One of the best-established findings in behavioral economics is that people are often passive, and that defaults—what happens when individuals fail to act—have a major impact on outcomes. There is growing interest in applying this principle to improving outcomes in policy-relevant settings.

Health insurance offers instructive examples. Programs like the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) exchanges aim to provide affordable coverage via markets that allow for choice and competition. However, these arrangements add complexity, and there is evidence that consumers struggle to choose well (Abaluck and Gruber 2011; Bhargava, Loewenstein, and Sydnor 2017) and exhibit inertia in plan-switching decisions (Handel 2013, Ericson 2014; Ho, Hogan, and Scott Morton 2017). Default rules may therefore be quite impactful in these settings.

In this paper, we describe and evaluate a policy that leverages defaults to prevent loss of coverage when consumers lapse on premium payments, an important and underappreciated challenge in health insurance. Under standard rules, lapsers are disenrolled, leaving them uninsured unless they obtain other coverage. We discuss an alternate policy, which we call “automatic retention,” that instead defaults lapsers into a free plan if one is available.

We study auto-retention empirically in Massachusetts’s pre-ACA health insurance exchange, where the policy was used for several years with little attention. We are not aware of research that has described the policy or studied its effects.

We find that the policy has a major impact, retaining 14 percent of enrollees per year (weighted by duration enrolled). Auto-retention is the primary way consumers switch plans, creating three times more switches than occur actively during open enrollment. The policy differentially retains young, healthy, and low-cost people, implying important consequences for the market’s risk pool and extensive margin adverse selection. We conclude by discussing policy trade-offs and implications.

I. Background and Policy Context

Our setting is Massachusetts’s pre-ACA subsidized health insurance exchange, known as Commonwealth Care (CommCare). Established under the state’s 2006 “Romneycare” reform, CommCare provided subsidized private plans to low-income adults without access to insurance from an employer or public program. Subsidies were set to make the cheapest plan’s premium “affordable,” defined as 0–5 percent of monthly income. Additional background and statistics are discussed in online Appendix A.1

Like the ACA exchanges that followed it, CommCare took a regulated market-based approach. This structure puts policymakers in the position of market designers who set the rules under which insurers compete and consumers choose. Beyond standard “incentive” policies such as subsidies and benefit regulation, market designers also devise rules related to what Thaler (2018) calls “choice architecture,” which can have a large impact on boundedly rational consumers. Thoughtful choice architecture can “nudge” consumers toward desirable outcomes, while careless design can lead to poor outcomes. In this paper, we describe a nudge policy that affects what happens when consumers lapse on paying monthly premiums.

A. Challenge of Premium Lapses

Most enrollees in health insurance markets owe some balance of monthly after-subsidy premiums. This raises the challenge of ensuring that consumers pay their bills. Premium lapses are common in health insurance exchanges. While we do not directly observe lapses in our CommCare data, 6 percent of consumers terminate enrollment each month. Data on subsidized enrollees in Massachusetts’s post-ACA exchange (where reason for exit is observed) suggest that 30 percent of terminations are due to premium lapses.

The fundamental issue underlying lapsing is that the exchange has no way to automatically collect premiums.2 Consumers may opt out at any time, but what happens when they simply stop paying? Premium lapses create a dilemma for market designers. Should they disenroll the lapser—which may lead to a spell of uninsurance and associated adverse consequences—or weaken enforcement of premium collection? In practice, policymakers seek a balance, sending multiple notices over a grace period of two to three months before disenrolling a lapser. However, more creative approaches may be desirable to improve on this outcome.

B. Automatic Retention Policy

Auto-retention was an approach to reduce coverage interruptions for lapsers. Rather than automatically disenroll premium lapsers, the policy instead automatically switched them to a $0 premium plan if available. Lapsers carried debt for unpaid premiums but retained coverage unless they actively canceled or lost eligibility. If they paid this debt within 60 days, they could switch back to their old plan.

The key precondition for auto-retention is the availability of “backstop” coverage that is free (or more generally, in which up-front premium collection can be waived). In CommCare, this condition held only for the 100–150 percent of poverty income group, for whom the cheapest plan was free, while other plans varied from $2 to $34 per month. Auto-retention was not used for higher-income groups, which did not have access to a $0 plan.3 We use the 150–200 percent of poverty group (for whom the cheapest plan costs $39–40) as a control group in our analysis.

II. Data and Methods

Our main dataset is deidentified CommCare enrollment records linked to insurer claims. Online Appendix A describes the dataset and cleaning process. We limit our analysis to fiscal years 2010–2013, when the auto-retention policy was in place.4

A limitation of our data is that they do not include an indicator for plan switching due to auto-retention. We infer its use from the (much higher) rates of “mid-year” plan switching for the 100–150 percent of poverty group. We first drop a small number of known cases where mid-year switching is allowed (changes in service area or income group). To proxy for harder-to-observe exceptions, we use mid-year switching rates for the 150–200 percent “control” group.5 Our estimate of the rate of auto-retention is the excess mid-year switching rate for the “treatment” group (100–150 percent of poverty) relative to the controls.

A second limitation of the CommCare data is that it lacks information on other sources of health insurance. To assess whether auto-retention leads to duplicate coverage, we draw on Massachusetts’s All-Payer Claims Database (APCD), which lets us observe enrollment in both CommCare and nearly all other health insurance in the state. Online Appendix A further describes our APCD cleaning methods.

III. Results

A. Auto-retention Estimates

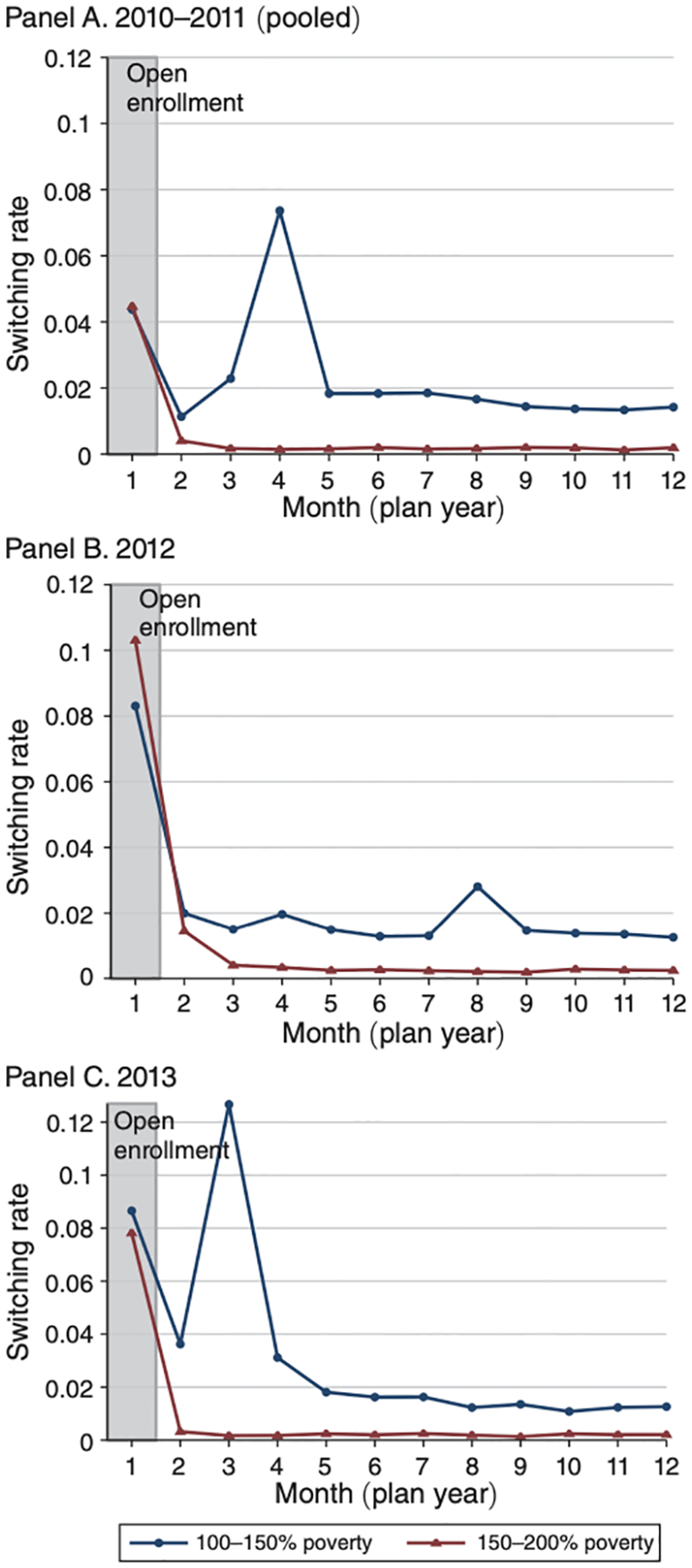

Figure 1 shows the switching patterns underlying our estimates. The panels show monthly plan-switching rates during 2010–2013 for the treatment and control groups (with 2010–2011 pooled because patterns are similar). Open-enrollment switches in the first month of the year (shaded in gray) are excluded from our estimates but shown for context.

Figure 1.

Share of Enrollees Switching Plans, by Month

Notes: The figure shows the share of sample enrollees who switch plans by month of the year for the treatment group subject to auto-retention (100–150 percent of poverty, in blue) and control group not subject to the policy (150–200 percent of poverty, in red). Panel A shows 2010–2011 (pooled because of similar patterns); panel B shows 2012; panel C shows 2013. Open enrollment, when switching is typically allowed, is shaded in gray. Higher switching rates in all other (“mid-year”) months for the treatment group indicate the impact of the auto-retention policy.

Two results stand out in Figure 1. First, mid-year switching rates are an order of magnitude higher for the treatment group (averaging 2.2 percent per month) compared to the control group (0.24 percent per month). The excess switching rate—our estimate of the impact of auto-retention—is 1.9 percent per month on average. When summed over all 11 mid-year months, auto-retention results in about 3 times more switches than occurs during formal open enrollment (which averages 6–7 percent for 1 month). Automatic retention is the primary way consumers switch plans in the treatment group.

To translate these monthly rates into annual estimates, we calculate the share of total enrollee-months accounted for by mid-year switchers in each year. This share is 15.3 percent in the treatment group and 1.5 percent in the control group, implying an excess share of 13.8 percent. This is our main estimate of the share of consumers affected by auto-retention.6

The second clear pattern in Figure 1 is a large switching spike in months three or four of each year except 2012. Excess switching rates average 9.3 percent during these spikes versus 1.4 percent in all other months. This appears to be driven by changes in which plans are free at the start of the year. When a plan shifts from free to nonfree, its enrollees face a choice to either (i) actively switch to a different plan that is now free or (ii) stick with their current plan and actively pay a premium. In practice, many enrollees do neither, instead lapsing. This results in an auto-switching spike just after the two-to three-month grace period ends.

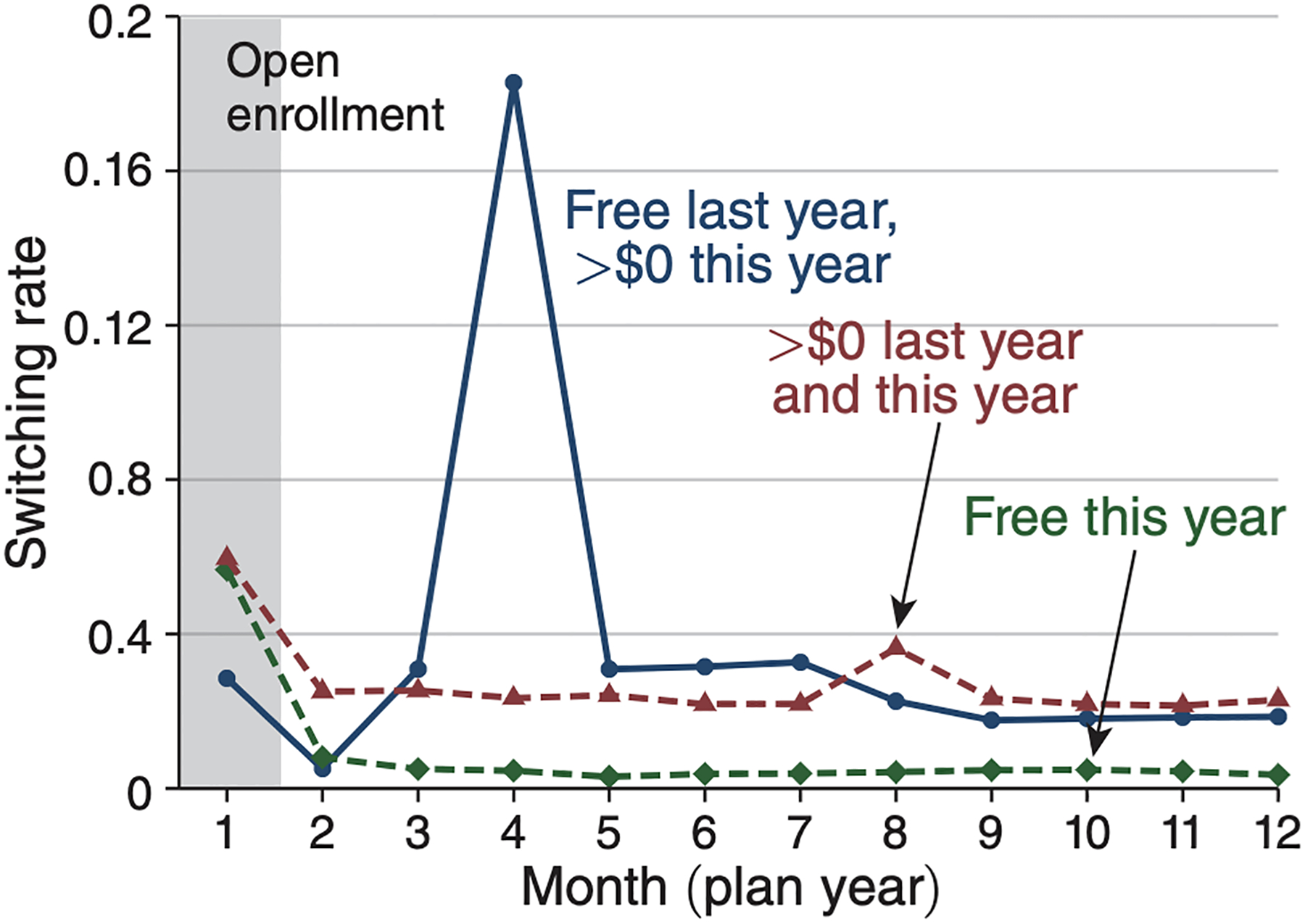

Figure 2 shows evidence for this interpretation. It breaks down treatment group switching rates by the origin plan’s free/nonfree status in the current and prior year.7 Only plans that shift from being free to nonfree (blue series) show a spike. Plans that remain nonfree in both years (red series) exhibit steady mid-year switching but no spike. Switching out of free plans (green series) is much lower; this is expected, as one cannot lapse on a $0 premium. This story also explains why there was no switching spike for 2012 in Figure 1: this was the only year that the prior year’s free plan remained free.8 These patterns suggest that plan transitions from free to nonfree are an important trigger for lapsing and may merit policymakers’ attention.

Figure 2.

Plan Switching, by Origin Plan Free/Nonfree Status

Notes: The figure breaks down switching rates for the treatment group (100–150 percent of poverty) by the free/nonfree status of the origin plan to understand the source of the large switching spike in Figure 1. It shows monthly switching rates out of three types of plans: (i) plans that were free last year but become nonfree this year (blue solid line), (ii) plans that were nonfree (>$0) both last year and this year (red dashed), and (iii) plans that are free this year, regardless of their premium last year. Statistics are pooled across 2010–2012 for simplicity, with 2013 omitted because of its different timing of the spike (month three rather than month four). Results are similar if broken down separately by year (see online Appendix Figure B.2). The figure indicates that all of the large switching spike comes from enrollees in plans that change from being free to nonfree at the start of the new year.

B. Mechanisms: Financial versus Hassle Cost

Why do so many enrollees lapse on paying premiums? While the reasons are undoubtedly complex, one key question is whether lapsing reflects the financial cost (or “affordability”) of a higher premium or the hassle cost of paying any positive premium (e.g., the time and attention cost of remembering to pay the bill). These stories have different policy implications so are worth distinguishing.

To do so, we explore the relationship between mid-year switching rates and the premium of the origin plan (see online Appendix Figure B.3). Our analysis suggests a role for both mechanisms. Hassle costs appear to be key during the month three to four switching spike. There is little relationship between origin plan premium and auto-switching rates, and they are high even in cases with very low premiums (<$5 per month). One example is illustrative: a plan whose premium increased from $0 to $3 at the start of 2013. Following this change, 24 percent of its enrollees auto-switch out in month 3 of 2013, and another 2.5 percent per month switch out during the rest of the year. It is implausible that $3 per month is unaffordable; instead, this must reflect some form of hassle cost.

We do, however, see evidence for financial costs mattering outside of the month three to four spike. For these months, we find that an additional $10 per month premium obligation raises the mid-year switching rate by 0.5–1.0 percent points (relative to an average of 1.8 percent). Although $10 is a modest amount—just 1 percent of monthly income even at the poverty line—this analysis shows that even nominal premiums can deter enrollment in low-income groups.

C. Heterogeneity Analysis

The auto-retention policy differentially affects certain groups. Online Appendix Table B.2 compares mid-year switchers (a proxy for autoretained enrollees) to all other enrollees in the treatment group. Switchers are younger (by 4.1 years), less likely to have a chronic illness (by 3.4 percent points, or 6 percent), and have lower medical risk scores (by 0.025, or 2.5 percent lower predicted spending). Their average medical spending per month enrolled is 8.6 percent lower. Notably, the larger percentage gap in spending than risk score indicates that switchers are differentially profitable even after risk adjustment. Spending for auto-switchers is particularly low in the six months following the auto-switch, consistent with research showing that enrollees lapse at times when they use less health care (Diamond et al. 2020).

The average switcher stays enrolled in CommCare for ten months after the switch, which is substantial in a market where typical durations are about a year. Notably, 15 percent of switchers “reswitch” within 3 months of their auto-switch. This is nontrivial but implies that the vast majority (85 percent) stick with their newly assigned plan, boosting the market share of these lowest-price plans.

D. Is the Policy Duplicating Coverage?

A key concern with auto-retention is that it retains enrollees who may have gained other insurance (e.g., via a new job) and should technically be ineligible for CommCare.9 Duplicative coverage would not harm enrollees but would result in unneeded public spending on subsidies. Using the APCD, however, we find that coverage duplication rates for CommCare enrollees are low (3.1 percent) and not much different for enrollees in the 11 months surrounding a mid-year plan switch (3.6 percent).

IV. Discussion

This paper has described a policy we call “automatic retention,” which Massachusetts used in its pre-ACA insurance exchange to reduce termination for premium nonpayment among low-income health insurance enrollees. Rather than disenrolling lapsers, the policy automatically switched them to a free plan if one was available. Our analysis suggests the policy had a major impact, retaining 14 percent of consumers per year. Retained enrollees are younger, healthier, and lower cost, suggesting that the policy improves the market risk pool. We were concerned auto-retention would lead to duplicate coverage, but evidence from the APCD suggests duplication is rare and not much different for enrollees around the time of mid-year plan switches.

A limitation of our analysis is that we do not see counterfactual outcomes for the 100–150 percent of the poverty treatment group without auto-retention in place. Absent auto-retention, we expect that lapses would mechanically lead to termination, but we do not know how transient or long lasting the coverage gap would be. In separate work on the post-ACA Massachusetts exchange (when auto-retention was no longer in effect), McIntyre (2021) finds that changes in which plans were free/nonfree led to a large spike in terminations due to nonpayment for the same 100–150 percent of poverty group. The vast majority of terminated consumers do not return within 12 months, suggesting that coverage gaps may be significant.

The finding that defaults matter for retaining enrollees in health insurance adds to a broader literature on the power of defaults in shaping market outcomes. Most prior work on defaults within health insurance has focused on consumer inertia when given an opportunity to switch plans. In ongoing work on the same Massachusetts market, two of us also find large impacts of an automatic enrollment default during the initial sign-up process (Shepard and Wagner 2021).

Our findings point to a key role for the hassle cost of paying a premium in driving lapses rather than affordability. “Hassles” may reflect a variety of factors, including informational barriers (e.g., lost or unopened mail notices), the time cost of setting up online autopayment, or the attention cost of remembering to write a check each month. Further research into mechanisms would be useful in guiding policy responses. Finding a way to withhold or collect premiums automatically—a strategy used successfully by employers and Medicare—would address many of these issues.

There are trade-offs inherent to auto-retention. In reducing terminations, the policy increases subsidized insurance enrollment. On the one hand, reducing uninsurance is a key policy goal. On the other hand, public subsidy spending also rises. Whether that spending is “worth it,” given benefits to the newly insured and spillover benefits to society, is a key issue animating current debate about the ACA.

Another trade-off involves the policy’s effect on competitive incentives. The policy boosts market share for the lowest-price plan(s) that receive auto-switched individuals. This should encourage insurers to compete aggressively to be the lowest-price plan. However, this price competition could lead to quality reductions and may be distorted by risk selection incentives. Like other policies, auto-retention appears to involve a trade-off between improving risk selection on the extensive margin while worsening it on the intensive margin (Saltzman 2020, Geruso et al. 2019).

Implementation of auto-retention in other settings such as the ACA exchanges would face similar trade-offs in addition to legal and practical challenges. Nonetheless, our evidence suggests that if these challenges could be surmounted, changing default rules can meaningfully improve coverage retention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our discussant, Fiona Scott Morton, and Kate Ho, Marissa Woltmann, and Michael Norton for helpful comments. We thank the Massachusetts Health Connector for assistance in providing and interpreting the data. We gratefully acknowledge funding from Harvard’s Lab for Economic Applications and Policy, Harvard Kennedy School’s Rappaport Institute for Public Policy, and Harvard’s Milton Fund. All errors are our own.

Footnotes

Go to https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20211083 to visit the article page for additional materials and author disclosure statement(s).

Several previous papers have drawn on CommCare’s rich data and policy variation to glean insights about consumer behavior and health insurance competition. See Chandra, Gruber, and McKnight (2014); Finkelstein, Hendren, and Shepard (2019); and Shepard (2016).

As such, an alternate approach would be to find a way to automatically collect or withhold premiums, possibly via the tax system. This approach is used successfully by both employers (withholding from paychecks) and Medicare (withholding from Social Security benefits). Autocollection via taxes was not feasible in CommCare due to cross-department legal and administrative barriers. But tax-based collection seems a natural fit for exchange plans, where subsidies are administered by the IRS as income tax credits.

Auto-retention was unnecessary for below-poverty enrollees who had access to all plans for free, making premium lapsing moot.

Auto-retention appears to have been used inconsistently in 2009, so we exclude it for simplicity. It was not used prior to 2009, since all plans were free for the 100–150 percent of poverty group.

Other exceptions include the dropping of an enrollee’s PCP from network and receipt of a special hardship waiver. In practice, these appear to be rare; the control group’s mid-year switching rates are less than 0.3 percent per month.

This estimate of 13.8 percent is lower than 11 times the monthly excess switching rate (1.9 percent) because of consumer churn into and out of the sample. See online Appendix Table B.1 for these statistics.

Figure 2 pools estimates for 2010–2012 and omits 2013 because of the different spike timing in 2013 (month three rather than four). CommCare updated regulations at this time, limiting the grace period to two months starting in 2013. Online Appendix Figure B.2 shows estimates for each year from 2010–2013, which are similar to the pooled results.

This is true statewide except for one small area in western Massachusetts, where (because of an insurer entry) the free plan in 2011 became nonfree in 2012. Consistent with our story, we see a large (19.0 percent) switching spike in this region only (see online Appendix Figure B.2). Because the area is small, it is not visible in Figure 1.

The exchange attempts to avoid duplication via a unified Medicaid-CommCare enrollment system (which should mechanically prevent inappropriate duplication), annual eligibility redetermination, and periodic cross-checks of enrollee lists for commercial insurance. However, these safeguards may still miss some enrollees.

Contributor Information

Adrianna McIntyre, Harvard University.

Mark Shepard, Harvard Kennedy School and NBER.

Myles Wagner, Harvard University.

REFERENCES

- Abaluck Jason , and Gruber Jonathan. 2011. “Choice Inconsistencies among the Elderly: Evidence from Plan Choice in the Medicare Part D Program.” American Economic Review 101 (4): 1180–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava Saurabh, Loewenstein George , and Sydnor Justin. 2017. “Choose to Lose: Health Plan Choices from a Menu with Dominated Option.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (3): 1319–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Amitabh, Gruber Jonathan , and Robin McKnight. 2014. “The Impact of Patient Cost-Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Evidence from Massachusetts.” Journal of Health Economics 33: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond Rebecca, Dickstein Michael J., Timothy McQuade , and Petra Persson. 2020. “Insurance without Commitment: Evidence from the ACA Marketplaces.” https://web.stanford.edu/~perssonp/ACA_Dropout.pdf.

- Ericson Keith M. Marzilli. 2014. “Consumer Inertia and Firm Pricing in the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Insurance Exchange.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6 (1): 38–64. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein Amy, Hendren Nathaniel , and Shepard Mark. 2019. “Subsidizing Health Insurance for Low-Income Adults: Evidence from Massachusetts.” American Economic Review 109 (4): 1530–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geruso Michael, Layton Timothy J., Grace McCormack , and Shepard Mark. 2019. “The Two Margin Problem in Insurance Markets.” NBER Working Paper 26288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Handel Benjamin R. 2013. “Adverse Selection and Inertia in Health Insurance Markets: When Nudging Hurts.” American Economic Review 103 (7): 2643–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Kate, Hogan Joseph , and Fiona Scott Morton. 2017. “The Impact of Consumer Inattention on Insurer Pricing in the Medicare Part D Program.” RAND Journal of Economics 48 (4): 877–905. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis. 2016. “Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database, version 3.0.” Available only via data use agreement (accessed March 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Health Connector. 2006–2013. “Administrative data on the Commonwealth Care Program.” Available only via data use agreement (accessed January 2014). [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre Adrianna. 2021. “Small Premiums or Big Administrative Burdens? Enrollment Consequences of Introducing Nominal Monthly Contributions in the Massachusetts Subsidized Nongroup Market.” https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/mcintyre/files/premiumburden_abstract.pdf.

- Saltzman Evan. 2020. “Managing Adverse Selection: Underinsurance vs. Underenrollment.” 10.2139/ssrn.3256867. [DOI]

- Shepard Mark. 2016. “Hospital Network Competition and Adverse Selection: Evidence from the Massachusetts Health Insurance Exchange.” NBER Working Paper 22600.

- Shepard Mark , and Wagner Myles. 2021. “The Economics of Automatic Health Insurance Enrollment.” https://scholar.harvard.edu/mshepard/publications/economics-automatichealth-insurance-enrollment.

- Thaler Richard H. 2018. “From Cashews to Nudges: The Evolution of Behavioral Economics.” American Economic Review 108 (6): 1265–87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.