Highlights

Cu species with tunable loading supported on N-doped TiO2/C were successfully fabricated utilizing MOFs@CuPc precursors via the pre-anchor and post-pyrolysis strategy.

Cu species with tunable loading supported on N-doped TiO2/C were successfully fabricated utilizing MOFs@CuPc precursors via the pre-anchor and post-pyrolysis strategy.

Restructured CuN4&Cu4 performed the highest NH3 yield (88.2 mmol h−1 gcata−1) and FE (~94.3%) at − 0.75 V due to optimal adsorption of NO3− and rapid conversion of the key intermediates.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40820-023-01091-9.

Keywords: Metal–organic frameworks, Copper phthalocyanine, Electrocatalytic nitrate reduction reaction

Abstract

Direct electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction (NITRR) is a promising strategy to alleviate the unbalanced nitrogen cycle while achieving the electrosynthesis of ammonia. However, the restructuration of the high-activity Cu-based electrocatalysts in the NITRR process has hindered the identification of dynamical active sites and in-depth investigation of the catalytic mechanism. Herein, Cu species (single-atom, clusters, and nanoparticles) with tunable loading supported on N-doped TiO2/C are successfully manufactured with MOFs@CuPc precursors via the pre-anchor and post-pyrolysis strategy. Restructuration behavior among Cu species is co-dependent on the Cu loading and reaction potential, as evidenced by the advanced operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and there exists an incompletely reversible transformation of the restructured structure to the initial state. Notably, restructured CuN4&Cu4 deliver the high NH3 yield of 88.2 mmol h−1 gcata−1 and FE (~ 94.3%) at − 0.75 V, resulting from the optimal adsorption of NO3− as well as the rapid conversion of *NH2OH to *NH2 intermediates originated from the modulation of charge distribution and d-band center for Cu site. This work not only uncovers CuN4&Cu4 have the promising NITRR but also identifies the dynamic Cu species active sites that play a critical role in the efficient electrocatalytic reduction in nitrate to ammonia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40820-023-01091-9.

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is an indispensable chemical used mainly in the manufacture of fertilizer, the synthesis of nitric acid and nitrate, and a refrigerant [1, 2]. The Haber–Bosch process, which utilizes N2 and H2 as input gases in a demanding environment (high temperature and pressure), is widely recognized as one of the greatest breakthroughs of the twentieth century and accounts for the overwhelming majority of yearly NH3 production [3, 4]. Compared to the Haber–Bosch process (high CO2 emissions and energy consumption), an environment-friendly NH3 synthesis by an electrocatalytic N2 reduction reaction (NRR) has garnered conspicuous attention, which enables the electrosynthesis of NH3 [5, 6]. Furthermore, nitrate (NO3−) is the usual contaminant in surface and ground water, exacerbating soil and water eutrophication and posing a threat to the environment and human health [7]. It could be an intriguing tactic for electrocatalytic NO3− reduction reaction (NITRR) to NH3 under ambient circumstances via an eight-electron transfer reaction [8–10]. Hence, seeking low-cost, excellent selective, and efficient electrocatalysts capable of enabling both NH3 production and NO3− conversion rate is critical.

Single-atom catalysts have been extensively recruited in various catalytic reactions due to their maximized atomic utilization and coordination diversity [11–13]. To date, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have been selected as the platform for the direct or indirect fabrication of single-atom catalysts on account of the multifarious anchoring mechanisms (e.g., spatial confinement, structural defects, and coordination strategies) in comparison with carbon nanotubes and graphene-based supported materials [14]. Among amine-functionalized MOFs, e.g., NH2-UiO66 Zr, NH2-MIL125 Ti (here denoted as aMIL), and NH2-MIL101 Al, the uncoordinated amine groups (–NH2) as the electron donors can stabilize and anchor single metal to synthesize single-atom electrocatalysts with well-defined metal-N4 structure [15–18].

In general, transition-metal atoms are susceptible to migrate and aggregate during pyrolysis with the high temperature-induced effect, forming metal nanoclusters and/or nanoparticles, which is always a thorny problem that seriously affects the targeted synthesis of highly loaded metal single-atom catalysts [19]. In addition, among the single-atom catalysts, Cu electrocatalysts can be restructured and induced by the special potential to form Cu nanoclusters and nanoparticles during electrocatalytic reduction reactions. In situ-formed metal nanoclusters or nanoparticles modulate the d-band center of the metal –N4 active site, optimize its electronic structure and improve catalytic performance [20, 21]. For instance, Fu and co-workers reported the transformation from Cu single-atom catalysts (CuN4 configuration) to the compound of Cu single-atom and nanoclusters during the alkaline oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). The restructured Cu-nanoclusters can regulate the d-band center of CuN4 and balance the free energy of intermediates, benefiting ORR activity [22]. Liu and co-workers found the reversible transformation of atomically dispersed Cu atoms and Cu3/Cu4 clusters during the alkalescent carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR) [23]. In applying NITRR, Wang and co-workers observed the dynamic reversible transformation between Cu single-atom catalysts (Cu loading: 1.0 wt%) and Cu9 nanoclusters with aggregation driven by the potential in an alkaline electrolyte and redispersion driven by oxidation at environmental conditions. Cao and co-workers verified in situ clustering of single-atom Cu in MOFs (Cu loading: 1.9 wt%) in Na2SO4 and NaNO3 electrolytes [24, 25]. In light of the aforementioned development, exploring the dual-driven behaviors of Cu species loading and reaction potential for electrocatalytic NH3 production is essential, especially for identifying the dynamical active sites.

Herein, Cu species (single-atom, clusters, and nanoparticles) anchored on N-doped TiO2/C (NTC) were synthesized via the pre-anchor and post-pyrolysis strategy. As a result, the restructuration behavior of Cu species was jointly related to Cu loading and reaction potential during electrocatalytic NITRR. Specifically, the higher copper loading and negative potential will more easily transform copper single atoms into copper clusters and particles. Cu1.5/NTC exhibited the highest NH3 yield with 88.2 mmol h−1 gcata−1 (0.044 mmol h−1 cm−2) and FE (~ 94.3%) at the potential of − 0.75 V versus RHE, which was superior to NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts. Operando XAS and density functional theory (DFT) calculation results confirmed that the restructured CuN4&Cu4 can enhance the adsorption ability of NO3− and promote the rapid potential-determining step conversion of *NH2OH to *NH2 intermediates.

Experimental Section

Preparation of aMIL@CuPc-x Precursors

The synthesis of NH2-MIL125 (Ti) refers to our previous work with minor modifications [26]. In the synthesis of NH2-MIL125 (Ti)@CuPc precursor (aMIL@CuPc-x), NH2-BDC (840 mg, 4.6 mmol), C12H28O4Ti (0.90 mL, 3.3 mmol), and a series of amounts of C32H16CuN8 (CuPc) were successively added into the mixed solution containing anhydrous DMF and MeOH (60 mL, v/v = 9:1), and then stirred magnetically at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, the resulting solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and heated at 150 °C for 72 h until cooling to the room temperature. DMF and MeOH were alternately washed three times and centrifuged (8,000 rpm, 6 min), and then dried at 120 °C under dynamic vacuum for 24 h to obtain the final precursor powder. The additive amounts of CuPc were aMIL (0 mg), aMIL@CuPc-1 (46 mg, ~ 0.08 mmol), aMIL@CuPc-2 (92 mg, ~ 0.16 mmol) and aMIL@CuPc-3 (184 mg, ~ 0.32 mmol), respectively.

Preparation of Derivatives

The powder precursors were calcined at 800 °C with the rate of 2 °C min−1 for 3 h in Ar. N-doped TiO2/C (NTC) with different Cu loading could be prepared by the precursors of pyrolysis aMIL@CuPc-x. ICP-OES showed that the Cu content was 0.673 (~ 0.7), 1.540 (~ 1.5) and 3.242 (~ 3.2) wt%, respectively. The samples were named in turn as NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC. The entire synthesis process is shown in Scheme S1.

Electrochemical Measurements

All NITRR electrochemical measurements were performed on an electrochemical workstation (Ivium Vertex, Netherlands) in a three-electrode system using the H-type electrolytic cell separated by a Nafion 117 membrane (DuPont) at the room temperature (Fig. S1). Nafion 117 membrane was pretreated in the 5 wt% H2O2 solution at 80 °C for 1 h, rinsed by ultrapure water and then in ultrapure water at 80 °C for another 1 h, rinsed with ultrapure water several times. Typecially, as-prepared sample (5 mg) was dispersed in 900 μL of isopropanol (IPA) aqueous solution (v/v, 1:1) and 100 μL Nafion solution (5%), and ultrasonicated for 30 min. The homogeneous ink was dropped onto the commercial carbon paper (1 cm × 1 cm, mass loading: ca. 0.5 mg cm–2). Pt plate (1 cm × 1 cm), saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and above carbon paper were used as the counter, reference and working electrode in 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 50 ppm NaNO3 mixed solutions. The potentiostatic test was conducted at constant potentials for 2 h with a flow rate of Ar for 10 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm) and a stirring rate of 400 rpm. Cyclic voltammetry activation was not performed before the experiment, and the pH changes before and after the experiment were ignored. The potential reference equation (Eq. 1) was converted into the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

| 1 |

Operando XAS Experiment

The NITRR operando XAS experiment was tested in fluorescence mode at a BSRF 4B9A line station and used the home-built H-type cell referring to the NITRR experimental condition. Where the electrolyte was a mixed aqueous solution with Ar-saturated 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 50 ppm NaNO3, and the ink is uniformly dropped on a carbon paper of 1 cm × 2 cm (with a mass of about 2.5 mg cm–2), and the operando XAS experiment is started at a specific voltage without the cyclic voltammetry (CV) activation.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of MOFs@CuPc-x Precursors

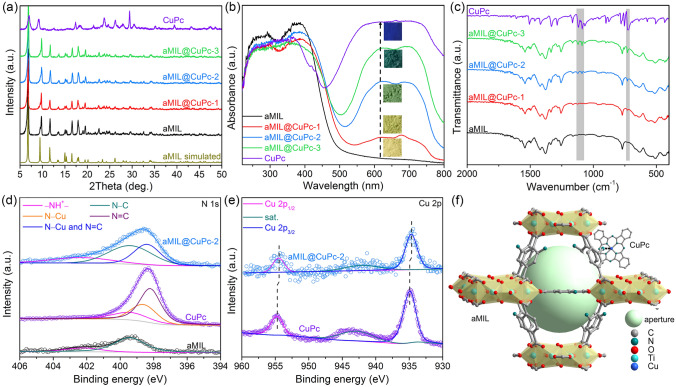

All of the experimental powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of the as-synthesized aMIL@CuPc-based precursors (Fig. 1a) agree well with the simulated one of pure aMIL due to the similarity of the strong diffraction peaks between aMIL and CuPc or the lower mass loading of CuPc. Increased visible-region absorption and a gradual darkening of color with increasing CuPc loading are observable in the UV–vis diffraction spectra (DRS) and corresponding optical photographs (Fig. 1b) of aMIL, aMIL@CuPc-1, aMIL@CuPc-2, aMIL@CuPc-3, and CuPc samples, proving the presence of aMIL and CuPc composite. The vibrational peaks of aMIL@CuPc-based precursors in Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (Fig. 1c) at approximately 1116, 1086, and 725 cm−1 correspond to C–H in-plane deformation (β(C–H)), C–N stretching in pyrrole (ν(C–N)), C–N out-of-plane deformation (γ(C−N)) except for the characteristic peaks of aMIL [27]. To uncover the link mode between aMIL and CuPc molecules, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was characterized for aMIL, CuPc, and aMIL@CuPc-2 precursors. The presence of –NH–+ (402.3 eV) and N–C bonds (399.4 eV) among the –NH2 group in aMIL is confirmed by typical high-resolution XPS spectra of N 1s (Fig. 1d) [26]. In addition, there exist N–C bond (399.4 eV), pyrrolic N–Cu coordination form (398.6 eV), and N=C bond (398.2 eV) for the CuPc sample [28]. Due to the proximate binding energy of N–Cu and N=C bonds and higher half-peak breadth of N–C bonds given by both aMIL and CuPc, pyrrolic N–Cu and N=C bonds were joint fitted through deconvolution locating at 398.4 eV. Significantly, typical high-resolution XPS spectra of Cu 2p of aMIL@CuPc-2 slightly shift to the lower binding energy compared with that of CuPc in view of the electron-donation effect of –NH2 group [29], the axial N of –NH2 group over aMIL could be coordinated with CuPc to form [Ti8(OH)4O8(BDC-NH2)6-x]–(BDC-NH)x–(CuPc)x (Fig. 1f). Compared to pure CuPc, the average coordination number (CN) of Cu–N bond over the aMIL@CuPc-2 increases from 3.72 to 4.20 (Fig. S4, Table S1). Meanwhile, aMIL@CuPc-based precursors retain the tetragonal plate shape of the aMIL matrix (Fig. S5), while CuPc molecules can form nanorod structures due to self-nucleation with higher CuPc loading [30].

Fig. 1.

a–c PXRD patterns, UV–vis DRS and optical photograph, FT-IR spectra of aMIL, aMIL@CuPc-x, CuPc samples. d, e Typical high-resolution XPS spectra of N 1s and Cu 2p of aMIL, CuPc and aMIL@CuPc-2 samples. f Assembly mechanism between aMIL and CuPc

Structural Characterization of Cux/NTC Derivatives

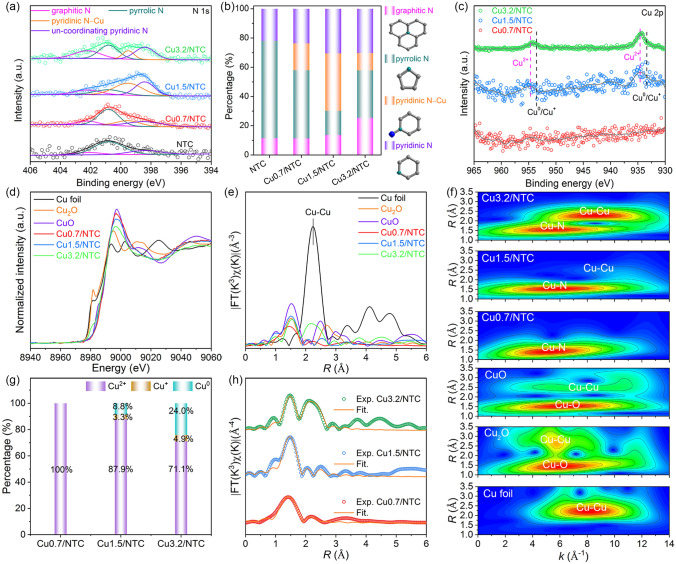

The rational design of precursors with variable loading of CuPc affects the dispersity of Cu species among aMIL@CuPc-based derivatives to a certain extent. The PXRD patterns (Fig. S6, Table S2) substantiate the existence of the mixed crystal phase with Anatase and Rutile TiO2, and the mass ratio (mAnatase: mRutile) is 2.34. Besides, a distinct diffraction peak exists at 43.3º of metallic Cu phase (JCPDS No: 04–0836) just for Cu3.2/NTC sample. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area, pore volume, and Raman spectra (Fig. S7, Table S3) of NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC samples show that Cu1.5/NTC possess the biggest specific surface area, larger pore volume and the degree of graphitization, which can provide more active sites and enhance the conductivity of supported materials to accelerate the mass transfer of NITRR. The characteristic peaks of the high-resolution XPS N 1s spectra (Fig. 2a) at 402.2, 400.8, 399.5, and 398.4 eV correspond in turn to graphitized N, pyrrole N, pyridine N–Cu, and un-coordinating pyridine N, revealing the presence of N-doped C and Cu–N species [28]. Additionally, the content of pyrrole N–Cu of Cu3.2/NTC sample is lower than Cu0.7/NTC along with the progressive introduction of CuPc, indicating that Cu3.2/NTC contains a small amount of Cu–N species. High-resolution XPS of Cu 2p spectrum of Cu0.7/NTC (Fig. 2c) has a low signal-to-noise ratio, which can be attributed to the low Cu content. The peaks of Cu1.5/NTC at 955.0 and 934.7 eV can be described as Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 of Cu2+ [31], and the peaks of Cu3.2/NTC samples at 953.5 and 933.3 eV are Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 of Cu0 or Cu+ [32]. The high-resolution XPS of Cu 2p spectra for both Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC display a large half-peak width, indicating mixed valence states of Cu with 0, + 1, and + 2. Further pre-edge and white line peaks of the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra at Cu K-edge (Fig. 2d) suggest that the average valence states of Cu successively are + 2 ≥ Cu0.7/NTC > Cu1.5/NTC > Cu3.2/NTC > + 1. As shown in the k3-weighted Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) and wavelet transform extended X-ray absorption fine-structure (WT-EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 2d, f), Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC have the Cu–N scattering path in the first shell, while Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC sample show the Cu–Cu scattering path in the second shell compared with Cu foil, Cu2O, and CuO reference samples. The proportions of Cu2+, Cu+, and Cu0 for Cu1.5/NTC are 87.9%, 3.3% and 8.8%, the corresponding proportions for Cu3.2/NTC are 71.1%, 4.9% and 24.0% in the linear combination fitting (LCF) results of XANES spectra (Figs. 2g and S10), manifesting the generation of metallic Cu with the high temperature-induced effect during pyrolysis. The average CN of Cu–N bond (Figs. 2h and S11, Table S4) for Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC are 3.99 (~ 4), 4.02 (~ 4), and 3.61 (< 4), and the average CN of Cu–Cu bonds for Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC samples are 2.84 (~ 3) and 7.41 (~ 7) based on the proportion of Cu0 in XANES LCF.

Fig. 2.

a High-resolution XPS of N 1s; b N contents and configurations; c Cu 2p for Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC. D–f Cu K-edge XANES, k3-weighted FT-EXAFS, and WT-EXAFS spectra of Cu foil, Cu2O, CuO, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, Cu3.2/NTC. g, h XANES LCF and FT-EXAFS spectra fitting curves of Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, Cu3.2/NTC

Morphology of Cux/NTC Derivatives

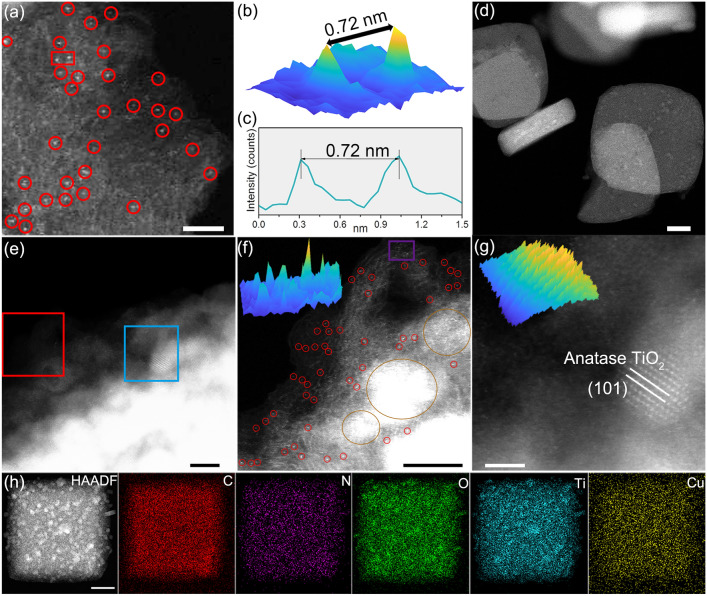

The dispersion state of Cu species and supported materials among Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC were observed by aberration-correction high-angle-annular-dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC HAADF-STEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM). AC HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 3a–c) of Cu0.7/NTC reveals that Cu is monodispersed on the NTC and the distance of neighbored Cu atoms is relatively large (~ 0.72 nm). AC HAADF-STEM images of Cu1.5/NTC (Fig. 3d–f) provide vital evidence for the coexistence form of Cu species with both monodispersity and clusters (small red cycles and big dark yellow circles in Fig. 3f). Further, Fig. 3g (the enlarged image of the blue rectangular area of Fig. 3e) and HRTEM images of Cu1.5/NTC (Fig. S13) uncover the existence of both anatase and rutile TiO2 on the surface of N-doped C supported materials, which further confirmed with the well-defined elements distribution of C, N, O, Ti, and Cu (Fig. 3h). Furthermore, Cu nanoparticles with exposed (111) crystal plane load on the surface of NTC material for Cu3.2/NTC sample, integrating with the EDX mapping images (Fig. S14).

Fig. 3.

a AC HAADF-STEM image of Cu0.7/NTC. b, c 3D and line profile images of the red rectangular area in a. d–g HAADF-STEM images of Cu1.5/NTC, and f, g are the enlarged images of the red and blue rectangular areas in e. h EDX mapping images of Cu1.5/NTC. Scale bar: a 2 nm, e–g 5 nm, d, h 200 nm

Electrocatalytic NITRR Performances

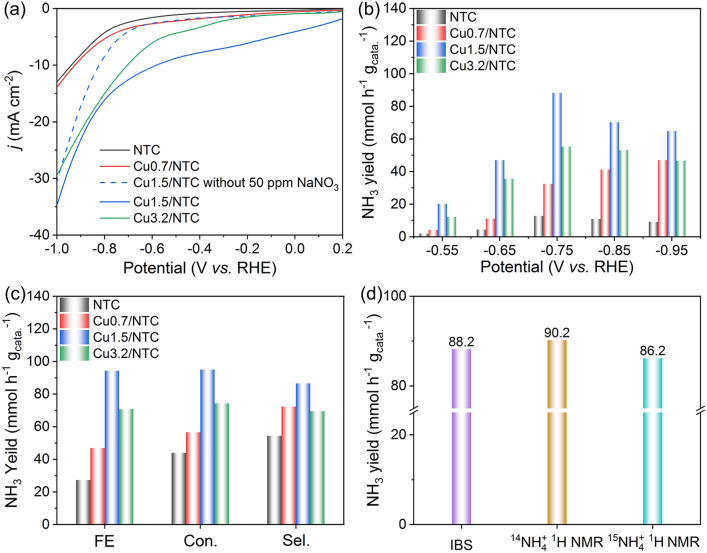

The NITRR performances of NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts were evaluated in 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 50 ppm NaNO3 electrolytes. As exhibited in the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) polarization curves (Fig. 4a), the current density (j) of Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC are higher than that of NTC, and Cu1.5/NTC has the highest current density in the range of 0.2 to − 1.0 V, indicating that the introduction of appropriate Cu species can promote the NITRR process. Compared to the LSV curves of Cu1.5/NTC before and after adding 50 ppm NaNO3, the potential range from − 0.55 to − 0.95 V versus RHE was selected to quantify the NH3 production performance. After the potentiostatic experiment at the potentials of − 0.55, − 0.65, − 0.75, − 0.85, and − 0.95 V for 2 h, the products of NH3, NO2− and catalysis substrate (NO3−) were detected via colorimetric methods (Figs. S15–S17). Cu1.5/NTC delivers best NH3 yield (88.2 mmol h−1 gcata−1) and lower NO2− yield at − 0.75 V, which is superior to NTC, Cu0.7/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC at this potential (Figs. 4b and S18). Meanwhile, Cu1.5/NTC presents the optimal FE (94.3%), 95.0% conversion rate, and 86.6% selectivity of NO3− to NH3 (Fig. 4c), which confirms that Cu is the main active site of NITRR, agreeing well with that the introduction of appropriate Cu species significantly increased the AECSA to enhance the performance of electrocatalytic NH3 production (Fig. S19). Meanwhile, NH3 yield and FE for Cu1.5/NTC show no significant decay during the continuous long-term tests at − 0.75 V (Fig. S20). To ensure the N source and accurately estimate NH3 yield, multi-position in one mode of 15N isotope labeling experiment, indophenol blue spectrophotometric (IBS), and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods were engaged by conducting the product from the potentiostatic experiment for Cu1.5/NTC at − 0.75 V using blank Na2SO4 solution, Na14NO3 and Na15NO3 as N sources (Figs. S21–S23). Based on the prominent characteristic triple and double peaks of 14NH4+ and 15NH4+ (Figs. S22 and S23) [33], NH4+ yield quantified with 1H NMR method is very close to the results of IBS method (Fig. 4d). The reliable NH3 yield and FE of Cu1.5/NTC executed in neutral electrolyte are on par with the majority of published Cu-based electrocatalysts (Table S5).

Fig. 4.

a LSV polarization curves of NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC in 0.5 M Na2SO4 electrolytes with 50 ppm NaNO3, and without 50 ppm NaNO3 for Cu1.5/NTC. b NH3 yield of NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC. c The comparison of FE, conversion rate (Con.) and selectivity (Sel.) of NTC, Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC samples at –0.75 V. d Comparison of NH3 yield via IBS and 1H NMR methods

Restructuration Process Detected with Operando XAS

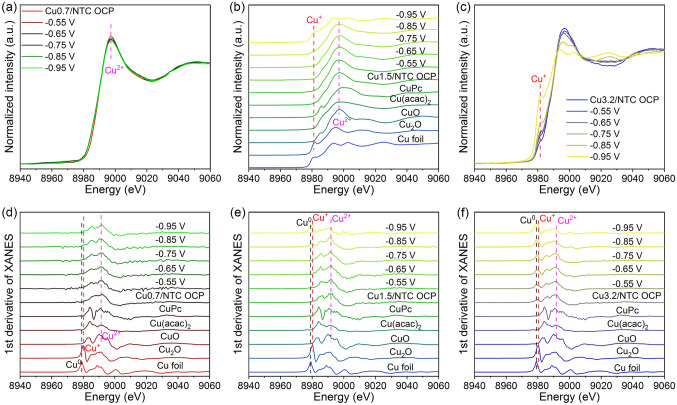

Operando XAS experiment is frequently employed to accurately record the dynamic structural changes of metal activity sites during electrocatalysis reactions of single-atom catalysts [34, 35]. Operando XAS experiments of Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC were conducted at open circuit potential (OCP), − 0.55, − 0.65, − 0.75, − 0.85, and − 0.95 V versus RHE for Cu K-edge using the home-built H-type cell referring to the NITRR experimental condition, and Cu foil, Cu2O, CuO, Cu(acac)2, CuPc are reference samples. There are no obvious differences in the structure and valence state at different potentials in the XANES and 1st derivative of XANES spectra for Cu0.7/NTC electrocatalyst (Fig. 5a, d). The characteristic peaks in the XANES spectra of Cu1.5/NTC (Fig. 5b) at 8988.7 eV are attributed to the electron transition from Cu2+ 1s to Cu2+ 4p, while the peaks of − 0.85 and − 0.95 V located at ~ 8982 eV originate the electron transition from Cu+ 1 s to Cu+ 4py [36], which indicate that Cu1.5/NTC electrocatalyst begins undergoing the obvious transition from Cu2+ to Cu+ at − 0.85 V. The 1st derivative of XANES spectra (Fig. 5e) at the potentials of − 0.85 and − 0.95 V have a big half-peak width at ~ 8979 and 8980 eV [37], revealing that Cu1.5/NTC has the mixed valence states of Cu0, Cu+, and Cu2+ at these potentials. The characteristic peaks of Cu+ in the XANES spectra and Cu0 in the 1st derivative of XANES spectra for Cu3.2/NTC at all the potentials (Fig. 5c, f) become more robust with the negative shift of reaction potential, suggesting that the Cu species among Cu3.2/NTC experience the significant reduction process of Cu2+ → Cu+ → Cu0.

Fig. 5.

a–c Operando XANES spectra of Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC. d-f 1st derivative of XANES spectra of Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC and Cu3.2/NTC

To understand the valence state and coordination environment of Cu species thoroughly for Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts, we pay more attention to resolving the FT-EXAFS, XANES LCF, and WT-EXAFS spectra at the representative potentials of OCP, − 0.75, − 0.85, and − 0.95 V. The k3-weighted FT-EXAFS fitted spectra together with the fitting results of XANES LCF spectra (Figs. S24 and S25, Table S6) show that Cu0.7/NTC still keeps the dominant configuration of Cu–N4 at OCP, − 0.75, − 0.85, − 0.95 V. However, the partial Cu+–Nx generated at the − 0.75 V potential could detach from the anchorage of N-doped C among Cu– N4 and undergo the significant restructuration driven by the potential at − 0.85 V to form Cu2 clusters with Cu–N4 (CuN4&Cu2), and then further restructuring to form CuN4&Cu6 at − 0.95 V. The weak Cu–Cu bond (k: 8.9 Å−1) and apparent Cu–Cu bonds (k: 9.9 Å−1) could be detected in the WT-EXAFS spectra of − 0.85 and − 0.95 V for Cu0.7/NTC (Fig. S26), except the findable Cu–N bonds at the potentials from OCP to − 0.75 V. Discriminatively, the CN of Cu–N bonds at OCP, − 0.75, − 0.85, − 0.95 V for Cu3.2/NTC are 3.58, 2.89, 1.55, 0.41 in succession, showing that the primary configurations of Cu species at OCP and − 0.75 V are Cu2+ − N4, while Cu0 nanoparticles (NPs) exist at − 0.85 and − 0.95 V (Figs. S27–S29, Table S7). The restructuration behavior in Cu3.2/NTC system can be jointly dependent on the Cu loading amount and reaction potential since Cu0 content of Cu3.2/NTC grows substantially more than that of Cu0.7/NTC at the same potentials.

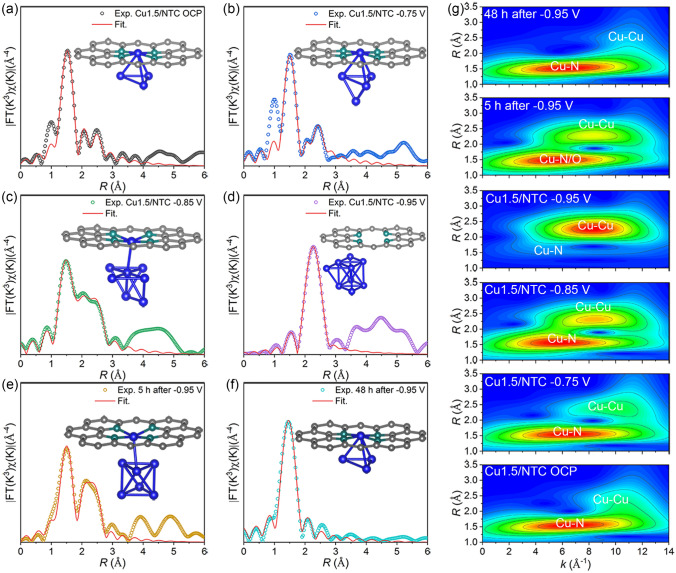

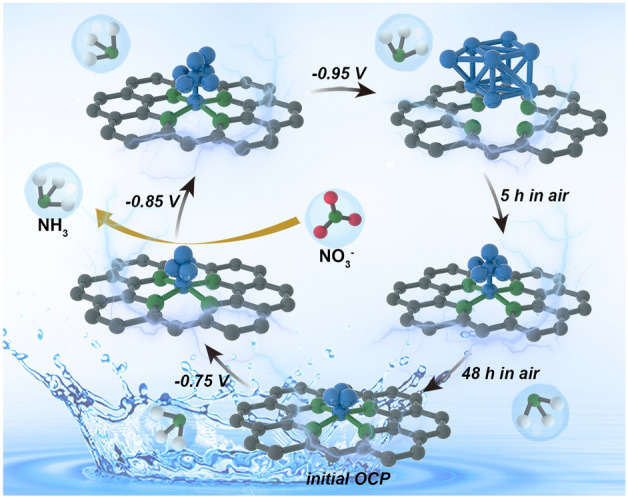

Given the k3-weighted FT-EXAFS fitting spectra integrated with the XANES LCF results of Cu1.5/NTC (Figs. 6a–d, S30–S32, and Table S8), the CN of Cu–N bonds at OCP, − 0.75, − 0.85, − 0.95 V are 3.90, 3.87, 3.58, 0.59, and the CN of Cu–Cu bonds are 2.90, 4.12, 7.29, and 8.85, so it is reasonable to assume that Cu1.5/NTC had CuN4&Cu3, CuN4&Cu4, CuN4&Cu7, and Cu9 structures at the aforementioned potentials (inset of Fig. 6a–d). Intrigued by the stability of restructuring Cu clusters, ex-situ XANES, 1st derivative of XANES, R space, FT-EXAFS fitting spectra, WT-EXAFS, and XANES LCF spectra detected 5 and 48 h after − 0.95 V in the air (Figs. 6e–g, S30–S33) clarify the transformation of valence states from metallic Cu to the oxidation state of Cu, accompanied by the incompletely reversible transformation from Cu9 clusters to CuN4&Cu3 (initial OCP). Moreover, the bond length in the first shell of exposure in the air for 5 h after − 0.95 V (1.96 Å) is marginally bigger than that of exposure in the air for 48 h (1.94 Å), which can result from the bond between Cu and light atoms (N/O) during the oxidation process of metallic Cu, following by the formation of [Cu(OH)4]2− intermediate on the wet carbon paper of an alkaline solution. Ultimately, intermediates could be anchored again on the –N4Cx sites among the supported materials due to the chelating capacity of Cu2+ [24, 35].

Fig. 6.

a–f The fitting spectra of R space for Cu1.5/NTC at OCP, − 0.75, − 0.85, − 0.95 V, 5 and 48 h after − 0.75 V in air, and the corresponding structures in the inset. g The WT-EXAFS spectra. Gray, green and blue balls, respectively, represent C, N, and Cu atoms

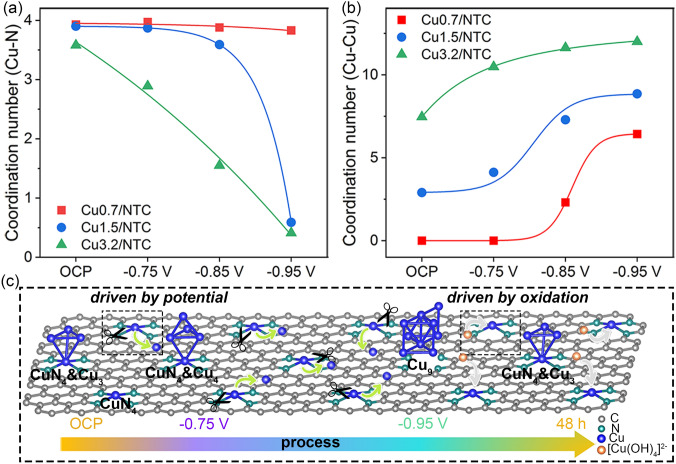

The relationships among the CN, Cu loading, and reaction potential were further investigated using the nonlinear fitting curves of the typical reaction potential versus the CN (Cu–N and Cu–Cu bonds) toward Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts (Fig. 7a, b). Potential intervals of the dominant Cu–N4 configuration in Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts are OCP to − 0.95 V, OCP to − 0.85 V, OCP to − 0.75 V, while the CN maximum increments of Cu–Cu bonds occur at − 0.95, − 0.85, − 0.75 V, indicating that the potentials of electrochemical restructuration are shifted positively with the increased loading of Cu. Consequently, the restructuration behavior among Cu species in this system co-depends on the Cu loading and reaction potential. Furthermore, the possible mechanisms of aggregation driven by potential and redispersion driven by oxidation integrated with chelation for Cu1.5/NTC are described in Fig. 7c and further verified with the EDX mapping of Cu1.5/NTC exposed in the air after − 0.95 V (Fig. S34).

Fig. 7.

a, b Nonlinear fitting curves of the typical reaction potential versus the CN (Cu–N and Cu–Cu bonds) among Cu0.7/NTC, Cu1.5/NTC, and Cu3.2/NTC electrocatalysts. c The possible electrochemically driven remodeling and oxidation-driven redispersion mechanisms for Cu1.5/NTC

Electrocatalytic NITRR Mechanisms

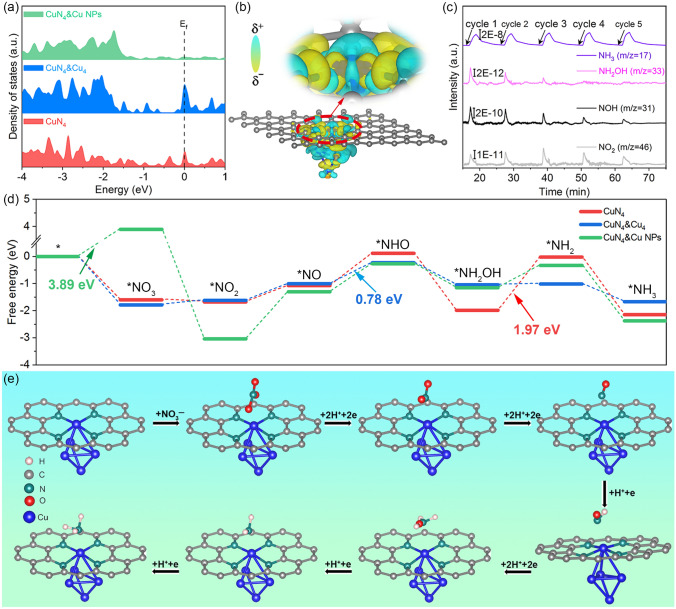

To further evaluate the origin of the NITRR catalytic activity, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were executed with the multi-component models (Fig. S35) of Cu species, including Cu single-atom (CuN4), Cu single-atom and clusters (CuN4&Cu4), Cu single-atom and nanoparticles with (111) facet (CuN4&Cu NPs), based on the fitting structures of FT-EXAFS and the variation trend of mass activity (Fig. S36) [38, 39]. The d-band center of projected density of states (PDOS) for CuN4&Cu4 model (dcenter = − 2.56 eV) is closest to the Fermi level than that of CuN4 and CuN4&Cu NPs (Figs. 8a and S37), signifying that the strong interaction between CuN4 and Cu clusters upshifted the d-band center to improve the adsorption ability of reactants and intermediates [40, 41]. Charge density difference (EDD) distributions of CuN4, CuN4&Cu4, and CuN4&Cu NPs were calculated (Figs. 8b and S38). As a result, introducing the Cu cluster to CuN4 (CuN4&Cu4) can ameliorate the charge distribution of the Cu single-site and modulate the electric structure with high activity for NITRR compared with CuN4 and CuN4&Cu NPs, crucial for invigorating the sluggish NITRR kinetics [42]. Online differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) offers robust technical support for capturing volatile intermediates and products [43]. Additionally, mass signals were acquired during the chronoamperometry test at − 0.75 V for five cycles (Fig. 8c), indicating mass signals of m/z = 17, 31, 33, and 46 are assigned to the intermediate products or the molecular fragments of NH3, NOH, NH2OH, and NO2. According to the results of online DEMS, and integrated with the deoxygenation process of NO3− (*NO3 → *NO2 → *NO) and hydrogenation process of *NO intermediate [44], we calculated the free energy pathway of NH3 formation for each step in detail upon the constructed models with the most stable adsorption configurations, especially for the first step of hydrogenation site of *NO intermediate. Notably, the first hydrogenation site of the *NO intermediate for CuN4, CuN4&Cu4, and CuN4&Cu NPs preferentially forms *NHO rather than *ONH (Fig. S39), which coincides with the DEMS results with the by-products (NOH and NH2OH). At the initiation step of the possible NITRR pathway on CuN4, CuN4&Cu4, and CuN4&Cu NPs utilized Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, the adsorption of reactant NO3– is a spontaneous behavior toward CuN4 and CuN4&Cu4 (more favorable), while the NO3– adsorption on CuN4&Cu NPs with the free energy changes (ΔG) of 3.89 eV is thermodynamically unfavorable (Figs. 8d, e, and S40-S41. Tables S9 and S10) [41, 45]. Besides, the potential-determining steps (PDS) of CuN4 model is *NH2OH to *NH2 (ΔG = 1.97 eV), which is apparently higher than CuN4&Cu4 model (ΔG = 0.03 eV) despite the PDS of CuN4&Cu4 model is *NH to *NOH (ΔG = 0.78 eV), indicating Cu cluster can optimize reaction energy barrier of *NH2OH to *NH2. Meanwhile, the results of solvent model and the local density approximation (LDA) functional were adopted in NITRR calculations, which gave similar tendency in CuN4&Cu4 configuration to PBE data (Figs. S43-S44). In a nutshell, the synergistic coupling between the CuN4 and Cu clusters modulates the charge distribution and the electric structure with the suitable d-band center, enhancing the adsorption ability of NO3− and accelerating the rapid conversion from *NH2OH to *NH2 simultaneously.

Fig. 8.

a PDOS CuN4, CuN4&Cu4, and CuN4&Cu NPs. b EDD distribution of CuN4&Cu4 model. The yellow and cyan regions represent electron accumulation and depletion. c Online DEMS measured at –0.75 V for NITRR over Cu1.5/NTC. d The free energy paths of NH3 production for CuN4, CuN4&Cu4 and CuN4&Cu NPs. e The minimum energy pathway of NH3 production for CuN4&Cu4 configuration. Color code: H (light pink), C (gray), N (green), O (red), Cu (blue). (Color figure online)

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have exhaustively investigated the restructuration behavior in the electrocatalytic NITRR process by employing Cu species with tunable loading supported on N-doped TiO2/C at potentials ranging from OCP to − 0.95 V versus RHE based on the operando XAS. Electrochemical restructuration is the reduction process of Cu with a positive valence state to metallic Cu, and then Cu0 can migrate and aggregate to form Cu clusters or nanoparticles. The restructuration behavior of Cu species is jointly dependent on Cu loading and reaction potential, i.e., the higher Cu loading and the more negative potential, the easier restructuration of Cu species to form Cu clusters or nanoparticles with higher nucleation numbers. Operando XAS and electrocatalytic NITRR performances perform that Cu1.5/NTC with CuN4&Cu4 configuration could deliver the highest NH3 yield with 88.2 mmol h−1 gcata−1 (0.044 mmol h−1 cm−2) and FE (~ 94.3%) at − 0.75 V, which is superior to NTC, Cu0.7/NTC (CuN4 configuration), and Cu3.2/NTC (CuN4&Cu10 configuration). DFT calculation results reveal that Cu clusters with appropriate nuclear numbers modulate the charge distribution and the d-band center of Cu single-site, thus promoting the adsorption ability of NO3− and accelerating the conversion of the key intermediates (*NH2OH → *NH2). This work sheds light on the restructuring behavior trigger, allowing for more informed decisions in the rational design of highly active NITRR electrocatalysts.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the 4B9A station of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and the Analytical and Testing Center of Beijing Institute of Technology for technical supports. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 92061106 and 21971016).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Contributor Information

Xinghui Liu, Email: liuxinghui119@gmail.com.

Jun Tao, Email: taojun@bit.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Guo CX, Ran JR, Vasileff A, Qiao SZ. Rational design of electrocatalysts and photo(electro)catalysts for nitrogen reduction to ammonia (NH3) under ambient conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11(1):45–56. doi: 10.1039/C7EE022-20D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo WH, Zhang KX, Liang ZB, Zou RQ, Xu Q. Electrochemical nitrogen fixation and utilization: theories, advanced catalyst materials and system design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48(24):5658–5716. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00159J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang WC, Zhang BW. Bi-atom electrocatalyst for electrochemical nitrogen reduction reactions. Nano Micro Lett. 2021;13:106. doi: 10.1007/s40820-021-00638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang YP, Su C, Jia GH, Xu LQ, Shao ZP. Emerging two-dimensional nanomaterials for electrochemical nitrogen reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50(22):12744–12787. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00120E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas A, Kapse S, Thapa R, Dey RS. Oxygen functionalization-induced charging effect on boron active sites for high-yield electrocatalytic NH3 production. Nano Micro Lett. 2022;14:214. doi: 10.1007/s40820-022-00966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XW, Wu D, Liu SY, Zhang JJ, Fu XZ, et al. Folic acid self-assembly enabling manganese single-atom electrocatalyst for selective nitrogen reduction to ammonia. Nano Micro Lett. 2021;13:125. doi: 10.1007/s40820-021-00651-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YT, Wang CH, Li MY, Yu YF, Zhang B. Nitrate electroreduction: mechanism insight, in situ characterization, performance evaluation, and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50(12):6720–6733. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00116G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu H, Ma YY, Chen J, Zhang WX, Yang JP. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate–a step towards a sustainable nitrogen cycle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022;51(7):2710–2758. doi: 10.1039/D1CS00857A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang R, Guo Y, Zhang SC, Chen D, Zhao YW, et al. Efficient ammonia electrosynthesis and energy conversion through a Zn-nitrate battery by iron doping engineered nickel phosphide catalyst. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022;12(13):2103872. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202103872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen GF, Yuan YF, Jiang HF, Ren SY, Ding LX, et al. Electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia via direct eight-electron transfer using a copper–molecular solid catalyst. Nat. Energy. 2020;5(8):605–613. doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-0654-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao DM, Wang YQ, Dong CL, Meng FQ, Huang YC, et al. Electron-deficient Zn-N6 configuration enabling polymeric carbon nitride for visible-light photocatalytic overall water splitting. Nano Micro Lett. 2022;14:223. doi: 10.1007/s40820-022-00962-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han LL, Cheng H, Liu W, Li HQ, Ou PF, et al. A single-atom library for guided monometallic and concentration-complex multimetallic designs. Nat. Mater. 2022;21(6):681–688. doi: 10.1038/s41563-022-01252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu X, Zhang HB, Zuo SW, Dong JC, Li Y, et al. Engineering the coordination sphere of isolated active sites to explore the intrinsic activity in single-atom catalysts. Nano Micro Lett. 2021;13:136. doi: 10.1007/s40820-021-00668-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng XB, Li P, Dou SX, Sun WP, Pan HG, et al. Non-carbon-supported single-atom site catalysts for electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021;14(5):2809–2858. doi: 10.1039/D1EE00248A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen WX, Pei JJ, He CT, Wan JW, Ren HL, et al. Single tungsten atoms supported on MOF-derived N-doped carbon for robust electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2018;30(30):180039. doi: 10.1002/adma.201800396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan BL, Liu DP, Feng XL, Shao MZ, Zhang Y. Ru species supported on MOF-derived N-doped TiO2/C hybrids as efficient electrocatalytic/photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30(31):2003. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie XY, Peng LS, Yang HZ, Waterhouse GIN, Shang L, et al. MIL-101-derived mesoporous carbon supporting highly exposed Fe single-atom sites as efficient oxygen reduction reaction catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2021;33(23):21010. doi: 10.1002/adma.202101038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi J, Wagner P, Gambhir S, Jalili R, MacFarlane DR, et al. Steric modification of a cobalt phthalocyanine/graphene catalyst to give enhanced and stable electrochemical CO2 reduction to CO. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4(3):666–672. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b02355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia C, Qiu YR, Xia Y, Zhu P, King G, et al. General synthesis of single-atom catalysts with high metal loading using graphene quantum dots. Nat. Chem. 2021;13(9):887–894. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhai WJ, Huang SH, Lu CB, Tang XN, Li LB, et al. Simultaneously integrate iron single atom and nanocluster triggered tandem effect for boosting oxygen electroreduction. Small. 2022;18(15):2107225. doi: 10.1002/smll.202107225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma ZM, Liu SQ, Tang NF, Song T, Motokura K, et al. Coexistence of Fe nanoclusters boosting Fe single atoms to generate singlet oxygen for efficient aerobic oxidation of primary amines to imines. ACS Catal. 2022;12(9):5595–5604. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.1c04467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xing GY, Tong MM, Yu P, Wang L, Zhang GY, et al. Restructuration of highly dense Cu−N4 active sites in electrocatalytic oxygen reduction characterized by operando synchrotron radiation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61(40):e202211. doi: 10.1002/anie.202211098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu HP, Rebollar D, He HY, Chong LN, Liu YZ, et al. Highly selective electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to ethanol by metallic clusters dynamically formed from atomically dispersed copper. Nat. Energy. 2020;5(8):623–632. doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-0666-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Qi HF, Li AQ, Liu XY, Yang XF, et al. Potential-driven restructuring of Cu single atoms to nanoparticles for boosting the electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144(27):12062–12071. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c02262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu YT, Xie MY, Zhong HQ, Cao Y. In situ clustering of single-atom copper precatalysts in a metal-organic framework for efficient electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonia reduction. ACS Catal. 2022;12(14):8698–8706. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.2c02033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji XY, Wang YY, Li Y, Sun K, Yu M, et al. Enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production of Ti-based metal–organic frameworks: the leading role of facet engineering. Nano Res. 2022;15(7):6045–6053. doi: 10.1007/s12274-022-4301-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janczak J, Idemori YM. Synthesis, crystal structure and characterisation of aquamagnesium phthalocyanine—MgPc(H2O). The origin of an intense near-IR absorption of magnesium phthalocyanine known as ‘X-phase’. Polyhedron. 2003;22(9):1167–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(03)00110-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu J, Hsu CS, Bai LC, Chen HM, Hu XL. Atomically dispersed Fe3+ sites catalyze efficient CO2 electroreduction to CO. Science. 2019;364(6445):1091–1094. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li HD, Pan Y, Wang ZC, Yu YD, Xiong J, et al. Coordination engineering of cobalt phthalocyanine by functionalized carbon nanotube for efficient and highly stable carbon dioxide reduction at high current density. Nano Res. 2022;15(4):3056–3064. doi: 10.1007/s12274-021-3962-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang QW, Liu YM, Lee JH, Ologunagba D, Hwang S, et al. Metal-coordinated phthalocyanines as platform molecules for understanding isolated metal sites in the electrochemical reduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144(35):16131–16138. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c06953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li MY, Wang TH, Zhao WX, Wang SY, Zou YQ. A pair-electrosynthesis for formate at ultra-low voltage via coupling of CO2 reduction and formaldehyde oxidation. Nano Micro Lett. 2022;14:211. doi: 10.1007/s40820-022-00953-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou W, Fu L, Zhao L, Xu XJ, Li WY, et al. Novel core–sheath Cu/Cu2O-ZnO-Fe3O4 nanocomposites with high-efficiency chlorine-resistant bacteria sterilization and trichloroacetic acid degradation performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13(9):10878–10890. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Wang CH, Guo YM, Zhang B, Wang YT, et al. Cu clusters/TiO2–x with abundant oxygen vacancies for enhanced electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022;10(12):6448–6453. doi: 10.1039/D2TA00661H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su H, Zhou WL, Zhang H, Zhou W, Zhao X, et al. Dynamic evolution of solid−liquid electrochemical interfaces over single-atom active sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142(28):12306–12313. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karapinar D, Huan NT, Sahraie NR, Li JK, Wakerley D, et al. Electroreduction of CO2 on single-site copper-nitrogen-doped carbon material: selective formation of ethanol and reversible restructuration of the metal sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58(42):15098. doi: 10.1002/anie.201907994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su XZ, Jiang ZL, Zhou J, Liu HJ, Zhou DN, et al. Complementary Operando Spectroscopy identification of in-situ generated metastable charge-asymmetry Cu2-CuN3 clusters for CO2 reduction to ethanol. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1322. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Liu WG, Xu MQ, Liu XY, Qi HF, et al. Dynamic behavior of single-atom catalysts in electrocatalysis: identification of Cu-N3 as an active site for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(36):14530–14539. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c03788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ao X, Zhang W, Li ZS, Li JG, Soule L, et al. Markedly enhanced oxygen reduction activity of single-atom Fe catalysts via integration with Fe nanoclusters. ACS Nano. 2019;13(10):11853–11862. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b05913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wan X, Liu QT, Liu JY, Liu SY, Liu XF, et al. Iron atom–cluster interactions increase activity and improve durability in Fe–N–C fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2963. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu XH, Zheng LR, Han CX, Zong HX, Yang G, et al. Identifying the activity origin of a cobalt single-atom catalyst for hydrogen evolution using supervised learning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31(18):2100547. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202100547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu Q, Qin YJ, Wang XD, Wang ZY, Huang XW, et al. Reaction intermediate-mediated electrocatalyst synthesis favors specified facet and defect exposure for efficient nitrate–ammonia conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021;14(9):4989–4997. doi: 10.1039/D1EE01731D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar A, Lee J, Kim MG, Debnath B, Liu XH, et al. Efficient nitrate conversion to ammonia on f-block single-atom/metal oxide heterostructure via local electron-deficiency modulation. ACS Nano. 2022;16(9):15297–15309. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c06747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang YT, Li HJ, Zhou W, Zhang X, Zhang B, et al. Structurally disordered RuO2 nanosheets with rich oxygen vacancies for enhanced nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61(19):e202202604. doi: 10.1002/anie.202202604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Zhan GM, Yang JH, Quan FJ, Mao CL, et al. Efficient ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate on strained ruthenium nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142(15):7036–7046. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c00418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yin HB, Chen Z, Xiong SC, Chen JJ, Wang CZ, et al. Alloying effect-induced electron polarization drives nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. Chem. Catal. 2021;1(5):1088–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.checat.2021.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.