Abstract

The year 2020 has witnessed the emergence of coronavirus (COVID-19) that has rapidly spread and adversely affected the global economy, health, and human lives. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the limitations of existing healthcare systems regarding their inadequacy to timely and efficiently handle public health emergencies. A large portion of today’s healthcare systems are centralized and fall short in providing necessary information security and privacy, data immutability, transparency, and traceability features to detect fraud related to COVID-19 vaccination certification, and anti-body testing. Blockchain technology can assist in combating the COVID-19 pandemic by ensuring safe and reliable medical supplies, accurate identification of virus hot spots, and establishing data provenance to verify the genuineness of personal protective equipment. This paper discusses the potential blockchain applications for the COVID-19 pandemic. It presents the high-level design of three blockchain-based systems to enable governments and medical professionals to efficiently handle health emergencies caused by COVID-19. It discusses the important ongoing blockchain-based research projects, use cases, and case studies to demonstrate the adoption of blockchain technology for COVID-19. Finally, it identifies and discusses future research challenges, along with their key causes and guidelines.

Keywords: COVID-19, Blockchain, Healthcare, Traceability, Security

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a respiratory infection that has globally affected various sectors such as the economy, healthcare, transportation, and education, to name a few. Health agencies such as the world health organization (WHO) have recommended several protective measures to immediately respond to and limit the unprecedented global spread of COVID-19. The scarcity of medical supplies and hospital capacity has forced government authorities to impose a partial or complete lockdown to contain the spread of the infection. Prevention from the adversarial effects due to the spread of COVID-19 requires coordinated action and collaboration among the health professionals, authorities, research institutes, and government [1–3]. However, the legacy information management systems being used to store crucial COVID-19-related data are mostly disintegrated [4, 5]. Disintegrated systems suffer from a lack of adequate means to share data and can create information silos for participating organizations. Information silos can minimize collaboration opportunities among participating organizations to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of technologies such as blockchain can assist business organizations in minimizing the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The inherent features of blockchain technology can foster information sharing and present a unified view of data to improve the coordination and actions of organizations to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

Numerous technology-based applications have been developed worldwide to assist authorities in closely monitoring public health to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, many corporate sectors, such as Google and Apple, have recently launched contact-tracing applications that can help authorities trace COVID-19-infected persons. Existing solutions, however, require access to personal data such as an individual’s location and COVID-19 test results in order to identify the spread rate and predict viral hotspots within a community [6, 7]. A large portion of the proposed systems have followed a centralized architecture to access, store services, and manage data related to COVID-19. For instance, Singapore’s contact tracing solution, called TraceTogether, employs Bluetooth technology to discover the close contact of a person with an infected patient with COVID-19 [6, 8, 9]. Being a centralized, governed solution, the contact tracing service providers can access user data and compromise data privacy. Similarly, the data records and transactions in centralized-based systems are vulnerable to modifications, fraud, or deletion. Furthermore, centralized systems are less trustworthy due to the possibility of a single point of failure [10, 11]. They can offer limited opportunities for collaboration among organizations, including healthcare, government, and law enforcement agencies [12]. Also, centralized systems fall short of providing traceability, transparency, and immutability of data stored and exchanged during various operational processes to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic [13].

Blockchain is a distributed, decentralized, and immutable record of transactions that are stored on a distributed network of nodes across geographically dispersed locations [3, 14, 15]. The decentralization feature of blockchain technology provides high security and robustness to the data and transactions stored on the blockchain, with no possibility of a single point of failure attack. The record of transactions and data stored on the blockchain is transparent to each member of the network, which builds trust in the reliability and availability of data [3, 16]. Miner nodes in the blockchain network validate the new transactions and add them to the existing blockchain ledger as a new block. Miners are usually rewarded with cryptocurrencies for their mining services. For instance, the proof-of-work (PoW) consensus protocol assures that a miner uses its computational power to solve a cryptographic puzzle for mining a block [16–18]. The integrity of transactions on the blockchain network is assured through hashing algorithms and asymmetric cryptography. Blockchain uses asymmetric cryptography to validate the authenticity and integrity of data. Blockchain technology employs hashing (a cryptographic algorithm) to link each block with its predecessor, making the data on the blockchain immutable. In general, blockchain platforms are categorized as permissionless or permissioned blockchain. Any user can join, make transactions, and participate in the mining process on the permissionless blockchain (also known as public blockchain) platform [3, 19]. A permissioned blockchain, on the other hand, is an invitation-only network that is typically managed by a single organization [20]. Access privileges to transact on a permissioned blockchain are limited to members of the organization only [3, 16, 21–23]. Hyperledger Fabric and Quorum are permissioned blockchains that allow organizations restricted access to the ledger. Unlike private blockchain platforms, which are managed by a single organization, consortium platforms enable several organizations to control and manage the data on them. Furthermore, consortium and private blockchain platforms offer higher performance and efficiency than public blockchain platforms. Also, the transaction execution time of the consortium and private blockchain platforms is lower than that of the public blockchain platforms. Consortium and private blockchain platforms offer higher data privacy and security compared to public blockchain platforms. The cost of executing a transaction on a public blockchain platform is lower than the cost of executing a transaction on a permissioned blockchain platform [16, 24, 25].

Blockchain technology employs smart contracts to automate business processes and resolve disputes among healthcare collaborators in a reliable and trusted way [26, 27]. A smart contract is a self-executing program that establishes trust among the participating organizations [7, 28, 29]. For instance, in a blockchain-based system used for logistic supply chain management of COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing kits, smart contracts can play a pivotal role to (a) track the location of shipping containers of testing kits, (b) identify flawed testing kits, (c) monitor the state of testing kits during their shipment, (d) and allow government officials to access data to analyze demand and supply of testing kits in a particular area. Moreover, smart contracts can simplify enrollment, execution, and managerial processes related to vaccine trial tracking, coronavirus disease diagnosis, COVID-19 hotspot identification, COVID-19 outbreak tracking, and user data privacy assurance through the registration services of premissioned blockchain platforms [30–34]. Also, smart contracts can assist in identifying, verifying, and preventing the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 [35]. To date, there exist a few surveys that have explored the pivotal role of blockchain technology in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike the existing surveys, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

It discusses the potential blockchain applications for the COVID-19 pandemic primarily from the public health emergency perspective. Each identified opportunity is further investigated by demonstrating its key role in multiple use-case scenarios.

It presents the high-level design of blockchain-based systems for COVID-19 data tracking, digital medical passports, and digital contact tracing to highlight their system-level components, participants, and roles definition.

It provides insightful discussions on recent ongoing research projects to show the practicality of blockchain technology in different domains for implementing healthcare services to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

It identifies and discusses several key open research challenges that hinder blockchain technology from fully realizing its potential to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The methodology of this research consists of the following steps:

Step 1: A combination of important keywords such as ’CoV’, ’COVID-19’, and ’Blockchain’ has been used to formulate search queries that follow the formulated research questions. The formulated search queries have been executed on several digital libraries (Web of Science, PubMed, Google, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Scopus) to identify and collect the most related studies.

Step 2: In the next stage, the collected articles are scrutinized, and duplicate articles are manually removed from the repository by comparing their titles. Subsequently, the remaining articles were re-scrutinized to consider only those that are published in English.

Step 3: The next stage further scrutinized the collected articles by selecting only conferences, journals, white papers, magazines, and online web resources to report published data.

Step 4: The published articles are reviewed to identify applications, use cases, blockchain-based research projects, case studies, and opportunities for blockchain to combat COVID-19. Through a qualitative research approach, the user requirements, use case participants, and blockchain opportunities for several identified applications are discussed.

Step 5: The research challenges that can affect the successful implementation of the identified use cases in combating COVID-19 are discussed.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 explores the potential opportunities offered by blockchain technology to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, illustrates several use cases and applications, and reviews recently reported blockchain-based research projects for combating the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 3 presents a discussion on the research challenges associated with the use of blockchain to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 4 discusses the conclusions and potential opportunities for future research.

Blockchain applications, research projects, and case studies for COVID-19

Blockchain applications for fighting COVID-19

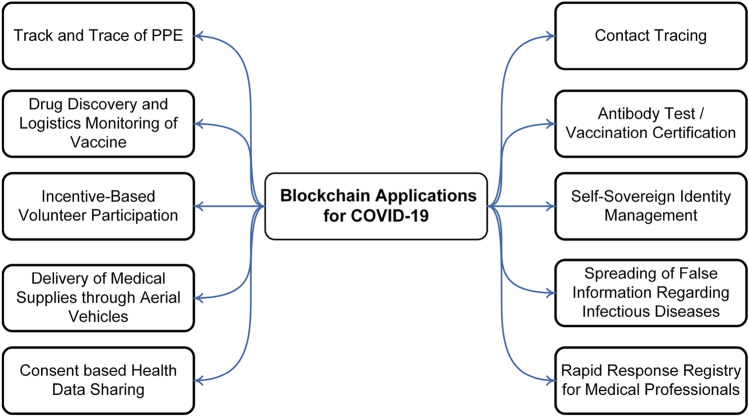

Blockchain technology can assist in building a transparent and efficient healthcare system to combat the COVID-19 pandemic through trusted, verified, distributed, and tamper-resistant ledger technology. It can create the first line of defense through a network of connected devices. In this section, the potential applications and use cases that blockchain technology can provide to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic are discussed. Figure 1 outlines the key services requiring high operational transparency, data provenance, privacy, and security to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Leveraging blockchain applications for the COVID-19 pandemic

Track and trace of personal protective equipment

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by individuals having exposure to transmittable disease (COVID-19) can greatly prevent and control the spread of the virus. For example, during a COVID-19 health emergency, the use of PPE can reduce the exposure of front-line health professionals to infected people. Examples of PPEs that are primarily used to prevent contact with infected persons or surfaces include gloves, safety goggles, footwear, face masks, helmets, and protective clothing [36, 37]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many counties have reported a shortage of PPEs in hospitals due to a lack of a trusted system to present accurate data about demand and supply of PPEs. In some cases, due to a limited supply of PPEs and a sudden increase in demand in the health sector, medical professionals were forced to use tape to patch up torn masks in order to avoid contact with COVID-19 [37–41]. Several countries and organizations have experienced the supply of low-quality PPEs, including face masks. One of the reasons for the shipment of the low-quality PPE is the limited transparency in the logistics supply chain management process. The existing centralized-based PPE supply chain management systems are inherently incapable of efficiently tracing the data provenance of the PPEs in a trusted and reliable manner. As a result, determining the source of PPEs, as well as additional details such as the type of certification of the PPE, is difficult.

The ability of relevant healthcare organizations to use blockchain to control and manage the supply chain of PPE can greatly aid in detecting PPE-related fraud [39, 42]. It can help in building a more resilient supply chain for PPE [43]. Through blockchain-based systems, the participating organizations can verify the authenticity of PPE and identify any sign of tampering or inadequate handling during its shipment. Blockchain technology securely, immutably, and transparently stores all movements, ownership details, and modifications that are made to the PPE in a distributed ledger. Immutable logs of transactions that are performed by participating organizations support the auditability and provenance of PPE. Blockchain can assist to (a) secure supply chain operations and PPE certificates, (b) prevent compliance violations, (c) identify counterfeit PPEs through data provenance, (d) allow verifiable collateral-based payment settlements, (e) impose penalties on individuals for any failure to comply with safety measures, and (f) procure PPEs from the reputed, trusted, and certified manufacturers. Moreover, smart contracts that are programmed for managing access control and automation can assist governments, authorities, and medical companies to track and trace (in real time) the PPE to forecast demand. PPE traceability-enabled demand forecasting (using AI techniques)can aid in better allocating and reallocating available PPEs [44]. Moreover, through registered and authorized sensors, data can be collected about the available stock in the inventory, and smart contracts can automatically trigger notifications for the procurement managers to place an order for more PPEs to prevent the possible consequences of the PPE shortage [45]. To assure high transparency in the PPE supply chain, public blockchain platforms (Ethereum) should be deployed by the healthcare organizations to track and trace the PPE.

Drug discovery and logistics monitoring of vaccine

To curb the spread of COVID-19, it requires the successful and indispensable immunization of humans against the virus through the administration of an active vaccine. At the time of the writing of this paper, many research institutes and laboratories were in the process of conducting clinical trials of several vaccine candidates. The effectiveness, safety, and genuinity of the vaccine are of great concern to the authorities, governments, and research institutes, as the newly administered vaccine might adversely affect the health of an individual [42, 46–48]. The current centralized-based vaccine management systems face several challenges related to the threat of failing to successfully secure and distribute vaccines, and breaching the logistics supply chain of vaccines for malicious purposes. Fake pharmaceutical companies consider this limitation of technology as an opportunity to sell and distribute fake and counterfeit vaccines to cure COVID-19 patients. A fake, counterfeit, or substandard vaccine is mainly manufactured using substandard material [49, 50]. Employing poor manufacturing practices during the development of a vaccine can also result in substandard vaccines. The infiltration of fake, counterfeit, or substandard vaccines into the gray market can harm human lives [51]. For example, because of the lack of operational transparency, adversaries can successfully forge vaccine expiration or production data during manufacturing, processing, shipment, or consumption stages to increase profit [52, 53].

Blockchain technology can permanently store data related to various stages, phases, and events of the COVID-19 vaccine, such as (a) drug discovery, (b) drug development, (c) production, (d) certification, and (e) allotment to authorized organizations for immunization purposes [39]. Drug discovery identifies a compound therapeutically useful in treating COVID-19. Followed by several experimental stages such as synthesis, characterization, and screening of an object, each compound showing encouraging results is selected to develop the COVID-19 vaccine [54]. Blockchain technology can have numerous use cases in assisting the organizations involved in drug discovery [55]. In the drug discovery process, the experimentation equipment generates a massive volume of raw data. Subsequently, this data is processed using statistical tools to create refined data that improves the presentation of the data. Both raw and refined data represent much of the scientific evidence of the experiments performed to discover a drug. Given the scalability issues in existing blockchain platforms, raw and refined data files must be stored on distributed storage systems like IPFS, and hashes of such files must be recorded onto the ledger to provide immutable proof of contents. There could be a threat of hacking or alteration of genomic data by the competing drug discovery organizations. Blockchain can store hashes of timestamped genomic data files onto the ledger to eliminate the chances of data theft, fabrication, and hacking [56]. To protect the data, a system comprised of a public blockchain platform and a trusted network of servers (for proxy re-encryption) can be designed to securely share the hash of a file (containing genomic data) with legitimate users [57]. Furthermore, the designed system can create a collaborative environment by allowing far-located research laboratories to share their research findings (consent-based). Following the drug discovery phase, pre-clinical and clinical trial phases are conducted to assure that the drug is safe for use. Finally, after getting approval from authorities, developed drugs are shipped to hospitals.

In hospitals, medical professionals can access blockchain to identify, trace, and verify vaccine data before administering it. It can also be used for notification management purposes (in real time) through lightweight smart contracts. Smart contracts provide opportunities to detect vaccine-related frauds, assure zero downtime, and eliminate the role of third-party services to monitor COVID-19 vaccine logistics. The immutability feature ensures that the vaccine’s details cannot be changed or deleted by the adversaries. Smart contracts can identify and verify the expiration date of the vaccine in a trusted manner using records such as the manufacturing date and warranty period of the vaccine. Also, smart contracts can use provenance data to identify substandard and falsified vaccines manufactured and shipped by unauthorized manufacturers. For supply chain logistics services, smart contracts implemented on the public blockchain platforms can be configured to monitor the state of the container for temperature, humidity, pressure, and other indices to protect the COVID-19 vaccine during its shipment [43, 58]. The smart contracts can automatically notify the relevant authorities when the pre-assigned conditions for the shipment are violated. The sensors can further assist in identifying any illegal attempts that may disrupt the state of the packages carrying vaccines inside the shipping container. Any such activity can be recorded, audited to monitor non-compliance, and notified in real time to the relevant authority [59]. The other advantages of blockchain for logistics of the future vaccine for COVID-19 include (a) transaction settlement; (b) audit transparency; (c) accurate cost information; (d) automation; (e) reducing human errors; and (f) enforcing tariff and trade policies.

Incentive-based volunteer participation in clinical trials

Conducting clinical trials to develop the COVID-19 vaccine is a complex, time-consuming, and costly process. It requires close coordination and collaboration among organizations that are involved in clinical trials of vaccines, and they are often located at geographically distributed locations. Researchers, donors, and pharmaceutical companies are examples of the organizations that are actively involved in the clinical trials to successfully develop and administer the vaccine for COVID-19. The conventional centralized-based clinical trial data management systems face several challenges, mainly related to subject enrollment, limited performance and non-compliance with the clinical trial requirements, data privacy assurance, compliance with clinical trial rules for the health and safety of participants, and integrity of clinical trial data [7, 60–63]. Also, the centralized-based clinical trial management systems can present several versions of clinical trial data that can create information silos within organizations. As a result, it can lead to duplicated clinical trial data that is often stored and managed by multiple organizations. Thus, duplication of clinical trial data makes it difficult to access, process, and analyze results. Also, centralization makes clinical trial data vulnerable to modifications by external hackers or participants. In addition to the data management issues, fair and transparent incentive sharing is challenging for the centralized incentive-based clinical trial management systems. To incentivize participants, centralized incentive-based clinical trial management systems rely primarily on a centralized intermediary service. Incentivizing through intermediary services is both expensive and time-consuming. Also, the existing centralized intermediary services are unable to handle micropayments in a cost-efficient manner.

Blockchain technology can enable pharmaceutical companies and research institutes to preserve the integrity of clinical trial data during the development of a vaccine. It assures that a single and synchronized view of clinical trial data is available for all authorized organizations. Thus, it can successfully overcome issues such as clinical trial data duplication and inconsistency due to the disintegration of the existing centralized-based clinical trial management systems. The smart contracts can verify the access rights of an organization before permitting it to use clinical trial data, preserving data privacy and security. For compliance with clinical trial requirements, smart contracts can verify that the authorized clinical trial participants have digitally signed the consent form [60, 62] before triggering a transaction to read or write health data on the ledger. Therefore, anonymized data collection and verifiable consent management can enable participants to share their case records with the authorized organizations without disclosing their identities. Blockchain enables organizations to use encrypted addresses when transacting on the blockchain to preserve data privacy. Clinical trial activities such as participants’ registration, health data collection, and information sharing should stringently follow the guidelines specified in the clinical trial protocol. The secure tracking and data provenance features allow the food and drug administration (FDA) to confirm that clinical trial activities were carried out in accordance with the protocol guidelines [60, 64]. It is important to note that the study results for many of the vaccine development clinical trials registered at "clinicalTrials.gov" are either unavailable or inconclusive, affecting the health and safety of clinical trial participants [61]. Through the data and operational transparency in clinical trial management, authorized participants can view the current status of the ongoing clinical trials being conducted for COVID-19 vaccine development. Also, the authorities (the FDA) can monitor the trusted health data of the clinical trial participants in a real-time manner. The clinical trial data is analyzed using analytical tools for generating statistical reports to analyze the outcomes of the study. For example, blockchain-based smart contracts can help the FDA identify any serious adverse events (SAEs) caused by the injected vaccine and notify participants in real time [61, 65].

In clinical trial management, patients have the right to accept or reject the proposed changes to the rules specified in the clinical trial consent form. To handle such a problem, a framework named "SCoDES" is developed for consent management in clinical trials to preserve the privacy and confidentiality of users’ data [66]. The SCoDES is being implemented on a hyperledger fabric platform since private platforms (hyperledger fabric) are faster, more secure, and more reliable. Furthermore, private blockchain platforms are suitable for securely storing clinical trial participants’ health data and authorizing the FDA to view it. The private blockchain platform assures that the privacy of participants’ data is preserved by hiding their identities. Thus, suitable use cases for private blockchain platforms in clinical trial management include consent management [67], health data sharing and monitoring in multi-site clinical trials [68], clinical trial results sharing [69], and rewards and incentives for effective coordination, management, and monitoring of clinical trial activities by the authorities. However, the participant’s recruitment for clinical trial management services can be implemented through public blockchain platforms such as Ethereum. To retain the participants of the clinical trial, medicine companies usually offer tokens of appreciation to the participants in the form of cash or gift cards [70]. Smart contracts can assist in speeding up the payment process by providing an automated, transparent, and accountable mode for transferring cryptocurrencies. The transparency and accountability features also assure that the data can be used only for the purpose for which it is collected, increasing the trust of the users.

Delivery of remote healthcare and medical supplies

Using advanced remote health practices such as telehealth and telemedicine services to reduce the risk of contagious virus transmission can allow symptomatic patients to communicate with health specialists remotely via IT infrastructure [71, 72]. Remote diagnosis and treatment of patients can significantly minimize patient access and workforce limitations, and thus the employability of remote health services can effectively control and limit the rapid increase in global COVID-19 cases [2, 73, 74]. Being governed and managed by a centralized authority, remote healthcare systems are vulnerable to a single point of failure problem, which ultimately affects the integrity and trustworthiness of the electronic health records [75]. The inherent features of revolutionary blockchain technology can bring diverse benefits to the remote healthcare industry [30, 76–78]. The primary benefits include establishing the provenance of electronic health records [75], verifying the legitimacy of users demanding patient data, ensuring patient anonymity, and automating micropayments for using remote health services [72]. The traceability feature helps successfully establish the provenance of self-testing medical kits for COVID-19 testing. Following the testing outcome, individuals whose test results are negative are usually obliged to follow self-quarantine policies to mitigate the spread of the virus in society. The need for secure track and trace of medical supplies for self-quarantined individuals creates opportunities for blockchain technology to store time-stamped location data of medical supplies on the ledger transparently. To meet the key requirements of patients in terms of health data privacy and security, private or consortium platforms are preferred to implement remote healthcare services.

Maintaining social distance and wearing face masks while performing business activities (relevant healthcare participants) can help to reduce COVID-19 spread.The globally increasing COVID-19 confirmed cases demand contactless delivery of medicines to the patients, especially in areas of very high virus transmission rates, to further prevent COVID-19 from spreading. For this purpose, aerial vehicles can be used to deliver medicines and medical supplies to remote patients. Aerial vehicles can also assist in transporting medical supplies among hospitals that are housed in distant locations. For instance, China experimented (in 2020) with employing aerial vehicles to supply medicines from one city to another during the COVID-19 pandemic [78–80]. Blockchain technology can assist in tracking and tracing the location of the aerial vehicles, verifying the provisioned service level, and calculating the reputation score of an aerial vehicle based on its performance in a trusted, accountable, and transparent manner. Through implementing access control protocols and identity management, blockchain technology minimizes the possibility of attacks by adversarial vehicles. It immutably stores commands that are issued to the aerial vehicles (for audit purposes to verify non-compliance with issued commands) by the control room, along with actions to sanitize the highly virus-infected areas and detect human movements and interactions. A swarm is comprised of multiple autonomous aerial vehicles that work together to achieve a common goal. Blockchain technology can be used by a swarm of aerial vehicles to reach a highly reliable global decision by securely transacting on the blockchain. For instance, through a blockchain-based voting system, the aerial vehicles of a swarm can identify the most densely populated public places to spray disinfection [2, 80]. The public blockchain platforms are appropriate for the implementation of the voting service of an aerial vehicle’s swarm to make a decision.

Digital contact tracing

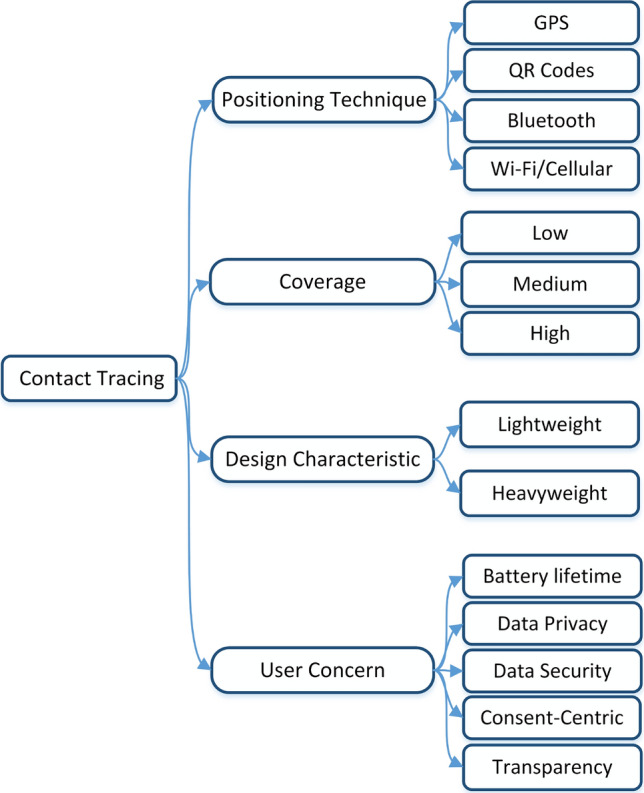

Respecting social distancing directives issued by the government can significantly minimize the social interactions of people to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Social distancing is implemented through a public health measure called "digital contract tracing" that can break the chain of person-to-person transmission of the virus. Digital contact tracing continuously monitors infected people to rapidly and effectively identify all social interactions that happened during the infectious incubation period of COVID-19-infected patients. It mainly employs GPS or Bluetooth to use proximity data to identify social interactions with a virus-infected individual. After encountering close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case, the exposed individuals are required to be tested, monitored, and self-quarantined [81, 82]. Transparency and immutability of data assure that the health data of users, such as the COVID-19 test result, cannot be altered or deleted by adversaries or healthcare collaborators. Also, it preserves the privacy of users’ data to comply with privacy rules as stated in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) privacy laws [81–90]. The design parameters necessary to design and implement a contact tracking solution for identifying social interactions among people are highlighted in Fig. 2. The positioning technique parameter states the technologies that can be used to identify the location of a user. The coverage area parameter defines the range of geographic areas within which a social interaction of a COVID-19 patient with another person can be traced. The heavyweight designs of a contact tracing application intend to use system resources aggressively during identification and verification of social interaction among people. On the other hand, the lightweight application design optimizes system resources by guiding users and providing the most important and needed features. The requirements of digital contact tracing users include an extended battery life of devices and high levels of privacy, security, and transparency of COVID-19-related data. Ideally, a digital contact tracing solution should provide high privacy of data, an extended coverage area, a lightweight application design, high data security and transparency, and battery-friendly operations.

Fig. 2.

Design parameters for digital contact tracing solutions

The key challenge for digital contact tracing solutions is ensuring the privacy of an individual’s personal health data while minimizing COVID-19 false-positives. The privacy of the data is preserved by encrypting the location and contact history of a person and preventing the disclosure of personal health data to the public [91]. On encountering close contact with a COVID-19-infected patient, users can be informed about the recent social interaction without disclosing the credentials of the infected individual. Bluetooth is used in digital contact tracing via smartphone apps such as TraceTogether in Singapore and Google-Apple contact tracing to identify a person’s close physical contact with a virus-infected individual. However, due to smartphone battery constraints, TraceTogether is not user-friendly [83]. Google/Apple Contact Tracing does not reveal users’ identities or locations, ensuring data privacy. Considering the high privacy and sensitivity of users’ data, the non-blockchain-based solutions are less trustworthy as they are vulnerable to data forging by the administrator of the application [6, 92]. The immutable and decentralized blockchain technology can be a viable alternative for digital contact tracing [93]. It can preserve the privacy of the user’s data by enabling pseudo-anonymity. To preserve data privacy, digital contact tracing using a regular expression matching technique can use the blockchain platform to store social interaction data and allow only authorized users to access the data (via a consent form) [13, 92].

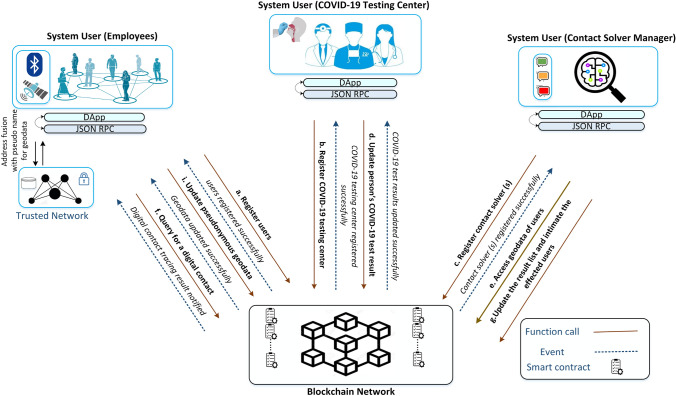

Figure 3 presents a digital contact tracing system that can be used by any organization to ensure safe distancing among its employees to restrain the virus from spreading. In the presented system, an external trusted network of servers is used to generate anonymous addresses for the users to preserve data privacy. The system has implemented many smart contracts, such as entity registration, a geodata processor, COVID-19 testing, query processing, and consent management, to automate services and assure that credentials about individuals who are infected with COVID-19 are not disclosed to others. Being a private blockchain-based system, all entities are registered before making a transaction on the blockchain. The geodata processor contract assures that duplicate data (location data of a user with limited mobility) is not forwarded to the contact solver to speed up the contact tracing process. The COVID-19 testing contract assists in recording COVID-19 test results on the blockchain for each employee. The consent management contract seeks to legalize the location data usage of employees of an organization. The contact solver component of the contact tracing system leverages AI-based techniques for identifying social interactions among individuals [8, 94]. It informs the users about possible risk levels based on many factors, such as distance, mobility, and total time spent during social interaction with a COVID-19-infected person.

Fig. 3.

Blockchain-based system for digital contact tracing to curb spreading of COVID-19

Vaccination certificates and immunity passports

Antibody testing, also called serology testing, specifies that a person has developed immunity against a virus (COVID-19) after full recovery from the virus. The vaccination certificate enumerates the diseases that a person has been vaccinated against. A vaccination certificate assists in preventing and controlling the spread of COVID-19 by enabling the authorities and governments to formulate policies by allowing cross-border travel for those who possess this certificate [95]. Therefore, the certificate’s forgery protection, high cost-effectiveness, and privacy assurance are the key requirements of the authorities to minimize travel-related frauds. Blockchain-based antibody testing and vaccine certification provide a robust and secure data management system that is easy to administer, unforgeable, and cost-effective [96–100]. Blockchain employs asymmetric encryption and decryption schemes [101] and digital signatures to protect antibody testing and vaccine certification data. Also, the decentralization feature assures protection of vaccine certificates against single points of failure or other malicious attacks, thereby increasing the trust of the users by improving data reliability and security. The immunity passport of citizens should be visible to only authorized organizations to preserve users’ data privacy and social and political issues. Therefore, private blockchain platforms are appropriate to implement this service.

The certificate of antibodies can be verified in a trusted way, along with the privacy of the user’s data. For example, when reopening business locations following the COVID-19 pandemic, many organizations can develop and implement policies that allow only employees with a valid digital immunity passport (based on antibody testing and vaccination) to return to work. In such a case, blockchain technology assures that due to the immutability feature, an invalid immunity passport can not be presented to the authorities to access the workplace. The intrinsic transparency and traceability features of blockchain assist in establishing the data provenance of the COVID-19 lab results (through data provided by certification authorities). It can further assist the organizations in verifying the legitimacy of the PCR testing kits that are used for COVID-19 testing. The key organizations or participants that could be involved in the antibody testing and vaccine certification use cases include employees, hospitals, and employers [96, 100, 102]. To conduct antibody testing, hospitals or testing centers (the immunity passport issuer) collect blood or swap samples. It creates a digital passport for the user to immutably record on the ledger. On the other hand, the employer (the immunity passport verifier) can be any organization or authority that verifies that the holder has a valid immunity passport to allow him to visit a building, city, conference, or country.

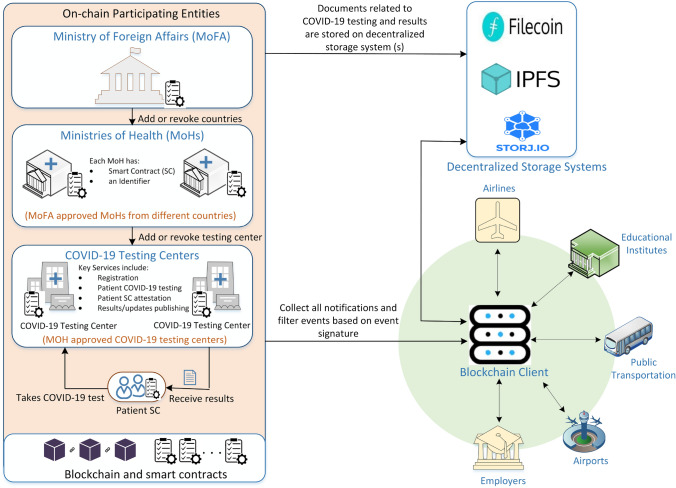

Figure 4 presents a high-level design of a private blockchain-based system (exemplary system) to create a digital medical passport to maintain the medical identity of citizens and curb the spread of COVID-19 [57]. It has implemented smart contracts to minimize medical-related frauds by presenting test results and medical information to the authorized users in a trusted, reliable, private, and secure manner. It has incorporated self-diverging identity, the interplanetary file system (IPFS), and proxy re-encryption to assist testing centers in providing medical passports and immunity certificates to users. Based on the medical passport, users can be allowed to travel. Upon presentation of a valid digital medical passport, the authorities may exempt an individual from various social restrictions.

Fig. 4.

High level design of a blockchain-based system for COVID-19 digital medical passports and immunity certificates

Data privacy and self-sovereign identity

Many COVID-19 prevention and control measures, such as strict lockdown, remote health care, and distance-based learning, have recently been implemented globally to minimize social interactions between humans and control the spread of COVID-19 [72]. The government agencies in South Korea had used the personal data of their citizens, including location data and credit card purchase histories, to track the outbreak of COVID-19. The traveling history of citizens, which is identified through their location data, was used to know where the citizens stayed before they were diagnosed positive against the COVID-19 test [3, 103]. Preserving the privacy of citizens’ data along with compliance with the GDPR privacy guidelines can lead to a trusted and dependable system. For many countries, the industry-standard privacy policies state that personally identifiable information should be shared with government agencies to assure the health and safety of citizens, or to fulfill a lawful obligation [104]. Public blockchain-based systems are vulnerable to data privacy breaches as they implement a zero-access control policy to access the blockchain network. However, because they are governed and managed by a single organization, private blockchain platforms are more reliable, trustworthy, and dependable to preserve the privacy of users’ data [104–107].

Organizations frequently sign and follow the consent form in order to share citizens’ health data (COVID-19 test result report) with government agencies. A consent form outlines the rules that define the purpose of sharing user data. The blockchain technology can assist the authorities in auditing the operations for any violations or non-compliance while handling or using citizen data in a secure and trustworthy manner. The blockchain-based smart contracts can assure that employees of an organization are immediately notified about their exposure to COVID-19-infected patients. It assures that the credentials of virus-infected individuals are not disclosed to others to preserve data privacy. Identity management self-sovereignty allows users to own and control their identities without the intervention of administrative authorities. It assures that an individual has full control over his data, and he can allow or reject the request by the organizations to share personal health data with them [108–111]. Through self-sovereign systems, the data privacy of an individual with symptomatic COVID-19 can be assured, as the user can refuse the request to share personal health data with a health specialist or researcher.

Rapid response registry for medical professionals

Fair allocation and protection of scarce and shareable medical resources in existing public healthcare systems are challenging amid the global COVID-19 pandemic. Many studies have concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed the world’s existing healthcare system [112]. In such a scenario, rapid and immediate decisions and actions by the authorities or governments in compliance with the agreed-on policies can assure the health and safety of their workers. In health systems, the making of policies for (a) allowing a caregiver to virtually visit quarantine patients, (b) increasing hospital staff and resources, (c) operating AI-based robots to facilitate health professionals to conduct COVID-19 testing, (d) delivering medical supplies through drones, and (e) educating the community to avoid the spreading of false information about COVID-19 can assist in fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic [113, 114]. In traditional healthcare systems, data about medical professionals, such as doctors and nurses, and resources usually sits in the silos of organizations or hospitals. As a result, it creates limited collaboration opportunities among medical professionals enrolled in different hospitals, which are often located at geographically scattered locations, to combat the COVID-19 pandemic [108, 115]. A rapid response registry system registers and maintains a list of medical professionals worldwide along with their roles and expertise to streamline coordination among hospitals or agencies and overcome the scarcity of medical professionals. Public blockchain platforms (along with proxy re-encryption servers [116]) should be considered to implement smart contracts designated for document sharing, payment settlements, physician’s skills verification, and research data sharing [117, 118].

Smart contracts deployed on the blockchain can assist in streamlining the coordinated actions of relevant healthcare organizations to efficiently identify appropriate medical professionals in a highly trustworthy and secure way. Because of a single and unified view of the healthcare data, the authorities can identify the resource capacity, allocation, and demand of a hospital in a seamless, transparent, and trusted manner. A blockchain-based rapid response registry system can allow medical students and health professionals (employed and unemployed) to register on the blockchain platform. A smart contract can continuously monitor the data to assure that it has a large enough pool of reserved medical professionals to provide on-demand services to the hospitals and minimize resource scarcity issues. The on-demand services of unemployed health professionals could be either volunteer or paid (verified through a consent form). After the registration stage, smart contracts can verify the educational certificates that are shared using IPFS servers, the skills that can be traced using blockchain, and other supporting documents to audit fraud. Through transparency and accountability features, it can assure that payments are settled for the services of healthcare professionals in compliance with the rules in the consent form. Similarly, medical professionals who are geographically dispersed can share patient data with COVID-19 via a unified and single blockchain-based health data repository, allowing researchers or health professionals to analyze it. Based on health data analysis, health professionals can learn and apply treatments that are effective for COVID-19 patients. For instance, the analysis of data can be helpful to identify the success rate of patients’ treatments through blood plasma. Details of the effectiveness of the medicines used for the treatment of COVID-19 should be published by the authorized organizations (WHO) on the public blockchain platform.

Tracking of COVID-19 data

In the COVID-19 pandemic, social media has become the most widely acclaimed tool for sharing information. However, due to the open nature of social networks, there is a high probability of misinformation, sensationalism, and rumors about the COVID-19 outbreak. Existing social media channels and websites are incapable to scrutinize and verify the information source [3, 7, 119, 120]. As a result, fabricated or falsified data related to the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare, or medical devices can cause panic and public confusion about who and which information sources can be trusted. It can lead to harmful self-medication and non-compliance by the public with policies designed by the government related to public movement restrictions and social distancing. Further, any prediction model or estimation of the future growth of COVID-19 using fabricated or falsified data will be meaningless [3, 43, 121]. The trustworthy data about COVID-19 can assist authorities, governments, and agencies to accurately identify infection hotspots within a geographical area and formulate a policy to curb the virus from spreading. Blockchain technology can successfully counter fake information. Using data provenance, it can detect any alteration to data made by adversaries. It assures high reliability, transparency, integrity, and availability of COVID-19 related data for medical professionals and researchers. Thus, tracking trusted COVID-19 data can assist authorities in improving planning and management decisions such as practicing lock-downs to isolate potentially infected territories and outbreak forecasting [3, 7, 121, 122]. To identify the fake news [119], a blockchain-based system can register, rank, and filter news based on the reputation of news agencies.

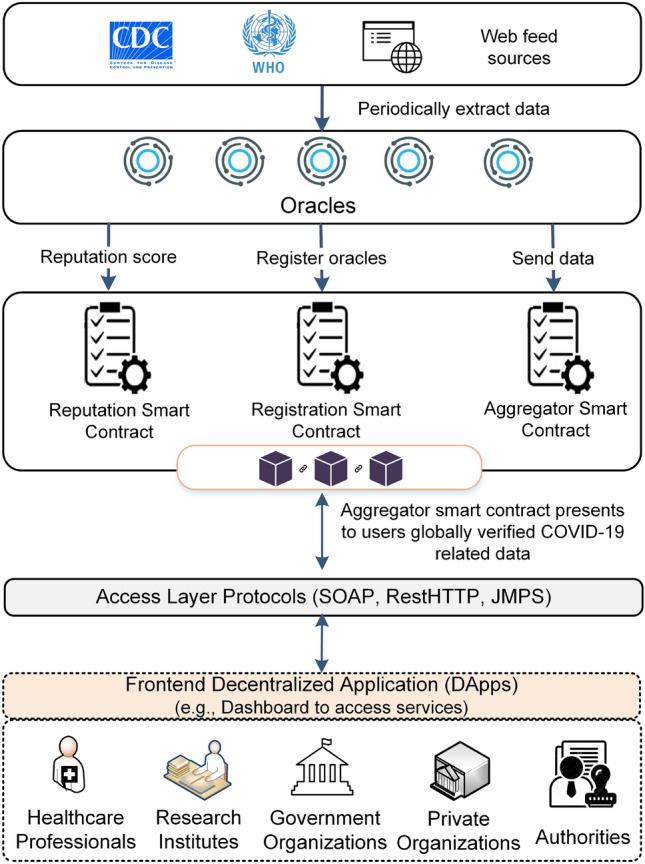

Figure 5 presents a generic exemplary public blockchain-based system that can be used to track COVID-19-related data, such as the development of medicines for patients with COVID-19, confirmed COVID-19-affected cases, and mortality rate in a particular country, in a highly secure, trusted, and immutable manner [7]. It employed registered oracles to fetch the COVID-19-related data from trustworthy sources such as WHO and the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC) websites. It calculates and updates the reputation score of oracles based on their performance behavior. It has implemented three smart contracts called registration, aggregator, and reputation smart contracts. Aggregator’s smart contract provides users with the most recent COVID-19 data. The reputation smart contract either increases or decreases the reputation score of the oracles based on their performance behavior.

Fig. 5.

Blockchain-based system for COVID-19 related data tracking through oracles and smart contracts

Insurance claims and donations tracking

Health insurance companies can employ trusted blockchain technology to accelerate their growth and market share. The traditional insurance systems face various challenges related to fraudulent claims, complex compliance issues, high convergence times and costs in processing insurance claims, and unverifiable transaction records. In contrast to traditional health insurance systems, blockchain’s accountability, transparency, and verification features can assist insurance companies in conducting audit trials of insurance claims presented by users using an immutable record of health insurance-related transactions [123]. Access to the complete health data about a COVID-19 patient and complying with the terms and conditions that are defined in the consent form can assist the insurers in verifying the patients’ claim in a secure, trusted, and timely fashion. To maintain a healthy lifestyle, insurance companies can give incentives to patients by offering them tokens. Blockchain technology can assist insurance companies in verifying the records of patients to automatically transfer tokens through self-executing smart contracts [124, 125]. The private blockchain platforms are more suitable to implement this use case, as the EHR of a patient should not be disclosed publicly to comply with data protection laws.

Traditional systems that are used for tracking fund donations face many challenges, such as a lack of transparency, trust, accountability, and traceability. Blockchain technology offers a peer-to-peer (P2P) architecture to directly transfer cryptocurrencies to the wallets of the affected people. It assists charitable organizations to verify the cryptocurrency transfers and receipts in a transparent, trusted, and accountable way. It saves time and money by eliminating the role of intermediaries to route the funds to the affected people [126, 127]. The inbuilt transparency, immutability, security, and trust features of blockchain technology can boost fundraising by charitable organizations. The traceability feature can assist the donors in verifying whether their donations are utilized properly. The adaptability of blockchain by charitable organizations can assist government officials in fairly distributing funds among a community’s affected citizens. For instance, because of high levels of traceability, transparency, trust, and security, government officials can verify the funds donated to a community in a particular geographical region. Based on the analysis, it can identify, guide, and direct the donors to a more affected community [2, 7, 126, 127]. Financial transactions (between communities) should be extremely transparent. Hence, a public blockchain platform should be considered to implement this use case.

Aside from the opportunities mentioned above, researchers have begun working to identify CVOID-19-infected individuals through wastewater analysis [128, 129]. Based on wastewater analysis, blockchain technology and AI techniques can assist the authorities in identifying and predicting future hotspots of COVID-19-infected patients in a city. Health professionals can analyze medical images (e.g., cough samples) with the help of AI techniques and data mining models to detect COVID-19 in a community [130, 131]. The rise in blood plasma donations is seen in many developing countries to treat COVID-19 patients [132, 133]. It can be helpful to store the details about plasma donors on the blockchain to verify the effectiveness of COVID-19 treatment through blood plasma donations. However, the privacy of donors’ data should be assured to avoid any criminal activity or political influence that might motivate an individual to donate blood plasma [134].

Summary: A detailed discussion about the potential opportunities of blockchain for the COVID-19 pandemic has been provided to enable government organizations, healthcare professionals, and regulatory authorities to efficiently handle the health emergency caused by the COVID-19 outbreak. It has been discussed how the existing blockchain-based systems help to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic by highlighting their system components, participants, and role definitions for various use cases. It has presented three exemplary blockchain-based systems that can act as a base and a guideline for researchers to propose new blockchain-based systems to implement the remaining seven use cases. The main reason for choosing such reference systems is their usefulness to the government, regularities, and law enforcement agencies in developing and following policies to curb the spread of COVID-19. For instance, the digital contact tracing system (presented in Fig. 3) can be used by government officials to propose and implement smart lockdowns in cities. It can also be used by business organizations and educational institutes to trace the health of their employees. The immunity passport-based system (presented in Fig. 4) can assist the authorities in reopening the businesses by allowing only healthy citizens to visit the business places. The third system, called COVID-19 data tracking (presented in Fig. 5), can be used by citizens and researchers to predict the outbreak of COVID-19 in different regions. It can further help to eliminate the spreading of fakes news about COVID-19. Note that the presented blockchain-based systems can be employed in the other seven use case scenarios as well with minimal efforts and modifications. This study has outlined and presented the system participants, main requirements, and key business processes involved in each use case scenario, which can enable researchers to develop and implement smart contracts using blockchain technology. The participating organizations for all the presented use case scenarios are enlisted in Table 1 to assist researchers in proposing new systems based on existing systems. The main requirements of the participants that should be considered while designing systems for the identified use cases are enumerated in Table 1. Finally, appropriate blockchain platforms are identified based on the needs and requirements of various use case scenarios.

Table 1.

The requirements and opportunities of blockchain technology for several use cases

| Application | Requirements | Blockchain opportunities | Participants | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track and trace of PPE |

Fast identification of counterfeit PPE Availability of provenance data about PPE High security of PPE related data |

Complete trace of PPE manufacturing history Automation of PPE supply chain operations Verification of authenticity of PPE Transparent and fast payment settlements |

PPE manufacturer PPE users Procurement manager Distributor Quality assurance manager |

Identifying PPE related frauds require that all participating organizations should be using blockchain technology. Using high quality and certified PPE can assist in minimizing the spread of COVID-19 |

| Logistics monitoring of vaccine |

Verification of genuinity of vaccine Protection of vaccine related data Guarantee of vaccine procurement from an authorized manufacturer |

Transparency of vaccine logistics operations Protection of trade documentations Establishing data provenance of substandard vaccine Prevention of compliance violation |

Vaccine manufacturer Drug authority Patients Shiping agencies Quality control manager Distributor |

Blockchain-based smart contracts can transparently calculate the reputation score for every vaccine manufacturer. Blockchain can enable relevant healthcare organizations to locate and buy genuine vaccines from reputed organizations |

| Incentive-based volunteer participation in clinical trials |

The correctness of clinical trials data Assurance of users data privacy Assurance of data access and usage in compliance with a consent form |

Assurance of compliance with clinical trial rules Audit of clinical trial operations Consistency of clinical trial data |

Researchers Regularities Donors Drug companies |

Blockchain technology can assist in minimizing the efforts required to manage clinical trial documentation |

| Delivery of remote healthcare and medical supplies |

Tracking the location of medical supplies Tracing the provenance of self-testing COVID-19 test kits Auditability of air vehicles operations |

Access to complete medical history of an individual Data access and control based on consent management |

Patient Aerial vehicles Pharmacy |

Immutable blockchain technology can help a buyer to view, verify, and validate the health score of a COVID-19 testing kit |

| Digital contact tracing |

Assurance of data privacy Assurance of data integrity High accuracy in identifying close contact with infected person Battery friendly design of application |

Seamlessly identify individuals that have come close contact with COVID-19 infected person Automation of process to notify the exposed individuals Real-time tracking of location of individuals |

Government authorities Hospitals/COVID-19 testing centers Individuals & employees Public/Private institutes & offices |

Existing solutions use handheld devices such as smartphone for digital contact tracing. Digital contact tracing solutions should be battery and CPU resource friendly |

| Vaccination certificates and immunity passports |

Integrity of vaccine certificate Assurance of data privacy Trust on COVID-19 antibody testing kits |

Identify counterfeit COVID-19 antibody testing kits Identify invalid immunity passport Identify valid vaccination certification |

Individuals & employee Hospitals/COVID-19 testing centers Government Vaccine manufacturer |

Blockchain can assist in assuring compliance with policies to present a valid immunity passport to authorities visit a place/country |

| Rapid response registry for medical professionals |

Registration of medical professionals Transparent medical resource sharing Access to skilled medical professionals |

Streamline hospital operations Verify skills of medical professionals Transparent payment settlement Verification of educational certificates |

Medical professionals Hospitals staff |

Blockchain can assist in availing the services of medical professionals locating geographically at distant locations |

| Insurance claims |

Fast insurance claims settlement Low cost Fraudulent claims verification |

Verifiability of insurance claims Monetization of health data Transparent payment settlement |

Insurance company Patient Physicians |

Blockchain can assist to quickly verify and process insurance claims of COVID-19 patients. It can assist patients to share their health data with insurers to monetize health data |

| Donation tracking |

Traceability of donation spending Fast donations processing Low operational cost |

Verifiability of donations spending Transparency in donation activities Audit trials of donations |

Donors Government Communities |

Blockchain provides transparency in activities related to funds transferring and consuming that can significantly increase the trust of donors |

| Data privacy and self-sovereign identity (EHR sharing case) |

Complete medical history Secure data sharing Consent-based operations |

Transparent data sharing Secure data processing Enforcement of consent contract |

Patient Primary physician Secondary physician |

Blockchain can assist the primary physician to securely share EHR with the secondary physician to seek his expert opinion (second opinion) on it |

Blockchain-based ongoing research projects and case studies for COVID-19

Many organizations have developed blockchain-based systems to offer trust, security, privacy, and operational transparency services in existing healthcare systems. The healthcare services implemented using blockchain-based systems include EHR protection, on-demand remote health monitoring, pharma drug supply chain and clinical trials, a genomic data marketplace, identity management, and health data analytics. Well-known companies such as Burstig, DOC.AI, Mediledger, Guardtime, Chronclid, CallHealth, and Embleema have developed blockchain-based systems to digitize several healthcare services [65]. Ddibloc, MedRec, MedBlock, SMEAD, WellLinc, and MeDShare are examples of blockchain-based systems that have digitized services from the healthcare industry [135–137]. This section presents recent ongoing research projects, use cases, and case studies to show how leveraging blockchain technology can help effectively handle a public health emergency caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Anonymous COVID-19 testing

Many cases of social discrimination, abuse, and harassment were reported worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which individuals suffering from COVID-19 symptoms were targeted for causing the pandemic and its spread. To avoid such social discrimination, hospitals or laboratories should preserve the privacy of the COVID-19-infected individuals. Epios is aimed at exploiting the Telos public blockchain platform to facilitate anonymous testing of individuals suffering from COVID-19. The Telos blockchain platform can transparently store and report anonymous test results of individuals and ensures that only authorized users (country managers and regional managers) can write test results on the platform. Telos’ blockchain platform has implemented a delegated proof-of-stake consensus algorithm to verify the transactions. The blockchain platform enables users to connect with laboratories that supply and process PCR testing kits in real time. Epios assures that the payment cannot be made directly to the test processing labs. Instead, it requires the testing kit providers to provide a coupon for each testing kit to users. Further, it cryptographically protects the coupon to assist the labs in verifying the payments without tracing the individual who purchased the PCR testing kit. Teloscoin (Telos) cryptocurrency is available on the Telos blockchain platform, allowing users to pay for used COVID-19 testing services. Also, Epios aims to implement a mobile application that will be used to acquire and submit the testing kits to and from the testers in an anonymous way. The project also aims to share COVID-19-related data with researchers, the government, and authorities, such as an individual’s COVID-19 result and outbreak statistics, while ensuring that an individual’s credentials are not disclosed [138–140].

Handling fake infodemic

The COVID-19 outbreak has uncovered the dire need for a reliable, timely, secure, trusted, transparent, and privacy-preserving system that should resolve the issues of existing ad-hoc, siloed, and non-scalable systems for combating the COVID-19 pandemic. The verifiability of COVID-19-related data can profoundly impact decision-making (city lockdown) across several industries worldwide. MiPasa is a multi-source and multi participant-based platform that employs blockchain technology to integrate, process, and share information related to the COVID-19 virus spreading from multiple verifiable sources, such as the WHO and registered health organizations and authorities. It helps authorities or governments identify both human errors and misreporting, thereby enabling data scientists and public health officials to devise solutions to limit the spread of the virus. For instance, employing data analytics on trusted and verified blockchain-based data, MiPasa backed by various analytic tools can assist state organizations in identifying COVID-19 carriers and infection hotspots in a private, secure, and timely manner. It provides the infrastructure that displays the anonymous identities of users who share COVID-19-related data, protecting users’ personally identifiable information (PII). By design, MiPasa is a fully private system that is implemented on top of IBM’s enterprise-grade Hyperledger Fabric platform. Through web-based interfaces, individuals and public health representatives can use MiPasa to upload the location of the infected person. In response, it validates it using data provided by WHO and the ECDC to assure that the new data matches the original. In the next stage, the new verified data is shared with the state authorities and health institutions that are designated by the countries [35, 140–143]. MiPasa presents real-time data related to COVID-19, such as new cases, cumulative cases, new deaths, cumulative deaths, and testing samples in different countries. The data presented by MiPasa is mainly taken from diverse sources such as WHO, the University of Oxford, country officials, and the CDC, to name a few.

Global anonymous contact-tracing platforms

Digital contact tracing aims to limit the spreading of airborne infectious viruses such as COVID-19. Leveraging digital contact tracing for identifying infection hotspots through the location of people can affect the user’s privacy. Contact tracing solutions’ and deployment platforms’ technological differences can have an impact on the adaptability and effectiveness of digital contact tracing solutions. The adaptability of contact tracing solutions is also affected by organizational privacy policies and applicable healthcare data regulations. Based on private blockchain technology, VIRI is aimed at filling this research gap by proposing a universal platform on a global scale while preserving users’ data privacy. Developing a cross-entity platform using VIRI to track the spread of the virus in different countries can help identify the COVID-19 outbreak in different places. VIRI’s platform for digital contact tracing ensures user data privacy [144]. It notifies the individuals when they make close contact with an infected person by anonymously tracking a randomly generated user identity. Later on, the individual can be alerted about infectious diseases based on the level of risk. For instance, after crossing paths with infected people, VIRI can change the status of an individual from a "clear case" to a "potentially infected case." Through open APIs, the VIRI platform can be seamlessly integrated with existing enterprise solutions. Thus, enabling the blockchain-based storage of data is anonymous (for privacy preservation), and it can assist machine learning and other AI-based tools to predict the COVID-19 pandemic globally [140, 145, 146].

Data privacy assurance

WIShelter is based on the WiseID application, which is Wisekey’s digital identity platform for providing security services to its users. WiseID is a digital identity solution on the blockchain that can assist organizations in curbing the spread of COVID-19. WIShelter is a smartphone-based application that stores the health data of individuals on the WiseID blockchain in a reliable and trusted manner. The records of the health data include many essential medical specimens, such as allergies, blood pressure, and many other pharmaceutical details. WIShelter aims to facilitate users’ seamless uploading of their digital certificates indicating the results of the COVID-19 test on the blockchain platform [140, 147, 148]. Through WIShelter, the uploaded COVID-19 test results of an individual can be accessed and verified by authorized government officials to issue travel permits to the individual who is willing to travel. However, failing to protect the privacy of users’ data (COVID-19 test results) can result in a variety of problems related to mistreatment and discrimination against infected people. To handle such a situation, WIShelter guarantees that the data of the users cannot be shared with others without their consent. The consent form can be duly signed by the data owner and users, and it could be transparently stored on the blockchain for accountability and audit purposes. Moreover, to secure the medical records and data communication, WIShelter encrypts the user data. Encrypting data also assures the preservation of data privacy, as stated in GDPR. WIShelter can assist authorities in verifying compliance with the stay-at-home policies designed by the authorities for COVID-19-infected patients [147–149]. Organizations and healthcare incubator platforms such as VirusIQ have already started using the WIShelter application for secure digital health screening and diagnostic services.

Remote healthcare monitoring systems

Telemedicine is one way to prevent the spread of carnivores through remote patient monitoring. An Ethereum and Hyperledger Fabric-based platform called Medicalchain has been used to implement remote services related to patient-to-doctor consultancy and marketplace applications. Hyperledger Fabric controls access to health records, whereas the ERC20 token on the Ethereum platform assists the health industry to implement services such as patient-to-doctor consulting. It ensures that health data transfers between patients and doctors are secure and private. Through marketplace applications, Medicalchain enables the owner of health data (the patient) to privately share the data with third parties (researchers) based on an agreed-upon consent form [124]. Many healthcare specialists have already registered on the medicalchain platform to offer telehealth services to patients. Another platform called HealPoint enables patients to get a second opinion on their health from a remote doctor. HealPoint is aiming to use the Ethereum platform to implement telehealth services. With the help of Ethereum smart contracts, patients can use the Schelling-coin algorithm (SchCoin) to find the best doctors for them [150]. The Ethereum-based smart contracts can further regulate patients’ and doctors’ interactions, the onboarding process for doctors, and the general consensus of doctors on the health of a patient to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis. Moreover, it can automatically recommend appropriate physicians based on artificial intelligence-based systems using factors such as location, experience, and conflict of interest [151]. Healpoint is in its infant stage, and it aims to use a consortium blockchain platform for health data sharing for research. The Proof of Authority (PoA) protocol will be used by the validators to verify and validate the transactions.

Self-sovereign identity management

The E-Rezept prototype presents a remote healthcare system that is based on the principle of self-sovereign identity (SSI). It enables patients to remotely place an order for medicines by presenting their unique identifiers as proof [140, 152]. To provide telemedicine services to citizens, the E-Rezept used cloud agent infrastructure, smartphone wallets, and an Ethereum blockchain platform. E-Rezept is flexible, and it can be successfully integrated with other SSI solutions such as Hyperledger Indy compared to legacy systems. COVI-ID is a blockchain-based startup that followed a permissioned self-sovereign identity (SSI) network called Sovrin [153] to digitize the contact tracing of people within an organization. The COVI-ID system gives rewards to law-abiding citizens in an accountable and transparent manner [140]. COVI-ID is free and can be used in small businesses such as office parks, restaurants, airports, and retailers. VeChain is a blockchain-based platform that supports real-time monitoring of vaccine development. VeChain is hosted on a public blockchain platform known as VeChainThor. It offers two tokens called vechain token (VET) and vechainthor energy (VTHO). VET is the VeChain token that is used for financial transactions, whereas VTHO represents the total cost of transacting on the blockchain. The vechainthor blockchain platform follows the PoA consensus algorithm for verifying the transactions. It assures that the data related to vaccine development and other details such as materials and codes for packaging are immutable and dependable [140, 154].

COVID-19 data visualization

Hashlog is a blockchain-based system that assisted citizens in tracking, visualizing, and predicting the COVID-19 outbreak. The Hashlog system interacts with the Hedera Hashgraph blockchain platform to provide such data (in real-time) about the COVID-19 outbreak. Hedera Hashgraph is a public blockchain platform that presents a single source of truth about COVID-19 data (Hashlog feature). Hashlog offers open-source web-based APIs that access COVID-19 data released by the WHO and the US center for disease control (USCDC) and store it on the ledger. The Hedera Hashgraph blockchain, on which the Hashlog system has been implemented, can transparently conduct audit trials of the data to verify the accuracy of COVID-19-related data. The coronavirus Hashlog dashboard can assist researchers and scientists to predict COVID-19 confirmed cases, deaths per hundred infections, and virus spreading trends in different regions [140, 155]. RebuildTheChain is another blockchain-based system that is implemented on the blockchain platform and preserves the privacy of the user’s data (geolocation). Citizens’ geolocation data allows the government to issue health cards based on an analysis of their recent visits and interactions with people in various locations. A health card represents the health status of a citizen. RebuildTheChain provides data in real-time about potential COVID-19 cases, virus hotspots, and the status of people under government isolation. The analysis of such records aids government officials in enforcing partial lockdowns to halt the spread of COVID-19. The mobile application interface of the RebuildTheChain system sends warning alerts to citizens when they enter a high-risk zone (a 50-meter geofence) [156].

Open research challenges

This section briefly discusses important open research challenges along with their key causes that hinder the adoption of blockchain for COVID-19 relief. The purpose is to provide guidelines and directions to new researchers aiming to develop immediate blockchain-based solutions to battle COVID-19.

Cross-platforms communication capabilities

The capacity to exchange data, information, and digital assets between different blockchain systems is known as cross-platform communication. Because of the inherent diversity of each platform, it’s likely that the two blockchains will operate under slightly different protocols and administrations. Using a "bridge" formed by an intermediate chain, they are able to exchange data and information securely [157]. Blockchain technology can greatly improve the supply chain of PPE and vaccines by (a) allowing faster and more transparent shipment of COVID-19 prevention materials, (b) enhancing the traceability of shipping materials, and (c) increasing trust among participating organizations by presenting a single and synchronized view of shipment data. It presents a cooperative, accountable, and collaborative environment among the participating organizations, including authorities, the government, hospitals, and research institutes, to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The blockchain interoperability feature allows disparate blockchain-based systems to uninterruptedly communicate with each other [28, 158]. It enables users to see, share, and access information across several blockchain platforms without requiring intermediary assistance (for translation services). Thus, the blockchain platform’s interoperability support can increase the throughput, safety, and productivity of a system. It also enables a user-friendly experience among multiple users, presents a contactless and easier smart contract execution environment, provides the opportunity to develop partnerships among participating organizations, and allows smooth sharing of information [158–160]. For instance, through interoperability-supported blockchain platforms, a user can perform business transactions using Bitcoin tokens on the Ethereum blockchain network. However, the diversity in technologies and differences in software designs of existing blockchain platforms are the major challenges to creating an interoperable blockchain-based system [158, 160]. The disparity in supported languages, data and transaction security in smart contracts, and recommended consensus protocols makes it difficult to propose solutions that support generalized interoperability. Moreover, an interoperable platform that hosts services for organizations that are combating the COVID-19 pandemic should provide high security, fault tolerance, and fast transaction processing.

Smart contracts security audit