Abstract

Background

Clinical data informing antimicrobial susceptibility breakpoints for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections are lacking. We sought to leverage real-world data to identify MIC values within the currently defined susceptible range that could discriminate mortality risk for patients with S. maltophilia infections and guide future breakpoint revisions.

Methods

Inpatients with S. maltophilia infection who received single-agent targeted therapy with levofloxacin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole were identified in the Cerner HealthFacts electronic health record database. Encounters were restricted to those with MIC values reported to be in the susceptible range for both agents. Curation for exact (non-range) MIC values yielded sequentially granular model populations. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted OR (aOR) of mortality or hospice discharge associated with different susceptible-range MICs, controlling for patient- and centre-related factors, and infection site, polymicrobial infection and receipt of empirical therapy.

Results

Seventy-three of 851 levofloxacin-treated patients had levofloxacin MIC of exactly 2 mg/L (current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) susceptibility breakpoint) and served as the reference category for levofloxacin breakpoint models. In breakpoint model I (n = 501), aOR of mortality associated with infection due to isolates with levofloxacin MIC of ≤1 versus 2 mg/L were similar [aOR = 1.79 (95% CI 0.88–3.62), P = 0.11]. In breakpoint model IIa (n = 358), aOR of mortality associated with MIC ≤0.5 versus 2 mg/L were also similar [aOR 0.1.36 (95% CI 0.65–2.83), P = 0.41]. However, breakpoint model IIb (n = 297) displayed higher aOR of mortality associated with an MIC of 1 versus 2 mg/L [aOR 2.36 (95% CI 1.14–4.88), P = 0.02]. Only 9/645 trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-treated patients had trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole MIC of exactly 2/38 mg/L precluding informative models for this agent.

Conclusions

In this retrospective study of real-world patients with S. maltophilia infection, risk-adjusted survival data do not appear to stratify patients clinically within current susceptible-range MIC breakpoint for levofloxacin (≤2 mg/L) by mortality.

Introduction

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is a Gram-negative pathogen with a propensity to cause serious healthcare-associated infections,1 especially among critically ill and immunocompromised patients. These infections carry a substantial mortality risk, with crude mortality ranging between 14% and 69% for bacteraemia and 23% and 77% for pneumonia.2–4 Treatment of S. maltophilia infections poses a challenge in light of intrinsic resistance to many classes of antibiotics, including carbapenems and aminoglycosides,5–7 and an absence of comparative clinical trial data.8 Furthermore, the heavy reliance on in vitro data to gauge superiority of available antibiotic options has been questioned in light of suboptimal reliability of automated susceptibility techniques for S. maltophilia and no data demonstrating a correlation between in vitro susceptibility breakpoints and clinical outcomes in patients with S. maltophilia infections.9

Expert guidance from IDSA recommends trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as first-line therapy for moderate to severe S. maltophilia infections based on treatment experience and in vitro activity retained against >90% isolates.1,10 The guidance also recommends against use of levofloxacin as a single agent to treat moderate to severe S. maltophilia infections considering the risk of de novo resistance on therapy.10 However, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole use is often precluded by its tendency to cause myelosuppression, direct toxicities and allergies and, as a result, levofloxacin remains the most commonly used antibiotic to treat S. maltophilia infections.8,11 Furthermore, a recent relatively large observational study with overlap weighting design (published after IDSA guidance was released) found trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin to display comparable effectiveness in patients with S. maltophilia blood and lower respiratory infections, substantiating findings from a meta-analysis of prior smaller studies.11,12 Understanding whether in vitro susceptibility-derived breakpoints for these antibiotics also discriminate S. maltophilia clinical isolates on mortality risk might enable reappraisal of existing susceptibility breakpoints by standards development organizations and regulatory agencies and optimize antibiotic choices, and in turn, patient survival.

A large electronic health record (EHR) database was leveraged to retrospectively determine whether susceptible-range in vitro Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints for S. maltophilia against levofloxacin correlated with mortality risk.

Methods

Case selection

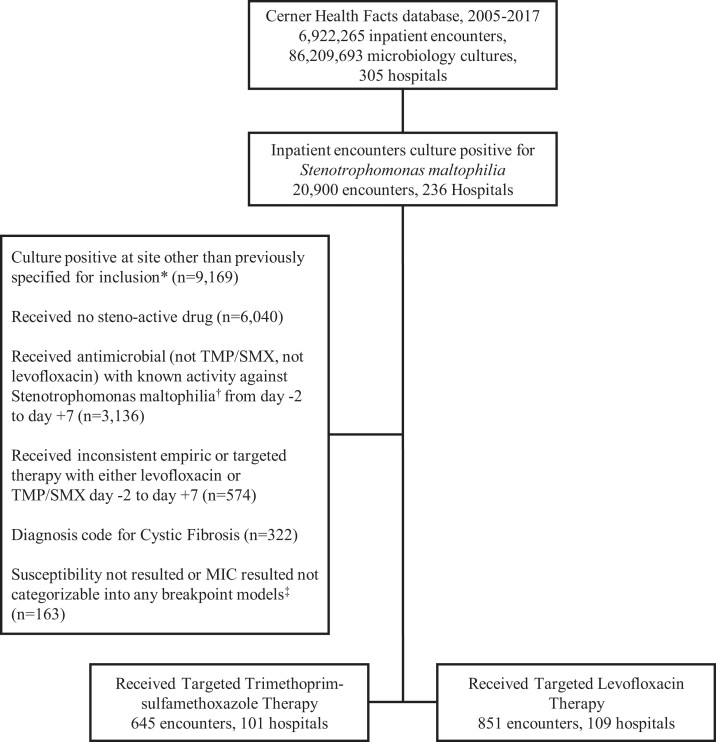

The Cerner HealthFactsTM database was queried for all inpatient admissions between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2017 that recorded ≥1 blood and/or lower respiratory culture displaying growth of S. maltophilia. This database includes de-identified EHR and administrative data on inpatient encounters including demographics, comorbidity and severity-of-illness indicators, and outcomes of hospitalized patients as well as pharmacy, microbiology and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) data. Further details on the clinical and microbiological data have been reported previously.13,14 Only the initial infection episode per encounter and initial encounter per patient was included for analysis. Lower respiratory cultures included sputum, tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage and protected bronchial brush washings. An infection episode was defined based on clinicians’ intention to treat and presumed when an inpatient with S. maltophilia in clinical cultures received S. maltophilia-active targeted therapy, which was defined as any trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or levofloxacin or ceftazidime or minocycline received within +2 to +7 days after index culture was drawn. However, low sample sizes of the ceftazidime (n = 34) and minocycline (n = 13) groups precluded independent analysis of MIC-related outcome associations for these antibiotics. Patients were excluded if they received any other antimicrobial with known in vitro activity against S. maltophilia. Antimicrobials that fit this exclusion criteria were erythromycin, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, tigecycline, doxycycline, eravacycline, cefepime, ticarcillin/clavulanate, cefiderocol, colistin and chloramphenicol. Patients who received more than one therapy of interest (either concomitantly or inconsistently as empirical versus targeted therapy) were excluded to enable isolation of observed MIC–outcome relationship to the agent of interest. Patients with cystic fibrosis and those for whom susceptibility data were unavailable were also excluded. Patient selection is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Case Selection Flow Chart. Depiction of cases selected, with cases that met exclusion criteria filtered out. *Included clinical sites: blood culture, bronchoalveolar lavage, protected bronchial brush washing, sputum culture and tracheal aspirate. †Antimicrobials with activity against Stenotrophomonas 2 days prior to and 7 days after culture positivity were excluded. Known Stenotrophomonas-active agents that were excluded are: erythromycin, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, minocycline, tigecycline, doxycycline, eravacycline, ceftazidime, cefepime, ticarcillin-clavulanate, cefiderocol, colistin, and chloramphenicol. ‡TMP/SMX Breakpoint Model I: MIC ≤2, ≥4, Breakpoint Model IIa: MIC ≤1, 2, Breakpoint Model IIb: ≤0.5, 1, 2; Levofloxacin Breakpoint Model I: ≤2, 4, ≥8, Breakpoint Model IIa: ≤1, 2, Breakpoint Model IIb: <0.5, 1, 2.

MIC values

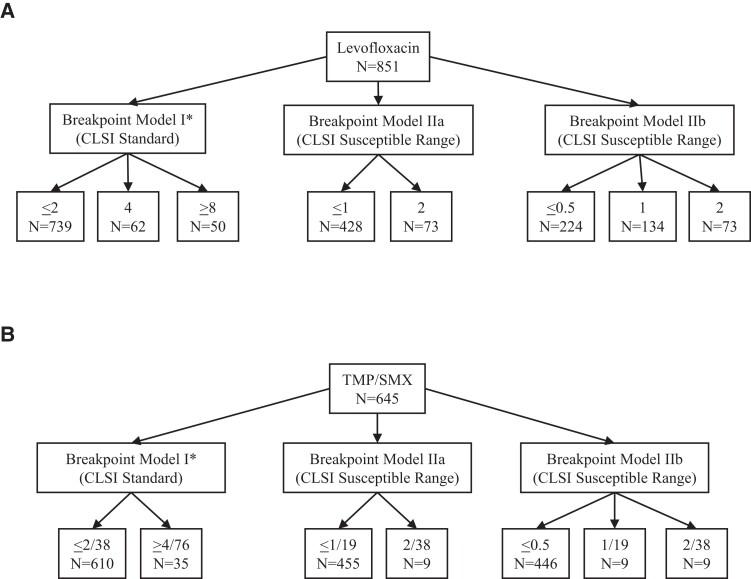

Two principles of real-world management of S. maltophilia informed the study design. First, patients with S. maltophilia infections often do not receive levofloxacin (and more so, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) as initial empirical therapy, especially prior to species reporting. Secondly, it wouldn't be considered standard of care to initiate trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin or continue these agents once the S. maltophilia isolate is reported as resistant. This limited the analysis to associating MIC and outcome within the CLSI-recommended susceptible range for patients who received either trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or levofloxacin as targeted therapy, or received either agent empirically and continued on the same agent as targeted therapy. Due to variability of reporting, numerical susceptibility results were manually reviewed by a medical microbiologist (A.L.) and curated to exclude implausible values. If the MIC value could not be categorized into one of the predefined breakpoint models (Figure 2), then it was excluded from analysis for the respective model (for example, an MIC of ≤2 mg/L could not be binned into ≤1 mg/L or 2 mg/L categories, thus was excluded).

Figure 2.

Pictorial Depiction of Breakpoint Models in TMP/SMX and Levofloxacin Cohorts. Across models, total number of patients varied by ability to be categorized within the model. *Breakpoint model 1 for Levofloxacin is the CLSI standard for breakpoints: susceptible (MIC </=2), intermediate (MIC=4), resistant (MIC >/=8); Breakpoint model 1 for TMP/SMX is the CLSI standard for breakpoints: susceptible (MIC </=2) and resistant (MIC >/=4).

Statistical analysis

Cohorts with increasingly granular MIC reporting within the susceptible range were established, enabling sequential modelling of different MIC pairs to identify a mortality breakpoint. The primary outcome was aOR and 95% CI of in-hospital mortality (including discharge to hospice). Multivariate logistic regression was used to control for clinically relevant confounders including age, sex, immunocompromised status, baseline SOFA score (on Day 0, where Day 0 was the day of index culture sampling), Elixhauser comorbidity index, infection site, polymicrobial infection, ICU stay (Day −1 to Day +2), mechanical ventilation (Day −1 to Day +2), vasopressor use (Day −1 to Day +2), empirical therapy (defined as receipt of the same agent anytime between Day −2 and Day +1), year range, as well as hospital-level factors including academic status, urban/rural qualification, geographical region and bed capacity. Adjustment to account for within-hospital clustering was done using generalized estimating equations. Sensitivity analyses were performed (i) on the cohort limited to non-bacteraemic patients with lower respiratory infections (small sample size precluded analysis of the bacteraemic-only patient cohort); and (ii) for targeted therapy, definition adjusted for possible variability in timing of available susceptibility results relative to culture sampling: Day +1 through to Day +7 (empirical window Day −2 through to Day 0). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Unique inpatient encounters (n=20 900) with any culture positive for S. maltophilia were identified in 236 hospitals in the USA from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2017. After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (Figure 1), there were 1496 unique inpatient encounters identified at 210 hospitals included in the study population (Figure 1). The crude mortality of the total treated study population (n = 1496) was 19.9%. For patients with S. maltophilia in clinical cultures without evidence of S. maltophilia-directed therapy (presumably enriched for colonization; n = 6040), crude mortality was 15.9%. Of the 1496 patients, 851 patients at 109 hospitals received levofloxacin and 645 patients at 101 hospitals received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Days of consecutive therapy are reported in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). Baseline characteristics for patients by treatment received is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin study cohorts

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Levofloxacin | |

|---|---|---|

| N=645 | N=851 | |

| Patient-level factors | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 60.0 [40.0–71.0] | 64.0 [50.0–74.0] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 39 (5.4) | 42 (4.9) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 132 (20.5) | 139 (16.3) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 75 (11.6) | 64 (7.5) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 403 (62.5) | 606 (71.2) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 287 (44.5) | 380 (44.7) |

| Male | 358 (55.5) | 471 (55.3) |

| Immunocompromised | 13 (2.0) | 14 (1.6) |

| Elixhauser score, median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| SOFA score group | ||

| <2 | 500 (77.5) | 607 (71.3) |

| ≥2 | 145 (22.5) | 244 (28.7) |

| Encounter-level factors | ||

| Infection site | ||

| Blood | 61 (9.5) | 107 (12.6) |

| Respiratory | 584 (90.5) | 744 (87.4) |

| Polymicrobial infection | 312 (48.4) | 388 (45.6) |

| Therapy received for polymicrobial infection | 248 (38.4) | 284 (33.4) |

| Empirical therapy received | 93 (14.4) | 406 (47.7) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 20.0 (11.0–39.0) | 14.0 (7.0–31.0) |

| Admission to ICU | 76 (11.5) | 134 (15.7) |

| Vasopressors administered | 11 (1.7) | 21 (2.5) |

| Mechanical ventilation received | 18 (2.8) | 19 (2.2) |

| Deceased/discharge to hospice | 123 (19.1) | 179 (21.0) |

| Hospital-level factors | ||

| Census region | ||

| Midwest | 151 (23.4) | 169 (19.9) |

| Northeast | 129 (20.0) | 161 (18.9) |

| South | 226 (35.0) | 362 (42.5) |

| West | 139 (21.6) | 159 (18.7) |

| Hospital size (beds) | ||

| <5 | 47 (7.3) | 15 (1.8) |

| 5–99 | 16 (2.5) | 67 (7.9) |

| 100–199 | 68 (10.5) | 143 (16.8) |

| 200–299 | 117 (18.1) | 173 (20.3) |

| 300–499 | 235 (36.4) | 275 (32.3) |

| 500+ | 162 (25.1) | 178 (20.9) |

| Teaching facility | 422 (70.3) | 534 (65.2) |

| Urban facility | 503 (78.0) | 742 (87.2) |

Unless otherwise stated, values are depicted as numbers (n), followed by percentage per total number of included patients for each cohort.

Levofloxacin

There were 851 unique inpatients with S. maltophilia infections at 109 hospitals who received levofloxacin as treatment. Baseline characteristics of those in the levofloxacin cohort are depicted in Table 1. Of the patients with S. maltophilia infection who received levofloxacin, 21% (179/851) died (Table S2). Seven hundred and thirty-nine of 851 patients (86.8%) had S. maltophilia isolates in the susceptible MIC range ≤2 mg/L. The interval hospitalization duration between culture drawn and death for those in the MIC ≤ 2 mg/L cohort was 10 days (median, IQR 5–17.5) (Table S3). In breakpoint model IIa, the cohort was further subdivided with values categorized into ≤1 mg/L (n = 428) and 2 mg/L (n = 73), leaving 501 patients for analysis (Figure 2). In breakpoint model IIa, crude mortality was 21.5% (108 of 501 patients died). In breakpoint model IIb, the susceptible range was further categorized as ≤0.5 mg/L (n = 224), 1 mg/L (n = 134) and 2 mg/L (n = 73) (Figure 2); 431 encounters were usable for analysis for this breakpoint model. In breakpoint model IIb, 21.1% (91/431) patients died. This group was modelled sequentially as pairwise comparisons of MIC ≤0.5 (versus 2) mg/L and 1 (versus 2) mg/L as well as a third comparison, in which ≤0.5 was compared with the combination of MIC = 1 and MIC = 2 mg/L.

In breakpoint model IIa, patients who had an MIC of ≤1 mg/L (versus exactly 2 mg/L) displayed an aOR of mortality of 1.79 (95% CI 0.88–3.62, P = 0.11). In breakpoint model IIb, comparison of patients with an MIC of 0.5 versus 2 mg/L resulted in an aOR of 1.36 (95% CI 0.65–2.83, P = 0.41). Comparison of an MIC of exactly 1 mg/L versus exactly 2 mg/L resulted in an aOR of 2.36 (95% CI 1.14–4.88, P = 0.02). A comparison of patients with an MIC of 0.5 mg/L versus MIC of 1 and 2 mg/L resulted in an aOR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.45–1.25, P = 0.26). Results were similar in the sensitivity analyses where targeted therapy was defined as Day +1 to Day +7 (Day 0 = culture sampling) and within the subset of respiratory tract infections only (Tables S4 and S5). Adjusted mortality by MIC (<0.5, 1, 2) did not appear to bear a linear relationship (Table S6).

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

There were 645 unique inpatients with S. malotphilia infections at 101 hospitals who received trimethroprim/sulfamethoxazole as treatment. Baseline characteristics of those in the trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole cohort are depicted in Table 1. Of the patients with S. maltophilia infection who received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 19% (123/645) died (Table S2). Baseline characteristics of those in the trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole cohort are depicted in Table 1. Of these, 610 (94.6%) patients had S. maltophilia isolates in the CLSI susceptible range of ≤2 mg/L. However, only nine trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-treated patients had isolates with an exact MIC of 2 mg/L and another nine had isolates with an exact MIC of 1 mg/L once further MIC strata were created for breakpoint models (Figure 2). Having exact MIC values at the existing susceptibility breakpoint was crucial to avoid inclusion of patients with isolates interpreted as resistant. Hence, sample size limitations at these MICs precluded downstream modelling to identify a mortality breakpoint for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole against S. maltophilia.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of 1496 patients with S maltophilia bloodstream and lower respiratory tract infections at 210 hospitals in the USA from 2005 to 2017, we found that MICs within the CLSI-suggested susceptible range for levofloxacin did not appear to discriminate patients by risk-adjusted mortality. In multiple models with increasingly granular MIC data, lower MICs were not associated with improved risk-adjusted mortality. In fact, comparing exact MICs yielded a higher mortality risk associated with 1 versus 2 mg/L.

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and levofloxacin are two of the most commonly used antibiotics to treat patients with S. maltophilia infections. However, the US FDA currently does not recognize CLSI breakpoints for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or levofloxacin against S. maltophilia given the lack of data correlating these in vitro breakpoints to patient outcomes.15 EUCAST only recognizes trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole breakpoints and cites a similar explanation of a lack of data to support the relationship between susceptibility testing and clinical outcomes for other agents, including levofloxacin.16

Our study of clinical patient outcomes revealed a lack of correlation between mortality outcomes and levofloxacin breakpoints. These findings were after adjusting for baseline illness severity, receipt of S. maltophilia-active empirical therapy and other key confounders. Our primary and sensitivity analyses both do not indicate any associated survival advantage in levofloxacin-treated patients if their S. maltophilia isolate MICs were below or at the current CLSI breakpoint of 2 mg/L. Additionally, a linear relationship was not observed in adjusted mortality across the three MIC strata (≤0.5, 1, 2 mg/L) within the susceptible range. The results of our study are in contrast to a recent study by Fratoni et al.,17 in which levofloxacin free-AUC/MIC data using a neutropenic thigh model of infection demonstrated that levofloxacin at a human simulated dose of 750 mg every 24 h resulted in consistent in vivo activity against S. maltophilia isolates at an MIC of ≤1, but not at an MIC of 2 mg/L. It must be recognized, however, that the correlation of neutropenic thigh models of infection to clinical encounters with S. maltophilia infections at various sites may be limited. Patients with S. maltophilia infection receive antibiotic courses spanning several days, which vary depending on the site. Consequently, while the in vivo model may suggest improved outcomes at a 24 h endpoint for isolates with an MIC ≤1 mg/L, how colony counts at 24 h correlate with clinical success in human patients after a longer treatment course for infections at various sites with different drug distributions and kinetics is unknown. Furthermore, while reliance on a neutropenic model is important for pharmacodynamic evaluation of drugs, the patients included in our study were not enriched for neutropenia, which could further explain the discordance between our study and the results of Fratoni et al.

Our study has significant strengths. This is the largest study to date to analyse the relationship between MIC and clinical outcomes for S. maltophilia infections. The availability of large EHR databases has enabled retrospective analyses linking microbiological, pharmacological and clinical outcome data to test the association between MICs and clinical outcomes and appraise the heavy reliance on in vitro data for treatment decisions. The methodology used in this study allowed examination of various breakpoints and enabled risk adjustment using clinically relevant variables to control for confounders. Delays in updating and approving breakpoints impacts AST device manufacturers in the USA who need to conform to FDA-approved breakpoints.18

Nonetheless, our findings must be interpreted with caution and require considering several limitations and unmeasured confounders. The dose of antibiotic was not reported and effect modification of the MIC outcome relationship by dosage could not be tested. Most cases were respiratory tract infections; counts for bloodstream infection were low, precluding a separate analysis of this important subset. S. maltophilia is a known colonizer of the respiratory tract. However, even at the bedside, the distinction of infection versus respiratory colonization often remains nebulous. By only including patients with S. maltophilia clinical isolates who received targeted therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or levofloxacin, we aimed to leverage the intention-to-treat principle, enriching for cases deemed to represent true infections by the treating clinicians, which we hope strengthens our associating outcomes to the organism. Nonetheless, there may still have been ascertainment bias, skewing results towards the null. Our study design excluded patients who received combination therapy; although in vitro studies suggest synergy of select agents against these bacteria, there are insufficient clinical data to date to confirm that this approach is favourable over monotherapy.19 Our study cohort was relatively underweighted in illness severity and comorbidity burden, likely due to our need to apply many exclusion criteria, which may have also biased results towards the null.

We leveraged the practical approach of searching the EHR database for MIC; however, the methodology of MIC reporting (e.g. antimicrobial susceptibility assays, broth microdilution, ETEST) could not be adequately discerned. Recent reports of discordance between commercial antimicrobial susceptibility assays and broth microdilution results have implications for our findings. A recent paper by Khan et al.9 compared commercial automated AST systems with broth microdilution. Specifically, the authors looked at VITEK 2 (bioMérieux, Durham NC, USA), Phoenix 100 (BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD, USA) and MicroScan WalkAway (Beckman Coulter, Sacramento, CA, USA). For trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, VITEK 2 had a categorical agreement (CA) of 77.1% (MicroScan and Phoenix both had a CA of 98.1%). For levofloxacin, all three platforms had CA ranging from 79% to 85%. The rate of very major errors was 0% for levofloxacin for the VITEK 2 and Phoenix platforms, but as high as 9.1% for the MicroScan. The rate of minor errors across all systems was more than the CLSI-recommended acceptable level of >10% (12% for VITEK 2, 14.8% for MicroScan and 17.8% for Phoenix). Depending on the platform used at the hospitals included in our study, many isolates that would be categorized as resistant by broth microdilution may have been included as susceptible in this study. Since most clinical laboratories in the USA rely on commercial automated systems for testing, our study results may have been influenced by errors in automated AST modalities.

Conclusions

In our study using real-world data from 1496 hospitalized patients with S. maltophilia infections, risk-adjusted mortality outcomes do not appear to correlate with levofloxacin MICs within the current CLSI-designated susceptible range. Whether our findings reflect an actual lack of correlation between susceptible-range MIC and outcome or errors in MICs reported for S. maltophilia using automated AST modalities or a combination of these and other factors remains unclear and warrants further clinical investigations. However, given the conspicuous scarcity of clinical data to inform breakpoints for S. maltophilia thus far, our study offers novel insights. Re-appraisal, standardization and optimization of S. maltophilia AST is warranted. We encourage more clinical studies that could test the validity of our findings and address the evidentiary gap between MIC and patient, ultimately bridging the gap between industry, standards development organizations, laboratories and regulatory agencies. Meanwhile, it might be prudent for clinicians to not rely solely on MIC and incorporate numerous other factors when selecting antimicrobial regimens in the treatment of S. maltophilia infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David Fram and Huai Chun (Commonwealth Informatics Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) for their assistance with data curation, and Drs Sumathi Nambiar, John Farley and Thushi Amini (Office of Antimicrobial Products, FDA/CDER) for their feedback on the study design and regulatory input. We also thank Ms. Kelly Byrne (Critical Care Medicine Department, NIH Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA) for assistance with formatting the manuscript.

NIH–ARORI group members

Only a portion of members from the ARORI group participated in this study, thus those that were not involved were not part of the co-authors list and are not acknowledged here.

Contributor Information

Sadia H Sarzynski, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Alexander Lawandi, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Sarah Warner, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Cumhur Y Demirkale, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jeffrey R Strich, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

John P Dekker, Bacterial Pathogenesis and Antimicrobial Resistance Unit, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Ahmed Babiker, Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Willy Li, Pharmacy Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Sameer S Kadri, Critical Care Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive B10, 2C145, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Funding

The study was funded in part by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Transparency declarations

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent any position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the US Department of Health and Human Services, or the US government.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 to S6 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Gales AC, Seifert H, Gur Det al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia clinical isolates: results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2016). Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6: S34–46. 10.1093/ofid/ofy293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Falagas ME, Kastoris AC, Vouloumanou EKet al. Attributable mortality of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections: a systematic review of the literature. Future Microbiol 2009; 4: 1103–9. 10.2217/fmb.09.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Senol E, DesJardin J, Stark PCet al. Attributable mortality of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 1653–6. 10.1086/340707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Looney WJ, Narita M, Muhlemann K. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging opportunist human pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis 2009; 9: 312–23. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70083-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooke JS. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25: 2–41. 10.1128/CMR.00019-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kadri SS, Adjemian J, Lai YLet al. Difficult-to-treat resistance in Gram-negative bacteremia at 173 US hospitals: retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and outcome of resistance to all first-line agents. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 1803–14. 10.1093/cid/ciy378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanchez MB. Antibiotic resistance in the opportunistic pathogen Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Front Microbiol 2015; 6: 658. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang YL, Scipione MR, Dubrovskaya Yet al. Monotherapy with fluoroquinolone or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 176–82. 10.1128/AAC.01324-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan A, Arias CA, Abbott Aet al. Evaluation of the Vitek 2, Phoenix and MicroScan for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59: e0065421. 10.1128/JCM.00654-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RAet al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of AmpC β-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 72: 1109–16. 10.1093/cid/ciab295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarzynski SH, Warner S, Sun Jet al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus levofloxacin for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections: a retrospective comparative effectiveness study of electronic health records from 154 US hospitals. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9: ofab644. 10.1093/ofid/ofab644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ko JH, Kang CI, Cornejo-Juarez Pet al. Fluoroquinolones versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019; 25: 546–54. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strich JR, Warner S, Lai YLet al. Needs assessment for novel Gram-negative antibiotics in US hospitals: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 1172–81. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kadri SS, Lai YL, Warner Set al. Inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy for bloodstream infections based on discordant in-vitro susceptibilities: a retrospective cohort analysis of prevalence, predictors, and mortality risk in US hospitals. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21: 241–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30477-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. FDA . FDA-Recognized Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Interpretive Criteria. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/fda-recognized-antimicrobial-susceptibility-test-interpretive-criteria.

- 16. EUCAST . Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Guidance Document. 2012. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/General_documents/S_maltophilia_EUCAST_guidance_note_20120201.pdf.

- 17. Fratoni AJ, Nicolau DP, Kuti JL. Levofloxacin pharmacodynamics against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in a neutropenic murine thigh infection model: implications for susceptibility breakpoint revision. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 77: 164–8. 10.1093/jac/dkab344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prinzi A. Updating Breakpoints in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2022. https://asm.org/Articles/2022/February/Updating-Breakpoints-in-Antimicrobial-Susceptibili.

- 19. Kmeid JG, Youssef MM, Kanafani ZAet al. Combination therapy for Gram-negative bacteria: what is the evidence? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2013; 11: 1355–62. 10.1586/14787210.2013.846215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.