Abstract

The biosynthesis of complex natural products in bacteria is invariably encoded within large gene clusters. Although this facilitates the cloning of such gene clusters, their heterologous expression in genetically amenable hosts remains a challenging problem, principally due to the difficulties associated with manipulating large DNA fragments. Here we describe a new method for the directed transfer of a gene cluster from one Streptomyces species to another. The method takes advantage of tra gene-mediated conjugal transfer of chromosomal DNA between actinomycetes. As proof of principle, we demonstrate transfer of the entire ∼22-kb actinorhodin gene cluster, and also the high-frequency cotransfer of two loci that are 150 to 200 kb apart, from Streptomyces coelicolor to an engineered derivative of Streptomyces lividans.

The actinomycetes are gram-positive bacteria that produce more than two-thirds of the known biologically active microbial natural products, including many commercially important antibiotics, anticancer agents, other pharmacologically useful agents, animal health products, and agrochemicals. Since most producer strains of actinomycetes lack adequate genetic tools, genetic dissection and manipulation of biosynthetic pathways in these organisms constitute a challenging problem. In such situations, functional expression of the biosynthetic genes in a genetically amenable heterologous host is becoming an increasingly attractive option. In particular, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) and its close relative Streptomyces lividans 66 have proven to be extremely useful hosts for the expression of polyketide, nonribosomal peptide, and deoxysugar biosynthetic gene clusters (reviewed in reference 7). Notwithstanding the growing repertoire of engineered hosts, vectors, promoters, and related tools for heterologous expression, the applicability of this approach is seriously limited in the case of large biosynthetic gene clusters that span >40 kb (i.e., the size limit for cosmid cloning) and encode many enzymes. Therefore, the development of simple methods for the lateral transfer of such biosynthetic pathways is of considerable importance to facilitate fundamental and biotechnological research objectives.

Here we describe a new method for the directed transfer of a gene cluster from one Streptomyces species to another. The method does not depend upon the availability of DNA sequence for the entire gene cluster, nor does it require the development of advanced genetic tools and methodology in the producing (donor) organism. It can be used to transfer large (>100-kb) chromosomal segments from one organism to another without the need for isolation or manipulation of these DNA fragments in vitro. As proof of principle, we demonstrate transfer of the entire ∼22-kb actinorhodin gene cluster, and also the high-frequency cotransfer of two loci that are 150 to 200 kb apart, from S. coelicolor to S. lividans.

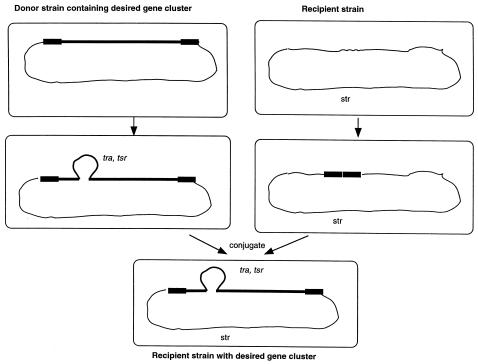

The method takes advantage of the phenomenon of plasmid-mediated conjugal transfer of chromosomal DNA between actinomycetes. Unlike the conjugal transfer of DNA in enteric bacteria, plasmid transfer in Streptomyces does not require a large number of plasmid-encoded gene products. For example, pIJ101, an 8.8-kb broad-host-range plasmid, not only can transfer itself to plasmidless bacteria at an efficiency approaching 100% but also can promote efficient transfer and recombination between chromosomal genes of mating bacteria (13) under the control of a single gene for intermycelial transfer (10). Indeed, the single tra gene of pIJ101 can be integrated into a donor chromosome to catalyze the transfer of chromosomal DNA to a recipient strain at high frequency (14). Similar experiments on the conjugative plasmid SCP2* have indicated that plasmid transfer is mediated by only a small number of genes (2). When SCP2* carried an insert of chromosomal DNA, it could mobilize markers on either side of the homologous region of the host chromosome, presumably following integration into the chromosome by generalized recombination (9). We therefore wished to investigate whether the chromosome mobilization ability of conjugative plasmids could be exploited for the directed transfer of large DNA fragments from one Streptomyces strain into another, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Directed interspecies transfer of a biosynthetic gene cluster. The chromosomes of a donor strain, which contains a biosynthetic gene cluster of interest (bold line), and a suitably marked (Strr) recipient strain are shown at the top. The pIJ101 tra gene is inserted into a “silent” position within or near the gene cluster in the donor genome, together with a selectable marker (tsr for thiostrepton resistance) (middle left). Meanwhile, homology fragments flanking the target gene cluster are inserted into the genome of the recipient strain via a suicide delivery vector or a site-specific integrative plasmid (middle right). The tra gene mediates bidirectional conjugal transfer of the gene cluster from the donor to the recipient strain. Homologous recombination results in stable integration of the entire gene cluster into the recipient chromosome at the desired locus (bottom).

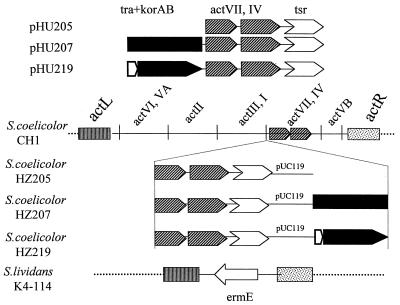

To test the hypothesis, we constructed plasmid pHU207, a derivative of the Escherichia coli plasmid pUC119 which contains a 3.0-kb fragment containing the actI-ORF3-actVII-actIV segment of the actinorhodin gene cluster (5), flanked by a korAB-tra cassette from pIJ101 (10) on one side and the tsr thiostrepton resistance gene on the other (Fig. 2). A control plasmid, pHU205, was constructed that was similar to pHU207 but lacked the korAB-tra cassette. pHU205 was generated by ligating the XbaI-EcoRI fragment from pIJ5639 (12) and a PstI-EcoRI cassette containing the tsr gene (8) with XbaI- and PstI-digested pUC119. pHU207 was constructed by ligating a 3.0-kb BamHI fragment from pGSP242 (14) to BamHI-digested pHU205. S. coelicolor CH1 (proA1 redE60 SCP1− SCP2−) (11) was transformed with pHU207 and pHU205, giving rise to thiostrepton-resistant strains HZ207 (in which the act gene cluster was marked with tsr and the korAB-tra cassette) and HZ205 (in which the act gene cluster was marked with the tsr gene), respectively. Both strains, which still retained the blue phenotype (due to actinorhodin production [3]) of the parent, were tested as donor strains in a conjugal-transfer experiment. The recipient strain in each case was S. lividans K4-114, a derivative of TK24 (Strr) in which the entire actinorhodin gene cluster has been “surgically” deleted by homologous recombination and replaced with the ermE gene (16). Approximately 5 × 106 spores of one or the other donor strain were mixed with a 10-fold excess of the recipient and plated as a lawn on R2YE agar medium (8). After incubation for 8 days at 30°C, spores from the lawn were harvested and plated on R2YE medium containing thiostrepton, streptomycin, or thiostrepton plus streptomycin at various dilutions. The efficiency of transfer of the actinorhodin gene cluster from S. coelicolor to S. lividans, measured as the fraction of Strr colonies that were also Thior, was 10−5, 10−5, 10−7, and 10−5 in four independent experiments performed on HZ207. No Thior Strr colonies were detected in the case of HZ205 (limit of detection, 10−8). The conjugation frequency for HZ219 was 10−3. Notably, as expected, all Thior Strr colonies obtained in the experiment involving HZ207 produced the blue pigment indicative of actinorhodin biosynthesis. Likewise, all these colonies were sensitive to lincomycin, indicating that they had lost the ermE marker that replaced the act cluster in the recipient strain. This experiment suggested that tra-mediated conjugal transfer of large gene clusters (the size of the actinorhodin gene cluster is ca. 22 kb) is feasible.

FIG. 2.

Conjugal transfer of the entire actinorhodin gene cluster from S. coelicolor to an engineered derivative of S. lividans. The inserts of three pUC119-based suicide plasmids, pHU205, pHU207, and pHU219, are shown at the top. pHU205 lacks the tra-korAB region of pIJ101 but contains the actVII-actIV integration site and the tsr (thiostrepton resistance) marker. pHU207 is a derivative of pHU205 that also includes the tra-korAB genes in their natural relative orientations and under the control of their native promoters. pHU219 is similar to pHU207, except that it contains the tra-korAB genes fused to the strong, constitutive PermE* promoter. The plasmids were integrated into the genome of S. coelicolor CH1, giving rise to strains HZ205, HZ207, and HZ219, respectively (shown below). The results of mating these strains with S. lividans K4-114 (bottom), from which the entire act gene cluster has been surgically deleted, are described in the text. actL and actR are sequences to the left and right, respectively, of the cluster of act genes in S. coelicolor CH1 (the act regions are not drawn to scale).

To confirm that the above-described phenomenon depends upon the expression of the tra gene in the donor strain, pHU219 was constructed (Fig. 2), which is identical to pHU207 except that the korAB-tra cassette is replaced with a PermE*-tra fusion. Construction of pHU219 involved ligation of the NruI-BamHI fragment containing the tra gene from pGSP242 (14) with the PstI (blunt)-BglII PermE* cassette from pELE37 (6), followed by insertion of this promoter fusion as an NheI-XbaI fragment into the XbaI site of pHU205 (performed in multiple steps). The PermE* promoter (1) is a strong constitutive promoter; hence, the tra gene is expected to be expressed at a higher level from this plasmid than from pHU207. A new donor strain, HZ219 (Fig. 2), was constructed by transforming S. coelicolor CH1 with pHU219 and selecting with thiostrepton for a stable integrant in the act gene cluster. S. coelicolor HZ219, like HZ205 and HZ207, produced blue pigment. HZ219 (as the donor) was crossed with the recipient (K4-114) under the same conditions as described above. The efficiency of transfer of the actinorhodin gene cluster from S. coelicolor to S. lividans, measured as before, increased substantially, from 10−5 to 10−3, in the presence of the PermE*-tra fusion.

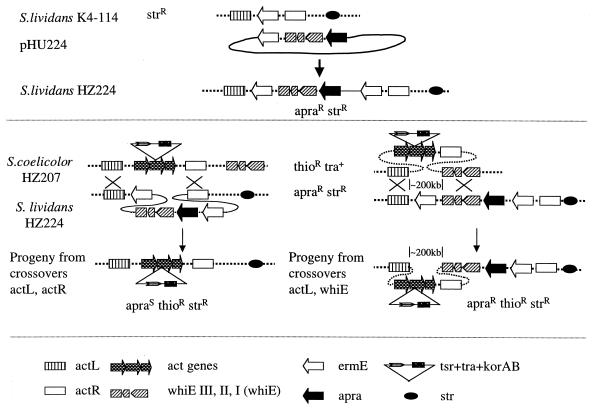

To assess the ability of the tra gene to mediate conjugal transfer of larger segments of chromosomal DNA, we attempted to estimate the frequency at which the act and the whiE (4, 15) loci (150 to 200 kb apart) were cotransferred from S. coelicolor to S. lividans. For this purpose, a derivative of K4-114 was constructed in which a 5.2-kb cassette, comprised of the whiE locus from S. coelicolor and the apr apramycin resistance marker gene, was integrated into the ermE gene in S. lividans K4-114 to produce strain HZ224 (Fig. 3, top). To construct HZ224, a plasmid pHU224 was generated via the following steps: (i) the SphI-MluI (blunt) fragment of pIJ2156 (4) was ligated with SphI and XbaI (blunt)-digested pIJ5606 (11) to yield pHU221, and (ii) the SphI-EcoRI fragment of pHU221 was cloned into SphI- and EcoRI-digested pHU214 to yield pHU224. pHU224 was integrated into the chromosome of S. lividans K4-114 by homologous recombination to yield strain HZ224. Since S. lividans also possesses a whiE locus, integration of pHU224 at the ermE site, and not the whiE site, by homologous recombination was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization. HZ207 (donor) was then mated with HZ224 (recipient) as shown in the lower part of Fig. 3. It was anticipated that Thior Strr Act+ exconjugants could be obtained in two ways. If only the act gene cluster was transferred into the recipient genome, the exconjugant would be sensitive to apramycin (left side of Fig. 3). On the other hand, if the act and the whiE gene clusters were cotransferred from the donor genome to the recipient genome, then the exconjugant would be apramycin resistant (right side of Fig. 3). Two independent conjugation experiments were performed with HZ207/HZ224 spore ratios of 1:5 and 1:250. The fractions of Thior Strr Act+ colonies that were also Aprr were 24 and 4%, respectively. (In both experiments, more than 1,000 Thior Strr Act+ colonies were scored.) This result suggests that the frequency of transfer of a large segment of genomic DNA is appreciable.

FIG. 3.

Conjugal transfer of the act-whiE segment (150 to 200 kb) from S. coelicolor to S. lividans. The construction of a recipient strain, S. lividans HZ224, is shown at the top. HZ224 was derived by integration of the suicide plasmid pHU224 into the ermE gene of S. lividans K4-114. HZ224 was crossed with S. coelicolor HZ207 (Fig. 2). Two possible outcomes were expected, as shown in the middle panel. On the left is the scenario in which only the act gene cluster (ca. 22 kb) is transferred and integrated, via conjugation and homologous recombination, from HZ207 to HZ224. These exconjugants should be Act+ Thior but Apras. On the right is the scenario in which the entire segment of the chromosome between the act and whiE gene clusters (ca. 200 kb) is transferred from HZ207 to HZ224. These exconjugants should be Act+ Thior Aprar. The symbols are defined in the bottom panel. (Recombinants sensitive to both apramycin and thiostrepton but resistant to streptomycin were not tested for.)

Together, the above-described experiments demonstrate considerable potential for conjugational transfer of gene clusters between different Streptomyces species using the pIJ101 tra gene. Similar methods using transfer elements from other actinomycete plasmids may also be practical.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA77248) to C.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bibb M J, Janssen G R, Ward J M. Cloning and analysis of the promoter region of the erythromycin resistance gene (ermE) of Streptomyces erythraeus. Gene. 1985;38:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brolle D F, Pape H, Hopwood D A, Kieser T. Analysis of the transfer region of the Streptomyces plasmid SCP2. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:157–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bystrykh L V, Fernández-Moreno M A, Herrema J K, Malpartida F, Hopwood D A, Dijkhuizen L. Production of actinorhodin-related “blue pigments” by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2238–2244. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2238-2244.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis N K, Chater K F. Spore colour in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) involves the developmentally regulated synthesis of a compound biosynthetically related to polyketide antibiotics. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1679–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-Moreno M A, Martínez E, Boto L, Hopwood D A, Malpartida F. Nucleotide sequence and deduced functions of a set of cotranscribed genes of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) including the polyketide synthase for the antibiotic actinorhodin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19278–19290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gramajo H C, White J, Hutchinson C R, Bibb M J. Overproduction and localization of components of the polyketide synthase of Streptomyces glaucescens involved in the production of the antibiotic tetracenomycin C. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6475–6483. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6475-6483.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopwood D A. Forty years of genetics with Streptomyces: from in vivo through in vitro to in silico. Microbiology. 1999;145:2183–2202. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopwood D A, Lydiate D J, Malpartida F, Wright H M. Conjugative sex plasmids of Streptomyces. In: Helinski D R, Cohen S N, Clewell D B, Jackson D B, Hollaender A, editors. Plasmids in bacteria. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1985. pp. 615–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall K J, Cohen S N. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Streptomyces lividans plasmid pIJ101 and correlation of the sequence with genetic properties. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4634–4651. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4634-4651.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosla C, Ebert-Khosla S, Hopwood D A. Targeted gene replacements in a Streptomyces polyketide synthase gene cluster; role for the acyl carrier protein. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3237–3249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khosla C, McDaniel R, Ebert-Khosla S, Torres R, Sherman D H, Bibb M J, Hopwood D A. Genetic construction and functional analysis of hybrid polyketide synthases containing heterologous acyl carrier proteins. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2197–2204. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2197-2204.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kieser T, Hopwood D A, Wright H M, Thompson C J. pIJ101, a multi-copy broad host-range Streptomyces plasmid: functional analysis and development of DNA cloning vectors. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;185:223–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00330791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettis G S, Cohen S N. Transfer of the pIJ101 plasmid in Streptomyces lividans requires a cis-acting function dispensable for chromosomal gene transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:955–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu T W, Hopwood D A. Ectopic expression of the Streptomyces coelicolor whiE genes for polyketide spore pigment synthesis and their interaction with the act genes for actinorhodin biosynthesis. Microbiology. 1995;141:2779–2791. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-11-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziermann R, Betlach M C. Recombinant polyketide synthesis in Streptomyces: engineering of improved host strains. BioTechniques. 1999;26:106–110. doi: 10.2144/99261st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]