Abstract

The prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) has been increasing, and MDD is now a leading cause of global disability. Depression often coexists with anxiety, and the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) introduced the ‘anxious distress’ specifier to identify those patients within the MDD category who have anxiety as well. The prevalence of anxious depression is high, with studies suggesting that 50–75% of patients with MDD meet the DSM-5 criteria for anxious depression. However, it can be difficult to discern whether a patient has MDD with anxiety or an anxiety disorder that has triggered an episode of depression. In fact, approximately 60–70% of patients with comorbid anxiety and depression experience anxiety first, but it is often depression that leads the patient to seek treatment. Patients with MDD who also have anxiety have significantly worse psychosocial functioning and poorer quality of life compared with patients with MDD without anxiety. In addition, patients with MDD and anxiety take significantly longer to achieve remission, and are less likely to achieve remission, than patients with MDD without anxiety. Therefore, it is essential that physicians have a high index of suspicion for comorbid anxiety in patients with depression, and that anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD are effectively treated. This commentary is based on a virtual symposium presented at the 33rd International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) World Congress, Taipei, Taiwan, in June 2022.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Diagnosis, Treatment

Key Summary Points

| Anxiety is a common comorbidity in patients with depression, and contributes to worse psychosocial function and quality of life. |

| The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) introduced the ‘anxious distress’ specifier to identify patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and comorbid anxiety. |

| It can sometimes be difficult to discern whether anxiety triggers depression or depression triggers anxiety. |

| Irrespective of which condition is antecedent, it is important to identify and treat both anxiety and depression because patients with this combination of comorbidities take significantly longer to achieve remission, and are less likely to achieve remission, than patients with MDD without anxiety. |

Introduction

The number of patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) has been steadily increasing over the last two decades [1], and MDD is now a leading cause of global disability [2, 3]. The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic further increased the prevalence of MDD and anxiety disorders in 2020 [4]. The growing burden of MDD should be a stimulus for further research into this disorder, or spectrum of disorders, to improve the efficacy of treatments for affected patients.

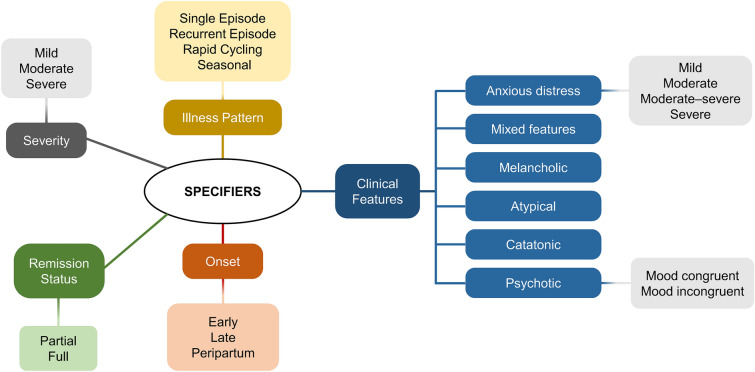

MDD is an extremely heterogeneous condition, and the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) introduced a number of specifiers for MDD in order to subdivide this large and complex category into a more nuanced diagnosis (Fig. 1). This commentary briefly investigates the diagnostic criteria for anxiety in MDD, according to DSM-5, as well as the prevalence of comorbid anxiety and depression and their impact on patients. The content is based on a sponsored symposium presented at the 33rd International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) World Congress, Taipei, Taiwan, in June 2022. Information on contemporary treatment approaches in patients with depression and anxiety symptoms can be found in the article titled ‘Evidence-Based Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Focus on Agomelatine’ in this supplement.

Fig. 1.

Specifiers for major depressive disorder in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [6]

Diagnosis of Comorbid Anxiety and Depression

The diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depression have fluctuated over time [5]. As described above, DSM-5 introduced a number of specifiers for MDD, including ‘anxious distress’ (Fig. 1). The anxious distress specifier is defined by the presence of typical symptoms of anxiety, such as feeling tense or worried, difficulty concentrating, or a sense of loss of control (Table 1). The DSM-5 offers a range of severities for this specifier, based on the number of symptoms present (Table 1) [6]. While the number of symptoms is easily quantifiable, it could be argued that the severity of anxious distress should also be based on the intensity of the symptoms and not simply their number. Zimmerman et al. reported that anxious distress is common in depressed patients, and that individuals with anxious distress had a higher frequency of anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), as well as higher scores on measures of anxiety and depression [7]; such findings support the validity of the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier.

Table 1.

Definition of the ‘anxious distress’ specifier in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [6]

| ‘Anxious distress’ definition | ‘Anxious distress’ severity classification |

|---|---|

| The specifier may be used for patients with at least 2 of the following symptoms during the majority of days of a Major Depressive Episode: | Severity is based on the number of symptoms displayed: |

| Feeling keyed up or tense | 0 or 1 symptom = no anxious distress, |

| Feeling unusually restless | 2 symptoms = mild anxious distress, |

| Difficulty concentrating due to worry | 3 symptoms = moderate anxious distress, and |

| Fear that something awful may happen | 4–5 symptoms = moderate to severe anxious distress (psychomotor agitation must be present) |

| Feeling loss of control of himself or herself |

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the GAD Questionnaire-7 (GAD-7) are short screening instruments used for the detection of depression and anxiety symptoms in various settings, including general and mental health care as well as the general population [8, 9]. While PHQ-9 and GAD-7 have sufficient formal psychometric properties, their clinical utility as diagnostic tools for the recognition of depressive and anxiety disorders is limited in some patient populations [10]; both scales are only recommended as an initial screening tool for the identification of individuals with an increased risk of mental disorders, due to low specificity and high false positive rates, although any positive cases should subsequently be assessed using more comprehensive tools.

The possibility of subthreshold anxiety disorder should also be considered, given that this is reported to be prevalent in the general population, with follow-up studies showing persistent symptoms or progression into an anxiety disorder [11]. Risk indicators, such as reduced functioning, may help physicians to identify these individuals to allow preventative treatment with the goal of reducing functional limitations and disease burden. Of note, the National Institute of Mental Health Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework has prompted the paradigm shift from established diagnostic categories to considering multiple levels of vulnerability to enable probabilistic risk of mental disorder [12]; this framework emphasizes the integration of basic behavioural and neuroscience research.

Prevalence

Studies using the DSM-5 criteria for anxious distress in MDD indicate that this condition is highly prevalent. Zimmerman and colleagues (2017) found that 78% of patients with MDD who had been referred to a US hospital psychiatric department for assessment met the DSM-5 criteria for anxious distress [13]. Similarly, Rosellini and colleagues (2018) reported that, in a cohort of 237 US outpatients with unipolar depression, the anxious distress specifier was present in 66.2% [14]. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), which sampled patients from the community, primary care and outpatient psychiatric services, reported that 54.2% of those with MDD had anxious distress using DSM-5 definitions [15]. This study also found that the DSM-5 specifier was a better predictor of clinical outcomes in patients with MDD compared with the DSM-IV diagnosis of anxiety disorders.

In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) population, approximately 45% of patients with MDD had anxious depression, based on having a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Anxiety-Somatization score of at least 7 [16]. When compared with patients with MDD who did not have anxiety, these patients were significantly more likely to be managed in a primary care than a specialist setting [16]. While this may seem counterintuitive (since it would be expected that more complex patients with MDD would be referred to a specialist), and will vary from country to country, these data do suggest that a significant proportion of patients with MDD and anxiety are not seeing a specialist psychiatrist. It should also be noted that patients with anxious MDD in the STAR*D population included a higher proportion of women, and unemployed, Hispanic and less educated individuals than patients with MDD without anxiety [16], so their predominance in the primary versus specialist care setting may reflect issues related to access or unconscious biases.

In the large National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III (NESARC-III), a population-based study in the US, anxious distress was present in 74.6% of individuals with a lifetime history of MDD [17]. Factors significantly associated with the presence of the anxious distress specifier were younger age at the onset of MDD and at the first treatment for MDD, higher number of lifetime episodes of depression, longer duration of the longest (or only) depressive episode and of the time between the onset of depression and receipt of first treatment, and an increased number of anxiety symptoms [17].

Distinguishing Anxious Depression from an Anxiety Disorder

A key clinical question is whether a patient has MDD with anxiety or an anxiety disorder that has triggered an episode of MDD, and many patients will meet more than one definition of anxiety disorders and/or depression [5]. Often this distinction is based on asking the patient whether they were experiencing anxiety before they became depressed, but many patients with MDD are not able to accurately answer this question.

The World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Surveys found that 68% of patients with lifetime comorbid anxiety and depression developed anxiety before they experienced depression, 13.5% developed depression before anxiety and 18.5% developed both conditions at the same time [18]. Similarly, in NESDA, 57% of patients with comorbid anxiety and depression experienced anxiety first, 18% had depression first, and 25% had simultaneous onset of anxiety and depression [19].

No new diagnostic developments have provided guidance on how to distinguish MDD with anxious distress from GAD with MDD or from MDD with GAD. Usually, the issue of diagnostic differentiation arises at the time of patient presentation, which is most commonly triggered by MDD, and the focus on depression may lead the physician to miss a diagnosis of comorbid anxiety disorders.

Similar issues can arise in patients who have bipolar depression with anxiety, since the DSM-5 diagnosis for bipolar II disorder includes an anxious distress specifier, just as the diagnosis for MDD does [6]. In bipolar depression, the difficulty can be in distinguishing anxious distress from mixed state. However, most psychiatrists are aware of the association between bipolar disorder and anxiety, and should apply the same diagnostic vigilance to identifying anxiety in patients with MDD.

Impact

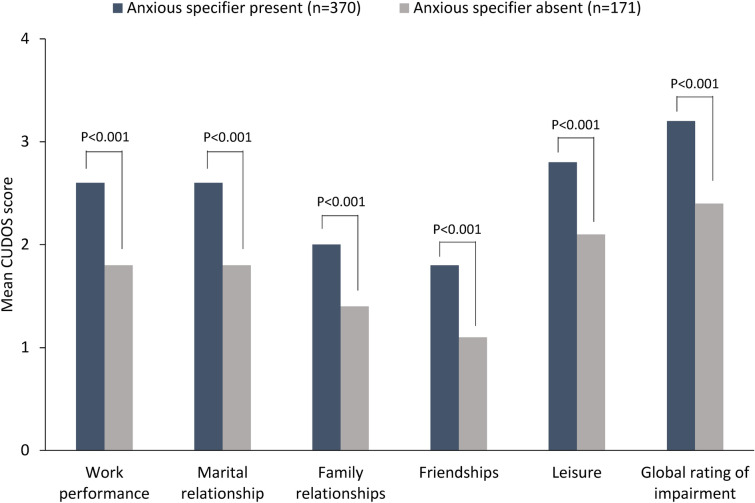

When compared with patients with MDD who do not have anxious distress, those who meet the criteria for the anxious specifier have significantly worse psychosocial functioning across a number of areas, including work performance, marital and family relationships, friendships and leisure (Fig. 2) [20]. In addition, a recent study among Australian inpatients with treatment-resistant depression found that comorbid anxiety (which was present in 78% of the cohort) was associated with significantly worse quality of life [21]. Quality of life in this study was assessed using the 8-dimension Assessment of Quality of Life (A-QoL) instrument, which includes three physical domains (independent living, senses and pain) and five psychosocial domains (mental health, happiness, self-worth, coping and relationships) [22]. Similarly, in the NESARC III study in the US, patients with MDD and anxious distress had significantly worse quality of life measured using version 2 of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey [17]. This study also found that patients with MDD and anxious distress were significantly more likely to think about their own death or suicide, or to attempt suicide, than patients with MDD without anxious distress [17].

Fig. 2.

Impact of the anxious distress specifier on psychosocial functioning in outpatients with depression [20]. Psychosocial functioning was assessed using the Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale (CUDOS) – Anxious Distress Specifier Subscale, in which higher scores indicate a greater negative impact on functioning

Anxiety may also affect response to treatment. A number of studies have shown that patients with MDD and anxiety take significantly longer to achieve remission, and are less likely to achieve remission, than patients with MDD without anxiety [23, 24]. Moreover, among elderly patients with MDD, those with higher scores for anxiety are more likely to have a recurrence of depression than those with no or mild anxiety [24].

Conclusion

Anxiety symptoms are extremely common in patients with MDD, although it is often difficult to ascertain whether the anxiety disorder predated the MDD or vice versa, and therefore whether the diagnosis is anxiety with depression or depression with anxiety. However, irrespective of problems with diagnostic classification, the clinical significance of anxiety symptoms is undisputed, with worse functioning, quality of life and treatment outcomes. Therefore, physicians need to have a high index of suspicion for comorbid anxiety in all patients with depression, because it is essential that anxiety symptoms in patients with MDD are effectively treated.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Servier provided funding for the CINP symposium and for the preparation of the supplement. This funding includes payment of the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

We would like to thank Catherine Rees who provided editorial support for the first draft on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by Servier.

Author Contributions

Dr Hopwood conceptualised the content of the presentation and article, developed the content for presentation, critically reviewed and revised all drafts of the article, and approved the article for submission. Dr Hopwood meets the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and has given his approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

This article and the accompanying articles in this supplement are based on presentations made by the authors at a Servier-funded virtual symposium titled “Anxiety Symptoms in Depression: Contemporary Treatment Approaches”, held in association with the 33rd International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) World Congress in June 2022, in Taipei, Taiwan.

Disclosures

Dr Hopwood has been a speaker for Servier, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Takeda and Otsuka; a consultant for Servier, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Otsuka and Ramsay Health Care; and has received travel support from Servier, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag and Otsuka, and research support from Servier, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, Dia Mentis, Alto Neuroscience and Ramsay Health Care.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- 1.Liu Q, He H, Yang J, Feng X, Zhao F, Lyu J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;126:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Depression. 2021 [updated 13 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression#:~:text=Globally%2C%20it%20is%20estimated%20that,Depression%20can%20lead%20to%20suicide.

- 3.Diseases GBD, Injuries C. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Zimmerman M, Kerr S, Kiefer R, Balling C, Dalrymple K. What is anxious depression? Overlap and agreement between different definitions. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;109:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- 7.Zimmerman M, Martin J, McGonigal P, et al. Validity of the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier for major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(1):31–38. doi: 10.1002/da.22837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pranckeviciene A, Saudargiene A, Gecaite-Stonciene J, et al. Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 and the generalized anxiety disorder-7 in Lithuanian student sample. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0263027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosman RC, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, Muntingh AD, van Balkom AJ, Batelaan NM. Prevalence and course of subthreshold anxiety disorder in the general population: A three-year follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2019;247:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark LA, Cuthbert B, Lewis-Fernández R, Narrow WE, Reed GM. Three approaches to understanding and classifying mental disorder: ICD-11, DSM-5, and the National Institute of Mental Health's Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2017;18(2):72–145. doi: 10.1177/1529100617727266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman M, Clark H, McGonigal P, Harris L, Holst CG, Martin J. Reliability and validity of the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier interview. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;76:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosellini AJ, Bourgeois ML, Correa J, Tung ES, Goncharenko S, Brown TA. Anxious distress in depressed outpatients: prevalence, comorbidity, and incremental validity. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaspersz R, Lamers F, Kent JM, et al. Longitudinal predictive validity of the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier for clinical outcomes in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(2):207–213. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. What clinical and symptom features and comorbid disorders characterize outpatients with anxious major depressive disorder: a replication and extension. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(13):823–835. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336–346. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Sampson NA, Berglund P, et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(3):210–226. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):341–348. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K, Walsh E, Rosenstein L. A clinically useful self-report measure of the DSM-5 anxious distress specifier for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(6):601–607. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurley M, Komiti A, Ting S, Stevens J, Hopwood M. A quality of life and chart review of patients living with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder at a single site in australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2022;56(1_suppl):196–7.

- 22.Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7(1):85–96. doi: 10.1007/s40271-013-0036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiethoff K, Bauer M, Baghai TC, et al. Prevalence and treatment outcome in anxious versus nonanxious depression: results from the German Algorithm Project. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):1047–1054. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05650blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andreescu C, Lenze EJ, Dew MA, et al. Effect of comorbid anxiety on treatment response and relapse risk in late-life depression: controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:344–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.027169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.