Abstract

Heat shock proteins (HSPs), which have a variety of functions, are one of the stress protein families. In recent years, They have been reported to play a dual role in hepatitis B virus (HBV) which as persistent infection which is associated with, cirrhosis and liver cancer. In this article, we have summarized the regulatory mechanisms between HSPs and viruses, especially HBV and associated diseases based on HSP biological functions of in response to viral infections. In view of their potential as broad-spectrum antiviral targets, we have also discuss current progress and challenges in drug development based on HSPs, as well as the potential applications of agents that have been evaluated clinically in HBV treatment.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, HSPs, Antiviral, Vaccine adjuvant, Molecular chaperones

1. Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are ubiquitous in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes and an esential component of cell growth and survival with a 60-78% homology level. They are rapidly expressed during various conditions such as cell insult, high temperature, oxidative stress, infection, tumors and other similar conditions. HSPs are categorized divided into several families such as HSP110 family, HSP90 family, HSP70/110 family, HSP60 family, HSP40, family and small molecule family (sHSP) according to their relative molecular function and mass. They have been widely studied in many viruses, but rarely in hepatitis B virus (HBV). During replication, RNA precursors are used as templates for reverse transcription to produce offspring HBV DNA. This enzymatic process cannot correct the nucleotide mismatch during replication, and as a consequence HBV is more likely to mutate compared to other DNA viruses. Reverse transcription is a complex process that requires the involvement of many cellular regulatory proteins, which include sHSPs among other HSPs.

Heat shock proteins play an important role in the interaction between reverse transcriptase (P protein) and the RNA packaging signal (ε) on pre-genomic RNA during HBV replication. HSP70 can activate the P-ε complex together with ATP, while Hsp90 can significantly enhance the activity of the P protein.1,2

The main treatment for HBV nowadays consists of antiviral drugs to inhibit replication, but rarely leads to functional cure. In this article, we will highlight the antiviral effects of HSPs family members such as HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, and small HSPs (sHSPs).

2. HSPs)in viral infections and immune responses

The HSP110 family proteins are adjuvants which can activate effector cells and initiate immune responses. HspBP1 is a member of this family, its overexpression being able to increase the the RIG-I protein stability by inhibiting its K48-linked ubiquitination, and promote IRF3 activation and interferon-β production induced by the Sendai virus.3 The HSP90 family proteins can interact with cellular functional proteins, such as protein kinases and steroid hormone receptors, to form a complex that takes part into cell division, immunity and signal transduction. Its member, Hsp90B1 (Grp94) is the key regulator for the HBV RNA polymerase stabilization and activation, while Hsp90 can stabilize VP5, the major capsid protein of the pseudorabies virus, which is beneficial to the viral assembly and replication process.4 The research into the HSP70 family has mainly been focused on cell tolerance and protection against a harmful environment, cellular immunity, innate immune response, anti-oxidation, anti-apoptosis and as a molecular chaperone. It can also regulate protein folding and changes. Its member, HSPA5(Grp78), can be expressed upon induction of the E protein of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus.5 Another family member, Hsp70, can interact with the measles virus N protein to impact viral replication.6 Another family member, Hsc70 (HSPA8), can bind to the polyomavirus major capsid protein VP1 and promote capsid assembly.7 The HSP60 family proteins can promote protein folding, transport, and are involved in DNA metabolism. The HSP40 family proteins can suppress the process of protein aggregation. HIV-1 nef is dependent on Hsp40 induction, with increased Hsp40 translocation into the nucleus of infected cells.8 As a molecular chaperone, the sHSPs can prevent unnecessary interactions between proteins, help the refolding of denatured proteins, stabilize cytoskeleton, and take part into events such as cell injury and repair. Its member, HSPB1, can interact with VP2, the foot and mouth disease virus capsid protein, activate the EIF2S1-ATF4 pathway, which leads to viral replication.9 A further summary of HSP family members in the context of viral infections is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular function of heat shock proteins (HSPs) and interacting proteins in viral infections.

| HSP Family | Members | Location | Molecular function in viral infections | Interacting proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP110 | HspBP1 | Cytoplasm | Knockdown would reduce viral production. Endogenous negative regulator of HIV-1 gene expression and replication. |

RIG-I |

| HSP90 | Hsp90B1 (Grp94) | Endoplasmic reticulum | Regulation of viral protein homeostasis. Preservation of the balance between viral and cellular translation. Prevention of viral protein overload. |

HBV RNA polymerase |

| HSP90 | Hsp90 | Cytoplasm | Folding and assembly of capsid proteins of various picornaviruses. Assembly and nuclear transport of viral RNA polymerase subunits during influenza virus infection. Reverse transcription of hepatitis B (HBV) genome. Early E1A protein of adenovirus 5 essential for viral replication. Promotes HBV replication. |

VP5 |

| HSP70 | HSPA5 (Grp78) |

Endoplasmic reticulum | Reduced production of viral particles. Important role in viral binding to host cell membrane and entry for several flaviruses such as dengue, Zika and Japanese encephalitis viruses. |

E protein of PEDV |

| HSP70 | Hsp70 | Cytoplasm | Interaction with nucleocapsid of canine distemper virus, measles virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and rabies virus. Promotes or inhibits HBV replication. |

N protein of the measles virus |

| HSP70 | Hsc70 (HSPA8) | Cytoplasm | Crucial role in viral genome replication, viral protein abundance, budding virus production at early infection stage. | VP1 |

| HSP60 | Hsp60 | Mitochondria | Activation of HBV polymerase before embedding into core particles initiates HBV replication in newly-infected cells. | HBV Pol |

| HSP40 | Hsp40 | Cytoplasm | Viral RNA replication. Regulation of viral gene expression.. |

HIV-1 nef |

| Small HSPs | HSPB1 | Cytoplasm | Inhibits HBV replication. Up-regulated in response to enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection at the protein level. |

VP2 |

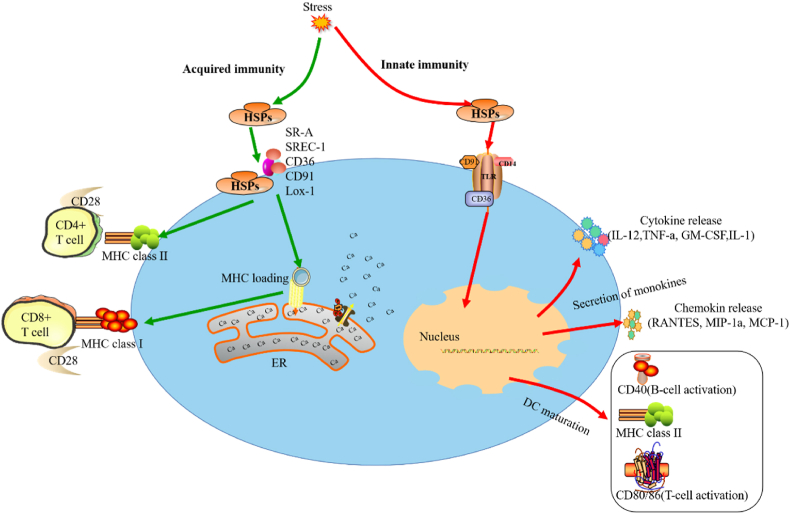

Heat shock proteins are non-specific, chemical and biological molecules which respond to stimuli, such as heat, harmful metal ions, viral or bacterial infections. In addition, the various HSPs have different synthesis and degradation kinetic characteristics (Fig. 1).10, 11, 12

Fig. 1.

HSPs are involved in acquired immunity, monokines and maturation of dendritic cells (DCs), and provide peptides for MHC-loading and antigen-specific responses.

3. HSPs and HBV infection

3.1. HSP90 promotes HBV viral capsid assembly through the reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathway

The molecular weight of the HSP90 family is about 90kD, mainly in the form of dimer. Its activity is controlled by adenosine triphosphaet (ATP) and regulated by post-translational changes such as phosphorylation and acetylation. HSP90 mainly binds to unstable and inactive cellular proteins, promoting their activation or preventing their degradation. It is also involved in cell division, immunity, and signaling.

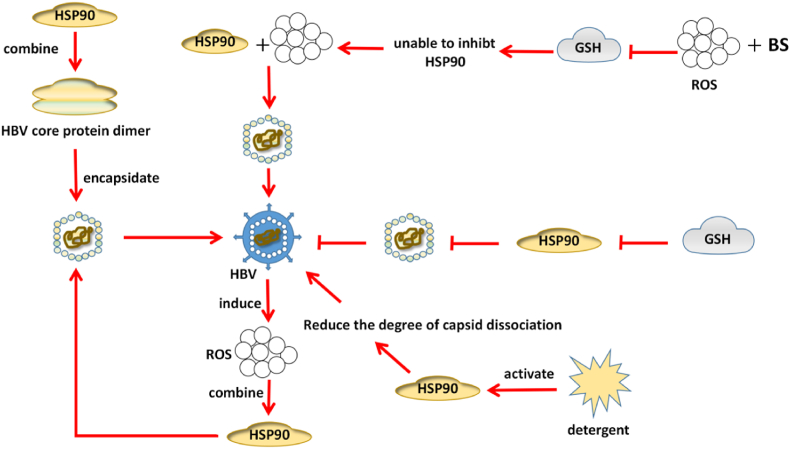

When using the replicating HBV cell line HepG2.2.15, HSP90 is shown not only to participate in HBV replication, but also to promote the cell line proliferation. After HSP90 overexpression, levels of HBV total mRNA and 3.5 kb mRNA are increased, and HBV 3.5 kb mRNA includes the HBV genetic information and is a template for HBV replication, indicating that overexpression of HSP90 can promote replication. Stable overexpressed HSP90 cell lines were constructed in HBV stably replicating cell lines to examine the cellular proliferative capacity in the control versus the HSP90 overexpression groups. Compared with the control group, HSP90 overexpression could promote the proliferative ability of Hep G2.2.15 cells.13 Further research has shown that the HSP90 inhibitor can prevent viral RNA and DNA packaging by inhibiting the HBV polymerase, thereby preventing HBV replication.14,15 Liu et al.16 have found that the down-regulation of HSP70 or HSP90 by small interfering RNAs can significantly inhibit HBV production, but has no effect on cell proliferation or apoptosis. Some research suggests that 17 HSP90 can link up with the HBV core protein dimer in the process of capsid formation. Activation of HSP90 can promote HBV capsid formation by catalyzing core assembly and reducing the degree of capsid dissociation when treated with detergent.

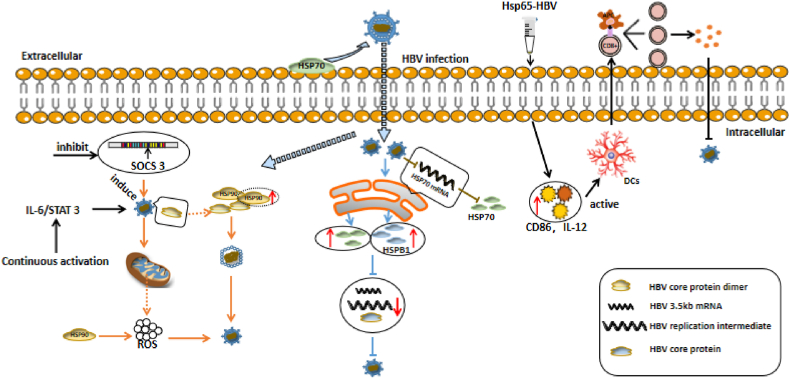

The eactive oxygen species formation induced by HBV infection is linked to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), because its accumulation leads to abnormal cell proliferation and chromosomal mutations. HSP90 and glutathione (GSH) are part of the defense mechanisms in oxidative stress. HSP90 can prevent oxidative stress of cell components, while GSH acts as an antioxidant to remove cellular ROS. Some authors have described that, consistent with the results of cell-free systems, buthionine sulfoximine (BS), an inhibitor of ROS and GSH synthesis, increased HBV capsid formation in HepG2 2.15 cells.18 It also indicates that ROS and GSH could be used to inhibit HBV replication and proliferation with HSP90 as molecular target for therapeutic purposes. The accumulation of mitochondrial ROS induced by HBV is caused by SOCS 3 inhibition and the chronic activation of the IL-6/STAT 3 pathway in hepatoma cells which leads to HBV production (Fig. 2).19

Fig. 2.

Hsp90 interacts with reactive oxygen species (ROS) to promote hepatitis B (HBV) viral capsid assembly, suppresses replication upon glutathione (GSH), and promotes replication after GSH inhibition.

3.2. How to understand the promotion and inhibition of HSP70 in HBV infection?

HSP70 is located in the endoplasmic reticulum and participates in protein folding and assembly. It can promote virus attachment to the cell surface and entry into host cells.

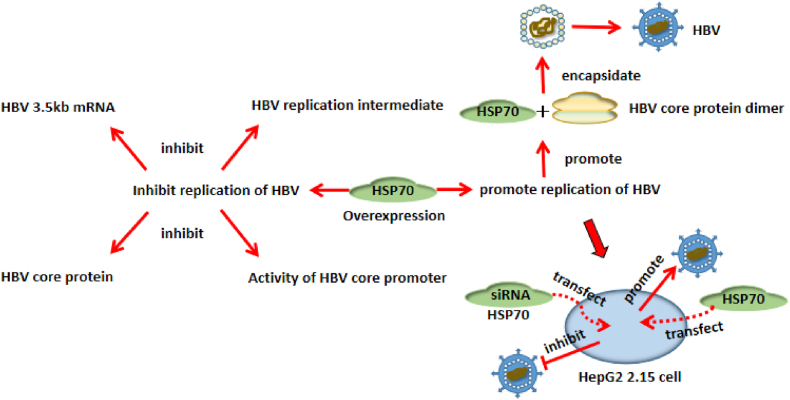

Cell experiments have shown that HBV replication inhibits HSP70 mRNA levels, while overexpressed HSP70 also inhibits the expression of the HBV replication intermediate, 3.5 kb mRNA, HBV core protein, and the HBV core promoter activity.20 Serum HSP70 expression levels in chronic hepatitis B (CHB ) and healthy control groups were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Serum HBV DNA replication levels in CHB were analyzed by quantitative PCR. Results showed that HSP70 was highly expressed in CHB compared with healthy controls and this was positively correlated with HBV DNA copy numbers. However, after using RNA interference technology to inhibit HSP70 gene expression in HBV-infected cells, and when analyzing the expression of HBV-DNA and related antigens in the supernatant of cell culture, it was found that the DNA copy number and related antigens in the supernatant decreased significantly. HSP70 may also inhibit HBV replication by impacting negatively on the activity of Cp, the core promoter. However, if exogenous HSP70 is introduced into HepG2 2.15 cells which stably express HBV,the HSP70 gene gets highly expressed, and cellular HBV replication is increased by 1.8 fold. If specific HSP70 siRNAs are transfected into HepG2 2.15 cells, HBV replication becomes significantly reduced without cytotoxicity.21,22 Regarding the specific pathway of HSP70 acting on HBV, some researches have shown that HSP70 binds to the HBV core protein dimer to promote capsid assembly. HSP70 inhibition by methylene blue leads to reduced capsid assembly, which further leads to a decrease in virus particles.23 As to whether HSP70 can promote or inhibit HBV replication, we have hypothesized that a given degree of HSP70 overexpression inhibits HBV replication, but, if too high, it may promote HBV replication (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of Hsp70 promotes both hepatitis B (HBV) replication and suppression.

High expression of HSPA4L, HSPA6 and HSPA13 from the HSP70 family can promote to some extent hepato-cellular carcinoma (HCC) growth. The HSPA4L and HSPA1B expression is related to some of HCC pathological features related to HBV infection, and has predictive value for some of its characteristics such as tumor hyperplasia and multiple nodules, which may become a therapeutic target and prognostic predictor for HCC.24 In addition, the HSP gene C-terminal truncated fragment can also enhance HBV DNA vaccine efficacy.25,26

3.2.1. HSP60 affects HBV infection by regulating HBV-associated proteins

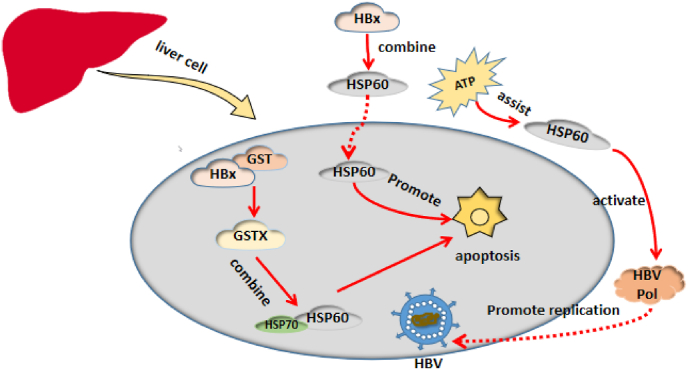

HSP60 is located inside and on the surface of mitochondria and cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, and also in the extracellular space and peripheral blood. It is is involved in the regulation of the immune system and plays an important role in the development of stress-related immune responses. HBcAg-specific regulatory T regulatory cells play an important role in CHB pathogenesis. Soluble HSPs, especially the soluble heat shock proteins 60 (sHSP60), can enhance the function of HBcAg-specific T regulatory cells through toll-like receptors.27

HSP60 actives the HBV polymerase (HBV Pol) by binding to it through amino acids 1 to 199 (TP) and 680 to 842 (RH),28 which have a strong influence on HBV Pol. In vitro activity of HBV Pol decreased after HSP60 was blocked by protein-specific antibodies while, ATP cooperated with HSP60 to activate human HBV Pol. In vivo experiments have shown that HSP60 inhibition by the HSP60C Delta 540 mutant resulted in the decrease of human HBV Pol activity29 demonstrating the pivotal role of HSP60 in HBV infection.

HBx (hepatitis B virus X protein) is the transcriptional transactivator necessary for viral infection. It plays an important role in CHB progression to liver cirrhosis and HCC.30 HBx can directly or indirectly alter liver cell structure and function and induce cell apoptosis.31 It needs binding to host cell proteins to exert its function. During the purification of GSTX (GST and HBx fusion protein) expressed in E coli, we have found that it can bind specifically to GrpE (HSP60) and DnaK (HSP70) of E. coli while GST cannot. Zhang et al. have found that GSTX can also bind to human mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP70, which are GrpE and DnaK homologues.32 Another study has described that HBx specifically binds to HSP60 in E. coli,33 and that introducing HSP60 into cells could promote the apoptosis of normal hepatocytes.34 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hsp60 impacts on hepatitis B (HBV) replication and hepatocyte apoptosis by its interaction with HBV pol and HBV virus X protein (HBx).

3.3. Overexpression of HSPB1 inhibits HBV replication

sSgnificant expression of small heat shock proteins often occurs when cell are stimulated by external stimuli, such as high temperature or ultraviolet rays, and importantly in response to stress. These molecules can protect nerve cells, and are also closely related to the tumor development, and cardio-vascular and cytoskeleton diseases.

HSPB1 is the most widely distributed and mainly located in the cytoplasm, but also in endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus and other organelles. It has been found to be involved in herpes simplex virus type I35 human adenovirus E37,36 hepatitis C virus 37 and porcine circovirus type 2.38

Harimoto et al. have described that HBV-related liver cancer with high HSPB1 expression had a poor prognosis.39 Furthermore, this molecule may be a potential marker of liver cancer and is closely related to its clinical stage and prognosis.40 Cheng et al. have expressed HSPB1 in HBV replication cell lines and found that it inhibits HBV replication by down-regulating the level of HBV 3.5 kb mRNA and replication intermediates, which indicates that this HSP can impact on HBV life cycle by altering viral replication level, and this in turn may alter HBV progression towards the disease stage.41 The results by Cheng et al are different to those by Harimoto et al, this possibly due to a smaller number of participants, particularly those with HCC in the study by Harimoto et al. Others have checked on the relationship between HBV replication and HSPB1, and found that this molecule acts as an antiviral protein during HBV infection by specifically inducing interferon and downstream antiviral effectors.42

HSPB1 is also involved in regulating cellular oxidative stress.43 Poussard et al., have found that oligopin, a natural antioxidant, can reduce oxidative damage of skeletal muscle cells by regulating HSP1 expression,44 and some research has found that ROS accumulation occurs after targeted HSB1 silencing with interfering RNAs.45 HSPB1, like HSP90, therefore can influence HBV replication through the oxidative stress process.

4. Potential value of the HSPs family in HBV treatment

HBV infection is prevalent all over the world and represent a heavy social and public health burden and therefore justifies the present efforts towards its eradication. Based on CHB immunopathogenic mechanisms, immunotherapy has become a hot topic. CAR-T cell immunotherapy is a promising treatment method for targeting HBV-infected hepatocytes, but it remains unclear whether it can improve cellular immunity in order to achieve complete and lasting viral clearance. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) immunotherapy can effectively improve Th1/Th2 cell function. Many types of immunotherapies have been tested in various animal models, but only a few have entered into the clinical trial stage. At present, efforts are made to induce HBV-specific immune responses.46 Therapeutic vaccines, including proteins (HBsAg/preS and HBc Ag), DNA and those based on viral vectors, can induce and boost HBV-specific immune responses. Protein/polypeptide vaccines, such as the HBsAg/HBcAg composite vaccine, can induce specific and multifunctional T cells in HBV-Tg mice, especially HBV-specific CD8+T cells, which stimuate IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2 in vivo. After DNA vaccine intramuscular or intradermal injection, muscle cells and antigen presenting cells can process DNA, express HBsAg and HBcAg in situ, and present them to host immune cells, together with HBV-specific B and T cell activation. Furthermore, vaccines based on viral vectors, such as the vesicular stomatitis virus, have a significant impact on T cell induction,47 but with associated hepatotoxicity. This method aims to enhance HBV-specific T cells in CHB but with the inherent risk of inducing serious liver toxicity.

Among the various kinds of therapeutic vaccines, we suggest that a protein/polypeptide vaccine should be the first choice, with HSP as an adjuvant in HBV.

The chimeric protein Hsp65-HBV is expressed by fusing PADRE and HBV to the carboxyl terminal of BCG Hsp65 to E. coli. It was found that Hsp65-HBV can activate human dendritic cells (DCs) by up-regulating HLA-A2, HLA-DR and CD86 expression, with subsequent high levels of IL-12. In addition, these mature DCs can significantly stimulate the proliferation of human autologous CD8+ T cells and induce HBV-specific cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). Hsp65-HBV has been shown to generate HBsAg-specific CTLs in mice indicating that that Hsp65-HBV may be a candidate for the treatment of CBV.48

When HSPgp96 was combined with viral or tumor-derived antigens, it could induce CTLs restricted by MHC class I, making this molecule a powerful adjuvant for CD8+ T cells. Gp96 or its N- terminal fragment as an adjuvant has the ability to enhance HBV-specific CTL responses. Two antigens with strong immunogenicity towards HBsAg and HBcAg and with gp96 as adjuvant were selected as therapeutic vaccine generating strong antiviral T and B cells against these antigens. Compared with the control group, the the gp96 adjuvanted vaccine reduced serum HBs and HBc expression in hepatocytes by 45% and 90%, respectively, as well as levels of serum HBV DNA by more than 1000 fold. Gp96 can also partially enhance antiviral immunity in HBV transgenic mice by down-regulating T regulatory cells. Therefore, the HBsAg-HBcAg combination formula based on gp96 seems to be a promising candidate for developing a therapeutic HBV vaccine.49

Vaccines based on immunogenic peptides can boost cellular immune responses. However, these peptide-based vaccines are problematic because of their low CTL epitope immunogenicity, and as a result T helper cell epitopes and adjuvants are usually needed to stimulate CTLs effectively. Mycobacterium tuberculosis heat shock protein 70 (TBhsp70) can overcome this problem with an effective adjuvant connecting innate and adaptive immunity. By fusing the HBV core 18–27 peptide (HBcAg (18–27)) and CTL epitope gene to the C-terminal of TBhsp70 to form a fusion protein of theTBhsp70 peptide, and by recombining TBhsp70-HBcAg (18–27) peptide complex in vitro, the vaccines can stimulate immune responses and TNF by up-regulating CD40 and CD86. In addition, the two vaccines can stimulate DCs and autologous T cells to produce HBV-specific CTL responses. Therefore, TBhsp70 could provide a new design concept for the development of preventive and therapeutic vaccines.50

In conclusion the ultimate goal of CHB immunotherapy is to achieve HBV control, with HSPs may play a significant role as adjuvants in the development of effective therapeutic vaccines for HBV in the future (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Role of the heat shock protein (HSP) family in hepatitis B (HBV) infection and immune clearance mechanisms.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Yuzhong District of Chongqing City, 2020050, and the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Foundation, KJQN202000403, and the General Project of Chongqing Natural Science Foundation, cstc2021jcyj-msxmX0095, and Chongqing Medical University Undergraduate Innovation Experiment Project (approval numbers LTMC202103 and LTMCMTS202121). We gratefully thank the American Journal Experts for editing this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ming-qi Lv, Email: 510367620@qq.com.

Ting-ting Chen, Email: cherrychen@cqmu.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Stahl M., Retzlaff M., Nassal M., Beck J. Chaperone activation of the hepadnaviral reverse transcriptase for template RNA binding is established by the Hsp70 and stimulated by the Hsp90 system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(18):6124–6136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y-y. Hubei University Of Technology; 2016. Study on Anti-HBV Drugs Targeting Heat Shock Protein. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y.-X., Huang J.-P., Li S.-N., Li J., Ling T., Xie T., Xu L.-G. HSPBP1 facilitates cellular RLR-mediated antiviral response by inhibiting the K48-linked ubiquitination of RIG-I. Mol Immunol. 2021;134:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W.J., Wang R.Q., Li L.T., Fu W., Chen H.C., Liu Z.F. Hsp90 is involved in pseudorabies virus virion assembly via stabilizing major capsid protein VP5. Virology. 2021;553:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X-h, Xu W-h, Zhang X-l, Ma D-y, Lei Y-f, Zheng L., Guo D-x, Wu Z-j, Zhang H., Cao H-w. Effect of PEDV protein on expression of GRP78, the key protein of UPR response in host cells. J Heilongjiang Bayi Agric Univ. 2021;33(4):60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahaye X., Vidy A., Fouquet B., Blondel D. Hsp70 protein positively regulates rabies virus infection. J Virol. 2012;86(9):4743–4751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06501-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chromy L.R., Pipas J.M., Garcea R.L. Chaperone-mediated in vitro assembly of Polyomavirus capsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(18):10477–10482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832245100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar M., Mitra D. Heat shock protein 40 is necessary for human immunodeficiency virus-1 nef-mediated enhancement of viral gene expression and replication. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(48):40041–40050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun P., Zhang S., Qin X., Chang X., Cui X., Li H., Zhang S., Gao H., Wang P., Zhang Z., Luo J., Li Z. Foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid protein VP2 activates the cellular EIF2S1-ATF4 pathway and induces autophagy via HSPB1. Autophagy. 2018;14(2):336–346. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1405187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker J., Craig E.A. Heat-shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219(1-2):11–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79502-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locke M., Noble E.G. Stress proteins: the exercise response. Can J Appl Physiol. 1995;20(2):155–167. doi: 10.1139/h95-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun P-m, Li Y-b, Wang Z-l, Bao E-d. Myocardial damage and localization of heat shock proteins in broilers under heat stress Myocardial damage and localization of heat shock proteins in broilers under heat stress. J Nanjing Agric Univ. 2005;(1):131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y-h, Ren L., Hou Y-w, Chang J. Effect of heat shock protein 90(HSP90) on HBV replication. Port Health Control. 2018;23(1):37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng X-r, Wan B., Zhang W., Zhang X-w. Research progress of HSP90 and its inhibitors in diseases. Int J Respir. 2020;40(11):871–874. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin L-m. Fujian Medical University (FJMU); 2018. Hsp90 Inhibitor Inhibits HBV Replication by Degrading Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein HBc. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu K., Qian L., Wang J., Li W., Deng X., Chen X., Sun W., Wei H., Qian X., Jiang Y., He F. Two-dimensional blue native/SDS-PAGE analysis reveals heat shock protein chaperone machinery involved in hepatitis B virus production in HepG2.2.15 cells. Mol Cell Proteomics : MCP. 2009;8(3):495–505. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800250-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shim H.Y., Quan X., Yi Y.-S., Jung G. Heat shock protein 90 facilitates formation of the HBV capsid via interacting with the HBV core protein dimers. Virology. 2011;410(1):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y.S., Seo H.W., Jung G. Reactive oxygen species promote heat shock protein 90-mediated HBV capsid assembly. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;457(3):328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan K., Lei Y., Chen H.N., Chen Y., Zhang T., Li K., Xie N., Wang K., Feng X., Pu Q., Yang W., Wu M., Xiang R., Nice E.C., Wei Y., Huang C. HBV-induced ROS accumulation promotes hepatocarcinogenesis through Snail-mediated epigenetic silencing of SOCS3. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(4):616–627. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H-z, Liu B., Ren J-h, Tao N-n, Chen X., Li W-w, Chen J. Effect of heat shock protein 70 on HBV replication. Chin J Pathophysiol. 2016;32(8):1425–1429. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y-p. Peking Union Medical College; 2009. Hsc70 Protein: Theory and Practice of Anti-HBV Drug Resistance. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rong H-y, Jiang J., Shi y, Xue L. Effects of HSP70 on HBV expression and Notch1 signaling pathway in HepG2 2.15 cells. Hebei Med J. 2021;43(4):514–517. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo H.W., Seo J.P., Jung G. Heat shock protein 70 and heat shock protein 90 synergistically increase hepatitis B viral capsid assembly. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(4):2892–2898. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao J-l, Yang Z-g, Chen X-r, Xu Q-n, Liu Y-f. Correlation between expression of heat shock protein 70 and clinicopathological features of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Hepatol. 2015;31(5):733–736. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X., Yang X., Li L., Liu H., Liu J. A truncated C-terminal fragment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis HSP70 gene enhanced potency of HBV DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24(16):3321–3331. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang J., Liu Z-y, Zheng L-h, Chen X-t, Gu Y-r, Zheng Y-b. Correlation between plasma levels of IL-33, HSP60, HSP70 and Histone4 and severity of HBV-induced liver diseases. J Trop Med. 2019;19(5):549–553+669. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondo Y., Ueno Y., Kobayashi K., Kakazu E., Shiina M., Inoue J., Tamai K., Wakui Y., Tanaka Y., Ninomiya M., Obara N., Fukushima K., Ishii M., Kobayashi T., Niitsuma H., Kon S., Shimosegawa T. Hepatitis B virus replication could enhance regulatory T cell activity by producing soluble heat shock protein 60 from hepatocytes. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(2):202–213. doi: 10.1086/653496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S.G., Lim S.O., Jung G. Binding site analysis of human HBV pol for molecular chaperonin, Hsp60. Virology. 2002;298(1):116–123. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S.G., Jung G. Human hepatitis B virus polymerase interacts with the molecular chaperonin Hsp60. J Virol. 2001;75(15):6962–6968. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6962-6968.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He H., Fan P., Yin T., Chen Q., Shi H., Liu S., Li H., Jing Q., Yan Y., Zhang H., Yang L., Wen Y., Li Y., Cheng P. Local delivery of recombinant adenovirus expressing hepatitis B virus X protein and interleukin-12 results in antitumor effects via inhibition of hepatoma cell growth and intervention of tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30(3):599–605. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torresi J., Tran B.M., Christiansen D., Earnest-Silveira L., Schwab R.H.M., Vincan E. HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis: the role of signalling pathways and innovative ex vivo research models. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5916-6. 707-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang S.M., Sun D.C., Lou S., Bo X.C., Lu Z., Qian X.H., Wang S.Q. HBx protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) can form complex with mitochondrial HSP60 and HSP70. Arch Virol. 2005;150(8):1579–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0521-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S.G., Lee S.M., Jung G. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides targeted against molecular chaperonin Hsp60 block human hepatitis B virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):39851–39857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka Y., Kanai F., Kawakami T., Tateishi K., Ijichi H., Kawabe T., Arakawa Y., Kawakami T., Nishimura T., Shirakata Y., Koike K., Omata M. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) with heat shock protein 60 enhances HBx-mediated apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(2):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoubeidi A., Gleave M. Small heat shock proteins in cancer therapy and prognosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(10):1646–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman M., Multhoff G. Heat shock proteins in cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:192–201. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi Y.-W., Tan Y.-J., Lim S.G., Hong W., Goh P.-Y. Proteomic approach identifies HSP27 as an interacting partner of the hepatitis C virus NS5A protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318(2):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathew S.S., Della Selva M.P., Burch A.D. Modification and reorganization of the cytoprotective cellular chaperone Hsp27 during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9304–9312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01826-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harimoto N., Shimada M., Aishima S., Kitagawa D., Itoh S., Tsujita E., Maehara S., Taketomi A., Tanaka S., Shirabe K., Maehara Y. The role of heat shock protein 27 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: special reference to the difference between hepatitis B and C. Liver Int. 2004;24(4):316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King K.L., Li A.F., Chau G.Y., Chi C.W., Wu C.W., Huang C.L., Lui W.Y. Prognostic significance of heat shock protein-27 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relation to histologic grading and survival. Cancer. 2000;88(11):2464–2470. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11<2464::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng S-t, Ren J-h, Liu B., Chen J. Study on heat shock protein B1 inhibiting HBV replication. J Third Mil Med Univ. 2016;38(23):2492–2498. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong S.W., Yang Y.X., Hu H.D., An X., Ye F., Ren H., Li S.L., Zhang D.Z. HSPB1 is an intracellular antiviral factor against hepatitis B virus. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114(1):162–173. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tadros S.F., D'Souza M., Zhu X., Frisina R.D. Gene expression changes for antioxidants pathways in the mouse cochlea: relations to age-related hearing deficits. PLoS One. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090279. e90279-e90279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poussard S., Pires-Alves A., Diallo R., Dupuy J.W., Dargelos E. A natural antioxidant pine bark extract, Oligopin®, regulates the stress chaperone HSPB1 in human skeletal muscle cells: a proteomics approach. Phytother Res. 2013;27(10):1529–1535. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song T.F., Zhang Z.F., Liu L., Yang T., Jiang J., Li P. Small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of heat shock protein 27 (HSP27) Increases chemosensitivity to paclitaxel by increasing production of reactive oxygen species in human ovarian cancer cells (HO8910) J Int Med Res. 2009;37(5):1375–1388. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimm D., Heeg M., Thimme R. Hepatitis B virus: from immunobiology to immunotherapy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2013;124(2):77–85. doi: 10.1042/CS20120169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mengji L., Hang S. Research progress of therapeutic vaccine for chronic hepatitis B. Prog Pharmaceut Sci. 2022;46(10):761–770. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H., Su X., Zhang P., Liang J., Wei H., Wan M., Wu X., Yu Y., Wang L. Recombinant heat shock protein 65 carrying PADRE and HBV epitopes activates dendritic cells and elicits HBV-specific CTL responses. Vaccine. 2011;29(12):2328–2335. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang S., Qiu L., Liu G., Li Y., Zhang X., Jin W., Gao G.F., Kong X., Meng S. Heat shock protein gp96 enhances humoral and T cell responses, decreases Treg frequency and potentiates the anti-HBV activity in BALB/c and transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2011;29(37):6342–6351. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng M., Chen M., Ling N., Xu H., Qing Y., Ren H. Novel vaccines for the treatment of chronic HBV infection based on mycobacterial heat shock protein 70. Vaccine. 2006;24(7):887–896. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.