Abstract

This research aims to explore how China’s banking industry is influenced by phishing. We used a statistical analysis method and the Structural Equation Model (SEM). The results show that the degree of public security force involvement, the function of telecom operators, the implementation of relative legislation initiatives, and the issues of cooperative governance are vital to limit the occurrence rate of phishing and related cybercrimes, which challenge the development of China’s banking industry. This research will hopefully guide Chinese policy makers to create and implement more progressive initiatives for preventing phishing and facilitate the development of China’s banking industry.

Keywords: Phishing, China’s banking industry, Public security force, Telecom operators, Legislation initiatives, Cooperative governance

Introduction

Since the early 1980s, science and technology have rapidly progressed (Chen et al., 2018). The emergence of the Internet facilitated the integration between traditional industries and online business, which profoundly changed people’s lifestyles and commercial modes (Aseef et al., 2005; Bamrara et al., 2012; Broadhurst et al., 2014; Cohen & Felson, 1979; Irshad, 2016). The Internet provides considerable convenience in terms of rapid and boundless communication but also creates risks of fraud, as cashless transactions are completed via third-party payment platforms (such as through banks). As a consequence, people are experiencing a new form of cybercrime, which is commonly called “phishing” (Rastenis et al., 2020). With the advancement of Internet technology, the techniques of phishing are becoming increasingly sophisticated and widespread.

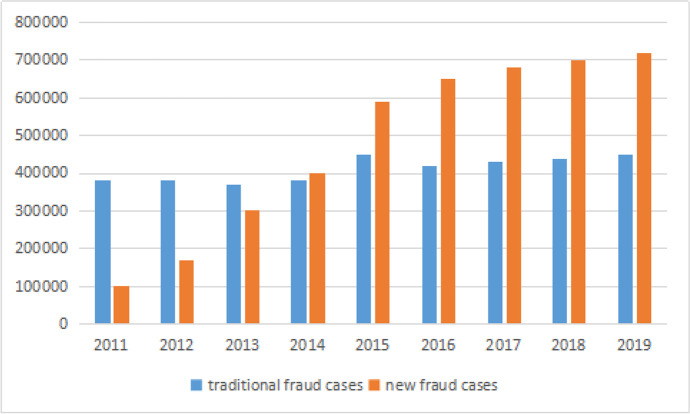

China has 829 million Internet users and the largest population in the world. Phishing, which are considered to be one of the “three black industries in China”, are already the main force of a new generation of cybercrimes (Ikechi & Okay, 2013). In 2014, over 500,000 cases of phishing were reported by both victims and banks, which resulted in an asset loss of 10.7 billion RMB (Wang et al., 2018). This increased to 590,000 cases in 2015, resulting in an asset loss of 22.3 billion RMB (Ma, 2019). According to the 43rd Statistical Report on the Status of Development of China’s Internet released by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), in 2018, 27.3% of the Chinese online users encountered information disclosure. Moreover, 28.1% of them suffered phishing (Zhou et al., 2019). Additionally, phishing was growing extremely faster than other crimes in the recent decade (See Fig. 1), when the number of traditional fraud cases showed a slight increase (Zou & Lv, 2019).

Fig. 1.

Trend and Comparison of Case Numbers of Traditional Fraud and Phishing

According to relevant statistical data in 2019, victims suffered economic losses of 380 million RMB due to phishing fraud, with an average loss of about 24,549 RMB per person, which is slightly higher than the amount recorded in 2018, showing a new peak in the past 6 years (Ma, 2019). Due to this large economic loss, it is impossible to solve this problem fundamentally if the money cannot be recovered effectively. There is also a hidden danger to potentially trigger or intensify social conflict. Phishing has directly caused huge economic losses. Among the cases recorded by the Ministry of Public Security in 2013, 2014, and 2016, there were 2085 cases involving more than 1 million RMB and 94 cases involving more than 10 million RMB, not including cases that were not reported as fraud (Lin et al., 2017). Moreover, the economic loss per capita of phishing fraud is increasing every year. Phishing has a significant impact on China’s society, considering the many cases of fraud that have caused tremendous harm to individuals and their families. Phishing has also greatly disrupted China’s social and economic order and jeopardized public safety (Wu et al., 2019). To sum up, attempting to contain the high incidence of phishing has tested the abilities of the police to govern the Internet and the telecommunication and banking industries to reduce the occurrence rate of phishing in China.

The aim of this study is to conduct an in-depth analysis of the factors that limit the incidence of phishing, which seems to be an obstacle to the future development of China’s banking industry. The next section provides a literature review of the relevant research by outlining the previous phishing studies on involving the public security force, telecom operators, legislation initiatives, and cooperative governance. The third section outlines the methodology of this paper. Two methods were used in this paper: statistical analysis and Structural Equation Model (SEM). The statistical analysis was employed to garner feedback from a survey called “An Assessment on the Roles of Phishing in challenging the development of the Chinese Banking Industry”. The SEM aims to assess to what degree the public security force, telecom operators, legislation initiatives, and issues of cooperative governance influence or limit the incidence of phishing. The subsequent section provides a discussion, and the conclusion comprises the final part of this paper.

Literature Review

The Internet has prevailed in all aspects of human life, including entertainment, education, and commercial behaviors. However, people who enjoy the benefits and convenience of the internet must face the increasing risks of losing their private information and suffering from cybercrime. Presently, cybercrime is usually associated with phishing or phishing (Clough, 2010). Phishing refers to the illegal acts of criminals who create fake information and develop scams via telephone calls, mobile text messages, and the Internet to cheat victims and compel them to make payments or transfer money from a bank using contactless methods (Bamrara et al., 2012). It is an ongoing problem and tends to be frequently conducted by overseas criminals with only a small amount of money involved each time (Zakaria, 2013). Moreover, through the use of electronic communication equipment, phishing usually targets specific groups based on class and age, including social elites, intellectuals, and ordinary people, all of whom can be victims. Therefore, phishing affects all sectors of society and has obvious and significant impacts. In the late 1970s, developed countries began studying cybercrime and phishing. The traditional social order changes slowly, which provides an opportunity for phishing to emerge, while Internet technology develops rapidly (Cohen & Felson, 1979). Moreover, phishing is becoming the leading approach used for cybercrime and has threatened the performance and future development of the banking industry in China since the start of the new millennium (Zhao & Ge, 2013). At present, typical cases of phishing in China mainly include the false trading of game equipment, bogus online investments, pretending to be American soldiers, pretending to be acquaintances on Tencent QQ, online investments and finance, voice phishing related to border area affairs, the trade of false papers online, cross-border phone fraud, and online scalping. Considering these cases, it is important to identify and understand the presence of factors that can limit the incidence of phishing in China.

In addition, China has placed considerable emphasis on research into phishing since the start of the new millennium. Most of these studies have been focused on the aspect of phishing and its negative impacts on society, especially the property losses of victims (Liu & Sun, 2001). Most phishing victims are university students in China. They are usually deceived by online shopping, but few call the police. Victims who aged above 45 are commonly deceived by fraud involving corporate financial and capital use. They generally report these incidences to the police (Ma, 2019). Zou and Lv (2019) believe that the major reasons for the frequent occurrence of phishing are the following: First, citizens are not vigilant about phishing; second, it is easy to commit phishing at a low cost; third, the detection rate of phishing remains low, and the relevant public security force is inefficient; fourth, personal information is not adequately protected by the law, and the relevant regulations are not comprehensive enough; and fifth, telecom operators and banks do not fulfill their obligations responsibly during the phishing process.

Since online payment platforms were established by the banking sector in recent decades, the global commercial risks of phishing have increased. Kadleck (2005) emphasized that as more businesses and clients started to place their money into cyberspace in the 21st century, such as through online banking, mobile finance, etc., the numbers and opportunities of phishing have significantly increased. Shinder (2002) indicated that e-commerce, online banking, and relevant online payment platforms have led to millions of dollars of financial transactions on the Internet annually.

Phishing is related to the banking sector, including banking card fraud, money transfer fraud, and the acquisition of private personal information to gain access to a user’s bank account (Raghavana & Parthiban, 2014). As increasingly more people enjoy online banking services, which are now recognized as the dominant approach to banking services, criminals have also benefited because online banking is faster, does not require any human intervention, and is often more anonymous. Online banking produces large amounts of constructive work while also producing some destructive work. Thus, tracking phishing can be difficult, or even impossible, as phishing are usually concealed (Muleya, 2012). Therefore, advice from banks to their clients when clients transfer their money to unknown accounts is necessary for preventing phishing.

The phishing is always in line with the banking sectors, such as banking card fraud, money transfer fraud, private personal information hackers that executed with the ultimate goal of gaining access to user’s bank account (Raghavana & Parthiban, 2014). As more and more people are enjoying online banking services, which has been recognized as the dominant approach of banking services in nowadays, this also provides conveniences for criminals because the online banking is faster, does not require any human intervention, and is often more anonymous. Online banking produces large amounts of constructive work while producing some destructive work. Thus, tracking down phishing can be difficult, even impossible, as phishing is usually concealed (Bamrara et al., 2012). Therefore, the advising of banks to their clients when they transfer the money to the unknown accounts is a necessary in preventing the phishing.

Ma (2019) conducted an empirical study on the overall situation of phishing in China. They determined that the emergence and rapid growth of phishing in China has resulted in large property losses for both Chinese citizens and the banking sector in China. They compared the data on phishing in Liaoning and Guangdong provinces. The empirical results of their research showed that the phishing situation in each province in China varies and that the status is most severe in developed regions, such as Guangdong province. Moreover, Zhang et al. (2019) stated that promoting the legal system and strengthening the cooperation among the police, telecom companies, and banks could lower the incidence of phishing in China.

Research Objectives and Hypothesis Development

The public security force uses various detection procedures in different contexts when phishing occurs (Abu-Shanab & Matalqa, 2015). The Ministry of Public Security has set up the steering group of Operation “Cloud Sword” (Yunjian) headed by Vice Minister Du Hangwei. Since launching this special agency, the public security across the whole country have acted decisively to take a battle of data and technology with multiple measures that against the phishing (Ma, 2019). So far, this agency has achieved remarkable outcomes with 118,000 phishing solved that was 62.5% rising year-on-year. And there were 9,000 suspects have been arrested, which was 135.6% rising year-on-year (Zou & Lv, 2019).

On 16 December 2019, the Money-shield Anti-Fraud Robot launched by the Criminal Investigation Department of the Ministry of Public Security and Alibaba started running officially. Through the caller identification of “anti-fraud special numbers locked by the police”, public security established an early warning system that sends a warning to potential victims over the phone, as well as through messages (Wu et al., 2019). These communications improve the success rate of anti-fraud dissuasion and reduce the incidence of phishing, while securing citizens’ property. For example, the incidence of phishing in Beijing is high, especially cases related to the pandemic of COVID-19. In response, Beijing public security launched a special action to fight phishing. By 22nd April, five criminal gangs had been shut down, and 35 criminal suspects had been captured and detained for assisting in phishing. Therefore, the first objective of this research is as follows:

Objective One (XA). To verify that public security force involvement has a positive impact on preventing phishing

According to this objective, we formulated the following hypotheses:

XA1: Education and publicity from the public security force positively influence the prevention of phishing.

XA2: The effectiveness of public security force involvement positively influences the prevention of phishing.

XA3: The efficiency of public security force involvement positively influences the prevention of phishing.

With the successive development of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), telecom operators have been empowered to better supervise their clients, thereby avoiding property losses and advising other associated sectors in ways to limit the incidence of phishing (Mwaita & Owor, 2013). With the aim of preventing phishing, Chinese telecom operators implemented a real-name registration system that requires clients to submit information using their real identities when providing internet access and fixed landline and mobile phone service.

In addition, Voice over Internet Protocol phone (VOIP) offers great convenience and allows clients to easily exchange their information, but it has its own security loopholes. Voice information privacy is extremely vulnerable to eavesdropping. Once connected to a wireless network, it is difficult to pinpoint the call’s location, makes it even more challenging to monitor, which not only makes it difficult to crack down on phishing but also facilitates it and problematizes detection. Furthermore, telecom operators are not as vigilant in supervising their clients when they receive phone calls, so it is important to give warnings to customers and help the government draft adequate and effective legislation to fight phishing (Mwaita & Owor, 2013).

However, this system was not well implemented previously. There are still some cell-phone warehouses that sell SIM cards without requiring verification of personal identification or allow one to purchase SIM cards under staff members’ names and resell them. This phenomenon allows a large number of suspects of phishing to easily obtain unregistered SIMs for cell-phone and network services (Liu et al., 2015). Therefore, network operators in China have implemented a system of real-name registration for 100% of their clients since 30 June 2017. Telecom experts generally believe that a real-name registration system can both limit phishing and allow clients to protect their rights and interests (Wu et al., 2019). After implementation, identity verification can determine the source of each message and phone call, which helps with the detection of and asset recovery from phishing. Therefore, the second objective of this research is the following:

Objective Two (XB). To verify that the telecom operator has a positive impact on preventing phishing

According to this objective, we formulated the following hypotheses:

XB1: Education and publicity provided by telecom operators positively influence the prevention of phishing.

XB2: The anti-fraud warnings provided by telecom operators positively influence the prevention of phishing.

XB3: Case tracking by telecom operators positively influences the prevention of phishing.

The countermeasures to address phishing in China may face problems in substantive and procedural law because the legal system governing phishing is incomplete, and the technology to prevent phishing lags behind the development of phishing. Li and Zhao indicated that the current Criminal Law of China has not yet identified phishing as a unique law (Li & Zhao, 2018). In the judicial procedure, there is no particular punishment that addresses phishing. Such judgments are considered in accordance with the methods for dealing with the common crimes of swindling, fraud, infringement of citizens’ personal information, and the illegal use of the internet.

Although the Amendment of the Criminal Law (9th edition) fills this legal gap to a certain extent (Zou & Lv, 2019), it fails to cover all types of phishing, which may lead to a problem of there being “no law to abide by” in the process of fighting against phishing. Zhou and Tang (2016) believe that the relative interpretations and supplementary regulations for phishing are insufficient. The criminal law reflects its justice through the principles of legality and punishment equivalent to guilt, but the many regulations related to legislative and judicial interpretations of ordinary fraud rarely involve the newly emerging phishing. In particular, the types of cybercrime are manifold. The existing regulations are not sufficient to reflect the negative impacts of phishing. Moreover, the amount of money involved in phishing is usually large, but the present legal punishments significantly reduce the deterrent power of the criminal codes, which are not conducive to combating phishing. Hence, on 4 March 2016, the Supreme People’s Court outlined some specific cases of typical phishing, in China (Ma, 2019). This report attested that phishing should be convicted and punished in the same way as ordinary fraud, which reflects the legislator’s basic identification of phishing as a new form of traditional fraud in the present information technology era that should be punished according to existing Criminal Law.

Furthermore, cybercriminals have a tendency to be of a younger age. Due to the lack of policy and regulations for dealing with young cybercriminals, such juveniles cannot be classified as criminals, even if they engage in the process of phishing. Moreover, phishing criminals usually adopt a one-way connection, so the members at lower levels have little understanding of the members at higher levels. It is difficult to obtain valid evidence to prove criminal connections among criminal suspects during the investigating process. Therefore, better legislation initiatives would help limit the incidence of phishing. The third objective of this research is thus formulated as follows:

Objective Three (XC). To verify that legislation mechanisms have a positive impact on preventing phishing

According to this objective, we formulated the following hypotheses:

XC1: The relative legalization mechanisms for phishing prevention and tracking positively influence the prevention of phishing.

XC2: The relative legalization mechanisms for phishing punishment positively influence the prevention of phishing.

XC3: The relative legalization mechanisms for phishing prosecutions and convictions positively influence the prevention of phishing.

Zhou and Tang believe that to prevent phishing, it is necessary to increase the risk and cost of phishing and strengthen advocacy in civil society, while placing personal information in safe custody and increasing awareness of financial security among the public (2020). Moreover, policing institutions should bolster their investigative capacities to fight against phishing. To ameliorate the economic losses of victims, the Ministry of Public Security has established a multitude of early warning systems and interception systems by collaborating closely with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the Cyberspace Administration of China to popularize the 96110 anti-fraud special line, while constantly improving the ability of early warning and detection. This system has pushed more than 1.7 million early warning messages, shielded 1.016 million potential victims, and recovered direct economic losses of 5.61 billion RMB. To initiate a 24–7 emergency system that can stop payments, the People’s Bank of China has cooperated with the China Banking Regulatory Commission to suspend 550,000 suspected banking accounts, and 37.38 billion RMB was intercepted in 2020 (Hipolito et al., 2020).

The establishment of anti-fraud centers is another example of cooperative governance. For instance, on 30 March 2016, the Public Security Bureau of Quanzhou city set up an anti-fraud center as a governance institution consisting of the Communication Administration, the Banking Regulatory Commission of Quanzhou, and the Center Sub-branch of the People’s Bank of China in Quanzhou under the leadership of the Public Security Bureau (Li & Zhao, 2018). This institution specifically covers the offices of public relations, propaganda, network detection, economic investigation, criminal investigation, and the headquarters of the public security bureau, along with three major communication operators (China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom) and eight banking institutions. At the same time, 24 h departments, such as the communication prevention and control office, the financial prevention and control office, the case disposition office, and the anticipation strike office were established with the specific roles of answering alarms, intercepting the money involved in crimes, suspending the phone numbers involved, and investigating and unearthing cases. Moreover, each level of the Quanzhou Government has joined with the anti-fraud network under the leadership of public security. To expand public awareness and participation, LED screens on buses and major buildings are used to make swindling cases public, combined with television stations and related media (Wu & Li, 2018).

This is a crucial situation, where public security forces, telecom operators, banks, and other organizations should create an alliance against the threat of phishing (Kritzinger & Solms, 2012). As Usman and Shah (2013) stated, phishing, is a worldwide problem for the police and for all individuals. This brings us to the fourth objective of this paper:

Objective Four (XD). To verify that the Cooperate Governance issue has a positive impact on preventing phishing

According to this objective, we formulated the following hypotheses:

XD1: The degree of cooperative governance will positively increase public awareness of preventing phishing

XD2: The degree of cooperative governance will positively increase the effectiveness of preventing phishing

XD3: The degree of cooperative governance will positively increase the efficiency of preventing phishing

Materials and Methods

Research Design and Data Collection

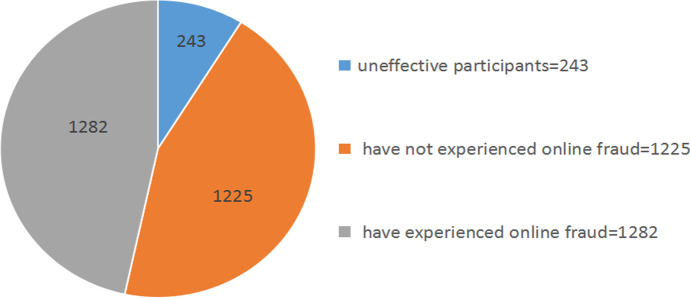

This empirical paper is supported by the Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 72074095). In this research, the authors conducted a survey that gathered data Guangdong province, Jiangsu province, and Shandong province, where most phishing crimes occur in China. The questionnaire was titled “An Assessment of the Roles of Phishing in challenging the development of the China’s Banking Industry”. The authors distributed 2750 questionnaires (1000 from Guangdong, 1000 from Jiangsu, and 750 from Shandong), and there were 2507 effective responses; thus, the effective response rate was 91.16% (See Fig. 2). In this questionnaire, a logical jump was established in the design. The first question of this survey was "Have you ever experienced online fraud?" If a participant chose “No”, the survey would be ended automatically. When “Yes” was selected, the participant would continue to answer the following questions of this survey. After screening (i.e., after the initial question was selected as "Yes"), the valid number of questionnaires was 1,282. The questionnaire was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale: 1—Completely Negative (0–20), 2—Partly Negative (21–40), 3—Neutral (41–60), 4—Partly Positive (61–80), and 5—Completely Positive (81–100). The statistical analysis method and structural equation model were employed to analyze the results of the feedback.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the survey participants

Instrument

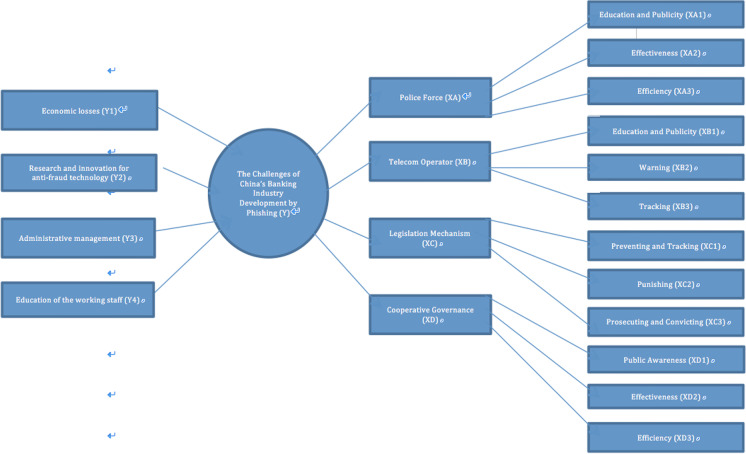

In this survey, the dependent variable was set as “phishing is challenging the future development of China’s banking industry” (Y). This variable consists of four aspects: economic losses (Y1), investment into research and innovation for anti-fraud technology (Y2), administrative management (Y3), and education of the working staff (Y4). There are four factors involved in this survey as independent variables: public security force involvement (XA), telecom operators (XB), legislation mechanisms (XC), and cooperative governance issues (XD). Three questions were set up for each dimension of the independent variable, which means that there were 16 questions in total in this survey (see the appendix). All of the statistical analyses were two-tailed and performed using SPSS (26 Version) and Mplus (8.3 MAC Version).

According to the basic assumptions of this research, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) was built (See Fig. 3). The explained variables are composed of four questions, respectively examining the impact of phishing scams on future economic losses, research investment, and the administration and staff working in the banking industry. The explanatory variables were set under four dimensions: XA, XB, XC, and XD, respectively, representing the influence of public security departments, telecommunications departments, legal departments, and civil organizations on the explained variables. Three questions were set for each dimension: XA1, XA2, and XA3 for public security departments; XB1, XB2, and XB3 for telecommunications departments; XC1, XC2, and XC3 for relevant legal departments; and XD1, XD2, and XD3 for civil organizations. An exploratory factor analysis, a reliability analysis, a confirmatory factor analysis, and an SEM (Structural Equation Model) analysis were conducted on the 1282 existing data points.

Fig. 3.

The research framework

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Ultimately, 210 questionnaires were randomly selected from the 1282 total samples as subjects, and SPSS26 was used for the exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that KMO=0.713, and Bartlett spherical test =1137.419 (DF =120, P < 0.001), which indicates that the selected sample set was suitable for the exploratory factor analysis. Furthermore, the factors were extracted by the principal component method, and Promax procrustes variance maximum—olique rotation was performed. The specific Pattern matrix is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pattern matrix

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y4 | 0.832 | ||||

| Y1 | 0.811 | ||||

| Y3 | 0.809 | ||||

| Y2 | 0.807 | ||||

| XA3 | 0.864 | ||||

| XA1 | 0.838 | ||||

| XA2 | 0.823 | ||||

| XD3 | 0.860 | ||||

| XD2 | 0.833 | ||||

| XD1 | 0.818 | ||||

| XB3 | 0.862 | ||||

| XB1 | 0.834 | ||||

| XB2 | 0.828 | ||||

| XC1 | 0.842 | ||||

| XC2 | 0.838 | ||||

| XC3 | 0.821 |

Reliability Analysis

Cronbach's Alpha is the most commonly used homogeneity reliability testing method. Internal reliability analyses are often implemented in project analyses. Churchill (1979) notes that if the correlation degree of the index (CITC, Corrected Item Total Correlation) is less than 0.5, then the index should be deleted and the coefficient should be calculated. If the value is above 0.6, the index reliability is acceptable; otherwise, the index should also be deleted. The Cronbach’s internal consistency reliability values of the five factors for the explanatory variables and the explained variables in this study were consistently higher than 0.7, which indicates that the questionnaire had good reliability (See Table 2).

Table 2.

The reliability analyses

| Variables: | Cronbach’s |

|---|---|

| XA | 0.753 |

| XB | 0.771 |

| XC | 0.766 |

| XD | 0.757 |

| Y | 0.882 |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The authors observed the variables of the questionnaire by using Mplus 8.3 to test the fitting of the confirmatory factor analysis model to measure the fitting index compared with the ideal indicators (See Table 3). All indexes were fitted ideally for the confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis

| χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Index | 1.613 | 0.981 | 0.979 | 0.025 | 0.021 |

| Ideal index | < 5 | > 0.9 | > 0.9 | < 0.05 | < 0.08 |

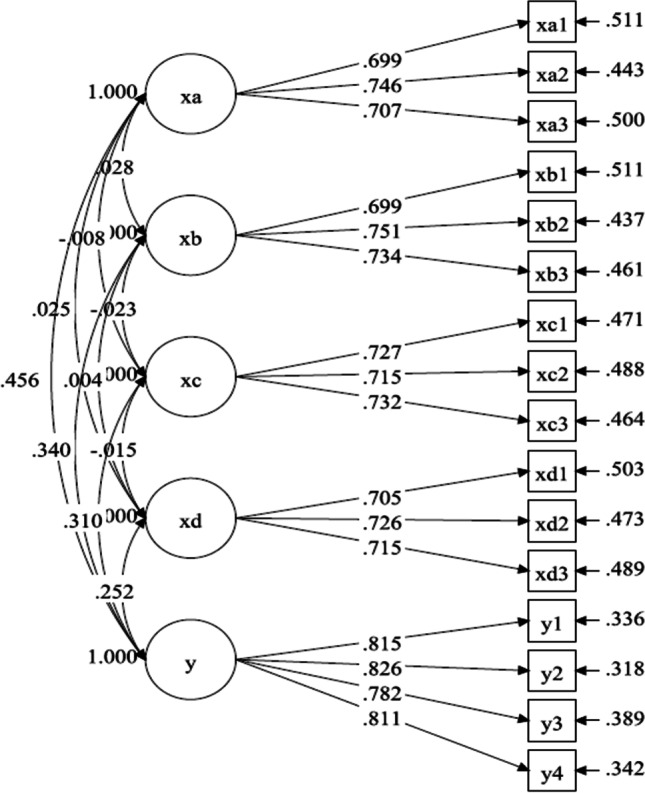

Based on the previous analysis, we developed a Standardized Estimate (SE) for determining whether the variables can better reflect the content and characteristics of latent variables and how to measure the impact of the latent variables. When β ≤ 0.6, the observed variable reflects the latent variable to poorly to accurately describe the characteristics and content of the latent variable; thus, the index is deleted. When 0.6 < β ≤ 0.7, the observed variable reflects the latent variable well and can accurately describe the characteristics and content of the latent variable; thus, it should be retained. When 0.7 < β ≤ 1, the observed variable reflects the latent variable well and can accurately describe the characteristics and contents of the latent variable, so it also needs to be retained. As shown in Table 4, almost all standardized path coefficient estimates are above 0.7 and were thus retained.

Table 4.

The fully normalization factor test

| Factor | Item | Standardized | S.E | Est./S.E | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate β | |||||

| XA | XA1 | 0.699 | 0.021 | 34.017 | 0.000 |

| XA2 | 0.746 | 0.020 | 38.207 | 0.000 | |

| XA3 | 0.707 | 0.020 | 35.140 | 0.000 | |

| XB | XB1 | 0.699 | 0.020 | 34.266 | 0.000 |

| XB2 | 0.751 | 0.019 | 38.602 | 0.000 | |

| XB3 | 0.734 | 0.020 | 37.574 | 0.000 | |

| XC | XC1 | 0.727 | 0.020 | 36.290 | 0.000 |

| XC2 | 0.715 | 0.020 | 35.471 | 0.000 | |

| XC3 | 0.732 | 0.020 | 36.222 | 0.000 | |

| XD | XD1 | 0.705 | 0.021 | 33.417 | 0.000 |

| XD2 | 0.726 | 0.021 | 34.754 | 0.000 | |

| XD3 | 0.715 | 0.021 | 33.827 | 0.000 | |

| Y | Y1 | 0.815 | 0.012 | 68.977 | 0.000 |

| Y2 | 0.826 | 0.011 | 72.171 | 0.000 | |

| Y3 | 0.782 | 0.013 | 59.587 | 0.000 | |

| Y4 | 0.811 | 0.012 | 67.829 | 0.000 |

As shown in Fig. 4, these are the coefficients of the fully normalized path for this research.

Fig. 4.

The coefficients of the fully normalized path

In addition, the path coefficient between latent variables was explained. When β ≤ 0.2, the influence degree between the latent variables is small and relatively independent. When 0.2 < β ≤ 0.4, the interaction between the latent variables should be considered in the modeling. However, when 0.4 < β ≤ 0.6, the latent variables have a greater degree of influence and are not independent of each other, which needs to be reconsidered. It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the path coefficients between the latent variables are all less than 0.4. Therefore, the structural equation model established in this study is reasonable and effective.

Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Finally, this study constructed a structural equation model with XA, XB, XC, and XD as the independent variables and Y as the dependent variable. Mplus8.3 was used to conduct a fitting test on the constructed model, and the fitting indexes measured by the structural model were compared with the ideal indexes, as shown in Table 5. It can be seen that all the fitting indexes are within the ideal range, and the constructed model has a good fitting degree. Coefficients of the fully normalized path were shown in Fig. 5.

Table 5.

Structural equipment model fitting form

| χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Index | 1.521 | 0.987 | 0.981 | 0.022 | 0.020 |

| Ideal Index | < 5 | > 0.9 | > 0.9 | < 0.05 | < 0.08 |

Fig. 5.

Coefficients of the fully normalized path

Figure 5 the coefficients of the fully normalized path of this research.

Table 6 shows the significance test results of the path coefficients of the structural equation model. The path coefficient significance test showed that XA had a significant positive impact on Y(Estimate = 0.619, P < 0.001). Therefore, H1 is validated; XB had a significant positive impact on Y(Estimate = 0.413, P < 0.001). Therefore, H2 is verified; XC had a significant positive impact on Y(Estimate = 0.336, P < 0.001). Therefore, H3 is verified; XD had a significant positive impact on Y(Estimate = 0.329, P < 0.001). Therefore, H4 is validated. The influence strengths of the four independent variables were 0.443, 0.334, 0.324, and 0.245, respectively. It can be seen that XA has the greatest influence on Y, XB has the second greatest influence, XC the third greatest influence, and XD the least influence on Y. These results demonstrate that the participants of the survey realized that public security force involvement will have the most significant influence on phishing (which challenges the future development of China’s banking industry). The second most influential forces are the telecom operators, while legislative initiatives rank third. The issue of cooperative governance is the weakest among these factors.

Table 6.

Path coefficient significance test

| DV | IV | Estimate | S.E | Est./S.E | Standardized | p | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | |||||||

| Y | XA | 0.619 | 0.046 | 13.527 | 0.443 | 0.000 | H1 |

| XB | 0.413 | 0.038 | 10.889 | 0.334 | 0.000 | H2 | |

| XC | 0.336 | 0.032 | 10.429 | 0.324 | 0.000 | H3 | |

| XD | 0.329 | 0.041 | 8.070 | 0.245 | 0.000 | H4 |

Discussion

Due to the rapid development of Internet technology, phishing has become a new form of crime in the cyber era. Phishing appears to be the work of cyber experts who use their knowledge of ICT through portals for fraudulent purposes (Broadhurst et al., 2014). Phishing is a diverse social problem. Its governance is not a task that policing and public security can independently work on but a job that requires several associated sectors to coordinate and contribute to China, the country with both the largest overall population and the largest population of cyber citizens in the world, faces more severe phishing problems than other nations. The imperfect monitoring system in China and its less advanced investigation systems for phishing activities are the main reasons for China’s high incidence of phishing. The lack of precautions among the public, the incomplete policing system, and the rough mechanisms between each associated sector are also facilitating this high occurrence rate and development of phishing in China. Thus, the legislation and administrative supervision systems need to be improved, and the coordination mechanisms among various departments, such as policing institutions, telecom operators, etc., which can help prevent phishing, need to be further strengthened that can promote the future development of China’s banking industry.

The public security force is assumed as the main role in maintaining social security and cracking down on phishing and related crimes. Phishing is a type of fraud that involves the use of communication facilities, applications, and networks (Luminita et al., 2011). This means that it might be challenging for policing institutions, the public security sector, and judicial departments to investigate, obtain evidence, and prepare their conclusions, as the communication facilities and instruments used in phishing may be destroyed after the criminal perpetrates the crime. This has changed the approaches to policing phishing, from solving such crimes to preventing their incidence.

From the perspective of detection, phishing is a dark industrial franchise. Such activities include telecom operators trading citizens’ personal information to fraudsters; criminals working in financial institutions such as banks, credit cards companies, etc. selling the bank account details of their clients; and criminals using third-party payment platforms to receive, transfer, and launder illicit money; these are all key points for policing institutions to investigate.

To limit the incidence of phishing, it is necessary to eradicate the upstream and downstream sources of cybercrime. Thus far, policing institutions have focused on investing and detecting all aspects that provide ‘services’ to phishing and then carrying out large-scale attacks on cybercriminals. Moreover, the public security force, and judicial departments should take the initiative in recruiting and training experts to improve the techniques for policing phishing. Moreover, public security forces are playing a leading role in coordinating the various resources of relevant sectors for preventing phishing. According to the research by Ma, China detected 5396 phishing cases in 2017 (Ma, 2019).

Phishing is generally conducted through phone calls, text messages, Internet applications, and other cyber communication methods. The telecom sector and the operators themselves have social responsibilities to prevent this kind crime proactively. Zou and Lv (2019) note that all telecom operators should be able to manage dedicated circuits, server gateways, and call centers for suspected companies. In China, telecom operators are very strict in implementing real-name registration for every land-line and mobile phone during the initialization process. Telecom operators should enforce up-to-date technical security measures, such as anti-virus applications, regularly and associate with banks and financial institution to develop unique software for online banking applications. They should also set up regular checks and long-term observational mechanisms to monitor and manage the implementation status of the real-name registration system for telecom lines. If abnormal activities are detected, the telecom sector would ask public security forces to participate in a further investigation. Furthermore, the telecom sector would give the caller identification for each formally registered organization and provide the full information of their institutes to the telecom operators. The public could then easily recognize the functions and purposes of such companies when receiving a fraudulent call. This has been one of the most effective methods for preventing phishing in China.

When monitoring suspected telephone scams, a suspected phone number should be sent immediately to public security forces for verification, blocking, and interception if the number is trying to call a batch of local access numbers automatically and send mass text messages. Furthermore, the public security forces should establish a blacklist of such phone numbers and become actively involved in phishing to help prevent incoming calls based on their numbers.

To sum up, the role of telecom operators in preventing phishing and controlling its occurrence rate is strictly to filter out users who transmit illegal information. Telecom operators also need to inform users about new phishing methods and techniques to prevent them by sending text messages. Telecom operators should, moreover, implement a real name registration system when selling SIM cards.

The banking sector and third-party payment platforms also act as an important barricade for the asset safety of their clients, as such platforms know the specific flows of banking transactions. They constitute a critical element for policing phishing. The banking sector should intensify its inspections and supervision of online banking transfers, as well as the facility of the ‘emergence stop payment’ function. Ikechi and Okay (2013) argue that the banking sector is the last firewall against phishing and should inform citizens about whether they should transfer their money to an unknown account. Moreover, third-party payment platforms scrutinize accounts with frequent cash flows and manage restrictions on the amount of payments. For instance, third-party payment platforms generally set up anti-fraud mechanisms that notify clients of potential phishing and offer them the option of deferring their money transfer.

In the wake of the ever-increasing use of online banks and financial management applications, banks and financial institutions need to make the public aware of the negative effects of phishing and related cybercrimes (Tan, 2002). They are responsible for educating the public in minimizing the risk of betraying one’s privacy, including personal information, banking details, and electronic properties, to fraudsters. It is important not only to help people avoid phishing but also to draft adequate and effective legislation (Mwaita & Owor, 2013).

In China, the People's Bank of China and the China Banking Regulatory Commission should strengthen the management of bank cards, regulate the process of opening a bank account, fight against the illegal buying and selling of bank cards, and urge all commercial banks to implement a new account-opening system based on real-name registration. Moreover, the People's Bank of China should, alongside policing institutions, further strengthen its supervision of the disordered operations of commercial initiatives by third-party payment platforms. In cases of suspected fraud, third-party payment platforms should stop the payment and transfer process and then provide the full information of the suspect to the police with 24 h once the case has been reported to the proper authorities. Likewise, the banking sector should promptly suspend payments from an illegal account that is identified by the police. These measures could minimize the asset losses of victims.

The primary type of phishing involves criminals who compel their victims to transfer their money to a bank account, where the money is quickly dispersed and transferred again to other bank accounts. Through the analysis of big data, banks could identify such suspicious accounts. Once transfer behavior with the characteristics of phishing is found, the bank could immediately report it to the police and stop payments.

The banking industry has concentrated on detecting and preventing phishing. Many of the employees of banks have been increasingly vigilant in this area. When encountering suspicious customers, such employees have successfully resolved some cases of fraud, thereby helping customers avoid greater property losses. However, with the rapid development of science and technology, phishing has become impossible to prevent with these more passive approaches. Moreover, some people sell citizens’ personal information for profit, which is an important driver behind the high incidence of phishing. The efforts of bank staff alone cannot fundamentally alleviate the increasingly rampant situation of phishing.

In recent years, the Chinese government has set up specialized agencies to deal with phishing. At the same time, publicity and education have increased the safety awareness of relevant institutions and individuals. However, at present, phishing still has a high incidence. Relevant departments and banks should draw lessons from their successful experiences dealing with such crimes and constantly summarize the characteristics of the flows of funds that are involved in phishing. Preventing the incidence of phishing is one of the most important challenges for the development of China’s banking industry.

Research Limitations and Prospects

This study has several limitations. First, we primarily used the quantitative method. The data were collected through questionnaires from three provinces in China. We did not distribute the questionnaires to the respondents by number, but rather only by the locations where the phishing mostly emerge in China. The results from the feedback may not be accurate or fully reflective. Further studies are needed to draw conclusions about other provinces. Second, the survey respondent perceptions are substituted for objective measures of key factors affecting China’s banking industry in preventing phishing, such as administrative management and education on the staffs of banks. These are troubles, as some participants may have limited knowledge.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to demonstrate that phishing and related cybercrimes are challenging the future development of China’s banking industry. Empirical research shows that public security force involvement, communication operator involvement, legislation initiatives, and cooperative governance positively affect the prevention of phishing. As mentioned in the literature review and hypothesis development sections, there are four hypotheses in this research. Public security force involvement and communication operator involvement involve the external interruption of phishing crimes. Legislation initiatives are recognized as a guide for the regulation, management, and limitation of phishing by facilitating administrative frameworks and procedures. The cooperative governance issue refers to the public participation in activities focused on the anti-cybercrime process. According to our results, these issues all have positive influences on China’s banking industry in preventing the incidence of phishing.

The findings of this study provide three contributions. First, we explored how public security force involvement, communication operator involvement, legislation initiatives, and cooperative governance positively affect the prevention of phishing in China. Second, we observed that phishing negatively influences the development of China’s banking industry. Third, we found analytical and methodological variables that can be used to supervise the further implementation of these initiatives to both prevent phishing and assist in the development of China’s banking industry. This paper is the first comprehensive study on phishing that is focused on China’s banking industry. Our findings have crucial implications in the literature on the banking security, banking sector reform, and policy evaluation, as phishing provides challenges to the future development of the banking industry in China.

Biographies

Yanzhe Zhang

is a Professor at Northeast Asian Research Center of Jilin University, China.

Yutong Shao

is a Phd Candidate at Northeast Asian Research Center of Jilin University, China.

Jian Zhang

is a Lecture at School of International Economics and International Relations of Liaoning University, China

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (72074095).

Declarations

None.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yanzhe Zhang, Email: yanzhe_zhang@jlu.edu.cn.

Jian Zhang, Email: jianzhangccit@sina.com.

References

- Abu-Shanab E, Matalqa S. Security and fraud issues of E-banking. International Journal of Computer Networks Applications. 2015;2:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Aseef N, Davis P, et al. Cyber-criminal Activity and Analysis. White Paper; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bamrara A, Singh G, Bhatt M. An explorative study of satisfaction level of cyber-crime victims with respect to E-Services of banks. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce. 2012;17(3):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst R, Grabosky P, Alazab M, Chon S. Organizations and Cyber Crime: An analysis of the nature of groups engaged in Cyber Crime. International Journal of Cyber Criminology. 2014;8(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Zhang S, Li Z, Zhang Y, Deng Q, Ray S, Jin Y. Internet-of-things security and vulnerabilities: Taxonomy, challenges, and practice. Journal of Hardware and Systems Security. 2018;2:97–110. doi: 10.1007/s41635-017-0029-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clough J. Principles of cybercrime. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Felson M. Social change and crime rates: A routine activities approach. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:214–241. doi: 10.2307/2094589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hipolito, C. N., Hernández-Sánchez, F., Aguilera-Morales, M. E., Lorenzo-Manzanarez, J. L., Navarro-Moreno, L. G., & Tan, Y. H. (2020). The effect of different cooking methods on the nutritional composition f tilapia (oreochromis sp.). Journal of Applied Science & Process Engineering 1.

- Ikechi KS, Okay OE. The nature, extent and economic impact of fraud on bank deposits in Nigeria. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business. 2013;4(9):253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Irshad, M. (2016). A Systematic Review of Information Security Frameworks in the Internet of Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications; IEEE 14th International Conference on Smart City; IEEE 2nd International Conference on Data Science and Systems (HPCC/SmartCity/DSS), Sydney, Australia, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 1270–1275.

- Kadleck, C. (2005). Banks battle against growth of electronic payment fraud. Crain’s Cleveland Business,26(3). Available online: http://www.craincleveland.com/. Accessed 8 May 2020.

- Kritzinger, E., & von Solms, S. H. (2012). A Framework for Cyber Security in Africa. Journal of Information Assurance and Cybersecurity, 10, 322399.

- Li YL, Zhao R. The empirical analysis on the procedures of computer program of telecom fraud: A case of Chongqing city. Journal of Chinese Procurator. 2018;22:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Yu W, Zhang N, Yang X, Zhang H, Zhao W. A survey on internet of things: Architecture, enabling technologies, security and privacy, and applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2017;4:1125–1142. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2017.2683200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Zhang, J., Qin, H., Zeng, J. (2015). Dynamic Defense Architecture for the Security of the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2015 11th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security (CIS), Shenzhen, China, 19–20 December 2015; pp. 390–393.

- Liu SF, Sun XF. Theory of Cybercrime. Journal of Peking University (philosophy and Social Science Edition) 2001;3:114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Luminita I, Viorica M, Adrain B. Fraud, corruption and cyber-crime in a global digital network. Economics, Management and Financial Markets. 2011;6(2):373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Ma RL. The empirical research on the victims of Ping Ding Shan City. Journal of Enterprises in Hebei Province. 2019;2:138–139. [Google Scholar]

- Muleya. (2012). Detective Assistant Inspector Tom Muleya and Superintendent Moyo Ndabazihle. Available online: http://www.techzim.co.zw/2012/03/zim-police-join-the-cyber-warfare/. Accessed 16 Mar 2020.

- Mwaita, P., & Owor, M. (2013). Workshop Report on Effective Cybercrime Legislation in Eastern Africa, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.

- Raghavana AR, Parthiban L. The effect of cybercrime on a Bank’s finances. International Journal of Current Research & Academic Review. 2014;2(2):173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Rastenis J, Ramanauskaitė S, Janulevičius J, Čenys A, Slotkienė A, Pakrijauskas K. E-mail-based phishing attack taxonomy. Applied Sciences. 2020;10:2363. doi: 10.3390/app10072363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinder DL. Scene of the Cybercrime: Computer Forensics Handbook. Syngress Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tan ST. Money laundering and E-commerce. Journal of Financial Crime. 2002;9(3):277–285. doi: 10.1108/eb026027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The network security during the epidemic prevention and control period in China. 10th March, 2020. Available online: http://www.cyberpolice.cn/wfjb/html/xxgg/20200310/4739.shtml. Accessed 2 May 2020.

- Usman AK, Shah MH. Critical success factors for preventing e-Banking Fraud. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce. 2013;18(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., Liu, C., Qiu, J., Tian, Z., Cui, X., Su, S. (2018). Automatically Traceback RDP-Based Targeted Ransomware Attacks. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing.

- Wu ZM, Li YT. The empirical analysis on the situation of telecom fraud in China. Journal of Wuhan Police Cadre College. 2018;3:56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Zhang Y, Ma M, Kumar N, He D. Certificateless searchable public key authenticated encryption with designated tester for cloud-assisted medical Internet of Things. Annals of Telecommunications. 2019;74:423–434. doi: 10.1007/s12243-018-00701-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria S. The impact of identity theft on perceived security and trusting E-Commerce. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce. 2013;18(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xiao X, Mercaldo F, Ni S, Martinelli F, Sangaiah AK. Classification of ransomware families with machine learning based on N-gram of opcodes. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019;90:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.future.2018.07.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K., Ge, L. (2013). A Survey on the Internet of Things Security. In Proceedings of the 2013 Ninth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security, Leshan, Sichuan, China, 14–15 December 2013; pp. 663–667.

- Zhou K, Tang P. The ‘Internet Plus’ and Cybercrime. Journal of Liaoning Police College. 2016;3:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Jia Y, Peng A, Zhang Y, Liu P. The effect of IoT new features on security and privacy: New threats, existing solutions, and challenges yet to be solved. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2019;6:1606–1616. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2018.2847733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou DP, Lv QN. Analysis of preventing the telecom fraud. Journal of Huainan Polytechnic. 2019;2:118–119. [Google Scholar]