Highlights

-

•

Needs of mothers with OUD are best met by focusing on all dimensions of wellness.

-

•

A nonjudgmental approach to recovery is important for postpartum women with OUD.

-

•

Supportive spaces/relationships & emotional/physical postpartum selfcare are lacking.

-

•

Empowering mothers through employment, education & life skills may support recovery.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, Pregnant people, Postpartum, Dimensions of wellness, Qualitative research

Abstract

Background

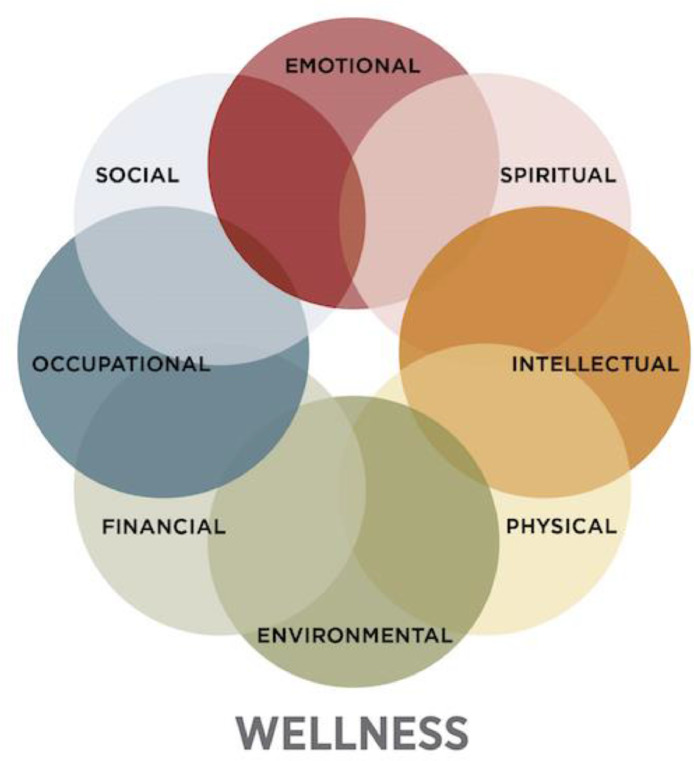

Recovery from opioid use disorder (OUD) during the perinatal period has unique challenges. We examined services for perinatal women with OUD using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) eight dimensions of wellness (DoW), which reflect whole person recovery.

Methods

We enrolled professionals from the Southwestern United States who work with people with OUD during the perinatal period. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted from April to December 2020. Participants were shown the DoW diagram (emotional, social, environmental, physical, financial, spiritual, occupational, intellectual) and asked to share how their clinic/agency addresses each DoW for perinatal people with OUD. Responses were transcribed and coded by two researchers using Dedoose software.

Results

Thematic analysis revealed ways professionals (n = 11) see how the services they provide fit into the DoW. This included: the need to provide mothers emotional support with a nonjudgmental approach, groups providing social support; guidance on nutrition, self-care, and a focus on the mother/infant dyad; assistance with employment and activities of daily living; parenting education; connecting mothers with resources and grants; providing a variety of spiritual approaches depending on the desire of the mother; and navigating the interpersonal environment as well as the physical space.

Conclusions

There are opportunities to expand the treatment and services provided to women with OUD during the perinatal period within all eight DoWs. Additional research is needed to identify effective strategies to incorporate these components into patient-centered, holistic care approaches.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, opioid use disorder (OUD) among pregnant people has increased by over 400% (Haight et al., 2018). The standard of care for OUD is Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD), which consists of full or partial opioid agonists (e.g., buprenorphine, methadone), or opioid antagonists (e.g., naltrexone), in addition to behavioral therapy (Kampman and Jarvis, 2015). While the risk for returning to opioid misuse during pregnancy is low (Faherty et al., 2019; Tsuda-McCaie and Kotera, 2022), this risk increases substantially postpartum (Office on Women's Health, 2016). Clinical recommendations call for prevention programming to reduce return to opioid misuse risk during the postpartum period (Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy | ACOG, n.d.), but, to date, research has been limited (Martinez and Allen, 2020). There is a need for the development and identification of evidence-based prevention interventions specific to the postpartum period that will ultimately aid in long-term recovery.

Recovery is defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as the process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential (SAMHSA, n.d.). To illustrate the idea of multidimensional health, SAMHSA has developed eight dimensions of wellness (DoW): emotional, social, environmental, physical, financial, spiritual, occupational, intellectual (Fig. 1). While the DoW and definition outlined by SAMHSA may be commonly incorporated in health promotion initiatives (e.g. university wellness programs) (Bernal, 2020; Eight Dimensions of Wellness | Campus Recreation, n.d.; Eight Dimensions of Wellness Overview, n.d.; The Eight Dimensions of Wellness, n.d.), the literature is scant in evaluations of its use as a framework for health-related outcomes. The limited research to date has focused on the DoW primarily within mental health, highlighting that wellness is multidimensional, dynamic and complex (Cummings and Bentley, 2018; Das, 2015). For example, one study used the DoW as a part of their program to reduce future psychiatric hospitalizations of their patients. Their findings were that hospitalizations were reduced and patients that attended the program more often were at a lower risk for such hospitalizations (Abdelnoor, 2018). Additional research examining the DoW aimed to identify the barriers to seeking and continuing care for infertility treatment. The themes identified were fit within the DoW, and were considered practical (the environmental, financial, physical), and affective (emotional, social and spiritual) as treatment seeking barriers; while barriers for return to treatment were primarily affective (Whittier Olerich et al., 2019). The authors concluded that addressing the resulting themes within the DoW would better support infertility treatment. Overall, while including parts of the DoW into health and wellness care show promise, the inclusion of DoW in its entirety is notably missing from the literature (Zechner et al., 2019). Moreover, this framework remains exploratory and has not yet been applied to substance misuse or OUD recovery, including OUD during the perinatal period which presents unique challenges to mothers. Revising, expanding, and/or developing treatment components in line with the DoW may prove beneficial for pregnant and postpartum people with OUD.

Fig. 1.

SAMHSA eight dimensions of wellness*

*From SAMHSA. (n.d.).

To address the gap in literature, we sought to understand how the DoW are currently being utilized during OUD recovery in the postpartum period. To address this goal, we completed semi-structured interviews with professionals who work with this target population. Using a qualitative approach enabled the team to describe how professionals understand and make meaning of the of DoW, and what recovery is in their work with women with OUD (Sobo, 2009). Here we provide the themes associated within each dimension and offer recommendations on how this framework can be utilized by professionals working with mothers with OUD.

2. Methods

We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with professionals, defined as working in a professional capacity for at least one year with perinatal women with OUD. Using purposive sampling via email, posted flyers, and word-of-mouth referrals, we recruited professionals in the state of Arizona, primarily in the urban areas of Phoenix and Tucson. We had a response rate of 73%. Professionals worked as healthcare providers in addiction medicine and/or obstetrics, or as Department of Child Safety (DCS) caseworkers. Purposive sampling was chosen due to the desire to hear from a range of professionals who work with mothers in recovery, and thus we aimed to recruit not only healthcare providers, but DCS caseworkers as well. State law in Arizona requires that newborns who have been substance exposed in utero be reported to DCS for possible investigation. While substance misuse is not considered child abuse per se, DCS investigates to determine if the environment is safe. DCS caseworkers therefore offer a unique perspective into support services available during the postpartum period for mothers with OUD. All professionals were invited to complete a 30-minute interview via the teleconferencing platform, Zoom for Health, between April and December 2020. Participants were shown a diagram (Fig. 1), and asked “How is your clinic or agency addressing these DoW for women that are both in early recovery from opioid use and postpartum?”

Our analysis used both inductive and deductive approaches, as we began with the DoW as an organizing framework for the interviewees and the analysts (Bradley et al., 2007). Interviews were transcribed and coded using Dedoose (Dedoose, 2021), a qualitative data analysis software application. Two authors (SM, YB) coded the data with the DoWs after achieving consensus on code definitions through repeated conversations with the team, to ensure inter-coder reliability (Bernard et al., 2016; Cornish et al., 2013). Responses to the question were coded to align only with the individual dimension that was presented and not with other codes. However, all authors discussed the coded text to identify sub-themes within the DoW-coded text. Not all professionals endorsed each DoW, but all DoW that were endorsed were included and are representative of our sample. Here, we report how participants describe these dimensions within the context of their programming.

3. Results

Professionals (n = 11) discussed the DoW and ways in which their agency provided support under each dimension (Table 1). Professionals included seven healthcare providers in obstetrics (n = 4) or MOUD (n = 3), as well as four from DCS (Table 2). All participants were female and, on average, were 42 years old with 8.5 years at their current organization and 12.5 years in the field.

Table 1.

Definitions, themes, and quotes by dimensions of wellness.

| Dimension | SAHMSA Definition * | Identified Theme | Participant Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional | The ability to express feelings, adjust to emotional challenges, cope with life's stressors, and enjoy life. It includes knowing our strengths as well as what we want to get better at, and living and working on our own but letting others help us from time to time. | Creating a safe space for working through factors in their life underlying addiction |

|

| Social | Having healthy relationships with friends, family, and the community, and having an interest in and concern for the needs of others and humankind. | Groups provide essential social support, especially for those who have not been through OUD treatment before |

|

| Physical | A healthy body. Good physical health habits. Nutrition, exercise, and appropriate health care | Guidance on nutrition, self-care, and a focus on the mother/infant dyad |

|

| Occupational | Participating in activities that provide meaning and purpose and reflect personal values, interests, and beliefs, including employment | Employment and activities of daily living |

|

| Intellectual | Keep our brains active and our intellect expanding | Skill building, educational attainment, and passing on lived experiences to others |

|

| Financial | Involves things such as income, debt, and savings, as well as a person's understanding of financial processes and resources | Connection to resources and grants |

|

| Spirituality | A broad concept that represents one's personal beliefs and values and involves having meaning, purpose, and a sense of balance and peace | Providing a variety of spiritual approaches depending on the desire of the mother |

|

| Environmental | Being able to be safe and feel safe | Physical space and interpersonal environment |

|

*Defined by SAMHSA8.

Table 2.

Professional characteristics.

| Participant | Professional role |

|---|---|

| C001 | mental health counselor and facilitator for postpartum depression support groups |

| C002 | neonatal nurse practitioner working with infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome |

| C003 | neonatal nurse practitioner and director of an outpatient patient facility providing care for substance exposed infants and treatment for mothers |

| C004 | registered nurse working on the prenatal and postpartum floors |

| C005 | pediatric social worker working in the neonatal intensive care unit and obstetric floors of a hospital |

| C006 | provider at an MOUD outpatient treatment facility |

| C009 | an investigator at DCS who responds to cases directly from the hospital |

| C010 | a DCS specialist who works with women to reunify with their children |

| C011 | a DCS specialist working in the Family Drug Court Unit with women who have had their children removed due to substance use |

| C012 | a DCS specialist who works with women while managing their open dependency cases |

| C015 | Fellow in maternal and fetal medicine who runs a high-risk pregnancy clinic for perinatal care |

DCS, Department of Child Safety; MOUD, medication for opioid use disorder.

3.1. Emotional

The emotional DoW was indicated as an important focus for our participants and their programs, particularly in providing a space for mothers to have emotional support with a nonjudgmental approach. Group sessions, held every day except Sundays, focus on providing that welcoming space. Within the nonjudgmental space, professionals also focused on addressing the underlying and contributing factors to substance misuse (e.g., unhappy relationships, coping skills)

“…we know that usually emotional and physical kind of go hand-in-hand. So definitely with us asking those questions, how do they deal with stress, do they have happy relationships, are there other contributing factors that are causing them to continue to use illegal substances....” C009

Additionally, participants discussed working with mothers to find other safe spaces, such as individual therapy, and/or treatment (e.g., inpatient facilities or outpatient programs).

3.2. Social

The social DoW was identified unanimously among participants as centering around "groups" providing a new means of social support. The central concept was that support groups for substance recovery or new mothers are social outlets and essential for recovery success.

"Part of that would be to get them into groups, whether that's a therapeutic group or a substance group, or just a new parent class. Something where they can kind of get a new social group and not just have the people and the triggers…” C009

Still, participants noted that some moms would prefer more "one-on-one" interaction and try to make this accommodation.

3.3. Physical

The physical DoW centered on nutrition, self-care, mother/infant dyad, and pain management. Some talked about a specific role in their organization that covered this topic- known as a family support specialist. While most participants touched on this dimension, it was also noted that the priority was to engage in a recovery program.

“With my experience with substance use, they have to kind of get themselves in recovery first. They have to get the drugs out of their system before they can start enhancing their health and kind of improving themselves." C009

Once baby is born, the focus shifts to mother's self-care (e.g., exercise, sleep, nutrition) and navigating that as mothers of infants. The focus on self-care is compounded with recognizing what it takes to care for a newborn, not only as new parents, but as a person in recovery. Participants articulated ways that these physical needs can be managed for both mothers and their child(ren) using coping skills. Once in a stable place with treatment, recovery includes looking at other ways to find enjoyment. This could be getting back in touch with a previous interest, defining or redefining who they are. Lastly, there is a need for health professionals to understand individualized pain management for this population, and the different needs that may be required.

3.4. Occupational

The occupational DoW included elements that fell under employment and activities of daily living (both as a parent and in life generally). First, professionals discussed helping mothers navigate finding employment (e.g., through employment resources or specialists, peer-to-peer recommendations). Participants also noted the importance of helping mothers feel like they can "do it on their own".

“Just a lot of the times they have never had a job. And it's nice to see- I have a couple moms right now…they've got employment, they've got their own apartment…telling me that they never thought they could do this on their own without a significant other or without family.” C011

Outside of paid employment, participants talked about helping mothers embrace their "job" as a mother. Similarly, participants discussed helping mothers “get a few wins,” and targeting areas tangential to employment, like planning and executive functioning. The skill-building described also falls under the intellectual dimension.

3.5. Intellectual

The intellectural DoW included a desire to provide parenting education that is skill building, rather than pejorative. It is also acknowledged that, depending on when interaction occurs, it can be difficult to provide education and skills to new mothers due to postpartum-specific challenges. Participants talked about assessing where parents are in terms of their education, if they want to continue (e.g., getting their GED), next steps of a career path, and being supportive in this process. Emphasis is placed on mothers’ future stability, but also as a part of recovery. For some, part of educational attainment includes being encouraged to use their lived experience to work with others as peer support.

“We have a lot of moms that once they get sober and they really start understanding addiction and, seeing the professionals work with them, [they] will recognize that they have the ability to help others as well. So, they'll actually go…to get recovery support specialist training. I have quite a few moms that do that. …” C011

3.6. Financial

The financial DoW was described in terms of assessing income needs, grants, and connecting mothers with resources. Professionals noted that despite this being a need, there are generally no direct forms of financial support for mothers. While financial assistance was not possible, professionals focused on providing community resources. Yet the referral is not always a straightforward process, and often takes hands-on help, as the resources available can be difficult to access. Yet, when more direct financial assistance is possible, it is contingent on a mother's ability to stay within a recovery program and/or life skillset (e.g., budgeting). There may be housing subsidies available, but only under specific conditions.

"We have housing subsidies if that's the last barrier for the parents. If they've maintained their sobriety, we can help them with housing as long as they've gone out themselves to try to get help. So, if they've exhausted family members, churches…. But they need to have a plan afterwards how they're going to maintain.” C010

3.7. Spiritual

The spiritual DoW showed variety in approach. Participants talked about traditional, organized religion with spiritual support that is dedicated to encouraging this population (e.g., hospital chaplains, recovery groups offered at churches), social reintegration of mindfulness practices, followed by general spirituality defined in different ways. Like therapy, participants identified spirituality as a potential source of support if an individual is part of a belief system. Mothers are encouraged to incorporate this as it works for them.

"We try to from the get-go understand where they're coming from in regards to a spiritual sense—what they believe in, what they look to in regards to inspiration, things like that, and kind of use that as motivational tools to kind of help them through this.” C010

It can be a sensitive topic, and while mothers may bring it up themselves, some participants mentioned that talking about spirituality can be a positive deterrent from other heavy conversations in the recovery process.

3.8. Environmental

The environmental DoW included navigating the interpersonal environment or those who are around you, as well as physical space that mothers in recovery occupy. Participants described this as helping those in a recovery program identify what a “healthy” environment looks like. Many participants emphasized “healthy” relationships and described helping mothers facilitate an interpersonal environment that is supportive of this.

"I try to stress that if it's their significant other that's pushing them to continue to use, or contributing to their use, getting them out of that environment and showing them that there is positivity out there and there are positive places. There's places for them to live a clean and sober lifestyle.” C009

In addition, professionals emphasized physical space. This largely focused on ensuring that their clients have a safe and welcoming space that supports their recovery (from the hospital and clinics to when they are at home), and to facilitate getting a safe space and equipment if needed (e.g., a place for baby to sleep, a car seat).

4. Discussion

Women who are in recovery from OUD are at high risk for an OUD recurrence postpartum, leading to negative outcomes for both mother and infant (Nawaz et al., 2022; Schiff et al., 2018). We analyzed a sample of professionals’ perspectives on how their agencies’ programs address the DoW and recovery for postpartum mothers with OUD. Our participants endorsed ways of operationalizing the DoW, with many activities addressing multiple dimensions. Participants described creating an emotionally supportive space where mothers can interact without the stigma of being a “drug user.” They also highlighted the importance of emotional and physical postpartum self-care, and empowering mothers to care for themselves and others, including their newborns, through employment, education, and skill building. Acknowledging that mothers’ relationships may increase the risk of substance misuse, participants shared methods of encouraging new “healthy” relationships, including exploring faith communities and support groups. These results are the first to map the DoW to the experience of recovery, in particular the recovery of postpartum mothers with OUD, and highlight opportunities for developing additional support within each of the DoW. While we explore the lived-experience and perspectives of mothers with OUD in a separate analysis (results forthcoming), the responses provided here by our sample of participants provide critical insight into treatment attitudes and procedures propagated by professionals in supporting mothers within the DoW framework.

Understanding the application of DoW gives insight into the service gaps, facilitators, and barriers to recovery that postpartum women face; offering insight into ways that recovery professionals can meet the needs of mothers by focusing on individual DoW, and the DoW as a whole. Our participants acknowledged the need to address the financial domain in particular but feeling a limited ability to do so. As our results illustrate, programs emphasize mothers taking responsibility for supporting themselves and their recovery. While our participants articulated their methods of skill-building, self-advocacy, and empowerment for mothers so they might gain paid employment, they lamented the lack of financial support for mothers who may be struggling in recovery. Also highlighted was the importance of the social domain, noting the importance of supporting mothers in severing harmful relationships and developing healthy relationships. This perspective is reflected in our results, yet as one participant noted, the MOUD clinic may be “their only connection to the outside world.” The results of our qualitative analysis indicate opportunities for enhancing financial support for mothers who need it and programming that facilitates the skills to build healthy relationships. Indeed, utilization of contingency management may be particularly advantageous to this population (Akerman et al., 2015; Peles et al., 2017; Tuten et al., 2012).

Our participants were asked about each DoW one at a time, yet our findings reveal overlap within the DoW. We saw this specifically with the intersection of the Social, Environment, and Physical DoWs. Participants spoke of the need for mothers to have supportive people and environments. Additionally, nonjudgmental approaches surfaced as a subtheme throughout. These have implications for how to approach recovery; it is at the same time each of the DoW, but also about how it all fits together. While our analysis is the first to apply the DoW to the recovery needs of women with OUD, our findings are consistent with the themes revealed in the literature investigating the lived experience of this population and in other contexts. Specifically, our themes under the Social (e.g., support system) and Emotional (e.g., stigma or nonjudgmental approach) DoWs are in line with other qualitative findings from providers that promote and impact postpartum recovery (Martin et al., 2022). Use of the DoW in mental health programs revealed physical, followed by the social dimension as the most frequently cited in a review of the literature (Zechner et al., 2019). Lastly, an infertility treatment program identified themes that map to the DoW framework such as geographic distance, concern of health risks, the emotional toll of treatment, attitudes of its effectiveness, relationships, and social support as barriers and facilitators to care (Whittier Olerich et al., 2019). Our study adds to the literature by going beyond what treatment professionals are typically focused on for this population (e.g., type of drug used, MOUD dose increases), and focuses on whole person recovery within the DoW framework. Current treatment recommendations for mothers with OUD fall under the Physical DoW (MOUD as the standard of care) but fall short of the definition of recovery by SAMHSA. While it is recognized that MOUD is a vital part of the recovery process, especially within the high-risk postpartum period, there are other pieces to recovery that treatment recommendations may not cover adequately.

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses

A strength of this analysis is our purposive sampling method to include a range of professionals who interact with the target population. This is representative of different areas of the recovery process (e.g., professionals who work in the hospital when mother gives birth, outpatient MOUD, department of child services), and therefore is reflective of the lived experience of mothers and the many different time points of interaction with professionals in government and non-government organizations. Despite our sampling method, our recruitment period coincided with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted our final sample size. An additional limitation of this data is that it is from the perspective of professionals alone and does not include how women with OUD in recovery would see how these DoW are being addressed (or not). While considered a limitation, the major themes from our findings are consistent with other literature that focuses on the perspectives of professionals (Reese et al., 2021; Syvertsen et al., 2021). Understanding how professionals feel that their agency or role falls under these categories is essential to making recommendations in what may be needed to address these DoW. Finally, the perspectives from our sample are coming from a single state within the US; thus, limiting generalizability. It is likely that the DoWs are applied differently within different healthcare systems; even within a single state, as there can be a range of healthcare systems and different experiences in each.

4.2. Implications and future directions

Many observations from this study highlight the numerous challenges that mothers in recovery face as they are caring for themselves, their recovery (from childbirth as well as managing OUD), and a new infant. We report elsewhere the fragmented approach to recovery (results forthcoming), within an already fragmented healthcare system. There can be limited opportunities for patient-centered holistic care, and while resources may exist for each DoW, the burden falls on women (who are already overwhelmed in both their recovery and being a new mother) to connect those dots. Not all participants endorsed each DoW as a focus for their agency. While depending on their professional role, this may be understandable, it also highlights the gaps within the fractured and siloed system of recovery that women are facing. Recovery, as defined by SAMHSA, includes each DoW, yet if agencies only focus on some of the DoWs, they are falling short. Understanding how professions see DoW in their work is important in how the DoWs are being operationalized. This has significant applied implications as the DoWs may or may not be used as SAMHSA intends. Using the qualitative perspectives from our participants to translate this into the existing infrastructure may lead to a system to adequately address recovery.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that SAMSHA's DoW are somewhat addressed in OUD care during the perinatal period; however, it also provides insight into the service gaps, facilitators, and barriers to recovery that postpartum women face. Revealing the themes associated with the DoW allows for exploring the development of adjunctive behavioral treatment for perinatal OUD, in a pursuit to develop interventions to address these unmet needs and support long-term OUD recovery.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflicts declared.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver Child Health and Human Development (DP2 HD105541; PI: Allen) and University of Arizona's Research, Discovery, and Innovation Internal Funding Program (#1269; PI: Allen).

Contributors

This work was funded by grants received by Alicia Allen. All authors contributed to development of the research question, recruitment efforts, analysis of the data, synthesis, and discussion of the results. Two authors (SM, YB) completed interviews and coded the data. The lead author primarily contributed to writing the manuscript, with feedback and edits received from all authors. All authors have reviewed and approve the final manuscript.

References

- Abdelnoor R. Wilmington University (Delaware); 2018. Using the Guidance Center's Adult Partial Care Program to Reduce Psychiatric Hospitalizations.http://ezproxy.library.arizona.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/using-guidance-centers-adult-partial-care-program/docview/1965535846/se-2?accountid=8360https://arizona-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/openurl/01UA/01UA?&aufirst=R [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S.C., Brunette M.F., Green A.I., Goodman D.J., Blunt H.B., Heil S.H. Treating tobacco use disorder in pregnant women in medication-assisted treatment for an opioid use disorder: a systematic review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2015;52:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal B. [Our Lady of the Lake University]; 2020. Wellness Are We Practicing What We Preach? A Look Into Doctoral Student Wellness, a Focus Group Study.http://ezproxy.library.arizona.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/wellness-are-we-practicing-what-preach-look-into/docview/2434548027/se-2?accountid=8360https://arizona-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/openurl/01UA/01UA?&aufirst=Be [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H.R., Wutich A., Ryan G.W. SAGE Publications; 2016. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E.H., Curry L.A., Devers K.J. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish F., Gillespie A., Zittoun T. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. SAGE; 2013. Collaborative analysis of qualitative data. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C.R., Bentley K.J. A recovery perspective on wellness: connection, awareness, congruence. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Mental Health. 2018;5(2):139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Das D. CUNY CIty College of New York; 2015. Empirical Investigation of SAMHSA's (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) Model of Wellness. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose (9.0.17). (2021). SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com.

- Eight Dimensions of Wellness | Campus Recreation. (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://rec.arizona.edu/about/eight-dimensions-wellness.

- Eight Dimensions of Wellness Overview: Wellness at Northwestern - Northwestern University. (n.d.). Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.northwestern.edu/wellness/8-dimensions/.

- Faherty L.J., Kranz A.M., Russell-Fritch J., Patrick S.W., Cantor J., Stein B.D. Association of punitive and reporting state policies related to substance use in pregnancy with rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight S.C., Ko J.Y., Tong V.T., Bohm M.K., Callaghan W.M. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018;67(31):845–849. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampman K., Jarvis M. American society of addiction medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J. Addict. Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C.E., Almeida T., Thakkar B., Kimbrough T. Postpartum and addiction recovery of women in opioid use disorder treatment: a qualitative study. Subst. Abus. 2022;43(1):389–396. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1944954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A., Allen A. A review of nonpharmacological adjunctive treatment for postpartum women with opioid use disorder. Addict. Behav. 2020;105 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz N., Hester M., Oji-Mmuo C.N., Gomez E., Allen A.M. Risk factors associated with perinatal relapse to opioid use disorder. Neoreviews. 2022;23(5):e291–e299. doi: 10.1542/neo.23-5-e291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office on Women's Health. (2016). White Paper: opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women. December. https://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/federal-report/index.html#a2016.

- Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy | ACOG. (n.d.). Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/08/opioid-use-and-opioid-use-disorder-in-pregnancy.

- Peles E., Sason A., Schreiber S., Adelson M. Newborn birth-weight of pregnant women on methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a national contingency management approach trial. The Am. J. Addict. 2017;26(2):167–175. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese S.E., Riquino M.R., Molloy J., Nguyen V., Smid M.C., Tenort B., Gezinski L.B., Cleveland L. Experiences of nursing professionals working with women diagnosed with opioid use disorder and their newborns: burnout and the need for support. Adv. Neonatal Care. 2021;21(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (n.d.). Creating a healthier life: a step-by-step guide to wellness. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma16-4958.pdf.

- Schiff D.M., Nielsen T., Terplan M., Hood M., Bernson D., Diop H., Bharel M., Wilens T.E., LaRochelle M., Walley A.Y., Land T. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartumwomen in Massachusetts. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;132(2):466–474. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobo E.J. Routledge; 2009. Culture and Meaning in Health Services Research: An Applied Approach. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen J.L., Toneff H., Howard H., Spadola C., Madden D., Clapp J. Conceptualizing stigma in contexts of pregnancy and opioid misuse: a qualitative study with women and healthcare providers in Ohio. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;222 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Eight Dimensions of Wellness. (n.d.). William & Mary. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.wm.edu/offices/wellness/about/eight-dimensions/index.php.

- Tsuda-McCaie F., Kotera Y. A qualitative meta-synthesis of pregnant women's experiences of accessing and receiving treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022 doi: 10.1111/dar.13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuten M., Svikis D.S., Keyser-Marcus L., O'Grady K.E., Jones H.E. Lessons learned from a randomized trial of fixed and escalating contingency management schedules in opioid-dependent pregnant women. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):286–292. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittier Olerich K., Summers K., Lewis A.M., Stewart K., Ryan G.L. Patient identified factors influencing decisions to seek fertility care: adaptation of a wellness model. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2019:1–13. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2019.1705263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner M.R., Pratt C.W., Barrett N.M., Dreker M.R., Santos S. Multi-dimensional wellness interventions for older adults with serious mental illness: a systematic literature review. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2019;42(4):382–393. doi: 10.1037/prj0000342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]