Abstract

Natural strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are prototrophic homothallic yeasts that sporulate poorly, are often heterozygous, and may be aneuploid. This genomic constitution may confer selective advantages in some environments. Different mechanisms of recombination, such as meiosis or mitotic rearrangement of chromosomes, have been proposed for wine strains. We studied the stability of the URA3 locus of a URA3/ura3 wine yeast in consecutive grape must fermentations. ura3/ura3 homozygotes were detected at a rate of 1 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5 per generation, and mitotic rearrangements for chromosomes VIII and XII appeared after 30 mitotic divisions. We used the karyotype as a meiotic marker and determined that sporulation was not involved in this process. Thus, we propose a hypothesis for the genome changes in wine yeasts during vinification. This putative mechanism involves mitotic recombination between homologous sequences and does not necessarily imply meiosis.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeast strains have been selected for (i) their ability to quickly and efficiently ferment grape musts with elevated sugar concentrations, (ii) their resistance to high ethanol and sulfur dioxide concentrations, and (iii) their survival during fermentation at elevated temperatures (17). Thus, wine yeasts have unique genetic and physiological characteristics that differentiate them from other laboratory and industrial strains, such as baker's, brewer's, and distiller's yeasts.

Natural yeasts are mostly prototrophic, homothallic, and heterozygous (4, 15, 17). They sporulate poorly (3), although in the case of wine yeasts, between 0 and 75% of cells sporulate, depending on the ploidy of the strain (4). In wine yeasts, spore viability also varies greatly (0 to 98%) (4) and is inversely correlated with heterozygosity (23). Wine yeasts frequently are aneuploid, with disomies, trisomies, and, less frequently, tetrasomies (3, 15). In some cases, these strains are nearly diploid or triploid. This aneuploidy may confer selective advantages by increasing the number of copies of beneficial genes or by protecting the yeast against lethal or deleterious mutations (3, 15). The electrophoretic karyotypes of wine yeast strains differ in the number, size, and intensity of bands, allowing the identification of every strain by its chromosome pattern (37, 40). Wine strains do not have a stable and defined karyotype, like flor yeasts (21), but their variability is not as high as that reported for baker's yeasts (5, 10).

Chromosomal rearrangements have been described in wine yeast genomes during vegetative growth, due to recombination between homologous chromosomes (19) and to recombination between repeated or paralogous sequences (24, 39). The maintenance of these polymorphisms in a population suggests that such exchanges might be the result of an important adaptive mechanism of yeasts (1, 19).

Mortimer and coworkers (23) proposed a mechanism of evolution for natural wine yeast strains, termed genome renewal. This hypothesis maintains that wine yeasts, which accumulate deleterious mutations as heterozygotes, can sporulate and, as homothallics, produce completely homozygous diploids. Some of these new homozygotes would replace the original heterozygote. However, sexual isolation in yeast populations during wine production (34), the high level of heterozygosity, and the low sporulation rates of wine yeasts (3, 4, 15) do not favor this hypothesis.

Our objective in this study was to test the genome renewal hypothesis (23). We analyzed the formation of homozygotes from a URA3/ura3 heterozygous wine strain during consecutive wine fermentations. The chromosomal heteromorphism of this strain allowed us to determine if the formation of the homozygotes occurred as a consequence of sporulation. Chromosomal rearrangements during vinifications also were studied. We hypothesize that the mechanism of genome evolution for wine yeasts involves only mitotic recombinations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

We used the diploid, homothallic S. cerevisiae wine yeast strain T73 (Spanish Type Culture Collection reference no. CECT1894) selected in the region of Alicante, Spain (29), and commercialized by Lallemand Inc. (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). A recombinant T73 strain, named T73-6, was obtained by transformation with an NdeI-StuI fragment of plasmid pURA::KMX4, that contains the kan gene conferring resistance to the antibiotic G418 (28). T73-6 has one allele of the URA3 gene disrupted by the insertion of the kanMX4 marker (38) and the wild-type allele on the homologous chromosome. It is phenotypically Ura+ and Kanr, and it will be either Ura−/Kanr or Ura+/Kans if it becomes homozygous.

For laboratory cultures, yeast cells were grown at 30°C in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% bacteriological peptone, 2% glucose) or in SD (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 2% glucose). For Ura− screening, 107 cells were spread on a plate of 5-fluoro-orotic acid (FOA) medium [SD without (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% proline, 10 mg of uracil per liter (22) containing 1 mg of FOA (Toronto Research Chemicals, Ontario, Canada) per ml].

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for the construction of plasmids. It was grown at 37°C in LBA medium (1% tryptone, 1% NaCl, 0.5% yeast extract, 50 mg of ampicillin per ml). Media were solidified with 2% agar.

DNA manipulations.

Standard protocols were followed (33).

Yeast transformation protocol.

Wine yeast strain T73 was transformed using lithium acetate to permeabilize the cells (13), and transformants were selected by their resistance to the antibiotic G418 sulfate (Geneticin; GIBCO-BRL, Rockville, Md.) (28, 38).

Sporulation and tetrad analysis.

Sporulation was induced (12), and asci were dissected with a micromanipulator (35), as previously described.

Microvinification experiments.

Four consecutive microvinifications with strain T73-6 were performed at 22°C, using 1 liter of red grape Bobal must (27). The initial yeast inoculum was 2.5 × 105 cells/ml from overnight cultures. At the end of each fermentation, wine was removed and residual yeast cells were maintained for 2 weeks in the original bottles at 22°C until fresh grape must, sterilized with dimethyl dicarbonate (Velcorin; Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), was added. Thus, material from the previous fermentation was used as inoculum for the next one. This procedure simulates the seasonal rebreeding that occurs in wine cellars. During each microvinification, samples of cells were spread on YPD and FOA plates, to determine the total number of viable and Ura− homozygous cells, respectively. We used reducing sugar concentration to indicate fermentation progress.

Chromosomal DNA preparations and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Karyotypes were determined by the contour-clamped homogeneous electric field electrophoresis (CHEF) technique with a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Chromosomal DNA was prepared in agarose plugs (7) and washed three times in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) at 50°C for 30 min and then twice in the same buffer at room temperature for 30 min. Plugs were loaded into 1% agarose gels in 0.5× TBE buffer (44.5 mM Tris-borate, 1.25 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]); migration was at 14°C and 6 V/cm for 13 h with 60 s between field changes, and then 9 h with 90 s between field changes.

Southern blot analysis.

The chromosomal DNA separated by CHEF gel electrophoresis was transferred to nylon filters (Hybond-N; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) as suggested by the manufacturer. Karyotype filters were hybridized with 32P-labeled probes corresponding to rDNA (chromosome XII), HSP42 (chromosome IV), CAR1 (chromosome XVI), YML128w (chromosome XIII), URA3 (chromosome V), CUP1 (chromosome VIII, right arm), and SNF6 (chromosome VIII, left arm) (33).

RESULTS

Characterization of T73 wine yeast strain.

Strain T73 is approximately diploid, homothallic, and prototrophic for most common requirements (data not shown). Sixty percent of T73 cells sporulated, and spore viability was 70% (168 out of 240). Most of the tetrads analyzed had two or three viable spores. The colony sizes (diameters) of the meiotic derivatives varied widely (between one- and fourfold), suggesting that this strain is highly heterozygous.

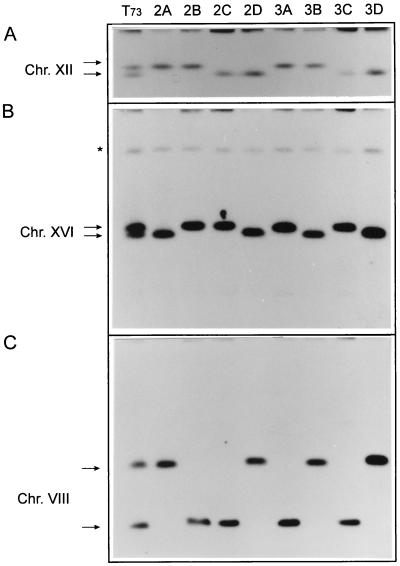

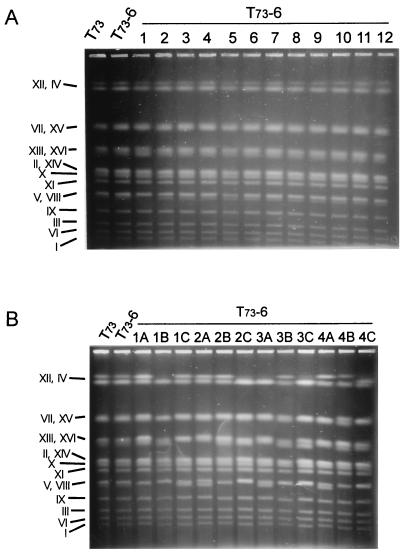

The CHEF gel karyotype of T73 has 14 different bands (Fig. 1), some of which have a lower intensity, suggesting aneuploidy or the presence of homologous chromosomes of different sizes. We used two tetrads, each with four viable spores, to analyze the karyotype following meiosis (Fig. 1). Small differences were detected for chromosomes XIII and I (data not shown). More extensive changes were observed for chromosomes XII, XVI, and VIII, which are represented by two bands of different sizes that segregate 2:2 in these tetrads (Fig. 2). To demonstrate that chromosome VIII was dimorphic, with the usual band of 580 kb and a second of approximately 1,000 kb, we hybridized with probes from both arms of the chromosome with the same result. Thus, we conclude that T73 has at least five pairs of heteromorphic chromosomes.

FIG. 1.

Electrophoretic karyotypes of wine yeast strain T73 and two complete meiotic derivatives (2A to 2D; 3A to 3D). Putative chromosomes corresponding to every band according to the pattern obtained for laboratory strain S288c are indicated.

FIG. 2.

Hybridization of the karyotype of T73 and its meiotic derivatives (Fig. 1) with probes from chromosomes (Chr.) XII (rDNA; A), XVI (CAR1; B), and VIII (CUP1; C). In the case of chromosome VIII, the same result was obtained by using CUP1 (right arm) and SNF6 (left arm) probes (not shown). Arrows indicate significant bands. Asterisk shows cross-hybridization with an unidentified target.

Genetic changes during consecutive wine fermentations.

Homozygous Ura− cells were generated from the URA3/ura3 heterozygote T73-6 during consecutive microvinifications (Table 1). The relative frequency of Ura− cells increases with each microvinification. A reduction in residual cells occurred between the end of one microvinification and the beginning of the following (Table 1). This fact could be explained by the lower viability of Ura− cells than of Ura+ cells in these conditions.

TABLE 1.

Determination of the formation rate of Ura− strains during four consecutive microvinifications with T73-6 straina

| Days of fermentation | Reducing sugars (g/liter) | Total viable cells/ml (T) | Ura− cells/ml (U) | No. of generations (n) | U rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st vinification | |||||

| 0 | 160 | 2.5 × 105 | 1.3 | 0 | |

| 2 | 140 | 4.9 × 107 | 840 | 7.6 | 0.2 × 10−5 |

| 15 | 3.5 | 2.0 × 108 | 1.5 × 104 | 9.6 | 0.7 × 10−5 |

| 2nd vinification | |||||

| 0 | 170 | 3.3 × 106 | 16 | 0 | |

| 3 | 150 | 4.5 × 107 | 5,500 | 3.8 | 3.1 × 10−5 |

| 11 | 54 | 7.2 × 108 | 1.4 × 105 | 7.8 | 2.4 × 10−5 |

| 17 | 4.4 | 1.9 × 108 | 3.6 × 104 | ||

| 3rd vinification | |||||

| 0 | 160 | 4.5 × 105 | 3.9 | 0 | |

| 2 | 150 | 3.7 × 106 | 170 | 3.0 | 1.2 × 10−5 |

| 13 | 42 | 6.4 × 107 | 1.2 × 104 | 7.2 | 2.5 × 10−5 |

| 21 | 3 | 4.1 × 107 | 6,400 | ||

| 4th vinification | |||||

| 0 | 160 | 9.0 × 105 | 16 | 0 | |

| 2 | 130 | 2.4 × 107 | 2,500 | 4.7 | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| 7 | 51 | 5.2 × 107 | 7,800 | 5.9 | 2.3 × 10−5 |

| 15 | 1.4 | 5.0 × 107 | 4,600 |

The number of cell generations during the first fermentation was higher than in the second one, due to a lower inoculum. The cell densities reached in the third and fourth fermentations were lower because of the addition of SO2. To calculate the U rate (rate of Ura− formation per generation), we applied the following equation: U rate = 1 − n√[(1 − qn)/(1 − q0)], where q = U/T. This expression can be simplified to (qn − q0)/n in the case of q→0.

We estimate that Ura− cells appear at a rate of 1 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5 cells per generation (Table 1). This result was lower in the first fermentation. In our calculations, we assume that the growth rate (fitness) is the same for both heterozygous and homozygous cells in this medium. Preliminary results from competition experiments between these strains indicate that Ura− cells have a lower fitness than the heterozygotes. Thus, we underestimate the rate of Ura− cell formation.

Ura− cells could arise by different molecular mechanisms, which would give genetically different strain patterns. We analyzed the URA3 loci of 48 Ura− strains (12 from each microvinification) and found that all were ura3::kanMX4/ura3::kanMX4 (Fig. 3; only one example shown). We determined the electrophoretic karyotypes of the 12 Ura− strains from the last microvinification, apparently obtaining the same pattern than T73-6 (Fig. 4A). However, two of these strains carried cryptic chromosome rearrangements that could be detected only when hybridized to chromosome specific probes (Fig. 5). These changes involved chromosomes VIII (strain 1) and XII (strain 11). On the other hand, every strain obtained by sporulation has a different electrophoretic karyotype (Fig. 4B), due to segregation of nonidentical sister chromosomes. From these data, we conclude that Ura− strains were not produced by sporulation and subsequent mother-daughter conjugation. The lack of sporulation during vinification was confirmed by the absence of spores after staining with green malachite (frequency of ≤10−5) (18). These data support the hypothesis that mitotic gene conversion or recombination resulted in the Ura− strains, but not that these strains arose by sporulation or mutation, events with frequencies between 10−8 and 10−9 in S. cerevisiae (20).

FIG. 3.

(A) Southern analysis of the URA3 locus. DNA from T73, T73-6, and one Ura− strain were digested with HindIII (H), and separated by electrophoresis in a 1.2% agarose gel. The gel was transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized with a HindIII URA3 probe of 1,170 bp. Three different bands can be obtained: the wild-type locus produces a 1,170-bp band, and integration of kanr in the URA3 locus produces two bands of 1,640 and 920 bp (B).

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic karyotype of 12 Ura− strains that appeared during the consecutive fermentations (A) and 12 meiotic derivatives of T73-6 from four different tetrads with three viable spores (B).

FIG. 5.

Hybridization of 12 Ura− strains karyotype (Fig. 4A) with rDNA (Chr. [chromosome] XII) and CUP1 (Chr. VIII) probes. Asterisks indicate cross-hybridization with undetermined targets.

DISCUSSION

Chromosomal features of wine yeast T73.

S. cerevisiae industrial yeasts commonly are aneuploid (3, 15). In wine yeasts, strains with approximately diploid DNA contents, such as T73, are well known (11, 15, 21, 24). This result does not imply that such strains are strictly diploid. Indeed, preliminary results with the strain T73 suggest that chromosome IV may be aneuploid (J. V. Gimeno-Alcañiz and E. Matallana, personal communication). Other wine strains are near diploid or triploid (3, 15). The tolerance of wine yeasts to these DNA levels suggests that meiosis is not a common occurrence in their life cycles (3).

Strain T73 carries several homologous chromosomes of different sizes. Thus, this strain possesses two chromosomes XII of unequal size, probably due to differences in the number of rDNA repeats (Fig. 2A, lane 1), as has been demonstrated for other strains (9, 24, 25, 31, 32). T73 also has two different-sized homologues of chromosome VIII. The longer version of chromosome VIII has been observed in other wine strains (6, 14, 19). Goto-Yamamoto and coworkers (14) have demonstrated recombination between chromosomes VIII and XVI located at the promoter of SSU1, a gene coding for a plasma membrane protein. The longer version of chromosome VIII in T73 could be explained by the presence of this reorganization. Rearrangements of chromosomes XII and VIII during vegetative growth also were observed (Fig. 5), suggesting that they may carry hot spots for mitotic crossing over.

Mechanisms of genetic change in wine yeasts during fermentation.

Mechanisms proposed for genomic evolution of wine yeasts include (i) chromosomal length polymorphisms, (ii) aneuploidy, and (iii) genome renewal in which meiosis is followed by diploidization and competition of the resulting completely homozygous strains (5, 6, 11, 19, 23).

The frequency of meiotic gene conversion for the URA3 locus is approximately 2% (36), with mitotic gene conversion being 3 to 4 orders of magnitude lower (26). We estimate the formation of ura3::kanMX4/ura3::kanMX4 homozygotes at a rate of 1 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5 per generation during successive microvinifications, but we have no evidence for meiosis or sporulation. Therefore, we interpret these data to mean that mitotic gene conversion or mitotic crossing over is the most likely mechanism for their formation.

We propose a process of gradual adaptation to vinification conditions, as chromosomal rearrangements and aneuploidies acquired following numerous mitotic divisions are maintained vegetatively. Mitotic recombination at a frequency of 1 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−5, instead of sporulation, could eliminate the deleterious mutations. With a mechanism such as genome renewal, a sporulation event leads to complete homozygosity of homothallic strains, and hence a loss of polymorphisms and aneuploidies, which we did not observe. This reasoning does not mean that wine strains never sporulate, but it does suggest that sporulation is not significant with respect to their genome evolution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tahía Benítez, Benjamín Piña, Emilia Matallana, and Daniel Ramón for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, and we thank P. Philippsen for providing kanMX plasmids.

This work was supported by grants ALI95-0566 and ALI98-1041 (to J.E.P.-O.) from Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología of the Spanish Government. S.P. was a recipient of an FPI fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J, Puskas-Rozca S, Simlar J, Wilke C M. Adaptation and major chromosomal changes in populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol. 1992;22:13–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00351736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilera A, Klein H. Chromosome aberrations in simpler eukaryotes. In: Kirsch I R, editor. The causes and consequences of chromosomal aberrations. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 51–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakalinsky A T, Snow R. The chromosomal constitution of wine strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1990;6:367–382. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barre P, Vezinhet F, Dequin S, Blondin B. Genetic improvement of wine yeasts. In: Fleet G R, editor. Wine microbiology and biotechnology. Newark, N.J: Harwood Academic Publisher; 1993. pp. 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benítez T, Martínez P, Codón A C. Genetic constitution of industrial yeast. Microbiología. 1996;12:371–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidenne C, Blondin B, Dequin S, Vezinhet F. Analysis of the chromosomal DNA polymorphism of wine strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1992;22:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00351734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carle G F, Olson M V. An electrophoretic karyotype for yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3756–3760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casaregola S, Nguyen V H, Lepingle A, Brignon P, Gendre F, Gaillardin C. A family of laboratory strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae carry rearrangements involving chromosomes I and III. Yeast. 1998;14:551–564. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980430)14:6<551::AID-YEA260>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chindamporn A, Iwaguchi S I, Nakagawa Y, Homma M, Tanaka K. Clonal size-variation of rDNA cluster region on chromosome XII of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1409–1415. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Codón A C, Benítez T, Korhola M. Chromosomal reorganization during meiosis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae baker's yeast. Curr Genet. 1997;32:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s002940050274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Codón A C, Benítez T, Korhola M. Chromosomal polymorphism and adaptation to specific industrial environments of Saccharomyces strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;11:154–163. doi: 10.1007/s002530051152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Codón A C, Gasent-Ramírez J M, Benítez T. Factors which affect the frequency of sporulation and tetrad formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae baker's yeasts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:630–638. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.630-638.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H, Willems A R, Woods R A. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto-Yamamoto N, Kitano K, Shiki K, Yoshida Y, Suzuki T, Iwata T, Yamane Y, Hara S. SSU1-R, a sulfite resistance gene of wine yeast, is an allele of SSU1 with a different upstream sequence. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;86:427–433. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guijo S, Mauricio J C, Salmon J M, Ortega J M. Determination of the relative ploidy in different Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used for fermentation and flor film ageing of dry sherry-type wines. Yeast. 1997;13:101–117. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199702)13:2<101::AID-YEA66>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibeas J I, Jiménez J. Genomic complexity and chromosomal rearrangements in wine-laboratory yeasts hybrids. Curr Genet. 1996;30:410–416. doi: 10.1007/s002940050150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunkee R E, Bisson L F. Wine-making yeasts. In: Rose A H, Harrison J S, editors. The yeasts: yeast technology. London, England: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 69–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurtzman C P, Fell J W. The yeasts: a taxonomic study. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science; 1998. pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longo E, Vezinhet F. Chromosomal rearrangements during vegetative growth of a wild strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:322–326. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.322-326.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magni G E, von Borstel R C. Different rates of spontaneous mutation during mitosis and meiosis in yeast. Genetics. 1962;46:1097–1108. doi: 10.1093/genetics/47.8.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez P, Codón A C, Pérez L, Benítez T. Physiological and molecular characterization of flor yeasts: polymorphism of flor yeast populations. Yeast. 1995;11:1399–1411. doi: 10.1002/yea.320111408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCusker J H, Davis R W. The use of proline as a nitrogen source causes hypersensitivity to, and allows more economical use of 5FOA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1991;7:607–608. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortimer R K, Romano P, Suzzi G, Polsinelli P. Genome renewal: a new phenomenon revealed from a genetic study of 43 strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae derived from natural fermentation of grape musts. Yeast. 1994;10:1543–1552. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadal D, Carro D, Fernández-Larrea J, Piña B. Analysis and dynamics of the chromosomal complements of wild sparkling-wine yeast strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1688–1695. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1688-1695.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasero P, Marilley M. Size variation of rDNA clusters in the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:448–452. doi: 10.1007/BF00277147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petes T D, Malone R E, Symington L S. Recombination in yeast. In: Broach J R, Pringle J R, Jones E W, editors. The molecular and cellular biology of the yeast Saccharomyces. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: CSHL Press; 1991. pp. 407–521. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puig S, Querol A, Ramón D, Pérez-Ortín J E. Evaluation of the use of phase-specific gene promoters for the expression of enological enzymes in an industrial wine yeast strain. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:887–892. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puig S, Ramón D, Perez-Ortin J E. Optimized method to obtain stable food-safe recombinant wine yeast strains. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:1689–1693. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Querol A, Huerta T, Barrio E, Ramon D. Dry yeast strain for use in fermentation of Alicante wines: selection and DNA patterns. J Food Sci. 1992;57:183–185. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachidi N, Barre P, Blondin B. Multiple Ty-mediated chromosomal translocations lead to karyotype changes in a wine strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:841–850. doi: 10.1007/s004380050028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rustchenko E P, Curran T M, Sherman F. Variations in the number of ribosomal DNA units in morphological mutants and normal strains of Candida albicans and in normal strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7189–7199. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7189-7199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rustchenko E P, Sherman F. Physical constitution of ribosomal genes in common strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1157–1171. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: CSHL Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sancho E D, Hernández E, Rodríguez-Navarro A. Presumed sexual isolation in yeast populations during production of sherrylike wine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:395–397. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.2.395-397.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherman F, Hicks J. Micromanipulation and dissection of asci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:21–37. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Symington L S, Petes T D. Meiotic recombination within the centromere of a yeast chromosome. Cell. 1988;52:237. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vezinhet F, Blondin B, Hallet J N. Chromosomal DNA patterns and mitochondrial DNA polymorphism as tools for identification of enological strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;32:568–571. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfe K H, Shields D C. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387:708–713. doi: 10.1038/42711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto N, Amemiya H, Tokomori Y, Shimizu K, Totsuka A. Electrophoretic karyotypes of wine yeasts. Am J Enol Viticult. 1991;42:358–363. [Google Scholar]