This multicenter cohort study evaluates racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes among newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with mortality differences among newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) from different racial and ethnic groups?

Findings

In this multicenter cohort study of 1565 patients, Black infants had significantly higher in-hospital mortality compared with other racial and ethnic groups. Hospitals in more racially and ethnically diverse communities were associated with lower 60-day mortality among Black and Hispanic infants, without affecting mortality in White infants.

Meaning

Despite ongoing health outcome disparities in Black infants with CDH, these findings suggest evidence of improved outcomes observed in Black and Hispanic patients managed at hospitals caring for larger racial and ethnic minority patient populations.

Abstract

Importance

There is some data to suggest that racial and ethnic minority infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) have poorer clinical outcomes.

Objective

To determine what patient- and institutional-level factors are associated with racial and ethnic differences in CDH mortality.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter cohort study of 49 US children’s hospitals using the Pediatric Health Information System database from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2020. Participants were patients with CDH admitted on day of life 0 who underwent surgical repair. Patient race and ethnicity were guardian-reported vs hospital assigned as Black, Hispanic (White or Black), or White. Data were analyzed from August 2021 to March 2022.

Exposures

Patient race and ethnicity: (1) White vs Black and (2) White vs Hispanic; and institutional-level diversity (as defined by the percentage of Black and Hispanic patients with CDH at each hospital): (1) 30% or less, (2) 31% to 40%, and (3) more than 40%.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were in-hospital and 60-day mortality. The study hypothesized that hospitals managing a more racially and ethnically diverse population of patients with CDH would be associated with lower mortality among Black and Hispanic infants.

Results

Among 1565 infants, 188 (12%), 306 (20%), and 1071 (68%) were Black, Hispanic, and White, respectively. Compared with White infants, Black infants had significantly lower gestational ages (mean [SD], White: 37.6 [2] weeks vs Black: 36.6 [3] weeks; difference, 1 week; 95% CI for difference, 0.6-1.4; P < .001), lower birthweights (White: 3.0 [1.0] kg vs Black: 2.7 [1.0] kg; difference, 0.3 kg; 95% CI for difference, 0.2-0.4; P < .001), and higher extracorporeal life support use (White: 316 patients [30%] vs Black: 69 patients [37%]; χ21 = 3.9; P = .05). Black infants had higher 60-day (White: 99 patients [9%] vs Black: 29 patients [15%]; χ21 = 6.7; P = .01) and in-hospital (White: 133 patients [12%] vs Black: 40 patients [21%]; χ21 = 10.6; P = .001) mortality . There were no mortality differences in Hispanic patients compared with White patients. On regression analyses, institutional diversity of 31% to 40% in Black patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04-0.78; P = .02) and diversity greater than 40% in Hispanic patients (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.15-0.89; P = .03) were associated with lower mortality without altering outcomes in White patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study of 1565 who underwent surgical repair patients with CDH, Black infants had higher 60-day and in-hospital mortality after adjusting for disease severity. Hospitals treating a more racially and ethnically diverse patient population were associated with lower mortality in Black and Hispanic patients.

Introduction

There is a growing body of evidence that morbidity and mortality are heightened in racial and ethnic minority populations in the US, a discrepancy widely attributed to the effect of health care disparities.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 This is most apparent in the Black and Hispanic communities, affecting not only adults but also infants and young children.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 Black mothers, for example, are more likely to deliver at hospitals with increased rates of complications compared with White mothers.17 The discrepancy is further magnified as Black neonates are more likely to be born preterm with low to very low birth weights, increasing their predisposition to immediate complications.18 After birth, Black infants have been shown to receive care in inferior neonatal intensive care units due to insurance status and financial and racial polarization.19,20,21,22 These disparities may be amplified in neonates with a congenital disease diagnosis, with disparate care affecting both prenatal diagnosis as well as postnatal resuscitation and definitive care strategies.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is one of the most important congenital anomalies managed by pediatric surgeons according to incidence, resource utilization, and cost.23 Failed embryonic closure of the diaphragm in affected fetuses results in intrathoracic abdominal viscera herniation and varying degrees of pulmonary hypoplasia, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac dysfunction at birth.24,25,26 Prenatally diagnosed cases require increased surveillance and, in the most severe cases, fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion has been shown to improve survival with acceptable long-term morbidity.27,28 In the majority of patients, survival is improved with delivery at high-volume, designated CDH centers that have a multidisciplinary care approach and access to adjuvant therapies, including extracorporeal life support (ECLS).29,30 Despite such intensive care, the overall neonatal mortality rate in CDH approaches 25% to 30%.24,25 The mortality rate in CDH may be even higher in racial and ethnic minority patient populations, but these findings are based on data from nearly 20 years ago.31,32,33 Moreover, the impact of disease severity, socioeconomic status (SES), and institution-specific factors on outcome disparities in infants with CDH has not been well elucidated.31,32,33

The primary aim of our study was to evaluate mortality disparities in CDH using a large, contemporary national database. A secondary aim was to determine how institution-specific factors might correlate with clinical outcomes among different racial and ethnic cohorts with CDH. Our group speculated that hospitals serving larger racial and ethnic minority communities might be associated with a survival advantage among Black and Hispanic infants.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, Participants

This was a retrospective, multicenter cohort study using demographic, clinical, and outcome data from the Children’s Hospital Association Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). The PHIS database contains administrative and billing data from 49 children’s hospitals in the US.34 Data quality and reliability are assured by the Children’s Hospital Association, participating institutions, and Truven Health Analytics.35,36 The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis and procedure codes were used to identify patient-level data.

Institutional review board approval was obtained at Johns Hopkins University and exemption of patient consent was granted. Review board approval was deemed exempt at Yale University because the data was publicly available and deidentified. The PHIS database was queried for patients with CDH using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnoses codes between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2020. Patients were included if they were admitted on day of life 0 and underwent surgical repair of their diaphragmatic hernia (ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes, eTable in Supplement 1). Patients who did not undergo surgical repair and those with missing race and ethnicity data were excluded from analysis. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.37

Variables

Data collection included demographic variables, markers of SES, postnatal markers of disease severity, hospital clinical course, and in-hospital outcomes. Household income was measured by median income quartile as determined by the zip code of residence linked to US Census Bureau data.38 Cardiovascular anomalies were defined as heart and great vessel malformations, endocardium diseases, cardiomyopathies, conduction disorders and dysrhythmias, cardiac devices, and/or transplantation.39 Hospital case volume was defined by the mean number of CDH repairs per center from 2015 to 2020. Low case volume was less than 10 cases per year, whereas high case volume was 10 or more cases per year according to prior work.29,40,41

Race and ethnicity reporting in the PHIS database is coded by administrative staff according to hospital-specific guidelines, including patient/guardian self-report or hospital registration assignment.42 Race categories were American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, or other (other included multiracial and unknown). Ethnicity categories were Hispanic/Latino or not Hispanic/not Latino. The racial and ethnic groups that were used in the analysis included Black (Black, non-Hispanic), Hispanic (White or Black Hispanic), and White (White, non-Hispanic). American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or other racial and ethnic groups were excluded due to the relatively low number and thus inability to deduce meaningful or valid results. At each institution, we also quantified institutional-level diversity, defined as the percentage of Black and Hispanic patients with CDH at each hospital (as determined by ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis code; eTable in Supplement 1). Racial and ethnic diversity levels of (1) 30% or less (2) 31%-40%, and (3) greater than 40% were established according to the 2020 US Census data, in which 71% of the US population self-identified as White.43

The primary outcomes of interest were 60-day and in-hospital mortality rates. Three markers of disease morbidity, namely hospital length of stay, discharge to home, and tracheostomy, were used as secondary outcome measures.

Statistical Analysis

A t test was performed for parametric data, whereas a Wilcoxon rank sum was performed for nonparametric data. Continuous data were presented as mean (SD) vs median (IQR). A Pearson χ2 test was used to analyze categorical variables. The majority patient population served as the reference group for each comparison.

Sixty-day mortality trends of Black, Hispanic, and White patients according to institutional-level racial and ethnic diversity were assessed with a Kaplan-Meier estimate and significance was determined with a Wilcoxon (Breslow) test. To account for loss-to-follow-up, a Cox proportional regression analysis was used to compare the outcome of multiple variables on the 60-day risk of mortality. A clustered sandwich estimation by hospital was used to allow for intragroup correlation.44 To reduce the effect of immortal time bias, the person-time variable (day 0) started on the day of surgery. Variables with a known effect on CDH mortality were used in the Cox regression. Downstream effectors and causal intermediates of race were excluded from analyses.45 Statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp). Significance was defined as a 2-sided P≤.05. Data were analyzed from August 2021 to March 2022.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

There were 1893 patients with CDH who underwent surgical repair. There were 328 (17%) patients excluded according to identification as American Indian or Alaskan Native (17 patients), Asian (60 patients), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (7 patients), or other (244 patients). Among the remaining 1565 patients, 188 (12%) were Black, 306 (20%) were Hispanic, and 1071 (68%) were White (Table 1). There was no difference in sex across racial and ethnic groups. The median (IQR) household income of White patients ($57 618 [$45 625-$74 694]) was significantly greater than the income of Black patients ($44 375 [$32 186-$57 207]; z score, 9.0; P < .001) and Hispanic patients ($50 125 [$40 909-$64 332]; P < .001). The White patient population used significantly higher rates of commercial insurance (634 [59%]) compared with Black (27 [14%]; χ21 = 128.9; P < .001) and Hispanic patients (72 [24%]; χ21 = 121.2; P < .001).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Infants With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, by Race and Ethnicity.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 1565) | White (n = 1071) (reference) | Black (n = 188) | P value | Hispanic (n = 306) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 937 (60) | 627 (59) | 117 (62) | .35 | 193 (63) | .16 |

| Female | 628 (40) | 444 (41) | 71 (38) | 113 (37) | ||

| Household income, median (IQR), US $a | 54 278 (43 048-70 152) | 57 618 (45 625-74 694) | 44 375 (32 186-57 207) | <.001 | 50 125 (40 909-64 332) | <.001 |

| Payer status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Commercial | 733 (47) | 634 (59) | 27 (14) | <.001 | 72 (24) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 733 (47) | 372 (35) | 155 (83) | 206 (67) | ||

| Uninsured | 99 (6) | 65 (6) | 6 (3) | 28 (9) | ||

| Disease severity | ||||||

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 37.5 (2) | 37.6 (2) | 36.6 (3) | <.001 | 37.8 (2) | .09 |

| Birthweight, mean (SD), kg | 3.0 (1) | 3.0 (1) | 2.7 (1) | <.001 | 3.1 (1) | .15 |

| Apgar score at 1 min, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3) | 4.6 (3) | 3.7 (3) | <.001 | 4.8 (3) | .33 |

| Apgar score at 5 min, mean (SD) | 6.4 (3) | 6.5 (3) | 5.6 (3) | <.001 | 6.7 (2) | .24 |

| Cardiovascular anomalies, No. (%)b | 759 (48) | 506 (47) | 101 (54) | .10 | 152 (50) | .45 |

| Institutional | ||||||

| Urban center, No. (%) | 1259 (80) | 822 (77) | 176 (94) | <.001 | 261 (85) | <.001 |

| Volume, No. (%) | ||||||

| Low volume | 884 (56) | 567 (53) | 107 (57) | .31 | 210 (69) | <.001 |

| High volume | 681 (44) | 504 (47) | 81 (43) | 96 (31) | ||

| Racial and ethnic diversity, No. (%)c | ||||||

| ≤30% | 465 (30) | 393 (37) | 51 (27) | <.001 | 21 (7) | <.001 |

| 31%-40% | 427 (27) | 334 (31) | 41 (22) | 52 (17) | ||

| >40% | 673 (43) | 344 (32) | 96 (51) | 233 (76) |

Median household income was estimated by zip code.

Cardiovascular anomalies include heart and great vessel malformations, endocardium diseases, cardiomyopathies, conduction disorders and dysrhythmias, cardiac devices, and/or transplantation.

Racial and ethnic diversity is the percentage of Black and Hispanic patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia at each institution.

White infants, compared with Black infants, were more likely to be full term (mean [SD] gestational age, White: 37.6 [2] weeks vs Black: 36.6 [3] weeks; difference, 1.0 week; 95% CI for difference, 0.6-1.4; P < .001), have a higher mean (SD) weight (White: 3.0 [1.0] kg vs Black: 2.7 [1.0] kg; difference, 0.3 kg; 95% CI for difference, 0.2-0.4; P < .001), and have higher mean (SD) Apgar scores at 5 minutes (White: 6.5 [3] vs Black: 5.6 [3]; difference, 0.9; 95% CI for difference, 0.4-1.3; P < .001). White patients were treated at high-volume centers at a comparable rate to Black patients, but more often than Hispanic (White: 504 [47%] vs Hispanic 96 [31%]; χ21 = 23.8; P < .001) patients. White patients were treated at hospitals with institutional-level racial and ethnic diversity of 30% or less at higher rates compared with other groups (White: 393 [37%] vs Black: 51 [27%]; χ21 = 25.3; P < .001 vs Hispanic 21 [7%]; χ21 = 197.6; P < .001).

Hospital Course

Infants with CDH from all racial and ethnic categories were admitted to the ICU for a comparable number of days (Table 2). White patients required mechanical ventilation for significantly less time than Black patients (White: mean [SD] 41 [71] days vs Black: 64 [101] days; difference, −22 days; 95% CI for difference −34 to −10; P < .001). White patients also used less inhaled nitric oxide (White: mean [SD] 14 [28] days vs Black: 18 [37] days; difference, −5 days; 95% CI for difference −9 to −.2; P = .04). There were no differences in ventilator duration and pulmonary hypertension medication use in Hispanic patients compared with White patients.

Table 2. Hospital Course of Infants With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, by Race and Ethnicity.

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 1565), mean (SD) | White (n = 1071) (reference), mean (SD) | Black (n = 188), mean (SD) | P value | Hispanic (n = 306), mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time in ICU, d | 65 (250) | 65 (299) | 72 (75) | .77 | 60 (74) | .77 |

| Time on mechanical ventilation, d | 44 (78) | 41 (71) | 64 (101) | <.001 | 39 (84) | .63 |

| Time on sildenafil, d | 18 (55) | 18 (49) | 26 (77) | .05 | 15 (57) | .35 |

| Time on iNO, d | 14 (29) | 14 (28) | 18 (37) | .04 | 12 (30) | .40 |

| ECLS, No. (%) | 457 (29) | 316 (30) | 69 (37) | .05 | 72 (24) | .04 |

| ECLS before surgery, No. (%)a | 195 (43) | 137 (43) | 26 (38) | .65 | 32 (44) | .79 |

| Repair while receiving ECLS, No. (%)b | 126 (65) | 86 (63) | 18 (69) | .34 | 22 (69) | .77 |

| Repair after ECLS, No. (%)b | 69 (35) | 51 (37) | 8 (31) | .97 | 10 (31) | .24 |

| ECLS cannulation day of life, d | 3 (13) | 3 (13) | 4 (14) | .40 | 4 (12) | .53 |

| ECLS decannulation day of life, d | 19 (17) | 19 (18) | 23 (18) | .10 | 17 (13) | .35 |

| Age at repair, d | 8 (20) | 7 (16) | 13 (38) | <.001 | 7 (17) | .88 |

Abbreviations: iNO, inhaled nitric oxide; ECLS, extracorporeal life support; ICU, intensive care unit.

Denominator reflective of No. patients receiving ECLS.

Denominator reflective of No. patients receiving ECLS before surgery.

White infants were supported on ECLS at significantly lower rates than Black infants (White: 316 patients [30%] vs Black: 69 patients [37%]; χ21 = 3.9; P = .05) but at significantly higher rates compared with Hispanic infants (Hispanic: 72 patients [24%]; χ21 = 4.2; P = .04). Of those placed on ECLS, there were no differences between the racial and ethnic groups in terms of ECLS duration or the timing of their repair in relation to their ECLS status, with most patients being repaired on ECLS (126 patients [64%]).

Mortality and Morbidity

Table 3 shows mortality and morbidity data. The 60-day mortality rates (White: 99 patients [9%] vs Black: 29 patients [15%]; χ21 = 6.7; P = .01) and in-hospital mortality rates (White: 133 patients [12%] vs Black: 40 patients [21%]; χ21 = 10.6; P = .001) were significantly lower in White patients compared with Black patients. There were no mortality differences between White and Hispanic patients. Among CDH survivors, White patients were hospitalized for a significantly shorter time than Black patients (median [IQR], White: 46 [26-83] days vs Black: 55 [33-116] days; z score, −3.6; P < .001). In addition, White patients were more likely to be discharged home (White: 779 patients [73%] vs Black: 117 patients [62%]; χ21 = 8.6; P = .003) and were less likely to require a tracheostomy (White: 59 patients [6%] vs Black: 19 patients [10%]; χ21 = 5.8; P = .02). There were no significant differences in discharge outcomes when comparing White patients to Hispanic patients.

Table 3. Hospital Mortality and Morbidity Outcomes in Patients With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, by Race and Ethnicity.

| Outcome | Overall (N = 1565), No. (%) | White (n = 1071), No. (%) (reference) | Black (n = 188), No. (%) | P value | Hispanic (n = 306), No. (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60-d mortality | 145 (9) | 99 (9) | 29 (15) | .01 | 30 (10) | .77 |

| In-hospital mortality | 211 (14) | 133 (12) | 40 (21) | .001 | 38 (12) | >.99 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), days | 47 (27-87) | 46 (26-83) | 55 (33-116) | <.001 | 47 (23-89) | .20 |

| Discharge to home | 1133 (72) | 779 (73) | 117 (62) | .003 | 237 (78) | .10 |

| Tracheostomy at discharge | 96 (6) | 59 (6) | 19 (10) | .02 | 18 (6) | .80 |

| Gastrostomy at discharge | 384 (25) | 255 (24) | 56 (30) | .08 | 73 (24) | .99 |

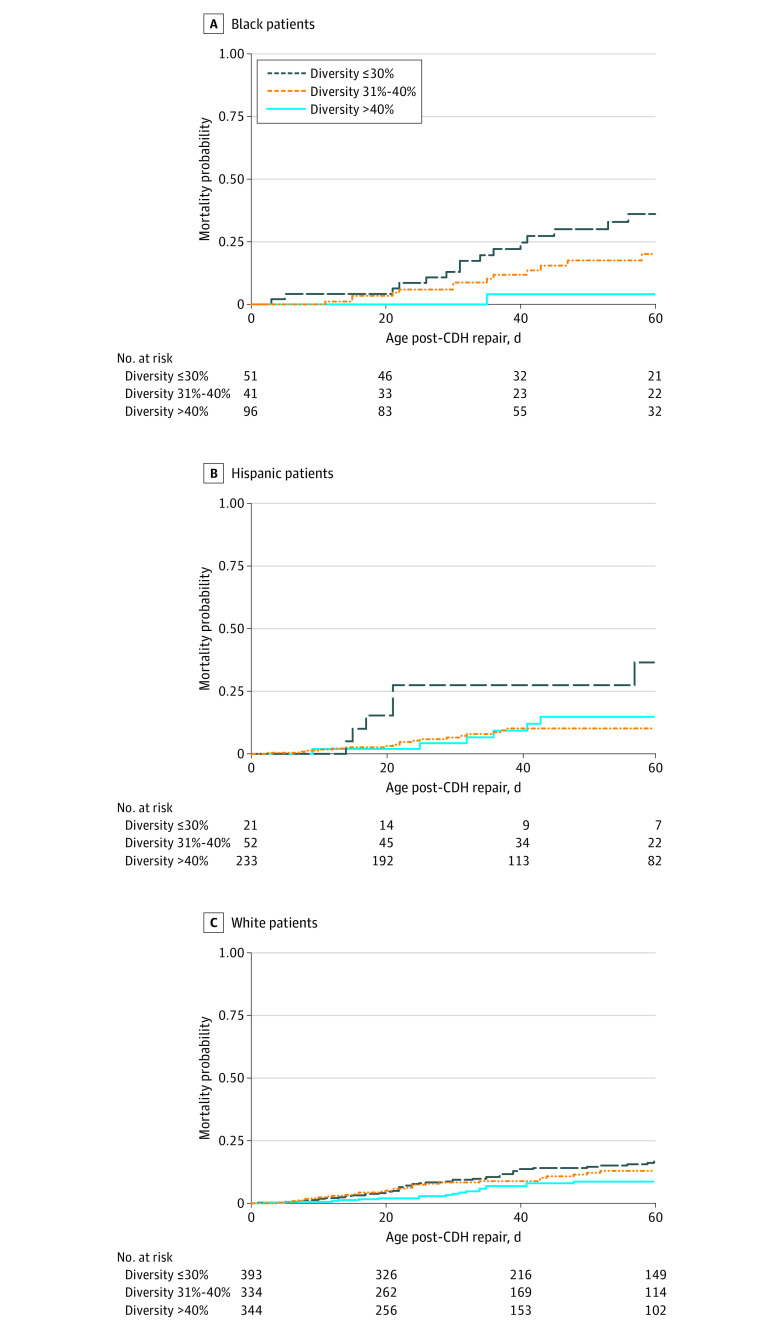

Kaplan-Meier mortality curves revealed significant differences in 60-day mortality in Black, Hispanic, and White patients according to the racial and ethnic diversity of the infants with CDH treated (Figure). In Black and White patients, racial and ethnic diversity of 31% to 40% was associated with lower mortality. In Hispanic patients, racial and ethnic diversity greater than 40% led to improved mortality rates. In all 3 cohorts, racial and ethnic diversity of 30% or less was associated with higher mortality.

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Survival Estimates of 60-Day Mortality in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) Stratified by Racial and Ethnic Diversity.

Cox proportional regression analyses were performed to assess 60-day mortality in Black, Hispanic, and White infants with CDH (Table 4). In all racial and ethnic subgroups, ECLS use was significantly associated with mortality (Black: hazard ratio [HR] 4.66; 95% CI, 1.45-15.01; P = .01; Hispanic: HR, 14.82; 95% CI, 4.63-47.42; P < .001; White: HR, 7.50; 95% CI, 4.77-11.81; P < .001). In Black infants, racial and ethnic diversity of 31% to 40% was associated with lower mortality (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04-0.78; P = .02). In Hispanic patients, racial and ethnic diversity greater than 40% was associated with lower mortality (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.15-0.89; P = .03). There was no significant association between racial and ethnic diversity and mortality in White patients.

Table 4. Cox Regression Analysis Assessing 60-Day Mortality Factors Associated With Risk in Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia.

| Factor | Black | Hispanic | White | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Disease severity | ||||||

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 1.51 (0.62-3.69) | .37 | 1.57 (0.81-3.05) | .18 | 0.76 (0.56-1.04) | .08 |

| Days on nitric oxide | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | .03 | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | .30 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .17 |

| ECLS | 4.66 (1.45-15.01) | .01 | 14.82 (4.63-47.42) | <.001 | 7.50 (4.77-11.81) | <.001 |

| Institutional | ||||||

| High volume hospitala | 0.91 (0.46-1.83) | .80 | 0.76 (0.41-1.39) | .37 | 0.74 (0.29-1.86) | .52 |

| Racial and ethnic diversityb | ||||||

| <30% | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 31%-40% | 0.17 (0.04-0.78) | .02 | 0.40 (0.14-1.12) | .08 | 0.68 (0.30-1.58) | .38 |

| >40% | 0.64 (0.29-1.41) | .27 | 0.37 (0.15-0.89) | .03 | 1.15 (0.51-2.63) | .73 |

Abbreviations: ECLS, extracorporeal life support; NA, not applicable.

High volume hospitals indicates those with 10 or more cases per year.

Racial and ethnic diversity is the percentage of Black/Hispanic patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia treated.

Discussion

Using a large, national database of 1565 infants across 49 major children’s hospitals, this cohort study sought to evaluate contemporary racial and ethnic mortality differences in CDH. Although we have learned a tremendous amount about disease risk stratification, racial and ethnic outcome disparities have been a relatively unexplored area of CDH clinical research.25 Our results revealed that Black infants had significantly higher 60-day and in-hospital mortality rates compared with White infants. Hispanic patients, however, had comparable mortality rates with White patients.

Our data also found that Black patients had evidence of more severe disease according to birth weight, gestational age, and other early postnatal markers of disease. As has been shown in the general population, Black neonates are born at earlier gestational ages compared with White neonates, with a resultant decrease in birthweight. These data are comparable with numerous studies demonstrating discrepancies at birth in Black neonates.17,18 There is a growing body of evidence that low SES, early maternal age, lack of prenatal care, and potential racially related stressors are associated with the observed shortened gestation and low birthweight.18 In our study, Black patients also required more intensive care treatment, receiving ECLS at a higher frequency and requiring longer courses of pulmonary antihypertensives. Evidence of increased disease severity in Black patients has been suggested in other pediatric conditions as well, specifically in congenital cardiac disease and bronchopulmonary dysplasia.46,47,48

The Kaplan-Meier mortality curves in our study confirmed our hypothesis, demonstrating that Black and Hispanic infants had lower mortality rates when treated in hospitals that manage a larger percentage of Black and Hispanic patients. This is starkly contrasted to a diversity of 30% or less, which was associated with significantly higher unadjusted mortality in Black, Hispanic, and White patients. Even after controlling for markers of disease severity, and institutional descriptors such as hospital volume, hospitals with racial and ethnic diversity of 31% to 40% and more than 40% were correlated with lower mortality in Black and Hispanic patients, respectively.

Although our data showed that low levels of patient diversity were negatively associated with outcomes in Black and Hispanic patients, the reasons for this observation remain unknown and are beyond the scope of our study. Nevertheless, we have no evidence there is biologic plausibility for the disparities seen and rather speculate that both unmeasured social determinants of health (SDoH) and clinician bias might be key driving forces for these outcome disparities.49 SDoH consist of nonmedical factors that affect an individuals’ health outcomes.50 Broadly, the areas involved include education, health care, neighborhood and environment, social and community factors, and economic stability.50 Race and ethnicity are inherently intertwined in SDoH and play a key role in the disparities seen in numerous neonatal and pediatric diseases.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,51,52 Black race, for example, has been shown to be associated with lower household income and increased socioeconomic deprivation.53 This may affect a mother’s ability to access adequate prenatal care due to financial strain and transportation challenges, ultimately predisposing her to preterm labor and infant mortality and morbidity.54,55 In those cases with congenital disease, these challenges are magnified as the continued care of the infant requires increased time and resources. Overall, individual and community level socioeconomic and environmental factors add additional levels of acute and chronic stress and increase the complexity in obtaining adequate levels of care compared with those patients living in a more stable environment.56,57 These patients are further marginalized at institutions where staff are not accustomed to providing family and patient centered care.19 Systemic racism, implicit bias, and societal constructs increase the likelihood that clinicians mislabel patients as unreliable or difficult, rather than addressing the source of their presumed inattention to care.19 These factors have been recognized on a national level, as racism and social injustice were named the Determinants of Child Health as the American Pediatric Society Issue of the Year in 2020.58 It is clear that social determinants of health predispose Black patients to poor outcomes in CDH and discrimination might further propagate these negative results.

Just as low patient diversity worsened outcomes in racial and ethnic minority populations, higher levels of racial and ethnic diversity were associated with lower mortality in Black and Hispanic patients. This outcome could be due, in part, to increased levels of clinician racial and ethnic diversity at the treating institution. Although our study does not have data on the racial and ethnic diversity of the clinicians at each institution, it is reasonable to hypothesize that clinician racial and ethnic diversity was increased in those hospitals with a more diverse patient population.59,60 Both the adult and pediatric literature have shown that racial and ethnic concordance between Black and Hispanic patients and clinicians significantly improves survival.61,62,63 This correlation is largely attributed to enhanced trust in the care team and improved communication, leading to better health care utilization.61,62,63,64 Furthermore, prior literature has noted that Black clinicians may be more aware of the socioeconomic intricacies and challenges faced by Black patients and are thus better equipped to treat the complexities of care that arise.62 However, it is important to recognize that as levels of racial and ethnic diversity are further increased, there is a potential for decreased resources and increased workforce shortages in hospitals that treat primarily racial and ethnic minority patients.17 Further studies focusing on hospitals that treat primarily racial and ethnic minority patients should be pursued to evaluate the effects of race and ethnicity in conjunction with resource allocation.

Limitations

Although our data provide results on a large number of patients with CDH, there are several limitations that deserve mention. First, as with any administrative database study, there were fundamental data collection challenges, such as miscoding and missing data. Additionally, data inconsistencies may be evident such as those seen in household income, whereby heterogeneity may be masked within each zip code. Furthermore, there may be confounding variables that are relevant to assess CDH disease severity but were unavailable in PHIS, including prenatal lung size, liver herniation, intraoperative anomaly size, and additional markers of SES including education level, occupation, deprivation status, distance to specialized care, and public assistance. A second major limitation of our study is that race and ethnicity were regarded as categorical variables which can lead to inherent inaccuracies within the data. Infants from multiracial backgrounds and the obvious heterogeneity within Hispanic communities according to country of origin, language, and immigration status are notable examples. Third, our study included only those patients with CDH that underwent surgical repair. We did not analyze the small fraction (approximately 10%-15%) of patients with CDH where care was withdrawn shortly after birth or who were too ill to tolerate surgery.65 This experimental design may explain our slightly lower overall mortality rates. Whether disparities exist among the cohort that did not undergo repair should be a focus of further study. Additionally, our study was unable to analyze the mortality rates and subsequent effects of institutional-level racial and ethnic diversity in additional racial and ethnic minority patients, namely American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Due to small numbers, the results of these analyses were less likely to provide meaningful results. It would therefore be important for our findings to be validated using a larger consortium of patients with CDH .

Conclusions

This large administrative database study of infants with CDH found that Black patients had significantly higher mortality rates compared with their White counterparts. Our data revealed that hospitals in more racially and ethnically diverse communities were associated with lower 60-day mortality among Black and Hispanic infants, without altering mortality among White infants. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to assess CDH mortality according to diversity of the patient population treated. We believe these data highlight ongoing disparities seen in the care of children with CDH and represent a call to action to better understand how each of us might improve CDH care to infants from all racial and ethnic groups.

eTable. International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth and Tenth Revision, Diagnosis and Procedure Codes Used to Acquire Patient Level Data in PHIS Database

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Amdani S, Bhimani SA, Boyle G, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities persist in the current era of pediatric heart transplantation. J Card Fail. 2021;27(9):957-964. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Klein M, et al. Racial disparities in pediatric access to kidney transplantation: does socioeconomic status play a role? Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):369-378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03888.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jette CG, Rosenbloom JM, Wang E, De Souza E, Anderson TA. Association between race and ethnicity with intraoperative analgesic administration and initial recovery room pain scores in pediatric patients: a single-center study of 21,229 surgeries. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):547-558. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00811-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaPlant MB, Hess DJ. A review of racial/ethnic disparities in pediatric trauma care, treatment, and outcomes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(3):540-550. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feliz A, Holub JL, Azarakhsh N, Bachier-Rodriguez M, Savoie KB. Health disparities in infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Am J Surg. 2017;214(2):329-335. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pecha PP, Chew M, Andrews AL. Racial and ethnic disparities in utilization of tonsillectomy among Medicaid-insured children. J Pediatr. 2021;233:191-197.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willer BL, Mpody C, Tobias JD, Nafiu OO. Racial disparities in failure to rescue following unplanned reoperation in pediatric surgery. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(3):679-685. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Mpody C, Sivak E, Tobias JD, Nafiu OO. Racial disparities in postoperative morbidity and mortality among high-risk pediatric surgical patients. J Clin Anesth. 2022;81:110905. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2022.110905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willer BL, Mpody C, Tobias JD, Nafiu OO. Association of race and family socioeconomic status with pediatric postoperative mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222989. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson JK, Chen Y, Nguyen DV, Setty SP. Current trends in racial, ethnic, and healthcare disparities associated with pediatric cardiac surgery outcomes. Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;12(4):520-532. doi: 10.1111/chd.12475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thammana RV, Knechtle SJ, Romero R, Heffron TG, Daniels CT, Patzer RE. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in pediatric and young adult liver transplant outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(1):100-115. doi: 10.1002/lt.23769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laster M, Soohoo M, Hall C, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in mortality and kidney transplant outcomes among pediatric dialysis patients. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(4):685-695. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3530-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20170918. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haskell SE, Girotra S, Zhou Y, et al. Racial disparities in survival outcomes following pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2021;159:117-125. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flores G; Committee On Pediatric Research . Technical report–racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e979-e1020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabbitts JA, Groenewald CB. Epidemiology of pediatric surgery in the United States. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(10):1083-1090. doi: 10.1111/pan.13993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glazer KB, Zeitlin J, Egorova NN, et al. Hospital quality of care and racial and ethnic disparities in unexpected newborn complications. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2020024091. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-024091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberg CN, Rinaldi M. Pediatric health disparities. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2006;36(7):251-268. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2006.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravi D, Iacob A, Profit J. Unequal care: racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care delivery. Semin Perinatol. 2021;45(4):151411. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Racial segregation and inequality in the neonatal intensive care unit for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(5):455-461. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sigurdson K, Mitchell B, Liu J, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20183114. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barfield WD, Cox S, Henderson ZT. Disparities in neonatal intensive care: context matters. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20191688. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron DB, Graham DA, Milliren CE, et al. Quantifying the burden of interhospital cost variation in pediatric surgery: implications for the prioritization of comparative effectiveness research. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):e163926. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosiński P, Wielgoś M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: pathogenesis, prenatal diagnosis and management - literature review. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(1):24-30. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2017.0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zani A, Chung WK, Deprest J, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8(1):37. doi: 10.1038/s41572-022-00362-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harting MT. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia-associated pulmonary hypertension. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017;26(3):147-153. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deprest JA, Nicolaides KH, Benachi A, et al. ; TOTAL Trial for Severe Hypoplasia Investigators . Randomized trial of fetal surgery for severe left diaphragmatic hernia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(2):107-118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sferra SR, Nies MK, Miller JL, et al. Morbidity in children after fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Results from a multidisciplinary clinic. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;58(1):14-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jancelewicz T, Langham MR Jr, Brindle ME, et al. Survival benefit associated with the use of extracorporeal life support for neonates with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Surg. 2022;275(1):e256-e263. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sferra SR, Miller JL, Cortes M S, et al. Postnatal care setting and survival after fetoscopic tracheal occlusion for severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;57(12):819-825. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sola JE, Bronson SN, Cheung MC, Ordonez B, Neville HL, Koniaris LG. Survival disparities in newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a national perspective. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(6):1336-1342. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinton CF, Siffel C, Correa A, Shapira SK. Survival Disparities Associated with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. Birth Defects Res. 2017;109(11):816-823. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stone ML, Lapar DJ, Kane BJ, Rasmussen SK, McGahren ED, Rodgers BM. The effect of race and gender on pediatric surgical outcomes within the United States. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(8):1650-1656. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasquali SK, Jacobs JP, Shook GJ, et al. Linking clinical registry data with administrative data using indirect identifiers: implementation and validation in the congenital heart surgery population. Am Heart J. 2010;160(6):1099-1104. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of social determinants with children’s hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slain KN, Barda A, Pronovost PJ, Thornton JD. Social factors predictive of intensive care utilization in technology-dependent children, a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:721353. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.721353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grushka JR, Laberge JM, Puligandla P, Skarsgard ED; Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network . Effect of hospital case volume on outcome in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the experience of the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(5):873-876. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kane JM, Harbert J, Hohmann S, et al. Case volume and outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia surgery in academic medical centers. Am J Perinatol. 2015;32(9):845-852. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1543980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marin JR, Rodean J, Hall M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in emergency department diagnostic imaging at US children’s hospitals, 2016-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033710. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United States Census Bureau . 2020 Census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. 2021. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html#:~:text=The%20largest%20Multiracial%20combinations%20in,Other%20Race%20(1%20million)

- 44.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. 2nd ed. Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufman JS, Cooper RS. Commentary: considerations for use of racial/ethnic classification in etiologic research. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):291-298. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oster ME, Strickland MJ, Mahle WT. Racial and ethnic disparities in post-operative mortality following congenital heart surgery. J Pediatr. 2011;159(2):222-226. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.01.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tjoeng YL, Jenkins K, Deen JF, Chan T. Association between race/ethnicity, illness severity, and mortality in children undergoing cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160(6):1570-1579.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis TR, Kielt MJ, Walker VP, et al. ; Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Collaborative . Association of racial disparities with in-hospital outcomes in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(9):852-859. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895-904. doi: 10.1111/acem.13214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Social determinants of health. January 19, 2023. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/sdoh/index.html

- 51.Lester LA, Rich SS, Blumenthal MN, et al. Ethnic differences in asthma and associated phenotypes: collaborative study on the genetics of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 108(3):357-362. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith LA, Hatcher-Ross JL, Wertheimer R, Kahn RS. Rethinking race/ethnicity, income, and childhood asthma: racial/ethnic disparities concentrated among the very poor. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(2):109-116. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semega J, Kollar M, Creamer J. Mohanty A. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018. United States Census Bureau; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tran R, Forman R, Mossialos E, Nasir K, Kulkarni A. Social determinants of disparities in mortality outcomes in congenital heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:829902. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.829902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dagher RK, Linares DE. A critical review on the complex interplay between social determinants of health and maternal and infant mortality. Children (Basel). 2022;9(3):394. doi: 10.3390/children9030394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorch SA, Enlow E. The role of social determinants in explaining racial/ethnic disparities in perinatal outcomes. Pediatr Res. 2016;79(1-2):141-147. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Federico MJ, McFarlane AE II, Szefler SJ, Abrams EM. The impact of social determinants of health on children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1808-1814. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abman SH, Bogue CW, Baker S, et al. ; American Pediatric Society (APS) . Racism and social injustice as determinants of child health: the American Pediatric Society issue of the year. Pediatr Res. 2020;88(5):691-693. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-01126-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedman AL; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Workforce . Enhancing the diversity of the pediatrician workforce. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):833-837. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Committee on pediatric workforce . Enhancing pediatric workforce diversity and providing culturally effective pediatric care: implications for practice, education, and policy making. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e1105-e1116. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hollingsworth JM, Yu X, Yan PL, et al. Provider Care team segregation and operative mortality following coronary artery bypass grafting. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(5):e007778. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 62.Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21194-21200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913405117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dreachslin JL, Hobby F. Racial and ethnic disparities: why diversity leadership matters. J Healthc Manag. 2008;53(1):8-13. doi: 10.1097/00115514-200801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fields A, Abraham M, Gaughan J, Haines C, Hoehn KS. Language matters: race, trust, and outcomes in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(4):222-226. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gupta VS, Harting MT, Lally PA, et al. ; Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group . Mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter registry study of over 5000 patients over 25 years. Ann Surg. 2021;277(3):520-527. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth and Tenth Revision, Diagnosis and Procedure Codes Used to Acquire Patient Level Data in PHIS Database

Data Sharing Statement