Abstract

Aims:

This study characterizes Gulf War Illness (GWI) among U.S. veterans who participated in the Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository (GWECB).

Main methods:

Mailed questionnaires were collected between 2014 and 2016. Self-reported GWI symptoms, symptom domain criteria, exclusionary diagnoses, and case status were examined based on the originally published Kansas and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definitions in the GWECB cohort (n = 849 deployed to Gulf and n = 267 non-deployed). Associations among GWI and deployment status, demographic, and military service characteristics were examined using logistic regression.

Key findings:

Among deployed veterans in our sample, 39.9% met the Kansas criteria and 84.2% met the CDC criteria for GWI. Relative to non-deployed veterans, deployed veterans had a higher odds of meeting four GWI case status-related measures including the Kansas symptom criteria (aOR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.50, 2.80), Kansas GWI case status (aOR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.93), the CDC GWI case status (aOR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.07, 2.29) and the CDC severe criteria (aOR = 2.67, 95% CI = 1.79, 3.99). Forty percent met the Kansas exclusionary criteria, with no difference by deployment status. Some symptoms were nearly universally endorsed.

Significance:

This analysis provides evidence of a sustained, multisymptom illness in veterans who deployed to the Persian Gulf War compared to non-deployed Gulf War era veterans nearly 25 years later. Differences in symptoms attributed to GWI by deployment status have diminished since initial reports, suggesting the need to update GWI definitions to account for aging-related conditions and symptoms. This study provides a foundation for future efforts to establish a single GWI case definition and analyses that employ the biorepository.

Keywords: Post-deployment health, Chronic multisymptom illness, Long-term follow-up, Veteran

1. Introduction

Gulf War Illness (GWI), a chronic multiple symptom illness (CMI), has become the defining condition for troops deployed to the Persian Gulf region in support of Operation Desert Shield, Operation Desert Storm, and related operations between August 1990 and July 1991 [1]. An estimated 25%–32% of GW veterans [2–6] are afflicted with GWI and suffer from co-occurring chronic symptoms, such as fatigue, headaches, pain, gastrointestinal problems, and difficulty concentrating, that cannot be explained by other health conditions [7]. To date, the cause(s) of GWI and effective treatments remain under investigation [8].

To better understand Gulf War era veterans’ health, well-being, and health care needs, the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Cooperative Studies Program initiated the Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository (GWECB) [9]. The GWECB cohort consists of veterans who consented to provide survey data, medical records, and blood specimens for use in approved studies. This cohort has the potential to contribute to the discovery of novel findings regarding the etiology, biological consequences, and development of treatments for GWI as it includes individuals who obtained health care within and outside the VA healthcare system, oversamples of women and racial and ethnic minorities, a national geographic representation, and biological samples.

A first step in researching these essential aspects of GWI is distinguishing cases from noncases of GWI. While many approaches have been used to characterize GWI in research studies and clinical settings, no uniformly accepted case definition exists. In 2014, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [1] recommended use of two definitions: 1) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria (originally referred to as CMI) [5] and 2) the Kansas GWI criteria [4], and for the VA to develop a single, robust GWI case definition using a rigorous process. Both recommended existing case definitions were established within the first few years following the war and define GWI inclusionary criteria based on veterans’ persistent or reoccurring symptoms across multiple domains.

Applying these definitions to the GWECB cohort, this study addresses three aims. First, we report the prevalence of GWI case status based on the CDC and Kansas definitions, separately by deployment. Second, we examine whether the prevalence of exclusionary conditions and case-defining symptoms within the GWECB cohort differs by deployment status—mirroring analyses conducted on the original Kansas cohort [4]. Critically, we examine the extent to which deployment continues to be associated with these symptoms 25 years after the war. This is important because 1) the prevalence of symptoms and exclusionary conditions would generally be expected to increase with age [10] and 2) the symptoms comprising both GWI case definitions were selected due to excess rates among the deployed. Third, we examine whether GWI case status related measures differ by sociodemographic and military characteristics among Gulf War deployed veterans. This is the first study to report rates of GWI among veterans in the GWECB cohort using existing case definitions. This research provides a foundation for developing a refined GWI case definition as called for by the IOM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data

Details regarding the recruitment process and survey instrument for the Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository (GWECB) pilot study population were previously reported [9] and are summarized here. Recruitment and data collection for the GWECB pilot occurred between 2014 and 2016 and included deployed and nondeployed veterans.

Eligibility criteria for the GWECB included veterans who served in the US Uniformed Services between August 1990 and July 1991, regardless of deployment status, combat status, health status, and whether or not they had enrolled in and/or used the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for their health care. A stratified recruitment panel was drawn from a population of nearly 5 million veterans provided by the Department of Defense Manpower Data Center. The stratification factors were 1) deployment to the theater of operations (i.e., area where combat-related activities occurred) in 1990–1991; 2) active duty; 3) Army; 4) officer; 5) non-white race (American Indian, Asian, Black, other and unknown; and 6) non-male sex (female and unknown). A pilot recruitment sample of 10,042 veterans was selected to represent the distribution of Gulf War era (GWE) veterans in each of four U.S. Census regions. Cities within these regions served as recruitment hubs and were selected for their access to local study staff and phlebotomists. Those in the stratified recruitment samples and those who self-nominated were mailed recruitment materials. Before veterans could complete study documents, phone contact with the GWECB Enrollment Coordinating Center was required. Veterans signed and mailed paper copies of informed consent documents and the survey instrument. In addition to the stratified recruitment approach, veterans were allowed to self-nominate. Ultimately, 1344 individuals enrolled in the GWECB. This included 12.6% of veterans who were selected for the pilot (n = 1268) and 76 veterans who self-nominated. One participant subsequently withdrew consent to participate.

Self-reported measures regarding demographic and military service characteristics, symptoms and diagnoses were collected through a mail survey, the Gulf War Era Veteran Survey [11]. The study protocol and study materials were approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board and acknowledged by the Durham VA Medical Center Research and Development Committee (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01803854).

2.2. Participants

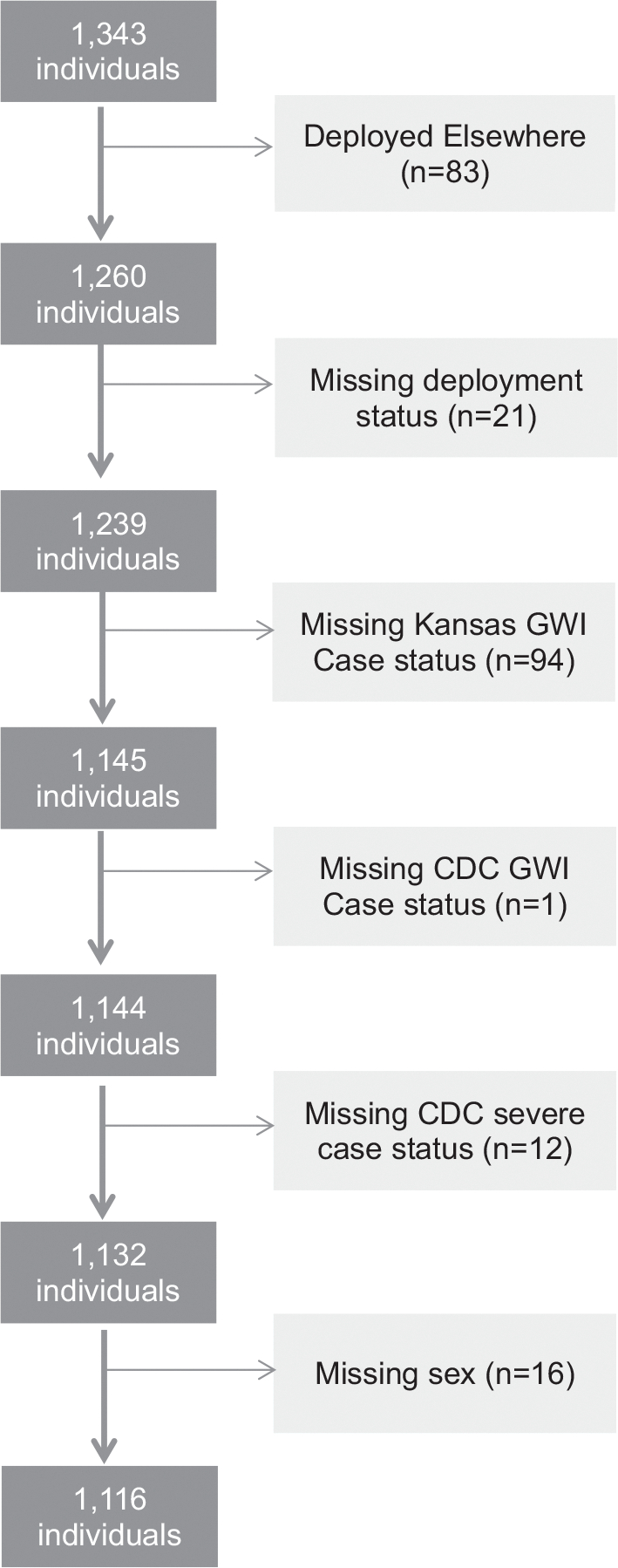

The sample for the present study was selected from the 1343 individuals who participated in the GWECB. Individuals who were deployed in support of the Gulf War but not to the theater of operations (n = 83), who were deployed missing deployment information (n = 21), were missing information that prevented classification into GWI categories (Kansas, n = 94; CDC, n = 1, and CDC severe, n = 12) and were missing sex (n = 16) were excluded from the analysis (Fig. A1). The final analytic sample included 1116 veterans including 849 deployed to the theater of operations and 267 who were not deployed. This analysis included 89% of individuals who deployed or did not deploy to the Gulf in support of the war.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Gulf War illness case definitions

To identify individuals who met the criteria for GWI according to the Kansas and CDC definitions, the originally published definitions were followed as closely as possible. Complete technical documentation and code are available and details are summarized here [12]. Both definitions of GWI were based on self-reported symptoms. In the GWECB, veterans were asked to report on a series of symptoms “Over the past 6 months, have you a had persistent or recurring problem with…?” If respondents answered yes, then they were asked “How would you rate this problem?” with response options of “mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”. These responses were compiled to determine whether or not the veteran met the criteria for the Kansas and CDC definitions as described below.

2.3.1.1. Kansas GWI definition.

The Kansas GWI definition was based on a veteran reporting multiple mild or at least one moderate-to-severe symptoms in at least three of six domains: fatigue and sleep problems (“Fatigue”, “Feeling unwell after exercise”, “Difficulty getting to or staying asleep”, “Not feeling rested after sleep”); pain (“Pain in joints”, “Pain in muscles”, “Body pain where you hurt all over”); neurologic, cognitive, and mood symptoms (“Difficulty remembering recent information”, “Feeling irritable or having angry outbursts”, “Numbness or tingling in extremities”, “Headaches”, “Eyes very sensitive to light”, “Trouble finding words when speaking”, “Feeling down or depressed”, “Difficulty concentrating”, “Night sweats”, “Feeling dizzy, lightheaded or faint”, “Low tolerance for heat or cold”, “Symptoms in response to smells or chemicals”, “Blurred or double vision”, “Tremors or shaking”); gastrointestinal (“Diarrhea”, “Nausea or upset stomach”, “Abdominal pain or cramping”); respiratory (“Difficulty breathing”, “Frequent coughing without a cold”, “Wheezing in chest”); and skin (“Skin rash” and “Other skin problems”). For each of the six symptom domains, we constructed a binary variable to determine whether or not the veteran met the moderate or multiple symptom domain criteria by having endorsed at least two symptoms within the domain and/or having rated at least one symptom within the domain as moderate or severe. These moderate or multiple symptom domain indicators were then combined to form the Kansas symptom criteria, which was met by meeting the moderate or multiple symptom domain criteria for at least three different symptom domains.

The Kansas GWI definition also uses exclusionary criteria to identify veterans whose array of symptoms may be attributed to other chronic health conditions or who had diagnosed psychiatric conditions that could interfere with the veteran’s ability to report symptoms. The exclusionary conditions as originally reported were identified on the basis that the prevalence of each condition did not differ by deployment status, suggesting that deployment was not associated with an excess burden of a given health condition [4]. Individuals with such conditions were then ineligible to be considered a GWI case. Veterans were asked a series of questions regarding their history of diagnosed conditions “Have you ever been told by a doctor or healthcare provider that you have…?” (yes/no). To harmonize the categorization of exclusionary criteria with the original Kansas definition, authors of this study (including two physicians who treat veterans) developed a set of consensus exclusionary conditions. In this analysis, exclusionary criteria included a diagnosis of cancer (brain, breast, colon, lung, prostate, other), diabetes, heart disease (heart attack, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure), stroke (stroke and transient ischemic attack), infection (HIV, tuberculous, hepatitis C), liver disease, lupus, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury (TBI), schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Finally, to characterize whether the veteran met the Kansas GWI definitions, two binary flags were constructed to indicate if the veteran met 1) the symptom criteria and 2) the exclusionary criteria. The first, Kansas GWI symptom criteria, indicated if the veteran met the moderate or multiple symptom domain criteria in at least three of the six domains. The second, Kansas GWI exclusionary criteria, indicated if the veteran endorsed at least one of the Kansas exclusionary conditions. Kansas GWI case status can be determined using solely these two flags: Kansas GWI case status was considered yes if the veteran met the symptom criteria and did not meet the exclusionary criteria. Consistent with the original definition, veterans who did not meet the symptom criteria or met the exclusionary criteria, were considered to have not met the Kansas GWI case definition [4]. To address missing symptom or diagnosis information, we followed the method set forth by Dursa et al. [13] whereby if the missing information could have changed the status of a veteran from no to yes, then the veteran was considered to be missing the GWI symptom criteria and/or case status.

Differences exist between the original Kansas definition [4] and that used here. First, the original survey for the Kansas definition asked about symptoms which persisted or reoccurred in the year prior to the survey whereas the GWECB survey asked about persistent or reoccurring symptoms over the past 6 months. Second, the original definition only included chronic symptoms that first presented after 1990; the GWECB survey did not specify a date of onset. Third, modifications were needed regarding the exclusionary criteria definition. The originally defined exclusionary criteria included psychiatric conditions that resulted in a hospitalization and war related injuries, but such information was unavailable in the GWECB. Melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, representing about 1% of skin cancers [14], was used as an exclusionary condition in the original definition but not in this analysis. Unlike the original definition, this analysis used TBI as an exclusionary criterion because TBI can present with symptoms similar to GWI [15].

2.3.1.2. CDC GWI definition.

Consistent with the original CDC definition [5], CDC GWI case status was indicated if the veteran endorsed at least one symptom in two of three symptom domains which were composed of the following symptoms: fatigue (“Fatigue”), musculoskeletal (“Pain in joints”, “Pain in muscles”, “Stiffness in joints”), and mood–cognition (“Difficulty remembering recent information”, “Trouble finding words when speaking”, “Feeling moody”, “Feeling down or depressed”, “Difficulty concentrating”, “Difficulty getting to staying asleep”, and “Feeling anxious”). Also aligned with the original definition, a severity subclassification identified individuals as severe GWI if one or more symptom in two or more symptom domains was rated as severe, otherwise, GWI was categorized as mild-to-moderate. If veterans were missing symptom or severity information such that the missing information could have changed CDC GWI case status from no to yes, then CDC case status was set to missing. For each item, similar question wording was used between the original CDC definition and the GWECB modified CDC definition. However, for the mood–cognition domain, the GWECB-CDC definition had two items for “Difficulty remembering recent information” and “difficulty concentrating” while the original CDC definition asked one item regarding “difficulty remembering or concentrating”. We included in our analysis of the CDC definition a single variable summarizing a yes response to one or both of these symptom items. Data used to develop the original CDC definition [5] identified chronic symptoms as those present for ≥6 months vs. “over the past 6 months” in the GWECB.

2.3.2. Deployment

Participants were asked “Did you deploy in support of the 1990–1991 Gulf War?” Responses were “Yes, deployed to the Gulf”, “Yes, deployed elsewhere”, and “no”. In this study, we focus on individuals who deployed to the Gulf (n = 849) vs. those who did not deploy (n = 267).

2.3.3. VHA user

Participants were considered to be users of the Veteran Health Administration if they indicated that they had received any of their health care (e.g., doctor’s visits, hospitalizations, urgent care visits, or counseling) at a VHA facility in the past year.

2.3.4. Military service

Participants self-reported the branch of uniformed services in which they had ever served (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, National Guard, Merchant Marines, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Public Health Service and none). Note, in the United States, the National Guard is part of the reserve component of the Army and Air Force rather than a stand-alone service branch. The NOAA and Public Health Service are nonmilitary uniformed services of the U.S. Government while the Merchant Marines is not a U.S. governmental entity. Participants were also asked to indicate if their service was active duty, reserves, or not applicable (not in military). From this information, we created a set of mutually exclusive binary variables to indicate if a veteran’s service was active duty, reserves, or both active duty and reserves. One participant who marked “Not applicable (not in military)” was omitted from the analysis.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used to estimate the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) for experiencing symptoms, meeting criteria for symptom domains, and four GWI case status-related measures (Kansas GWI symptom criteria, Kansas GWI case status, CDC GWI case status, and CDC GWI severe case status) in Gulf War-deployed vs. nondeployed era veterans. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association of exclusionary conditions, symptoms, and GWI case status with deployment status, while controlling for possible confounders. The covariates were selected to match those used in Steele [4] and included sex, age, income, education, service branch, and unit component.

To understand how the application of the exclusionary conditions might affect the observed association between deployment and symptoms, the effect of deployment on symptoms was examined separately in the total cohort (n = 1116) and two subgroup groups of the GWECB: 1) those who did not meet the exclusionary criteria (n = 655) and 2) those who met the exclusionary criteria (n = 451). The group who did not meet the exclusionary criteria, that is, those who reported no exclusionary conditions, is most comparable to the group presented in the Steele study [4]. As a supplemental analysis, the effect of a possible interaction between exclusionary conditions and deployment on each symptom in the Kansas and CDC definition was tested using logistic regression with additional covariates including the main effects for deployment status, whether or not the veteran met the exclusionary criteria, and sex, age, income, and education.

Finally, multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine how the four GWI case status-related measures varied across key demographic and military service-related characteristics. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 [16].

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

Most of the veterans in the analytic sample had been deployed to the Persian Gulf region in 1990–91 in support of the Gulf War (Table 1). The deployed and non-deployed samples were similar in age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, educational attainment, military characteristics, and use of the VA health care system in the past year. The most common military branch was the Army only (45.5%), followed by the Navy only (16.1%), the Air Force only (11.0%), and the Marine Corps only (12.5%). In addition, 9.8% reported having served in the National Guard. While some participants reported serving in multiple branches during their military careers, 88.4% of the sample reported only serving in one branch (results not shown). Unit component differed by deployment status (χ2 (2)= 9.061, p = 0.0108). A smaller proportion of the deployed than the non-deployed had served only as active duty personnel (58.1% vs. 68.5%, Z = 2.9549, p = 0.003).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by 1990–91 Gulf War deployment status.

| Characteristics | All (N = 1116) | Deployed (n = 849) | Did not deploy (n = 267) | p-value from χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Sex | Male | 76.8 | 78.0 | 73.0 | 0.0953 |

| Female | 23.2 | 22.0 | 27.0 | ||

| Age group | 40–49 years | 38.7 | 40.1 | 34.5 | 0.2538 |

| 50–59 years | 36.9 | 36.3 | 39.0 | ||

| 60 years and over | 24.4 | 23.7 | 26.6 | ||

| Race/Ethnicitya | White, Not Hispanic | 65.1 | 65.3 | 64.4 | 0.4615 |

| Black, Not Hispanic | 17.2 | 16.7 | 18.7 | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.4 | ||

| Other | 6.2 | 6.0 | 6.7 | ||

| Household income per year | Under $30,000 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 12.7 | 0.5835 |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 23.1 | 22.3 | 25.8 | ||

| $60,000 – $99,999 | 29.0 | 29.7 | 27.0 | ||

| $100,000 or more | 29.8 | 30.3 | 28.1 | ||

| Unknown | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.4 | ||

| Highest achieved education levela | High School diploma/GED or less | 9.0 | 9.5 | 7.1 | 0.6373 |

| Some college to Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree | 68.2 | 67.8 | 69.3 | ||

| Master’s degree, Professional degree, or Doctorate degree | 20.7 | 20.4 | 21.7 | ||

| Unit Component | Active duty only | 60.6 | 58.1 | 68.5 | 0.0108 |

| Reserves only | 14.6 | 15.8 | 10.9 | ||

| Both active duty and reserves | 24.4 | 25.6 | 20.6 | ||

| Service Branch | Army only | 45.5 | 45.1 | 46.8 | 0.4698 |

| Navy only | 16.1 | 16.7 | 14.2 | ||

| Air Force only | 11.0 | 10.3 | 13.5 | ||

| Marine corps only | 12.5 | 13.3 | 10.1 | ||

| National Guardb: All | 9.8 | 9.7 | 10.1 | ||

| Other | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.2 | ||

| Used VHA health care or hospital in the last | Yes | 44.3 | 44.9 | 42.3 | 0.3848 |

| year | No | 54.9 | 54.1 | 57.7 | |

| Deployed in support of OEF or OIF | Yes | 21.7 | 22.7 | 18.4 | 0.1952 |

| No | 76.5 | 76.2 | 77.5 | ||

OEF=Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF=Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to unknown responses or missing values in some categories.

National Guard is not a service branch but was asked in conjunction with military branch questions.

3.2. GWI case status-related measures by deployment

Among veterans deployed to the Gulf War in the GWECB cohort, 72.0% met the Kansas symptom criteria, 39.9% met full Kansas GWI case criteria, 84.2% met the CDC GWI case criteria, and 26.9% met the CDC criteria for severe GWI (Table 2). Deployed veterans, relative to non-deployed veterans, had a higher adjusted odds ratio for meeting each of the four GWI case status-related measures—ranging from 1.42 to 2.67. For both deployed and nondeployed veterans, the most prevalent domains among the Kansas GWI moderate or multiple symptom domains were neurologic/cognitive/mood, fatigue/sleep problems, and pain with 65.9% to 86.3% of veterans in each group meeting these criteria. In contrast, gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin symptom domains were less common overall, experienced by only 18.4% to 38.5% of veterans in the deployed and non-deployed groups. Relative to non-deployed veterans, Gulf War deployed veterans had a higher adjusted odds of meeting criteria for each of the six moderate or multiple symptom domains. Importantly, the prevalence of exclusionary conditions did not differ by deployment status (Table A2). Similarly, the overall proportion of veterans who reported one or more exclusionary conditions and therefore met Kansas exclusionary criteria was similar in Gulf War deployed and nondeployed era veterans.

Table 2.

Associations of Gulf War Illness case status-related measures with 1990–91 Gulf War deployment status.

| Measure | Deployed (n = 849) |

Did not deploy (n = 267) |

aOR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Panel A. GWI case status-related measures | ||||

| Kansas symptom criteria | 72.0 | 59.9 | 2.05 | (1.50, 2.80) |

| Kansas GWI case | 39.9 | 32.6 | 1.42 | (1.05, 1.93) |

| CDC GWI case | 84.2 | 80.1 | 1.57 | (1.07, 2.29) |

| CDC GWI severe case | 26.9 | 13.5 | 2.67 | (1.79, 3.99) |

| Panel B. Kansas GWI components | ||||

| Moderate or multiple symptom domain | ||||

| Fatigue/sleep problems (4 symptoms) | 79.4 | 68.9 | 2.14 | (1.53, 3.00) |

| Pain (3 symptoms) | 72.9 | 65.9 | 1.56 | (1.14, 2.14) |

| Neurologic/cognitive/mood (14 symptoms) | 86.3 | 80.1 | 1.80 | (1.22, 2.65) |

| Gastrointestinal (3 symptoms) | 38.5 | 30.3 | 1.57 | (1.15, 2.15) |

| Respiratory (3 symptoms) | 35.5 | 24.0 | 1.93 | (1.39, 2.67) |

| Skin (2 symptoms) | 32.4 | 18.4 | 2.41 | (1.70, 3.44) |

| Exclusionary criteria | 40.3 | 40.8 | 1.05 | (0.78, 1.42) |

| Panel C. CDC GWI components | ||||

| Symptom domain | ||||

| Fatigue (1 symptom) | 69.0 | 55.1 | 2.18 | (1.61, 2.96) |

| Musculoskeletal (3 symptoms) | 87.5 | 86.5 | 1.29 | (0.84, 1.97) |

| Mood-cognition (6 symptoms)1 | 88.7 | 81.6 | 2.09 | (1.39, 3.13) |

| Severe symptom domain | ||||

| Fatigue (1 symptom) | 16.4 | 6.7 | 3.09 | (1.83, 5.22) |

| Musculoskeletal (3 symptoms) | 33.6 | 19.1 | 2.39 | (1.68, 3.41) |

| Mood-cognition (6 symptoms)a | 34.0 | 19.9 | 2.33 | (1.64, 3.32) |

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Note: adjusted for sex, education, income, service branch, unit component, and age.

The six symptoms were based on seven items in the GWECB. Specifically, to reflect the original CDC wording, the highest level of symptom presence/severity from questions regarding “Difficulty remembering recent information” and “Difficulty concentrating” were combined to create one symptom category.

For the CDC GWI symptom domains, deployed veterans had higher adjusted odds than non-deployed for the fatigue (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.61, 2.96) and mood–cognition domains (aOR = 2.09, 95% CI 1.39, 3.13) but not the musculoskeletal domain (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI 0.84, 1.97). However, deployed veterans had a higher adjusted odds for all three of the severe symptom domains fatigue: (aOR = 3.09, 95% CI 1.83, 5.22), musculoskeletal (aOR = 2.39, 95% CI 1.68, 3.41), and mood–cognition (aOR = 2.33, 95% CI 1.64, 3.32).

3.3. Symptoms by deployment

A significantly greater proportion of Gulf War veterans endorsed 27 of the 29 chronic symptoms comprising the Kansas GWI definition, compared to nondeployed veterans (p < 0.05 for all adjusted ORs) (Table 3). Two symptoms, diarrhea and wheezing in chest, did not differ by deployment. For both deployed and non-deployed, the most prevalent symptoms were pain in joints (82.4% deployed and 76.8% non-deployed), not feeling rested after sleep (76.7% deployed and 64.8% non-deployed), and difficulty getting to or staying asleep (75.1% deployed and 62.2% non-deployed). The least common symptoms were wheezing in chest (25.1% deployed and 19.9% non-deployed), tremors or shaking (26.1% deployed and 17.6% non-deployed), and symptoms in response to smells or chemicals (27.6% deployed and 16.5% non-deployed). Point estimates for the adjusted odds ratios across symptoms ranged from 1.33 (diarrhea) to 2.11 (other skin problems). Of the four symptoms included in the CDC but not the Kansas GWI definition, only stiffness in joints did not differ by deployment status. The other three CDC symptoms were reported significantly more frequently by deployed veterans (difficulty remembering recent information/difficulty concentrating aOR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.32, 2.36; feeling moody aOR = 1.65, 95% CI 1.24, 2.21; feeling anxious (aOR = 1.90, 95% CI 1.41, 2.55)) (Table A1).

Table 3.

Kansas GWI Case definition symptoms by Gulf War deployment status.

| Domain | Symptom | Deployed (n = 849) |

Did not deploy (n = 267) |

aOR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| (%) | (%) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Fatigue/sleep problems | Fatigue | 69.0 | 55.1 | 1.95 | (1.45, 2.61) |

| Feeling unwell after exercise | 43.6 | 29.6 | 2.01 | (1.48, 2.73) | |

| Difficulty getting to or staying asleep | 75.1 | 62.2 | 1.91 | (1.41, 2.58) | |

| Not feeling rested after sleep | 76.7 | 64.8 | 1.83 | (1.34, 2.50) | |

| Pain | Pain in joints | 82.4 | 76.8 | 1.48 | (1.05, 2.08) |

| Pain in muscles | 64.7 | 56.2 | 1.49 | (1.12, 1.99) | |

| Body pain where you hurt all over | 43.6 | 37.1 | 1.37 | (1.02, 1.84) | |

| Neurologic/cognitive/mood | Difficulty remembering recent information | 58.0 | 44.6 | 1.76 | (1.33, 2.34) |

| Feeling irritable or having angry outbursts | 57.0 | 43.8 | 1.74 | (1.30, 2.33) | |

| Numbness or tingling in extremities | 63.7 | 50.9 | 1.74 | (1.31, 2.31) | |

| Headaches | 54.2 | 44.6 | 1.51 | (1.13, 2.03) | |

| Eyes very sensitive to light | 45.5 | 35.6 | 1.57 | (1.17, 2.11) | |

| Trouble finding words when speaking | 51.8 | 44.6 | 1.37 | (1.03, 1.82) | |

| Feeling down or depressed | 53.9 | 39.3 | 2.00 | (1.49, 2.70) | |

| Difficulty concentrating | 57.4 | 40.4 | 2.08 | (1.56, 2.78) | |

| Night sweats | 43.2 | 35.2 | 1.44 | (1.07, 1.93) | |

| Feeling dizzy, lightheaded, or faint | 45.2 | 34.1 | 1.62 | (1.21, 2.17) | |

| Low tolerance for heat or cold | 39.2 | 32.6 | 1.46 | (1.08, 1.98) | |

| Symptoms in response to smells or chemicals | 27.6 | 16.5 | 2.02 | (1.41, 2.91) | |

| Blurred or double vision | 38.5 | 28.8 | 1.60 | (1.18, 2.18) | |

| Tremors or shaking | 26.1 | 17.6 | 1.70 | (1.19, 2.43) | |

| Gastro-intestinal | Diarrhea | 33.7 | 27.3 | 1.33 | (0.98, 1.82) |

| Nausea or upset stomach | 36.9 | 29.2 | 1.44 | (1.05, 1.96) | |

| Abdominal pain or cramping | 34.4 | 27.0 | 1.47 | (1.07, 2.01) | |

| Respiratory | Difficulty breathing | 38.2 | 25.5 | 1.90 | (1.39, 2.62) |

| Frequent coughing without a cold | 33.9 | 25.5 | 1.59 | (1.16, 2.18) | |

| Wheezing in chest | 25.1 | 19.9 | 1.41 | (1.00, 1.99) | |

| Skin | Skin rash | 37.5 | 23.2 | 2.05 | (1.49, 2.82) |

| Other skin problems | 35.5 | 21.7 | 2.11 | (1.52, 2.93) | |

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio for Gulf War deployed vs. nondeployed era veterans; CI = confidence interval.

Note: OR adjusted for adjusted for sex, education, income, and age.

3.4. Exclusionary conditions and symptoms in the Kansas definition

The Kansas definition exclusionary criteria were met by 40.3% of the deployed and 40.8% non-deployed samples and, consistent with the 2000 Kansas study, the adjusted odds of meeting at least one exclusionary condition did not differ by deployment status (Table A2). For the GWECB participants in both deployed and nondeployed groups, the most common exclusionary conditions were cancer (9.2%), diabetes (17.0%), and heart disease (8.7%). Overall, the proportion of veterans in the GWECB who did and did not meet the exclusionary conditions differed by (1) age (χ2 (2)= 63.3677, p < 0.001) (2) race/ethnicity (χ2 (4)= 16.3386, p = 0.003) (3) household income (χ2 (4)=32.0947, p < 0.001), educational attainment (χ2 (3)=19.1095, p < 0.001), and use of the VHA in the prior year (χ2 (1)=32.2187, p < 0.001) (Table A3). Of note, the proportion of individuals who met the exclusionary criteria versus those who did not was higher for those (1) aged 60 years and over (36.6% vs. 16.1%, Z = 7.8258 p < 0.001 (2 tails)); (2) Black non-Hispanic (20.0% vs. 15.3%, Z = 2.3661, p = 0.018 (2 tails)); and (3) had used the VHA health care or hospital in the last year (54.6% vs. 37.3.8%, Z = 5.694, p < 0.001 (2 tails)); and lower for those who (1) had an annual household income of $100,000 or more (20.8% vs. 35.8%, Z = −5.360, p < 0.001 (2 tails)) and (2) had a Master’s degree, professional degree or doctorate degree (15.3% vs. 24.4%, Z = − 3.667, p < 0.001 (2 tails)).

3.5. Exclusionary conditions and symptoms in the Kansas definition by deployment status

To investigate how the exclusionary criteria may affect our understanding of the relationship between deployment and symptoms associated with the Kansas GWI definition, the presence of each symptom was evaluated with a logistic regression using models that included the main effects and an interaction term between deployment status (deployed/nondeployed) and whether or not the veteran met the exclusionary criteria (yes/no) (results not shown). For 27 of the 29 symptoms, this interaction term was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) indicating no interaction between deployment status and meeting the exclusionary criteria in relation to the occurrence of GWI symptoms. The two exceptions were for headaches (p = 0.0385) and difficulty remembering recent information (p = 0.0063). For both symptoms, Gulf War deployment (yes vs. no), meeting exclusionary criteria (yes vs. no), and the interaction of these two terms were all positively and significantly associated with symptom occurrence, indicating that veterans who were both deployed and met the exclusionary criteria had a higher odds of endorsing these two symptoms. Overall, however, the association of deployment with the majority of symptoms used in the Kansas definition was similar among veterans who reported exclusionary conditions compared to veterans who reported no exclusionary conditions.

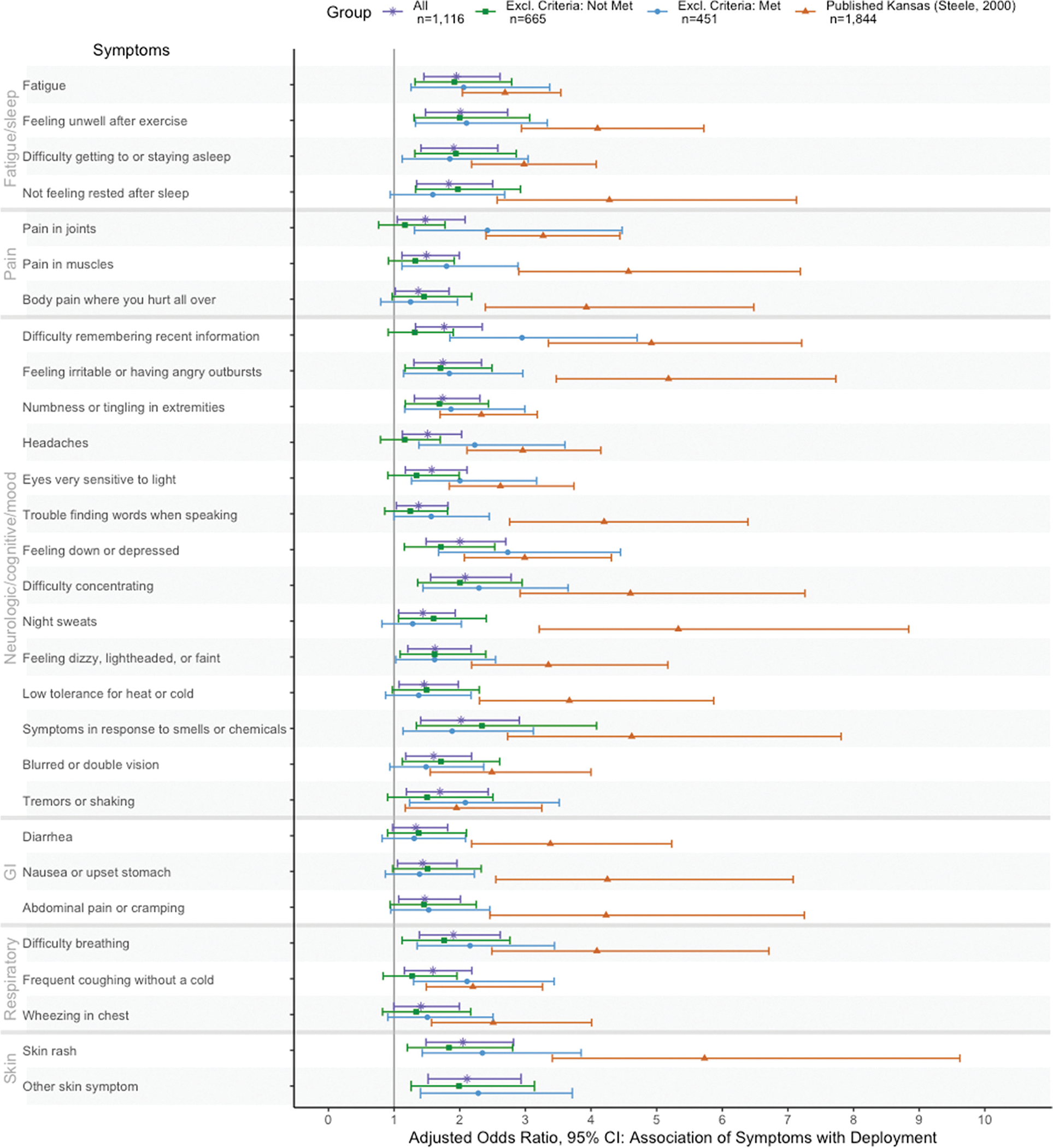

This is further depicted in Fig. 1 which illustrates the associations of symptoms with deployment status within two subgroups of the GWECB cohort: 1) veterans who did not have any exclusionary conditions (n = 655) and 2) veterans with one or more exclusionary conditions (n = 451). As shown, the point estimate for the association of deployment with individual symptoms was similar for nearly all Kansas criteria symptoms, regardless of whether or not the veteran reported an exclusionary condition.

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios for Kansas GWI criteria symptoms in Gulf War deployed vs. non-deployed veterans, in veteran subgroups who do/do not meet exclusionary criteria.

Note: Odds ratio adjusted for sex, age, income, and education.

Excl = exclusionary criteria

CI = Confidence Interval

The Kansas Cohort (Steele 2000) represented in this figure was limited to veterans with no exclusionary conditions.

However, whether or not the association of deployment with a given symptom reached statistical significance differed between those who did and did not meet the exclusionary conditions. Among individuals who did not report any of the exclusionary conditions, deployment was positively associated with symptoms in the following domains: fatigue/sleep problems (4 of 4), neurologic cognitive/mood (8 of 14 symptoms), respiratory (1 of 3) and skin (2 of 2 symptom) but none of the symptoms in the pain or GI domains. For those who met the exclusionary criteria, deployment was positively associated with symptoms in the following domains: fatigue/sleep problems (3 of 4 symptoms), pain (2 of 3 symptoms), neurologic/cognitive/mood (11 of 14 symptoms), respiratory (2 of 3 symptoms), and skin (2 of 2 symptoms), but none of the GI symptoms. Specifically, two symptoms were positively associated with deployment for those who did not meet the exclusionary criteria but not for those who met the exclusionary criteria (Not feeling rested after sleeping and Blurred or double vision). In contrast, seven symptoms were positively associated with deployment among those who met the exclusionary criteria but not among those who did not meet the exclusionary criteria (pain in joints, pain in muscles, difficulty remembering recent information, headaches, eyes very sensitive to light, trouble finding words when speaking, tremors or shaking, and frequent cough without a cold).

Fig. 1 also displays the adjusted odds ratios for symptoms reported by deployed vs. nondeployed veterans in the 2000 Kansas cohort who had no exclusionary conditions [4]. The adjusted odds ratios for deployment were higher in the 2000 Kansas Cohort than the GWECB cohort with no exclusion for 13 symptoms in 4 of 6 domains: pain (3 of 3 symptoms), neurological/mood/cognition (4 of 14 symptoms), GI (3 of 3), and skin (1 of 1 symptom) (Note: the adjusted OR for other skin problems was not reported in the original Kansas paper). Point estimates for all odds ratios comparing symptoms in deployed/nondeployed veterans were substantially lower in the GWECB cohort than the 2000 Kansas cohort.

3.6. Association of sociodemographic and military characteristics with GWI case status-related measures among GWECB veterans deployed to the Gulf War

The proportion of Gulf War deployed veterans who met criteria for the four GWI case status-related measures (Kansas symptom criteria, Kansas GWI, CDC GWI, and CDC severe GWI), varied significantly in relation to a number of key sociodemographic and military characteristics (Table 4). Among the deployed in the GWECB cohort, relative to veterans aged 40–49 years, those aged 50–59 years were less likely to meet the Kansas GWI criteria (aOR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.48, 0.93) while those aged 60 and over were less likely to meet each of the four GWI case status-related measures. Relative to White non-Hispanic veterans, Black veterans were more likely to meet the Kansas symptom criteria (aOR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.07, 2.75) and the CDC GWI severe criteria (aOR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.09, 2.64) while Hispanic veterans were more likely to meet the Kansas symptom criteria (aOR = 3.29, 95% CI = 1.56, 6.94), Kansas GWI (aOR = 2.10, 95% CI = 1.26, 3.50), and CDC GWI severe criteria (aOR = 3.40, 95% CI = 2.02, 5.72).

Table 4.

Association of Gulf War illness case status-related measures with demographic and military characteristics, among veterans deployed to the 1990–91 Gulf War (n = 849).

| Kansas | CDC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Symptom Criteria | GWI Case | GWI Case | Severe GWI Case | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | aOR | 95%CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Female | 1.33 | (0.88, 2.01) | 1.41 | (0.99, 2.00) | 1.83 | (1.06, 3.15) | 1.35 | (0.92, 1.99) |

| Age group | ||||||||

| 40–49 years | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 50–59 years | 0.91 | (0.62, 1.33) | 0.67 | (0.48, 0.93) | 0.87 | (0.54, 1.41) | 0.80 | (0.55, 1.16) |

| Over 60 years | 0.54 | (0.35, 0.81) | 0.23 | (0.15, 0.35) | 0.51 | (0.31, 0.84) | 0.63 | (0.41, 0.97) |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||||||||

| White, not Hispanic | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, not Hispanic | 1.71 | (1.07, 2.75) | 1.11 | (0.74, 1.66) | 1.39 | (0.78, 2.46) | 1.70 | (1.09, 2.64) |

| Hispanic (any race) | 3.29 | (1.56, 6.94) | 2.10 | (1.26, 3.50) | 2.33 | (0.95, 5.70) | 3.40 | (2.02, 5.72) |

| Highest achieved education level | ||||||||

| Master’s degree, Professional degree, or Doctorate degree | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| High School diploma/GED or less | 0.92 | (0.49, 1.75) | 0.59 | (0.31, 1.10) | 1.04 | (0.48, 2.22) | 1.06 | (0.52, 2.15) |

| Some college to Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree | 1.45 | (0.97, 2.16) | 0.92 | (0.62, 1.35) | 1.40 | (0.87, 2.26) | 1.56 | (0.96, 2.54) |

| Household income | ||||||||

| $100,000 or more | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Under $30,000 | 2.41 | (1.28, 4.52) | 1.15 | (0.68, 1.96) | 1.38 | (0.67, 2.84) | 3.30 | (1.83, 5.94) |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 3.24 | (1.96, 5.37) | 1.06 | (0.69, 1.61) | 2.63 | (1.41, 4.92) | 3.11 | (1.90, 5.09) |

| $60,000 – $99,999 | 1.43 | (0.96, 2.13) | 0.87 | (0.59, 1.27) | 1.60 | (0.97, 2.63) | 2.08 | (1.31, 3.32) |

| Unit component | ||||||||

| Active duty only | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Reserves only | 0.43 | (0.28, 0.66) | 0.68 | (0.45, 1.04) | 0.38 | (0.23, 0.64) | 0.39 | (0.22, 0.67) |

| Both active duty and reserves | 0.69 | (0.46, 1.03) | 0.82 | (0.56, 1.20) | 0.59 | (0.36, 0.96) | 1.09 | (0.73, 1.63) |

| Service branch | ||||||||

| Air Force only | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Army only | 1.73 | (1.01, 2.97) | 1.05 | (0.64, 1.72) | 2.28 | (1.20, 4.35) | 2.05 | (1.12, 3.75) |

| Navy only | 0.77 | (0.42, 1.40) | 0.82 | (0.46, 1.45) | 0.75 | (0.38, 1.49) | 1.10 | (0.54, 2.22) |

| Marine Corps only | 1.07 | (0.56, 2.02) | 1.03 | (0.56, 1.88) | 1.21 | (0.57, 2.57) | 1.60 | (0.77, 3.33) |

| National Guardb: All | 1.58 | (0.79, 3.17) | 1.11 | (0.58, 2.12) | 1.62 | (0.72, 3.64) | 1.83 | (0.85, 3.94) |

| VHA use in previous year | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yes | 3.35 | (2.29, 4.91) | 1.20 | (0.87, 1.65) | 2.52 | (1.56, 4.06) | 2.94 | (2.05, 4.21) |

| Deployed to OIF/OEF | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Yes | 0.81 | (0.55, 1.19) | 0.79 | (0.56, 1.13) | 0.76 | (0.48, 1.21) | 0.69 | (0.46, 1.04) |

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio, compared to referent group; CI = confidence interval.

Note: OR adjusted for sex, education, income, service branch, unit component, and age.

Other racial/ethnic group not shown.

National Guard is not a service branch but was asked in conjunction with military branch questions.

Relative to individuals with household incomes of $100,000 or more, a significantly higher proportion of those with household incomes under $30,000 were more likely to meet the Kansas GWI symptom criteria (aOR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.28, 4.52) and the CDC severe GWI criteria (aOR = 3.30, 95% CI = 1.83, 5.94) while those with household incomes between $30,000–$59,999 were more likely to meet Kansas GWI symptom criteria (aOR = 3.24, 95% CI = 1.96, 5.37), the CDC GWI criteria (aOR = 2.63, 95% CI = 1.41, 4.92), and the CDC severe GWI criteria (aOR = 3.11, 95% CI = 1.90, 5.09) and those with household incomes between $60,000–$99,999 were more likely to meet the CDC severe GWI criteria (aOR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.31, 3.32). Interestingly, the adjusted odds for meeting the Kansas GWI case status criteria were similar across all income groups.

Regarding unit component, relative to individuals who reported being active duty only, individuals who were in the reserves only had a lower adjusted odds of meeting the Kansas GWI symptom criteria (aOR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.28, 0.66), the CDC GWI case criteria (aOR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.23, 0.64), and the CDC severe GWI case criteria (aOR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.22, 0.67) while individuals who were in both active duty and reserves has a lower adjusted odds ratio for meeting the CDC criteria (aOR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.36, 0.96).

Relative to individuals who served only in the Air Force, individuals who served only in the Army were at higher risk of meeting the GWI symptom criteria (aOR = 1.73, 95% CI = 1.01, 2.97), the CDC GWI definition (aOR = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.20, 4.35), and the CDC GWI severe definition (aOR = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.12, 3.75). Individuals who used the VHA health care system had a higher odds of meeting the Kansas symptom criteria (aOR = 3.35, 95% CI = 2.29, 4.91), the CDC GWI definition (aOR = 2.52, 95% CI = 1.56, 4.06), and CDC GWI severe case definition (aOR =2.94, 95% CI = 2.05, 4.21).

4. Discussion

Almost 25 years after the 1990–91 Gulf War, veterans who served in that conflict continued to report excess rates of chronic symptoms in connection with the condition known as GWI. Absent an objective diagnostic test, identifying GWI for research and clinical purposes has relied on the use of case definitions that determine GWI case status primarily on the basis of veterans’ symptoms the most common of which are the CDC and Kansas definitions. The current study applied both base case definitions in relation to symptoms and health conditions reported in 2014–2016 by veterans in the GWECB cohort and evaluated their utility for distinguishing health problems reported by Gulf War veterans from those occurring in Gulf War era veterans who were not deployed to the Persian Gulf region.

Among those in the GWECB cohort who were deployed to the Gulf War theater of operations, 40% met the Kansas GWI criteria—similar to the 34% found in the 2000 Kansas study [4]. However, the prevalence among the deployed in the GWECB cohort who met the CDC GWI criteria (84%) and the CDC Severe GWI criteria (27%) far exceeded the 39% and 6% respectively observed in the original CDC study of Air Force veterans [5]. All four GWI case-related measures were associated with higher odds among deployed than non-deployed veterans in the GWECB cohort with data collected more than two decades following the war–suggesting that these GWI definitions have retained validity for identifying an ailment associated with service during the Persian Gulf War.

However, our findings also suggest that GWI case definitions developed over 20 years ago, based on symptoms and medical conditions affecting veterans at that time, may no longer adequately define a pattern of symptoms uniquely associated with 1990–91 Gulf War service. This is illustrated by our finding that, during the current study’s data collection (2014–2016), 80% of non-deployed era veterans reported symptoms consistent with the CDC GWI criteria. Comparisons between deployed Gulf War veterans and non-deployed era veterans, suggest that the symptom-based GWI case definitions evaluated by the present study may now describe an amalgam of overlapping symptoms associated with aging, wartime service, other factors, or some combination of those factors. As a result, these case definitions now provide markedly reduced specificity for accurately characterizing the unique profile of health problems linked to Gulf War service.

In applying the Kansas GWI definition, researchers have discretion regarding which conditions exclude an individual from being considered a GWI case. Steele [4] used two principles to select exclusionary diagnoses that could 1) account for the symptoms and/or 2) interfere with the veteran’s ability to report symptoms. Other exclusionary diagnoses have been considered including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, chronic kidney disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and “other conditions” identified by patients that clinicians determine meet the exclusionary principles [17–19]. Our approach approximated the originally published report of the Kansas GWI definition, but differed slightly based on item wording and interpretation of the clinical relevance of the conditions elicited on the GWECB survey. Differences in how research teams operationalize the exclusionary conditions illustrate challenges in comparing results across studies.

Exclusionary conditions are a key consideration for constructing case definitions, especially for disorders defined primarily by symptoms [1,20,21]. Among participants of the GWECB cohort, roughly 40% had at least one medical or psychiatric condition used as an exclusionary condition. When the Kansas definition was originally constructed, only 7% of deployed and 6% of non-deployed veterans met the exclusionary criteria [4]. Other studies have reported even higher rates [22]. Indeed, 69% of Gulf War veterans met the exclusionary criteria from the most restrictive analyses in a study based on participants of the Millennium Cohort conducted 20 years after the war [23]. How exclusionary conditions are applied can make it challenging to research whether or not comorbid conditions disproportionately affect those with GWI. This problem is exacerbated as the GW veteran cohort ages and accumulates age-related conditions that are considered exclusionary (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease) using the original Kansas criteria without modification. Further research is needed to identify a more current and clinically-relevant case definition that accommodates age-related factors, as recommended by the Government Accountability Office [10].

In any defined cohort, rates of diagnosed health conditions and chronic symptoms tend to increase as individuals age. Thus, not surprisingly, comparison of findings from original case-defining studies with more recent studies reporting population-based data have found that many categories of symptoms and diagnosed conditions have markedly increased over time in both deployed and non-deployed Gulf War era veterans [24,25]. Somewhat unexpectedly, results from this study and from the longitudinal Millennium Cohort [25] have found that younger relative to older veterans who were deployed to the Gulf War were at increased risk of meeting the GWI case definition and related measures, regardless of whether exclusionary conditions are utilized in defining outcomes of interest. Our findings indicate that relative to older veterans, younger veterans had a higher odds of meeting the Kansas symptom criteria, Kansas and CDC GWI case criteria, and CDC severe GWI definitions—indicating that the elevated occurrence of GWI and related outcomes in younger veterans is not adequately explained by the lower rate of exclusionary conditions in younger veterans. Other considerations may be related to differences in rank and job-duty during deployment, and in turn exposures to factors that may have contributed to the development of GWI.

Beyond recommending use of the Kansas and CDC definitions, the IOM further recommended that VA undertake an evidence-based process to develop a single, robust GWI case definition [1]. Efforts to develop a single, robust GWI case definition must address challenges related to characterizing an updated symptom profile uniquely associated with Gulf War service. To account for change over time, this requires studying symptoms which were reported in recent years. Research may investigate refining the definition as a function of which symptoms at what severity levels to include. Updated guidelines for defining GWI and applying case definitions for subgroups with and without comorbidities that might otherwise be considered an exclusionary condition could help researchers implement a unified approach for studying this condition.

Data collected within the first 5 years [4,5,23], 10 years [2,3], and now over 20 years following the war [24,25] have persistently demonstrated that veterans who served in the 1990–91 Gulf War experience a higher prevalence of a multisymptom illness based on self-reported symptoms and conditions. However, the gap in prevalence of symptoms reported between deployed and non-deployed for symptoms was much narrower in the GWECB cohort than the originally published studies [4,5]. This suggests that the current definitions of GWI need modifications to more specifically differentiate cases from non-cases in an aging cohort.

While self-reported symptom-based approaches have limitations, they are a valuable tool for understanding veterans’ health concerns and discovering excess symptom burden experienced by some groups. Emerging evidence has begun to elucidate the importance of biomarkers and the biological underpinnings of the symptom defined GWI phenotype [7,26,27]. The GWECB serves as a pilot study for the Veteran Affairs Cooperative Studies Program, CSP2006 Genomic Analysis of Gulf War Illness), a genetic analysis of the approximately 110,000 Gulf War era veterans who participate in the Veteran Affair’s Million Veteran Program [28]. Future advances in defining GWI may come from fully incorporating detailed data from electronic health records, biological samples, and refined use of self-reported information.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. Most prominently, our results were obtained from a sample of veterans who were not necessarily representative of the general population of Gulf War era veterans, due to the sampling strategy and study participation profile of the GWECB cohort. A strength of the GWECB is that a population-based sampling approach was used and thus had the potential to reach veterans who were and were not seeking help for ailments. Still, the low response rate suggests this sample may not generalize to all Gulf War veterans. Reasons for the response rate included veterans being unreachable, ineligible, opting out, and lost to follow-up [9]. Qualitative research based on this cohort suggested additional factors including privacy concerns, trust in government, time, convenience, and concerns about future use of samples [29].

The data collected for the current study required modifications from the original Kansas and CDC case defining criteria, as previously described. First, the GWECB did not ask veterans to report when they began experiencing symptoms and thus symptoms could have begun prior to deployment to the Persian Gulf. However, an analysis by Smith [2] found that the prevalence of GWI was similar in their cohort of GW veterans regardless of whether or not determination of GWI was restricted to only consider symptoms which were began following deployment [2]. Unlike the original Kansas definition, the GWECB did not ascertain whether the individual had been hospitalized for a psychiatric condition [4]. The current study ascertained VHA use by asking if respondents had used the VHA health care system in the prior year. However, this analysis was unable to account for earlier VHA use.

5. Conclusions

GWI remains a prominent concern for veterans who served in the Persian Gulf War. Relative to non-deployed Gulf War era veterans, veterans deployed to the Persian Gulf War had higher rates of GWI-related measures. As veterans who served in the Persian Gulf War age and acquire additional symptoms and diagnosed conditions, GWI case definitions developed in the 1990s, have become less effective at characterizing the multisymptom health condition that is uniquely associated with military service in the Gulf War. Studies seeking to identify more objective diagnostic tests of GWI are underway. The GWECB pilot study is examining genetic and other information from blood samples and informing analyses specific to the study of GWI from the Million Veteran Program [30]. By combining veteran-reported symptom information with medical record, genetic, and other biomarker information, the GWECB provides a resource to gain new insights into the development of treatments of GWI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Veterans who volunteered to participate in the GWECB, the CSP585 executive committee, and all study staff members who have contributed to this project since its inception. We thank Grant D. Huang, MPH, PhD, and Timothy J. O’Leary, MD, PhD (VHA Office of Research Development), for their guidance and support of this work. The research reported here was supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs, Cooperative Studies Program (CSP585 and CSP2006, the Million Veteran Program), Department of Veteran Affairs Post-Deployment Health Services and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (VA HSRD CIN 13–413) in the Michael E. DeBakey (VHA Medical Center, Houston, Texas). Vahey’s time was supported through the T32 training grant (5T32-GM071340). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Appendix A

Fig. A1.

Flow chart for inclusion in the analytic dataset.

Table A1.

CDC symptoms and symptom domains by 1990–91 Gulf War deployment status.

| Symptom domain | Symptom | Deployed (n = 849) |

Did not deploy (n = 267) |

aOR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| (%) | (%) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Fatigue | Fatigue | 69.0 | 55.1 | 1.95 | (1.45, 2.61) |

| Musculoskeletal | Pain in joints | 82.4 | 76.8 | 1.48 | (1.05, 2.08) |

| Pain in muscles | 64.7 | 56.2 | 1.49 | (1.12, 1.99) | |

| Stiffness in joints | 78.6 | 75.3 | 1.22 | (0.87, 1.69) | |

| Mood-cognition | Difficulty remembering recent information or difficulty concentrating | 66.7 | 53.9 | 1.77 | (1.32, 2.36) |

| Difficulty remembering recent information | 58.0 | 44.6 | 1.76 | (1.33, 2.34) | |

| Difficulty concentrating | 57.4 | 40.4 | 2.08 | (1.56, 2.78) | |

| Trouble finding words when speaking | 51.8 | 44.6 | 1.37 | (1.03, 1.82) | |

| Feeling moody | 58.2 | 46.4 | 1.65 | (1.24, 2.21) | |

| Feeling down or depressed | 53.9 | 39.3 | 2.00 | (1.49, 2.70) | |

| Difficulty getting to or staying asleepa | 75.1 | 62.2 | 1.91 | (1.41, 2.58) | |

| Feeling anxious | 52.3 | 37.8 | 1.90 | (1.41, 2.55) | |

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio for Gulf War deployed vs. non-deployed era veterans; CI = confidence interval.

Note: OR adjusted for adjusted for sex, education, income, and age.

This symptom is used in both the Kansas and CDC GWI case criteria; However, it is included in the fatigue domain in the Kansas definition and in mood-cognition domain in the CDC definition.

Table A2.

Frequency of veteran-reported exclusionary conditions by 1990–91 Gulf War deployment status.

| Alla (N = 1116) |

Deployed (n = 849) |

Did not deploy (n = 267) |

aOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Any exclusionary condition | 40.4 | 40.3 | 40.8 | 1.05 | (0.78, 1.42) |

| Cancer | 9.2 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 0.96 | (0.60, 1.54) |

| Brain cancer | sup. | sup. | sup. | _b | _b |

| Breast cancer | 1.0 | 0.7 | sup. | 0.41 | (0.10, 1.67) |

| Colon cancer | sup. | sup. | sup. | _b | _b |

| Lung cancer | sup. | sup. | sup. | _b | _b |

| Prostate cancer | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1.43 | (0.59, 3.48) |

| Other cancer | 5.4 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 0.84 | (0.46, 1.52) |

| Diabetes | 17.0 | 17.4 | 15.7 | 1.24 | (0.83, 1.85) |

| Heart disease | 8.7 | 7.9 | 11.2 | 0.81 | (0.50, 1.33) |

| Heart attack | 4.2 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 0.66 | (0.34, 1.26) |

| Coronary artery disease | 6.4 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 1.03 | (0.57, 1.84) |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 0.73 | (0.31, 1.72) |

| Stroke | 3.4 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 0.52 | (0.26, 1.04) |

| Stroke | 2.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.48 | (0.20, 1.16) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1.7 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 0.47 | (0.18, 1.21) |

| Infectious disease | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 0.85 | (0.45, 1.63) |

| HIV | 0.6 | 0.7 | sup. | 1.94 | (0.22, 17.34) |

| Tuberculosis | 2.3 | 2.5 | sup. | 1.35 | (0.50, 3.69) |

| Hepatitis C | 2.0 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 0.44 | (0.18, 1.09) |

| Liver disease | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 0.77 | (0.31, 1.93) |

| Lupus | 1.1 | 1.3 | sup. | 3.05 | (0.36, 25.67) |

| Mental health | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.17 | (0.53, 2.58) |

| Schizophrenia | 0.5 | sup. | sup. | 0.95 | (0.09, 9.71) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 1.07 | (0.48, 2.38) |

| Neurological | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 0.92 | (0.47, 1.79) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 0.7 | sup. | sup. | 0.39 | (0.08, 1.81) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 1.08 | (0.52, 2.27) |

Note: OR adjusted for sex, education, income, service branch, unit component, and age.

Includes 75 individuals who were deployed in support of the Persian Gulf war but not to the Gulf War Theater or Operations.

OR undefined due to zero cell size.

aOR = adjusted Odds Ratio for Gulf War deployed vs. non-deployed era veterans; CI = confidence interval; sup. = suppressed for cell sizes fewer than 5.

Table A3.

Association of demographic, military and deployment characteristics with Kansas GWI exclusionary criteria status.

| All (n = 1116) | Met exclusionary conditions | p-value from χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Yes (n = 451) | No (n = 655) | ||||

|

|

|

|

|||

| (%) | (%) | (%) | |||

|

| |||||

| Sex | Male | 76.8 | 79.2 | 75.2 | 0.1232 |

| Female | 23.2 | 20.8 | 24.8 | ||

| Age Group | 40–49 years | 38.7 | 30.2 | 44.5 | <0.0001 |

| 50–59 years | 36.9 | 33.3 | 39.4 | ||

| 60 years and over | 24.4 | 36.6 | 16.1 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | White, Not Hispanic | 65.1 | 59.4 | 68.9 | 0.0026 |

| Black, Not Hispanic | 17.2 | 20.0 | 15.3 | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 9.5 | 10.0 | 9.2 | ||

| Other | 6.2 | 7.1 | 5.6 | ||

| Household income per year | Under $30,000 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 10.2 | <0.0001 |

| $30,000 – $59,999 | 23.1 | 28.2 | 19.7 | ||

| $60,000 – $99,999 | 29.0 | 30.2 | 28.3 | ||

| $100,000 or more | 29.8 | 20.8 | 35.8 | ||

| Unknown | 6.9 | 8.2 | 6.0 | ||

| Highest achieved education level | High School diploma/GED or less | 9.0 | 12.0 | 6.9 | 0.0003 |

| Some college to Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree | 68.2 | 70.3 | 66.8 | ||

| Master’s degree, Professional degree, or Doctorate degree | 20.7 | 15.3 | 24.4 | ||

| Unknown | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | ||

| Deployed to the 1990–91 Gulf War | Deployed | 76.1 | 75.8 | 76.2 | 0.8751 |

| Did not deploy | 23.9 | 24.2 | 23.8 | ||

| Unit Component | Active duty only | 60.6 | 60.5 | 60.6 | 0.3338 |

| Reserves only | 14.6 | 13.1 | 15.6 | ||

| Both active duty and reserves | 24.4 | 26.2 | 23.2 | ||

| Service Branch | Army only | 45.5 | 48.8 | 43.3 | 0.0517 |

| Navy only | 16.1 | 14.4 | 17.3 | ||

| Air Force only | 11.0 | 10.6 | 11.3 | ||

| Marine Corps only | 12.5 | 9.8 | 14.4 | ||

| National Guard: all | 9.8 | 10.0 | 9.6 | ||

| Other | 5.0 | 6.4 | 4.1 | ||

| Used VHA health care or hospital in the last year | Yes | 44.3 | 54.6 | 37.3 | <0.0001 |

| No | 54.9 | 44.8 | 61.8 | ||

| Deployed in support of OEF or OIFa | Yes | 21.7 | 19.3 | 23.3 | 0.0951 |

| No | 76.5 | 79.4 | 74.6 | ||

OEF=Operation Enduring Freedom; OIF=Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Percents sum to less than 100% because blank and write-in responses not included.

References

- [1].Institute of Medicine, Chronic Multisymptom Illness in Gulf War Veterans: Case Definitions Reexamined, The National Academics Press, Washington (DC), 2014, 10.17226/18623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Smith BN, Wang JM, Vogt D, Vickers K, King DW, King LA, Gulf War illness: symptomatology among veterans 10 years after deployment, J. Occup. Environ. Med. 55 (1) (2013) 104–110, 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318270d709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Blanchard MS, Eisen SA, Alpern R, Karlinsky J, Toomey R, Reda DJ, et al. , Chronic multisymptom illness complex in Gulf War I veterans 10 years later, Am. J. Epidemiol. 163 (1) (2006) 66–75, 10.1093/aje/kwj008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Steele L, Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service, Am. J. Epidemiol. 152 (10) (2000) 992–1002, 10.1093/aje/152.10.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fukuda K, Nisenbaum R, Stewart G, Thompson WW, Robin L, Washko RM, et al. , Chronic multisymptom illness affecting Air Force veterans of the Gulf War, JAMA 280 (11) (1998) 981–988, 10.1001/jama.280.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wolfe J, Proctor SP, Erickson DJ, Hu H, Risk factors for multisymptom illness in US Army veterans of the Gulf War, J. Occup. Environ. Med. 44 (3) (2002) 271–281, 10.1097/00043764-200203000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Research Advisory Committee on Guf War Veterans’ Illnesses, Gulf War Illness and the Health of Gulf War Veterans, US Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nugent SM, Freeman M, Ayers CK, Winchell KA, Press AM, O’Neil ME, et al. , A systematic review of therapeutic interventions and management strategies for Gulf War illness, Mil. Med. 186 (1–2) (2020) e169–e178, 10.1093/milmed/usaa260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Khalil L, McNeil RB, Sims KJ, Felder KA, Hauser ER, Goldstein KM, et al. , The Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository: a longitudinal research resource of veterans of the 1990–1991 Gulf War Era, Am. J. Epidemiol. 187 (11) (2018) 2279–2291, 10.1093/aje/kwy147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].United States Government Accountability Office, Improvements Needed for VA to Better Understand, Process, and Communicate Decisions on Claims, United States Government Accountability Office, Washington, DC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cooperative Studies Program, Office of Research and Development, Veterans Health Administration, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Gulf War Era Veterans’ Survey. A Survey of Men and Women Who Served our Country between 1990–1991, Department of Veterans Affairs Gulf War Era Cohort and Biorepository, Durham, NC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vahey J, Hauser ER, Sims KJ, Helmer DA, Provenzale D, Gifford EJ, Research Tool for Classifying Gulf War Illness Using Survey Responses: Lessons for Writing Replicable Algorithms for Symptom-based Conditions, 2020. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [13].Dursa EK, Barth S, Porter B, Schneiderman A, Gulf War illness in the 1991 Gulf War and Gulf era veteran population: an application of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Kansas definitions to historical data, Journal of Military and Veteran’s Health 26 (2) (2018) 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- [14].American Cancer Society, Key Statistics for Melanoma Skin Cancer, 2020.

- [15].Yee MK, Janulewicz PA, Seichepine DR, Sullivan KA, Proctor SP, Krengel MH, Multiple mild traumatic brain injuries are associated with increased rates of health symptoms and Gulf War illness in a cohort of 1990–1991 Gulf War Veterans, Brain Sciences 7 (7) (2017) 79, 10.3390/brainsci7070079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].SAS Institute, SAS® 9.4, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, United States, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Engdahl BE, James LM, Miller RD, Leuthold AC, Lewis SM, Carpenter AF, et al. , A magnetoencephalographic (MEG) study of Gulf War illness (GWI), EBioMedicine 12 (2016) 127–132, 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Janulewicz P, Krengel M, Quinn E, Heeren T, Toomey R, Killiany R, et al. , The multiple hit hypothesis for Gulf War illness: self-reported chemical/biological weapons exposure and mild traumatic brain injury, Brain Sciences 8 (11) (2018) 198, 10.3390/brainsci8110198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Holodniy M, Kaiser JD, Treatment for Gulf War illness (GWI) with KPAX002 (methylphenidate hydrochloride + GWI nutrient formula) in subjects meeting the Kansas case definition: A prospective, open-label trial, J. Psychiatr. Res. 118 (2019) 14–20, 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wolfe F, Clauw D, Fitzcharles M, Goldenberg D, Katz R, Mease P, et al. , The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity, Arthritis Care & Research 62 (5) (2010) 600–610, 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fukuda K, Straus S, Hickie I, Sharpe M, Dobbins J, Komaroff A, The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group, Ann. Intern. Med. 121 (12) (1994) 953–959, 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Coughlin SS, McNeil RB DT Provenzale, E.K. Dursa, C.M. Thomas, Method issues in epidemiological studies of medically unexplained symptom-based conditions in veterans, Journal of Military Veterans Health 21 (2) (2013) 4–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nisenbaum R, Barrett DH, Reyes M, Reeves WC, Deployment stressors and a chronic multisymptom illness among Gulf War veterans, J. Nerv. Ment. Disord 188 (5) (2000) 259–266, 10.1097/00005053-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zundel CG, Heeren T, Grasso CM, Spiro A, Proctor SP, Sullivan K, et al. , Changes in health status in the Ft. Devens Gulf War Veterans Cohort: 1997–2017, Neuroscience Insights 15 (2020) 1–7, 10.1177/2633105520952675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Porter B, Long K, Rull RP, Dursa EK, Prevalence of chronic multisymptom illness Gulf War illness over time among millennium cohort participants, 2001–2016, J. Occup. Environ. Med. 62 (1) (2020) 4–10, 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Abou-Donia MB, Conboy LA, Kokkotou E, Jacobson E, Elmasry EM, Elkafrawy P, et al. , Screening for novel central nervous system biomarkers in veterans with Gulf War illness, Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 61 (2017) 36–46, 10.1016/j.ntt.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC, Li K, Wang L, Monk JM, Bright AT, et al. , Metabolic features of Gulf War illness, PLoS One 14 (7) (2019), e0219531, 10.1371/journal.pone.0219531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gaziano JM, Concato J, Brophy M, Fiore L, Pyarajan S, Breeling J, et al. , Million veteran program: A mega-biobank to study genetic influences on health and disease, J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70 (2016) 214–223, 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Grewe ME, Khalil L, Felder K, Goldstein KM, McNeil RB, Sims KJ, et al. , Gulf War era Veterans’ Perspectives on Research: A Qualitative Study, 2021. (under review). [DOI] [PubMed]

- [30].U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, MVP research 2020. [Available from: https://www.research.va.gov/MVP/research.cfm.