Abstract

Recently, a new metabolic link between fatty acid de novo biosynthesis and biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxy-alkanoate) consisting of medium-chain-length constituents (C6 to C14) (PHAMCL), catalyzed by the 3-hydroxydecanoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein]:CoA transacylase (PhaG), has been identified in Pseudomonas putida (B. H. A. Rehm, N. Krüger, and A. Steinbüchel, J. Biol. Chem. 273:24044–24051, 1998). To establish this PHA-biosynthetic pathway in a non-PHA-accumulating bacterium, we functionally coexpressed phaC1 (encoding PHA synthase 1) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and phaG (encoding the transacylase) from P. putida in Pseudomonas fragi. The recombinant strains of P. fragi were cultivated on gluconate as the sole carbon source, and PHA accumulation to about 14% of the total cellular dry weight was achieved. The respective polyester was isolated, and GPC analysis revealed a weight average molar mass of about 130,000 g mol−1 and a polydispersity of 2.2. The PHA was composed mainly (60 mol%) of 3-hydroxydecanoate. These data strongly suggested that functional expression of phaC1 and phaG established a new pathway for PHAMCL biosynthesis from nonrelated carbon sources in P. fragi. When fatty acids were used as the carbon source, no PHA accumulation was observed in PHA synthase-expressing P. fragi, whereas application of the β-oxidation inhibitor acrylic acid mediated PHAMCL accumulation. The substrate for the PHA synthase PhaC1 is therefore presumably directly provided through the enzymatic activity of the transacylase PhaG by the conversion of (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-ACP to (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-CoA when the organism is cultivated on gluconate. Here we demonstrate for the first time the establishment of PHAMCL synthesis from nonrelated carbon sources in a non-PHA-accumulating bacterium, employing fatty acid de novo biosynthesis and the enzymes PhaG (a transacylase) and PhaC1 (a PHA synthase).

Most fluorescent pseudomonads belonging to rRNA homology group I are able to synthesize and accumulate large amounts of polyhydroxyalkanoic acids (PHAs) consisting of various 3-hydroxy fatty acids with carbon chain lengths ranging from 6 to 14 carbon atoms (medium chain length [MCL]) as carbon and energy storage compounds (1, 22). Pseudomonas fragi is an exception; it is not able to accumulate PHA from either fatty acids or other simple carbon sources such as gluconate (26). PHA composition depends on the PHA synthases present, the carbon source, and the metabolic routes involved (9, 16, 21). In Pseudomonas putida there are at least three different metabolic routes for the synthesis of 3-hydroxyacyl coenzyme A (CoA) thioesters, which are the substrates of PHA synthase (4, 15). β-Oxidation is the main pathway when fatty acids are used as the carbon source. Fatty acid de novo biosynthesis is the main route during growth on a carbon source which is metabolized to acetyl-CoA, like gluconate, acetate, or ethanol. The chain elongation reaction, in which acetyl-CoA moieties are condensed to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, is involved in PHA synthesis during growth on hexanoate. Recently, recombinant PHAMCL synthesis was also demonstrated in β-oxidation mutants of Escherichia coli LS1298 (fadB) and RS3097 (fadR) expressing PHA synthase genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8, 12, 13), indicating that the β-oxidation pathway in E. coli provides precursors for PHA synthesis. Taguchi et al. (23) provided evidence that the overexpression of the E. coli fabG gene, which encodes the 3-ketoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein (ACP)] reductase, in E. coli HB101 mediated the supply of (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA via fatty acid β-oxidation. It has also been shown recently that coexpression of the cytosolic thioesterase I gene and a PHA synthase-encoding gene in E. coli (fadB fadR) results in the synthesis of PHA composed mainly of 3-hydroxyoctanoate from the carbon source gluconate (6). These data suggested that the fatty acid de novo synthesis and the β-oxidation pathway were involved. However, only low-level accumulation, to about 2.3% of the cellular dry weight (CDW), has been attained, and the polymer has not been isolated. Moreover, overexpression of either the E. coli fabH or fabD gene, which encode 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III and the malonyl-CoA-ACP transacylase, respectively, in E. coli resulted in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) synthesis when the Aeromonas caviae synthase gene was coexpressed and when cells were cultivated on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plus glucose (24).

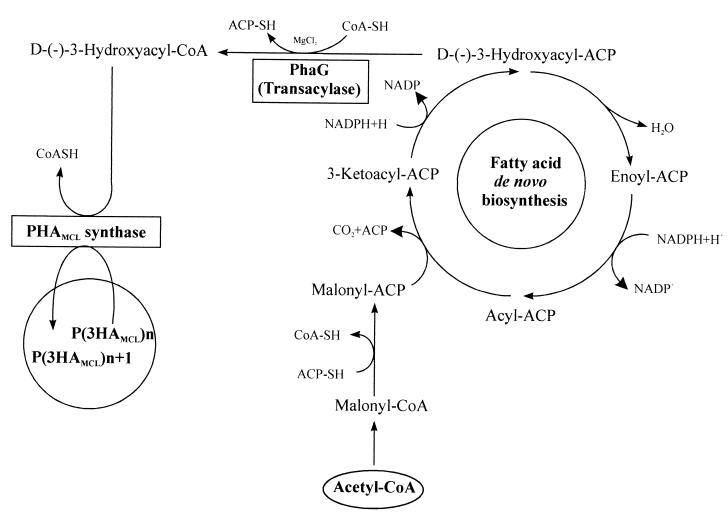

Since the primary structures of PHAMCL synthases and short-chain-length PHA synthases show extended homologies (16), and since in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)-accumulating bacteria such as Ralstonia eutropha (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA serves as a substrate, it seems likely that the substrate of PHAMCL synthases is (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA in pseudomonads. This was confirmed when the purified PHAMCL synthases from P. aeruginosa were found to exhibit in vitro enzyme activity with (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-CoA as the substrate (13). The main constituent of PHAs synthesized by P. putida KT2440 from gluconate is (R)-3-hydroxydecanoate (15, 26). Thus, to serve as a substrate for the PHA synthase, (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-ACP, an intermediate of fatty acid de novo synthesis, must be converted to the corresponding CoA derivative. Recently, the transacylase PhaG from P. putida, which catalyzes the transfer of the (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl moiety from the ACP thioester to CoA, was identified and characterized (15). Thus, PhaG directly links fatty acid de novo biosynthesis with PHA biosynthesis (Fig. 1). In recombinant Pseudomonas oleovorans, the expression of phaG leads to high-level accumulation of PHAMCL from nonrelated carbon sources. Since P. oleovorans produces large amounts of PHAMCL from fatty acids but is not able to accumulate PHAMCL from nonrelated carbon sources, functional expression of only the phaG gene established a new metabolic route of PHA synthesis (15).

FIG. 1.

PhaG-mediated metabolic route of PHAMCL synthesis from acetyl-CoA. 3HA, 3-hydroxyalkanoate.

To establish this metabolic pathway in non-PHA-accumulating bacteria, we employed recombinant P. fragi functionally expressing the phaC1 gene from P. aeruginosa and the phaG gene from P. putida. P. fragi was used in this study because this microorganism had already been established for biotechnological processes (10). In this paper, we describe for the first time PhaG-mediated accumulation of PHAMCL from nonrelated carbon sources in a non-PHA-accumulating bacterium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth of bacteria.

Pseudomonas and E. coli strains and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown at 37°C in complex LB medium. Pseudomonads were grown at 30°C in 300-ml baffled flasks containing 50 ml of either LB or mineral salts medium (MM) with 0.05% (wt/vol) ammonium chloride and 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate, unless otherwise indicated; if required, kanamycin sulfate was added at a concentration of 50 μg/ml (18).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in these studies

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida | ||

| GPp104 | PHA synthase-negative mutant of P. putida KT2442 (mt-2, hsdR1 [r− m+]) without TOL plasmid | 5 |

| PHAGN-21 | PhaG-negative mutant of P. putida KT2440 | 15 |

| P. fragi | Wild type | DSM 3456 |

| P. oleovorans | OCT plasmid | ATCC 29347 |

| E. coli | ||

| S17-1 | proA thi-1 recA; harbors the tra genes of plasmid RP4 in the chromosome | 19 |

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 (rk−, mk+) supE44 relA1 λ− lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15] | 17 |

| RS3097 | e14− (mcrA−) fadR41(ts) zcg-101::Tn10 | 20 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBHR71 | pBluescript SK(−) containing phaC1 from P. aeruginosa downstream of lac promoter | 8 |

| pBHR75 | pUCP27 containing the 1.3-kbp BamHI-HindIII fragment comprising phaG, including the native promoter | 15 |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Kmr, broad host range, lacPOZ′ | 7 |

| pBHR81 | pBBR1MCS-2 containing coding region of phaG downstream of lac promoter | 15 |

| pSF2 | pBBR1MCS-2 containing coding region of phaC1 gene from P. aeruginosa downstream of lac promoter | This study |

| pJRDEE32 | pJRD215 containing the phaC and phaJ genes of A. caviae | 3 |

| pPS2 | pBBR1MCS-2 containing coding region of phaC gene from A. caviae downstream of lac promoter | This study |

| pBHR86 | pBBR1MCS-2 containing coding region of phaC1 gene from P. aeruginosa downstream of lac promoter and coding region of phaG from P. putida downstream of phaC1, including the native promoter | This study |

Isolation, analysis, and manipulation of DNA.

DNA sequences of new plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing performed according to the chain termination method with a LI-COR automatic sequencer (model 4000L; MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). All other genetic techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (17).

Plasmid constructions.

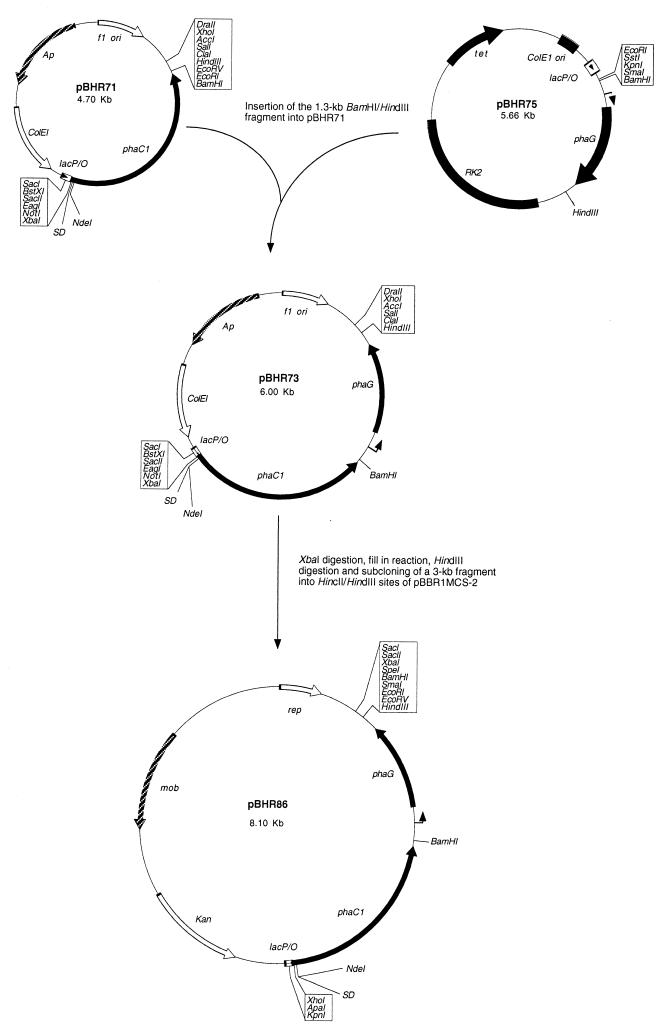

The 1.3-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment containing the P. putida phaG gene was isolated from plasmid pBHR75 (14) and subcloned into the respective sites of plasmid pBHR71 (8). The resulting plasmid, pBHR73, was hydrolyzed with XbaI, and a fill-in reaction was performed with the large fragment of DNA polymerase I. After hydrolysis with HindIII, a 3-kb fragment containing the P. aeruginosa phaC1 gene and the P. putida phaG gene was isolated and subcloned into the HincII and HindIII sites of pBBR1MCS-2, resulting in plasmid pBHR86, as outlined in Fig. 2. Plasmid pSF2 was constructed by amplifying the phaC1 gene coding region from plasmid pBHR71 (8) and introducing the restriction sites EcoRI (including the ribosome binding site) and BamHI, using the primers 5′-CCCGAATTCAATAAGGAGATATACATATGAGTCAG-3′ and 5′-TGCTCTAGAGGGCCCCCCCTCGAGGTC-3′. The resulting PCR product was subcloned into the respective sites of plasmid pBBR1MCS-2. The same strategy was applied to amplify the PHA synthase gene from A. caviae in plasmid pJRDEE32 (3), employing primers 5′-GCCGGAAT TCAATAAGGAGATATACATATGAGCCAACCATCTTATGGCCCG-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCTCATGCGGCGTCCTCCTCTGTTGG-3′. The PCR product was subcloned into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pBBR1MCS-2, resulting in plasmid pPS2.

FIG. 2.

Construction and restriction map of pBHR86. The arrow upstream of phaG indicates the transcriptional start point (15). SD, ribosome-binding site; Ap, ampicillin resistance gene; RK2 and rep, origins of replication.

Functional expression of the PHAMCL synthase gene.

PHA synthase activity was confirmed by expression of the respective PHA synthase gene in various metabolic backgrounds favoring PHAMCL synthesis, e.g., E. coli RS3097 and P. putida GPp104. Recombinant bacteria harboring the respective plasmid were cultivated in the presence of 0.25% (wt/vol) decanoate. PHA accumulation, determined by gas chromatography (GC) analysis of lyophilized cells, indicated in vivo PHA synthase activity.

Functional expression of the phaG gene.

Functional expression of phaG [encoding the (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-CoA:ACP transacylase] by the various constructs was confirmed by complementation of the phaG-negative mutant P. putida PhaGN-21 and establishment of the PhaG-mediated pathway in P. oleovorans (15). Recombinant cells were cultivated on MM plus 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate, and after 48 h of incubation at 30°C the PHA content of lyophilized cells was determined by GC analysis. PHA accumulation from gluconate indicated in vivo activity of PhaG.

GC analysis of polyester in cells.

PHA was qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed by GC. Liquid cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min; then the cells were washed twice in saline and lyophilized overnight. An 8- to 10-mg portion of lyophilized cell material was subjected to methanolysis in the presence of 15% (vol/vol) sulfuric acid. The resulting methyl esters of the constituent 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids were assayed by GC according to the method of Brandl et al. (2) and as described in detail recently (26). GC analysis was performed by injecting 3 μl of sample into a Perkin-Elmer (Überlingen, Germany) model 8420 gas chromatograph equipped with a 0.5-μm-diameter Permphase PEG 25 Mx capillary column 60 m in length.

Isolation of PHA from lyophilized cells.

PHA was extracted from lyophilized cells by using chloroform in a Soxhlet apparatus and subsequently precipitated in 10 volumes of methanol. To remove fatty acids, the precipitate was suspended in acetone, and it was again precipitated in methanol in order to obtain highly purified PHA.

GC-mass spectrometry.

Purified polymer, prepared as described above, was dissolved in chloroform at an approximate concentration of 5 mg/ml, and 3 μl was injected into a Hewlett-Packard (Palo Alto, Calif.) model 6890 gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer. The column used for the GC analysis and a temperature profile described previously (26) were employed.

GPC analysis.

A molecular weight analysis was conducted with purified PHA, which was dissolved in chloroform to a concentration of 5 to 10 mg/ml and introduced into a Waters (Milford, Conn.) gel permeation chromatography (GPC) system. The GPC system was equipped with Styragel columns HR3 to HR6. The eluted polymer was detected with a differential refractometer (model 410; Waters, Milford, Conn.). Polystyrene molecular weight standards with a narrow range of polydispersity were employed for calibration.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed according to the method of Sambrook et al. (17). Proteins were separated in SDS–12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. Western blotting was performed with a Semidry Fastblott apparatus (Fa. Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). In Western blot analyses (27) using nitrocellulose membranes, PhaC1 from P. aeruginosa was detected in crude extracts of recombinant P. fragi by applying anti-PhaC1 antiserum as a primary antibody and an alkaline phosphatase-antibody conjugate as a secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were detected by using nitroblue tetrazolium chloride and the toluidine salt of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate.

RESULTS

Construction of plasmids expressing either phaC1 and phaG or only the PHA synthase gene.

The non-PHA-accumulating fluorescent pseudomonad P. fragi, which is currently used in biotechnological production, was employed to establish a new metabolic pathway for PHAMCL production from nonrelated carbon sources. To achieve this goal, plasmid pBHR86 was constructed. This plasmid is a derivative of vector pBBR1MCS-2 and contains, colinear to and downstream of the lac promoter region, the phaC1 gene from P. aeruginosa and the phaG gene from P. putida, which encode a PHA synthase and an (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-CoA:ACP transacylase, respectively. The construction of plasmids is outlined in Fig. 2 and described in detail in Materials and Methods. In plasmid pBHR86, phaC1 is transcribed under lac promoter control, leading presumably to cotranscription of phaC1 and phaG (Fig. 2). Furthermore, plasmids pSF2 and pPS2 pBBR1MCS-2 derivatives which contain only the phaC1 gene from P. aeruginosa and phaC from A. caviae, respectively, under lac promoter control in the restriction sites EcoRI and BamHI, were constructed. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene and the transacylase gene from the respective plasmids was confirmed by complementation of P. putida GPp104 (a PHA synthase-negative mutant) or PHAMCL accumulation in E. coli RS3097 and by complementation of P. putida PHAGN-21 (a PhaG-negative mutant), respectively. Moreover, the recombinant-produced PHA synthases in P. fragi were detected by SDS-PAGE analysis and immunoblotting with anti-P. aeruginosa PhaC1 (anti-PhaC1Pa) antibodies (data not shown). The PHA synthase from A. caviae, whose corresponding gene was expressed from plasmid pPS2, was evidenced by an additional protein band in SDS-PAGE as well as by cross-reaction with the anti-PhaC1Pa antibody in immunoblotting.

Analysis of PHA synthesis in P. fragi expressing either a PHA synthase gene or phaG.

To investigate metabolic routes in P. fragi which provide substrates for the type II PHA synthase PhaC1, i.e., fatty acid β-oxidation and fatty acid de novo biosynthesis, we expressed in P. fragi only the phaC1Pa gene (pSF2), which mediated PHA synthesis in E. coli RS3097 (in the presence of the β-oxidation inhibitor acrylic acid) and P. putida GPp104 when decanoate was provided as a carbon source (data not shown). Moreover, we functionally expressed the A. caviae PHA synthase gene, using plasmid pPS2, in order to investigate the provision of (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA and (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoyl-CoA, which are the main substrates for the A. caviae PHA synthase. Recombinant P. fragi was cultivated on MM plus 0.05% (wt/vol) NH4Cl or on LB medium, with either decanoate or gluconate as the sole carbon source. GC analysis of the respective lyophilized cells showed that no PHA was synthesized from either carbon source when pSF2 was employed (Tables 2 and 3). However, expression of the A. caviae PHA synthase gene revealed traces of the comonomers 3-hydroxybutyrate and 3-hydroxyhexanoate (Table 3), which were not detected in P. fragi harboring only the vector, when decanoate was used as the carbon source. In addition, plasmid pBHR81, which expresses only the phaG gene from P. putida, was transferred to P. fragi but did not mediate accumulation of any PHA from gluconate (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Accumulation in recombinant P. fragi of PHA from gluconatea

| Plasmid [gene(s) contained] | PHA content (% [wt/wt] of CDW) | Composition of PHA (mol%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HHx | 3HO | 3HD | 3HDD | 3HDD:1 | ||

| None | Trace | ND | ND | Traceb | Trace | ND |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| pBHR81 (phaGPp) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| pSF2 (phaC1Pa) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| pPS2 (phaCAc) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| pBHR86 (phaC1Pa phaGPp) | 9.4 | 1 | 24 | 63 | 7 | 5 |

Cultivations were performed under conditions of PHA accumulation on MM containing 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate and 0.05% (wt/vol) ammonium chloride. Cells were grown for 48 h at 30°C. PHA content and composition of comonomers were analyzed by GC. Abbreviations: 3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate; 3HDD, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HDD, 1,3-hydroxydodecenoate; ND, not detectable; phaGPp, phaG gene from P. putida; phAC1Pa, phAC1 gene from P. aeruginosa; phaCAc; phaC gene from A. caviae.

Trace, ≤1% of CDW.

TABLE 3.

Accumulation of PHA in recombinant P. fragi via β-oxidation pathwaya

| Plasmid | Carbon source | Acrylic acid concn (mg/ml) | PHA content (% [wt/wt] of CDW) | Composition of PHA (mol%)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB | 3HHx | 3HO | 3HD | 3HDD | 3HDD:1 | ||||

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Decanoate | 0.0 | Traceb | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| 0.1 | Trace | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| 0.2 | Trace | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Gluconate | 0.0 | Trace | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| 0.1 | Trace | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| 0.2 | Trace | ND | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| pSF2 | Decanoate | 0.0 | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | Trace | ND |

| 0.1 | 2.8 | ND | 3 | 61 | 36 | Trace | ND | ||

| 0.2 | 3.3 | ND | ND | 42 | 58 | Trace | ND | ||

| pPS2 | Decanoate | 0.0 | Trace | Trace | Trace | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| 0.1 | 2.2 | 65 | 35 | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| 0.2 | 5.5 | 71 | 29 | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | ||

| pBHR86 | Decanoate | 0.0 | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | Trace | ND |

| 0.1 | 3.7 | ND | 3 | 50 | 38 | 9 | ND | ||

| 0.2 | 6.8 | ND | 2 | 34 | 59 | 5 | ND | ||

| pBHR86 | Gluconate | 0.0 | 10.0 | ND | 1 | 16 | 69 | 10 | 4 |

| 0.1 | 7.4 | ND | 2 | 16 | 64 | 13 | 5 | ||

| 0.2 | NG | ||||||||

Cells were cultivated on LB medium containing 0.2% (wt/vol) decanoate or 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate. Acrylic acid was applied to inhibit β-oxidation. Cultivations were performed for 48 h at 30°C. Abbreviations: 3HB, 3-hydroxybutyrate; 3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate; 3HDD, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HDD:1, 3-hydroxydodecenoate; ND, not detectable.

Trace, ≤1% of CDW.

PHAMCL synthesis from fatty acids in recombinant P. fragi on application of the β-oxidation inhibitor acrylic acid.

To investigate the potential use of the β-oxidation pathway for the provision of PHA precursor, we applied the β-oxidation inhibitor acrylic acid, which was previously used to promote PHAMCL synthesis in recombinant E. coli (13, 25). Inhibition of the β-oxidation pathway in P. fragi expressing the respective PHA synthase genes and the application of decanoate as the carbon source resulted in PHAMCL synthesis at levels ranging from 3 7% of the CDW. Various acrylic acid concentrations were used to study the effect of β-oxidation inhibition on PHA accumulation; a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml resulted in the highest level of PHAMCL accumulation, whereas acrylic acid at 0.3 mg/ml strongly inhibited growth (Table 3). With plasmids pSF2 and pBHR86, the ratio of the comonomers was shifted toward a higher molar ratio of 3-hydroxydecanoate when the acrylic acid concentration was increased from 0.1 to 0.2 mg/ml (Table 3). Interestingly, when P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86 was cultivated with gluconate as the carbon source, the acrylic acid concentration did not have a major influence on the comonomer composition (Table 3).

PHAMCL production from nonrelated carbon sources by P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86.

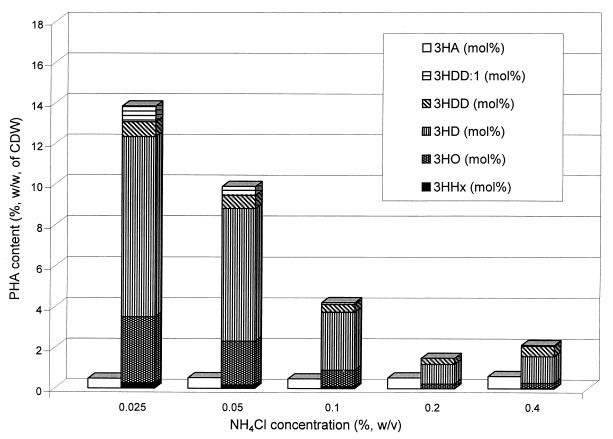

To establish in P. fragi a metabolic route which allows the formation of PHAMCL from nonrelated carbon sources, we coexpressed phaC1 and phaG in P. fragi. Plasmid pBHR86 mediated functional production of the PHA synthase and the respective transacylase in P. fragi. However, cultivation of P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86 in MM containing 0.05% (wt/vol) NH4Cl with gluconate as the sole carbon source resulted in PHA accumulation to about 10% of the CDW as revealed by GC analysis (Tables 2 and 4). The major constituent of the accumulated PHAMCL was 3-hydroxydecanoate, representing about 63 mol% of this comonomer (Table 2; Fig. 3). Other nonrelated carbon sources, such as citrate and glycerol, were used as sole carbon sources, and PHA accumulation to about 1.5 to 4% of the CDW was detected in recombinant P. fragi (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Accumulation of PHA in recombinant P. fragi using various carbon sources

| Plasmid | Carbon source (%, wt/wt) | PHA content (% [wt/wt] of CDW) | Composition of PHA (mol%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HHx | 3HO | 3HD | 3HDD | 3HDD:1 | |||

| pBBR1MCS-2 | Gluconateb (1.5) | Tracec | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND |

| Glucose (1.5) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | |

| Citrateb (1.0) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | |

| Glycerol (1.0) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | |

| Oleate (0.2) | Trace | ND | ND | Trace | Trace | ND | |

| pBHR86 | Gluconateb (1.5) | 9.2 | 2 | 22 | 63 | 7 | 6 |

| Glucose (1.5) | 2.4 | ND | 14 | 69 | 15 | 2 | |

| Citrateb (1.0) | 1.4 | ND | ND | 69 | 31 | ND | |

| Glycerol (1.0) | 3.9 | ND | 13 | 63 | 17 | 7 | |

| Oleate (0.2) | 5.6 | 11 | 43 | 33 | 12 | 1 | |

Cultivations were performed under PHA storage conditions on MM containing 0.05% (wt/vol) ammonium chloride and various carbon sources. Cells were grown at 30°C for 48 h. Abbreviations: 3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate; 3HDD, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HDD:1, 3-hydroxydodecenoate; ND, not detectable.

Corresponding sodium salt of carbon source was used.

Trace, ≤1% of CDW.

FIG. 3.

PHA accumulation and composition of P. fragi harboring either the vector pBBR1MCS-2 (left bars) or plasmid pBHR86 (right bars) upon application of various NH4Cl concentrations. Recombinant P. fragi was cultivated in 300-ml baffled flasks containing 50 ml of MM with 1.5% (wt/vol) sodium gluconate. The incubation was performed at 30°C for 48 h. 3HA, 3-hydroxyalkanoate; 3HDD:1, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HDD, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate.

The effect of the nitrogen concentration in the medium on PHA accumulation from nonrelated carbon sources was investigated. In P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86, nitrogen limitation attained by using 0.025% (wt/vol) NH4Cl led to the highest level of PHA accumulation, contributing about 14% of the CDW (Fig. 3). When 0.4% (wt/vol) NH4Cl was applied, PHA accumulation was significantly impaired.

Analysis of PHAMCL isolated from recombinant P. fragi.

To exclude the possibility that only 3-hydroxy fatty acid monomers were being accumulated in the cells, we isolated PHAMCL from pBHR86-harboring P. fragi cultivated on MM with gluconate as the sole carbon source. From 4.7 g of lyophilized cells was isolated about 0.4 g of purified polymer. GC and GC-mass spectrometry analysis of the purified polymer showed that it was mainly composed of 3-hydroxydecanoate, contributing about 60 mol% of the copolyester, and contained as additional constituents 2 mol% 3-hydroxyhexanoate, 21 mol% 3-hydroxyoctanoate, 11 mol% 3-hydroxydodecanoate, 4 mol% 3-hydroxydodecenoate, and 1 mol% 3-hydroxytetradecanoate. The purified polymer was subjected to GPC analysis. The respective PHAMCL showed a weight average molar mass of about 130,000 g mol−1 with a polydispersity of 2.2.

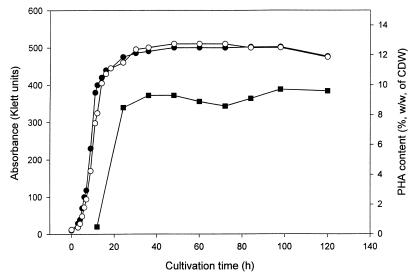

Physiology of PHAMCL accumulation in P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86.

P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86 was cultivated in MM with gluconate as the sole carbon source for a prolonged period in order to investigate the time-dependent accumulation of PHAMCL and to obtain data as to whether PHA degradation occurs in recombinant P. fragi. PHA accumulation did slightly decrease the growth rate of recombinant P. fragi (Fig. 4). PHA accumulation reached its maximum after a 24-h incubation period, and the PHA content remained constant over the entire incubation period of 5 days (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Growth curves of P. fragi harboring either vector pBBR1MCS-2 (●) or plasmid pBHR86 (○); PHAMCL accumulation by P. fragi(pBHR86) is also shown (■).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we documented for the first time the PhaG-mediated recombinant production of PHAMCL, in a non-PHA-accumulating bacterium, from nonrelated carbon sources, and the respective polyester was isolated from these cells (Fig. 1). The non-PHA-accumulating pseudomonad P. fragi was chosen because the use of this bacterium in biotechnological processes such as the production of d-lysine had already been established (10). The production of PHAMCL from nonrelated carbon sources, such as gluconate, in P. fragi was achieved by coexpression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from P. aeruginosa and the (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl-CoA:ACP transacylase gene phaG from P. putida. The recently identified protein PhaG is required for efficient accumulation of PHAMCL in P. putida when nonrelated carbon sources are provided (15). PhaG catalyzes the transfer of the (R)-3-hydroxydecanoyl moiety from the CoA thioester to ACP. Functional expression of only the phaG gene in P. oleovorans established the existence of a new pathway for biosynthesis of PHA from nonrelated carbon sources in this bacterium (15). P. oleovorans is not capable of PHAMCL synthesis when simple carbon sources are provided but accumulates large amounts of PHAMCL upon provision of fatty acids as a carbon source.

In contrast, it is known that P. fragi does not accumulate PHA either from fatty acids or from gluconate (26), and this was confirmed in the present study (Tables 2 and 3). Functional expression of only the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from P. aeruginosa or phaC from A. caviae, respectively, did not result in PHA synthesis either from fatty acids or from gluconate as a carbon source, suggesting that PHA precursors are not provided via the β-oxidation pathway or fatty acid de novo biosynthesis in the recombinant P. fragi. These data are consistent with the results of studies with wild-type E. coli expressing phaC1 from P. aeruginosa (8). In these studies only low-level PHAMCL synthesis, to a maximum of 1% of the CDW, was observed in recombinant E. coli when fatty acids or glucose was provided as the carbon source (8). High-level PHAMCL accumulation occurred only upon application of fad mutants of E. coli or with the use of the β-oxidation inhibitor acrylic acid, resulting in a PHA content of about 21 or 50% of the CDW, respectively (8, 13).

To demonstrate that inhibition of the β-oxidation pathway provides PHA precursors in recombinant P. fragi expressing a PHA synthase gene, we applied acrylic acid at various concentrations. The application of acrylic acid at 0.2 mg/ml resulted in PHAMCL synthesis in recombinant P. fragi only when grown on fatty acids. These data clearly indicated, consistent with the observations made in studies employing recombinant E. coli, that inhibition of the β-oxidation pathway of P. fragi provides intermediates of β-oxidation, which serve as precursors for PHA synthesis. Moreover, increasing the acrylic acid concentration shifted the PHA composition toward 3-hydroxyalkanoate comonomers with longer side chains. These data indicated that stronger inhibition of β-oxidation favored the provision of PHA precursors which were directly derived from the carbon source (fatty acid) and did not undergo further degradation.

Coexpression of the phaG gene together with the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from P. aeruginosa in P. fragi resulted in high-level PHAMCL accumulation, to about 14% of the CDW (Fig. 2 and 3), which is about sixfold higher than previously found for recombinant E. coli coexpressing a PHA synthase gene and the tesA gene, encoding the cytosolic thioesterase of E. coli (6). The polymeric character of this compound was confirmed, and the weight average molar mass as well as the comonomer composition was consistent with previously obtained data for polyesters recombinantly produced based on type II PHA synthases in E. coli (8, 12).

These data suggested that the PhaG-catalyzed metabolic link between fatty acid de novo biosynthesis and PHA biosynthesis was successfully established in P. fragi harboring plasmid pBHR86 (Fig. 1 and 2). In addition, these data provide strong evidence that the PhaG-mediated PHA biosynthetic pathway does not require the β-oxidation route, which favors PHA accumulation (Table 3). Since PHAMCL synthesis was recently demonstrated in the transgenic plant Arabidopsis thaliana, which functionally expressed the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from P. aeruginosa, the PhaG-mediated PHAMCL biosynthetic pathway might be also established in plants (11). Functional coexpression of phaG with a PHAMCL synthase gene in transgenic plants might provide a powerful tool for the industrial production of PHAMCL.

Since the phaC1 gene downstream of the lac promoter in plasmid pBHR86 is constitutively expressed in pseudomonads lacking a lac repressor, and since the phaG gene, downstream of phaC1, contains its native promoter, the effect of nitrogen limitation on PHAMCL accumulation in recombinant P. fragi cultivated on gluconate was studied (Fig. 3). PHAMCL accumulation was strongly impaired when 0.4% (wt/vol) NH4Cl was used and increased gradually with decreasing NH4Cl concentration (Fig. 3). Thus, expression of phaG might depend on the nitrogen concentration and nitrogen starvation might induce phaG expression. However, the phaG expression level was very low, and no additional protein band was detected by SDS-PAGE analysis. Further investigations, including quantification of phaG mRNA, will shed light on the transcriptional regulation of phaG. Physiological experiments monitoring PHAMCL accumulation in recombinant P. fragi over a 5-day incubation period did not show the decrease in PHA content observed in, e.g., P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4). This observation strongly suggests that recombinant P. fragi is not capable of reutilization of accumulated PHAMCL and thus may not produce a functional depolymerase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by EU-Fair grant CT96-1780.

We thankfully acknowledge construction of plasmid pPS2 by Patricia Spiekermann. Plasmid pJRDEE32 was kindly provided by Y. Doi.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson A J, Haywood G W, Dawes E A. Biosynthesis and composition of bacterial poly(hydroxyalkanoates) Int J Biol Macromol. 1990;12:102–105. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(90)90060-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandl H, Gross R A, Lenz R W, Fuller R C. Pseudomonas oleovorans as a source of poly(β-hydroxyalkanoates) for potential applications as biodegradable polyesters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1977–1982. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1977-1982.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukui T, Doi Y. Cloning and analysis of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) biosynthesis genes of Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4821–4830. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4821-4830.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huijberts G N M, de Rijk T C, de Waard P, Eggink G. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of Pseudomonas putida fatty acid metabolic routes involved in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1661-1666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huisman G W, Wonink E, Meima R, Kazemier B, Terpstra P, Witholt B. Metabolism of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by Pseudomonas oleovorans: identification and sequences of genes and function of the encoded proteins in the synthesis and degradation of PHA. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinke S, Ren Q, Witholt B, Kessler B. Production of medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) from gluconate by recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:540–548. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.540-548.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovach M E, Elzer P H, Hill D S, Robertson G T, Farris M A, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langenbach S, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Escherichia coli results in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madison L L, Huisman G W. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:21–53. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.21-53.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masakatsu, F., T. Eiji, S. Hiroyasu, and T. S. Co. 1996. Production of d-lysine. Japanese patent JP8173188.

- 11.Mittendorf V, Robertson E J, Leech R M, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A, Poirier Y. Synthesis of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in Arabidopsis thaliana using intermediates of peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13397–13402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Q, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) in Escherichia coli expressing the PHA synthase gene phaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of PhaC1 and PhaC2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi Q, Steinbüchel A, Rehm B H A. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi, Q., A. Steinbüchel, and B. H. A. Rehm. In vitro synthesis of poly(3-hydroxydecanoate): purification and enzymatic characterization of type II polyhydroxyalkanoate synthases PhaC1 and PhaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Rehm B H A, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A. A new metabolic link between fatty acid de novo synthesis and polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24044–24051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Biochemical and genetic analysis of PHA synthases and other proteins required for PHA synthesis. Int J Biol Macromol. 1999;13:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlegel H G, Kaltwasser H, Gottschalk G. Ein Submersverfahren zur Kultur wasserstoffoxidierender Bakterien: wachstumsphysiologische Untersuchungen. Arch Mikrobiol. 1961;38:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon R W, Egan P A, Chute H T, Nunn W D. Regulation of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: isolation and characterization of strains bearing insertion and temperature-sensitive mutations in gene fadR. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:621–632. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.2.621-632.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinbüchel A, Füchtenbusch B. Bacterial and other biological systems for polyester production. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:419–427. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinbüchel A, Füchtenbusch B, Gorenflo V, Hein S, Jossek R, Langenbach S, Rehm B H A. Biosynthesis of polyester in bacteria and recombinant organism. Polym Degrad Stabil. 1997;59:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taguchi K, Aoyagi Y, Matsusaki H, Fukui T, Doi Y. Coexpression of 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase and polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase genes induces PHA production in Escherichia coli HB101 strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;176:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taguchi K, Aoyagi Y, Matsusaki H, Fukui T, Doi Y. Overexpression of 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III or malonyl-CoA-ACP transacylase gene induces monomer supply for polyhydroxybutyrate production in Escherichia coli HB101. Biotechnol Lett. 1999;21:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thijsse G J E. Fatty-acid accumulation by acrylate inhibition of β-oxidation in an alkane-oxidizing pseudomonad. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;84:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0926-6542(64)90078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timm A, Steinbüchel A. Formation of polyesters consisting of medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids from gluconate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3360–3367. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3360-3367.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]