Abstract

Determination of the solution structure of the duplex d(GCAAGTC(HE)AAAACG)·d(CGTTTTAGACTTGC) containing a 3-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2′-deoxyuridine·deoxyadenine (HE·A) base pair is reported. The three-dimensional solution structure, determined starting from 512 models via restrained molecular mechanics using inter-proton distances and torsion angles, converged to two final families of structures. For both families the HE and the opposite A residues are intrahelical and in the anti conformation. The hydroxyethyl chain lies close to the helix axis and for one family the hydroxyl group is above the HE·A plane and in the other case it is below. These two models were used to start molecular dynamic calculations with explicit solvent to explore the hydrogen bonding possibilities of the HE·A base pair. The dynamics calculations converge finally to one model structure in which two hydrogen bonds are formed. The first is formed all the time and is between HEO4 and the amino group of A, and the second, an intermittent one, is between the hydroxyl group and the N1 of A. When this second hydrogen bond is not formed a weak interaction CH···N is possible between HEC7H2 and N1A21. All the best structures show an increase in the C1′–C1′ distance relative to a Watson–Crick base pair.

INTRODUCTION

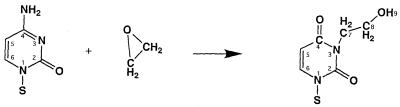

Ethylene oxide belongs to the class of aliphatic epoxides that are highly reactive compounds known to be effective mutagens and carcinogens (1,2). Ethylene oxide is widely used as an intermediate in the chemical industry and as a fumigant and sterilizing agent of food and medical products. It is also produced metabolically from ethylene in cigarette smoke and by the combustion of organic compounds. Ethylene oxide has been shown to be carcinogenic in rodents and genotoxic in humans. It has been suggested that ethylene oxide may be involved in the etiology of human cancer (3,4). The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified ethylene oxide as a probable human carcinogen (5). Numerous studies have demonstrated that ethylene oxide causes mutations (6–11), sister chromatid exchanges (12) and chromosomal aberrations or damage (13) in a number of biological systems, including man.

Ethylene oxide is a direct acting alkylating agent. It reacts with DNA by an SN2 mechanism which favors alkylation at strongly nucleophilic endocyclic nitrogen atoms (2). It has been shown that ethylene oxide reacts with dC at the N3 position, which, after spontaneous deamination, produces the potentially mutagenic lesion 3-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2′-deoxyuridine (HE), shown in Figure 1. This modified nucleoside is chemically stable in DNA (14) and no repair activity has yet been found in prokaryotes or eukaryotes. In vitro it has been demonstrated (15) that the HE lesion blocks DNA replication by the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli polymerase I and bacteriophage T7 polymerase 3′ to HE and after incorporation of a nucleotide opposite the lesion. When the HE is bypassed, and in the absence of proofreading, both dA and dT were observed to be incorporated opposite the lesion (15). Since HE is derived from dC, this result suggests that HE induces G·C→A·T and G·C→T·A mutations.

Figure 1.

Formation of the 3-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2′-deoxyuridine base.

In this article we report NMR, molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics studies of a duplex containing the HE lesion opposite adenine. There has been no structural study on this modified base and we do not know if the HE·A base pair is stacked in the duplex or flipped out from it. It is to our knowledge the first time that a modified base with a bulky chain has been studied in an oligonucleotide context by NMR. The oligonucleotide sequence is the 14mer 5′-GCAAGTC(HE)AAAACG, where the sequence of the central 11 nt in bold corresponds to the sequence utilized in a previous in vitro polymerase study (15). The correlation between the structures of lesions in DNA and the corresponding properties of these lesions in in vitro polymerase studies will help us to understand the mutagenic potential of lesions such as HE and, further, to determine what factors influence base selection by DNA polymerase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide synthesis

Oligonucleotides were synthesized by standard solid phase methods. The 3-(2-acetoxyethyl)-5′-O-4-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2′-deoxyuridine-3′-(2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite) precursor for introduction of the HE lesion into the synthetic oligonucleotides was prepared as described previously (15). Oligonucleotides were purified by HPLC. The composition of the oligonucleotides was confirmed by HPLC analysis of the deoxynucleosides generated by enzymatic hydrolysis.

NMR spectroscopy

After mixing the two strands, the oligonucleotides were heated to 80°C and then slowly cooled down to form the duplex. The sequence was: 5′-G1 C2 A3 A4 G5 T6 C7 HE8 A9 A10 A11 A12 C13 G14-3′, 3′-C28 G27 T26 T25 C24 A23 G22 A21 T20 T19 T18 T17 G16 C15-5′. The duplex, 2 mM in single strand concentration, was dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer, 50 mM NaCl and 0.2 mM EDTA. As internal reference the 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionate (TSP) peak at 0 p.p.m. was used. NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker DRX500 or DRX600 spectrometers. Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) and total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) spectra were recorded and treated as described previously (16,17). The mixing times of the NOESY spectra were 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105 and 400 ms in 2H2O and 250 ms in H2O. In 2H2O the residual water resonance was presaturated during the relaxation and mixing delays. Double quantum filtered two-dimensional correlated spectroscopy (DQF-COSY) spectra were recorded with time-proportional phase incrementation. A double quantum spectrum was recorded with an evolution time of 30 ms. One-dimensional 31P spectra were recorded between 3 and 35°C and two-dimensional HSQC (18) were recorded to allow resonance assignment. In H2O the water signal was suppressed with the WATERGATE sequence (19). The NMR distance constraints were obtained as described in earlier studies (16,20).

Molecular modeling

The initial model for the duplex was built in B-DNA form in accordance with NMR data. The charge distribution of the HE base was computed with the program Gaussian 94 and fitted with the program RESP for compatibility with AMBER. A set of 2 × 256 conformations was generated by varying the angles in the CH2-CH2-OH chain and the C1′–C1′ distance of the HE·A base pair. Each structure was minimized with the SANDER module of AMBER, using the Cornell et al. force field (21) in two phases. Three types of constraints were applied during the first minimizations: torsion angles, NMR distances and weak reinforcements (5 kcal mol–1 Å–2) of the hydrogen bonds of terminal base pairs to avoid end fraying. The torsion angle constraints were applied on δ angles (C5′-C4′-C3′-O3′) with a value of 144° and a constraint force of 50 kcal mol–1 deg–2, forcing all the sugar puckers into a C2′-endo conformation, as observed by NMR. All internucleotide NMR distance constraints were applied with a constant force of 5 kcal mol–1 Å–2. The second minimizations were performed for all the systems without any constraints in order to relax the obtained conformations. All minimizations were stopped when the root mean square (r.m.s.) energy gradient was <0.1 kcal mol–1 Å–1. The best structures in terms of energy, fitted with the NMR distances and observed hydrogen bonds, were hydrated with TIP/3P water molecules and Na+ counterions were positioned with the LEaP AMBER module to obtain electroneutral hydrated models. The size of the water box is 43.5 × 42.2 × 73 Å and contains 2754 water molecules. They were used to start molecular dynamics simulations with explicit water molecules as described previously (22). The particle mesh Ewald method was applied to treat long-range interactions and periodic boundary conditions. The dynamics protocol consists of two steps. First, after minimization of the hydrated structure, the system was prepared during 40 ps following the protocol described previously (23). Then 1 ns of molecular dynamics production on each system was performed. After ∼200 ps the system is fully equilibrated. Only the final 500 ps of the production phase were used for analysis. During this production phase, the same three types of constraints described above for the first minimization stage were applied. The quality of the molecular dynamics runs was judged by first following the evolution of the energetic terms, temperature and pressure. Secondly, the stability of the structure and the agreement with the NMR data were analyzed by following the r.m.s. parameter during the calculations. Whatever the starting structure, the r.m.s. fluctuates around 1.7 ± 0.3 Å and the curve remains smooth during the whole calculation. The fit between the NMR distance constraints and the corresponding distances during the MD runs were in good agreement. It was found to be ∼0.87 ± 0.13 for the five central base pairs and ∼2.49 ± 0.22 for the whole duplex. The conformations generated were analyzed and displayed on SGI workstations using the programs OCL (24) and MORCAD (25). Figures in this paper were generated with MORCAD (25) or MOLMOL (26).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have recorded one-dimensional proton spectra between pH 4.5 and 9 for the HE·A-containing 14mer duplex and we did not observe any significant changes in the spectra. This indicates that there is no pH-dependent conformational transition.

NMR results

Figure 2 shows the H8/H6–H1′/H5 region of a NOESY spectrum recorded at 20°C with a mixing time of 110 ms. The connectivities correspond to those of a right-handed B-DNA helix and can be followed without any interruption for both strands. For the mispaired base pair we observe A9H8–HE8H1′ and HE8H6–C7H1′ connectivities for the first strand. The inter-residue interactions are observed at the T20-A21-G22 steps for the second strand. The assignment is confirmed in the H8/H6–H2′/H2″ region shown in Figure 3. The H2 resonances of the adenines were identified in Figure 2 and in spectra in H2O. The A21H2 proton at 7.70 p.p.m., which overlaps with A12H2, exhibits three cross-peaks, one with its own H1′, the second with the A9H1′ and a third one, which is weak, with the H5 of HE8. Note that the expected cross-peak with the H1′ of G22 is missing. These interactions are confirmed in a spectrum at 12°C where A12H2 and A21H2 are well resolved (Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

Expanded contour plot of the H6/H8–H1′/H5 region of the NOESY spectrum (110 ms mixing time) in 2H2O, 20°C. Cross-peaks marked with an X correspond to H6–H5 interactions. Peaks labeled A–F correspond to the H8/H6(n)–H5(n + 1) nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs). The chemical shifts of the H2 resonances are shown on the upper horizontal axis.

Figure 3.

The different patterns of hydrogen bonds for the HE·A base pair. (A and B) One hydrogen bond after minimization. (C–E) Two possible hydrogen bonds during the molecular dynamics calculations.

We have identified all the cross-peaks expected for a B-DNA structure in the H8/H6–H2′/H2″ region shown in Figure 3. The assignment of the methyl resonances was obtained from a double quantum (DQ) spectrum without ambiguity. At the mispair site, the intra- and inter-nucleotide interactions at the T20-A21-G22 and C7-HE8-A9 steps are well resolved. These observations demonstrate that the HE8 and A21 bases are stacked into the helix, which adopts a global B-DNA structure.

The distinction between the H2′ and H2″ protons was obtained by analyzing the H1′–H2′/H2″ region of a DQF-COSY spectrum (Fig. S2). The relative populations of S type sugar conformations was estimated from the sum Σ1′ = J1′2′ + J1′2′ according to van Wijk et al. (27). In this duplex all the sugar puckers of non-terminal bases were found to be predominantly of the S type (70–90%), but for the deoxyribose of A21 we observed a lower S type population of ∼60%.

The complete assignment of the H3′ and H4′ resonances was obtained from analysis of NOESY, TOCSY and DQ spectra. We were able to identify the H5′ and H5″ protons but we could not make a relative assignment. At this stage, three resonances, at 3.03, 3.15 and 3.35 p.p.m., shown in Figure 3, remain unassigned. We should note that the chemical shifts of these protons are unusual. The resonance at 3.03 p.p.m. corresponds to two protons and the two others to one proton. As we have already identified all the non-exchangeable protons of the oligonucleotide except for those of the CH2-CH2-OH chain of HE, the three unassigned resonances must belong to these. The CH2-CH2 protons of HE principally show interactions with the H2 protons of A9 and A21. It is clear, at lower mixing times, that those with A21H2 are strongest. In a NOESY spectrum recorded with a 50 ms mixing time (not shown), the peak at 3.03 p.p.m. shows weak cross-peaks with the H5 and H1′ protons of HE and a stronger one with the H1′ of A21. For the two other protons at 3.15 and 3.35 p.p.m. we observe the same weak cross-peaks but with different intensities compared with that from the resonance at 3.03 p.p.m. They are stronger with H5 and H1′ of HE and weaker with A21H1′. At low mixing times we do not observe any other interactions.

One- and two-dimensional 31P spectra have been recorded to investigate the backbone chain of the duplex. We observed only a small chemical shift dispersion, which is typical for the BI conformation (Fig. S3). No 31P resonance was shifted significantly downfield, as would be expected for the BII conformation.

Figure 4 shows two regions of the 250 ms NOESY spectrum recorded in H2O at 5°C and pH 6.0. In the lower part we can follow the expected imino–imino connectivities. There is a break at the HE·A base pair, which has no imino proton. The imino proton of G22 shows interactions with the H2 of A23 and A21, demonstrating that the adenines are stacked inside the helix. The two imino protons on either side of the HE (G22 and T20) show interactions with the CH2-CH2-OH resonances corresponding to the chain of the modified base. Those at 3.03 and 3.15 p.p.m. slightly overlap but can be individually viewed in the submatrix columm. Clearly, the cross-peaks with the two protons at 3.0 p.p.m. are strongest. We have not been able to identify the amino group protons of A21, whereas they are normally observed for an A·T base pair. Either these protons exchange rapidly with H2O or rotation about the C-N bond is more rapid than for an A·T base pair, suggesting that possible hydrogen bonding is weaker and/or that the A21·HE8 base pair is more flexible.

Figure 4.

Expanded contour plot of the NOESY spectrum (250 ms mixing time) in H2O, 5°C and pH 6.0. The lower part shows the interactions between the imino protons. The upper part shows the interactions between the imino protons and the amino-CH3 region. The two protons of the amino groups of the cytosines and adenines are connected by a continuous line. Cross-peaks marked with an X correspond to the interaction between a thymine imino proton and the H2 of the adenine of the base pair. Cross-peaks labeled A–F correspond to the G imino–H5, on the opposite strand, interaction. Peaks H and G correspond to the T imino proton with its own CH3 group for T20 and T6, respectively. The cross-peaks in boxes are with the HE side chain.

We observe that the HE·A base pair stacks inside the helix, which is globally in the B-form. From the build-up curves it is clear that all the bases are in the anti conformation and all non-terminal sugar puckers are predominantly C2′-endo. This latter result was confirmed by analyzing DQF-COSY spectra. The two base pairs C7·G22 and A9·T20 on either side of the HE·A mispair show no sign of important destabilization. The imino protons of both G22 and T20 were identified in H2O, demonstrating that the base pairs are formed. We have been able to identify the protons of the CH2-CH2 chain of the modified base and these protons lie near the center of the helix. The non-exchangeable protons of the HE hydroxyethyl group show interactions with others which are near the center of the helix, including the H2 protons of A9 and A21 and the imino protons of T20 and G22. We did not observe the hydroxyl proton of the HE residue due to greater solvent accessibility or more frequent exchange with the solvent compared with the imino and amino protons of the Watson–Crick base pairs. Close examination of all the interactions with the HE side chain in short mixing time experiments shows that it is impossible to fit all the data to a single or even a close family of conformations. Certain interactions fit a structure with the side chain above the HE·A base plane while others fit better with it below. The transition from one to the other only requires rotation about the C8-C7 bond. While the build-up curves have been determined they cannot be reliably interpreted as distances and relative populations. This interconversion is fast on the proton chemical shift time scale and the effective correlation time for the observed interactions may be significantly different from those between Watson–Crick bases. Thus we can only tentatively assign the peak at 3.03 p.p.m. to the C8H2 protons. This virtually unhindered interconversion is observed in the simulations (see below).

Model building

We have measured 326 inter-proton distances. Some of these were redundant, confirming the predominantly C2′-endo sugar conformations, and were thus applied as a single δ angle constraint (see Materials and Methods), and some had an uncertainty of >15%. Thus we retained only 225 inter-proton distances for the model building. As we have determined the position of the modified base within the helix, the remaining question is the conformation of the CH2-CH2-OH chain inside the helix. The HE·A base pair was constructed by fitting the aromatic ring of the modified base on that of a thymine of a T8·A21 base pair incorporated in the duplex. Then, the geometry of the HE·A base pair was optimized by adjusting the distance between A21 and HE8 to reduce steric clashes and to be in better agreement with the NMR results. From these data we observed that some inter-residue distances which involve the HE·A base pair were longer compared to that of the standard B-DNA form of the same sequence with a T·A base pair, particularly those concerning the C7·G22 and HE·A base pairs. For example, A9H8–HE8H2′, G22H8–A21H2′ and G22H8–A21H2″ were calculated as 4.35, 4.40 and 2.85 Å, respectively. These values can be compared with those measured in B-DNA form DNA of the same sequence with a central T·A base pair, which were 3.52, 3.48 and 2.28 Å, respectively. The increase in the C1′–C1′ distance of the HE·A base pair, shown in Figure 5A and B, from 10.7 Å (T·A base pair in B-DNA) to 12.2 Å at the mispair site improves the fit with the NMR distances, as these distances became 4.20, 4.05 and 2.80 Å, respectively. Another argument for increasing the C1′–C1′ distance of the HE·A base pair is that it reduces clashes which occur between the CH2-CH2-OH chain and the adenine in front of the modified base. Finally, if we minimized a structure without having adjusted the C1′–C1′ distance, it spontaneously occured during the minimization steps. A set of 256 structures was generated by varying the three torsion angles φ1, φ2 and φ3 of the side chain as shown in Figure 5B. The angles φ1 and φ2 were varied in steps of 45°, whereas a step of 90° was chosen for the third angle to limit the number of conformations to 256. The inital conformation of the chain was for torsion angles φ1 = φ2 = φ3 = 180°. Then φ1 was first varied, followed by φ2 and, finally, φ3. In this way the CH2-CH2-OH chain was forced to explore all the available space inside the helix (see Fig. S4). This systematic approach was prefered to an energetic exploration by simulated annealing steps, which was also performed in parallel but which gave less clear results in this case in our opinion. The 256 resulting constructed structures were next minimized. The best families of structures were then first analyzed by considering both the NMR distance violations and the global energy. The best structures belong to the families which correspond to angles 315° ≤ φ1 ≤ 45°, as shown when we analyze the fit of the structures for all the 225 NMR distances as shown in Figure 5C. It should be noted that this fitted curve correlates well with the same analysis when we only considered the distances (∼100) which involve the five central base pairs of the duplex. This demonstrates that the structures are sensitive to the position of the CH2-CH2-OH chain of the HE base. In terms of energy, there are no major significant differences between the 256 structures.

Figure 5.

(A) HE·A base pair superimposed on that of a T·A base pair, with a C1′–C1′ distance of 10.7 Å. (B) HE·A base pair with the C1′–C1′ distance increased to 12.2 Å. (C) Empty circles, variation of the global fit calculated from the 226 NMR distances as a function of the structure number; filled circles, variation of the fit calculated with the NMR distances involving only the five central base pairs of the duplex.

We have no NMR evidence for the formation of a hydrogen bond between HE8 and another base as we do not observe the HE8H9 proton in any of our spectra. Nevertheless, we observe that the bulky HE8 side chain lies in the center of the helix and that the HE8·A21 base pair is remarkably stable. It is, therefore, reasonable to search for a hydrogen bond between HE8 and a base on the opposite strand. There are many possibilities for the hydroxyl group of the HE residue to form a hydrogen bond. It could be with the adenine in front of the base, A21, or with different acceptors and donors for hydrogen bond formation with the adjacent base pairs. However, when we analyzed the hydrogen bond possibilities for the best structures retained above, we could eliminate many of these possibilities. We know that the two adjacent C7·G22 and A9·T20 base pairs are well formed in Watson–Crick geometry and also that there is a common point between all the best minimized structures, which is that a hydrogen bond between N1 of A21 and H9 of the HE base is formed. There are two ways to form this hydrogen bond, either the hydroxyl group is over the plane of the HE·A base pair or it is below. Two representative structures are shown in Figure 6 and the respective base pairings are represented in Figure 7A and B. It should be noted that these structures remain globally close to B-DNA.

Figure 6.

Two stereoscopic views corresponding to the best structures which were used to initiate the molecular dynamic simulations: (A) with the HE side chain above the plane of the base pair and (B) below it.

Figure 7.

The different patterns of hydrogen bonds for the HE·A base pair. (A and B) One hydrogen bond after minimization. (C–E) Two possible hydrogen bonds during the molecular dynamics calculations.

Molecular dynamics simulations

We have performed molecular dynamics simulations with explicit water molecules on each of these two systems to test the stability of the selected structures and to explore the conformational space, particularly concerning the possibilities of base pairing between HE and A. A molecular dynamics simulation was calculated with the NMR constraints starting with an A-DNA structure. During the calculations, the A-DNA helix rapidly changed and after ∼50 ps adopted the B-DNA form. Thus the starting structures were those shown in Figure 6. The results are very similar whatever the starting structures, and the dynamic calculations converge to the same final structure.

The variations in the C1′–C1′ distances for the HE·A mispair and an A·T base pair are shown in Figure 8A. As previously observed from the NMR results and during the minimization step, the C1′–C1′ distance of the HE·A base pair is longer compared with that of a Watson–Crick base pair. The C1′–C1′ distance remains ∼13 Å during all the calculations. It is larger compared with that measured for the starting minimized structures (∼12.5 Å), which are shown in Figure 7A and B. The corresponding fluctuations of the A21N1···HE8H9 hydrogen bond are shown in Figure 8B. We observe that they are important between 6 and 1.8 Å, which correspond to different states for the hydrogen bond which could be strong (∼2 Å), weak (∼3 Å) or absent (>4 Å), where the populations are shown in Figure 8C. Futhermore, there is no correlation between formation or not of the hydrogen bond and the C1′–C1′ distance of the HE·A base pair. We have analyzed these different populations and they in fact correspond to the same conformation for the HE·A base pair. Three representative examples are shown in Figure 7C–E. Formation or not of the A21N1···HE8H9 hydrogen bond is mostly due to rotation of the OH group of the CH2-CH2-OH chain of the modified base. Furthermore, we observe formation of a second hydrogen bond between the amino group of A and the O4 of HE, as shown in Figure 7C–E. This hydrogen bond is formed during all the simulations, as shown in Figure 8D, independently of formation of the A21N1···HE8H9 hydrogen bond. The molecular dynamics calculations also revealed the possibility of a third interaction between A21N1 and HE8C7H2, as presented in Figure 8E, which if real could lead to the formation of a weak hydrogen bond (between a non-acidic proton and a potential hydrogen bond acceptor) that could stabilize the base pair. We have no direct evidence for this and so it should be treated with caution, but it could explain the chemical shift non-equivalence of the CH2 protons. Of course, this third possibility is only possible if the A21N1···HE8H9 hydrogen bond is not formed as presented in Figure 7C and D.

Figure 8.

(A) Evolution over time of the C1′–C1′ distance during the molecular dynamics simulations for the HE·A base pair (dots) and for an A·T base pair (bold). (B) Evolution over time during molecular dynamics simulations of the A21N1–HE8H9 distance. The corresponding populations are plotted in (C). (D) Time evolution during molecular dynamics simulations of the A21NH2–HE8O4 distance. Both protons of the amino group are plotted. (E) Time evolution during molecular dynamics simulations of the A21N1–HE8C7H2 distance. Both H71 and H72 are plotted.

The NMR results did not give us direct information about the possible hydrogen bonds between the two bases but it is clear that the C1′–C1′ distance has to be longer than in a Watson–Crick base pair for the best fit. The results obtained during the molecular dynamics simulations are in very good agreement with the NMR data and are particularly informative. Despite the presence of a bulky CH2-CH2-OH group, the HE·A base pair is very stable in solution because it can be formed with two hydrogen bonds. A strong one, A21NH2···HE8O4, which is always formed, and a second one which corresponds either to A21N1···HE8H9 or the weak interaction A21N1···HE8C7H2, depending of the rotation of the OH group. We could not identify by NMR the amino group of A21, but formation of this hydrogen bond is not inconsistent with our results since the rotation of the amino group could be more rapid than for an A·T base pair or proton exchange with the solvent could be more rapid.

CONCLUSION

The HE lesion in DNA, derived from the reaction of the carcinogen ethylene oxide with a cytosine residue, is a premutagenic lesion which can result in a base substitution mutation (15). The most frequent base inserted opposite HE by DNA polymerase is adenine. In this study we have investigated the structure of an oligonucleotide duplex containing the mutagenic intermediate HE·A base pair. Surprisingly, the presence of the HE·A base pair does not significantly perturb the conformation or stability of adjacent base pairs. The results of these studies indicate that the HE and A residues are intrahelical and that the helix is globally B-form. However, the C1′–C1′ distance between the HE and A residues is greater than observed for an unmodified A·T base pair and this generates a small bulge in the helix. A C1′–C1′ distance ≥12.5 Å has previously been observed for different purine·purine mismatches (16,17). A priori the presence of a bulky group on the coding face of a base could be expected to completely inhibit replication or incorporation by a polymerase. In part this is what is observed. However, incorporation of an adenine has been shown and our results explain this. The inherent flexibility of the DNA helix allows positioning of the bulky side chain close to the center of the helix. To our knowledge this is the first structure of this type to be observed. Our study also indicates that the HE·A base pair is stable and that two hydrogen bonds are probably formed, one between the O4 of HE and the amino group of A and the second between the N1 position of the adenine and the H9 or a CH2 group of HE, depending on the rotation of the hydroxyethyl group. The formation of such hydrogen bonds during DNA replication could stabilize the HE·A mispair, enhancing adenine incorporation and subsequent lesion bypass.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material including a table of chemical shifts is available at NAR Online.

PDB no. 1KXS

REFERENCES

- 1.Dellarco V.L., Generoso,W.M., Sega,G.A., Fowle,J.R.D. and Jacobson-Kram,D. (1990) Review of the mutagenicity of ethylene oxide. Environ. Mol. Mutagen., 16, 85–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ehrenberg L. and Hussain,S. (1981) Genetic toxicity of some important epoxides. Mutat. Res., 86, 1–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogstedt C., Aringer,L. and Gustavsson,A. (1986) Epidemiologic support for ethylene oxide as a cancer-causing agent. J. Am. Med. Assoc., 255, 1575–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stayner L., Steenland,K., Greife,A., Hornung,R., Hayes,R.B., Nowlin,S., Morawetz,J., Ringenburg,V., Elliot,L. and Halperin,W. (1993) Exposure-response analysis of cancer mortality in a cohort of workers exposed to ethylene oxide. Am. J. Epidemiol., 138, 787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (1985) IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans. Allyls Compounds, Aldehydes, Epoxides and Peroxides. Vol. 36. IARC, Lyon, France, pp. 189–226.

- 6.Embree J.W., Lyon,J.P. and Hine,C.H. (1977) The mutagenic potential of ethylene oxide using the dominant-lethal assay in rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 40, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahmy O.G. and Fahmy,M.J. (1970) Gene elimination in carcinogenesis: reinterpretation of the somatic mutation theory. Cancer Res., 30, 195–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Generoso W.M., Cain,K.T., Krishna,M., Sheu,C.W. and Gryder,R.M. (1980) Heritable translocation and dominant-lethal mutation induction with ethylene oxide in mice. Mutat. Res., 73, 133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolman A. and Naslund,M. (1983) Lack of additive effect in mutagenesis of E. coli by UV-light and ethylene oxide. Mol. Gen. Genet., 189, 222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rannug U., Gothe,R. and Wachtmeister,C.A. (1976) The mutagenicity of chloroethylene oxide, chloroacetaldehyde, 2-chloroethanol and chloroacetic acid, conceivable metabolites of vinyl chloride. Chem. Biol. Interact.,12, 251–263.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tates A.D., Grummt,T., Tornqvist,M., Farmer,P.B., van Dam,F.J., van Mossel,H., Schoemaker,H.M., Osterman-Golkar,S., Uebel,C., Tang,Y.S., Zwinderman,A.H., Natarajan,A.T. and Ehrenberg,L. (1991) Biological and chemical monitoring of occupational exposure to ethylene oxide. Mutat. Res., 250, 483–497. [Erratum (1992) Mutat. Res., 280, 73] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelsey K.T., Wiencke,J.K., Eisen,E.A., Lynch,D.W., Lewis,T.R. and Little,J.B. (1988) Persistently elevated sister chromatid exchanges in ethylene oxide-exposed primates: the role of a subpopulation of high frequency cells. Cancer Res., 48, 5045–5050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farooqi Z., Tornqvist,M., Ehrenberg,L. and Natarajan,A.T. (1993) Genotoxic effects of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide in mouse bone marrow cells. Mutat. Res., 288, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F., Segal,A. and Solomon,J.J. (1992) In vitro reaction of ethylene oxide with DNA and characterization of DNA adducts. Chem. Biol. Interact., 83, 35–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhanot O.S., Singh,U.S. and Solomon,J.J. (1994) The role of 3-hydroxyethyldeoxyuridine in mutagenesis by ethylene oxide. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 30056–30064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faibis V., Cognet,J.A., Boulard,Y., Sowers,L.C. and Fazakerley,G.V. (1996) Solution structure of two mismatches G.G and I.I in the K-ras gene context by nuclear magnetic resonance and molecular dynamics. Biochemistry, 35, 14452–14464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulard Y., Cognet,J.A.H. and Fazakerley,G.V. (1997) Solution structure as a function of pH of two central mismatches, C·T and C·C, in the 29 to 39 K-ras gene sequence, by nuclear magnetic resonance and molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Biol., 268, 331–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenhausen G. and Ruben,D.J. (1980) Natural abundance nitrogen-15 NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett., 69, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piotto M., Saudek,V. and Sklénar,V. (1992) Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR, 2, 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuniasse P., Sowers,L.C., Eritja,R., Kaplan,B., Goodman,M.F., Cognet,J.A.H., Le Bret,M., Guschlbauer,W. and Fazakerley,G.V. (1987) An abasic site in DNA. Solution conformation determined by proton NMR and molecular mechanics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 8003–8022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornell W.D., Cieplak,P., Bayly,C.I., Gould,I.R., Merz,K.M., Ferguson,D.M., Spellmeyer,D.C., Fox,T., Caldwell,G.W. and Kollman,P.A. (1995) A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roll C., Ketterlé,C., Faibis,V., Fazakerley,G.V. and Boulard,Y. (1998) Conformations of nicked and gapped DNA structures by NMR and molecular dynamic simulations in water. Biochemistry, 37, 4059–4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ketterlé C., Gabarro-Arpa,J., Ouali,M., Bouziane,M., Auclair,C., Helissey,P., Giorgi-Renault,S. and Le Bret,M. (1996) Binding of Net-Fla, a netropsin-flavin hydrid molecule, to DNA: molecular mechanics and dynamics studies in vacuo and in water solution. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 13, 963–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabarro-Arpa J., Cognet,J.A.H.C. and Le Bret,M. (1992) Object Command Language: a formalism to build molecular models and to analyze structural parameters in macromolecules, with applications to nucleic acids. J. Mol. Graph., 10, 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bret M., Gabarro-Arpa,J., Gilbert,J.C. and Lemarechal,C. (1991) MORCAD, an object oriented molecular modelling package running on IBM/RS6000 and SGI 4Dxxx workstations. J. Chim. Phys., 88, 2489–2496. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koradi R., Billeter,M. and Wuthrich,K. (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph., 14, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Wijk J., Huckriede,B.D., Ippel,J.H. and Altona,C. (1992) In Lilley,D.M.J. and Dahlberg,J.E. (eds), Methods in Enzymology,DNA Structures 2a: Spectroscopic Methods. Academic Press, Orlando, FL, pp. 286–306. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.