Abstract

Magnesium is an essential macronutrient for plant photosynthesis, and in response to Mg deficiency, dicots appear more sensitive than monocots. Under Mg deficiency, we investigated the causes of differing photosynthetic sensitivities in a dicot and a monocot species. Rice (Oryza sativa L.) and cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) were grown in hydroponic culture to explore their physiological responses to Mg deficiency stress. Both Mg-deficient rice and cucumber plants exhibited lower biomass, leaf area, Mg concentration, and chlorophyll content (Chl) compared with Mg-sufficient plants. However, a more marked decline in Chl and carotenoid content (Car) occurred in cucumber. A lower CO2 concentration in chloroplasts (C c) was accompanied by a decrease in the maximum rate of electron transport (J max) and the maximum rate of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylation (V cmax), restricting CO2 utilization in Mg-deficient plants. Rice and cucumber photorespiration rate (P r) increased under Mg deficiency. Additionally, for cucumber, Car and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) were reduced under lower Mg supply. Meanwhile, cucumber Mg deficiency significantly increased the fraction of absorbed light energy dissipated by an additional quenching mechanism (Φf,D). Under Mg deficiency, suppressed photosynthesis was attributed to comprehensive restrictions of mesophyll conductance (g m), J max, and V cmax. Cucumber was more sensitive to Mg deficiency than rice due to lower NPQ, higher rates of electron transport to alternative pathways, and subsequently, photooxidation damage.

Keywords: magnesium, rice, cucumber, photosynthesis, photoprotection, NPQ

Introduction

Magnesium (Mg) is vital for plant growth and reproductive success as it is an irreplaceable component of cells and tissues (Zhao et al., 2012), with a total Mg cellular concentration of 15-25 mM with 15%–20% bound to chlorophyll and free magnesium concentration frequently at less than the millimolar level. Mg mainly participates in photosynthesis, energy metabolism, and nucleic acid and protein synthesis. Moreover, some Mg is allocated to the cell walls by combining with pectin (Cowan, 2002; Shaul, 2002). Because of cation antagonism, Mg2+ plant uptake can be strongly depressed by NH4 + and K+. Furthermore, an unbalanced K/Mg ratio inhibits photosynthesis and N metabolism (Xie et al., 2021). Therefore, excessive chemical fertilizer applications with low Mg supply increase Mg deficiency (Wilkinson et al., 1990; Gransee and Fuhrs, 2013). Plants require enough Mg to allow biomass formation and carbohydrate partitioning; many studies have shown lower dry matter of various plants under Mg deficiency (Ding et al., 2006; Ceylan et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Trankner et al., 2016). The root-to-shoot ratio can also be downregulated during the early stage of Mg deficiency (Fischer and Bremer, 1993), as Mg is necessary for sucrose phloem loading. Mg deficiency suppresses crop yields by reducing plant photosynthetic rate and carbohydrate transportation, ultimately restricting agricultural production (Farhat et al., 2016).

Mg in plants is preferentially allocated in the chloroplasts for photosynthetic processes (Chen et al., 2018). Mg deficiency reduces the photosynthetic rate through light reaction and CO2 assimilation since Mg is not only a chlorophyll structural component but also the activator of numerous photosynthetic enzymes (Schneider et al., 1992). Chlorophyll acts in pigment–protein complexes to harvest photons in photosystems II and I (PSII and PSI) (Jansson, 1994), but Mg deficiency restrains chlorophyll synthesis and promotes chlorophyll degradation (Hermans et al., 2010), subsequently reducing the photosynthetic electron transport rate (J) (Laing et al., 2000). Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase (Rubisco), a dominant enzyme in CO2 assimilation, is regulated by Mg concentration in chloroplast stroma (Lorimer et al., 1976). Additionally, reduced CO2 diffusion leads to downregulated chloroplast CO2 concentration (Fischer and Bremer, 1993; Hariadi and Shabala, 2004), which affects the carboxylation reaction rate. Mg is also involved in photoprotection. For example, the maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (F v/F m) declined in various plant species under Mg-deficient conditions (Laing et al., 2000; Hariadi and Shabala, 2004; Yang et al., 2012). Reduced F v/F m means photoinhibition occurs under Mg deficiency, which is induced by failed D1 protein repair in the PSII reaction center (Traenkner et al., 2018).

Interveinal chlorosis in the leaves may be attributed to Mg-deficient-induced photooxidation damage. Once photosynthesis is suppressed, the flow of electrons transferred to O2 increases to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radicals (O2 ·−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH·) (Cakmak and Kirkby, 2008). Abiotically stressed plants inevitably absorb excessive light energy and, therefore, have evolved several physiological processes to minimize injury, such as strengthening the photorespiration rate (P r) and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (Demmig-Adams and Adams, 2002); elevating the electron transfer rates to some additional/alternative electron transport pathways (Asada, 1999; Cournac et al., 2000); enhancing the antioxidative defense system by increasing the activities of enzymes including SOD, CAT, and POD (Ding et al., 2008); and promoting the D1 protein turnover (a core component of the PSII reaction center) resynthesis (Zhang et al., 2000). However, the defense system is destroyed under magnesium deficiency, and enhanced ROS contributes to lipid peroxidation and chlorophyll degradation (Wingler et al., 2005).

Structures and intracellular characters vary between monocots and dicots. For example, a particular cell wall structure is found in commelinid monocots which possess less pectin in cell walls than non-commelinid monocots and dicots (White et al., 2018). Different pectin content between plant groups might affect Mg allocation at the cellular level, as some Mg is bound to pectin (Marschner, 1995). Dicots appear more sensitive than monocots in response to Mg deficiency. Meta-analysis has demonstrated that critical Mg concentrations for net photosynthetic rate (P n) in monocots are lower than in dicots (Hauer-Jakli and Trankner, 2019). Wang et al. (2020b) found that different agronomic efficiencies of Mg fertilizers across crop species were due to variations in Mg uptake or utilization; vegetables (dicots) were always the most responsive to Mg applications, and cereals (monocots) the least. However, although these findings have proven sensitivity differences between dicots and monocots, the inherent cause is still unknown.

In the present study, rice and cucumber were grown in hydroponic culture to compare their physiological responses to magnesium deficiency. In a preliminary experiment, we found that cucumber leaves developed necrosis, while rice leaves stayed green while being supplied with low Mg concentration (0.01 mM, data not shown). Our primary objectives were to 1) compare the physiological and photosynthetic differences between rice and cucumber under Mg deficiency, 2) reveal the underlying mechanisms of photosynthesis downregulation under Mg deficiency, and (3) investigate the cause(s) of differing sensitiveness between the two plant species. Our results will provide insight into the mechanisms underlying the effects of Mg deficiency on plant growth and photosynthesis and increase our knowledge of specific Mg nutrient management on different crops, which is vital to maintain sustainable agricultural development.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and culture conditions

Rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Shanyou 63) and cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. cv. Jinchun 4) were grown in a greenhouse. The greenhouse has a stable environment, provided with a 14-h photoperiod, a constant relative humidity of 40%∼60%, a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 400 μmol m−2 s−1, and a day/night temperature of 30°C/25°C. Rice seeds were sterilized in 10% H2O2 for 1 h and then germinated in moist gauze. Cucumber seeds were soaked in water for 1 h and germinated in sterile quartz sand. After a preculture for 2 weeks, the uniform seedlings with 3 visible leaves were transferred to 6.5 L containers with a quarter-strength nutrient solution for the first 4 days, then transferred to a half-strength nutrient solution for another 4 days before providing a full-strength nutrient solution. Rice and cucumber seedlings were then supplied with two Mg-deficient treatments (Mg0.01, 0.01 mmol L−1; Mg0.1, 0.1 mmol L−1) and one Mg-sufficient treatment (Mg1, 1 mmol L−1), and Mg was provided by MgSO4·7H2O. The nutrient composition of the full-strength culture solutions was as follows: 2.86 mM of N provided by equimolar amounts of (NH4)2SO4 and Ca(NO3)2, 1.43 mM of Ca provided by equimolar amounts of Ca(NO3)2 and CaCl2, 0.32 mM of P and 1.03 mM of K provided by KH2PO4 and K2SO4, 35.8 μM of Fe-EDTA, 9.10 μM of MnCl2·4H2O, 0.52 of μM (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 18.5 μM of H3BO3, 0.15 μM of ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.16 μM of CuSO4·5H2O, and 0.1 μM of Na2SiO3·9H2O. Dicyandiamide was added to each nutrient solution to prevent ammonium oxidation. The nutrient solutions were renewed every 4 days, and the pH was adjusted to 5.5 ± 0.1 every day with HCl (1 M) and NaOH (1 M).

Gas exchange and photochemical measurements

Gas exchange and photochemical measurements were determined on the second fully expanded leaves by a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with an integrated fluorescence leaf chamber. Four leaves of each treatment were selected to measure from 9:00 to 14:00, set with a PPFD of 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1, a CO2 concentration of 400 μmol mol−1, a relative humidity of 40%~60%, and a leaf temperature of 30°C. The gas exchange parameters, steady-state fluorescence (F s), and maximum fluorescence (F′m) were recorded when stability was achieved after equilibration (approximately 20 min after clamping the leaf). The minimal level of fluorescence (F o) and the maximal fluorescence level (F m) of the leaves were measured from 2:00 to 3:00 after dark adaption sufficiently.

The actual photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (ΦPSII), the proportion of thermally dissipated energy through NPQ (ΦNPQ), the fraction of absorbed light energy dissipated by additional quenching mechanism (Φf,D) (Hendrickson et al., 2004), the electron transport rate (J), and the excess of photosynthetic linear electron transport not used for carbon assimilation (J excess) were calculated as follows (Streb et al., 2005; Savitch et al., 2010):

Where α leaf is the leaf absorbance and β reflects the partitioning of the absorbed quanta between PSII and PSI, and R d is the day respiration rate. Light response curves and ΦPSII were measured in gas (98% N2 and 2% O2) at nine levels of PPFD (2,000, 1,500, 1,000, 500, 200, 150, 100, 50, 0 μmol m−2 s−1) by the portable photosynthesis system. The slope of the relationship between ΦPSII and 4ΦCO2 (the quantum efficiency of CO2 uptake) is calculated to be the value of αleaf × β (Valentini et al., 1995).

The variable J method proposed by Harley et al. (1992). was used to calculate mesophyll conductance (g m) and CO2 concentration in chloroplasts (C c) as follows:

The CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration (Γ*) and R d were measured through the Laisk method, as reported by Brooks and Farquhar (1985).

The maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (F v/F m) and the NPQ were computed as follows:

After the above measurements of photosynthetic parameters, three rice and three cucumber leaves were selected to conduct light and CO2 response curves. Relative humidity and leaf temperature inside the measurement chamber were kept as described before. Light response curves were conducted by adjusting PPFD to nine levels (2,000, 1,500, 1,000, 500, 200, 150, 100, 50, 0 μmol m−2 s−1) at a constant CO2 partial pressure (400 μmol mol−1). For CO2 response curves, measurements were determined by adjusting CO2 concentrations to 11 levels (400, 300, 200, 150, 100, 50, 400, 600, 800, 1,000, and 1,200 μmol mol−1) at a constant PPFD (1,500 μmol m−2 s−1). All the gas exchange parameters of the leaves were recorded when stability was achieved at the corresponding ambient environments. The slope of the linear part of the light response curve (0, 50, 100, 150, 200 μmol m−2 s−1) and the CO2 response curve (50, 100, 150, 200 μmol mol−1) was calculated as apparent quantum yield (α) and carboxylation efficiency (CE). The maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (V cmax) and the maximum rate of RuBP regeneration (J max) were evaluated by the CO2 response curve fitting model provided by Sharkey et al. (2007).

CO2 concentration in the chloroplasts at which the transition from Rubisco to RuBP regeneration limitation occurs (C trans) was calculated as follows:

Rubisco kinetics parameters were according to Sharkey et al. (2007): K c = 27.24 Pa, K o = 16.58 kPa, and O = 21 kPa.

Photorespiration rate measurement

Photorespiration rate measurements were also determined on the second fully expanded leaves by a portable photosynthesis system, which was connected to a gas containing 98% N2 and 2% O2; FFPD, CO2 concentration, relative humidity, and leaf temperature were maintained as described in the measurement of P n, and the net photosynthetic rate in 2%O2 (P n2%O2) was recorded when stability was achieved after equilibration.

The photorespiration rate (P r) was computed as follows:

Dynamic measurements of photosynthetic parameters

Considering that the appearance of Mg-deficient symptoms in the plant leaves was a slow process and the leaves of cucumber became necrotic gradually, a transient measurement of photosynthesis could not exhibit the conditions of the leaves in this process; hence, the uppermost expanded leaves were selected to conduct a 7-day dynamic measurement. P n, F v/F m, and NPQ were measured every 2 days as described before.

Determination of chlorophyll, carotenoid, and Mg contents and biomass

After the measurements of photosynthetic parameters, 0.2 g of fresh second fully expanded leaves were cut into little pieces and extracted with 20 ml of alcohol (95%, v/v). After a 24-h extraction in a dark place, the absorbance of the extract was measured by a spectrophotometer at 665, 649, and 470 nm, and then the chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were calculated from those three absorbances. Another part of these leaves was used to determine leaf mass per area (LMA) and Mg contents. Leaves were shot for leaf area estimation, and LMA was calculated by dividing leaf dry matter by leaf area concentrated. Fresh leaves were dried under 80°C to a constant weight, then weighed and digested in mixed HNO3 and HClO4. The concentrations of Mg were determined by ICP-OES (Agilent 710, Agilent Technologies, USA). Four plants in each treatment were also dried under 80°C to constant weight to determine biomass.

Determination of the activities of ROS-scavenging enzymes

Fresh second fully expanded leaf (0.2 g) was precooled by liquid nitrogen and ground with 2 ml of cold phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8) containing insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone (1%) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (0.2 mM). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min at 4°C, and then the supernatant was collected for enzymatic activity analysis. SOD, POD, and CAT activities were determined by the methods described by Wang et al. (2020a).

Statistical analysis

ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted on all measured parameters to identify the difference between Mg treatments using SPSS 18.0 software. Graphics and regression analysis were conducted using OriginPro 8.5 software and Adobe Illustrator 2020.

Results

Rice and cucumber physiological traits

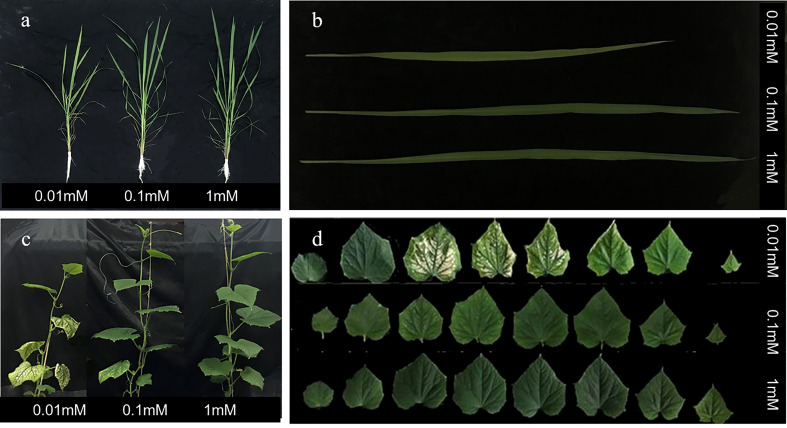

Rice and cucumber plants under 0.01 mM of Mg were seriously inhibited physiologically ( Figures 1A, C ). Cucumber developed typical Mg-deficient symptoms (interveinal chlorotic areas) on the middle leaves, and in magnesium-deficient rice plants, the leaf area was inhibited, while leaf chlorosis was not observed ( Figures 1B, D ).

Figure 1.

Morphological aspect of rice (A, B) and cucumber (C, D) under nutrient solution conditions at 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM of Mg; rice and cucumber were captured on 25 and 15 days after the onset of treatment.

Most of the physiological traits of rice and cucumber declined as Mg availability was downregulated, and cucumber plants were more sensitive than rice plants ( Table 1 ). Mg concentration was the most affected trait, with an 88.6% and 72.4% decrease in rice and cucumber, respectively, at 0.01 mM of Mg compared with 1 mM of Mg. Cucumber chlorophyll and carotenoid contents (Chl and Car) significantly decreased even at 0.1 mM of Mg ( Table 1 ). Compared with the 1-mM Mg treatment, rice and cucumber Chl decreased by 28.8% and 59.5%, respectively, under the 0.01-mM treatment. Mg deficiency significantly decreased cucumber Car and increased cucumber LMA, while no significant difference was observed in rice Car and LMA ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Effects of Mg supply on the morphological and physiological traits of rice and cucumber.

| Species | Treatment | Biomass (g plant−1) | Area (cm2 plant−1) | LMA (g m−2) | Chl (mg g−1 FW) | Car (mg g−1 FW) | Mg concentration (mg g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 0.01 mM | 1.46 ± 0.16b | 354 ± 43b | 28.4 ± 1.8a | 2.15 ± 0.17b | 0.36 ± 0.03a | 0.93 ± 0.05c |

| 0.1 mM | 1.67 ± 0.32ab | 427 ± 66ab | 27.7 ± 0.9a | 2.65 ± 0.15a | 0.39 ± 0.02a | 4.40 ± 0.10b | |

| 1 mM | 1.80 ± 0.18a | 445 ± 43a | 27.9 ± 3.5a | 2.86 ± 0.07a | 0.38 ± 0.02a | 8.10 ± 0.50a | |

| Cucumber | 0.01 mM | 0.88 ± 0.0 b | 322 ± 51b | 20.7 ± 2.6b | 0.79 ± 0.13c | 0.15 ± 0.02c | 1.41 ± 0.35c |

| 0.1 mM | 1.05 ± 0.10a | 353 ± 66ab | 17.1 ± 1.3a | 1.69 ± 0.14b | 0.30 ± 0.02b | 2.07 ± 0.23b | |

| 1 mM | 1.15 ± 0.13a | 434 ± 72a | 15.1 ± 1.2a | 1.95 ± 0.11a | 0.33 ± 0.02a | 5.10 ± 0.41a |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four replicates for biomass, area, LMA, Chl, Car, and Mg concentration. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) between three Mg treatments.

Area, leaf area; LMA, leaf mass per area; Chl, chlorophyll content; Car, carotenoid content.

Photosynthesis response to irradiation and CO2 concentration

Rice and cucumber P n declined gradually under increased Mg-deficient conditions ( Table 2 ). Plants of both species grown in 0.01 mM of Mg exhibited 52.8% and 53.1% lower P n than in 1 mM of Mg. Other photosynthetic parameters (g s, g m, and C c) were also limited with increasing Mg deficiency severity, while for C i, no significant difference was observed in 0.01 mM, compared with 1 mM Mg treatments ( Table 2 ). Cucumber was more sensitive than rice under mild Mg deficiency (0.1 mM of Mg), while photosynthetic response under severe Mg deficiency (0.01 mM of Mg) was the same for both species.

Table 2.

Effects of Mg supply on photosynthetic parameters of rice and cucumber.

| Species | Treatment | P n (μmol m−2 s−1) | g s (mol·m−2·s−1) | g m (mol m−2 s−1) | C i (μmol mol−1) | C c (μmol mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 0.01 mM | 11.5 ± 0.7c | 0.236 ± 0.046b | 0.072 ± 0.002c | 304 ± 15a | 143 ± 18b |

| 0.1 mM | 20.7 ± 0.8b | 0.521 ± 0.048a | 0.157 ± 0.007b | 315 ± 8a | 183 ± 7a | |

| 1 mM | 24.4 ± 1.7a | 0.552 ± 0.078a | 0.200 ± 0.014a | 308 ± 7a | 186 ± 10a | |

| Cucumber | 0.01 mM | 8.4 ± 0.9c | 0.214 ± 0.039b | 0.048 ± 0.008c | 318 ± 11a | 143 ± 8b |

| 0.1 mM | 15.2 ± 1.8b | 0.292 ± 0.080b | 0.110 ± 0.005b | 290 ± 18b | 152 ± 3b | |

| 1 mM | 17.9 ± 0.9a | 0.432 ± 0.033a | 0.130 ± 0.009a | 311 ± 7ab | 173 ± 8a | |

| Rice | *** | ** | *** | ns | ** | |

| Cucumber | ** | ** | ** | * | *** |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four replicates for P n, g s, g m, C i, and C c. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) between three Mg treatments. In the last two lines, the significance of each correlation between Mg concentration and photosynthetic parameters was represented by asterisks: *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01; ***P< 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

P n, net photosynthetic rate; g s, stomatal conductance; g m, mesophyll conductance; Ci, intercellular CO2 concentration; C c, CO2 concentration in chloroplasts.

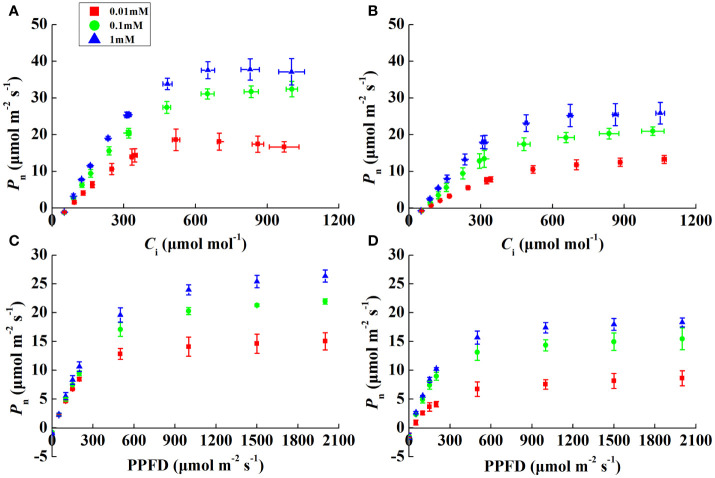

P n increased rapidly, peaked, and then stabilized with increasing irradiance and CO2 concentrations ( Figures 2A–D ). The α of both species was alike except for 0.01 mM Mg treatment, where it decreased by 20.7% and 53.4% in rice and cucumber, respectively, under 0.01 mM of Mg compared with 1 mM of Mg ( Table 3 ). Despite α, other rice and cucumber biochemical parameters (CE, V cmax, and J max) significantly decreased under Mg deficiency and were consistent among the two plant species. Cucumber was more sensitive to Mg deficiency than rice, with wider disparities in J max/V cmax and C trans between 0.1 and 1 mM Mg treatments.

Figure 2.

CO2 (A, B) and light (C, D) response curves showing the net photosynthetic rate (P n) in rice and cucumber leaves under Mg-deficient (0.01, 0.1 mM) and sufficient Mg (1 mM) supply treatments. Values represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates.

Table 3.

Effects of Mg supply on photosynthetic parameters of light and CO2 response curves.

| Species | Treatment | α | CE | V cmax (μmol m−2 s−1) | J max (μmol m−2 s−1) | J max/V cmax | C trans (μmol mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 0.01 mM | 0.046 ± 0.001b | 0.064 ± 0.007c | 53.0 ± 7.0b | 88 ± 12c | 1.65 ± 0.01b | 432 ± 3b |

| 0.1 mM | 0.051 ± 0.001b | 0.096 ± 0.007b | 85.3 ± 8.4a | 154 ± 9b | 1.81 ± 0.09a | 505 ± 46a | |

| 1 mM | 0.058 ± 0.005a | 0.118 ± 0.003a | 99.4 ± 6.4a | 180 ± 15a | 1.81 ± 0.03a | 508 ± 17a | |

| Cucumber | 0.01 mM | 0.027 ± 0.005c | 0.034 ± 0.004c | 38.3 ± 2.1c | 63 ± 6c | 1.64 ± 0.04b | 426 ± 16b |

| 0.1 mM | 0.051 ± 0.000b | 0.060 ± 0.006b | 58.9 ± 2.0b | 99 ± 5b | 1.69 ± 0.04b | 446 ± 17b | |

| 1 mM | 0.058 ± 0.004a | 0.081 ± 0.003a | 69.3 ± 5.7a | 122 ± 13a | 1.76 ± 0.03a | 481 ± 15a | |

| Rice | ** | *** | *** | *** | * | * | |

| Cucumber | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates for α, CE, V cmax, J max, J max/V cmax, and C trans. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) between three Mg treatments. In the last two lines, the significance of each correlation between Mg concentration and photosynthetic parameters was represented by asterisks: *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01; ***P< 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

α, apparent quantum yield; CE, carboxylation rate; V cmax, the maximum Rubisco carboxylation rate; J max, the maximum rate of electron transport; C trans, CO2 concentration in chloroplasts at which the transition from Rubisco to RuBP regeneration limitation occurs.

J and ΦPSII significantly declined with Mg deficiency regardless of plant species ( Table 4 ). F v/F m was significantly affected only in cucumber under 0.01 mM Mg treatment, where it decreased by 11.5%. Additionally, rice and cucumber plant NPQ under severe Mg-deficient treatment (0.01 mM of Mg) increased by 14.0% and decreased by 37.8%, respectively. There was no difference in rice αleaf × β between Mg-deficient and Mg-sufficient leaves, while cucumber αleaf × β decreased by 18.4% in 0.01 mM Mg treatment. For ΦNPQ, rice and cucumber showed different responses to Mg deficiency, while cucumber Φf,D increased by 40.4% under 0.01 mM Mg treatment. J excess declined significantly only in rice under Mg deficiency, and rice and cucumber plant J excess/J under 0.01 mM of Mg increased by 27.9% and 39.9%, respectively.

Table 4.

Effects of Mg supply on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of rice and cucumber.

| Species | Treatment | J (μmol m−2 s−1) | F v/F m | NPQ | α leaf × β | ΦPSII | ΦNPQ | Φf,D | J excess (μmol m−2 s−1) | J excess/J (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 0.01 mM | 97 ± 12c | 0.802 ± 0.003a | 1.788 ± 0.084a | 0.483 ± 0.024a | 0.159 ± 0.028c | 0.539 ± 0.012a | 0.302 ± 0.018ab | 50 ± 9b | 51 ± 3a |

| 0.1 mM | 140 ± 6b | 0.800 ± 0.009a | 1.490 ± 0.109b | 0.484 ± 0.020a | 0.220 ± 0.009b | 0.466 ± 0.017b | 0.313 ± 0.013a | 56 ± 3b | 40 ± 1b | |

| 1 mM | 171 ± 12a | 0.808 ± 0.001a | 1.569 ± 0.113b | 0.490 ± 0.029a | 0.261 ± 0.012a | 0.451 ± 0.020b | 0.288 ± 0.009b | 68 ± 6a | 40 ± 2b | |

| Cucumber | 0.01 mM | 84 ± 7b | 0.707 ± 0.019b | 0.952 ± 0.056b | 0.413 ± 0.042b | 0.132 ± 0.012b | 0.423 ± 0.010b | 0.445 ± 0.018a | 49 ± 5a | 58 ± 2a |

| 0.1 mM | 117 ± 14a | 0.796 ± 0.003a | 1.464 ± 0.080a | 0.491 ± 0.040a | 0.183 ± 0.021a | 0.485 ± 0.022a | 0.332 ± 0.007b | 53 ± 7a | 46 ± 1b | |

| 1 mM | 126 ± 10a | 0.799 ± 0.002a | 1.531 ± 0.051a | 0.506 ± 0.018a | 0.198 ± 0.016a | 0.485 ± 0.011a | 0.317 ± 0.009b | 52 ± 8a | 41 ± 3c |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates for J, F v/F m, NPQ, αleaf × β, ΦPSII, ΦNPQ, Φf,D, J excess, and J excess/J. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) between three Mg treatments.

J, electron transport rate; F v/F m, the maximal quantum efficiency of photosystem II; NPQ, non-photochemical quenching; αleaf: the leaf absorbance; β, the partitioning of the absorbed quanta between photosystems II and I; ΦPSII, the effective quantum yield of photosystem II; ΦNPQ, the proportion of thermally dissipated energy through NPQ; Φf,D, the fraction of absorbed light energy dissipated by additional quenching mechanism; J excess, the excess of photosynthetic linear electron transport not used for carbon assimilation.

Rice photorespiration rate (P r) significantly increased in 0.01 mM Mg treatment, by 42.9% compared with Mg-sufficient treatment. However, the highest cucumber P r was found in 0.1 mM Mg treatment, where it increased by 14.3% compared with Mg-sufficient treatment. Compared with 1 mM Mg treatment, rice and cucumber P r/P n (2%O2, the net photosynthetic rate in 2%O2) ratios all increased as the Mg supply was reduced, by 71.8% and 56.8%, respectively, at 0.01 mM of Mg ( Table 5 ). In comparison with the 1-mM Mg treatment, rice and cucumber Γ* increased by 11.9% and 16.9%, respectively, under severe Mg deficiency (0.01 mM of Mg).

Table 5.

Effects of Mg supply on photorespiration parameters of rice and cucumber.

| Species | Treatment | P n (μmol m−2 s−1) | P n2%O2 (μmol m−2 s−1) | P r (μmol m−2 s−1) | P r/P n2%O2 (%) | Γ* (μmol mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | 0.01 mM | 14.7 ± 1.6b | 19.7 ± 1.9b | 5.0 ± 0.4a | 25.6 ± 0.6a | 37.7 ± 0.3a |

| 0.1 mM | 16.3 ± 2.3b | 20.5 ± 3.1b | 4.4 ± 1.0ab | 20.1 ± 3.2b | 33.9 ± 0.9b | |

| 1 mM | 20.2 ± 0.7a | 23.7 ± 0.7a | 3.5 ± 0.4b | 14.9 ± 1.6c | 33.7 ± 0.6b | |

| Cucumber | 0.01 mM | 9.1 ± 1.3c | 13.2 ± 1.2c | 4.1 ± 0.2b | 31.2 ± 3.4a | 40.8 ± 1.6a |

| 0.1 mM | 12.0 ± 1.0b | 16.8 ± 0.9b | 4.8 ± 0.1a | 28.6 ± 2.1a | 35.7 ± 0.6b | |

| 1 mM | 17.0 ± 0.6a | 21.3 ± 0.3a | 4.2 ± 0.3b | 19.9 ± 1.6b | 34.9 ± 2.5b |

Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicates for P n, P n2%O2, P r, P r/P n2%O2, and Γ*. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) between three Mg treatments.

P n, net photosynthetic rate; P n2%O2, net photosynthetic rate in 2%O2; P r, photorespiration rate; Γ*, the CO2 compensation point in the absence of mitochondrial respiration.

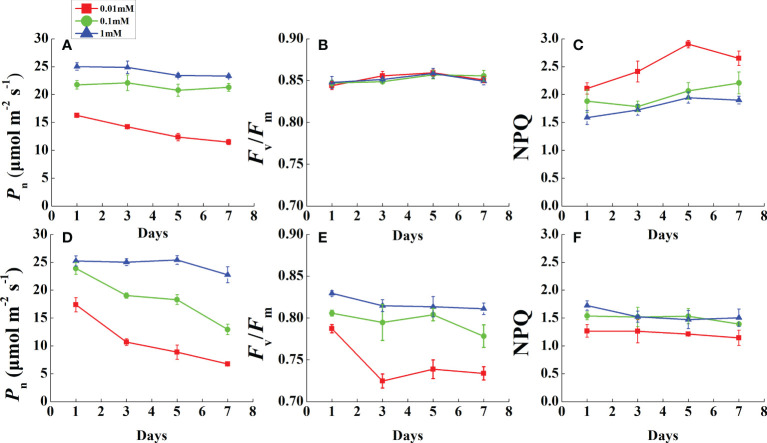

Dynamic photosynthesis changes

During the monitoring period, P n was restricted prior to leaf necrosis under magnesium deficiency ( Figures 3A, D ). After the first measurement in 1 day, the P n of all Mg-deficient treatments (except 0.1 mM of Mg in rice) decreased rapidly and continued to decline until the end of the measurements. As P n declined, F v/F m of all rice treatments was stable and unchanged ( Figure 3B ). However, cucumber F v/F m in 0.01 mM Mg treatment was downregulated dramatically after 1 day and stabilized at a low level ( Figure 3E ). Mg deficiency had opposite effects on rice and cucumber NPQ during this period ( Figures 3C, F ). Under 0.01 mM Mg condition, rice NPQ was significantly enhanced, while for cucumber, it significantly decreased. However, under 0.1 mM Mg condition, rice had a slight increment, while cucumber showed no significant difference compared with Mg-sufficient treatment.

Figure 3.

Variation of photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in fully expanded leaves of rice (A–C) and cucumber (D–F) under different Mg supply treatments during 7 days. Values represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four replicates. P n, net photosynthetic rate; F v/F m, the maximal quantum efficiency; NPQ, non-photochemical quenching.

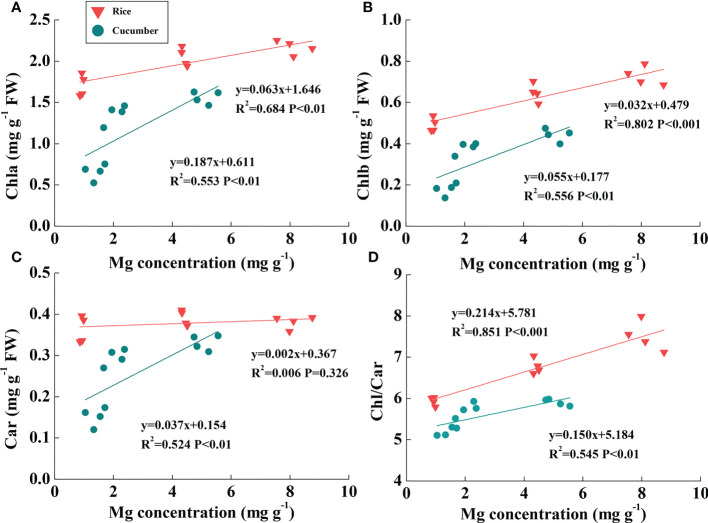

Rice and cucumber pigment composition

Rice Mg concentration was higher than cucumber under the same Mg treatment; additionally, rice leaf pigment contents were much greater than those of cucumber ( Figures 4A–C ). Linear relationships between chlorophyll content and leaf Mg concentration were found across Mg treatments of both plant species ( Figures 4A, B ). Chla and Chlb were both positively correlated with rice and cucumber leaf Mg concentrations. Large slope variations between the two plant species showed that cucumber chlorophylls were more sensitive than those of rice in response to changing leaf Mg conditions. Car was positively correlated with leaf Mg concentration in cucumber, while the correlation was not found in rice ( Figure 4C ). Additionally, Chl/Car positively correlated with Mg concentration in rice and cucumber, but rice exhibited a more sensitive response to Mg deficiency compared with cucumber ( Figure 4D ).

Figure 4.

The correlations of Mg concentration with Chla (A), Chlb (B), Car (C), and Chl/Car ratio (D) in the leaves of rice and cucumber. The lines represent the regressions that are best fit for the data (n = 12). Chla, chlorophyll a content; Chlb, chlorophyll b content; Chl, chlorophyll content; Car, carotenoid content.

Discussion

Mg deficiency restrains rice and cucumber growth

Decreased biomass is a universal phenomenon in Mg-deficient plants (Mengutay et al., 2013; Trankner et al., 2016). Rice and cucumber biomass was significantly reduced under low Mg concentration (0.01 mM) ( Table 1 ). The two plant species exhibited a similar response to Mg deficiency, with a decrease in biomass and leaf area ( Table 1 ), in accordance with previous observations (Chen and Fan, 2018; Peng et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2019). For LMA, different responses to Mg deficiency were observed among species. However, it obviously increased only in cucumber, which could be attributed to relative carbon accumulation (Trankner and Jaghdani, 2019).

Under Mg deficiency, cucumber was more sensitive than rice, with a more marked decline in Chl and Car ( Table 1 , Figure 4 ). Considering the more restricted Mg concentration and relatively high Chl in rice than in cucumber, rice effectively utilized Mg under Mg deficiency. In addition to Chl, Car also acts as a constituent of the light-harvesting antenna system in photosynthetic organisms (Ashraf and Harris, 2013). Importantly, Car can quench triplet chlorophyll and scavenge ROS like single oxygen which damages membranes and dissipates excess energy via xanthophyll-mediated NPQ (Cazzonelli, 2011). Consistent with our cucumber data, in the dicot Sulla carnosa, total Car decreased by 37.2% under extreme Mg-deficient conditions compared with Mg-sufficient plants (Farhat et al., 2015). Thus, photosynthesis-related antenna pigments were damaged by Mg deficiency stress, resulting in reduced light-harvesting efficiency, which affected cucumber more than rice.

Mg deficiency restrains rice and cucumber photosynthesis

An Mg-deficiency-induced lower photosynthetic rate has been shown in rice, barley, and citrus plants (Yang et al., 2012; Trankner et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020). In our study, both rice and cucumber photosynthetic rates were downregulated under Mg deficiency ( Table 2 ), coinciding with significant g s and g m decreases and the same response to Mg deficiency. However, a low g s might not be the major factor driving photosynthesis decline under Mg-deficient stress, because rice and cucumber C i at 0.01 mM of Mg was no different than at 1 mM of Mg ( Table 2 ). Importantly, g m plays a vital role in transmitting CO2 from the substomata to chloroplasts, and considering its decline accompanied by downregulated C c in the two plant species, we speculate that it might be an essential cause of the reduced photosynthetic rate of Mg-deficient plants. Generally, g m is related to leaf anatomic structure, aquaporin characteristics on membranes, and carbonic anhydrase activity in the cytosol and chloroplasts (Evans et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2012). The inherent declining g m mechanism under Mg deficiency deserves further study.

Notably, α and CE decreased significantly under Mg-deficient treatments ( Table 3 ), which implies impaired light-harvesting and carboxylation of both rice and cucumber. Significantly decreased α in cucumber under severe Mg-deficient treatment suggests that its light-harvesting system suffered more damage than that in rice. Under low Mg supply, rice and cucumber J max and V cmax declined to different degrees, with rice exhibiting more tolerance to Mg-deficient stress than cucumber ( Table 3 ). Mg acts as an activator of the Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes (Schneider et al., 1992), and the declining V cmax might be attributed to lower Mg2+ in chloroplasts ( Table 3 ). In rice and cucumber, J max and V cmax displayed the same response to Mg deficiency, and similarly, J max limitation in photosynthesis is also apparent in Mg-deficient grapevines (Rogiers et al., 2020). Considering the downregulation of these two vital biochemical parameters, severe CO2 utilization limitation may occur in Mg-deficient plants. Rice and cucumber all exhibited downregulated J max/V cmax under 0.01 mM of Mg, while cucumber J max/V cmax downregulated even under slight Mg deficiency (0.1 mM). Furthermore, the declining J max/V cmax and C trans suggest a greater limitation by RuBP regeneration than by carboxylation, which implies that under Mg deficiency, the limited energy generated by the electron transport was unable to meet the normal demands for CO2 fixation (Yamori et al., 2011). The 0.1 mM Mg treatment significantly decreased cucumber C trans ( Table 3 ), showing that cucumber was more restricted than rice in terms of J max rather than V cmax.

Rice and cucumber ΦPS(II) and J all decreased as the Mg supply reduced ( Table 4 ), implying declined PSII activity and damaged electron transfer components. Under low Mg supply, ΦPS(II) and J were also affected in sugar beet and S. carnosa (Hermans et al., 2004; Farhat et al., 2015). Strengthened photorespiration in low Mg supply suggests that the declined J may be attributed to the distribution of electrons to photorespiration or other alternative electron sinks and, alternatively, that the electron transport pool to carboxylation is reduced (Yiotis and Manetas, 2010).

Interestingly, only cucumber F v/F m significantly decreased under Mg deficiency ( Table 4 , Figures 3B, E ), which implies that rice, despite being exposed to the same stress, did not suffer from photoinhibition. F v/F m downregulation has been reported in Mg-deficient S. carnosa (Farhat et al., 2015), Vicia faba (Hariadi and Shabala, 2004), and Citrus seedlings (Yang et al., 2012). Other studies have shown that fluorescence parameters including F v/F m are not affected in rice and Helianthus annuus (Lasa et al., 2000; Li et al., 2020), and also verified our result that rice was more tolerant than cucumber to Mg deficiency. NPQ is the major mechanism to avoid photoinhibition, whereby plants convert excess light energy into heat energy (Muller et al., 2001). Elevated NPQ occurs in plants under stress; notably, it increased in rice but decreased in cucumber. Analogous to F v/F m, the irregular variation in NPQ might be species-dependent. Additionally, NPQ plays a crucial role in regulating PSII activity under Mg deficiency, and elevated NPQ is always accompanied by excessive ATP and accumulated H+ in the thylakoid stroma (Kulheim et al., 2002).

Different Mg deficiency sensitivities correlate with unique photoprotective performance

Leaves become chlorotic under Mg deficiency as a consequence of photobleaching; therefore, plants will enhance key ROS-scavenging enzyme activities to remove photooxidation damage (Kanazawa et al., 2000). Aside from ROS scavenging systems, plants strengthen photorespiration and NPQ to consume excess light energy (Kozaki and Takeba, 1996; Muller et al., 2001). We compared rice and cucumber photorespiration performance and found that rice exhibited a more marked rise in P r under Mg deficiency. However, compared with Mg-sufficient treatment, increasing P r/P n (2%O2) ratio rates were similar between rice and cucumber under Mg deficiency treatments ( Table 5 ). Γ* can be used to evaluate photorespiration rates indirectly (Busch, 2013), and elevated levels have been observed in plants under high temperatures or excessive nitrogen supply (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985; Li et al., 2009). Our results further demonstrate that increased Γ* strengthened photorespiration competence in rice and cucumber under Mg deficiency ( Table 5 ). Unexpectedly, rice photorespiration-related parameters were analogous to those of cucumber. Therefore, the stronger photoprotection capacity of rice compared with cucumber cannot be attributed to higher photorespiration.

A 7-day-long dynamic monitoring was conducted before cucumber leaf chlorosis. During this time, Mg-deficient rice leaves all remained green, while cucumber leaves became chlorotic. Interestingly, in rice, F v/F m was maintained even as P n was downregulated under Mg deficiency ( Figures 3A, B ). Under stress, NPQ is expected to increase, but cucumber NPQ decreases under Mg-deficient stress ( Figure 3F ). Considering that rice photosynthetic gas exchange and photorespiration-related parameters were all analogous to those of cucumber, NPQ may be an important factor in determining their differing responses to Mg deficiency.

We suggest that the destroyed chloroplast ultrastructure during leaf chlorosis might affect NPQ function. However, Mg-deficient cucumber NPQ declined on the first day before the leaf became chlorotic; therefore, the decline might be attributed to other factors. In a study of Abies alba MILL photoprotection (Doerken and Lepetit, 2018), sun leaves were exposed to high light radiation and did not suffer from more photoinhibition than shade leaves. Compared with Mg-deficient rice and cucumber, Abies sun leaves exhibited much higher NPQ and more than twice as much xanthophyll per total chlorophyll as the shade leaves. The xanthophyll cycle-dependent NPQ is a major mechanism to avoid photoinhibition (Demmig-Adams and Adams, 2006). NPQ is positively correlated with zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin contents (Niyogi et al., 1997), and xanthophyll cycle pigments are carotenoids. For cucumber, a positive linear relationship was found between Car and Mg concentration ( Figure 4C ). However, there was no direct evidence that Mg deficiency lowered xanthophyll cycle pigment concentrations. Thus, a further study determining Car composition should be conducted to investigate the mechanism underlying decreased NPQ under Mg deficiency.

Cucumber Φf,D significantly increased as ΦNPQ decreased under Mg deficiency, while rice Φf,D was relatively constant ( Table 4 ), indicating that low cucumber NPQ under Mg deficiency may induce light excitation dissipation by additional quenching mechanisms. After calculating J excess, we found that cucumber J excess/J exposed to the lowest Mg supply (0.01 mM) increased by 39.9%, while in rice, it was only 27.9% under the same conditions. It was reported that high rates of electron transfer to some additional/alternative electron transport pathways, such as PTOX-mediated electron transport to oxygen and Mehler reaction, may dissipate excess electrons (Asada, 1999; Cournac et al., 2000). PTOX can transfer electrons from plastoquinone to oxygen without generating ROS; normally, it is only a minor protein and its capacity for consumption of excess electrons appears to be low (Ort and Baker, 2002; Peltier and Cournac, 2002; Josse et al., 2003). However, it has been demonstrated that PTOX-mediated electron transport to oxygen is greatly upregulated and may play a critical role in preventing over-reduction of the photosynthetic electron transport chain under various stress conditions (McDonald et al., 2011). Considering that rice photorespiration-related parameters are analogous to those of cucumber, it is clear that PTOX-mediated electron flow to oxygen might be the most probable alternative electron flow involved in cucumber plant response to Mg deficiency. Furthermore, excess electrons are transported to oxygen in the Mehler reaction, which may form superoxide and finally increase oxidative stress (Huner et al., 1998). Meanwhile, in rice, ROS scavenging enzyme activities were relatively higher than in cucumber under different Mg levels ( Figure S1 ). When comparing the correlations between Mg concentration and the Chl/Car ratio, rice exhibited a more rapid response to Mg deficiency than cucumber ( Figure 4D ). In considering the Car role in scavenging ROS, cucumber was equipped with lower Car under Mg deficiency and may have suffered more oxidative stress than rice.

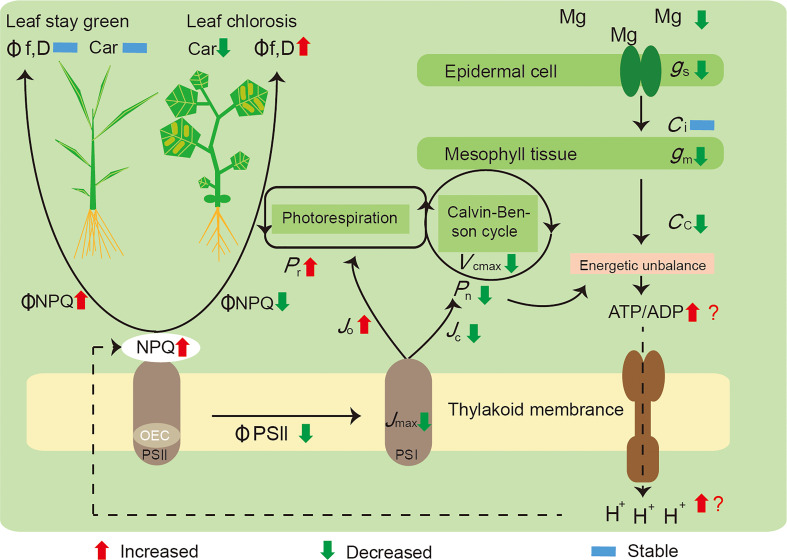

We summarized the mechanisms underlying these responses ( Figure 5 ): i) a decreased Mg concentration in the plant leaves influenced the Calvin–Benson cycle function through restricting g m and Rubisco activity (V cmax), which induced energy captured by light harvesting to exceed utilization by carbon assimilation; ii) Mg deficiency leads to a surplus of energy generated by photophosphorylation, with an increased ATP and ADP ratio, as well as more H+ accumulated in the thylakoid stroma inducing NPQ increment; and iii) in parallel, declining J max and ΦPSII exhibited a RuBP regeneration limitation, and Mg deficiency also increased the proportion of electron transport to photorespiration (J o), further competing with Rubisco carboxylation (J c). Mg deficiency significantly decreased NPQ and increased electron transport rates to other oxygen-dependent pathways in cucumber; meanwhile, rice possessed a stronger photoprotection capacity than cucumber, was in a better condition, and remained green.

Figure 5.

A model highlighting the main effects induced by Mg deficiency on the photosynthesis of rice and cucumber plants. Initially, a decreased concentration of Mg in the leaves of plants, influencing the Calvin–Benson cycle function through restricting g m and V cmax, leading to a surplus of energy generated by photophosphorylation, with the ratio between ATP and ADP increased, yet more H+ accumulated and inducing NPQ increment; in parallel, Mg deficiency also increased the proportion of electron transport to photorespiration (J o), further competing with Rubisco carboxylation (J c). Mg-deficient cucumber showed a decreased ΦNPQ and a higher rate of electron transport to alternative pathways; thus, it suffered preferential damage than rice and became leaf chlorosis. P n, net photosynthetic rate; P r, photorespiration rate; g s, stomatal conductance; g m, mesophyll conductance; C i, intercellular CO2 concentration; C c, CO2 concentration in chloroplasts; V cmax, the maximum Rubisco carboxylation rate; J max, the maximum rate of electron transport; J c, electron flux to Rubisco carboxylation; J o, electron flux to Rubisco oxygenation; NPQ, non-photochemical quenching; OEC, oxygen-evolving complex; ΦPSII, the effective quantum yield of photosystem II; ΦNPQ, the proportion of thermally dissipated energy through NPQ; Φf,D, the fraction of absorbed light energy dissipated by additional quenching mechanism; PSI, photosystem I; PSII, photosystem II; Car, carotenoid content.

Conclusions

Under magnesium deficiency stress, rice and cucumber growth and photosynthesis were inhibited. Suppressed photosynthesis was attributed to integrated limitations of J max, V cmax, and g m. Reduced photosynthetic rate provoked an imbalanced energy between light capture and utilization by carbon assimilation, inducing NPQ increment. In parallel, more electron transport to photorespiration further competed with Rubisco carboxylation. Greater cucumber sensitivity under Mg deficiency was attributed to lower NPQ and higher electron transport rates to alternative pathways and subsequently increased oxidative stress. Overall, these results revealed the inherent mechanism of suppressed photosynthesis and suggested the crucial role of photoprotection capacity under Mg deficiency.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SG, XM and SB conceived and designed the experiment. XM, SW and KC performed the experiments. XM, SB, YP and KX analyzed the data and were responsible for the table and figures. XM wrote the paper. SG, YP and MW proofread and polished the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072673), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2018QNRC001), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYGD202007), and the Innovative Research Team Development Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (IRT_17R56).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1164866/full#supplementary-material

Effects of Mg supply on the activities of SOD (A), POD (B) and CAT (C) of rice and cucumber. Values represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four replicates.

References

- Asada K. (1999). The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: Scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 601–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf M., Harris P. J. C. (2013). Photosynthesis under stressful environments: An overview. Photosynthetica 51, 163–190. doi: 10.1007/s11099-013-0021-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A., Farquhar G. D. (1985). Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light - estimates from gas-exchange measurements on spinach. Planta 165, 397–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00392238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch F. A. (2013). Current methods for estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves. Plant Biol. 15, 648–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I., Kirkby E. A. (2008). Role of magnesium in carbon partitioning and alleviating photooxidative damage. Physiologia Plantarum 133, 692–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzonelli C. I. (2011). Carotenoids in nature: insights from plants and beyond. Funct. Plant Biol. 38, 833–847. doi: 10.1071/FP11192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan Y., Kutman U. B., Mengutay M., Cakmak I. (2016). Magnesium applications to growth medium and foliage affect the starch distribution, increase the grain size and improve the seed germination in wheat. Plant Soil 406, 145–156. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-2871-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. B., Fan X. L. (2018). Effects of magnesium remobilization and allocation on banana plant growth. J. Plant Nutr. 41, 1312–1320. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2018.1450422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. C., Peng W. T., Li J., Liao H. (2018). Functional dissection and transport mechanism of magnesium in plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 74, 142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cournac L., Redding K., Ravenel J., Rumeau D., Josse E. M., Kuntz M., et al. (2000). Electron flow between photosystem II and oxygen in chloroplasts of photosystem I-deficient algae is mediated by a quinol oxidase involved in chlororespiration. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17256–17262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908732199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan J. A. (2002). Structural and catalytic chemistry of magnesium-dependent enzymes. Biometals 15, 225–235. doi: 10.1023/A:1016022730880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B., Adams W. W. (2002). Antioxidants in photosynthesis and human nutrition. Science 298, 2149–2153. doi: 10.1126/science.1078002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B., Adams W. W. (2006). Photoprotection in an ecological context: the remarkable complexity of thermal energy dissipation. New Phytol. 172, 11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01835.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y. C., Chang C. R., Luo W., Wu Y. S., Ren X. L., Wang P., et al. (2008). High potassium aggravates the oxidative stress inducedy by magnesium deficiency in rice leaves. Pedosphere 18, 316–327. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(08)60021-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Luo W., Xu G. (2006). Characterisation of magnesium nutrition and interaction of magnesium and potassium in rice. Ann. Appl. Biol. 149, 111–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2006.00080.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doerken V. M., Lepetit B. (2018). Morpho-anatomical and physiological differences between sun and shade leaves in Abies alba MILL. (Pinaceae, coniferales): a combined approach. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 1683–1697. doi: 10.1111/pce.13213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. R., Kaldenhoff R., Genty B., Terashima I. (2009). Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 2235–2248. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat N., Elkhouni A., Zorrig W., Smaoui A., Abdelly C., Rabhi M. (2016). Effects of magnesium deficiency on photosynthesis and carbohydrate partitioning. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 38, 10. doi: 10.1007/s11738-016-2165-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat N., Ivanov A. G., Krol M., Rabhi M., Smaoui A., Abdelly C., et al. (2015). Preferential damaging effects of limited magnesium bioavailability on photosystem I in Sulla carnosa plants. Planta 241, 1189–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2248-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E. S., Bremer E. (1993). Influence of magnesium-deficiency on rates of leaf expansion, starch and sucrose accumulation, and net assimilation in Phaseolus-vulgaris . Physiologia Plantarum 89, 271–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1993.tb00153.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z. X., He X. L., Zhao B. C., Zhou C. J., Liang Y. Z., Ge R. C., et al. (2010). Overexpressing a putative aquaporin gene from wheat, TaNIP, enhances salt tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 767–775. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee A., Fuhrs H. (2013). Magnesium mobility in soils as a challenge for soil and plant analysis, magnesium fertilization and root uptake under adverse growth conditions. Plant Soil 368, 5–21. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1567-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hariadi Y., Shabala S. (2004). Screening broad beans (Vicia faba) for magnesium deficiency. II. Photosynthetic performance And leaf bioelectrical responses. Funct. Plant Biol. 31, 539–549. doi: 10.1071/FP03202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley P. C., Loreto F., Dimarco G., Sharkey T. D. (1992). Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2 . Plant Physiol. 98, 1429–1436. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.4.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer-Jakli M., Trankner M. (2019). Critical leaf magnesium thresholds and the impact of magnesium on plant growth and photo-oxidative defense: A systematic review and meta-analysis from 70 years of research. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson L., Furbank R. T., Chow W. S. (2004). A simple alternative approach to assessing the fate of absorbed light energy using chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynthesis Res. 82, 73–81. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000040446.87305.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans C., Johnson G. N., Strasser R. J., Verbruggen N. (2004). Physiological characterisation of magnesium deficiency in sugar beet: acclimation to low magnesium differentially affects photosystems I and II. Planta 220, 344–355. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1340-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans C., Vuylsteke M., Coppens F., Cristescu S. M., Harren F. J. M., Inze D., et al. (2010). Systems analysis of the responses to long-term magnesium deficiency and restoration in arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 187, 132–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Yuan Q. Q., Wang Y., Cai R., Deng X. M., Wang J., et al. (2012). Overexpression of a wheat aquaporin gene, TaAQP8, enhances salt stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 2127–2141. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Jiao Y. Y., Nawaz M. A., Chen C., Liu L., Lu Z., et al. (2016). Improving magnesium uptake, photosynthesis and antioxidant enzyme activities of watermelon by grafting onto pumpkin rootstock under low magnesium. Plant Soil 409, 229–246. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-2965-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huner N. P. A., Oquist G., Sarhan F. (1998). Energy balance and acclimation to light and cold. Trends Plant Sci. 3, 224–230. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01248-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson S. (1994). The light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding-proteins. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Bioenergetics 1184, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josse E. M., Alcaraz J. P., Laboure A. M., Kuntz M. (2003). In vitro characterization of a plastid terminal oxidase (PTOX). Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 3787–3794. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa S., Sano S., Koshiba T., Ushimaru T. (2000). Changes in antioxidative enzymes in cucumber cotyledons during natural senescence: comparison with those during dark-induced senescence. Physiologia Plantarum 109, 211–216. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.100214.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaki A., Takeba G. (1996). Photorespiration protects C3 plants from photooxidation. Nature 384, 557–560. doi: 10.1038/384557a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulheim C., Agren J., Jansson S. (2002). Rapid regulation of light harvesting and plant fitness in the field. Science 297, 91–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1072359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing W., Greer D., Sun O., Beets P., Lowe A., Payn T. (2000). Physiological impacts of mg deficiency in pinus radiata: growth and photosynthesis. New Phytol. 146, 47–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00616.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa B., Frechilla S., Aleu M., Gonzalez-Moro B., Lamsfus C., Aparicio-Tejo P. M. (2000). Effects of low and high levels of magnesium on the response of sunflower plants grown with ammonium and nitrate. Plant Soil 225, 167–174. doi: 10.1023/A:1026568329860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gao Y. X., Ding L., Shen Q. R., Guo S. W. (2009). Ammonium enhances the tolerance of rice seedlings (Oryza sativa l.) to drought condition. Agric. Water Manage. 96, 1746–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2009.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yokosho K., Liu S., Cao H. R., Yamaji N., Zhu X. G., et al. (2020). Diel magnesium fluctuations in chloroplasts contribute to photosynthesis in rice. Nat. Plants 6, 848–84+. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0686-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer G. H., Badger M. R., Andrews T. J. (1976). The activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase by carbon dioxide and magnesium ions. equilibria, kinetics, a suggested mechanism, and physiological implications. Biochemistry 15, 529–536. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. (1995). Mineral nutrition of higher plants, second edition. Mineral Nutr. Higher Plants Second Edition. xv+889p. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. E., Ivanov A. G., Bode R., Maxwell D. P., Rodermel S. R., Huenter N. P. A. (2011). Flexibility in photosynthetic electron transport: The physiological role of plastoquinol terminal oxidase (PTOX). Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Bioenergetics 1807, 954–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengutay M., Ceylan Y., Kutman U. B., Cakmak I. (2013). Adequate magnesium nutrition mitigates adverse effects of heat stress on maize and wheat. Plant Soil 368, 57–72. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1761-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P., Li X. P., Niyogi K. K. (2001). Non-photochemical quenching. a response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 125, 1558–1566. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi K. K., Bjorkman O., Grossman A. R. (1997). Chlamydomonas xanthophyll cycle mutants identified by video imaging of chlorophyll fluorescence quenching. Plant Cell 9, 1369–1380. doi: 10.2307/3870388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort D. R., Baker N. R. (2002). A photoprotective role for O2 as an alternative electron sink in photosynthesis? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 193–198. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00259-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltier G., Cournac L. (2002). Chlororespiration. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 523–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. Y., Liao L. L., Liu S., Nie M. M., Li J., Zhang L. D., et al. (2019). Magnesium deficiency triggers SGR-mediated chlorophyll degradation for magnesium remobilization. Plant Physiol. 181, 262–275. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers S. Y., Greer D. H., Moroni F. J., Baby T. (2020). Potassium and magnesium mediate the light and CO2 photosynthetic responses of grapevines. Biology-Basel 9, 18. doi: 10.3390/biology9070144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitch L. V., Ivanov A. G., Krol M., Sprott D. P., Oquist G., Huner N. P. A. (2010). Regulation of energy partitioning and alternative electron transport pathways during cold acclimation of lodgepole pine is oxygen dependent. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1555–1570. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G., Lindqvist Y., Branden C. I. (1992). Rubisco - structure and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biophysics Biomolecular Structure 21, 119–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey T. D., Bernacchi C. J., Farquhar G. D., Singsaas E. L. (2007). Fitting photosynthetic carbon dioxide response curves for c-3 leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1035–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaul O. (2002). Magnesium transport and function in plants: the tip of the iceberg. Biometals 15, 309–323. doi: 10.1023/A:1016091118585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb P., Josse E. M., Gallouet E., Baptist F., Kuntz M., Cornic G. (2005). Evidence for alternative electron sinks to photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the high mountain plant species ranunculus glacialis. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 1123–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01350.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Traenkner M., Tavakol E., Jakli B. (2018). Functioning of potassium and magnesium in photosynthesis, photosynthate translocation and photoprotection. Physiologia Plantarum 163, 414–431. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trankner M., Jaghdani S. J. (2019). Minimum magnesium concentrations for photosynthetic efficiency in wheat and sunflower seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 144, 234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trankner M., Jakli B., Tavakol E., Geilfus C. M., Cakmak I., Dittert K., et al. (2016). Magnesium deficiency decreases biomass water-use efficiency and increases leaf water-use efficiency and oxidative stress in barley plants. Plant Soil 406, 409–423. doi: 10.1007/s11104-016-2886-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini R., Epron D., Deangelis P., Matteucci G., Dreyer E. (1995). In-situ estimation of net CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic electron flow and photorespiration in Turkey oak (Q-cerris l) leaves - diurnal cycles under different levels of water-supply. Plant Cell Environ. 18, 631–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00564.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Huang J., Liang A., Wang Y., Mur L. A. J., Wang M., et al. (2020. a). Zinc and copper enhance cucumber tolerance to fusaric acid by mediating its distribution and toxicity and modifying the antioxidant system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (9), 3370. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Ul Hassan M., Nadeem F., Wu L. Q., Zhang F. S., Li X. X. (2020. b). Magnesium fertilization improves crop yield in most production systems: A meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. J., Broadley M. R., El-Serehy H. A., George T. S., Neugebauer K. (2018). Linear relationships between shoot magnesium and calcium concentrations among angiosperm species are associated with cell wall chemistry. Ann. Bot. 122, 221–226. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S. R., Welch R. M., Mayland H. F., Grunes D. L. (1990). Magnesium in plants - uptake, distribution, function, and utilization by man and animals. Metal Ions Biol. Syst. 26, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wingler A., Brownhill E., Pourtau N. (2005). Mechanisms of the light-dependent induction of cell death in tobacco plants with delayed senescence. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2897–2905. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K. L., Cakmak I., Wang S. Y., Zhang F. S., Guo S. W. (2021). Synergistic and antagonistic interactions between potassium and magnesium in higher plants. Crop J. 9, 249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2020.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W., Nagai T., Makino A. (2011). The rate-limiting step for CO2 assimilation at different temperatures is influenced by the leaf nitrogen content in several c-3 crop species. Plant Cell Environ. 34, 764–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. H., Yang L. T., Jiang H. X., Li Y., Wang P., Chen L. S. (2012). Physiological impacts of magnesium-deficiency in citrus seedlings: photosynthesis, antioxidant system and carbohydrates. Trees-Structure Funct. 26, 1237–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00468-012-0699-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Chen X. F., Deng C. L., Yang L. T., Lai N. W., Guo J. X., et al. (2019). Magnesium-deficiency effects on pigments, photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport of leaves, and nutrients of leaf blades and veins in citrus sinensis seedlings. Plants-Basel 8, 20. doi: 10.3390/plants8100389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiotis C., Manetas Y. (2010). Sinks for photosynthetic electron flow in green petioles and pedicels of zantedeschia aethiopica: evidence for innately high photorespiration and cyclic electron flow rates. Planta 232, 523–531. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1193-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. X., Paakkarinen V., van Wijk K. J., Aro E. M. (2000). Biogenesis of the chloroplast-encoded D1 protein: Regulation of translation elongation, insertion, and assembly into photosystem II. Plant Cell 12, 1769–1781. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Zhou Q., Zhou M., Li C., Gong X., Liu C., et al. (2012). Magnesium deficiency results in damage of nitrogen and carbon cross-talk of maize and improvement by cerium addition. Biol. Trace Element Res. 148, 102–109. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9340-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of Mg supply on the activities of SOD (A), POD (B) and CAT (C) of rice and cucumber. Values represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of four replicates.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.