Abstract

Forest and other upland soils are important sinks for atmospheric CH4, consuming 20 to 60 Tg of CH4 per year. Consumption of atmospheric CH4 by soil is a microbiological process. However, little is known about the methanotrophic bacterial community in forest soils. We measured vertical profiles of atmospheric CH4 oxidation rates in a German forest soil and characterized the methanotrophic populations by PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) with primer sets targeting the pmoA gene, coding for the α subunit of the particulate methane monooxygenase, and the small-subunit rRNA gene (SSU rDNA) of all life. The forest soil was a sink for atmospheric CH4 in situ and in vitro at all times. In winter, atmospheric CH4 was oxidized in a well-defined subsurface soil layer (6 to 14 cm deep), whereas in summer, the complete soil core was active (0 cm to 26 cm deep). The content of total extractable DNA was about 10-fold higher in summer than in winter. It decreased with soil depth (0 to 28 cm deep) from about 40 to 1 μg DNA per g (dry weight) of soil. The PCR product concentration of SSU rDNA of all life was constant both in winter and in summer. However, the PCR product concentration of pmoA changed with depth and season. pmoA was detected only in soil layers with active CH4 oxidation, i.e., 6 to 16 cm deep in winter and throughout the soil core in summer. The same methanotrophic populations were present in winter and summer. Layers with high CH4 consumption rates also exhibited more bands of pmoA in DGGE, indicating that high CH4 oxidation activity was positively correlated with the number of methanotrophic populations present. The pmoA sequences derived from excised DGGE bands were only distantly related to those of known methanotrophs, indicating the existence of unknown methanotrophs involved in atmospheric CH4 consumption.

The atmospheric concentration of CH4, one of the most important greenhouse gases, has increased dramatically over the past 200 years. About 80 to 90% of atmospheric CH4 is of biogenic origin (20). The major sink is the chemical destruction by OH⋅ and Cl⋅ radicals in the troposphere and stratosphere, respectively (9, 10). However, the capacity of these atmospheric sinks may decline, since the rising concentrations of other trace gases emitted by anthropogenic activity result in a reduction of OH⋅ radicals in the troposphere (27).

The only biological sink for CH4 is oxidation in soil. Atmospheric CH4 is consumed in forest, agricultural, and other upland soils. CH4 consumption in these soils is caused by methane-oxidizing bacteria. However, the identity of these methanotrophs is still unknown. The apparent half-saturation constant (Km) for oxidation of atmospheric CH4 (approximately 1.8 parts per million by volume [ppmv]) in upland soils ranges from 0.8 to 280 nM (6, 7, 13, 16). However, the Km of the common type I or II methanotrophs (0.8 to 66 μM), which are available in culture collections, is 1 to 3 orders of magnitude higher, and these common methanotrophs are not able to survive for a prolonged period using only atmospheric CH4 (14, 17, 37). Recently, however, a type II methanotroph was isolated from a humisol that was able to adapt to nanomolar Km values, close to those measured in upland soils (14; P. Dunfield, personal communication). The existence of this isolate brought into question the hypothesis of Bender and Conrad (6) that besides the common low-affinity methanotrophs (micromolar Km), unknown high-affinity methanotrophs (nanomolar Km) exist and that only the latter are responsible for atmospheric CH4 oxidation.

Common methanotrophs have a neutral pH optimum (18). However, most forest soils are slightly acidic, around pH 5 and lower. Bacteria extracted from forest soils showed a methanotrophy pH optimum of 5.8, indicating that unknown acidophilic methanotrophs may be responsible for CH4 oxidation in forest soils (5). Indeed, an acidophilic methanotroph, belonging to the α proteobacteria and closely related to the nonmethanotroph Bejerinckia but only distantly related to the common type II methanotrophs, was recently isolated from an acidic blanket peat bog in Russia (11, 12).

However, so far little is known about the methanotrophic community in forest soil. A recent analysis of pmoA gene libraries from forest soils has demonstrated the existence of a new group of methanotrophs in various forest soils (23). These soils all exhibited uptake of atmospheric CH4.

Forest soils have been extensively studied with respect to CH4 oxidation kinetics and zonation and inhibition of CH4 oxidation because of their important function as major sinks in the global CH4 budget. The highest CH4 oxidation activity in forest soils was usually measured in subsurface soil layers (1, 29, 33, 38). This localization of methanotrophs in deeper soil layers was attributed to inhibition of methanotrophs by ammonium or terpenes that are released or produced in the organic surface layers of the forest soil (2–4, 16, 26, 36). However, the zonation of CH4 oxidation in relation to the involved methanotrophic community has not yet been studied.

Therefore, we measured vertical profiles of the uptake of atmospheric CH4 in forest soil cores in winter and summer and characterized the bacterial and involved methanotrophic populations by PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) using a universal small-subunit rRNA gene (SSU rDNA) primer set and a primer set targeting the pmoA gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling site and soil characteristics.

The sampling site was located on a slope in a deciduous forest near Marburg, Germany (N 51°00.000′, E 09° 50.625′), consisting of mainly beech (Fagus sylvatica) and oak (Quercus robur). The soil type was a cambisol with a Ah (2 to 6 cm), Bv (6 to 28 cm), and C (sandstone) horizon. The soil originated on sandstone and was a loamy sand. The pHH2O values of the organic Ah horizon and the mineral subsoil were pH 3.8 and pH 4.3, respectively. Soil cores were collected in January (winter) and July (summer) of 1999.

The maximal water-holding capacity (WHC) was determined for the organic soil (Ah) and the mineral subsoil (Bv) by the method of Schlichting & Blume (35), and the values were 0.46 ± 0.04 and 0.39 ± 0.02 g of H2O g (dry weight) of soil−1 (n = 5), respectively (35). The gravimetric water content was determined for each 2-cm vertical soil section and expressed as a percentage of WHC.

Vertical CH4 concentration profiles.

Gas samples were taken by pushing a PEEK capillary (diameter, 0.35 mm; Sykam, Gilchingen, Germany) attached to a stainless steel rod into the soil at 1-cm intervals. Prior to sampling, the tube was flushed by extracting 0.1 ml of gas. Gas samples (1 ml) were collected in gastight syringes and analyzed by gas chromatography with a GC-8A (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a stainless steel column (length, 2 m; diameter, 1/8 inch) filled with Poropak Q (80/110 mesh).

Collection of soil cores and in vitro CH4 oxidation rate.

Soil cores were taken with Plexiglas corers (diameter, 6 cm) pushed into the forest floor. The columns were extracted from the ground and closed with silicone stoppers. In the laboratory, the cores were gently pushed upward and cut into 2-cm sections. The sectioned soil layers were immediately transferred into 150-ml serum bottles, which were closed with latex stoppers.

Gas samples were repeatedly taken over time with gastight pressure-lock syringes (A-2 series; Dynatech, Baton Rouge, La.) and analyzed by gas chromatography. Apparent first-order CH4 oxidation rate constants were calculated (Excel 7.0; Microsoft) from the exponential decrease of CH4 with time and converted to CH4 oxidation rates by multiplication with the atmospheric CH4 mixing ratio (1.7 ppmv).

DNA extraction.

DNA extraction from forest soil was modified from the method of Moré et al. (31). Approximately 0.5 g (fresh weight) of soil was taken from each forest soil layer (2 cm thick) and transferred into 2-ml screw cap tubes. Approximately 1 g of sterilized (170°C for 4 h) zirconia/silica beads (diameter, 0.1 mm; Biospec Products Inc., Bartlesville, Okla.), 800 μl of 120 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8), and 260 μl of sodium dodecyl sulfate solution (10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M NaCl) were added, and the soil was resuspended homogeneously by vortexing. The cells were lysed for 45 s by shaking in a cell disruptor (FP120 FastPrep; Savant Instruments Inc., Farmingdale, N.Y.) at a setting of 6.5 m s−1. After centrifugation (3 min at 12,000 × g), the supernatant was collected and the soil-bead mixture was extracted a second time by resuspension in 700 μl of sodium phosphate buffer. Protein and debris were precipitated from the supernatant by adding 0.4 volume of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and incubating the mixture on ice for 5 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 3 min, nucleic acids were precipitated by adding 0.7 volume of isopropanol and centrifuging the mixture at 12,000 × g and 4°C for 45 min. Subsequently, the DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol at 4°C and dried under vacuum. Finally, DNA was resuspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]).

Removal of humic acids.

The forest soil DNA extracts were dark brown and contained large amounts of humic acids. The humic acids were removed with acid-washed polyvinyl-polypyrrolidone (PVPP) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany) in spin columns (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) modified from the method of Holben et al. (21). The spin columns were filled with 2 ml of PVPP, which had been equilibrated and suspended in Tris-EDTA (pH 8). The PVPP columns were packed and dried by centrifugation (375 × g for 1 min) just prior to loading. About 150 μl of the brown humic acid-containing soil DNA extract was loaded onto the column and centrifuged. The purified DNA solution was clear and colorless and readily amplifiable by PCR.

The concentration and purity of the DNA solutions were determined by measurement of absorption at 260 and 280 nm, after 1:10 dilution in H2O, using a GeneQuant spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). For PCR amplification, DNA aliquots at a standardized DNA concentration of 1 ng μl−1 were used.

PCR amplification.

For PCR amplification, we used a universal SSU rRNA-based primer set, targeting all life, and the functional primer set pmoA (19).

PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl), 1 U and 0.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase for the pmoA and the universal primer set, respectively (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany), 0.5 μM each primer, and 100 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Amersham Life Science, Braunschweig, Germany) were added to a total reaction volume of 50 μl at 4°C. For the pmoA amplification, MasterAmp 2× PCR premix F containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), MgCl2, 400 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and the PCR enhancer betaine (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) were added to the reaction solutions. The same template concentration (1 to 5 ng μl−1) was always used in a set of PCR amplifications from the same soil core. Amplifications were started by placing cooled (4°C) PCR tubes immediately into the preheated (94°C) thermal block of a Mastercycler Gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The thermal cycling profiles consisted of touchdown programs with an initial denaturation of 3 min at 94°C followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at the annealing temperature, and 45 s at 72°C, with 5 min at 72°C for the last cycle. The annealing temperature decreased from 62 to 55°C and from 60 to 50°C in 0.5°C steps for the pmoA and universal primer sets, respectively.

Aliquots (5 μl) of PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified densitometrically. The gels were destained in water for 30 min. For calibration, the Smart-Ladder DNA mass and size ruler (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) was used (calibration coefficient of all analyses, r > 0.9). The gels were photographed with an imaging system (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany), and DNA bands were analyzed with RFLP-scan software (CSP Inc., Billerica, Belgium).

DGGE.

DGGE was carried out as described previously in detail (19). PCR products were separated using a DCode System (Bio-Rad) on 1-mm-thick polyacrylamide gels (6.5% [wt/vol] acrylamide-bis acrylamide [37.5:1] [Bio-Rad]) prepared with and electrophoresed in 0.5× TAE (pH 7.4) (0.04 M Tris base, 0.02 M sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA) at 60°C and constant voltage. A denaturing gradient of 35 to 80% and 35 to 70% was used for the pmoA and Universal PCR products, respectively. A denaturing gradient of 80% (vol/vol) denaturant corresponded to 6.5% acrylamide, 5.6 M urea, and 32% deionized formamide. The gels were poured onto GelBond PAG film (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) to avoid gel distortion. The gels were stained with 1:50,000 (vol/vol) SYBR-Green I (Biozym, Hessisch-Oldendorf, Germany) for 30 min and scanned with a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The scanned DGGE gels were digitally enhanced with Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe Systems Inc.) to improve graphic resolution of the figures.

For further analysis, the DGGE bands were visualized in the SYBR Green I-stained gels with blue light (λ > 400 nm) using a Dark Reader transilluminator (Clare Chemical Research, Ross on Wye, United Kingdom). Individual DGGE bands were then excised, reamplified, and reanalyzed by DGGE to verify band purity, as described recently (19).

Sequencing of DGGE bands.

Reamplified PCR products of excised DGGE bands were purified using the EasyPure DNA purification kit (Biozym, Hessisch-Oldendorf, Germany). The concentration and purity of the PCR products were determined by measuring the absorption at 260 and 280 nm of a 1:20 dilution in H2O with a GeneQuant spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech). Sequencing reactions were performed using the ABI Dye Terminator cycle-sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) as specified by the manufacturer. Cycle-sequencing products were purified from excess dye terminators and primers using Microspin G-50 columns (Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and analyzed with an ABI 373 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems).

Sequences were analyzed using the Lasergene software package (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.). The nucleotide and inferred amino acid sequences of the gene fragments of pmoA were manually aligned with sequences retrieved from the GenBank database. SSU rDNA sequences were aligned and phylogenetically placed with the ARB software package (http://www.biol.chemie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB). The partial SSU rDNA sequences were added to a validated and optimized tree of complete 16S rDNA sequences while keeping the overall topology constant (30). On the nucleic acid level, evolutionary distances between pairs of sequences were calculated by using the Jukes-Cantor and Felsenstein equations (15, 25) provided in the ARB package. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using distance matrix and maximum-parsimony methods supplied by the ARB software package.

Nucleotide accession numbers.

The sequences of pmoA gene fragments and of the SSU rDNA fragments of excised DGGE bands have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF200726 to AF200729 and AF200730 to AF200734, respectively.

RESULTS

CH4 consumption rates by forest soil.

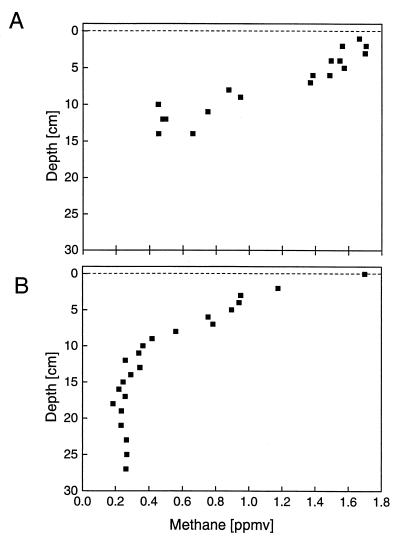

In situ CH4 mixing ratios decreased with soil depth both in winter and in summer (Fig. 1). In winter, the CH4 mixing ratios showed a quasi-linear decrease with soil depth (Fig. 1A). The scattering of the data was too large to determine the zone of CH4 oxidation with certainty, but it was probably at the lower end of the profile. In summer, the in situ profile showed a quasi-linear decrease in CH4 mixing ratios from 0 to about 8 cm deep (Fig. 1B). Below 16 cm deep, the in situ CH4 mixing ratios remained constant at approximately 0.25 ppmv CH4. The shape of the vertical CH4 profile indicated CH4 oxidation at about 8 to 15 cm deep. The forest soil was always a net sink for atmospheric CH4, exhibiting a CH4 consumption rate of 1.00 ± 0.26 mg m−2 day−1 (mean ± standard deviation [SD] of three determinations) in winter. Similar values were reported previously (1, 29, 38).

FIG. 1.

Vertical profiles of in situ CH4 mixing ratios in forest soil in winter (January 1999) (A) and in summer (July 1999) (B).

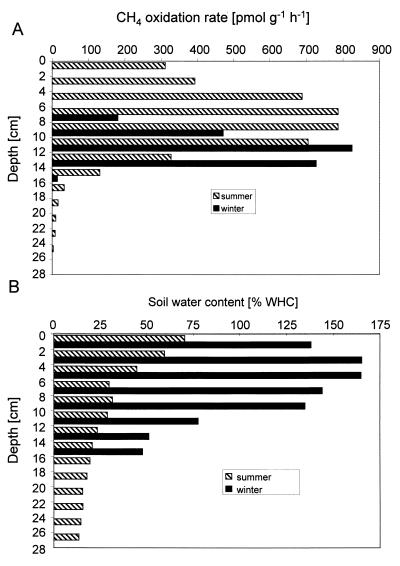

The in vitro CH4 oxidation rates were measured in distinct 2-cm soil sections between 0 and 16 cm deep in winter and 0 and 28 cm deep in summer (Fig. 2A). In winter, no CH4 consumption was detected between 0 and 6 cm deep. CH4 oxidation started at 6 cm deep, and maximal oxidation rates were measured between 10 and 14 cm deep. The oxidation rates sharply decreased below 14 cm deep. The activity-depth profiles had the same shape in two replicate cores taken from the same site, but the magnitude of the CH4 oxidation rates differed among the three replicates by a factor of <4 (data not shown). In summer, CH4 oxidation activity was detected between 0 and 26 cm deep. Maximal oxidation rates were measured between 4 and 10 cm deep; the CH4 oxidation rates decreased sharply below 12 cm deep and ceased below 26 cm. The activity was measured in triplicate aliquots taken from the same soil core (Fig. 2A). The coefficient of variation of the rates measured in the individual soil sections was between 4 and 22%.

FIG. 2.

Vertical profiles of CH4 oxidation rates per gram of fresh soil (A) and soil water content (B) in winter and summer. The CH4 oxidation rates in winter are from single measurements, whereas those in summer are means of triplicates (coefficient of variation = 4 to 22%).

The water content of the loamy sand decreased with depth. In winter, the water content exceeded 100% WHC between 0 and 10 cm deep and dropped to about 50% WHC below 12 cm deep. In summer, the forest soil exhibited a water content of approximately 70% WHC at the surface (0 to 2 cm), decreasing to approximately 13% WHC below 26 cm deep (Fig. 2B).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification.

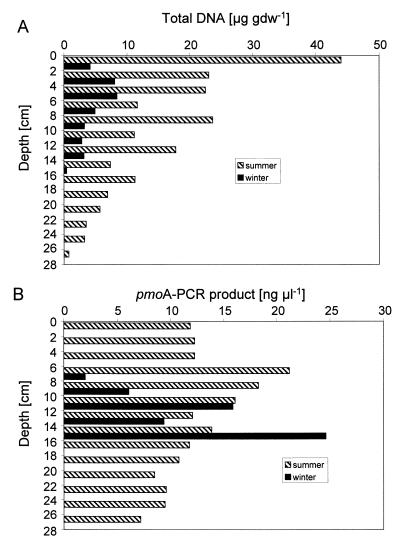

The same soil core sections that were used for measurement of the CH4 oxidation activity shown in Fig. 2 were also used for DNA extraction. Up to 10 times more total DNA was extracted from the forest soil in summer than in winter (Fig. 3A). The total extractable DNA content of the soil decreased with depth, both in winter and in summer, but the decrease was more pronounced in summer (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Vertical profiles of the total extractable DNA content per gram of dry soil (A) and the pmoA concentration of the PCR products from each soil section (B) in winter and summer. In winter, DNA was analyzed only between 0 and 16 cm deep; no pmoA was detected between 0 and 6 cm deep.

PCR with the universal primer set, targeting the SSU rDNA of all life, amplified PCR products from all depth layers in winter (25.7 ± 4.9 ng μl−1 [mean ± SD of 8 determinations]) and summer (29.5 ± 11.5 ng μl−1 [mean ± SD of 13 determinations]) at similar concentrations, indicating that DNA from all soil layers was readily amplifiable and was not subjected to different biases caused by humic acids or other PCR-inhibiting substances.

In contrast to the universal primer set, PCR with the primer set pmoA yielded product concentrations depending on the soil depth and season. In winter, pmoA was detected only in a well-defined layer between 6 and 16 cm deep, with the highest PCR product yield being found between 14 and 16 cm deep (Fig. 3B). No pmoA was detected in the top 6 cm of soil. In summer, on the other hand, pmoA was detected and amplified between 0 and 28 cm deep, with the highest PCR product yield being found between 6 and 8 cm deep (Fig. 3B). The pmoA gene was detected only in soil layers with CH4 oxidation activity, indicating that the presence of the pmoA gene, and thus of methanotrophs, coincided with the measured activity (Fig. 2A and 3B).

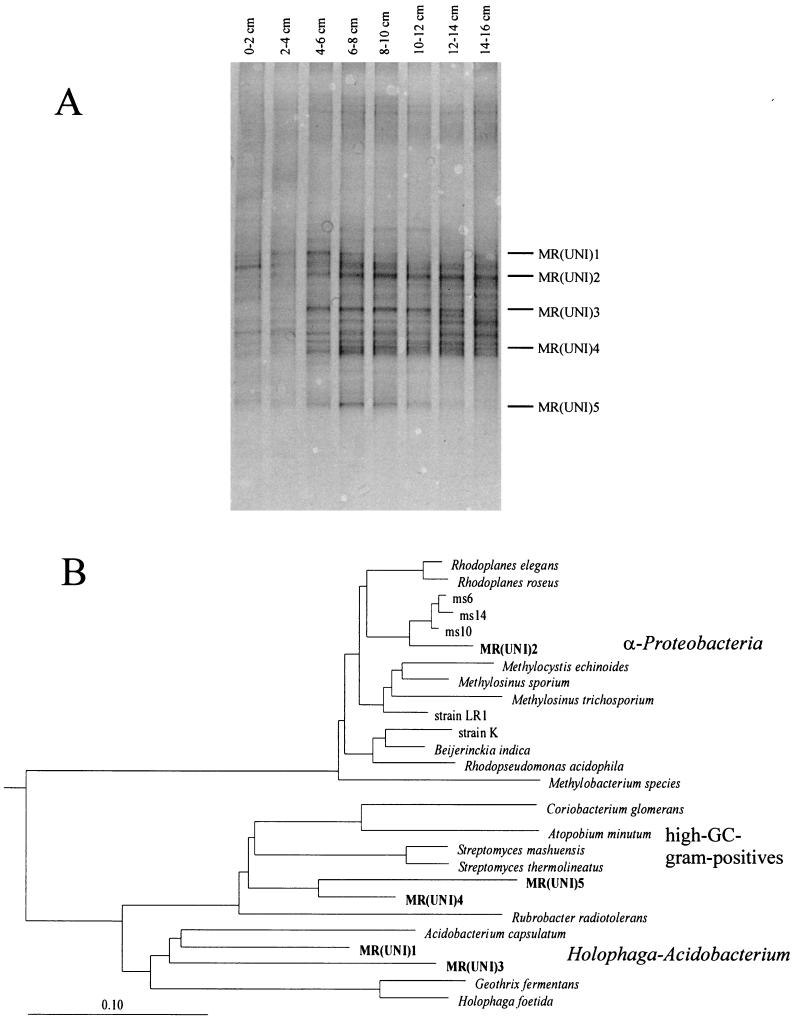

SSU rDNA DGGE community pattern.

The DGGE analysis of PCR products amplified with the universal primer set was conducted only in winter (in soil from 0 to 16 cm deep) and revealed a complex banding pattern, reflecting the high microbial diversity expected for forest soil (Fig. 4A). The number and intensity of DGGE bands increased below a soil depth of 2 cm. The DGGE banding pattern changed at different soil depths, indicating changes of the bacterial community structure with depth. The intensity of the DGGE bands indicated the presence of about 11 dominant populations within the layer of highest diversity (6 to 10 cm deep). Sequence analysis of five major DGGE bands revealed two populations [MR(UNI)4 and MR(UNI)5] grouping within the phylum of high-GC gram-positive bacteria, two populations [MR(UNI)1 and MR(UNI)3] closely related to the phylum Holophaga-Acidobacterium, and one population [MR(UNI)2] grouping within the α proteobacteria (Fig. 4B). The latter population [MR(UNI)2] was the most closely related to clones ms14, ms6, and ms10, which were retrieved from a peat bog with primers specific for methanotrophs (accession numbers AF111789, AF111787, and AF111788) (I. McDonald and C. Murrell, personal communication).

FIG. 4.

(A) DGGE pattern obtained with the universal SSU rDNA primer set. (B) Phylogenetic tree constructed with partial 16S rDNA sequences of the marked DGGE bands from the forest soil core sampled in winter. The phylogenetic tree shows the relationships of the marked DGGE bands to members of the domain Bacteria. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of base changes per nucleotide sequence position; the following 16S rDNA sequences (accession numbers) were taken from data banks: ms6, ms10, and ms14 are clones from a peat bog retrieved with primers specific for methanotrophs (AF111789, AF111787, and AF111788); strain LR1 is a high-affinity type II methanotroph (Y18442); strain K is an acidophilic methanotroph (Y17144).

pmoA DGGE community pattern.

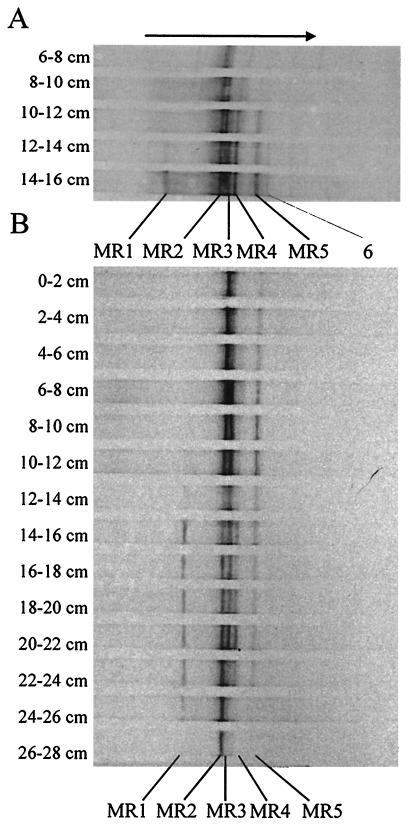

The DGGE analysis of PCR products amplified with the pmoA primer set was performed on soil samples taken in winter (0 to 16 cm deep) and in summer (0 to 28 cm deep). In winter, DGGE bands of pmoA products were detected between 6 and 16 cm deep, and the number of DGGE bands increased from one to six between 6 and 16 cm deep (Fig. 5A). In the soil layer (10 to 14 cm deep) with the highest CH4 oxidation rates, the DGGE bands MR2, MR3, MR4, and MR5 were the most intense.

FIG. 5.

DGGE pattern obtained with the pmoA primer set targeting the gene of the α subunit of particulate methane monooxygenase in winter (A) and in summer (B). The arrow shows the direction of increasing denaturant and electric field. Bands MR1 to MR5 were sequenced; band 6 was not sequenced.

In summer, DGGE bands of pmoA were detected between 0 and 28 cm deep. The number of DGGE bands increased from one to six between 0 and 16 cm deep, and then decreased again to only one band below 24 cm deep. The soil layers with maximal CH4 oxidation activity (4 to 12 cm deep) (Fig. 2A) coincided with those showing the highest PCR product yield of pmoA (6 to 12 cm deep) (Fig. 3B) and those with the most intense DGGE bands (MR2, MR3, and MR5) (6 to 12 cm deep) (Fig. 5B). The band for MR2 was present in all the layers, indicating that MR2 was the most dominant and widely distributed methanotrophic population. The band for MR4 was most intense at 12 to 24 cm deep (Fig. 5B). The band for MR1 appeared only below 14 cm deep, both in winter and in summer.

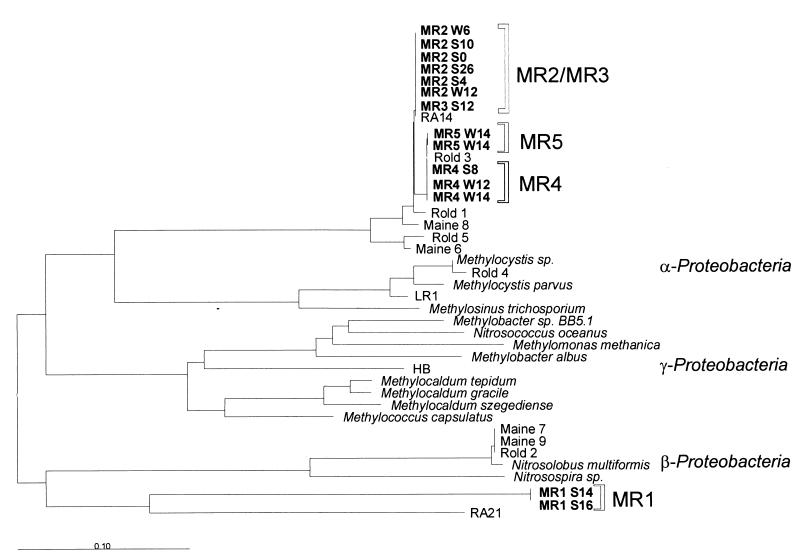

Sequence analysis was performed with the DGGE bands MR1 to MR5 (Fig. 6). DGGE band MR1 grouped among the β proteobacteria and was closely related to the ammonium-oxidizing genus Nitrosospira. DGGE bands MR2 to MR5 formed a distinct group of methanotrophs distantly related to common type II methanotrophs (α proteobacteria). These sequences were very similar and clustered with pmoA clone sequences (Rold 1, 3, and 5; Maine 6, 8, and RA14) recently retrieved from other forest soils (23).

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic tree based on the derived amino acid sequences of pmoA and amoA fragments, showing the relation of the pmoA sequences (MR1 to MR5) retrieved from forest soil to pmoA and amoA sequences of other methanotrophs and ammonium oxidizers. Bands of the same electrophoretic mobility were repeatedly sequenced from different DGGE gels and lanes (soil depths) to prove sequence identity. Sequences were labeled according to the DGGE band position (MR1 to MR5), the season of sampling (W, winter; S, summer), and the soil depth (in centimeters). The scale bar indicates the estimated number of changes per amino acid sequence position. The pmoA sequences Rold, Maine, and RA are novel pmoA sequences retrieved from forest soils (23); LR1 is a high-affinity type II methanotroph (Y18443); and HB is a thermophilic methanotroph (U89302).

DISCUSSION

Atmospheric CH4 oxidation has been extensively studied in various upland soils. However, little is known about the methanotrophic community involved. By studying the vertical distribution of both the oxidation of atmospheric CH4 and the molecular characteristics of methanotrophic populations in an acidic forest soil, we detected a methanotrophic community distinct from known type I and II methanotrophs and occurring only in the soil layers which were actively oxidizing atmospheric CH4. The pmoA sequences of this methanotrophic community clustered distantly from the known methanotrophs and grouped with pmoA clone sequences recently retrieved from other forest soils involved in atmospheric CH4 consumption (23).

The forest soil examined in this study consumed atmospheric CH4 at all times. The soil showed a quasi-linear decrease of CH4 with depth, and, as reported for other forest soils, maximal CH4 consumption occurred in subsurface soil layers (1, 29, 33, 38). In winter, no CH4 consumption was measured in the surface layer (0 to 6 cm deep) and no methanotrophs were detected by DGGE with pmoA. One reason for the missing CH4 consumption might be the high water content in winter, which exceeded saturation (>100% WHC). Methane was not produced in the soil, in contrast to observations in other upland soils (13, 28). Therefore, atmospheric rather than endogenously produced CH4 was the only substrate for CH4-oxidizing bacteria in this forest soil.

The inhibition of CH4 oxidation in surface soil was often attributed to high NH4+ concentrations (16, 26, 36). The primer set pmoA also amplifies the amoA gene of ammonium oxidizers coding for the α subunit of ammonium monooxygenase (22). In this forest soil population, MR1, closely related to Nitrosospira, was detected below the maximal CH4 consumption zone, while no ammonium oxidizers were detected near the surface. The presence of ammonium oxidizers below the soil layer of maximal CH4 oxidation activity raised the question whether ammonium oxidizers were sustained by nitrification. However, the NH4+ concentrations were not inhibitory to the methanotrophs. Recently, NH4+ was actually identified as a prerequisite for CH4 oxidation in rice field soil (8).

The increase of total extractable DNA indicated a stimulation and proliferation of all life from January (winter) to July (summer). However, while the total DNA concentration decreased with depth, the pmoA PCR product concentration and the number of methanotrophic populations (i.e., the number of DGGE bands) increased. The methanotrophic community expanded its presence from a well-defined subsoil layer in winter to the entire soil core in summer. It should be noted, however, that the presence of these populations does not necessarily mean that they were active. The MR2 band was present in all depth layers, indicating that MR2 was the most widely distributed methanotrophic population. In the soil layers with highest CH4 oxidation activity, populations MR2, MR3, and MR5 were prevalent over MR4, whereas MR4 and the putative ammonium oxidizer MR1 appeared in the soil layers below those with the maximal oxidation activity. This indicated that the methanotrophic populations were probably adapted to the conditions at a particular depth, each occupying its own ecological niche. The DGGE community pattern itself and the sequences detected were the same in winter and summer.

The most frequently detected bacteria of the forest soil bacterial community belong to the phyla Holophaga-Acidobacterium, high-GC gram-positive bacteria, and α proteobacteria. The α proteobacteria DGGE band appeared only in soil layers with CH4 consumption and was most closely related to clone sequences (ms10, ms8, and ms14) retrieved with primers specific for methanotrophs from a peat bog (McDonald and Murrell, personal communication). However, there is no direct evidence that any of the populations detected by 16S rDNA-based DGGE indeed belonged to the methanotrophs. These SSU rDNA sequences, as well as the pmoA sequences, were distantly related to type II methanotrophs. Recently, phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis and sequence comparison of pmoA in various soils also indicated novel methanotrophs distantly related to type II methanotrophs and α proteobacteria (23). Although, the correspondence between SSU rDNA and pmoA data might be coincidental, it allows the hypothesis that the α proteobacteria population detected with the universal primer set and the methanotrophic populations detected with the pmoA primer set are the same. The α proteobacteria population belonged to the most abundant bacteria in soil layers with CH4 oxidation. The novel sequences obtained by pmoA PCR and DGGE were found in the same soil layers. Finally, cloning results in other forest soils indicated that the same novel pmoA sequences were ubiquitously distributed in forest soils (23).

Process data and kinetic properties of CH4 consumption have repeatedly suggested that novel methanotrophs are responsible for atmospheric CH4 consumption (5, 6, 33). The novel pmoA sequences strongly support the existence of yet unknown methanotrophs involved in atmospheric CH4 consumption, as postulated by Bender and Conrad (6). Radioactive labeling studies showed that high-affinity methanotrophs in forest soils contain unusual i17:0, a17:0 and 17:1ω8c PLFAs whereas known methanotrophs contain 18:1ω8c and 16:1ω8c PLFAs (34).

Enrichments with high CH4 concentrations have resulted in the isolation of common methanotrophs from neutral environments. Molecular data from neutral soils and at high CH4 concentrations demonstrate the presence of common type I and II methanotrophs (19, 24, 32). A novel methanotrophic strain, S6, closely related to the genus Beijerinckia, was isolated from an acidic blanket peat, also by using high CH4 concentrations (12). It is unknown whether this strain, which contains only a soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO), is able to oxidize CH4 with high affinity (nanomolar Km). However, enrichments under low CH4 concentrations resulted in the isolation of the high-affinity type II methanotrophic strain LR1 from neutral soil (14).

In summary, all these observations suggest that known type I and II methanotrophs prevail in neutral environments, preferentially at high CH4 concentrations, but are able to adapt to high-affinity kinetics (type II methanotrophs). However, unknown high-affinity methanotrophs seem to prevail in acidic environments where atmospheric CH4 is oxidized. The missing link in the information is the isolation of a bacterium that combines all the molecular evidence, including unusual pmoA sequence and PLFA pattern, with high-affinity CH4 oxidation kinetics. Forest soils tend to be acidic, and the unknown, high-affinity methanotrophs seem to thrive at a low pH and might therefore have escaped isolation in neutral media (5, 11). This new knowledge about the wide distribution of novel acidicophilic methanotrophs in forest soil, together with the molecular tools at hand, should facilitate the enrichment and isolation of the bacterium which constitutes the missing link.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bianca Wagner, Sonja Fleissner, and Axel Fey for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant BIO-4-CT-960419 from the European Commission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamsen A P S, King G M. Methane consumption in temperate and subarctic forest soils—rates, vertical zonation, and responses to water and nitrogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:485–490. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.2.485-490.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaral J A, Knowles R. Inhibition of methane consumption in forest soils and pure cultures of methanotrophs by aqueous forest soil extracts. Soil Biol Biochem. 1997;29:1713–1720. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaral J A, Knowles R. Inhibition of methane consumption in forest soils by monoterpenes. J Chem Ecol. 1998;24:723–734. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral J A, Ekins A, Richards S R, Knowles R. Effect of selected monoterpenes on methane oxidation, denitrification, and aerobic metabolism by bacteria in pure culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:520–525. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.520-525.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amaral J A, Ren T, Knowles R. Atmospheric methane consumption by forest soils and extracted bacteria at different pH values. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2397–2402. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2397-2402.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bender M, Conrad R. Kinetics of CH4 oxidation in oxic soils exposed to ambient air or high CH4 mixing ratios. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1992;101:261–270. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benstead J, King G M. Response of methanotrophic activity in forest soil to methane availability. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodelier P L E, Roslev P, Henckel T, Frenzel P. Stimulation of methane oxidation by ammonium-based fertilizers around rice roots. Nature. 2000;403:421–424. doi: 10.1038/35000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicerone R J, Oremland R S. Biogeochemical aspects of atmospheric methane. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1988;2:299–327. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crutzen P J. Methane's sinks and sources. Nature. 1991;350:380–381. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedysh S N, Panikov N S, Tiedje J M. Acidophilic methanotrophic communities from sphagnum peat bogs. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:922–929. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.922-929.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedysh S N, Panikov N S, Liesack W, Grosskopf R, Zhou J Z, Tiedje J M. Isolation of acidophilic methane-oxidizing bacteria from northern peat wetlands. Science. 1998;282:281–284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunfield P, Knowles R. Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3129–3135. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3129-3135.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunfield P F, Liesack W, Henckel T, Knowles R, Conrad R. High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1009–1014. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1009-1014.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package. Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulledge J, Schimel J P. Low-concentration kinetics of atmospheric CH4 oxidation in soil and mechanism of NH4+ inhibition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4291–4298. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4291-4298.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulledge J, Steudler P A, Schimel J P. Effect of CH4-starvation on atmospheric CH4 oxidizers in taiga and temperate forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 1998;30:1463–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanson R S, Hanson T E. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:439. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.439-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henckel T, Friedrich M, Conrad R. Molecular analyses of the methane-oxidizing microbial community in rice field soil by targeting the genes of the 16S rRNA, particulate methane monooxygenase, and methanol dehydrogenase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1980–1990. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1980-1990.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyer J. Der Kreislauf des Methans. Mikrobiologie, Ökologie, Nutzung. Berlin, Germany: Akademie-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holben W E, Jansson J K, Chelm B K, Tiedje J M. DNA probe method for the detection of specific microorganisms in the soil bacterial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:703–711. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.703-711.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes A J, Costello A, Lidstrom M E, Murrell J C. Evidence that particulate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionarily related. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(95)00311-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes A J, Roslev P, McDonald I R, Iversen N, Henriksen K, Murrell J C. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3312–3318. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3312-3318.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen S, Oevreas L, Daae F L, Torsvik V. Diversity in methane enrichments from agricultural soil revealed by DGGE separation of PCR amplified 16S rDNA fragments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;26:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 26.King G M, Schnell S. Ammonium and nitrite inhibition of methane oxidation by Methylobacter albus BG8 and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b at low methane concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3508–3513. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3508-3513.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King S L, Quay P D, Landsdown J M. The 12C/13C kinetic isotope effect for soil oxidation of methane at ambient atmospheric concentrations. J Geophys Res. 1989;94:18273–18277. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klemedtsson A K, Klemedtsson L. Methane uptake in swedish forest soil in relation to liming and extra N-deposition. Biol Fertil Soils. 1997;25:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koschorreck M, Conrad R. Oxidation of atmospheric methane in soil: measurements in the field, in soil cores and in soil samples. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1993;7:109–121. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Klugbauer S, Klugbauer N, Weizenegger M, Neumaier J, Bachleitner M, Schleifer K H. Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:554–568. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moré M I, Herrick J B, Silva M C, Ghiorse W C, Madsen E L. Quantitative cell lysis of indigenous microorganisms and rapid extraction of microbial DNA from sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1572–1580. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1572-1580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oevreas L, Jensen S, Daae F L, Torsvik V. Microbial community changes in a perturbed agricultural soil investigated by molecular and physiological approaches. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2739–2742. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2739-2742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roslev P, Iversen N, Henriksen K. Oxidation and assimilation of atmospheric methane by soil methane oxidizers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:874–880. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.874-880.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roslev P, Iversen N. Radioactive fingerprinting of microorganisms that oxidize atmospheric methane in different soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4064–4070. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.4064-4070.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlichting E, Blume H P. Bodenkundliches Praktikum. Hamburg, Germany: Verlag Paul Parey; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnell S, King G M. Mechanistic analysis of ammonium inhibition of atmospheric methane consumption in forest soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3514–3521. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3514-3521.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnell S, King G M. Stability of methane oxidation capacity to variations in methane and nutrient concentrations. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;17:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whalen S C, Reeburgh W S, Barber V A. Oxidation of methane in boreal forest soils—a comparison of 7 measures. Biogeochemistry. 1992;16:181–211. [Google Scholar]