Abstract

There have been calls for race to be denounced as a biological variable and for a greater focus on racism, instead of solely race, when studying racial health disparities in the United States. These calls are grounded in extensive scholarship and the rationale that race is not a biological variable, but instead socially constructed, and that structural/institutional racism is a root cause of race-related health disparities. However, there remains a lack of clear guidance for how best to incorporate these assertions about race and racism into tools, such as causal diagrams, that are commonly used by epidemiologists to study population health. We provide clear recommendations for using causal diagrams to study racial health disparities that were informed by these calls. These recommendations consider a health disparity to be a difference in a health outcome that is related to social, environmental, or economic disadvantage. We present simplified causal diagrams to illustrate how to implement our recommendations. These diagrams can be modified based on the health outcome and hypotheses, or for other group-based differences in health also rooted in disadvantage (e.g., gender). Implementing our recommendations may lead to the publication of more rigorous and informative studies of racial health disparities.

Keywords: epidemiologic methods, health status disparities, race relations, racism

Abbreviation

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

There have been calls in the epidemiologic (e.g., Krieger et al. (1, 2)) and other (e.g., Boyd et al. (3), Bailey et al. (4, 5)) literature for race to be denounced as a biological variable and for a greater focus on racism, instead of solely race, when studying racial health disparities in the United States. These calls are based on extensive scholarship and the rationale that race is not a biological variable, but instead socially constructed by historical processes such as historically racist policies (e.g., slavery) and contemporary context (e.g., time and place) (1–4, 6–10); that racism is a root cause of race-related health disparities (3–5); and that an unequal relationship (e.g., privileged vs. marginalized) between racially defined social categories, rather than race conceived of as an innate and immutable biological characteristic of an individual, has caused racial health disparities (1, 2, 11). Although epidemiologists have commonly used causal diagrams (e.g., Greenland et al. (12), Hernán et al. (13–15)) to articulate hypotheses about mechanisms that may produce particular health outcomes as well as to identify potential sources of bias and select approaches to best minimize these biases (e.g., Naimi et al. (16), Adeyeye et al. (17)), including when studying racial health disparities (e.g., Howe et al. (18, 19), Fujishiro et al. (20), Seamans et al. (21), Mayeda et al. (22), Naimi et al. (23), Jackson and VanderWeele (24), and Howe and Robinson (25)), there remains a lack of clear guidance for how best to incorporate the previously mentioned assertions about race and racism into causal diagrams. Therefore, our objectives are to: 1) provide clear recommendations for constructing causal diagrams to study racial health disparities that are responsive to the previously described calls, 2) detail the benefits of each recommendation, and 3) provide examples of simplified causal diagrams that illustrate implementation of our recommendations and that can be modified based on the health disparity or relevant hypotheses. Achieving these objectives may lead to the publication of more rigorous and informative studies of racial health disparities (3).

RECOMMENDATIONS AND BENEFITS

Recommendations for using causal diagrams to study racial health disparities, along with the corresponding benefit(s), are briefly summarized below. These recommendations were developed based on the previously mentioned rationale plus other scholarship (3, 5, 7, 20, 26–31); consider a health disparity to be a difference in a health outcome that is related to social, environmental, or economic disadvantage (28); and are stated generally enough to be applicable to as many racial health disparities as possible, where privileged (e.g., White) and marginalized (e.g., Black, American Indian or Alaska Native) racial groups are compared, and as many types of causal diagrams as possible (12, 32, 33). Consistent with prior scholarship (7), in this commentary we largely consider structural racism, institutional racism, and systemic racism to be other labels for racist policies, where a racist policy is any law, custom, practice, rule, process, regulation, guideline, or procedure that a population is governed by that increases or maintains racial inequity. Similarly, we consider structural antiracism, institutional antiracism, and systemic antiracism to be other labels for antiracist policies where an antiracist policy is any law, custom, and so forth that increases or maintains racial equity. We use these definitions to acknowledge that every policy is increasing or maintaining either racial inequity or equity, and policies can increase or maintain inequity or equity regardless of intent (7). Although absolute and relative measures of inequity may diverge (34, 35), prior work (34) examining specific absolute and relative measures indicates that the absolute measure may best reflect progress in reducing inequity, while the relative measure may best reflect progress in eliminating inequity. Despite our result-based definitions of racist and antiracist policies, we recognize that defining such policies based on process (36) may also be beneficial. For brevity we do not use the term systemic henceforth.

Recommendations:

Include a variable that reflects membership in a societally imposed marginalized vs. privileged racial group (4, 7–9, 11, 20, 26, 31, 37–39). Membership in a particular racial group should be caused by historical processes such as historical structural/institutional racism (1–4, 6–9, 26, 40).

Explicitly state that the racial category variable is socially constructed (1–4, 6, 8, 9).

Depict mechanisms of racism as health determinants operating at multiple levels (3–6, 29).

Include both historical and contemporary structural/institutional racism and antiracism, including relevant examples or measures of historical and contemporary forms of structural/institutional racism and antiracism (e.g., Jim Crow laws) (4, 5).

When possible, include downstream biological determinants or variables that have well-established effects on the biological determinants.

The benefits of implementing these recommendations include the following: They avoid “race” being interpreted as a biological variable; they better capture that “race” is socially constructed (1–4, 6–9) and that racial groups reflect a racialized social hierarchy (1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 31, 38); they better show that racism, operating through an unequal relationship (e.g., privileged vs. marginalized) between racially defined social categories, is a root cause of race-related health disparities (1–5, 11); they facilitate appropriate interpretation of findings (3); they are helpful for elucidating mechanisms and identifying effective intervention targets (4–6, 29); they demonstrate that racism still exists and its impact may be addressed through implementing present-day antiracist policies (30); they help to maximize clarity and meet publication standards (3); they reflect the biological consequences of racism (1); and they may be helpful for addressing rather than solely further documenting racial health disparities. More details on each recommendation and the corresponding benefits are provided in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations for Using Causal Diagrams for Studying Racial Health Disparities

| Recommendation No. | Recommendation | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Instead of including an ill-defined variable such as “race” in the causal diagram, include a variable that reflects membership in a societally imposed marginalized vs. privileged racial group (4, 7–9, 11, 20, 26, 31, 37–39). Membership in a particular racial group should be caused by historical processes such as historical structural/institutional racism (1–4, 6–9, 26, 40). | Avoids “race” being interpreted as a biological variable |

| Better captures that “race” is socially constructed in part based on historical processes, such as historically racist policies (e.g., slavery) (1–4, 6–9, 40) that reflect processes of racialization that produced racially defined social categories that are inherently hierarchical (8, 38) and salient with regard to health outcomes, because to be positioned high in a racially defined social hierarchy confers privileges that were not earned, while being positioned low on a racially defined social hierarchy confers penalties that were not earned (8)Better reflects that racism is a root cause of race-related health disparities (3–5)Better reflects that an unequal relationship (e.g., privileged vs. marginalized) between racially defined social categories, rather than race conceived of as an innate and immutable biological characteristic of an individual, has caused racial health disparities (1, 2, 11) but does not preclude genetic ancestry from contributing to observed race-related health disparities, for instance, via historical processes serving as a common cause of racial group and genetic ancestry and genetic ancestry in turn having direct or indirect effects on the health outcome (67, 71).Reflects that racial groups capture a societally imposed hierarchy of privilege (1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 31, 38) but does not preclude racial group from being a marker of other factors (e.g., environmental exposures) (3, 6). However, we urge researchers to proceed with caution when using racial group as a marker in settings where racial group may not be a good proxy (e.g., racial group as a marker for genetic ancestry (67)). When racial group may not be a good proxy, we recommend collecting data on the factor rather than using racial group as a proxy (67, 83). When collecting data on the factor is not feasible, we then suggest: 1) including racial group as a surrogate for the unmeasured factor in the causal diagram (e.g., racial group and genetic ancestry linked via sharing historical processes as a common cause (40, 71)); 2) including the mechanism(s) by which the unmeasured factor is hypothesized to cause the health outcome in the causal diagram (e.g., direct arrow from genetic ancestry to intermediate(s) such as comorbidities to health outcome); and 3) acknowledging the limitations of using racial group as a proxy or surrogate in the context of the particular research question when interpreting study findings (e.g., observed racial health disparity may capture pathways that do and do not involve genetic ancestry when pathways that do not involve genetic ancestry are not blocked or removed) (40).Facilitates appropriate interpretation of findings (3)Helpful for meeting publication standards (3) | ||

| 2. | Explicitly state that the racial category variable in the causal diagram is socially constructed rather than a biological variable (1–4, 6, 8, 9). | Avoids “race” being interpreted as a biological variableBetter captures that “race” is socially constructed in part based on historical processes, such as historically racist policies (e.g., slavery) (1–4, 6–9, 40) that reflect processes of racialization that produced racially defined social categories that are inherently hierarchical (8, 38) and salient with regard to health outcomes, because to be positioned high in a racially defined social hierarchy confers privileges that were not earned while being positioned low on a racially defined social hierarchy confers penalties that were not earned (8)Facilitates appropriate interpretation of findings (3)Helpful for meeting publication standards (3) |

| 3. | Depict mechanisms of racism as health determinants operating at multiple levels in causal diagram (3–6, 29). | Helpful for elucidating mechanisms contributing to racial health disparities, identifying effective intervention targets (4–6, 29), and in turn addressing rather than solely further documenting racial health disparitiesFacilitates appropriate interpretation of findings (3)Helpful for meeting publication standards (3) |

| 4. | Include both historical and contemporary structural/institutional racism and antiracism including relevant examples or measures of historical and contemporary forms of structural/institutional racism and antiracism in causal diagram (e.g., Jim Crow laws and stop and frisk in Figure 1 as well as “employment sector newly or previously covered when the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1966 was enacted” and “state of residence continued an eviction freeze” in Figures 2 and 3) (4, 5). | Maximizes clarityShows that racism still exists and its impact may be addressed via implementing antiracist policies in the present day (30)Helpful for identifying specific antiracist policies and in turn addressing rather than solely further documenting racial health disparities |

| 5. | When possible, include downstream biological determinants of the health outcome or variables that have well-established effects on the biological determinants in the causal diagram, even if excluding such determinants/variables from the causal diagram will not affect the study design or data analysis (e.g., stress in Figure 1 and access to and quality of health care in Figures 2 and 3). Note that the previously mentioned “when possible” has been included in recognition that adhering to this recommendation may result in the causal diagram being difficult to construct or comprehend. | Better reflects that racism can have biological consequences (1)Facilitates appropriate interpretation of findings (3)Helpful for meeting publication standards (3) |

EXAMPLE CAUSAL DIAGRAMS

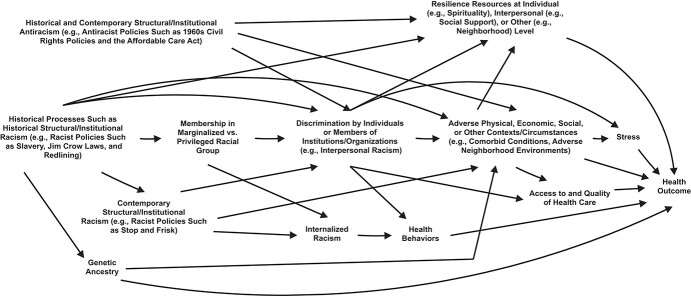

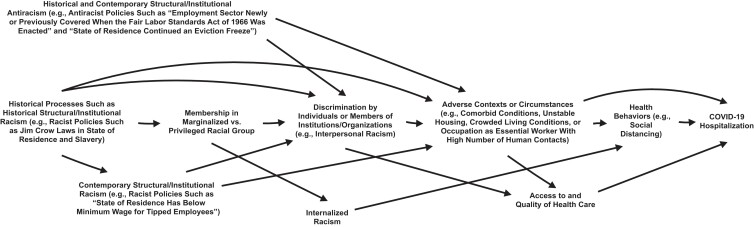

Figure 1 provides an example of a simplified causal diagram that was informed by other relevant work (1–11, 18, 20, 26–31, 38, 40–72), that illustrates how to implement our recommendations, and that can be modified based on the health outcome and hypotheses, or for other group-based differences in health also rooted in privilege and disadvantage (e.g., gender). Figure 2, which was also informed by prior work (4, 5, 7–9, 57–62, 73), demonstrates how Figure 1 can be modified to answer a particular research question (e.g., “what is the hypothetical impact of a specific intervention on racial disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hospitalizations?”). To answer such a question, racial disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations before and after the hypothetical intervention must be quantified (18, 24, 26), and decisions about what to include in the pre-intervention racial health difference must be made (25, 26). However, before elaborating further, we first provide several clarifications.

Figure 1.

Simplified causal diagram for studying racial health disparities. Membership in a marginalized vs. privileged racial group is socially constructed (1–4, 6, 8, 9); a racist policy increases or maintains inequity (e.g., opportunities, health outcomes) between racially defined groups (7); an antiracist policy increases or maintains equity (e.g., opportunities, health outcomes) between racially defined groups (7); and depending on the particular research question, specific antiracist policies may also be considered to be resilience resources. Further, although contemporary structural/institutional racism is depicted as being caused by historical processes such as historical structural/institutional racism, any specific racist policy may or may not have been caused by prior processes or contexts. Last, racial group membership, genetic ancestry, internalized racism, health behaviors, access to and quality of health care, stress, and health outcome are at the individual level; historical and contemporary structural/institutional racism and antiracism, as well as discrimination by individuals or members of institutions/organizations, are at the nonindividual level; and resilience resources as well as adverse physical, economic, social, or other contexts/circumstances can be at the individual or nonindividual level.

Figure 2.

Modified version of Figure 1 that can inform the answer to a particular research question, in this case, the hypothetical impact of a specific intervention on racial disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hospitalizations.

To maximize comprehension, the example causal diagrams were simplified to not include every potentially relevant determinant nor every direct or indirect effect. Moreover, the causal diagrams do not capture that some variables may vary over time (1, 49). The causal diagrams do correspond to causal directed acyclic graphs (12–15, 32). Our example causal diagrams also capture that race-related health disparities are due to historical and contemporary processes that operate at multiple levels and are rooted in structural/institutional racism. To reflect these multilevel processes while still allowing the causal diagram to guide analysis of individual-level data, variables included in a given causal diagram capture exposures that an individual can have through their lived or inherited experiences where the source of these exposures can be at the individual or nonindividual level and these multilevel sources can causally affect each other (64, 65, 74).

For example, in Figure 1, experiencing individual-level membership in a societally imposed marginalized vs. privileged racial group is caused by historical processes. Specifically, nonindividual-level historical structural/institutional racism (e.g., slavery) created racially defined social categories and assigned past generations to be members of these categories, which were based on phenotype and reflected a hierarchy of privilege. Although not explicitly shown in Figure 1 to maximize comprehension, contemporary generations inherited versions of this phenotype-based assignment and privilege hierarchy, which has been further shaped by contemporary contexts (e.g., time and place) (1–4, 6–11). Membership in a marginalized racial group is hypothesized to lead to greater interpersonal exposure to discrimination by individuals or members of institutions/organizations (4, 6, 27, 37, 41, 43, 48, 49) and in turn greater exposure to adverse physical, economic, social, or other nonindividual-level contexts (e.g., adverse neighborhood environments) or individual-level circumstances (e.g., comorbidities) (43) that can affect health outcomes (4–6, 18, 27, 29). Nonindividual-level factors, such as historical and contemporary structural/institutional racism and antiracism, are hypothesized to also have an impact on an individual’s exposure to interpersonal racism and adverse contexts or circumstances due to these nonindividual-level factors causing or preventing the existence or occurrence of interpersonal racism or adverse contexts or circumstances (4, 7, 64) (e.g., historical structural/institutional racism creating adverse neighborhood environments through racist historical policies such as redlining (1–4, 6, 7, 11)). Membership in a marginalized racial group is also hypothesized to lead to experiencing internalized racism that operates at the individual level (e.g., internalizing negative stereotypes about one’s racial group), that in turn may affect individual-level health behaviors and outcomes (6, 27, 51).

Figure 1 also highlights that historical processes such as structural/institutional racism can contribute to observed contemporary associations between racial group membership and health because historical processes are a common cause of racial group and health (1–7, 11, 24, 26, 53, 68–72). For example, historical processes such as Jim Crow laws re-enforced racially defined social categories (69, 70) (e.g., direct arrow from historical processes to racial group) and created or sustained racist practices (e.g., direct arrow from historical processes to discrimination) (4–6), racist beliefs (e.g., direct arrows from historical processes to contemporary structural/institutional racism to internalized racism) (4–7, 11, 53, 72), and adverse circumstances (e.g., direct arrow from historical processes to adverse circumstances such as absence of wealth) (4–6, 68). Observed contemporary associations between racial group and health may have also arisen from historical processes such as Jim Crow laws serving as a common cause of racial group and genetic ancestry via antimiscegenation laws (71).

Note, despite the United States having a single observed history, a given individual’s experience of that history, either directly or indirectly through their familial ancestry, is not inherently uniform, even within the same racial group. For instance, despite the long history of structural/institutional racism in the United States, Jim Crow laws were not uniformly practiced across the United States (65, 75). Therefore, different individuals in the present day may, directly or indirectly through their familial ancestry, have different levels of exposure to Jim Crow laws, including no exposure based on familial ancestry if they are recent immigrants. These different levels of exposure may in turn contribute to different contemporary lived experiences. Variability in lived experiences likely also results from differential experiences of contemporary racist policies (e.g., stop and frisk).

Therefore, the existence of a single US history or the ubiquitous nature of structural/institutional racism (8, 9) does not preclude between-individual variability in experiences of historical processes, such as historical structural/institutional racism, nor does it preclude between-individual variability on measures of historical processes (e.g., born in a state where Jim Crow laws were practiced (75)) in our present-day data sets or preclude these historical processes from contributing to observed present-day racial health disparities. However, given that some historical processes may have little to no observed variability (e.g., history of slavery in Southern states), if between-individual variability is necessary for a given analysis of present-day data, we advocate for operationalizing relevant historical processes using measures that will have variability in present-day data (e.g., born in a state where Jim Crow laws were practiced (75)). When present-day data are analyzed to estimate causal effects, for example of historical or contemporary processes, we also support considering whether variability in the source (e.g., direct or indirect) of a given individual’s experiences of these processes has an impact on estimation (15, 76).

Drawing the recommended causal diagram can also facilitate discussions concerning how specific interventions such as antiracist policies may operate (e.g., via reducing interpersonal racism or removal of arrows that emanate from racial group or another node that is on the pathway from racial group to historical processes to a health outcome (24, 38, 77)). Removal of arrows that specifically emanate from racial group membership, perhaps because of a collection of antiracist policies that results in relevant racist policies being set to absent, would be consistent with Rothman’s sufficient cause model that indicates that some factors (e.g., membership in a marginalized racial group) exert their causal effect only in the presence of other causes (e.g., racist policies) (78, 79). Even if implementing antiracist policies removed the causal effect of racial group, if historical processes remained as a common cause of racial group and a health outcome, racial group membership may still serve as a surrogate effect measure modifier of the relationship between another variable (e.g., health behavior) and the health outcome if historical processes were causal effect measure modifiers of this relationship (15, 80, 81). The potential ability for racial group membership to serve as an effect modifier even in the absence of a causal effect underscores the importance of performing population health research with racially diverse study populations.

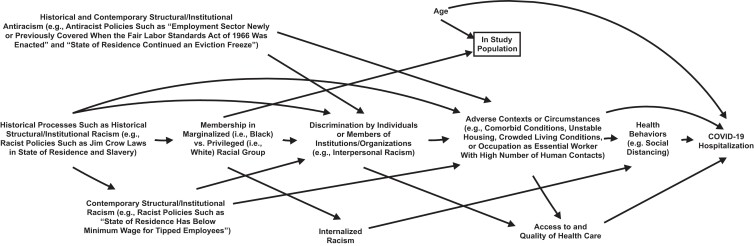

Last, as mentioned earlier, causal diagrams can inform decisions concerning what to include in a pre-intervention racial health difference (25, 26). For example, the recommended causal diagram can help an investigator to determine whether aspects of the study design or analysis are having an impact on an observed racial health difference (25) and whether they want to exclude the study design or analysis contribution from their pre-intervention racial health difference estimate. For example, suppose Figure 3 corresponds to a cohort study aimed at quantifying racial disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations (i.e., Black vs. White), and the investigator oversamples older Black individuals. This oversampling may result in the investigator’s study design having an impact on their estimate of the racial disparity due to racial group and age influencing inclusion in the investigator’s study, age having a direct effect on the outcome, and analyses being restricted to the study population. The investigator would likely want to account (e.g., regression adjustment, inverse probability weighting (15)) for age if they did not want the described oversampling to affect their estimate of the racial disparity, perhaps because the racial disparity in the target population would not include a racial difference due to the oversampling (25).

Figure 3.

Modified version of Figure 2 in which the study design has an impact on observed racial differences in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hospitalizations (i.e., Black vs. White). A box around a node or variable represents conditioning on that node or variable.

CONCLUSIONS

Addressing persistent racial health disparities is critical. Causal diagrams represent a helpful tool for studying population health including racial health disparities (18, 25, 82). However, to maximize the utility of these diagrams, they need to be as accurate as possible. We offer clear recommendations for constructing causal diagrams that may more accurately represent the real world when studying racial health inequities. Although we mentioned earlier that the recommendations are stated generally enough to be applicable to as many racial health disparities as possible, where privileged (e.g., White) and marginalized (e.g., Black, American Indian or Alaska Native) racial groups are compared, we recognize that the specific examples or measures included in a given causal diagram may depend on the particular racial comparison. Further, recommendations offered in this commentary may need to be considerably modified if the goal is to compare groups according to ethnicity rather than racial group. Last, we acknowledge that implementing all of our recommendations may not be necessary for recognizing or minimizing bias. However, implementing them may still facilitate the conduct and publication of more rigorous and informative studies of racial health disparities because they may foster more appropriate interpretation of study findings (3). They may also help epidemiologists to meet publication standards (3) and to more frequently conduct much needed work aimed at addressing racial health disparities instead of solely further documenting these disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Center for Epidemiologic Research, Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, United States (Chanelle J. Howe); Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, United States (Zinzi D. Bailey); Division of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, United States (Zinzi D. Bailey); Department of Health Law, Policy and Management, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, United States (Julia R. Raifman); Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (John W. Jackson); Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (John W. Jackson); Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (John W. Jackson); Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (John W. Jackson); and Johns Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions, Baltimore, Maryland, United States (John W. Jackson).

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant K01MH116817 to J.R.R.), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant K01HL145320 to J.W.J.).

The authors thank Dr. Akilah Dulin for helpful discussions.

Conflict of interest: C.J.H. has received funding unrelated to the current work via a grant from Sanofi administered directly to Brown University.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krieger N, Davey SG. The tale wagged by the DAG: broadening the scope of causal inference and explanation for epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1787–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krieger N, Smith GD. Response: FACEing reality: productive tensions between our epidemiological questions, methods and mission. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1852–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, et al. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/. Accessed January 15, 2021.

- 4. Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones CP. Invited commentary: "race," racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):299–304 discussion 305–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kendi IX. How to Be an Antiracist. New York, NY: One World; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S30–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones CP, Truman BI, Elam-Evans LD, et al. Using "socially assigned race" to probe White advantages in health status. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):496–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krieger N. Epidemiology—Why epidemiologists must reckon with racism. In: Ford CL, Griffith DM, Bruce MA, eds. Racism: Science & Tools for the Public Health Professional. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM, et al. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(2):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference: What If? Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naimi AI, Richardson DB, Cole SR. Causal inference in occupational epidemiology: accounting for the healthy worker effect by using structural nested models. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(12):1681–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adeyeye TE, Yeung EH, McLain AC, et al. Wheeze and food allergies in children born via cesarean delivery: the Upstate KIDS Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(2):355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howe CJ, Dulin-Keita A, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating the population impact on racial/ethnic disparities in HIV in adulthood of intervening on specific targets: a conceptual and methodological framework. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(2):316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howe CJ, Napravnik S, Cole SR, et al. African American race and HIV virological suppression: beyond disparities in clinic attendance. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(12):1484–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fujishiro K, Hajat A, Landsbergis PA, et al. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in all-cause mortality in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA): substantive complexity and hazardous working conditions as mediating factors. SSM - Popul Health. 2017;3:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seamans MJ, Robinson WR, Thorpe RJ Jr, et al. Exploring racial differences in the obesity gender gap. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mayeda ER, Banack HR, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Can survival bias explain the age attenuation of racial inequalities in stroke incidence? A simulation study. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):525–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naimi AI, Kaufman JS, Howe CJ, et al. Mediation considerations: serum potassium and the racial disparity in diabetes risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):614–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jackson JW, VanderWeele TJ. Decomposition analysis to identify intervention targets for reducing disparities. Epidemiology. 2018;29(6):825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howe CJ, Robinson WR. Survival-related selection bias in studies of racial health disparities: the importance of the target population and study design. Epidemiology. 2018;29(4):521–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jackson JW. Meaningful causal decompositions in health equity research: definition, identification, and estimation through a weighting framework. Epidemiology. 2021;32(2):282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sen M, Wasow O. Race as a bundle of sticks: designs that estimate effects of seemingly immutable characteristics. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2016;19(1):499–522. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl2):5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(suppl 1):231–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dover DC, Belon AP. The health equity measurement framework: a comprehensive model to measure social inequities in health. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greenland S. For and against methodologies: some perspectives on recent causal and statistical inference debates. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(1):3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robins JM, Richardson TS. Alternative graphical causal models and the identification of direct effects. In: Shrout P, Keyes K, Ornstein K, eds. Causality and Psychopathology: Finding the Determinants of Disorders and Their Cures. New York, NY: Oxford; 2011:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moonesinghe R, Beckles GL. Measuring health disparities: a comparison of absolute and relative disparities. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harper S, King NB, Meersman SC, et al. Implicit value judgments in the measurement of health inequalities. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1):4–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shiao J, Woody A. The meaning of “racism”. Sociol Perspect. 2021;64(4):495–517. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, et al. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(suppl 2):1374–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riley AR. Advancing the study of health inequality: fundamental causes as systems of exposure. SSM Popul health. 2020;10:100555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. LaVeist TA. On the study of race, racism, and health: a shift from description to explanation. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30(1):217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaufman JS. Commentary: causal inference for social exposures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buchmueller TC, Levy HG. The ACA's impact on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage and access to care. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2020;39(3):395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baciu A, Negussie Y, Geller A, et al., eds. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dulin AJ, Dale SK, Earnshaw VA, et al. Resilience and HIV: a review of the definition and study of resilience. AIDS Care. 2018;30(suppl 5):S6–s17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, et al. Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic whites. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(3):371–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Taylor R, Chatters LM. Importance of religion and spirituality in the lives of African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites. J Negro Educ. 2010;79(3):280–294. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Griffin ML, Amodeo M, Clay C, et al. Racial differences in social support: kin versus friends. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(3):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev. 2004;94(4):991–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34(1):181–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bhatt CB, Beck-Sagué CM. Medicaid expansion and infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):565–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Steele CM. A threat in the air. How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52(6):613–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wildeman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1464–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gelman A, Fagan J, Kiss A. An analysis of the New York City Police Department's “stop-and-frisk” policy in the context of claims of racial bias. J Am Stat Assoc. 2007;102(479):813–823. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dunn C, Shames M. In: Lee D, ed. Stop-and-Frisk in the de Blasio Era. New York, NY: The New York Civil Liberties Union; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sewell AA, Jefferson KA. Collateral damage: the health effects of invasive police encounters in New York City. J Urban Health. 2016;93(Suppl 1):42–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 racial and ethnic health disparities. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/racial-ethnic-disparities/index.html. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 58. Alexander M. Tipping is a legacy of slavery [opinion]. New York Times. February 5, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Derenoncourt E, Montialoux C. Minimum wages and racial inequality. Q J Econ. 2020;136(1):169–228. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bond M. Black Philadelphia renters face eviction at more than twice the rate of white renters. In: The Philadelphia Inquirer. February 4, 2021.

- 61. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities . Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s effects on food, housing, and employment hardships. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- 62. Leifheit KM, Linton SL, Raifman J, et al. Expiring eviction moratoriums and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(12):2503–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Agénor M, Perkins C, Stamoulis C, et al. Developing a database of structural racism-related state laws for health equity research and practice in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(4):428–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fleischer NL, Diez Roux AV. Using directed acyclic graphs to guide analyses of neighbourhood health effects: an introduction. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(9):842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, et al. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(1):37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Fuentes-Afflick E, et al. Race and genetic ancestry in medicine - a time for reckoning with racism. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McIntosh K, Moss E, Nunn R, et al. Examining the Black-White wealth gap. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/. Published February 27, 2020. Accessed July 2, 2021.

- 69. Davis FJ. Who is Black? One nation's definition. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/mixed/onedrop.html. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- 70. Snipp CM, Liebler CA. The end of the “One-Drop” Rule? Hypodescent in the early 21st Century [abstract]. Presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, San Francisco, CA, May 3–5, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chin GJ, Karthikeyan H. Preserving racial identity: population patterns and the application of anti-miscegenation statutes to Asian Americans, 1910–1950. Berkeley Asian Law J. 2002;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hassett-Walker C. How you start is how you finish? The slave patrol and Jim Crow origins of policing. American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/civil-rights-reimagining-policing/how-you-start-is-how-you-finish/. Accessed January 27, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 74. Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Krieger N, Jahn JL, Waterman PD. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: US-born Black and White non-Hispanic women, 1992–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(1):49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. VanderWeele TJ, Hernán MA. Causal inference under multiple versions of treatment. J Causal Inference. 2013;1(1):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. Rejoinder: how to reduce racial disparities? Upon what to intervene? Epidemiology. 2014;25(4):491–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. VanderWeele TJ. Invited commentary: the continuing need for the sufficient cause model today. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(11):1041–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rothman KJ. Causes. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(6):587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. VanderWeele TJ. On the distinction between interaction and effect modification. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. VanderWeele TJ, Robins JM. Four types of effect modification: a classification based on directed acyclic graphs. Epidemiology. 2007;18(5):561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Valeri L, Chen JT, Garcia-Albeniz X, et al. The role of stage at diagnosis in colorectal cancer Black-White survival disparities: a counterfactual causal inference approach. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Oni-Orisan A, Mavura Y, Banda Y, et al. Embracing genetic diversity to improve Black health. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1163–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]