Abstract

Suicide attempts among adolescents are common and can lead to death. The study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with suicide attempts among secondary school-going adolescents in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. The study used data from two repeated regional school-based student health surveys (RSHS), conducted in 2019 (Survey 1) and 2022 (Survey 2). Data were analyzed for secondary school students aged 13 to 17 years from four districts of the Kilimanjaro region. The study included 4188 secondary school-going adolescents: 3182 in Survey 1 and 1006 in Survey 2. The mean age in Survey 1 was 14 years and the median age in Survey 2 was 17 years (p < 0.001). The overall prevalence of suicide attempts was 3.3% (3.0% in Survey 1 and 4.2% in Survey 2). Female adolescents had higher odds of suicide attempts (aOR = 3.0, 95% CI 1.2–5.5), as did those who felt lonely (aOR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.0–3.6), had ever been worried (aOR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.0–3.5), or had ever been bullied (aOR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–4.1). Suicidal attempts are prevalent among secondary school-going adolescents in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. In-school programs should be established to prevent such attempts.

Keywords: suicide attempt, adolescents, global school-based student health survey, regional school-based student health survey, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

1. Introduction

Suicide among adolescents is a major public health concern worldwide [1]. It was the fourth leading cause of death among adolescents aged 15–19 years [2]. Each year, nearly 46,000 adolescents die by suicide [3]. However, 77% of all suicides among adolescents occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where most of the world’s population resides [4]. An increase in the mean suicide rate among adolescents 15–19 years has been observed at a rate of 7.4 per 100,000 [5]. Suicide behaviors include suicidal ideation (wanting to die by suicide), suicidal planning (preparing to die by suicide), suicidal attempt (making an attempt to die by suicide), and suicide itself (actually dying by suicide) [6]. Attempted suicide is a major risk factor for mortality caused by suicide in the general population, which has a negative impact on families, communities, and the entire country [7].

There are variations in suicide attempts across surveys in LMICs. For instance, the prevalence of suicide attempts was 16.6% in the 2015 Guatemala global school-based health survey (GSHS): 12.2% in boys and 20.2% in girls [8]. In South Africa, suicide attempts, suicide planning, and suicidal ideation have been reported at 3.2%, 5.8%, and 7.2%, respectively [9]. While in Malawi, a higher prevalence (12.9%) of suicide attempts among school-going adolescents was reported, with 7.2% of adolescents reporting one attempt and 5.9% of adolescents reporting making two or more attempts [10]. Few studies on adolescent suicide attempts in Tanzania show an increase in suicidal attempts from 11.1% to 24.8% [11,12] which has been linked to serious mental health crises and substance abuse. According to Tanzania’s 2014 GSHS report, 13.9% of students seriously considered suicide, 9.5% of students made a suicide plan, and 11.5% of students reported attempted suicide [13]. The feeling of loneliness, bullying, food insecurity, substance abuse, female sex, physical attack, and sexual intercourse are some of the drivers of suicidal attempts among in-school adolescents [8,14,15,16]. Physical or sexual abuse, stressful life events, mood disorders, anxiety, interpersonal violence, mental problems, low social economic status, having no close friends, and family suicide history are among the psychosocial factors that influence suicidal attempts in adolescents [16,17].

The GSHS conducted to measure risk behaviors helps in determining the burden of suicidal attempts among secondary school adolescents, which in turn informs programs aimed at improving adolescent health [13]. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of suicidal attempts and examine associated factors among secondary school-going adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Settings

This was a cross-sectional study using secondary data from two repeated cross-sectional surveys in 2019 and 2022 years from the regional school health survey (RSHS) in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. The surveys were conducted by the Institute of Public Health (IPH) of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (KCMUCo) as part of a health promotion training activity for the Doctor of Medicine students at the college. The study was conducted in four districts of Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania, that is the Moshi municipality, Moshi rural, Hai, and Siha districts. Kilimanjaro is one of Tanzania’s 30 administrative regions, with an area of 1831.32 km2. Kilimanjaro has a population of 1.8 million people with 13.5% and 11.1% of them being adolescents aged 10–14 and 15–19 years, respectively [18]. Kilimanjaro has a relatively large number of secondary schools compared to other regions in Tanzania, with a total of 349 mixed and single-sex, day, and boarding schools. However, the population density of students per school is low, with an average of 413.2 students [19]. The methodology of the 2019 survey has also been described elsewhere [20].

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

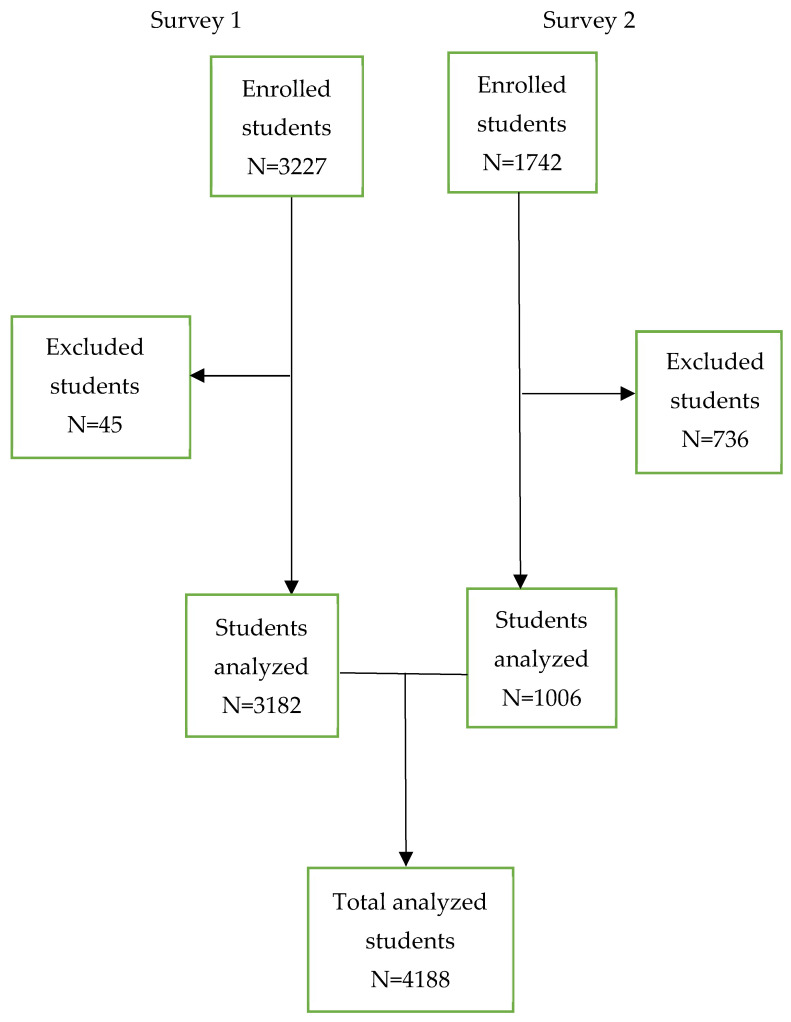

The study population consisted of adolescents attending public secondary schools in the Kilimanjaro region who were present at school on the day of data collection. Adolescents with missing age or sex information and those with incomplete responses to the suicide questions were excluded from the analysis. Of the 4969 secondary school-going adolescents who participated in the survey, 4188 (84%) (3182 from Survey 1 and 1006 from Survey 2), aged between 13 and 17 years, were eligible and included in this analysis (Figure 1). A multistage sampling technique was used to select schools and students. In the first stage, four districts were purposely selected to ensure the representativeness of both rural and urban areas. In the second stage, a random selection of public secondary schools was made from all available schools in each district. In Survey 1, only form one students were selected, while in Survey 2, only form four students were selected to assess changes in adolescent risk behaviors three years after the initial survey in 2019 (The education system in Tanzania is based on a 7-4-2-3 model, which consists of 7 years of primary education, 4 years of secondary education (ordinary level), 2 years of advanced secondary education (advanced level), and 3 or more years of tertiary education). All available students were included in the interviews, which were conducted at the class level.

Figure 1.

A flow diagram of enrolled and analyzed participants in the two surveys.

2.3. Data Collection

Data for Surveys 1 and 2 were collected using a self-administered questionnaire from the RSHS. The survey has been standardized to assess risk behaviors among school-going students in Tanzania and was administered in the Kiswahili language. The RSHS was adopted from the GSHS developed by WHO/CDC to help countries measure and assess behavioral risk and protective factors among students aged 13–17 years [21]. The standard English questionnaire from WHO was produced, translated into Kiswahili, pre-tested, and used in the Tanzania GSHS [22]. The collected data included basic demographic characteristics such as age, sex, and district, as well as information on violence, unintentional injury, dietary behaviors, hygiene, mental health, physical activity, substance use, and sexual behaviors. Before administering the questionnaires, the data collectors, who were trained medical students from KCMUCo, explained the study purpose to the students and answered any questions they had. The participants then filled out the questionnaires with guidance from the medical students. During data collection, the data collectors made the necessary efforts to preserve privacy and confidentiality. This was accomplished by clearly explaining its importance to participants and making sure there was some distance between them when filling out the questionnaires.

2.4. Instrument Measures

The outcome variable in this study was suicide attempt which was measured using a self-administered questionnaire from the RSHS [23]. Students in this study were asked, “During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide?”. Students were considered to attempt suicide if they attempted suicide at least once during the preceding 12 months. Suicidal plans and ideation were obtained from two questions “During the past 12 months, did you ever consider attempting suicide?” and “During the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?” The response options were “yes or no”.

The explanatory variables included sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics, and social and psychological factors. Sociodemographic characteristics included: age in years, sex (male, female), and schooling district (Moshi municipality, Moshi rural, Siha, and Hai districts). Behavioral variables included ever being physically attacked (none, 1+ times); ever engaged in a physical fight (no, yes); ever being bullied (no, yes); currently using any substance ‘No’ if not used any of the substances (alcohol, cigarette, tobacco, and recreational drugs such as cocaine, heroin, marijuana, khat, and amphetamines) in the past 30 days and ‘Yes’ if otherwise; ever had sex (no, yes); and number of close friends (none, 1+ friend). Social and psychological variables were loneliness, food insecurity, lack of sleep, parental engagement, and support, (never, rarely, sometimes, most of the time; always), suicidal ideation (no, yes), and suicidal plan (no, yes).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were cleaned and analyzed using SPSS software version 20. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages whereas continuous variables were summarized using median and inter-quartile range. The chi-square test was used to compare suicidal attempt proportions by survey year and other participant characteristics. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to determine factors associated with suicidal attempts at a 5% threshold level. The unadjusted logistic regression analysis determined the association between the independent variables and suicidal attempts (binary variable). For the adjusted logistic regression analysis, variables that had the likelihood ratio p values of <0.1 in the unadjusted analysis were included in the adjusted analysis. Age and sex were also included because they are known confounders of suicide attempts for adolescents.

3. Results

Among 4969 secondary school-going adolescents, 4188 (84%) (Survey 1, 3182; Survey 2, 1006) secondary school-going students aged between 13 and 17 years were eligible and included in this analysis (Figure 1). Overall, the median age was 15 years (IQR 14–16), while the mean age for Survey 1 was 14 years (SD 1.0), and the median age for Survey 2 was 17 years (IQR 16–17). More than half (53.0% and 64.8%) were females in surveys 1 and 2, respectively, and (41.6%; Survey 1 and 34.5%; Survey 2) were from Moshi district council (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics of secondary school-going adolescents from two repeated RSHS in 2019 and 2022 in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania.

| Variables | Overall n (%) |

Survey 1 n (%) |

Survey 2 n (%) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 13–15 | 2733 (65.3) | 2692 (84.6) | 41 (4.1) | |

| 16–17 | 1455 (34.7) | 490 (15.4) | 965 (95.9) | |

| Median (IQR), Mean (SD) | 15 (14, 16) | 14 (1.0) | 17 (16, 17) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 1848 (44.1) | 1494 (47.0) | 354 (35.2) | |

| Female | 2340 (55.9) | 1688 (53.0) | 652 (64.8) | |

| Schooling district * | <0.001 | |||

| Moshi municipality | 933 (22.5) | 662 (20.8) | 271 (28.0) | |

| Moshi district council | 1658 (40.0) | 1324 (41.6) | 334 (34.5) | |

| Hai district council | 646 (15.6) | 523 (16.4) | 123 (12.7) | |

| Siha district council | 912 (22.0) | 673 (21.2) | 239 (24.7) | |

| Ever been worried * | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3638 (88.9) | 2795 (90.6) | 843 (84.0) | |

| Yes | 452 (11.1) | 291 (9.4) | 161 (16.0) | |

| Ever been lonely | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3860 (92.2) | 2966 (93.2) | 894 (88.9) | |

| Yes | 328 (7.8) | 216 (6.8) | 112 (11.1) | |

| Current substances use * † | <0.001 | |||

| No | 566 (50.2) | 250 (37.9) | 316 (67.5) | |

| Yes | 561 (49.8) | 409 (62.1) | 152 (32.5) | |

| Ever had sex * | 0.399 | |||

| No | 3784 (90.5) | 2886 (90.7) | 898 (89.8) | |

| Yes | 398 (9.5) | 296 (9.3) | 102 (10.2) | |

| Ever missed class * | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3277 (78.5) | 2571 (80.9) | 703 (70.9) | |

| Yes | 896 (21.5) | 607 (19.1) | 289 (29.1) | |

| Number of close friends * | 0.290 | |||

| No friends | 363 (8.7) | 285 (9.0) | 78 (7.9) | |

| >1 friend | 3798 (91.3) | 2888 (91.0) | 910 (92.1) | |

| Ever been physically attacked * | 0.002 | |||

| No | 3208 (76.8) | 2408 (75.7) | 800 (80.4) | |

| Yes | 968 (23.2) | 773 (24.3) | 195 (19.6) | |

| Ever engaged in a physical fight * | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3363 (80.3) | 2449 (77.0) | 914 (90.9) | |

| Yes | 824 (19.7) | 733 (23.0) | 91 (9.1) | |

| Ever been bullied * | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3688 (88.1) | 2748 (86.4) | 940 (93.7) | |

| Yes | 497 (11.9) | 434 (13.6) | 63 (6.3) | |

| Food insecurity * | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3885 (92.8) | 2924 (91.9) | 961 (95.7) | |

| Yes | 301 (7.2) | 258 (8.1) | 43 (4.3) | |

| Parental engagement * | 0.058 | |||

| No | 2156 (51.6) | 1666 (52.4) | 490 (49.0) | |

| Yes | 2025 (48.4) | 1514 (47.6) | 511 (51.0) | |

| Survey year (Overall) | 4188 | 3182 (76.0) | 1006 (24.0) |

IQR = Interquartile range. * Frequency does not tally due to missing values. † Using at least one substance (alcohol, cigarette, tobacco, khat, marijuana, and amphetamines) in the past 30 days.

Participants in Survey 1 were less worried (n = 291, 9.4%) and lonely (n = 216, 6.8%) compared to those in Survey 2 (n = 161, 16% and n = 112, 11.1%, respectively). Over half (n = 409, 62.1%) of participants in Survey 1 were current substance users, while less than half in Survey 2 (n = 152, 32.5%) reported being current substance users. The proportion of participants who ever missed class was lower in Survey 1 (n = 607, 19.1%) than in Survey 2 (n = 289, 29.1%), while the proportion who ever experienced physical attack was higher in Survey 1 (n = 773, 24.3%) than in Survey 2 (n = 195, 19.6%). Participants in Survey 1 also reported more instances of ever engaging in a physical fight (n = 733, 23%) and ever bullying others (n = 434, 13.6%) compared to Survey 2 (n = 91, 9.1% and n = 63, 6.3%, respectively). Table 1 provides more details on these findings.

Overall, 137 (3.3%) secondary school-going adolescents reported having ever attempted suicide, 271 (6.5%) reported ever having suicidal ideation, and 178 (4.3%) reported ever making a suicidal plan. The reported number of suicide attempts was 95 (3.0%) in Survey 1 and 42 (4.2%) in Survey 2. The number of reported instances of suicidal ideation was 193 (6.1%) in Survey 1 and 78 (7.8%) in Survey 2, while the number of reported instances of making a suicidal plan was 127 (4.0%) in Survey 1 and 51 (5.1%) in Survey 2. The differences between the surveys were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of suicidal attempts by survey year among secondary school-going adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania.

| Variable | Overall n (%) |

Survey 1 n (%) |

Survey 2 n (%) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever attempted suicide | ||||

| No | 4051 (96.7) | 3087 (97.0) | 964 (95.8) | 0.065 |

| Yes | 137 (3.3) | 95 (3.0) | 42 (4.2) | |

| Ever had suicidal Ideation * | ||||

| No | 3912 (93.5) | 2989 (93.9) | 923 (92.2) | 0.053 |

| Yes | 271 (6.5) | 193 (6.1) | 78 (7.8) | |

| Ever made suicidal Plan * | ||||

| No | 4007 (95.7) | 3055 (96.0) | 952 (94.9) | 0.135 |

| Yes | 178 (4.3) | 127 (4.0) | 51 (5.1) |

Overall N = 4188, Survey 1, N = 3182, Survey 2, N = 1006, * Frequency does not tally due to missing values.

In the adjusted analysis, overall, females had approximately three times higher odds (OR = 2.8, 95% CI 1.5–5.1) of attempting suicide compared to males. Participants who reported ever feeling lonely had two times higher odds (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.1–4.3), those who reported ever feeling worried had 99% higher odds (OR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.5), and those who reported ever being bullied had over two times higher odds (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–4.1) of attempting suicide compared to their counterparts. Gender (higher odds in females) (OR = 3.1, 95% CI: 1.5–6.5) was a significant factor for suicide attempts in Survey 1 but not in Survey 2. Ever having sexual experience (OR = 3.4, 95% CI: 1.1–10.7) was a significant factor for suicide attempts in Survey 2 but not in Survey 1 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of factors associated with suicidal attempts among secondary school-going adolescents from two repeated RSHS in 2019 and 2022 in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania.

| Variables | Overall | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) |

p-Value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-Value | AOR (95% CI) |

p-Value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 13–15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 16–17 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 0.924 | 1.6 (0.7, 3.9) | 0.277 | 0.7 (0.1, 8.0) | 0.775 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 2.8 (1.5, 5.1) | 0.001 | 3.1 (1.5, 6.5) | 0.002 | 2.9 (0.9, 9.3) | 0.078 |

| Ever felt lonely (Yes) | 2.2 (1.1, 4.3) | 0.020 | 2.4 (1.0, 5.7) | 0.055 | 1.9 (0.7, 5.5) | 0.215 |

| Ever been worried (Yes) | 1.9 (1.1, 3.5) | 0.033 | 2.0 (0.9, 4.3) | 0.087 | 2.2 (0.8, 6.1) | 0.112 |

| Current substance use (Yes) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.3) | 0.058 | 1.7 (0.7, 3.7) | 0.230 | 1.8 (0.7, 4.5) | 0.218 |

| Ever had sex (Yes) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.9) | 0.235 | 1.0 (0.4, 2.3) | 0.901 | 3.4 (1.1, 10.7) | 0.037 |

| Ever physically attacked (Yes) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) | 0.789 | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 0.708 | 1.6 (0.6, 4.2) | 0.360 |

| Ever engaged in a physical fight (Yes) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | 0.590 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | 0.579 | 1.0 (0.3, 3.4) | 0.955 |

| Ever bullied (Yes) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.1) | 0.016 | 2.1 (1.0, 4.5) | 0.056 | 2.4 (0.8, 7.7) | 0.130 |

| Parental engagement (Yes) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.1) | 0.454 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.6) | 0.451 | 1.2 (0.5, 2.9) | 0.709 |

AOR—Adjusted Odds Ratio. Overall N = 4188, Survey 1, N = 3182, Survey 2, N = 1006.

4. Discussion

The study aimed to determine the prevalence of suicidal attempts and associated factors among secondary school-going adolescents in the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. In this study, the overall prevalence of suicidal attempts was 3.3%, suicidal ideation 6.5%, and suicidal plan 4.3%. Overall, suicidal attempts were associated with sex (higher odds in females), loneliness, worry, and bullying. Being female increased the risk for suicide attempts in Survey 1 but not in Survey 2, and ever had sex in Survey 2 but not in Survey 1.

In this study, the prevalence of suicidal attempts among secondary school-going adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania was alarming. It is concerning to see a relatively high proportion of secondary school-going adolescents reporting having ever attempted suicide, experienced suicidal ideation, or made a suicide plan. This highlights the importance of addressing mental health issues among young people, especially in the school setting. This is a result of poor mental health, decision-making style, coping mechanism, family, and peer relationships [24]. The burden was slightly higher in Survey 2, which included older students (form fours, i.e., fourth and final year of ordinary level secondary school in Tanzania), compared to Survey 1, which included younger form one students. Older students are in late adolescence when they experience biological and social changes which increase the risk of mental health problems [14]. The fact that the differences between the two surveys were not statistically significant suggests that the issue of suicidal thoughts and behaviors is consistent across the study population. If this issue is not addressed, there will be more suicides, as reported by Makoye on the increased rate of suicide in Tanzania, especially among young people [25], which will have a long-term impact on the economy and mental health of the families, communities, and countries left behind by those who die by suicide. This prevalence is lower than the 11.5% reported among secondary school students in Tanzania’s 2014 GSHS report [13]. Weak cultural practices and taboos in Kilimanjaro compared to Dar es Salaam against suicide could be reflective of reporting bias, explaining these differences [26].

Suicide attempts were found to be associated with older adolescents in other studies [27], but not in this study. In addition, this study showed that the prevalence of suicide attempts was higher in females than in males, which is consistent with findings from studies in Jamaica [15] and Togo [28]. This could be because females are more likely to have mental health problems, as well as internalize emotional and behavioral problems than males, making suicide attempts more likely [8]. Furthermore, girls reach puberty earlier than boys due to pubertal changes and estradiol levels in girls, exposing them to love affairs that, if not successful, may lead to a suicide attempt as a coping mechanism for emotional problems [29]. Gender-based interventions that mentor girls by teaching them life skills and how to deal with adversity should be implemented in all schools.

Adolescent students who had ever felt lonely had a higher risk of suicidal attempts than their peers. School loneliness may be caused by a lack of desired peer and social relationships, belongingness, and having no one to share problems faced resulting in suicidal behaviors [30]. Lack of counseling services in schools or neglect may be a possible reason for loneliness, increasing the risk of suicide attempts [31].

Substance use was not associated with suicide attempts in this study but, adolescents who use substances have poor social and peer relationships which act as a driver for mental health problems that lead to suicidal behaviors, and have an impact on academic performance [32].

Secondary school-going adolescents who were ever worried were more likely to attempt suicide than those who were never worried. Worrying leads to self-doubt, insecurity, and confusion, which may lead to suicide attempts as a solution to anxiety or distress [30]. This has an impact on student performance in school because it reduces their ability to think or concentrate in class, which leads to school dropout, failure, and poor academic achievement [17]. In-school counseling programs for depressed students and survivors of suicide attempts should be established.

Bullying was also linked to suicide attempts in this study, which is like other studies in Mongolia [33] and from 90 countries in a pooled analysis [15]. Students who are victims of bullying have low self-esteem and experience loneliness, distress, and mental health problems [34]. Anti-bullying policies and programs in schools should be strengthened to prevent suicide in this population.

These results highlight the importance of addressing factors such as loneliness, bullying, and sexual experiences in preventing suicide among secondary school-going adolescents. It may also be important to consider gender differences in developing suicide prevention programs, as being female was a significant factor for suicide attempts in one of the surveys. Limiting access to suicide methods such as poisons, firearms, and drugs and treating mental disorders, media reporting on suicide, socio-emotional life skills in adolescents, and managing and following up on everyone affected by suicidal behaviors are all evidence-based interventions that can help prevent suicide attempts [34]. Given the high prevalence of suicide ideation and attempts, particularly among female students, healthcare professionals and educators should incorporate screening for suicidal thoughts and risk factors into routine care. Addressing factors such as loneliness, worry, and bullying in schools may also be effective in reducing the risk factors for suicidal attempts among adolescents. The differences in risk factors for suicidal attempts between the two surveys highlight the need for ongoing monitoring and targeted interventions to address the changing risk factors for suicide among adolescents.

Limitations of the Study

Some limitations to this study should be noted. Because the survey only included school-going adolescents, the findings cannot be generalized to all adolescents in Tanzania and may underestimate the prevalence. The study relies on self-reported data and may not accurately reflect the true prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. It is also possible that some students may have underreported their experiences due to stigma or fear of consequences. This study’s repeated cross-sectional design did not link participants in the two surveys, potentially leading to duplicated responses, bias, and unaccounted overlap. This may have impacted the statistical power, representativeness, and generalizability of the findings. As such, interpreting the study’s results requires caution and future research should address overlap in serial surveys.

5. Conclusions

The present study suggests an alarmingly high level of suicidal attempts among secondary school-going adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania with being female, ever having been lonely, ever having been worried, and ever being bullied being significant associated factors. Health promotion programs in schools should target these factors to prevent suicide attempts among adolescents.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Institute of Public Health at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College for providing data for further analysis. We would also like to thank the students who took part in the surveys and KCMUCo medical students for participating in the data collection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; methodology, J.S. and R.M.; software, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; validation, L.M., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; formal analysis, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; investigation, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; resources, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; data curation, J.S.; writing-original draft preparation, J.S.; writing-review and editing, J.S., L.M., R.M., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; visualization, J.S., L.M., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; supervision, L.M., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; project administration, J.S., I.B.M. and J.S.N.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research and Ethics Review Committee of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College (KCMU-CRERC) on 8 June 2022, approval number PG.17/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. There were no any invasive procedures that necessitated parental consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request to the Director of the Institute of Public Health at KCMUCo at iph@kcmuco.ac.tz or through the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Suicide. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2021. [(accessed on 1 September 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates. 2019. [(accessed on 1 September 2022)]. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326948.

- 3.UNICEF Invest More in Mental Health. 2021. [(accessed on 17 March 2023)]. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/montenegro/en/stories/unicef-invest-more-mental-health.

- 4.McKinnon B., Gariépy G., Sentenac M., Elgar F.J. Adolescent suicidal behaviors in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016;94:340–350F. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.163295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLoughlin A.B., Gould M.S., Malone K.M. Global trends in teenage suicide: 2003–2014. QJM. 2015;108:765–780. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) Preventing suicide. CMAJ. 2014;143:609–610. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haagsma J.A., Graetz N., Bolliger I., Naghavi M., Higashi H., Mullany E.C. The global burden of injury: Incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. INJ Prev. 2015;22:3–18. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pengpid S., Peltzer K. Prevalence and correlates of past 12-month suicide attempt among in-school adolescents in Guatemala. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019;12:523–529. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S212648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cluver L., Orkin M., Boyes M.E., Sherr L. Child and adolescent suicide attempts, suicidal behavior, and adverse childhood experiences in South Africa: A prospective study. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;57:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaikh M.A., Lloyd J., Acquah E., Celedonia K.L., Wilson M.L. Suicide attempts and behavioral correlates among a nationally representative sample of school-attending adolescents in the Republic of Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:843. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3509-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shayo F.K., Lawala P.S. Does bullying predict suicidal behaviors among in-school adolescents? A cross-sectional finding from Tanzania as an example of a low-income country. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;19:400. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., Nkomola P., Xue Q., Lin X., Xie X., Hou F. Health Risk Behaviors and Suicide Attempt among Adolescents in China and Tanzania: A school-based study of countries along the Belt and Road. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020;118:105335. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyandindi U.S. Tanzania Global School-Based Student Health Survey Report. The United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; Dodoma, Tanzania: 2017. WHO Document. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyundo A., Manu A., Regan M., Ismail A., Chukwu A., Dessie Y. Factors associated with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and behaviors amongst sub-Saharan African adolescents aged 10-19 years: Cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2020;25:54–69. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campisi S.C., Carducci B., Akseer N., Zasowski C., Szatmari P., Bhutta Z.A. Suicidal behaviors among adolescents from 90 countries: A pooled analysis of the global school-based student health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1102. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . Preventing Suicide: LIVE LIFE Implementation. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2022. [(accessed on 1 September 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MSD-UNC-MHE-22.02. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pengpid S., Peltzer K. Single and multiple suicide attempts: Prevalence and correlates in school-going adolescents in Jamaica in 2017. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2020;19:659–665. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S277844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) The 2022 Population and Housing Census, Preliminary Report, Tanzania. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS); Dodoma, Tanzania: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MOEST . Tanzania Mainland Education Sector Performance Report (2018/2019), Tanzania. MOEST; Dodoma, Tanzania: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavura R.A., Nyaki A.Y., Leyaro B.J., Mamseri R., George J., Ngocho J.S. Prevalence of substance use and associated factors among secondary school adolescents in Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0274102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . Adolescent and Young Adult Health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2021. [(accessed on 5 September 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MoHCDGEC . Tanzania Mainland Global School-Based Student Health Survey Country Report, Tanzania. MoHCDGEC; Dodoma, Tanzania: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . GSHS Questionnaire. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2021. [(accessed on 21 November 2022)]. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey/questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasserman D., Carli V., Losue M., Javed A., Herrmann H. Suicide prevention in childhood and adolescence: A narrative review of current knowledge on risk and protective factors and effectiveness of interventions. Asian Psychiatry. 2021;13:e12452. doi: 10.1111/appy.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makoye K. Suicide Rates Rise Sharply in Tanzania Amid Economic, Social Woes. 2021. [(accessed on 13 December 2022)]. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/suicide-rates-rise-sharply-in-tanzania-amid-economic-social-woes/2360130#.

- 26.Dunlavy A.C., Aquah E.O., Wilson M.L. Suicidal ideation among school-attending adolescents in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. [(accessed on 13 December 2022)];Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2015 17:1–9. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/thrb/article/view/102996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X., Huang Y., Liu Y. Prevalence, distribution, and associated factors of suicide attempts in young adolescents: School-based data from 40 low-income and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darré T., Consuela K.C., Saka B., Djiwa T., Ekouévi K.D., Napo-Koura G. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in subjects aged 15-19 in Lomé (Togo) BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12:187. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balzer B.W.R., Duke S.A., Hawke C.I., Steinbeck K.S. The effects of estradiol on mood and behavior in human female adolescents: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015;174:289–298. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2475-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey A.R., Bista B., Dhungana R.R. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adolescent students in Nepal: Findings from Global School-based Students Health Survey. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0210383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aboagye R.G., Ahinkorah B.O., Seidu A.A., Okyere J., Frimpong J.B. In-school adolescents’ loneliness, social support, and suicidal ideation in sub-Saharan Africa: Leveraging Global School Health data to advance mental health focus in the region. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0275660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erzen E., Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2018;64:427–435. doi: 10.1177/0020764018776349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badarch J., Chuluunbaatar B., Batbaatar S., Paulik E. Suicide Attempts among School-Attending Adolescents in Mongolia: Associated Factors and Gender Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:2991. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang J.J., Yu Y., Wilcox H.C., Kang C., Wang K., Wang C., Wu Y., Chen R. Global risks of suicidal behaviors and being bullied and their association in adolescents: School-based health survey in 83 countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;19:100253. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request to the Director of the Institute of Public Health at KCMUCo at iph@kcmuco.ac.tz or through the corresponding author.