Abstract

Background

The development of nursing students’ ability to care for children is an important part of their nursing education. However, nursing students’ understanding of children’s experiences in healthcare is vague. The traditional lecture approach is not conducive to the cultivation of humanistic care competencies for hospitalized children.

Objectives

This study aimed at exploring the effectiveness of narrative pedagogy on developing nursing students’ ability to care for hospitalized children.

Design

A quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group pre-test and post-test design.

Setting

and participants: A purposive sampling method was used for this study. The study participants included 588 first-year nursing students in four classes at a university in western China. The students enrolled in a nursing humanistic curriculum were divided into an experimental group (295 students) and a control group (293 students).

Methods

During the 5 weeks of hospitalized children’s care program, the experimental group received narrative pedagogy, while the control group received traditional teaching with 2 credit hours per week. Data were collected quantitatively using the Caring Ability Inventory (CAI), as well as qualitatively through individual interviews and reflective diaries.

Results

The average scores on the CAI and subscales significantly improved for both groups. As a result of controlling for the effect of pre-test scores, the experimental group had significantly higher post-test scores on the CAI than the control group. Qualitative content analysis demonstrated that narrative pedagogy enhanced nursing students’ emotional experiences and facilitated their understanding of the caring practice for sick children.

Conclusion

Narrative pedagogy has positive implications for improving students’ care competencies for hospitalized children.

Keywords: Narrative pedagogy, Nursing students, Caring ability, Children

1. Introduction

With the implementation of family planning in China, people are increasingly concerned about children’s health, leading to demands for improved care quality for children. As a special group, children have more complex care needs; they are young, have limited cognition, and are emotionally dependant on adults. Additionally, children are accompanied by anxious parents, who also require patient and sensitive handling by nurses – for instance, when a child is sick and hospitalized, their parents become nervous and anxious, and the slightest carelessness by a nurse may result in complaints from the family members.

The nursing profession is linked intrinsically to human health and life, emphasizing care for the ‘whole person’ [1]. Humanistic care ability of nursing refers to nurses’ ability to externalize their inner humanistic qualities into their behaviour of serving patients [2], listen to the needs and desires of patients, understand their emotions, communicate with them, and realize the value of life to facilitate the development of therapeutic relationships [3]. In particular, paediatric nurses require strong humanistic caring abilities to effectively perform clinical practice and provide high-quality care for hospitalized children and their families. Following this humanistic nursing model in the paediatric ward leads to improved parents' satisfaction, greater identification with nursing professional, and a more harmonious nurse-patient relationship [4].

As a backup for clinical nurses, nursing students also need to receive humanistic education and develop humanistic caring skills. In China, humanistic courses are primarily provided in the form of lectures with very few opportunities for students to experience real-world scenarios outside the classroom. Moreover, humanistic education for nursing students prioritizes providing care for adults instead of addressing the needs of patients from different age groups, such as children. Such problems in traditional humanistic education result in unsatisfactory teaching effects [5]. Studies [6,7] have shown that the humanistic care ability of nursing students is low, and most of them lack an understanding of the concept of caring for children. Therefore, developing a humanistic caring ability for unwell children is an essential professional competency for nursing students.

1.1. Background

Narrative pedagogy refers to the use of narrative storytelling to explore and analyse the lived experiences of students, teachers, and medical personnel involved in nursing education [8], as well as to promote students to throw themselves into reflective thinking and experience sharing, thus, providing an alternative method of learning for students [9,10]. The process of narrative pedagogy can promote the transformation of nursing education from an emphasis on teaching content to an emphasis on the learner’s emotional experience. Nursing students in the lower grades in China lack opportunities to attend hospitals for internships. Many courses, including humanities courses, are completed in the classroom, resulting in their lack of understanding of real clinical situations. Narrative teaching can be used in a classroom setting to create a visual and perceptible experience for nursing students to perceive and experience humanistic care through care stories, poetry, music, pictures, and other rich artistic expressions [11]. Integrating narrative pedagogy into nursing education setting fosters students ability to develop problem-solving skills, critical thinking, emotional communication, and empathy, and improves their professional identity in their nursing career [[12], [13], [14]]. Stone [15] used narrative materials including autobiographies, illustrated texts, and picture books to help nursing students uncover embedded meanings, values, and beliefs in undergraduate mental health nursing education. Kirkpatrick [16] conducted narrative education by interpreting stories in films and literature to help students perceive and understand life in undergraduate geriatric care courses. Larocco [17] guided students to read real disease experience stories written by patients and their family members in nursing teaching, to help students understand their feelings and develop empathy for patients and their families.

The concept of humanistic care emphasizes the overall care of patients, implying that nursing students must have the competence to understand the requirements of patients and their families. However, the quality of humanistic care depends on subjective emotion, which has implicit and contextual characteristics. Care ability needs to be acquired through continuous humanistic practice and experience rather than by relying solely on traditional teaching. Narrative teaching is an effective method of immersion learning for nursing students. Students can improve their quality of care by understanding, listening, and interpreting patients’ stories, as well as linking these to their own experiences. In China, many researchers regard narrative teaching as an effective strategy for developing the humanistic care abilities of nursing students, demonstrating that narrative pedagogy has a certain effect on the improvement of their humanistic care ability [[18], [19], [20]]. However, few studies have specifically explored the effects of narrative pedagogy on nursing students’ ability to care for hospitalized children. Therefore, this study applied narrative pedagogy in developing nursing students’ humanistic care ability for sick children, allowing paediatric nurses to share stories of hospitalized children and providing students with an opportunity to feel the illness experience of children and their families.

1.2. Research questions

The main research question of this study sought to identify the effects of the narrative pedagogy intervention on the development of humanistic care ability amongst nursing students for the care of sick children.

It was hypothesised that nursing students who completed the narrative pedagogy intervention would report higher scores on the Caring Ability Inventory (CAI) scale as compared to students in the control condition.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted a mixed-methods quasi-experimental, non-equivalent control group pre-test and post-test study by simultaneously collecting quantitative and qualitative data. Post-study individual interviews and reflection diaries were used as qualitative data to enhance our understanding of the quantitative survey’s findings.

2.2. Setting and participants

The participants in this study were chosen by purposive sampling of the first-year full-time nursing undergraduates attending a humanistic curriculum at a university in Western China. The participants had to take fundamental courses about interpersonal relations and communication and had no previous experience of the paediatric nursing curriculum. Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) enrolled in the bachelor’s degree nursing humanistic curriculum, and (3) voluntarily participated in the study. The participants who dropped out of the course or decided not to participate were excluded. All nursing students understood the purpose of the study and volunteered to participate.

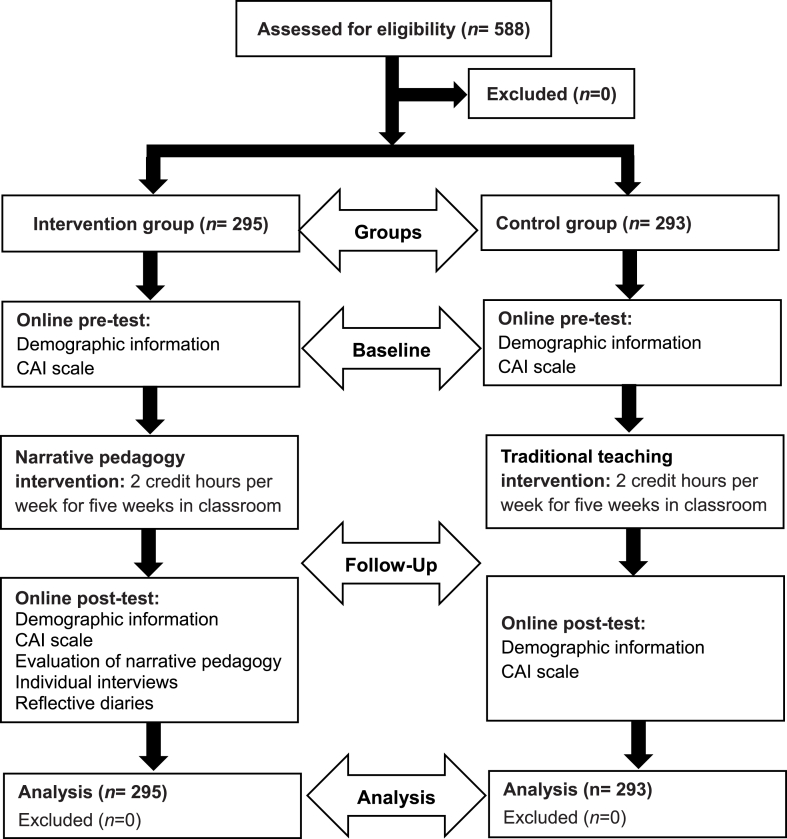

The study had a total of 588 eligible participants from four classes, which they were allocated to at the time of admission. To prevent students from the same class placed in different conditions from comparing their experiences and sharing information across, the 588 students were divided into two groups according to the original classes. Specifically, the four classes were randomly ranked, the first two classes were arranged as the experimental group (n = 295) and the other two classes were the control group (n = 293). During the study, no student refused to participate or withdrew their consent during the study (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram outlining the study processes.

2.3. Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Chong Qing Medical University in March 2021. The participants were informed of the research purpose, necessary activities, provided assurance of confidentiality, their voluntary participation and right to withdraw from the study at any time. Informed consent form was signed by all participants prior to beginning the online survey.

2.4. Research procedures

As a teaching module in a course entitled ‘nursing humanistic curriculum’, the course on care education for hospitalized children lasted for five weeks, with 2 credit hours each week in the 1st year of the four-year nursing program from April 12, 202,1 to May 15, 2021. The control group received traditional lectures, while the experimental group were taught using narrative pedagogy.

2.4.1. The control group

The traditional teaching method was adopted to impart education on caring for unwell children. The teacher uploaded learning materials and set tasks for students’ preparation through an online teaching platform one week before the class. The lessons were primarily taught through theoretical lectures, which were supplemented by questions and class discussions. After the class, students could consult the learning resources on the online teaching platform for continuous learning to consolidate the lessons.

2.4.2. The experimental group

Narrative pedagogy was adopted, emphasizing students’ learning experiences and perceptions of care. The specific implementation is as follows:

2.4.2.1. Pre-course preparation

The subject leader and teachers involved in narrative teaching attended a training to learn the theory and development of narrative pedagogy, shift their teaching concepts, and master teaching methods. Consensus regarding the course outline and objectives was attained after several meetings and consultations. The content of narrative pedagogy was centred around the humanistic care of new-borns in pain, children with cancer, children with autism, humanistic practices in the paediatric ward and reflective sharing of experiences. Each narrative was piloted in the form of collective course preparation and trial lectures to ensure the quality of narrative pedagogy.

2.4.2.2. Collection of narrative materials

Paediatric nurses from hospitals with experience in clinical practice and humanities teaching were selected as teachers of narrative teaching style. They researched and compiled narrative materials based on the characteristics of the teaching content and their work experience in their specialized fields. These materials could be clinical stories, film clips, short films, literature, biographies, and diaries, among others, which contained humanistic emotions. Moreover, students were fully involved in the recounting of narratives by sharing their experiences in real practice settings.

2.4.2.3. Implementation of narrative pedagogy

One week before the class, teachers used the online teaching platform to upload learning materials and encourage students to independently consult more background knowledge based on the teaching theme of the week. Alternatively, students were asked to recall their life experiences or nursing practice experiences around the teaching theme. Consequently, students could deepen their understanding of the narrative theme’s content through the pre-course material.

In the classroom, teachers created visual and perceptible experiences for nursing students to perceive children’s care through rich artistic expressions, such as humanistic care stories, pictures, videos, and short films. The teaching theme for the first week was ‘caring for new-borns in pain’, in which the teacher introduced pictures of new-borns with painful expressions and a video of pricking a new-born’s heel for blood collection to trigger nursing students’ care and compassion. The story ‘My Affinities with the Neonatal Ward’, adapted from a real clinical story, was recounted to allow nursing students to witness painful experiences in the neonatal ward and understand care measures for new-borns in pain.

The second lesson ‘Caring for Children with Autism’ began with the short film ‘Born to be human’, to introduce autistic children to nursing students. Through the short film ‘On the Road’, nursing students understood the hardships of families with autistic children. A real clinical story, ‘A desperate father’s complaint’, was shared, followed by a discussion on the psychological needs and priorities required in care support for parents of children with autism.

In the third lesson, ‘Caring for Children with Cancer’, a sand painting video of ‘The Sky of a Girl aged Sixteen’ was played by the teacher. The video told the story of a 16-year-old girl experiencing a series of physical and psychological changes after unfortunately developing nasopharyngeal cancer, which helped nursing students understand the feelings and psychological needs of children with cancer. In addition, nursing students were also shown the measures of hospice care for children with cancer. Through the presentation of the narrative materials, the nursing students entered the inner world of the children and their caregivers, enhanced their understanding of them, and stimulated thoughts about their daily practice of childcare. The teacher then revealed the meaning and value hidden in the story through the interpretation and analysis of the materials, and stimulated the nursing students' humanistic caring emotions through guided questions to provoke their thinking and expression.

In the fourth lesson, during the humanistic practice at the paediatric ward, nursing students observed the environment, facilities, nurses’ stories, and quality care measures in the paediatric ward to truly experience the atmosphere of caring. Concurrently, they were immersed in interactions with children and their families to learn and record their stories. At the end of the practice, students were required to write a reflective diary based on these recorded stories and their own impressions of them. In the fifth lesson, students discussed their reflective writing and experiences from the previous lesson, and shared their thoughts about the feelings of the children and their families.

2.5. Measures

A combination of quantitative and qualitative research was used to conduct the evaluation. The CAI was used in the experimental group to investigate students’ nursing humanistic care competencies before and after the implementation of narrative pedagogy, and the control group was simultaneously investigated. A narrative pedagogy assessment was conducted, and a reflective diary was maintained in the experimental group to understand the students’ evaluation and perceptions of the effectiveness of the pedagogy.

2.5.1. Caring Ability Inventory (CAI)

Developed by Nkongho [21] in 1990 and translated and revised into a Chinese version by Xu [22],CAI was used to measure a person’s ability to care for others. The scale consisted of 37 items in three dimensions: knowing (14 items), courage (13 items), and patience (10 items). A seven-point Likert scale was used, with scores ranging from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Higher scores indicated greater caring competencies. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were as follows: 0.86 for the total scale, 0.79 for the comprehension dimension, 0.77 for the courage dimension, and 0.72 for the patience dimension.

2.5.2. Students’ evaluation of narrative pedagogy

At the end of the narrative pedagogy lessons, a self-administered questionnaire was used to investigate students’ evaluations of narrative pedagogy in the experimental group. This questionnaire was created ad-hoc in Chinese and verified by independent experts of nursing for its clarity, coherence, and relevance. It consisted of seven items, which were scored on a 3-point Likert scale which included ‘very helpful’, ‘somewhat helpful’, and ‘not helpful’. The higher the score, the more the student agreed with the content of the item.

2.5.3. Qualitative data collection

Qualitative data were collected using individual interviews and students’ reflective diaries. A semi-structured interview outline was used to conduct the interviews: (1) Can you tell me what you think of the children now? (2) How do you feel when listening to the teacher and the classmate telling stories? (3) What do you gain and feel from this course? The criteria for enrolment in the study included being in the experimental group, having completed the full narrative pedagogy lessons and willing to participate in the interview to share their experiences. Purposive sampling was undertaken to recruit eight students for face-to-face interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 20–30 min. The reflection diaries of 295 students from the experimental group were collected, read, and analysed carefully to summarise their feelings and reflective questions.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The quantitative analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. Means and standard deviations were adopted to describe variables data. Frequencies and composition ratios described the counting data. Background characteristics and pre-test outcomes between groups were compared using the independent sample t-test and the chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Comparing the differences within the group before and after the measurement was done using the paired t-test. Analysis of Covariance (One-way ANCOVA) was used to compare the post-test differences between groups by controlling for a covariate (pre-test scores) for pre-existing differences in the outcome variables.

Qualitative data were analysed using inductive content analysis [23,24]. The audio recordings of the interviews were converted into interview transcripts within 24 h. Two researchers independently read and re-read interview transcripts and reflection diaries line by line, proceeded with a preliminary process of open coding, and grouped conceptual elements into the sub-themes. Then, similar sub-themes were placed together to form the main themes. Finally, the two researchers contrasted the coding schemes, and reached a consensus on data analysis. The validity and reliability of the data obtained from this qualitative research were evaluated in four ways: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability [25]. To enhance the credibility and dependability of the study, all researchers received qualitative interview training. The data obtained from the interviews were also reviewed and confirmed by the participants, who then provided some feedback regarding the data. We collected qualitative data from students in two ways to ensure objectivity and authenticity of student experience. The transferability of the findings was secured by providing the exact remarks of participants and providing further details about the study methodology, sampling criteria, data collection process, and context of data analysis. To ensure the confirmability of the findings, all stages of the research were accurately recorded and confirmed by a third party with expertise on qualitative research.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of the two groups

A total of 588 students were enrolled in this study, with a mean age of 21 and 23 years in the experimental and control groups, respectively. Of these participants, 83 were male (14.12%), and 505 were female (85.88%). There were no significant differences between the groups in demographic characteristics and CAI scores before the intervention (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and baseline data of participants.

| Variable | Experimental group (n = 295) Mean ± SD/n (%) | Control group (n = 293) Mean ± SD/n (%) | X2/t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.11 ± 1.348 | 18.95 ± 0.771 | 1.765 | 0.078 |

| Gender | 0.391 | 0.532 | ||

| Male | 39(13.22%) | 44(15.02%) | ||

| Female | 256(86.78) | 249(84.98%) | ||

| Residence | 1.922 | 0.230 | ||

| Urban | 39(13.22%) | 44(15.02%) | ||

| Rural | 256(86.78) | 249(84.98%) | ||

| Experience contact with children | 89(30.17%) | 92(31.40%) | 2.631 | 0.125 |

| CAI | ||||

| Total | 174.00 ± 17.86 | 174.57 ± 16.81 | −0.398 | 0.690 |

| Knowing | 70.90 ± 7.91 | 70.56 ± 7.81 | 0.524 | 0.600 |

| Courage | 48.90 ± 6.39 | 49.28 ± 6.34 | −0.724 | 0.469 |

| Patience | 54.19 ± 6.10 | 54.72 ± 5.37 | −1.118 | 0.264 |

3.2. Comparison of outcomes within and between the two groups

After the completion of the intervention, within-group analyses of the results indicated that the scores on the CAI significantly improved for the groups, including knowing, courage, and patience. As a result of controlling for the effect of pre-test scores, the experimental group had significantly higher post-test scores on the CAI and its subscales than the control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of caring ability within and between the two groups.

| Variables | Groups | Pre-test Mean (SD) | Post-test Mean (SD) | ta/p | Fb | p/ηp2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAI | Experimental | 174.00 ± 17.86 | 181.43 ± 19.16 | 0.395/<0.001 | 556.09 | <0.001/0.013 |

| Control | 174.57 ± 16.81 | 177.42 ± 18.36 | 0.041/<0.001 | |||

| Knowing | Experimental Control | 70.90 ± 7.91 | 73.52 ± 8.21 | 0.439/<0.001 | 888.26 | <0.001/0.021 |

| Control | 70.56 ± 7.81 | 71.15 ± 8.04 | 0.061/<0.001 | |||

| Courage | Experimental Control | 48.90 ± 6.39 | 51.20 ± 6.86 | 0.447/<0.001 | 372.03 | <0.001/0.009 |

| Control | 49.28 ± 6.34 | 50.16 ± 6.43 | 0.091/<0.001 | |||

| Patience | Experimental Control | 54.19 ± 6.10 | 56.70 ± 6.12 | 0.114/<0.001 | 104.02 | <0.001/0.003 |

| Control | 54.72 ± 5.37 | 56.10 ± 6.07 | −0.023/0.01 |

Paired t-test.

One-way ANCOVA, ηp2 = partial eta squared.

3.3. Evaluation of narrative pedagogy by students in the experimental group

Most students thought that narrative pedagogy helped improve their interest in learning, enhanced awareness of humanistic nursing care, increased empathy and sympathy for children and their parents, enhanced professional identity, and improved communication skills (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nursing students’ evaluation of the effectiveness of narrative pedagogy.

| Item | Very helpful | Somewhat helpful | Not helpful |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative pedagogy helped me increase learning interest and motivation | 167(56.61%) | 120(40.68%) | 8(2.71%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me increase empathy and compassion for children and their parents | 190(64.41%) | 105(35.59%) | 0(0.00%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me improve sensitivity to the needs of children and their parents | 168(56.95%) | 121(41.02%) | 6(2.03%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me increase the awareness of the humanistic care and respect for life | 190(64.41%) | 103(34.92%) | 2(0.68%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me develop the skills of problem-solving, critical thinking, and reflective thinking | 175(59.32%) | 115(38.98%) | 5(1.69%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me understand the value of nursing profession and enhance professional identity | 184(62.37%) | 109(36.95%) | 2(0.68%) |

| Narrative pedagogy helped me improve the ability to communicate with patients | 181(61.36%) | 109(36.95%) | 5(1.69%) |

3.4. Themes identified through interviews and reflective diaries

3.4.1. Enhanced emotional experience of nursing students

In traditional teaching, nursing students’ perception of humanistic care stemmed from theoretical lectures by teachers. They lacked a realistic understanding of the scenarios in the hospital and empathy with patients and their families’ sentiments. Narrative pedagogy carries vivid stories of care into the classroom, creating real-life or quasi-real-life clinical situations for nursing students to perceive care. A nursing student said, ‘The teacher told us about many stories in class, and I learned how difficult it is for patients and their families. I shed tears especially after reading about the girl’s difficult journey to fight cancer. I could feel her pain and the torture she went through, and this is probably what the teacher called empathy’. The diary of another student stated as follows: ‘I was impressed by my last hospital attachment. I could see crying children, anxious parents, and the backs of busy nurses everywhere in the wards; I could really see their faces, feel their expressions, and emotions. I can also see the gentleness and patience of the nurses who calmed the children and parents’. Through this process, the students could not only empathize and sympathize with the emotions of the children and parents but also experienced a sense of responsibility and a purposeful mission as a nurse.

3.4.2. Deepened perception of child care practices

In the past, humanities education in nursing curriculum has been directed at adults or elderly people, and nursing students had little experience and knowledge of caring for children and childcare practices. As a student mentioned, ‘I realized that the new-born could feel pain when I saw them crying in the process of a heel blood prick, and mothers’ reassurance, swaddling, kangaroo care, and oral sucrose can help relieve their pain’. Another student wrote as follows: ‘I have read articles about autistic families before. After watching the short films and videos shown by the teacher, I better understand the process of intervention and treatment for autistic children and the hardships experienced by autistic families. I think humanistic care should not only be provided to autistic children but also their parents and their psychological and social support needs merit our attention. I heard from my teacher that there are volunteer activities for autistic children, and I would like to get involved’. The practice of caring for unwell children and their families manifests itself in multiple ways and nursing students’ willingness to understand and implement them shows that the inner sense of caring has been externalized into caring behaviour.

4. Discussion

This quasi-experimental study explored narrative teaching as a strategy to develop nursing students’ humanistic care ability for hospitalized children. Our findings showed that nursing students had low humanistic caring ability, which is in line with findings from a longitudinal study on the caring ability of Chinese nursing students pre- and post-internship [6]. In China, nursing undergraduate education placed a greater emphasis on developing nursing students’ professional knowledge and practical skills. In contrast to the 15–25% in nations like the US, UK, and Germany, the caring ability courses in Chinese nursing schools only make up 8% of the entire courses [26]. Additionally, most courses solely provide classroom education and do not provide opportunities for clinical experience.

After completing an intensive 5-week training program, students in the experimental group acquired positive perceptions, greater courage, and increased patience in their ability to care for hospitalized children compared with students in the control group. The scores of CAI and its subscales improved after the intervention, in the experimental and control groups. However, the comparison between the two groups indicated that this improvement effect on students’ care ability was higher in the experimental group. This demonstrates that narrative pedagogy is more effective than traditional teaching methods in cultivating nursing students’ care ability. In keeping with findings of Hu et al. [6], cognitive scores were highest among the three CAI dimensions, followed by patience and courage. This may be the result of nursing being a profession dominated by women. Nursing students, especially lower grade students with less practical experience, demonstrate more patience but less courage in actively communicating with patients. Additionally, nursing students in the experimental group evaluated narrative pedagogy as helpful in enhancing their awareness of humanistic nursing care, increasing their empathy for children and their parents, enhancing their professional identity, and improving their communication skills.

The power of narrative pedagogy is in its ability to express and share contextual experiences related to emotions, morality, values, and culture to create changes within the learner. Qualitative analysis in this study supports that narrative pedagogy have positive impacts on nursing students’ learning experiences and perceptions of caring practice; it enables students to engage in perspective-building through stories, facilitating empathy and a deeper understanding of people’s experiences in healthcare [27]. This finding was concurrent with that of an integrative review [28] which indicated that narrative pedagogy was useful to assist students in meeting important learning outcomes, such as interconnectedness with others including empathy, compassion, cultural sensitivity, and caring. Through this, it appears that students felt empowered and more connected to others. In fact, storytelling within a narrative pedagogical framework allowed students with multiple learning styles to actively participate, which fostered a trusting, safe environment for understanding the illness experience and care needs of patients. Furthermore, nurses were able to share real stories about patients in the classroom, which helped prepare students for the realities of nursing practice. A well-constructed narrative required teachers and students to engage in collaborative communication and discussion, which is important to achieve shared understanding. Additionally, through critical analysis of these stories, students could gain insight into their own and others’ experiences, which could aid them in the process of developing their professional identity [29]. In addition, the internship in the paediatric ward placed nursing students in a humanistic environment, allowing them to truly feel the professional values of nurses, experience the empathetic emotions of patients, and identify meaningful points in their stories. The reflective diary played an important role in narrative pedagogy as well. Such reflective thinking facilitates exploration and evaluation of one’s own and others’ experiences, thereby influencing how one responds to similar situations in the future [30].

4.1. Implications for nursing education

Many studies have focused on caring for adults and the elderly, and relatively few studies have explored nurses’ caring abilities for children. Typically, children of different ages have differing care needs and ways of expressing their emotions. Nursing students’ caring ability for children is crucial in the care they provide to their younger patients. Thus, medical schools should strengthen the cultivation of this ability and emphasize on child-care education. Humanities and moral education should be incorporated into paediatric specialist courses. Lecturers should also integrate the concept of humanistic care into teachings of disease care, adopting a variety of teaching methods from humanities education, such as narrative pedagogy, contextual experience methods, role-playing, group discussions, hospital practice, and so on. Nursing students’ perception and experience of care should be prioritized, emphasizing the internalization of humanistic knowledge and externalization of humanistic spirit to strengthen humanistic behaviour. Second, medical schools should enrich the humanities curriculum by introducing courses on the philosophy of life, bioethics, multiculturalism, emotion management, health promotion, narrative medicine, and the psychology of childhood illnesses. In addition, social practice activities such as cultural activities, humanities clubs, and volunteer services should be increased to transform humanistic knowledge into humanistic practice and to cultivate nursing students’ humanistic care spirit in multiple dimensions and perspectives.

4.2. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, purposive sampling was used when choosing respondents because it is very difficult to conduct a randomized double-blind study within an academic setting. To minimize selection bias, we used ANCOVA to adjust the pre-test values and balance baseline data between the groups. Second, the measures available for this study were limited; currently, there is no specific tool to evaluate nursing students’ caring ability for hospitalized children. Additionally, the reliability and validity of the self-administered questionnaire used to investigate evaluations of narrative pedagogy have not yet been verified. For this reason, our results are supplemented by qualitative data. Third, the short duration of the narrative pedagogy intervention could lead to unreliable results. In the future, we aim to further strengthen research quality, increase the number of weeks for narrative teaching, and develop a scale suitable for evaluating the caring ability for unwell children to make the results more credible and replicable.

5. Conclusion

This study explored the application of narrative pedagogy in the development of nursing students’ caring ability for hospitalized children. Nursing students’ understanding of children and their experiences in a healthcare setting are underdeveloped, and narrative education provides students with the opportunity to develop their understanding through contact, interaction and perspective-building towards unwell children and their families. Our findings revealed that nursing students’ overall competence to care for hospitalized children considerably increased, demonstrating a beneficial correlation between narrative pedagogy and caring ability. Narrative pedagogy is a useful strategy to increase students’ interest and experience in learning, enhance their empathy and sensitivity to the needs of children and parents, as well as deepen their understanding of the meaning of nursing work. The results of this study provide insights towards applying narrative pedagogy to enhance education on children’s care. Future studies need to explore more diverse curricula and teaching methods to improve nursing students’ caring ability for hospitalized children and families.

Author contribution statement

Fang Liu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Yanbin Yang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Hengyu Zhou: Performed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Lin Mo; Hongyao Leng; Cui Cui: Performed the experiments; Analysed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Chongqing Medical University Future Medical Youth Innovation Team Support Program. Grant number - W0008.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants involved in this study and making this study possible. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15499.

Contributor Information

Fang Liu, Email: fangliu@cqmu.edu.cn.

Yanbin Yang, Email: yanbinyang123@qq.com.

Hengyu Zhou, Email: zhouhengyu@cqmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Frisch N., Dossey B., Guzzeta C., Quinn J. Aspen; Gaithersburg, MD: 2000. AHNA Standards of Holistic Nursing Practice: Guidelines for Caring and Healing. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson J. Colorado associated University Press; Colorado: 1985. Nursing: the Philosophy and Science of Caring; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers C.R. The foundations of the person-centered approach. Dialect. Humanism. 1981;8(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong X., Liu X., Sheng Y. The effect of the humanistic care teaching model on nurse patient conflict and nurse turnover intention in a pediatric outpatient department: results of a randomized trial. Transl. Pediatr. 2021;10(8):2016–2023. doi: 10.21037/tp-21-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu H.R. 2017. A Theoretical Construction of Narrative Nursing and its Curriculum Development and Empirical Study. (The Second Military Medical University) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu S., Chen J., Jiang R., Hu H., Hu Z., Gao X., Chen W. Caring ability of nursing students pre- and post-internship: a longitudinal study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-00921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y., Zhang Y., Liu M., Zhou L., Zhang J., Tao H., Li X. Research on the formation of humanistic care ability in nursing students: a structural equation approach. Nurse Educ. Today. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diekelmann N. Narrative Pedagogy: Heideggerian hermeneutical analyses of lived experiences of students, teachers, and clinicians. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2001;23(3):53–71. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews C.A., Ironside P.M., Nosek C., Sims S.L., Swenson M.M., Yeomans C., Young P.K., Diekelmann N. Enacting narrative pedagogy. The lived experiences of students and teachers. Nurs. Health Care Perspect. 2001;22(5):252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ironside P.M. Narrative pedagogy: transforming nursing education through 15 Years of research in nursing education. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2015;36(2):83–88. doi: 10.5480/13-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao C.C., Jiang A.L. The application of narrative education in nursing humanistic care education. Nurs. J. Chinese PLA. 2013;30(11):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazarian P.K., Fernberg L.M., Sheehan K.D. Effectiveness of narrative pedagogy in developing student nurses’ advocacy role. Nurs. Ethics. 2016;23(2):132–141. doi: 10.1177/0969733014557718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ironside P.M. Enabling narrative pedagogy: inviting, waiting, and letting be. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2014;35(4):212–218. doi: 10.5480/13-1125.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laver S., Croxon L. Narrative pedagogy with evolving case study-A transformative approach to gerontic nursing practice for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015;15(5):341–344. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone T.E., Levett-Jones T. A comparison of three types of stimulus material in undergraduate mental health nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today. 2014;34(4):586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkpatrick M.K., Brown S. Narrative pedagogy: teaching geriatric content with stories and the "Make a Difference" project. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2004;25(4):183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larocco S.A. Assisting nursing students to develop empathy using a writing assignment. Nurs. Educat. 2010;35(1):10–11. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181c41fb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang X.J., Wu J.P., Wang Q., Zhang X.W. The influence of narrative education on the humanistic caring quality of undergraduate nursing students. Chinese J. Nurs. Edu. 2017;14(12):889–892. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong Y.Z., Yang Q.M., Qiu Z.C. Application of narrative teaching of nursing in the course of Humanity Cultivation for Nurses. Chinese J. Nurs. Edu. 2016;13(9):675–679. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu P.P., Hu R.F., Lin X.Y., Wang X.Y. The application of narrative pedagogy in the obstetrics and gynecology nursing courses for undergraduate students. Chinese J. Nurs. Edu. 2019;16(2):114–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nkongho N.O. Springer; New York: 1990. Measurement of Nursing Outcomes. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J. 2008. A Study on the Caring Ability of Hospital Nursing Staff. (Huazhong University of Science and Technology) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elo S., Kaariainen M., Kanste O., Polkki T., Utriainen K., Kyngas H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 2014;4(1) doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lusardi, Paula Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. Nurs. Res. 1996;45(1):62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q., Ye M., Shen X.P. Review on caring ability of nursing students. Nurs. Res. 2018;32(23):3664–3667. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse J. Radcliffe; London: 2007. Strategies for Healthcare Education: How to Teach in the 21st Century. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brady D.R., Asselin M.E. Exploring outcomes and evaluation in narrative pedagogy: an integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today. 2016;45:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McAllister M., John T., Gray M., Williams L., Barnes M., Allan J., Rowe J. Adopting narrative pedagogy to improve the student learning experience in a regional Australian university. Contemp. Nurse. 2009;32(1–2):156–165. doi: 10.5172/conu.32.1-2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daryazadeh S., Adibi P., Yamani N., Mollabashi R. Impact of narrative medicine program on improving reflective capacity and empathy of medical students in Iran. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2020;17:3. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2020.17.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.