Abstract

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) control gene expression at the post-transcriptional level and are widely involved in carcinogenesis, playing a role as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors. MiRNAs act as potent therapeutic weapon in cancer, but their potential therapeutic use is limited by the off-target effect due to their nonspecific distribution in normal tissues. The encapsulation of miRNAs in nanostructured carriers allows targeted effects aimed to destroy cancer cells, without affecting healthy tissues. Due to their small size and the optimal surface/size ratio, nanoparticles (NPs) envelop, protect, and release miRNAs, representing a promising strategy in cancer treatment. In the present review, we discuss the latest advances in the field of miRNA-encapsulating NPs in cancer, focusing on colorectal cancer and its metastatic forms, one of the most common malignancies worldwide.

Keywords: MT: Non-coding RNAs, miRNAs, nanoparticles, theranostics, nanomedicine, cancer, colorectal cancer

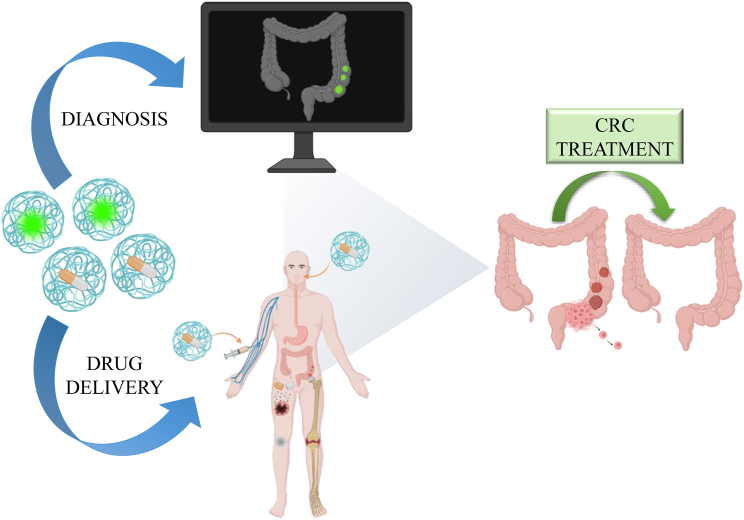

Graphical abstract

D'Onofrio and colleagues in this review update the emerging anti-cancer role and the theranostic applications of microRNAs encapsulated in differently combined nanoparticles, with a critical focus on colorectal cancer and its metastatic forms, one of the most common malignancies worldwide.

Introduction

The search of novel treatments for cancer remains an open door, as well as an urgent requirement for the health of the global population.1 Multiple conventional approaches based on cancer type, location, stage, and available treatments are routinely used in clinical practice, but side effects and relapse are still observed.2 Indeed, the most used cytotoxic drugs are fluoropyrimidines (5-fluorouracil, 5-FU), capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan, used alone or in combination with target-based or immunotherapeutic agents such as anti-VEGF, -EGFR, -PD-1 antibodies, and BRAF and MEK inhibitors. These weapons can induce cancer cell death and growth inhibition, even if with several toxic effects for patients.3 The multiple low dose strategy consisting in the administration at low concentrations of two or more drugs targeting the same signaling pathway has been developed to avoid the establishment of drug-resistant cell mutants.4 In this light, the knowledge of the molecular mechanisms and the genetic signature of cancer has contributed to the optimization of the treatment, determining a significant increase of patient survival.5 A successful treatment, preventing side effects and cytotoxicity to healthy tissues and organs by selectively targeting tumor tissues6 could result from the design of new therapeutics based on nanoparticles (NPs), delivering small non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs),7 which act as oncogenic or tumor suppressor players at the epigenetic level.

Colorectal cancer (CRC), although still representing the third malignancy for diagnosis and the second cancer for prevalence in the world, shows a mortality that is steadily decreasing during the times due to new therapeutic approaches.5 The CRC etiology involves both genetic and environmental risk factors which, in turn, determine its development and cause metastases at diagnosis in 20% of patients.8 CRC metastases can be favored by mutations in genes involved in the intracellular signaling cascade regulating cell proliferation, survival, invasiveness, metastatic spread, and tumor-induced angiogenesis such as RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK and PTEN-PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways.8 Other common genetic defects related to CRC are the familial adenomatous polyposis, due to mutation of adenomatous polyposis of colon (APC), and the Lynch syndrome, related to microsatellite instability.9 On the other hand, the most common sporadic forms of CRC showed higher incidence in people with obesity, sedentary life, and/or addicted to smoking and excessive alcohol consumption.10 Despite improved treatments, patients with metastatic CRC generally have a median survival rate between 24 and 36 months and for several metastatic CRC forms the available treatments are not effective.5 The strategies based on the combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy can synergistically improve the response of CRC patients to treatment, but still have limitations and induce severe side effects.11 To date, the need to develop innovative methods to improve both safety and efficacy in the treatment of CRC is compelling.

The advanced knowledge of cellular and/or molecular components involved in CRC carcinogenesis and progression led to the development of modern personalized medicine based on the use of miRNAs specifically delivered to tumor cells by effective and safe NPs. Here, we provide a comprehensive review on the progress achieved in identifying novel tumor-related miRNAs and their targets, as well as the latest developed nanocarriers to deliver therapeutic compounds with a focus on CRC diagnosis and treatments.

miRNAs: Emerging targets for cancer treatment

miRNAs, discovered in 1993 in Caenorhabditis elegans as negative post-transcriptional regulators, are synthesized from endogenous miR genes in the nucleus as long transcripts of about 1,000 nucleotides and processed in hairpin structures of about 80 nucleotides giving rise to pre-miRs that are transported in the cytoplasm and definitively processed in the mature miR:miR duplex.7,12 The 18 to 25nucleotides-long single-stranded miR is then loaded on the RISC complex where for not perfect complementarity is assembled to the 3′-UTR of the target mRNA.7,12 MiR binding to the target mRNA results in the inhibition of translation and reduction of the polyadenylation of the mRNA that, in turn, induces its half-life decrease.13 The miRNA ability to modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level makes these small RNAs key regulators of several diseases, as chronic degenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer.14 Acting as both oncosuppressor and oncogenic players, miRNAs represent specific targets of novel anti-cancer approaches, based on inhibition or enhancement of their action, by acting on drug transporters, DNA repair, cancer stemness, epithelium-mesenchymal transition, extracellular vesicles formation, and autophagy.15 For example, the overexpression of miR-21 and miR-25-3p enhances cell proliferation and invasion in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) inhibiting phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) expression and activating the protein kinase B (AKT) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, respectively.16 In breast cancer patients, the presence of specific miRNAs, such as miR-10b, miR-34a, and miR-155 in circulating blood, has been shown as an independent prognostic marker for cancer risk stratification.17 miR-145, involved in the modulation of several oncogenes, triggers the transition from in situ to metastatic prostate cancer.18 In high-grade prostate cancer miR-148 and miR-29b are downregulated, suggesting their potential role as tumor suppressors.18,19 MiR-29b therapeutic action against prostate cancer development has been supported by unveiling its ability to promote pro-apoptotic protein expression, such as BCL2L11 (Bim), cytochrome c, and the cleaved form of PARP, in in vitro and in vivo models.19

Accumulating evidence underlines miRNAs as novel biomarkers with potential clinical significance for tumorigenesis staging due to their association with tumor pathogenesis. The assessment of miRNA levels by non-invasive or minimally invasive approaches is of utmost importance and growing studies describe specific circulating miRNAs as cancer biomarkers. Recently, two panels of miRNA pairs (miRPairs) have been developed for glioma. The first panel is composed of five serum miRPairs reaching 100% diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing glioma and non-cancer controls. The second panel includes 32 serum miRPairs, reaching 100% diagnostic performance in specifically discriminating glioma from other cancer types.20 Tissue- and plasma extracellular vesicles-derived miR-99a-5p have been reported as potential biomarkers for predicting early head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.21 Tumor tissue exhibited lower miR-99a-5p levels than para-tumor tissue while plasma extracellular vesicles harbored more miR-99a-5p compared with benign disease group.21 MiR-183-5p may represent a predictive biomarker for CRC prognosis and aggressiveness, given its overexpression in CRC plasma samples compared with healthy controls, with higher levels associated to lymph node metastasis and advanced clinical stage.22 Similarly, circulating serum miR-1229 and miR-1246 have been found overexpressed in CRC patients, with miR-1246 significantly upregulated in advanced tumor-node-metastasis stage III of CRC subjects.23 The evaluation of miRNA expression as staging biomarkers can represent a diagnostic tool also in gastric cancer. MiR-21, strongly upregulated in aggressive gastric cancer, triggers cell proliferation, invasion, and migration by remodeling the extracellular matrix and downmodulating key apoptotic genes like the tumor suppressor RECK.24 MiR-192 and miR-215 can promote cell proliferation and migration, via APC inhibition and the Wnt signaling activation, thus inducing gastric cancer progression.25 MiR-1275 regulates gastric cancer cell lipid signaling by reverting the oncogenic effects mediated by fatty acid amide hydrolase, through the downregulation of arachidonoyl ethanolamide (AEA)/lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signaling and activation of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)/prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) axis, thereby affecting gastric cancer progression.26 MiR-301a is involved in the mechanisms of platinum-resistance of non-small cell lung cancer through the modulation of GLI pathogenesis-related 1 (GLIPR1) and Fos-related antigen-2 (FOSL2/Fra-2) axis. The latter increases the transcription of MIR301A gene, ultimately indicating miR-301a as a biomarker to stratify patients who better respond to cisplatin.27

Exosomal miR-4655-5p secreted by lung cancer cells has been recently shown as a new target for prevention and treatment, given its ability to promote the macrophage proliferation and inflammatory response by forming a negative regulatory loop that alters Midline 1 (MID1) activity and its downstream PP2Ac.28 MiR-202-3p overexpression, lowly expressed in lung cancer tissues, inhibited the proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer cells by targeting the ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2.29

Several studies reported alterations of miRNA profile in CRC, including miR-186-5p, miR-22-3p, miR-22-5p, miR-25-3p, miR-92a-3p, and miR-16-5p, compared with healthy subjects.30,31 Upregulated miRNAs can target the downregulation of different tumor suppressor genes involved in CRC development, while in the healthy tissues miRNA silencing can attenuate the activity of proto-oncogenes.30 Indeed, the CRC carcinogenesis is finely regulated by miRNA content, particularly in the adenoma-carcinoma transition. Increased miR-135a/b expression is associated with decreased APC levels and Wnt signaling pathway activation, pivotal features of the transformation from normal colonic epithelium into adenoma.30 Recently, the miR-15a-5p role has been described to promote proliferation, migration, and chemoresistance of CRC cells, providing its capability to target SIRT4 and modulate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1) and PTEN/AKT signaling.32 Abnormal expression of miR-483 promoted the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of CRC by reducing the expression level of autophagy associated transmembrane protein (EI24),33 while the upregulated levels of miR-498 resulted in reduced proliferation of CRC cells, with concomitant increase of apoptosis due to Bcl-2 knockdown.34 To date, the search for new miRNA-regulated cancer pathways is still paving great attention to get light on new molecular mechanisms involved in carcinogenesis. Moreover, combination therapy based on multiple therapeutic approaches to simultaneously inhibit specific target genes could be a useful strategy to improve therapeutic efficacy, thus overcoming resistance to anti-cancer treatments. MiRNAs become a focus of investigation as specific gene regulators related to drug resistance phenotype. Altered miRNA expression profiles led to chemoresistance by abnormally regulating the expression of genes involved in multidrug resistance mechanisms, as apoptosis, autophagy, and drug metabolism.35 Resistance to cisplatin and olaparib is mediated by miR-493-5p overexpression in BRCA2-mutated ovarian cancer cells targeting multiple genes involved in regulating single-strand annealing DNA repair and genomic stability.36 Inhibition of miR-212 resulted in ABC Subfamily G Member 2 (ABCG2) increase, opposing the imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemic cells, while differentially expressed circulating miRNAs regulate several molecular pathways involved in drug resistance in TNBC patients with overexpressing miR-93, miR-210, miR-19a, and miR-19b associated with poor overall survival outcomes.37,38 Finally, miR-208b overexpression in CRC cell-derived exosomes accelerates tumor progression and reduces oxaliplatin chemotherapy sensitivity, while miR-21 inhibitor reversed tumor resistance with promotion of cytotoxicity in 5-FU-resistant tumor colon cells.39,40

miRNAs: Emerging diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive markers of response in CRC

miRNAs can be potentially used as relatively non-invasive, cheap, fluid-based biomarkers for the detection of CRC displaying good sensitivity and specificity. To use miRNAs as a clinical tool, it is necessary to evaluate and create a CRC-related panel by analyses performed on the same matrix and with reproducible methods. Over the past years, several miRNAs useful for CRC prognosis and diagnosis have been identified (Figure 1), potentially discriminating metastatic from non-metastatic patients (Table 1). In this light, a panel of four upregulated serum-derived miRNAs (miR-19a-3p, miR-203-3p, miR-221-3p, and let-7f-5p) has been correlated with the presence of lymph node metastases.41 In addition, a miRNA profile, including let-7e-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-28-3p, and miR-542-5p, allowed to differentiate CRC patients from healthy subjects and from thickened polyps and adenomas.42 miR-490-3p expression can be considered as a predictive metastatic marker, since its levels were remarkably lower in CRC tissues from lymph node or visceral metastases if compared with primary tumors.43

Figure 1.

miRNAs in CRC theranostics

miRNAs are valuable biomarkers in CRC diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized medicine.

Table 1.

Dysregulation of miRNAs valuable for chemoresistance, prognosis, and/or diagnosis in colorectal cancer

| Clinical value | miRNA | Regulatory status | Clinical source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | miR-19a-3p, miR-203-3p, miR-221-3p, let-7f-5p | Up | Serum | Dokhanchi et al.41 |

| let-7e-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-28-3p, miR-542-5p | Up | Serum/Tissue | Silva et al.42 | |

| miR-490-3p | Down | Tissue | Li et al.43 | |

| miR-21 | Up | Serum | Liu et al.44 | |

| miR-1290 | Up | Serum/Tissue | Xu et al.45 | |

| miR-210, miR-203 | Up | Serum | Nassar et al.46 | |

| miR-1246 | Up | Serum | Salah et al.47 | |

| miR-451 | Down | Serum | Salah et al.47 | |

| miR-4745-5p, miR-6126, miR-1469 | Up | Tissue | Gungormez et al.48 | |

| miR-378 | Down | Tissue | Gungormez et al.48 | |

| miR-195, miR-139 | Down | Tissue | Feng et al.49 | |

| miR-20a, miR-183 | Up | Tissue | Feng et al.49 | |

| miR-99a, miR-100 | Down | Tissue | Wang et al.50 | |

| Diagnosis and Prognosis | let-7c-5p, let-7e, miR-34c-5p, miR-133b | Up | Tissue | Song et al.51 |

| miR-106a, miR-144 | Down | Tissue | Song et al.51 | |

| miR-449 | Down | Tissue | Lan et al.52 | |

| Prognosis | miR-96, miR-99b | Up | Serum | Chen et al.53 |

| miR-216a-5p | Up | Tissue | Liu et al.54 | |

| miR-194-3p, miR-3677-3p | Down | Tissue | Liu et al.54 | |

| miR-132 | Up | Tissue | Samadi et al.55 | |

| miR-193a, let-7g | Up | Serum | Cho et al.56 | |

| miR-21-5p | Up | Serum | Fukada et al.57 | |

| miR-543 | Up | Tissue | Liang et al.58 | |

| Drug Resistance | miR-33a-5p | Up | Serum | Sasaki et al.59 |

| miR-125b-5p | Down | Tissue | Sun et al.61 | |

| miR-487a-3p, | Down | Tissue | Shi et al.63 | |

| miR-526b-3p | Down | Tissue | Zhang et al.62 | |

| miR-148a | Down | Tissue | Shi et al.60 | |

| miR-155 | Up | Tissue | Gao et al.64 | |

| miR-135b-5p | Up | Serum | Qian et al.66 | |

| miR-454-3p | Up | Serum | Wang et al.65 | |

| miR-193a-5p | Down | Tissue | Azar et al.67 |

Circulating miR-21, miR-1290, miR-210, and miR-203 overexpression is associated with CRC diagnosis.44,45,46 A case control study on Egyptian patients correlated the higher miR-1246 expression to lower miR-451 levels in serum of CRC subjects compared with healthy controls.47 Gungormez and colleagues described the relationship between upregulated miR-4745-5p, miR-6126, and miR-1469 levels and decreased content of miR-378 family in CRC tissues.48 The correlation between CRC and reduced miR-195, miR-99a, miR-100, and miR-139 expression has been reported, as well as miR-20a and miR-183 overexpression.49,50 Clinical evidence correlated let-7c-5p, let-7e, miR-34c-5p, and miR-133b levels to CRC progression and poor prognosis, and described miR-106a and miR-144 as tumor suppressors counteracting the bad clinical outcome of CRC.51 Similarly, miR-449 downregulation could act as both a diagnostic and prognostic marker in patients affected by CRC predicting a poorer clinical outcome.52 Among prognostic markers for CRC, miR-96 and miR-99b have been classified as predictive markers,53 as well as miR-216a-5p, miR-194-3p, and miR-3677-3p. Interestingly, the latter are predictive markers of patient survival and response to chemotherapy drugs.54 Moreover, a transcriptome study identified miR-132 as a poor predictor of overall survival in CRC patients.55 Exosomal miR-193a and let-7g high expression has been correlated with poor prognosis, recurrence, and venous and lymphatic invasion in CRC.56 A prospective study investigated the changes of miR-21-5p in CRC patients before surgery and 1 and 6 months after surgery showing significantly higher miR-21-5p levels in relapsing plasma patients.57 Moreover, higher miR-543 expression was recorded in CRC tissues derived from patients with worse overall survival likely due to PTEN downregulation induced by miR-543.58 The contribution of miRNAs as predictive tools of CRC chemoresistance has been reported. In this light, miR-33a-5p overexpression was described as an effective biomarker for CRC patients unresponsive to a combination of fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab.59 The failure of cisplatin-based therapy is very common in CRC and miRNAs could be useful to predict this condition. In this view, cisplatin-resistance and poor prognosis have been correlated with miR-125b-5p, miR-487a-3p, miR-526b-3p, and miR-148a downregulation in both CRC tissues and cells.60,61,62,63 On the other hand, miR-155 overexpression reverts chemoresistance to cisplatin, by inhibiting FOXO3 expression, in CRC patient-derived tissues both in vitro and in vivo.64 The development of resistance to oxaliplatin (oxa), widely used in CRC treatment, is another considerable obstacle to therapeutic efficacy. In this view, miR-135b-5p and miR-454-3p were increased in serum of CRC patients, with further elevated levels in oxa-resistant patients,65,66 while miR-193a-5p was decreased in CRC tissues compared with healthy marginal tissue. This dowregulation was less significant in patients who received 5-FU or oxa, compared with non-treated subjects.67

NPs: General features

Since the 1960s, when the first liposomal nanoparticle encapsulated with doxorubicin (Doxi), was designed, many anti-cancer NPs have been developed for cancer treatment.68 To date, about 50 nano-formulations have been approved as clinical diagnostic and therapeutic agents.69 NPs are formed by atomic or molecular aggregates with a size ranging from 1 to 300 nm able to envelop and deliver targeted drugs improving pharmacokinetics, half-life, and bioavailability. The small size and safe synthesis, along with the use for microscope imaging, induced the exponential development and use of NPs in medicine and diagnostics.70 NPs can be divided into two main groups: organic and inorganic, both used in different medical fields, as gene therapy, imaging, and drug delivery (Figure 2).71 Inorganic NPs are characterized by a large surface area, optical and magnetic properties, and target specificity, enhanced by specific ligands. Inorganic NPs are less toxic and more stable than organic nanocarriers and can protect drugs from degradation allowing a gradual release.72 Solid nanocarriers, particularly iron oxide NPs, formed by an organic core as Fe3O4 with a biocompatible polymer, are often used as inorganic biosensors in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).73 Solid gold NPs display different features including high biocompatibility and permeability, thus allowing to reach the proper site of action and release high concentrations of the drug.74

Figure 2.

Nanoparticle features

Schematic representation of organic and inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) generated by atomic or molecular aggregates and able to envelop and deliver specific agents ameliorating pharmacokinetics, half-life, and bioavailability.

Organic NPs are flexible, photostable, highly water soluble, and easy to synthesize. The peculiar composition allows the binding of several water-soluble and hydrophobic drugs, ensuring high efficiency as a nanocarrier.72 To date, different NPs are used for multiple purposes based on their specific properties. Polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) are the most common organic NPs able to include compounds in a polymeric matrix consisting in poly lactic glycolic acid (PLGA) or chitosan.75 Prevalent lipid-based NPs, as liposomes, contain surface rich in phospholipids and cholesterol enveloping a hydrophilic core, suitable for delivery and retention of substances for a long time.73

In the past decade, organic and inorganic NPs have been developed for CRC diagnosis and treatment.76 The first generation of NP-based therapy included lipid systems such as liposomes, micelles, and dendrimers containing inorganic gold or magnetic NPs used as biomarkers for their peculiar surface properties.77 NPs have peculiar properties such as a large surface and porosity, which allow encapsulating larger drug dosages and contributing to an easier targeting to cancer sites. According to the features of the tumor microenvironment, the drug release may be mediated by internal stimuli as alteration in temperature, pH, ionic strength, redox state, or by enzymatic action or by external stimuli, as electric and electromagnetic fields, radiation, or ultrasounds.78 The tumor environment is characterized by low pH, hypoxia, and some specific overexpressed enzymes, receptors, and antigens. The interaction between specific molecules exposed on carriers (monoclonal antibodies, ligands, peptides, or nucleic acids) and a counterpart present in the target site can be used for the specific delivery of the NPs in the cancer tissue allowing the drug internalization through endocytosed receptors.79

The administration of nanostructured compounds allows the specific accumulation of the nanocarriers in the tumor tissues taking advantage of the tumor vasculature abnormalities represented by hypervascularization and aberrant vascular architecture caused by the presence of pores and the extensive production of vascular permeability factors stimulating extravasation of NPs.80 This effect is paralleled by the lack of the lymphatic drainage of the cancer tissues that allows the accumulation of NPs after vessel crossing. This process is called “enhanced permeability and retention (EPR).”81 Because of the EPR effect, the use of NPs ensures the macromolecule accumulation in tumor tissues.82 Furthermore, nanotechnologies overcome the poor permeability of many drugs caused by susceptibility of the hostile gastrointestinal environment.83 Indeed, oral drugs deal with a difficult biochemical environment, due to pH changes in the gastrointestinal tract, metabolizing enzymes and surfactants as bile salt. Nanoparticulate drugs, with their chemical-physical characteristics, increase intracellular penetration and absorption, improving drug oral bioavailability.84 Indeed, as NPs have small size and large surface area, they are able to encapsulate a variety of pharmacological agents, ensuring an extended systemic half-life.85 Moreover, since the nanomaterials used are biodegradable and display small sizes, they provide a faster biodistribution and improved drug solubility and absorption.86

NPs for theranostic applications

Nanotechnologies provided a new horizon in medicine for cancer treatment, since NPs can be used to target gene overexpression in tumor cells, as contrast agents in imaging systems, as well as nanocarriers of several chemotherapeutic drugs.87 Theranostics represents more specific therapeutic choices, being a valid tool in personalized medicine to increase cancer diagnosis and treatment and offering new strategies to counteract tumor resistance to conventional chemo- and immuno-therapeutics.88 Different NPs can be functionalized with fluorescent moieties and used for diagnostic and imaging applications and, opportunely charged with drugs, for therapeutic uses. The resulting combined nanoconjugates allow to simultaneously target tumor-related molecules, as well as image and treat cancer (Figure 3).88 NPs are used as diagnostic agents in different cancer types. Biotinylated anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) antibody conjugated to streptavidin-labelled iron oxide NPs have been used to evaluate PSMA levels in prostate cancer.89 Manganese dioxide (MnO2)-coated polydopamine (PDA) NPs related to camptothecin (CPTNPs), a cytotoxic quinolone alkaloid, allow the detection of lung cancer cells by MRI.90 A recent study described the potential of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) NPs in cancer diagnosis, being suitable in MRI or as contrast agents.91

Figure 3.

NPs in cancer therapy and diagnosis

Predominant applications of NP-based nanomedicine as therapeutic and diagnostic drug delivery in cancer.

The epirubicin-5TR1 aptamer-superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPION) NP tertiary complex allowed the MRI-based diagnosis in in vitro CRC models.92 Recently, the fluorescent effect of the Ashwagandha chitosan NPs (AshCNPs) subjected to near-infrared light (NIR) was used to distinguish CRC cells due to the light diffusion difference existing between cancer and non-tumor cells.93

NPs for cancer treatment

The NP-based nanotechnology has been used to increase the efficiency of different anti-cancer agents. Different mechanisms related to NP composition and/or combination with miRNA or drugs led to their promising use in cancer theranostic applications. NPs can induce cancer cell death by triggering reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, modulating key proteins of vital cell pathways, inducing photo- and radiotherapy, and displaying site-specific cytotoxicity.94 Selenium NPs (SeNPs) cause apoptosis via an unfolded protein response signaling pathway in human cancer cell lines, while gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) inhibit migration and colony-forming ability, as well as reverse the chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer cells.95,96 Acting as catalase, the Au conjugate with nano metal-organic frameworks Au@ZIF-8 NPs upon their arrival at the tumor environment catalyzed the excessive H2O2 resulting in specific cytotoxicity.97 PEGylated AuNPs conjugated with miR-206 mimic arrested breast cancer cells in the G0-G1 phase by targeting the NOTCH3 gene, as gold nanorods able to specifically release miR-320a, increased apoptosis and inhibited cell proliferation and metastasis enhancing PTEN expression and inhibiting MMP-9 in both in vitro and in vivo lung cancer models.98,99 A study performed in murine breast cancer and melanoma models improved the activity of tumor antigen-based (tumor-associated antigen, TAA) immunotherapy using nanodisc vaccination against cancer stem cells (CSCs) markers, as aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), leading to a significant reduction in ALDH high positive CSCs, along with tumor growth inhibition and extended animal survival.100 A recently developed system based on cancer cell membranes (CCM)-coated PLGA NPs prevents scavenging by the immune system, thus ameliorating the drug specificity for cancer cells.101 The use of stealth solid lipid nanoparticles (sSLN) has been effective in treating in vivo breast cancer, overcoming biological barriers, and ensuring a higher drug concentration in cancer cells, intensifying the anti-cancer activity.102 The activity of alginate (Alg)-coated platinum (Pt@Alg) NPs in sensitizing breast cancer cells to radiation therapy has been reported.103 Wang and colleagues silenced protein kinase N3 (PKN3), strongly expressed in prostate cancer cells, by developing a bioreducible, biodegradable, and ionizable lipid-based NP encapsulating shPKN3.104 This innovative method counteracted cancer progression and was a more effective and less toxic transfectant agent increasing in vivo tumor suppression.104 Recent evidence showed the antitumor action of icaritin loading poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA@Icaritin) NPs in in vivo models of gastric cancer. Particularly, PLGA@Icaritin NPs stimulated ROS production, altered mitochondrial membrane potential lowering, and enhanced immune system response against tumor cells, thus impairing cancer progression.105 In vitro and in vivo models of gastric cancer revealed the ability of resveratrol-modified mesoporous silica (MSN-Res) NPs to counteract tumorigenesis, inhibiting proliferation, invasion, and cell migration, along with apoptosis promotion, with more prominent effects than treatment with the polyphenolic compound alone.106 Treatment with manganese dioxide (MnO2)-coated PDA NPs-camptothecin nanosystem inhibited cell proliferation, paralleled by apoptosis and ferroptosis induction in lung cancer cells.90

Immunotherapy advances represent crucial aspects in cancer therapy since the immune system is fundamental in the establishment and development of tumor cells. NPs deliver chemotherapeutic agents and can be used in immunotherapy. NP-based approaches in immunotherapy consist of nanovaccines, artificial antigen-presenting cells (aAPCs), and immunosuppressed tumor microenvironment (TME) targeting.107 Liposomes, AuNP, and PLGANPs deliver TAAs into dendritic cell cytoplasm, while the inorganic mesoporous silica NPs exhibit an adjuvant role leading to immune response stimulation.108 The combined use of the chemotherapeutic agent Nutlin-3a and the cytokine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in spermine-modified acetylated dextran (AcDEX) NPs improved cytotoxic CD8+ T cell proliferation, thus activating the immune response.109 More recently, the miR-34a delivery using a transgene carrier in the form of iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (IONPs) via magnetofection has been effective to downregulate the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) gene in both non-small-cell lung carcinoma and TNBC cells.110

NPs in CRC therapy

Nanotechnology has gained increasing interest in recent years due to its significant contribution to CRC treatment.6 Oral treatment by NP-targeting drugs is a promising delivery to accumulate antineoplastic compounds in tumor colon sites and increase therapeutic efficacy. PLGA NPs have been used to encapsulate and preserve 5-FU, enhancing its levels in CRC cells.111 In addition, 5-FU carried by epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) aptamer-activated NPs (Ap-NPs) induced higher cytotoxicity in CT-26 and HCT-116 cells than its free form.112 Gelatin-covered diatomite NPs have been used to transport the galunisertib to ligand 1-cell adhesion molecule (L1-CAM)-expressing metastatic SW620 cells, improving its specificity, reducing its degradation, and protecting it from the action of digestive enzymes.113 Heshmatian et al. showed that folic acid-conjugated gold (GNP-F) NPs in combination with doxorubicin (DOX) and X-ray irradiation increased radiotherapy sensitivity resulting in increased cytotoxic effects in HT-29 cells.114 Poly (ethylene glycol) and poly (ε-caprolactone) (PEG-b-PCL) NPs delivering phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and AKT inhibitors have been tested on metastatic CRC with consequent increase of the drug concentration in metastatic tissue, lowering systemic toxicity and enhancing inhibition of CRC metastasis growth.115 Organic NPs have been used as drug carriers against CRC due to their easy synthesis and distinctive performance. In vivo reports demonstrated that PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs impair CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by affecting NF-κΒ signaling pathway and promoting ferroptosis.116 Recently, N-carbamoyl alanine (NCA), a PRDX2 inhibitor, has been evaluated to target a synthetic lethal (SL) PRDX2-CHK2 fusion protein to selectively inhibit the CHK2-null HCT116 cells.117 To overcome the limited use due to high susceptibility to low pH of the gastric environment, the more stable combined NCA-NP formulation has been encapsulated in a chitosan-based nanovector (NCA-Chit NPs), thus enhancing the effectiveness by about 8-fold than NCA free-form.117 The ability of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and chemically modified small interfering RNAs (CMsiRNAs)-based strategy in reducing tumor growth through the inhibition of PCIF1 gene, highly expressed in CRC and related to a negative prognosis, has been validated using an in vivo model.118 Zhang and colleagues increased resveratrol specificity of action and prevented the macrophage-mediated phagocytosis through incorporation into poly(ε-caprolactone)-poly(ethylene glycol) (PCL-PEG) NPs with erythrocyte membranes (RSV-NPs@RBCm), resulting in RSV-related cell death via ferroptosis induction.119 Supermagnetic CS-NPs allowed the release and effective internalization of irinotecan in both in vitro and in vivo models of CRC.120 Mesoporous ruthenium NPs conjugated with specific antibodies were used to target the carcinoembryonic antigen, overexpressed in CRC cells, to attract natural killer cells and to give a sensitive near-infrared-sensitive cytotoxicity.121 In another study, CRC cells overexpressing polyamine transport receptors were obtained by gene therapy and spermine-based NPs were engineered with specific spermine receptor ligands, loaded with an OXA prodrug, and cholesterol and b-cyclodextrin.122 CD-spermine NPs allowed specific OXA release to CRC cells, although with some cytotoxicity.122 Studies on cerium oxide (CeO2)-NPs reported a notable cytotoxic activity on CRC HT-29 cells, with greater cytotoxic effects and ROS accumulation with nickel or zinc oxide NPs.123 The combination of drugs with NPs and curcumin showed remarkable results in CRC treatment, confirming the curcumin ability to affect cell survival and metastasis.124 PEGylated NPs with curcumin and quercetin showed a prolonged release of the natural agents, paralleled by cytotoxicity in both in vitro and in vivo models of CRC.125

miRNA-NPs in CRC theranostics

A precise distribution of miRNAs in therapeutic approaches can be achieved by NP carriers.14 The miRNA limitations due to poor availability and stability in the bloodstream and off-target or on-target side effects, can be successfully overcome by novel nanocarriers based on polyethylenimine-based (PEI) NP, liposomes, polymer micelles, dendrimers, and magnetic and polymeric NPs.126 RNA encapsulating mechanism can be achieved through different processes, including electrostatic adsorption on the surface of preformed NPs, incorporation into the core or the “layer-by-layer” method, requiring sequential electrostatic interaction to encapsulate RNA into multilayer NPs. Each approach has a proper impact on the therapeutic efficiency and protection.127 NPs, including polymer- or lipid-based nanocarriers (vesicles, exosomes, and liposomes), inorganic NPs, and other naturally synthetized NPs have all been used to test miR-based epigenetic treatment of cancer cells. The latter is based on the silencing of oncogenes or the induction of tumor suppressor genes that may be reactivated in tumor cells via miRNA-based treatment (Figure 4).128 Due to their chemical, optical, and physical properties, including targeted drug delivery, increased interaction with target cells, improved cell penetration, and controlled drug release, the nanoscale diamond particles, known as nanodiamonds (NDs), have attracted high attention since the late 1990s. The effectiveness and safety of NDs were recently proven in mouse models, where ND-doxorubicin (ND-DOX) complexes were used to treat different cancer types. Results showed ND-mediated reduction in tumor size, paralleled by absence of side effects up to high concentrations.129 In addition, NDs have attracted great attention for their biocompatibility and ability to protect targeted compounds, supporting their release and stability.130 Lukowski et al. demonstrated for the first time the use of NDs as antisense RNA-carriers specifically directed against the oncomiR-21.131 The ND-related fluorescence allowed each step of the antisense RNA internalization to be followed, while the miR-21 inhibition led to Pdcd4 and Timp3 expression, thus reducing CT-26 cells invasiveness and migration.131 The combined effects of chemotherapy drugs with siRNA and miRNA can be efficient as anti-cancer strategy. In this light, a liposome NP coated by a cationic chitosan (CS) able to co-transport si-KRAS, miR-532-3p, and 5-FU, reduced cell invasion and migration enhancing the drug-derived cytotoxicity in both in vitro and in vivo models of CRC.132 Combination of 5-FU and miR-34a mimics (miR-34a(m)) was synergistic when encapsulated in quantum dot (QD)-based multifunctional nanocarriers, counteracting tumor growth, cell proliferation, and migration in CRC in vitro and in vivo models.133 Xu and colleagues described that miR-375-3p replacement sensitizes CRC cells to 5-FU. Indeed, the combination of lipid-coated calcium carbonate NPs targeting 5-FU and miR-375-3p mimic induced a synergistic action on tumor progression of CRC in in vivo models.134 The use of microspheres as carriers of α-lactalbumin peptosomes (PSs), miR-31 inhibitor (miR-31i), and curcumin combination has been recently demonstrated. These microspheres, mucoadhesive and resistant to the hostile gastrointestinal microenvironment, had an increased anti-proliferative activity in CRC cells.135 The methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone)-Didodecyldimethylammonium bromide- (mPEG-PCL) DDAB-mPEG-PCL loaded/siRNA and quercetin NPs counteracted the Regorafenib resistance induced by α5β1 integrin in CRC cells.136 Recent evidence suggests that thioketal (TK) NPs formed by poly-(1,4-phenyleneacetone dimethylene TK) delivering siRNA against TNF-α, reduced cytokine-derived colon inflammation.128 The encapsulation of metformin in lecithin and chitosan NPs sensitized CRC cells to metformin. The latter effect was due to the downregulation of long non-coding RNA (lncRNAs) LINC00641 and miR-21.137 Functionalized conversion of SiO2-coated NPs (UCNP) has been used in combination with polyetherimide (PEI) and miR-145 to reduce CCND1, CDK6, and CCNE2 protein levels, thus preventing CRC development in a mouse model.138

Figure 4.

NPs as miRNA nanocarriers

NPs mediate miRNA function, improving stability and specificity. The figure summarizes the protection exerted by NPs on miRNAs from acid degradation, by supporting their stability and specific release in CRC cells, where miRNAs can act as cytotoxic agents promoting oncogene silencing or tumor suppressor induction.

NPs can be used as biosensors. In this view, Sun and colleagues developed a system to evaluate miR-92a-3p exosomal levels, by using fluorescent AuNPs with a modified hairpin DNA that, once linked to the specific miRNA, generates fluorescent AuNPs. This tool represents a potential innovative and specific system for CRC diagnosis.139 Prussian blue NP (PBNP)-based fluorescent nanoprobes represent another type of biosensor for the diagnosis of CRC. PBNPs exploit the quenching ability to fluorophores to evaluate miR-92a and miR-21 levels, crucial CRC biomarkers. The high specificity makes this nanoprobe a potential effective method for early CRC diagnosis.140

Conclusions

Undoubtedly, miRNAs play a pivotal role in cancer, although their translation to clinical application is still challenging, due to limited cellular uptake, instability, degradation, and off-target effect in biological systems. In this scenario, nanotechnology allows the development of new delivery systems and innovative treatment strategies based on NPs. In fact, nanocarriers are promising tools for cancer therapy able to selectively deliver different agents, improving circulation half-life and bioavailability, along with drug accumulation in the tumor tissues.6 These effects are due to the EPR effect determined by the altered angiogenesis and lymphatic drainage of the cancer tissues. The decoration of NPs with specific ligands added on their surface makes possible actively targeting specific receptors overexpressed on cancer cells. This process adds an additional advantage to NPs: to recognize cancer cells by binding tumor-associated antigens. In this way, NPs can be used as both diagnostic and prognostic tools defining tumor stage and development of metastases.141 To date, different NPs delivering miRNAs induced promising results in both CRC diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, some of them have suggested the possibility of integrating in a unique carrier the simultaneous tumor imaging and treatment (theranostic). Different miRNA nanoconjugates have been explored, both in vitro and in vivo, in CRC, giving promising results for its treatment. These studies confirmed that nanotechnology is a pivotal approach to improve miRNA modulation in cancer cells and to increase their cancer-specific effects.142

Despite attractive therapeutic agents, less than 20 miRNA targeting molecules are under clinical trials, and none reached phase III. The complexity in the identification of miRNA targets, the lack of proper understanding of the mechanism of action, the weak efficacy of miRNA inhibitors, the need of cell type-specific delivery, and the appearance of unfavorable outcomes interfere with the development of miRNA-based therapeutics.143 Likewise, the main obstacles to overcome for the clinical translation of NPs in cancer therapeutics are represented by the failure to effectively encapsulate drug inside the NPs, formulation instability, low cellular uptake and poor availability, and defective biodegradation/elimination.94 Moreover, the precise toxicological aspects of extended exposure to engineered NPs due to their deep penetrating ability still need further investigation. To date, 16 nano-based cancer drugs received Food and Drug Administration approval and 70 nano-formulations are under clinical investigation.144 Furthermore, dendritic targeted liposomal vaccine entered the phase 1 trial for malignant melanoma and a combined polymeric NP has been administered as the vaccine IMF-001 to patients with solid tumors expressing NY-ESO-1 antigen.145,146 Moreover, the therapeutic capacity of paclitaxel, gemcitabine, atezolizumab, and cyclophosphamide as conjugated in albumin-NP complex has been validated against metastatic and early-stage breast cancer.147

The specific delivery of miRNAs could be useful to counteract several limitations of the current anti-cancer treatments including chemoresistance, side effects, and immunological escape. In addition, miRNAs can synergistically work with other miRNAs or cytotoxic drugs or siRNAs. Moreover, in clinical practice the administration of multiple anti-cancer agents is often needed to control cancer diseases. In this view, the development of nanocarriers able to co-deliver miRNAs or miRNA inhibitors, drugs, and other compounds, combining up to three different therapies in a single carrier, is an attractive strategy to fight CRC and other types of cancers (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

miRNA-NPs as future theranostic approach against cancer

Fluorescent miRNA-NPs, thanks to the quenching ability to fluorophores, represent a potential effective method for early CRC diagnosis. Moreover, the possibility of integrating in one vehicle different agents, makes these nanoprobes a promising tool for cancer therapy.

Future perspectives

An increased knowledge about the biology of the disease, technology, methods, and treatments is needed to achieve the goals of precision medicine in cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and prognosis. Regarding the study of the CRC biology, the use of miRNAs as biomarkers could certainly improve the characterization of the risk, cancer detection, early diagnosis, and prognosis. Moreover, miRNA detection in body fluids can allow the determination of the biological changes of the tumor without requiring serial tissue biopsies. However, are circulating miRNAs specifically released by CRC tissues? Indeed, several circulating miRNAs do not originate from tumor but are influenced by the general homeostatic body response (immunological cells, normal cells from other organs and tissues, normal cells from the tumor microenvironment etc.). Studies based on a larger cohort could provide reliable data and validate miRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers for clinical application. Moreover, to improve the efficiency and accuracy of CRC diagnostic and prognostic biomarker detection, studies on advanced technology-based innovative biosensors must be performed. This could allow the development of sensitive, stable, accurate, and minimally invasive modalities for biomarker measurement. In the case of miRNAs, they can be used for both diagnosis and therapy and the development of nanocarriers with autofluorescent properties or with fluorescence activated by the assembling of the delivered miRNA with a quenched probe could promptly be used to develop theranostics. From a therapeutic point of view, the involvement of miRNAs in several aspects of tumorigenesis and metastasis makes possible to use them as powerful counteractors of the development of tumor drug resistance and spreading potential. The knowledge of the molecular context in which miRNAs work will be important to define the replacement or knockdown of the different miRNAs. This scenario will be possible through the genetic characterization of the tumors that will be allowed by the continuous progress of the next generation of sequencing technologies (even more rapid and cheap).

NPs will be able to deliver both chemotherapy agents and miRNAs, thus allowing synergistic anti-cancer effects without increasing the toxicity of the treatments. Several nanocarriers and miRNA-NP-based clinical trials, already approved, will provide further information about their efficacy in the future, thus allowing the design of trials based on combinations between miRNAs and other drugs. In conclusion, miRNA delivery in cancer with theranostics will represent the ultimate approach for the treatment of both in situ and metastatic cancers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PON I&C 2014-2020-CAPSULE-F/200016/01-03/X45; IZS ME 09/22 RC- STUPORANIMA”; PON I&C 2014–2020-TABAREZO-F/200085/01-03/X45.

Author contributions

E.M., N.D., M.C., and M.L.B. were responsible for writing the original draft. C.A. created the figures. N.D., M.C., S.Z., M.A., and M.L.B. supervised. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Peix F., Casanovas O. Promalignant effects of antiangiogenics in the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;86:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos-de-Frutos K., Djouder N. When dormancy fuels tumour relapse. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:747. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02257-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amjad M.T., Chidharla A., Kasi A. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL: 2022. Cancer chemotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Nicolantonio F., Vitiello P.P., Marsoni S., Siena S., Tabernero J., Trusolino L., Bernards R., Bardelli A. Precision oncology in metastatic colorectal cancer - from biology to medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021;18:506–525. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gogoi P., Kaur G., Singh N.K. Nanotechnology for colorectal cancer detection and treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022;28:6497–6511. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i46.6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon A., Abd-Aziz N., Khalid K., Poh C.L., Naidu R. miRNA: a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:11502. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciardiello F., Ciardiello D., Martini G., Napolitano S., Tabernero J., Cervantes A. Clinical management of metastatic colorectal cancer in the era of precision medicine. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72:372–401. doi: 10.3322/caac.21728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder C., Hampel H. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019;35:58–78. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roos E., Seppä K., Pietiläinen O., Ryynänen H., Heikkinen S., Eriksson J.G., Härkänen T., Jousilahti P., Knekt P., Koskinen S., et al. Pairwise association of key lifestyle factors and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective pooled multicohort study. Cancer Rep. 2022;5:e1612. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu W.D., Sun G., Li J., Xu J., Wang X. Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of cancer immunotherapy in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;452:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krasheninnikov A.V., Foster A.S., Nieminen R.M. Comment on "paired gap states in a semiconducting carbon nanotube: deep and shallow levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007;99:179703. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.179703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimaldi A., Zarone M.R., Irace C., Zappavigna S., Lombardi A., Kawasaki H., Caraglia M., Misso G. Non-coding RNAs as a new dawn in tumor diagnosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;78:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S.W.L., Paoletti C., Campisi M., Osaki T., Adriani G., Kamm R.D., Mattu C., Chiono V. MicroRNA delivery through nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2019;313:80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo H.A., Moeng S., Sim S., Kuh H.J., Choi S.Y., Park J.K. MicroRNA-based combinatorial cancer therapy: effects of microRNAs on the efficacy of anti-cancer therapies. Cells. 2019;9:29. doi: 10.3390/cells9010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J., Wu K.J., Jia Q.J., Ding X.F. Roles of miRNA and lncRNA in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2020;21:673–689. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1900709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gahlawat A.W., Fahed L., Witte T., Schott S. Total circulating microRNA level as an independent prognostic marker for risk stratification in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2022;127:156–162. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01756-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coradduzza D., Cruciani S., Arru C., Garroni G., Pashchenko A., Jedea M., Zappavigna S., Caraglia M., Amler E., Carru C., et al. Role of miRNA-145, 148, and 185 and stem cells in prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:1626. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sur S., Steele R., Shi X., Ray R.B. miRNA-29b inhibits prostate tumor growth and induces apoptosis by increasing Bim expression. Cells. 2019;8:1455. doi: 10.3390/cells8111455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H., Ma L., Luo F., Liu W., Li N., Hu T., Zhong H., Guo Y., Hong G. Construct of qualitative diagnostic biomarkers specific for glioma by pairing serum microRNAs. BMC Genom. 2023;24:96. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09203-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Q., Shen Y.J., Hsueh C.Y., Zhang Y.F., Yuan X.H., Zhou Y.J., Li J.Y., Lin L., Wu C.P., Hu C.Y. Plasma extracellular vesicles-derived miR-99a-5p: a potential biomarker to predict early head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2022;28:1610699. doi: 10.3389/pore.2022.1610699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanjabi F., Nekouian R., Akbari A., Mirzaei R., Fattahi A. Plasma miR-183-5p in colorectal cancer patients as potential predictive lymph node metastasis marker. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022;18:921–926. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_174_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rafiee R., Razmara E., Motavaf M., Mossahebi-Mohammadi M., Khajehsharifi S., Rouhollah F., Babashah S. Circulating serum miR-1246 and miR-1229 as diagnostic biomarkers in colorectal carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022;18:S383–S390. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_752_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhim J., Baek W., Seo Y., Kim J.H. From molecular mechanisms to therapeutics: understanding MicroRNA-21 in cancer. Cells. 2022;11:2791. doi: 10.3390/cells11182791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng S., Zhang X., Qin Y., Chen W., Fan H., Feng X., Wang J., Yan R., Zhao Y., Cheng Y., et al. miRNA-192 and -215 activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in gastric cancer via APC. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020;235:6218–6229. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Q., Kong S., Yu J., Xu Y., Tao M., Ma S., Tang C., Shen X., Tang Z., Ju S. MicroRNA miR-1275 coordinately regulates AEA/LPA signals via targeting FAAH in lipid metabolism reprogramming of gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:62. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-05584-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rampioni Vinciguerra G.L., Capece M., Distefano R., Nigita G., Vecchione A., Lovat F., Croce C.M. Role of the miR-301a/Fra-2/GLIPR1 axis in lung cancer cisplatin resistance. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023;8:37. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X., Wang L., Yu H., Shen Q., Hou Y., Xia Y.X., Li L., Chang L., Li W.H. Irradiated lung cancer cell-derived exosomes modulate macrophage polarization by inhibiting MID1 via miR-4655-5p. Mol. Immunol. 2023;155:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2023.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao X., Xue F., Chen H., Shen L., Yuan X., Yu Y., Zong Y., Zhong L., Huang F. MiR-202-3p inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma cells by targeting RRM2. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022;10:1374. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehrgou A., Ebadollahi S., Seidi K., Ayoubi-Joshaghani M.H., Ahmadieh Yazdi A., Zare P., Jaymand M., Jahanban-Esfahlan R. Roles of miRNAs in colorectal cancer: therapeutic implications and clinical opportunities. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2021;11:233–247. doi: 10.34172/apb.2021.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomeva E., Krammer U.D.B., Switzeny O.J., Haslberger A.G., Hippe B. Sex-specific miRNA differences in liquid biopsies from subjects with solid tumors and healthy controls. Epigenomes. 2023;7:2. doi: 10.3390/epigenomes7010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng J., Wang H., Liang Y., Zhao L., Li Y., Yan Y., Zhao H., Zhang X., Zou F. miR-15a-5p enhances the malignant phenotypes of colorectal cancer cells through the STAT3/TWIST1 and PTEN/AKT signaling pathways by targeting SIRT4. Cell. Signal. 2023;101:110517. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2022.110517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou W., Yang W., Yang J., Zhu H., Duan L., Wang X., Li Y., Niu L., Xiao S., Zhang R., et al. miR-483 promotes the development of colorectal cancer by inhibiting the expression level of EI24. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021;24:567. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T., Ma L., Li W., Ding L., Gao H. MicroRNA-498 reduces the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer cells via targeting Bcl-2. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10:168–175. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Si W., Shen J., Zheng H., Fan W. The role and mechanisms of action of microRNAs in cancer drug resistance. Clin. Epigenetics. 2019;11:25. doi: 10.1186/s13148-018-0587-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meghani K., Fuchs W., Detappe A., Drané P., Gogola E., Rottenberg S., Jonkers J., Matulonis U., Swisher E.M., Konstantinopoulos P.A., et al. Multifaceted impact of microrna 493-5p on genome-stabilizing pathways induces platinum and parp inhibitor resistance in brca2-mutated carcinomas. Cell Rep. 2018;23:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaehler M., Ruemenapp J., Gonnermann D., Nagel I., Bruhn O., Haenisch S., Ammerpohl O., Wesch D., Cascorbi I., Bruckmueller H. MicroRNA-212/ABCG2-axis contributes to development of imatinib-resistance in leukemic cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:92018–92031. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qattan A., Al-Tweigeri T., Alkhayal W., Suleman K., Tulbah A., Amer S. Clinical identification of Dysregulated circulating microRNAs and their implication in drug response in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) by target gene network and meta-analysis. Genes. 2021;12:549. doi: 10.3390/genes12040549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ning T., Li J., He Y., Zhang H., Wang X., Deng T., Liu R., Li H., Bai M., Fan Q., et al. Exosomal miR-208b related with oxaliplatin resistance promotes treg expansion in colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2723–2736. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang G., Zhu Y., Ali D.J., Tian T., Xu H., Si K., Sun B., Chen B., Xiao Z. Engineered exosomes for targeted co-delivery of miR-21 inhibitor and chemotherapeutics to reverse drug resistance in colon cancer. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2020;18:10. doi: 10.1186/s12951-019-0563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dokhanchi M., Pakravan K., Zareian S., Hussen B.M., Farid M., Razmara E., Mossahebi-Mohammadi M., Cho W.C., Babashah S. Colorectal cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles transfer miR-221-3p to promote endothelial cell angiogenesis via targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. Life Sci. 2021;285:119937. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva C.M.S., Barros-Filho M.C., Wong D.V.T., Mello J.B.H., Nobre L.M.S., Wanderley C.W.S., Lucetti L.T., Muniz H.A., Paiva I.K.D., Kuasne H., et al. Circulating let-7e-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-28-3p, and miR-542-5p as a promising microRNA signature for the detection of colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2021;13:1493. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J., Mo R., Zheng L. MicroRNA-490-3p inhibits migration and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer cells via targeting TNKS2. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021;19:117. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu T., Liu D., Guan S., Dong M. Diagnostic role of circulating MiR-21 in colorectal cancer: a update meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2021;53:87–102. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2020.1828617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu L., Cai Y., Chen X., Zhu Y., Cai J. Circulating MiR-1290 as a potential diagnostic and disease monitoring biomarker of human gastrointestinal tumors. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:989. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08729-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nassar F.J., Msheik Z.S., Itani M.M., Helou R.E., Hadla R., Kreidieh F., Bejjany R., Mukherji D., Shamseddine A., Nasr R.R., et al. Circulating miRNA as biomarkers for colorectal cancer diagnosis and liver metastasis. Diagnostics. 2021;11:341. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salah M., Shaheen I., El-Shanawany P., Saad N.E., Saad R., El Guibaly M., Momen N. Detection of miR-1246, miR-23a and miR-451 in sera of colorectal carcinoma patients: a case-control study in Cairo University hospital. Afr. Health Sci. 2020;20:1283–1291. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v20i3.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gungormez C., Gumushan Aktas H., Dilsiz N., Borazan E. Novel miRNAs as potential biomarkers in stage II colon cancer: microarray analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019;46:4175–4183. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04868-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng J., Wei Q., Yang M., Wang X., Liu B., Li J. Development and validation of a novel miRNA classifier as a prognostic signature for stage II/III colorectal cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021;9:747. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X., Gao G., Chen Z., Chen Z., Han M., Xie X., Jin Q., Du H., Cao Z., Zhang H. Identification of the miRNA signature and key genes in colorectal cancer lymph node metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:358. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02058-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song H., Ruan C., Xu Y., Xu T., Fan R., Jiang T., Cao M., Song J. Survival stratification for colorectal cancer via multi-omics integration using an autoencoder-based model. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022;247:898–909. doi: 10.1177/15353702211065010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lan S.H., Lin S.C., Wang W.C., Yang Y.C., Lee J.C., Lin P.W., Chu M.L., Lan K.Y., Zuchini R., Liu H.S., et al. Autophagy upregulates miR-449a expression to suppress progression of colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:738144. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.738144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y., Liu H., Ning S., Wei C., Li J., Wei W., Zhang L. The high ratio of the plasma mir-96/mir-99b correlated with poor prognosis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021;8:799060. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.799060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Z., Lu T., Wang Y., Jiao D., Li Z., Wang L., Liu L., Guo C., Zhao Y., Han X. Establishment and experimental validation of an immune miRNA signature for assessing prognosis and immune landscape of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021;25:6874–6886. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samadi P., Soleimani M., Nouri F., Rahbarizadeh F., Najafi R., Jalali A. An integrative transcriptome analysis reveals potential predictive, prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:835. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho W.C., Kim M., Park J.W., Jeong S.Y., Ku J.L. Exosomal miR-193a and let-7g accelerate cancer progression on primary colorectal cancer and paired peritoneal metastatic cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2021;14:101000. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.101000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukada M., Matsuhashi N., Takahashi T., Sugito N., Heishima K., Yoshida K., Akao Y. Postoperative changes in plasma miR21-5p as a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer recurrence: a prospective study. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:4270–4280. doi: 10.1111/cas.15065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liang Y., Zhu D., Zhu L., Hou Y., Hou L., Huang X., Li L., Wang Y., Li L., Zou H., et al. Dichloroacetate overcomes oxaliplatin chemoresistance in colorectal cancer through the miR-543/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathway. J. Cancer. 2019;10:6037–6047. doi: 10.7150/jca.34650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sasaki M., Ishikawa T., Ishiguro M., Okazaki S., Yamauchi S., Kikuchi A., Matsuyama T., Kawada K., Tokunaga M., Uetake H., et al. The effectiveness of plasma miR-33a-5p as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of colorectal cancer chemotherapy. Oncol. Lett. 2021;21:489. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi H., Li K., Feng J., Liu G., Feng Y., Zhang X. LncRNA-DANCR interferes with miR-125b-5p/HK2 axis to desensitize colon cancer cells to cisplatin vis activating anaerobic glycolysis. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:1034. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun Y., Cao Z., Shan J., Gao Y., Liu X., Ma D., Li Z. Hsa_circ_0020095 promotes oncogenesis and cisplatin resistance in colon cancer by sponging miR-487a-3p and modulating SOX9. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:604869. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.604869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang W., Wang Z., Cai G., Huang P. Downregulation of Circ_0071589 suppresses cisplatin resistance in colorectal cancer by regulating the MiR-526b-3p/KLF12 axis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021;13:2717–2731. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S294880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Shi L., Xi J., Xu X., Peng B., Zhang B. MiR-148a suppressed cell invasion and migration via targeting WNT10b and modulating β-catenin signaling in cisplatin-resistant colorectal cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;109:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao Y., Liu Z., Ding Z., Hou S., Li J., Jiang K. MicroRNA-155 increases colon cancer chemoresistance to cisplatin by targeting forkhead box O3. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:4781–4788. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang H., Wang X., Zhang H., Deng T., Liu R., Liu Y., Li H., Bai M., Ning T., Wang J., et al. The HSF1/miR-135b-5p axis induces protective autophagy to promote oxaliplatin resistance through the MUL1/ULK1 pathway in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40:4695–4708. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01898-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qian X.L., Zhou F., Xu S., Jiang J., Chen Z.P., Wang S.K., Zuo Y., Ni C. MiR-454-3p promotes oxaliplatin resistance by targeting PTEN in colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:638537. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.638537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azar M.R.M.H., Aghazadeh H., Mohammed H.N., Sara M.R.S., Hosseini A., Shomali N., Tamjidifar R., Tarzi S., Mansouri M., Sarand S.P., et al. miR-193a-5p as a promising therapeutic candidate in colorectal cancer by reducing 5-FU and Oxaliplatin chemoresistance by targeting CXCR4. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021;92:107355. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barenholz Y. Doxil®--the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J. Control. Release. 2012;160:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Younis N.K., Roumieh R., Bassil E.P., Ghoubaira J.A., Kobeissy F., Eid A.H. Nanoparticles: attractive tools to treat colorectal cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;86:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Missaoui W.N., Arnold R.D., Cummings B.S. Toxicological status of nanoparticles: what we know and what we don’t know. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018;295:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chakraborty A., Mohapatra S.S., Barik S., Roy I., Gupta B., Biswas A. Impact of nanoparticles on amyloid beta-induced Alzheimer's disease, tuberculosis, leprosy and cancer: a systematic review. Biosci. Rep. 2023;43 doi: 10.1042/BSR20220324. BSR20220324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khizar S., Alrushaid N., Alam Khan F., Zine N., Jaffrezic-Renault N., Errachid A., Elaissari A. Nanocarriers based novel and effective drug delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 2023;632:122570. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Najahi-Missaoui W., Arnold R.D., Cummings B.S. Safe nanoparticles: are we there yet? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;22:385. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y., Crawford B.M., Vo-Dinh T. Gold nanoparticles-mediated photothermal therapy and immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:1175–1188. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vauthier C., Bouchemal K. Methods for the preparation and manufacture of polymeric nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2009;26:1025–1058. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh M., Habib S. Carbon-based Nanomaterials for delivery of small RNA molecules: a focus on potential cancer treatment applications. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2022;10:164–181. doi: 10.2174/2211738510666220606102906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun D., Lu Z.R. Structure and function of cationic and ionizable lipids for nucleic acid delivery. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2023;40:27–46. doi: 10.1007/s11095-022-03460-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gholami Y.H., Engel A. Theranostic nanoplatforms for treatment and diagnosis of rectal and colon cancer: a brief review. Mini-invasive Surg. 2018;2018:44. doi: 10.20517/2574-1225.2018.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yetisgin A.A., Cetinel S., Zuvin M., Kosar A., Kutlu O. Therapeutic nanoparticles and their targeted delivery applications. Molecules. 2020;25:2193. doi: 10.3390/molecules25092193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ejigah V., Owoseni O., Bataille-Backer P., Ogundipe O.D., Fisusi F.A., Adesina S.K. Approaches to improve macromolecule and nanoparticle accumulation in the tumor microenvironment by the enhanced permeability and retention effect. Polymers. 2022;14:2601. doi: 10.3390/polym14132601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kalyane D., Raval N., Maheshwari R., Tambe V., Kalia K., Tekade R.K. Employment of enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR): nanoparticle-based precision tools for targeting of therapeutic and diagnostic agent in cancer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019;98:1252–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu J. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect: the significance of the concept and methods to enhance its application. J. Pers. Med. 2021;11:771. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parodi A., Buzaeva P., Nigovora D., Baldin A., Kostyushev D., Chulanov V., Savvateeva L.V., Zamyatnin A.A., Jr. Nanomedicine for increasing the oral bioavailability of cancer treatments. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19:354. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-01100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Y., Pi C., Feng X., Hou Y., Zhao L., Wei Y. The influence of nanoparticle properties on oral bioavailability of drugs. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:6295–6310. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S257269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Swierczewska M., Crist R.M., McNeil S.E. Evaluating nanomedicines: obstacles and advancements. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1682:3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7352-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mazayen Z.M., Ghoneim A.M., Elbatanony R.S., Basalious E.B., Bendas E.R. Pharmaceutical nanotechnology: from the bench to the market. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022;8:12. doi: 10.1186/s43094-022-00400-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aghebati-Maleki A., Dolati S., Ahmadi M., Baghbanzhadeh A., Asadi M., Fotouhi A., Yousefi M., Aghebati-Maleki L. Nanoparticles and cancer therapy: perspectives for application of nanoparticles in the treatment of cancers. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020;235:1962–1972. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ortíz R., Quiñonero F., García-Pinel B., Fuel M., Mesas C., Cabeza L., Melguizo C., Prados J. Nanomedicine to overcome multidrug resistance mechanisms in colon and pancreatic cancer: recent progress. Cancers. 2021;13:2058. doi: 10.3390/cancers13092058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kasten B.B., Liu T., Nedrowbyers J.R., Benny P.D., Berkman C.E. Targeting prostate cancer cells with PSMA inhibitor-guided gold nanoparticles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:565–568. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Su M., Chen Y., Jia L., Zhang Z. Camptothecin-loaded and manganese dioxide-coated polydopamine nanomedicine used for magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis and chemo-photothermal therapy for lung cancer. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2022;17:6687–6705. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S359300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang C., Wang Y., Xiao W., Chen X., Li R., Shen Z., Lu F. Carboxylated superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles modified with 3-amino propanol and their application in magnetic resonance tumor imaging. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:54. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-10514-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suciu M., Ionescu C.M., Ciorita A., Tripon S.C., Nica D., Al-Salami H., Barbu-Tudoran L. Applications of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in drug and therapeutic delivery and biotechnological advancements. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2020;11:1092–1109. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.11.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abuelmakarem H.S., Hamdy O., Sliem M.A., El-Azab J., Ahmed W.A. Early cancer detection using the fluorescent Ashwagandha chitosan nanoparticles combined with near-infrared light diffusion characterization: in vitro study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2023;38:37. doi: 10.1007/s10103-022-03678-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mundekkad D., Cho W.C. Nanoparticles in clinical translation for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:1685. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Varlamova E.G., Goltyaev M.V., Mal’tseva V.N., Turovsky E.A., Sarimov R.M., Simakin A.V., Gudkov S.V. Mechanisms of the cytotoxic effect of selenium nanoparticles in different human cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:7798. doi: 10.3390/ijms22157798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huai Y., Zhang Y., Xiong X., Das S., Bhattacharya R., Mukherjee P. Gold nanoparticles sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine. Cell Stress. 2019;3:267–279. doi: 10.15698/cst2019.08.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ma Y.C., Zhu Y.H., Tang X.F., Hang L.F., Jiang W., Li M., Khan M.I., You Y.Z., Wang Y.C. Au nanoparticles with enzymemimicking activity-ornamented ZIF-8 for highly efficient photodynamic therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7:2740–2748. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00333a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chaudhari R., Nasra S., Meghani N., Kumar A. MiR-206 conjugated gold nanoparticle based targeted therapy in breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:4713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peng J., Wang R., Sun W., Huang M., Wang R., Li Y., Wang P., Sun G., Xie S. Delivery of MiR-320a-3p by gold nanoparticles combined with photothermal therapy for directly targeting Sp1 in lung cancer. Biomater. Sci. 2021;9:6528–6541. doi: 10.1039/d1bm01124c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aikins M.E., Xu C., Moon J.J. Engineered nanoparticles for cancer vaccination and immunotherapy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:2094–2105. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li Y., Ke J., Jia H., Ren J., Wang L., Zhang Z., Wang C. Cancer cell membrane coated PLGA nanoparticles as biomimetic drug delivery system for improved cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2023;222:113131. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Malik Z., Parveen R., Abass S., Irfan Dar M., Husain S.A., Ahmad S. Receptor-mediated targeting in breast cancer through solid lipid nanoparticles and its mechanism. Curr. Drug Metab. 2022;23:800–817. doi: 10.2174/1389200223666220416213639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rashidzadeh H., Seidi F., Ghaffarlou M., Salehiabar M., Charmi J., Yaray K., Nosrati H., Ertas Y.N. Preparation of alginate coated Pt nanoparticle for radiosensitization of breast cancer tumor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;233:123273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang J., Zhang Y., Liu C., Zha W., Dong S., Xing H., Li X. Multifunctional lipid nanoparticles for protein kinase N3 shRNA delivery and prostate cancer therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2022;19:4588–4600. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xiao Y., Yao W., Lin M., Huang W., Li B., Peng B., Ma Q., Zhou X., Liang M. Icaritin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles activate immunogenic cell death and facilitate tumor recruitment in mice with gastric cancer. Drug Deliv. 2022;29:1712–1725. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2079769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin M., Yao W., Xiao Y., Dong Z., Huang W., Zhang F., Zhou X., Liang M. Resveratrol-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticle for tumor-targeted therapy of gastric cancer. Bioengineered. 2021;12:6343–6353. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1971507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Debele T.A., Yeh C.F., Su W.P. Cancer immunotherapy and application of nanoparticles in cancers immunotherapy as the delivery of immunotherapeutic agents and as the immunomodulators. Cancers. 2020;12:3773. doi: 10.3390/cancers12123773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang R., Xu J., Xu L., Sun X., Chen Q., Zhao Y., Peng R., Liu Z. Cancer cell membrane-coated adjuvant nanoparticles with mannose modification for effective anticancer vaccination. ACS Nano. 2018;12:5121–5129. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b09041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bauleth-Ramos T., Shahbazi M., Liu D., Fontana F., Correia A., Figueiredo P., Zhang H., Martins J.P., Hirvonen J.T., Granja P., et al. Nutlin-3a and cytokine co-loaded spermine-modified acetalated dextran nanoparticles for cancer chemo-immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27:1703303. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201703303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]