.4-NB-53 (12% [wt/vol] PEG 20000 and 0.1 M MES [pH 6.5]), GII.4-NB-56 (10% [wt/vol] PEG 8000 and 0.1 M morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES; pH 6.0]), GII.4-NB-76 (17% [wt/vol] PEG 4000, 0.0095 M HEPES [pH 7.5], 8.5% [vol/vol] isopropanol, and 15% glycerol), GII.4-NB-82 (0.8 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M bicine [pH 9]), GII.10-NB-34 (1 M lithium chloride, 10% [wt/vol] PEG 6000, and 0.1 M citric acid [pH 5]), GII.17-NB-2 (0.1 M bicine [pH 9] and 30% [wt/vol] PEG 6000), GII.17-NB-7 (0.8 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M citric acid [pH 4]), and GII.17-NB-45 (1.6 M ammonium sulfate, 0.08 M sodium acetate, and 20% [vol/vol] glycerol). Prior to being flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant containing the mother liquor in 30% ethylene glycol.

X-ray data collection, structure solution, and refinement.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY; PETRA III beamlines, P13 and P14), Germany, and processed with XDS (64) and MOSFLM. Structures were solved by molecular replacement in Phaser (65). Structures were refined in multiple rounds of manual model building in Coot (66) and refined with PHENIX (67). Structures were validated with Procheck (68) and Molprobity (69). PISA software was used to determine binding interfaces and to calculate the surface area (70). Binding interfaces and interactions were analyzed using the PDBePISA online server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/) (70) and PyMOL (version 1.2), with hydrogen bond distances of ~2.36 to 3.88 Å and electrostatic distances of ~2.56 to 3.89 Å. Water-mediated interactions were excluded from the analysis. Figures and protein contact potentials were generated using PyMOL.

Data availability.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors of the X-ray crystal structures were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (8EMY, GII.4-NB-82; 8EMZ, GII.17-NB-2; 8EN0, GII.17-NB-7; 8EN1, GII.4-NB-30; 8EN2, GII.10-NB-34; 8EN3, GII.17-NB-45; 8EN4, GII.4-NB-53; 8EN5, GII.4-NB-56; and 8EN6, GII.4-NB-76).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the protein crystallization platform within the excellence cluster CellNetworks of the University of Heidelberg for crystal screening. We acknowledge the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron DESY (PETRA III beamlines, P13 and P14), a member of the Helmholtz Association HGF, for the provision of experimental facilities. Beamtime was allocated for proposal MX-638.

Funding for this study was provided by the CHS foundation, the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung (Glycan-Based Antiviral Agents, Germany), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; FOR2327; Germany), Research Fellow funding from Griffith University (G.S.H.) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC; ID1196520 and ID2009677 [M.v.I.]).

Contributor Information

Grant S. Hansman, Email: g.hansman@griffith.edu.au.

Stacey Schultz-Cherry, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kapikian AZ, Wyatt RG, Dolin R, Thornhill TS, Kalica AR, Chanock RM. 1972. Visualization by immune electron microscopy of a 27-nm particle associated with acute infectious nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J Virol 10:1075–1081. 10.1128/JVI.10.5.1075-1081.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall AJ, Glass RI, Parashar UD. 2016. New insights into the global burden of noroviruses and opportunities for prevention. Expert Rev Vaccines 15:949–951. 10.1080/14760584.2016.1178069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chhabra P, Graaf M, Parra GI, Chan MC, Green K, Martella V, Wang Q, White PA, Katayama K, Vennema H, Koopmans MPG, Vinjé J. 2020. Corrigendum: updated classification of norovirus genogroups and genotypes. J Gen Virol 101:893. 10.1099/jgv.0.001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chhabra P, de Graaf M, Parra GI, Chan MC, Green K, Martella V, Wang Q, White PA, Katayama K, Vennema H, Koopmans MPG, Vinjé J. 2019. Updated classification of norovirus genogroups and genotypes. J Gen Virol 100:1393–1406. 10.1099/jgv.0.001318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad BV, Hardy ME, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann MG, Estes MK. 1999. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science 286:287–290. 10.1126/science.286.5438.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington PR, Lindesmith L, Yount B, Moe CL, Baric RS. 2002. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J Virol 76:12335–12343. 10.1128/jvi.76.23.12335-12343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu W, Chen Y, Jiang X, Xia M, Yang Y, Tan M, Li X, Rao Z. 2015. A unique human norovirus lineage with a distinct HBGA binding interface. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005025. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh BK, Leuthold MM, Hansman GS. 2015. Human noroviruses' fondness for histo-blood group antigens. J Virol 89:2024–2040. 10.1128/JVI.02968-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansman GS, Biertumpfel C, Georgiev I, McLellan JS, Chen L, Zhou T, Katayama K, Kwong PD. 2011. Crystal structures of GII.10 and GII.12 norovirus protruding domains in complex with histo-blood group antigens reveal details for a potential site of vulnerability. J Virol 85:6687–6701. 10.1128/JVI.00246-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami K, Tenge VR, Karandikar UC, Lin SC, Ramani S, Ettayebi K, Crawford SE, Zeng XL, Neill FH, Ayyar BV, Katayama K, Graham DY, Bieberich E, Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2020. Bile acids and ceramide overcome the entry restriction for GII.3 human norovirus replication in human intestinal enteroids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:1700–1710. 10.1073/pnas.1910138117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estes MK, Ettayebi K, Tenge VR, Murakami K, Karandikar U, Lin SC, Ayyar BV, Cortes-Penfield NW, Haga K, Neill FH, Opekun AR, Broughman JR, Zeng XL, Blutt SE, Crawford SE, Ramani S, Graham DY, Atmar RL. 2019. Human norovirus cultivation in nontransformed stem cell-derived human intestinal enteroid cultures: success and challenges. Viruses 11:638. 10.3390/v11070638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ettayebi K, Crawford SE, Murakami K, Broughman JR, Karandikar U, Tenge VR, Neill FH, Blutt SE, Zeng XL, Qu L, Kou B, Opekun AR, Burrin D, Graham DY, Ramani S, Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2016. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science 353:1387–1393. 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilic T, Koromyslova A, Hansman GS. 2019. Structural basis for human norovirus capsid binding to bile acids. J Virol 93:e01581-18. 10.1128/JVI.01581-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh BK, Leuthold MM, Hansman GS. 2016. Structural constraints on human norovirus binding to histo-blood group antigens. mSphere 1:e00049-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00049-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang M, Fu M, Hu Q. 2021. Advances in human norovirus vaccine research. Vaccines (Basel) 9:732. 10.3390/vaccines9070732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mattison CP, Cardemil CV, Hall AJ. 2018. Progress on norovirus vaccine research: public health considerations and future directions. Expert Rev Vaccines 17:773–784. 10.1080/14760584.2018.1510327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netzler NE, Enosi Tuipulotu D, White PA. 2019. Norovirus antivirals: where are we now? Med Res Rev 39:860–886. 10.1002/med.21545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Loben Sels JM, Green KY. 2019. The antigenic topology of norovirus as defined by B and T cell epitope mapping: implications for universal vaccines and therapeutics. Viruses 11:432. 10.3390/v11050432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindesmith LC, McDaniel JR, Changela A, Verardi R, Kerr SA, Costantini V, Brewer-Jensen PD, Mallory ML, Voss WN, Boutz DR, Blazeck JJ, Ippolito GC, Vinje J, Kwong PD, Georgiou G, Baric RS. 2019. Sera antibody repertoire analyses reveal mechanisms of broad and pandemic strain neutralizing responses after human norovirus vaccination. Immunity 50:1530–1541.e8. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horm KM, D'Souza DH. 2011. Survival of human norovirus surrogates in milk, orange, and pomegranate juice, and juice blends at refrigeration (4 degrees C). Food Microbiol 28:1054–1061. 10.1016/j.fm.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su X, Sangster MY, D'Souza DH. 2010. In vitro effects of pomegranate juice and pomegranate polyphenols on foodborne viral surrogates. Foodborne Pathog Dis 7:1473–1479. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su X, Howell AB, D'Souza DH. 2010. Antiviral effects of cranberry juice and cranberry proanthocyanidins on foodborne viral surrogates—a time dependence study in vitro. Food Microbiol 27:985–991. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su X, Howell AB, D'Souza DH. 2010. The effect of cranberry juice and cranberry proanthocyanidins on the infectivity of human enteric viral surrogates. Food Microbiol 27:535–540. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehead K, McCue KA. 2010. Virucidal efficacy of disinfectant actives against feline calicivirus, a surrogate for norovirus, in a short contact time. Am J Infect Control 38:26–30. 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koromyslova A, Tripathi S, Morozov V, Schroten H, Hansman GS. 2017. Human norovirus inhibition by a human milk oligosaccharide. Virology 508:81–89. 10.1016/j.virol.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weichert S, Koromyslova A, Singh BK, Hansman S, Jennewein S, Schroten H, Hansman GS. 2016. Structural basis for norovirus inhibition by human milk oligosaccharides. J Virol 90:4843–4848. 10.1128/JVI.03223-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koromyslova AD, White PA, Hansman GS. 2015. Treatment of norovirus particles with citrate. Virology 485:199–204. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansman GS, Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, McLellan JS, Chuang GY, Georgiev I, Shimoike T, Katayama K, Bewley CA, Kwong PD. 2012. Structural basis for norovirus inhibition and fucose mimicry by citrate. J Virol 86:284–292. 10.1128/JVI.05909-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruoff K, Devant JM, Hansman G. 2022. Natural extracts, honey, and propolis as human norovirus inhibitors. Sci Rep 12:8116. 10.1038/s41598-022-11643-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jovcevska I, Muyldermans S. 2020. The therapeutic potential of nanobodies. BioDrugs 34:11–26. 10.1007/s40259-019-00392-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T, Cai H, Yao H, Zhou B, Zhang N, van Vlissingen MF, Kuiken T, Han W, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Gong Y, Zhao Y, Shen Q, Qin W, Tian XX, Peng C, Lai Y, Wang Y, Hutter CAJ, Kuo SM, Bao J, Liu C, Wang Y, Richard AS, Raoul H, Lan J, Seeger MA, Cong Y, Rockx B, Wong G, Bi Y, Lavillette D, Li D. 2021. A synthetic nanobody targeting RBD protects hamsters from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun 12:4635. 10.1038/s41467-021-24905-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Detalle L, Stohr T, Palomo C, Piedra PA, Gilbert BE, Mas V, Millar A, Power UF, Stortelers C, Allosery K, Melero JA, Depla E. 2016. Generation and characterization of ALX-0171, a potent novel therapeutic nanobody for the treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6–13. 10.1128/AAC.01802-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibanez LI, De Filette M, Hultberg A, Verrips T, Temperton N, Weiss RA, Vandevelde W, Schepens B, Vanlandschoot P, Saelens X. 2011. Nanobodies with in vitro neutralizing activity protect mice against H5N1 influenza virus infection. J Infect Dis 203:1063–1072. 10.1093/infdis/jiq168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koromyslova AD, Hansman GS. 2017. Nanobodies targeting norovirus capsid reveal functional epitopes and potential mechanisms of neutralization. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006636. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koromyslova AD, Hansman GS. 2015. Nanobody binding to a conserved epitope promotes norovirus particle disassembly. J Virol 89:2718–2730. 10.1128/JVI.03176-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koromyslova AD, Devant JM, Kilic T, Sabin CD, Malak V, Hansman GS. 2020. Nanobody-mediated neutralization reveals an Achilles heel for norovirus. J Virol 94:e00660-20. 10.1128/JVI.00660-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruoff K, Kilic T, Devant J, Koromyslova A, Ringel A, Hempelmann A, Geiss C, Graf J, Haas M, Roggenbach I, Hansman G. 2019. Structural basis of nanobodies targeting the prototype norovirus. J Virol 93:e02005-18. 10.1128/JVI.02005-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansman GS, Natori K, Shirato-Horikoshi H, Ogawa S, Oka T, Katayama K, Tanaka T, Miyoshi T, Sakae K, Kobayashi S, Shinohara M, Uchida K, Sakurai N, Shinozaki K, Okada M, Seto Y, Kamata K, Nagata N, Tanaka K, Miyamura T, Takeda N. 2006. Genetic and antigenic diversity among noroviruses. J Gen Virol 87:909–919. 10.1099/vir.0.81532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindesmith LC, Mallory ML, Debbink K, Donaldson EF, Brewer-Jensen PD, Swann EW, Sheahan TP, Graham RL, Beltramello M, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2018. Conformational occlusion of blockade antibody epitopes, a novel mechanism of GII.4 human norovirus immune evasion. mSphere 3:e00518-17. 10.1128/mSphere.00518-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindesmith LC, Ferris MT, Mullan CW, Ferreira J, Debbink K, Swanstrom J, Richardson C, Goodwin RR, Baehner F, Mendelman PM, Bargatze RF, Baric RS. 2015. Broad blockade antibody responses in human volunteers after immunization with a multivalent norovirus VLP candidate vaccine: immunological analyses from a phase I clinical trial. PLoS Med 12:e1001807. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doerflinger SY, Tabatabai J, Schnitzler P, Farah C, Rameil S, Sander P, Koromyslova A, Hansman GS. 2016. Development of a nanobody-based lateral flow immunoassay for detection of human norovirus. mSphere 1:e00219-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00219-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh BK, Koromyslova A, Hefele L, Gurth C, Hansman GS. 2015. Structural evolution of the emerging 2014/15 GII.17 noroviruses. J Virol 90:2710–2715. 10.1128/JVI.03119-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koromyslova AD, Morozov VA, Hefele L, Hansman GS. 2019. Human norovirus neutralized by a monoclonal antibody targeting the histo-blood group antigen pocket. J Virol 93:e02174-18. 10.1128/JVI.02174-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai YC, Xia M, Huang Q, Tan M, Qin L, Zhuang YL, Long Y, Li JD, Jiang X, Zhang XF. 2017. Characterization of antigenic relatedness between GII.4 and GII.17 noroviruses by use of serum samples from norovirus-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol 55:3366–3373. 10.1128/JCM.00865-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang XF, Huang Q, Long Y, Jiang X, Zhang T, Tan M, Zhang QL, Huang ZY, Li YH, Ding YQ, Hu GF, Tang S, Dai YC. 2015. An outbreak caused by GII.17 norovirus with a wide spectrum of HBGA-associated susceptibility. Sci Rep 5:17687. 10.1038/srep17687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang XF, Tan M, Chhabra M, Dai YC, Meller J, Jiang X. 2013. Inhibition of histo-blood group antigen binding as a novel strategy to block norovirus infections. PLoS One 8:e69379. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Tan M, Xia M, Hao N, Zhang XC, Huang P, Jiang X, Li X, Rao Z. 2011. Crystallography of a Lewis-binding norovirus, elucidation of strain-specificity to the polymorphic human histo-blood group antigens. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002152. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doerflinger SY, Weichert S, Koromyslova A, Chan M, Schwerk C, Adam R, Jennewein S, Hansman GS, Schroten H. 2017. Human norovirus evolution in a chronically infected host. mSphere 2:e00352-16. 10.1128/mSphere.00352-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Costantini V, Beltramello M, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Lanzavecchia A, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2013. Emergence of new pandemic GII.4 Sydney norovirus strain correlates with escape from herd immunity. J Infect Dis 208:1877–1887. 10.1093/infdis/jit370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindesmith LC, Debbink K, Swanstrom J, Vinje J, Costantini V, Baric RS, Donaldson EF. 2012. Monoclonal antibody-based antigenic mapping of norovirus GII.4–2002. J Virol 86:873–883. 10.1128/JVI.06200-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Lobue AD, Cannon JL, Zheng DP, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2008. Mechanisms of GII.4 norovirus persistence in human populations. PLoS Med 5:e31. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rockx BH, Vennema H, Hoebe CJ, Duizer E, Koopmans MP. 2005. Association of histo-blood group antigens and susceptibility to norovirus infections. J Infect Dis 191:749–754. 10.1086/427779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan M, Hegde RS, Jiang X. 2004. The P domain of norovirus capsid protein forms dimer and binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J Virol 78:6233–6242. 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6233-6242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harrington PR, Vinje J, Moe CL, Baric RS. 2004. Norovirus capture with histo-blood group antigens reveals novel virus-ligand interactions. J Virol 78:3035–3045. 10.1128/jvi.78.6.3035-3045.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan M, Huang P, Meller J, Zhong W, Farkas T, Jiang X. 2003. Mutations within the P2 domain of norovirus capsid affect binding to human histo-blood group antigens: evidence for a binding pocket. J Virol 77:12562–12571. 10.1128/jvi.77.23.12562-12571.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Jiang X, Lindblad L, Stewart P, LePendu J, Baric R. 2003. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med 9:548–553. 10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang P, Farkas T, Marionneau S, Zhong W, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Morrow AL, Altaye M, Pickering LK, Newburg DS, LePendu J, Jiang X. 2003. Noroviruses bind to human ABO, Lewis, and secretor histo-blood group antigens: identification of 4 distinct strain-specific patterns. J Infect Dis 188:19–31. 10.1086/375742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvarado G, Salmen W, Ettayebi K, Hu L, Sankaran B, Estes MK, Venkataram Prasad BV, Crowe JE, Jr. 2021. Broadly cross-reactive human antibodies that inhibit genogroup I and II noroviruses. Nat Commun 12:4320. 10.1038/s41467-021-24649-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansman GS, Taylor DW, McLellan JS, Smith TJ, Georgiev I, Tame JR, Park SY, Yamazaki M, Gondaira F, Miki M, Katayama K, Murata K, Kwong PD. 2012. Structural basis for broad detection of genogroup II noroviruses by a monoclonal antibody that binds to a site occluded in the viral particle. J Virol 86:3635–3646. 10.1128/JVI.06868-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schroten H, Hanisch FG, Hansman GS. 2016. Human norovirus interactions with histo-blood group antigens and human milk oligosaccharides. J Virol 90:5855–5859. 10.1128/JVI.00317-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alvarado G, Ettayebi K, Atmar RL, Bombardi RG, Kose N, Estes MK, Crowe JE, Jr. 2018. Human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize pandemic GII.4 noroviruses. Gastroenterology 155:1898–1907. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parra GI, Bok K, Taylor R, Haynes JR, Sosnovtsev SV, Richardson C, Green KY. 2012. Immunogenicity and specificity of norovirus consensus GII.4 virus-like particles in monovalent and bivalent vaccine formulations. Vaccine 30:3580–3586. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hansman GS, Doan LT, Kguyen TA, Okitsu S, Katayama K, Ogawa S, Natori K, Takeda N, Kato Y, Nishio O, Noda M, Ushijima H. 2004. Detection of norovirus and sapovirus infection among children with gastroenteritis in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Arch Virol 149:1673–1688. 10.1007/s00705-004-0345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kabsch W. 1993. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr 26:795–800. 10.1107/S0021889893005588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40:658–674. 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morris AL, MacArthur MW, Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. 1992. Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins 12:345–364. 10.1002/prot.340120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 2010. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:12–21. 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2007. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372:774–797. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.