Background:

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is a common cause of morbidity and premature mortality. To date, there has been no systematic synthesis of the prevalence of ALD. This systematic review was done with the aim of reporting the prevalence of ALD across different health care settings.

Methods:

PubMed and EMBASE were searched for studies reporting the prevalence of ALD in populations subjected to a universal testing process. Single-proportion meta-analysis was performed to estimate the prevalence of all ALD, alcohol-associated fatty liver, and alcohol-associated cirrhosis, in unselected populations, primary care, and among patients with alcohol-use disorder (AUD).

Results:

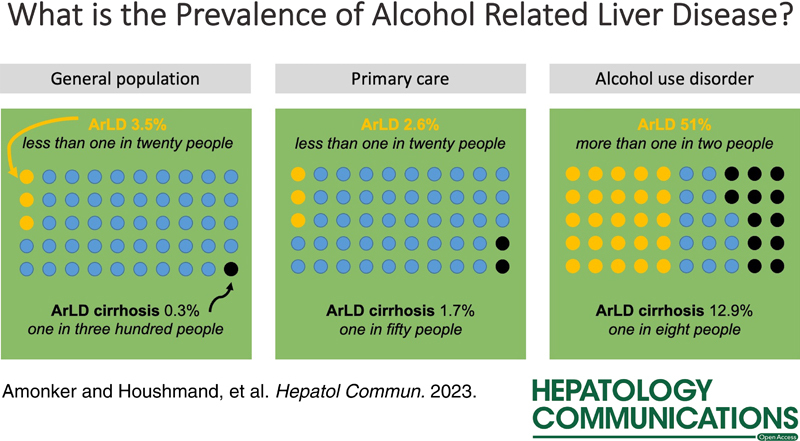

Thirty-five studies were included reporting on 513,278 persons, including 5968 cases of ALD, 18,844 cases of alcohol-associated fatty liver, and 502 cases of alcohol-associated cirrhosis. In unselected populations, the prevalence of ALD was 3.5% (95% CI, 2.0%–6.0%), the prevalence in primary care was 2.6% (0.5%–11.7%), and the prevalence in groups with AUD was 51.0% (11.1%–89.3%). The prevalence of alcohol-associated cirrhosis was 0.3% (0.2%–0.4%) in general populations, 1.7% (0.3%–10.2%) in primary care, and 12.9% (4.3%–33.2%) in groups with AUD.

Conclusions:

Liver disease or cirrhosis due to alcohol is not common in general populations and primary care but very common among patients with coexisting AUD. Targeted interventions for liver disease such as case finding will be more effective in at-risk populations.

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) is a common cause of morbidity and premature mortality worldwide,1 with a significant burden on health care systems.2 ALD is considered as a spectrum ranging from simple steatosis (alcohol-associated fatty liver) through increasing inflammation and scarring to cirrhosis (alcohol-associated cirrhosis), with the risk of liver-related outcomes varying across this spectrum.3 Acute alcohol-associated hepatitis is an acute and dangerous manifestation of ALD that can occur at any stage of underlying disease.

Advanced ALD is relatively easy to identify, but ALD is clinically silent for a long time and early disease may go unrecognized before symptoms occur. In consequence, reliable estimates of the prevalence of early disease require active identification of cases. The clinically silent period of disease is also an opportunity for intervention using noninvasive tests to identify people at risk of progression to advanced disease. The use of these tests needs to be guided by data regarding the epidemiology of ALD as the performance of noninvasive tests will vary depending on the prevalence of disease.

The cause of ALD is excessive alcohol consumption, which is also a common global issue.4 The public health policies of local, regional, and national governments regarding alcohol therefore have a critical role to play in preventing ALD; these policies need to be informed by the best available information on the prevalence of ALD.

To date, there has been no systematic synthesis of the prevalence of ALD. In this manuscript, we present the results of a systematic review of the prevalence of ALD across different health care settings.

METHODS

A systematic literature search was done using the terms “alcoholic liver disease or ALD or alcohol-related liver disease” and “epidemiology or prevalence” to search by title in PubMed and EMBASE. The results were limited to clinical studies published as full papers in English, published between 1948 and November 2022 when the final search was done. Citing literature and reference lists of included papers were reviewed for other relevant papers not identified in the initial search. The titles of papers identified by the literature search were reviewed for relevance and those that appeared suitable were reviewed in more detail. To be included, studies had to report the prevalence of ALD in a specified population tested with a specified screening test, with information about how ALD was defined and the population studied. Studies that used coding from medical records were not included as this did not represent systematic screening for detection of ALD. Searches and data extraction were done by Sachin Amonker and Aryo Houshmand, both medical students at the University of Leeds under the supervision of Richard Parker.

Once papers were identified as being suitable data were extracted into a preprepared spreadsheet. The data recorded for each study were first author, year of publication, location of study (by nation), the total studied population, the type of studied population [ie, unselected cohorts, alcohol-use disorder (AUD), primary care, or secondary care], the average age and alcohol consumption in the total population, the sex distribution in the studied population, the prevalence of hazardous alcohol use in the studied population and the definition of alcohol misuse, the type and the means of defining ALD, and the number of persons in the studied cohort with ALD, hepatic steatosis, advanced fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Alcohol-associated hepatitis was not considered as this is an acute condition where incidence is better considered rather than prevalence. For each analysis, we considered the overall prevalence of ALD and subtypes and the prevalence among hazardous drinkers in that population.

Data were analyzed with single-proportion meta-analysis and forest plots to illustrate the results. All analyses were done using the “meta” package in R. Preplanned subgroup analyses were done for differing methods of defining ALD and for differing geographical areas based on World Health Organization regions. These subgroup analyses were done for the prevalence of all ALD and for cirrhosis. The risk of bias of included studies was assessed using the tool described by Hoy et al.5 The study is reported according to the MOOSE checklist for meta-analysis of observational studies.6

As only published data in the public domain were used in this study, ethical review was not sought and individual patient consent was not relevant. Data were analyzed in R using the following packages: meta7 and ggplot2.8 This systematic review was registered with the PROSPERO database (reference CRD42022327429). No specific funding was received for this research.

RESULTS

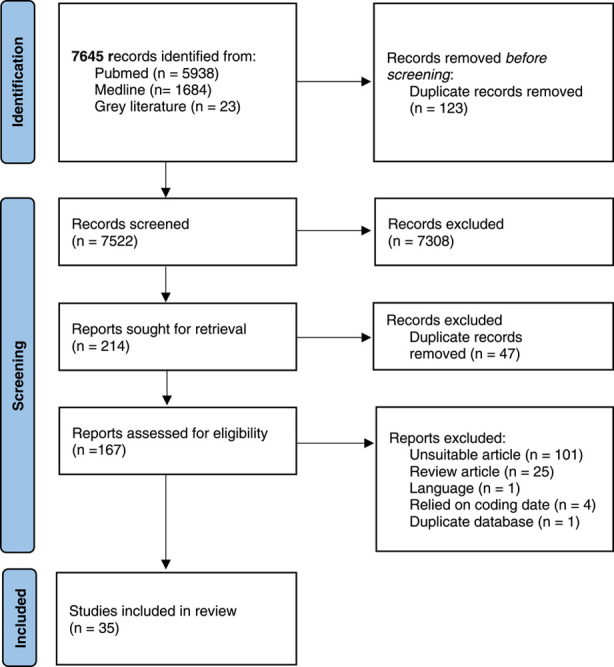

The literature search identified a total of 7645 studies. One hundred and twenty three duplicate studies were removed before screening so that 7522 titles were screened. Of these, 7308 were excluded leaving 214 records that were sought for retrieval. Of these studies, a further 47 were removed as duplicates. Of the one hundred and sixty-seven reports that were assessed for eligibility, one hundred and one were ineligible, twenty-five were review articles and one was rejected for language (Figure 1). Four studies were rejected as they relied on coding data, i.e. did not report a systematic examination of study populations. Two studies, Younossi 20219 and Wong 201910 used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) program in the United States; only data from Wong 2019 was included as this reported the most recent data (up until 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Systematic Review Flow Diagram.

The 35 included studies reported on a total of 513,278 persons, including 50,686 with AUD. The included studies reported on 5968 cases of ALD, 18,844 cases of alcohol-associated fatty liver, 780 cases of noncirrhotic fibrosis, and 502 cases of cirrhosis. A total of 23 studies reported the prevalence of ALD in unselected general populations, 7 reported on populations drawn from primary care, and 5 reported on cohorts with AUD. The majority of included studies were drawn from Europe (18 studies) and Western Pacific (14 studies) with 2 studies from the Americas and 1 from South-East Asia. Four of the 5 studies examining persons in alcohol treatment were drawn from Europe, and the majority of studies examining general unselected populations were from Western Pacific (12 of 23 studies). The details of included studies are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Details of included studies

| References | Country | Population | n | n hazardous alcohol | Age | Sex (% male) | Definition of hazardous alcohol use | Method | ALD | AFL | Fibrosis | AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AshaRani et al11 | Singapore | AUD | 101 | 101 | — | 81 | DSM V criteria for AUD | Biochemistry | 18 | — | — | — |

| Bayerl et al12 | Germany | General population | 384 | 88 | 56 | 58 | ≥ 20 g/d for women 40 g/day for men | Imaging | — | 44 | — | — |

| Bellentani et al13 | Italy | General population | 6917 | 707 | — | — | >60 g/d in men >30 g/d in women | Imaging | 254 | 233 | — | 20 |

| Burza et al14 | Italy | AUD | 384 | 384 | 46 | 76 | ≥ 24 g/d women ≥36 g/d for men | Biochemistry + imaging | — | — | — | 84 |

| Caballería et al15 | Spain | Primary care | 3014 | 275 | 54 | 43 | 21 standard drinking U/wk in men 14 standard drinking U/wk in women | Transient elastography | 44 | — | 28 | — |

| Chang et al16 | South Korea | General population | 218,030 | 37,856 | 39 | 57 | 30 g/d or greater for men 20 g/d or greater for women | Imaging | — | 13,890 | — | — |

| Chaudhary et al17 | Nepal | Hospital inpatients | 538 | — | — | — | — | Biochemistry + imaging | 42 | — | — | — |

| Chen et al18 | China | General population | 6598 | 1708 | 39 | 62 | — | Imaging | 450 | 283 | — | 23 |

| Dang et al19 | USA | General population | 44,631 | — | — | — | >28 g/d in women >42 g/d men | Biochemistry | 2708 | — | 89 | — |

| Fabrellas et al20 | Spain | Primary care | 495 | 46 | 47 | — | >21 or 14 U in men or women resp | Transient elastography | — | — | 3 | — |

| Fan et al21 | China | General population | 3175 | 242 | 52 | 38 | Alcohol consumption >210 g/wk for >5 y | Imaging | — | 61 | — | — |

| Foschi et al22 | Italy | General population | 3933 | — | — | — | ≥2 alcohol U/d in women ≥ 3 alcohol U/d in men | Imaging | — | 570 | — | — |

| Harman et al23 | UK | Primary care | 174 | 174 | 62 | 68 | >14 U/wk in women >21 U/wk in men alcohol AUDIT questionnaire score ≥8 Read codes related to alcohol misuse | Transient elastography | — | — | 31 | — |

| Kotronen et al24 | Finland | General population | 2766 | 503 | 60 | 51 | >20 g (for men) >10 g (for women) per day | Biochemistry | — | 195 | — | — |

| Labenz et al25 | Germany | Primary care | 11,859 | — | 60 | 56 | — | Biochemistry | — | — | — | 4 |

| Laskus et al26 | Poland | AUD | 70 | 70 | 39 | 93 | — | Biopsy | 56 | 18 | — | — |

| Li et al27 | China | General population | 9094 | — | 44 | 52 | >40 g ethanol/d for males >20 g ethanol/d for female | Imaging | — | 564 | — | — |

| Llop et al28 | Spain | General population | 11,440 | 1049 | 50.3 | 58.1 | AUDIT ≥ 8 | Transient elastography | 85 | — | 45 | 28 |

| Lorenzo et al29 | Spain | AUD | 220 | 85 | 53.8 | 0 | CAGE questionnaire | Biopsy | 58 | — | — | 30 |

| Nagappa et al30 | India | Primary care | 7624 | 818 | 46 | 56 | — | Transient elastography | — | — | 327 | — |

| Park et al31 | Korea | General population | 7517 | 451 | — | 49.6 | 40 g ethanol/d for men 20 g ethanol/d for women | Biochemistry | 107 | — | — | 5 |

| Pendino et al32 | Italy | General population | 1553 | 438 | 45 | 47% | >28 g >36 g ethanol/d | Biochemistry | 93 | — | — | — |

| Pose et al33 | Spain | General population | 3014 | 275 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 28 | — |

| Roulot et al34 | France | General population | 1190 | — | 64.8 | 68.32% | >30 g ethanol/d | Transient elastography | 27 | — | 27 | 5 |

| Sheron et al35 | UK | Primary care | — | 393 | — | — | AUDIT score ≥ 8 | Biochemistry | 47 | — | 45 | — |

| Shi et al36 | China | General population | 6043 | — | — | — | — | Imaging | — | 226 | — | — |

| Tajima et al37 | Japan | General population | 4579 | — | — | 49.9 | Quartiles of intake expressed as percentage of energy intake—highest quartile taken as hazardous | Imaging | — | 324 | — | — |

| Thiele et al38 | Denmark | AUD | 128 | 128 | 53 | 95 | >36 g ethanol/d for men > 24 g ethanol/d for women | Biopsy | — | 39 | 88 | — |

| Wang et al39 | China | General population | 7295 | 3119 | — | 0.5 | >40 g ethanol/d for men >20 g ethanol/d in women | Imaging | 624 | 125 | — | — |

| Wang et al40 | China | General population | 74,988 | — | — | — | >60 g ethanol/d | Transient elastography | 974 | — | — | — |

| Wong et al10 | USA | General population | 34,423 | — | — | — | >28 g ethanol/d women >42 g ethanol/d men | Biochemistry | — | 1480 | 69 | — |

| Yao et al41 | — | General population | 1690 | — | 47.9 | 67.46 | — | Imaging | 84 | — | — | — |

| Yan et al42 | China | General population | 3762 | — | 46.4 | 63 | >40 g ethanol/d in males >20 g ethanol/d in females | Biochemistry + imaging | 309 | — | — | — |

| Yoshimura et al43 | Japan | Primary care | 29,709 | 1520 | — | 100 | >420 g ethanol/wk | Imaging | — | 258 | — | — |

| Zhou et al44 | China | General population | 3543 | — | — | — | >40 g ethanol/d in males >20 g ethanol/d in females | Imaging | — | 79 | — | — |

Abbreviations: AC, alcohol-associated cirrhosis; AFL, alcohol-associated fatty liver; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; AUD, alcohol-use disorder.

The presence of absence of ALD was defined by imaging in 4 studies,13,18,39,41 transient elastography in 6 studies,15,23,28,33,34,40 biochemistry in 5 studies,11,19,25,31,32,35,45 and biopsy in 2 studies.26,29

Alcohol-associated fatty liver was mainly defined by imaging in 12 studies,12,13,16,18,21,22,27,36,37,39,42–44 also by biochemistry in 4 studies10,24,33,42 (including 1 study using imaging and biochemistry), and 2 studies used biopsy.26,38 Fibrosis was defined with significant variation between studies: only 1 study used biopsy;26 other studies used transient elastography with cutoffs of ≥6.0,30 ≥6.8,20 ≥8,15,33,34 and ≥10 kPa;28 2 studies used the Fibrosis-4 score with a cutoff of 2.6710,19; 1 study used the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) score25; and 1 study used the Southampton traffic light test.35 Thus, there were only 2 sets of studies that used directly comparable methodology to define fibrosis. Alcohol-associated cirrhosis was defined with biochemistry and imaging in 1 study,14 imaging in 3 studies,13,18,46) transient elastography using cutoffs of 1528 and 13 kPa,30 a combination of transient elastography, imaging and histology in 1 study23 and 3 studies used biopsy.26,29,38 The methods for diagnosis and any cutoffs used are tabulated in Supplemental Table 1 (http://links.lww.com/HC9/A249).

The individual assessment of bias for each included study is shown in Supplemental Table 2 (http://links.lww.com/HC9/A250). Thirty studies were considered low risk and 5 studies were considered high risk. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plots for each of the primary outcomes (Supplemental Material, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A256)—asymmetry in the funnel plots might indicate a level of bias in published material but may also simply reflect consistency in the estimates of prevalence.

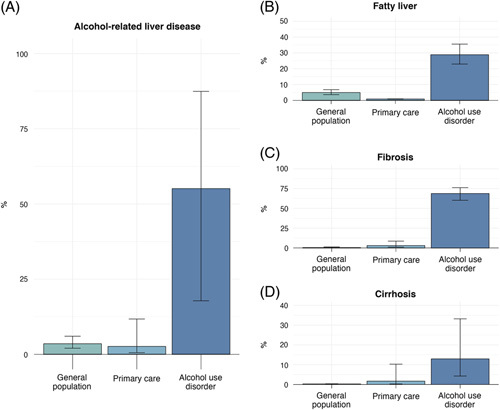

Prevalence of ALD

The prevalence of ALD varied across different settings: in unselected populations, the overall prevalence of any type of ALD was 3.5% (95% CI, 2.0%–6.0%), whereas in groups with AUD, the prevalence was 55.1% (17.8%–87.4%) (Table 2, Figure 2). The prevalence of ALD cirrhosis in general populations was 0.3% (0.2%–0.4%) and 12.9% (4.3%–33.2%) in groups with AUD. Forest plots for reported outcomes in each population are provided in the Supplemental Material, Supplemental Figures 2,4,6,8 (http://links.lww.com/HC9/A256).

TABLE 2.

Estimates for prevalence of ALD, alcohol-associated fatty liver, and alcohol-associated cirrhosis in unselected populations and in hazardous drinkers

| Prevalence in unselected population | Prevalence in hazardous drinkers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup of ALD (%) | Subgroup of ALD (%) | |||||||

| ALD | Fatty liver | Fibrosis | Cirrhosis | ALD | Fatty liver | Fibrosis | Cirrhosis | |

| General population | 3.5x (2.0–6.0) | 5.0 (3.5–6.9) | 0.5 (0.1–1.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 26.0 (14–31) | 28.1 (13–48) | 6.6 (3.2–5.7) | 2.2 (2–4) |

| Primary care | 2.6 (0.5–11.7) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 3.0 (1.0–8.6) | 1.7 (0.3–10.2) | 15.4 (11.6–20.2) | 17 (15.2–19.2) | 15.6 (7.9–28.5) | 9.8 (0.3–78.1) |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 55.1 (17.8–87.4) | 28.8 (17.9–35.1) | 68.8 (60.2–76.2) | 12.9 (4.3–33.2) | ||||

Abbreviation: ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of alcohol-associated liver disease: (A) presence of any liver disease, (B) prevalence of alcohol-associated fatty liver, (C) prevalence of hepatic fibrosis, and (D) prevalence of fibrosis.

Subgroup analyses

Methods of diagnosis

As different methods of diagnosis will have varying accuracy for detection of disease, a subgroup analysis was done after categorizing studies according to the method of diagnosis of ALD. In general, there were too few studies that analyzed the same outcome to allow for robust comparison between diagnostic methods, with the exception of studies describing presence of ALD in general populations. In this case, the study from Dang et al19 using imaging to define liver disease tended to produce higher estimates of ALD prevalence, that is, 7.0% (5.6%–8.6%) versus 3.8% (1.5%–9.4%) for biochemistry and 1.3% (0.7%–2.4%) for transient elastography, although estimates for the prevalence of alcohol-associated cirrhosis were similar for imaging and transient elastography [0.3% (0.2%–0.4%) and 0.2% (0.1%–0.4%), respectively] (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence depending on method of diagnosis

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | Alcohol-associated cirrhosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall estimate | Biochemistry | Imaging | Biopsy | Transient elastography | Overall estimate | Biochemistry | Imaging | Biopsy | Transient elastography | |

| General population | 3.5 (2.0–6.0) | 3.8 (1.5–9.4) | 7.0 (5.6–8.6) | — | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | — | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | — | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) |

| Primary care | 2.6 (0.5–11.7) | 2.2 (0.6–4.4) | — | — | 3.2 (0.7–13) | 1.7 (0.3–10.2) | — | — | — | 1.7 (0.3–10.2) |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 74 (60.8–83.9) | — | — | 74 (60.8 –83.9) | — | 12.9 (4.3 –33.2) | — | — | 12.9 (4.3 –33.2) | — |

Geographic location

Included papers were categorized by the World Health Organization region where the study was performed to illustrate the prevalence of ALD geographically (Table 4). No data were available for many areas. Where comparable, one study from Dang et al19 produced higher estimates of the prevalence of ALD than in Europe or Western Pacific, and a higher estimate of the prevalence of ALD cirrhosis in primary care was seen in South-East Asia [3.8% (3.5%–4.2%)] compared with Europe [0.6% (0.2%–1.8%)]. This analysis also illustrated that all data regarding the prevalence of ALD in primary care and in AUD were derived from European cohorts.

TABLE 4.

Prevalence depending on geographical source of study

| Alcohol-associated liver disease | Alcohol-associated cirrhosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall estimate | Americas | Europe | South-East Asia | Western Pacific | Overall estimate | North America | Europe | South-East Asia | Western Pacific | |

| General population | 3.5 (2.0–6.0) | 7 (5.6–8.6) | 3.0 (1.0–8.3) | — | 3.6 (1.6–7.7) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | — | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | — | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) |

| Primary care | 2.6 (0.5–11.7) | — | 2.6 (0.5–11.7) | — | — | 1.7 (0.3–10.2) | — | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 3.8 (3.5–4.2) | — |

| Alcohol-use disorder | 74 (60.8–83.9) | — | 74 (60.8–83.9) | — | — | 12.9 (4.3–33.2) | — | 12.9 (4.3–33.2) | — | — |

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review and meta-analysis addressed the prevalence of ALD. In unselected populations, ~3 people in a hundred have some form of ALD, but ALD cirrhosis is rare, affecting 3 people in a thousand. As expected, the prevalence of ALD in persons with AUD is higher: three-quarters have some form of ALD and more than 1 person in 10 has cirrhosis. These estimates vary slightly depending on the method of diagnosis and the geographic location of included studies, although these subgroup analyses to compare diagnostic modalities and geographic regions were severely limited by a lack of data. A major finding of this review is the paucity of data from systematic surveys to explore the prevalence of ALD, and this reduces the accuracy of our estimates.

The overall estimated prevalence of ALD of 3.5% can be compared with estimates for the prevalence of NAFLD based on recent meta-analysis, where an overall estimate of 32.4% was reported,47 almost 10 times greater. However, it must be remembered that the harm caused by ALD is similar or greater than NAFLD: ALD remains the leading indication for transplantation in many programs.48 The overall prevalence is comparable to estimates of the global prevalence of hepatitis B,49 although much lower than the prevalence of hepatitis B in areas of endemic disease. Other liver diseases including hepatitis C50 have lower overall prevalence than ALD.

The limits of the search strategy were selected to only include studies that deliberately set out to find cases of liver disease. This meant that several studies that reported on the prevalence of ALD based on coding of medical records were excluded. Although this reduces the number of studies and patients that we can report on, this limitation was chosen to ensure that prevalence data were not influenced by selection biases that might be present in studies based on coding. Despite searching for relevant studies from 1948 onward, the vast majority of included studies were from after 2000: only the studies by Bellentani et al13 and Laskus et al26 were from before this date. This in part reflects the interest in population-based studies that has developed from the landmark Dionysius study that Bellentani and colleagues performed in Italy in the early 1990s. The lack of data from pre-2000 is not necessarily a weakness: the predominance of recent data gives our conclusions greater relevance to current practice.

The estimates that we present are clearly limited by the availability of suitable studies to include in meta-analysis. The lack of available data and the variation in definitions of disease significantly limit our findings. It is also noteworthy that our systematic review included data from slightly more than half a million individuals, whereas similar papers in NAFLD included over 1 million. The assessment of quality of the included papers was generally reassuring where the most common reason for risk of bias was the inclusion of participants in such a way that the study cohort represented the study population. Although the funnel plots might indicate publication bias, this could also simply indicate similar findings from surveys looking for prevalence. The findings of this meta-analysis may be generalizable to Europe or Western Pacific, but the lack of studies from other regions limits the applicability in the Americas, Africa, and South-East Asia.

The estimates for ALD prevalence generated from the meta-analyses have significant heterogeneity (Supplemental Figures 1, 3, 5, and 7, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A249, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A251, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A253, http://links.lww.com/HC9/A255). This may be due at least in part to the differing methods of diagnosis and differing geographic locations of the studies. Planned subgroup analyses to examine diagnostic methods and geographic location revealed the paucity of data once these additional limits were imposed on the data; we could not drill further down to combine both location and method of diagnosis to explore this further. An additional source of heterogeneity may be differing cutoffs employed by differing studies. For example, there were several different cutoffs for transient elastography to define fibrosis. In the absence of an accepted definition for cutoff values, this is not unexpected, but a consensus from the field to inform future studies would be a step forward, for example, using values for the most recent BAVENO consensus statement of 15 kPa to diagnose compensated advanced chronic liver disease would bring a degree of consistency.

There are likely numerous applications of the estimates of prevalence of ALD that we have generated; in hepatology, this can be applied to the early detection of liver disease. Given the current performance of noninvasive tests for fibrosis, early detection of ALD is only likely to be efficient in the context of groups in the treatment for AUD. In other settings, including people with AUD in primary care, the prevalence of ALD or fibrosis cirrhosis is likely too low to consider screening for asymptomatic ALD, although this approach is supported by some guidelines.

Future research should focus on large-scale systematic surveys of prevalence of liver disease, including ALD, in regions where these data are currently lacking, using widely accepted methods of diagnosis. It is notable that more recent studies have used transient elastography to evaluate the prevalence of disease. Given the availability of controlled attenuation parameter included with many devices and the general acceptability to clinicians, this method would represent a convenient method to gauge presence and risk of disease in large cohorts.

This systematic review and meta-analysis is the first comprehensive data synthesis of the epidemiology of ALD. ALD as a whole is not uncommon, but advanced disease is largely confined to groups with coexisting AUD. The prevalence estimates that we report can guide hepatology practice and wider health policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Richard Parker consults for Durect and advises Novo Nordisk. The remaining authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFL, alcohol-associated fatty liver; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; AUD, alcohol-use disorder.

Sachin Amonker and Aryo Houshmand share first authorship.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.hepcommjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Sachin Amonker, Email: s.amonker@nhs.net.

Aryo Houshmand, Email: aryo.houshmand1@nhs.net.

Alexander Hinkson, Email: alexander.hinkson@nhs.net.

Ian Rowe, Email: i.a.c.rowe@leeds.ac.uk.

Richard Parker, Email: richardparker@nhs.net.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirode G, Saab S, Wong RJ. Trends in the burden of chronic liver disease among hospitalized US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parker R, Aithal GP, Becker U, Gleeson D, Masson S, Wyatt JI, et al. Natural history of histologically proven alcohol-related liver disease: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2019;71:586–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of alcohol use disorders and alcohol liver disease. Biomedicines. 2019;7:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, David Williamson G, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22:153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524–30.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong T, Dang K, Ladhani S, Singal AK, Wong RJ. Prevalence of alcoholic fatty liver disease among adults in the United States, 2001-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:1723–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. AshaRani PV, Karuvetil MZ, Brian TYW, Satghare P, Roystonn K, Peizhi W, et al. Prevalence and correlates of physical comorbidities in alcohol use disorder (AUD): a pilot study in treatment-seeking population. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayerl C, Lorbeer R, Heier M, Meisinger C, Rospleszcz S, Schafnitzel A, et al. Alcohol consumption, but not smoking is associated with higher MR-derived liver fat in an asymptomatic study population. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bellentani S, Tiribelli C, Saccoccio G, Sodde M, Fratti N, De Martin C, et al. Prevalence of chronic liver disease in the general population of northern Italy: the Dionysos Study. Hepatology. 1994;20:1442–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burza MA, Molinaro A, Attilia ML, Rotondo C, Attilia F, Ceccanti M, et al. PNPLA3 I148M (rs738409) genetic variant and age at onset of at-risk alcohol consumption are independent risk factors for alcoholic cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34:514–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Caballería L, Pera G, Arteaga I, Rodríguez L, Alumà A, Morillas RM, et al. High prevalence of liver fibrosis among European adults with unknown liver disease: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1138–1145.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang Y, Cho J, Cho YK, Cho A, Hong YS, Zhao D, et al. Alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and incident hospitalization for liver and cardiovascular diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:205–15.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaudhary A, Chaudhary AK, Chaudhary A, Bhandari A, Dahal S, Bhusal S. Alcoholic liver disease among patients admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine of a Tertiary Care Centre: a descriptive cross-sectional study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2022;60:340–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen SL, Meng XD, Wang BY, Xiang GQ. An epidemiologic survey of alcoholic liver disease in some cities of Liaoning Province. J Clin Hepatol. 2010;13:428–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dang K, Hirode G, Singal AK, Sundaram V, Wong RJ. Alcoholic liver disease epidemiology in the United States: a retrospective analysis of 3 US databases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fabrellas N, Alemany M, Urquizu M, Bartres C, Pera G, Juvé E, et al. Using transient elastography to detect chronic liver diseases in a primary care nurse consultancy. Nurs Res. 2013;62:450–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fan J-G, Zhu J, Li X-J, Chen L, Li L, Dai F, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in a general population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol. 2005;43:508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foschi FG, Bedogni G, Domenicali M, Giacomoni P, Dall’Aglio AC, Dazzani F, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in the general population of Northern Italy: the Bagnacavallo Study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harman DJ, Ryder SD, James MW, Jelpke M, Ottey DS, Wilkes EA, et al. Direct targeting of risk factors significantly increases the detection of liver cirrhosis in primary care: a cross-sectional diagnostic study utilising transient elastography. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kotronen A, Yki-Järvinen H, Männistö S, Saarikoski L, Korpi-Hyövälti E, Oksa H, et al. Non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease - two diseases of affluence associated with the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: the FIN-D2D survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Labenz C, Arslanow A, Nguyen-Tat M, Nagel M, Wörns M-A, Reichert MC, et al. Structured early detection of asymptomatic liver cirrhosis: results of the population-based liver screening program SEAL. J Hepatol. 2022;77:695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laskus T, Slusarczyk J, Lupa E, Cianciara J. Liver disease among Polish alcoholics. Contribution of chronic active hepatitis to liver pathology. Liver. 1990;10:221–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li H, Wang Y-J, Tan K, Zeng L, Liu L, Liu F-J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in Chengdu, Southwest China. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Llop E, Iruzubieta P, Perelló C, Fernández Carrillo C, Cabezas J, Escudero MD, et al. High liver stiffness values by transient elastography related to metabolic syndrome and harmful alcohol use in a large Spanish cohort. United European. Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:892–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lorenzo A, Auguet T, Vidal F, Broch M, Olona M, Gutiérrez C, et al. Polymorphisms of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes and the risk for alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease in Caucasian Spanish women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagappa B, Ramalingam A, Rastogi A, Dubey S, Thomas SS, Gupta E, et al. Number needed to screen to prevent progression of liver fibrosis to cirrhosis at primary health centers: an experience from Delhi. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:1412–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park SH, Kim CH, Kim DJ, Park JH, Kim TO, Yang SY, et al. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease among Korean adults: results from the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:1755–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pendino GM, Mariano A, Surace P, Caserta CA, Fiorillo MT, Amante A, et al. Prevalence and etiology of altered liver tests: a population-based survey in a Mediterranean town. Hepatology. 2005;41:1151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pose E, Pera G, Toran P, Gratacos-Gines J, Avitabile E, Exposito C, et al. Interaction between metabolic syndrome and alcohol consumption, risk factors of liver fibrosis: a population-based study. Liver Int. 2021;41:1556–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roulot D, Costes J-L, Buyck J-F, Warzocha U, Gambier N, Czernichow S, et al. Transient elastography as a screening tool for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in a community-based population aged over 45 years. Gut. 2011;60:977–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sheron N, Moore M, O’Brien W, Harris S, Roderick P. Feasibility of detection and intervention for alcohol-related liver disease in the community: the Alcohol and Liver Disease Detection study (ALDDeS). Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e698–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shi X-D, et al. Epidemiology and analysis on risk factors of non-infectious chronic diseases in adults in northeast China. J Jilin University. 37.2. 2011;37:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tajima R, Imamura F, Kimura T, Kobayashi S, Masuda K, Iida K. Association of alcohol consumption with prevalence of fatty liver after adjustment for dietary patterns: cross-sectional analysis of Japanese middle-aged adults. Clinical Nutrition. 2020;39:1580–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thiele M, Madsen BS, Hansen JF, Detlefsen S, Antonsen S, Krag A. Accuracy of the enhanced liver fibrosis test vs FibroTest, elastography, and indirect markers in detection of advanced fibrosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang H, Ma L, Yin Q, Zhang X, Zhang C. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease and its association with socioeconomic status in north-eastern China. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1035–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang H, Gao P, Chen W, Yuan Q, Lv M, Bai S, et al. A cross-sectional study of alcohol consumption and alcoholic liver disease in Beijing: based on 74,998 community residents. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yao J, Zhao Q, Xiong P, Dongmei H, Yao L, Zhu Y, et al. Investigation of alcoholic liver disease in ethnic groups of Yuanjiang county in Yunman. Weichangbingxue He Ganbingxue Zazhi. 2011;20:1137–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yan J, Xie W, Ou W-N, Zhao H, Wang S-Y, Wang J-H, et al. Epidemiological survey and risk factor analysis of fatty liver disease of adult residents, Beijing, China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1654–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoshimura Y, Hamaguchi M, Hashimoto Y, Okamura T, Nakanishi N, Obora A, et al. Obesity and metabolic abnormalities as risks of alcoholic fatty liver in men: NAGALA study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhou Y-J, Li Y-Y, Nie Y-Q, Ma J-X, Lu L-G, Shi S-L, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and its risk factors in the population of South China. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Opio CK, Seremba E, Ocama P, Lalitha R, Kagimu M, Lee WM. Diagnosis of alcohol misuse and alcoholic liver disease among patients in the medical emergency admission service of a large urban hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa; a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murali AR, Attar BM, Katz A, Kotwal V, Clarke PM. Utility of platelet count for predicting cirrhosis in alcoholic liver disease: model for identifying cirrhosis in a US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1112–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:851–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. OPTN/SRTR 2020 Annual Data Report: Liver. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2020/Liver.aspx.

- 49. Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blach S, Zeuzem S, Manns M, Altraif I, Duberg A-S, Muljono DH, et al. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:161–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.