Abstract

Chiral transition metal catalysts represent a powerful and economic tool for implementing stereocenters in organic synthesis, with the metal center providing a strong chemical activation upon its interaction with substrates or reagents, while the overall chirality of the metal complex achieves the desired stereoselectivity. Often, the overall chiral topology of the metal complex implements a stereogenic metal center, which is then involved in the origin of the asymmetric induction. This review provides a comprehensive survey of reported chiral transition metal catalysts in which the metal formally constitutes a stereocenter. A stereogenic metal center goes along with an overall chiral topology of the metal complex, regardless of whether the ligands are chiral or achiral. Implications for the catalyst design and mechanism of asymmetric induction are discussed for half-sandwich, tetracoordinated, pentacoordinated, and hexacoordinated chiral transition metal complexes containing a stereogenic metal center. The review distinguishes between chiral metal catalysts originating from the coordination to chiral ligands and those which are solely composed of optically inactive ligands (achiral or rapidly interconverting enantiomers) prior to complexation (dubbed “chiral-at-metal” catalysts).

1. Introduction

The stereochemistry of an organic compound has a profound influence on its chemical, physical, and biological properties. Controlling the relative and absolute stereochemistry of a chemical reaction which implements new stereocenters is therefore of fundamental importance in organic synthesis. The application of chiral catalysts is considered a particularly economic strategy for such asymmetric reactions.1 Chiral transition metal complexes are a prominent class of chiral catalysts for asymmetric catalysis since the pioneering work of Knowles, Sharpless, Noyori, and others more than 50 years ago.2−4 The versatility of transition metal complexes can be pinpointed to the many ways that the direct interaction of substrates or reagents with a central transition metal provides a strong chemical activation, while the chirality of the metal complex achieves the necessary asymmetric induction in the course of creating a new stereogenic center.

The design of carefully tailored chiral ligands for generating chiral transition metal catalysts has enjoyed great success and has been at the core of asymmetric transition metal catalysis for already half a century.5 Typically, the metal is assigned the role of a reaction center with the chiral ligand sphere being responsible for the asymmetric induction. As a consequence, the role of the metal as a stereocenter has been somewhat underappreciated.6 However, to recognize the stereogenicity of the metal is important for the design of the chiral metal complex topology and also for understanding the origin of the asymmetric induction in the course of the stereoselective reaction.

Different aspects of metal-centered chirality have been reviewed extensively.7−18 This review will give an overview of reported chiral transition metal catalyst classes which contain a stereogenic metal center. Of course, there are many very popular chiral transition metal catalysts, often with chiral C2-symmetric ligands (e.g., BINAP, BOX, PyBOX, Salen, Taddol), in which the metal center does not display any stereogenicity. However, this review will reveal that a stereogenic metal center is widespread rather than an exception. Sometimes, the chiral ligands are not directly involved in the asymmetric induction but have the sole purpose of implementing and controlling the metal-centered stereochemistry as well as the overall chiral topology. Moreover, recently, an alternative to the common metal-plus-chiral-ligand approach has emerged in which chiral transition metal catalysts are assembled exclusively from achiral or optically inactive free ligands with the overall chirality being the consequence of a stereogenic metal center.19,20 This review will only discuss chiral catalysts in which the metal constitutes both the reaction center plus a stereogenic center. Metal-templated catalysis, in which the metal has a purely structural role with the catalysis occurring exclusively through the organic ligand sphere, falls outside the scope of this review.21−23 Furthermore, not covered are chiral metal complex salts in which the chirality originates from the counterion.24−26

This review is structured according to the overall topology of the chiral complexes with a distinction between catalysts that are formed from chiral versus exclusively optically inactive ligands (achiral or rapidly interconverting enantiomers prior to coordination). Chiral complexes which draw their chirality formally from a stereogenic metal center with all ligands prior to coordination being achiral or optically inactive are dubbed “chiral-at-metal” to distinguish such complexes within the overall class of “stereogenic-at-metal” chiral transition metal complexes.19 Emphasis will be given to examples with meaningful enantioselectivities (>50% ee).

2. Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Chiral Ligands

2.1. Half-Sandwich Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Chiral Ligands

The most common chiral half-sandwich complexes used in asymmetric catalysis possess a pseudo-octahedral three-legged piano-stool geometry with the η5-cyclopentadienyl or η6-arene moiety replacing three facial ligands in an octahedral coordination sphere (Figure 1). If the three legs of such a piano-stool geometry differ, the metal center is rendered stereogenic and the absolute configuration can be assigned the descriptors R or S following the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog rules, in which the polyhapto ligands are considered as pseudoatoms (sum of atomic numbers of π-coordinated atoms, e.g., atomic number of 36 for η6-C6H6 and 30 for η5-C5H5) of a pseudotetrahedral coordination sphere.8,27

Figure 1.

Half-sandwich stereogenic-at-metal complexes for asymmetric catalysis.

Brunner reported in 1969 the first optically active half-sandwich complex in which a central manganese ion was asymmetrically coordinated to an η5-cyclopentadienyl moiety and three additional monodentate ligands in a pseudotetrahedral fashion with sufficient configurational stability.28 Regarding asymmetric catalysis with stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich complexes, one ligand must be labile in order to provide access to the metal center for the substrate or a reagent. Such complexes typically do not display high configurational stability. Therefore, no examples exist in which an η5-cyclopentadienyl or η6-arene moiety is combined with three different monodentate ligands. Instead, mainly two scaffolds, HS-A and HS-B, have been realized which both employ multidentate ligands. In HS-A, the half-sandwich unit is combined with a chiral bidentate ligand and a labile monodentate ligand. In HS-B, the bidentate ligand is further connected to the arene or cyclopentadienyl moiety via a chiral tether. This tether provides additional stability and rigidity which is beneficial for achieving high enantioselectivities.

Carmona reported an early example of catalysis with stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich scaffold HS-A (Scheme 1a).29 Treatment of solvato complex [(η5-C5Me5)Rh(solvent)3]2+ with (R)-1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)propane (R-Propos) provided in a highly diastereoselective reaction [(η5-C5Me5)Rh(R-Propos)(H2O)](SbF6)2 as a single diastereomer with an S-configuration at the rhodium, (SRh,R)-M1. Interestingly, the single methyl group in the bidentate phosphine ligand is responsible for locking the metal-centered configuration. (SRh,R)-M1 was demonstrated to catalyze a Diels–Alder reaction between methacrolein (1) and cyclopentadiene (2) to obtain (1S,2R,4S)-2-methylbicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene-2-carbaldehyde (3) in 87% yield with 62% ee and 97.5:2.5 dr (exo selectivity) at 5 mol % catalyst loading and −20 °C reaction temperature. The authors suggested a mechanism in which the dienophile is activated by coordination to the rhodium center through the carbonyl group.

Scheme 1. Pioneering Studies on Stereogenic-at-Metal Half-Sandwich Catalysts.

Brunner reported an (η6-cymene)ruthenium(II) half-sandwich unit coordinated to the bidentate chiral Schiff base ligand (S)-N-(1-phenylethyl)salicylideneaminate (pesa) and a chloride ligand, providing [(η6-4-iPrC6H4)Me)Ru(pesa)Cl] (M2) (Scheme 1b).30 Under the reaction conditions (room temperature, 24 h), the two diastereomers were in equilibrium with a dr = 87:13 of (RRu,S)-M2a and (SRu,S)-M2b. Thus, the metal center in M2 is configurationally labile, but one configuration is preferred.31 The diastereomeric mixture was demonstrated to catalyze an enantioselective isomerization of 2-n-butyl-4,7-dihydro-1,3-dioxepin (4) to 2-n-butyl-4,5-dihydro-1,3-dioxepin (5) with 99% yield but only a modest enantioselectivity of 61% ee in the presence of NaBH4. The chirality of the product results from a desymmetrization due to a double bond migration. Control experiments (1H NMR, IR, MS) support the proposal that NaBH4 reduced the imine of the chelate ligand during the catalysis.30 These studies by Brunner highlight the challenges of scaffold HS-A associated with the configurational lability of such complexes. Apparently, most or even all HS-A catalysts discussed in this section are formed under thermodynamic control. Thus, the bidentate ligand must be chosen carefully so that the half-sandwich complex forms as a single diastereomer and provides a high asymmetric induction during the catalysis.

In 2001, Faller reported the half-sandwich complex [(η6-iPrC6H4Me)Ru(aS-BINPO)Cl]SbF6 (M3), synthesized from the reaction of [(η6-iPrC6H4Me)RuCl2]2 with (aS)-(2-diphenylphospino-2′-diphenylphospineoxide)-binaphthyl ((aS)-BINPO) in the presence of NaSbF6 in CH2Cl2 to obtain M3 in 85% yield as a single diastereomer (RRu,aS) (Scheme 1c).32 Starting from complex M3, the active Lewis acid was generated in the presence of AgSbF6. 1H and 31P NMR experiments revealed that, upon mixing of the chloride complex with AgSbF6, a single diastereomer of the aqua complex formed, in which chloride was replaced by a more labile water ligand. The coordinated water apparently resulted from trace amounts of water in the solvent. Such an in situ activated chiral Lewis acid was demonstrated to serve as a chiral catalyst for asymmetric Diels–Alder reactions. For example, 11 mol % M3 with 10 mol % AgSbF6 at −78 °C in CH2Cl2 provided full conversion of 1 and 2 to form norbornene 3 after 12 h with 99% ee (S) and 93% de (exo selectivity). The authors proposed a transition state in which methacrolein (1) coordinates to the Ru through the aldehyde carbonyl group in the anti-S-trans conformation (transition state I). The binaphthyl and aryl rings then block the methacrolein CαRe-diastereoface, allowing a controlled approach of the cyclopentadiene (2) to the methacrolein CαSi-diastereoface. The authors concluded that the electronic asymmetry associated with the stereogenic Ru center was a critical factor in the catalyst stereorecognition. Indeed, an analogous (aS)-BINAP complex in which the Ru center is not stereogenic due to the C2-symmetry of the BINAP ligand afforded a significantly lower enantioselectivity for the same Diels–Alder reaction.32 Thus, in this example, the function of the chiral ligand is mainly limited to control the metal-centered configuration, while the stereogenic metal center is responsible for the asymmetric induction.

One of the most powerful classes of stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich catalysts was introduced by Noyori, Ikariya, and co-workers in 1995 (Scheme 1d).33 The ruthenium(II)-η6-mesitylene (pre)catalyst (RRu,S,S)-M4, bearing a bidentate, monosulfonylated, chiral 1,2-diphenylethylenediamine (TsDPEN), and monodentate chloride ligand was demonstrated to be an outstanding catalyst for asymmetric transfer hydrogenations of aromatic ketones using a formic acid–triethylamine mixture as the reducing agent.34 Noyori already recognized the stereogenic nature of the metal center which is the result of the non-C2-symmetry of the TsDPEN ligand.The (S,S)-TsDPEN ligand induces the R-configuration at the ruthenium center and permits bifunctional catalysis with the primary amine serving as a hydrogen-bond donor and ultimately proton donor. In the proposed 6-membered transition state II, a hydride and proton are transferred to the ketone substrate in a concerted fashion.35,36 The stereogenic carbon atoms of the chiral TsDPEN ligand are secluded from the reaction center; hence, the stereogenic metal center is ultimately promoting the asymmetric induction, while the chirality in the TsDPEN ligand controls the absolute configuration at the metal center. A large number of studies followed this pioneering work on asymmetric transfer hydrogenation which has been reviewed extensively.37,38

Wills and co-workers developed a tethered version of Noyori’s and Ikariya’s catalyst (scaffold HS-B).39 The tether increases catalyst longevity and activity and additionally provides conformational rigidity which supports the stereodiscrimination. In (RRu,S,S)-M5, the η6-benzene ring and the tosylated diamine ligand are connected through a three-carbon tether. The reduction of acetophenone (6) to its corresponding alcohol 7 was achieved with 96% ee at a catalyst loading of merely 0.01 mol %.40 Ikariya recently reported a further improved tethered catalyst following scaffold HS-B using an ether linker.41,42 The half-sandwich complex (SRu,R,R)-M6 displays an impressive catalytic performance. The highly enantioselective asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of acetophenone (6) to 1-phenylethanol (7) was accomplished using just 0.0033 mol % of the catalyst M6.41 Complex M6 was also applied to the challenging asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of diarylketones.42 Additionally, the corresponding precursor, which is converted to M6 by simple HCl addition, was demonstrated to be suitable for asymmetric hydrogenations with H2 (3 MPa).41

The role of the metal-centered configuration for catalytic activity and stereoinduction of the Noyori–Ikariya catalyst M4 was recently reinvestigated by Hintermair (Scheme 2).43 As mentioned above, the chiral TsDPEN ligand can theoretically result in two diastereomeric ruthenium complexes. For example, (S,S)-TsDPEN can lead to the intermediate hydride complexes (SRu,R,R)-M7 and (RRu,R,R)-M7. Indeed, NMR spectroscopy and Overhauser effect spectroscopy in combination with DFT calculations revealed that under the reaction conditions both diastereomeric ruthenium hydride complexes are formed and are in equilibrium via the complex M8, which is devoid of metal stereogenicity and actually the true active catalyst for the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation.44 However, regarding the intermediate ruthenium hydride, (SRu,R,R)-M7 is both thermodynamically and kinetically favored and much more active toward the hydrogenation of acetophenone (6), providing alcohol 7 with the R-configuration. The minor diastereomer (RRu,R,R)-M7 is both less active and predicted to be less enantioselective. Interestingly, according to the DFT calculations, (RRu,R,R)-M7 theoretically favors the formation of (S)-7, hence giving rise to the opposite product configuration although the absolute stereochemistry at the TsDPEN ligand remains unchanged. This does not only emphasize the importance of the metal stereochemistry for the asymmetric induction but also for the catalytic activity itself.43

Scheme 2. Role of Metal-Centered Chirality in Asymmetric Hydrogenation with Noyori–Ikariya Catalyst.

In addition to asymmetric transfer hydrogenations, the Noyori–Ikariya type catalyst scaffold can also be applied to enantioselective nitrene chemistry as shown recently. Accordingly, Yu45 reported that (SRu,R,R)-M9 catalyzes the enantioselective conversion of 1,4,2-dioxazol-5-ones 8 into chiral γ-lactams 9, a reaction that was first reported by Chang46,47 (Scheme 3). The stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich complexes (RIr,S)-M1048 and (RIr,S,S)-M1147 have also been reported to catalyze this transformation with high enantioselectivities. Iridium catalyst M11 contains a Noyori–Ikariya-type sulfonyldiamine ligand.49 Mechanistic investigations by Chang are consistent with a reaction through the iridium nitrene intermediate III. Nitrene insertion into a γ-C–H bond is supposed to occur through a staggered six-membered half-chair transition state which determines the absolute configuration of the γ-lactam.47 Key aspect is a hydrogen bond between the amide oxygen of the substrate-derived nitrene and a N–H hydrogen of the chiral ligand. In analogy to the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation with Noyori–Ikariya catalysts, the asymmetric induction is mediated by the overall arrangement of the metal-coordinated substituents, hence, by the metal-centered stereochemistry, while the chiral sulfonyldiamine ligand implements the metal stereocenter and serves as the crucial hydrogen bond donor.

Scheme 3. Stereogenic-at-Metal Half-Sandwich Catalysts for Enantioselective Ring-Closing Nitrene C(sp3)-H Amidation.

Other studies regarding asymmetric catalysis with stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich complexes have been reported which follow the general scaffolds HS-A and HS-B.50−67 Stereogenic-at-metal half-sandwich complexes in which the half-sandwich moiety is linked to a monodentate ligand and the ligand sphere being complemented with two more monodentate ligands have not provided satisfactory results.68−70 Finally, it is worth mentioning that there are cases in which the chiral half-sandwich catalyst initially does not contain a stereogenic metal center but is rendered stereogenic after substrate binding.71,72

2.2. Tetracoordinated Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Chiral Ligands

Tetracoordinated metal complexes possess a stereogenic metal center if the coordination mode is tetrahedral with four different coordinating ligands (Figure 2). Such tetrahedral complexes are typically configurationally labile, and therefore applications of tetrahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes in asymmetric catalysis are rare.

Figure 2.

Tetrahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes for asymmetric catalysis.

Hoveyda and Schrock demonstrated that despite their lability, such tetrahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes can serve as excellent chiral catalysts with high asymmetric inductions by exploiting the metal-centered fluxionality. Specifically, they introduced a class of tetrahedral stereogenic-at-molybdenum complexes for enantioselective alkene metathesis (Scheme 4).73−75 The Mo(VI) complex M12 contains four different monodentate ligands, one alkylidene ligand, one imido ligand, one phenoxide, and one pyrrolide, which renders the molybdenum a stereogenic center (Scheme 4a). A mono-TBS-protected monodentate aR-configured binaphthol ligand induces the S-configuration at the Mo center, providing (SMo,aR)-M12 as the main diastereomer. The complex (SMo,aR)-M12 (1 mol %) was demonstrated to catalyze the ring-closing metathesis (RCM) of the triene 10 to form diene (S)-11 in 91% yield and with 93% ee.73,74 The molybdenum complex (SMo,aR)-M13, bearing an adamantylimido instead of a 2,6-diisopropylphenylimido ligand, was demonstrated to catalyze highly Z- and enantioselective ring-opening/cross-metathesis (ROCM) reactions, with one example shown (12 + 13 → 14, Scheme 4b).76

Scheme 4. Stereogenic-at-Mo Metathesis Catalysts Developed by Hoveyda and Schrock.

The catalysts were typically synthesized diastereoselectively in situ by reaction of molybdenum bis-pyrrolides with mono-TBS-protected octahydrobinaphthol 15 via diastereoselective protonation of the molybdenum bis-pyrrolides starting complexes M14a or M14b. Interestingly, the diastereoselectivities are only modest for the shown catalysts: (SMo,aR)-M12:(RMo,aR)-M12 = 7:1 and (SMo,aR)-M13:(RMo,aR)-M13 = 3:1 (Scheme 4c).74,77 The complexes are fluxional, and the diastereomeric ratios therefore reflect the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the two diastereomers resulting from inverted metal-centered configurations. For most reaction systems, this fluxionality would pose a peril to the overall enantioselectivity of the catalyzed reaction. However, the Mo-catalyzed, enantioselective olefin metathesis with these catalysts has a unique mechanism in which both diastereomers afford the same product enantiomer with almost identical enantiomeric excess.

The proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 4d.77 The molybdenum center undergoes an inversion with every sequence that includes formation of a metallacyclobutane (MoS=C + substrate olefin → metallacyclobutane IV → C=MoR + product olefin). Mechanistic experiments support a mechanism in which initially generated ethylene commences degenerate metathesis and permits a rapid interconversion of the metal centered configuration. Under the reaction conditions, isomerization of the two diastereomers is more facile than ring closure so that Curtin–Hammett conditions apply. The stereochemical outcome of the RCM reaction is therefore independent of the identity of the metal-centered configuration of the initiating alkylidene complex. Thus, because of the rapid interconversion of the metal-centered configuration by degenerate metathesis, stereomutation at the metal becomes inconsequential and, as a result, stereoselective synthesis of a chiral catalyst is not required. The authors also stressed the importance of the electronic dissymmetry at the metal (monodentate donor and acceptor ligand) because it facilitates olefin coordination and metallacycle collapse, revealing the advantages of having only monodentate ligands in the catalyst (stereogenic metal) instead of a chiral bidentate ligand (no stereogenic metal if the chiral bidentate ligand is C2-symmetric).

2.3. Pentacoordinated Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Chiral Ligands

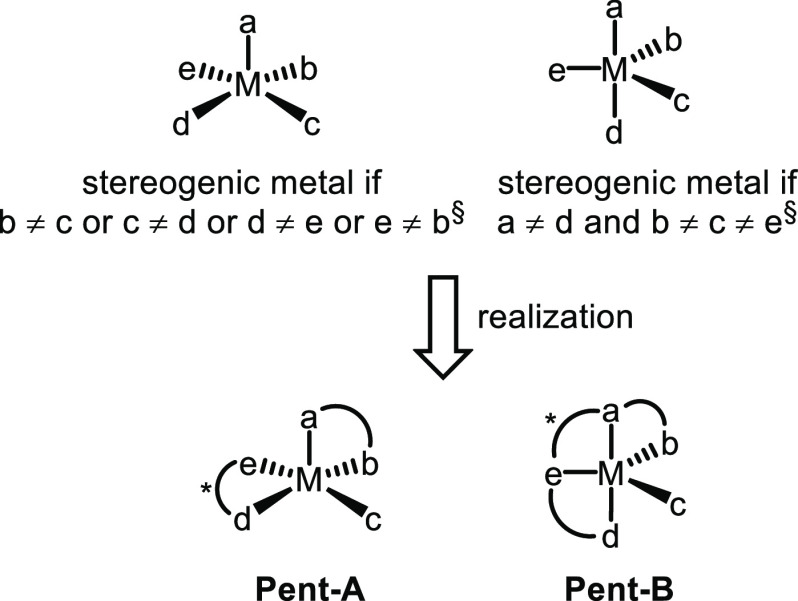

Pentacoordinated metal complexes are typically either square pyramidal or trigonal bipyramidal and examples of chiral catalysts with stereogenic metal centers have been reported for both coordination modes, corresponding to the scaffolds Pent-A and Pent-B, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trigonal bipyramidal and square pyramidal stereogenic-at-metal complexes for asymmetric catalysis. §The requirements change if multidentate ligands are involved.

Based on the Hoveyda–Grubbs ruthenium metathesis catalyst scaffold containing a benzylidine ligand with a chelating ortho-isopropoxy group,78−80 Hoveyda’s group developed chiral ruthenium catalysts containing a chiral chelating N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand for enantioselective olefin metathesis (Scheme 5).81−83 The complexes accommodate a distorted square pyramidal coordination geometry with a stereogenic ruthenium center (corresponds to Pent-A in Figure 3). In the course of the synthesis, coordination of the bidentate NHC ligand occurs highly diastereoselective, thus predetermining the metal-centered configuration. The complexes are air-stable, can be purified by chromatography with undistilled solvents, and are recyclable after catalysis.

Scheme 5. Pentacoordinated Stereogenic-at-Metal Complexes for Enantioselective Metathesis.

Regarding asymmetric catalysis, M15 (10 mol %) was demonstrated to catalyze the asymmetric ROCM of tricyclic norbornene 16 with the alkene 17 to provide 18 in 60% yield and with 98% ee (Scheme 5a).81 A slightly modified catalyst with an additional phenyl group and the chloride replaced by iodide (M16) showed impressive results for the asymmetric ROCM with oxabicyclic olefins in the absence of solvents (Scheme 5b).83 The transformation allows access to a wide range of 2,6-disubstituted pyrans (e.g., 19 + 13 → 20), building blocks found in numerous biologically significant molecules.

Tetradentate hybrid salan/salen (salalen84) ligands can also provide pentacoordinated stereogenic-at-metal (pre)catalysts. Accordingly, Katsuki reported that the aluminum salalen complex M17, synthesized by reacting salalen ligand (R,R)-21 with Et2AlCl, catalyzes the enantioselective hydrophosphonylation of benzaldehyde 22 with dimethylphosphite (23) to provide α-hydroxy phosphonate (S)-24 in 95% yield and with 94% ee in THF at −15 °C (10 mol % catalyst loading) (Scheme 6).85,86 A crystal structure of M17 revealed a distorted trigonal bipyramidal coordination mode of the chloride ligand together with the C1-symmetric tetradentate salalen ligand coordinated in a cis-β-arrangement (corresponds to Pent-B in Figure 3). Because all five coordinating ligands differ, the aluminum center is stereogenic.78 The role of the stereogenic metal center in the asymmetric induction was not discussed by Katsuki. However, the authors propose a mechanism in which binding of both the phosphite and aldehyde, upon chloride dissociation, converts the trigonal bipyramidal into an octahedral stereogenic metal center.86

Scheme 6. Pentacoordinated Stereogenic-at-Aluminum Salalen Catalyst Applied to Asymmetric Hydrophosphonylation.

2.4. Hexacoordinated Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Chiral Ligands

2.4.1. Hexacoordinated Catalysts from Chiral Bidentate Ligands

Octahedral stereogenic-at-metal complexes with two bidentate ligands acquire their overall stereogenicity from the helical arrangement of the bidentate ligands, thereby generating a chiral center at the metal which they are surrounding. This propeller-like twist results in the formation of either a left-handed (Λ-configuration) or right-handed (Δ-configuration) overall helical topology (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Topology of octahedral complexes with helical chirality.

Krische developed a highly interesting iridium(III)-π-allyl catalyst containing an unusual ortho-cyclometalated C,O-benzoate in addition to a chiral diphosphine ligand (Scheme 7a).87−89 The iridium of representative catalyst M18 is coordinated in a pseudo-octahedral fashion if one considers that the π-allyl ligand occupies two coordination sites. The (aR)-BINAP or (aR)-T-BINAP ligand induces a Λ-configuration at the iridium center. Complexes M18 and related complexes were proven to be excellent catalysts for enantioselective carbonyl allylations and propargylations via alcohol-mediated hydrogen transfer. For example, Λ-(aR)-M18a (5 mol %) efficiently catalyzed the reaction of allylacetate (25) with the aromatic aldehyde 26 in the presence of i-PrOH (200 mol %) and Cs2CO3 (20 mol %) at 100 °C to provide the allylic alcohol (S)-27 in 90% yield and with 96% ee.87 In the catalytic cycle, iridium switches back and forth between the oxidation state I and III. 2-Propanol serves as a reducing agent to reduce Ir(III) to Ir(I), followed by oxidative addition to allylacetate and subsequent C–C coupling with the aldehyde. With respect to metal stereochemistry, the iridium center temporarily forfeits its stereogenicity upon reduction from Ir(III) to square-planar Ir(I). Consequently, the chiral BINAP ligand assures a highly diastereoselective oxidative addition to afford a stereogenic-at-metal Ir(III)-π-allyl complex intermediate, which then is involved in the asymmetric induction during the subsequent C–C bond formation step. The same class of stereogenic-at-iridium catalysts has also been used for site-selective tert-(hydroxy)prenylations of 1,3-diols in the absence of protection groups and with high levels of catalyst-controlled diastereoselectivity. For example, the reaction of isoprene oxide (28) with (S)-butanediol (29) was catalyzed by Λ-(aR)-M18b in the presence of K3PO4 (5 mol %) to provide triol 30 in 63% yield with >20:1 dr.89

Scheme 7. Octahedral Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with One or Two Chiral Bidentate Ligands.

Yamamoto reported that the in situ assembled chiral iron(II) bis(phenanthroline) complex Δ-(aR,aR)-M19 is capable of catalyzing an asymmetric epoxidation of β,β-disubstituted enones (Scheme 7b).90 For example, enone 31 was converted to epoxide (2R,3S)-32 in 80% yield and with 91% ee at 0 °C with CH3CO3H as oxidant and 5 mol % of the iron catalyst. A crystal structure of the complex M19 confirmed that the (aR)-1,1′-binaphthyl substituents connected to the 1,10-phenanthroline ligands induce a Δ-configuration at the iron center, thus providing Δ-(aR,aR)-M19. Due to the limited configurational stability of 3d-metal complexes, the chiral 1,10-phenanthroline ligands must coordinate under thermodynamic control, hence fixing the absolute configuration at the metal center and the overall helical topology, which in turn is suggested to be mainly responsible for the asymmetric induction.

Meggers reported the enantioselective alkynylation of 2-trifluoracetyl imidazoles catalyzed by bis-cyclometalated rhodium(III) complexes containing pinene-derived ligands (Scheme 7c).91 For example, 2-trifluoroacetyl imidazole 33 was converted with phenylacetylene (34) to the propargylic alcohol (R)-35 in 92% yield and with 99% ee using the catalyst Δ-M20 with Δ-configuration at the rhodium center. Conversely, using the catalyst Λ-M20 with Λ-configured rhodium center provided the mirror-imaged (S)-35 in 90% yield and with 99% ee. Because Λ- and Δ-M20 have identical chiral ligands and exclusively differ by the rhodium-centered configuration, this example reveals that the asymmetric induction is solely controlled by the metal-centered configuration and the resulting overall topology of the metal complex. In contrast to Yamamoto’s chiral iron catalyst, these rhodium complexes are configurationally inert with the chiral pinene moieties having the exclusive function to provide a handle for resolving the metal-centered stereoisomers without affecting the coordination chemistry. A related bis-cyclometalated rhodium(III) pinene complex (Λ-M21) was reported by Kang for an efficient Au/Rh cocatalyzed cascade reaction of keto ester 36 with alkynyl alcohol 37 and amides to provide chiral spiroketal 38 (Scheme 7d). When alkynyl amides were used, the corresponding chiral spiroaminals could be obtained in similar yields and enantioselectivities.92

Iridium complexes with chiral mixed phosphine/oxazoline bidentate ligands have been reported for the efficient catalytic enantioselective hydrogenation of aryl alkyl N-arylketimines.93,94 For example, acetophenone N-phenyl imine (39) is hydrogenated to provide the chiral amine (R)-40 in the presence of catalytic amounts of M22,95M23,96 or M24(97) (Scheme 8a). Complexes M22–M24 are square planar and do not possess any metal-centered chirality. The stereogenicity is solely located within the coordinating bidentate ligands. However, mechanistic experiments and DFT calculations revealed that M22–M24 are merely precatalysts which spontaneously react with one equivalent of imine substrate to form an intermediate iridacycle, containing a stereogenic metal center, which then functions as the active catalyst.97−99 For example, Scheme 8b shows the reaction of M24-ent (the enantiomer of M24) with one equivalent of imine 39 in the presence of H2 to form the octahedral complex M25, which includes the cyclometalated imine substrate.100 Complex M25 is formed as a single stereoisomer. The complex is stable and can be handled under air. Interesting to note, in contrast to M24, the iridacycle M25 is suitable for the asymmetric hydrogenation of N-methyl and N-alkyl imines.100 Mechanistically, these asymmetric hydrogenations are supposed to proceed through a mechanism as shown in Scheme 8c (shown for a Δ-configured iridacycle).97,99 Cyclometalation with the iridium(I) precatalyst and hydrogen addition leads to the active iridium(III) catalyst V. Upon proton transfer the dihydride complex VI is formed together with the protonated amine. This is followed by a stereocontrolled hydride transfer to provide complex VII. Release of the chiral amine then allows a new catalytic cycle to proceed.

Scheme 8. Octahedral Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with Two Bidentate Ligands Formed in Situ.

Finally, stereogenic-at-metal catalysts can contain more than two chiral bidentate ligands. One prominent example are heterobimetallic lanthanide BINOLate complexes.101 These multifunctional catalysts consist of a central lanthanide ion (oxidation state +3) coordinated in a bidentate fashion by three double deprotonated BINOLates. The excess negative charge is compensated by the coordination of main-group counterions (typically Li, Na, or K) to BINOLate oxygens as shown in the complex [M3(sol)n(BINOLate)3Ln] (M26) (Scheme 9a). These bridging interactions stabilize the heterobimetallic structure and at the same time increase the Lewis acidity of the central lanthanide ion. The lanthanide center represents a stereocenter with either Λ- or Δ-configuration.1 Interestingly, only one diastereomer is observed in solution and the solid state, revealing that the axial chirality of the BINOLate ligands controls the absolute metal-centered configuration. (aS)-BINOL results in the formation of the Λ-configured metal center. Complexes [M3(sol)n(BINOLate)3Ln] are multifunctional chiral catalysts in which the lanthanide center and the main group metal cations serve as Lewis acids while the basic BINOLate oxygens can act as Brønsted bases. Importantly, the versatility of these catalysts can also be traced back to the ability of the lanthanide complexes to expand the coordination sphere to coordination numbers 7 and 8.101

Scheme 9. Heterobimetallic Lanthanide BINOLate Catalysts with Stereogenic Metal Center.

Shibasaki reported the first application of these heterobimetallic complexes in asymmetric catalysis, namely catalyzing enantioselective nitroaldol reactions (Henry reaction) (Scheme 9b).102,103 A proposed mechanism for the reaction of nitromethane with the aldehyde 41 to afford alcohol 42 involves the deprotonation of the nitromethane by a basic BINOLate oxygen, and the resulting nitronate remains coordinated to one of the lithium ions of the heterobimetallic complex. Subsequently, the aldehyde substrate expands the coordination sphere by binding to the central Lewis acidic lanthanide ion thereby becoming activated toward a nucleophilic attack of the nitronate (intermediate VIII).104 The asymmetric induction is most likely mediated by both the overall chiral topology (stereogenic metal center) and the axial chirality of the BINOLate ligands.

2.4.2. Hexacoordinated Catalysts from Chiral Tetradentate Ligands

Chiral octahedral complexes assembled from linear tetradentate ligands (sequentially arranged donor sites) constitute a large class of chiral transition metal catalysts containing a stereogenic metal center. Typically, the tetradentate ligands are symmetric (Figure 5). Upon coordination, they can form the three geometric isomers trans, cis-α, and cis-β.10 The coordination sphere is usually complemented by two ancillary monodentate ligands. In the trans isomer, the monodentate ligands occupy apical positions, in the cis-α-isomer two equatorial positions, and in the cis-β-isomer, one equatorial and one apical position. While the metal center is not stereogenic in the trans geometry, cis-α and cis-β feature a stereogenic metal center. The cis-α-coordination geometry is especially popular due to its C2-symmetry which often has advantages for asymmetric catalysis due to fewer numbers of competing transition states.

Figure 5.

Coordination isomers for linear (sequential) tetradentate ligands within an octahedral coordination sphere. cis-α and cis-β feature a stereogenic metal center. The monodentate ligands X are typically labile.

Nonheme Fe(II) coordination complexes with linear tetradentate bis(pyridylmethyl)diamine ligands as well as analogous bis(quinolyl)diamine and bis(benzimidazolylmethyl)diamine ligands with a range of chiral ligand backbones have emerged as a powerful class of catalysts (M28) for asymmetric C–H and C=C oxygenations (Scheme 10a).105−107 The catalytically active configuration is the cis-α-topology,108 which wraps around the central iron in a helical fashion, while the chiral backbone determines the metal-centered stereochemistry. For example, a 2-(2-pyrrolidinyl)pyrrolidine backbone, first introduced by White as an especially rigid chiral backbone for such nonheme iron catalysts,109 provides full control of the metal-centered configuration. Reaction of the ligand (R,R)-43 with Fe(OTf)2·2 MeCN affords the complex Δ-(R,R)-M29 as the only stereoisomer in 75% yield (Scheme 10b).110 In this catalyst platform, the coordinated linear tetradentate chiral ligand provides the asymmetric induction, while two additional labile cis-sites in the coordination sphere of the iron center are responsible for the catalysis. Important with respect to the topic of this review, the carbon stereocenters of the linear tetradentate ligand are remote from the catalytically active site and therefore not directly involved in the asymmetric induction. The chiral backbone rather controls the overall topology together with the metal-centered configuration, which subsequently steers the stereochemistry of the catalyzed chemical transformations.

Scheme 10. Octahedral Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with One Chiral Tetradentate Ligand for C–H and C=C Oxygenations.

The asymmetric cis-dihydroxlation of olefins catalyzed by such nonheme iron complexes was first reported by Que and later improved with respect to enantiomeric excess using the rigid dipyrrolidine complex M29.110,111 However, a 50-fold excess of alkene over H2O2 was necessary to obtain satisfactory results. Che introduced the quinoline-based iron catalyst M30 for highly enantioselective cis-dihydroxylations of mono- and disubstituted, electron-rich, as well as electron-deficient alkenes using only limiting amounts of the oxidant H2O2 (Scheme 10c).112,113 For example, catalyst M30 (3 mol %) in the presence of 3 equiv of H2O2 converted methyl cinnamate (44) to the cis-diol 45 in 85% isolated yield and with impressive 99.8% ee.112 Expanding the scope, the same group reported an iron-catalyzed, highly enantioselective cis-dihydroxylation of trisubstituted alkenes with aqueous H2O2.113 Regarding the relative and absolute configuration of M30, a crystal structure with the R,R-configured cyclohexane-1,2-diamine backbone provided iron complexes in cis-α configuration with both metal-centered Λ- and Δ-configuration in the unit cell. However, the crystal structure of a closely related derivative (CH2F instead of CH3 substituents in the quinoline moieties) only gave the Λ-(R,R)-stereoisomer.112

Scheme 10d shows an example of a highly enantioselective epoxidation of alkenes: Chalcone (46) was converted to the epoxide 47 in 99% yield and with 98% ee using the iron dipyrrolidine catalyst M31 (2 mol %) in the presence of a carboxylic acid and with H2O2 as the oxidant.114 The reaction is thought to proceed through an iron(III) hydroperoxide followed by an acid-assisted heterolytic cleavage of the O–O bond in an FeIII(OOH)-(HO2R) precursor to provide an iron oxo species as the oxygen atom delivering agent.

Manganese(II) complexes based on the same linear tetradentate bis(pyridylmethyl)diamine template have been successfully applied to stereocontrolled C–H oxidations, especially oxidative desymmetrizations (Scheme 10e). For example, Costas reported the enantioselective desymmetrization of 48 to the chiral ketone 49 in 85% yield and with 94% ee using the manganese catalyst M32 (2 mol %) with the assistance of a carboxylic acid and using H2O2 as the oxidant.115 Regarding the relative and absolute configuration of the manganese complex M32, the chiral backbone with S,S-configured cyclohexane-1,2-diamine provided a metal-centered Λ-configuration and thus differs from the iron complex M30. This can be pinpointed to the inherent flexibility of the cyclohexane motif in combination with different steric preferences of the bis(pyridylmethyl)diamine and bis(quinolyl)diamine ligand system.

Finally, Sun reported a related enantioselective oxidation of methylene groups, for example, using manganese catalyst M33 (0.5 mol %) for the carboxylic acid-assisted conversion of the spiro compound 50 into the chiral diketone (S)-51 in 80% yield and with 94% ee using H2O2 as the oxidant.116

Beyond C–H and C=C oxidations, the Che group revealed that nonheme Fe(II) coordination complexes with chiral linear tetradentate ligands wrapped around the central iron are also suitable for chiral Lewis acid catalysis.117,118 For example, the bis(quinolyl)diamine iron(II) complex M34 was demonstrated to catalyze the conjugate addition of N-Bn-indole to α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazoles (e.g., 52 + 53 → 54) with excellent enantiomeric excess (Scheme 11a).117 Notably, the incorporation of fused cyclopentane rings into the quinoline moieties unexpectedly gives rise to a cis-β-topology in contrast to the catalysts M30 and M32, which adopt a cis-α-topology. Mechanistically, the α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazole is supposed to be activated by N,O-bidentate coordination to the iron center. The C2-symmetric propeller-type coordination sphere then blocks one prochiral face of the alkene, thus providing an effective asymmetric induction for the subsequent conjugate addition of the electron-rich aromatic moiety.

Scheme 11. Other Transformations for Octahedral Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with One Chiral Tetradentate Ligand.

Xiao reported that the chiral cobalt complex M35 serves as a chiral Lewis acid for radical conjugate additions with the radicals generated from 4-substituted Hantzsch esters by means of photoredox catalysis (Scheme 11b).119 For example, the cobalt(II) complex M35, assembled in situ from CoCl2·6H2O (8 mol %) and the chiral bis(benzimidazolylmethyl)diamine ligand (9.6 mol %), was reported to catalyze the benzylation of α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazole 55 using Hantzsch ester 56 to obtain 57 in 86% yield and with 92% ee under photoredox conditions (blue LEDs) in the presence of the acridinium photocatalyst PC (2 mol %). Mechanistically, the α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazole 55 is supposed to coordinate to the cobalt Lewis acid, which provides an electronic activation as well as the asymmetric induction for the subsequent radical conjugate addition.

Finally, Meggers recently reported that nonheme Fe(II) coordination complexes with chiral linear tetradentate chiral ligands are also suitable catalysts for stereocontrolled nitrene chemistry.120 As shown in Scheme 11c, the iron dichloride complex (R,R)-M36 serves as a catalyst for converting azanyl esters 58 into nonracemic amino acids 59. Mechanistically, the reaction is proposed to proceed through a 1,3-migratory nitrene C(sp3)-H insertion via transition state IX.

Chiral salen–metal complexes and related bis-Schiff base metal complexes are among the most versatile catalysts for asymmetric transformations.121 Salen itself is a bis-Schiff base ligand formed in a single step from the reaction of ethylene diamine with two equivalents of salicylaldehyde and coordinates to a large variety of metal ions in a tetradentate ONNO-fashion upon deprotonation of the two phenolic OH groups. Often, the trans-coordination geometry is adopted which is devoid of a stereogenic metal center. However, due to some intrinsic flexibility resulting from two sp3-hybridized carbons in the backbone, the trans-geometry sometimes converts to the cis-β-geometry during catalysis, which features a stereogenic metal.10,122 For example, North and Belokon reported the titanium–salen complex trans-M37 as a catalyst for the enantioselective addition of Me3SiCN to benzaldehyde (60) to provide the cyanohydrin (S)-61 with 86% ee at room temperature with a catalyst loading of merely 0.1 mol % (Scheme 12a).123 Mechanistic investigations revealed that the trans-configured M37 is only a catalyst precursor and that small amounts of water in the solvent generate the oxygen-bridged dimeric complex [(salen)Ti(μ-O)]2 (cis-β-M38) in which salen is coordinated in a cis-β fashion.124 This dimeric cis-β-complex is much more active than the dichloride precursor trans-M37. At 0 °C, the reaction with M38 is complete after less than 5 min, providing 92% ee. The proposed mechanism takes into account that titanium–salen complexes can interconvert easily between the trans- and cis-β-geometry.125 Accordingly, the dimeric precatalyst cis-β-M38 is converted to the catalytic key intermediate X, in which substrate and isocyanide are coordinated at different titanium centers in close proximity to enable a nucleophilic addition of cyanide to benzaldehyde with high asymmetric induction, followed by a release of the product (X → XI → XII). Such an intramolecular attack is only possible when both titanium complexes are in the β-cis-geometry.

Scheme 12. Metallosalen Complexes for Asymmetric Catalysis via cis-β-Coordination Topology.

Likewise, Katsuki reported that the titanium–salen complex trans-M39 (devoid of a stereogenic metal center) is merely a precatalyst for enantioselective oxygenations of sulfides (Scheme 12b).126 The complex trans-M39 was converted to the corresponding dimeric (salen)Ti(μ-O)2] complex cis-β-M40 in the presence of water and base, which exhibits a cis-β-topology of the coordinated salen ligand with a stereogenic metal center. In the presence of H2O2, cis-β-M40 is supposed to be converted to the monomeric peroxo species cis-β-M41, which then effectively oxidizes sulfides to chiral sulfoxides. For example, sulfide 62 was converted to the chiral sulfoxide (S)-63 with 2 mol % of the catalyst cis-β-M40 in the presence of urea hydroperoxide (UHP) with 99% ee in 88% yield. Due to a decreased enantioselectivity when aqueous H2O2 was used, the authors concluded that the complex cis-β-M40 is in equilibrium with two hydroperoxo(hydroxo)titanium species in the presence of H2O, thus making the omission of water vital for a satisfactory enantioselectivity.126 Furthermore, mechanistic experiments and in-depth NMR spectroscopic studies supported the hypothesis that peroxo titanium(salen) complex cis-β-M41 is formed during the reaction and features a cis-β-coordination topology of the salen ligand around the titanium center, giving rise to metal-centered stereogenicity.127 In 2002, the same group also reported an enantioselective Baeyer–Villiger oxidation with a zirconium analogue by applying the same salen ligand.128

Unlike standard metallosalen complexes, bis-Schiff base ligands bearing an axially chiral biaryldiimine backbone prefer the cis-α- and/or cis-β-coordination geometry depending on the central metal.10,121,129−131 For example, Scott and co-workers reported that the ruthenium complex M42, synthesized by the reaction of the biaryldiimine ligand 64, with [{RuCl(μ-Cl)(η-C6H6)}2] in MeCN, adopts a cis-β-geometry (Scheme 13).132 (aS)-64 affords (aS)-cis-β-M42 with Λ-metal configuration and (aR)-64 affords (aR)-cis-β-M42 with Δ-configuration. The complex (aR)-cis-β-M42 (5 mol %) was employed as catalyst for the trans-selective enantioselective cyclopropanation of alkenes with ethyl diazoacetate. For example, the reaction of styrene (13) with ethyl diazoacetate (65) provided the cyclopropane (R,R)-66 with 94% yield, 95% ee and high trans:cis-selectivity of 98:2. DFT calculations support a mechanism in which an intermediate ruthenium carbene forms a chelate with the carbonyl group of the ester in which one diastereomeric face of the carbenoid is presented to the incoming alkene. Such a chelate binding of the intermediate carbene is only feasible in a cis-geometry of the tetradentate bis-Schiff base ligand.

Scheme 13. Scott’s Metallosalen Complex with Biaryl Backbone for Asymmetric Cyclopropanation.

In contrast to the described C2-symmetric salen ligands, C1-symmetric salalen ligands, in which one imine moiety is reduced to an amine, display a higher preference for the cis-β-topology due to enhanced flexibility of the sp3-hybridized nitrogen. Katsuki exploited this for the development of a powerful Ti(salalen) asymmetric epoxidation catalyst (Scheme 14).133 Accordingly, treatment of salen ligand (aR,S,S,aR)-67 with Ti(OiPr)4 in methylene chloride at room temperature for 3 days followed by treatment with water provided the dimeric di-μ-oxotitanium complex Δ,Δ-M43 in 60% yield. An X-ray diffraction analysis verified that the salen ligand was reduced in situ to a salalen ligand by a Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley (MVP) reduction and the homochiral metal centers adopt Δ-configurations. The authors mentioned that the metal-centered configuration is determined by the nature of the chiral ligand, its structural flexibility, and weak intra- and interligand interactions. The catalytic performance of this titanium salalen complex was then demonstrated in an enantioselective epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene (68). The catalysis was conducted with 1.01 equiv of aq H2O2 and a catalyst loading of 1 mol % in CH2Cl2 at rt for 12 h. The chiral oxirane 69 was obtained in >99% yield with >99% ee via the proposed intermediates XIII or XIV. Such epoxidations were previously not feasible with the related titanium–salen complexes.133

Scheme 14. Katsuki’s Titanium Salalen Catalyst for Asymmetric Epoxidation.

Chiral metal complexes from tetradentate P2N2 bis-Schiff base ligands are also able to switch the overall topology from trans to cis-β. For example, Mezzetti reported that the chiral ruthenium complex [RuCl2(PNNP)] (M44), which does not contain a stereogenic metal center due to the in plane trans-coordination of the tetradentate chiral diphosphinodiamine ligand PNNP, isomerizes to the cis-β-topology M45 upon replacement of the chloride ligands with ether (Scheme 15a).134M45 contains a stereogenic metal and was demonstrated to catalyze asymmetric Diels–Alder reactions, e.g., the β-ketoester 70 reacted with diene 71 to provide the tetrahydroindanone (S,S)-72 in 91% yield and with 93% ee in the presence of in situ generated M45 (10 mol %). A crystal structure of M45 coordinated to the β-ketoester 70 in a bidentate fashion (X-ray structure M46) provided insight into the reaction mechanism in which the ruthenium complex serves as a chiral Lewis acid to electronically activate the dienophile via bidentate coordination and provides the necessary asymmetric induction. The crystal structure revealed that one face of the coordinated substrate is shielded by one of the phenyl rings of the PNNP ligand so that the diene will attack the accessible Re-face of the metal-bound dienophile.

Scheme 15. Conversion of a Nonstereogenic into a Stereogenic Metal Center for Asymmetric Catalysis.

Mezzetti reported another case of ligand-induced isomerization of the tetradentate ligand sphere (Scheme 15b). In the chiral iron(II) complex M47, the metal center is coordinated to a chiral (NH)2P2 macrocycle135 in addition to trans-coordinated bromide and isonitrile. This chiral complex does not contain an asymmetric iron center. However, treatment of the bromoisonitrile complex M47 with NaBHEt3 gave the monohydride M48, in which the iron is coordinated by the (NH)2P2 macrocycle in a cis-β-topology, which renders the central iron stereogenic.136 The monohydride M48 was reported to be stable in THF solution under argon for many days and constitutes an excellent asymmetric transfer hydrogenation catalyst. For example, acetophenone (6) was converted to alcohol 7 in 92% yield and with 98% ee at 50 °C with just 0.1 mol % of M48 using iPrOH as the reducing agent without the necessity of employing a base.136

Other linear tetradentate chiral ligand architectures have been reported but often provided low enantioselectivities and are not discussed here.137,138 In a notable exception, Yamamoto introduced a class of bis(8-quinolinolato) metal complexes in which 1,1′-binaphthyl serves as a chiral linker between two 8-hydroxyquinoline ligands (Scheme 16a).139 Due to the rotational restrictions of the binaphthyl backbone and 8-hydroxyquinoline chelators, the reaction of ligand (aR)-73 with CrCl2 followed by air oxidation provides cis-β–Δ-(aR)-M49 as a single diastereomer with cis-β (fac-mer)-configuration of the tetradentate ligand and Δ-configuration at the Cr(III) center.140 The chromium(III) complex M49 has been demonstrated to catalyze asymmetric pinacol couplings. For example, benzaldehyde (60) was converted to the diol (R,R)-74 with 94% yield, 98:2 dr and 97% ee with M49 (3 mol %) using Mn as a reducing agent and TESCl (chlorotriethylsilane) as the product scavenger, followed by acid treatment to remove the silyl groups (Scheme 16b).

Scheme 16. Yamamoto’s Bis(8-Quinolinolato) Metal Catalysts with 1,1′-Binaphthyl Backbone.

2.4.3. Hexacoordinated Catalysts from Chiral Pentadentate Ligands

Only a few examples have been reported regarding chiral catalysts derived from pentadentate chiral ligands comprising a stereogenic metal center and often low to modest asymmetric inductions were reported. Ohno introduced a linear (sequential) pentadentate chiral ligand system based on bleomycin and synthesized different derivatives and their metal complexes.141 The iron(III) congener M50 of one of these complexes was reported to catalyze the epoxidation of (Z)-β-methylstyrene (75 → 76) with 57% ee in 30% yield (Scheme 17a). Interestingly, the iron analogue in oxidation state II provided the epoxide only with a reduced enantioselectivity of 33%.

Scheme 17. Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with Linear Chiral Pentadentate Ligands.

Klein Gebbink and co-workers reported the synthesis of a linear ligand containing a central bis-pyrrolidinylpyridine pincer unit and its subsequent complexation with an iron(II) precursor to form catalyst M51, which was employed in the asymmetric oxidation of aryl methyl sulfide such as 77 to form the corresponding sulfoxide (R)-78 with 27% ee (Scheme 17b).142

Aside from the helical topology derived from linear (sequential) pentadentate ligands, the majority of pentadentate chiral complexes derive their metal centered chirality from the coordination of nonlinear chiral tripodal ligands (Scheme 18). In 1993, Berkessel introduced a biomimetic pentadentate dihydrosalen (salalen) manganese(III) complex M52 with a chiral pentadentate ligand.143 This complex exhibits a square-pyramidal topology from which a stereogenic metal center arises due to the implementation of a chelating apical-coordinating group and the resulting desymmetrization of the salen-derived ligand. The vacant sixth coordination site of these complexes is expected to activate oxidants for the formation of intermediate octahedral manganese-oxo species during catalysis. Subsequently, the epoxidation of 1,2-dihydronaphthalene (68) with 10 mol % of M52 and H2O2 as the oxidant provided epoxide (1aS,7bR)-69 in 72% yield with an enantioselectivity of 64% ee (Scheme 18a). Following this promising result, they later synthesized various derivatives of this catalyst system for asymmetric epoxidations.144,145

Scheme 18. Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts with Branched Chiral Pentadentate Ligands.

In 2018, Sun introduced a tripodal, proline-derived, pentadentate ligand and demonstrated its predetermination of the metal center for the complexation with iron(II)146 and manganese(II).147 Despite the tertiary amine moiety bearing two identical methyl-pyridinyl groups, the facial coordination of this motif induces a stereogenic metal center with two possible diastereomers. Consequently, the chiral pyrrolidine determines the absolute configuration at the metal, thus enabling a diastereoselective complexation. Sun successfully applied the manganese complex M53 to an enantioselective catalytic epoxidation of chalcone (46) with 2 mol % catalyst loading, iodosylbenzene as oxidant, and 2-ethylhexanoic acid as additive to provide (2R,3S)-47 in 70% yield with up to 78% ee (Scheme 18b).147 They also reported an asymmetric stoichiometric sulfoxidation and C–H hydroxylation catalyzed by the iron congener of this system.146

Kaizer reported the synthesis of a nonheme iron(II) complex by coordination with a tetrapodal pentadentate ligand that is derived from the achiral tetrapyridyl ligand N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-N-bis(2-pyridyl)methylamine (N4Py) (M54) (Scheme 18c).148 The dipicolylamine subunit is binding in a facial fashion to the central metal. By incorporation of a chiral carbon center into the scaffold of the ligand, a tetrapodal arrangement of the ligand was obtained. Again, the chirality of the stereogenic metal center is imposed by the absolute configuration of the chiral ligand. The efficiency of complex M54 in asymmetric catalysis was depicted by the group in the enantioselective oxidation of 4-methoxythioanisole (79) to its chiral sulfoxide (R)-80 in high yield with 98% ee. The complex was later also applied to an asymmetric hydroxylation of ethylbenzene and other stoichiometric oxidation reactions.149−152

Recently, Meggers presented a tripodal pentadentate iron(II) complex featuring a stereogenic metal center (M55, Scheme 18d).153 Compared to the catalyst system of Sun, the dipicolylamine moiety exhibits a meridional arrangement resulting in a different overall topology of complex M55. Due to the three distinguishable “arms” of the tertiary amine, stereogenicity of the metal is induced upon coordination. By implementation of a chiral group into the backbone of the ligand, a thermodynamically controlled synthesis via isomerization of the thus formed diastereomers was achieved. Subsequently, this catalyst facilitated the ring contraction of isoxazole 81 in CH2Cl2 at low temperature to provide 2H-azirine (R)-82 in almost quantitative yield with 93% ee.

3. Stereogenic-at-Metal Catalysts from Solely Achiral or Optically Inactive Ligands (Chiral-at-Metal)

3.1. Considerations for Metal-Centered Stereogenicity from Solely Achiral or Optically Inactive Ligands

In 1911, Alfred Werner experimentally demonstrated the existence of metal-centered chirality by reporting the resolution of the racemic mixture of the octahedral cobalt(III) complexes [Co(en)2X(NH3)]2+ (X = Cl or Br, en = ethylenediamine) into their individual mirror-imaged Δ- and Λ-enantiomers (right- and left-handed helical twist, respectively) and verified their predicted optical activities.154 Thus, it has been already established more than 100 years ago that chiral metal complexes can be built entirely from achiral ligands. The assembly of the achiral or optically inactive ligands around the central transition metal generates a stereogenic metal center with an overall chiral topology of the metal complex.7−20 Such complexes have been designated as “chiral-at-metal”155−158 although this term is not used uniformly. We encourage to follow this denomination to indicate that the overall chirality formally originates from a stereogenic metal center and to distinguish this design approach from conventional stereogenic-at-metal complexes in which a stereogenic metal center is induced and complemented by a chiral ligand sphere. As a note, the metal coordination of optically inactive ligands (achiral or rapid interconverting enantiomers) sometimes results in the generation of other elements of chirality in the ligand sphere, such as stereogenic nitrogen-donor sites or axial chirality in a ligand backbone, in addition to the stereogenic metal center. These elements of chirality are dependent on the metal coordination.

The chiral-at-metal approach has the appeal of structural simplicity. More importantly, without the requirement of chiral motifs in the ligand sphere, untapped opportunities emerge for the design of novel catalyst architectures with potentially novel overall properties. However, while it is straightforward to synthesize chiral metal complexes which are composed entirely of achiral ligands, the development of chiral-at-metal catalysts is more challenging because the metal center does not only comprise the crucial stereogenic center responsible for the overall chirality but at the same time also constitutes the reaction center for catalysis. Thus, the ligand sphere must be chosen carefully to obtain a combination of inert and labile ligands without the risk of isomerization of the ligand sphere (e.g., pseudorotation) upon dissociation of a labile ligand. The strict configurational stability of the stereogenic metal center is at the heart of the chiral-at-metal concept.

The concept of using reactive chiral-at-metal complexes for asymmetric catalysis, in which the metal serves both as the sole stereogenic center and as the reactive center, was introduced by Fontecave in 2003.158 Fontecave reported that cis-[Ru(2,9-Me2-1,10-phen)2(MeCN)2](PF6)2 catalyzes the oxidation of organic sulfides to sulfoxides. The ligands were all achiral, but the cis-coordinated 1,9-phenanthroline ligands generate helical chirality with a Λ- or Δ-configured Ru center. However, the asymmetric induction was very low and only a maximum of 18% ee was obtained.

The development of chiral-at-metal catalysts which provide high enantioselectivities is only a very recent development. In 2013, Hartung and Grubbs reported a chiral-at-ruthenium catalyst for diastereo- and enantioselective ring-opening/cross-metathesis.159 In this chiral Ru catalyst, all employed ligands are achiral, although upon cyclometalation of the adamantyl NHC ligand, the sp3-carbon which is involved in the Ru–C bond, becomes a stereocenter. Starting with 2014,160 the Meggers group, followed by contributions from the groups of Gong, Kang, Xu, and Du, implemented and developed the generality of the chiral-at-metal approach by introducing different classes of chiral-at-metal catalysts based on the metals iridium, rhodium, ruthenium, and iron for a large variety of asymmetric transformations.20

3.2. Tetracoordinated Chiral-at-Metal Catalysts

Half-sandwich η5-cyclopentadienyl Fe and Re complexes in which the central metal was asymmetrically coordinated to four different achiral substituents in a pseudotetrahedral fashion were used in the 1980s by Davies,161,162 Liebeskind,163 Gladysz,164 and Brookhart156,157 as chiral auxiliaries and chiral reagents for a variety of asymmetric reactions. However, this is beyond the scope of this review because these chiral reagents did not act as catalysts. We are not aware of any chiral half-sandwich catalysts for asymmetric transformations in which the stereogenic metal center serves as the reaction center and at the same time is solely responsible for the overall chirality of the half-sandwich complex. This can be pinpointed to the typically limited configurational stability of such half-sandwich complexes. Interestingly, Ward, Rovis, and co-workers locked the configuration of a stereogenic-at-rhodium half-sandwich catalyst within the chiral pocket of a protein to perform catalytic asymmetric C–H activation chemistry, which is beyond the scope of this review.165,166

Shionoya’s group reported the only example so far of a tetrahedral, chiral-at-metal, asymmetric catalyst. Specifically, a configurationally surprisingly stable tetrahedral chiral-at-zinc complex was synthesized and demonstrated to serve as a chiral Lewis acid catalyzing an asymmetric oxa-Diels–Alder reaction.167 This was achieved using a carefully designed, unsymmetric, achiral, tridentate ligand 83 (Scheme 19a). Accordingly, reaction of 83 with ZnEt2 afforded the dimeric zinc complex rac-M56 as a racemic mixture. This racemic complex was reacted with the chiral pyrrolidine (S)-dpp (84), which coordinated to the zinc complex as a monodentate ligand to provide the complex (SZn,S)-M57 with a high diastereomeric excess (51:1 dr). NMR experiments revealed that upon coordination of (S)-dpp, the racemic zinc complex was initially converted to an approximately 1:1 mixture of diastereomers (SZn,S)- and (RZn,S)-M57, which then slowly converted to the thermodynamically more stable diastereomer (SZn,S)-M57, revealing a stereoinversion at the zinc center. To remove the chiral auxiliary ligand (S)-dpp, reaction with tBuCN at room temperature for 7 days caused the crystallization of (SZn)-M58 as a single enantiomer (>99% ee) in a yield of 72% starting from ligand 83. (SZn)-M58 features a stereogenic zinc center with four different coordinating groups.

Scheme 19. Tetrahedral Chiral-at-Zinc Complex for Asymmetric Hetero-Diels–Alder Reaction.

Although usually, zinc complexes are notorious for being rather labile, (SZn)-M58 features a surprising configurational stability in aprotic solvents which can be traced back to a very clever ligand design. Interestingly, the biphenyl backbone of the bidentate ligands adopts axial chirality upon coordination with a sterically hindered rotation around the C(sp2)–C(sp2) bond, thereby locking the zinc center in one configuration.167

The authors finally demonstrated that (SZn)-M58 (2 mol %) can catalyze the oxa-Diels–Alder reaction between 1-naphthaldehyde (85) and the Danishefsky diene 86 to afford the dihydropyranone (R)-87 in 98% yield with 87% ee (Scheme 19b). A crystal structure of 1-napthaldehyde coordinated to the (racemic) zinc catalyst, upon replacement of the labile tBuCN ligand, reveals the mechanism of asymmetric induction: The bulky mesityl group stacks with the 1-naphthylaldehyde and blocks the Si-face, so that the diene must approach the carbonyl group from the Re-face in the transition state (XV).167

3.3. Hexacoordinated Chiral-at-Metal Catalysts

3.3.1. Hexacoordinated Catalysts from Two Achiral Bidentate Ligands

In 2013, Hartung and Grubbs reported the first example of a highly enantioselective conversion, a highly Z-selective and enantioselective ring-opening/cross-metathesis, with a chiral-at-metal catalyst.159 The enantiomerically pure metathesis catalyst was obtained with the help of a chiral monodentate ligand as shown in Scheme 20a. Correspondingly, the racemic ruthenium complex rac-M59 was reacted with silver (S)-α-methoxyphenylacetate (88) to obtain the ruthenium carboxylate complex M60 as a mixture of the two diastereomers Δ-(S)-M60a and Λ-(S)-M60b, which were separated by chromatography or precipitation due to a large solubility difference of the two diastereomers to isolate Δ-(S)-M60a with >95:5 dr.159,168 A crystal structure of Δ-(S)-M60a revealed the clockwise helical topology of the cyclometalated NHC and bidentate carbene ligands in a hexacoordinated, distorted octahedral coordination sphere, thus leading to a Δ-configuration at the ruthenium center. Finally, the chiral carboxylate ligand was replaced with nitrate by treatment with p-TsOH followed by NaNO3 to provide enantioenriched Δ-M61.

Scheme 20. Enantioselective Olefin Metathesis with a Cyclometalated Chiral-at-Ru Complex.

Chiral-at-Ru complex Δ-M61 was shown to be a competent catalyst for asymmetric ring-opening/cross-metathesis (AROCM). For example, 1 mol % of Δ-M61 catalyzed the reaction of norbornene derivative 89 with excess allyl acetate (25) to provide the diene 90 in 64% yield with 95% Z-selectivity and 93% ee (Scheme 20b). In a follow-up study, the asymmetric ring-opening/cross-metathesis was applied to the catalytic, enantioselective synthesis of 1,2-anti diols.169 Asymmetric ring-closing metathesis (ARCM) of prochiral trienes and asymmetric cross-metathesis (ACM) of a prochiral 1,4-diene were also achieved.168

Bis-cyclometalated octahedral iridium(III) complexes have attracted significant attention due to their interesting photophysical properties and application in light-emitting diodes. These chiral complexes exhibit the topology depicted in Figure 4, thus rendering the iridium atom a stereogenic center. In 2014, Meggers demonstrated that chiral-at-iridium complexes bearing two cyclometalated 5-tert-butyl-2-phenylbenzoxazole and two labile acetonitrile ligands (Λ- and Δ-M62) are excellent chiral Lewis acid catalysts (Scheme 21).160,170 Enantiomerically pure complexes were synthesized using a chiral bidentate thiazoline ligand as a chiral auxiliary171−174 (Scheme 21a).160 Accordingly, starting from IrCl3, reaction with benzoxazole 91 afforded the cyclometalated racemic iridium(III) dimer rac-M63 in a diastereoselective fashion. The subsequent reaction of rac-M63 with the chiral auxiliary ligand (S)-4-isopropyl-2-(2′-hydroxyphenyl)-2-thiazoline ((S)-92) afforded the two diastereomeric complexes Λ-(S)-M64a and Δ-(S)-M64b, which were resolved by standard silica gel chromatography, followed by the conversion to virtually enantiopure Λ-M62 and Δ-M62 (each >99% ee), respectively, via substitution of the chiral auxiliary ligand with two acetonitrile ligands upon treatment with the weak acid NH4PF6.

Scheme 21. Initial Work by Meggers Using Bis-Cyclometalated Iridium Complexes as Chiral Lewis Acid Catalysts.

In the mirror-imaged Λ- and Δ-M62, two inert cyclometalating ligands implement a stereogenic metal center with either a left-handed (Λ-configuration) or right-handed (Δ-configuration) overall helical topology, while two labile acetonitrile ligands can be replaced by a substrate or reagent. Iridium(III) complexes tend to be highly configurationally inert so that there is no risk to compromise the chiral information implemented by the stereogenic metal center. Importantly, the lability of the monodentate acetonitrile ligands is assured due to a strong trans-effect induced by the cyclometalated ligands. In an initial catalytic application, Λ- and Δ-M62 were demonstrated to serve as chiral Lewis acids for an enantioselective conjugate addition of indoles to α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazoles. For example, the reaction of unsaturated 2-acyl imidazole 52 with indole (93), catalyzed by 1 mol % of Λ-M62, provided (S)-94 in 97% yield and with 96% ee (Scheme 21b).160 Mechanistically, bidentate N,O-coordination of the 2-acyl imidazole to the iridium center leads to an activation toward the nucleophilic attack of the indole (XVI). The C2-symmetric helical arrangement of the bis-cyclometalated iridium fragment perfectly shields the Re-face of the prochiral alkene, thus directing the indole to the Si-face and providing a high asymmetric induction.160

Subsequent work revealed that the related bis-cyclometalated complexes Λ- and Δ-M65 (Scheme 22), which differ from Λ- and Δ-M62 by replacing the benzoxazoles with benzothiazole ligands, typically provide even higher enantioselectivities.175 This can be rationalized with the longer C–S vs C–O bond lengths in benzothiazole vs benzoxazole, which positions the tert-butyl groups somewhat closer to the catalytic site and thus provides an improved steric hindrance. For example, using Λ-M65 instead of Λ-M62 as catalyst (1 mol %), the conjugate addition of indole (93) to the α,β-unsaturated 2-acyl imidazole 52 to provide (S)-94 occurred with almost perfect asymmetric induction (99% ee) (Scheme 22a, intermediate XVII).175 Very high enantioselectivities were also reported by Xu for an enantioselective α-fluorination of 2-acyl imidazole 95 using Selectfluor (96) to afford (S)-97 with 97% yield and 99% ee, which is supposed to proceed through an iridium enolate intermediate XVIII (Scheme 22b).176 Besides standard chiral Lewis acid catalysis, M65 was shown to catalyze asymmetric transfer hydrogenations of arylketones.177−179 For example, with 0.2 mol % of Λ-M65, 2-acetyl benzothiophene (98) was reduced to its alcohol 99 in 93% yield and with 99% ee using ammonium formate as the reducing agent (Scheme 22c).177 Even at a catalyst loading down to 0.005 mol %, quantitative conversion with 98% ee was obtained. Importantly, the reaction required the presence of a pyrazole coligand 100. Mechanistic experiments revealed that the pyrazole ligand binds to the iridium catalyst. Reaction with ammonium formate then generates an iridium hydride intermediate. With the assistance of the ancillary pyrazole ligand, a Noyori–Ikariya-type transition state (XIX) leads to a concerted transfer of a hydride to the carbonyl carbon and a proton to the carbonyl oxygen.177

Scheme 22. Bis-Cyclometalated Benzothiazole Iridium Complexes for Asymmetric Catalysis.

Bis-cyclometalated iridium complexes are used extensively as photoredox catalysts or photosensitizers in modern organic photochemistry. With respect to asymmetric photochemistry, photocatalysts such as bis-cyclometalated iridium complexes, are usually combined with a chiral catalyst to perform dual catalysis.180−183 Interestingly, Meggers reported several studies in which M62 or M65 were used as a single catalyst for asymmetric photoredox catalysis.184−188 For example, the radical α-alkylation of 2-acyl imidazole 101 with the electron deficient benzyl bromide 102 induced by visible light provided (R)-103 in quantitative yield with 99% ee (Scheme 22d, via enolate intermediate XX).184

While M65 remains the benchmark for chiral-at-iridium catalysis, a number of related bis-cyclometalated iridium complexes were introduced for applications in asymmetric catalysis including polymer-supported, bis-cyclometalated iridium catalysts,189 bis-cyclometalated NHC iridium catalysts,190,191 and bis-cyclometalated indazole and benzimidazole chiral-at-iridium catalysts.192

In 2015, Meggers introduced bis-cyclometalated chiral-at-rhodium(III) complexes as chiral Lewis acids, some of which are displayed in Scheme 23.193 Λ- and Δ-M66, which are the lighter congeners of Λ- and Δ-M62, contain two inert cyclometalated 5-tert-butyl-2-phenylbenzoxazoles in addition to two labile acetonitrile ligands with hexafluorophosphate serving as the counterion for the monocationic complexes. Scheme 23a displays that Λ-M66 at a loading of 0.2 mol % catalyzes the enantioselective α-amination of 2-acyl imidazole 101 with dibenzyl azodicarboxylate (104) to provide the α-amination product (R)-105 with 88% yield and 96% ee.193 Meggers, Gong, and particularly Kang and Du demonstrated the versatility of Λ- and Δ-M66 and its derivatives to serve as chiral Lewis acid catalysts for a large variety of reactions.194−214 The related benzothiazole complexes Λ- and Δ-M67,215 which are the lighter congeners of iridium-based Λ- and Δ-M65 and its derivatives, are for many applications even more powerful chiral Lewis acids providing typically higher enantioselectivities.215−217 Importantly, compared to the related bis-cyclometalated iridium catalysts, the rhodium catalysts feature much higher ligand exchange rates by several orders of magnitude.218 This is a significant advantage because ligand exchange reaction (e.g., coordination of substrate and release of product) are often the rate limiting steps in a catalytic cycle and, thus, determine the overall turnover frequency.

Scheme 23. Bis-Cyclometalated Rhodium Complexes for Asymmetric Catalysis.

The bis-cyclometalated rhodium complexes are also excellent catalysts for asymmetric photochemistry, either in a setting of dual catalysis219−228 or as single catalysts.229−237 For example, Meggers demonstrated direct visible-light excited highly asymmetric M67-catalyzed [2 + 2] photocycloadditions (e.g., 106 + 107 → 108, Scheme 23b),238 while Kang reported a visible-light-induced asymmetric conjugate radical addition catalyzed by a 3,5-(CF3)2Ph-modified catalyst M68 (e.g., 109 + 110 → 111, Scheme 23c).239 A bis-cyclometalated rhodium indazole complex (M69)240 was recently demonstrated to catalyze the α-photoderacemization of pyridylketone 112 (Scheme 23d).241

Furthermore, bis-cyclometalated rhodium complexes are also suitable catalysts for combining electrochemistry with asymmetric catalysis.242,243 For example, Meggers recently reported that a bulkier derivative of M67 in which the tert-butyl groups are replaced with trimethylsilyl group (M70) catalyzes the oxidative cross-coupling of racemic 2-acyl imidazole 113 with silyl enol ether 114 to provide an avenue to nonracemic 1,4-dicarbonyl 115 (Scheme 23e).242

While all the discussed bis-cyclometalated iridium and rhodium complexes are C2-symmetric, Meggers introduced the non-C2-symmetric rhodium complex M71, bearing two different cyclometalated ligands, and demonstrated its merit in an enantioselective α-chlorination of 2-acyl pyrazole 116 to (S)-117 while comparable C2-symmetric catalysts gave inferior results (Scheme 23f).244−246

In 2017, Meggers reported a new class of chiral-at-ruthenium catalysts in which two bidentate N-(2-pyridyl)-substituted N-heterocyclic carbenes (PyNHC) and two acetonitrile ligands are coordinated to a central ruthenium in a C2-symmetrical fashion (Scheme 24a).247 The implementation of two bidentate ligands introduces helical chirality to the complexes despite all ligands being achiral. The PyNHC ligands are key components of the overall design. First, they are tightly coordinating ligands which provide a strong ligand field important for the constitutional and configurational stability of the bis(PyNHC)Ru unit. Second, the strong σ-donating NHC ligands are crucial for labilizing the trans-coordinated acetonitrile ligands (trans-effect), thereby ensuring a high catalytic activity. The reported synthesis is in analogy to the synthesis of chiral-at-iridium and chiral-at-rhodium complexes by using chiral bidentate ligands as auxiliaries for resolving metal-centered stereoisomers. In initial reports, catalyst M72 was demonstrated to catalyze the alkynylation of trifluoromethylketones 118 with phenylacetylene (34) to provide propargylic alcohol (S)-119 with very high enantioselectivities at catalyst loadings down to 0.2 mol % and was applied to the highly efficient, enantioselective synthesis of key propargylic alcohol intermediates of the anti-HIV drug efavirenz.247,248 A computational study by Houk supports a mechanism involving the intramolecular delivery of a ruthenium acetylide to a coordinated ketone through a highly compact four-membered transition state.249 In this transition state, both substrates are coordinated to the stereogenic ruthenium center, which is crucial for obtaining a high asymmetric induction. Subsequently, it was revealed that this class of chiral-at-ruthenium catalysts is highly suitable for catalyzing enantioselective, intramolecular C(sp3)-H aminations via ruthenium nitrene intermediates,250−253 including the enantioselective intramolecular C(sp3)-H amination of N-benzoyloxyurea 120 to provide chiral 2-imidazolidinone (S)-121 using catalyst M73.253 Ruthenium nitrene chemistry was also applied to a C(sp3)-H oxygenation254 and asymmetric ring-closing aminooxygenation of alkenes.255

Scheme 24. C2-Symmetric and Non-C2-Symmetric Octahedral Chiral-at-Ruthenium for Asymmetric Catalysis.

While catalysts M72 and M73 are C2-symmetric, Meggers recently introduced the non-C2-symmetric chiral-at-ruthenium catalyst M74 which was demonstrated to be a highly active catalyst for intramolecular C(sp3)-H amidations of 1,4,2-dioxazol-5-ones to provide chiral γ-lactams with catalyst loadings down to 0.005 mol % (e.g., 122 → (S)-123, Scheme 24b).256 Interestingly, the C2-symmetric diastereomer provides mainly Curtius rearrangement, thus emphasizing the importance of the relative metal-centered configuration not only regarding the steric hindrance but also its influence on the electronic attributes of the final catalyst.