Abstract

Background

The relatively rare carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is a neoplasia with a good prognosis compared to pancreatic cancer. Preoperative staging is important in planning the most suitable surgical intervention.

Aim

To prospectively evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS) in comparison with conventional US and CT scan, in staging of patients with ampullary carcinoma.

Patients and Methods

20 patients (7 women and 13 men) with histologically proven carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater were assessed by EUS, CT scan and US. Results were compared to surgical findings.

Results

Endoscopic biopsies were diagnostic in 76% of the patients. Detection of ampullary cancer with US and CT scan was 15% and 20% respectively. Only indirect signs of the disease were identified in the majority of cases using these methods. Overall accuracy of EUS in detection of ampullary tumours was 100%. The EUS was significantly (p < 0.001) superior than US and CT scan in ampullary carcinoma detection. Tumour size, tumour extension and the existence of metastatic lymph nodes were also identified and EUS proved to be very useful for the preoperative classification both for the T and the N components of the TNM staging of this neoplasia. The diagnostic accuracy for tumour extension (T) was 82% and for detection of metastatic lymph nodes (N) was 71%.

Conclusion

EUS is more accurate in detecting ampullary cancer than US and CT scan. Tumor extension and locally metastatic lymph nodes are more accurately assessed by means of EUS than with other imaging methods.

Introduction

Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is an infrequent neoplasia. Histologically the tumour is an adenocarcinoma arising from either pancreatic ducts, acinus or bile ducts and is often of a low grade malignancy. Both sexes are affected, the male to female ratio being 2:1 with most patients being between 50 and 69 years of age [1,2]. Early diagnosis is vital because after a complete surgical resection the five-year survival rate can be expected to be approximately 40% [3].

Early symptoms (pain, cholestasis, intermittent jaundice) result from the extension of the tumour and either the obstruction or the compression of the papillary duct. Extension of the tumour into the duodenum causes occult anemia or intestinal obstruction [2,4].

Endoscopic Ultrasonography (Endosonography, EUS) is a minimally invasive new imaging procedure. In this method a high frequency transducer (7.5 and 12 MHz) is placed into the duodenum, offering a detailed ultrasound image of the duodenal wall, at the convergence of the common bile and pancreatic duct. Even small papillary tumour masses can be detected with this method [5].

In this prospective study we evaluate the accuracy of EUS in detection and preoperative TNM staging (T and N classification) of ampullary carcinomas. Data on clinical presentation, endoscopic findings, endosonographic findings, US and CT scan findings, treatment and follow-up of 20 patients with carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater are reported.

Patients and Methods

Between July 1993 and February 2000 twenty patients having carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater were prospectively evaluated. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital. An Informed consent for diagnostic examinations was obtained from all patients. Seven women and 13 men, aged 40 to 87 years with a median age of 67 years were included in the study. ERCP and clinical findings of a subgroup of these patients were in part reported elsewhere [6].

The diagnosis was confirmed by histological examination of the specimens, taken at either endoscopy or surgery. All patients were subjected to clinical and laboratory tests. All patients were examined by Ultrasonography (US) and CT scan prior to endoscopic examination. Conventional CT scans were performed with a Philips Lx scanner with a slice thickness of a 10 mm, with oral and intravenous contrast in 13 patients (those diagnosed prior to 1997). Seven patients were subjected to spiral CT (after 1997).

Detection of a tumour mass by means of US and CT scan with direct (visualization of the tumour) or indirect signs of tumour (bile or pancreatic duct dilatation, presence of lymph nodes), and distal metastasis were noted.

Endosonographic examination was also performed in all patients. The Olympus Co GF-EUM3 system (frequency: 7.5 or 12 MHz) with a water filled balloon technique was used. Size and echogeneity of the tumour, local invasion, existence of suspected metastatic lymph nodes and anatomical relation of the tumour to the adjacent abdominal structures were assessed.

Lymph nodes were assessed for malignancy on the basis of four well established criteria which were: larger than 10 mm, round, homogeneous echo pattern and sharp borders [7-10]. T and N classification, according to the TNM staging system [11] was also recorded. (Table 1).

Table 1.

T N M classification of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater

| T (Primary tumour) | |

| Tx | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

| T1 | Tumour limited to the ampulla of Vater or aphincter of Oddi |

| T2 | Tumour invades duodenal wall |

| T3 | Tumor invades 2 cm or less into pancreas |

| T4 | Tumor invades more than 2 cm into pancreas and/or into other adjacent organs |

| N (Regional lymph nodes) | |

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| NO | No regional lymph nodes metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph nodes metastasis |

| M (Distant metastasis) | |

| Mx | Distant metastasis not assessable |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis: Hepatic metastasis, peritoneal dissemination, lymph nodes metastasis along the splenic vein or at the splenic hilum |

Duodenoscopy and ERCP were performed in all patients after US, CT and EUS assessment. Endoscopic biopsies were taken after sphincterotomy. Seventeen patients were operated upon. Patients were followed-up for a period of 2–75 months (median 27 months) until February 2000. One patient refused any therapeutic procedure and was lost to follow-up one month after diagnosis.

Statistical analysis was done by the chi-square paired sample test for proportions with Yates continuity correction. Survival analysis in 17 patients that underwent surgery was performed using the Kaplan-Meier procedure.

Results

Symptoms, clinical characteristics and laboratory tests of all patients are shown in table 2. The most common symptoms were jaundice (70%), weight loss (55%), epigastric pain (50%), fever (45%), nausea and/or vomiting (35%). An elevated Alkaline Phosphatase (SAP) and γ-Glutamyl Transpeptidase (95%) were the most common laboratory abnormalities. Elevated ALT and AST (40%) and anemia (35%) were also common. In table 3 we summarize endoscopic, imaging, endosonographic findings as well as outcome of all patients.

Table 2.

Clinical and Laboratory data of the patients on admission. Anemia is defined as a decrease of haemoglobin more than 10% of the normal value. Elevated levels of SAP and γ-Gt (Cholestatic enzymes) and ALT, AST are defined as more than double of the normal values.

| Case | Sex | Age | Jaundice | Fever | Pain | Nausea | Weight loss | Anemia | SAP, γ Gt | ALT, AST |

| 1 | M | 64 | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | M | 43 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | M | 70 | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | M | 80 | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | M | 67 | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| 6 | F | 75 | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - |

| 7 | F | 47 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| 8 | M | 62 | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | - |

| 9 | M | 57 | + | + | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| 10 | F | 78 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 11 | M | 40 | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| 12 | F | 64 | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| 13 | M | 77 | - | - | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| 14 | M | 87 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| 15 | F | 68 | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | - |

| 16 | M | 73 | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| 17 | F | 63 | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| 18 | F | 59 | + | - | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| 19 | M | 69 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | M | 72 | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

Table 3.

Endoscopic biopsy, US and CT scan findings (direct or indirect signs), EUS classification for T and N (TNM staging), treatment, follow-up and outcome of the 20 patients with cancer of the ampulla of Vater.

| Case | Endoscopic biopsy | US | CT | EUS T and N | Treatment | Follow-up (Febr 00) | Outcome (Febr 00) |

| 1 | Ca | Indirect | Direct | T3N1 | Palliative | 43 | Died |

| 2 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T2N1 | Whipple | 64 | Died |

| 3 | - | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Local excision | 2 | Died |

| 4 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T2N0 | Stent | 63 | Died |

| 5 | - | Direct | Indirect | T3N1 | Lost | lost | Lost |

| 6 | normal | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Whipple | 75 | Died |

| 7 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T4N1 | Local excision | 34 | Alive |

| 8 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T2N1 | Whipple | 21 | Alive |

| 9 | - | Indirect | Indirect | T2N0 | Stent | 23 | Alive |

| 10 | normal | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Palliative | 7 | Died |

| 11 | Ca | Direct | Indirect | T2N1 | Whipple | 30 | Died |

| 12 | Normal | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Local excision | 26 | Alive |

| 13 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Whipple | 23 | Alive |

| 14 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T4N1 | Whipple | 2 | Died |

| 15 | Ca | Indirect | Direct | T3N1 | Local excision | 39 | Died |

| 16 | Ca | Indirect | Direct | T2N1 | Whipple | 22 | Alive |

| 17 | Dysplasia | Indirect | Indirect | T2N0 | Whipple | 15 | Alive |

| 18 | Ca | Indirect | Direct | T2N1 | Whipple | 12 | Alive |

| 19 | Ca | Direct | Indirect | T3N1 | Whipple | 8 | Alive |

| 20 | Ca | Indirect | Indirect | T3N1 | Whipple | 3 | Alive |

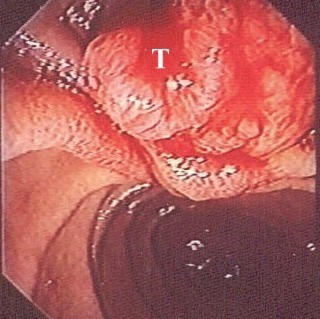

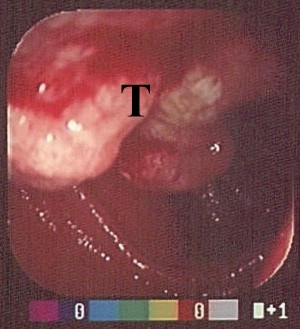

The endoscopic appearance of the papilla was abnormal (polypoid or exophytic tumour mass) in 17/20 patients (Fig. 1, Fig 3). In three cases the tumour was evident only after endoscopic sphincterotomy of a protruding papilla. In the rest of the cases a tumour mass was evident. On ERCP a dilatation of the peripheral part of the common bile duct (15/20) and of the main pancreatic duct (6/20) were found. Multiple endoscopic biopsies were taken from 17 patients. In one patient endoscopic biopsies showed only severe dysplasia, while in three patients the biopsies were normal. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater was diagnosed in the remaining 13 patients.

Figure 1.

Polypoid, exophytic mass of the ampulla of Vater. Endoscopic appearance (T: tumour mass).

Figure 3.

Polypoid tumour mass of the papilla of Vater with ulcerations. Tumour partially obstructs the enteric lumen (T: tumour mass).

Three patients had a surgical excision based on EUS findings despite an almost normal endoscopic appearance of the ampulla. Histology of the surgical specimens, comfirmed the presence of a carcinoma.

On conventional US, the tumour was identified only in 3 cases (15%) as a hypoechogenic mass at the peripheral part of the common bile duct. In 14 patients indirect signs of malignancy (dilatation of the common bile duct: 12/20, main pancreatic duct dilatation: 2/20, enlarged lymph nodes: 9/20), were noted. In two patients enlarged lymph nodes along the splenic vein were detected (Ml according to the TNM classification). In the remaining three patients the examination was completely normal.

On CT scan, findings were suggestive of a malignant tumour at the distal part of the common bile duct in 4 cases. 2/13 in conventional and 2/7 in spiral CT scan (30%) with an overall accuracy of 20%. Indirect signs of malignancy were evident in 16/20 (80%) cases (dilatation of the common bile duct: 14/20, main pancreatic duct dilatation: 5/20, enlarged lymph nodes: 12/20). In two patients enlarged lymph nodes at the splenic hilum and along the splenic vessels were detected (Ml). In one patient peritoneal dissemination of the mass was shown (Ml).

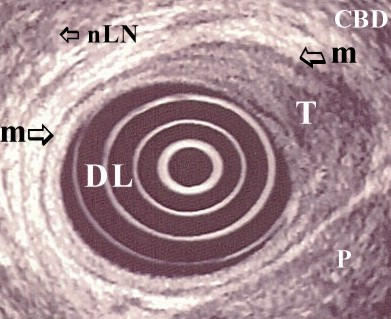

On EUS tumour was identified in all patients. A heterogeneous hypoechoic mass was the common presentation (fig 2, fig 4). T and N classification was feasible in all cases. Invasion of the duodenal wall (T2) was found in 8 patients. Tumour invasion within 2 cm on the pancreatic parenchyma was found in 10 patients. These patients were classified as having a T3 carcinoma. Two patients had a tumour that invaded more than 2 cm into the pancreas and they were classified as T4. In 17 patients suspected metastatic lymph nodes were detected (N1).

Figure 2.

Corresponding endosonographic image (7.5 MHz) of the same (fig. 1) patient. Hypoechoic mass invading the duodenal wall. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater:T2N0. (DL: duodenal lumen, T: tumour mass, CBD: common bile duct, m: muscularis propria, nLN: non metastatic lymph node, P: pancreas).

Figure 4.

Corresponding endosonographic image (7.5 MHz) of the same (fig. 3) patient. Hypoechoic mass invading the duodenum. Enlarged hypoechoic regional lymph nodes are also present. Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater:T3N1. (DL: duodenal lumen, T: tumour mass, LN: metastatic lymph nodes).

Whipple resection (pancreatoduodenectomy) was performed in 11 patients. Four patients had a local resection of the tumour, 2 patients had a palliative anastomosis. In total 17 patients were operated upon. Two patients refused surgery and had a stent endoscopically placed.

Table 4 shows the findings of US, CT and EUS concerning tumour and LN staging as well as indirect signs of tumour presence compared to the surgical findings. Preoperative T staging by means of EUS was confirmed in 14/17 patients (82%). From the remaining 3 patients, in 2 the T stage was overestimated (T3 and T4 instead of T2 and T3 respectively) and in one underestimated (T2 instead of T3). N classification was surgically confirmed in 12/17 (71%) of the cases. All of the remaining 5 patients were overestimated by means of EUS. No metastatic lymph nodes were found in surgical samples.

Table 4.

Evaluation of ampullary cancer by means of US, CT scan and EUS and comparison to surgery findings in 17 patients who underwent surgery. Distribution of T stage, enlarged lymph nodes (for US and CT scan), N stage (for EUS and Surgery), Common bile duct (CBD) and main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation (for US and CT scan) and M stage (for US, CT scan and Surgery).

| US | CT scan | EUS | Surgery | |

| T stage* | Advanced 2/17 (12%) | Advanced 4/17 (24%) | Early: 6/17 Advanced: 11/17 | Early: 8/17 Advanced:9/17 |

| Enlarged LN or N stage | 8/17 (47%) | 11/17 (65%) | N0:1/17 N1:16/17 | N0:5/17 N1:12/17 |

| M stage | 2/17 | 3/17 | NA** | 3/17 |

| CBD and MPD dialatation | CBD 12/17 (71%) MPD 2/17 (12%) | CBD 13/17 (76%) MPD 5/17 (29%) | NA | NA |

* Early stage: T1 and T2 * Advanced stage: T3 and T4 **Nonapplicable

Overall accuracy of the EUS for detection of the tumour was 100%. EUS was significantly better than both CT scan (20%) and US (15%) in directly detecting ampullary tumour (p < 0.001).

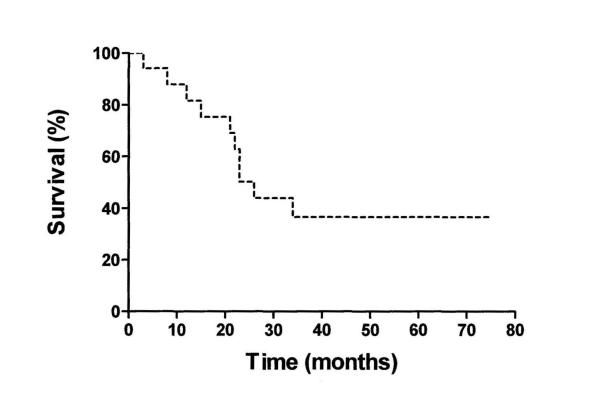

The median survival time for the patients who underwent surgery was 64 months (95% CI: 9–119) The Kaplan-Meier survival curve of those operated on is shown in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of operated patients

Discussion

Cancer of the ampulla of Vater must be differentiated from cancer of the head of the pancreas. Prognosis and potential therapeutic intervention are different. 87% of patients with carcinoma of the ampulla and 47% of those with a malignancy of the duodenum have a potentially operable tumour compared with only 22% of patients with tumours arising from the head of the pancreas [2,12]. Therefore a noninvasive accurate technique for detection and staging is mandatory for these patients.

The endoscopic appearance of the papilla was abnormal in most of our patients. However the distinction between an impacted stone, a benign tumour or a malignancy is not always feasible. ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy was a helpful diagnostic procedure in cases of intraampullary tumors with a protruding papilla. In 3 cases of our patients a polypoid mass was evident only after sphincterotomy. However, ERCP is an invasive procedure with a considerable morbidity.

Moreover, endoscopic biopsies do not always allow for reliable diagnosis and preoperative assessment of tumours of the papilla of Vater. Villous adenomas can be associated with an adenocarcinoma and a histological diagnosis of an adenoma does not exclude the presence of an adenocarcinoma elsewhere in the tumour. [13-16]. In our patients endoscopic biopsies were diagnostic for an adenocarcinoma in 13/17 cases (76%). In one patient a severe dysplasia was reported and in 3 cases histology was completely normal. In other series the positive histological yield was only 50% of the cases [17]. Our results are similar to the studies from Japan and Boston where approximately one-third of the patients were misdiagnosed [18,19].

Staging of the disease is also very important since there is a close correlation between staging and survival rate [2,20-22]. Conventional imaging techniques such as US and CT scan are not very efficient in both diagnosis and staging. CT scan cannot be used as the only diagnostic procedure for confirming or excluding the diagnosis of ampullary cancer. Staging of ampullary cancer by CT alone was found inaccurate for the evaluation of tumour resectability [23]. Moreover these methods can not detect small tumours. They can indicate the presence of a tumour by indirect signs such a dilatation of the common bile and main pancreatic duct, or the presence of malignant lymph nodes or distal metastases. ERCP can also demonstrate pancreatic and bile duct dilatation [2,6]. In a recent study, CT scan was reported to detect dilatations of peripancreatic veins with nonvisualization of inferior peripancreatic veins as an indirect sign of tumour invasion of the peripancreatic tissue [24].

In our patients conventional US showed a tumour in only 15% of the cases. In 70% of the cases indirect signs of the disease and in 15% no abnormalities were identified. On CT scan, a tumour was directly visualized in only 20% of the patients. In most cases (16/20), indirect signs of the disease were evident but not diagnostic. Conventional CT scan was directly diagnostic in less cases (16%) than spiral CT (30%). This fact underlines the higher accuracy of spiral CT in detecting tumours of the pancreas region [25,26].

EUS provides an accurate method for detecting and staging of ampullary tumours, especially those infiltrating into the pancreas. It also detects tumour infiltration of the proximal blood vessels. However, EUS is unable to detect distal metastasis. Finally, EUS is useful for planning an appropriate therapeutic approach and for preventing unnecessary extensive surgery. EUS findings have been found to correlate well with prognosis [27-32].

In our study survival for those patients selected by means of EUS for a Wipple's procedure was considerably better compared to those who had only a palliative procedure, even if this was not statistically significant due to the small number of patients. This finding agrees with a previous observation according to which EUS for selecting patients for local resection may be a cost-effective strategy [33].

In our patients EUS was highly accurate in directly detecting ampullary tumours making this modality the imaging method of choice. Moreover, in our study the EUS accuracy for tumour invasion (T staging), was 82%. Endosonography had also a relatively high accuracy (71%) in diagnosing regional lymph node metastases (N1 stage).

In agreement with other studies comparing the accuracy of EUS in differentiating between early and advanced ampullary carcinomas (T1/T2 vs T3/T4) where a concordance between 78% and 84% was reported, we found similar accuracy rates [25,27-29,31,33].

The reported accuracy of EUS in predicting regional lymph nodes metastasis in ampullary carcinoma varies between 59% and 68% [25,27,34]. These findings are comparable or slightly lower than ours (71%). The differences that occur between our results and some of the other studies, could be attributed to more advanced tumours in our patients compared to the mentioned studies. In fact, 60% of our patients had an advanced carcinoma.

New modalities such as Intraductal US (IDUS) and spiral CT have been used for tumour evaluation. IDUS was significantly superior to EUS and CT scan. (100% vs 59.3% vs 29.6% respectively). Sensitivity and specificity rates for IDUS and EUS were 100% versus 62.5% and 75% versus 50%, respectively. Overall accuracy rate in tumour diagnosis for IDUS was reported significantly superior to EUS (89% vs 56%) [35]. However in our hands as well as in other studies [25,27-29,31,33] overall diagnostic accuracy for tumour detection was higher reaching levels as high as 84%. The reason for the relatively low accuracy of EUS in this study compared to the rest is not evident. IDUS appears to be the most effective imaging method in visualizing and staging tumors of the papilla but this remains to be confirmed by other studies. Combining ERCP with a catheter probe sonography offers a new diagnostic modality that has some potential advantages for local staging of small tumours of the papilla [35-37].

The sensitivity and specificity of another diagnostic modality, spiral CT, for detecting involvement by the tumour of the superior mesenteric vein, portal vein and lymph nodes have been reported similar to that of EUS [26]. However this was not true in our hands. We think that this discrepancy was due to the small number of our patients undergoing spiral CT (7/20).

In conclusion compared with classical imaging procedures like US and CT scan, EUS is an effective method for the evaluation of the extent of invasion of ampullary carcinoma as well as for the involvement of regional lymph nodes before operation. Spiral CT scan may be combined with EUS in order to evaluate distal metastases.

Competing interests

None declared

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Panagiotis Skordilis, Email: pansk@caramail.com.

Ioannis A Mouzas, Email: mouzas@med.uoc.gr.

Philippos D Dimoulios, Email: fdimoul@yahoo.com.

Georgios Alexandrakis, Email: galexa@caramail.com.

Joanna Moschandrea, Email: joanna@med.uoc.gr.

Elias Kouroumalis, Email: kouroum@med.uoc.gr.

References

- Scarpa A, Pederzoli P, Zamboni G. Genetics of Pancreatic and Ampullary Tumors. In: CG Dervenis, editor. Advances in Pancreatic Disease. Stuttgard – New York: George Thieme Verlag.; 1996. pp. 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock SH, Dooley J. Disease of the Liver and Biliary System. 9. London: Blackwell Scientific Publications.; 1993. Disease of the Ampulla of Vater and Pancreas. pp. 599–605. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmey MB, Yasuda K, Kawai K. Endoscopic Ultrasound. In: T Yamada, DH Alpers, Owyang C, Powell DW, Silverstein FE, editor. In Textbook of Gastroenterology. Two. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott; 1991. pp. 2343–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar K, Deeb LS, Bikhazi K, Arnaout MS. Unusual manifestation of an ampullary tumor presenting with severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Digestion. 1999;60:583–586. doi: 10.1159/000007711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chak A. Endoscopic Ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2000;32:146–152. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzas IA, Skordilis P, Frangiadakis N, Leondidis C, Alexandrakis G, Potamianos S, Kouroumalis E, Manousos ON. Carcinoma of the Ampulla of Vater in Crete. A clinical and ERCP Registry over Eight Years. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tio TL, Tytgat GN. Endoscopic ultrasonography in analysing peri-intestinal lymph node abnormality. Preliminary results of studies in vitro and in vivo. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986;123:158–163. doi: 10.3109/00365528609091878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tio TL, Kallimanis GE. Endoscopic ultrasonography of perigastrointestinal lymphnodes. Endoscopy. 1994;26:776–779. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano MF, Sivak MV, Jr, Rice T, Gragg LA, Van Dam J. Endosonographic features predictive of lymph node metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:442–446. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano MF, Alcocer E, Chak A, Nguyen CC, Raijman I, Geenen JE, Lahoti S, Sivak MV., Jr Evaluation of metastatic celiac axis lymph nodes in patients with esophageal carcinoma: accuracy of EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:352–356. doi: 10.1053/ge.1999.v50.98154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 5 1997. UICC TNM Classification of malignant tumours. [Google Scholar]

- Sellner FJ, Riegler FM, Machacek E. Implications of histological grade of tumour for the prognosis of radically resected periampullary adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:865–870. doi: 10.1080/11024159950189375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyuela C, Cugat E, Veloso E, Marco C. Treatment options for villous adenoma of the ampulla of Vater. HPB Surg. 2000;11:325–330. doi: 10.1155/2000/86476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel J, Poremba C, Dietl KH, Bocker W, Domschke W. Tumors of the papilla of Vater. Inadequate diagnostic impact of endoscopic forceps biopsies taken prior to and following sphincterotomy. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1227–1231. doi: 10.1023/A:1008368807817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi NA, Mindrul V, Broide E, Scapa E. The contribution of endoscopy and biopsy to the diagnosis of periampullary tumors. Endoscopy. 1998;30:538–543. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolte M, Pscherer C. Adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the papilla of Vater. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:376–382. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois N, Dunham F, Verhest A, Cremer M. Endoscopic biopsies of the papilla of Vater at the time of endoscopic sphincterotomy: difficulties in interpretation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:163–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(84)72357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M, Kitamura K. Endoscopic biopsy has limited accuracy in diagnosis of ampullary tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:588–592. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Defining the criteria for local resection of ampullary neoplasms. Arch Surg. 1996;131:366–371. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430160024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RH, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Pancreatico-duodenectomy of ampullary carcinoma. Am Surg. 1999;65:1043–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkevold KE, Kambestad B. Staging of carcinoma of the pancreas and ampulla of Vater. Tumor (T), lymph node (N), and distant metastasis (M) as prognostic factors. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:249–259. doi: 10.1007/BF02785822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beger HG, Treitschke F, Gansauge F, Harada N, Hiki N, Mattfeldt T. Tumor of the ampulla of Vater: experience with local or radical resection in 171 consecutively treated patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134:526–532. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen HB, Pihl HE, Tjalve E, Burcharth F. CT diagnosis of pancreatic or periampullary cancer. Ugeskr Laeger. 1994;156:7534–7537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Mori H, Kiyosue H, Matsumoto S, Hori Y, Maeda T. CT assessment of the inferior peripancreatic veins: clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:677–684. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon ME, Carpenter SL, Elta GH, Nostrant TT, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG, B Stotland, Rosato EF, Morris JB, Eckhauser F, et al. EUS compared with CT, MRI and angiography and the influence of biliary stenting on staging accuracy of ampullary neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midwinter MJ, Beveridge CJ, Wilsdon JB, Bennett MK, Baudouin CJ, Charnley RM. Correlation between spiral CT, endoscopic ultrasonography and findings at operation in pancreatic and ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 1999;86:189–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo H, Chijiiwa Y, Akahoshi K, Hamada S, Matsui N, Nawata H. Preoperative staging of ampullary tumours by endoscopic ultrasound. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:443–447. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.857.10505006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscail L, Pages P, Berthelemy P, Fourtanier G, Frexinos J, Escourrou J. Role of EUS in the management of pancreatic and ampullary carcinoma: a prospective study assessing resectability and prognosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:34–40. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tio TL, Sie LH, Kallimanis G, Luiken GJ, Kimmings AN, Huibregtse K, Tytgat GN. Staging of ampullary and pancreatic carcinoma: comparison between endosonography and surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:706–713. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch T, Classen M. Endoscopic ultrasonography, an addition to pancreas diagnosis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1993;123:1059–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Mukai H, Cho E, Nakajima M, Kawai K. The use of endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and staging of carcinoma of the papilla of Vater. Endoscopy. 1988;20:218–222. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo L. Staging of ampullary carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:A128–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk DM, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL, Brugge WR. The use of endoscopic ultrasonography to reduce the cost of treating ampullary tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Nian W, Zhang L, Liang J. Endoscopic ultrasonography assessment in preoperative staging for carcinoma of ampulla of Vater and extrahepatic bile duct. Chin Med J. 1996;109:622–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel J, Hoepffner N, Sulkowski U, Reimer P, Heinecke A, Poremba C, Domschke W W. Polypoid tumors of the major duodenal papilla: preoperative staging with intraductal US, EUS, and CT. A prospective, histopathologically controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh A, Goto H, Naitoh Y, Hirooka Y, Furukawa T, Hayakawa T. Intraductal ultrasonography in diagnosing tumor extension of cancer of the papilla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel J, Domschke W. Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) of the pancreato-biliary duct system. Personal experience and review of literature. Eur J Ultrasound. 1999;10:105–115. doi: 10.1016/S0929-8266(99)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]