Abstract

Objectives

Following the amendment of the Thai abortion law in February 2021, the authors conducted an anonymous survey to assess knowledge, attitude, and intended practice toward abortion among fifth-year medical students at Chulalongkorn University.

Study design

The authors developed a self-administrated questionnaire consisting of three parts: knowledge of the recently amended Thai abortion law, attitude toward abortion, and intended practices. Pilot testing showed a high Cronbach's alpha and test-retest reliability coefficient.

Results

Of the 292 surveyed medical students, 70% completed the questionnaire. The mean ± standard deviation of the knowledge part was 6.9 ± 1.8, of which the maximum score was 10. Nearly half of the participants (45.6%) answered at least 80% of the knowledge statements correctly. Sixty-four percent of participants answered correctly on the gestational limit for first-trimester abortion. Around one-third of participants answered correctly on the gestational limit for second-trimester abortion. Most participants (86.8%) agreed that abortion is a woman’s right. The most acceptable conditions for abortion were pregnancy as a result of rape (93%) and serious anomalies that cause a nonviable neonate (95.6%).

Conclusions

Participants exhibited a lack of understanding regarding the legal gestational limit, which is a key aspect of the amendment. The findings of this study urge medical schools to emphasize the revised Thai abortion law in the Obstetrics and Gynecology curriculum.

Implications

Our results show that encouraging medical students to have up-to-date knowledge regarding the amendment of Thai abortion law may support their future decision to provide safe abortion services.

Keywords: Attitude, OB-GYN curriculum, Gestational limit, Knowledge, Practice, Thai abortion law

1. Introduction

Abortion law in Thailand was initially imported from Europe in the 19th century, which women and abortion providers were penalized with imprisonment and fines [1]. The former Thai Abortion Act contained three important sections: 301, 302, and 305, which allowed medical professionals to procure an abortion only in two circumstances: when the act was necessary for the sake of the woman’s health and when the pregnancy resulted from sexual crime [2]. Inaccessibility to safe abortion services and legal threats against ending an unwanted pregnancy led pregnant women to seek ineffective and harmful alternatives [3]. In 2020, the Ministry of Health of Thailand conducted a reproductive health survey among women admitted to the gynecologic unit of public hospitals, 80% of respondents who underwent an unsafe abortion experienced serious complications [4].

As evidence indicates that maternal morbidity and mortality are higher in countries where abortion is restricted by law, the Thai government has worked to expand access to safe abortion services. [5]. As of February 5, 2021, the Constitutional Court of Thailand ordered the legislature to amend the criminal code to Sections 301 and 305. Justified situations for abortion are as follows: (1) continuation of pregnancy threatens a woman's physical or mental health, (2) fetal abnormalities that can cause disability in the newborn, (3) pregnancy resulting from sexual crime, (4) women with gestational age up to 12 weeks, and (5) women with gestational age between 12 and 20 weeks who insist on terminating their pregnancy after consulting a medical expert under the conditions set by the medical council of Thailand [6]. Furthermore, the cost of pregnancy termination and postabortion care has been included in the universal health coverage scheme for all Thai women.

Despite tremendous government efforts to prevent unsafe abortion, considerable barriers impede Thai women from obtaining safe and legal abortion care. Disparities in abortion services are due to health care providers' attitudes and distribution [7]. Thailand shares other nations' physician distribution disparities. All newly graduated medical students from the government-subsidized public university must complete a 3-year internship across Thailand to address a physician shortage in a remote area. Thus, medical students—the nation's future health care leaders—must learn about abortion care.

At Chulalongkorn University, medical students attend the 10-week Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB-GYN) rotations in their fourth year, of which the academic year begins in early May. The curriculum includes courses on pregnancy termination and abortion legislation taught by a designated faculty staff. In the department’s morning conferences, such as the monthly ethics session, abortion legislation is also discussed. Besides, medical students may hear about the amendment of abortion law through the press. This study was conducted among fifth-year medical students. A study on the recently amended abortion act and its implementation can greatly benefit learning outcomes assessment and provide information for improving medical training to prepare students for postgraduation employment. Thus, this study assessed medical students' knowledge, attitudes, and intended practices regarding the amended Thai abortion law.

2. Material and methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted. All fifth-year medical students, who had completed their OB-GYN rotations, were invited to participate in an electronic self-administered questionnaire. We invited all students, including those from a special recruitment program whose clinical rotations took place outside Bangkok. The study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture tools, hosted at Chulalongkorn University [8]. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University.

2.1. Recruitment

From June to July 2021, the authors reached out to every fifth-year student via Line application group “MDCU73,” the main communication channel among fifth-year medical students [9]. Participants who completed the survey received 100 Thai Baht (3 USD) as compensation for their time.

2.2. Questionnaire

Based on previously published studies, the authors designed a four-part, self-administered questionnaire [10]. In the first part of the questionnaire, demographic data of the participants were collected. The second part comprised knowledge-based questions on the amendment to Articles 301 and 305 of the criminal code of the Thai abortion law [6]. Each question had three possible answers (true/false/uncertain). The third part evaluated the attitude toward abortion using nine questions, where the 5-Likert scale answers ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The last part of the survey consisted of 13 questions regarding abortions that participants agreed to perform, which were scored similarly to the third part [10]. Face validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability were assessed prior to the fieldwork. The Cronbach’s alphas for knowledge, attitude, and practice were 0.7, 0.8, and 0.8, respectively. The test-retest reliability for all parts was 0.8 to 0.9.

2.3. Outcome variables

The primary outcome was the knowledge score, which was based on the number of correct answers regarding the Thai abortion law. Attitude statements were categorized into three groups: prochoice, prolife, and conditional agreement. The authors assigned a score of five for “strongly agree” in the prochoice and conditional agreement statements, while the authors scored one for “strongly disagree.” The opposite was true for the prolife statements. A mean score was then calculated from all three statements and used as a cutoff point for attitude favoring abortion. The willingness to perform an abortion was categorized into the following conditions: maternal physical and mental health, fetal status, sexual crime, and socioeconomic issues.

2.4. Statistical analysis

For the analysis, the authors used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) software, version 22 for Windows. The association between demographic variables and knowledge scores was assessed using a linear regression analysis. Variables with a “p-value” of <0.2 in the univariable analysis were used as potential confounders in multivariable logistic regression analysis [11]. The authors assessed the association between demographic variables and attitude on abortion using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

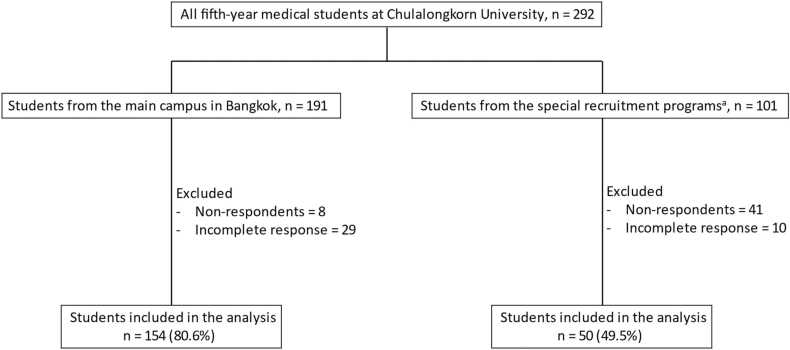

The authors distributed questionnaires to 292 fifth-year medical students electronically via a group chat using a mobile application (i.e., Line application) and received 243 responses. A final sample of 204 (70%) was included in the analysis: 154 (80.6%) from Chulalongkorn University and 50 (49.5%) from the special recruitment program, as shown in Figure 1. Participants’ demographics are presented in Table 1. Of all participants, male or transgender men respondents were 46.1%, and female or transgender women were 50%. The mean age ± standard deviation of the participants was 22 ± 0.7 years. Most participants defined themselves as Buddhist (87.3%). Only a few participants (6.9%) intended to pursue residency training in the OB-GYN.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 2021 fifth-year medical students Thailand, 2023 who were invited to participate and responded to the survey. aMedical students who enrolled in the special recruitment program have their clinical rotation outside Bangkok.

Table 1.

The demographics of Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 2021 fifth-year medical students Thailand, 2023 who participated in the survey.

| Variable, n (%) | N = 204 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male or transgender men | 94 (46.1) |

| Female or transgender women | 102 (50.0) |

| Othera | 8 (3.9) |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism | 178 (87.3) |

| Christianity | 8 (3.9) |

| None | 18 (8.8) |

| Recruitment program | |

| Chulalongkorn University | 154 (75.5) |

| Special recruitment programb | 50 (24.5) |

| Abortion cases encountered during 4th year medical students training | |

| 0 | 93 (45.6) |

| 1–2 | 71 (34.8) |

| >2 | 40 (19.6) |

| Childhood provinces (Region) (<12 years) | |

| Central | 135 (66.2) |

| Northern | 8 (3.9) |

| Southern | 18 (8.8) |

| Northeastern | 10 (4.9) |

| Eastern | 31 (15.2) |

| Western | 2 (1.0) |

| Which specialties are you considering for your future work? | |

| Obstetrics & Gynecology | 14 (6.9) |

| Internal Medicine | 29 (14.2) |

| Surgery | 30 (14.7) |

| Pediatrics | 11 (5.4) |

| Others | 39 (19.1) |

| Uncertain | 81 (39.7) |

Other included nonbinary, gender fluidity, agender, and those who prefer not to say.

Medical students who enrolled in the special recruitment program have their clinical rotation outside Bangkok.

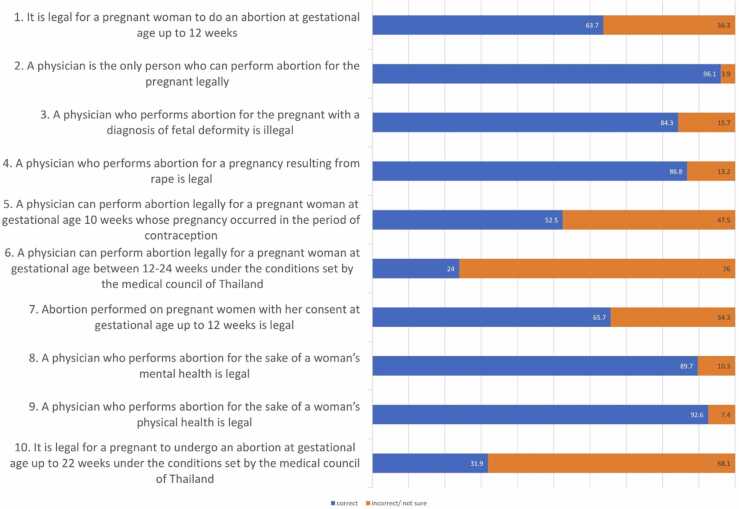

Figure 2 shows the percentage of participants who correctly answered the knowledge statements regarding the amendment of the criminal code of the Thai abortion law. The mean ± standard deviation knowledge score was 6.9 ± 1.8. Nearly half of the participants (45.6%) correctly answered at least 80% of the knowledge statements. However, only around 30% of the participants answered correctly on the gestational limit for second-trimester abortion (Statement number 6 and 10). Approximately two-thirds of the participants answered correctly on the gestational limit for first-trimester abortions (Statement number 1, 5, and 7). The demographics associated with a higher knowledge score were female/transgender women. Compared to male/transgender men, the mean difference in the knowledge score (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) among female/transgender women was 0.83 (0.33, 1.33) (p < 0.01) (Table 1 in Supplementary Material). Participants who wished to attend Obstetrics & Gynecology or Pediatrics residency program had a higher knowledge score than the other group. The mean difference (95% CI) was 0.72 (−0.02, 1.46) (p-value = 0.05) (Table 1 in Supplementary Material).

Fig. 2.

Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 2021 fifth-year medical students Thailand, 2023 responded to the knowledge statements regarding the amendment of the criminal code of Thai abortion laws, % (N = 204).

Table 2 presents the attitude of medical students toward abortion. Regarding the prochoice statements, most participants (86.8%) agreed that an abortion is a woman’s right. However, only 16.7% considered abortion beneficial in any circumstances. Regarding the conditional agreement statements, most participants agreed that abortion can be beneficial for all women in some situations (76%), and that abortion is acceptable after 12 weeks in some circumstances (83.9%). Regarding the prolife statements, most participants disagreed that abortion is the same as murder (72.5%), abortion is wrong (79.9%), and abortion is sinful (70.5%). The mean attitude score was 27 points, 9 being the lowest and 45 the highest. The authors categorized 114 participants, whose attitude score was greater than the mean, as participants who were in favor of abortion. Participants with a knowledge score of at least 80% tended to be in favor of abortion (Table 2 in Supplementary Material), compared with participants whose knowledge score was less than 80%.

Table 2.

Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 2021 fifth-year medical students’ Thailand, 2023 attitude toward abortion, n (%) (N = 204).

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion can be a good thing in any circumstances | 12 (5.9) | 22 (10.8) | 35 (17.2) | 76 (37.3) | 59 (28.9) |

| Abortion is woman’s right | 105 (51.5) | 72 (35.3) | 13 (6.4) | 7 (3.4) | 7 (3.4) |

| Abortion is acceptable past 12+ weeks in any circumstances | 14 (6.9) | 37 (18.1) | 60 (29.4) | 69 (33.8) | 24 (11.8) |

| Abortion can be a good thing for some women in all situations | 37 (18.1) | 90 (44.1) | 45 (22.1) | 24 (11.8) | 8 (3.9) |

| Abortion can be a good thing for all women in some situations | 75 (36.8) | 80 (39.2) | 23 (11.3) | 17 (8.3) | 9 (4.4) |

| Abortion is acceptable past 12+ weeks in some circumstances | 56 (27.5) | 115 (56.4) | 20 (9.8) | 8 (3.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Abortion is the same as murder | 4 (2.0) | 12 (5.9) | 40 (19.6) | 77 (37.7) | 71 (34.8) |

| Abortion is wrong | 2 (1.0) | 11 (5.4) | 28 (13.7) | 82 (40.2) | 81 (39.7) |

| Abortion is sinful | 6 (2.9) | 17 (8.3) | 37 (18.1) | 57 (27.9) | 87 (42.6) |

Table 3 shows medical students’ intended practice toward abortion services. Most medical students agreed/strongly agreed to perform an abortion under the following conditions: if the fetus had a serious anomaly that makes it nonviable (95.6%), the woman was pregnant as a result of rape (93.2%), the pregnant woman had a serious physical condition (92.1%), and the pregnant woman had a serious mental disorder (89.2%). According to the survey responses, medical students least agreed to perform an abortion owing to the pregnant woman’s socioeconomic factors. Participants with a knowledge score of at least 80% were likely to agree to perform an abortion (Table 3 in Supplementary Material), compared with those whose knowledge score was less than 80%. Those with an attitude score higher than the mean tended to agree to perform an abortion (Table 3 in Supplementary Material), compared with participants whose attitude score was lower than the mean.

Table 3.

Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 2021 fifth-year medical students’ Thailand, 2023 intended practice toward abortion services, n (%) (N = 204).

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The pregnant woman has a serious physical disease(s) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 12 (5.9) | 87 (42.6) | 101 (49.5) |

| The pregnant woman has HIV/AIDS | 16 (7.8) | 63 (30.9) | 50 (24.5) | 49 (24) | 26 (12.7) |

| The pregnant woman has a serious mental disorder(s) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.4) | 12 (5.9) | 91 (44.6) | 91 (44.6) |

| The fetus has a serious defect that makes it nonviable | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.9) | 51(25) | 144 (70.6) |

| The fetus has a serious defect but will be viable and being handicapped | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2) | 18 (8.8) | 88 (43.1) | 91 (44.6) |

| The woman has become pregnant as a result of being raped | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1) | 9 (4.4) | 55 (27) | 135 (66.2) |

| The woman has become pregnant as a result of incestuous pregnancy (incest—sexual intercourse between two members of the same family) | 8 (3.9) | 22 (10.8) | 75 (36.8) | 58 (28.4) | 41 (20.1) |

| The pregnant woman is under age 20 | 14 (6.9) | 46 (22.5) | 58 (28.4) | 60 (29.4) | 26 (12.7) |

| The pregnant woman is under age 15 | 7 (3.4) | 23 (11.3) | 38 (18.6) | 84 (41.2) | 52 (25.5) |

| The man involved in the pregnancy will not support the woman in having a baby | 20 (9.8) | 46 (22.5) | 64 (31.4) | 50 (24.5) | 24 (11.8) |

| The man involved in the pregnancy will not marry the woman | 28 (13.7) | 57 (27.9) | 70 (34.3) | 30 (14.7) | 19 (9.3) |

| The woman/couple feels they already have enough children | 29 (14.2) | 58 (28.4) | 36 (17.6) | 53 (26) | 28 (13.7) |

| The woman has become pregnant as a result of contraceptive failure | 10 (4.9) | 25 (12.3) | 31 (15.2) | 82 (40.2) | 56 (27.5) |

4. Discussion

Almost half of the medical students (45.6%) completed the knowledge section, with a good total knowledge score (≥80%). The most incorrectly answered questions were those about the gestational limits of abortion, which is a major amendment to Thai abortion law. The lack of knowledge regarding the upper gestational limit for abortion suggested that medical students’ knowledge of the amended Thai abortion law was limited. The findings of our study should encourage medical schools to emphasize the revised Thai abortion law in their OB-GYN curriculum. Female/transgender women had a significantly higher knowledge score than male/transgender men. However, this small effect size might not contribute to the clinical differences. The authors aimed to explore the different knowledge scores between participants who wished to attend OB-GYN or Pediatrics residency programs with others. However, the effect size was small and not statistically significant.

Regarding attitude toward abortion, medical students tended to agree more with conditional statements than with prochoice statements. Adding some conditions to the prochoice statements might make the option more acceptable. Furthermore, medical students highly disagreed with prolife statements. Our results were consistent with the study conducted by Baba et al. [10], which stated that most students agreed or strongly agreed that abortion could be beneficial for some women in certain situations. Participants with higher knowledge scores (≥80%) had attitude favoring abortion. The increasing knowledge scores associated with a positive attitude toward abortion revealed among medical students in our study should be interpreted with caution. Fifth-year medical students have never worked in a genuine clinical context where peers’ attitudes, prejudice, and social stigma have a substantial impact on their abortion attitudes and willing to practice. Santiya et al. [12] discovered that after the training course, attitudes toward induced abortion improved in the training context. However, in 2006 Bunnag et al. [13] examined the knowledge and attitude of 68 obstetrician-gynecologists and found that only 23% understood Thai abortion law. Knowledge of Thai abortion law was only weakly correlated with abortion attitude (r = 0.36, p-value = 0.002). Further research is required to confirm our findings.

In the intended practice session, the situations in which medical students mostly agreed to perform an abortion were fetal anomalies, followed by sexual assault, maternal disease, and socioeconomic issues. Most participants agreed to perform an abortion in situations where the lives of the mother and the fetus were seriously threatened, compared to other situations. Medical students with higher knowledge scores were more willing to perform abortions. This is consistent with a study conducted by Madziyire et al. [14], which suggests that insufficient knowledge of health care providers can impede safe abortion access for women. It could be implied that students with higher knowledge scores might be more confident with following the laws and regulations for providing safe abortion services. It is clear that attitude favoring abortion influences students’ intended practice toward abortion services. Encouraging medical students to be more informed about abortion may have a positive impact on their future medical practice.

The enormous actions by the Thai government to prevent maternal mortality from unsafe abortion will not be accomplished without the cooperation of health care providers. As shown by other nations, a lack of providers hinders safe abortion care even after legislative reform. Ethiopian health care workers struggle to balance attitude and duty [15]. The stigma associated with abortion providers and their social isolation hinder them from providing safe abortion services [16]. In Chile, a scarcity of providers restricts access to abortion services. These examples show how providers’ attitudes affect safe abortion care [17]. A survey from the members of the Referral System for Safe Abortion in Thailand states that health care providers’ attitude, especially senior medical administrators, significantly shape the availability of abortion in the clinic or hospital setting [7]. In Thailand, hospital or clinic directors may control institutional policies and the availability of abortion medicines or equipment, which considerably contribute to abortion provision. The Thai government must undertake additional measures to address this issue.

The authors conducted an electronic self-administrated survey to mitigate information bias in evaluating attitude on abortion and ensure that all participants were anonymous. Thanks to Baba et al. [10], the authors were granted permission to modify a published questionnaire for use in our study. The authors decided to use the English version of the questionnaire as Chulalongkorn Medical School requires medical students to read the English version of medical textbooks. Therefore, the English version of the questionnaire should not have caused any language issues.

Our study included medical students from only one institution; therefore, the generalizability of our results was limited. However, the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, is one of the largest medical schools in Thailand that trains more than 300 medical students each year. We conducted this survey a few months after the Thai abortion law changed in February 2021, when all students had finished their OB-GYN rotations. However, in February 2019, the Constitutional Court ordered the government to amend abortion laws after the arrest of an obstetrician who provided safe abortions in 2018. This case was widely publicized and discussed in most academic conference ethics or professional development sessions.

To provide greater generalizability of the results, further research should focus on including participants from different backgrounds, such as religious diversity, as well as to involve students from a variety of medical schools in Thailand. Qualitative research, including in-depth interviews, might be more appropriate to explore the association between attitude and intended practices toward abortion.

Almost half of the students obtained good knowledge scores on the amended Thai abortion law. However, most participants were unaware about the change of the upper limit of gestational age for legal abortion, which is a crucial point of the amendment. The results should encourage medical schools to emphasize the revised Thai abortion law in the OB-GYN curriculum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Finley Baba at the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, Oakland, CA, USA for her generosity for granting permission to modify a published questionnaire for use in this study. We acknowledge Dr. Yuda Chongpison and Mr. Wasan Panyasang at the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, for their statistical advice. We also would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Family Planning and Reproductive Health Unit; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; and Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.conx.2023.100091.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Boonchalermvipas S. The Thai legal history (in Thai) 7th ed. Winyuchon Publication Hous; Bangkok: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niyomthai A. Abortion law: abortion act. The Secretariat Senate Julniti; 2011. pp. 167–176.〈https://www.senate.go.th/assets/portals/93/fileups/272/files/S%E0%B9%88ub_Jun/10reform/reform16.pdf〉 (accessed August 02, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belton S. Borders of fertility: unplanned pregnancy and unsafe abortion in Burmese women migrating to Thailand. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(4):419–433. doi: 10.1080/07399330601180081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bureau of Reproductive Health [Internet]. Thailand reproductive health database; c2021. 〈https://rhdata.anamai.moph.go.th〉. [cited December 6, 2021].

- 5.Chemlal S., Russo G. Why do they take the risk? A systematic review of the qualitative literature on informal sector abortions in settings where abortion is legal. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0751-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal Thai government gazette (in Thai) An act amending the penal code (No. 28) BE 2654. 2022. 〈http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2564/A/010/T_0001.PDF〉 (accessed August 02, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnott G., Sheehy G., Chinthakanan O., Foster A.M. Exploring legal restrictions, regulatory reform, and geographic disparities in abortion access in Thailand. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Line: Line software. Version 11.13.0 [mobile application software] 2000. 〈http://itunes.apple.com〉 (cited December 6, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baba C.F., Casas L., Ramm A., Correa S., Biggs M.A. Medical and midwifery student attitudes toward moral acceptability and legality of abortion, following decriminalization of abortion in Chile. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2020;24 doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2020.100502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson B. Stepwise regression and stepwise discriminant analysis need not apply here: a guidelines editorial. Educ Psychol Meas. 1995;55:525–534. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055004001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanitya R., Marshall A.I., Saengruang N., Julchoo S., Sinam P., Suphanchaimat R., et al. Healthcare providers’ knowledge and attitude towards abortions in Thailand: a pre-post evaluation of trainings on safe abortion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3198. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunnag A. Attitude of the Ob-Gyn doctors toward Thai Abortion Law and Solution available for Thai Abortion Law: a case study in Pramongkutklao and Rajavithi Hospitals. RTA Med J. 2006;59:219–230. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madziyire M.G., Moore A., Riley T., Sully E., Chipato T. Knowledge and attitudes towards abortion from health care providers and abortion experts in Zimbabwe: a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:94. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.94.18107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewnetu D.B., Thorsen V.C., Solbakk J.H., Magelssen M. Still a moral dilemma: how Ethiopian professionals providing abortion come to terms with conflicting norms and demands. BMC Medical Ethics. 2020;21(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12910-020-0458-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feyssa M.D., Gebru S.K. Liberalizing abortion to reduce maternal mortality: expanding access to all Ethiopians. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12978-022-01457-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maira G., Casas L., Vivaldi L. Abortion in Chile: the long road to legalization and its slow implementation. Health Hum Rights. 2019;21(2):121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material