Abstract

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) is recorded as the fifth most common cancer worldwide with high morbidity and mortality. The most urgent problem in BCs is the high recurrence rate as two-thirds of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) will develop into muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), which retains a feature of rapid progress and metastasis. In addition, only a limited number of biomarkers are available for diagnosing BC compared to other cancers. Hence, finding sensitive and specific biomarkers for predicting the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with BC is critically needed. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the expression and clinical significance of urinary lncRNA BLACAT1 as a non-invasively diagnostic and prognostic biomarker to detect and differentiate BCs stages.

Methods and results

The expression levels of urinary BLACAT1 were detected by qRT-PCR assay in seventy (70) BC patients with different TNM grades (T0-T3) and twelve (12) healthy subjects as control. BLACAT1 was downregulated in superficial stages (T0 = 0.09 ± 0.02 and T1 = 0.5 ± 0.1) compared to healthy control. Furthermore, in the invasive stages, its levels started to elevate in the T2 stage (1.2 ± 0. 2), and higher levels were detected in the T3 stage with a mean value of (5.2 ± 0.6). This elevation was positively correlated with disease progression. Therefore, BLACAT1 can differentiate between metastatic and non-metastatic stages of BCs. Furthermore, its predictive values are not like to be influenced by schistosomal infection.

Conclusions

Upregulation of BLACAT1 in invasive stages predicted an unfavorable prognosis for patients with BCs, as it contributes to the migration and metastasis of BCs. Therefore, we can conclude that urinary BLACAT1 may be considered a non-invasive promising metastatic biomarker for BCs.

Keywords: BLACAT1, Bladder cancer, LncRNA, Metastatic marker

Introduction

Malignant bladder cancers are the greatest common tumors in the genitourinary system. Globally, Bladder cancer (BC) alarms around 550,000 new cases annually and its frequency is continually increasing [1]. BC is divided into two subgroups: non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), an early stage of cancer (stages T0 to T1), and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), which is more destructive (stages T2 to T4). At diagnosis, the majority of BCs are NMIBC [2, 3]. Early diagnosis and handling of tumorous lesions are assumed to be essential for dropping the risk of relapse and improving the prognosis of NMIBC [4]. Regardless of enhancements in current clinical management such as surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, 50–70% of patients are relapsed within the next 5 years [5]. Hence, it is crucial to discover novel molecular markers for diagnosis at the primary stage and detect effective therapeutic marks for improving the survival rate of BC patients.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a subgroup of RNAs that have above 200 nucleotides in length with no obvious open reading frames (ORFs); however, they have conventional secondary structures [6]. LncRNAs can interact with DNA, RNA, or proteins as molecular sponges, scaffolds, and activators to play key regulatory roles in a diversity of biological processes, such as proliferation, migration, invasion, differentiation, and apoptosis [7]. The role of lncRNAs in the manifestation and expansion of numerous human cancers has been widely studied and certain lncRNAs were described to act as promising markers for prognosis, estimation, or diagnosis for some cancer grades [8, 9].

With regards to BC, several studies have submitted that urine-based lncRNAs may function as talented biomarkers and may influence overall patient survival and mortality [10, 11]. Only a few lncRNAs have been proved experimentally, but their effects in regulating gene expression rest to be decoded.

Bladder cancer-associated transcript 1 (BLACAT1), also entitled linc-UBC1, is found at the locus of human chromosome 1q32.1 with a length of 2616 kb and has only 1 exon [12]. Initially, it was recognized by He et al. in 2013 and defined as non-coding based on sequence analysis [12]. Furthermore, nuclear fractionation of BC cells revealed that BLACAT1 is preferentially located in the nucleus. Behind these results, BLACAT1 engrossed a large amount of attention from cancer scientists. Many evolving studies revealed that BLACAT1 was abnormally expressed in different cancers, including colorectal cancer (CRC) [13], gastric cancer (GC) [14], and lung cancer (LC) [15]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed by Lu et al. demonstrated that elevated BLACAT1 expression could predict shorter survival, progressive TNM stage, and elevated lymph node metastasis in solid tumors [16]. These pioneer recommendations exhibited the clinical importance of BLACAT1 in the diagnosis and prognosis of tumors.

Although, Urine Cystoscopy is accepted as a gold standard for BC screening, as it is non-invasive, low-priced, and safe. Even though it is highly specific, the results are not reproducible, and the explanation is extremely dependent on the cytologist’s skills [17]. This calls for exploring other molecular urine markers for BC screening which should be non-invasive, specific, sensitive, reproducible, and done at an appropriate cost. So, the present study aimed to decode our knowledge of the prognostic and diagnostic value of urinary BLACAT1 for differentiating pathological grades of BCs in Egyptian patients.

Patients and methods

The current study was achieved on seventy (70) BC Egyptian patients from the cystoscopy unit of the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, in addition to twelve (12) healthy subjects as control. Demographic data and medical history were collected from patients’ hospital files. Tumor staging and grading were diagnosed according to the tumor, necrosis, and metastasis (TNM) classification of UICC (Union for International Cancer Control) [18]. Patients were classified according to their tumor grades into 4 groups with grades (T0–T3). Also, patients were further classified into the Schistosomal BC group (no = 37) and non-Schistosomal BC group (no = 33) as shown in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data of the studied subjects

| Schistosomal group | Non-schistosomal group | Total | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean): | 62.77 | 59.8 | 61.3 | 50.5 |

|

Sex: Male Female |

33 3 |

19 15 |

52 18 |

7 5 |

| TMN stages: T0 | 8 | 4 | 12 | |

| T1 | 7 | 7 | 14 | |

| T2 | 13 | 11 | 24 | |

| T3 | 9 | 11 | 20 | |

| NMIBC (T0 + T1) | 15 | 11 | 26 | |

| MIBC (T2 + T3) | 22 | 22 | 44 | |

| Total | 37 | 33 | 70 | 12 |

TMN tumor, necrosis, and metastasis, NMIBC non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, MIBC Muscle invasive bladder cancer

All subjects (patients and control) retained informed written consent for contribution and the study was approved by the research ethics committee for clinical studies at the faculty of pharmacy, Future University, Cairo, Egypt (No. of protocol: REC-FPSPI-2/17). All patients underwent cystoscopy as a standard reference for the identification of BC. The 12 healthy subjects served as control, were matched in sex and age with the BC group, and also, have no former history of any urological disorders.

Samples collection and preparation

Fresh urine samples were collected from each subject in sterile containers (cups) and centrifuged in sterile Wassermann tubes within one hour of collection at 16,000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature to remove cellular material and debris from samples. Clear supernatants were separated in sterile Wassermann tubes under laminar flow with a HEPA filter and stored at -80 Cº until analysis. Patient samples were taken in the morning at the time of diagnosis before receiving any medication.

RNA isolation and quantification

Total RNAs from urine supernatants were extracted using TRIzol® reagent (QIAamp Mini column, Qiagen, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. The concentration of the extracted RNA was measured using NanoDrop spectrophotometer.

Determination of urinary levels of BLACAT1 using quantitative PCR technique

Total extracted RNA was reversely transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript RT kit (Perfect Real Time, Takara, Holdings Inc., Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. BLACAT1 expression levels were performed by Real-time PCR assay technique using the following kits: TaqMan™ Non-coding RNA Assay kit, Catalog number: 4426961 provided by Applied Biosystems™ and master mix (TaqMan™ Fast Advanced Master Mix, Catalog number: 4444556, provided by Applied Biosystems™). The reaction volume used was 25 μL. Rotor gene-Q PCR machine (QIAGEN) detection system was used.

The thermo-cycling protocol was recorded as follows: First denaturation at 95˚C for 2 min, followed by 35 repeats of the three-step cycling program consisting of 30 s at 95˚C (denaturation), 1 min at 53˚C (primer annealing), and 30 s at 72˚C (elongation), followed by a final extension step for 10 min at 72˚C. The primer sequences used for qPCR are listed in (Table 1). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as the internal control. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The relative quantification of BLACAT1 was normalized to GAPDH and determined based on the cycle threshold (CT) level as reported previously [19].

Table 1.

Sequences of primers for BLACAT1 and housekeeping gene

| Gene | Sequences |

|---|---|

| BLACAT1 |

Sense: 5'-GTC TCT GCC CTT TTG AGC CT-3' Antisense: 5'-GTG GCT GCA GTG TCA TAC CT-3' |

| GAPDH |

Sense: 5'-GGG AAA CTG TGG CGT GAT-3' Antisense: 5'-GAG TGG GTG TCG CTG TTGA-3' |

BLACAT1 bladder cancer-associated transcript 1, GAPDH glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software was used to make the analyses (version 5.0). Quantification of data is represented as mean ± SEM. Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA were applied to estimate the statistical differences among different groups, where P < 0.05 was considered significant. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to differentiate between BC grades using MedCala 9.3.9.0 (MedCala, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Demographic data

All clinical and demographic data of patients and control are shown in (Table 2). It was observed that age was not significantly different between groups (P > 0.05). The mean age of BC patients at the time of diagnosis was 61.3 years. While healthy controls had a mean age of 50.5 years.

Urinary levels of BLACAT1 in primary and invasive stages:

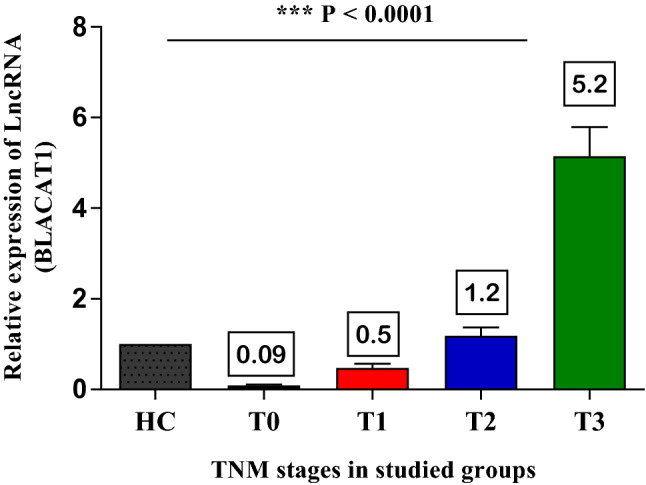

BLACAT1 was downregulated in superficial stages (T0 = 0.09 ± 0.02 and T1 = 0.5 ± 0.1) compared to healthy control. However, in invasive stages, its levels started to elevate in the T2 stage (1.2 ± 0. 2), and higher urinary levels were detected in the T3 stage with a mean value of 5.2 ± 0.6. This elevation was positively correlated with disease progression (Fig. 1) & (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

The relative expression levels of urinary BLACAT1 in BC Patients. The values were expressed as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.0001using ANOVA test

Table 3.

Urinary levels of BLACAT1 in bladder cancer patients

| Groups | Sample size (number) | Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy control (HC) | 12 | 1 |

| T0 | 12 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| T1 | 14 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| T2 | 24 | 1.2 ± 0. 2 |

| T3 | 20 | 5.2 ± 0.6 |

SEM standard error of the mean

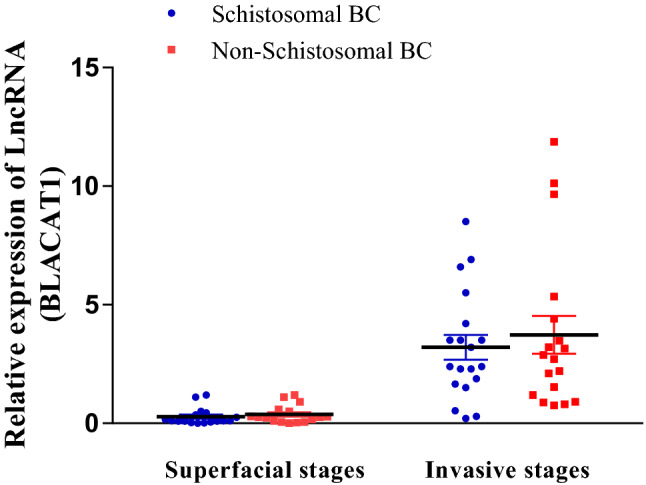

Urinary levels of BLACAT1 in schistosomal and non-schistosomal BCs

When comparing the urinary levels of BLACAT1 in schistosomal (37 cases) and non-schistosomal BC groups (33 cases); there was no significant difference between the two groups, where the superficial stages (T0 + T1) in schistosomal BCs showed expression levels of BLACAT1 (0.28 ± 0.08) compared to (0.38 ± 0.1) in non-schistosomal BCs. While the invasive stages (T2 + T3) were (3.2 ± 0.52) in schistosomal BCs compared to (3.7 ± 0.8) in non-schistosomal ones, as shown in (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The relative expression levels of urinary BLACAT1 in schistosomal and non-schistosomal BCs. P > 0.05 using unpaired t-test

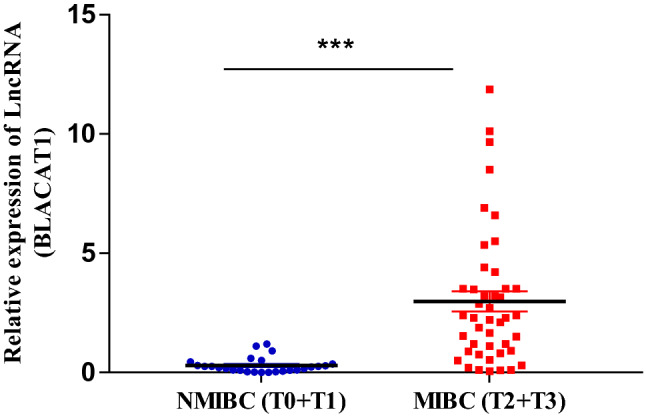

Urinary levels of BLACAT1 in NMIBC (T0 + T1) and MIBC (T2 + T3):

We evaluated the urinary levels of BLACAT1 in a NMIBC group (T0 + T1, no = 26) and MIBC group (T2 + T3, no = 44) group (Fig. 3), and found that, BLACAT1 demonstrated high expression levels in the muscle-invasive (MIBC) group (2.98 ± 0.43) compared to non- muscle-invasive (NMIBC) group (0.3 ± 0.06) at p < 0.0001.

Fig. 3.

The relative expression levels of urinary BLACAT1 in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) groups. ***P < 0.0001using unpaired t-test

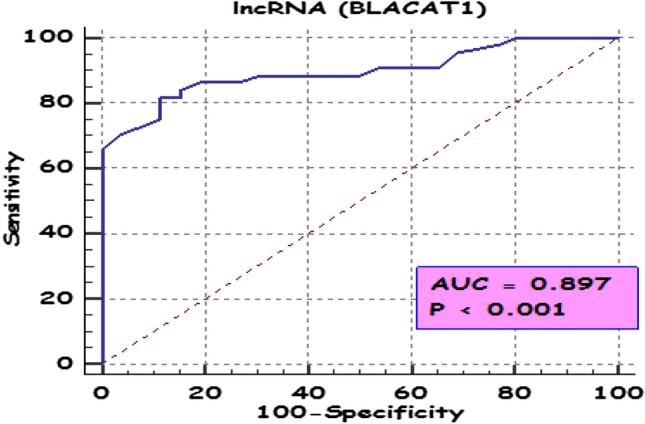

Diagnostic performance of BLACAT1 in bladder cancer detection:

ROC analysis was performed to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of BLACAT1 as a diagnostic marker in BC patients, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.52 with very high specificity (100%) and low sensitivity (51.4%). Furthermore, to evaluate the power of differentiating NMIBC patients from MIBC patients, the ROC curve was calculated (Fig. 4). BLACAT1 demonstrated AUC values higher than 0.89 (p < 0.001) with overall sensitivity and specificity of 81.82 and 88.46% respectively, indicating higher performance to differentiate NMIBC patients from MIBC patients.

Fig. 4.

ROC curve of BLACAT1 to differentiate between non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) in the studied groups

Discussion

Bladder cancer (BC) is among the most fatal types of cancers worldwide [1]. Its aggressive type (MIBC) accounts for around 25% of all primarily diagnosed BC cases and 50% of patients die from metastatic disease even with the best therapeutic option [20, 21]. lncRNAs are a new class of gene managers in many cancer types [22]. They play important roles in an extensive range of biological processes among cancerous cells and might be involved in oncogenesis and tumor suppression [6, 23]. Additionally, lncRNAs also regulate the sensitivity of chemotherapy and radiotherapy of cancer cells [24].

BLACAT1, is branded as a new budding star, for a valuable and potential prognostic prediction for cancers [15, 16]. Our study revealed the BLACAT1upregulation of urinary BLACAT1 in BC patients with higher TNM staging. Previous studies detected the upregulation of BLACAT1 in BC tissues by more than1.5-fold, and this was associated with cell proliferation and migration in three BC cell lines (UMUC-3, TCCSUP, and 5637) [12, 25].

Furthermore, elevated expression of BLACAT1 was associated with metastasis and higher tumor staging in breast cancer tissues and its downregulation decreased cell migration in SKBR3 and MDA-MB-231 cells with miR-150-5p overexpression [26]. Also, Depletion suppresses cell metastasis in ME180 and C33A cells were explored with Trans-well assay and wound-healing analysis [27].

The site of lncRNAs inside the cells often revealed their functions [25]. BLACAT1 was enriched in the nucleus [22], it collaborated with the enhancer of zeste 2 (EZH2) and suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12), which were important modules of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), to modify the expression of some target genes [25]. Furthermore, the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay showed that BLACAT1 could modify histone H3-lysine 27 (H3K27) tri-methylation level in the promoter regions of some genes, revealing its oncogenic role in BCs [12].

Our study is considered to be unique in the detection of BLACAT1 expression levels in urine samples as non-invasive samples of BC patients. Numerous studies reported the upregulation of BLACAT1 in the tissue of many types of cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, glioma, and osteosarcoma. Conversely, lower expression of BLACAT1 was identified in normal tissues and the patient sera [24, 25].

Moreover, elevated BLACAT1 expression was positively correlated with higher TNM staging, and patients with high BLACAT1 expression were inclined to have a shorter overall survival [16]. Depletion of BLACAT1 negatively affected cell proliferation, invasion, and migration in cervical cancer ME180 and C33A cells [27]. Likewise, Droop et al. also reported elevated BLACAT1 expression in cancer tissues than in adjacent normal tissues, and this up-regulation was significantly related to poor survival in the cohort of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) BCs [28]. On the other hand, there was no apparent difference detected in the BLACAT1 expression between tumor and benign tissues, and no significant association was found between metastasis and survival [25, 28]. This variation might be due to heterogeneity in patient populations, or difference in the detection techniques used. So, our study is considered to be a valuable unique one that detects a difference in urinary levels between patients and healthy people.

The present study was also unique in detecting BLACAT1 expression in schistosomal BC patients although there was no significant variation in the levels of BLACAT1 between schistosomal and non- schistosomal BC patients. Controversy, Hammam et al. determined the expression of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR3) gene in Egyptian BC patients and found that FGFR3 was significantly associated with schistosomal BC tumor grade and stage [29].

Our results demonstrated up-regulation of urinary BLACAT1 in invasive BC stages (T2 + T3). This agrees with the results from Gao et al. who reported increased expression of BLACAT1 in colorectal cancer tissues and this expression was more obviously expressed in CRC patients with greater tumor size, deeper tumor invasion, higher TNM stage, and more lymph node metastasis [13].

Different types of urinary BCs biomarkers were discussed before, such as the classical FDA-approved proteins, genetic and epigenetic biomarkers [30], and exosomal markers [30, 31].

When comparing our marker with urinary miRNAs measured in BCs patients, we found that lncRNA BLACAT1 measured in the current study has higher sensitivity and specificity (81.82 and 88.46% respectively) as a diagnostic marker in the invasive stage (IMBC) while miRNAs included in the study of K.Ng et al., had high sensitivity and specificity (80% and more) in the non-invasive stage (NIMBC) [30]. So, urinary lncRNA BLACAT1 in the current study may be considered a unique metastatic biomarker and can be used to differentiate between invasive and non-invasive bladder cancer stages. Furthermore, its predictive values are not like to be influenced by Schistosoma infection. Therefore, lncRNA BLACAT1 is a promising prognostic biomarker for BCs.

In conclusion, we can conclude that BLACAT1 may be considered one of the promising non-invasive metastatic biomarker for bladder cancer.

Authors’ contributions

FE and HK designed the study. Material preparation, sample collection, and analysis of the experiments were performed by ME. Statistical analysis and the first draft of the manuscript were written by HA and revised by FE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). No funds, grants, or other support were received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests that are directly or indirectly related to this work.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the research ethics committee for clinical studies at the faculty of pharmacy, Future University, Cairo, Egypt (No. of protocol: REC-FPSPI-2/17).

Consent to participate

Written Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fathia Z. El Sharkawi, Email: Fathia.elsharkawy@pharm.helwan.edu.eg

Mahmoud El Sabah, Email: mahmoud.elsabah@yahoo.com.

Hanaa B. Atya, Email: hanaa.atya@pharm.helwan.edu.eg

Hussein M. Khaled, Email: Khaledh@cu.edu.eg

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods, and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Compérat EM, Hernández V, Kaasinen E, Palou J, Rouprêt M, van Rhijn BWG, Shariat SF, Soukup V, Sylvester RJ, Zigeuner R. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):447–461. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du L, Duan W, Jiang X, Zhao L, Li J, Wang R, Yan S, Xie Y, Yan K, Wang Q, Wang L, Yang Y, Wang C. Cell-free lncRNA expression signatures in urine serve as novel non-invasive biomarkers for diagnosis and recurrence prediction of bladder cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(5):2838–2845. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terracciano D, Ferro M, Terreri S, Lucarelli G, D'Elia C, Musi G, de Cobelli O, Mirone V, Cimmino A. Urinary long noncoding RNAs in nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer: new architects in cancer prognostic biomarkers. Transl Res. 2017;184:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui Liu, H. Liu, Junyun Luo, J. Luo, Siyu Luan, S. Luan, Chongsheng He, C. He, & Zhaoyong Li, Z. Li. (0000). Long non-coding RNAs involved in cancer metabolic reprogramming. Cellular and molecular life sciences, 76, 495–504. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-018-2946-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Qiu JJ, Lin XJ, Tang XY, et al. Exosomal metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 promotes angiogenesis and predicts poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(14):1960–1973. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.28048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Yu Y, Li H, Hu Q, Chen X, He Y, Xue C, Ren F, Ren Z, Li J, Liu L, Duan Z, Cui G, Sun R. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 promotes tumor progression by regulating the miR-143/HK2 axis in gallbladder cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0947-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ou ZL, Zhang M, Ji LD, Luo Z, Han T, Lu YB, Li YX. Long noncoding RNA FEZF1-AS1 predicts poor prognosis and modulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion through miR-142/HIF-1α and miR-133a/EGFR upon hypoxia/normoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jcp.28188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Z, Wang Y, Tang J, 2018. High LINC01605 expression predicts poor prognosis and promotes tumor progression via up-regulation of MMP9 in bladder cancer. Biosci Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 11.Li Z, Hong S, Liu Z. LncRNA LINC00641 predicts prognosis and inhibits bladder cancer progression through miR-197-3p/KLF10/PTEN/PI3K/AKT cascade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(3):1825–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He W, Cai Q, Sun F, Zhong G, Wang P, Liu H, Luo J, Yu H, Huang J, Lin T. linc-UBC1 physically associates with polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and acts as a negative prognostic factor for lymph node metastasis and survival in bladder cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(10):1528–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Wen J, Gao P, Zhang G, Zhang G. Overexpression of the long non-coding RNA, linc-UBC1, is associated with poor prognosis and facilitates cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in colorectal cancer. Once Targets Ther. 2017;10:1017–1026. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S129343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Y, Pan J, Wang Y, Li L, Huang Y. Long noncoding RNA linc-UBC1 is a negative prognostic factor and exhibits tumor pro-oncogenic activity in gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(1):594–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Hang Y, Xu W, et al. BLACAT1 predicts poor prognosis and serves as oncogenic lncRNA in small-cell lung cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018 doi: 10.1002/jcb.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu H, Liu H, Yang X, Ye T, Lv P, Wu X, Ye Z. LncRNA BLACAT1 may serve as a prognostic predictor in cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1275491. doi: 10.1155/2019/1275491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanli O, Dobruch J, Knowles MA, Burger M, Alemozaffar M, Nielsen ME, Lotan Y. Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;13(3):17022. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 7. New York: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lobo N, Mount C, Omar K, Nair R, Thurairaja R, Khan MS. Landmarks in the treatment of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14(9):565–574. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minoli M, Kiener M, Thalmann GN, Kruithof-de Julio M, Seiler R. Evolution of urothelial bladder cancer in the context of molecular classifications. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5670. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi C, Sun L, Song Y (2019) FEZF1-AS1: a novel vital oncogenic lncRNA in multiple human malignancies. Biosci Rep 39(6):BSR20191202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sherstyuk VV, Medvedev SP, Zakian SM. Noncoding RNAs in the regulation of pluripotency and reprogramming. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2018;14(1):58–70. doi: 10.1007/s12015-017-9782-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Dai M, Zhu H, Li J, Huang Z, Liu X, Huang Y, Chen J, Dai S. Evaluation on the diagnostic and prognostic values of long non-coding RNA BLACAT1 in common types of human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0728-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye T, Yang X, Liu H, Lv P, Ye Z. Long non-coding RNA BLACAT1 in human cancers. Once Targets Ther. 2020;20(13):8263–8272. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S261461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X, Liu Y, Du Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA BLACAT1 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis by miR-150-5p/CCR2. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:14. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shan D, Shang Y, Hu T. Long noncoding RNA BLACAT1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in human cervical cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(3):3490–3495. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Droop J, Szarvas T, Schulz WA, Niedworok C, Niegisch G, Scheckenbach K, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of long noncoding RNAs as biomarkers in urothelial carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0176287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammam O, Aboushousha T, El-Hindawi A, et al. Expression of FGFR3 protein and gene amplification in urinary bladder lesions about schistosomiasis. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(2):160–166. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2017.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng K, Stenzl A, Sharma A, Vasdev N. Urinary biomarkers in bladder cancer: a review of the current landscape and future directions. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elsharkawi F, Elsabah M, Shabayek M, Khaled H. Urine and serum exosomes as novel biomarkers in detection of bladder cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(7):2219–2224. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.7.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Qin Z, Wang Y, Tang J, 2018. High LINC01605 expression predicts poor prognosis and promotes tumor progression via up-regulation of MMP9 in bladder cancer. Biosci Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.