Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effectiveness of XEN45, either alone or in combination with phacoemulsification, in open-angle glaucoma (OAG) patients in clinical practice.

Methods

Retrospective and single-center study conducted on OAG patients who underwent XEN45 implant, either alone or in combination with cataract surgery. We compared the clinical outcomes of the eyes of thosewho underwent XEN-solo versus those who underwent XEN+Phacoemulsification. The primary endpoint was the mean change in intraocular pressure (IOP) from baseline to the last follow-up visit.

Results

A total of 154 eyes, 37 (24.0%) eyes that underwent XEN-solo and 117 (76.0%) eyes that underwent XEN+Phacoemulsification, were included. The mean preoperative IOP was significantly lowered from 19.1±5.0 mmHg to 14.9±3.8 mmHg at month-36, p<0.0001. Preoperative IOP was significantly lowered from 21.2±6.2 mmHg and 18.4±4.3 mmHg to 14.3±4.0 mm Hg and 15.2±3.7 mmHg at month-36 in the XEN-solo and XEN+Phacoemulsification groups, p<0.0004 and p=0.0009; with no significant differences between them. In the overall study population, the mean number of antiglaucoma medications was significantly reduced from 2.1±0.8 to 0.2±0.6, p<0.0001. There were no significant differences in the proportion of eyes with a final IOP ≤14 mmHg and ≤16 mmHg between XEN-solo and XEN+Phaco groups (p=0.8406 and 0.04970, respectively). Thirty-six (23.4%) eyes required a needling procedure.

Conclusion

XEN implant significantly lowered IOP and reduced the need of ocular hypotensive medication, while maintaining a good safety profile. Beyond week-1, there were no significant differences in IOP lowering between XEN-solo and XEN+Phacoemulsification groups.

Keywords: open-angle glaucoma, MIGS, XEN45, intraocular pressure, learning-curve

Introduction

Glaucoma is a chronic and progressive disease that requires treatment throughout the patient’s lifetime.1 Lowering intraocular pressure (IOP) is currently considered the main known modifiable risk factor.2

Although topical hypotensive medication is currently considered the first treatment-approach in most patients, not all the patients achieve adequate glaucoma control.3,4

Due mainly to its well-stablished IOP-lowering effect, trabeculectomy is currently considered the gold-standard in glaucoma surgery.5 However, it may lead to potential vision-threatening complications.6

Glaucoma surgery has experienced important advances over the last several years. Among them, minimally or microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) devices have been developed as safer and less traumatic means of lowering IOP in patients with glaucoma.7

The criteria for defining a MIGS device have been somewhat controversial,8,9 and the generally accepted definition of MIGS has been modified over the years.10 Although according to the classical definition there is some debate about considering the XEN device as a MIGS,8 for the purposes of this document, the term MIGS will apply to it.

Different studies have evaluated the efficacy and safety of XEN45 implant in clinical practice showing its good effectiveness profile.11–21

However, none of them have evaluated the impact of the changes introduced in the technique from its development. XEN45 has usually been delivered using an ab-interno approach through a corneal incision.11–21 However, as surgeons have been gaining experience with the device, different changes, which aim to provide better clinical outcomes, have been introduced in the implantation technique.22–24 In addition, the information about the long-term effect of XEN45 device is limited, with only few papers evaluating its effectiveness beyond 24 months.17,25–29 Moreover, the question of whether there are any differences in IOP lowering or reduction of ocular hypotensive medications between XEN alone or in combination with phacoemulsification in the long-term remain.

The main objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness over a period of 36-months, in terms of IOP lowering and reduction of ocular hypotensive medications, of XEN45 implant, either alone or in combination with phacoemulsification, in OAG patients in clinical practice.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Retrospective and single-center study conducted in OAG patients who underwent XEN 45 gel-stent implant, either alone or in combination with cataract surgery, between June 2016 and December 2019.

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients signed a written general consent to participate in studies, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Alicante General University Hospital. The Ethics Committee waived the need for written informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. Any information that could lead to an individual being identified has been encrypted or removed, as appropriate, to guarantee their anonymity.

A preprint has previously been published.30

Patients ≥18 years old with insufficiently medically controlled early to advanced OAG, according to Hodapp et al,31 intolerance to topical hypotensive treatments; or poor treatment adherence, who underwent XEN45 implantation, either alone or in combination with cataract surgery, were included in the study.

Patients having a diagnosis of secondary glaucoma; presenting with active ocular inflammation or conjunctival alterations; or having a history of intolerance or allergic reaction to glutaraldehyde or porcine derivatives were excluded from the study.

Surgical Technique

All the surgical procedures were performed, under local anesthesia, by the same surgeon (MTMP). XEN implant was placed in the superior nasal quadrant using a standard ab-interno technique following a previously described technique.15 Intraoperatively, a 27-gauge hypodermic needle was used to inject 0.1 mL of mitomycin-C (MMC) 0.01% subconjunctivally under the Tenon capsule.

Study Groups

The study sample was divided into two different groups: XEN-solo, eyes that underwent XEN implant alone; XEN+Phaco, eyes that underwent combined surgery (XEN + phacoemulsification).

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the mean change in IOP from baseline to the last follow-up visit.

Secondary end-points included mean IOP at the last follow-up visit; the mean number of antiglaucoma medications and its changes from baseline; proportion of patients classified as success; proportion of patients achieving at the last follow-up visit IOP ≤21 mmHg; IOP ≤18 mmHg; IOP ≤16 mmHg; and ≤14 mmHg, irrespective of the % reduction; predictive factors associated with success; and incidence of adverse events.

Definitions

Surgical success was defined as achieving a 20% reduction in IOP respective to preoperative value together with an IOP absolute value between 6 and 21 mmHg, without (Complete success) or with (Qualified success) antiglaucoma medications.

Patients with an IOP <6 mmHg for more than two consecutive visits, those who needed further glaucoma surgery, or those who had surgery for complications were also considered a failure.

Statistical Analysis

A standard statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 20.211 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2023).

Descriptive statistics number (percentage), mean [standard deviation (SD)], mean [95% confidence interval (95% CI)], mean [standard error (SE)], median (interquartile range), or median (95% CI) were used, as appropriate.

Data were tested for normal distribution using a D’Agostino–Pearson test.

A repeated measures ANOVA or a Friedman’s two-way analysis test, as appropriate, were used to assess the changes in IOP and in number of antiglaucoma medications. Post hoc analysis for pairwise comparisons was done with the Scheffé’s method (ANOVA) or the Conover method (Friedman).

Repeated analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed to assess the changes in IOP between study groups. The model included “type of surgery” (XEN alone or XEN+Phaco) as a factor and age, preoperative IOP, and number of preoperative ocular hypotensive medications as covariates.

Success survival rates were plotted for XEN solo and XEN+Phaco groups using Kaplan–Meier analysis and were compared using a Log rank test.

To test for preoperative differences between cohorts, Mann–Whitney test was used for continuous variables.

Categorical variables were compared using a Chi-square test and a Fisher’s exact test, as needed. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 154 eyes (100 patients) were included in the study, 37 (24.0%) eyes that underwent XEN alone and 117 (76.0%) eyes that underwent combined surgery (XEN + phacoemulsification). In the overall study sample, the mean age was 72.1±8.9 years and 112 (74.7%) eyes were diagnosed with primary-OAG.

Table 1 shows the main clinical and demographic clinical characteristics of the study sample.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristic | Total Population (n=154) | XEN Solo (n=37) | XEN+Phaco (n=117) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 72.1 (8.9) | 69.6 (13.2) | 72.9 (9.7) | 0.4373a |

| 95% CI | 70.7–73.5 | 65.2–74.0 | 71.6–74.2 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 82 (53.2) | 20 (54.1) | 62 (53.0) | 1.0000b |

| Male | 72 (46.8) | 17 (45.9) | 55 (47.0) | |

| Eye, n (%) | ||||

| Right | 76 (49.4) | 14 (37.8) | 62 (53.0) | 0.1323b |

| Left | 78 (50.6) | 23 (62.2) | 55 (47.0) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%)c | ||||

| POAG | 112 (74.7) | 26 (72.2) | 86 (75.4) | 0.1194d |

| PEX | 22 (14.7) | 3 (8.3) | 19 (16.7) | |

| CNAG | 6 (4.0) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PIG | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.3) | |

| Other | 8 (5.3) | 5 (13.9) | 3 (2.6) | |

| IOP, mmHg; | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 19.1 (5.0) | 21.2 (6.2) | 18.4 (4.3) | 0.0112a |

| 95% CI | 18.3–19.9 | 19.2–23.3 | 17.6 to 19.2 | |

| NOHM | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.8) | <0.0001a |

| 95% CI | 1.9 to 2.2 | 2.3 to 2.8 | 1.8 to 2.0 | |

| NOHM, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 44 (28.6) | 2 (5.4) | 42 (35.9) | <0.0001d |

| 2 | 61 (39.6) | 14 (37.8) | 47 (40.2) | |

| 3 | 45 (29.2) | 19 (51.4) | 26 (22.2) | |

| 4 | 4 (2.6) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (1.7) |

Notes: aMann–Whitney test. bFisher’s exact test. cDiagnosis data were available for 150 eyes. dChi-squared test for trend.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; PEX, pseudoexfoliative glaucoma; CNAG, chronic narrow-angle glaucoma; PIG, pigmentary glaucoma; IOP, intraocular pressure; NOHM, number of ocular hypotensive medications; Phaco, phacoemulsification.

At the time of analysis, 114 eyes had data available up to 2 years after surgery and 63 eyes had data up to 3 years. Median (interquartile range) time of follow-up was 24.0 (24.0–24.0) months.

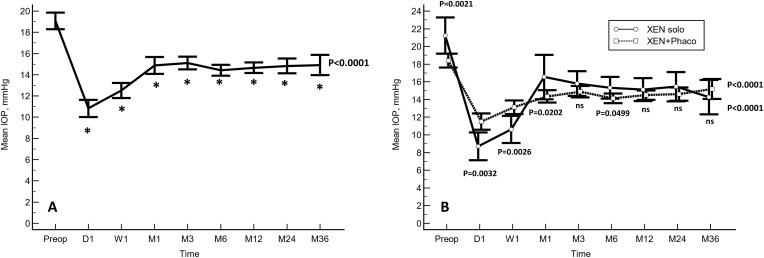

In the overall study population, the mean preoperative IOP was significantly lowered from 19.1±5.0 to 10.8±5.0, 12.5±4.5, 14.9±5.0, 15.1±3.7, 14.4±3.2, 14.7±3.1, 14.8±3.8, and 14.9±3.8 mmHg at day-1, week-1, months 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36, respectively; p<0.0001 each, respectively (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mean intraocular pressure (IOP) over the course of follow-up. The vertical bars represent the 95% confidence interval. (A) In the overall study population. (B) A comparison between the eyes that underwent XEN solo and those eyes that underwent XEN+Phacoemulsification surgery. Mean IOP was significantly lower in the XEN solo group at day 1 and week 1, but significantly greater at preoperative, months 1 and 6. No significant differences were observed at any of the other IOP time points measured (Statistical significance was determined using the one-way ANOVA test with the Scheffé’s method). *p < 0.0001 as compared to baseline (repeated measures ANOVA and the Greenhouse-Geisser correction).

Abbreviations: Preop, preoperative; D, Day; W, Week; M, Month; ns, not significant.

Preoperative IOP was significantly greater in those eyes that underwent XEN alone than in those who underwent combined surgery (21.2±6.2 mmHg vs 18.4±4.3 mmHg, p=0.0021). Mean IOP was significantly lower at day 1 and week 1 in the eyes that underwent XEN solo, but significantly greater at months 1 and 6. As compared to baseline, the IOP was significantly lowered in both groups (Figure 1B).

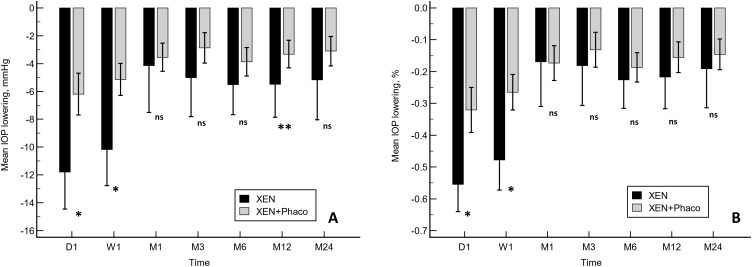

There were significant differences in IOP lowering between XEN and XEN+Phaco procedures at day 1, week 1 (absolute and percentage IOP lowering), and month-12 (absolute values) (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

A comparison of the mean IOP lowering from preoperative values in XEN and XEN+Phaco procedures. (A) Absolute values. (B) Percentage. *p<0.0001. **p<0.05. Statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney test.

Abbreviation: ns, Not significant.

After adjusting for age, preoperative IOP, and number of preoperative ocular hypotensive medications mean IOP lowering, both absolute and percentage terms, was significantly greater at day 1 and week 1 in the XEN-solo group. However, no significant differences were observed at any of the different time-point measured in both cohorts beyond (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Changes in Intraocular Pressure (IOP) Over the Course of Follow-Up in the Eyes That Underwent XEN Alone (XEN) versus Those That Underwent XEN + Phacoemulsification (XEN+Phaco)

| Mean Change in IOP, mm Hg | Absolute Values | ||||||

| XEN | XEN+Phaco | Difference | |||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | Pa | |

| Day 1 | −10.1 | 0.9 | −7.7 | 0.5 | −2.3 (1.1) | −4.5 to −0.4 | 0.0230 |

| Week 1 | −9.2 | 0.8 | −5.7 | 0.4 | −3.5 (0.9) | −5.3 to −1.8 | 0.0001 |

| Month 1 | −3.5 | 0.9 | −4.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 (1.0) | −1.1 to 2.9 | 0.3807 |

| Month 3 | −4.0 | 0.7 | −4.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 (0.8) | −1.6 to 1.5 | 0.9742 |

| Month 6 | −4.4 | 0.6 | −4.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 (0.7) | −1.0 to 1.6 | 0.6141 |

| Month 12 | −4.1 | 0.6 | −4.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 (0.7) | −1.1 to 1.5 | 0.7644 |

| Month 24 | −3.1 | 0.8 | −3.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 (0.9) | −2.5 to 1.1 | 0.4215 |

| Signification* | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | |||||

| Mean Change in IOP, mm Hg | Percentages | ||||||

| XEN | XEN+Phaco | Difference | |||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean (SE) | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Day 1 | −51.0 | 4.8 | −36.8 | 2.6 | −14.2 (5.7) | −25.5 to −3.0 | 0.0136 |

| Week 1 | −46.4 | 4.1 | −27.0 | 2.2 | −19.4 (4.9) | −29.0 to −9.8 | 0.0001 |

| Month 1 | −15.5 | 4.5 | −20.1 | 2.4 | 4.6 (5.3) | −5.8 to 15.0 | 0.3844 |

| Month 3 | −14.8 | 3.7 | −17.2 | 2.0 | 2.4 (4.4) | −6.2 to 11.0 | 0.5852 |

| Month 6 | −19.0 | 3.0 | −21.4 | 1.6 | 2.4 (3.5) | −4.7 to 9.4 | 0.5089 |

| Month 12 | −17.5 | 3.2 | −19.4 | 1.7 | 1.9 (3.7) | −5.5 to 9.3 | 0.6172 |

| Month 24 | −11.8 | 4.1 | −16.9 | 2.3 | 5.2 (4.9) | −4.5 to 14.8 | 0.2937 |

| Signification* | P<0.0001 | P<0.0001 | |||||

Notes: aBonferroni corrected. *Repeated measures ANCOVA and the Greenhouse–Geisser correction. bRepeated measures analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). The model included “Type of surgery” (XEN solo versus XEN+Phaco) as factor and age, preoperative IOP, and number of preoperative ocular hypotensive medications as covariates.

Abbreviations: IOP, intraocular pressure; SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

In the overall study population, the mean number of antiglaucoma medications was significantly reduced from 2.1±0.8 to 0.2±0.6, p<0.0001. The number of ocular hypotensive medications was significantly reduced in the XEN-alone (from 2.6±0.7 to 0.4±0.8, p<0.0001) and in the XEN+Phaco (from 1.9±0.8 to 0.2±0.5, p<0.0001) groups. The mean reduction of ocular hypotensive medications was significantly greater in the XEN-alone than in the XEN+Phaco group (mean difference: 0.4 drugs; 95% CI: 0.1 to 0.7; p=0.0134).

At the last follow-up visit, 83 (53.9%) eyes were classified as success, with 75 (48.7%) eyes classified as complete success.

Table 3 shows the proportion of eyes who achieved different IOP targets irrespective of the percentual reduction from baseline.

Table 3.

Overview of the Proportion of Patients Who Achieved Specific Intraocular Pressure Levels, with and Without Hypotensive Medication, at the Last Follow-Up Visit

| With/Without Treatment | Without Treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=154) | XEN (n=37) | XEN+Phaco (n=117) | p | Overall (n=154) | XEN (n=37) | XEN+Phaco (n=117) | p | |

| ≤14 mm Hg, n (%) | 73 (47.4) | 17 (46.0) | 56 (47.9) | 0.8406 | 68 (42.4) | 13 (35.1) | 55 (47.0) | 0.2053 |

| ≤16 mm Hg, n (%) | 111 (72.2) | 25 (67.6) | 86 (73.5) | 0.4970 | 101 (65.6) | 20 (54.1) | 81 (69.2) | 0.0931 |

| ≤18 mm Hg, n (%) | 135 (87.7) | 31 (83.8) | 104 (88.9) | 0.4123 | 123 (79.9) | 25 (67.6) | 98 (83.8) | 0.0326 |

| >18 mm Hg, n (%) | 19 (12.3) | 6 (16.2) | 13 (11.1) | 0.4123 | Not applicable | |||

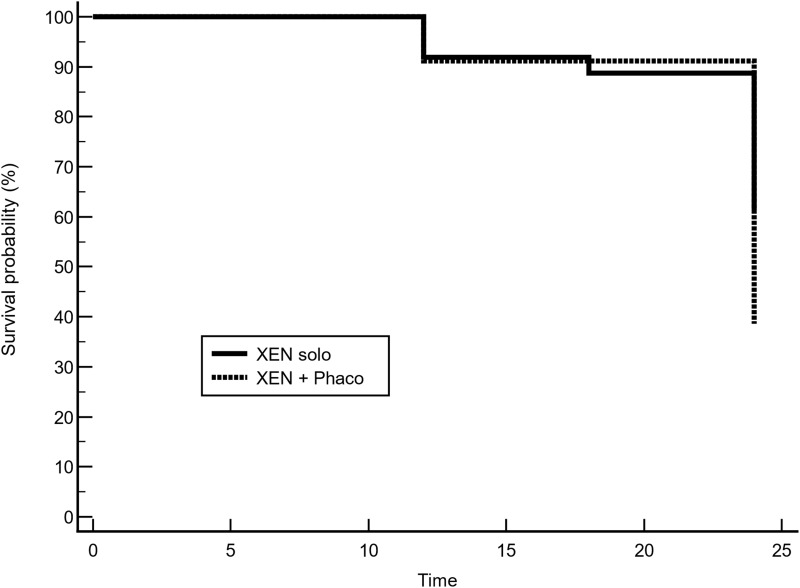

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis did not find any difference in the success rate between XEN-solo and XEN+PHACO groups (Mean hazard ratio: 1.97, 95% confidence interval 0.93 to 3.92; p = 0.0775) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for success. Success occurred in 67.6% (25/37) of eyes that underwent XEN-solo surgery, while success occurred in 49.6% (58/117) of eyes that underwent combined surgery (XEN+Phaco). Mean hazard ratio (HR) 1.97, 95% confidence interval (0.93 to 3.92); p = 0.0775.

The most frequent post-surgical complication in the overall study population was the need for needling (n = 36 eyes [23.4%]), followed by bleb fibrosis (n = 33 eyes [21.6%]), Tenon’s cyst (n = 21 eyes [13.6%]) and the need for surgical revision (n = 16 eyes [10.5%]) (Table 4). Except for the need for surgical revision, no significant differences were observed in the incidence of adverse events between eyes that underwent XEN-solo and those that underwent XEN+Phacoemulsification (Table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence of Post-Surgery Complications After XEN45 Implant Surgery

| Complication, n (%) | Total Population (n=154) | XEN solo (n=37) | XEN+Phaco (n=117) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needling | 36 (23.4) | 13 (35.1) | 23 (19.7) | 0.0546 |

| Bleb fibrosisb | 33 (21.6) | 11 (29.7) | 22 (19.0) | 0.1692 |

| Tenon’s cyst | 21 (13.6) | 8 (21.6) | 13 (11.1) | 0.1057 |

| Surgical revision | 16 (10.5) | 8 (21.6) | 8 (7.0) | 0.0119 |

| Hyphema | 8 (5.2) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (4.3) | 0.3663 |

| Anterior chamber flattening | 3 (1.9) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (0.9) | 0.0879 |

| Infectionb | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | na |

Notes: aChi-squared test. bBleb-related infection or endophthalmitis.

Abbreviations: n, number of eyes; na, not applicable.

Discussion

The results of the current study demonstrated that XEN45 implant, either alone or in combination with cataract surgery, significantly lowered the IOP and reduced the need for postoperative ocular hypotensive medication in patients with OAG in a real-life scenario.

The IOP lowering was significantly greater at day-1, week-1, and month-12 in the XEN-solo group than in the XEN+Phacoemulsification one.

Additionally, it should be highlighted the relatively high proportion of patients achieving low target IOPs, with 42.4% and 65.6% of the patients achieving an IOP ≤14 mm Hg and ≤16 mm Hg without treatment, respectively. The proportion of eyes who achieved an IOP ≤14 mmHg or IOP ≤16 mm Hg, both with and without treatment, were similar in both groups. However, the proportion of eyes who achieved an IOP ≤18 mmHg without treatment was significantly greater in the XEN+Phacoemulsification group.

From a clinical point of view, different studies have reported the mid- and long-term efficacy, in terms of IOP lowering and the amount of ocular-hypotensive medications reduction, and safety of XEN45 implant, either alone or in combination with phacoemulsification surgery, in OAG patients.14,16,17,25–29,32–38

In this respect, the results of the study do not differ significantly from the published evidence.

Our study found significant differences, throughout study follow-up, between the eyes that underwent XEN-alone and those eyes that underwent XEN+Phacoemulsification. However, such differences were not statistically significant after adjusting by different covariates.

Interestingly, these differences were not always in favor of the same group throughout follow-up. Preoperative IOP was significantly greater in the XEN-solo group, which can be justified by the fact that the surgery was indicated for purely hypotensive purposes.

The mean IOP was significantly lower in the XEN-solo group at day-1 and week-1, while it was significantly lower in the combined group at months 1 and 6. Nevertheless, in terms of percentage, there were no significant differences in IOP lowering between XEN-solo and XEN+Phacoemulsification beyond the week-1.

The effectiveness of XEN45 in combination with cataract surgery has been analyzed in some papers. However, there have been conflicting results regarding the superiority of the solo procedure over the combined procedure with cataract surgery.12,15,16,26,39

While some authors did not find significant differences in IOP lowering between XEN-alone and the XEN+Phacoemulsification groups,12,15,16 other ones reported higher success rates in the XEN-alone group.26,39

According to the results of Chen et al,40 both XEN-alone (mean difference: −7.8 mmHg; 95% CI: −8.21 to −7.38 mmHg, p<0.001) and XEN+Phacoemulsification (mean difference: −8.35 mmHg; 95% CI: −9.82 to −6.88 mmHg, p<0.001) significantly lowered the IOP. However, another systematic review and meta-analysis published by Wang et al38 has shown different results. They found better results for XEN alone compared XEN+Phacoemulsification procedures in IOP lowering but not in the reduction of ocular hypotensive medications.41

Regarding safety, the incidence and type of complications was similar to that previously published.11–21,25–29,32–39 Thirty-six (23.4%) eyes underwent a needling procedure and 16 (10.5%) eyes required a surgical revision. Apart from the incidence of surgical revision, which was significantly greater in the XEN solo group, no differences were observed between the two study groups.

The main limitation of the current study is its retrospective design. Selection bias and potential confounders are inherent to retrospective studies. Nevertheless, the selection of strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as the inclusion of a large number of eyes, may minimize these issues. In addition, the current study did not evaluate the endothelial cells count. It has been previously reported that XEN device in combination with phacoemulsification was associated with certain endothelial cell density reduction.42,43 Nevertheless, the endothelial cell density reduction was similar to that observed following standalone phacoemulsification.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that XEN implant, either alone or in combination with cataract surgery is an effective treatment for lowering IOP and reducing the need for ocular hypotensive medication, while maintaining a good safety profile.

Additionally, except for the day-1 and week-1, our study did not find significant differences in IOP lowering at any of the different time-point measured between XEN-solo and XEN+Phaco.

Doubts remain to be clarified, such as, for example, the role of mitomycin-C concentration on clinical results or the cost-effectiveness of this procedure.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and Editorial assistant services have been provided by Antonio Martínez (MD) of Ciencia y Deporte Ltd.

Funding Statement

Dr María Teresa Marcos-Parra has received a Grant from Allergan during the conduct of the study. The medical writer for this manuscript was supported by AbbVie with no input into the preparation, review, approval and writing of the manuscript. The authors maintained complete control over the manuscript content, and it reflects their opinions.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (MTMP) upon reasonable request.

Statement of Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Alicante general University Hospital, which waived the need for written informed consent of the participants for the study.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet. 2004;363:1711–1720. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16257-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M; Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(10):1268–1279. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, et al.; CIGTS Study Group. Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(11):1943–1953. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00873-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, et al. The most common barriers to glaucoma medication adherence: a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landers J, Martin K, Sarkies N, Bourne R, Watson P. A twenty-year follow-up study of trabeculectomy: risk factors and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jampel HD, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Lichter PR, Wright MM, Guire KE; Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study Group. Perioperative complications of trabeculectomy in the collaborative initial glaucoma treatment study (CIGTS). Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bar-David L, Blumenthal EZ. Evolution of glaucoma surgery in the last 25 years. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2018;9(3):e0024. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saheb H, Ahmed II. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(2):96–104. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff1e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed II. MIGS and the FDA: what’s in a name? Ophthalmology. 2015;122(9):1737–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caprioli J, Kim JH, Friedman DS, et al. Special commentary: supporting innovation for safe and effective minimally invasive glaucoma surgery: summary of a joint meeting of the American Glaucoma Society and the Food and Drug Administration, Washington, DC, February 26, 2014. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(9):1795–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover DS, Flynn WJ, Bashford KP, et al. Performance and safety of a new ab interno gelatin stent in refractory glaucoma at 12 months. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hengerer FH, Kohnen T, Mueller M, Conrad-Hengerer I. Ab interno gel implant for the treatment of glaucoma patients with or without prior glaucoma surgery: 1-year results. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(12):1130–1136. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlenker MB, Gulamhusein H, Conrad-Hengerer I, et al. Efficacy, safety, and risk factors for failure of standalone ab interno gelatin microstent implantation versus standalone trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitsamer H, Sng C, Vera V, Lenzhofer M, Barton K, Stalmans I; Apex Study Group. Two-year results of a multicenter study of the ab interno gelatin implant in medically uncontrolled primary open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(5):983–996. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04251-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcos Parra MT, Salinas López JA, López Grau NS, Ceausescu AM, Pérez JJ. XEN implant device versus trabeculectomy, either alone or in combination with phacoemulsification, in open-angle glaucoma patients. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;257(8):1741–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04341-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karimi A, Lindfield D, Turnbull A, et al. A multi-centre interventional case series of 259 ab-interno Xen gel implants for glaucoma, with and without combined cataract surgery. Eye. 2019;33(3):469–477. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0243-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenzhofer M, Kersten-Gomez I, Sheybani A, et al. Four-year results of a minimally invasive transscleral glaucoma gel stent implantation in a prospective multi-centre study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;47(5):581–587. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibáñez-Muñoz A, Soto-Biforcos VS, Rodríguez-Vicente L, et al. XEN implant in primary and secondary open-angle glaucoma: A12-month retrospective study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;30(5):1034–1041. doi: 10.1177/1120672119845226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fea AM, Bron AM, Economou MA, et al. European study of the efficacy of a cross-linked gel stent for the treatment of glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2020;46(3):441–450. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner FM, Schuster AK, Emmerich J, Chronopoulos P, Hoffmann EM. Efficacy and safety of XEN®-implantation vs. trabeculectomy: data of a “real-world” setting. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theilig T, Rehak M, Busch C, Bormann C, Schargus M, Unterlauft JD. Comparing the efficacy of trabeculectomy and XEN gel microstent implantation for the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma: a retrospective monocentric comparative cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19337. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76551-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panarelli JF, Yan DB, Francis B, Craven ER, Gel Stent XEN. Open conjunctiva technique: a practical approach paper. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):2538–2549. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01278-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vera V, Gagne S, Myers JS, Ahmed IIK. Surgical approaches for implanting xen gel stent without conjunctival dissection. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2361–2371. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S265695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan NE, Tracer N, Terraciano A, Parikh HA, Panarelli JF, Radcliffe NM. Comparison of safety and efficacy between Ab interno and Ab externo approaches to XEN gel stent placement. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:299–305. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S292007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reitsamer H, Vera V, Ruben S, et al. Three-year effectiveness and safety of the XEN gel stent as a solo procedure or in combination with phacoemulsification in open-angle glaucoma: a multicentre study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022;100(1):e233–e245. doi: 10.1111/aos.14886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillmann K, Bravetti GE, Rao HL, Mermoud A, Mansouri K. Combined and stand-alone XEN 45 gel stent implantation: 3-year outcomes and success predictors. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(4):e531–e539. doi: 10.1111/aos.14605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabbay IE, Goldberg M, Allen F, et al. Efficacy and safety data for the Ab interno XEN45 gel stent implant at 3 Years: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;11206721211014381. doi: 10.1177/11206721211014381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nuzzi R, Gremmo G, Toja F, Marolo P. A retrospective comparison of trabeculectomy, baerveldt glaucoma implant, and microinvasive glaucoma surgeries in a three-year follow-up. Semin Ophthalmol. 2021;36(8):839–849. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2021.1931356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cappelli F, Cutolo CA, Olivari S, et al. Trabeculectomy versus Xen gel implant for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma: a 3-year retrospective analysis. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022;7(1):e000830. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2021-000830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcos-Parra MT, Salinas-López JA, Mateos-Marcos C, Moreno-Castro L, Mendoza Moreira AL, Pérez-Santonja JJ. Long-term effectiveness of XEN 45 gel-stent in open-angle glaucoma patients. 2022. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1514143/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hodapp E, Parrish R, Anderson D. Clinical Decisions in Glaucoma. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabbay IE, Allen F, Morley C, Pearsall T, Bowes OM, Ruben S. Efficacy and safety data for the XEN45 implant at 2 years: a retrospective analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(8):1125–1130. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-313870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mansouri K, Bravetti GE, Gillmann K, Rao HL, Ch’ng TW, Mermoud A. Two-year outcomes of XEN gel stent surgery in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2019;2(5):309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheres LMJ, Kujovic-Aleksov S, Ramdas WD, et al. XEN® gel stent compared to PRESERFLO™ microshunt implantation for primary open-angle glaucoma: two-year results. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99(3):e433–e440. doi: 10.1111/aos.14602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subaşı S, Yüksel N, Özer F, Yılmaz Tugan B, Pirhan D. A retrospective analysis of safety and efficacy of XEN 45 microstent combined cataract surgery in open-angle glaucoma over 24 months. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2021;51(3):139–145. doi: 10.4274/tjo.galenos.2020.47629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wanichwecharungruang B, Ratprasatporn N. 24-month outcomes of XEN45 gel implant versus trabeculectomy in primary glaucoma. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0256362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicolaou S, Khatib TZ, Lin Z, et al. A retrospective review of XEN implant surgery: efficacy, safety and the effect of combined cataract surgery. Int Ophthalmol. 2022;42(3):881–889. doi: 10.1007/s10792-021-02069-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcos-Parra MT, Mendoza-Moreira AL, Moreno-Castro L, et al. 3-year outcomes of XEN implant compared with trabeculectomy, with or without phacoemulsification for open angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2022;31(10):826–833. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000002090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mansouri K, Guidotti J, Rao HL, et al. Prospective evaluation of standalone XEN gel implant and combined phacoemulsification-XEN gel implant surgery: 1-year results. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(2):140–147. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen XZ, Liang ZQ, Yang KY, et al. The outcomes of XEN gel stent implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2022;9:804847. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.804847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang B, Leng X, An X, Zhang X, Liu X, Lu X. XEN gel implant with or without phacoemulsification for glaucoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(20):1309. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-6354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillmann K, Bravetti GE, Rao HL, Mermoud A, Mansouri K. Impact of phacoemulsification combined with XEN gel stent implantation on corneal endothelial cell density: 2-year results. J Glaucoma. 2020;29(3):155–160. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oddone F, Roberti G, Posarelli C, et al. Endothelial cell density after XEN implant surgery: short-term data from the Italian XEN Glaucoma Treatment Registry (XEN-GTR). J Glaucoma. 2021;30(7):559–565. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (MTMP) upon reasonable request.