Abstract

Background

healthy dietary patterns have been associated with lower risk for age-related cognitive decline. However, little is known about the specific role of dietary fibre on cognitive decline in older adults.

Objective

this study aimed to examine the association between dietary fibre and cognitive decline in older adults and to assess the influence of genetic, lifestyle and clinical characteristics in this association.

Design and participants

the Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti area study is a cohort study of community-dwelling older adults from Italy. Cognitive function, dietary and clinical data were collected at baseline and years 3, 6, 9 and 15. Our study comprised 848 participants aged ≥ 65 years (56% female) with 2,038 observations.

Main outcome and measures

cognitive decline was defined as a decrease ≥3 units in the Mini-Mental State Examination score during consecutive visits. Hazard ratios for cognitive decline were estimated using time-dependent Cox regression models.

Results

energy-adjusted fibre intake was not associated with cognitive decline during the 15-years follow-up (P > 0.05). However, fibre intake showed a significant interaction with Apolipoprotein E (APOE) haplotype for cognitive decline (P = 0.02). In participants with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype, an increase in 5 g/d of fibre intake was significantly associated with a 30% lower risk for cognitive decline. No association was observed in participants with APOE-ɛ2 and APOE-ɛ3 haplotypes.

Conclusions and relevance

dietary fibre intake was not associated with cognitive decline amongst older adults for 15 years of follow-up. Nonetheless, older subjects with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype may benefit from higher fibre intakes based on the reduced risk for cognitive decline in this high-risk group.

Keywords: fibre, cognitive decline, older adults, cohort study, Apolipoprotein E (APOE), nutrigenetic

Key Points

Dietary fibre intake was not associated with cognitive decline during 15 years in this cohort of 848 older adults from Italy.

Higher intakes of dietary fibre showed a protective effect against cognitive decline only in subjects with Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ɛ4 haplotype.

These results may contribute to personalised dietary fibre recommendations to prevent cognitive decline in older adults.

Introduction

Age-related cognitive decline, considered a precursor of dementia [1], is an important public health concern lacking effective treatments. Thus, identifying modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline is important to develop effective strategies of prevention. Amongst possible prevention strategies, diet quality has been associated with age-related cognitive decline [2]. Dietary patterns characterised by high intake of plant-based foods, such as the Mediterranean diet, have been associated with lower risk for cognitive decline and dementia [3–5]. Despite the positive impact on cognition of healthy dietary patterns characterised by high consumption of food groups rich in fibre, whether there is a specific effect of dietary fibre is unclear.

Dietary fibre refers to plant-derived non-starch polysaccharides, resistant oligosaccharides, lignin and resistant starch that are resistant to human digestive enzymes [6]. National dietary guidelines currently include an optimal dietary fibre intake, which for adults in western countries are in the order of 30–35 g/d for men and 25–32 g/d for women [7]. However, average intakes do not reach this level in any country [8]. Dietary fibre is known to enhance gastrointestinal [9], immune and metabolic health [10, 11], but its influence on cognitive function has not been fully elucidated. Evidence from animal studies using synthetic, extracted or single foods high in fibre shows beneficial effects on cognition [12, 13], but data from human cohorts are still scarce, especially in older adults. In human studies, diets rich in fibre have been associated with better cognitive scores [14–17], whereas the opposite was observed for simple carbohydrates [14, 18, 19]. Vercambre et al. [17] showed an association between higher fibre intake and lower rate of cognitive decline in a French cohort study of older women. Furthermore, a recent study showed an inverse association between dietary fibre and disabling dementia in a long follow-up study in Japanese middle-aged adults [20]. Indeed, dietary fibre intake, together with other nutrients, was associated with measures of improved brain integrity, such as larger total brain volume and lower white matter hyperintensity volume in dementia-free older adults [21]. The impact of dietary fibre on cognitive function might be mediated by its influence on gut microbiota. Dietary fibre intake shapes gut microbiota composition and/or functionality, increasing the output of fermentative end-products, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [22]. These metabolites have shown the potential to modulate brain function via the ‘microbiota-gut-brain’ axis [23].

Our hypothesis was that higher intake of dietary fibre would have a protective effect on cognitive decline in older adults. The main objective was to evaluate the relationship between dietary fibre intake and the incidence of cognitive decline in a prospective study of community-dwelling older adults, the Invecchiare in Chianti, aging in the Chianti area (InCHIANTI) study. In addition, a secondary aim was to assess whether other genetic, lifestyle and clinical factors modulate the effect of dietary fibre intake and the risk of cognitive decline.

Methods

Study design

The InCHIANTI is a prospective study including community-dwelling older adults living in the Chianti geographic area (Tuscany, Italy) [24]. The baseline data were collected in 1998–2000 and three follow-up assessments were conducted every 3 years up to year 9 and then one last assessment by year 15. The Italian National Institute of Research and Care of Aging Institutional Review and Medstar Research Institute (Baltimore, MD, USA) approved the study protocol, and all participants signed an informed consent.

The current report followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Nutritional Epidemiology guidelines [25].

Study population

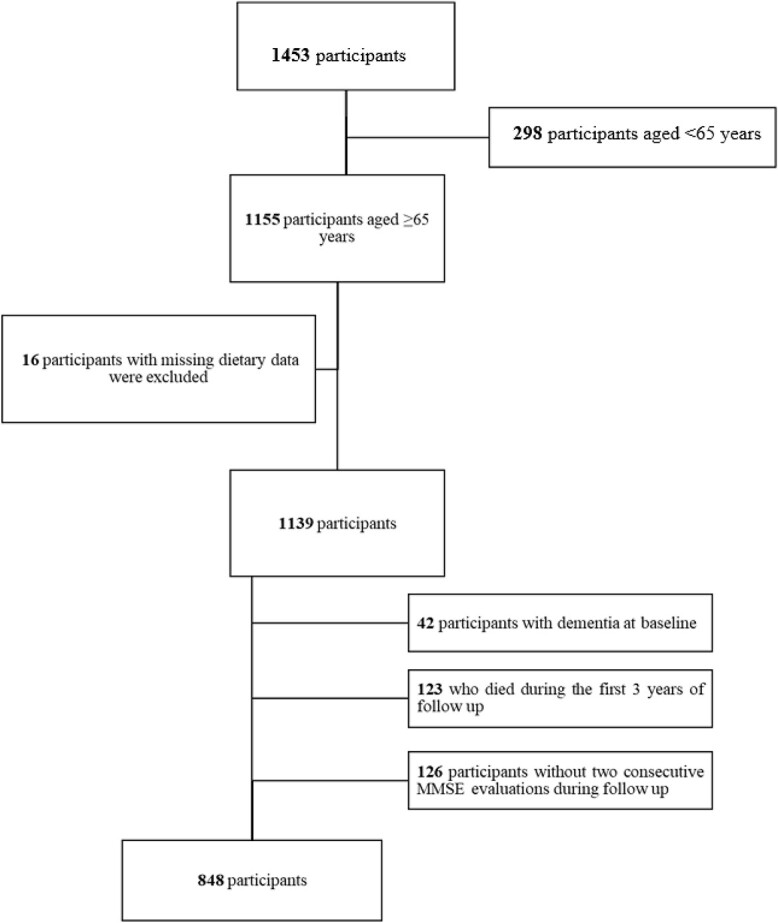

One thousand four hundred and fifty-three community-dwelling adults were randomly selected from the population registries of two Italian communities: Greve in Chianti and Bagno a Ripoli, using a multistage, stratified sampling method. At baseline, 1,155 participants aged ≥ 65 years were evaluated. Sixteen participants were excluded because they had missing data on dietary questionnaires. In addition, we excluded 123 participants who died within the first 3 years of follow-up, 42 participants with dementia at baseline and 126 participants without two consecutive Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) evaluations during the follow-up (Figure 1). In total, the final data set comprised 848 participants and 2,038 observations.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants included in the analysis.

Dietary intake

Habitual dietary intake was assessed by trained interviewers using the Italian version of the food frequency questionnaire developed and validated in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Italy study [26]. This questionnaire asked how often (daily, week and monthly) the consumption of 198 food and beverages items occurred in the past year, considering their respective portion sizes. Nutrient data for specific foods were obtained from the Food Composition Database for Epidemiological Studies in Italy [27]. Fibre content of foods in the Database was measured using a modified version of the AOAC method [27]. For this analysis, dietary data at baseline and during follow-up (at 3, 6 and 9 years) were considered.

Mediterranean diet adherence score

Adherence to Mediterranean diet was computed using a 9-point linear scale described by Trichopoulou et al. [28], that ranged from 0 (no adherence) to 9 (high adherence).

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on existent literature and associations with the outcome of cognitive decline in the InCHIANTI study [17, 29, 30]. Age, sex, years of education and physical activity were assessed through standardised questionnaires. Smoking habits were self-reported, and participants were classified into never, former or current smokers. Height and weight were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated in kg/m2. Depression was assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. Comorbidities and its definitions are detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Apolipoprotein E haplotypes

Overnight fasting blood samples were used for genomic DNA extraction as previously described [31]. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) variant genotypes (e2, e3, e4) were defined by two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rs429358 and rs7412. These two SNPs were genotyped using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Inc. [ABI], Foster City, CA, USA) [32].

Outcome assessment

Global cognitive performance was assessed using the MMSE, and cognitive decline was defined as ≥3 points decline in MMSE between two consecutive follow-up evaluations, according to previous publications [33, 34]. Number of participants, time periods and cognitive decline cases during the follow-up are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Statistical analysis

In 54 participants (6.4%), BMI and renal function at baseline were missing and values were imputed using the baseline median. During the follow-up, missing values in dietary data (k = 79 observations, 4%) were imputed by the Last Observation Carried Forward. Dummy variables were created to identify participants with imputed values at baseline and during the follow-up to be excluded in sensitivity analyses.

Fibre intake was adjusted by energy using the residual method [35]. Energy-adjusted fibre intake (g/d) was categorised into tertiles for the descriptive analysis at baseline. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Differences in baseline characteristics, comorbidities and dietary intake data across tertiles of energy-adjusted fibre intake and between participants according to their APOE haplotype were assessed using generalised linear models (GLM) adjusted for age and sex. We evaluated the differences in energy-adjusted fibre intake during the follow-up using linear mixed models with participants as a random effect. Intra-class correlation coefficients were calculated to assess changes in fibre intake during the follow-up.

Cognitive decline was considered an event because of the skewed distribution of MMSE scores and the non-linear trajectories of MMSE scores over time in older adults [36]. Therefore, Cox regression was used instead of linear mixed models for analyses. Time-to event was defined as the time elapsed from baseline to the one at which cognitive decline was first detected (see Supplementary Figure 1 for details). Three time-dependent Cox models were used for main analyses controlling for potential confounders selected a priori. Model 1 was adjusted for age at baseline (years), sex and total energy intake (kcal/d). Model 2 was further adjusted for BMI, years of education, smoking, alcohol intake (g/d), physical activity and APOE haplotype. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for comorbidities: impaired renal function (IRF), diabetes, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, cancer and cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Restricted cubic splines were used to model non-linear associations between fibre intake and cognitive decline.

Interaction analyses were conducted according to the risk factors for dementia described by the 2020 report of the Lancet Commission on Dementia prevention, intervention and care [37]. Interaction terms between energy-adjusted dietary fibre (as g/d) and sex, smoking, physical activity, alcohol intake, diabetes, hypertension and APOE haplotype in relation to cognitive decline were added to the Cox regression models. Sensitivity analyses are detailed in Supplementary Methods. For the statistical analyses, SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, USA) and R 4.0.5 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria) were used. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

The studied population consisted in 848 participants (56% women) with a mean age of 74 ± 7 years at baseline (Table 1). Amongst comorbidities, the most frequent were hypertension (59% of participants), IRF (33%), depression (33%) and CVD (21%). Mean MMSE was 26 ± 3, and daily total fibre intake was 20 ± 6 g/d.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the population according to tertiles of energy-adjusted dietary fibre intake in the InCHIANTI study.

| Total | Dietary fibre | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 848) | T1 (282) | T2 (283) | T3 (283) | |

| Age (years) | 74 ± 7 | 74 ± 7 | 73 ± 6 | 73 ± 6 |

| Women (%) | 56 | 53 | 57 | 57 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 27 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 | 27 ± 4 | 27 ± 3 |

| Education (years) | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 | 5 ± 3 |

| Current smoking (%) | 27 | 29 | 25 | 27 |

| Physical activity (%) | ||||

| Sedentary | 18 | 22 | 17 | 14 |

| Light | 45 | 40 | 48 | 46 |

| Mod-High | 37 | 38 | 35 | 40 |

| Hypertension (%) | 59 | 57 | 61 | 58 |

| Diabetes (%) | 12 | 7 | 14 | 13* |

| IRF (%) | 33 | 36 | 31 | 31 |

| CVD (%) | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 |

| COPD (%) | 7 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Cancer (%) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 |

| Depression (%) | 33 | 37 | 30 | 31 |

| MMSE (0–30) | 26 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | 25 ± 2 | 25 ± 2 |

| APOE haplotypea (%) ε2 ε3 ε4 |

14 71 15 |

15 16 69 |

12 73 15 |

14 72 14 |

| MDS (0–9) | 4 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 5 ± 1** |

| Dietary characteristics | ||||

| Energy (103 kcal/d) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

| Dietary fibre (g/d) | 20 ± 6 | 15 ± 4 | 18 ± 3 | 24 ± 4** |

| Protein (g/d) | 76 ± 20 | 77 ± 20 | 72 ± 19 | 77 ± 19 |

| Total lipids (g/d) | 62 ± 19 | 62 ± 20 | 57 ± 17 | 64 ± 19 |

| SFA (g/d) | 22 ± 8 | 23 ± 3 | 20 ± 6 | 21 ± 7** |

| MUFA (g/d) | 33 ± 11 | 31 ± 10 | 30 ± 9 | 35 ± 11** |

| PUFA (g/d) | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 7 ± 2* |

| Carbohydrates (g/d) | 242 ± 76 | 241 ± 79 | 231 ± 71 | 253 ± 75 |

| Alcohol (g/d) | 8 (0–27) | 13 (1–32) | 7 (0–19) | 2 (0–13)** |

MDS, Mediterranean diet score. Data for continuous variables are shown as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). Cut-off points for energy-adjusted dietary fibre intake (g/d) were: tertile 1, 7.6–18.5 g/d; tertile 2, 18.5–22.1 g/d; tertile 3, 22.1–45.7 g/d.

Data available for 810 participants.

* P for trend < 0.05, **P for trend < 0.001 using age- and sex-adjusted GLM.

Overall, baseline characteristics across the participants classified according to energy-adjusted fibre intake were similar. Participants with the highest consumption of energy-adjusted dietary fibre had a higher prevalence of diabetes, a higher adherence to Mediterranean diet, a lower alcohol and saturated fatty acid (SFA) intakes, and a higher intake of monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) (Table 1).

Regarding dietary sources of total fibre intake, major contributors were fruit and cereals (43 and 35%, respectively), followed by vegetables (16%), legumes (5%) and nuts (0.4%). During follow-up, energy-adjusted fibre intake remained stable with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.44. Nonetheless, fibre intake decreased during follow-up and differences were only significant between the first and the last dietary evaluation (9-year follow-up) [mean difference (95% CI): −2.7 (−3.1 to −2.2) g/d].

Association between fibre intake and cognitive decline

During follow-up, 549 participants developed cognitive decline. Time-dependent Cox regression models showed that energy-adjusted fibre intake was not associated with cognitive decline for the 15-years follow-up (P > 0.05, Supplementary Table 1). The results remained the same when fibre intake was included in a non-linear model (P > 0.05), as well as in sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 2).

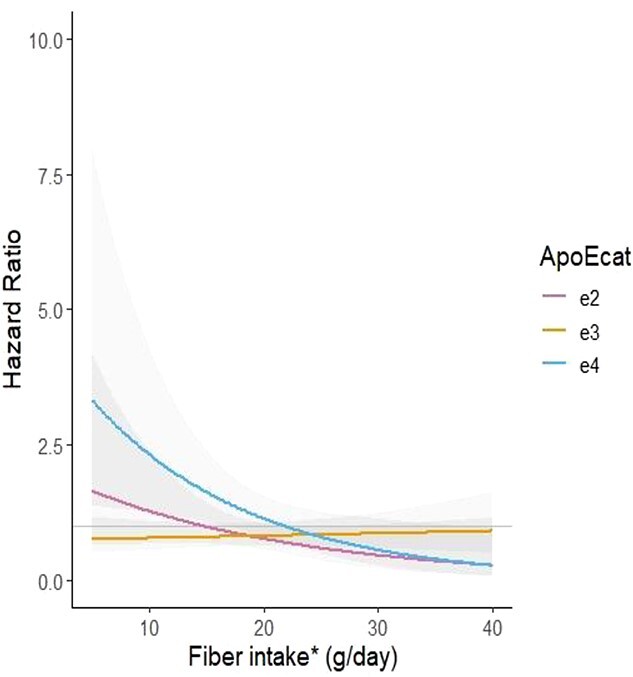

A statistically significant interaction was only observed between APOE haplotype and fibre intake in relation to cognitive decline risk (P for interaction = 0.02, Figure 2). In participants with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype, a higher fibre intake was significantly associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline [HR (95% CI) per 5 g/d of fibre intake: 0.70 (0.52–0.95)]. Conversely, in participants with the APOE-ɛ2 and APOE-ɛ3 haplotypes, this association was not statistically significant [0.77 (0.55–1.08) and 1.04 (0.91–1.19), respectively, for a 5 g/d difference of fibre intake].

Figure 2.

Interaction between APOE haplotype and energy-adjusted fibre intake (g/d) for the association with cognitive decline. Time-dependent Cox regression model, including *energy-adjusted dietary fibre (residual method) adjusted for baseline age, sex, BMI, years of education, smoking, alcohol intake (g/d), physical activity, comorbidities (IRF, diabetes, depression, COPD, hypertension, cancer and CVD) and APOE haplotype. No. of subjects at baseline = 810. No of events = 522. No. of observations = 1,955. Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals.

We compared the participants according their APOE haplotype (n ɛ2 = 110, n ɛ3 = 578, n ɛ4 = 122) to better characterise them. Participants with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype had lower BMI and higher alcohol intake. However, they showed no statistically significant differences in other sociodemographic, clinical or dietary characteristics (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

The current study explored the association between dietary fibre intake and the development of cognitive decline in a cohort of community-dwelling older adults during 15 years of follow-up. Overall, we found that a higher intake of dietary fibre was not significantly associated with a lower risk for cognitive decline. However, a higher intake of dietary fibre showed a protective effect against cognitive decline in subjects with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype, a genetic risk factor extensively associated with an increased risk for impaired cognitive function [38].

Up to date, few studies have assessed the specific association of dietary fibre intake with cognitive function in older adults. A 13-year follow-up study of older French women found higher risk of cognitive decline in participants with lower intake of total and soluble dietary fibre [17]. Similarly, a cross-sectional analysis of the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that higher dietary fibre intake was associated with improved scores in the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, a surrogate marker for some domains of cognitive function, in older adults aged 60 years and older [39]. Randomised controlled trials reviewed by La Torre et al. [40] showed that dose and type of dietary fibre may have differential effects on cognitive function. This could be a possible explanation for our null association in the whole study. Indeed, in an Australian cohort of adults aged 55–65 years habitual consumption of high-fibre breads (but not from fruits and vegetables) was associated with better cognitive function [2]. Further research assessing the potential differential effects on cognitive outcomes depending on the dietary source of fibre is needed in large cohorts. Our results describe for the first time an interaction between fibre intake and APOE haplotype. In participants with APOE-ε4, dietary fibre intake showed a significant protective association with cognitive decline. Up to date, APOE-ε4 haplotype is considered the strongest genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer’s disease and has been recently associated also with poorer cognition and greater risk of dementia at older ages [38, 41]. Increasing evidence points that APOE-ε4 carriers could respond differently to dietary and metabolic treatments [42–44]. Indeed, it has been shown that a high fat diet improved cognition in APOE-ε4 carriers, whereas it worsened Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers for other APOE variants [45]. However, the interaction between APOE-ɛ4 and fibre intake has not been reported before. In the light of the present findings, it is possible that some of this protection could come from different responses elicited by dietary fibre, revealing a nutrigenetic interaction. APOE is involved in lipid transport, cholesterol homeostasis, synaptic plasticity, mitochondrial function and insulin signalling [46]. Thus, APOE gene alleles have been described to change the response to diet at many levels. APOE4 allele has been described to alter the endosomal trafficking of cell surface receptors mediating lipid and glucose metabolism [47], leading to a modulation of the metabolic response to diet in APOE-ε4 carriers [48]. Indeed, previous metabolomic studies have shown that energy metabolism pathways regarding fatty acid oxidation, ketone bodies and glucose utilisation are different in APOE-ɛ4 carriers, in comparison with APOE-ɛ3 homozygotes [49, 50]. Two recent analyses conducted in older adults from the French Three-City Study showed that amongst APOE-ε4 carriers, a diet high in refined carbohydrates and low in fibre was associated with higher long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [51]; and that a high glycemic load diet was associated with cognitive decline [52]. All together, these reports underscore the importance of personalised nutrition based on the APOE-ɛ4 gene variant to reduce the risk for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, as recently suggested [43].

Another potential and complimentary explanation could be related to gut microbiota composition and activity [53–56]. Human and murine evidence have shown a negative association between Ruminococacceae, Prevotellaceae and APOE-ɛ4 status [54, 57, 58]. Interestingly, Ruminococcaceae and Prevotellaceae are bacterial families that metabolise complex polysaccharides into SCFAs [59, 60]. Specifically, a reduced amount of these bacteria has been causally linked to inflammation [61, 62], suggesting that they might contribute to the protective effects of APOE-ɛ2 and -ɛ3 alleles against cognitive decline. This hypothesis is further supported by an increase in Prevotella and other SCFA producing bacteria in asymptomatic, APOE-ɛ4 transgenic mice supplemented with inulin (a type of soluble dietary fibre) [56].

The main strengths of this study are the prospective design and the long follow-up in a well-established cohort of older adults, allowing us to test the influence of clinical, genetic and dietary data. Additionally, we included repeated dietary assessments to reduce bias from measurement errors in dietary questionnaires. Last, we report the association of fibre intake with incident cases of cognitive decline. In the present study, we considered cognitive decline as a longitudinal event, and not as a cognitive outcome. This choice represents an advantage because: (i) cognitive decline trajectories might not be linear in older adults [63], (ii) MMSE scores suffer from ceiling effect leaving clinically significant cases of cognitive decline undetected if using MMSE cut-off scores and (iii) there is a lack of consensus on cut-off values of MMSE scores [64].

Important limitations to this working definition of cognitive decline include the use of a three points difference in consecutive MMSE evaluations to define cognitive decline, and the relatively small sample size. Moreover, the selected population had a mean age of 74 years old; thus, there is a potential for survival bias. Although Cox models were adjusted for age, education and other comorbidities, residual confounding may still remain. Another limitation is that the food database used in the InCHIANTI study did not allow us to differentiate between soluble and insoluble fibre intake. In a recent study, different associations were observed between dietary fibre subtypes and dementia [20]. Last, high levels of dietary fibre may be associated with higher adherence to healthy dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet. In the present study, the additional adjustment for Mediterranean diet did not change the main results (Supplementary Table 2).

In conclusion, our results showed a null association between dietary fibre intake and cognitive decline amongst community-dwelling older adults from a Mediterranean country. Nonetheless, a nutrigenetic interaction between dietary fibre intake and APOE gene variants on the risk for cognitive decline was observed. Higher levels of dietary fibre may reduce the risk for cognitive decline in participants with APOE-ɛ4 haplotype, which genetically determines a higher risk for dementia and impaired cognitive function. Further studies are needed to confirm this distinctive effect of dietary fibre and tailor nutritional recommendations for preventing cognitive decline in older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the study and the staff involved in the InCHIANTI study. T.M., A.U-C. and C.A-L. thank MINECO PID2020-114921RB-C21 and CIBERFES (CB16/10/00269 from ISCIII). C.A-L. also thanks the award ICREA Academia.

Contributor Information

Andrea Unión-Caballero, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable (CIBERFES), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid 28029, Spain.

Tomás Meroño, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable (CIBERFES), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid 28029, Spain.

Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable (CIBERFES), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid 28029, Spain.

Nicole Hidalgo-Liberona, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fragilidad y Envejecimiento Saludable (CIBERFES), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid 28029, Spain.

Montserrat Rabassa, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain.

Stefania Bandinelli, Geriatric Unit, ASL Toscana Centro, Firenze, Italy.

Luigi Ferrucci, Clinical Research Branch, National Institute on Aging (NIH), Baltimore, MD, USA.

Massimiliano Fedecostante, Geriatria, Accettazione geriatrica e Centro di ricerca per l’invecchiamento, IRCCS INRCA, Ancona, Italy.

Raúl Zamora-Ros, Biomarkers and Nutrimetabolomics Laboratory, Departament de Nutrició, Ciències de l’Alimentació i Gastronomia, Xarxa d'Innovació Alimentària (XIA), Nutrition and Food Safety Research Institute (INSA), Facultat de Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Barcelona, Spain; Unit of Nutrition and Cancer, Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO), Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), Barcelona, Spain.

Antonio Cherubini, Geriatria, Accettazione geriatrica e Centro di ricerca per l’invecchiamento, IRCCS INRCA, Ancona, Italy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Aging online.

Data Availability

Access to InCHIANTI study data was granted upon request to coordinators of the study (S.B., L.F. and A.C.). Data are available upon reasonable request through the study website.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

Joint Programming Initiative ‘A Healthy Diet for Healthy Life’ (INTIMIC J PI HDHL) Project ‘AC19/00111’, and CIBERFES funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funded by European Regional Development Fund ‘A way to make Europe’, Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) (PID2020-114921RB-C21). C.A-L. awarded by grant 2017SGR1546 from the Generalitat de Catalunya’s Agency AGAUR and ICREA Academia 2018. T.M. would like to thank the Ayuda IJCI-2017-32534 financed by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

References

- 1. Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline in prodromal Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 2011; 68: 351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Milte CM, Ball K, Crawford D, McNaughton SA. Diet quality and cognitive function in mid-aged and older men and women. BMC Geriatr 2019; 19: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van de Rest O, Berendsen AAM, Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LCPGM. Dietary patterns, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. Adv Nutr 2015; 6: 154–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knight A, Bryan J, Murphy K. Is the Mediterranean diet a feasible approach to preserving cognitive function and reducing risk of dementia for older adults in western countries? New insights and future directions. Ageing Res Rev 2016; 25: 85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao L, Tan L, Wang HF et al. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Neurobiol 2016; 53: 6144–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones JM. CODEX-aligned dietary fiber definitions help to bridge the ‘fiber gap’. Nutr J 2014; 13: 34. 10.1186/1475-2891-13-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA J 2016; 8:1462. 10.2903/J.EFSA.2010.1462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stephen AM, Champ MMJ, Cloran SJ et al. Dietary fibre in Europe: current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutr Res Rev 2017; 30: 149–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gill SK, Rossi M, Bajka B, Whelan K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 18: 101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson JW, Baird P, Davis RH et al. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr Rev 2009; 67: 188–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nirmala Prasadi VP, Joye IJ. Dietary fibre from whole grains and their benefits on metabolic health. Nutrients 2020; 12: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fleming SA, Monaikul S, Patsavas AJ, Waworuntu RV, Berg BM, Dilger RN. Dietary polydextrose and galactooligosaccharide increase exploratory behavior, improve recognition memory, and alter neurochemistry in the young pig. Nutr Neurosci 2019; 22: 499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gronier B, Savignac HM, Di Miceli M et al. Increased cortical neuronal responses to NMDA and improved attentional set-shifting performance in rats following prebiotic (B-GOS®) ingestion. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2018; 28: 211–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berti V, Murray J, Davies M et al. Nutrient patterns and brain biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease in cognitively normal individuals. J Nutr Health Aging 2015; 19: 413–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ding B, Xiao R, Ma W, Zhao L, Bi Y, Zhang Y. The association between macronutrient intake and cognition in individuals aged under 65 in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018; 8: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gopinath B, Flood VM, Kifley A, Louie JCY, Mitchell P. Association between carbohydrate nutrition and successful aging over 10 years. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 71: 1335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vercambre MN, Boutron-Ruault MC, Ritchie K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Berr C. Long-term association of food and nutrient intakes with cognitive and functional decline: a 13-year follow-up study of elderly French women. Br J Nutr 2009; 102: 419–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roberts RO, Roberts LA, Geda YE et al. Relative intake of macronutrients impacts risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 32: 329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li X. Habitual sugar intake and cognitive function among middle-aged and older Puerto Ricans without diabetes. Physiol Behav 2016; 176: 139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamagishi K, Maruyama K, Ikeda A et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of incident disabling dementia: the circulatory risk in communities study. Nutr Neurosci 2022. 10.1080/1028415X.2022.2027592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prinelli F, Fratiglioni L, Kalpouzos G et al. Specific nutrient patterns are associated with higher structural brain integrity in dementia-free older adults. Neuroimage 2019; 199: 281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lattimer JM, Haub MD. Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients 2010; 2: 1266–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cryan JF, O’riordan KJ, Cowan CSM et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev 2019; 99: 1877–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48: 1618–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lachat C, Hawwash D, Ocké MC et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology—Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-NUT): an extension of the STROBE statement. PLoS Med 2016; 13: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pisani P, Faggiano F, Krogh V, Palli D, Vineis P, Berrino F. Relative validity and reproducibility of a food frequency dietary questionnaire for use in the Italian EPIC centres. Int J Epidemiol 1997; 26: 152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salvini S. A food composition database for epidemiological studies in Italy. Cancer Lett 1997; 114: 299–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Barnia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 2003; 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berendsen AAM, Kang JH, Van De Rest O et al. Association of Adherence to a healthy diet with cognitive decline in European and American older adults: a meta-analysis within the CHANCES consortium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2017; 43: 215–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nooyens ACJ, Yildiz B, Hendriks LG et al. Adherence to dietary guidelines and cognitive decline from middle age: the Doetinchem cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2021; 114: 871–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanaka T, Shen J, Abecasis GR et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma polyunsaturated fatty acids in the InCHIANTI study. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000338. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanaka T, Talegawkar SA, Jin Y, Colpo M, Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet protects from cognitive decline in the Invecchiare in Chianti study of aging. Nutrients 2018; 10: 2007. 10.3390/NU10122007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rabassa M, Cherubini A, Zamora-Ros R et al. Low levels of a urinary biomarker of dietary polyphenol are associated with substantial cognitive decline over a 3-year period in older adults: the Invecchiare in Chianti study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 938–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nguyen HT, Black SA, Ray LA, Espino DV, Markides KS. Predictors of decline in MMSE scores among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol Ser A 2002; 57: M181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tomova GD, Arnold KF, Gilthorpe MS, Tennant PWG. Adjustment for energy intake in nutritional research: a causal inference perspective. Am J Clin Nutr 2022; 115: 189–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Letenneur L, Proust-Lima C, Le Gouge A, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Flavonoid intake and cognitive decline over a 10-year period. 10.1093/aje/kwm036. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020; 396: 413–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6/ATTACHMENT/CEE43A30-904B-4A45-A4E5-AFE48804398D/MMC1.PDF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gharbi-Meliani A, Dugravot A, Sabia S et al. The association of APOE ε4 with cognitive function over the adult life course and incidence of dementia: 20 years follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2021; 13: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prokopidis K, Giannos P, Ispoglou T, Witard OC, Isanejad M. Dietary fiber intake is associated with cognitive function in older adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Med 2022; 135: e257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. La TD, Verbeke K, Dalile B. Dietary fibre and the gut–brain axis: microbiota-dependent and independent mechanisms of action. Gut Microbiome 2021; 2: e3. 10.1017/GMB.2021.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stringa N, van Schoor NM, Milaneschi Y et al. Physical activity as moderator of the association between APOE and cognitive decline in older adults: results from three longitudinal cohort studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020; 75: 1880–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seo JY, Youn BJ, Cheong HS, Shin HD. Association of APOE genotype with lipid profiles and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Korean population. Genes Genomics 2021; 43: 725–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Norwitz NG, Saif N, Ariza IE, Isaacson RS. Precision nutrition for Alzheimer’s prevention in ApoE4 carriers. Nutrients 2021; 13. 10.3390/NU13041362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fallaize R, Celis-Morales C, MacReady AL et al. The effect of the Apolipoprotein E genotype on response to personalized dietary advice intervention: findings from the Food4Me randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 104: 827–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hanson AJ, Bayer JL, Baker LD et al. Differential effects of meal challenges on cognition, metabolism, and biomarkers for Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 carriers and adults with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2015; 48: 205–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Safieh M, Korczyn AD, Michaelson DM. ApoE4: an emerging therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Med 2019; 17: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yassine HN, Finch CE. APOE alleles and diet in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 150. 10.3389/FNAGI.2020.00150/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu L, Zhang X, Zhao L. Human ApoE isoforms differentially modulate brain glucose and ketone body metabolism: implications for Alzheimer’s disease risk reduction and early intervention. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 6665–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. González-Domínguez R, Castellano-Escuder P, Lefèvre-Arbogast S et al. Apolipoprotein E and sex modulate fatty acid metabolism in a prospective observational study of cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res Ther 2022; 14: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arnold M, Nho K, Kueider-Paisley A et al. Sex and APOE ε4 genotype modify the Alzheimer’s disease serum metabolome. Nat Commun 2020; 11. 10.1038/S41467-020-14959-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gentreau M, Chuy V, Féart C et al. Refined carbohydrate-rich diet is associated with long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele carriers. Alzheimers Dement 2020; 16: 1043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gentreau M, Raymond M, Chuy V et al. High Glycemic load is associated with cognitive decline in Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele carriers. Nutrients 2020; 12: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parikh IJ, Estus JL, Zajac DJ et al. Murine gut microbiome association with APOE alleles. Front Immunol 2020; 11. 10.3389/FIMMU.2020.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zajac DJ, Green SJ, Johnson LA, Estus S. APOE genetics influence murine gut microbiome. Sci Rep 2022; 12. 10.1038/S41598-022-05763-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zheng J, Zheng SJ, Cai WJ, Yu L, Yuan BF, Feng YQ. Stable isotope labeling combined with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for comprehensive analysis of short-chain fatty acids. Anal Chim Acta 2019; 1070: 51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hoffman JD, Yanckello LM, Chlipala G et al. Dietary inulin alters the gut microbiome, enhances systemic metabolism and reduces neuroinflammation in an APOE4 mouse model. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0221828. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0221828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tran TTT, Corsini S, Kellingray L et al. APOE genotype influences the gut microbiome structure and function in humans and mice: relevance for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J 2019; 33: 8221. 10.1096/FJ.201900071R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maldonado Weng J, Parikh I, Naqib A et al. Synergistic effects of APOE and sex on the gut microbiome of young EFAD transgenic mice. Mol Neurodegener 2019; 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. La Reau AJ, Suen G. The Ruminococci: key symbionts of the gut ecosystem. J Microbiol 2018; 56: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Precup G, Vodnar DC. Gut Prevotella as a possible biomarker of diet and its eubiotic versus dysbiotic roles: a comprehensive literature review. Br J Nutr 2019; 122: 131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Venegas DP, De La Fuente MK, Landskron G et al. Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 277. 10.3389/FIMMU.2019.00277/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen T, Long W, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao L, Hamaker BR. Fiber-utilizing capacity varies in Prevotella- versus Bacteroides-dominated gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2017; 7. 10.1038/S41598-017-02995-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Sensitivity of four psychometric tests to measure cognitive changes in brain aging-population-based studies. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 344–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pinto TCC, Machado L, Bulgacov TM et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr 2019; 31: 491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Access to InCHIANTI study data was granted upon request to coordinators of the study (S.B., L.F. and A.C.). Data are available upon reasonable request through the study website.